Urban Un/Belonging: Translating Pre-Partition Spaces in Old Rawalpindi, Pakistan

National University of Modern Languages, Islamabad

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9886-3573

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9886-3573

Abstract

In this article, I propose a transgressive re/inscription of the city spaces of Old Rawalpindi through the lens of Sherry Simon’s integrated translational city theory. In the wake of the 1947 partition of the Indian sub-continent into the Muslim-majority Pakistan and the Hindu-majority India, a large number of Hindus, Sikhs, and Jains living in Rawalpindi migrated to India. The numerous houses and other buildings that they left behind have been variously re/purposed, abandoned, and re/occupied by the Muslims arriving from India. The data for this study consists of documentation of these buildings, official websites and studies, interviews with the im/migrants and locals, and the researcher’s observations. The in/consistencies between the official versions and those of the current and past residents, crucially highlighted by the digital media, suggest multiple identities and a semiotic un/belonging.

Keywords: city translation, 1947-partition, Rawalpindi, Imperial India, the Indo-Pakistan sub-continent, digital media.

INTRODUCTION[1]

In this research study, I deploy an integrated translational framework for an analysis of the old city of Rawalpindi, a historical district located in the Punjab, the most densely populated province of Pakistan. Although it had one of the largest populations of non-Muslims before the 1947 partition of the Indian subcontinent, only a few thousand remain in the city and the surrounding areas. Rawalpindi’s designation as a translational urban space (Simon, “Translational City”) is based on linguistic and non-linguistic transactional hierarchies and is supported by notions of resemiotisation as presented by Otsuji and Pennycook. I also draw upon the concept of collective and contentious identities, as problematised by Bourhis, to capture the liminal reality of Rawalpindi: it seems to straddle different temporalities and spaces, as evidenced in its buildings dating back to pre-partition days.

The partition of Imperial India took place at the demand of the Muslims who wanted a separate country (presently Pakistan and Bangladesh) to be formed in Muslim-majority areas. The Hindus, Sikhs, and Jains in the latter territories were given a choice: either continue living in the newly formed Muslim country or move to India. For many non-Muslims, the decision to emigrate was the result of communal riots, which saw neighbours turn against one another, with thousands killed on both sides. While it is not the purpose of this study to dwell on the reasons for this brutality, it must be stated that for many non-Muslims in Rawalpindi the migration was an “involuntary” one (Bharadwaj, Khwaja, and Mian 6). They left behind Hindu temples, Sikh temples, Jain schools, and private residences, many of which sites have been re/occupied by the Muslim immigrants from India. Some have been re/purposed or abandoned. The buildings and structures, mostly in poor condition, entangle the present city in their rich and contentious past.

For context, in the current study, I revisit the broader theorisations of pre-partition spaces in Pakistan that advocate for maintaining and protecting this heritage as it can promote religious tourism (Jatt; Farooqi and Arif; Schaflechner; Kermani; Chawla et al.; Ashraf et al.; Dhaliwal; D’Agostino; Hameed et al.). Foregrounded in them is a notion of collective multiple identities; my study offers a provocation by drawing on the lens of urban translation (Simon, “Translational City”). Zeroing in on the spaces in the old district of Rawalpindi, I subscribe to the view that translations of space entail much more than a straightforward transfer between two or more languages (Jakobson). Spatial translations are inspired by the view that a city is a text (Fritzsche; Remm) that can be read and consequently translated. Rawalpindi provides ample opportunity to be reconfigured as an “anomalous translation,” which embodies “transformation and difference” that may even “eclipse the original (the ‘real thing’, if there is one at all) to become more real than real” (Lee 1–2).

A case study approach is used here as it enables the researcher to “construct cases out of naturally occurring social situations” (Hammersley and Gomm 6). As a “semiotic assemblage” (Pennycook 82), the data for this study comprise various meaning-making resources such as pictures, engraved texts on buildings, observations, official websites, and other documents, discussions with present and past residents, as well as information culled from dedicated Facebook pages. The various types of data collection and background reading on the subject have resulted in the following research question: in what ways can Old Rawalpindi space be translated as a transgressive re/inscription?

Rawalpindi, the birthplace of the Sikh religious sect Nirankari (Yasin), has managed to retain the names of marketplaces and neighbourhoods as given by its former residents; for example, Nirankari and Bhabra Bazaars, Aria Mohallah, Amar Pura, Kartar Pura, Hari Pura, Krishan Pura (Hassan). The element of subversion implied in a transgressive re/inscription (“Reinscription”) is particularly useful since the latter practice is designed as an “identity-forming discourse” (Bennett 159) that challenges the current in/visibility of the old city by attempting to re/write its history.

THE TRANSLATIONAL CITY: AN INTEGRATED THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

The critical concepts adapted from the theory of the translational city (Simon, “Translational City” 16) are: 1) nationalist makeovers; 2) dual cities; 3) migration, presencing, and translanguaging; 4) mediation and mediators. They are consistent with the notions of social identities (Bourhis), rewriting history (Waksman and Shohamy), absent presence (Gergen), and semiotic actants (Otsuji and Pennycook). Thus, it is possible to “radically re/imagine” (Deumert and Makoni 240) the old city space of Rawalpindi as a transgressive re/inscription.

The concept of the nationalist makeover (Simon, “Translational City” 17) has “linguistic nationalism” at its heart. It is enacted by erasing a city’s former non/linguistic signs and replacing them with new meaning-making practices—generally aligned to power sources. A complete erasure is carried out by changing the urban design, alongside linguistic expunging: for example, the Greek city of Salonica (now Thessaloniki), where “[t]races of the Ottoman past and even the street layout of the densely packed Jewish quarters were wiped out,” resulting in “the realignment in parallel of both linguistic and built heritage” (17). Both of these examples of nationalist makeovers are relevant for Pakistan, a country formed in the name of Islam, which indirectly led to the migration of non-Muslims to the neighbouring Hindu-majority India.

Another of Simon’s tenets is the dual city, i.e. an urban space where “more than one language group feels entitled to the same territory” (18). Although Brussels, Barcelona, and Montreal are called “bilingual” cities, “tensions prevail” due to each language’s sense of entitlement over the city space. This duality may be heavily dependent on “the formative powers of translation in specific language relationships and the inscription of this dialogue onto the physical spaces of the city” (19). It assumes a special importance in the “rewriting” (Waksman and Shohamy 59) of Rawalpindi’s past and present as it focuses on an in/erasable legacy that is shared but contentious—subscribed to by the previous and the current dwellers.

Also useful are Simon’s notions of migration, translanguaging, and presencing, since Rawalpindi has a large number of im/migrants. A translational space is defined by migration when there is “traffic between the place of origin and the diasporic home” (Simon, “Translational City” 19). Translanguaging refers to a situation in which im/migrants “bring and mesh languages together for a range of meaning-making and communication purposes” (Spilioti and Giaxoglou 278). The element of presencing relies on digital media as “[v]irtual presence modifies material presence” (Cronin qtd. in Simon, “Translational City” 19). In my analysis, I also draw upon further conceptualisations of presencing as elaborated by Gergen and Gozzi, both of whom argue that the use of technology creates a present that is “simultaneously rendered absent” (Gergen 230). As evidenced by the following analytical sections, digital media platforms were helpful in understanding different facets of the old city of Rawalpindi.

The last tenet of Simon’s framework concerns mediation and mediators. The latter act as “intermediaries” between cultures as they are expected to have more understanding than a translator, who relies solely on linguistic exchange (Simon, “Translational City” 20). They are the “anonymous heroes” facilitating interaction in urban spaces (de Certeau qtd. in Simon, “Translational City” 20). Their ability to use two or more languages also enables them to “respond to and/or shape political attitudes and nationalist sentiments” (Sywenky 177). Although Sywenky uses the concept in a colonial context, it is well-suited to a city like Rawalpindi since an element of departure, both physical and metaphorical, is involved. This idea is expanded upon by Otsuji and Pennycook (59–60), who go beyond “linguistic boundaries” and focus on “assemblages of people, objects, space, and language”: semiotic actants use all available meaning-making resources.

OLD RAWALPINDI AS A TRANSGRESSIVE TRANSLATIONAL SEMIOTIC TEXT

Employing an adapted version of Simon’s urban translational space categories, I explore the past and present life of the old city of Rawalpindi and attempt to build a transgressive account that relies on juxtaposing the linguistic elements with the dilapidated and re/purposed physical space. I demonstrate how the intertwining of the two contributes to a semiotic reading that focuses on shared and contested identities and legacies by relying on aspects related broadly to ideologies, translanguaging, and presencing.

IDEOLOGICALLY-DRIVEN MAKEOVER

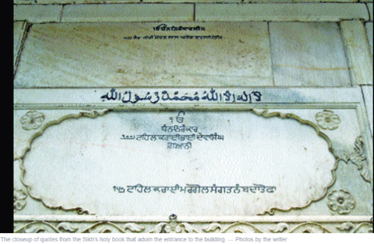

As referenced in the previous section, the first category concerns a partial or total erasure of the signs (linguistic or otherwise) to assert the city’s new sensibilities. A building complex found in the Nirankari area of the old town has undergone a partial makeover in such a way that aspects of Islam were incorporated without erasing the Sikh religious invocations. Since 1958, the Sikh temple has been repurposed as the Government Simla Islamia High School for Boys. During the interviews which I conducted, some of the area’s residents referred to it by its new identity. When I pointed out that it was also a temple, they admitted that this was still present on the premises, thus implicitly accepting the place’s hybridity. The picture below illustrates the point:

The original carving is in Gurmukhi, the official script of the Indian Punjab; it is a Granth prayer that roughly translates as “Glory, Glory to the Formless one”; many such carvings can still be seen. There is no evidence of attempts to erase the script. The headmaster, though a Muslim himself, seems to advocate a plurality of religions, and does not wish for any of the signs to be erased (Hassan; Haider). A Muslim declaration of faith (“There is no God but Allah, and Muhammad is the messenger of Allah”) has, however, been carved directly over the Sikh prayer. While this points to the co-existence of the two identities, the superscription of the Muslim prayer can be read as an attempt to assert the religious superiority of the new residents.

A somewhat similar effort at preserving the old identity while projecting a new one is seen in Fig. 2 below. It shows the façade of a palatial house that belongs to a rich Hindu merchant. The place is still used as a private residence, and the new owner has retained the building’s previous identity. He has, however, put up a banner of his name, “Haveli Meer Baba” (“Meer Baba’s Mansion”), along with an Islamic invocation that is used to ward off the evil eye. The place retains the original Hindi carving, “Durga Nivas,” i.e. “The Residence of Durga,” a Hindu goddess.

Courtesy of the author.

THE DUAL CITY AS AN IN/ERASABLE LEGACY

The old city of Rawalpindi can be considered a dual space. This duality is especially noticeable in the articulation of its official stance in its documents and websites, and is challenged by the locals. As already emphasised, even after 77 years, the streets, bazaars, and neighbourhoods are still called by their old names. The original designations of Rawalpindi’s neighbourhoods exist in some of the official documents, but not on the two official websites (“About Rawalpindi”; “District Rawalpindi”). For example, in an official report prepared by the auditor general of Pakistan (Jehangir), old names such as Ariya Mohallah, Amar Pura, Kartar Pura, Hari Pura, Angat Pura, Bagh, are used. By contrast, in another historical city of Pakistan, Lahore, the official effort to rename neighborhoods was rejected by the locals, who prefer using the old street designations (Mahmood).

While both the official websites of Rawalpindi acknowledge the plural history in general terms, neither makes mention of the languages that were once spoken by the majority, namely Hindi and Gurmukhi. The omission is glaring, since one website lists as many as seven dialects of the Punjabi language currently spoken by 90% of the inhabitants. However, it does not mention the languages of the “other” 10%, which include Sanskrit, Hindi, and Gurmukhi, as there are still Hindus and Sikhs living in the area (“District Rawalpindi”).

The duality of Rawalpindi is further amplified by another in/visibility on the municipal website (“About Rawalpindi”). The screenshot below (Fig. 3) shows pre-Partition Era temples—the Hindu mandirs with brown towers and the Sikh gurdwaras with brown domes—alongside the mosques distinguished by smaller white domes. On the ground, no road signs erected by the municipal authorities point to the presence of the temples; the skyline, however, defies such erasure.

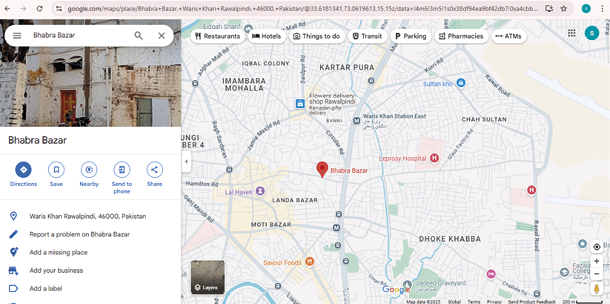

The names of neighbourhoods and markets—mentioned neither on the official websites nor on the ground, in the form of plaques—are nevertheless present on Google Maps, e.g., Bhabra Bazaar and Kartar Pura, as shown in Fig. 4 below. This points to the crucial role of digital media in re/imagining Rawalpindi.

IM/MIGRATION, ABSENT-PRESENCE, AND TRANSLANGUAGING

An important aspect of digital media is evident here. On the one hand, a presence can be rendered absent through digital media or technology (Gergen; Gozzi). On the other, a digital presence can compensate for a physical absence (Cronin qtd. in Simon, “Translational City” 19). Meanings thus produced are no longer dependent on language proper, but can also emerge from physical spaces. The three concepts—im/migration, absent-presence, and translanguaging—overlap in the case of Rawalpindi. For example, in the picture below, the engraved Sanskrit word om is an invocation in Hinduism and Jainism, “mystically embod[ying] the essence of the entire universe” (“Om”).

As with most Hindu temples—which, unlike the Sikh ones, take up very little space—this particular temple is part of a private residence. Asked about the meaning of the engraved text, the current inhabitant, an elderly immigrant Muslim woman, erroneously replied that it is part of a Hindu peace greeting, om shanti om, translated as “peace be upon you,” or “peace to all,” adding that it was similar to the Muslim greeting asalam-o-alaikum (“Om”). The implicit point may have been a similarity between Islam and Hinduism, although the reply—hummed in a particular rhythm—evidently also stemmed from a knowledge of Indian (Bollywood) movies: “Om Shanti Om” is a popular Indian song. The respondent’s translanguaging thus points to the digitally fluid borders between India and Pakistan; borders that do not require cumbersome bureaucratic visas.

In comparison, Reena Verma, a 90-year-old former resident of Rawalpindi and a migrant to India, was able to visit her old home in 2022, after 75 years (Noor; “Reena Verma”). She managed to trace her former home through various Facebook pages dedicated to the partition of the Indian sub-continent (e.g., “Pak India Heritage”). In both cases, the absent-presence is evident. The inhabitant of the temple uses digitally available Indian movies to feel close to her former home in India, and in the process moves away from her present. Reena Verma employs social media to render the absence into presence; she can physically visit Rawalpindi courtesy of links and information gathered through Facebook. To some extent, the internet has humanised distances and im/migrations.

MEDIATORS AS SEMIOTIC ACTANTS

The last of the categories of the integrated framework refers to translators who exhibit an intimate knowledge—either physical or digital—of a given place. These need not be professional translators who use two or more languages for a living; rather, they are mediators and semiotic actants (Otsuji and Pennycook) who offer a version that relies on semiotics, including both language and non-language.

For this study, the “anonymous heroes” (de Certeau qtd. in Simon, “Translational City” 20) are the current residents of the old city, including local journalist Haider and my two Indian friends, Abbas Razvi and Gita, who helped verify certain words and phrases. I was also in touch, via Facebook, with the aforementioned Ms. Reena Verma. Whereas my X and Facebook friends could only assist with verifying the translations, Haider helped me on the ground. As someone whose parents migrated to Pakistan, leaving their properties in India in 1947, Haider is committed to preserving the memory of those who left for India. Not only did he provide valuable leads, like pointing out the absence of the names of old neighbourhoods from the street plaques, but he also demonstrated that even the rudiments of language, when used within a particular space, could prove sufficient for generating a meaningful conversation. For example, the picture below (Fig. 6) is of a school for girls, set up by the Jain community of Rawalpindi. The name of the school is written in the three languages of the area: English, Hindi, and Urdu. Haider pointed out that, rather than restrict the site to members of their own community, the school administration apparently wanted to emphasise inclusivity.

Courtesy of the author.

DISCUSSION AND DIRECTIONS FOR FUTURE STUDY

Two major motifs emerge in the translational-semiotic re/worlding of the old spaces of Rawalpindi: ambivalence and the power of the internet. These intertwined themes reinforce the “perpetual state of dissonance” to which Simon refers, where “the harmony of the original [is] lost forever” (Simon, “Translational Life” 405). The element of un/certainty that pervades the discourse of the place owes its current re/imagination, in part, to digital media, including both social media apps like Facebook, Instagram, X, and WhatsApp, and digital navigation apps like Google Maps (Gatti and Procentese). They help to problematise the prevailing reality which is assumed to be stable enough to turn the clock back on the disruptions set in motion by the partition 77 years earlier.

The provocative un/settling implied in the current study’s transgressive re/inscription enables a re/writing of identities that arise from the old spaces (Waksman and Shohamy 59). Ambivalence lies at the very core of how these identities are negotiated digitally and physically. In agreement with Shohamy, Ben-Rafael, and Barni, who argue that, due to the power of the internet, identities in the global world have become “un ensemble (one whole)” (xviii), my study also suggests that these identities are fluid and impermanent. The old temple resident’s (false) parallel between Muslim and Hindu greetings; the headmaster’s preserving of Sikh religious invocations with Islamic ones inscribed above them; official websites with im/partial information—all these instances produce a sense of ambivalence, seemingly dependent on the power of social media, and the internet more generally. It is not clear whether the woman who inhabits the temple made the equivalence purposefully; it is difficult to attribute absolute intentions to the headmaster; the Jain school administration may have simply wanted to attract students from all linguistic backgrounds. Such a sense of plurality could also be influenced by access to social media. Similarly, the omission of street names and languages from official websites could be a case of negligence or a deliberate effort to nudge people towards nationalism—as in Lahore, where, despite the local inhabitants’ rejecting the new names, they are in use in certain official documents. Google Maps—reliant on real-life data collected from various sources, including the locals (Lookingbill and Russell)—prefer using names with which the local population is familiar.

My study also points to another kind of ambivalence, one that pervades conventional partition discourse (e.g., Jatt; Farooqi and Arif; Kermani; Hameed et al.), which mostly focuses on reviving religious tourism and the preservation of the pre-partition spaces’ cultural-historical value. This discourse mostly relies on bureaucratic exercises that may or may not come to fruition. Social media, on the other hand, challenges the in/visibility of the decaying structures by allowing the new and old owners to come together, albeit for a short while, to reminisce about the past. While not wholly negating the importance of religious tourism, this study suggests that it should only be a first step in ensuring temporal and spatial justice for the old spaces of Rawalpindi.

This brings the discussion to the limitations of the current study and possible directions for future endeavours. The epistemological nature of the framework used for my research offers a range of perspectives, and conducting in-depth interviews would have resulted in a report-length study rather than a journal article. Undoubtedly, there is potential for more extensive future research, which might entail locating dis/similar discourses in the smaller cities neighbouring Rawalpindi as the area was heavily populated by Hindus and Sikhs before the partition. Yet another direction would be to study Google Maps by focusing on the inconsistencies in data provided by official and local sources, because the app also relies on municipal authorities, whose data may be at odds with those offered by the locals.

CONCLUSION

To conclude, this study re/imagines a semiotic un/belonging of Old Rawalpindi with the help of Sherry Simon’s translational city theory, coupled with the notion of the all-encompassing “protagonists,” as proposed by Otsuji and Pennycook (70). Drawing from Fritzsche’s postulation that the city is a text that can be read and translated, I view the old city of Rawalpindi as re/initiating conversations that are enacted through the collectivity of language, digital media, and concrete spaces. The nexus of these three points leads to an extension of Otsuji and Pennycook’s assemblage, adding the internet to “peoples,” “languages,” and “the extended repertoires of . . . events” (70).

The current re/configuring highlights not just the dilapidated conditions of the pre-partition buildings and the associated ambivalent identities, but sets a direction for future re/workings of similar spaces across the Indo-Pakistan sub-continent. While acknowledging that the richness of the views expressed here are, to a large extent, supplemented by digital media, it should also be pointed out that the internet has an undeniable potential to re/create an alternative, parallel world. The current study demonstrates that the information stored on the internet—presence and absence built digitally—opens up the old spaces of Rawalpindi to constructions that might not have been possible otherwise.

Authors

Works Cited

“About Rawalpindi.” Rawalpindi Development Authority, https://rda.gop.pk/rawalpindi/, accessed 24 July 2025.

Ashraf, Muhammad I., Muhammad Saleem Akhter, and Iqra Jathol. “Peace Building through Religious Tourism in Pakistan: A Case Study of Kartarpur Corridor.” Pakistan Social Sciences Review, vol. 3, no. 2, 2019, pp. 204–12. https://doi.org/10.35484/pssr.2019(3-II)16

Bennett, Susan. Performing Nostalgia: Shifting Shakespeare and the Contemporary Past. Routledge, 2013. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315003085

Bharadwaj, Prashant, Asim I. Khwaja, and Atif R. Mian. “The Partition of India: Demographic Consequences.” SSRN, 5 Nov. 2008, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1294846, accessed 24 July 2025. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1294846

Bourhis, Richard, Y. “The English-Speaking Communities of Quebec: Vitality, Multiple Identities and Linguicism.” The Vitality of the English-Speaking Communities of Quebec: From Community Decline to Revival, edited by Richard Y. Bourhis, CEETUM (Université de Montréal), 2008, pp. 127–64.

Chawla, Muhammad I., Muhammad Hameed, and Syeda Mahnaz Hassan. “The Jain History, Art and Architecture in Pakistan: A Fresh Light.” Journal of the Research Society of Pakistan, vol. 56, no. 1, 2019, pp. 217–27.

D’Agostino, Glauco. “Pakistan: Blend of Traditions, Faiths and Architectures.” Geopolitica. Revistă de Geografie Politică, Geopolitică şi Geostrategie, vol. XVII, no. 80, 2019, pp. 1–20.

Deumert, Ana, and Sinfree Makoni. “Decolonial Praxis and Pedagogy in Sociolinguistics: Concluding Reflections.” From Southern Theory to Decolonizing Sociolinguistics: Voices, Questions and Alternatives, edited by Ana Deumert and Sinfree Makoni, Multilingual Matters, 2023, pp. 239–53. https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.22679664.17

Dhaliwal, Ravi. “Platform for Kartarpur Shrine View Is History.” The Tribune, 8 May 2019, https://www.tribuneindia.com/news/archive/punjab/platform-for-kartarpur-shrine-view-is-history-769633/, accessed 24 July 2025.

“District Rawalpindi.” Rawalpindi Development Authority, https://rawalpindi.punjab.gov.pk/overview, accessed 24 July 2025.

Farooqi, Mariam S., and Rida Arif. “The Lost Art of Rawalpindi.” Thaap: Culture, Art & Architecture of the Marginalized & the Poor, 2015, pp. 31–44.

Fritzsche, Peter. Reading Berlin 1900. Harvard UP, 1998.

Gatti, Flora, and Fortuna Procentese. “Experiencing Urban Spaces and Social Meanings through Social Media: Unravelling the Relationships between Instagram City-related Use, Sense of Place, and Sense of Community.” Journal of Environmental Psychology, vol. 78, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101691

Gergen, Kenneth J. “The Challenge of Absent Presence.” Perpetual Contact: Mobile Communication, Private Talk, Public Performance, edited by James E. Katz and Mark A. Aakhus, Cambridge UP, 2002, pp. 227–41.

Gita. X direct message to the author. 29–31 Aug. 2024.

Gozzi, Raymond, Jr. “Absent Presence.” A Review of General Semantics, vol. 63, no. 1, 2006, pp. 82–85.

Haider, Sajjad. WhatsApp correspondence with the author. Jan.–Oct. 2024.

Hameed, Abdul, et al. “Sikh Bazar at Garhi Habibullah, Mansehra (Pakistan): History Architecture and Tourism Potential.” Pakistan Heritage, vol. 13, 2022, pp. 83–96.

Hammersley, Martyn, and Roger Gomm. Introduction. Case Study Method: Key Issues, Key Texts, edited by Roger Gomm, Martyn Hammersley, and Peter Foster, SAGE, 2000.

Hassan, Shiraz. “Birthplace of Reformist Movement a Picture of Neglect.” Dawn, 14 Sept. 2014, https://www.dawn.com/news/1131886, accessed 24 July 2025.

Jakobson, Roman. “On Linguistic Aspects of Translation.” On Translation, edited by Reuben Arthur Brower, Harvard UP, 1959, pp. 232–39. https://doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674731615.c18

Jatt, Zahida R. “Exploring Tourism Opportunities: Documentation of the Use of Spaces of the Pre- Partitioned Temples and Gurudwaras in Punjab, Pakistan.” Chitrolekha International Magazine on Art and Design, vol. 5, no. 2, 2015, pp. 59–73.

Jehangir, Javaid. “Audit Report on the Accounts of City District Government Rawalpindi, Audit Year 2017–18.” Auditor General of Pakistan, https://agp.gov.pk/SiteImage/Policy/16.%20Rawalpindi%20A.c-4%20AY%202017-18%20(03.02.18).pdf, accessed 24 July 2025.

Kermani, Secunder. “Kartarpur Corridor: A Road to Peace between India and Pakistan?” BBC, 29 Nov. 2018, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-46382657, accessed 24 July 2025.

Lee, Tong King. “Introduction: Thinking Cities through Translation.” The Routledge Handbook of Translation and the City, edited by Tong King Lee, Routledge, 2021, pp. 1–11. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429436468-1

Lookingbill, Andrew, and Ethan Russell. “Google Maps 101: How We Map the World.” The Keyword, 22 July 2019, https://blog.google/products/maps/google-maps-101-how-we-map-world/, accessed 24 July 2025.

Mahmood, Asif. “Renaming of Areas Perplexes Locals.” The Tribune, 20 May 2024, https://tribune.com.pk/story/2467489/renaming-of-areas-perplexes-locals, accessed 24 July 2025.

Noor, Aliza. “Displaced by Partition, She Visited Pakistan Home after 75 Years.” Al-Jazeera, 2022, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/8/13/displaced-by-partition-she-visited-pakistan-home-after-75-years, accessed 24 July 2025.

“Om.” Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Sanskrit-language, accessed 24 July 2025.

Otsuji, Emi, and Alastair Pennycook. “Interartefactual Translation: Metrolingualism and Resemiotization.” The Routledge Handbook of Translation and the City, edited by Tong King Lee, Routledge, 2021, pp. 59–76. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429436468-6

Pennycook, Alastair. Language Assemblages. Cambridge UP, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009348638

Razvi, Abbas. X direct message to the author. 29 Aug. 2024.

“Reena Verma from India Visits Her Ancestral Home in Pakistan after 75 Years.” YouTube, uploaded by BBC News, 21 July 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gij3U4-mF_E, accessed 24 July 2025.

“Reinscription.” Oxford Reference, https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803100412315, accessed 24 July 2025.

Remm, Tiit. “Textualities of the City—From the Legibility of Urban Space towards Social and Natural Others in Planning.” Sign Systems Studies, vol. 44, no. 1–2, 2016, pp. 34–52. https://doi.org/10.12697/SSS.2016.44.1-2.03

Schaflechner, Jürgen. Hinglaj Devi: Identity, Change, and Solidification at a Hindu Temple in Pakistan. Oxford UP, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190850524.001.0001

Shohamy, Elana, Eliezer Ben-Rafael, and Monica Barni. “Introduction: An Approach to an ‘Ordered Disorder.’” Linguistic Landscape in the City, edited by Elana Shohamy, Eliezer Ben-Rafael, and Monica Barni, Multilingual Matters, 2010, pp. xi–xxviii. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781847692993

Simon Sherry. “The Translational City.” The Routledge Handbook of Translation and the City edited by Tong King Lee, Routledge, 2021, pp. 15–25. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429436468-3

Simon, Sherry. “The Translational Life of Cities.” The Massachusetts Review, vol. 56, no. 3, 2015, pp. 404–15.

Spilioti, Tereza, and Korina Giaxoglou. “Translation and Trans-scripting: Languaging Practices in the City of Aθens.” The Routledge Handbook of Translation and the City, edited by Tong King Lee, Routledge, 2021, pp. 278–93. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429436468-21

Sywenky, Irene. “Imperial Translational Spaces and the Politics of Languages in Austria-Hungary: The Case of Lemberg/Lwów/Lviv.” The Routledge Handbook of Translation and the City, edited by Tong King Lee, Routledge, 2021, pp. 176–89. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429436468-14

Waksman, Shoshi, and Elana Shohamy. “Decorating the City of Tel Aviv-Jaffa for Its Centennial: Complementary Narratives via Linguistic Landscape.” Linguistic Landscape in the City, edited by Elana Shohamy, Eliezer Ben-Rafael, and Monica Barni, Multilingual Matters, 2010, pp. 57–73. https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.29308476.8

Yasin, Aamir. “Nirankari Gurdwara—Centre of Learning for over 50 Years.” Dawn, 30 Dec. 2024, https://www.dawn.com/news/1881845, accessed 24 July 2025.

Footnotes

- 1 I am extremely grateful to the special issue editors (Professor Simon and Dr. Majer), the reviewers, and the editorial staff for their help in steering and polishing my work.