Exploring Yaoundé as a Linguistically Divided Capital City of an English and French Bilingual African Nation

University of Yaoundé I

https://orcid.org/0009-0008-4505-6223

https://orcid.org/0009-0008-4505-6223

Abstract

This article examines the place of translation in the public space in Yaoundé, the capital city of Cameroon, an African nation with a threefold (German, English, and French) colonial heritage. The collected quantitative and qualitative data consisted of public space literature, i.e. outdoor advertising in the streets and other urban spaces where francophone and anglophone communities interact. Data analysis combined with the theory of translationality proposed by Sherry Simon in 2014 and 2021 revealed that Yaoundé is not a dynamic translation zone, because the translational activity in this urban space is minimal. Instead, Yaoundé is almost distinctively monolingual in French and English, and quasi-untranslated. This quasi-absence of translation-mediated contact between the communities makes Yaoundé a linguistically divided city, where French-speaking and English-speaking citizens live in juxtaposition and co-exist in relative isolation. This adversely impacts the traffic of information and opportunities across linguistic borders.

Keywords: translation, translationality, public space literature, Yaoundé, Cameroon.

INTRODUCTION

Yaoundé is the second largest city in Cameroon, a country in Central Africa that hosts about 279 indigenous languages (Eberhard, Simons, and Fennig). As the political capital city of the country, Yaoundé is the terminus of the centripetal mobility of speakers of most of those languages, and thus a highly multilingual city. Yaoundé is also a bilingual city. As a former mandated territory of Great Britain and France, Cameroon fits Cronin and Simon’s 2014 description of former imperial or colonial territories “where the imperial language was not evinced” (121). Indeed, after independence from France in 1960 and from Great Britain in 1961, respectively, East Cameroon and West Cameroon joined to form the Federal Republic of Cameroon in October 1961. The newborn Federal Republic selected English and French as official languages within the framework of its constitutionally enshrined official language bilingualism policy. Since then, English and French as official languages are not just the languages of the administration, but the dominant languages for public affairs in such spaces as parks, streets, sidewalks, footpaths, playgrounds of recreation, marketplaces, roadsides, school campuses, open spaces in hospitals, courts, to name only a few examples in urban areas. From the perspective of official language bilingualism, cities in Cameroon, especially Yaoundé, host French-speaking (francophones) and English-speaking (anglophones) citizens, whose contact zones naturally include the public space.

This article is a study of Yaoundé as a translational city as defined by Cronin and Simon, i.e. one where translation is “a key to understanding the cultural life of cities when it is used to map out movements across language, to reveal the passages created among communities at specific times” (119). I examine the use, organization, and importance of English and French in public space literature, defined here as any textual content written and posted or displayed outdoors in a public space for the consumption of the street user-cum-reader. It is the text found, among other places, on signboards, billboards, banners, walls, menu boards, storefronts, or shopfronts. Public space literature is used to inform public space users (informational content) or to sell to them (marketing content). I proceed from the following central question: is Yaoundé a translated city or an untranslated one? Other questions include: how are English and French used in public space literature in the translational bilingual Yaoundé? What is the dominant hierarchical or organizational pattern of their use, and what forces control it? To what extent is the contact between francophones and anglophones mediated and facilitated by translation? I argue that Yaoundé is essentially an untranslated bilingual city where francophone and anglophone citizens co-exist in relative isolation, at least in the public space, and where access to information and opportunities is controlled by the language one can read.

BACKGROUND

Cameroon has a unique historical relationship with translation, as is evidenced in this short account by Echu:

Historically, Cameroon was founded around 1472 by a Portuguese navigator, Fernando Po, who arrived at the Bight of Biafra and then sailed up the Wouri River in the Coastal region. The navigator was surprised to see shrimps in the river and baptized the river “Rio dos Camarões” (river of shrimps). This name, which was to be associated with the country, became “Kamerun” during the German colonial period and “Cameroon” or “Cameroun” during British and French colonial rule. (20)

Kamerun, a German protectorate from 1884 to 1916, spoke German, at least among the educated. When Germany was defeated during World War I, its protectorate was mandated by the League of Nations to France (80%) and Great Britain (20%). The new masters of the land erased German, replacing it with their languages.

Apart from the various translations of its name and the hegemony of English and French in the linguistic landscape, Cameroon—as already mentioned above—is home to about 279 indigenous languages (Eberhard, Simons, and Fennig). Pidgin English and Camfranglais, “a composite language consciously developed by secondary school pupils who have in common several linguistic codes, namely French, English, and a few widespread indigenous languages” (Kouega 23), are also spoken. When East Cameroon and West Cameroon formed a Federal Republic, English and French were not eradicated, but promoted as the Federal Republic’s official languages (Fonlon). They were enshrined in the Constitution and given equal status. As a result, translation instantly became a necessary tool for smooth collaboration in public administration. As I have noted elsewhere (Dassé 126), a translation bureau was created at the Presidency of the Federal Republic as early as 1962, and an advanced school of translators and interpreters was founded in 1985. The government also considered translation a tool for national unity and integration, as contacts between English-speaking and French-speaking Cameroonians were bound to increase outside the administrative environment.

Indeed, federalism and subsequent changes in the form of the State that led to today’s highly centralized Republic of Cameroon have accelerated, over decades, the mobility of anglophones into francophone regions, and conversely. Internal migration for economic and professional motives has led anglophones to settle in francophone regions and cities, and reciprocally. As a result, in addition to civil servants, ordinary individuals (the jobless, peddlers, businesspeople, and students) from both communities settle, live, and meet in cities of any scale across the country, according to an apparently immersive settlement pattern.

Indeed, in Yaoundé, as in most of the world’s cosmopolitan cities, settlement patterns follow ethnic, religious, linguistic, and economic lines. However, these lines are broadly dotted here, especially regarding indigenous languages in general and official languages in particular. There are neither airtight francophone nor anglophone enclaves, although there may be some spots of high concentration of anglophones in this predominantly francophone city. In about all the seven subdivisions of Yaoundé, francophones and anglophones live in the same buildings, use the same public facilities, and hawk at the same markets, to name a few examples. They come, go, sell in the same streets, and are exposed to the same literature in the public space.

One final aspect worth pointing out about Cameroon’s relationship to translation is conflict. In fact, the lack of translation into English of a legal instrument, the OHADA Uniform Act, prompted anglophone lawyers to start a strike action in 2016. Anglophone teachers soon joined the chorus, airing their bitterness over the perceived overintegration of French into the anglophone system of education. Before the government could translate the OHADA Uniform Act and find solutions to the other claims being raised, hitherto dormant anglophone secessionist groups had used the strike as a pretext to take control of the situation and start what is referred to as the anglophone crisis. This sociopolitical unrest has since wreaked havoc in the two anglophone regions of Cameroon, claiming the lives of thousands and displacing thousands more internally into francophone regions and externally into neighboring Nigeria.

Prior to the crisis, the social, cultural, and political relations between the two communities in Yaoundé were historically complex, typically marked by both integration and psychological tension. Broadly speaking, anglophones were well-integrated into the city, with many living in neighborhoods around the University of Yaoundé I and working as civil servants or businesspeople. Despite this integration, language barriers persisted, as French often dominated public services and public spaces, creating challenges and frustrations for anglophones. English was highly regarded among francophones as a growing number of francophone parents continued to send their children to anglophone schools—although more to reap the benefits attached to the status of English as an international language than to foster bilingualism and national unity (see Kiwoh). However, francophones continued to use sometimes derogatory terms to describe anglophones and looked down on them as second-class citizens. Anglophones in Yaoundé maintained a strong sense of cultural identity, preserving their languages and traditional practices, especially through many dynamic cultural associations. Overall, the relationship was multifaceted, with both generally positive interactions and underlying social and political divisions. The influx of internally displaced anglophones to Yaoundé due to the crisis does not seem to have impacted this pre-crisis relationship.

THEORETICAL CONSIDERATIONS AND LITERATURE REVIEW

Matt Valler attributes the introduction of the concept of translationality into translation studies to Douglas Robinson, Kobus Marais, and Piotr Blumczynski. According to Valler, “[t]ranslationality . . . might be the condition of the translational, of denoting that translation is present, that there is translation all around” (324). This approach to translationality is rather philosophical as it explores “what counts as translation” (ibid.), challenges the narrow yet common association of the word translation with interlinguistic meaning transfer, narrows down the word to its etymological definition (“carry across”), and then applies it to the study of change/transfer wherever it occurs.

Sherry Simon’s approach to translationality (see Cities in Translation and Translating Montreal), deployed in this paper, considers translation from a linguistic perspective, focusing on language relations in multilingual environments, especially the city. The approach is historical, archeological, and documentary in outlook as it examines how languages ebb and flow in multilingual spaces and sees translation as a movement, not just of meaning, but also of people as they engage in directional and interactional (self)translation (linguistic and physical) over time, in the face of political and societal dynamics. It explores how hierarchical relationships between languages in multilingual cities are built, maintained, and reversed through various forms of translational activities.

The concepts of “translational city,” “translation spaces/zones,” “self-translation,” and “translational activities/actions/events” are central to the Simon-championed strand of the translationality theory. Translational cities are de facto multilingual cities considered from the point of view of hierarchical relationships between the languages that are present or used to be present. They are translational in that they are platforms of translation-mediated linguistic transactions. Translation spaces or zones are where those transactions happen in the city. In the words of Cronin and Simon, translation spaces or zones “more specifically refer to the cultural and geographical spaces that give rise to intense language traffic” (121) in the city. They are “interzones, grey areas, which become home to mixed and polyglot communities” (ibid.) in multilingual cities divided along linguistic lines rooted in colonialism and immigration, for instance. Self-translation has a double meaning. Firstly, it consists of (a) using the language of the outgroup irrespective of the method: actual translation of one’s text from one’s language (source) to the outgroup’s language (target), (b) using the outgroup’s language when interacting/communicating with the outgroup, (c) writing in the outgroup’s language to the detriment of one’s language for sundry reasons, including voluntary and nonvoluntary economic, political, and ideological ones. Next, self-translation means the physical and the metaphorical/symbolic move across the physical, political, or ideological barriers that divide one’s linguistic community in the city to meet the outgroup community, still by suppressing one’s language. Finally, translational activity, event, or action happens in different forms, ranging from traditional translation (source text–target text) through “highly prominent and visible interpreting to everyday self-translation” (Koskinen 186). Montreal is one of those cities where such actions involve (self-)translation.

Simon documents Montreal’s journey from a city divided by languages—English and French—that “has been dominated by the spectre of separateness, and defined by efforts to respect or transgress the boundary between anglophone West and francophone East” (Translating Montreal 4) to a “now mixed and cosmopolitan Montreal” (5). She shows how a mix of forms of formal and informal translation and self-translation—linguistic identity shift—that started in contact zones where mixing led to both identity troubles and identity blurring as solid linguistic lines gradually dotted and faded into a mélange of linguistic and cultural identities. These identities now contrast with “the politically charged sixties and seventies” when “Montreal’s Anglos were the historic enemies” (xiv) of Montreal francophones.

In Cities in Translation, Simon extends her 2006 study to other linguistically divided cities like Kolkata (formerly Calcutta) in India, Habsburg Trieste in Italy, and Barcelona in Spain, where competing languages co-exist(ed). In these translational cities, as in Montreal, translation and translators in what she calls “puntos suspendidos” (Cities in Translation 1), that is, translation zones, are presented as the kinetic force that drives communication and cultural traffic between the parts of the cities divided along the colonialism-induced geographical, cultural, economic, ethnic, and linguistic lines. In Kolkata, translation from English, the colonial language, into Bengali gave impetus to the latter and contributed to closing the gaps between Europeans and Indians. In Habsburg Trieste, a city “linguistically divided into an Italian zone and German-speaking Austrian zone” (Cariola 119), literary translation from German—the language of prestige—into Italian mediated the connections and cultural transfers between the linguistic and cultural communities. In Barcelona, Spanish and Catalan entertain a relationship marked by “friction and complicity” (Simon, Cities in Translation 90) against the backdrop of the historical political conflict between the Catalonia region and Spain. While there is no geographical separation between Catalan speakers and Spanish speakers in the city, (one way) traffic from Catalan—the language that claims ownership over the city and fights to regain control over its native territory—into Spanish does not happen in grey zones, but through self-translation and language neutralization. Self-translation is typically observed amongst Catalan authors who think in Catalan, their language of lived experiences, but write in Spanish.

Other cities studied using the translationality theory include Antwerp in Belgium (Meylaerts and Gonne), Lviv in Ukraine (Sywenky), Pera in Istanbul, Turkey (Demirkol Ertürk and Paker), and Tampere in Finland (Koskinen). Meylaerts and Gonne explore the role of translators as cultural mediators in Antwerp, a highly polyglot city “during the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century,” where “life . . . was profoundly marked by the encounter of Dutch and French and by translation and transfer processes in all possible forms” (135). They focus on two translators-cum-cultural mediators, exploring how they navigated and experienced the transition of Antwerp from a French-Dutch bilingual city to today’s Dutch monolingual city. Sywenky’s study focuses on the role of translators as interpreters of Lviv, a city formerly controlled by Poles, Habsburgs, and Russians. She demonstrates the role of translation and translators in peeling off the successive linguistic layers deposited by the various foreign occupants to better understand the city’s past, present, and future. Demirkol Ertürk and Paker account for the emergence of Pera as a translational city following the reappearance of Kurdish and Armenian after they were suppressed under Kemal Atatürk’s all-Turkish policies. The return of translational activities in the city under the impetus of publishers and translators bears testimony to the reconstruction of the lost multilingual fabric of Istanbul. Koskinen’s study of the Finnish municipality of Tampere as a translation space examines the “historical trajectories of translationality” (186). She concludes that during the period of interest (1809–1917), there was “a sense of parallel existence of languages and mutual accommodation to the linguistic needs of a multilingual community, even in the face of conflicting interests and changing power relations” (ibid.).

Apart from the works reviewed above, many non-translation-oriented multilingualism studies explore language and/or societal issues, focusing on linguistic landscapes. Indeed, since the first decade of the 21st century, public space literature has received appropriate scholarly attention within the framework of linguistic landscape studies. Prominent among the latter are The Oxford Handbook of Language and Society (2016) and The Bloomsbury Handbook of Linguistic Landscapes (2024). In the former, Van Mensel, Vandenbroucke, and Blackwood argue that “the study of the linguistic landscape focuses on the visual representations of language(s) in the public space” (423) Further, they propose the following more explicit definition by Landry and Bourhis: “The language of public road signs, advertising billboards, street names, place names, commercial shop signs, and public signs on government buildings combines to form the linguistic landscape of a given territory, region, or urban agglomeration” (424).

Finally, let me acknowledge five previous studies on urban space literature in Cameroon, namely those by Daniel Anicet Noah Mbede, Venant Eloundou Eloundou, George Echu and Terence Kiwoh, Martin Pütz, and Angéline Djoum Nkwescheu. The first two researchers study the “écrits dans la ville” (writings in the city) and “scripturalité automobile” (texts on automobiles), that is, very short proverbs or thank-you messages written on their taxis by drivers whom Noah Mbede calls “taxis-philosophes” (15). While these studies, grounded in semiostylistics and socio-pragmatics, are not translation-oriented, they point out that the messages on taxis are written in English, French, Cameroon Pidgin English, and even indigenous languages. Each taxi driver writes in the language of their choice. As for Echu and Kiwoh’s examination of the public linguistic landscape in Cameroon, their focus is on the languages of signage. Their results show that French and English dominate the nearly 300 indigenous languages in the landscape. While Pütz’s study shares similarities with that of Echu and Kiwoh, it specifically examines how the frequency and visibility of English and French on public signage reflect and reinforce the ideological conflict between the anglophone minority and the francophone government, highlighting the dominance of French and the marginalization of English in Cameroon’s linguistic landscape.

The last and most relevant study is that of Angéline Djoum Nkwescheu, who studied the language of advertisement in the neighborhoods around the University of Yaoundé I. Her examination of the “plethora of in vivo written productions . . . reveals the pre-eminence of French-English and English-French transcodic markers” (347). Most importantly, both languages appear to coexist peacefully and harmoniously, sharing both physical and symbolic spaces. For example, small notices in French are often posted alongside larger English signs on storefronts owned by anglophones, and the reverse is also true. Sometimes, anglophone business owners incorporate French words and expressions into their signage, while some francophones opt for entirely English displays. This mutual presence highlights the fluid and collaborative use of language in public spaces. Djoum Nkwescheu calls this self-translation phenomenon “total fusion to or assimilation with English” and argues that it is motivated by “linguistic opportunism” (369). In my study, I am interested in the same data type, but from a translation-oriented perspective. I shall highlight more areas of similarity and difference in the discussion of results.

METHODOLOGY

Data for this study was collected in the Yaoundé VI subdivision, one of the seven subdivisions of Yaoundé. Yaoundé VI sits on 22,200 square meters and is the third most populated subdivision, with about 300,000 inhabitants across 14 neighborhoods. As already pointed out, the settlement of anglophones in Yaoundé follows a somewhat immersive pattern. There is no subdivision/neighborhood for anglophones and no subdivision/neighborhood for francophones in the city. However, anglophones tend to be highly represented in some subdivisions and neighborhoods. Although no statistics are available, it can be inferred from experience that Yaoundé VI and the new neighborhoods in the outskirts of this subdivision harbor most of the anglophone community members in Yaoundé—up to 20,000, i.e. 6.66% of the subdivision’s population. As the city’s most representative potential translation zone, Yaoundé VI was selected as a study site.

Data was collected on 24.5 kilometers along eight major streets, as follows:

| No. | Itinerary name | Distance in kilometers |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Etok Koss—Entrée Simbock | 2 |

| 2 | Entrée Simbock—Carrefour Jouvence | 1.5 |

| 3 | Carrefour Jouvence—Carrefour TKC | 3 |

| 4 | Carrefour TKC—Entrée Simbock | 0.5 |

| 5 | Carrefour TKC—Parc Zoologique | 5 |

| 6 | Carrefour Jouvence—Lycée Biyem-Assi | 4 |

| 7 | Carrefour Jouvence—Shell Nsimeyong | 3.5 |

| 8 | Shell Nsimeyong—GP Obili | 5 |

| Total | 24.5 | |

For collection, we walked along the above-listed major streets, seeking all forms of outdoor advertisement signs and non-advertisement banners. The economy in Yaoundé VI is essentially informal. On the one hand, thousands of tiny physical shops (e.g., beauty, electronics, hardware, laundry, or dresses), convenience stores, bars, restaurants, schools, financial services providers, health service centers (clinics), petrol stations and similar establishments operate here and use advertising abundantly. On the other hand, thousands of individuals who have services to sell (e.g., home-delivered evening classes or plumbing) also advertise and post on the street. As a result, the streets are covered with illegal advertisement literature written on sheets of paper or metal, pieces of cardboard or plywood, on the ground, on the walls, on utility poles or on buildings, and with legal advertisements on small to jumbo-size signboards and billboards. We calculated that there is, on average, one advertisement per meter; in other words, we found public space literature to be very abundant (Fig. 1).

We counted legal and illegal advertisements on both sides of the streets and took pictures of some for illustration. We counted as many as 13,860 advertisements and reduced the number by 21% because some were repeated up to 21 times. Therefore, a total of 11,184 advertisements were retained for analysis.

DATA PRESENTATION AND ANALYSIS

The collected advertisements were classified into three categories: (1) French-monolingual/English-monolingual, (2) bilingual, and (3) pseudo-bilingual and bilingual with loss in translation. We also considered the spatial cohabitation of monolingual advertisements.

MONOLINGUAL ADVERTISEMENTS IN FRENCH AND ENGLISH

French-monolingual and English-monolingual advertisements were the dominant variety. We also considered monolingual advertisements on two-sided signs (Table 2):

| French- Monolingual | English- Monolingual | French two-sided | English two-sided | Total French | Total English | Grand Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8,702 | 800 | 801 | 59 | 9,503 | 859 | 10,362 |

The above statistics show that 10,362 out of 11,184 advertisements (92.65%) in Yaoundé VI were monolingual in French or English. Thus, French claimed the lion’s share with 9,503 out of 10,362 (91.71%). Only 859 in English were spotted, representing 8.29% of all the monolingual advertisements in the subdivision. Such advertisements were explicitly used to inform about businesses, services, and products relevant to francophones and anglophones. For instance, the signage of all the 22 petrol stations in the subdivision was in French.

Similarly, the signage of most banks, the names of microfinance businesses, and the banking products which they offered were either in French or English, depending on the community from which the owner hailed. The signage of hospitals, private clinics, restaurants, cosmetics and beauty shops, hotels, drugstores, and schools was monolingual in French (dominantly) or English. Advertisements about job opportunities, houses to let, and baby food, among other examples, were also in French or English only, as exemplified in Fig. 2:

The lack of space to fit two languages did not explain the choice to stick to monolingual advertisements. Noticeably, even with ample space, most businesses and organizations chose to remain monolingual. For instance, 860 signs (801 in French, 59 in English) were two-sided, presenting an irrefutable opportunity for translation. The Breast Cancer Awareness Month banner in Fig. 3 below is a case in point: the side presented here is identical in content and language to the other side. Some businesses with three to five signboards, including two-sided ones, remained monolingual in French or English.

Monolingual advertisements targeted one community and ignored the other. Consequently, only bilinguals and community members of the language used would be informed of the advertised opportunities and would benefit from them. In the case of Fig. 3 above, monolingual anglophones would not be aware of the breast cancer screening opportunity which the advertiser was offering during Pink October.

BILINGUAL ADVERTISEMENTS

We classified as fully bilingual all advertisements with the same amount of information in each language (Table 3):

| Bilingual one-sided | Bilingual two-sided | Total | % all advertisements |

|---|---|---|---|

| 126 | 83 | 209 | 1.86 |

Table 3 shows that only 209, i.e. 1.86% of all the 11,184 advertisements considered, were fully bilingual. 126 were one-sided, and 83 were two-sided. Sign size did not seem to limit the will of advertisers to communicate in both languages. We found one-sided bilingual advertisements as small as 625 square centimeters. As with monolingual advertisements, bilingual ones informed about businesses, products, and services relevant to all city dwellers, irrespective of their official language.

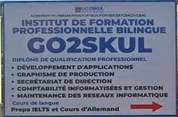

Unlike monolingual ones, bilingual advertisements made information and opportunities universally available and appealed to francophone and anglophone community members alike. In the case of Fig. 4 below, the use of English and French on this two-sided signboard ensured that both linguistic communities were informed of the learning opportunities offered by the school.

PSEUDO-BILINGUAL ADVERTISEMENTS AND ADVERTISEMENTS WITH LOSS IN TRANSLATION

Under the mass-media and social-media influence of American culture, many francophones in Yaoundé tend to give English names to their businesses (Djoum Nkwescheu 369). As a result, their advertisements look bilingual at first sight, but are in fact monolingual, because only the names of their businesses are in English. This phenomenon in advertisements, which I term pseudo-bilingualism here, was already observed by Kasanga in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) between French and English, and by Androutsopoulos in Germany, between German and English. Examples are provided in Table 4 and Fig. 5 below.

| No. | Name in English | Details in French |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Holiday’s Restaurant | Salon de thé—Cave—Grillades—Prestation de services (location couvert, service traiteurs, décoration)—Livraison à domicile et au bureau |

| 2 | Proactive Pressing | Perfection, Priorité, Ponctualité—Services: lavage à sec, blanchisserie, ramassage, lavage artisanal, lavage en kilo, livraison à domicile |

| 3 | Exten’s Beauty | Parfumerie—Cosmétique—Extensions de cheveux naturels et gaufrés—Accessoires de beauté |

I counted 377 pseudo-bilingual advertisements with English-looking names and French descriptions, and found none with a French name and English descriptions. Again, the use of English in business names by francophones fulfills the same functions which Kasanga attributed to English in his study in the DRC, namely that of “identity enhancing, ornamentation, brand-name keeping” (197). It is not a form of (self)translation as it does not signal a move to target anglophones in Yaoundé. Similarly, the absence of pseudo-bilingual advertisements with French-induced names and English descriptions indicates the slight influence of French and francophones on anglophones in Yaoundé.

Other types of advertisements needed further translation. Generally, translation in such advertisements was limited to part of the content, the other part being lost in translation. I found 27 such partially translated advertisements. As we can see in the first image of Fig. 6 below, only the name of the church is translated into English. In the second image, only “Laptop included,” “Free WIFI 24/7,” “Internships Guaranteed,” and “Travel to Canada” are translated into French, while the remaining content (about 90%) is in English only.

SPATIAL COHABITATION

As regards the spatial distribution of all the preceding types of advertisements in the study area, it was observed the monolingual ones in French or English were glued or nailed next to one another on the same utility poles, walls, signboards, and billboards. Fig. 7 below shows two French monolingual advertisements that cohabit with one English monolingual advertisement on utility poles.

DISCUSSION OF THE RESULTS

Data analysis revealed that 9,503 advertisements in Yaoundé VI were monolingual in French, while 859 were monolingual in English. Monolingual advertisements amounted to 92.65% of all the public space literature identified in this subdivision.

On the one hand, the sweeping majority of monolingual signage in French matched the fact that Yaoundé is the colonial niche of French and that francophones are by far the majority linguistic community in the city. In her previously mentioned study of advertisements in neighborhoods around the University of Yaoundé I, Djoum Nkwescheu opined that “le pragmatisme linguistique voudrait que l’on vise le plus large public en communiquant dans la langue dominée par la majorité” (356). In other words, linguistic pragmatism accounted for the tendency of advertisers to favor French over English as they preferred to target a larger audience by communicating in the language of the majority. The magnitude of this choice signaled the generalized absence of translational activity among francophones. They expected anglophones to (self-)translate to join them rather than make French content accessible to anglophones through English translation. Apart from linguistic pragmatism, the unwillingness to incur the costs associated with translation and production of bilingual signage could also explain the tendency to skip translation into English.

On the other hand, the small number of advertisements in English could be correlated to the fact that Yaoundé is not the colonial niche of English and that anglophones are the minority linguistic group in the city. However, anglophone advertisers’ dominant (859) use of advertisements that are monolingual in English also pointed to a minimal translational activity within that community. Linguistic pragmatism did not seem to be valid here. Indeed, while anglophones were often expected to (self-)translate in order to tap into the vast pool of francophone prospects, they chose to remain in their linguistic enclave by targeting solely English-speaking prospects.

Fully bilingual, pseudo-bilingual, and loss-in-translation advertisements accounted for a mere 7.35% of all the 11,184 advertisements retained for analysis. This low percentage of instances where French and English met on the same signboards to communicate the same messages, even partially, indicated that inter-community communication mediated by professional translators and self-translators was minimal. In other words, the absence of spatial segregation (see Fig. 7 above; Djoum Nkwescheu 353–57) between French and English advertisements gave a deceptive impression about the contact between both languages and linguistic communities.

Indeed, unlike in Simon’s Montreal, where Anne Carson could imagine that she might “automatically move her eyes to the left-hand page when puzzled by some expression” (Cities in Translation xv), French and English advertisements do meet on the same signboards, utility poles, or walls in Yaoundé VI, but to tell different stories. Strictly from the perspective of written urban literature, Yaoundé VI is more of a juxtaposition zone than a contact zone, more of a bilingual zone than a translation zone. In the light of this study, it is a juxtaposition zone where francophones and anglophones mingle on the streets, live in the same building, work in the same offices, and yet live linguistically separate lives: they practice linguistic segregation. As Abbas would say, they “see each other every day and yet ‘move in different worlds’” (qtd. in Simon, Cities in Translation 22). Thus, Yaoundé VI is only a contact/translation zone for the handful of bilinguals who crisscross the communities and have access to all the information and opportunities posted in the urban space. However, this linguistic separation in signage does not mean that francophones and anglophones in Yaoundé VI exist in isolation. As I pointed out in the introduction, there are strong frequent interactions, shared workplaces, intermarriages, and family ties—often shaped by urban migration and educational experiences—that foster meaningful social and verbal exchanges across language communities.

CONCLUSION

In this article I examined the place of translation in the public space of Yaoundé. Generalizable results from data collected in Yaoundé VI showed that the city is almost distinctively monolingual in French and English, and therefore is (quasi-)untranslated. On the one hand, urban space literature in French dominates the landscape as the language is in its colonial niche and is spoken by the overwhelming majority of the city’s inhabitants. The francophone community largely ignores English and anglophones in their signage, making little effort to self-translate or to seek the help of mediators (i.e. professional translators) to make their public space literature available in English. On the other hand, urban literature in English tends to be dominant among anglophones, who also hardly self-translate or seek mediation to appeal to francophones. As a result, the urban space in Yaoundé is linguistically divided: information and ideas flow in separate linguistic channels, with little translation-mediated contact. Anglophone and francophone groups of citizens live in juxtaposition and co-exist in relative isolation, at least in the public space, where the traffic of information and opportunities is regulated by the language that one can read. Despite their juxtaposition and isolation in public space literature, both communities share strong social bonds through workplace interactions, intermarriages, family ties, and educational experiences.

Authors

Works Cited

Androutsopoulos, Jannis. “English on Top: Discourse Functions of English Resources in the German Mediascape.” Sociolinguistic Studies, vol. 6, no 2, 2012, pp. 209–38. https://doi.org/10.1558/sols.v6i2.209

Blackwood, Robert, Stefania Tufi, and Will Amos, editors. The Bloomsbury Handbook of Linguistic Landscapes. Bloomsbury, 2024. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350272545

Blumczynski, Piotr. Experiencing Translationality: Material and Metaphorical Journeys. Routledge, 2023. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003382201

Cariola, Laura Annamaria. Review of Cities in Translation, by Sherry Simon. Critical Discourse Studies, vol. 12, no. 1, 2014, pp. 118–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2014.938852

Cronin, Michael, and Sherry Simon. “Introduction: The City as Translation Zone.” Translation Studies, vol. 7, no 2, 2014, pp. 119–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/14781700.2014.897641

Dassé, Théodore. “Official Language Bilingualism, Patriotism, and National Unity in Cameroon.” Le bilinguisme officiel au Cameroun, évolution actuelle et dynamique/Official Language Bilingualism in Cameroon: Current Insights and Dynamics, edited by George Echu, L’Harmattan, 2023, pp. 123–50.

Demirkol Ertürk, Şule, and Saliha Paker. “Beyoğlu/Pera as a Translating Site in Istanbul.” Translation Studies, vol. 7, no. 2, 2014, pp. 170–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/14781700.2013.874538

Djoum Nkwescheu, Angéline. “Les écrits urbains colinguistiques spontanés camerounais, révélateurs de la trajectoire multisituée des relations exogroupales des quartiers universitaires de Yaoundé I.” Le bilinguisme official au Cameroun, évolution actuelle et dynamique/Official Language Bilingualism in Cameroon: Current Insights and Dynamics, edited by George Echu, L’Harmattan, 2023, pp. 344–74.

Eberhard, David, Gary Simons, and Charles Fennig. Ethnologue: Languages of the World. Twenty-Fifth Edition. SIL International, 2022.

Echu, George. “The Language Question in Cameroon.” Linguistik online, vol. 18, no. 1, 2004, pp. 19–33. https://doi.org/10.13092/lo.18.765

Echu, George, and Nsai Terence Kiwoh. “Evolution of the Public Linguistic Landscape in Cameroon Fifty Years after Reunification.” Cinquante ans de bilinguisme officiel au Cameroun (1691–2011), edited by George Echu and Augustin Emmanuel Ebongue, L’Harmattan, 2012, pp. 21–41.

Eloundou Eloundou, Venant. “Scripturalité automobile à Yaoundé et altérité sociale.” Le français en Afrique, no. 30, 2016, pp. 41–56.

Fonlon, Bernard. “A Case for Early Bilingualism.” ABBIA, no 4, 1963, pp. 56–94.

Kasanga, Luanga Adrien. “Streetwise English and French Advertising in Multilingual DR Congo: Symbolism, Modernity, and Cosmopolitan Identity.” International Journal of the Sociology of Language, vol. 206, 2010, pp. 181–205. https://doi.org/10.1515/ijsl.2010.053

Kiwoh, Nsai Terence. “Official Language Bilingualism and Language Management in Cameroon.” 2010. University of Yaoundé I, unpublished PhD dissertation.

Koskinen, Kaisa. “Tampere as a Translation Space.” Translation Studies, vol. 7, no. 2, 2014, pp. 186–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/14781700.2013.873876

Kouega, Jean-Paul. “Camfranglais: A Novel Slang in Cameroon Schools.” English Today, vol. 19, no. 2, 2003, pp. 23–29. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266078403002050

Landry, Rodrigue, and Richard Bourhis. “Linguistic Landscape and Ethnolinguistic Vitality: An Empirical Study.” Journal of Language and Social Psychology, vol. 16, no. 1, 1997, pp. 23–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X970161002

Marais, Kobus, editor. Translation beyond Translation Studies. Bloomsbury, 2022. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350192140

Meylaerts, Reine, and Maud Gonne. “Transferring the City—Transgressing Borders: Cultural Mediators in Antwerp (1850–1930).” Translation Studies, vol. 7, no. 2, 2014, pp. 133–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/14781700.2013.869184

Noah Mbede, Daniel Anicet. Écrits dans la ville: l’imaginaire politique des Camerounais à travers les messages inscrits sur les taxis et les motos-taxi. Editions CLE, 2010.

Pütz, Martin. “Exploring the Linguistic Landscape of Cameroon: Reflections on Language Policy and Ideology.” Russian Journal of Linguistics, vol. 24, no. 2, 2020, pp. 294–324. https://doi.org/10.22363/2687-0088-2020-24-2-294-324

Robinson, Douglas. Translationality: Essays in the Translational Medical Humanities. Routledge, 2017. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315191034

Simon, Sherry. Cities in Translation: Intersections of Language and Memory. Routledge, 2012.

Simon, Sherry. “The Translational City.” The Routledge Handbook of Translation and the City, edited by Tong King Lee, Routledge, 2021, pp. 1–13. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429436468-3

Simon, Sherry. Translating Montreal: Episodes in the Life of a Divided City. McGill-Queen’s UP, 2006. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780773577022

Sywenky, Irene. “(Re)Constructing the Urban Palimpsest of Lemberg/Lwów/Lviv: A Case Study in the Politics of Cultural Translation in East Central Europe.” Translation Studies, vol. 7, no. 2, 2014, pp. 152–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/14781700.2014.882793

Valler, Matt. “Translationality: A Transformational Concept for Translation Studies?” Translation and Interpreting Studies, vol. 19, no. 2, 2024, pp. 323–33. https://doi.org/10.1075/tis.00057.val

Van Mensel, Luk, Mieke Vandenbroucke, and Robert Blackwood. “Linguistic Landscapes.” The Oxford Handbook of Language and Society, edited by Ofelia García, Nelson Flores, and Massimiliano Spotti, Oxford UP, 1996, pp. 423–49.