Precious Evanescence: The “Little Angels” by Chichico Alkmim through the Lens of Vladimir Jankélévitch

Universidade Federal do ABC, Santo André

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8176-5990

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8176-5990

Abstract

This article establishes a dialogue between two distinct domains: the portraits of deceased infants—known in Brazil as anjinhos (“little angels”)—captured by the Brazilian photographer Chichico Alkmim (1886–1978) in the first decades of the 20th century in the region of Diamantina (Minas Gerais), and the thought of the French philosopher Vladimir Jankélévitch (1903–85), who deeply reflected on themes such as death, memory, transience, irreversibility, and innocence. The article is divided into two main sections, each with two subsections. The first section begins by contextualizing the conception of the anjinho in the popular and religious collective imagination of Minas Gerais, from colonial times to the early 20th century (1.1). It then introduces Chichico Alkmim’s biography and his particular approach to the anjinhos portraits (1.2). The second section shifts the focus to the project’s central aim, connecting cultural and historical implications, as well as artistic traits of this poignant photographic production to certain aspects of Jankélévitch’s work. Initially, this connection is explored through a negative approach (2.1), highlighting how the religious beliefs surrounding the anjinhos, the association between childhood and death, and postmortem photography contrast with Jankélévitch’s values and sensibility. The final subsection (2.2), however, delves into a point that might draw the philosopher closer to Chichico’s anjinhos portraits: the commitment (endowed with ontological and ethical implications) of attesting to a completed existence.

Keywords: memory, death, “little angel,” photography, funeral.

During a visit to the exhibition Chichico Alkmim, Fotógrafo, held in the Palácio das Artes (Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil) in 2019, I realized that Chichico’s portraits of dead children, the so-called “little angels” (anjinhos), could be profoundly interpreted through the thought of Vladimir Jankélévitch. Especially recognized for his works on moral philosophy and musical aesthetics, Jankélévitch constructed—outside the dominant philosophical schools and trends of the second half of the 20th century—“a kind of private constellation” (Berlowitz qtd. in Jankélévitch and Berlowitz 238). Within this “constellation,” themes such as death, transience, memory, nostalgia, innocence, enchantment, irreversibility, and irrevocability are intertwined and illuminated in their multiple ontological, anthropological, ethical, and aesthetic implications, offering a privileged theoretical framework for reflecting on that photographic production.

Upon discovering what Chichico’s “little angels” refer to, some readers might quickly choose to skip this text, since the theme of death, in itself, is one that our contemporary Western worldview often prefers to avoid or reject.[1] This rejection may be even greater when it comes to the death of a child, which appears to be particularly incomprehensible and absurd. We would rather forget that death could arrive “too early to cruelly cut short the life of those who were just born and who would have all the right to live it” (Recalcati 23).[2] Besides reminding us of this possibility—one that, fortunately, is diminished today in privileged countries that are spared from war, famine, and epidemics, and benefit from advanced medicine—the portraits of dead infants may now easily be seen as reflecting a taste for the macabre.

Nevertheless, Chichico’s “little angels” could evoke reactions, feelings, and thoughts beyond mere morbid curiosity—a potential danger for both the author and the reader when engaging with such a theme. When one closely considers the context of the portraits, one realizes that they do not only expose infants’ corpses but also address care, affection, and devotion. These forms of relationship may offer a different “tonality” to an approach to death, from which beauty, delicacy, and poetry are not completely excluded (although, as will be shown, this is not the predominant Jankélévitchian approach to death). Furthermore, the examined photographs raise political and social questions that remain relevant to our time (particularly in relation to postcolonial studies), an aspect that can be emphasized through the lens of Jankélévitch’s thought.

This analysis will be divided into two parts. First, it will be necessary to contextualize the traditional concept of the “little angels” (especially as understood in Brazilian culture) and its depiction in Chichico’s work. Secondly, the proposed dialogue between these portraits and Jankélévitchian philosophy will be explored: initially, via the differences in their conceptions, and then via a significant point of intersection, namely, the importance and the commitment—imbued with ontological and ethical implications—of attesting to a completed existence.

THE “LITTLE ANGELS” AND CHICHICO’S WORK: A CONTEXTUALIZATION

A POPULAR EXPRESSION IN A RELIGIOUS WORLDVIEW

Largely deployed in the Iberian Peninsula, in Italy, and in Latin America from the 18th century to the first half of the 20th, the denomination “little angels” (anjinhos in Portuguese, angelitos in Spanish and angioletti in Italian) used to refer to baptized, dead infants. These were generally newborns up to 7-year-old children, who were considered to be deprived of the “use of reason”[3] and consequently of the possibility of committing sin. That immaculate condition enabled their souls to ascend directly to Heaven, where they would intercede on behalf of their earthly family (in particular facilitating their mother’s future entrance to Heaven).

As Duarte notes in her doctoral dissertation, this conception combined popular and orthodox religious beliefs. On the one hand, Catholic theology could not endorse the identification between a human child and an angel. According to the explanation of the Brazilian Benedictine monk Estêvão Bettencourt, dead infants, even when baptized, “do not become angels or little angels, as people sometimes say. They can only be considered little angels to the extent that they reproduce the innocence of angels. Between the nature of the human spirit and the nature of the angel there is no possible transition” (qtd. in Duarte 143–44, emphasis mine).[4] On the other hand, religious ideas such as purity restored to children through baptism and preserved until the acquisition of the “use of reason,” the intercessory power of the elect souls, and the Communion of Saints, which allowed “exchanges between the earthly and the celestial worlds” (73), were affirmed by the decrees of the Council of Trent (1545–63). Additionally, the title of anjinhos also appeared in some death registers in parishes both in Portugal and in Minas Gerais, indicating that the official Church may have, in some cases, incorporated the colloquial expression (151–54).

It is important to note that, contrary to our contemporary perspective, the feeling which accompanied the loss of a baptized dead infant in Latin America and in Catholic European countries was not necessarily a melancholic or grievous one. On the contrary, the family and the surrounding community would have enough motives to rejoice, believing that their beloved innocents, besides becoming strong intercessors, were promptly received in Paradise and spared from the hardships of earthly existence (Delumeau 489).

As a matter of fact, an official post-Tridentine document of the Catholic Church, namely the Rituale Romanum enacted by Pope Paul V in 1614, prescribed that the funerals of baptized infants deserved a festive celebration, in contrast to the somber funerals of adults.[5] This prescription—which encouraged an optimistic posture from the child’s parents, godparents, and other relatives—appears to have been followed literally and even intensified in Brazil, where it persisted in some locations until the first half of the 20th century.[6] For instance, during a journey to the city of Rio de Janeiro in the early 19th century, the English traveler Luccock expressed his surprise at the cheerful attitude of a mother attending the funeral of the last of her surviving children (80). Later, the renowned Brazilian folklorist Câmara Cascudo records that, in the state of Ceará (Northeast Brazil), probably at the beginning of the 20th century, the funeral processions of the “little angels” were often accompanied by celebratory displays including pistol shots, prayers, and poetry (qtd. in Duarte 75). And, according to the childhood recollections of the writer Iara Ramos Tribuzzi, in her hometown of Salinas (North of Minas Gerais) in the 1940s, cheerful ringing of bells announced the funerals of the anjinhos, whose bodies were placed over a wooden support, covered with a cloth and adorned with a profusion of colored flowers, some of which were made out of crepe paper by the mother of the deceased. Nevertheless, due to an increasing process of secularization that, from the end of the 19th century onward, affected to varying degrees the different regions of Brazil (and of the world), Brazilian families tended to adopt more circumspect attitudes towards the loss of their infants (72).

In addition to secularization, the changes in the human relationship with death that occurred in Brazil (as well as in the Western world) during the 19th and early 20th centuries were also driven by unprecedented advances in hygiene standards and technology. On one hand, the improvement of sanitary conditions—brought about, for example, by the development and application of certain vaccines—may have “made the loss of one’s own child less common and, therefore, more tragic” (Storia e Memoria). On the other hand, the memory of the departed loved ones was progressively liberated from religious symbols and constraints, as the burial place moved away from the territory of a parish. Therefore, private expressions of grief and affection arose in innovative forms and media, such as photography and newspaper obituaries, which considerably extended postmortem tributes beyond the restricted memorials of national heroes, artists, and saints.[7]

CHICHICO’S BIOGRAPHY AND AN OVERVIEW OF HIS “ANJINHOS”

It was precisely at this historical period that Francisco Augusto Alkmim, known by his nickname Chichico, was born in Bocaiúva, a small town in the North of the Brazilian state of Minas Gerais. Around 1913, after moving to the colonial city of Diamantina (also in Minas Gerais), Chichico devoted himself entirely to photography, working occasionally as an itinerant photographer but more consistently as a studio-based one. His studio, installed at his own residence, was fully equipped by the mid-1920s and likely remained active until the mid-1950s (Silva Santos 45). Notably, “unlike many other studio photographers working in the countryside of Brazil at that time, Chichico never limited himself to portraying Diamantina’s bourgeoisie. Laborers connected to small-scale mining, commerce, and industry also frequented his studio” (Instituto Moreira Salles). It is widely acknowledged in Diamantina that, in some cases, those underprivileged clients, most of them descendants of the enslaved, had the opportunity to be photographed—and photographed with dignity[8]—thanks to Chichico’s generous heart, capable of accepting unusual payments for his services, such as “a cabinet and a pounder” (Alkmim 103), and of providing clothing and footwear whenever necessary.

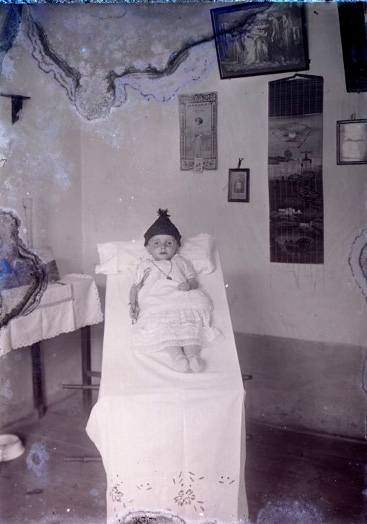

Among the more than 5,000 glass negatives that compose the photographer’s collection,[9] which include images of “weddings, baptisms, funerals, popular and religious feasts, landscapes, and street scenes” (Instituto Moreira Salles), we find 53 postmortem items, of which 46 are photographs of the anjinhos. As occurred with the portraits of deceased adults, those of the dead infants, probably dated between 1913 and 1930, were taken both indoors and outdoors, and, in some cases, in the small villages where the grieving families lived. Irradiating an eerie, yet at the same time, graceful atmosphere, the photographs of the anjinhos are full of religious references and allusions, substantiating a recent statement by the Italian maestro Riccardo Muti (one that is especially valid from a religious standpoint): “[W]hen we speak of death, we speak of sacrality” (Muti and Torno 57–58).

We may mention, as examples of those elements, the white dresses and flowers that, covering and surrounding the infant’s corpse, allude to his or her immaculate and elect soul; the luminosity that, irradiating from that corpse, suggests a divine or supernatural presence; the inclusion of religious images, such as the Sacred Heart of Mary, watching over the deceased infant; the participation in the scene of living children dressed as angels, simulating the reception of the infant in the celestial sphere; and the inclined position of the baby’s torso or of the coffin creating an illusion of an angel’s ascension.

As Virginia de la Cruz Lichet explains in “Image de la Mort et la Mort en Images,” some of the features seen in these portraits were common tropes of this photographic genre at the time. This confirms that secularization in certain parts of the globe was not as radical or accelerated as we might have assumed, influenced by the Nietzschean diagnosis of the “death of God” in modernity.[10] Certainly, Diamantina, a small episcopal city[11] somewhat isolated due to its geographical position, its altitude (about 1,300m above sea level), and its topography, could be listed among those locations. Therefore, Chichico’s “little angels” (as well as other portraits of the genre in that period) would not only combine the new, socially recommended attitude of restraint toward the dead with previous religious beliefs, but would also, at unexpected moments, capture the lingering “familiarity with the child’s death and even relaxed attitudes” (Duarte 79).

A POSSIBLE DIALOGUE WITH JANKÉLÉVITCHIAN THOUGHT

SOME POINTS OF DIVERGENCE

Proceeding to the philosophical foundation of this investigation, we should firstly emphasize that Jankélévitch’s thought is originally woven with two threads of contrasting textures. On the one hand, the agnostic thinker of Jewish descent demonstrates a delicate sensitivity to the manifestations of positive mysteries, such as music, poetry, love, and forgiveness, trying to “touch” those ineffable realities through a language that, at times, flirts with poetry, Neoplatonism, and Christian mysticism. On the other hand, he adopts a very direct and even harsh approach when he focuses on war crimes and death, the object of study of his impressive work La Mort, published in 1966. Contrary to the nature of the ineffable, whose extreme fecundity inspires inexhaustible verbal and artistic formulations, death is the register of the unspeakable (indicible) par excellence: situated outside of our “possible experience” and identified with radical non-being, there is no content in it to be expressed, there is no continuity between it and life that allows a description or a preparation for it.

Therefore, the conception of the anjinhos, which human imagination furnishes with an unreachable and void state, would probably sound to Jankélévitch like an attempt to “elude the obstacle of unspeakability (indicibilité)” (Jankélévitch, Mort 54). It could be, according to the philosopher’s specification, a euphemism to cope with death,[12] which, as observed in this essay’s introduction, becomes even more shocking when it claims a child. While the Greeks used to invoke “in the place of the furious Erinyes, the benevolent Eumenides of death” (ibid.), from the 18th to the first decades of the 20th century, Brazilian Christians would have replaced the “scabrous monosyllable” (ibid.)—mort (death), which in Portuguese is actually a disyllable (morte)—with a peaceful image: the anjinho. This sort of euphemism sounds to the philosopher like “a fiction from which bad faith is never entirely absent” (56). Curiously, this moral hypothesis is implied in a passage of the renowned book Casa-Grande & Senzala, where the Brazilian sociologist Gilberto Freyre states that the expression at hand derived from a strategy conceived by Jesuit priests in the colonial period who, “perhaps to mitigate among the indigenous people the harmful effect of the increased infant mortality that followed the contact or the intercourse under dysgenic conditions between the two races, did everything to adorn or to beautify the infant’s death” (203). Although this hypothesis is quite doubtful,[13] we cannot deny that the conception of the “little angels” was directly connected to practices and ideas, such as baptism, sin, salvation, and expiation, through which the Catholic Church strongly manipulated the faithful, notably those who belonged to other religious matrices, stimulating fear and fantasies.

A component of fantasy certainly takes part in the conception of the “little angel,” contributing to the elusion of the emptiness of death. According to Jankélévitch, the “beyond” should be really beyond everything in immanent experience, including any idea of the future, a term that integrates the time-honored expression “future life.” For an imaginative individual or collective mind that, as already mentioned, surpasses the limits of “possible experience,” Paradise is “a sublimated here below, as Hell is a monstrously grimacing and deformed here below” (Jankélévitch, Mort 344). Moreover, the conception of the “little angels” supposes a “mercenary hope of Paradise” (ibid.), especially from the mother who expects to be favored, both in the present and in the “afterlife,” by the aforementioned intercession of her lost child. Even if such a belief, in this circumstance, functioned as the only possible consolation, it would have negative moral implications according to Jankélévitch, an advocate of Fénelon’s theory of “pure love” (Jankélévitch and Berlowitz 126), because it ultimately implies an emphasis on self-interest that hinders a virtuous movement.

Independently of its logical, metaphysical, and moral problems, this belief in the “beyond” has left memorable traces in the arts. In his philosophy of music, Jankélévitch is aware of this contribution, when he praises the ethereal atmosphere of the last movement of Gabriel Fauré’s Requiem, “In paradisum deducant te angeli”: “May the angels lead you into Paradise. . . . May the choir of angels receive you. . .”[14] Suggestively, the soprano line that leads the choir is, in some interpretations of the Requiem, performed by pueri cantores, living “little angels,” who, in musical and imaginary terms, assume the role of the angelic choir. Therefore, it is not entirely unreasonable to admit, using Jankélévitch’s thought as the theoretical basis for this study, that a visual art like photography could also have discovered an aesthetic potential in the treatment of euphemistic or fantastic motifs (even with a reduced degree of stylization, since, in the examined photography genre, the little angel is the infant’s corpse itself).

Nevertheless, Jankélévitch would probably have viewed Chichico’s and other photographers’ depictions of the “little angels” with some degree of aversion, for the simple fact of belonging to the genre of postmortem photography. In the final interview that forms the posthumous book Penser la mort?, Jankélévitch interprets the famous portrait of “Proust on his deathbed” (106), taken by Man Ray, along with embalmed corpses, mortuary masks, and hand casts (in the case of dead pianists), as a symptom of necrophilia. Paradoxically, according to the French thinker, the cult of death and its vestiges were stimulated by Christianity (106–07), acknowledged as the “religion of love” (107) and of resurrection, a point that Chichico’s portraits somehow indicate in the combination between the infants’ corpses and religious elements. For his part, Jankélévitch, in his inclination to the ineffable mysteries of life (Jankélévitch qtd. in Suarès 117–18), expressly condemns the attachment to such objects and images, as well as their aesthetic appreciation, seeing in those attitudes nothing else than “the curiosity of death, the curiosity of horrible things, from which men must turn away, in my opinion” (Jankélévitch, Penser 107).[15] Coincidently, the philosopher touches on a problem already presented in this article’s introduction: the risk of morbid curiosity, which, in addition to its theoretical sterility, is incapable of offering genuine nourishment.

Although one cannot find any direct mention of portraits of dead infants in Jankélévitch’s work, in La Mort, the philosopher identifies something “macabre” in connecting death with a life stage rich in potentiality, such as childhood. This identification, which could have further hindered his appreciation (and the appreciation of those who consciously or intuitively coincide with his position) of such a photographic practice, appears in the following passage, one that is eloquently illustrated using examples from the visual arts:

Is death hidden inside life like that hideous skull within the face of which it is the skeleton? In any case, this hidden skull is our concern. . . . Melancholia is, perhaps, the name given by Dürer to this unconfessed concern. The opposition is diametrical between Dürer’s concern and Raphael’s insouciance: Raphael is entirely turned toward the child and nativity, toward hope and the promises of future, toward radiant positivity of color and light . . . no mistrust constricts the smile of the Madonnas, no worry fades the glow of flesh, no concern veils the serenity of innocence, the anguish of decay does not poison the blessed blooming of life. The macabre artist, on the other hand, the artist of necrophilic civilizations, disassembles, from visible positivity, a suprasensible negativity that, in turn, he makes visible and manifest. (Jankélévitch, Mort 40)

In the passage above, Jankélévitch, like Nietzsche in The Case of Wagner, implies an opposition between a Septentrional and a Meridional poetics, the former represented by Dürer’s Melencolia I (an engraving full of elements that turn it into a memento mori, whose main figure is curiously an angel in the form of a pensive young woman, seated beside a putto), and the latter by the acclaimed Madonna paintings by Raphael. However, complementing Jankélévitch’s remarks, it is important to note that, in the Italian Renaissance, “macabre” gestures can also be seen in some representations of the Virgin Mary and of the Holy Family. Niccolò Rondinelli, for example, depicts the threat of death, disguised in an idyllic ambiance, through a Madonna who does not look directly at the Infant Jesus on her lap, but at the goldfinch that foreshadows her baby’s future Passion.[16]

Obviously, regarding the portraits of the “little angels,” death is not merely a shadow seen in a small, living creature due to a perverted gaze (51), nor is it the insight afforded by an external and/or a posteriori knowledge of that individual’s entire story. Rather, it is an irrevocable reality, effectively experienced by the child’s family during the instant in which the photograph was taken. Yet even this distinction might not have been sufficient to make such portraits attractive to the French philosopher. Although he declares his artistic preference—especially in music—for a poetics of ricordanza (Jankélévitch qtd. in Jankélévitch and Berlowitz 215–16), his sensibility inclines more toward a vague and indefinite kind of remembrance, an “open nostalgia,” born not from the geographical distance from one’s homeland or from a beloved, but from the humanly shared awareness of time’s irreversibility (Jankélévitch, Irréversible 360–67). This favored nostalgic atmosphere, closer to the aesthetic categories of grace and charm than to those of the tragic and the sublime, thus diverges from Chichico’s portraits, which, although not completely devoid of grace, are marked by “determinate and motivated regrets” (Jankélévitch, Mort 270) and by a more explicit depiction.

A POINT OF CONVERGENCE: ATTESTING THE “FACT OF HAVING BEEN”

If, according to Jankélévitch, we must turn away from “horrible things” which flirt with necrophilia, then why would it still be important to value those ancient portraits and, furthermore, to relate them to the thought of that very philosopher? A suitable response, one already advanced at the end of the introduction, can now be outlined.

Interestingly, the philosopher’s own moral engagements—also expressed in his writings—diverge from the tendencies characteristic of some crucial concepts that lay the foundations for his ontology and aesthetics. First, as concerns the ontological aspect, if the ineffable events privileged by the philosopher (music, charm, charity, love, and innocence) are not permanent “beings,” but rather an “almost-nothing” (presque-rien), a “disappearing apparition” (apparition disparaissante), it is, in some contexts, an ethical task to resist precisely temporal fluidity, in its “natural” tendency towards oblivion. As in the case of the monk Pimen in Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov, who spends the night hours obstinately recording the former crimes of the Czar, Jankélévitch confesses to experience, after World War II, “the obligation to prolong within myself the sufferings that were spared from me” (Jankélévitch qtd. in Jankélévitch and Berlowitz 77). Thus, in declining to remain silent, as some of his peers do, he commits himself to keeping alive in the consciousness of his contemporary (and future) listeners and readers the constant risk of antisemitism[17] and the ineffaceable responsibility of the German nation for the Holocaust, all the while vehemently condemning the amnesty of Nazi crimes.[18] In this sense, the philosopher’s word, like the monk’s endless notes, “is not the field of the je-ne-sais-quoi and of the inapprehensible, but that of good memory and of fidelity” (65), it is “a protest against the dissipation of the past” (ibid.).

The refusal of a je-ne-sais-quoi in an attitude of fidelity to history reveals that memory should not only be preserved but built up in determinate facts. The aura of “open nostalgia,” the “desire for things that perhaps don’t exist,”[19] the expressive ambiguity that the philosopher especially admires in some modern musical poetics (Jankélévitch, Musique 35–36), are not at all applicable to an ethical commitment. Therefore, when also compared to the aesthetic sphere, the moral one asserts its distinction, as it must avoid blurred remembrances and imprecise motivations.

A sign of this unwavering dedication to preserving the memory of an absurd and painful past, without concealing the identities of the perpetrators and without neglecting the realness of the victims (even when the latter left no face or name), is evident in the following tribute, immortalized in L’Irréversible et la nostalgie:

That is the mysterious nothing (néant) of an exterminated young girl, who disappeared forever in a German camp. Nobody knows anymore either the name or even the existence of that child: that child without grave, and more anonymous than the “incognito” buried in a tomb without name, that child forever unknown is an eternal moment of history and not of all eternity, an eternal moment ever since her annihilation and then forever. That child is henceforth an indestructible past of human temporality. And we could even say: human history, at the limit, would not be what it is if the little martyr did not exist; it would be another human history, the history of another humanity. (201)

This poignant and touching passage, which appears in a slightly different formulation in La Mort (421), played a central role in the conception of this article. It suggests that a concern for a child’s precocious death and for the safeguarding of its memory might be in the horizon of Jankélévitch’s thought. In that sense, the portraits of the “little angels” somehow align with the philosopher’s ethical commitment and to an important aspect of his ontological perspective that could not be completely reduced to the “model” of the almost-nothing (although the anjinho’s life may offer a privileged example of this fundamental Jankélévitchian concept). If the religious beliefs implied in the conception of the anjinhos clearly contrast with Jankélévitch’s approach to death, which avoids the relief and the consolations of an illusory “pharmacology” (Lisciani Petrini, Charis 56, 66), the photographs of the dead infants reinforce, as the philosopher does, that there is something “indestructible” (or almost so, in the case of the photographs) in an individual human’s existence. That “indestructible” point, which “saves” us from absolute non-being, is precisely the quiddity of “having been” (Jankélévitch, Irréversible 339), i.e. the effectivity of our presence in the world during the years in which we are (or were) alive.

Therefore, an intriguing analogy can be discerned between photography and Jankélévitch’s conception of death and life. Regarding the latter, the philosopher wonders: “Compressed between the two eternities, the two infinites, the two non-beings that envelop it, emerging between prenatal inexistence and postnatal inexistence, does life not amount to the almost-nothing of an instant?” (Jankélévitch, L’Aventure). Suggestively, the “instant” of life may a posteriori become a type of eternity, just as the instant of an exposure (or the instants, in early photography) generates a lasting image. And as concerns photographic eternity (sometimes only possible, before the popularization of photography, through a postmortem portrait), this becomes particularly needed when the “instant” of life is extremely “compressed” by the initial and the final non-beings, preventing the construction of a legacy and its perpetuation through a lineage.

The anjinhos expose what is most precious in life: the evanescent and unrepeatable fact of being that will later be converted into the “fact of having been” (Jankélévitch, Mort 421). According to the philosopher’s non-religious perspective, the latter, perhaps, is the only positive element that could truly illuminate the young body deprived of the grace of movement and vitality—in Chichico’s portraits and in the memory of his or her loved ones.

We should still emphasize that, for Jankélévitch, both “being” and “having been” are universally shared, despite the attempts at ontological annihilation characteristic of genocides and the more accepted invisibilities derived from ethnic exclusion, racism, and social inequality. This inequality is exactly what permits the stark contrast between the preservation of the name of Licinia Valeria Faustina Italica, a Roman girl of the IV century, buried in a marble sarcophagus at the splendid Basilica of Sant’Apollinare in Classe,[20] and the anonymous Jewish girl, deceased in the still recent 20th century, who is beautifully honored by the philosopher.

Like Jankélévitch’s tribute, Chichico’s portraits of the anjinhos extend an acknowledgement of the fact of “having been” to excluded and marginalized groups. As already mentioned, the photographer’s work distinguished itself from that of his peers, in part by being uncommonly inclusive. That feature is particularly evident in the photographs discussed. Whereas many of the living children portrayed by the photographer clearly come from wealthy families, most of his anjinhos seem to belong to disadvantaged groups. These socio-economical distinctions are made evident by the photographs’ settings (many of the anjinhos’ portraits are taken either in or near the residence of the deceased), the portrayed individuals’ clothing, and—unfortunately, in a country where slavery had only been abolished a few decades earlier—their phenotypic traits. Therefore, in Chichico’s oeuvre, the deceased Afro-Brazilian infants of Diamantina and its surroundings not only had access to postmortem photography but also became the protagonists in his renditions of the “little angels” genre.

The significance of this access and protagonism is highlighted by the fact that the posthumous title of anjinho was not always an inclusive one in the Brazilian context from Colonial to Old Republican eras. Although some parish records from 18th-century Minas Gerais document the death of a “slave little angel” (“anjinho escravo”),[21] this title was eventually denied to Afro-Brazilians, even in post-slavery Brazil. This fact is not surprising, since, in Iberian culture as early as the 16th century and in the dominant iconography of the Renaissance and the Baroque, the fair type is often “identified with angelic and divine characters, as opposed to the dark-skinned, who are associated with fallen angels, the wicked, the evil, the traitors” (Freyre 71).

Regarding a recorded denial of the anjinho title to an Afro-Brazilian baby, Câmara Cascudo recounts an incident in which a black man, probably in the early 20th century, approached the public cemetery of a city of the state of Pernambuco, in the Northeast of Brazil, seeking information on how to bury his son. A funeral service employee

asked him, in a pedantic tone, what the corpse’s causa mortis was, and the father, tearfully, retorted: “What corpse, damn it! You call my son a corpse just because he was black and poor. If he were the son of a wealthy white man, you would call him an angel, shameless man!” (qtd. in Câmara Cascudo 59)

Returning to the ways of eluding death recognized by Jankélévitch, it was not possible for the grieving black family to substitute the “scabrous monosyllable” corpse for the discussed euphemism. Even in our time, in which many children do not survive perilous journeys toward the destination of a new country, in which so many individuals are deprived of civil documentation (as dramatically portrayed in the Lebanese film Cafarnaüm, whose protagonist is precisely an invisible child), and in which thousands of innocents are massively exterminated in Palestine, we have become desensitized to the unjust fact that not everyone has the right to memory, let alone to an embellishment of memory.

We may conclude this article by stating that the embellishment of memory should not be understood merely as a euphemism which, often involving some degree of bad faith, serves as a strategy to elude the abyss of death. From this perspective, Chichico’s anjinhos respond to a legitimate urge to ensure human dignity—an urge that is in tune with Jankélévitch’s ontological and anthropological conception. “The indestructible mystery of a completed existence that is forever affirmed” (Jankélévitch, Irréversible 338) through death is reaffirmed—and beautifully so—through Chichico’s portraits.

Authors

Works Cited

Alkmim, Paulo Francisco Flecha de. “Chichico Alkmim: A Retouched Photo.” O Olhar Eterno de Chichico Alkmim, edited by Flander Sousa and Verônica Alkmim França, Editora B, 2005, pp. 98–105.

“Barbacena, Minas Gerais, Brazil registros. Imagens.” FamilySearch, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:9Q97-Y33D-MDM?view=index, accessed 21 Jan. 2025.

Bonino, Serge-Thomas, OP. Angels and Demons: A Catholic Introduction. Translated by Michael J. Miller, Catholic U of America P, 2016.

Bru Zane Mediabase. “Quartet for Piano and Strings No. 2 in G minor, Op. 45 (Gabriel Fauré).” Bru Zane Mediabase: Digital Resources for French Romantic Music, 25 Sept. 2023, https://www.bruzanemediabase.com/en/exploration/works/quartet-piano-strings-no-2-g-minor-op-45-gabriel-faure, accessed 22 Jan. 2025.

Cafarnaüm. Directed by Nadine Labaki, performance by Zain Al Rafeea, Mooz Films, 2018.

Câmara Cascudo, Luís da. Dicionário do Folclore Brasileiro. Melhoramentos, 1979.

Cruz Lichet, Virginia (de la). Frontières: appel de proposition de manuscrits et appel à communications pour un colloque en mai 2026. Mort et dispositifs scénique. Frontières, 2025, https://www.frontieres.org/_files/ugd/2da07c_413415d456ec4fc9beab41e78d6a3b6e.pdf, accessed 8 May 2025.

Cruz Lichet, Virginia (de la). “Image de la Mort et la Mort en Images: Représentations et Constructions Visuelles.” Amerika: Mémoires, Identités, Territoires, vol. 9, 2013. https://doi.org/10.4000/amerika.4228

Delumeau, Jean. Il Peccato e la Paura: l’Idea di Colpa in Occidente dal XIII al XVIII Secolo. Translated by Nicodemo Grüber, Mulino, 1987.

Duarte, Denise Aparecida Sousa. “Em Vida Inocente, na Morte Anjinho: Morte, Infância e Significados da Morte Infantil em Minas Gerais (séculos XVIII–XX).” 2018. Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Doctoral dissertation.

Freyre, Gilberto. Casa-Grande & Senzala: Formação da Família Brasileira sob o Regime da Economia Patriarcal. Global, 2003.

George, François. Préface. Vladimir Jankélévitch: les Dernières Traces du Maître, by Jean-Jacques Lubrina, Félin, 2009, pp. 13–15.

Instituto Moreira Salles. Chichico Alkmim, Fotógrafo (IMS Paulista). Instituto Moreira Salles, https://ims.com.br/exposicao/chichico-alkmim-fotografo-sp/, accessed 1 Dec. 2024.

Jankélévitch, Vladimir. L’Aventure, l’Ennui, le Sérieux. Flammarion, 2023. E-book.

Jankélévitch, Vladimir. L’Imprescriptible. Pardonner? Dans l’honneur et la dignité. Seuil, 1986.

Jankélévitch, Vladimir. L’Irréversible et la nostalgie. Flammarion, 1974.

Jankélévitch, Vladimir. La Mort. Flammarion, 1966.

Jankélévitch, Vladimir. La Musique et l’ineffable. Seuil, 1983.

Jankélévitch, Vladimir. Penser la Mort? Liana Levi, 1994.

Jankélévitch, Vladimir, and Béatrice Berlowitz. Quelque Part dans l’Inachevé. Gallimard, 1978.

Junqueira dos Santos, Carolina. “O corpo, a morte, a imagem: a invenção de uma presença nas fotografias memoriais e post-mortem.” 2015. Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Doctoral dissertation.

Lisciani Petrini, Enrica. Charis: Saggio su Jankélévitch. Mimesis, 2012.

Lisciani Petrini, Enrica. “Risposta.” Email to the author. 27 Nov. 2024.

Luccock, John. Notas sobre o Rio-de-Janeiro e Partes Meridionais do Brasil: Tomadas durante uma Estada de Dez Anos nesse País de 1800 a 1818. Translated by Milton da Silva Rodrigues, Livraria Martins, 1951.

Muti, Riccardo, and Armando Torno. Recondita Armonia: Educare alla Musica per Educare alla Vita. Rizzoli, 2024.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. The Gay Science: With a Prelude in Rhymes and an Appendix of Songs. Translated, with commentary, by Walter Kaufmann, Vintage, 1974.

Pelegrín, Maricel. “Desde el Mediterráneo a Tierras de Quebrachos: el Vetlatori del Albaet en Valencia y su Correlato en el Velorio del Angelito en Santiago del Estero.” Espéculo: Revista de Estudios Literarios, no. 30, 2005.

Ravenna Città d’Arte. Salbaroli, n.d.

Recalcati, Massimo. La Luce delle Stelle Morte: Saggio su Lutto e Nostalgia. Giangiacomo Feltrinelli, 2023.

Schwarcz, Lilia Moritz. Imagens da Branquitude: a Presença da Ausência. Companhia das Letras, 2024.

Silva Santos, Dayse Lúcide da. “Cidades de vidro: a Fotografia de Chichico Alkmim e o Registro da Tradição e a Mudança em Diamantina (1900 a 1940).” 2015. Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Doctoral dissertation.

Storia e Memoria di Bologna. “Brutus Ricci (29 Giugno 1871–15 Aprile 1874).” Storia e Memoria di Bologna, https://www.storiaememoriadibologna.it/archivio/persone/ricci-bruto, accessed 3 Feb. 2025.

Suarès, Guy. Vladimir Jankélévitch: Qui Suis-Je? La Manufacture, 1986.

The Canons and the Decrees of the Council of Trent. Translated by Theodore Alois Buckley, George Routledge, 1851.

Tribuzzi, Iara Ramos. Personal interview. 26 Nov. 2024.

Footnotes

- 1 As Lisciani Petrini, one of the most prominent scholars of Jankélévitch’s thought, sums up, there is “in the people of our time a growing horror of death and, consequently, an obstinate ‘anesthetizing’ flight from it and from the ‘dying patient,’ and even now from funeral rites and symbols themselves, which have been replaced by increasingly depersonalized practices and ‘mass-produced’ articles” (Charis 58–59).

- 2 All the non-English texts quoted in this article that appear in the “Works Cited” section are my own translations.

- 3 See The Canons and Decrees of the Council of Trent (132), session XXI, chapter IV.

- 4 This insurmountable ontological difference could be apprehended through the entry “angel” in the Vocabulario portuguez & latino (1712), by Raphael Bluteau, where the celestial creature is defined as “a created, intellectual, spiritual, and complete substance. A substance because it is an entity, capable of subsisting by its own; created because it is extracted from nothing; intellectual because it is provided with understanding, with which it understands things in one single and simple intuition, without discoursing, combining one thing with the other; and complete, because, by its own hypostasis, it is its only complement” (qtd. in Duarte 128, emphasis in the original). Obviously, none of those traces is shared by a human, who, moreover, is always an individual, unlike an angel, who, according to Saint Thomas of Aquinas (Summa theologiae I, q. 50, a. 4), is always the perfect representative of an entire species, escaping from the multiplicity of earthly beings (Bonino 124–26).

- 5 The document establishes that “in the funerals of children, just as in those of adults, the bells should not be rung; if they are rung, they should not sound mournfully, but festively. The garments appropriate to the child’s age are also prescribed, as well as the use of flower crowns or aromatic herbs to indicate the integrity and virginity of their body, along with the use of a stole and white surplice for the parish priest and priests” (Duarte 77).

- 6 According to Pelegrín, the extremely joyful funerals of the “little angels” were widespread across the countries of Spanish-speaking America, where they have been maintained up to the present day in the province of Santiago del Estero (Argentina), among rural populations. She also hypothesizes that the Velorio del Angelito in Hispanic America originated from the Vetlatori del Albaet in the Spanish region of Valencia, a practice that may have continued until the first decades of the 20th century.

- 7 A comprehensive bibliography on the ancient and internationally shared practice of postmortem photography—which includes titles examining the portraits of deceased infants—is provided by Virginia de la Cruz Lichet (2025). As the present article focuses on the occurrence of this practice in Brazil, another text should be added to the aforementioned bibliography: the doctoral dissertation “O corpo, a morte, a imagem: a invenção de uma presença nas fotografias memoriais e post-mortem” by Carolina Junqueira dos Santos.

- 8 It is important to note that even in the work of a photographer with social concerns—Chichico was a member of the charitable and educational institution União Operária Beneficente de Diamantina (Silva Santos 59)—and committed to portraying Afro-Brazilian individuals in an affirmative way, undeniable traces of social exclusion can still be found. One of his portraits, which received a prominent place in the exhibition Chichico Alkmim, Fotógrafo, captures two female figures who, while flanking the central four members of a well-to-do white family, hold the backdrop of a bucolic landscape. According to Lilia Schwarcz, the figure on the right is “the photographer’s wife—Maria Josefina Neto Alkmim, or simply Miquita—known as his right hand in the studio” (184), while the one on the left is “a barefoot black girl, a little disheveled,” wearing a “dirty and stained” white dress that “was evidently a work outfit” (185). The girl stands in stark contrast not only to the white children in the portrait (from which she was probably cropped in the photo’s final version) but also to Chichico’s other portraits of “Afro-descendant figures, immortalized in refined clothes, carefully styled hair, and fashionable shoes” (ibid.). The presence of the girl in the photographic plate inadvertently denounces the shocking inequality in post-slavery Brazilian society, a situation that directly affected Afro-Brazilian children, who were often adjuncts of white families, reduced to the condition of “common laborers, with no right to education or protection” (ibid.).

- 9 This collection has been held since 2015, under a loan agreement, in the Moreira Salles Institute (Rio de Janeiro), the most important photography archive in Brazil.

- 10 See “The Madman” in The Gay Science, Book 3, §125 (Nietzsche 181–82).

- 11 The Diocese of Diamantina was created on 6 June 1854, and elevated to Archdiocese on 28 June 1917.

- 12 Besides euphemism, Jankélévitch recognizes two other possible ways of avoiding the “mortal nothingness”: the apophatic inversion and the conversion to the ineffable, which he identifies as his own strategy. The former is the simple and consistent act of falling silent before unsayable death, and the latter, according to the explanation of Lisciani Petrini, “the consciousness that we cannot truly speak of death and despite that—it would be better to say precisely because of that, not despite that—we speak infinitely on it, knowing that it is exactly what keeps us inside life” (“Risposta,” emphasis in the original). Therefore, death is paradoxically converted into its opposite by the philosopher, who concludes La Mort with a suggestive affirmation of the fecundity of life itself.

- 13 The fact that this conception of a dead child as a “little angel” and other similar infant funeral rites were also present in Europe, within a context of religious consolation and embellishment of death, disavows Freyre’s theory.

- 14 One of the philosopher’s encomiums of this concluding movement may be found in La Musique et l’ineffable (126–27).

- 15 Although the philosopher does not mention it, an emblematic example of a “horrible thing,” questionably embellished and converted into an object of Christian cult, is the Heilige Munditia (Saint Peter’s Church, Munich), the skeleton of an alleged female martyr from the first centuries of our era, ornamented with a crown, pieces of cloth that do not disguise her bones, colored stones, false eyes, and rotten teeth.

- 16 Madonna col Bambino (Virgin and Child) (1490–95). Oil on panel, 63 x 50.5 cm. Palazzo Barberini, Rome.

- 17 Although the philosopher argues that antisemitism must be distinguished from other forms of discrimination, such as racism (Jankélévitch qtd. in Jankélévitch and Berlowitz 197–99), he was not only concerned with the constant risk of Jewish persecution but also sensitive to the plight of Palestinians oppressed by the State of Israel in the early 1980s (George 13–14).

- 18 This theme is developed in Jankélévitch’s short but impactful essay “L’Imprescriptible,” initially published in the Revue Administrative in 1965, and included in the posthumous volume L’Imprescriptible (1986).

- 19 These words—used by Gabriel Fauré in a letter written to his wife, on 11 September 1906, to describe the genesis of the third movement of his Piano Quartet No. 2 in G minor, Op. 45 and to outline the characteristic expressiveness of music—were often quoted by the philosopher (Bru Zane Mediabase). There are four references, in La Musique alone, to that nostalgic “désir des choses inexistantes” (75, 96, 104, 130).

- 20 The lapidary inscription says: “To Licinia Valeria Faustina Italica, who sleeps in peace and lived one year, six months and six days. Very sweet daughter, sorrowful parents (erected)” (Ravenna Città d’Arte 26).

- 21 Among those records, one, dated 28 August 1720, belongs to the Matriz de Nossa Senhora da Assunção in the city of Mariana (Duarte 153) and the other, dated 15 April 1756, to the Matriz de Nossa Senhora da Piedade in the city of Borda do Campo (now known as Barbacena) (see “Barbacena”).