Cebu Technological University, Department of Tourism Management, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0775-6156, e-mail: kafferineyamagishi@gmail.com

Cebu Technological University, Center for Applied Mathematics and Operations Research, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5050-7606, e-mail: lanndonocampo@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

This work advances previous work on greening festival management by using the Sinulog festival as a case in point, as it has conditions resonating with most festivals in the Philippines and some other emerging economies. An analysis based on strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) was constructed based on an earlier work that provided some insights on assessing the green management initiatives of the festival organization. The weaknesses in the SWOT analysis are considered inputs to a root cause analysis to identify the fundamental green management issues. The two analyses suggest that the festival organization has a limited view of the green management agenda. Four elements are found crucial for greening the Sinulog festival: crafting an environmental policy; allocating financial and human resources for implementing greening initiatives; partnership agreements with local environmental institutions; and partnership agreements with sponsors who proactively support the environmental agenda. These insights may have value for other festivals in their greening agendas.

KEYWORDS

festival tourism, green management, SWOT analysis, root cause analysis

How to cite (APA style): Yamagishi, K., Ocampo, L. (2022). Evaluating the greening agenda of festivals: The case of Sinulog. Turyzm/Tourism, 32 (1), 115–140. https://doi.org/10.18778/0867-5856.32.1.06

ARTICLE INFORMATION DETAILS: Received: 12 August 2021; Accepted: 17 May 2022; Published: 31 May 2022

Despite tourism’s widely acclaimed economic benefits, its corresponding adverse environmental impacts have been increasingly gaining attention. Transport-related emissions from tourism activities, for instance, contributed 5% to global carbon emissions in 2016, and this is projected to increase to 5.3% in 2030 (UNWTO, 2020). The awareness of the role of tourism in climate change and growing social and environmental consciousness have shaped interests in sustainability (Laing, Frost, 2010; Mair, Jago, 2010). The adverse impacts of tourism have driven the industry to integrate practices supporting the sustainability agenda in their operations, and tourists are now becoming more aware of their environmental responsibility (Andereck, 2009). One crucial form of tourism with considerable ripple impacts across the value chain is event tourism. Governments have made event tourism a development tool to generate economic resources and promote destinations to potential tourists (Getz, 2008; Yuan, 2013). Event tourism provides economic benefits by attracting bulk tourist arrivals and due to the many tourists participating in event tourism activities, the sector has significant environmental and social impacts, both positive and negative (Alampay, 2005; Buathong, Lai, 2017). Concerns on biodiversity, cultural heritage and ethical considerations arise with managing events (Jones, 2001), so tourist destinations need to adapt to the new trend and promote local cultures and traditions that highlight heritage preservation (Stankova, Vassenska, 2015). There has been a growing interest in introducing environmental sustainability into managing event tourism so that adverse environmental impacts are reduced. Globally, the growth of events has been reported to effectively address environmental concerns (Ahmad et al., 2013); such as the Byron Bay International East Coast Blues and Roots Festival (Bluesfest) in Australia (Laing, Frost, 2010) and the Burning Man Festival in the USA (Kozinets, 2002; Sherry, Kozinets, 2007). The event industry is now challenged to be more accountable in curbing its negative impacts on the environment (Mokhtar, Deng, 2014), however, organizing events has left much to be desired when evaluating its contribution to a destinations’ economic, social, and environmental development (Getz, 2017).

Festival tourism has gained increasing attention from scholars and practitioners within the event tourism sector with research emerging in the tourism literature in the late 1980s and early 1990s (Laing, 2018). Various works in the festival tourism literature focused on economic impacts (Litvin, Pan, Smith, 2013; Nagy, Nagy, 2013; O’Sullivan, Jackson, 2002; Rao, 2001), socio-economic development (Doe et al., 2022), attendee profiles (Prentice, Andersen 2003; Song, Xing, Chathoth, 2015), operations and management (Frisby, Getz 1989; Frost, Laing 2015), sustainability (Berridge, Moore, Ali-Knigh, 2018; Boggia et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2019; Zou et al., 2021), food festivals (Kim, 2015), festival tourism development (Ma, Lew, 2012), and the staging of festivals (Mariani, Giorgio, 2017; Ralston et al., 2007). Getz (2010) organized a comprehensive and structured literature review on various themes associated with festival tourism, such as authenticity, political and social/cultural meanings and discourse, and religion. On the other hand, despite the adverse environmental impacts previously highlighted (Ahmad et al., 2013; Cudny, 2013; O’Sullivan, Jackson, 2002), the emerging literature considers festivals as a medium for promoting the green agenda. Some works reported their impacts, planning and motivation towards green management (Laing, 2018). Mair and Laing (2012) identified the drivers and barriers for the greening of festivals and evaluated how events could promote sustainable behavior. Martinho et al. (2018) explored solid waste prevention and management measures by monitoring the Andanças Festival (Portugal) in 2014 and 2015. Wong, Wan and Qi (2015) highlighted the influence of green event attendees’ involvement, its effect on the perceived green value, and other direct and indirect effects. Relevant works on green festival management in the literature highlight strategies and best practices (Dodds, 2018), socio-cultural concerns (Small, Edwards, Sheridan, 2005), environmental impact (Collins, Cooper, 2017), waste (Rafiee et al., 2018; Zelenika, Moreau, Zhao, 2018) and green intentions (Boo, Park, 2013).

Despite advances in the literature, streamlining how to green festivals remains a crucial gap, sustainability in the context of events has only limited discussion even concerning threats to the environment (Arcodia, Cohen, Dickson, 2012). Literature on the adverse impacts of festivals and festival tourism have become relevant research topics (Getz, 2010). To this end, the inclusion of a case study of the greening of festivals would serve as a jumpstart for improving the festival management literature by providing managerial and policy insights from the diverse initiatives of the greening process. Thus, this work addresses this gap by providing an in-depth analysis of the organization of a festival in view of the greening agenda. Specifically, it presents a case study of the Sinulog festival celebration in Cebu, the Philippines, highlighting the greening process. Sinulog is one of the most popular festivals in the Philippines where local people celebrate their culture and religious faith. It lasts for weeks, with various cultural and religious activities, culminating in a festive street dance parade. However, since it attracts a high crowd density, with millions of people gathering in a relatively small area, the festival has faced a rising number of environmental issues for years, mainly concerning waste management. The most recent event generated 219 tonnes of solid waste along the parade route in just one day (Yamagishi, Gantalao, Ocampo, 2022). Rieder (2012) has emphasized that the Philippines have seen the significance of adopting and implementing various programs, initiatives and approaches that are both receptive and responsive to environmental protection and conservation. Hence, evaluating the festival’s environmental management agenda generates critical inputs to future courses of action.

The main contribution of this work is to provide in-depth analysis and assessment of the festival organization in terms of its green management, and offers possible pathways for greening the Sinulog festival by extending the work of Yamagishi, Gantalao and Ocampo (2022). First, the findings and insights of Yamagishi, Gantalao and Ocampo (2022) obtained from the PDCA cycle (i.e., main clauses of the Event Sustainability Management System or ISO 20121) became inputs to a SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats) analysis. As a management tool SWOT analysis identifies these factors to inform the design of organizational goals and subsequent strategies for achieving them (Ommani, 2011). It provides the organization with a better understanding of its resources and capabilities (Namugenyi, Nimmagadda, Reiners, 2019) and a historical context and possible solutions to existing or impending problems (USDA, 2008). To address the “weaknesses” factors of the SWOT analysis, fundamental green management issues were obtained through the Root Cause Analysis (RCA). RCA is a structured and systematic process to identify the causes of a problem (Sweis et al., 2018) and upon finding the causes, counteractive measures are proposed to mitigate them. The countermeasures identified in the RCA serve as bases for further greening the festival. Possible actions were discussed to inform future scholarship in this field and provide relevant managerial and policy insights for festival organizations. The insights of their management practices can serve as both a benchmark and guidelines for greening festivals.

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 reviews the relevant literature on greening events; discussion of the methodology is presented in Section 3; Section 4 provides a background of the case study; analysis, via SWOT and RCA is shown in Section 5; Section 6 highlights the managerial and policy insights; and it ends with concluding remarks in Section 7.

Events are regularly held activities that offer unique experiences brought about by the dynamics of several factors (Getz, 2008). Getz and Page (2016) characterized four main categories of planned event in an event tourism context:

Of these categories, festival tourism is deemed one of the fastest-growing tourism types, emphasizing cultural exchange, whether on an international, national or local scale. Festivals are socio-cultural celebrations that attract tourists who generate an economic impact (Frisby, Getz, 1989). Festivals represent the culture, heritage, history and intercultural communication of a specific community, while invigorating environmental consciousness and deepening cultural awareness (Duran, Hamarat, 2014). Governments currently hold festivals to attract tourists to boost economic development and cultural tourism (Raj, Vignali, 2010). However, despite their attractive economic and socio-cultural appeal, festivals have adverse impacts on the total environment, such as pollution or misrepresentation of cultural heritage resulting in conflicts between the locals and the tourists (Cudny, 2013). For instance, festivals are at risk of losing their authenticity due to customizing the festival proceedings according to tourists’ preferences. As a result, some tourists may feel cheated and local artists discouraged, negatively affecting the festival (Gaworecki, 2007).

Organizations managing festivals typically have insufficient resources (e.g. financial capital, time and expertise) and are often organized by local authorities with generally poor planning and strategy skills (Pugh, Wood, 2004; Wood, 2008; Wood, 2009). Getz and Frisby (1988) posited that festival organizers only operate for a specific period in a year and are highly dependent on volunteer groups and individuals who may lack the training and expertise associated with the operation of a festival. Sustaining the attractiveness and the capacity of destinations to host events is dependent on the quality of the environmental resources at the destination (Yuan, 2013). However, on this note, festivals are often deemed threats to the natural environment as they draw a large number of attendees to a specific space and time while utilizing resources (Zifkos, 2015). The event industry is compelled to be more responsible in its managerial decisions and create positive environmental impacts (Mokhtar, Deng, 2014). In their work, Yamagishi, Gantalao and Ocampo (2022) found that most festival organizations, at least in their conditions, have a myopic green management agenda denying salient environmental threats linked to managing festivals. Yuan (2013) presented three main concerns of environmental sustainability in managing events:

The event industry is compelled to be more responsible for creating positive environmental impacts (Mokhtar, Deng, 2014) and in the event industry, stakeholders are increasingly interested in adopting green initiatives to enhance competitiveness (Mankaa et al., 2018; Whitfield, Dioko, 2012). Green events incorporate sustainable measures and practices in their management and operations (Laing, Frost, 2010; Martinho et al., 2018; UNEP, 2009). Tölkes and Butzmann (2018) highlighted the main characteristics of green events and festivals:

Local authorities commonly support and organize green events and festivals to motivate and promote sustainable behavior among attendees and local communities (Mair, Laing, 2013; Tölkes, Butzmann, 2018). Green festivals have a unique sustainability characteristic through the lens of entertainment, products and services, and aesthetics (Tölkes, Butzmann, 2018). They have embraced a green agenda that emphasizes minimal indirect adverse impacts through resource conservation, and the loss and deterioration of the natural environment (Laing, Frost, 2010). This green agenda is usually developed through local community involvement with various relevant sectors to implement local, sustainable development strategies (Laing, Frost, 2010). Festivals and event companies have integrated environmental practices to reduce their adverse effects on the environment through proper waste management, reducing water and energy consumption, supporting local suppliers and providing environmental awareness for the attendees (Graci, Dodds, 2008; Mankaa et al., 2018). Organizations advocating green festivals save resources by promoting recyclable materials and resource reuse to minimize the negative impacts of an event on the environment. Considered part of a pressing trend, several event organizations and managers aim to reduce their adverse environmental impacts but have limited knowledge of how to start (Ahmad et al., 2013; Laing, Frost, 2010). Organizations are willing to inculcate these sustainability practices into their events, however, some are reluctant because participants are unwilling to spend more to cover the cost of these green measures, and sponsors are less supportive due to the lack of information and knowledge about sustainability (Mokhtar, Deng, 2014). Among several sustainability issues relevant to events, waste is considered a priority for large events with many attendees (e.g. festivals) (Laing, Frost, 2010).

Currently, there are three major standards for making events sustainable. These are the Convention Industry Council Accepted Practices Exchange (APEX) and ASTM (i.e. a certified international standard development organization) commonly referred to as APEX/ASTM, Global Reporting Initiatives (GRI), and ISO 20121 standards.

An initiative of the Events Industry Council, APEX is`moting non-profit organizations to embrace industry-wide practices that aim to enhance efficiency in the MICE industry. Compared to ISO 20121, the APEX/ASTM standard is more specific and contains performance-based criteria for planners and suppliers. It uses a checklist and scoring scale to measure an event’s performance covering nine areas:

The GRI, an internationally known NGO that collaborates with the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP), has a sustainability reporting framework for transparency and reliability. It was created in 1997 with the UNEP and the Coalition for Environmental Organization, a United States non-governmental organization, to augment the quality, structure and coverage of sustainability reporting. The strengths of the GRI are in its guidelines for sustainability reporting and it consists of social, environmental, economic, and institutional sustainability dimensions divided into eight sub-indicators and 15 leading indicators.

ISO 20121, or Event Sustainability Management System, provides an approach to identifying key sustainable issues, including selecting venues, operation procedure, supplier chain, logistics and communication (ISO). While ISO 14001 (i.e. Environmental Management Systems) can be utilized for any business, ISO 20121 provides the framework, principles and specific requirements relevant to the event industry sector. With the release of ISO 20121, the event industry now has international standards for the sustainability of events implying that event suppliers and organizations must incorporate sustainability principles into their processes. It challenges organizations and relevant stakeholders to improve their processes on the way to continuous improvement. Also, it supports organizations to be creative and flexible in their delivery of event-related activities towards sustainability without compromising event objectives.

This research utilizes a case study method to gain a deeper understanding of a phenomenon (e.g. festival) under observation. Yin (2009) characterizes a case study approach as an empirical inquiry where the current phenomena have an in-depth and within a real-life context, and the boundaries between the phenomena and its context are unclear. In this work, the case of the Sinulog festival is put forward to examine the extent of green practice adoption in festivals. An in-depth interview was conducted to ask open-ended questions to obtain rich data and information (Guion, Diehl, McDonald, 2011) allowing insights to be gained from the interpretations of research participants and enables the researchers to understand the fundamental issues of the study (Miles, Huberman, 1994). In conducting in-depth interviews, seven stages are observed: thematizing, designing, interviewing, transcribing, analyzing, verifying and reporting (Kvale, 1996). Thematizing is stating the purpose of the interview; designing is the strategy to elicit the needed information through the interview process with an interview guide; interviewing denotes the structured discussion with the respondent/s; transcribing develops the verbatim text of each interview from the audio recording. On the other hand, analyzing evaluates the interview transcripts and classifies them into themes; verifying involves triangulation to examine the credibility of the gathered data; finally, reporting presents the results, including an analysis of how the results impact on and contribute to the research issue. In this work, the data gathered from in-depth interviews was supplemented with direct observation and documentation. Direct observation collects evaluative data where researchers observe their subjects in their natural environment without changing that environment. It is used when a study aims to assess a continuing behavioral process, event or situation (Holmes, 2013). Finally, a systematic process of evaluating the supporting documents was carried out, to analyze the data and interpret it to derive meaning, understanding and empirical knowledge (Bowen, 2009; Corbin, Strauss, 2008); it is also a means of triangulation (Denzin, 1970).

Yamagishi, Gantalao and Ocampo (2022) identified the executive director of the festival organization as the key informant with a critical role in achieving the objective of the research. The executive director has extensive knowledge of administering the Sinulog festival due to his significant experience and technical expertise. He is a full-time employee of the organization who has firsthand knowledge of the operations, providing insights into greening the festival.

The data used for this work was gathered primarily through the structured interview of the key informant, grounded on the insights provided in Yamagishi, Gantalao and Ocampo (2022) which measures the compliance of the festival organization towards green management using the PDCA cycle. The personal interview was recorded with consent and included open and projective questions that allowed the key informant to express his opinions based on the structured interview guide. The structured interview offers all the relevant details regarding the extent to which the festival organization practices green management and allows for open communication and dissemination of the required data. The UCLA Center for Health Policy Research, Key Informant Interviews, guided its implementation and extended the data of Yamagishi, Gantalao and Ocampo (2022) to further examine crucial elements for greening the Sinulog festival.

The recorded results of the key informant interview, based on Yamagishi, Gantalao and Ocampo (2022), were transcribed. Then, a thematic analysis was implemented on the transcribed data, a systematic process for identifying, analyzing, writing themes from the data, and arranging and defining the data set in substantial detail (Braun, Clarke, 2006). The study utilized the process of Braun and Clarke (2006) that provides clear and useful guidelines in conducting thematic analysis through a six-step framework of:

The themes are based on the research objectives; the themes within the data were undertaken in a theoretical or deductive manner and counter-checking was implemented on the findings via anchoring and supplementing additional article readings to strengthen the response. The results were also presented through various themes parallel to the objectives of the study.

SWOT analysis revolves around the context of environmental actors, which is a central process in business planning and strategic planning (Ghazinoory, Abdi, Azadegan-Mehr, 2011; Phadermrod, Crowder, Wills, 2019). SWOT is a practical analysis tool that has been utilized in various domain contexts such as strategy formulation (Rauch et al., 2015; Wang, Hong, 2011), medical tourism (Ajmera, 2017; Mohezar, Moghavvemi, Zailani, 2017), sports tourism (Roslan, Ramli, Choy, 2018), festivals (Carlsen, Andersson, 2011), and sustainable tourism (Navarro-Martínez et al., 2020). Note that this list is not intended to be comprehensive. Based on SWOT analysis, the identified weaknesses serve as the basis for root cause analysis (RCA) designed to examine and classify the root causes affecting an organization (Tomić, Spasojević Brkić, 2011). Understanding the root causes is crucial in ultimately preventing the reoccurrence of the problems revealed as weaknesses. Implementing the RCA involves four steps. First, data are collected to gain an in-depth knowledge of the problem under consideration, along with the identification of associated factors and possible root causes. More time is expected to be spent on this stage. Second, causal factors are organized and analyzed following the information obtained. In this step, possible gaps and deficiencies in knowledge are identified as the investigation advances. Third, root cause identification which comes after the causal factors are determined, involves utilizing a decision diagram to identify the primary reason for each causal factor. The diagram provides a structure for the reasoning framework by answering why causal factors exist. Fourth, recommendations are charted, and where possible countermeasures are developed to prevent future reoccurrence of the problems (Tomić, Spasojević Brkić, 2011). In this work, RCA is undertaken to identify the core green management issues. When the root causes are identified, measures to prevent their reoccurrence could be developed. After finding the root causes, countermeasures are designed to advance the green management performance of a festival.

In developing countries, tourism catalyzes additional revenue from foreign exchange, employment opportunities, linkages and economic diversification (Sahli, Nowak, 2007). As a case in point, the Philippine tourism industry is considered one of the drivers of economic growth (NEDA, 2017); recording around 8.26 million tourist arrivals in 2019 (DOT, 2020); and contributing around USD 51 billion in 2019, higher than the USD 45.6 billion in 2018 (PSA, 2020). This represents a 12.2% share of the economy as gauged by ‘Tourism Direct Gross Value Added’ (DOT, 2020). The country’s inbound tourism expenditure grew by 43.9% in 2017, and domestic tourism by 25.5%. Employment in the tourism industry increased by 1.8% in 2018 (PSA, 2020) and in 2018 was estimated at 5.4 million (PSA, 2019).

The Sinulog festival is one of the major festivals in the Philippines which give tribute to the Holy Child Jesus and is celebrated every third Sunday of January. The locals’ pride in their rich culture is demonstrated through dances, creative float displays and puppeteers. Every year, millions of tourists worldwide come to witness the festival’s grand parade. Due to its strategic location, natural features and infrastructure, the Cebu province, notably the city of Cebu itself, where the greatest Sinulog celebration is held, has the leverage to attract international and domestic tourists (Abocejo, 2015). Based on the report of GMR Megawide Cebu Airport Corporation, in 2019 (pre-pandemic levels), tourist arrivals reached 292,812 in Cebu for the Sinulog festival consisting of 157,920 domestic passengers and 134,892 international (Saavedra, 2020). In 2020, tourist arrivals were estimated to reach 336,000, where 174,000 will be domestic passengers, and 162,000 international (Saavedra, 2020). In 1980, the first Sinulog procession was held, and universities and colleges were invited to evaluate and improve the dance movements of the famed Basilica Minore del Sto. Niño de Cebu candle vendors (Yamagishi, Gantalao, Ocampo, 2022). The Sinulog project was later placed under the supervision of the Cebu City Historical Committee, which is an established entity, to conceptualize and organize the traditional Sinulog festival. Several key sectors were involved in the festival’s organization in 1981.

The festival organization has established additional contest categories, which have opened new markets without risking the essence of the event. The Sinulog festival can now be accessed on the internet via their official website. The Sinulog grand parade is the most awaited street party where there is a Mardi gras with the puppeteers showcasing their creativity in honor of the Holy Child Jesus. Other activities include photo exhibits and competitions, short films and Sinulog Idol singing competitions. Two different entities organize the Sinulog Festival: the cultural activities are arranged by the festival organization, and the church organizes the religious activities. Both entities work effectively through the efforts of the local authorities who are directly involved in the organization and management, as shown in Figure 1 with committees, working teams and volunteers to provide services during the festival. The festival organization has already built a good reputation and relationship with various sponsors (both local and international). The term Sinulog and its logo are the first festival-related assets registered with the Philippine Intellectual Property Office and it has been successfully organized for nearly four decades, making it one of the Philippines’ most significant and popular festivals.

Sinulog gained international recognition in 2018 and with this distinction, the local government has considered measures to improve the festival’s management, as it generates more tourists every year, both local and foreign. This growth is accompanied by specific issues like traffic congestion, crowd control, crimes and solid waste (Yamagishi, Gantalao, Ocampo, 2022). Regarding the solid waste generated by the festival, the local government has initiated some measures to address it. As a result, in 2020, local authorities collected only 131 tonnes of waste, which is 79 tonnes less than the 210 in 2019 (Erram, 2020). In 2018, Sinulog generated 219 tonnes of garbage on the parade route and nearby areas, according to the Department of Public Services (DPS) of Cebu City, requiring 586 personnel to clean up (Bongcac, 2018). The city generated 155 tonnes of garbage during Sinulog 2017, higher than the 110 collected in Sinulog 2016, primarily plastic bottles (Fernandez, 2017). The DPS inventory of Sinulog waste consists in the main of plastic bags, disposable water containers, food wrappings and fruit peel. The volume of solid waste collected in Sinulog 2015 was 197 tonnes, while Sinulog 2014 collected 174. This figure was also higher than the 187 tonnes in 2013 and 100 in 2012 (Demecillo, Florita, 2015). This trend (Figure 2) suggests that managing solid waste is deemed an important cause of concern in greening the Sinulog festival.

The Sinulog festival benefits the local economy by attracting millions of visitors each year, providing revenue for hotels and other tourism-related businesses. Through numerous contest categories, such as a talent contest, pageants and a film festival, it hopes to draw younger generations to reproduce the festival’s authenticity and character. According to the structured interview, the festival organization has no established vision-mission statement, which would provide a shared objective in organizational decision-making and represent a sense of identity to its personnel. The lack of a comprehensive organizational guide has severe implications for the planning, implementing and monitoring of the festival’s environmental management measures. The lack of a formal environmental policy that would govern all organization activities in greening the event is one significant ripple effect of such a gap. With Sinulog’s growing environmental concerns (e.g. resource use, energy consumption and trash generation), a lack of environmental policy would indicate a lack of environmental performance metrics. The festival organization’s environmental management activities can be characterized as a concrete waste management agenda with a myopic view of an overall environmental management perspective. The instructions set out on the organization’s website are insufficient to make a significant effort to reduce its negative environmental impact. The current environmental effort is highly dependent on the local government environmental office, which may lack direct control over the initiatives of the entire festival operation.

Table 1. SWOT analysis of the festival organization

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|

|

|

| Opportunities | Threats |

|

|

Source: authors.

The lack of a holistic plan for curbing the adverse impact of gathering a huge crowd of tens of millions of people remains a crucial gap that must be addressed in its environmental policy. The initiative of their Sinulog Garbage Watch Program was a good start; however, its effectiveness remains unknown primarily since 219 tonnes of garbage were collected in 2018, up from 155 tonnes in 2017. On the other hand, allocated resources in environmental initiatives are scarce, which must be considered in the planning stage. Greening the festival must be implemented with environmentally conscious partners. As the festival organization receives sponsorships from various partners, sponsor or partner selection must be contextualized within partners’ commitments to maintaining environmental efforts. Greater emphasis on the green partner selection process is an important direction for green festival management. Finally, performance evaluation post-festival must also address the environmental performance during the festival, according to material resource use, energy consumption and waste generation. Along this line, important indicators for measuring environmental performance must be institutionalized. With the given findings of the PDCA cycle reported in Yamagishi, Gantalao and Ocampo (2022), a SWOT analysis is presented in Table 1.

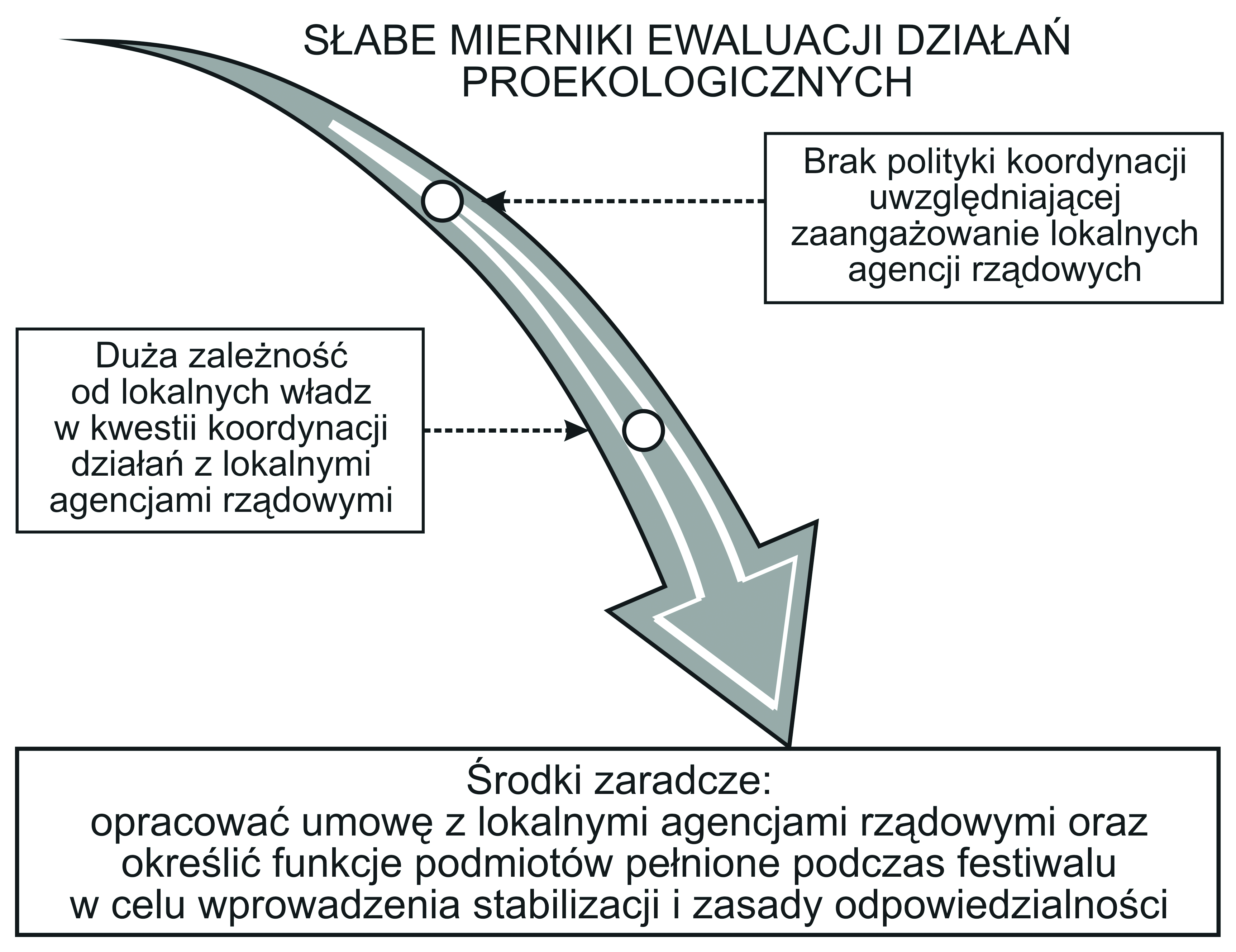

An RCA analysis was implemented to determine the causes of the nonconformance or weaknesses of the Sinulog festival organization. Figures 3 to 6 show the results of the RCA analyses for all ‘weakness’ factors. Future initiatives associated with process improvement would permanently mitigate, if not eliminate, these weaknesses. The root causes would serve as inputs to the continuous improvement plan.

The following provides a discussion of the possible countermeasures on the weaknesses of the festival organization for green management. Note that these countermeasures were obtained from the SWOT analysis and the RCA.

A policy manual describes the rules, policies and procedures that direct all festival organization stakeholders. It provides crucial information on the processes, employee expectations, other committees involved, and the organization’s performance standards. With policy standards in place, consistency, accountability and organizational culture would be shaped. To represent various sectors in decision-making, the crafting of the policy manual needs consultative meetings with the various committees involved in the festival’s operation. It would require a series of meetings with individuals or sectors involved. In the manual, performance targets in various areas, including environmental management, must be adequately defined.

The festival organization lacks the necessary human resource and expertise to conceptualize and develop green initiatives that would address the festival’s pressing environmental issues. This is coupled with limited financial resources in the investments for green initiatives. Financial resource allocation would allow the festival organization to hire experts and consultants to conceptualize and develop programs that would help curb the adverse environmental impacts of Sinulog. This agenda could also create a brand differentiation project, a positive public image, and increased competency, flexibility, motivation and efficiency in piloting green initiatives. The festival organization may invest in greener facilities and provide training to facilitate green practices better.

The following are some initiatives. First, the festival organization may invest in creating recycling stores where festival attendees can exchange their garbage for merchandise or souvenir items (Laing, Frost, 2010). This initiative could promote a circular economy by improving the eco-efficiency of products. Second, utilizing washable plates and cutlery or compostable cutlery (Laing, Frost, 2010) along with a styrofoam plastic-free policy during the festival (Laing, Frost, 2010) are among the alternatives. Third, the festival organization must discourage participants from purchasing bottled water (Graci, Dodds, 2008) by encouraging refillable tumblers through water refilling stations in strategic areas. Lastly, compost bins must be visible for proper waste disposal (Graci, Dodds, 2008).

The festival organization should coordinate with other government and non-governmental institutions and provide formal and systematic approaches to dealing with its partners in advancing the environmental management agenda. The organization must coordinate and partner with local environmental agencies to attain a green Sinulog festival during the festival celebration. In the formal partnership agreement, the festival organization must stipulate its needed services and specify each party’s roles. Consultation meetings must take place to ensure a mutually beneficial partnership agreement.

The festival organization’s partner selection process of sponsors provides little or no premium on environmental commitment. Since little regard is afforded to selecting a partner or sponsor, partners and sponsors have a weak commitment to addressing environmental issues. A partnership agreement with the festival organization and its partner sponsors must define their responsibilities and functions in attaining an environmentally-sound Sinulog festival. In executing the partnership agreement, the expected cooperative efforts of both parties would improve accountability and consistency in the delivery of services, particularly towards a greener festival. This initiative is beneficial to both parties, as the festival would serve as a platform for the brand awareness of the sponsor. Improving the environmental performance of the festival adds value to the brand image of both the sponsor and the festival organization.

The festival organization is observed to have a dynamic external environment (i.e., political, economic, technological, environmental and socio-cultural), which needs thorough consideration. On the other hand, it needs to sustain the current competitive position of the festival and further its growth to be at par with other festivals in Asia. The organization has commendable guidelines for protecting Sinulog’s cultural and spiritual values. It annually adopts the theme of the church and forges good coordination with the local government and private sectors. It also engages long-term relationships with sponsors who play a significant role in the festival’s success while encouraging local engagement, which is evident in the locals’ involvement in Sinulog operations. On the downside, with the lack of written commitment and partner accountability, various inconsistencies in its operations have been observed over the years. It lacks a general policy guideline regarding the sponsors’ commitment to advancing the environmental agenda. Performance evaluation is generally informal, with limited available hard data as evidence for future decision-making initiatives. Their understanding of green management is more focused on the waste generated during the grand parade and less on other festival events; thus, it is crucial to broaden their knowledge of the core principles of green management.

Nonetheless, the operational procedure of the festival organization, changes depending on the circumstances of a given period and on the feedback, suggestions or recommendations given during evaluation. For instance, the public services office offered recommendations to the festival organization during their evaluation on providing substantial cleaning time after the grand parade. The following year, the festival organization limited Sinulog night parties to give more time to clean up the streets. This lackmof integration and myopic view is brought about by the lack of vision-mission statement and overall environmental policy in addressing the relevant environmental issues. It offers limited efforts to develop concrete long-term plans to neither minimize waste nor control the behavior of the crowd regarding waste disposal during the festival. Adding to the dilemma is the limited financial investment of the organization in its environmental management efforts. With these findings, the festival organization should create an overall policy on planning, developing, implementing and controlling environmental management initiatives.

SWOT analysis and the RCA form the basis of the continuous improvement plan in environmental management. First, a partnership agreement between the festival organization and its partners and sponsors regarding the advancement of the environmental management agenda. While the coordination efforts of the festival organization and its good relationship with the public and private sectors would become leverage in working for green festival management. Such an agreement would have ripple effects on a more extended value chain as those partners would likely advance their environmental agenda onto their supply chains. The reputation of Sinulog as one of the best festivals in the Philippines and the adoption of a green festival would create a better public image for the festival organization and its partners. Second, the festival organization must develop an overarching policy manual that documents its governing principles and initiatives on green management and performance yardsticks. Third, the organization must develop a procedure manual that would help enhance employee cooperation and instill a sense of direction and urgency. Fourth, the organization can create profitable income-generating projects to sustain its additional operational costs and enable it to provide other financial resources in carrying out environmental management initiatives. Fifth, as the governing body, the organization can closely monitor the involvement of the different committees and develop a mechanism for gathering salient information as inputs to performance assessment. Finally, the various sectors of the community (e.g. academe, event experts) must be involved in planning, implementing and evaluating the festival organization’s efforts. Experts in event management and members of academe may be involved in the evaluation process to provide valuable inputs to the organization’s green festival agenda.

Festival tourism offers a platform for cultural sharing and provides a unique and memorable experience to tourists. On the other hand, the domain literature suggests that it augments economic development by effectively selling the destination, however, despite its obvious economic benefits, it is seen to be at the forefront of various environmental issues. Due to their spatial coverage, festivals are managed by governments or organizations that governments supervise. The seasonality makes it difficult for governments to organize formal entities which would be sanctioned to manage the entire operation, especially that associated with environmental issues. In addition, the dynamic external environments of festivals significantly intensify the complexity of several pressing issues. This study advances the literature on the greening of festivals by demonstrating a case study that is representative of most festivals in developing countries.

This work extends the insights of Yamagishi, Gantalao and Ocampo (2022), who assessed the green agenda of the festival organization using the PDCA cycle. Internal and external analyses were performed, and a SWOT analysis was demonstrated. Finally, the weaknesses in the SWOT analysis were considered as inputs to the RCA, which effectively identified the root causes of the organization’s lack of green management agenda. It was found that four crucial elements are necessary for greening the Sinulog festival:

These insights promote some managerial and policy implications in advancing the green agenda of the festival organization. Although these insights are often idiosyncratic, they can be crucial starting points of discussion on the greening of festival management.

Nevertheless, this work is not free from limitations as it primarily focuses on assessing the green agenda of a festival organization. Future work could develop a more systematic assessment platform in the evaluation process, perhaps using indicators and composite indices. Supplemental computational tools that would aid in the evaluation framework, such as using multiple criteria decision-making methods, may be an important direction in making the evaluation process more flexible and tractable for evaluating the green agenda of other festivals. Using such tools enables comparison across domain applications, which may become inputs for benchmarking initiatives and the sharing of best practices. This work derives its insights from conducting a structured interview with a key decision-maker, supported with direct observation and document reviews. A future evaluation may incorporate other relevant stakeholders so that various interests, including those that are conflicting, are addressed for the design of a more overarching greening strategy. Finally, a longitudinal evaluation is an interesting research agenda in order to examine the dynamics of greening festival management.

Uniwersytet Techniczny w Cebu, Wydział Zarządzania Turystyką, Centrum Matematyki Stosowanej i Badań Operacyjnych, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0775-6156, e-mail: kafferineyamagishi@gmail.com

Uniwersytet Techniczny w Cebu, Centrum Matematyki Stosowanej i Badań Operacyjnych, https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5050-7606, e-mail: lanndonocampo@gmail.com

ABSTRAKT

W artykule szerzej omówiono zagadnienia poruszone w poprzedniej pracy autorów, dotyczącej tzw. zielonego (proekologicznego) zarządzania wydarzeniami na przykładzie festiwalu Sinulog, odzwierciedlającego realia większości tego typu imprez organizowanych na Filipinach i w kilku innych krajach rozwijających się. Przeprowadzono analizę mocnych i słabych stron, szans i zagrożeń (SWOT), opierając się na wcześniejszym opracowaniu, w którym udostępniono spostrzeżenia na temat oceny inicjatyw zielonego zarządzania organizacją festiwali. Słabe strony poddane analizie SWOT zostały wykorzystane jako dane wejściowe w analizie przyczyn źródłowych (Root Cause Analysis – RCA) do zidentyfikowania głównych problemów zarządzania proekologicznego. Na podstawie wyników tych dwóch analiz można stwierdzić, że organizatorzy festiwali w ograniczonym zakresie uwzględniają program zielonego zarządzania. Ustalono cztery kluczowe elementy, które mogą przyczynić się do uekologicznienia festiwalu Sinulog: stworzenie polityki ochrony środowiska, przydzielenie zasobów finansowych i ludzkich dla wdrożenia proekologicznych inicjatyw, zawarcie umów partnerskich z lokalnymi instytucjami środowiskowymi oraz zawarcie umów partnerskich ze sponsorami, którzy aktywnie wspierają proekologiczną agendę. Elementy te mogą okazać się przydatne w tworzeniu zielonych programów dla innych festiwali.

SŁOWA KLUCZOWE

turystyka festiwalowa, zielone zarządzanie, analiza SWOT, analiza przyczyn źródłowych

Sposób cytowania (styl APA): Yamagishi, K., Ocampo, L. (2022). Evaluating the greening agenda of festivals: The case of Sinulog. Turyzm/Tourism, 32 (1), 115–140. https://doi.org/10.18778/0867-5856.32.1.06

INFORMACJE O ARTYKULE: Przyjęto: 12 sierpnia 2021 r.; Zaakceptowano: 17 maja 2022 r.; Opublikowano: 31 maja 2022 r.

Pomimo powszechnie znanych korzyści ekonomicznych płynących z turystyki coraz częściej zwraca się uwagę również na jej negatywne oddziaływanie na środowisko naturalne. Dla przykładu, w 2016 r. emisja szkodliwych substancji związana z transportem turystycznym stanowiła 5% światowej emisji węglowej, a według przewidywań Światowej Organizacji Turystyki Narodów Zjednoczonych (UNWTO, 2020) w 2030 r. udział ten ma wzrosnąć do 5,3%. Zrozumienie roli, jaką turystyka odgrywa w zmianach klimatycznych, oraz zwiększająca się świadomość społeczna i środowiskowa wzbudziły zainteresowanie rozwojem, który nie narusza ekologicznej równowagi (Laing, Frost, 2010; Mair, Jago, 2010). Negatywne skutki turystyki skłoniły branżę do włączania idei rozwoju zrównoważonego w swoją działalność, a sami turyści także stopniowo stają się coraz bardziej świadomi swojej odpowiedzialności za środowisko (Andereck, 2009). Jedną z kluczowych form turystyki mających istotne znaczenie w tzw. łańcuchu wartości (ang. value chain) jest turystyka wydarzeń. Władze uczyniły z niej narzędzie rozwoju generujące dochody i promujące poszczególne miejscowości wśród potencjalnych turystów (Getz, 2008; Yuan, 2013). Turystyka wydarzeń przynosi korzyści gospodarcze, masowo przyciągając turystów. W rezultacie sektor ten wywiera znaczący wpływ na środowisko i ludzi, zarówno pozytywny, jak i negatywny (Alampay, 2005; Buathong, Lai, 2017). W ramach zarządzania eventami pojawiają się troska o bioróżnorodność i dziedzictwo kulturowe oraz wątpliwości natury etycznej (Jones, 2001), zatem miejscowości turystyczne muszą się dostosować do nowego trendu oraz promować lokalną kulturę i lokalne tradycje, aby chronić dziedzictwo przed zniszczeniem (Stankova, Vassenska, 2015). Zwiększa się zainteresowanie wprowadzeniem polityki zrównoważonego rozwoju do zarządzania turystyką wydarzeń w celu ograniczenia jej negatywnych skutków. Na całym świecie odnotowano wzrost liczby wydarzeń, w których organizacji skutecznie rozwiązano problemy związane z zagrożeniem dla środowiska (Ahmad i in., 2013), czego przykładem może być Byron Bay International East Coast Blues and Roots Festival (Bluesfest) w Australii (Laing, Frost, 2010) lub festiwal Burning Man w USA (Kozinets, 2002; Sherry, Kozinets, 2007). Przemysł eventowy stoi obecnie przed wyzwaniem wzięcia na siebie większej odpowiedzialności za ograniczenie negatywnego wpływu, jaki wywiera na środowisko naturalne (Mokhtar, Deng, 2014). Jednakże organizacja imprez kulturalnych pozostawia wiele do życzenia, jeśli oceniać ich wkład w gospodarczy, społeczny i ekologiczny rozwój destynacji (Getz, 2017).

Turystyka festiwalowa zwróciła uwagę badaczy i praktyków w dziedzinie turystyki wydarzeń, co pod koniec lat 80. i na początku lat 90. zaowocowało publikacjami w literaturze turyzmu (Laing, 2018). Autorzy różnych opracowań dotyczących turystyki festiwalowej skupiali się na: jej skutkach ekonomicznych (Litvin, Pan, Smith, 2013; Nagy, Nagy, 2013; O’Sullivan, Jackson, 2002; Rao, 2001), rozwoju społeczno-gospodarczym (Doe i in., 2022), profilach uczestników (Prentice, Andersen, 2003; Song, Xing, Chathoth, 2015), działaniach i zarządzaniu (Frisby, Getz 1989; Frost, Laing, 2015), rozwoju zrównoważonym (Berridge, Moore, Ali-Knigh, 2018; Boggia i in., 2018; Liu i in., 2019; Zou i in., 2021), festiwalach kulinarnych (Kim, 2015), rozwoju turystyki festiwalowej (Ma, Lew, 2012) oraz na organizacji festiwali (Mariani, Giorgio, 2017; Ralston i in., 2007). Getz (2010) skompilował wszechstronny i ustrukturyzowany przegląd literatury na różne tematy związane z turystyką festiwalową, takie jak: autentyczność, znaczenia, dyskurs polityczny i społeczno-kulturowy oraz religia. Pomimo wskazywanych wcześniej w literaturze przede wszystkim negatywnych oddziaływań festiwali na środowisko (Ahmad i in., 2013; Cudny, 2013; O’Sullivan, Jackson, 2002) pojawiające się opracowania traktują te wydarzenia jako środek promocji ekologicznej agendy. Niektóre prace informowały o ich wpływie, planowaniu i motywacji do zielonego zarządzania (Liang, 2018). Mair i Laing (2012) zidentyfikowały czynniki motywujące i hamujące uekologicznianie festiwali i oceniły, w jaki sposób imprezy kulturalne mogą promować zachowania zrównoważone. Martinho i in. (2018) badali środki zapobiegania i zarządzania odpadami stałymi przez stosowanie monitoringu podczas festiwalu Andanças (Portugalia) w 2014 i 2015 r. Wong, Wan i Qi (2015) zwrócili uwagę na wpływ zaangażowania uczestników imprez przyjaznych dla środowiska na postrzeganie przez te osoby ekologicznych wartości, jak również na inne bezpośrednie i pośrednie skutki. Prace dotyczące proekologicznego zarządzania festiwalami podkreślają: strategie i najlepsze praktyki (Dodds, 2018), problemy społeczno-kulturalne (Small, Edwards, Sheridan, 2005), oddziaływanie na środowisko naturalne (Collins, Cooper, 2017), kwestię śmieci (Rafiee i in., 2018; Zelenika, Moreau, Zhao, 2018) oraz tzw. zielone intencje (Boo, Park, 2013).

Chociaż w literaturze zaistniał temat wpływu festiwali na otoczenie, to problem ich uekologicznienia nadal pozostaje niezgłębiony – zrównoważony rozwój w kontekście wydarzeń kulturalnych został poddany dość ograniczonej dyskusji, nawet w odniesieniu do zagrożeń dla środowiska, jakie te wydarzenia za sobą niosą (Arcodia, Cohen, Dickson, 2012). Negatywne skutki festiwali i turystyki festiwalowej stały się ważnymi tematami badawczymi (Getz, 2010). Włączenie do literatury przedmiotu studium przypadku uekologiczniania festiwali mogłoby częściowo wypełnić lukę na temat zarządzania tymi wydarzeniami, dostarczając wiedzy zarówno na jego temat, jak i w zakresie postępowania na podstawie różnorakich proekologicznych inicjatyw. Niniejszy artykuł uzupełnia tę lukę dzięki przeprowadzeniu dogłębnej analizy organizacji festiwalu pod kątem agendy proekologicznej. Autorzy prezentują przypadek festiwalu Sinulog w Cebu na Filipinach, podkreślając zachodzący tam proces przekształcenia imprezy na przyjazną środowisku. Sinulog to jeden z najpopularniejszych filipińskich festiwali, podczas którego lokalni mieszkańcy celebrują swoją kulturę i wiarę. Trwa on tygodniami i składa się z wielu poszczególnych imprez kulturalnych i religijnych, których punktem kulminacyjnym jest taneczna parada uliczna. Ponieważ wydarzenie przyciąga tłumy, a miliony ludzi gromadzą się na stosunkowo małym obszarze, organizatorzy festiwalu od lat borykają się z rosnącą liczbą problemów środowiskowych, zwłaszcza dotyczących zarządzania odpadami. Ostatnia impreza zaledwie w jeden dzień wygenerowała 219 ton śmieci zalegających wzdłuż trasy parady (Yamagishi, Gantalao, Ocampo, 2022). Rieder (2012) podkreślił, że Filipiny dostrzegły wagę adaptowania i wprowadzania różnych programów, inicjatyw i podejść, które są zarówno receptywne, jak i responsywne w stosunku do ochrony przyrody i konserwacji. Z tego powodu ocena agendy proekologicznego zarządzania festiwalem może nasuwać pomysły dotyczące przyszłego postępowania.

Zasadnicza wartość niniejszego artykułu polega na przeprowadzeniu dogłębnej analizy i oceny organizacji festiwali pod względem zielonego zarządzania oraz przedstawieniu możliwości uekologicznienia festiwalu Sinulog dzięki rozwinięciu pracy Yamagishi, Gantalao i Ocampo (2022). Przede wszystkim wyniki badań przeprowadzonych przez Yamagishi, Gantalao i Ocampo (2022), uzyskane z cyklu PDCA (z ang. Plan, Do, Check, Act, zw. też cyklem Deminga), tzn. główne zapisy Systemu Zarządzania Zrównoważonymi Eventami (Event Sustainability Management System lub ISO 20121), zostały wykorzystane jako dane wejściowe do analizy SWOT (ang. Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats – ‘mocne strony, słabe strony, szanse i zagrożenia’). Jako narzędzie zarządzania analiza SWOT identyfikuje te czynniki, aby wesprzeć planowanie celów i strategii przez organizatorów (Ommani, 2011), którym umożliwia lepsze rozumienie zasobów i możliwości (Namugenyi, Nimmagadda, Reiners, 2019), jak również podaje kontekst historyczny i możliwe rozwiązania istniejących lub zagrażających problemów (USDA, 2008). Jeśli chodzi o słabe strony w analizie SWOT, to najważniejsze problemy zielonego zarządzania ustalono na podstawie analizy przyczyn źródłowych (Root Cause Analysis – RCA). Jest to ustrukturyzowany i usystematyzowany proces identyfikujący przyczyny problemu (Sweis i in., 2018). Po ich ustaleniu proponowane są łagodzące środki zaradcze. Rozwiązania identyfikowane podczas RCA służą jako punkt wyjścia do dalszego uekologiczniania festiwalu. Przedyskutowano możliwe działania, by wesprzeć przyszłych badaczy w tej dziedzinie oraz dostarczyć organizatorom festiwali ważnych danych na temat zarządzania i postępowania. Informacje na temat zarządzania mogą służyć jako punkt odniesienia i wytyczne dla organizatorów festiwali przyjaznych dla środowiska naturalnego.

Artykuł skonstruowany jest w następujący sposób: kolejna – druga część to przegląd literatury dotyczącej tzw. zielonych (proekologicznych) imprez, w części trzeciej zaprezentowana jest metodologia, część czwarta przedstawia tło studium przypadku, w części piątej omówiono analizy SWOT i RCA, część szósta jest poświęcona pomysłom dotyczącym zarządzania i postępowania, artykuł kończy część siódma, która zawiera wnioski.

Wydarzenia to regularnie odbywające się działania, które oferują wyjątkowe doświadczenia, wynikające z wielu czynników (Getz, 2008). Getz i Page (2016) opisali cztery główne kategorie planowanego wydarzenia w ramach turystyki eventowej:

Pośród tych kategorii turystyka festiwalowa jest uważana za najszybciej rozwijający się typ turystyki, kładący nacisk na wymianę kulturalną w skali krajowej i międzynarodowej. Festiwale to wydarzenia społeczno-kulturalne przyciągające turystów, którzy generują skutki ekonomiczne (Frisby, Getz, 1989). Festiwale reprezentują kulturę, dziedzictwo, historię oraz komunikację międzykulturową danej społeczności, jednocześnie pobudzając świadomość ekologiczną i pogłębiając świadomość kulturową (Duran, Hamarat, 2014). Obecnie władze organizują festiwale, by zachęcić turystów do przyjazdu i napędzić rozwój gospodarczy oraz turystykę kulturalną (Raj, Vignali, 2010). Jednakże, pomimo swojej pozytywnej roli ekonomicznej i społeczno-kulturalnej, festiwale mają też skutki negatywne w postaci zanieczyszczenia środowiska naturalnego lub niewłaściwej prezentacji dziedzictwa kulturalnego, co z kolei prowadzi do konfliktów między lokalnymi mieszkańcami a turystami (Cudny, 2013). Na przykład festiwalom grozi utrata autentyczności, ponieważ ich przebieg jest dostosowywany do preferencji turystów. W rezultacie niektórzy turyści mogą czuć się oszukani, a lokalni artyści zniechęceni, co negatywnie wpływa na poziom imprezy (Gaworecki, 2007).

Organizatorzy festiwali zazwyczaj dysponują niewystarczającymi środkami (kapitałem finansowym, czasem, wiedzą). Wydarzenia te często organizowane są przez lokalne władze, które mają niewielkie umiejętności planowania i konstruowania strategii (Pugh, Wood, 2004; Wood, 2008; Wood, 2009). Getz i Frisby (1988) założyli, że organizatorzy festiwali działają tylko przez pewien okres w roku i są w dużym stopniu zależni od wolontariuszy oraz osób, którym może brakować wyszkolenia i doświadczenia związanego z obsługą festiwalu. Utrzymanie atrakcyjności i zdolności destynacji do organizacji wydarzeń jest uzależnione od jakości zasobów środowiska (Yuan, 2013). Jednakże festiwale są również często uważane za zagrożenie dla środowiska naturalnego, ponieważ przyciągają dużą liczbę uczestników do konkretnego miejsca w określonym czasie, przyczyniając się tym samym do nadmiernego wykorzystywania zasobów (Zifkos, 2015). Przemysł eventowy został zmuszony do wzięcia na siebie większej odpowiedzialności przy podejmowaniu decyzji kierowniczych i do wywoływania pozytywnego wpływu na środowisko (Mokhtar, Deng, 2014). W swojej pracy Yamagishi, Gantalao i Ocampo (2022) odkryli, że wielu organizatorom, przynajmniej w warunkach, w jakich funkcjonują, brak perspektywicznego podejścia do zielonego zarządzania, ponieważ agenda nie uwzględnia zasadniczych zagrożeń dla środowiska. Yuan (2013) zaprezentował trzy obszary odnoszące się do zrównoważonego zarządzania imprezami:

Przemysł eventowy został zobowiązany do większej odpowiedzialności za dbałość o środowisko naturalne (Mokhtar, Deng, 2014). W sektorze tym interesariusze są coraz bardziej skłonni adaptować proekologiczne inicjatywy, żeby zwiększyć konkurencyjność (Mankaa i in., 2018; Whitfield, Dioko, 2012). Organizatorzy tzw. zielonych imprez stosują proekologiczne środki i praktyki w zarządzaniu i wszelkich działaniach (Laing, Frost, 2010; Martinho i in., 2018; UNEP, 2009). Tölkes i Butzmann (2018) podkreślali główne cechy takich zielonych imprez, w tym festiwali:

Lokalne władze powszechnie wspierają i organizują proekologiczne wydarzenia i festiwale, aby pobudzać i promować zrównoważone zachowania pomiędzy uczestnikami i społecznościami lokalnymi (Mair, Laing, 2013; Tölkes, Butzmann, 2018). Takie festiwale charakteryzuje wyjątkowe zrównoważenie, widoczne przez pryzmat rozrywki, produktów i usług oraz estetyki (Tölkes, Butzmann, 2018). Organizatorzy tych wydarzeń przyjęli proekologiczny program, kładący nacisk na zminimalizowanie pośrednich negatywnych skutków imprez (przez ochronę zasobów) oraz unikanie strat i deterioracji środowiska naturalnego (Laing, Frost, 2010). Ta zielona agenda jest zazwyczaj opracowywana dzięki zaangażowaniu lokalnej społeczności oraz przedstawicieli odpowiednich sektorów w celu wdrożenia miejscowych strategii zrównoważonego rozwoju (Laing, Frost, 2010). Firmy festiwalowe i eventowe włączyły praktyki proekologiczne do swojej działalności, aby zredukować negatywny wpływ na środowisko przez właściwe zarządzanie odpadami, zmniejszenie zużycia wody i energii, wspieranie lokalnych dostawców i szerzenie świadomości proekologicznej wśród uczestników (Graci, Dodds, 2008; Mankaa i in., 2018). Organizacje popierające zielone festiwale oszczędzają zasoby, promując materiały nadające się do recyclingu i powtórnie wykorzystując zasoby, aby zminimalizować negatywny wpływ danego wydarzenia na środowisko. W odpowiedzi na aktualne trendy organizatorzy eventów dążą do zmniejszenia tych negatywnych skutków dla środowiska, ale nie mają wystarczającej wiedzy, od czego zacząć (Ahmad i in., 2013; Laing, Frost, 2010). Dość duża grupa organizatorów imprez chętnie wdrożyłaby praktyki zrównoważonego rozwoju, jednak część z nich nie jest tym zainteresowana ze względu na niechęć uczestników do ponoszenia większych opłat na pokrycie kosztów proekologicznych elementów oraz niewystarczające wsparcie sponsorów z powodu braku informacji i wiedzy na temat zrównoważonego rozwoju (Mokhtar, Deng, 2014). Wśród zagadnień ekologicznych dotyczących wydarzeń odpady są uważane za problem priorytetowy, zwłaszcza w odniesieniu do dużych imprez, w których udział bierze wielu uczestników (np. festiwale) (Laing, Frost, 2010).

Obecnie stosowane są trzy główne standardy, według których imprezy masowe uznawane są za zrównoważone: standard APEX (Convention Industry Council Accepted Practices Exchange) i ASTM International (American Society for Testing and Materials) – tj. certyfikowana międzynarodowa organizacja standardów rozwoju, powszechnie znana jako APEX/ASTM, standard GRI (Global Reporting Initiative) oraz ISO 20121.

Jako inicjatywa Events Industry Council APEX jest jednym z najbardziej rozbudowanych, dobrowolnych standardów promowania organizacji non profit w celu wprowadzenia praktyk, które podniosą wydajność w sektorze MICE. W porównaniu z ISO 20121 standard APEX/ASTM jest bardziej szczegółowy i zawiera kryteria dla osób zajmujących się planowaniem i dostawami. Są tu stosowane lista kontrolna (checklist) oraz skala punktacji, umożliwiające zmierzenie skuteczności działania w dziewięciu obszarach:

Zadaniem Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), pozarządowej organizacji o międzynarodowym zasięgu, współpracującej z United Nations Environment Program (UNEP), jest składanie raportów o przejrzystości i rzetelności stosowania zasad zrównoważonego rozwoju. GRI została utworzona w 1997 r. wraz z UNEP oraz Coalition for Environmental Organization (CEO) – amerykańską organizacją pozarządową w celu podniesienia jakości, wzmocnienia struktury i poszerzenia zasięgu raportów na temat zastosowania rozwoju zrównoważonego. Siła GRI leży w wytycznych dotyczących stosowanych standardów, obejmujących wymiar społeczny, przyrodniczy, ekonomiczny i instytucjonalny. Standardy te podzielone są na 8 wskaźników i 15 głównych wskaźników.

ISO 20121 – system zrównoważonego zarządzania eventami (Event Sustainability Management System) identyfikuje najważniejsze aspekty rozwoju zrównoważonego, łącznie z wyborem miejsc wydarzeń, procedurami, łańcuchem dostaw, logistyką i komunikacją (ISO). Podczas gdy standardy ISO 14001 – systemy zarządzania środowiskowego (Environmental Management Systems) mogą być wykorzystane w każdego rodzaju firmach, ISO 20121 zapewnia ramy, zasady i szczególne wymagania odnoszące się do sektora przemysłu eventowego. Wraz z powstaniem ISO 20121 przemysł ten przyjął międzynarodowe standardy zrównoważonego rozwoju imprez, sugerujące, że dostawcy i organizatorzy muszą wdrożyć zasady rozwoju zrównoważonego w swoje działania. Organizatorzy oraz zaangażowani interesariusze stają przed wyzwaniem ciągłego usprawniania i doskonalenia swojej działalności. Organizatorzy są również wspierani w zakresie kreatywności i elastyczności działań związanych z zarządzaniem imprezą kulturalną, zmierzającym w kierunku rozwoju zrównoważonego, aby nie musieli rezygnować z osiągnięcia celów wydarzenia.

W badaniu wykorzystano metodę studium przypadku, by lepiej zrozumieć obserwowane zjawisko (festiwal). Yin (2009) opisuje to podejście jako badanie empiryczne, w którym bieżące zjawiska posiadają dogłębny i realistyczny kontekst, a granice między zjawiskiem i jego kontekstem nie są wyraźne. W niniejszym artykule wybrano przypadek Sinulog w celu zbadania, w jakim stopniu praktyki proekologiczne zaczęły być stosowane na festiwalach. Przeprowadzono szczegółowy wywiad złożony z pytań otwartych, aby uzyskać dane i informacje (Guion, Diehl, McDonald, 2011), pozwalające badaczom poszerzyć wiedzę na podstawie interpretacji dokonanej przez uczestników badania oraz zrozumieć jego zasadnicze aspekty (Miles, Huberman, 1994). W wywiadach pogłębionych wyróżnia się siedem etapów: tematyzację, projektowanie, przeprowadzenie wywiadu, transkrypcję, analizę, weryfikację i raportowanie (Kvale, 1996). Tematyzacja polega na ustaleniu celu wywiadu. Projektowanie jest strategią uzyskiwania potrzebnych informacji w przebiegu wywiadu przy pomocy przewodnika. Prowadzenie wywiadu oznacza ustrukturyzowaną dyskusję z respondentem/respondentami. Transkrypcja to spisanie tekstu każdego wywiadu z nagrania audio. Analiza ocenia transkrypcje z wywiadów i dzieli je tematycznie. Weryfikacja wykorzystuje metodę triangulacji, aby zbadać wiarygodność zebranych danych. Raportowanie polega na prezentowaniu wyników – łącznie z analizą wkładu i wpływu tych wyników na problem badawczy. W niniejszym opracowaniu dane zebrane podczas wywiadów zostały uzupełnione obserwacją bezpośrednią i dokumentacją. Obserwacja bezpośrednia pozwala na zebranie danych ewaluacyjnych – osoby badane są obserwowane w ich naturalnym, niezmienianym środowisku. Metoda ta jest stosowana, gdy badanie ma na celu ocenę trwającego procesu behawioralnego, wydarzenia lub sytuacji (Holmes, 2013). Wreszcie przeprowadzono systematyczną ocenę dokumentacji wspierającej, aby przeanalizować dane i je zinterpretować, co ma służyć ustaleniu znaczeń, zrozumieniu zagadnienia i zdobyciu wiedzy empirycznej (Bowen, 2009; Corbin, Strauss, 2008) – jest to również narzędzie triangulacji (Denzin, 1970).

Yamagashi, Gantalao i Ocampo (2022) zidentyfikowali dyrektora wykonawczego festiwalu jako kluczową osobę informującą, odgrywającą główną rolę w osiągnięciu celu badań. Dyrektor wykonawczy ma rozległą wiedzę na temat administrowania festiwalem Sinulog ze względu na swoje duże doświadczenie i wiedzę techniczną. Jest on pełnoetatowym pracownikiem firmy, z wiedzą z pierwszej ręki o wszelkich działaniach, który dostarcza informacji na temat wprowadzania proekologicznych elementów do organizacji festiwalu.

Dane wykorzystane w tej pracy zostały zebrane przede wszystkim za pomocą wywiadu ustrukturyzowanego z kluczowym informatorem, skonstruowanego na podstawie badań Yamagishi, Gantalao i Ocampo (2022), którzy zmierzyli zgodność organizacji festiwalu z zasadami zielonego zarządzania, wykorzystując cykl Deminga. Wywiad został nagrany za zgodą respondenta oraz zawierał pytania otwarte i projekcyjne, pozwalające wyrazić mu swoją opinię zgodnie z instrukcją do wywiadu ustrukturyzowanego. Wywiad taki obejmuje wszystkie istotne szczegóły zastosowania zarządzania proekologicznego przez firmę oraz umożliwia otwartą komunikację i udostępnienie potrzebnych danych. UCLA Center for Health Policy Research oraz wywiady z kluczowymi informatorami wskazały sposób implementacji zasad proekologicznych oraz poszerzyły wykorzystanie danych dostarczonych przez Yamagishi, Gantalao i Ocampo (2022) do dalszych badań nad strategicznymi sposobami uekologicznienia festiwalu Sinulog.

Tekst wywiadu nagranego z kluczowym informatorem został spisany. Następnie przeprowadzono analizę tematyczną transkrybowanych danych – systematyczną procedurę ich identyfikowania, analizowania oraz ustalania wątków tematycznych. Dane zostały również uporządkowane i szczegółowo opisane (Braun, Clarke, 2006). W badaniu wykorzystano metodę Brauna i Clarke’a (2006), którzy opracowali jasne wytyczne dotyczące przeprowadzenia analizy tematycznej w sześciu etapach:

Wątki tematyczne odnoszą się do celów badania i są definiowane w sposób teoretyczny lub dedukcyjny. Wyniki zweryfikowano przez zakotwiczenie i ponowne przeczytanie artykułu. Zostały one zaprezentowane w różnych wątkach tematycznych razem z celami badań.

Analiza SWOT koncentruje się wokół aktorów środowiska naturalnego, co stanowi najważniejszy element planowania biznesowego i strategicznego (Ghazinoory, Abdi, Azadegan-Mehr, 2011; Phadermrod, Crowder, Wills, 2019). SWOT jest narzędziem analizy praktycznej, wykorzystywanym w różnych kontekstach, takich jak: budowanie strategii (Rauch i in., 2015; Wang, Hong, 2011), turystyka medyczna (Ajmera, 2017; Moghavvemi, Mohezar, Zailani, 2017), sportowa (Roslan, Ramli, Choy, 2018), festiwalowa (Carlsen, Andersson, 2011), czy zrównoważona (Navarro-Martínez i in., 2020). Należy zauważyć, że lista ta nie jest wyczerpująca. Słabe strony zidentyfikowane w ramach analizy SWOT stanowią punkt wyjścia do analizy RCA, której celem jest zbadanie i sklasyfikowanie pierwotnych przyczyn negatywnego wpływu na dane zjawisko (Tomić, Spasojević Brkić, 2011). Zrozumienie przyczyn źródłowych jest podstawą zapobiegania ponownemu pojawianiu się problemów określonych jako słabe strony. Analiza RCA przebiega w czterech etapach. Najpierw są zbierane dane, aby pozyskać jak największą wiedzę na temat rozważanego problemu, oraz identyfikuje się czynniki towarzyszące i potencjalne przyczyny pierwotne. Oczekuje się, że ten etap wymaga więcej czasu. Następnie czynniki przyczynowe są porządkowane i analizowane według uzyskanych informacji. Na tym etapie potencjalne luki i braki w wiedzy są traktowane jako postępy w badaniu. Po określeniu czynników przyczynowych i identyfikacji przyczyn źródłowych jest konstruowany schemat decyzyjny w celu zidentyfikowania powodu źródłowego dla każdego czynnika przyczynowego. Diagram obrazuje schemat rozumowania przez odpowiedź na pytanie, skąd wzięły się czynniki przyczynowe. Ostatnim, czwartym etapem jest utworzenie listy rekomendacji sugerujących potencjalne środki zaradcze zapobiegające ponownemu pojawieniu się problemu w przyszłości (Tomić, Spasojević Brkić, 2011). W niniejszej pracy RCA została wykorzystana do identyfikacji głównych problemów proekologicznego zarządzania. Po ustaleniu przyczyn źródłowych można opracować środki zapobiegające, aby zwiększyć skuteczność tego typu zarządzania.

W krajach rozwijających się turystyka generuje dodatkowy dochód z wymiany walut, tworzy nowe miejsca pracy, powiązania oraz stymuluje różnorodność gospodarczą (Sahli, Nowak, 2007). Filipiński przemysł turystyczny jest postrzegany jako jeden z elementów napędzających wzrost gospodarczy kraju (NEDA, 2017), w 2019 r. odnotowano ok. 8,26 miliona przyjazdów turystycznych (DOT, 2020), które przyniosły ok. 51 miliardów USD, przewyższając sumę z 2018 r. – 45,6 miliarda USD (PSA, 2020). Pokazuje to, że 12,2% dochodów gospodarki jest mierzone bezpośrednią wartością dodaną brutto, płynącą z turystyki (DOT, 2020). Wydatki państwa na turystykę przyjazdową wzrosły o 43,9% w 2017 r., a na turystykę krajową – o 25,5%. Zatrudnienie w sektorze turystycznym wzrosło o 1,8% w 2018 r. (PSA, 2020) i było wtedy oceniane na 5,4 miliona osób (PSA, 2019).

Festiwal Sinulog to jeden z najważniejszych festiwali na Filipinach, organizowany jest na cześć Dzieciątka Jezus i odbywa się w każdą trzecią niedzielę stycznia. Duma lokalnych mieszkańców jest demonstrowana przez taniec, kreatywne platformy kwiatowe oraz pokazy lalkarzy. Każdego roku miliony turystów z całego świata przyjeżdżają, żeby zobaczyć wielką paradę podczas festiwalu. Dzięki swej strategicznej lokalizacji, naturalnym cechom terenu i infrastrukturze prowincja Cebu, a zwłaszcza samo miasto Cebu, gdzie odbywają się główne obchody Sinulog, ma zdolność przyciągania turystów zagranicznych i krajowych (Abocejo, 2015). Według raportu GMR Megawide Cebu Airport Corporation w 2019 r. (dane sprzed pandemii) przyjazdy turystyczne na festiwal Sinulog w Cebu osiągnęły liczbę 292 812 osób, w tym 157 920 stanowili turyści krajowi, a 134 892 – zagraniczni (Saavedra, 2020). Przewidywano, że w 2020 r. liczba przyjazdów sięgnie 336 000 osób, w tym 174 000 będą stanowili turyści krajowi, a 162 000 – zagraniczni (Saavedra, 2020). W 1980 r. odbyła się pierwsza procesja Sinulog. Uniwersytety i inne szkoły wyższe zostały poproszone o ocenienie i ulepszenie ruchów tanecznych słynnych sprzedawców świec z Bazyliki Mniejszej Dzieciątka Jezus (Basilica Minore del Sto. Niño de Cebu) (Yamagishi, Gantalao, Ocampo, 2022). Projekt został później oddany pod nadzór Komitetu Historycznego Miasta Cebu w celu skonceptualizowania i zorganizowania tradycyjnego festiwalu Sinulog. W 1981 r. w organizację festiwalu zaangażowanych było kilka kluczowych branż.

Organizatorzy festiwalu ustanowili dodatkowe kategorie konkursowe, które otworzyły nowe rynki bez narażania na ryzyko naruszenia istoty tego wydarzenia. Festiwal Sinulog może być obecnie oceniany w Internecie, przez jego oficjalną stronę. Wielka parada jest najbardziej oczekiwaną imprezą uliczną, której częścią są ostatki (ostatni dzień karnawału) i występy lalkarzy prezentujących swoją kreatywność, by uhonorować Święte Dzieciątko Jezus. Inne elementy to . wystawy i konkursy fotograficzne, filmy krótkometrażowe i konkurs piosenkarski Sinulog Idol. Festiwal organizowany jest przez dwa różne podmioty: wydarzenia kulturalne – przez organizatorów, a część religijna – przez Kościół. Oba podmioty pracują efektywnie dzięki wysiłkom lokalnych władz, które są bezpośrednio zaangażowane w organizację i zarządzanie, oraz komisji, grup roboczych i ochotników zapewniających usługi w trakcie festiwalu (rysunek 1). Organizatorzy festiwalu zdobyli już dobrą reputację i nawiązali dobre stosunki z różnymi sponsorami (krajowymi i zagranicznymi). Nazwa „Sinulog” i logo to podstawowe atrybuty festiwalu, zarejestrowane w Biurze Własności Intelektualnej Filipin. Jest on z powodzeniem organizowany od prawie 40 lat i stanowi jeden z najważniejszych i najpopularniejszych festiwali na Filipinach.

Sinulog zyskał międzynarodową sławę w 2018 r. Wtedy też lokalne władze rozważyły przeznaczenie środków na lepsze zarządzanie tą imprezą, jako że z każdym rokiem przyciąga ona coraz więcej turystów, zarówno krajowych, jak i międzynarodowych. Temu rozwojowi towarzyszą konkretne problemy, takie jak zwiększony ruch uliczny, trudności z kontrolą tłumu, przestępczość i śmieci (Yamagishi, Gantalao, Ocampo, 2022). Jeśli chodzi o odpady stałe, generowane przy okazji festiwalu, lokalne władze powzięły pewne kroki zaradcze. Według Wydziału Usług Publicznych w Cebu w 2020 r. zebrano tylko 131 ton śmieci, czyli o 79 ton mniej niż w 2019 r. (Erram, 2020). W 2018 r. Sinulog wygenerował 219 ton śmieci na trasie parady i w okolicy. Uprzątnięcie ich wymagało zaangażowania 586 osób (Bongcac, 2018). Podczas festiwalu Sinulog 2017 miasto wyprodukowało 155 ton śmieci – o 110 ton więcej niż w 2016 r. Były to głównie plastikowe butelki (Fernandez, 2017). Katalog odpadów pozostałych po festiwalu zawiera przede wszystkim plastikowe torby, jednorazowe pojemniki na wodę, opakowania po żywności i skórki od owoców. Ilość śmieci zebranych podczas festiwalu w 2015 r. wyniosła 197 ton, a w 2014 r. – 174 tony. Liczba ta również przewyższyła sumę 187 ton w 2013 r. i 100 ton w 2012 r. (Domecillo, Florita, 2015). Na podstawie trendu (rysunek 2) widać, że zarządzanie odpadami stanowi poważny problem przy proekologicznym podejściu do festiwalu Sinulog.

Festiwal Sinulog przynosi korzyści lokalnej gospodarce, przyciągając miliony gości każdego roku, przynosząc dochody hotelom i innym podmiotom związanym z turystyką. Dzięki licznym formom rywalizacji wszelkiego rodzaju, takim jak konkurs talentów, pokazy czy festiwal filmowy, organizatorzy Sinulog mają nadzieję przyciągnąć młodsze pokolenia, by odtworzyć autentyczność i charakter festiwalu. Według wywiadu ustrukturyzowanego organizatorzy nie przedstawiają żadnego ustalonego stanowiska co do swojej wizji i misji, które jasno określiłyby cel podejmowanych decyzji i dałyby personelowi poczucie tożsamości. Brak szczegółowych wytycznych organizacyjnych niesie za sobą szereg implikacji w sferze planowania, wdrażania i monitorowania zielonego zarządzania festiwalem. Brak formalnej polityki, która regulowałaby wszystkie działania organizacyjne pod kątem uekologicznienia imprezy, jest jednym z ważnych długofalowych skutków braku wytycznych. Przy rosnących problemach festiwalu Sinulog (np. nadmierna eksploatacja zasobów, zużycie energii i produkcja śmieci), brak takiej polityki świadczy o braku mierników efektywności działań sprzyjających środowisku. Słabe działania tego typu ze strony organizatorów można scharakteryzować jako krótkowzroczną agendę zarządzania odpadami z perspektywy całościowego zarządzania proekologicznego. Instrukcje zamieszczone na stronie organizatorów są niewystarczające, by poczynili oni znaczące wysiłki w kierunku ograniczenia negatywnego wpływu festiwalu na środowisko przyrodnicze. Obecne działania w dużym stopniu zależą od wydziału środowiska w lokalnym samorządzie, który może nie mieć bezpośredniej kontroli nad inicjatywami w organizacji całego festiwalu.

Tabela 1. Analiza SWOT organizacji festiwalu

| Mocne strony | Słabe strony |

|---|---|

|

|

| Szanse | Zagrożenia |

|

|

Źródło: opracowanie autorów.

Brak całościowego planu powstrzymania negatywnych skutków zbierania się ogromnych tłumów złożonych z dziesiątków milionów ludzi pozostaje poważną luką, do której trzeba się odnieść w ramach polityki proekologicznej. Program Sinulog Garbage Watch stanowił dobry początek, jednakże jego skuteczność jest trudno ocenić, odkąd w 2018 r. zebrano 219 ton śmieci (o 155 ton więcej niż w 2017 r.). Z kolei środki przyznane zielonym inicjatywom są niewielkie, co trzeba uwzględnić na etapie planowania. Uekologicznienie festiwalu musi być wprowadzane we współpracy z partnerami ekologicznie świadomymi. Ponieważ organizatorzy są dotowani przez różnych partnerów, wybór sponsorów lub kontrahentów musi być kontekstualizowany w ramach ich zobowiązań odnośnie do podtrzymywania wysiłków na rzecz środowiska. Większy nacisk na wybór odpowiedniego, świadomego partnera musi również korespondować z działaniami proekologicznymi podczas festiwalu, zgodnie ze zużyciem materiałów, energii i produkcją odpadów. Idąc tym tropem, należy zinstytucjonalizować różne wskaźniki do pomiaru działań proekologicznych. Na podstawie wyników cyklu Deminga, podanych przez Yamagishi, Gantalao i Ocampo (2022), w tabeli 1 zaprezentowano analizę SWOT.

Analiza RCA została przeprowadzona w celu określenia przyczyn niezgodności z założeniami lub słabych stron organizacji festiwalu Sinulog. Rysunki 3–6 pokazują wyniki analiz RCA dla wszystkich słabych stron. Przyszłe inicjatywy związane z ulepszaniem procesu zarządzania festiwalem na stałe mogłyby złagodzić lub nawet wyeliminować te słabe strony. Przyczyny pierwotne służyłyby jako wkład w plan ciągłego ulepszania.

Sformułowano opis możliwych środków zaradczych wobec słabości organizacji festiwalu pod kątem zielonego zarządzania (należy zauważyć, że wynikają one z analiz SWOT i RCA).