https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8332-7396

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8332-7396

University of the Balearic Islands https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8332-7396

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8332-7396

Ionian University https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3633-3686

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3633-3686

The pandemic crisis of COVID-19 that we have recently endured, and that to some extent we are still experiencing, abruptly changed the way in which we conceive of the interaction between inner and outer space. Specifically, during the most difficult times caused by the two severe lockdowns, this limitation came complete with a total lack of spatial mobility. This article will explore the impact that this had upon the creative process of writing and making performance work for the female subject and how the return to the domestic space as the only possibility, affected their writing and creativity. Using the concept of the “nomadic subject” developed by Rosi Braidotti in 1996 and revised in 2011 in her book Nomadic Subjects: Embodiment and Sexual Difference in Contemporary Feminist Theory, this article aims to explore these questions from the intersection of body and language through the symbol of the spiral as a source of creation.

Keywords: nomadic subject, female subject, performance, embodiment, desire, COVID-19

This article reflects upon unity and collaboration in artistic creation during times of crisis by focusing on the project Spirals developed by PartSuspended artist collective. In particular, it deals with the concepts of unity and collaboration as creativity within times of enforced isolation, absence and individuality caused by the critical times of COVID-19. The pandemic crisis that we have recently endured, and which to some extent we are still experiencing, abruptly changed the way in which we conceived of the interaction between the inner and outer space. During the most difficult times caused by the two severe lockdowns, this limitation led to a total and complete lack of spatial mobility. The article explores the following questions: what kind of impact did the enforced isolation have upon the creative process of writing and making performance work for PartSuspended artist collective? How did the return to the domestic space as the only possibility affect their writing and creativity as female artists? Using the concept of the “nomadic subject” developed by Rosi Braidotti in 1996 and revised in 2011 in her book Nomadic Subjects: Embodiment and Sexual Difference in Contemporary Feminist Theory, this article aims to explore the aforementioned questions from the intersection between body and language through the symbol of the spiral as a source of creation. This point constitutes the basis of the project Spirals and questions the extent to which the constant and repetitive motion shaped in a circular form destabilized historical and preexisting conceptions of feminine subjectivity from the perspective of sexual difference as developed by Rosi Braidotti.

In order to put forward this enquiry, the article shall refer to the extent to which the interaction between the particular experiences of the female subject and the limitation—or lack—of spatial mobility, foregrounds creative action and proposes alternative forms of “being together” from the perspective of the sexual difference. This consideration is an important point in the process of becoming of the feminine subject that weaves a particular net of connection with the other. As we shall see, the woman writer or the woman artist constructs and reconstructs through the movement of a spiral an alternative, circular and transgressive space at the time that she creates. In Rosi Braidotti’s words:

The nomadic subject functions as a relay team: she connects, circulates, moves on; she does not form identification, but keeps on coming back at regular intervals. The nomad is a transgressive identity whose transitory nature is precisely the reason why she can make connections at all. Nomadic politics is a matter of bonding, of coalitions, of interconnections. (42)

Within this theoretical framework, the project Spirals goes beyond the poetic creative experience and incorporates practice-as-research into related areas such as language, images, sounds, city-spaces and voice within the symbolic space. In this sense, art is understood as praxis and relates personal experiences to theoretical configurations of female subjectivity. Given the connections between PartSuspended’s modus operandi and the theoretical framework of the “nomadic subject,” this article shall suggest that collaborative art can be taken as the mechanism/tool/form whereby the female subject intervenes in the existing structure of signification at times when all kinds of action are either limited or relegated to silence. Prior to analyzing this point, the need to consider creation and art through the lens of practice-as-research for the female artist should be foregrounded.

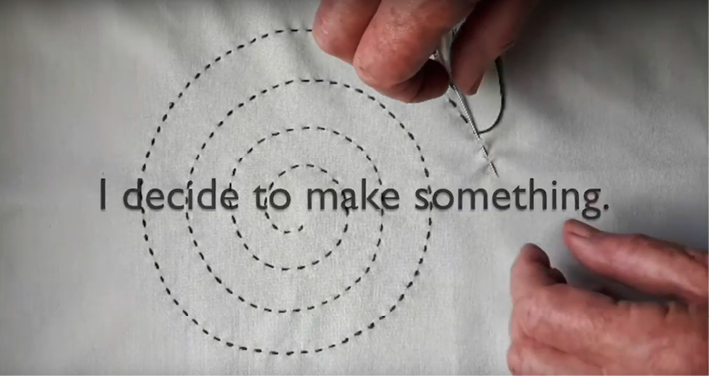

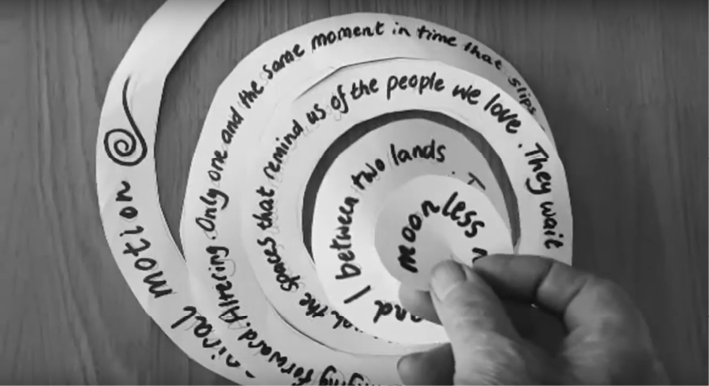

Fig. 1. PartSuspended, SPIRALS: Turning Points (London, Dorset, Athens, Agost), 2020, https://youtu.be/Vcp4Dt4_e_Y, © PartSuspended.

One of the principal points that Braidotti relates to the consideration of the female subject as nomadic relates to the need to think beyond traditional forms of thought and challenge the boundaries that separate reason from imagination and critique from creativity. In this sense, creation unveils an intrinsic imaginative element embedded in such an act that “strives to create collectively empowering alternatives. The imagination is not utopian, but rather transformative and inspirational. It expresses an active commitment to the construction of social horizons of hope. Hope is a vote of confidence in the future” (Braidotti 14). This perspective connects with one of the kernels of PartSuspended artist collective. PartSuspended artist collective was founded in 2006 and they are particularly interested in feminist work that focuses on issues emerging from personal and collective experience, domestic actions, the poetic text, social spaces and architecture. They employ a range of performance practices, such as physical work, devising, writing, video and sound work that have been presented in a variety of forms, including live performances, installations, exhibitions, publications, participatory workshops. Their projects are often multilingual so as to remain inclusive and expand language boundaries; multidisciplinary, in order to encourage a creative dialogue between fields of study; and multimedia, so as to explore the intersection between performance as a place and time-bound event and technology. Their work has been presented at a variety of venues and international festivals in the UK, Spain, Greece, Serbia and Czech Republic.

The core members of PartSuspended artist collective (Noèlia Díaz Vicedo, Hari Marini, Barbara Bridger, Georgia Kalogeropoulou) are researchers as well as artists, whose academic interests cover a wide range of disciplines, such as architecture, urban studies, cultural studies, women’s literature, feminism, performance writing and philosophy. Departing from conventional quantitative and qualitative models of research, the collective embraces practice-as-research strategies and creative practice that shapes and informs research. It is not only Braidotti who has suggested the need to put creation and imagination at the centre of meaning-making; Brad Haseman has also stated that “[p]ractice-led research is intrinsically experiential” and that often its methodological approach to identifying the research problem, outlining the objectives, reflecting and evaluating the outcome may differ from traditional research methodologies” (100). The method of working, the research problem and research questions are shaped by particular thoughts and desires in relation to individual experience. Practice is a critical part of research and deepens connections and alternative pathways of inquiry. As Haseman points out, “[t]he ‘practice’ in ‘practice-led research’ is primary—it is not an optional extra; it is the necessary pre-condition of engagement in performative research” (103).

PartSuspended seeks to explore ways of practising and researching, eschewing traditional strategies and narratives. By carrying out experiments for testing concepts and practical investigation, the collective creates material through writing, editing, improvisation, reflection and discussion. In each project the collective sets up questions and areas of research, exploring different angles of looking at the project; a creative dialogue across disciplines and research interests is initiated. In this sense, the special issue “On Spirals” published in the European Journal of Women’s Studies (Bridger, Kalogeropoulou, Marini and Díaz Vicedo 155–89) integrated a collection of essays built on the different layers of thought that each member of the collective was interested in exploring. Barbara Bridger explored “Spiral as Metaphor,” Hari Marini focused on “A Woman’s Spiral in Cityscape,” Noèlia Díaz Vicedo analyzed “The Female Poet Creates Spirals: A Question of Nomadism?” and Georgia Kalogeropoulou centred her research on “Desire and Rage: A Female Spiral.”

Since the late-twentieth century, practice-as-research has become a significant though controversial paradigm of conducting research and was introduced in the academic setting. According to Baz Kershaw et al., the “practice turn” was “characterised by post-binary commitment to activity (rather than structure), process (rather than fixity), action (rather than representation), collectiveness (rather than individualism), reflexivity (rather than self-consciousness), and more” (63–64). In their work, as in other similar creative processes that seek non-traditional, non-hierarchical structures, the process itself is a significant part of the creative journey. Furthermore, collaboration is one of the main ingredients of their practice, and a precondition for any performance work that seeks to incorporate a range of different perspectives and promote polyvocality. Collectiveness and multiplicity of voices and actions contribute to the production of creative strategies rather than a fixed methodology that applies to any project and participant.

It usually demands time and dedication for a group to create their own codes of collaboration and strategies for balancing the collective and the individual perspectives. Tim Etchells, the artistic director and founding member of the renowned experimental theatre company Forced Entertainment, wonders: “[O]r is collaboration this: a kind of complex game of consequences or Chinese whispers—a good way of confounding intentions?” (55). Collaboration entails misunderstandings as well as trust; failing as well as discoveries; confusion as well as clarity. Certainly, collaborative processes allow for a plurality of voices to be heard and open endless possibilities in exploring the subject matter. This kind of freedom can provoke chaos, frustration, anxiety or uncertainty, but it is also where flexibility, diversity, surprises and intuitions may emerge.

Although methods of creative enquiry have shaken established scholarly research approaches, the way in which knowledge through practice is produced and the value of it are still somehow in dispute. Reflecting on the binary opposition between practice and theory that has proved challenging within academic studies, Dwight Conquergood explains that the way that knowledge is organized in the academy mainly supports “a distance perspective” rather than “a view from ground level, in the thick of things” (312). He states:

The dominant way of knowing in the academy is that of empirical observation and critical analysis from a distanced perspective: “knowing that,” and “knowing about.” This is a view from above the object of inquiry: knowledge that is anchored in paradigm and secured in print. This propositional knowledge is shadowed by another way of knowing that is grounded in active, intimate, hands-on participation and personal connection: “knowing how,” and “knowing who.” This is a view from ground level, in the thick of things. (312)

PartSuspended is interested not only in the rupture between life and art but also in keeping artistic work as an on-going process and in a sense unfinished. Furthermore, the name of the collective, PartSuspended, seeks to reveal an intrinsic part and aim of the collective. On the one hand, it shows the connection of their work with contemporary urban spaces given that “part suspended” is used on the announcement boards of London Underground when a disruption happens. On the other hand, it implies the way that the collective embraces creatively unexpected encounters, unforeseen interruptions and postponements. They have often presented projects as being-in-progress. This is mainly derived from the thought that the multiplicity of stories co-existing in life opposes the notion that there is only one teleological line of thought, a final outcome, or one way of exploring the complexities of a number of matters through creative processes. As Deirdre Heddon and Jane Milling observe:

[A] group devising process is more likely to engender a performance that has multiple perspective, that does not promote one, authoritative, “version” or interpretation, and that may reflect the complexities of contemporary experience and the variety of narratives that constantly intersect with, inform, and the very real ways, construct our lives. (192)

PartSuspended collective are interested in positioning themselves within the matter explored through performance means. Their personal responses and embodied experience are part of the process itself and feed into their research. They are looking for a “hands-on participation and personal connection,” to borrow Conquergood’s words. This is particularly significant for the female subject not only as an artist but also as a substance of feminist thought. Braidotti has urged the feminist nomadic subject to break free from what Teresa de Lauretis has called “The Oedipal Plot” of theoretical work (1986) (qtd. in Braditotti 23). The members of the collective dedicate themselves to the creative process, whilst caring for and trusting one another. During the challenging pandemic period, the need to rethink their ways of collaborating and making creative work emerged, alongside the need to support one another and resist isolation. The concept of care moved into the foreground and became a vital element to be considered as part of their practice. However, prior to engaging with this point, the next section will deal with the provocations emerging from the shape and motion of a spiral.

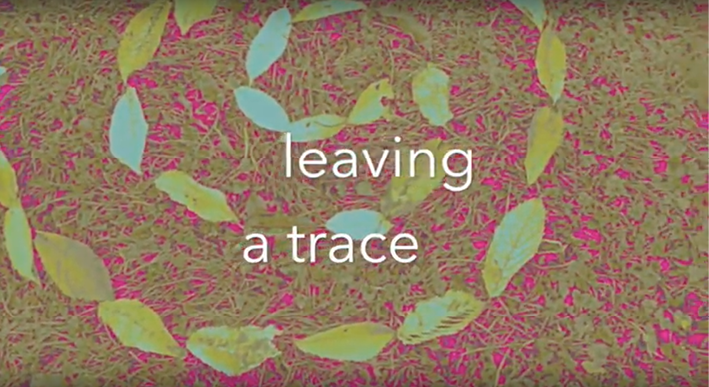

Fig. 2. PartSuspended, SPIRALS: Breath (London, Dorset, Athens, Agost), 2021, https://youtu.be/YfvSeDlZkUE, © PartSuspended.

The complete 2020 lockdown in the UK coincided with the coming of Spring and many of us relieved our isolation by spending time outside. Walking, or in the garden, I became acutely aware of the prevalence of the spiral form in nature: the scales on a pine cone, the formation of leaves or petals on a stem, the curl of a snail shell, the twist of a vine, the Fibonacci series at the centre of every daisy and the uncoiling tendrils of a fern. As time went on, I made new spirals out of existing spiral forms: a whorl of empty snail shells, a curl of cones: spirals within spirals. As part of PartSuspended’s process, we shared our spiral images; our many natural versions of this form and this sharing connected our different experiences. The spiral form held us together and when one or other of us became too tightly coiled and turned in on ourselves, it repeatedly demonstrated the possibility of movement and growth. (Bridger, Personal note)

As Barbara Bridger states, the first lockdown in the UK in March 2020 found PartSuspended artist collective working on Spirals. The project started in 2013 and it is an on-going collaborative and interdisciplinary project that involves international female poets and artists, and brings together performance, poetry, video-work, music, live performance and public intervention. As the artist collective describes on their website:

Spirals is a poetic journey that crosses geographical borders and unites European female voices in an exchange of languages, cultures, personal narratives and modes of expression. Through the symbol of the spiral, the project explores thresholds, migration, path, nature, home and sense of belonging; the spiral acts as a sign of becoming, transforming and awareness. Poems written by contemporary female poets, recorded material, music and movement are part of a series of performances, photography and video-work. Women create and walk on spirals in a variety of places, such as London, Broadstairs, Coventry, Barcelona, Athens and Belgrade. Traces of care, joy, pain, friendship, womanhood, decay, imaginings, betrayal, frustration, time and love are left behind.

Folding and Unfolding.

Spiralling and waxing. Spiralling and waning.

Spiralling and resolving. Spiralling and transforming. (Spirals)

For this project, the collective has collaborated with contemporary female creators: poets, performers, musicians, video-makers, and has created video-poems based on the symbol of a spiral and female poetry. The filming has taken place in a variety of spaces and countries, such as the ruins of Coventry Cathedral in the UK, a derelict textile factory in Spain, the backyard of the Kulturni Centar in Serbia, a ruined open-air theatre in Greece. Thus, after the first two performances on the project Spirals: Eternity (2013) and Spirals: Galaxies of Women (2017), both filmed and presented in London, the next step of the poetic journey was Spirals: Genesis (London 2017) based on poems by Catalan poet Noèlia Díaz Vicedo, and in 2018 the project moved to Barcelona where Beatriz Viol’s poetry developed Spirals: Tracks for Finding Home. In the same year, Hari Marini’s poems were taken as part of Spirals: 28 Paths of Her performed and filmed in Broadstairs (United Kingdom), and the city of Athens was the location for Spirals: Flamingo by Greek poet Eirini Margariti. In 2019, Barbara Bridger’s poems for Spirals: As If were filmed and performed at the old Coventry Cathedral that was bombed by the Blitz in 1940 and in the same year Belgrade poet Ana Rodic produced the project Spirals: Autoportret.

Spirals is a multi-layered project that invites a range of interpretations, given its fluidity regarding collaborative methods, spaces employed and public engagement. However, the central role that each location plays forms an important parameter in the performance making. The creative use of city-spaces through the symbol of a spiral emphasizes the idea that cities are an ever-changing and shared space. As the urban geographer Tim Hall asserts: “[T]he only consistent thing about cities is that they are always changing” (1). Besides, within the shifting urban environments, the project emphasizes women’s experiences of spaces and time and invites artists and audience to engage with female artistic work that goes beyond geographical borders. The feminist geographer Doreen Massey suggests that “[t]he identities of place are always unfixed, contested and multiple” and she claims: “the particularity of any place is . . . constructed not by placing boundaries around it and defining its identity through counter-position to the other which lies beyond, but precisely (in part) through the specificity of the mix of links and interconnections to that ‘beyond’” (5, italics in the original). In this way, place can be considered as “open and porous” (Massey 5). The Spirals project’s engagement with a variety of places showcases the plurality of city-spaces and voices as well as the links between them, and thus, emphasizes the power of “going beyond” (geographical, cultural, linguistic) boundaries and revealing the porosity of places—in Rosi Braidotti’s words: “[T]he frequency of the spatial reference expresses the simultaneity of nomadic status and the need to draw maps; each text is like a cap site” (47).

As Braidotti states, the nomadic subject can only be manifested through the connection with the other from different forms, therefore, this movement that breaks the linear form of subjectivity at the same time constructs another new form of interaction that can only be circular, particularly in the shape of a spiral. The female artists of PartSuspended move and create spirals as a form of expanding the boundaries of culture. The circular movement and shape of a spiral connects to the basic notion of the concept of becoming foregrounded in the process of becoming. Braidotti has stated in her book that the philosophical interest subjacent to such configuration results from the attempt to bridge the existent void between the personal experiences of the feminine subject and the way in which this subject is represented.

Taking biographical events of her own experience as a migrant and as a polyglot, Braidotti explores theoretically the discourses of sexual difference in relation to the formation of the subject and tries to provide the necessary points to destabilize the monolithic aspects of the subject, conceptualized by patriarchal tradition as masculine, from a European feminist perspective. Thus, Braidotti, who follows a creative approach to theoretical thought and writing, as we have seen above, refers to the concept of “nomadic subject” not as a fixed framework that determines space and time but as what she has conceived as a “navigational tool” (18) that allows the exploration from the multiplicity, interconnectedness and circulation of the female subject. In this sense, the parameters of the “nomadic subject” sustain the theoretical and creative aims of the project Spirals, providing an alternative form of approaching “the other,” of collaborating and creating differently and this point became essential, as we shall see below, during the period of lockdown for the possibilities of productivity and creation.

Through the symbol of a spiral, the project underlines how opposite lands meet; how time is linked to the cyclical movement of exploration, migration, discovery, path and nature; and how we can open a common space for dialogue and sharing through multimedia, performance and poetry. The female creators make their presence visible either through their physical actions or voice, challenging the prevailing narratives of cityscapes. The project has been presented in a variety of forms and places. It fosters collaboration and creativity across art forms and reinforces the value of sharing, transforming and reconnecting. This has proven particularly important under the challenging circumstances of the COVID-19 pandemic when physical contact and live interaction had to be halted. In the following section, we will discuss how care and hope were reframed and re-emerged as significant elements of our practical work during the pandemic.

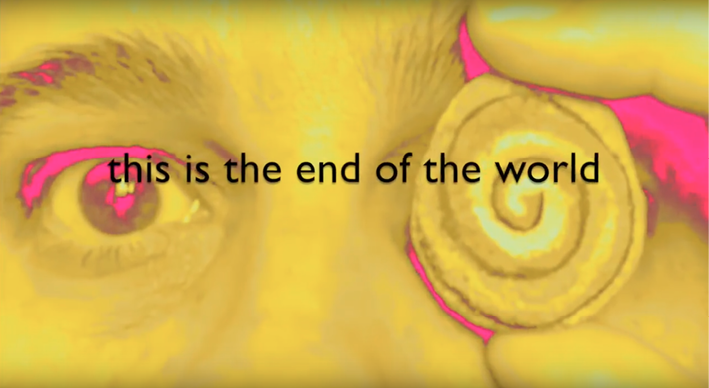

Fig. 3. PartSuspended, SPIRALS: Turning Points (London, Dorset, Athens, Agost), 2020, https://youtu.be/Vcp4Dt4_e_Y, © PartSuspended.

If we turn our gaze to the more distant future, the future which is unknown both to you and to us too, we can only tell you this: when all of this is over, the world won’t be the same. (Melandri)

In her article “A Letter to the UK from Italy: This Is What We Know about Your Future,” published in March 2020, the Italian novelist Francesca Melandri warned the rest of the world about the consequences of living under the condition of COVID-19 lockdown that was spreading fast globally. Repetition, isolation, grief, rage, and despair would appear a few months later in the UK as well as in other countries in Europe and the rest of the world. The dystopian landscape, the fear, the uncertainty about the future and death had shaded our lives. In many instances, public health institutions were unable to handle the crisis caused by the COVID-19 outbreak. Migrants, minorities, and low-paid workers who had been greatly affected by the crisis had often been left without support (Zarkov). Women and children were exposed to domestic violence. Surveillance and police violence increased in an effort to enforce measures that ensure safety in public space (Honey- Rosés et al.). We mourned the death of millions of people,[1] whilst it felt like that the world would not and possibly should not be the same.

Within this dystopic landscape, unable to meet in person or intervene in public spaces, PartSuspended had to rethink their way of working and to reassess the value of their artistic work. What could collaborative performance work offer and communicate about/in this critical period? What could artistic collaboration and expression tell us about the tension between hope and despair? How could female artists express their visions and help us imagine a brighter future? The core of PartSuspended artist collective—Bridger, Díaz Vicedo, Kalogeropoulou, Marini—held regular meetings every week to reflect on their work under these unprecedented circumstances and they were often accompanied by other artists such as Tuna Erdem and Seda Ergul,[2] Alessandra Cianetti,[3] Nisha Ramayya.[4] Holding this virtual space open and supportive was vital in order to create a sense of belonging. Artistic creation seemed to have been displaced by a more urgent form of survival: care. Caring for one another shifted from an intuitive response to the crisis to a source of artistic inspiration.

In times of crisis, the need to incorporate the notion of care into artistic work is imperative. Artist, activist, Professor of Contemporary Performance at Queen Mary University of London and co-founder of Split Britches[5] theatre company Lois Weaver, has been making performance work and developing feminist performance methodologies by considering “care” as a fundamental gesture of her work. In the last two decades, projects such as Long Table (initiated in 2003), Porch Sitting (initiated in 2012), Care Café (initiated in 2016)[6] have been added to the outstanding body of her performance work. In these projects, Weaver has devised participatory performance structures that encourage open-ended discussions and activity formats, underpinning “the interconnection of disparate peoples and places through the principle of care and gathering” (Weaver and Maxwell 88). Her work is formed by the need for care for both performers and participants, which also shapes the aesthetics of the performative actions and the structure of the written text. For Weaver caring is a radical act as she states:

Care has become a central component to my practice, performance and research in recent years, made necessary in part by age (as I approach my seventies), by the aftermath of stroke (in case of my performance partner, Peggy Shaw), and by the need to respond to hierarchies, systems and global events that render “caring” a radical act. (87)

The tension derived from the unparalleled situation of the global crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic was gradually considered as a call for artistic action by members of the collective. Not only were there moments of sadness, anger, frustration, but also ones of reflection, laughter and hope. An essential exercise on memory and embodied position certified the subject’s mortality, the importance of living together, the necessity of unity, the power of shared experience. Furthermore, despite awareness of the spatial reference, the meaning of borders—geographical, political, cultural—was contested in a tangible way as Rebecca Morelle stated: “[T]he virus doesn’t respect borders, or nationalities, or age, or sex or religion.” It was also a reminder of the looping forms of ecological systems and “how all organisms and substances are inextricably linked on our planet” (Spalink and Winn-Lenetsky 2).

Whilst the world population “entered a new age of contagion, social suspicion and anxiety” (Spalink and Winn-Lenetsky 1), the impact of less CO2 emissions on the environment and the air pollution decline was evident in many parts of the world. The quietness of streets and city-spaces made cities less hostile places for birds and wild animals who made their appearance in urban landscapes as well as in waterways (“Coronavirus: Wild Animals”). In addition, green outdoors spaces in cities attracted people’s attention and appreciation, as they were often part of their daily walks. Parks, gardens, trees offered citizens a way to find comfort and inspiration. The possibility of shifting spaces from indoors to outdoors opened up a possibility for re-discovering natural landscapes and their potential creative inspiration, also unveiling the nomadic subject’s relationship with the earth as transitional and defined by passages “without predetermined destinations or lost homelands. The nomad’s relationship to earth is one of transitory attachment and cyclical frequentation: the antithesis of the farmer, the nomad gathers, reaps, and exchanges, but does not exploit” (Braidotti 60).

With regard to climate change and ecological and political dilemmas, the COVID-19 outbreak also inspired discussions on the concept of “dark ecology” as another source of artistic possibility based on the emergence of hope. Angenette Spalink and Jonah Winn-Lenetsky point out that this term could address “the tension between desiring to feel hopeful about the future while simultaneously believing this hope to be naïve” (1). In this sense, the concept of hope and its possible implications on the situation and feeling of uncertainty became another fundamental point that not only emerged as a matter of discussions among the members of PartSuspended but also was placed at the heart of practical experimentations during the pandemic period.

The results of such artistic practice were displayed in the video-production Spirals: Turning Points.[7] The raw material used for this work gathered images of domestic spaces, sky perspectives, images of nature, etc. filmed during the first quarantine. The fragmented shots included a flock flying and shaping patterns in the sky in Agost (Spain) filmed by Noèlia Díaz-Vicedo; Barbara Bridger filmed the yellow lilies growing in her garden in Devon (United Kingdom); Georgia Kalogeropoulou filmed the thin lines of a spider web being intertwined with the railing in her balcony in London (United Kingdom); and Hari Marini filmed the trees on a mountain close to Athens (Greece). The progression of such images of hope and serenity were intersected by the following phrases that were heard in different languages (English, Spanish, Turkish, Greek) and repeated throughout: “This is the end of the world, as you, we knew it. I cannot hug you. I will hug you.” Apocalyptic words that reflected a pessimistic, dystopian and gloomy landscape anticipated an end but the visual images of nature and the last phrase “I will hug you” implied the possibility of a new beginning and human contact; a chance to change. Although the fear of the unknown and uncertainty foregrounded the production and had an impact on emotional, professional and creative life, the need to remain active artistically, to keep observing the reality and to communicate through work persevered and guided PartSuspended thoughts, desires and practical explorations.

Uncertainty can lead to despair and hopelessness; it can provoke suffering. However, it also implies the possibility of change; a change that can bring alternative perspectives on both creation and thought. It can be considered as a fissure that allows things to be open, to be in process, to be unfinished and questionable. Uncertainty hides within itself the seed of hope. As Rebecca Solnit claims,

Hope locates itself in the premises that we don’t know what will happen and that in the spaciousness of uncertainty, you recognize that you may be able to influence the outcomes—you alone or you in concert with a few dozen or several million others. Hope is an embrace of the unknown and the unknowable, an alternative to the certainty of both optimists and pessimists. (14)

Members of PartSuspended embraced this moment of uncertainty without dismissing the destruction and suffering that this period provoked. As Solnit specifies, “[i]t’s important to say what hope is not: it is not the belief that everything was, is, or will be fine. The evidence is all around us of tremendous suffering and tremendous destruction” (13). Experiencing and practising during such a dark period entailed suffering, but also demanded a greater effort in focusing on the function of artistic work as a celebration of human contact and empathy. Uncertainty and instability provoked periods of writing, dreaming, and laughing, as well as periods of silence and reflection. The sense of time and space felt at times compressed and at others expanded. Moments of praising life were followed by moments of frustration. In keeping active the artistic production and developing strategies for practical work not only envisioned an adaptation to the current reality but also fuelled hope for collective actions. Collective actions entail subversiveness, understanding, but also joy, in Braidotti’s words: “[T]here is a strong aesthetic dimension in the quest for alternative nomadic figurations, and feminist theory, as I practise it, is informed by this joyful nomadic force” (29). Uncertainty became a crack from which care and hope could spring through images and words spiralling in a continuous motion.

Georgia Kalogeropoulou wrote the following poem about the power of words that describes the transitory experience that the collective was experiencing and the potentiality they granted to these words and the images that they could create. This potential force, envisioned in the spiralling motion of the rhythm of the poem, concedes to the poetic word the power of ritual, thus connecting one another in a vital and creative way:

The power of words

The power of community

The power of us getting together and connecting our voices

The power of ritual

Turning our rage into a powerful signal

Having trust and faith to each other

Keep going

Don’t stop now

(Kalogeropoulou)

Although confined and limited to exclusively inhabiting domestic space, the collective managed to create a virtual space by using technology, in which each one of the artists could co-exist not synchronically but diachronically through filming, editing and making video-works. For the video-work Spirals: Turning Points created during the first lockdown, PartSuspended compiled texts, images, videos, music taken from the “Diary of Quarantine Dreams” collectively generated through assembling night dreams during the quarantine. Following on from the work Turning Points, PartSuspended produced a second video entitled Spirals: Breath, which was created during the second lockdown. This second piece of work engages intrinsically again with the written word produced mainly during online interaction.

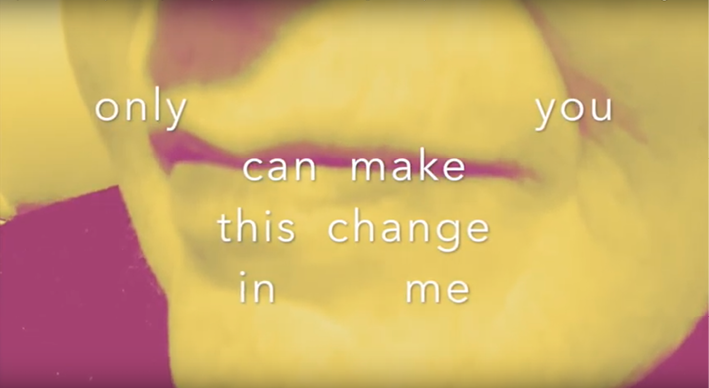

In the video-work Spirals: Breath, the following poem written by Barbara Bridger is entwined with the phrase “Breathe in. Breathe out. I cannot breathe. She cannot breathe. He cannot breathe. They cannot breathe. We cannot breathe. Last breath. First Breath.” Bridger’s poem was created after a Zoom meeting in which the collective reflected on the consequences of considering breath (as well as touch) as one of the main bodily functions that helped spread the COVID-19 virus. In this poem, Bridger relates to the act of laughing as a reactionary moment against uncertainty and the need to display that, despite the dystopic landscape that surrounded the times of lockdown, the quest for points of transfiguration could also be shared as moments of joy.

Written in memory of our laughter

LAUGHTER

we open our mouths wide

throw our heads back

bare our teeth

and bark out bursts of breath

we laugh

and share what’s deep inside us

with another

face to face

but then comes a time

when we must stop

we step back

and lower our masked heads

we’re waiting

waiting with baited breath

waiting

until we can laugh again

(Bridger, Poem)

Fig. 4. PartSuspended, SPIRALS: Breath (London, Dorset, Athens, Agost), 2021, https://youtu.be/YfvSeDlZkUE, © PartSuspended.

This sense of uncertainty mentioned above, inevitably fragmented the basis of the existing structure of the PartSuspended collective and their particular experiences as female subjects. The discontinuity inherent in the female subject between body, space and language is one of the key aspects of the project Spirals. As mentioned earlier, each one of the Spirals productions took place in a specific space and in a particular country. This cartographic precision anchors the position of the female subject within the public spaces of cities and within the multiple polyphony of European languages (Spanish, English, Greek, Catalan and Serbian). Therefore, language connects the images, the movement of the body, the music, the particular experience and the world, the synchrony of the female subject in relation to the body and the diachrony in relation to the cultural and social history of their subjectivity. In this sense, the construction of each one of the spirals is set up in an embodied motion that grounds the intersection between subjectivity and desire, intertwined in a constant process of becoming inwards and outwards, forward and backwards, along and through the shape of a spiral into a movement that Braidotti has suggested as nomadism: “[N]omadism is about critical relocation, it is about becoming situated, speaking from somewhere specific and hence well aware of and accountable for particular locations” (15). Thus, the limits of language and the specific experiences located in different geographical points provide an awareness of “difference,” which, along with this embodied motion, aims to discard any precepts of essentialism or homogeneity embedded in the female subject and considers the body as a repository of multiplicity within the dynamics of space, time and words. Braidotti has stated that the nomadic concept of the body has to be considered “as a threshold of transformations” and transcends any essentialist vision when she defines it as “multifunctional and complex, as a transformer of flows and energies, affects, desires and imaginings” (25).

Research on the proliferation of an embodied subjectivity is not exclusive to Braidotti’s thought. It is, in fact, one of the main concerns of the feminist thought of sexual difference, which she takes especially from Luce Irigaray’s particular understanding. The intersection between body and language conforms to the ideological dialectics that has shaped Western feminist thought throughout the twentieth-century. Among the most important theorists who have dealt with the interaction between body and language in writing are Monique Wittig (1992) and Judith Butler (1990). From a more symbolic perspective there are the theories of écriture féminine provided by Luce Irigaray (1977, 1984, 1989) and Hélène Cixous (1976), Julia Kristeva (1981) or de Lauretis (1990). Derived from such figurations, Italian feminism of sexual difference also dealt with sexual difference but prioritized practice over theory, as a collective form of thinking and acting, as seen in groups Diotima (1987, 1996) and Libreria delle done di Milano (1990) with philosophers Luisa Muraro and Adriana Cavarero, who later on would leave the group, as main figures. They foreground their understanding on Luce Irigaray’s thought and developed their theory about the reconfiguration of the female subjectivity based on what they have called “The Theory of the Socio-Symbolic Practice” elaborated in the book Sexual Difference: A Theory of Social-Symbolic Practice published in 1990, translated and edited by Teresa de Lauretis.

The consequences of isolation and the experience of lockdown had specific configurations for the female subject. As the graphics and surveys have already stated, women have seen their cultural, social and political activities diminished and unequally preserved in reference to their male counterparts. Thus, is it safe to state that to some extent women have been confronted with their own past, present and future from the very specific point of their embodied subjectivity? The synchrony of the living being that is not able to inhabit the public space resonates with the cultural, and even moral perceptions of women historically locked within the domestic sphere. The socio-historical present for women during the lockdown period acquired a specific form of oppression and trauma that directly confronted their subjectivity with the socio-historical past. The Spirals project interweaves and inhabits public spaces in the city in order to re-create gestures, movements that re-formulate female subjectivity. Thus, there was a need to rethink the project of Spirals while confined within the domestic space and to reassess the implications of a bodiless form of artistic relation.

Members of PartSuspended decided to take action and open up their fears and concerns towards the other. The unpredictability of the future, the fear of the unknown and the sense of feeling lost triggered this need to communicate to the other through the regular virtual encounters they held. Language was at the centre of such action and offered possibilities of an alternative narration of the self that soon was perceived as an act of creation. The complex diversity of nationalities in the group (Greek, English and Catalan-Spanish) reveals the capacity of language not as a mere tool of communication but as “a site of symbolic exchange that links us together in a tenuous and yet workable web of mediated misunderstandings, which we call civilization” (Braidotti 40). Language thus became the medium between female subjectivity and the world, even though this world seems to be at its very end as seen in the Spirals: Turning Points section.

At the very heart of this tension between the enforced isolation of the subject and the political and social context, a particular form of desire emerged. To avoid the fragmentation of a specific female desire that opens up towards the other as a member of a specific collective, the female artists of PartSuspended excavated within their dreams through language and collected a “Diary of Quarantine Dreams” where they formulated and elaborated an alternative narrative of themselves. The need to move beyond such fragmentation lies at the very heart of the concept of difference in the sense that it is precisely such difference that drives one member of the group to the other—never as an isolated subject but rather in connection with the collective as a nomad that incarnates

the intense desire to go on trespassing, transgressing. As a figuration of contemporary subjectivity, therefore, the nomad is a postmetaphysical, intensive, multiple entity, functioning in a net of interconnections. She cannot be reduced to a linear, teleological form of subjectivity, but is rather the site of multiple connections. She is embodied and therefore cultural. (Braidotti 66)

The fissure and imbalance between symbolic forms of collective references and the individual embodied experience needs to be overcome by allowing desire to flow, to move around from one female subject to another, echoing Braidotti’s understanding of desire as the centre of multiple identity. In this sense she has stated that “desire is productive, because it flows on, it keeps on moving, but its productivity also entails power relations, transitions between contradictory registers, shifts of emphasis” (41). This is particularly relevant to understand the kernel of PartSuspended’s work, and particularly the substratum of Spirals. By considering PartSuspended’s personal experiences, dreams and emotions as the basis of their creativity and their particular form of overcoming uncertainty, the collective provided the ground whereby they could stand and move forward with confidence despite the situation.

Fig. 5. PartSuspended, SPIRALS: Turning Points (London, Dorset, Athens, Agost), 2020, https://youtu.be/Vcp4Dt4_e_Y, © PartSuspended.

This article has examined artistic collaboration and unity in times of crisis through its exploration of the project Spirals developed by PartSuspended. Having determined their modus operandi through practice-as-research, the epistemological grounds of Spirals is situated in the continuum line of becoming through the symbol of a spiral. This line needs to be thought of and conceptualized as a continuous motion that encounters and approaches “the other.” Only by accepting the power of co-existing can the multiplicities and dynamism of the becoming of the female subject through Spirals be considered. As has been explored, the vicissitudes of an enforced isolation due to the pandemic situation emerged in the form of envisioning the configuration of the space in-between and of how to create together without the physical presence of the other. The continuity of the project Spirals was thwarted due to the impossibility of inhabiting and intervening in public spaces. However, this challenge ultimately inspired their work, resulting in new modes of working and outcomes, such as Spirals: Turning Points and Spirals: Breath.

We have seen how the artistic implications of this project had to be reformulated through alternative forms of virtual meetings through the lockdown period. As female artists and creators, the decision to engage more deeply with the purpose of searching for a multiform existence provided a diverse participation in the world. The action of opening each other up both creatively and personally through the concept of care bridged the feeling of uncertainty with the possibilities of restructuring the fragmented female subject. This has been possible by establishing the perspective of sexual difference as the point of departure for discussing the creative practice in Spirals. By mobilizing Braidotti’s concept of the “nomadic subject,” this article has explored this process of becoming based on the embodied motion of a spiral. The desire to create and communicate through images, sound and language has been essential for creating in collaboration. This has been the key to keeping the project running during times of crisis, and thanks to the mediation of technology, the female body and the interaction with language has shaped the motion through a spiral, allowing PartSuspended to reshape their map of action and move beyond the essentialism inherent in their historic and artistic condition.

Braidotti, Rosi. Nomadic Subjects: Embodiment and Sexual Difference in Contemporary Feminist Theory. Columbia UP, 2011.

Bridger, Barbara. Personal note. 19 May 2021.

Bridger, Barbara. Poem: Laughter (Part of SPIRALS: Breath). 17 Dec. 2020.

Bridger, Barbara, Georgia Kalogeropoulou, Hari Marini, and Noèlia Díaz Vicedo. “On Spirals.” European Journal of Women’s Studies, vol. 29, no. 1, 2022, pp. 155–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/13505068211068611

Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble. Routledge, 1990.

Cixous, Hélène. “The Laugh of the Medusa.” Translated by Keith Cohen and Paula Cohen, Signs, vol. 1, no. 4, 1976, pp. 875–93.

Conquergood, Dwight. “Performance Studies: Interventions and Radical Research.” The Performance Studies Reader, edited by Henry Bial, Routledge, 2004, pp. 311–22.

“Coronavirus: Wild Animals Enjoy Freedom of a Quieter World.” BBC News, 29 Apr. 2020, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-52459487, accessed 30 May 2021.

de Lauretis, Teresa. “Eccentric Subjects: Feminist Theory and Historical Consciousness.” Feminist Studies, vol. 16, no. 1, 1990, pp. 115–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3177959

Diotima. Il pensiero della differenza sessuale. La tartaruga, 1987.

Diotima. Traer al mundo el mundo: objeto y objetividad a la luz de la diferencia sexual. Translated by Maria Milagros Rivera Carretas, Icaria, 1996.

Etchells, Tim. Certain Fragments: Contemporary Performance and Forced Entertainment. Routledge, 2003. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203449639

Hall, Tim. Urban Geography. Routledge, 1998.

Haseman, Brad. “A Manifesto for Performative Research.” Media International Australia Incorporating Culture and Policy, vol. 118, 2006, pp. 98–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X0611800113

Heddon, Deirdre, and Jane Milling. Devising Performance: A Critical History. Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

Honey-Rosés, Jordi, et al. “The Impact of COVID-19 on Public Space: A Review of the Emerging Questions.” OSF Preprints, 21 Apr. 2020, https://osf.io/rf7xa/, accessed 30 May 2021. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/rf7xa

Irigaray, Luce. Ce Sexe qui n’en pas un. Gallimard, 1977.

Irigaray, Luce. “Equal to Whom?” Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, vol. 1, no. 2, 1989, pp. 59–76. https://doi.org/10.1215/10407391-1-2-59

Irigaray, Luce. Ethique de la Difference Sexuelle. Minuit, 1984.

Kalogeropoulou, Georgia. Untitled poem in “Collaborative Writing on SPIRALS during the COVID-19 Lockdown” by PartSuspended. Covid and the Woman Writer Conference, 30 Apr. 2021, Institute of Languages, Cultures and Societies, School of Advanced Study, University of London.

Kershaw, Baz, et al. “Practice as Research: Transdisciplinary Innovation in Action.” Research Methods in Theatre and Performance, edited by Baz Kershaw and Helen Nicholson, Edinburgh UP, 2011, pp. 63–85. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780748646081-006

Kristeva, Julia. “Women’s Time.” Translated by Alice Jardine and Harry Blake, Signs, vol. 7, no. 1, 1981, pp. 13–35. https://doi.org/10.1086/493855

Libreria delle done di Milano. Sexual Difference: A Theory of Social-Symbolic Practice. Translated by Teresa de Lauretis, Indiana UP, 1990.

Massey, Doreen. Space, Place and Gender. U of Minnesota P, 1994.

Melandri, Francesca. “A Letter to the UK from Italy: This Is What We Know about Your Future.” The Guardian, 27 Mar. 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/27/a-letter-to-the-uk-from-italy-this-is-what-we-know-about-your-future, accessed 30 May 2021.

Morelle, Rebecca. “Why India’s Covid Crisis Matters to the Whole World.” BBC News, 28 Apr. 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-56907007, accessed 30 May 2021.

performingborders. performingborders, https://performingborders.live/, accessed 25 July 2023

Queer Art Projects. Queer Art Projects, https://www.queerartprojects.co.uk/, accessed 25 July 2023.

Solnit, Rebecca. Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities. Haymarket, 2016.

Spalink, Angenette, and Jonah Winn-Lenetsky. “Introduction.” Performance Research, vol. 25, no. 2, 2020, pp. 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/13528165.2020.1752570

Spirals. PartSuspended, https://www.partsuspended.com/productions/current/spirals/, accessed 25 July 2023.

Split Britches. Split Britches, http://www.split-britches.com/, accessed 25 July 2023.

Weaver, Lois. and Hannah Maxwell. “Care Café: A Chronology and a Protocol.” The Scottish Journal of Performance, vol. 5, no. 1, 2018, pp. 87–98. https://doi.org/10.14439/sjop.2018.0501.09

“WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard.” WHO, https://covid19.who.int/, accessed 30 May 2020.

Wittig, Monique. The Straight Mind. Harvester, 1992.

Zarkov, Dubravka. “On Economy, Health and Politics of the Covid 19 Pandemic.” European Journal of Women’s Studies, vol. 27, no. 3, 2020, pp. 213–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350506820923628