Majorca as a Translational Space: Creating and Questioning Identity through Translation

University of Exeter

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5281-8435

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5281-8435

Abstract

Majorca offers a rare combination of opportunities to develop a study of translation and space. Not only is it a site of rich historical cultural contact, but it is also a present location of contact and tension: between Spanish and Catalan; between distinct forms of Catalan; with the languages spoken by significant economic migrant populations and expatriate communities, and languages represented by large tourist populations. Processes of layering, replacement, addition, and effacement of cultural forms are evident throughout the island, to the point that translation is a condition for creating Majorca’s own cultural identity.

In this article I shall develop Sherry Simon’s search for translation in the urban environment to identify and analyse translational markers on the Mediterranean island of Majorca and its capital Palma, and seek their effects on the island’s communities as well as their sense of identity. I thereby propose “strong” forms of translation to complement the “weak” forms sketched by Simon. These strong forms result from cultural contact to ensure a deeper understanding of cultural identity, and empathy between cultures in our increasingly interconnected world.

Keywords: translational spaces, Majorcan culture, Catalan language and culture, post-translational effects, cultural identity.

INTRODUCTION

In this article, I shall analyse how translation works as a creative force in building and challenging narratives of identity on the Mediterranean island of Majorca, and especially its capital city, Palma. To achieve this, the article will draw on concepts from the emerging field of post-translation studies (Nergaard and Arduini; Gentzler), focusing not on translation as a transaction between cultures, but rather on how translation affects the space around it, transforming individuals and creating cultures. Thus, the object of study is not limited to translations as representations of texts from another language or culture, but rather offers an enlarged view of translation as the resolution to what Sherry Simon terms linguistic and cultural “tension, interaction, rivalry, or convergence” (Introduction 5). In this framework, translational places are those “whose cultural meanings are shaped by language traffic and by the clash of memories” (Simon, Translation Sites 2), and thus linguistic and cultural contact is an intrinsic part of these places’ cultural identity. An aim of this article is not only to show that Majorca is such a place, but to identify the effects of this condition on the people and culture of the island: not just in terms of the “weak” forms of translation that reflect “an active lack of engagement and empathy” (66), but also strong forms that can help to recover and strengthen cultural identity, and ensure empathy between cultures in our increasingly interconnected world.

CONTEXT AND METHOD

Through an extensive list of references, Vidal Claramonte charts the path of scholarly engagement with space from the second half of the 20th century onwards, across philosophy, cultural geography, ideology, health, ethics, and more (26–27). This includes sociology, and the field of linguistic landscapes, “written textual forms as displayed on shop windows, commercial signs, official notes, traffic signs, public signs on government buildings” (32). Indeed, the object of the present study bears many similarities to the study of linguistic landscapes, a field that has developed in parallel to what could be termed a “spatial turn” in translation studies. Yet, like Simon and Vidal Claramonte, I am concerned with beginning to identify the consequences of “reading a city-text in one language or another” (ibid.) where these are “written either in the submerged languages of the past or in the rival languages of the present” (Simon, Introduction 5); I am also interested in how these identities compete. Secondly, I aim (1) to identify the ways in which translation is used and at work in the city/island and the tensions between the distinct forms, and (2) to identify textual relationships in space, and the ways in which these, too, contribute to identity. Although my procedure is rooted primarily in translation studies, it looks outwards, toward other disciplines. Therefore, this study focuses on the type of process used to present multiple languages and languaged forms, the relationships between these forms, and reads competing forms as translations. In focusing on these processes and relationships, I aim to link this to the wider field of translation, and locate it as a constitutive act of creation. Importantly, in this study I aim to go beyond examples visible in the city, to assess how the same themes and spaces are explored in the city’s literary representations.

Majorca offers a rare combination of opportunities to develop this approach. There is a long history of linguistic and cultural contact on the island. As well as evidence of Roman and pre-Roman populations, there are significant physical remains from centuries of Moorish control (902–1229); James I of Aragon conquered the islands in 1229, bringing Christianity and the Catalan language, and the establishment of the Kingdom of Majorca; this came under the control of the Crown of Aragon in 1344; dynastic union between Castile and Aragon in 1479 and defeat in the War of the Spanish Succession (1701–14) led to the abolition of Majorca’s institutions and imposition of Spanish as the sole language of official use. Catalan language and culture underwent a Romantic revival in the 19th century, when Majorca also hosted European aristocrats and international artists, composers, and writers. Progress towards linguistic and cultural normalisation in the 20th century was brutally interrupted as Spain lurched between democracy and dictatorship, resulting in a fratricidal civil war (1936–39). With the death of the dictator General Francisco Franco in 1975, and the eventual transition to democracy, Catalan could work towards gaining official status alongside Spanish; only then could the Francoist slogan—“[o]ne, great and free” Spain—be challenged.

Currently, Majorca has two co-official languages: Spanish, identified as the official language of the state in the 1978 constitution, and Catalan, first recognised as co-official on the island in the 1983 Statute of Autonomy of the Balearic Islands. Yet there is potential for further tension: the latter law identifies Catalan as the islands’ “llengua pròpia” (own language),[1] but also recognises the “modalitats insulars” (islands’ own forms) of the language. Historically, this situation has led to tension with other forms of Catalan, as well as between Catalan and Spanish themselves. There are also significant tourist and expatriate communities on the island (most notably British and German), and migrant communities from South America as well as North and West Africa make up a greater percentage of the population than elsewhere in Spain, offering a wide variety of distinct relationships between languages and their speakers.

In recent years, the attempted independence referendum in the autonomous community of Catalonia (1 October 2017) and its fallout brought reflections on Catalan cultural identity to the wider Spanish and international stage. As a result, languaged cultural symbols—those “associated with specific tongues at the time of their construction or through subsequent layerings of meaning and memory” (Simon, Translation Sites 32)—have taken on new meanings and connotations. At the same time, in the Balearic Islands and Valencia (which also has Spanish and Catalan as co-official languages, although the latter is known there as “Valencian”), the May 2023 regional elections led to governing pacts between the Spanish nationalist right-wing Partido Popular and the far-right VOX, with policies attacking the presence, status, and unity of the Catalan language and culture being enacted.

Contact between these multiple (and competing) identities provides the potential for a much more wide-ranging study of how processes of translation function across the island and the wider Catalan-speaking territories. Here, I shall focus on four specific linguistic modalities (Catalan, Majorcan dialect, Spanish, and English) and how these interact in three distinct fields: firstly, toponyms, and more precisely the visible signage in the urban space; secondly, graffiti and stickers related to the anti-tourism movement and similar concerns; thirdly, the recovery of the island’s democratic memory, and how this is enacted in a case study of selected sites of memory. The aim is to observe and gather evidence of translational markers: where multiple languages or connected cultural forms are used, or where one has replaced another (and whether any remnants of the past can be found, or are recreated through translation). This means looking for instances where languages or connected cultural forms are in contact or compete in space (multilingual labels and signs, monolingual instances of languages in close proximity to each other, competing names for a place, the use of symbols connected to cultural identity), as well as exploring responses to such conflict.

The sites themselves were visited during three periods of intensive fieldwork (June 2023, September 2023, and January 2024). Candidate sites were identified in advance, following the five types proposed by Simon in Translation Sites: sites of the architecture of memory,[2] transit sites,[3] crossroads,[4] thresholds,[5] and border sites.[6] These places and surrounding areas were explored on foot and by bicycle, with photographic evidence taken, and the sites were revisited during each occasion to chart changes over time. This resulted in 1433 images,[7] tagged for location and time; these were then analysed and ordered according to the type of site and initial classifications of the type of translational process at work.

THREE CITIES IN ONE

The translational identity of Palma is evident even in its name: or, indeed, names, since multiple options compete. Should the visitor call it Palma de Mallorca, as stated in metres-high lettering on the roof of the island’s airport (see Fig. 1)?

Or is it Palma, as seen in the publicly funded promotional campaigns for the city (see Fig. 2)?

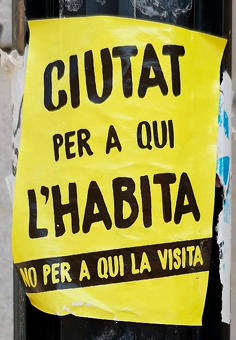

Or is it a name that the average visitor will likely not encounter, although it is used in many Majorcans’ vernacular—Ciutat (see Fig. 3)?

4 January 2024. Courtesy of the author.

12 September 2023. Courtesy of the author.

The city’s official name has been Palma since 2016, but the alternative Palma de Mallorca was official in the periods of 1983–88, 2006–08, and 2012–16. It is also commonly referred to as Ciutat, using the Catalan word for “city” as a toponym—it is not used with the definite article, is written with a capital letter, and is “[e]l nom real i tradicional . . . De fet encara ho és” (“the real and traditional name . . . In fact it still is”) (Coromines 142). Yet this is not a case of names changing over time; rather, they indicate conflict between linguistic and cultural identities. Ciutat uses a Catalan word, and its phonology and morphology stand out as not Spanish (/s/ rather than /θ/ for the initial “c,” and neither the phoneme /t/ nor the grapheme “t” in final position are possible in Spanish). Palma was the name reinstated following the Bourbon victory in the War of the Spanish Succession, reviving the name of the Roman settlement founded on the same site. In between these is the compound name Palma de Mallorca. The three periods when this was decreed as official coincide with regional governments led by the Spanish nationalist, right-wing Partido Popular (Popular Party).[9] The name has been considered by sociolinguists as “postís i innecessari, ja que dins els Països Catalans Palma és un nom inconfusible” (“artificial and unnecessary, since within the Catalan-speaking territories Palma is a name that cannot be confused”) (Bibiloni 30), and in 2011 the Department of Catalan Philology at the University of the Balearic Islands classed it as “inadmissible” (“unacceptable”) (Galán). Thus, Palma de Mallorca is seen very much as a name associated with the Spanish language (as opposed to Palma or Ciutat), and aligned with Spanish national identity. This can also be seen in the fact that in Fig. 1 above the name uses the Spanish “Aeropuerto” and not the Catalan “Aeroport.” This association with Spanish (not Catalan) sometimes extends to Palma, too, as seen in a 1979 case recounted by Bibiloni:

Fa pocs dies hem vist a la façana d’un teatre dos grans cartels anunciant uns actes patrocinats per l’Ajuntament, un en espanyol i l’altre en català; el primer era encapçalat per Ayuntamiento de Palma, el segon deia “Ajuntament de Ciutat.” (Bibiloni 26)

(A few days ago, I saw on the façade of a theatre two large posters advertising shows supported by the city council, one in Spanish and the other in Catalan; the former said at the top Palma City Council [in Spanish], and the latter Ciutat City Council [in Catalan].)

This multiplicity of names and their association with identities is not limited to the city. There are other instances of toponymical conflict and potential effects across the island (see Fig. 4):

On this sign at the entrance to the town of Port de Pollença, on the north of the island, the c with a cedilla—a distinctive marker of Catalan versus Spanish—is even highlighted, and the welcome in five languages indicates that this is a principal destination for tourists. Yet multiplicity is indicated by the URL below, pollensa.com, using the Spanish spelling (and by extension associating Spanish, as opposed to Catalan, with technology and modernity).

CONFLICT ON THE STREETS

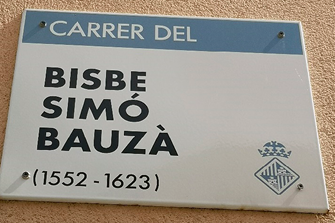

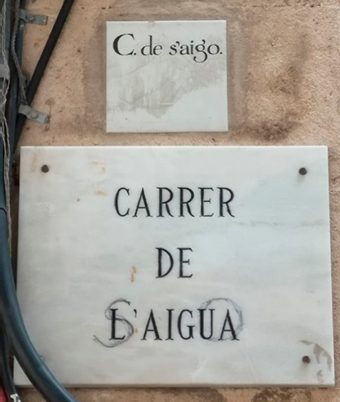

Competing identities play out not only in the name of the city, but on the very streets of Palma, too. The most common street sign is a marble plaque with the name in formal written Catalan (see Fig. 5):

More recent signs use a sans serif typeface, and those more recent still have exchanged the marble for metal, although the use of formal written Catalan remains (see Fig. 6):

Yet there are many examples where multiple versions and naming practices compete. In a small number of places, signs are included in both of the co-official languages. In Fig. 7 below it is interesting not only that the name of the “old port” is in both Catalan and Spanish, but also that the port authority’s name is in both languages:

In Fig. 8, the modern sign for the avenue, bottom left, is in Catalan, but the lettering in relief on the wall is in Spanish (both the name of the avenue and the Majorcan king after whom it is named). This indicates that the street was built in the 1950s, in the times of the Francoist dictatorship, when public use of Catalan was outlawed (although in this instance there are no other Francoist markers).

In some places, the division between languages even appears somewhat accidental, or haphazard (see Fig. 9):

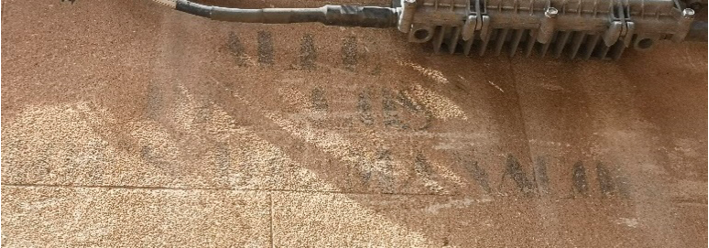

Courtesy of the author.

Yet other examples provide a much clearer link between language and cultural identity. Throughout the city there are still instances where signage dating back to the Francoist dictatorship remains, with particular markers aligning the use of Spanish with Francoist times. Many street names were changed then to commemorate Nationalist figures or battles, and one such instance is the current carrer de Manacor, which became calle de los Héroes de Manacor, commemorating those who fought against Republican forces on the island in August and September 1936. Although this name was changed in 1980, faded remains of the former designation can still be found on buildings, in recognisable black-stencilled capital letters (see Fig. 10).

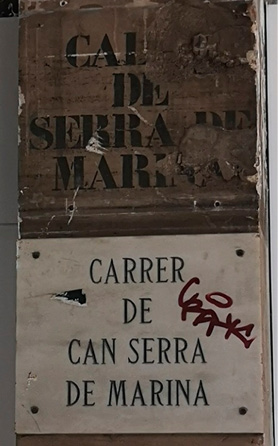

This stencilled typeface is clearer in other examples (see Fig. 11):

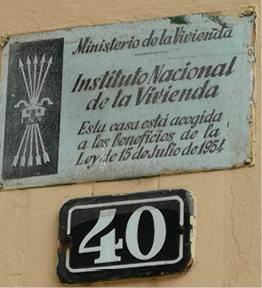

Indeed, in Fig. 11 the Catalan marker “can” (the house of) was removed in Spanish, a general phenomenon under the Francoist dictatorship, also noted by Ferrer in the renaming of the streets of Barcelona (Ferrer). Furthermore, it is not uncommon to find signs in Spanish on public housing built in the 1950s and 60s (see Fig. 12):

Here, the yoke-and-arrows symbol of the Falange, the sole legal political party under Franco, is clearly visible, linking the use of Spanish in street signage to the Francoist dictatorship—although only for those who question the existence of such symbols in the modern urban fabric.

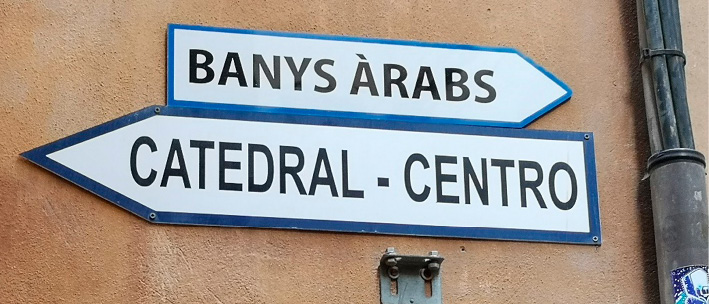

Yet it is not only the conflict between Spanish and Catalan that exists on the streets. Especially in Palma’s historical centre, the modern marble street sign is often accompanied by a smaller tile embedded in the wall (see Fig. 13):

de la Drassana, 14 June 2023; right, carrer del Vi, 5 January 2024.

Courtesy of the author.

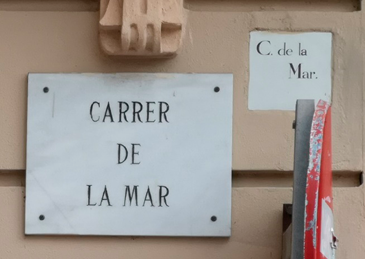

In all the three cases above, the older signs are distinguished by the use of the dialectal article es and sa, marking this as specifically Majorcan instead of the wider standard written form of the Catalan language.[10] Curiously, in some cases there is no difference between the historical and the modern sign—in Fig. 14 the Majorcan Catalan “mar” (sea) takes the article “la” and not “sa,” and so the smaller tile simply stands as a marker of former times.

Courtesy of the author.

In some cases, not only are there differences between the usage of standard and dialectal Catalan, but there is a slight difference in the name of the street as well (see Fig. 15):

18 September 2023; middle, carrer dels Set Cantons/Es set cantons, 6 January 2024; right, carrer del Deganat/C. de ca’s Degà, 10 January 2024. Courtesy of the author.

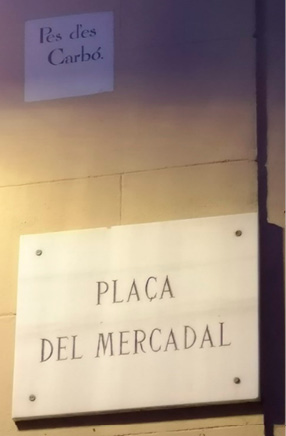

In others, the difference relates to an earlier name while using dialectal Catalan, revealing a previous history (see Fig. 16):

6 January 2024. Courtesy of the author.

Fig. 16 above refers to a previous houseowner on the street, whose nickname was “Rata” (Rat), whereas Fig. 17 below refers to previous activity—before it became a general market square, it was where coal (carbó) was weighed and sold.

Fig. 18 was once known as “Inquisition Hill,” as opposed to its current name, “Theatre Hill,” since the street comprises the steps ascending one side of the city’s main theatre. We shall return to the historical Jewish identity of parts of the city below.

It is these examples especially, as well as the dated design of the smaller tile, that link the use of Majorcan dialect to the past (and formal written Catalan to the present), while also helping to keep visible a previous layer of history. Yet it must be underlined that in terms of spoken language, the Majorcan dialect is still very much current. Thus, it is noteworthy that practices of translation are used in places to reclaim the current (and valid) use of Majorcan dialect, as demonstrated by the graffiti on the modern sign below (see Fig. 19):

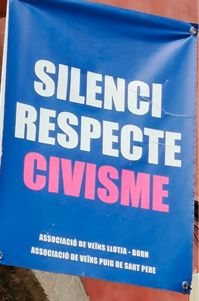

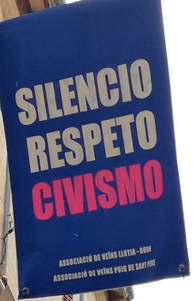

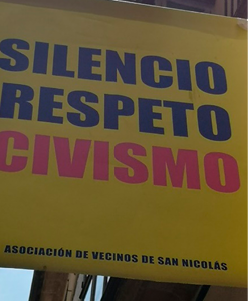

It is worth highlighting here that without the graffiti, there are still the two versions (formal written Catalan and Majorcan dialect), but the graffiti is a clear attempt to inscribe Majorcan usage on the modern layer, marking this differential identity. There are even cases where the language is manipulated to avoid any specific markers (see Fig. 20):

Note that the article is omitted from the districts sa Llotja and es Born—ensuring that the sign (or just the name of the residents’ association) is written in Catalan, whilst avoiding either including or replacing Majorcan dialectal markers. Fig. 20c is solely written in Spanish: this is uncommon (and it is telling that I could not find a Catalan equivalent for this sign).

ARE TOURISTS WELCOME?

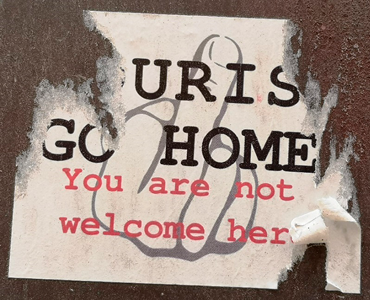

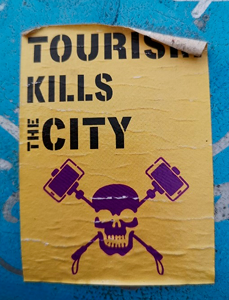

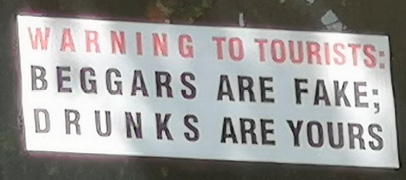

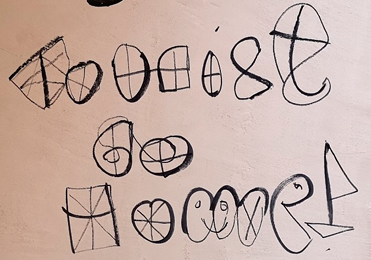

Amongst the plethora of graffiti and stickers visible on the streets of Palma, an increasing number are now associated with the movement showing concern at the island’s reliance on tourism and its effects—a movement termed both as “anti-tourism” and against “overtourism,” sometimes without a (necessary) difference being made. In terms of language and identity, there are two broad camps. Firstly, English is frequently used in texts that address the tourists themselves directly or indirectly (see Fig. 21):

Some directly raise and address stereotypical “lager lout” behaviour associated with certain tourists (see Fig. 22):

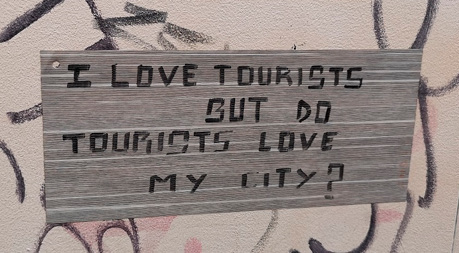

Others are of a more questioning nature, indirectly asking tourists to reflect on their own behaviour (see Fig. 23):

Courtesy of the author.

Even within this collection of monolingual notices, practices of translation reveal tensions. Some pieces of graffiti are modified, hampering the immediate recognition of the message (see Fig. 24):

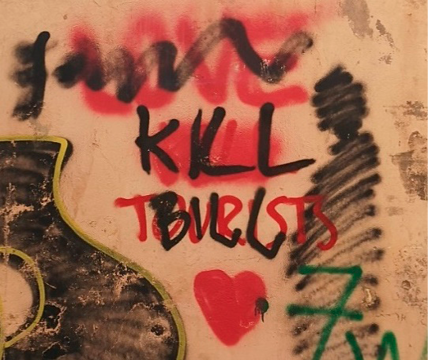

In other cases, messages are layered one on top of another (see Fig. 25):

Courtesy of the author.

Here, the original message in red, “Kill tourists,” has the “Kill” struck through and replaced with “Love” above, and presumably the heart was added at this stage. Later, in black, the “Love” has been struck through, and the original message overwritten with “Kill Bill.”

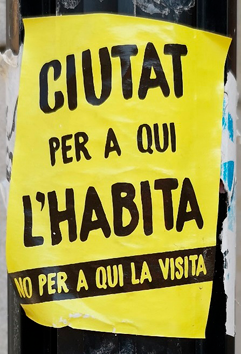

In Catalan stickers and graffiti, the messages are markedly different (see Fig. 26).

These are not aimed directly at tourists, but rather question the institutions of local and regional government on the islands (and their policies), and Catalan is the principal language used for this purpose. This is also seen in campaigns such as in Fig. 27.

Courtesy of the author.

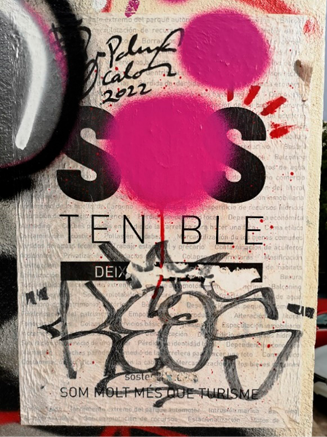

This is a response from 2021 by the street artist Abraham Calero to the SOS Turismo movement, in which the tourism sector called on local, regional, and national government (in Spanish, not Catalan) to support the tourism sector emerging from lockdown. The answer appears here as SOStenible, meaning “sustainable” in both Catalan and Spanish, but the Catalan identity is reaffirmed by the two tag lines in the language: “Deixa’t d’hòsties” (a vulgar phrase roughly equivalent to “Stop f***ing about”) and “Som molt més que turisme” (“We are much more than tourism”). Yet there is language conflict here, too: the movement’s title is in Catalan, but the background text of the poster, stating many negative effects of low-quality and unsustainable tourism, is all in Spanish. That these “terms that name the consequences of overtourism” (Bury) are in Spanish rather than Catalan adds to the idea of Spanish as the language of commerce, and Catalan as a language restricted to a symbolic use by some as a marker of local identity.

Thus, the two languages (English and Catalan) address two different audiences with two different messages. This has been taken a step further: within a context where multilingual messages are commonplace, translation is now used as a tool in the struggle against overtourism. The Majorcan anti-capitalist group Caterva has begun a campaign focused on “reclaiming” beaches across the island through posters and seemingly official notices in English and Catalan, where the English advises tourists of dangers (falling rocks, jellyfish), whereas the Catalan reassures locals that all is well. Fig. 28 presents one particularly glaring example:

Of course, this use of translation for sarcastic purposes relies in part on the trust that is necessary for translation to function at all. The inclusion of a putative Catalan source also contributes to the apparent truthfulness of the message. At the same time, beyond the contradictory messages, translation is being used again to reclaim the local identity in response to tourism: the supposed source is in Catalan, not Spanish, since it is implied that Catalan is not only the language which the local audience speaks, but with which it identifies.[11]

QUESTIONING MEMORY

In 2022 the Spanish parliament passed the Ley de Memoria Democrática (Democratic Memory Law) (Jefatura del Estado), which was designed to further the 2007 Ley de Memoria Histórica (Historical Memory Law). Within the former, “democratic memory” is defined as reclaiming and defending democratic rights and freedoms through Spain’s history, and furthering communication between generations. In its article 1.3 it also explicitly condemns the Nationalist coup that began the war and the dictatorship. In addition, its article 3.6 makes explicit reference to Basque, Catalan, and Galician speakers as victims of linguistic and cultural persecution.

As part of the initiatives to recover the democratic memory of Majorca, in December 2022 regional authorities unveiled 60 road signs across the island, labelling the roads that were built there by more than 8,000 political prisoners in the aftermath of the Civil War. These are monolingual, carrying the Catalan phrase “via construïda per presoners republicans” (Road built by Republican prisoners; see Fig. 29a). Almost immediately, they were vandalised. In some cases, layering was used as a process to eradicate the message—some signs were blacked out, and others even painted over with the red and yellow bars of the Spanish flag (Homar), layering Spanish national identity over Majorcan democratic identity, and this carried on through the first half of 2023 (Vicens). Some have even been taken down illegally, effacing the Catalan message entirely (see Fig. 29b), and the current Partido Popular administration has now decided that stolen or vandalised signs will not be replaced (Oñate), further effacing this memory (returning the representation of memory to its previous state).

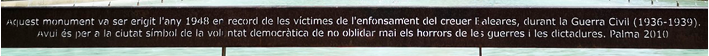

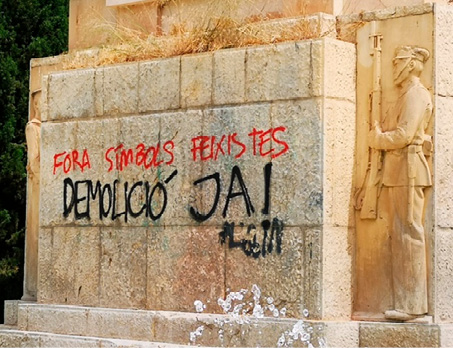

In this instance, processes of translation are used in an attempt to silence one identity. This is, however, not the only process used in such cases. One of the most infamous Nationalist symbols in Majorca is the monument in Palma known as “sa Feixina,” built in 1948 to honour the Nationalist sailors who died in the sinking of the cruiser Baleares during the Civil War.

At 20 metres tall, it bore writing in relief: “Mallorca, a los héroes del crucero Baleares. Gloria a la marina nacional. Viva España” (Majorca, to the heroes of the cruiser Baleares. Glory to the Nationalist Navy. Long live Spain), below a colossal Francoist coat of arms. This inscription remained until 2010, when, despite popular demands calling for the monument to be demolished, the city administration decided to remove the coat of arms and writing, in order to repurpose the monument in memory of all victims of the Civil War via the addition of text around it (see Fig. 31).

There are two processes of translation at play here. Firstly, the Nationalist message in Spanish is effaced (although the symbols of the soldiers at the base remain, as does the cross on the back of the monument, reminiscent of the close ties between the Francoist cause and the Catholic Church in Spain). Secondly, the new inscription, added around the base, is in five languages—from left to right: French, Spanish, Catalan, English, and German. The result is that Catalan is central, but the clear intention is that no single language should be identified with the memory that is represented. The English reads: “This monument was built in the year 1948 in memory of the victims of the sinking of the cruiser Baleares during the Civil War (1936–1939). Today it is a symbol for the city of the democratic will to never forget the horrors of war and dictatorship. Palma 2010.” It is worth mentioning that whilst the English uses “war” and “dictatorship” as singular nouns without the article (as mass nouns), the Spanish and Catalan both use plural count nouns (las guerras y las dictaduras/les guerres i les dictadures) rather than a singular that could be understood as referring to one specific war and dictatorship.

Although this dilutes the linguistic identity of the symbol, it does not address the powerful cultural and political symbolism of the monument itself. It is still the site of multiple protests—be they in the form of graffiti in Catalan, calling for its demolition (see Fig. 32) or, alternatively, displays of Spanish nationalist and sometimes fascist symbols demonstrating that such sites can be used as “espais de culte a la memòria del règim franquista” (“spaces for worshipping the memory of the Francoist regime”) (Isern Ramis 20).

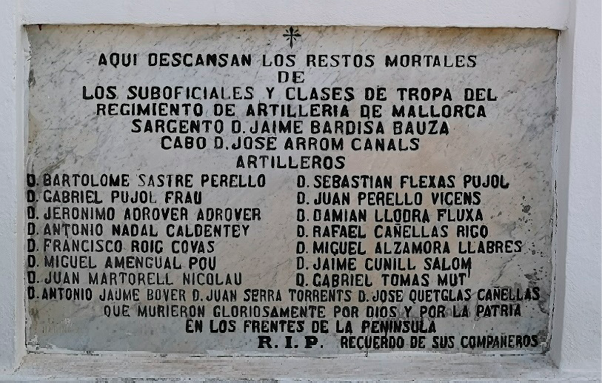

Significantly, the creation of multilingual representations is not the only resolution of conflicting identities in this field, and a distinct approach was taken with regard to a different memorial. As part of the same drive to recover the democratic memory of the island, in 2011 the authorities created a monument to more than 1,500 Republican victims of Francoist forces during the Civil War, the “Mur de la memòria” (“Wall of Memory”). Located at the site of the mass grave for the Republican dead, situated just outside the walls of the city’s cemetery, this combines sculptures, an inscription, and a multi-section iron plaque listing the names and dates. In linguistic terms, it is noteworthy that the whole text is only in Catalan—there are no translations into Spanish, nor any other of the many languages used on the islands. Yet it would be wrong to read this as a monolingual site; one must take into account the other sites of memory located close by. The “Mur de la memòria” is outside the cemetery (indeed, it is relatively hidden around the corner of a side entrance), but contraposed to this, two colossal monuments flank the main entrance to the cemetery. To the left of the main gate is a memorial in Spanish (see Fig. 33):

This was built in 1960, proclaiming “Glory to those fallen from the air” on the Nationalist side in the Spanish Civil War (Isern Ramis 104). To the right of the entrance is another monument of roughly equal height (see Fig. 34):

This bears an inscription solely in Italian: “To the sailors and airmen of Italy fallen in Spain who rest here. 1936–1939.” It must be remembered that by the end of 1936, the number of Italian troops acting with functional independence of Spanish command meant that “Italy [was] effectively at war with the Spanish Republic” (Preston 49), and this included a force on Mallorca that conducted bombing campaigns against the Republicans on the mainland. In addition to these grandiose monuments, the cemetery hosts countless contemporary inscriptions commemorating individuals who died during the Civil War—but only from the Nationalist side, and only in Spanish:

Courtesy of the author.

It follows that these sites can be read in terms of “competing” interpretations of historical memory. Spanish was the language with which the Nationalist cause identified, and thus it is the language of the monuments to the Nationalist dead; yet linguistic difference is made evident by the Italian monument as well. In the case of the monument to the victims of Francoism, the choice of Catalan is clear in the inscription on the “Mur de la memòria” itself:

Els sediciosos, d’ideologia conservadora i totalitària d’inspiració feixista, emfatitzaren en el seu ideari l’exaltació de la unitat d’Espanya, l’esperit de croada i la uniformització lingüística i cultural.

(The rebels, with their conservative and totalitarian ideology inspired by fascism, emphasised in their mindset the exaltation of the unity of Spain, the spirit of a crusade, and linguistic and cultural uniformity.)

Since Catalan is the island’s “own language,” and this is the island’s own history, there is a strong argument in favour of the monument being inscribed solely in Catalan. Yet this argument is made stronger by its juxtaposition and contraposition to the monuments that have stood for so long, thus translating previous representations—using translation to process and promote better understanding of the conflicting identities in the island’s space.

RECOVERING DISTANT MEMORY

It is not only in the recovery of democratic memory following the Civil War and dictatorship that processes of translation are evident.

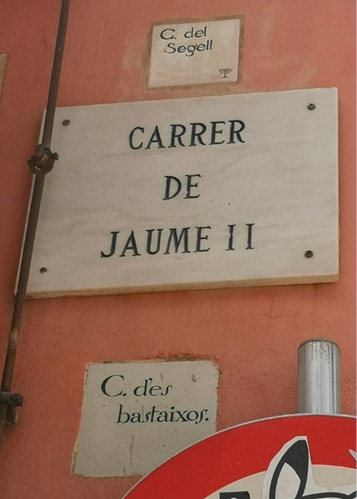

At the north-eastern end of carrer de Jaume II in Palma, the Catalan street sign is accompanied by two more tiles, embedded in the render (see Fig. 36): carrer des Bastaixos, the name before 1863, written in Majorcan dialect and commemorating the lost manual labour of hauling goods from the port; and carrer del Segell, the name when this was Palma’s Jewish quarter, before the expulsion of the Jews from the island in the 15th century, signalled by a small menorah in the bottom-right corner of the tile. Yet despite being designed to look like the much older tiles typical of many streets in Palma’s old town, the latter tile, and others like it, were only installed in 2008 (“Col.locació de rajoles”), as part of a citizen history initiative. In this case, it is precisely Palma’s translational identity that gives rise to this new output. As we have seen before, the layering of multiple street names is already prevalent, whether these are in different languages or language varieties. Here, the tile for carrer del Segell is designed to look historical (highlighting that this is a former name of the street), yet standard Catalan is used (highlighting it both as “propi”/“belonging” to the city, in Catalan, and modern, written in the standard). The inclusion of the menorah then highlights the link with the city’s Jewish history.

EFFECTS OF MAJORCA AS A TRANSLATION SPACE

For some, the effects of interaction in Majorca create a bleak picture. This is especially so with regard to tourism: Guillem Colom has explored graphic novels that project Majorca as a quasi-apocalyptic territory within the context of overtourism as trauma, where all notion of a distinct Majorcan identity is lost, sacrificed in favour of capitalist gain (Colom-Montero). Sebastià Alzamora is a contemporary author who has also explored these concerns, especially in terms of what Majorca is and will be if it loses its sense of identity. In his 2022 novel Ràbia (Rage), the protagonist lives in a tourist town where all languages and cultures exist, but none seem to meet. He reflects on the true centre of the island:

. . . no era fantasiós considerar que la veritable capital de de l’illa era l’aeroport, i que Bellavista, les urbanitzacions i la resta de municipis en constituïen la perifèria. Mers annexos de l’aeroport, la segona corona, la conurbació habitada per una població irrellevant, o sobrera: la vertadera població, la productiva, eren els turistes que entraven i sortien dels terminals. (61)

(. . . it was no fantasy to consider that the true capital of the island was the airport, and that Bellavista, the housing developments and every other district made up its periphery. Mere annexes to the airport, a surrounding ring, the conurbation inhabited by an irrelevant or excess population: the real people, the productive people, were the tourists who arrived and departed from the terminals.)

In interviews, Alzamora has even made explicit reference to both the airport and the island as “non-places” in Marc Augé’s terminology—once Majorca loses its identity, it is nothing (Claret Miranda). However, there are indications in Alzamora’s work that tourism may not be the sole, or even primary, cause of this loss of identity; rather, it may be owing to a failure to come to terms with and process conflict. In the novel, behind the resort there are agricultural lands on which shepherds carry on as they have for centuries, and yet the entire landscape is interspersed with military architecture from the Civil War; when, at the end of the novel, the narrator heads underground to explore this, he cannot find his way out. This leads us to the question: how can Majorca be sure about its own identity in the face of the influx of tourists, and how can it project this identity to them, if it has not even understood and dealt with its own past?

A more positive response comes from another Majorcan writer, Biel Mesquida. Connecting with the recovery of Jewish identity seen in the example of “carrer del Segell,” explored above, in his recent memoir he reclaims historical Jewish identity and much more as part of Majorcan identity—precisely through the naming of streets and the urban fabric. Whilst criticising the “residus franquistes que encara embruten Ciutat” (“Francoist residues that sully Palma”) (Passes per Palma 105), he praises “tot aquest enfilall de noms, mallorquins, catalans, àrabs, jueus, cristians, mediterranis, ben nostres, ben hibridats, ben mesclats, ben enigmàtics, ben originals” (“this whole series of names: Majorcan, Catalan, Arabic, Jewish, Christian, Mediterranean, entirely our own, entirely hybrid, entirely mixed, entirely enigmatic, entirely original”) (82). This indicates a path—in contraposition to the “weak” forms identified by Simon (Translation Sites 6), such as Alzamora’s contemplation of the airport above—towards strong forms of translation, conceptualised as successful intercultural understanding and an eschewal of ethnocentric discourse, where translation is used as part of identity. This interaction of all cultures in forming Majorcan daily life can be seen in Mesquida’s fiction, too, with examples in his short-story collection Acrollam. As suggested by the title—a reversal of the Catalan name for the island, Mallorca—the book aims to hold a mirror to the island’s society for it to question itself. The action of the first story, “Aiguafort al PAC” (“An Etching of a GP Surgery”), takes place in the imaginary town of Salern in central Majorca. Its narrator immediately questions, “encara hi ha pobles al Pla de Mallorca?” (“are there still towns in the middle of Majorca?”) (Mesquida, Acrollam 11), away from the coast, where the tourist industry is concentrated. In a little over 600 words, the story references the Arabs, Colombians, and Croats, as well as life-long salerners (those who live in Salern), second-home owners, characters from Mali and from Medellín, children with the Spanish diminutive in their name (Sarita) playing with Majorcan children with the Catalan diminutive (Jaumet), old Republicans who fought in the civil war, Catalan and Spanish politics, and more. Mesquida recognises the richness of cultures that make up Majorcan society, whilst defending the vitality of the Catalan language (and Majorcan vocabulary) in his work.

CONCLUSION

Each of the cases described here offers evidence of practices of translation that are used to question established narratives of identity. These occur across a range of fields, and between distinct linguistic and cultural identities, offering a solid base for extended research to develop a fuller account of how translation acts in building, reinforcing, and challenging identity across the island, whether similar processes are seen in other Catalan-speaking territories, and how this is apparent in representations of the spaces, as well as in the spaces themselves. This can be developed in conjunction with other translational spaces, to see the extent to which similar process are at play, or whether there are supplementary ways in which translation is used in building and maintaining identity, contributing to the growing range of work in the field (Lee). Further development will also benefit scholars in the humanities and beyond whose activity interfaces with how translation functions in society, and how it can be a tool for understanding our own past and present, especially as regards the recovery of democratic memory. There is also the potential for wider societal impact: cases here demonstrate that the island as well as the city is a space of “inequality and asymmetry” (Vidal Claramonte 30), and that translation has the power to address these imbalances. Thus it can help to create an evidence-based approach to value multiculturalism, and will also be an indirect benefit to cultures beyond the Catalan-speaking territories, responding to themes of multiculturalism and migration that are raised almost daily in cities around the world. There is an urgent need to appreciate greater nuance in our standard accounts of the repercussions of cultural contact, which can contribute to greater tolerance between cultures in a range of contexts, and the practices of translation identified here form an initial step on the way.

Authors

Works Cited

Alzamora, Sebastià. Ràbia. Proa, 2022.

Bibiloni, Gabriel. “La Ciutat de Mallorca. Consideracions Sobre Un Topònim.” Randa, vol. 9, 1979, pp. 25–30.

Bury, Caterina. “Abraham Calero: SOStenible.” Estilo Palma, 1 Apr. 2021, https://www.estilopalma.com/2021/04/abraham-calero-sostenible/, accessed 1 Oct. 2024.

Caterva [@Caterva_mnc]. “Si voleu utilitzar les imatges i imprimir cartells només ens les heu de demanar i vos les passarem en bona qualitat. Seguim amb la lluita!” X, 11 Aug. 2023, https://x.com/Caterva_mnc/status/1689999920084725760, accessed 1 Oct. 2024.

Claret Miranda, Jaume. “Sebastià Alzamora: ‘Mallorca és cada cop més un enorme aeroport rodejat de serveis.’” El País, 16 Dec. 2022, https://elpais.com/quadern/2022-12-16/sebastia-alzamora-mallorca-es-cada-cop-mes-un-enorme-aeroport-rodejat-de-serveis.html, accessed 30 Mar. 2024.

“Col.locacio de rajoles amb el nom antic dels carrers del call.” Memòria Del Carrer, 2008, http://www.memoriadelcarrer.com/memoria/Activitats/Paginas/2008.html#0, accessed 1 Oct. 2024.

Colom-Montero, Guillem. “Mass Tourism as Cultural Trauma: An Analysis of the Majorcan Comics Els Darrers Dies de l’Imperi Mallorquí (2014) and Un Infern a Mallorca (La Decadència de l’Imperi Mallorquí) (2018).” Studies in Comics, vol. 10, no. 1, July 2019, pp. 49–71. https://doi.org/10.1386/stic.10.1.49_1

Coromines, Joan. Onomasticon Cataloniae. Vol. VI. Curial, 1996.

Ferrer, Antoni. “Rotular de nuevo el espacio urbano: el ejemplo de la Barcelona franquista.” Cahiers d’études romanes. Revue du CAER, no. 8, 8 July 2003, pp. 163–85. https://doi.org/10.4000/etudesromanes.3087

Galán, Raquel. “La UIB considera inadmisible el topónimo Palma de Mallorca y contrario al Estatut balear.” Diario de Mallorca, 22 Nov. 2011, https://www.diariodemallorca.es/palma/2011/11/22/uib-considera-inadmisible-toponimo-palma-4014140.html, accessed 1 Oct. 2024.

Gentzler, Edwin. Translation and Rewriting in the Age of Post-Translation Studies. Routledge, 2017. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315619194

Homar, Maria. “Memoria histórica: Aparecen con pintadas más señales de carreteras construidas por presos republicanos.” Diario de Mallorca, 19 Dec. 2022, https://www.diariodemallorca.es/part-forana/2022/12/19/memoria-historica-aparecen-pintadas-senales-80180601.html, accessed 19 Sept. 2024.

Isern Ramis, Marçal. Cens de Símbols, Llegendes i Mencions Del Bàndol Franquista de La Guerra Civil i La Dictadura a Les Illes Balears. Govern de les Illes Balears, 20 June 2019.

Jefatura del Estado. Ley 20/2022, de 19 de Octubre, de Memoria Democrática. Ley 20/2022, 20 Oct. 2022, pp. 142367–2421. BOE, https://www.boe.es/eli/es/l/2022/10/19/20, accessed 19 Sept. 2024.

Lee, Tong King, editor. The Routledge Handbook of Translation and the City. Routledge, 2021. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429436468

Mesquida, Biel. Acrollam. Editorial Empúries, 2008.

Mesquida, Biel. Passes per Palma. Vibop, 2023.

Nergaard, Siri, and Stefano Arduini. “Translation: A New Paradigm.” Translation: A Transdisciplinary Journal, no. 1, 2011, pp. 8–17.

Oñate, Kike. “El Consell Dejará de Reponer Las Señales de Presos Republicanos Vandalizadas.” Última Hora, 3 Mar. 2024, https://www.ultimahora.es/noticias/local/2024/03/03/2116015/consell-dejara-reponer-senales-presos-republicanos-vandalizadas.html, accessed 19 Sept. 2024.

Preston, Paul. “Mussolini’s Spanish Adventure: From Limited Risk to War.” The Republic Besieged: Civil War in Spain 1936–1939, edited by Paul Preston and Ann MacKenzie, Edinburgh UP, 2022, pp. 21–52. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781474471763-005

Simon, Sherry. Introduction. Speaking Memory, edited by Sherry Simon, McGill-Queen’s UP, 2016, pp. 3–20.

Simon, Sherry. Translation Sites: A Field Guide. Routledge, 2019. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315311098

Vicens, Miguel. “Vandalizan por tercera vez en seis meses las señales de las carreteras de Mallorca construidas por presos republicanos.” Diario de Mallorca, 6 June 2023, https://www.diariodemallorca.es/mallorca/2023/06/06/vandalizan-senales-carreteras-mallorca-construidas-presos-republicanos-guerra-civil-88369285.html, accessed 22 June 2023.

Vidal Claramonte, María del Carmen África. “Rewriting Walls in the Country You Call Home: Space as a Site for Asymmetries.” The Routledge Handbook of Translation and the City, edited by Tong King Lee. Routledge, 2021, pp. 26–44. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429436468-4

Footnotes

- 1 Throughout the article, all translations are my own.

- 2 Key museums and sites featuring competing memories, such as Palma Cathedral; Es Baluard museum of modern art; Son Marroig as the museum of the Austro-Hungarian Archduke Ludwig Salvator, presenting his life and legacy on the island; and the former royal palace and monastery of the Cartoixa de Valldemossa, which hosted George Sand, Frédéric Chopin, Rubén Darío, and many other cultural figures in the 19th and 20th centuries.

- 3 Liminal spaces enabling movement between places, including historically significant hotels such as Gran Hotel, and key thoroughfares such as La Rambla.

- 4 Points of “colliding voices” (Simon, Translation Sites 8): these include significant commercial/socio-economic streets (Sant Miquel, Jaume III, Born, Oms, Sindicat) as well as areas with the highest incidence of immigrant communities (Son Gotleu, La Soledat, and Pere Garau for non-EU migration; and Cala Major, Sant Agustí, El Jonquet, and El Terreno for overall migration, according to data from Palma City Council).

- 5 These are defined as the meeting of the “immediate present and wider universe” (Simon, Translation Sites 8), gateways to other spaces and times, such as the translator’s study, libraries, and bookshops. These included the home of English author Robert Graves in Deià, as well as bookshops, where shop windows, displays, and shelves offer a glimpse at how these gateways are constructed.

- 6 Where language is part of surveillance and control. Evidence for this was gathered in and around Palma Airport, one of the principal points of entry to the island.

- 7 394 in June, 669 in September, and 370 in January.

- 8 Following Catalan and Spanish conventions, the generic noun in street names (e.g., carrer, calle, etc.) is not capitalised except at the start of a sentence.

- 9 Previously known as Alianza Popular (Popular Alliance), it was founded by the former Francoist minister Manuel Fraga in 1976. The formation was in power in the Balearic Islands from the region’s creation as an Autonomous Community in 1983 until 1999, and then in the periods of 2003–07 and 2011–15, and most recently since 2023.

- 10 This form of the article is not exclusive to Majorca: as well as on other Balearic Islands, it can be found in some communities on the Costa Brava and in Alacant. However, in this context its use suggests a Majorcan (or Balearic) identity as opposed to an identity shared with the rest of the linguistic domain as a whole.

- 11 It is, of course, also the language that tourists are less likely to know, but this seems an unlikely cause of choosing Catalan over Spanish, given the mutual intelligibility between the respective words for “open” in Catalan and Spanish, “oberta” and “abierta.” It is also noteworthy that similar campaigns have been carried out in the Canary Islands, using English and Spanish for differing messages.