https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8553-7517

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8553-7517

University of Lodz https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8553-7517

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8553-7517

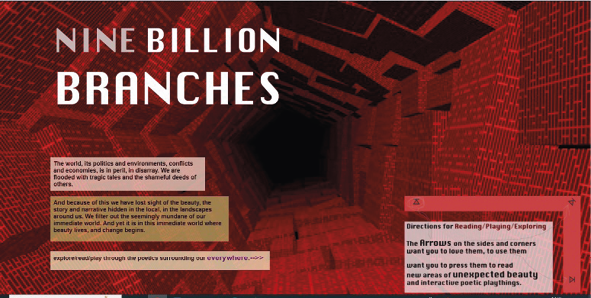

In his digital poem Nine Billion Branches, Jason Nelson explores various modes of belonging, which could be realized multifacetedly on corporeal, social, political, aesthetic and ecological levels. These locations range from the domestic (i.e. the bedroom, garage or living room) to the more abstract, such as the human body and language. The intricate network of relations between digital objects (rendered in the poem via a map of hypertextual links and limited interactivity) is expressed by means of kaleidoscopic, co-ordinate and not causal-effect connections. The article studies the notion of digital objects in Nelson’s poem, showing how the online milieu affects the reading and interpretation processes. In this context, digital hermeneutics comes into focus, especially as regards visualizations. When discussing the selected poetic titles (their total number is 40), the article explores Harman’s Object-Oriented Ontology, linking it to digitality. The article aims to analyze how following the digital paths in Nine Billion Branches, belonging to the world, to language, one’s body and locations can be perceived as a shifting web of interactions between the digital objects and readers/players, in the everchanging text that has no beginning or end.

Keywords: digital poetry, digital hermeneutics, digital objects, Object-Oriented Ontology, Jason Nelson

In Digital Hermeneutics: Philosophical Investigations in New Media and Technologies, Alberto Romele notices that new “technologies are self-actualizations of the digital in the world, and actualizations of the world through the digital” (11). Therefore, their mutual relations go beyond representational skills. Claiming that “hermeneutics is interpretation grown self-conscious,” Ong locates hermeneutical digitalization within the new kinds and channels of information and interpretation (12–14). Following this issue further, Fickers et al. perceive the digital “hermeneutics of in-betweenness” rendering basic tenets and premises and text-oriented methods in a computerized manner, while maintaining, at the same time, divergences and places of interpretive tentativeness of both approaches in exchange (9–11). As argued earlier, digital hermeneutics is much more than a new tool for interpretation. Romele elaborates this thought:

Digital technologies are indeed hermeneutics both in a “special” and in a “general” sense; in a special sense, they are hermeneutics because they structurally have and offer representations of the world that must be interpreted to access the world, and in a general sense, because in this field one has to be able to discriminate between the interpretive agencies of humans and non-humans. (10)

According to Romele, both humans and digital machines need to develop the competence to collaborate with one another in a non-anthropocentric manner, with the gradation of outputs, potential capabilities and limitations (143–44). In accordance with the above, he recognizes the creative input (emagination) and the original expertise of non-human interpretive machines (13, 143). On the simplest level, one can include in this category productive text generators. In digital hermeneutics, metaphors and symbolism are, as Romele puts it (10), operational and not only figurative, decreasing the breach between the world and what it stands for (18). According to the philosopher, digital hermeneutics moves beyond depiction, it reads and alters the world, “bridge[ing] the gap between textual narratives and material technologies,” as Romele reminds one, drawing upon Coeckelbergh and Reijers (71).

Referring to digital objects, Romele introduces van den Boomen’s term “material metaphors” because they are coded specifically so as to be read by machines and symbolically for people’s use (101). Digital objects transcend text-image-hyperlink combinations. Yuk Hui in his study On the Existence of Digital Objects argues that when objects are coded into the web-based environment, they acquire an identity specific to them which distinguishes them from any other objects. This emerging individuation process corresponds to the transition from things (Ding) into objects (Gegenstand), as pointed out by Hui with reference to Heidegger (50). As a matter of fact, Hui differentiates between two processes named by him as “objectification of data” and “dataification of objects” (50). Commenting upon Heidegger’s understanding of things, Hui observes that this line of thinking along with technicality can lead to establishing “a convergence between humans and the world,” where due to recognizing objects’ agency, the human and the world may renegotiate their being together/apart in networked environments (41). For Hui, this turn cannot happen without recognizing the relationality of objects and Heideggerian “Dasein’s being-in-the-world” which, as he stresses, is the function of belongingness (227).

Along with Dasein (being-there), Heideggerian categories of In-der-Welt-sein (being-in-the-world), Mitsein (being-with) and Geworfenheit (thrownness) represent different functions of belonging and modes of being.[1] In Being and Time, Dasein renders relationality with the world (being-in-the-world). Heidegger argues: “Dasein is never ‘initially’ a sort of a being which is free from being-in, but which at times is in the mood to take up a ‘relation’ to the world. This taking up of relations to the world is possible only because, as being-in-the world, Dasein is as it is” (57). Heidegger considers Mitsein (being-with) as a determinative condition for being-in-the-world. In accordance with the above, the philosopher states: “The world of Dasein is always a with-world [Mitwelt]. Being-in is being-with [Mitsein] others” (116). Furthermore, Geworfenheit (being-thrown-into-the-world) opens up a trope of speculations and interconnections; Heidegger speaks about “a mode of being in which it is brought before itself and it is disclosed to itself in its thrownness . . . The average everydayness of Dasein can thus be determined as entangled-disclosed, thrown-projecting being-in-the-world, which is concerned with its ownmost potentiality in its being together with the ‘world’ and in being-with others” (175–76). Out of these concepts being-thrown-into-the-world (Geworfenheit) remains the most elusive but, at the same time, in its entangled nature, seems to be most intimately related to (digital) immersion. Ryan in Narrative as Virtual Reality 2: Revisiting Immersion and Interactivity in Literature and Electronic Media maintains that digital immersion involves what she defines as “recentering” of potentialities into the virtual world in which interaction is a sine qua non condition of belonging. One could say, drawing upon Ryan’s work, that digital immersion involves being-in-the-(virtual)-world and creating a network of relations within the space of mapped objects. Ryan argues that “we could not feel immersed in a world without a sense of the presence of the objects that furnish it” and appear to people in the shared digital milieu. As regards categorization of objects, Heidegger distinguishes between ready-to-hand (Zuhandene) and present-at-hand (Vorhandene) objects (Hui 16). Ready-to-hand objects are contemplated by theorizing and categorizing their essence, while present-at-hand objects exist via their interactive, everyday usability (16). This distinction with regard to objects, as Hui observes, takes into account not only relationality in logic but technicity (Simondon) as well, which has paved the way for the evolution of digital objects (16). From Heidegger’s concept of Vorhandenheit Hui proceeds to “[d]igital objects [that] are at the same time logical statements and sources for the formation of networks” (25).

Following the same vein, Hui asks rhetorically: “What is the being-with of a digital object? Is it the screen, the keyboard, the mouse, other entities on the screen, the operating system, or the hardware. . .?”, coming to the conclusion that it embraces a “totality of relations” (116). This aforementioned totality of relations is not just physical contact with the computer but overcoming boundaries implicit in thinking about digital objects as representing objects in real life. In Hui’s understanding, due to their relationality, digital objects can establish milieus, systems and networks (140). Moreover, relationality becomes the first condition enumerated by Stiegler (x) when defining digital objects:

Digital objects consist of data, metadata, data formats, “ontologies,” and other formalisms that all fall within the process of grammatization, and it is as such that they form a digital milieu woven through these relations—alongside other objects. But this implies the possibility not just of an associated milieu but of a dissociated milieu, giving rise to new forms of both individuation and disindividuation. (xi)

Belonging rests upon relationality: the object negotiates its identification, writing itself into the network of connections with humans, their language and bodies. In the digital poem/fiction Nine Billion Branches by Jason Nelson, belonging is realized via digital objects to which readers/players might relate due to their assumed familiarity and recognizable location (inside the house, the human body, the public and private commercial spaces). However, the familiarity of digital objects is only apparent. As a matter of fact, objects on the screen are not the same as “ordinary objects” one can know (or claim to know) from first-hand experience or even narrated objects in the printed text. Stiegler articulates this clearly: digital objects and their environment, the computer languages in which they exist, cannot be reduced to the already known concepts (ix). Hui subscribes to this viewpoint, adding that “computation relies on a new type of materiality that disrupts some of the concepts that are fundamental to philosophy, for example, what is an object?” (3). Computational objects, Stiegler argues further, are “of technical essence” but they remain mysterious—“it is an object neither of experience nor of intuition” (xi). Digital objects, as claimed by Stiegler, are both created by and creating the digital environment, which, in consequence, requires different forms of interacting with the text and, in consequence, different reading habits.

In Nine Billion Branches, digital objects mediate between readers (players) and the text. Heim claims that “[h]ome is the node from which we link to other places and other things” (92). In his digital poem, Jason Nelson redefines the notion of “home” by offering his readers a posthuman view upon inner and outer locations, whether inside a house or human body. Nelson tells his narrative by means of objects; all the locations bear the traces of people’s absence. Object-narratives in digital literature seem to draw from Object-Oriented Ontology. As if addressing this issue, Harman observes that “[a]ll objects must be given equal attention, whether they be human, non-human, cultural, real or fictional” (Ontology 9). He explores it further: “Objects act because they exist, rather than existing because they act” (260). The object narratives in Nine Billion Branches are defined as “local” but they gradually become entangled with home (oikos) ecology, fusing the home with the world. There are 40 mini-poems (called poetic tiles) linked to the objects and the reader decides which path and which story to follow. Applying a cursor and choosing a “home” path, the readers in Nine Billion Branches may explore the meticulously composed poetic information about objects situated in the bedroom, living room and the garage. By cursor, the audience may also choose a path of embodiment: human organs, telling their own stories, are demonstrated on an anatomical model. Finally, when going outside the house, readers may visit a mall empty of people. Following the trope of people’s metaphorical and literal absence and the general reduction of human signification, gradually in the digital poem, words become objects; “the vanished real object is replaced by the aesthetic beholder herself or himself as the new real object that supports the sensual qualities” (Harman, Ontology 260).

Overall, the aim of the article is to study how the interactions of one’s potential belonging and identifications (house, body, world) are rendered in a digital space where objects attain their agency. The structure of the article proceeds from the theoretical and methodological background, through a more detailed account of Object-Oriented Ontology via metaphors, to the interpretations of objects in the socio-political sphere and ecology.

In the article “Towards Hermeneutic Visualization in Digital Literary Studies,” Kleymann and Stange observe that the current discussion concerning digital literary hermeneutics concentrates on one main problem: how to “digitally replicate interpretive processes known from the analog world. However, a systematic effort to reflect on how the hermeneutic premises might be answered by digital technology is still missing” (sec. 19). One reason why it is missing is the refusal to acknowledge that the analog (text) and digital (works) belong not only to different media but to different modes of relating to the world. Much has been written on that subject, therefore, without going into details, let me just provide some examples. The text does not simply appear on screen to be interpreted, it can be recombined and alterered constantly, it can disappear from the screen for good after a few seconds, or it can be personally modified when camera or localizations are allowed, to name but a few differences. Reading lexia is always preceded by a sequence of movements, and if the algorithm is programmed to change the sequencing, once taken, a singular digital literary path practically cannot be reentered. All of these factors alter the dynamics of understanding the text and the context and the entire process of interpretation. Simanowski rightly argues that instead of language-centered hermeneutics, digital literature needs to focus on “a hermeneutics of intermedial, interactive, and performative signs. It is not just the meaning of a word that is at stake, but also the meaning of the performance of this word on the monitor that may be triggered by the reader’s action” (32). It is hard to disagree that “[i]n terms of possibilities to reconfigure and restructure,” the digital environment to a large degree allows creators freedom unattainable for analog works (Kleymann and Stange sec. 20). This freedom, as observed by Kleymann and Stange, is realized mostly in the sphere of hermeneutic visualizations; visual and auditory aspects and their relations to lexia provide the source for interpretation. What is more, Johanna Drucker in Visualization and Interpretation: Humanistic Approaches to Display (2020) argues that texts, graphics and music are to a large extent annotations themselves (62). With regard to digital objects, Drucker proposes a “nonrepresentional, . . . nonmimetic . . . and generative” (74) approach to graphical arguments, treating them as “a primary act of knowledge production” (69). Referring to the digital world and situated interactions within, Drucker points out that “[n]ot only is our view of digital objects changed, but we see the possibilities for using the digital environment to take apart the ‘is-ness’ of things” (61). What is more, in the understanding of critical hermeneutics, Drucker refers to a text as “a field of potential or possibility,” or “a provocation” and an act of reading/interpretation as “an intervention” (62, 4). With regard to Jason Nelson’s digital poetic work analyzed in this article, this “provocation” can be aptly labelled after Ryan as “dysfunctionality,” or a conscious acting against the web protocol. In Narrative as Virtual Reality 2, Ryan argues that dysfunctionality is always qualified but also relational in the sense that it refers to assumptions about not performing a function in relation to its usability, for instance, an aberrant application or operation of the code, tools, language, etc., in general. Dysfunctionality meticulously designed by Nelson in Nine Billion Branches reveals itself mostly via visualizations: the frames, red-marked graffiti made by pencil tools superimposed upon digital images; in other words, functional digitality is also deconstructed. Kleymann and Stange argue that digital visualizations under some specified conditions can become what they call a “missing link” in digital literary hermeneutics (sec. 35). Among these conditions, they underscore, drawing upon Drucker’s earlier research (2016, 2018) that interpretation is not simply exhibited or represented but constructed on the screen (which itself is an “interactive and visual environment” and so is interface (sec. 36–37). What matters as well is “multiple views on the object of hermeneutic inquiry” (sec. 39), leading to multiple nonlinear and nonhierarchical relations between all digital objects involved in the process. However, as stressed by Ryan, an immersive text needs to “create a space, to which the reader, spectator, or user can relate, and it must populate this space with individuated [digital] objects.” The following section will explore in detail how it is constructed in Nelson’s Nine Billion Branches.

As stated earlier, readers enter Nelson’s poem/fiction via digital objects, and their multiplicity prepares them for a multi-layered “nine-billion branches” hypertextual structure. The words appear to be the see-through inscription on the interface, superimposed upon digital objects. This transparency allows access into other layers which arrange the space inside the poetry tiles. The directions are visually rendered in the form of hypertext arrows and animation. The graphics and photosensitive effects bring to mind the gaming mode of reaching subsequent levels. This association is not accidental because, apart from critically awarded digital poetry, Nelson is the author of very popular poetry games (e.g., Game, game, game and again game[2]). What is more, he asserts that poetry and games have much in common: for instance, the specific language that they develop. Nelson adds that in his poems, he applies strategies tested in games, such as shifting attention (“Poetic Playlands” 337, 347).[3] Further, in hotspots, readers of Nine Billion Branches have powers of extra zooming upon objects, studying them and observing them from a different angle. Generally speaking, employing Ryan’s categorization, interactivity in Nine Billion Branches can be classified as predominantly external-exploratory (the reader moves in the world of objects and by exploring selected links, at their own pace, creates relations with objects but the narrative is not altered by the player’s actions) and partly internal-ontological (e.g., in The Festival and “Location 4,” where the player’s movements in real time [or inertia] transform the environmental narrative). Overall, the interactivity of Nelson’s poem’s hypertextual relations might overwhelm the user with various modes, degrees and tropes of belonging.

When studying the poem, one can follow “nine billion” hypertextual branches that might appear to arise from the giant “root-book,” (Deleuze and Guattari 5) which links the code with the text. However, Deleuze and Guattari warn that the (one could say analog) “root-book” is “noble, signifying” and mimetic (5), adding that “mimicry is a very bad concept since it relies on binary logic to describe phenomena of an entirely different nature” (11). Pursuing a much more multiple, relational and heterogeneous concept of rhizome, Deleuze and Guattari explain that “the rhizome connects any point to any other point . . . it brings into play very different regimes of signs, and even nonsign states. The rhizome is reducible neither to the One nor the multiple . . . is composed not of units but . . . of dimensions. . . . directions in motion” (21). The philosophers later elaborate the notion: “A rhizome has no beginning or end; it is always in the middle, between things, interbeing. . . . alliance [whose] fabric is the conjunction, ‘and . . . and . . . and . . .’” (25). Deleuze and Guattari stress that rhizome is “a map and not a tracing” (12). Returning to Nelson’s poem, it has the form of an unranked mapping of digital objects. The poem has an intricate database (Ryan’s category) structure with a list of locations on the homepage from which one can begin their explorations. Vectors pointing to different directions that are conspicuous on each website enable readers/players to change their route any time and at any place, hence, database functions like rhizome with “always . . . multiple entryways” (Deleuze and Guattari 12). The database structure questions the analog narrative’s elements: with no linear story to unfold, no beginning or end, “and . . . and . . . and . . .” multiple possibilities. Nine Billion Branches does not simply shuffle the poetic files/tiles or create multiple endings, but the algorithm written according to this pattern does not by its design allow anything that can be called “the beginning” or “the end,”[4] and the visualizations assume the form of the aforementioned “directions in motion.”

Even before exploring poetic tiles, viewers experience almost physically the structure of digital objects’ multiple layers. Taking visualizations into account, the dynamic kinetic experience puts participants in the middle of a moving tunnel, as if they were on a ride. Vivid contrasting-color graphics surround viewers with bright red and black pulsating blocks (of data?) shifting constantly, accompanied by unnerving sound. In the interactive world of Nine Billion Branches, mobile images intensify an effect of in-depth immersion into the black passage leading down the rabbit hole. What is more, we are already falling down the rabbit hole “before” even activating a cursor. The optical effect of mobile “poetic tiles” only loosely and arbitrarily attached to one another ensures that the reader’s narrative standpoint is constantly destabilized.[5]

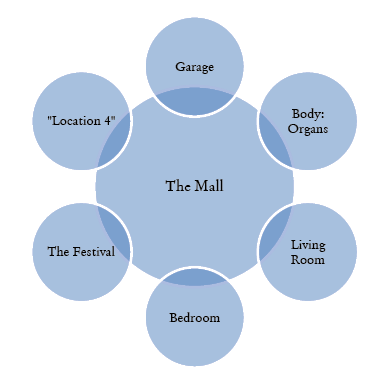

To exist, the digital poem requires active participation: should viewers not wish to meander along the navigational arrows and study more objects, the text (poem/fiction) could not come into being. Navigating an interactive path in Nelson’s work is not linear but to a large extent conducted in the dark inside the carefully designed tree structure. Generally, the screen image has about two-eight active hotspots (with objects to click) to open fragments of the text. In total, Nine Billion Branches is made of 40 “poetry tiles”; however, the number of permutations and possible paths is much larger. Some paths intersect and bring one back to the point of departure or lead to a different tile with a new central object. The audience loses the presence of other objects only temporarily and the loss is not irredeemable. It comes at a price: the viewer must come to terms with the narrative’s extensiveness and, as a result, the text’s probable incompleteness, and their own limited control. Depending upon the chosen path, the reader can alter the order of “tiles” in which they appear on screen and in some cases (The Festival, Words) alter the sequence of particular words. In the majority of locations (The Bedroom, The Garage, The Living Room, The Body), should the reader choose a different path by returning to previous objects, the text will not change automatically in a combinatory algorithmic way. In such cases, the fragmented text is correlated to a given object permanently, and, as a result, what can change is the reader’s perception (understanding) in the context of other objects’ exploration. Overall, there are three types of navigation in Nelson’s Nine Billion Branches: the aforementioned object-text set (rooms inside the house and organs inside the body), where clicking on a single digital object does not direct us any further, interactive text-generation (The Festival, The Words), and the Chinese box structure in the Mall whose digital objects lead to still other objects. Below is a diagram of the possible locations with regard to the Mall:[6]

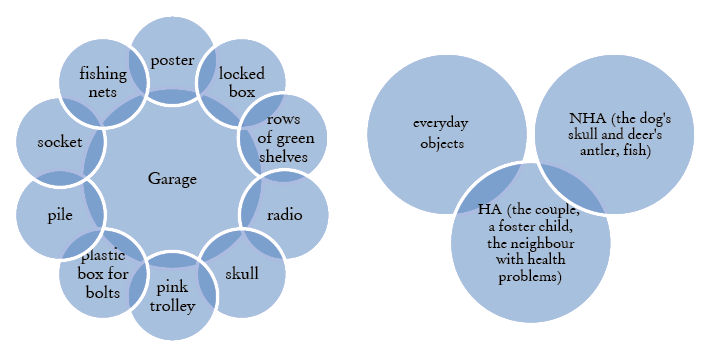

The Mall leads to the objects in the rooms, organs in the body, kaleidoscopic images of the circular sequence and separate words that become objects themselves. Furthermore, virtual locations do not define these objects; their mutual relation comes from the non-hierarchical shared online environment. The structure of the poem relies upon the spatial immersion created by objects in interaction with other objects. The yellow background with a central location image framed in a square acts as a reminder of the arbitrary relations between objects, pointing to other worlds outside the main frame. Let one take the Den, or the Garage:

As seen above in the example of just one “room,” Nine Billion Branches may not have exhausted the titular number of combinations that the human brain may embrace, but with all the poetic tiles and hypertext, it may well come close to it. Nelson’s collage variety and the countless literary (path) options drew the attention of literary theorists. Critically, his poetic style (I made this. you played this. we are enemies) was appreciated for using “texts from exterior sources, fusing them with raw, open forms of original verbal and visual expression” (Funkhouser 172). What is more, like many other digital works by Nelson, Nine Billion Branches received wide critical acclaim (Queensland Literary Award) and was selected by Artshub as among the 10 best digital literary works.

In Nine Billion Branches, the conventional division into the objects inside and outside the house does not make sense. Regardless of deep immersion, digital objects constantly refer readers to what is beyond this reality. Therefore non-categorizing between the objects (on the basis of whether they are situated inside the rooms or inside the body, outside the Mall, or are located in language) leads us to different understandings of what the world seems to be, or rather may become. In other words,

In noticing the difference between home and the many things “outside,” we leave the formal definition of world and its worldhood and turn to the content: the things themselves that get assimilated and belong to the world. How do things belong to a world? Of course, the genesis of each world affects how the things emerge and relate to one another, and each world’s genesis gives the things in that world a distinctive cast and color. (Heim 93)

Nine Billion Branches attempts to raise the question of how (digital) objects belong to the world. On the whole, all objects, according to Harman’s Object-Oriented Ontology, regardless of whether they are organic, non-organic, artefacts, or speculative, or imagined, are to be regarded as on a par with others and given the same amount of consideration (Ontology 9). Objects and their properties should be differentiated and not confused; both properties and objects can be either real or sensuous. Sensuous objects mediate between real ones and they are strictly relational. The existence of real objects is not related to the effect they could or could not produce (ibid.). One of the key rules of OOO is the withdrawal of objects: they do not interact directly with one another or humans (12). What is more, an object is not a sum of parts and not as much as its impacts (53). In The Democracy of Objects, instead of qualities, Levi R. Bryant focuses on the potential aptitudes that each object has and which may vary depending upon an object (89). Furthermore, Bryant advocates for what he calls the subjectless object, “that is for-itself rather than an object that is an opposing pole before or in front of a subject. . . . an object for-itself that isn’t an object for the gaze of a subject, representation, or a cultural discourse” (19). In other words, he argues that objects exist regardless of human existence or interpretations. Among objects Bryant enumerates e.g., language, intellect, artistic events, and planetary constellations, atoms or rocks (18).

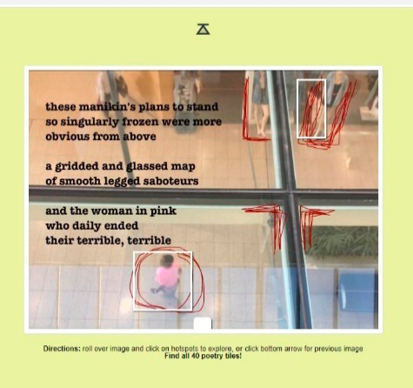

Objects in Nelson’s poem, whether a small ceramic figurine, words, the liver, a box for bolts, the forklift truck, the quilt, antlers, humans, an animal skull, or a plastic, manufactured plant are treated as equal and none of them is privileged over others. Moreover, in Nine Billion Branches, humans are entangled in relations with other objects, but they do not hold a principal position in these equations or control the narrative. In his poem, Nelson demonstrates this quite explicitly: digital tiles do not operate around people as main protagonists with nonhuman objects in the background but the other way round. Visually, if people appear on screen at all, they are small, blurred objects in the background, frequently masked by red pen doodles.

Throughout the whole poem, these apparently hand-written red graphics “achieve playfulness through dysfunctionality with respect to practical reality” (Ryan). Accordingly, Ryan stresses that dysfunctionality, apart from being the author’s own ironic commentary on the text and at the same time having an aesthetic value, meditates upon the operational, social and critical dimension of the digital world’s status. In the case of Nine Billion Branches, the red circles with the authorial annotations direct the readers’ attention to the less vivid digital objects that become foregrounded dryly in this way. In terms of visualizations, the play with light and shadow and the angle of viewpoint (whose perspective the screenshot presents) remains of vital importance. For instance, in the tile below, in the shot from above, one cannot see human faces or any other details in their vague, transparent silhouettes, therefore it becomes impossible to distinguish mannequins from people:

As argued above, the red-circled “woman in pink” seems to be indistinguishable from other (human? non-human?) objects. What is more, (human? nonhuman?) mannequins are endowed with agency (they plan their positions), “singularly frozen,” as if waiting to move. The alliterated “gridded and glassed map,” reveals a calculated pattern executed on the polished, square-tiled floor. On the other hand, as the image is presented from a bird’s-eye view, the grid belongs to the glass and steel ceiling. One might wonder why mannequins are called “smooth legged saboteurs,” and why their bare legs are circled and linked with deliberate obstruction. Maybe their nonchalant poses are interpreted as provocative because by standing on their own, unparalleled in their singularity, they wish to maintain a degree of autonomy, instead of being grouped en masse. What is more, there is discomfort in their positions, because mannequins are waiting for “terrible terrible” to terminate. The emphatic repetition of the adjective without a completing noun suspends the unfinished sentence in the air. As in OOO, the objects are related through their sensuous qualities, remaining withdrawn from access, as if erased from the image. Let us examine the tile below:

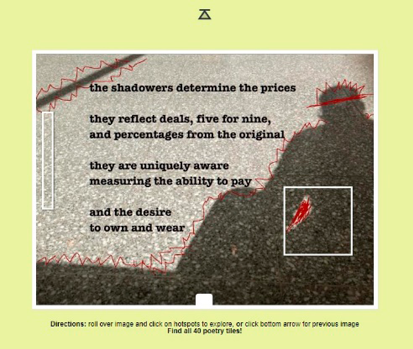

To some extent, Nine Billion Branches could be retitled “objects and their humans” but in OOO, object relations are non-categorized. As mentioned earlier, in Nelson’s poem, there are not many silhouettes of people but the few remaining are out of focus, compared to shadows, or rather, as in the tile in question, to “shadowers.” The transparent humanoid above is sarcastically crowned with the graffiti-like hand-drawn line. Being de-crowned from their special position in the Anthropocene, this mock regal insignia of ruling over all species is verbally rendered in ironic expressions: “uniquely aware” and “the desire / to own and wear.” The cognitive capabilities: “reflect,” “aware,” “measuring,” “determine,” “ability to pay,” numerical calculations—previously used as the instrument of exclusion—indicate in Nine Billion Branches that mental powers (see the ironic “percentages from the original”) no longer guarantee a “unique” status, however much the purchasing power of money in late capitalism promises to make up for this loss. The red pencil drawn doodle on the shadow’s side seems to signify a wound or blood. Following this line, the circled contour appears to resemble the corpse in a criminal investigation. Returning to the role of visualizations, seemingly human-made red commentaries to the image, as argued by Ryan in Narrative as Virtual Reality 2, imply the author’s intervention, and I believe they can function as a type of internal self-interpretation to Nelson’s text.

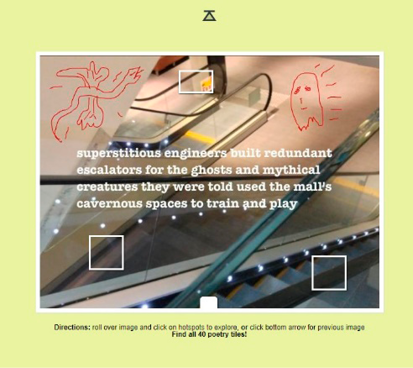

The empty elevators, uncanny (valley) mannequins and ghosts in a hollow commercial space bring to mind Romero’s Dawn of the Dead (1978), where the closed shopping center becomes the shelter from zombies for the last humans. Nelson’s mall is almost human-less: it is a hiding place of objects but also their imprisonment, it is humans who seem to be zombie-like intruders invading the territory that does not belong to them. In the tile, imaginary objects (“ghosts and mythical creatures”) and their needs are taken equally seriously (“to train and play”). “Redundant escalators” imply the miscalculation in the number of users. The reference to “cavernous spaces” (the ironic connotations with nature) appears to resonate with Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan” (“caverns measureless to man” 379), which remains in sync with the supernatural ambience of this poetic tile. The trope of objects’ confinement in anthropomorphic representation leads readers to the passage that articulates it openly:

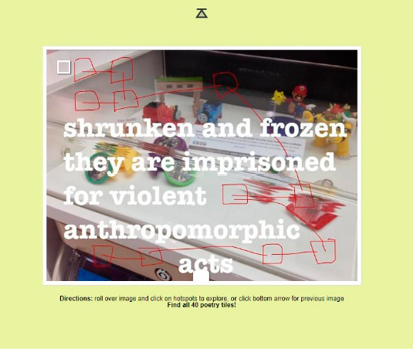

In this tile, objects pay for the violent (imposed upon them) anthropomorphic likeness with being a smaller, restrained and immobilized version of the human-centered world. The poem operates around the consonant “r” appearing in the first syllable of nouns and verbs, which intensifies the auditory effect of harshness. The enjambed and centralized “acts” leave the whole line for the modifier “anthropomorphic,” giving prominence to this single word as the key concept of the whole poetic fragment. The sole word “acts” constitutes a clash between the capacity to do and the lack of mobility (“frozen”). Looking at the screenshot, one cannot help repeating after Dolores, the android in the Westworld series, who cites Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet: “These violent delights have violent ends” (2.6.9, 51). In other words, the statement prophesizes the need to terminate “violent anthropomorphic” representations of objects. How this order can be undone is depicted in the poetic tile below:

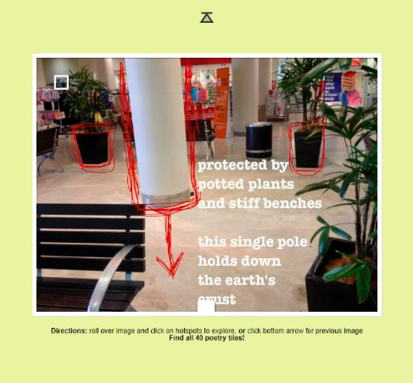

Here, the center of the world/the mall is a single pole that supports the Earth. Surrounded by other safeguarding objects (benches and potted plants), it keeps the world in its steady position. The text refers to the surface of the Earth but it does not diminish its stabilizing role. The poetic tile this time operates upon repeated plosives: protected, potted, plants, pole. The ironic reversal of the perspective is enhanced by the red pencil arrow that seems to suggest that the pole indeed goes deep beyond the shop floor into the core of the Earth.

In conclusion, Bryant and his democracy of objects call for removing humans from the predominant position (“a redrawing of distinctions and a decentering of the human”) but not, as the thinker stresses, from philosophical investigations (20). Comparable to the non-anthropocentric narrative structure in Nelson’s poem, what Bryant questions is the fact that humans do not wish to be one of many, therefore, and prefer treating other objects as what he calls fictions (38), “correlates or poles opposing or standing-before humans” (20). Nine Billion Branches perfectly subscribes to this statement, laying bare the ghostly and ghastly fictions of human-objects relations. However, neither Bryant in The Democracy of Objects nor Nelson by applying a non-anthropocentric perspective in his digital poem wish to overturn this scheme to replace it with the other extreme. In other words, the model does not work by substituting subjects with objects (Bryant 22). The philosopher concludes:

Subjects are objects among objects, rather than constant points of reference related to all other objects . . . we get a variety of nonhuman actors unleashed in the world as autonomous actors in their own right, irreducible to representations and freed from any constant reference to the human where they were reduced to our representations. (22–23)

Similarly, Nelson in Nine Billion Branches attempts to strip objects of the human representational “fictions” and present them in relations to other objects but not as their interfaces. In other words, he encourages us “to think the being of objects unshackled from the gaze of humans in their being for-themselves” (Bryant 19).

Humans and nonhumans are intertwined, as argued by Bryant in The Democracy of Objects, in collectives of human and nonhuman objects, which globally make up what people understand as the world (23–25). The collectives in Nine Billion Branches reveal their entanglements (Bryant borrows this concept from Barad) to readers who decide to open hotspots, selecting one of the objects framed in a square. Without this action, objects remain hidden from view. These collectives involve the belongings in the house, the humans that produced them, the humans who purchased the objects, nonhumans (plants, animals killed in hunting or in cruel experiments, given bone growth hormones) whose body parts are kept in the Garage, and many more. Bryant elucidates that “collectives involving humans are always entangled with all sorts of nonhumans without which such collectives could not exist” (25). Nine Billion Branches’ poetic tiles provide commentary about such entanglements, human and nonhuman alike. In Nelson’s poem, the emphasis is put, as one might repeat after Latour, on the act of gathering different “materialities, institutions, technologies, skills, procedures, and slowdowns with the word ‘collective’” to achieve, what he calls, “the progressive and public composition of the future” designs (59).

Nine Billion Branches has been praised by critics for commenting upon the “commercialization of public spaces and politization of private spaces” (Groth). The poem meditates in several tiles on the exploitative production of low cost, mass manufactured goods. For instance, the ceramic figurine in the Living Room contains a message not revealed to anyone, confided to an object by one of the part-time workers who made it. Overall, in Nine Billion Branches, objects tend to be appreciated for what they represent to humans rather than what they are. In the Living Room tile (above) the taste for foreign-looking overseas objects can “transform damage into trailer park royalty.” The Bedroom narrative is one of self-deception and false pretenses. “The Not Homemade” quilt produced by machines programmed to make mistakes in sewing is meant to imitate hand-made craft, created with care and dedication. In the Bedroom, the window is covered with a rifle and the national flag which literally and metaphorically blocks the access of daylight, “polyester filter, symbolic / and generic / pride pride vague pride.” The “polyester” pride of one’s country, declared excessively and repeatedly, carries connotations with being a “weapon” for isolationism and xenophobia. The synthetic screen made of non-renewable petroleum symbolically fuses national and ecological chauvinism. The flag makes the room factually darker. The last line of this poetic tile refers to the proverbial rifle “aiming / towards the monsters living in the closet, hiding beneath ill-fitting shirts.” The “ill-fitting shirts,” are made of the aforementioned polyester, which is the political (made of petroleum) and biological (non-biodegradable) weapon itself. The speaker refers to the filter (“We filter out the seemingly mundane of our immediate world”) in a different sense in the opening paratext:

The world, its politics and environments, conflicts

and economies, is in peril, in disarray. We are

flooded with tragic tales and the shameful deeds of

others.

And because of this we have lost sight of the beauty, the

story and narrative hidden in the local, in the landscapes

around us. We filter out the seemingly mundane of our

immediate world. And yet it is in this immediate world where

beauty lives, and change begins.

In the opening lines of the paratext, the narrator enumerates several areas of focus (politics, environment, economies) that on a declarative level breed disenchantment and irritation (see “peril, disarray,” “tragic tales,” “shameful deeds,” and “conflicts”). What appears worth noticing is that responsibility is relocated to “others” (“shameful deeds of others”), hence it means renouncing any personal/species, class, etc. accountability. The collective identification “we” appears in relation to landscapes that have to endure consequences of the hazardous actions referred to above. Consequently, the opening lexia encourages “us” to pursue beauty in the less obvious, hidden, everyday objects and scenery. One might expect the poetry of the dancing plastic bag from American Beauty (1999) and these associations are not entirely ungrounded. Nelson’s poem is indeed political, not only because it contains an overt critique of the conservative right-wing outlook but it is political in Arendt’s sense, encouraging to “act in concert,” seeing politics as engagement in the collectives of others. Arendt writes: “Power is never the property of an individual; it belongs to a group and remains in existence only so long as the group keeps together” (44).

In Nine Billion Branches, collectives of objects encompass non-human beings as well as organic and non-organic entities. The poem shows that not only nonhuman animals lose their habitats. There is no land to grow plants, either. Plastic flowers in the Mall are “manufactured / and this plant will never transform / sunlight / and nitrogen into fibrous veins.” Ironically, the object in the tile imitates the ZZ plant (Zamioculcas zamiifolia) which is believed to resemble the plants that survived the extinction of dinosaurs but turned plastic in late capitalism. The replacement of organic plants by their plastic substitutes seems to make sense as regards commercial market strategies. Plastic plants are cheaper to produce; they endure all weather conditions; they are easier to store, transport and sell; and, finally, they require virtually nothing of the customers. As regards power relations with humans, the allegedly immobile plants are located below animals on the scale of deserving people’s appreciation. In the poetic tile below, potted plants in the Mall are hostages “captured” by human pirates.

By reversing the perspective in the poem, “forcing the mall’s walls into straighter lines,” the poem implies that plants keep humans alive and not the other way round. In the past, the tree in the mall used to “hold the ship together” in one piece. The tile above mocks the apparent immobility of plants as the potted tree travelled all over the world on the cruise ship. In another tile, analogous to the corpse sprouting in the garden in T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land (“The Burial of the Dead”), “[i]n the spring, the tiles sprout wild, / flowers, and the tables grow vines / twisting and winding around / shopper’s feet.” When Eliot, drawing upon Baudelaire, calls a reader-brother in crime “hypocrite lecteur” (7) the audience of Nine Billion Branches seem challenged to believe in the sprouting of concrete and tiled floor in the shopping center. Nelson’s digital poetry appears to be saturated with numerous intertextual references; the OOO school of philosophy correspondingly acknowledges openly its strong affiliation with art and its creative rather than communicative function (Harman, Ontology 44), especially with metaphors.

Harman claims that metaphors, like philosophy, provide what he calls a “non-literal access to the object” (260). Therefore, in the section “Five Features of Metaphor,” he attributes special significance to this figure of speech, claiming that instead of meditating on the object from the position of the observer, “[w]hat metaphor gives us, instead, is something like the thing in its own right: the infamous thing-in-itself” (86). In addition, the philosopher defines metaphors as “non-reciprocal” (one cannot reverse the relation without the change in meaning), “asymmetrical” (categories may be similar but never the same), “coupling” (they produce a new double entity), and adds that in the lack of a real object, they engage the reader/speaker (86-87).

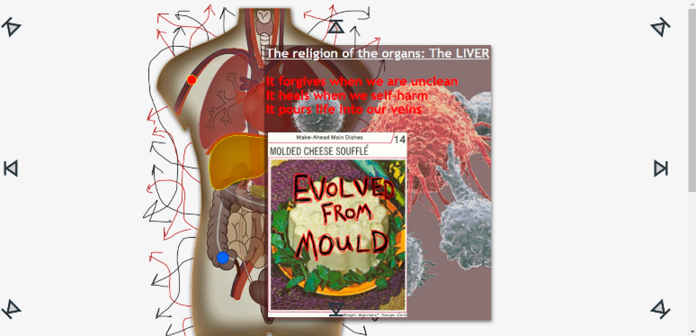

Two metaphorical tiles chosen from Nine Billion Branches come from the Body section and the Mall but they both draw upon a reference to faith. In the poetic tile below, the liver is the main priest in the religion of organs. The grounds for comparison provide the spiritual qualities of the liver: being restorative and generative. The organ generously absolves humans and nonhumans from their trespasses and transgressions. The adjective “unclean” has a double meaning. The first refers to religious conviction, which tends to pass moral judgments upon one’s purity, and the latter to the organ that cleanses the effects of (dietary) indulgences. The liver performs the non-judgmental liturgical service: “It forgives when we are unclean / it heals our self-harm / it pours life into our veins.” The liver does not discriminate in terms of gradation of sins: even self-injurious behavior can be pardoned and cured. The mold turned into food reminds one of the origin and the end of the organic body. Searching for transcendence elsewhere, one actually carries it inside. The reader can find forgiveness in the materiality of their organ.

Overall, hypertexts related to nodes (vital organs in the human body) might be classified according to “three new ontological effects,” as Bell calls them: “flickering, refreshment and merging” (267). The animated diagram of the human body creates an illusion of the factual item, only the arrows (signifying connections) that arise from this torso model weaken this “realistic” effect. The liver drawing link leads to the metaphorical poem (analyzed above) about the liver’s importance in the human body. What is more, it is accompanied by a digital image that looks like a “scientific” computer model of some cells (mold?) under the microscope. Therefore, as Bell puts it, readers are flickering “back and forth between the actual and the textual actual worlds,” finding them to overlap at least temporarily (261). The ontological refreshment with subsequent “factual” links additionally blurs the aforementioned boundaries yet does not dissolve them. The further we go, the process of fusion between the reality on screen and the world around readers and hypertextual information intensifies. The ontological mergence happens when “the fictionalized account of a real-world event is enhanced by extratextual sources” (266). In Nine Billion Branches, using the same example, the ensuing links inside links introduce the cookbook recipe of the molded cheese soufflé with a dramatic inscription “Evolved from Mould,” written in a font used in classic horror film openings. This way, the human liver, bacteria and dietary habits become reunited within one scare narrative.

Comparatively, in the article “Digital Hermeneutics: From Interpreting with Machines to Interpretational Machines” (co-written with Marta Severo and Paolo Furia), to which he refers in his book, Romele applied Paul Ricœur’s triple mimesis in the hermeneutic process of prefiguration, configuration and reconfiguration to digital analyses, understood as transition “from traces to data,” “from data to methods” and “from methods to information” (74, 94). With Nine Billion Branches in mind, one can consider the first stage of mimesis as recognizing predispositions for the digital map of the Home/World to be explored, then designing/coding the spatial and narrative plan of all the locations in Nine Billion Branches with the external and internal links, finally allowing three ontological stages to balance the narrative with what goes beyond the fictional and beyond the initial design: namely, co-creating it with readers/players.

In the latter metaphorical tile, the shopping mall early in the morning is compared to a neo-classical temple. At first view, the consumerist mall, paralleled with the church of late capitalism, may not seem a very original idea. Additionally, Roman basilicas performed public functions and seeing analogies between capital’s professed supernatural powers and the new religion may appear cliché. The architectural likeness with pillars, proportions, porticos or an empty courtyard provides the visual ground for comparison. It is hard to disagree that too close a semblance spoils the effect of metaphor and that it is better to seek what philosophers call “inessential likeness” (Harman, Ontology 74). However, when examining Nelson’s metaphor more deeply, it appears that the supermarket-basilica is in fact a confinement for birds who beat their wings, trying to get out, and hurting their claws in this effort. The expression “unlocking / the gates” brings to mind opening the penitentiary door. Ironically “open / to flocks of birds” means the opposite: it traps them inside. In Nelson’s poem, it appears that birds tidy, “dusting / the arches,” but from a human perspective, they are not welcome due to their alleged uncleanliness. The birds’ painful attempt to leave the mall, rendered in “claw / carved palatial lines,” evokes A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy by Sterne, where the caged starling taught to imitate one sentence in human voice, kept repeating “I can’t get out.” What is more, the tile evokes associations with Shakespeare’s sonnet LXXIII, where the trees devoid of leaves are compared to a derelict cathedral with birds as the choral group which used to sing there (“Bared ruined choirs, where late the sweet birds sang” 527), connoting the passage of time. By analogy, one can imagine the rubble from ancient times and the fall of the shopping temple to set the birds free.

Appreciating its imaginative potential, Harman[7] explains that no metaphorical object (let us refer here to Nelson’s poem directly: for example, the liver or the shopping center) can be approached in full, as he calls it, in “its inwardness,” as “the thing in itself” (Ontology 82); in consequence, it is combined with the metaphorical qualities incorporated into the reader who substitutes the object (83). Bogost in Alien Phenomenology, or What It’s Like to Be a Thing calls metaphors “speculating about the unknowable inner lives of units” (61). Despite his doubts, which I share, about putting the human back at the center of metaphorization, he believes that analogy is the only method of getting to know unknowable objects (64). However, the digital world offers more options to study objects than simple analogy. The arguments for this claim are provided in the following section, i.e. shifting relations between the words, letters and the context related in the process of spectacularization.

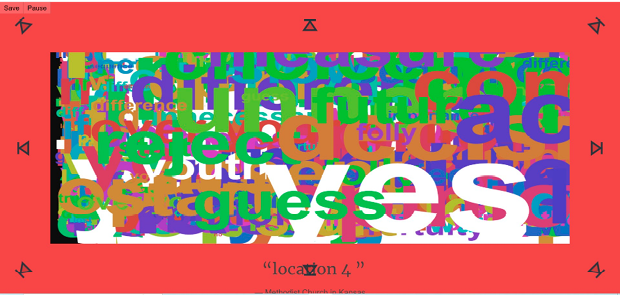

Digital poetry as a medium can offer graphic visualizations of the aforementioned analogies realized via kinetic word-objects. When digital objects are online, which is the sine qua non condition of their existence, as proved by Hui, they create their own network of other objects with which they are linked via the internet. In Nine Billion Branches, two locations (“Location 4” and The Festival) are rendered in this way. Instead of “familiar objects,” readers are presented with mobile words which are objects to be seen and looked at and not just read. In digital poetry, it is quite a frequent strategy, sometimes employed on its own and sometimes in connection with graphics or larger fragments of text. Ryan in Narrative as Virtual Reality 2 calls such loose words “spectacles” and she refers to the process of splitting the signifier from the signified as “spectacularization,” concluding that “[w]ith the full spectacularization of language, semantics no longer matters, words and letters become pure shapes, and the text takes the last step out of literature into visual art.” In Nine Billion Branches, the past, memories and the present are marked by digital temporalities and modalities. The process brings to mind Hui’s individuation understood as the underlying forces in which digital objects are making and remaking their status, “renegotiating [their] relations with other objects, systems, and users within their associated milieux. Digital objects also take up the functions of maintaining emotions, atmospheres, collectivities, memories, and so on” (57). In the case of “Location 4” and The Festival, readers’ actions and affective reactions (the quickness of the cursor) can produce meaningful change in the content’s generation.

Each word in “Location 4” seems to move in separation; the connections between them are open and temporary. Word-objects appear quickly layered one on another, making the reading process almost impossible for humans. Terms such as “accept, different, guess, important, measure, slow, opinion, decision, etc.,” can be of different color and size; however, those with positive connotations are always colorless. Such transparent capitalized writings (e.g., Youth, You, Future, Yes) provide hope for the world’s new direction. However, without readers’ engagement, the transparent concepts get covered entirely by colorful and more expansive words and they disappear under them. The objects’ appearance and their pace is related to participants’ cursor activity. As in most text-generators, the number of combinations makes seeing exactly the same screen very unlikely. It takes a lot of clicking to evoke this big YES out of randomly appearing words on the screen, YES resembling the ending of Molly Bloom’s soliloquy in Joyce’s Ulysses, in which she embraces the sensuality of the world declaring “and yes I said yes I will YES” (933). Yes to collectives and the democracy of objects, to their non-discriminative treatment and the home (oikos) that exists as the accumulation and relationality of objects.

In “The Festival,” the mobile sentence uncoils and coils into a spiral (a metaphor of the hermeneutic circle?), making and un-making itself. At the beginning (see the screenshot above), it is structured in the shape of a globe, but one cannot read any words yet. Left on its own, kinetic graphics gets unknotted and expands continuously, words become bigger and bigger until they obscure the whole screen, creating a claustrophobic and suffocating effect. When the sentence unwinds further, readers can see that it raises the ecological and global question, “how much are we going to pay making rain and oxygen?” While occupying the entire screen-space, images seem to use up all the oxygen. No sooner than the reader gets involved dynamically by moving the cursor repeatedly, the accumulation of the dense words decreases. Navigating the cursor, the reader as if literally cleanses and oxygenates the screen/world; however, one has to do it continuously because without the player’s engagement, the text nearly immediately refabricates and reestablishes itself, claiming back the screen. The screenshot below shows the text’s reaction to the multiple clicking on the right-hand bottom of the screen.

Both of these interactive images illustrate how much being engaged in the ecology of things, at the level that Latour calls “common dwelling, the oikos” (180) can produce operational effects not only in the case of deoxygenation. Latour stresses that from the earliest times oikos meant the dwelling for human and nonhuman collectives before it became an exclusionist and anthropocentric concept. He argues:

One’s home, habitat, or dwelling is called oikos in Greek. Commentators have often been astonished at the fate of the word “ecology”—“habitat science,” used to designate not the human dwelling place but the habitation of many beings, human and nonhuman, who had to be lodged within a single palace, as in a sort of conceptual Noah’s ark. (131)

In conclusion, the structure of my analyses of Nine Billion Branches operated around the digital layers intersecting with the image of home with unordered collectives of objects. Latour’s thought best summarizes the assumption underlying this article: “It is to the topos, the oikos, that political ecology invites us to return. We come back home to inhabit the common dwelling without claiming to be radically different from the others” (224). Nine Billion Branches embraced home for digital objects, metaphors, words and different ways of belonging to them. The methodological background for these interpretations came from philosophers and thinkers associated with several branches of Object-Oriented Ontology. In my analyses, I attempted to prove that “digital technologies are structurally hermeneutic” (Romele 10), which in my case studies was argued with regard to digital visualizations. In the aforementioned explorations, digital objects are not treated as figurative representations or humans’ projections; they exist autonomously, on their own terms. The autonomy of the objects is best rendered in the poem’s rhizomatic structure, based upon nonhierarchical connections with no end or beginning. Apart from their aesthetic value, the digital hermeneutic visuals that Nelson aptly uses in his work provide additional commentary on the text in terms of its social, political and ecological dimensions.

katarzyna.ostalska@uni.lodz.pl

Arendt, Hannah. On Violence. A Harvest HBJ, 1970.

Bell, Alice. “Digital Fictionality: Possible Worlds Theory, Ontology, and Hyperlinks.” Possible Worlds Theory and Contemporary Narratology, edited by Alice Bell and Marie-Laure Ryan, U of Nebraska P, pp. 249–71. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv8xng0c.15

Bogost, Ian. Alien Phenomenology, or What It’s Like to Be a Thing. U of Minnesota P, 2012. https://doi.org/10.5749/minnesota/9780816678976.001.0001

Bryant, Levi R. The Democracy of Objects. Open Humanities P, 2011. https://doi.org/10.3998/ohp.9750134.0001.001

Coleridge, Samuel Taylor. The Complete Poems. Edited by William Keach, Penguin Classics, 1997.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Felix Guattari. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. 1987. Translation and foreword by Brian Massumi, U of Minneapolis P, 2005.

Drucker, Johanna. Visualization and Interpretation: Humanistic Approaches to Display. MIT P, 2020. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/12523.001.0001

Eliot, T. S. The Waste Land. 1922. Edited by Michael North, Norton, 2001.

Fickers, Andreas, et al. “Digital History and Hermeneutics: Between Theory and Practice: Introduction.” Digital History and Hermeneutics: Between Theory and Practice. Studies in Digital History and Hermeneutics. Volume 2, edited by Andreas Fickers and Juliane Tatarinov, De Gruyter, 2022, pp. 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110723991

Funkhouser, C. T. New Directions in Digital Poetry. Continuum, 2012.

Groth, Simon. “Still Defining Digital Literature.” The Writing Platform, 20 May 2018, https://thewritingplatform.com/2018/05/still-defining-digital-literature/, accessed 18 Nov. 2023.

Harman, Graham. Art and Objects. Polity, 2020. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315270562-4

Harman, Graham. Object-Oriented Ontology: A New Theory of Everything. Random, 2017.

Heidegger, Martin. Being and Time. 1927. Translated by Joan Stambaugh, foreword by Dennis J. Schmidt, SUNY P, 2010.

Heim, Michael. Virtual Realism. Oxford UP, 1998. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780195104264.003.0007

Hui, Yuk. On the Existence of Digital Objects. Foreword by Bernard Stiegler, U of Minnesota P, 2016. https://doi.org/10.5749/minnesota/9780816698905.001.0001

Joyce, James. Ulysses. 1922. Introduction by Declan Kiberd, Penguin Modern Classics, 2000.

Kleymann, Rabea, and Jan-Erik Stange. “Towards Hermeneutic Visualization in Digital Literary Studies.” Digital Humanities Quarterly, vol. 15, no. 2, 2021. https://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/15/2/000547/000547.html, accessed 16 Jan. 2024.

Latour, Bruno. The Politics of Nature: How to Bring the Sciences into Democracy. Translated by Catherine Porter, Harvard UP, 2004.

Nelson, Jason. Nine Billion Branches. http://media.hyperrhiz.io/hyperrhiz17/gallery/nelson/index.html

Nelson, Jason. “Poetic Playlands: Poetry, Interface and Video Games Engines.” Electronic Literature as Digital Humanities: Contexts, Forms and Practice, edited by Dene Grigar and James O’Sullivan, Bloomsbury, 2021, pp. 335–49. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781501363474.ch-030

Nine Billion Branches. ELMCIP, https://elmcip.net/creative-work/nine-billion-branches, accessed 18 Nov. 2023.

Nolan, Jonathan, and Lisa Joy, creators. Westworld. Based on a book by Michael Crichton. HBO Entertainment, 2016–22.

Ong, Walter, J. Language as Hermeneutic: A Primer on the Word and Digitization. Edited by with commentaries by Thomas D. Zlatic and Sara van den Berg, Cornell UP, 2017. https://doi.org/10.7591/9781501714504

O’Sullivan, James. Towards a Digital Poetics: Electronic Literature & Literary Games. Palgrave Macmillan, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11310-0

Punday, Daniel. “Rereading Manovich’s Algorithm: Genre and Use in Possible Worlds Theory.” Possible Worlds Theory and Contemporary Narratology, edited by Alice Bell and Marie-Laure Ryan, U of Nebraska P, pp. 296–314. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv8xng0c.17

Romele, Alberto. Digital Hermeneutics: Philosophical Investigations in New Media and Technologies. Routledge, 2020. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429331893

Ryan, Marie-Laure. Narrative as Virtual Reality 2: Revisiting Immersion and Interactivity in Literature and Electronic Media. Johns Hopkins UP, 2015. E-book.

Shakespeare, William. Romeo and Juliet. Edited by John Dover Wilson, Cambridge UP, 1969.

Shakespeare, William. The Complete Sonnets and Poems. Edited by Colin Burrow, Oxford UP, 2002. https://doi.org/10.1093/actrade/9780198184317.book.1

Simanowski, Roberto. Digital Art and Meaning. U of Minnesota P, 2011. https://doi.org/10.5749/minnesota/9780816667376.001.0001

Sterne, Lawrence. A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy. 1768. Introduction and notes by Paul Goring, Penguin, 2005. E-book.

Stiegler, Bernard. Foreword. Translated by Daniel Ross. On the Existence of Digital Objects, by Yuk Hui, U of Minnesota P, 2016, pp. i–xiiii.

Tabbi, Joseph. The Bloomsbury Handbook of Electronic Literature. Bloomsbury, 2017.