Universiti Utara Malaysia, School of Tourism Hospitality and Event Management, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8281-3384, e-mail: ammar.alramadan@hotmail.com

Universiti Utara Malaysia, School of Tourism Hospitality and Event Management, Langkawi International Tourism and Hospitality Research Center, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2217-0989, e-mail: azilah@uum.edu.my

ABSTRACT

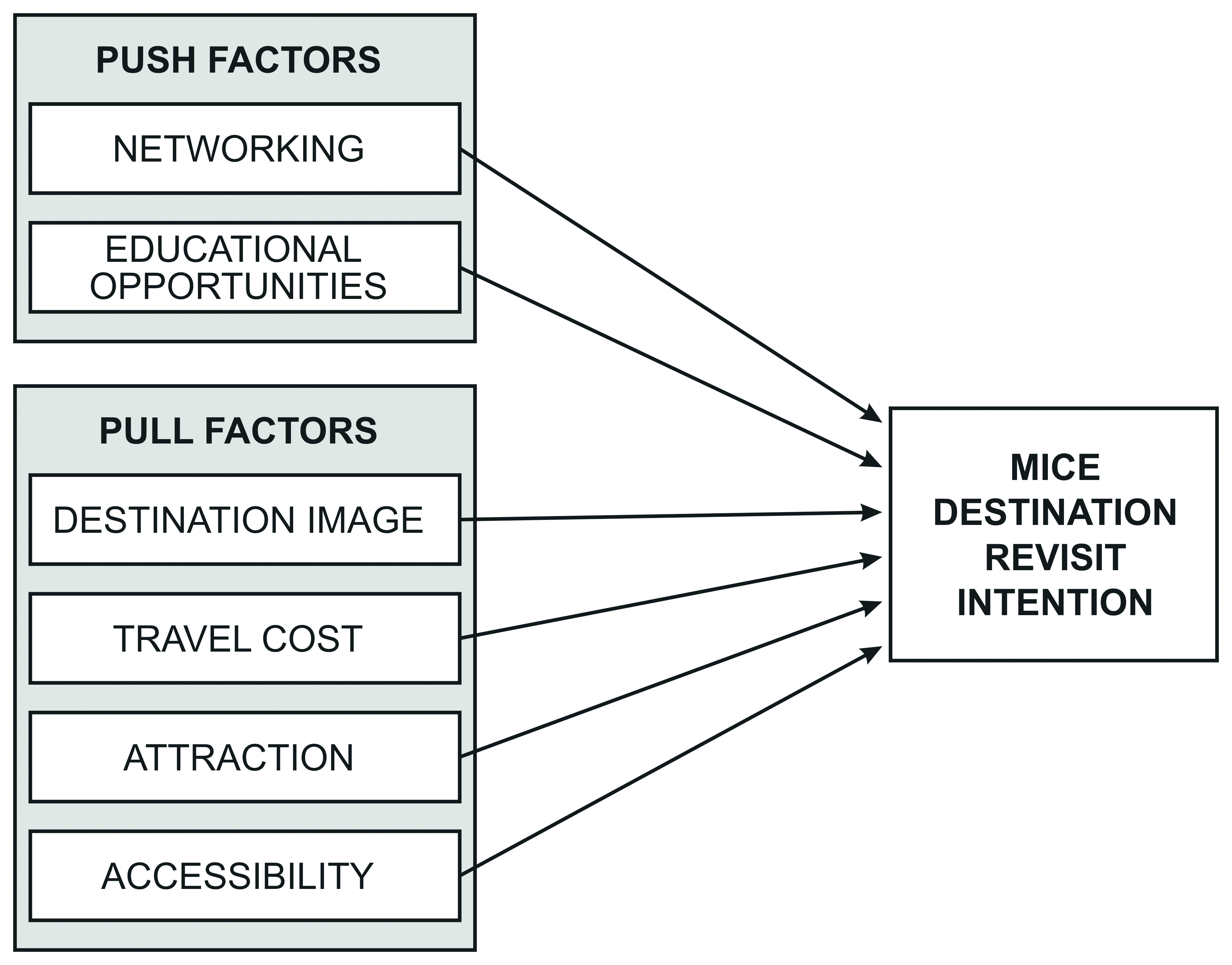

The relationship between push and pull factors with the intention to revisit a destination has often been investigated in the context of general tourism. Not much is known on the factors influencing MICE destination revisit intentions, despite the numerous socioeconomic benefits that many countries have received from the MICE tourism business. This article attempts to fill the gap of knowledge by critically reviewing the literature using the integrative review approach. By reviewing, critiquing and synthesizing major literature on the issue, two push factors i.e. networking and educational opportunities and four pull factors i.e. destination image, travel costs, attraction and accessibility are established as influencing revisit intentions to MICE destination. Then a theoretical model of relationship between those factors and MICE destination revisit intentions is proposed.

KEYWORDS

push factors, pull factors, revisit intention, MICE

How to cite (APA style): Ramadan, A., Kasim, A. (2022). Factors influencing MICE destination revisit intentions: A literature review. Turyzm/Tourism, 32 (1), 185–217. https://doi.org/10.18778/0867-5856.32.1.09

ARTICLE INFORMATION DETAILS: Received: 2 March 2022; Accepted: 24 May 2022; Published: 28 September 2022

Meeting, Incentive, Convention and Events (MICE) tourism had been one of the fastest-growing segments of the tourism industry up until 2020 (Anas et al., 2020; Lee, Koo, Chung, 2019; Nasir, Alagas, Nasir, 2019), earning two to four times more income than other tourism sectors (Anas et al., 2020; Lee, Koo, Chung, 2019). Numerous countries have benefited economically from the MICE tourism business, which has helped to raise the standard of living in many destinations (Nakip, Gökmen, 2018). MICE has also benefited destinations in a variety of other ways, including by supporting and strengthening relationships between hosts and attendees, attracting high-spending tourists, enhancing international economic connections, improving job creation, reducing seasonality within the host destination, and assisting many countries in developing related services and infrastructure (Alananzeh et al., 2019; Anas et al., 2020; Lee, Koo, Chung, 2019; Mhango, 2018; Mureșan, Nistoreanu, 2017; Nasir, Alagas, Nasir, 2019).

Despite the fact that many governments consider MICE to be an important component for increasing tourism revenue (Cró, Martins, 2018; Lee, Back, 2005; Whitfield et al., 2014), certain developing countries are unable to market themselves as viable MICE destinations (Phophan, 2017). Furthermore, despite the enormous amount of money generated by MICE around the world, revenue rates in some underdeveloped nations, such as Jordan, are still insufficient (Jordan Tourism Board, 2016). Jordan’s MICE income in 2018 was approximately $50 million, which is extremely low when compared to other nations and only accounts for 1.7% of the country’s total tourism earnings (Gedeon, Al-Qasem, 2019). A country’s inability to produce significant revenue from the MICE business, despite its unique tourism resources, raises issues why visitors are not drawn to it as a MICE destination. It also raises questions on the need to continue developing MICE facilities and services in order to entice international tourists to visit or revisit.

As stated in the theory of planned behaviour, revisit intentions are a derivative of behavioural intentions and is a powerful predictor of behaviour (Ajzen, 1991). The topic of tourists’ intent to return is one of the key foci in tourism and event literatures that has acquired a lot of attention from researchers and practitioners (Abbasi et al., 2021; Bi, Yin, Chen, 2020; Fitri, 2021; Weru, 2021). The problem of intentions to return has primarily been studied in the context of sports (Allameh et al., 2015; Cho, 2021), mega-events (Zhang, Liu, Bai, 2021), cultural events (Yen, 2020) and festivals in event research (Al-Dweik, 2020).

Unfortunately, few studies had looked at revisit intentions in the setting of MICE (Bi, Yin, Chen, 2020; Fitri, 2021; Yodsuwan, Pathan, Butcher, 2020). This is despite the fact that in the MICE context, behavioural intentions to return to a destination are highly significant, especially in developing nations (Fitri, 2021) in order to ensure successful MICE events. Even though numerous studies have looked into the factors that impact tourists’ decisions to return to a destination for tourism and event research (Abbasi et al., 2021; Al-Dweik, 2020; Allameh et al., 2015; Baniya, Ghimire, Phuyal, 2017; Bi, Yin, Chen, 2020; Fitri, 2021; Susyarini et al., 2014; Tsai, 2020; Wicaksono, Setyaningtyas, Kirana, 2021; Yeoh, Goh, 2017), research on the factors that determine the desire to return to an event in the context of underdeveloped nations has been scarce (Al-Dweik, 2020; Bi, Yin, Chen, 2020).

Thus, this article aims to fill the gap of knowledge by critically reviewing the literature on the variables that influence a tourist’s intention to revisit an event destination. Understanding revisit intentions for a MICE destination is crucial because the choice of venue is an important part of the overall MICE journey. The choice of a location which could host the conference was viewed as a major factor influencing the decision to visit or revisit a destination (Baloglu, Love, 2005; Crouch, Ritchie, 1997; DiPietro et al., 2008; Elston, Draper, 2012; Lee, Back, 2008; Yoo, Chon, 2008). These early studies explain that the conference venue is an important consideration not only for the organizer but also for the participants (Lee, Koo, Chung, 2019). Therefore, it is necessary to understand how to select the right place when holding and organizing a conference (Sperstad, Cecil, 2011).

This article critically reviews the literature with the aim of proposing a framework for understanding the factors influencing MICE destination revisit intentions. The approach taken is called ‘Integrative Review’ (Onwuegbuzie, Frels, 2016) because it fits the purpose of the article. In addition, an integrative review is the most common form of review in the social sciences. The approach involved critically reviewing and synthesizing the literature on the variables that influence tourists’ intentions to revisit an event destination, before generating a model for understanding the factors influencing MICE destination revisit intentions. However, due to the limited availability of literature on MICE per se, our integrative review had to rely mostly on tourism and general event literature in establishing convincing evidence for the factors influencing MICE revisit intentions. In the sections below, the review begins by explaining the concept and typology of MICE tourism, followed by a critical analysis on revisit intentions and its influencing factors.

The acronym ‘MICE’ stands for a type of tourism including meetings, incentive travel, conventions and exhibitions. Similar to this concept, they were called MEI (Meetings, Events and Incentives) or MIT (Meetings, Incentives and Trade Shows) in the United States or MCIT (Meetings, Conventions and Incentive Travel) in Canada (Bao, 2017). In addition, they are known as business events in Australia, and the meeting industry in Europe. This type of tourism is described as planned in advance and designed for large groups of people for particular purposes (Alananzeh et al., 2019), and is a key area of growth for the tourism sector worldwide (Buathong, Lai 2017). Leong (2007) defines MICE as a type of tourism where groups of participants are gathered to achieve certain purposes. Also, there were other definitions from scholars and authoritative associations describing MICE as an acronym for meetings, incentives, conventions and exhibitions (Chen et al., 2012; Lee, 2016).

Rogers (2013) describes meetings as a means for a group of individuals who gather in one place to consult or perform a certain activity. In addition, the main purpose of the meeting is to exchange information and increase knowledge (Altareri, 2016) along with facilitating communication between participants (Akkhaphin, 2016). Meanwhile, incentive travel is defined as an individual or a group traveling to a destination as a reward for stimulating or recognizing their performance in support of organizational goals (Trišić, Arsenov-Bojović, 2018). According to Trišić and Arsenov-Bojović (2018), stimulating travel includes leisure, sports, recreation, participation in congresses, participating as individual business travellers; they also serve as a means of relaxation.

Conference and exhibitions are other form of MICE. A conference is a formal meeting where many people come together to talk about ideas related to a specific topic, usually for several days. According to Trišić and Arsenov-Bojović (2018), conferences are described as large annual meetings of people of the same profession dedicated to debate, consultation and problem-solving. In addition, a conference is designed for participants to interact with each other, and it focuses on audience participation and engaging the attendee with the speaker. Meanwhile, Trišić and Arsenov-Bojović (2018) describe exhibitions as part of business tourism, which presents products or services displayed in the hall so that all buyers and sellers can view them. Within MICE tourism, the exhibition is a relevant and beneficial event, as it seeks to provide participants with information on the latest and greatest goods and services. Internationally, the terms “exhibition”, “expo”, “shop” and “consumer show” or “fair” are used interchangeably to describe an exhibition (Trišić, Arsenov-Bojović, 2018; Welthagen, 2019).

Before looking at the factors influencing revisit intentions, it is best to understand revisit intentions themselves. Ajzen (1991) describe intentions as the subjective possibility of an individual to perform a certain behaviour. Chen and Tsai (2007) state that tourist behaviours include the choice of destination to visit, subsequent evaluation and future behavioural intentions. Tourists encounter many decision-making situations while traveling; Buhalis and Amaranggana (2016) divide tourists’ behaviour into three phases: pre-visit, during visit and post-visit. Pre-visiting is the planning phase where potential tourists decide which destination to choose for the trip, how to get there and where to stay. Upon arrival, during the visit phase, where and what to eat or what activities to do are crucial decisions. In the post-visit phase, future behavioural intentions relate to the visitor’s judgment about being able to revisit the same destination and willingness to recommend it to others. As described, every aspect of the tourist experience puts them in a decision-making position to consider the benefits and risks of the chosen destination.

The concept of destination choice is considered as a critical phase of travel behaviour. Mhango (2018) clarified that destination choice has great importance for the organizers and event participants and contributes to policy-making and management (Filimonau, Perez, 2019). The concept of destination choice has been used extensively in the event context, and it is also considered a critical issue to understand potential MICE tourists’ decision-making processes when selecting a specific destination (Filimonau, Perez, 2019; Jung et al., 2018; Masiero, Qiu, 2018). Jo et al., (2019) declared that destination choice has been deemed an essential topic in MICE research. The majority of previous studies in the MICE context have extensively concentrated on the destination choice from the tourists’ and meeting planners’ perspectives (Aktas, Demirel, 2019; Crouch, Del Chiappa, Perdue, 2019; Houdement, Santos, Sierra, 2017; Jo et al., 2019; Liang, Latip, 2018; Para, Kachniewska, 2014; Pavluković, Cimbaljević, 2020). Nevertheless, there are few studies that discussed intentions to revisit the destination in the MICE context (Bi, Yin, Chen, 2020; Fitri, 2021; Yodsuwan, Pathan, Butcher, 2020).

On the other hand, it is important to make the concept of tourists’ revisit intentions the main foci in event literature (Al-Dweik, 2020; Bi, Yin, Chen, 2020; Fitri, 2021; Tsai, 2020; Yen, 2020). Yen, (2020) described revisiting intentions as the attendees’ willingness to revisit the same event destination in the future. Revisit intentions describe the probability of the attendees engaging in diverse types of event destination in the future is based on their previous travel experiences. When attendees have a more enjoyable experience at the event destination, they are more likely to have plans to revisit the same destination in the future (Yen, 2020). An enhanced understanding of MICE participants’ revisit intentions is one of the main issues that should be focused on in the MICE context in order to ensure successful MICE events.

Several studies have examined tourists’ revisit intentions in the event domain, especially MICE (Al-Dweik, 2020; Bi, Yin, Chen, 2020; Fitri, 2021; Hashemi et al., 2020), and their findings confirmed that tourists’ revisit intentions are valuable for predicting future revisit behaviour. Fitri (2021) found that the topic of revisit intentions is very important and should be studied in the MICE context. Bi, Yin and Chen, (2020) concluded that scant research had been conducted to explore and empirically examine the antecedents of business tourists’ revisit intentions.

This critical review utilizes the theory of push and pull motivation as the foundation to understand behaviour that explains why tourists travel, as well as to describe the push and pull components and intentions to revisit a destination. Independently, the push factors refer to an individual desire to travel. Individuals are affected by external pull factors that influence where, when, and how they travel, given their original intentions to make a trip. Tourists travel due to internal factors pushing them and external influences pulling them, such as destination attributes. According to conventional wisdom, push factors precede pull factors (Dann, 1977; Dann, 1981). Previous works confirmed that push forces must be present before pull forces can be successful (Preko, Doe, Dadzie, 2019).

The push-pull theory has been a popular model for generating and testing incentives in the tourism industry (Crompton, 1979b; Dann, 1977). The concept is that a person is compelled to participate by internal imbalances, the need to achieve an optimal degree of arousal, and the attractions of a particular location. Tourism research considers push factors as socio-psychological needs that influence a tourist’s decision to travel, while the pull factors are regarded as those features that attract a tourist to a specific destination once the decision to travel has been made (Preko, Doe, Dadzie, 2019).

According to the literature, Dann (1977) and Crompton (1979b) are the first two studies that applied the concept of push and pull factors while Crompton (1979b) was the first who sought to identify push and pull relationships in tourism to explain the destination choice. Crompton (1979b) attempted to conceptualize the motives of holiday travellers based on Dann’s study. He found nine motives, seven of which were socio-psychological or push motives, and two of which were cultural or pull motives. Escape from a perceived monotonous environment, self-exploration and appraisal, relaxation, prestige, regression, enhancement of kinship bonds, and facilitation of social contact were all push factors. The factors that drew people in were novelty and education. A resort’s pull factors such as sunshine, a laid-back atmosphere, and friendly locals respond to and strengthen push factor motivation, as stated by Dann (1981). Furthermore, there has been an increasing number of works on ‘push’ and ‘pull’ factors in recent decades (Baniya, Ghimire, Phuyal, 2017; Dimitrovski, Seočanac, Luković, 2021; Kim, Lee, 2002; Luvsandavaajav, Narantuya, 2021; Uysal, Jurowski, 1994). Dann (1977) and Crompton (1979b) are the two most comprehensive studies that use push and pull factor hypotheses.

Push-pull theory describes tourist behaviour by understanding the various demands and needs that may influence their actual selection of a destination. Mainly, the theory advocates the motivation behind the behaviour of tourists in two ways: via push factors explained by internal desires to travel, and pull factors explained by a person’s decision on destination attributes. In addition, tourist motivations could be interpreted through push and pull factors to explain the tourist’s decision in selecting a destination (Baniya, Ghimire, Phuyal, 2017; Fila Hidayana, Suryawardani, Wiranatha, 2019; Joo, Sean, Hong, 2017; Khuong, Ha, 2014; Kim, 2021). Undeniably, the framework of push and pull theory has been widely used by researchers to examine issues in a variety of fields such as health and wellness (Ting et al., 2021), travel motivation (Luvsandavaajav, Narantuya, 2021), spa destinations (Dimitrovski, Seočanac, Lukovići, 2021), youth tourism (Preko, Doe, Dadzie, 2019) and events tourism (Qi, Smith, Yeoman, 2019). Therefore, the push-pull theory is popular among researchers as it is used extensively in the tourism field (Baniya, Ghimire, Phuyal, 2017; Baptista, Saldanha, Vong, 2020; Dimitrovski, Seočanac, Lukovići, 2021; Kim, 2021; Luvsandavaajav, Narantuya, 2021; Preko, Doe, Dadzie, 2019; Qi, Smith, Yeoman, 2019; Yousefi, Marzuki, 2015). These studies confirmed that the push and pull theory is applicable in the motives of tourists.

Accordingly, the push and pull theory assumes that people are pushed by internal desires or emotional factors to travel and are pulled by external or tangible factors (destination attributes). Therefore, a major part of this theory is to describe the association between push and pull factors when selecting a destination. This theory also clarifies that push-pull factors act in tandem with the tourists’ decision, which is eventually related to their travel behaviour. Hence, the push-pull theory ultimately incorporates internal and external factors that serve as facilitators or inhibitors to make personal decisions for visiting or revisiting a destination.

In MICE, push and pull factors are also known as motivational factors that contribute to the event’s success (Anas et al., 2020). Understanding motivational factors for attendance has become a prominent subject for researchers (Dragin-Jensen et al., 2018). A deeper understanding of the motives of MICE attendees is a target of event managers and marketers of destinations to increase knowledge and ensure attendee satisfaction (Dragin-Jensen et al., 2018). It has been widely acknowledged that travel motivation plays a strong role in determining and predicting MICE decision-making to revisit a destination. The intentions of travellers to attend or re-attend MICE events may be predicted on the basis of various travel motivations (push and pull) factors. It is rational to suggest that the intentions to revisit a MICE destination improves when the travel motivations i.e., push and pull factors are combined. Studies in MICE tourism have examined motivational factors that influence tourists’ decision to attend MICE events and categorized the motivational factors into two push and pull.

Based on the extensive literature review, six motivational factors influencing tourists’ decision to re-attend MICE events can be identified. From these, there are two push factors namely networking and educational opportunities (Cassar, Whitfield, Chapman, 2020; Dimitrovski, Seočanac, Lukovići, 2021; Gračan, Barkiđija Sotošek, Torbarina, 2021; Kim, Kim, Oh, 2020; Kim, Lee, Kim, 2012; Lee, Koo, Chung, 2019; Mair, Thompson, 2009; Pavluković, Cimbaljević, 2020; Severt et al., 2007; Yodsuwan, Pathan, Butcher, 2020; Yoo, Chon, 2008; Yoo, Zhao, 2010), and four pull factors namely destination image, travel cost, attractions and accessibility (Abulibdeh, Zaidan, 2017; Al-Dweik, 2020; Choi, 2013; Fitri, 2021; Gračan, Barkiđija Sotošek, Torbarina, 2021; Hashemi et al., 2020; Houdement, Santos, Serra, 2017; Kim, Kim, Oh, 2020; Lee, Koo, Chung, 2019; Mair, Thompson, 2009; Tanford, Montgomery, Nelson, 2012; Weru, Njoroge, 2021; Yoo, Chon, 2008). The next sections will discuss the influence of push and pull factors on tourists’ decisions to re-attend MICE events in detail.

Push factors are the intangible or psychological factors intrinsic to event participants that drive them to decide to attend a MICE event. Related studies have indicated the importance of networking and educational opportunities as push motivational factors (Cassar, Whitfield, Chapman, 2020; Dimitrovski, Seočanac, Luković, 2021; Gračan, Barkiđija Sotošek, Torbarina, 2021; Kim, Kim, Oh, 2020; Kim, Lee, Kim, 2012; Lee, Koo, Chung, 2019; Mair, Thompson, 2009; Pavluković, Cimbaljević, 2020; Severt et al., 2007; Yodsuwan, Pathan, Butcher, 2020; Yoo, Chon, 2008; Yoo, Zhao, 2010). The following sections explain these factors in detail.

According to Grant (1994) networking opportunities are defined as an individual’s interaction for personal contact with others which brings professional benefits to the meeting. Networking opportunities are also described as the interactions among attendees to expand their networking, make business contacts, and gain recognition from peers by participating in MICE events (Gračan, Barkiđija Sotošek, Torbarina, 2021). Networking opportunities are considered a form of socialization (Choe, Lee, Kim, 2014; Lee, Yeung, Dewald, 2010), and also recognized as one of the prime push dimensions (Crompton, 1979b). In convention tourism literature, networking opportunities are considered as the key aspect of the convention-specific dimension because it is an influential motivating factor for convention attendees (Barkiđija Sotošek, 2020). Mair, Lockstone-Binney and Whitelaw (2018) revealed that networking opportunities are one of the motivational factors influencing tourists’ decisions to attend or re-attend MICE events. Dimitrovski, Seočanac and Luković (2021) also found the networking factor to be important in the business event context. Moreover, Cassar Whitfield and Chapman (2020) affirmed that networking opportunities are an essential factor in the MICE context. Therefore, networking opportunities have been investigated extensively in the literature of conventions and business events, and still require further research (Yodsuwan, Pathan, Butcher, 2020).

Related studies clarified that networking op-portunities serve as an important factor for the participant in selecting a destination, increasing the likelihood of attendees, boosting their satisfaction level, and encouraging them to attend the MICE event again (Cassar, Whitfield, Chapman, 2020; Draper, Neal, 2018; Jung et al., 2018). Barkiđija Sotošek (2020) showed that the attendees are mainly motivated to participate in the convention by the opportunity to expand their social network, make business contacts and gain new ideas. Regardless of the number of convention participants each year, social networking and professional education are the most important determinants in selecting a convention to attend (Gračan, Barkiđija Sotošek, Torbarina, 2021). Previous works indicated that the attendees are motivated to attend a convention by the opportunities to keep up with the changes in their profession and to acquire new knowledge (Lee, Min, 2013; Oppermann, 1996; Severt et al., 2007; Yoo, Chon, 2008).

Additionally, networking opportunities enhance personal interaction with colleagues or friends, peer recognition and participation experience (Yoo, Chon, 2008; Yoo, Zhao, 2010). According to several studies (Jago, Deery, 2005; Mair, Thompson, 2009; Rittichainuwat, Beck, Lalopa, 2001; Severt et al., 2007; Zhang, Leung, Qu, 2007), networking opportunities and social aspects are notable influencers behind participation in businesses events. Gračan, Barkiđija Sotošek and Torbarina (2021) confirmed that networking opportunities represent a key dimension in the convention tourism literature because they are influential motivational factors for convention attendees. Barkiđija Sotošek (2020) also found that meeting new professionals, like-minded people, and familiar people in reality as the most common elements explaining networking opportunities.

Rittichainuwat, Beck and Lalopa, (2001) and Yoo and Chon, (2008) emphasized the importance of networking and convention factors, such as the topic and conference quality, and believed that networking is one of the most important reasons for attending conventions. They also pointed out that networking opportunities can increase the number of attendees. Gračan, Barkiđija Sotošek and Torbarina (2021) revealed that networking opportunities are positively related to the behavioural intentions of those who visit more than one convention per year and those who attend one convention per year. Hence, networking opportunities play an important role in motivating people to attend business events (Jago, Deery, 2005; Mair, Thompson, 2009; Rittichainuwat, Beck, Lalopa, 2001; Severt et al., 2007; Zhang, Leung, Qu, 2007).

There is an extensive amount of research conducted in the convention literature regarding networking opportunities in developed and developing countries. For example, Yoo and Zhao (2010) investigated the factors affecting conference attendees’ decision to revisit a convention by using a sample of 216 hospitality professionals. The study revealed that networking opportunities significantly influence intentions to revisit the same convention. A study conducted by Kim, Lee and Kim, (2012) showed that both first-time and repeating convention attendees, highly value networking opportunities in determining their value and behavioural intentions towards a destination. This fact was confirmed through another study carried out by Lee and Min (2013) who investigated the role of multidimensional values in the behaviour of convention attendees. The study result showed that networking opportunities have a high significance on behavioural intentions towards a destination. In the same vein, Gračan, Barkiđija Sotošek and Torbarina (2021) revealed that networking opportunities are positively related to the behavioural intentions of those who visit more than one convention per year and those who attend one convention per year. The study indicated that this result is expected and logical given that it is actually the most common goal of academic conventions.

A related study by Lee, Koo and Chung (2019) examined North Korea’s missile threats and visitors’ international conference choice behaviour and revealed that networking opportunities have a significant influence on perceived value and choice behaviour. A similar result found by Mair and Thompson, (2009) revealed that networking opportunities have a significant influence on attendees’ future decisions. Malekmohammadi, Mohamed and Ekiz, (2011) investigated conference attendees’ motivations to select Singapore as a conference destination and found that networking opportunities have a significant impact on the participants’ decision to visit Singapore as a convention destination in the future. In contrast, networking opportunities are negatively associated with destination choice in a study that tested these relations through an online survey involving 292 Rioja and Bordeaux wine tourists (Afonso et al., 2018).

Dimitrovski, Seočanac and Luković (2021) investigated the influence of the main motivators on the behavioural intentions of 287 visitors to the commemorative event “The Great School Hour”. The study showed that networking opportunities that represent socialization posed an insignificant impact on behavioural intentions. Another study conducted by Fakeye and Crompton (1992) found that networking opportunities are not significant in influencing repeat visitations.

From the discussion above, it can be observed that networking opportunities pose a crucial influence on tourists’ intentions to revisit MICE events within the context of developed and developing countries. Previous studies found that the relationship between networking opportunities and revisit intentions is not stable for the different contexts, therefore requiring more investigation in the future. In addition, Yodsuwan, Pathan and Butcher (2020) and Ramírez-Gutiérrez et al. (2019) indicated that networking opportunities pose a great benefit for MICE events, another aspect that should be examined further in future studies. Therefore, networking opportunities should be tested to determine if they serve as an influencing factor on intentions to revisit a MICE destination.

Educational opportunities are described as the acquisition of skills and the learning of new knowledge and ideas for the MICE event participants (Kim, Lee, Kim, 2012). In the tourism literature, Crompton (1979b) was among the first tourism researchers who identified the importance of educational opportunities as one of the motivation factors and indicated it as a primary factor for tourists. Solomon (2019) stated that educational opportunities are recognized as a strong reason that motivates people to travel. In the convention tourism literature, educational opportunities are a key aspect of the convention-specific dimension because it is an influential motivating factor for convention attendees (Barkiđija Sotošek, 2020). Jung and Tanford, (2017) and Mair Lockstone-Binney and Whitelaw (2018) also declared that educational opportunities are important motivational factors for attending conferences. Severt et al. (2007) pointed out that educational opportunities represent one of the push components which is closely correlated with MICE tourism.

Recently, educational opportunities have gained more attention from researchers in the MICE context (Lee, Koo, Chung, 2019). Yodsuwan, Pathan and Butcher (2020) confirmed that educational opportunities are an important motivating factor that has been investigated extensively in conventions and business events, and which still requires further research. Relevant studies pointed out the importance of educational opportunities for attendees in the MICE context in terms of the acquisition of new skills and knowledge, the creation of excellent experience, and satisfaction (Cassar, Whitfield, Chapman, 2020; Kim, Kim, Oh, 2020; Lee, Koo, Chung, 2019). Choi (2013) claimed that educational opportunities offer a valuable starting point as a motivator to participate in a meeting. Draper and Neal (2018) also clarified the importance of educational opportunities from the attendees’ perspective when deciding to attend an event. Regardless of the number of convention participants each year, professional education is the most important determinant in selecting a convention to attend (Gračan, Barkiđija Sotošek, Torbarina, 2021).

Additionally, Ngamsom and Beck, (2000) indicated that MICE events serve as a great opportunity to travel abroad for educational opportunities. Jago and Deery (2005) pointed out that decisions to attend conferences are based primarily on the expected educational opportunities, and they believe that educational opportunities are a strong factor that influences such intentions to attend MICE events. Severt et al. (2007) determined that educational benefits have a major effect on attendees’ satisfaction. According to Oppermann (1996), when assessing convention participation factors, education and networking were highly ranked among the participation decision-making variables. Related studies found that educational opportunities have a significant influence on MICE tourists’ decisions to attend or re-attend MICE events (Kim, Lee, Kim, 2012; Lee, Min, 2013; Mair, Thompson, 2009; Pavluković, Cimbaljević, 2020; Rittichainuwat, Beck, Lalopa, 2001; Severt et al., 2007; Yoo, Chon, 2008; Yoo, Zhao, 2010). Accordingly, educational opportunities are one of the underlying dimensions of convention motivation (Barkiđija Sotošek, 2020).

There is an extensive amount of research in the convention literature regarding education opportunities. For instance, Gračan, Barkiđija Sotošek and Torbarina (2021) assessed the influence of participation frequency at conventions on the behavioural intentions of 978 university teaching staff in the Republic of Croatia who had visited one convention per year or more than one. For both groups, the study found that professional education opportunities positively influence behavioural intentions. Another research investigated the factors affecting Serbia’s conference participation decision-making (Pavluković, Cimbaljević, 2020). The study revealed that educational opportunities are one of the most influential motivational factors for attending conferences. The finding is confirmed by Yoo and Chon (2008) who found that educational opportunities have a significant impact on participation decisions in the context of MICE events. A meta-analysis conducted by Jung and Tanford (2017) on convention attendee satisfaction and loyalty revealed that educational opportunities have a medium relationship with loyalty.

Conversely, a related study was conducted to discover visitors’ experience in Malaysia among 150 tourists to assess their likelihood to make repeat visits to the same place. Results revealed that educational opportunities did not affect revisit intentions (Gani, Mahdzar, Anuar, 2019). Another study by Lee, Jeong and Qu (2020) also found that educational opportunities did not affect visitors’ revisit intentions. Mair and Thompson (2009) studied 1400 delegates at six UK association conferences during the spring and summer of 2003 and found that their educational benefit had no significant influence on future attendance. In a similar vein, Yoo and Zhao’s (2010) research on 216 hospitality industry professionals regarding their convention participation decision-making reported that educational benefits do not significantly influence intentions to participate in conventions.

From the argument above, it can be concluded that educational opportunities are considered an influential variable in the context of developed and developing countries. Nevertheless, empirical research in the MICE context requires more investigation in developing countries, especially in the Middle East region. Existing studies have shown that a significant level of educational opportunities is not stable within the diverse contexts, which thus demands more examination in the future. Furthermore, Yodsuwan, Pathan and Butcher (2020) as well as Elston and Draper (2012) recommended further research to be carried out on the effect of educational opportunities in the MICE context. Based on the researcher’s limited knowledge, there is very little research on this construct in the context of MICE. Therefore, the educational opportunities construct should be tested to see if it serves as a variable influencing international tourists to revisit a MICE destination.

Pull factors refer to the factors that attract event participants to attend MICE events. Existing studies demonstrate the importance of destination image, travel cost, attraction, and accessibility as motivational pull factors (Abulibdeh, Zaidan, 2017; Al-Dweik, 2020; Choi, 2013; Fitri, 2021; Gračan, Barkiđija Sotošek, Torbarina, 2021; Hashemi et al., 2020; Houdement, Santos, Serra, 2017; Kim, Kim, Oh, 2020; Lee, Koo, Chung, 2019; Mair, Thompson, 2009; Tanford et al., 2012; Weru, Njoroge, 2021; Yoo, Chon, 2008). The following section will discuss the pull factors in greater details.

The concept of destination image was first introduced in the tourism industry by Hunt (1975). It has since been the subject of numerous academic studies (Abbasi et al., 2021) showing the effect of image considerations as a pivotal factor (Stylidis, Belhassen, Shani, 2015) on behavioural intentions including the intention to recommend (Prayag et al., 2017), intentions to revisit (Loi et al., 2017) and intentions to visit (Molinillo et al., 2018). The image of a destination is defined as a person’s collection of beliefs, ideas, and impressions that of a destination (Crompton, 1979a). Destination image can be defined from both cognitive and affective aspects; cognitive image refers to the beliefs or knowledge and attitudes of the attributes (Gartner, 1994), while affective image is the tourists’ emotions or feelings in response to different attributes of the destination (Xu et al., 2018).

Destination image is an important construct which influences tourists’ decision-making, destination choice, post-trip evaluation, and future behaviours (Ramli, Rahman, Ling, 2020). Destination images are central to the tourists’ decision-making process, hence attracting researchers’ constant attention (Houdement, Santos, Serra, 2017; Stylos et al., 2016). Bigné, Sánchez and Sánchez (2001) as well as Lee and Back (2005) emphasized that destination image plays two crucial roles in behaviour: firstly, it influences the destination choice decision-making process, and secondly, it influences conditions after decision-making behaviours (intentions to revisit and willingness to recommend). Weru and Njoroge (2021) also reported that destination image is seen as an important factor in influencing tourists’ destination choices. Previous works confirmed that destination image has a significant impact on tourists’ destination choices and intentions to revisit, which leaves a significant impact on their actual behaviour (Abbasi et al., 2021; Iordanova, Stylidis, 2019; Weru, Njoroge, 2021).

Research by Phau, Quintal and Shanka, (2014) indicated that destination image is an important factor that motivates an individual to visit and revisit a certain place. Several researchers considered destination image as one of the strongest predictors of tourists’ future revisit intentions (Kim, Lee, Kim, 2012; Singh, Singh, 2019). Susyarini et al. (2014) pointed out that a better image of a destination can increase the interest of tourists to return or recommend. When the tourists agree that the overall destination image is good, positive and favourable, they will revisit the same destination (Nguyet, 2017). Ramli, Rahman and Ling (2020) found that repeat tourists have a different perception, and that their process image formation and travel behaviour are different from first-time visitors. Therefore, managing, measuring and improving a destination’s image is necessary to increase visits or re-visits (Dragin-Jensen, Kwiatkowski, 2019; Weru, Njoroge, 2021).

A vast majority of researchers had adopted the typology of Gartner (1994) (i.e. cognitive, affective, and conative image) and examined the direct or indirect effect of the components of an image on the intentions of tourists to visit or revisit a certain place (Stylos et al., 2016). Some of the previous studies had examined destination image as a unidimensional construct (Bui, Le, 2016), while others had examined it as a multidimensional construct measured by cognitive, affective and conative dimensions (Assaker, Hallak, 2013; Mun, Lee, Jeong, 2018; Wang, Hsu, 2010). Based on that, the delineation of destination image as either a multidimensional or unidimensional construct depends on the research purpose.

In the context of event, destination image plays a considerable role in influencing visitors’ decisions to attend future events (Al-Dweik, 2020). Zhang, Liu and Bai (2021) claimed that in event studies focusing on destination image (whether city or country), the measurement items are related to tourists’ core needs and experiences such as attractions, facilities, services and atmosphere. The destination image refers to the perceived image of the host city as a tourist destination. In organizing a MICE event, all stakeholders should help to achieve a positive image for MICE tourists to come back to the destination (Al-Dweik, 2020). Susyarini et al. (2014) clarified that a positive image of the destination can encourage MICE tourists to revisit and give a positive recommendation. Al-Dweik (2020) also confirmed that a positive and strong destination image can motivate tourists to consider the destination and increase their frequency of visits there. On the other hand, a negative image created via the perception of low safety and security demotivates tourists to travel (Hsu, Lin, Lee, 2017).

Additionally, extant studies on the effects of destination image mainly focused on sports or cultural events such as the Olympics and various expos, while MICE business events have been largely ignored (Zhang, Liu, Bai, 2021). Destination image has been proven as an important factor influencing individual attitudes and behaviours in tourism, international marketing and event fields (Zhang, Liu, Bai, 2021). Al-Dweik (2020) also supported the supposition that destination image is a driving variable of a positive attitude towards events as well as having a robust complementary role in event participation intentions. Even though there are many investigations about the relationship between destination image and destination (re)visit intentions (Kim, Kang, Kim, 2014; Kim, Park, Kim, 2016; Lee, Koo, Chung, 2019; Milovanović et al., 2021), scant studies have examined the effect of destination image on (re)visit intentions (Zhang, Liu, Bai, 2021).

Stylos et al. (2016) concluded that destination image is essential for delineating tourists’ intentions to revisit a destination. However, the importance of destination image, in general, remains unclear. Another study revealed that destination image influences behavioural intentions directly and indirectly (Som et al., 2012). Prior studies have also empirically proven that destination image plays central and diverse roles in the process of decision-making, as all decision-making factors such as time, money, and family rely upon the image of each destination to satisfy the decision-makers, subsequently influencing both first-time visit and revisit intentions (Abbasi et al., 2021; Allameh et al., 2015). The result from Abbasi et al. (2021) implies that destination image plays a pivotal role in the determination of tourists’ destinations; thus, the better the image of the destination, the more the people that will be attracted to visit/revisit it.

Fitri (2021) analyzed the effect of novelty seeking, destination image and perceived value on the satisfaction of 100 tourists who had participated in MICE activities in Medan City. The study found that destination image through satisfaction has a positive and significant effect on intentions to revisit MICE destinations. Another study by Weru (2021) investigated the influence of perceived destination image on international MICE visitors’ post-visit behaviour. The study employed a convenience sampling method which derived a total sample of 335 respondents. The findings indicated that the cognitive image dimension has a positive and significant influence on affective image, overall image and post-visit behaviour. Affective image positively influences overall image, but not post-visit behaviour. Overall destination image had the greatest effect on post-visit behaviour. A similar result was found by Susyarini et al. (2014) who examined the behavioural intentions of 100 foreign tourists who attended international meetings/conventions in Bali. The study revealed that destination image directly influences behavioural intentions.

Al-Dweik (2020) examined the influence of event and destination images on 223 visitors’ satisfaction and intentions to revisit the Jerash and Fuheis festivals in Jordan. The finding of the study showed that destination image has a significant effect on intentions to re-visit. The result from a study on tourists in Iran shows that destination image positively influences the intentions of tourists to revisit Iran as a sports tourism destination (Allameh et al., 2015). The study result by Sitepu and Rismawati (2021) showed that revisit intentions are significantly influenced by service quality, destination image and tourist satisfaction. The results of the study prove that efforts to increase tourists’ revisit intentions can be made by improving destination management in terms of destination image.

On the other hand, Sirait et al. (2021) found that the image of the destination has an indirect and insignificant effect on the intentions to return through tourist satisfaction. Another study by Zhang, Liu and Bai (2021) examined the effect of business event images on destination and country image from an exhibitors’ perspective and on the exhibitors’ behavioural intentions towards the event. The finding of the study showed that destination image has no significant effect on the exhibitors’ event behavioural intentions.

In sum, though many studies have analyzed the effect of destination image on tourists’ decision-making processes, future behavioural intentions, and revisit intentions (Al-Dweik, 2020; Sirait et al., 2021; Sitepu, Rismawati, 2021; Weru, 2021; Zhang, Liu, Bai, 2021), they have yet to come to a consensus because while some found a positive impact (direct or indirect) of destination image on revisit intentions (Al-Dweik, 2020; Allameh et al., 2015; Fitri, 2021). Some revealed a negative relationship (Sirait et al., 2021; Zhang, Liu, Bai, 2021). The results vary in terms of direction, magnitude and statistical significance due to the variety in research contexts, research approaches, research strategies, sampling methods, and methods for measuring different components of the destination image. Therefore, destination image in the tourism and event context is controversial and needs more investigation. Moreover, despite MICE events being a fast-growing subsector of tourism, there are limited studies that have focused on the influence of destination image in the MICE context (Weru, Njoroge, 2021). Consequently, destination image should be empirically examined to see if it serves as a factor influencing the intentions to revisit a MICE destination.

Travel costs refer to the total amount of money that attendees spend on food and beverages, conference registration, transportation and accommodation expenses (Alananzeh, 2012). Travel costs have received considerable attention from most researchers (Masiero, Qiu, 2018) as it plays a vital role in a decision to attend MICE events (Kim, Kim, Oh, 2020). Ortaleza and Mangali (2021) pointed out that travel costs are considered one of the factors that influence tourists’ decisions. Related studies declared travel costs as a key driver of MICE attendance (Elston, Draper, 2012; Kim, Kim, Oh, 2020; Veloutsou, Chreppas, 2015; Yoo, Zhao, 2010). Nevertheless, travel costs are also one of the main barriers affecting tourists’ decisions to attend MICE events (Cassar, Whitfield, Chapman, 2020). Mair, Lockstone-Binney and Whitelaw (2018) found that travel costs are a potent challenge for MICE tourists. Previous studies also indicated that travel costs are a pull factor and is a negative indicator of conference participation (Mair, Thompson, 2009; Tanford, Montgomery, Nelson, 2012).

According to Mair, Lockstone-Binney and Whitelaw (2018) meeting attendance and/or attitudes toward MICE re-attendance may be contingent upon a particular aspect, such as travel costs. Accordingly, Cassar, Whitfield and Chapman (2020) identified 62 potential inhibiting factors including such costs. Many other previous studies had also determined that travel costs are a potential inhibiting factor (Elston, Draper, 2012; Kim, Kim, Oh, 2020; Veloutsou, Chreppas, 2015; Yodsuwan, Pathan, Butcher, 2020; Yoo, Zhao, 2010). Destinations with high travel costs would negatively influence future attendance and lead to the failure of the MICE event. Consequently, high travel costs play a crucial role in tourists’ decisions to attend or re-attend the same event in the future (Anas et al., 2020; Barkiđija Sotošek, 2020; Houdement, Santos, Serra, 2017; Mair, Thompson, 2009; Tanford, Montgomery, Nelson, 2012; Whitfield et al., 2014).

Yet, some studies found that participants do not consider travel costs as barriers against attending a conference (Lee, Koo, Chung, 2019). In fact, Oppermann and Chon (1997) pointed out that destinations within the proximity of the tourists might affect their decision to revisit the same destination because it would not be very costly. Related works clarified that destinations with low travel costs encourage international business tourists to visit a destination many times, which in turn enables the destination to make more profit. Affordable MICE tourism destinations in terms of cost of travel, rates of accommodation, and entrance fees to the conference would definitely help in making a decision.

The cost factor is composed of four main attributes including transport, accommodation, food and beverages and commodity prices (Filipovic, 2012). A person’s budget for attending a conference includes costs for transportation, accommodation, registration fees and others. Furthermore, Zhang, Leung and Qu (2007) added the time-cost element to the traditional monetary cost within what they define as the total cost factor of attending a conference. In the time of financial constrictions in the business travel industry, money and total costs have a great impact on tourists’ behavioural intentions towards upcoming conventions (Barkiđija Sotošek, 2020). If a conference attendee is satisfied with the conference, he/she will tend to overcome the incurred cost, even though the participation cost plays a crucial role in decision-making about whether to re-attend or not. Thus, attendees’ intentions to attend an event decrease when the monetary or non-monetary costs exceed a certain acceptance level (Kim, Kim, Oh, 2020; Lee, Fenich, 2016; Severt et al., 2007).

In Jordan, for example, Gedeon and Al-Qasem (2019) reported that travel costs are one of the main threats facing the tourism sector. Similarly, a study conducted by Alfandi (2021) indicated that European visitors strongly believe that Jordan is more costly than any other vacation destinations. Given the fact that European tourists are a highly sensitive segment market particularly to service quality, a lack of food and accommodation options at multiple prices will hence discourage them from visiting Jordan. As a result, it is very difficult to sell Jordan if many European visitors and tour operators see it as a pricey destination (Alfandi, 2021). Another study carried out by Kim, Kim and Oh (2020) found that ‘travelability’, which includes total costs as part of the scale, is the most important factor for conference attendance.

Zhou (2005) examined the impact of destination attributes on international tourists’ decisions for choosing Cape Town as a holiday destination. The author found that travel costs are one of the significant attributes for international tourists’ decisions to select Cape Town as a travel destination. A similar result was found by Di Pietro et al. (2008) when studying the impact of costs on MPI (Meeting Professionals International) and IAEE (International Association of Exhibitions and Events) members’ travel destination decisions. Liang and Latip (2018) studied the factors affecting the decision of 142 tourists to attend conventions held in Kuching, Sarawak, and found that total cost is a significant factor towards that end.

Using a study population made up of professionals in the hospitality industry, Yoo and Zhao (2010) found that ‘travelability’ has a significant influence on the intentions to revisit conventions. Similarly, Yodsuwan, Pathan and Butcher (2020) explored the drivers of organizational citizenship behaviour (OCB) among corporate meeting attendees. The sample entailed individuals attending domestic corporate meetings in Thailand. The result of the study indicated that opportunity cost has a major significant impact on intentions to revisit. Another analysis was made on the relationship between travel costs (price and value) and intentions to revisit. The study involved 283 local and foreign tourists who had visited Gunung Mulu, Gunung Gading, Bako, Kubah and Niah National Parks in Sarawak, Malaysia. The results showed that only cost and value have a significant and positive impact on the tourists’ intentions to revisit (Thong, Ching, Chin, 2020).

Watjanasoontorn, Viriyasuebphong and Voraseyanont (2019) examined sports marketing mix (7Ps) as a factor that impacts domestic tourists’ intentions to revisit Buriram using a sample of 378 visitors to the I-mobile Stadium and Buriram Racing International Circuit (BRIC). The findings of the study showed that key elements of the sports marketing mix like price have an impact on domestic tourists’ intentions to revisit sports tourism in Buriram. The study indicated that price can be used to predict domestic tourists’ intentions to revisit. Meanwhile, Barros and Assaf, (2012) analyzed the intentions of tourists visiting the city of Lisbon, Portugal to return there. The results show that travel cost and travel time have a negative impact on repeat tourism. Another study by Mair and Thompson (2009) investigated attendees at a UK association conference and found that cost is a negative predictor of future attendance.

Still on costs, Nguyet (2017) indicated that the cost of attracting repeat visitors is less than that for first-time visitors. A study by Abbasi et al. (2021) confirmed that travel costs involved in attracting and retaining repeat visitors are significantly lesser than that for first-time visitors. Therefore, regular tourists and conference attendees are always looking to meet their individual needs as motivation to make better travel decisions (Hashemi et al., 2020).

In conclusion, travel costs have been considered an influential factor for intentions to revisit in developed and developing countries. Previous studies have found an inconsistent relationship between travel cost and intentions to revisit, hence requiring further investigation in the future (Abulibdeh, Zaidan, 2017; Elston, Draper, 2012; Yodsuwan, Pathan, Butcher, 2020). Therefore travel costs should be empirically examined to see if they serve as a factor influencing international tourists to revisit a MICE destination.

Attraction is described as the ability of the host destination to provide places of interest and attractions to MICE attendees (Hashemi et al., 2020). The concept of destination attractiveness has attracted the interest of tourism researchers (Ćulić et al., 2021). Destination attractiveness is widely recognized as a determinant of tourism development, consisting of the destinations’ specific features and attributes that encourage tourists to visit a particular place (Ćulić et al., 2021). Ćulić et al. (2021) clarified that tourism attractiveness includes the destination’s physical attributes and natural resources such as its climate, beaches, relaxation areas, and cultural resources such as historical monuments.

In the tourism context, Crouch and Louviere (2004) considered destination attractiveness as the main element of a destination and the principal factor that motivates tourists to visit. In the same vein, Bi, Yin and Chen (2020) confirmed that destination attraction is the key motivator and pull factor for individuals’ destination choice. De Nisco et al. (2015) also pointed out that destination attraction is one of the primary determinants of a person’s intentions to return to a destination. Ćulić et al. (2021) found that destination attractiveness impacts revisit intentions.

In a conference context, destination attraction could be described as the capability of the host destination to offer places of interest and attractions to conference attendees (Getz, Page, 2016). In the past, only big capital cities could host a convention due to high-level attractions and accessibility (Barkiđija Sotošek, 2020). With the rapid construction and expansion of convention centres and better facilities in today’s market, many smaller cities are now attracting large conventions as well (Barkiđija Sotošek, 2020). Park et al. (2014) clarified that the attractiveness of a destination is considered a key criterion for selecting a convention location. Hashemi et al. (2020) asserted that the attractiveness of the destination is a significant factor in the maximization of the economic benefits generated from the expenditures of conference attendees. Therefore, destination attraction is important for visitors of business events (Whitfield et al., 2014).

Countries with many attractions have a competitive advantage in attracting international tourists (Cró, Martins, 2018). Hashemi, Marzuki and Kiumarsi (2018) stated that MICE destinations with popular tourist activities and attractions have the capacity to achieve greater attendance due to their attractiveness. Furthermore, destinations which provide many attractions motivate organizers to conduct MICE events and encourage tourists to select a destination and revisit it (Anas et al., 2020). Related studies confirmed that destination attractiveness is still a critical factor influencing people to attend or re-attend a conference (Choi, 2013; Ryu, Lee, 2013; Yoo, Chon, 2008).

Oppermann and Chon (1997) also claimed that destination attractions including shopping, other local attractions, and recreational activities attract attendees to MICE events. Zhang, Leung and Qu (2007) highlighted the importance of destination attractiveness, and clarified that it is one of the location factors. Destination attractiveness plays a vital role in the decision-making process when considering attending an association conference (Jago, Deery, 2005), especially if the destination’s features support the notion that the conference destination is interesting and exotic. Rittichainuwat, Beck and Lalopa (2001) separated the factors that motivate people to attend a conference and factors which may inhibit attendance. They underlined the importance of sightseeing as a motivator, a dimension that is clearly linked to destination attractiveness. Kang, Suh and Jo (2005) identified attractions as one of the most important attributes of business event destinations. Several studies (Severt et al., 2007; Yoo, Chon, 2008; Zhang, Leung, Qu, 2007) underlined the importance of attractions in influencing participation at MICE events.

Another study by Choi (2013) reported that site attraction has a significant relationship with behavioural intentions in the context of a conference destination. Maulida, Jasfar and Hamzah (2020) examined the relationship between travel motivation and revisit intentions using a sample of 250 foreign tourists engaged in sporting and event activities in Sri Lanka. The study found that destination attraction has a positive impact on revisit intentions. A study involving 250 respondents examined tourist intentions to revisit heritage tourism resources in Yogyakarta using destination attractiveness, destination quality, tourist motivation and tourist satisfaction as variables. The results showed that attraction has a positive association with intentions to revisit (Puspitasari, Sugandini, Istanto, 2020).

Thiumsak and Ruangkanjanases (2016) studied 189 international tourists and found that the attractiveness of a destination has a positive correlation with revisit intentions. In the same vein, Sianipar et al. (2021) studied 5000 domestic tourists and found that tourist attraction to tourism village-related trips to Indonesia has a positive influence on their intentions to revisit the destination. Another study by Baniya, Ghimire and Phuyal (2017) found that the pull factor of attraction is significantly related to international tourists’ intentions to revisit Nepal. The same result was found by Ćulić et al. (2021) as well as Ngoc and Trinh (2015) i.e. that destination attractiveness has a direct effect on revisit intentions.

Meanwhile, Hashemi et al. (2020) examined the relationships between the dimensions of perceived quality, attendees’ needs, and behavioural intentions to attend conferences using a sample of 295 international attendees to 14 academic conferences in Malaysia. The findings showed that site attraction has no significant association with behavioural intentions. Another study by Wang, Feng and Wu (2020) explored the key factor of medical tourism and its relationship with tourism attraction and re-visit intentions. The study found that tourism attraction does not influence re-visit intentions. Gračan, Barkiđija Sotošek and Torbarina (2021) observed that site attraction does not predict future behavioural intentions for those who attend one convention per year, and it cannot predict behavioural intentions to re-visit a specific convention. The result is supported by several previous studies which showed the non-significant influence of site attraction on re-visit intentions (Wang, Feng, Wu, 2020; Yang, Sharif, Khoo-Lattimore, 2015).

In summary, the factor of attraction has received considerable research attention in developed and developing countries. However, prior studies on the relationship between attraction and intentions to re-visit had recorded inconsistent findings; hence, further investigation is required in the future. Qi, Smith and Yeoman (2019) also recommended further investigation on the factor of attraction. Therefore, the factor of attraction should be empirically tested to see if it serves as a factor influencing the intentions to revisit a MICE destination.

Accessibility can be defined as the way tourists move from their place of residence to a chosen destination (Gutiérrez et al., 2019). According to Jamaludin and Kadir (2012), accessibility in the context of tourism can be regarded is terms of the distance, time and costs of reaching a destination using an external transport from the tourist market. Go and Govers (1999) described accessibility as how delegates travel to and from a conference site. It also refers to the physical distance from the tourist destination to the host destination and the ease or difficulty of reaching it (Alananzeh, 2012). Accessibility could also be described as how easy it is to reach desired destinations from the place of residence (Hashemi et al., 2020).

Related works pointed out that accessibility is one of the most critical determinants of a tourist’s destination choice and which plays a vital role in the positioning and competitiveness of destinations (Gutiérrez et al., 2019; Houdement, Santos, Serra, 2017). Roslan, Ramli and Choy (2018) indicated that accessibility is a vital prerequisite for the survival of tourism because it links tourists to destinations. Anas et al. (2020) asserted that accessibility is an essential factor in tourism and is associated with tourists and destinations. Furthermore, Hansson et al. (2019) clarified that accessibility which includes travel time, comfort, and trip length is also vital in determining customer satisfaction (Ortaleza, Mangali, 2021). Accessibility and infrastructure have great influence on travel because a modernized road network leads to an increase in the number of tourists to a destination as well as encouraging re-visitations (Ortaleza, Mangali, 2021). Accessibility influences tourists because road quality and infrastructure including the means of transporting tourists from one place to another affect tourists’ experience and overall quality of stay (Ortaleza, Mangali, 2021). Consequently, Ćulić et al. (2021) asserted that destination accessibility has a long history of being recognized as a major pull factor.

In the MICE context, Barkiđija Sotošek (2020) clarified that MICE destinations are evaluated based on their accessibility. In the past, only big capital cities could host a convention due to their high-level attractions and accessibility (Barkiđija Sotošek, 2020). However, today’s construction technology has enabled even smaller cities to be accessible enough to hold large conventions. Accessibility is considered one of the main characteristics that tourists think of when choosing a MICE destination (Anas et al., 2020). Alananzeh, (2012) explained that international MICE participants look to accessibility before, during and after attending MICE events. Other studies also indicated accessibility as a key factor in encouraging attendees to reach MICE destinations (Cró, Martins, 2018; Whitfield et al., 2014; Yoo, Chon, 2008; Zhang, Leung, Qu, 2007).

Furthermore, Whitfield et al. (2014) indicated that accessibility is an important factor for MICE tourists in reaching an event destination. Zhang, Leung and Qu (2007) highlighted the importance of destination accessibility as one of the location factors analyzed from three elements: trip distance, direct flight, and ease of visa application. The study by Alananzeh, (2012) clarified that accessibility could be measured by the relative difference in time, cost, distance, or effort required to access different destinations based on the demand side. Barkiđija Sotošek (2020) asserted that less accessible destinations mean longer journeys and the use of various means of transportation for the attendees. The attendees of MICE events take into account the accessibility of the destination because it is largely related to the travel costs.

Hence, if the MICE event is held in a renowned destination with high accessibility, attendance increases significantly and leads to intentions to revisit the same event (Barkiđija Sotošek, 2020). Otherwise, if the MICE activities are held far away from the city, it will be hard for the participants to reach the destination and this will ultimately affect their decision to attend or re-attend the event (Anas et al., 2020).

The impact of accessibility on behavioural intentions has been investigated in previous studies which documented a significant link (Jung, Tanford, 2017; Kim, Lee, Kim, 2012; Lee, Min, 2013; Mair, Lockstone-Binney, Whitelaw, 2018; Ryu, Lee, 2013). In a study of the relative importance of the attributes of business event destinations, Kang, Su and Jo (2005) found destination accessibility to be the most important attribute. Lee and Min (2013) proposed that accessibility is a factor that is highly considered in the decision to attend a conference. A study was conducted to examine the factors affecting tourists’ return intentions to Vietnam as mediated by destination satisfaction using a sample of 301 leisure tourists. The results showed that accessibility significantly and positively affects tourists’ return intentions (Ngoc, Trinh, 2015). Another study by Giao et al. (2020) investigated the factors that affect domestic tourists’ revisit intentions using a sample of 550 domestic tourists who had visited Vietnam in the last quarter of 2019. The findings showed that accessibility is positively associated with revisit intentions.

A further study examined the relationships between the dimensions of perceived quality, attendees’ needs, and behavioural intentions to attend conferences using a sample of 295 ‘international attendees of 14 academic conferences in Malaysia. The findings showed that only accessibility and ‘self-congruity’ are positively associated with behavioural intentions (Hashemi et al., 2020). These results were also confirmed by Haneef (2017), Lee and Lee (2017), while Çapar and Aslan (2020) found that accessibility is significantly linked to tourists’ behaviour.

In contrast, the study carried out by Ingkadijaya, Bilqis and Nurlaila (2021) on the influence of tourism product attributes on revisit intentions to culinary tourism destinations involving a sample of 100 domestic tourists revealed that accessibility has no significant effect on revisit intentions. Another study by Hashemi, Marzuki and Kiumarsi (2018) found that accessibility is negatively correlated with behavioural intentions. Gračan, Barkiđija Sotošek and Torbarina (2021) found that accessibility does not predict future the behavioural intentions of those who attend one convention per year, but it does significantly predict the behavioural intentions of those who visit more than one. Similarly, Luvsandavaajav and Narantuya (2021) found that the pull factor of accessibility has no direct effect on revisit intentions. In the same vein, Ćulić et al. (2021) found that accessibility has no significant effect on revisit intentions. Ingkadijaya, Bilqis and Nurlaila (2021) found that accessibility components such as easy access are not important attributes that determine the decision of tourists to revisit.

Hence, it can be noted that accessibility is essential in the context of developed and developing countries. However, past studies on the relationship between accessibility and revisit intentions had reached inconclusive results; hence, more future investigations are needed. Micić, Denda and Popescu (2019) also suggested further research be conducted on the factor of accessibility. Therefore, accessibility should be tested to see if it serves as a factor influencing the intentions to revisit a MICE destination.

Overall, it is evident that the two push factors and the four pull factors discussed above could have an influence on the revisit intentions to a MICE destination. A theoretical model for examining this impact is presented in Figure 1.

This article has critically appraised past literature using the integrative review approach to determine the factors influencing MICE destination revisit intentions. For practitioners, this review could be helpful because identifying the factors that influence the revisit intentions of international MICE tourists could assist organizers design an event through an effective policy to improve these influencing factors. For researchers, understanding factors that influence revisit tourists to MICE destinations could help researchers formulate possible strategies for increasing the attractiveness to MICE tourists and improving the economic level of destinations. However, it is recommended that future research on this topic attempts to test the proposed relationships. Empirical data from such studies could particularly help MICE practitioners in developing nations especially those that have invested heavily in MICE infrastructures yet suffer from a decreasing number of MICE participants over the years. Understanding the push and pull factors of MICE destinations could help destination managers understand how they could improve in order to make their MICE destinations more attractive to visitors.

Uniwersytet Północnej Malezji, Wyższa Szkoła Turystyki, Hotelarstwa i Organizacji Imprez Masowych, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8281-3384, e-mail: ammar.alramadan@hotmail.com

Uniwersytet Północnej Malezji, Wyższa Szkoła Turystyki, Hotelarstwa i Organizacji Imprez Masowych, Centrum Badań nad Turystyką i Hotelarstwem Wysp Langkawi, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2217-0989, e-mail: azilah@uum.edu.my

ABSTRAKT

Związek między czynnikami push (pchania) i pull (przyciągania) z zamiarem ponownego odwiedzenia destynacji często był badany w kontekście turystyki ogólnej. Niewiele natomiast wiadomo na temat czynników wpływających na zamiary ponownej wizyty w miejscach docelowych MICE pomimo licznych korzyści społeczno-ekonomicznych, jakie wiele krajów uzyskało dzięki tej branży. W niniejszym artykule podjęto próbę wypełnienia luki w wiedzy za pomocą krytycznego przeglądu literatury przy użyciu zintegrowanego podejścia przeglądowego. Przegląd, krytyczna analiza i synteza głównej literatury pozwoliły ustalić, że dwa czynniki push, tj. tworzenie sieci kontaktów i możliwości edukacyjne, oraz cztery czynniki pull, tj. wizerunek miejsca docelowego, koszty podróży, atrakcyjność i dostępność, wpływają na zamiary ponownej wizyty w destynacji MICE. Następnie zaproponowano teoretyczny model relacji między tymi czynnikami a zamiarami ponownego odwiedzenia ośrodka MICE.

SŁOWA KLUCZOWE

czynniki push, czynniki pull, zamiar ponownej wizyty, MICE

Sposób cytowania (styl APA): Ramadan, A., Kasim, A. (2022). Factors influencing MICE destination revisit intentions: Aliterature review. Turyzm/Tourism, 32 (1), 185–217. https://doi.org/10.18778/0867-5856.32.1.09

INFORMACJE O ARTYKULE: Przyjęto: 2 marca 2022 r.; Zaakceptowano: 24 maja 2022 r.; Opublikowano: 28 września 2022 r.

Turystyka MICE do 2020 r. była jednym z najszybciej rozwijających się segmentów branży turystycznej (Anas i in., 2020; Lee, Koo, Chung, 2019; Nasir, Alagas, Nasir, 2019), przynoszącym od dwóch do czterech razy większy dochód niż inne sektory turystyki (Anas i in., 2020; Lee, Koo, Chung, 2019). Niemało państw odniosło korzyści ekonomiczne z biznesu turystycznego MICE[1], który pomógł podnieść standard życia w różnych miejscach docelowych (Nakip, Gökmen, 2018). MICE przyniosło destynacjom profity także na wiele innych sposobów, w tym przez wspieranie i wzmacnianie relacji między gospodarzami a uczestnikami, przyciąganie zamożnych turystów, wzmacnianie międzynarodowych powiązań gospodarczych, wprowadzanie usprawnień przy tworzeniu miejsc pracy, ograniczanie sezonowości w miejscu docelowym oraz pomoc wielu krajom w rozwoju powiązanych usług i infrastruktury (Alananzeh i in., 2019; Anas i in., 2020; Lee, Koo, Chung, 2019; Mhango, 2018; Mureșan, Nistoreanu, 2017; Nasir, Alagas, Nasir, 2019).

Choć dużo rządów uważa MICE za ważny element zwiększania przychodów z turystyki (Cró, Martins, 2018; Lee, Back, 2005; Whitfield i in., 2014), niektóre kraje rozwijające się nie są w stanie rentownie sprzedawać oferty swojej branży MICE (Phophan, 2017). Co więcej, spore pieniądze generowane przez MICE na całym świecie nie mają wpływu na wskaźniki przychodów w niektórych słabo rozwiniętych krajach, takich jak Jordania, gdzie nadal są one niewystarczające (Jordan Tourism Board, 2016). Dochód MICE w tym kraju w 2018 r. wyniósł ok. 50 milionów dolarów, co jest niezwykle niskim rezultatem w porównaniu z innymi miejscami i stanowi zaledwie 1,7% całkowitych dochodów z turystyki w Jordanii (Gedeon, Al-Qasem, 2019). Niezdolność tego kraju do generowania znacznych przychodów z biznesu MICE pomimo posiadania unikatowych zasobów turystycznych powoduje, że pojawiają się pytania dotyczące braku zachęty do odwiedzenia lub ponownego odwiedzenia Jordanii jako miejsca docelowego MICE, a także potrzeby dalszego rozwijania obiektów i usług MICE, aby przyciągnąć międzynarodowych turystów.

Według teorii planowanego zachowania intencje ponownej wizyty są pochodną intencji behawioralnych i silnym czynnikiem prognostycznym zachowań (Ajzen, 1991). Zamiar powrotu turystów do destynacji to jeden z kluczowych tematów w literaturze przedmiotu, który zwrócił uwagę wielu badaczy i praktyków (Abbasi i in., 2021; Bi, Yin, Chen, 2020; Fitri, 2021; Weru, 2021). Problem intencji powrotu był omawiany przede wszystkim w kontekście sportu (Allameh i in., 2015; Cho, 2021), megawydarzeń (Zhang, Liu, Bai, 2021), wydarzeń kulturalnych (Yen, 2020) oraz festiwali (Al-Dweik, 2020).

Niestety, w niewielu badaniach analizowano zamiary ponownej wizyty w ramach MICE (Bi, Yin, Chen, 2020; Fitri, 2021; Yodsuwan, Pathan, Butcher, 2020), a przecież behawioralne zamiary powrotu do miejsca docelowego są bardzo istotne dla zapewnienia udanego wydarzenia MICE, szczególnie w krajach rozwijających się (Fitri, 2021). Mimo że liczne badania dotyczące turystyki i wydarzeń skupiały się na czynnikach wpływających na decyzje turystów o powrocie do destynacji (Abbasi i in., 2021; Al-Dweik, 2020; Allameh i in., 2015; Baniya, Ghimire, Phuyal, 2017; Bi, Yin, Chen, 2020; Fitri, 2021; Susyarini i in., 2014; Tsai, 2020; Wicaksono, Setyaningtyas, Kirana, 2021; Yeoh, Goh, 2017), to rzadko wykonywano analizy czynników determinujących chęć ponownego udziału w wydarzeniu w kontekście krajów słabo rozwiniętych (Al-Dweik, 2020; Bi, Yin, Chen, 2020).

Prezentowane opracowanie ma na celu wypełnienie luki w wiedzy za pomocą krytycznego przeglądu literatury na temat zmiennych decydujących o zamiarze ponownego odwiedzenia miejsca wydarzenia przez turystę. Zrozumienie intencji kolejnej wizyty w destynacji MICE jest kluczowe, ponieważ selekcja miejsc jest ważną częścią całej podróży MICE. Wybór lokalizacji, w której mogłaby się odbywać konferencja, był postrzegany jako główny czynnik wpływający na decyzję o odwiedzeniu lub ponownym odwiedzeniu miejsca docelowego (Baloglu, Love, 2005; Crouch, Ritchie, 1997; DiPietro i in., 2008; Elston, Draper, 2012; Lee, Back, 2008; Yoo, Chon, 2008). Te wczesne badania wyjaśniają, że miejsce konferencji jest ważnym czynnikiem nie tylko dla organizatora, ale także dla uczestników (Lee, Koo, Chung, 2019). Dlatego konieczne jest zrozumienie, jak wybrać odpowiednie miejsce zorganizowania i przeprowadzenia konferencji (Sperstad, Cecil, 2011).

W niniejszym artykule dokonano krytycznego przeglądu literatury, aby zaproponować ramy dla zrozumienia czynników wpływających na zamiary ponownej wizyty w destynacji MICE. Przyjęte podejście nosi nazwę przeglądu integracyjnego (ang. integrative review) (Onwuegbuzie, Frels, 2016) i najlepiej odpowiada celowi artykułu. Ponadto przegląd integracyjny jest najczęstszą formą przeglądu w naukach społecznych. Podejście obejmuje krytyczny przegląd i syntezę literatury na temat zmiennych, które wpływają na zamiary turystów, żeby kolejny raz odwiedzić miejsce organizacji wydarzenia, przed wygenerowaniem modelu do zrozumienia czynników oddziałujących na chęć ponownej wizyty w destynacji MICE. Jednak ze względu na ograniczony dostęp do literatury na temat MICE per se nasz przegląd integracyjny został przygotowany głównie na podstawie literatury turystycznej i ogólnej dotyczącej wydarzeń w celu ustalenia przekonujących dowodów na obecność czynników wpływających na zamiary ponownej wizyty MICE. W poniższych sekcjach przegląd rozpoczyna się od wyjaśnienia pojęcia i typologii turystyki MICE, po której następuje krytyczna analiza intencji powtórnej wizyty i czynników na nią wpływających.

Skrót MICE oznacza rodzaj turystyki obejmującej spotkania, podróże motywacyjne, zjazdy i wystawy, podobnie MEI (ang. meetings, events, incentives – ‘spotkania, wydarzenia, wyjazdy motywacyjne’) lub MIT (ang. meetings, incentives, trade shows – ‘spotkania, wyjazdy motywacyjne, targi’) w Stanach Zjednoczonych, lub MCIT (ang. meetings, conventions, incentive travels – ‘spotkania, zjazdy, podróże motywacyjne’) w Kanadzie (Bao, 2017). W Australii z kolei znany jest pod nazwą „wydarzenia biznesowe”, a w Europie to „przemysł spotkań”. Ten rodzaj turystyki jest opisywany jako planowany z góry i przeznaczony dla dużych grup osób do określonych celów (Alananzeh i in., 2019) oraz jako kluczowy obszar rozwoju dla sektora turystyki na całym świecie (Buathong, Lai, 2017). Dla Leonga (2007) MICE to rodzaj turystyki, w której grupy uczestników gromadzą się, żeby osiągnąć poszczególne cele. Były też definicje podawane przez uczonych i autorytatywne stowarzyszenia, opisujące MICE jako akronim (od ang. słów: meetings, incentive travels, conventions, exhibitions – ‘spotkania, podróże motywacyjne, konwencje, wystawy’) (Chen i in., 2012; Lee, 2016).