https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8553-7517

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8553-7517

University of Lodz https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8553-7517

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8553-7517

The following article explores the creative collaborative practices in digital poetry between more-than-human agents. Richard A. Carter’s artistic project Waveform (2017–) makes one reconsider the ways in which multimodal and web-based encounters of image, word, sound and movement, and, in the case of Carter’s airborne drone, also the political and military, redefine “a literary text” via nonhuman extended perception. Drone-generated poetry challenges a human-centered (literary) perspective, raising questions about AI’s creativity and code’s generative and aesthetic, and not only functional, potential. The article, drawing upon Raichlen, introduces a comparative platform of waves’ mechanics to render the complexity of multimedial digital poetic writing. The focal analytical material provided by Carter results from the (human, machine) vision (of the moving waves) translated into words, generated by the drone, and edited by the human. The article studies the creative process in which the collaboration between more-than-human entities, as its outcome, produces poetic work of artistic value and literary merit.

Keywords: digital literature, drone generated poetry, waves, computer code, multimodality

The way in which waves are generated bears semblance to algorithmically generative writing. Complicated mathematical equations capture the allegedly whimsical and unpredictably wind-propelled pattern of shallow and deep water waves. These calculations comprise numerous variables, such as the inshore and offshore wave length and height, the gravity’s speeding up, the amplitude of the wave’s peak, the heaviness of the fluid, to end up with the air concentration and the quickness of water particles moving in a given direction (Raichlen 1–10, 219). Made of the same particles as any other physical entity, the ocean becomes the interface for textual, aural and mobile wave patterns. Fredric Raichlen in his technical study Waves explains that the wind’s shifting particles and their pressure make waves appear on the surface of water, animating them with wind’s intensity and causing their further movement (18). The scientist observes: “The sea surface appears as if a number of waves with different amplitudes, frequencies, directions, and phases were superimposed, resulting in a relatively random variation of the water surface elevation and the wave lengths” (20). Digital writing’s equations are no less perplexing. On the one hand, the electronic work is usually, as stressed by the genre’s theorists, an outcome of multimodality, combinatorics, interactivity, hypertextuality; on the other hand, there are collaborative practices, a code and algorithms that co-create the digital writing by a random selection of lexical elements. In digital literature, the text cannot simply be approached on its own, taken out of its aquatic online environment. Routinely, images come before the lexia, and the basic units are words and not entire sentences or narratives (Naji, Digital Poetry 67). Moreover, as shown by Bell et al., in digital writing, the scope of analyses is much wider, it encompasses visuals and auditory, hyperlinks and the language of programming: in other words, all the aforementioned “different amplitudes, frequencies, directions and phases.” The internet, as digital literature’s “watery” fluctuating milieu, avails of the technical options transcending print’s limits, at the same time expanding the text’s cognitive and artistic values. Detached from its online medium, digital poetry, as rightly noted by Bell et al., would not be able to perform the whole spectrum of its creative functions (“A [S]creed for Digital Fiction”). Taking this into account, Hayles in her canonical study Electronic Literature emphasizes how much the development of the titular web-based mode of creative expression has changed readers’ understanding of what a literary text might mean and how it is (collectively) generated (4). Further, digital writing invites readers to co-create a text composed by and large of experimental, discontinuous sentence structure and volatile recombined lexicon (Funkhouser 4–6). As a result,

[v]iewers experience a co-ordination of text (text being broadly defined so as to include images, sounds, objects), sometimes indeterminate, sometimes non-linear, and often interactive. As a poetic form, language crafted by mind and machine (through code, and also a language) predominates, and non-verbal elements also create affect and responses translatable into words. (Funkhouser 225)

Bearing the above in mind, in Analyzing Digital Fiction, Alice Bell et al. refer to electronic writing as a form of cooperation and exchange. In other words, editors underline dialogic interactions between the digital environment in which writing is generated and textual practice’s (wave)form, interpretation(s) and methods of creative signification (“From Theorizing to Analyzing Digital Fiction” 4). Such a stand reinstates a more-than-human position of digital “water” exchanges, empowering them and making them agentic. Wave generation process also involves the collaborative action of wind, sun, sometimes water currents, and sand exchange. As regards wave-forms, Raichlen proves that although waves may seem from the shore to be “a random distribution of wave amplitude and wave length” when studied collectively in clusters, they in fact turn out to be structured by a mathematical formula, not being, at the same time, human regulated or controllable (27). Similarly, it is the collaborative and group dimension of literary practice that distinguishes digital writing. In addition, onshore waves observation depends upon the shifting place of the spectator/s, hence allowing a profusion of view(ing) points.

The following article examines Richard A. Carter’s poetic work Waveform (2017–). At first the project consisted of a series of drone-captured waves images, followed by machine-generated poems in print, which finally evolved onto a 10-minute online film (2019).[1] The aim of the analysis is to explore how the collaboration between sensing machine, software and human enabled the production of a poetic multimedial outcome of an aesthetic quality. The article locates Carter’s project within the current debate on drones, especially in the context of the ongoing war in Ukraine. The final section is dedicated solely to a close reading of drone-generated poems. The unifying point for all the parts is the informative monograph on oceanic waves written by the coastal scientist Fredric Raichlen.

In the ocean, waves’ onshore distribution is always accompanied by their dispersal and the apparent loss of energy being regrouped in different formations. Some literary currents, as proved by Rettberg, also remain regrouped to give origin to new waves. In his study, Electronic Literature Rettberg traces the roots of digital literature back to the experimental practices of kinetic poetry, Dadaism, Surrealism, modernism and Fluxus, to name but a few. On the intertextual level, Carter’s Waveform evokes intertextual and aquatic associations with the modernist prose of Virginia Woolf’s The Waves. Importantly, it is not the “theme” that links Carter’s Waveform with Woolf’s poetic prose but rather the writing technique. The waves’ particles, as Raichlen argues, do not move in a linear or vertical direction, but in “an elliptical orbit with the major axis” whose diameter subsides (but never disappears entirely) when spinning in shallow waters (10–11). In Woolf’s writing, narrative linearity does not exist: instead there are numerous loops, twists and turns, flashbacks and flashforwards. In other words, Woolf writes “beyond words,” construing associations that are based upon sensory perceptions. Her stream of consciousness technique blurs the chronological and temporal framework of the wave-journal. The author’s writing thrives on excess that spills over the words like the waves’ spray (“The waves broke and spread their waters swiftly over the shore. . . the spray tossed itself back with the energy of their fall” [127]). Furthermore, Woolf’s text stresses the agency of wave-writing (“The waves massed themselves, curved their backs and crashed” [141]). Likewise, the narrative operates on all five senses: light and sound are particularly foregrounded (“The waves, as they neared the shore, were robbed of light, and fell in one long concussion, like a wall falling, a wall of grey stone, unpierced by any chink of light” [177)]). Woolf’s seascapes blur textual and perception divisions: (“Sky and sea were indistinguishable. The waves breaking spread their white fans far out over the shore, sent white shadows into the recesses of sonorous caves” [202]). Long twisted sentences meander like seaweed, breaking waves of images, colors, memories and recollections. Similar to Carter, Woolf mediates on how light merges with darkness, land with the sea and sounds with images. The rhythm of the sentences reminds one of the ebb and flow of the ocean. The “heaviness” of print is liquefied by the narrator’s own dissolution. Woolf writes: “. . . innumerable waves spread beneath us. I touch nothing. I see nothing. We may sink and settle on the waves. . . . Everything falls in a tremendous shower, dissolving me” (176). In The Waves, multiple viewpoints are also underscored: “. . . I saw but was not seen. I walked unshadowed; I came unheralded. . . . Thin as a ghost leaving no trace” (245–46). Digital authors and critics alike readily acknowledge their creations’ links with modernist legacy. No different in this case, referring to Woolf as one of the precursors of hypertextuality, Rettberg praises the writer’s innovative approach to narration based upon associative, shifting and fragmentary processes rather than causal narrative chains.

Seeking the grounds for textual online progression, and, at the same time, insisting upon an ontological difference between print and web language, Cayley in The Bloomsbury Handbook of Electronic Literature puts forward the thesis that literature is becoming digital because everything around us is becoming digital. On the other hand, Rettberg observes aptly that it is not technology per se that defines digital writing but the ways in which online literature relates to current artistic engagements, “networked practices and collaboration between agents unfamiliar to each other” (Naji, “The Art of Machine”).

In the case of machine-produced genres of literature, such as drone poetry, the system-engineering and the context of application draw special attention and still incite controversy. When poetry is generated by a reconnaissance machine and military weapon, then, readers are faced even with more questions than merely the issue of shared authorship or a machine’s creativity. The operation of drones over the last years has raised many ethical and legal dilemmas, most of which still remain unsolved. Chamayou in A Theory of the Drone emphasizes the fact that drones were originally designed as surveilling machines and not combat ones (28). Their main purpose was to observe, provide information and gather data. Chamayou claims that drones were compared to divine eyes, as they guaranteed unceasing and permanent watch (37). It was as late as in the Kosovo war that drones started to be used as assisting military weapons but targeting and killing directly did not begin until Afghanistan (28–29). In the military usage of drones, the territorial allocation is structured into the secure control zone and the operational enemy line (22). Such a binary division results in the further detachment of the body (the human) and the executor (nonhuman), the observing mind and the mobile machine agent (23). This split is probably the most frequently raised argument in drone debates (poetic and non-poetic) and Naji also refers to it in her analysis of Carter’s Waveform (Digital Poetry 60–61). What is more, the protocol for a drone’s vision in the army involves “kill boxes,” temporally sequencing the space into step by step operational procedures directed at the target (Chamayou 55). However, when a drone’s sensory data is turned into vision, one cannot recognize human faces on screen and only watches obscured silhouettes (117). This way, outcomes are dissociated from deeds and perception is mediated by the interface (118).

In Waveform by Richard A. Carter, viewers/readers are mediated by the tangible, moving and observing machine, the software designed, the text on the screen, the literary input, images and finally the soundscapes composed especially for the project. In “Drone Poetry,” Carter admits that due to his interest in sensory digital and textual milieu, he felt the need to explore more diverse interactions between the human and non-human world happening beyond human limits of perception. The viewpoint is always more-than-human because despite the fact that a drone’s movements can be controlled, their far-reaching aerial vision cannot be manipulated during the process of recording. Overall, this detachment, in art, is praised for deferring human-centeredness; in the military context, it is blamed for deferring human responsibility. Occasionally, these two aforementioned stances can overlap, generating a novel angle, as in the case of the Turkish drones Bayraktars.

Taking into account geo-political interactions, in 2022, the war in Ukraine tragically added a new dimension to the drone debate. Drones have been elevated to the symbol of the Ukrainian independence fight and, despite the earlier controversies, they have become the objects of a pop-cultural cult. Importantly, artworks have been dedicated to drones and not to the humans who operate them. Paradoxically, due to the efficiency and spectacular achievements during the first part of the war, drones have gained a widely-recognized agency. From merciless killers of military empires, they have become fighters for the good cause. Facing the overpowering Russian forces, when the war broke out, Bayraktars constituted the main Ukrainian military advantage. The song dedicated to them, “Bayraktar,” openly praises drones’ military potency (explosions, surveillance, setting fires) that managed to challenge the heavily armed Russian troops (“their inventory melted a bit,” “Their arguments are all kinds of weapons / Powerful rockets, machines of iron. / We have a comment on all the arguments”) and pays tribute to the effectiveness of drones’ direct combat from above (“He makes ghosts out of Russian bandits”). The authors of the lyrics created a legend of nearly autonomous machines that astonished everyone; “their tzar knows a new word”[2] and so did the rest of the world. The crowd-funding for buying Bayraktars turned into a symbol of other countries’ support for the Ukrainians. One could say that many anonymous civilians who contributed financially to this project have become a part of the wider (military and cultural) collaborative practice. It could be further speculated whether these new variables can contribute to the more favorable reception of drone-generated poetry. Regardless, it seems that Bayraktars have earned the subjectivity of machine-persons who act on their own. To some extent, nowadays, drones are perceived as nonhuman soldiers who write poems.

Carter’s multi-phased project Waveform originates with a drone registering the movement of the waves close to the Cornish beach. In “Waves to Waveforms,” Carter discloses the location as an unfrequented setting called “The Strangles,” one known for dangerous currents in whose vicinity underwater data cables were placed. The artist’s preferred drone-recorded imagery depicts the diverging bright and murky points of the encounter between the ocean and the coastal shore (“Airborne Inscription” 368). Central to his interest is exploring

. . . how varied phenomena become observable and expressible as data, through the convergence of specific sites of interest, technologies of sensing, and contexts and techniques of interpretation. This is a depiction of the “observable” not as the straightforward detection and recording of latent facts and measurements, but as emerging through a dialogue between multiple actors, both human and nonhuman. (Carter, “Waves to Waveforms”)

To code visual coordinates, Carter in “Airborne Inscription” admits that he has created software employing Processing operative instruments (368). The method is not unproblematic due to its altering shorelines and changing points of breaking waves (368). The algorithm designed by Carter transforms the digital data of what is movable and volatile into a differentiating line between light and darkness (368). Using the same program and earlier-gathered data feed, Carter has developed the software for teaching drone to generate literary texts of aesthetic values (“Drone Poetry”). The writing software seeks the recurrence rate of specific lexicon sequences and establishes most probable connections and collocations, but it is the algorithm that uses textual data to generate indiscriminate literary and imaginative output (“Airborne Inscription” 369). During this phase, Carter has fed program with wide-ranging publications[3] about aquatic worlds (first-hand experiences at sea, fiction and diverse epistemological viewpoints), such as the 19th-century voyage logs, nature philosophy and contemporary reflective works on the ocean expeditions. This way, a drone has learnt the sea vocabulary filtered through various outlooks, out of which it generated its own poems. The strategy, referred to by Funkhouser as “creative cannibalism” (231) or “mechanically consuming a text to give birth to new text” in the process of “shifting, combined realization,” means that “[e]xternal material is consumed, digested and restated as an altered entity” (230). With coordinates transformed into words, the drone in Carter’s work translates the visual data gathered during flights over waves into poems.

According to Funkhouser, digital literature’s non-biocentric and animate elements (or, as it is argued here, aquatic properties), can be almost limitlessly shifted and recombined due to their “plasticity” (4–5) but not loosely removed despite their apparent randomness or incompleteness, since all these volatile components are intertwined, forming “a type of organism” (3). Contrary to one’s assumptions, it is not the method of creation that defines electronic texts but the impact they produce on readers, and the a/effect, which, in the case of digital writing, is much more multi-directional and idiosyncratic (Funkhouser 213). In other words, it is the relationality of diverse more-than-human agents and media modalities that composes digital poetry. Hence, the co-operation, which is a common practice among different artists or/coders, also extends into the nonhuman realm. The collaborative practice is based upon a shared networked environment of human and nonhuman subjects, including AI. Moreover, as Zylinska argues, such linkages can be creative and original in their nature because “AI dreams up the human outside the human, anticipating both our desires and their fulfillment” (71). Apart from its technical indispensability, the digital medium, as argued by Bell et al., makes it possible for a text to fully realize its lexical, cognitive and theoretical potential, without which the text’s artistic and interpretative dimension would be, to a large extent, deficient (“A [S]creed for Digital Fiction”). Much in agreement with the above, Elizabeth Swanstrom in Animal, Vegetable, DIGITAL: Experiments in New Media Aesthetics and Environmental Poetics points out that code’s initial inconspicuousness and its purely technical function has expanded into an artistic dimension of the imaginative kind (19). Elaborating on this idea, Swanstrom writes: “This expressive type of code has a human audience and allows us to consider how computer code is experienced, that is, the manner in which it functions cognitively, affectively, and phenomenologically” (19). Likewise, she underscores the inventive materiality of code, emphasizing that expressive code (as she names it) can be identified as “creative, generative, and world-building” (52). The code’s regularity together with its unpredictable outcome corresponds to what Raichlen calls as “the pulse of the ocean” (37), that is, the ocean’s own fluctuating algorithm. Furthermore, Swanstrom argues that generated codes and that of nature do not differ in a conceptual sense, they are made of more-than-human modules, chemical, biological and non-biological data (52).

As argued in the article, the machines’ operational and originative role in the co-operative aesthetic exchange cannot be undermined and nor can their creativity: “The author/coder can control the structure of the text by controlling the lines of written code but she cannot, even in principle, control the execution or processing of those lines of code” (Strickland). Moreover, it is not only humans that are able to do programming: AI can code even beyond people’s scope of comprehension. With the above in mind, “code is the link between wetware and hardware, or human brains and intelligent machines” (Morris 8). As seen above, the differentiating line between aforementioned collaborative entities is as vague and blurred as the contrast between the land and the sea in Carter’s Waveform. Naji in her book Digital Poetry (2021) agrees with Hayles that “[w]e can no longer talk of the machine impersonally when we are, in fact, connected to and part of it, directing the flowing of digital data” (29). What is more, the critic diagnoses the decrease in human autonomy on behalf of the machine (Naji 84). It can be argued, though, that the aforementioned observation would not breed apprehension if one were to reject the “win or lose” undercurrent in the artistic (poetic) exchange, according to which more independence for the hardware /software necessarily means less freedom for the human (wetware). It is not as simple an equation as it may seem. The power balance is a shifting phenomenon: it depends upon changing circumstances but it does not have to be based upon the scarcity rule. More empowerment to the machine may turn out to be productive and inspiring for all parties as it opens a new, less human-centered, dynamics in their co-operation.

With regard to drone poetry, the aforementioned collaborative context takes the form of co-operative practice between a sensing machine (hardware) and a code or algorithm (software) and human (wetware).[4] On a declarative level, Carter in Waveform perceives a drone as an agent with which he declares to establish a dialogic network, and without which he would be left with nothing more than his own anthropocentric standpoint. Seen in this light, both parties participate in a mutual exchange because nonhuman sensory apparatus expands the scope of both human vision and perception. Carter’s professed motivation is “teaching a drone to write poetry,” but drones can also teach humans how to see, as their perspective is different than humans. Drawing upon Paglen’s work, Zylinska raises the question of seeing machines, stressing the fact that modern technology enables them autonomy in that sphere and that frequently their vision is not even human-directed (88).

At this stage, one needs to define the role of the human (wetware) in drone-generated poetry. This role is intentionally minimized but not entirely eliminated. Carter calls himself “a curator” and he does acknowledge his involvement in the process of creating Waveform (“Airborne Inscription” 367). Following this line of thinking, Rettberg observes that in the future humans will not be able to fully understand AI creative processes, and the poet’s role will be limited to becoming the machine’s editor. In Carter’s case, the very selection of the reading input already pre-determines to some extent the drone’s generating software stylistics. Moreover, the artist and a critic makes decisions regarding which of the drone-generated poems are going to be included in his artwork and which are not to be revealed to the general audience. Thus, in a way, he has already become a machine’s (drone’s) editor. The entire software, transforming visual images into poetic accounts, is designed by Carter so as to be disjoined from a human viewpoint as much as possible. He describes “writing with drone” as a poetic bilateral exchange, but one might wonder whether the author’s well-motivated intentions can suffice to reverse what is so deeply rooted in human culture, namely, the instrumental treatment of machines. Such an attitude, reinstated by common linguistic collocations, encourages people to “use machines” rather than “work with them.” Carter’s own account on “using a drone”—“as opposed to a conventional digital camera, I have sought to present a more explicit instance of an observing agent operating as part of a wider sensory and interpretative network, and so undercutting any notion of sensory systems as presenting a Cartesian ‘view from nowhere,’” he states (“Drone Poetry”)—does acknowledge the agency of the machine, but the verb “using” might be seen, to some extent, as weakening the participatory potential.

As argued above, Waveform project is not limited to the printed text and its existence is multimodal and multidimensional. Much in this vein, Hayles draws attention to what she defines as the “distributed” (hence collaborative) nature of digital poetry:

In digital media, the poem has a distributed existence spread among data files and commands, software that executes the commands, and hardware on which the software runs. These digital characteristics imply that the poem ceases to exist as a self-contained object and instead becomes a process, an event brought into existence when the program runs on the appropriate software loaded onto the right hardware. (“The Time of Digital Poetry” 181–82)

It is true that without understanding the materiality of the new media, the analyses of digital poetry make no sense, but neither do they when language’s creative and aesthetic function seems to be of secondary importance. Digital poetry resists being downgraded to pure text so as to avoid linearity and spatial anchorage annihilating the temporalities of the reading process which render words as “a line (resting) in space” (Cayley, “Time Code Language” 320). Without losing sight of multimodalities and the online environment, it is also worth considering a close reading interpretation of the drone’s poetic output, which the final part of this article is going to propose.

The printed version of Carter’s Waveform exhibits quite clearly the kind of interpretative losses one may have in mind. In print, the text of Waveform is indeed static and it does not compete for audience’s attention because waves and ocean images are equally immobilized in time. The role of the machine and code needs to be elaborately explicated in the opening essay as their presence is invisible on paper. The text, supported by latitude and longitude, seems to be stamped by a template that is dying away. Similarly, the ontologically split ocean is rendered on paper as if in diluted watercolors. As a result, print actually dominates and consumes the visuals which appear to create only the blurred background for the words. Printed pages seem to be lighter than the digital “dark” black and white textual event. The “mechanic” collaboration aspect is mellowed in print as the rounded drone-vision shapes are smoothed in comparison to the ragged edges visible on video. Golding aptly coins the phrase “transitional materialities” (252), referring to printed forms that, according to him, seem to go beyond the page in their readiness and anticipation of the digital realm, which might here refer to Carter’s digital and filmic version of his project.

As argued above, an online film medium has completely altered the dynamics of multimodality and the reception of Carter’s entire project. On video, viewers can look as if through the drone’s eyes, images and text are superimposed upon each other, like waves, erasing what comes before and after them. Michael Joyce reminds us that the digital text is “replacing itself” (236). The process can be compared to writing on beach sand: the signs become gradually washed away but the matter of the sand does not change.

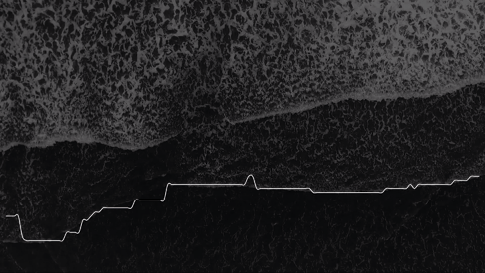

Raichlen argues that “the spectrum of the sea surface is much like the spectrum of light or that of sound” (22). In his poetic work, Carter acknowledges playing upon the dual meaning of waveform and wavelength, paying tribute to sensor-based technology (“Airborne Inscription” 371). He calls his work “a sensory assemblage” consisting not of “quantifiable data, but of poetic text” (372). The artist summarizes this as follows: “. . . the outlines of incoming ocean waves, and the genealogy behind the arbitrary waveforms of science and engineering, offer an intriguing point of contrast and critical reflection, with the former supplying an evident source of random values for generative writing” (372). Despite a somewhat regular and intrinsic pattern, in the Waveform video the procession of waves, textscapes and images remains to a large extent unpredictable but their stylistic (wave)form remains consistent. The recurrent stable triple configuration (the pixelated image; the arbitrary drone-delineated border, separating darkness from light, land from the shore, readers/viewers from the textspace, digital reality from text; and, finally, the code-generated poem) is not accompanied by any sound or movement effects. Poems are composed of one or two-word lines which are always fragments of the larger fragments, never creating a whole. The textscapes appear on screen in uneven intervals; sometimes the audience has to wait for them for a longer time, or to the contrary, one image rushes the other. Like waves, they unexpectedly appear to slow and speed up. Raichlen explains that “[s]ince water surface changes with time, at a fixed location, the water particles’ velocities also change with time. Therefore, there is an acceleration and a deceleration associated with a water particle when the wave passes” (13). In creating the fluctuating and mobile network, the readers/viewers’ control over the digital environment is put into doubt.

The black and white “drone vision” stylistics in which digital recording is set to a considerable degree amplifies estrangement. The waves recorded from above appear defamiliarized: they do not resemble the onshore-seen water formations. Paradoxically, virtual dizziness, which usually arises from waves’ more rapid movement, results from the aerial perspective applied when watching the images from above. The loud sound of breaking waves could not have been recorded by the drone; because of the noisy engine work, drones do not have audio recording devices. Nonetheless, some types of military drones (i.e. Predator and Reaper) can “hear” and understand the electronic transmitters of data, for instance from smart phones (Chamayou 41).

In Waveform, the sound, digitally processed, creates a completely novel audio-visual sensation. This “non-drone recorded” soundscape, generated by Mariana López, is heard on and off, as if dissolving the poems, like incoming waves, which appear transient and fast to disperse. The soundscape for the video is looped; after some intervals, it gets repeated endlessly. One can break this repetitiveness thanks to a distinct animals sound, i.e. squeals of the seagulls. Without this the artificial “natural” acoustic clue, it would be nearly impossible to perceive this recurrent audio pattern. Additionally, the audience interactively can “like” or “share” the video and provide the immediate feedback to the artist. Moreover, the video can be stopped at any time or zoomed or rewound.

While watching the video, the pixelated waves remind one that it is not human vision. They appear when the film stops to make room for the textscape; then the sea becomes their interface. The more-than-human perspective brings into focus the overlooked fact that people are not the only observers in the world. We observe each other and are observed by more-than-human beings, be it in the form of surveillance or as data recording. The slow motion and “stopping the image” destroy the fourth wall and shatter audience’s expectations. Being familiar with the cyclic pattern of the video, the absence of the image and sound creates apprehension. Human attention tends to be directed to text but in digital poetry one tends to perceive words as images before their potential arrangements are contemplated semiotically. Memmott argues that “[d]igital poetry presents an expanded field of textuality that moves writing beyond the word to include visual and sound media, animations, and the integrations, disintegrations, and interactions among these signs and sign regimes” (294). In other words, the change from a printed Waveform to its film version is not simply an issue of the medium (the soundtrack and the original airborne drone footage were “added”) but the many other variables enumerated above, such as multimodality and immersive engagement, have an impact on viewers’ potential receptiveness.

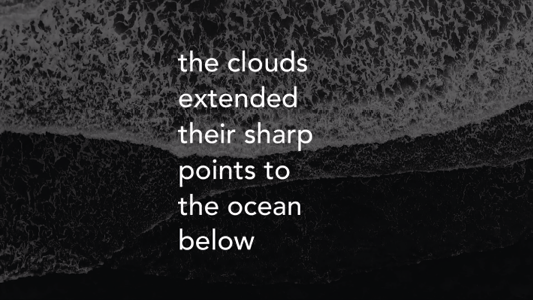

All of the drone-recorded scenes portray one oceanic process: the breaking of the waves. This is the process in which the waves’ energy seemingly appears to be dispersed in the spray as it is coming to the shore. In reality, the energy’s total does not decrease or increase, only the wave’s length or height might be altered (Raichlen 61), subsequently the new material (sand) is exchanged. What is worth noting is that there is no one single way of waves’ entering the land: they can outpour, spill, subside and dive (62). Unlike the drone’s vision that records indiscriminately, people are not always able to capture such more-than-human modalities, mostly because they are not paying enough attention. In the opening scene of the film, the large title Waveform appears hardly visible on white (spray) images set in nearly equal proportions with regards to the dark land. Then, the situation is inverted. Waveform occurs on the contrastive black background in the proportions of 2/3 to the lightness. The duality of the title renders the central dogma of the contrast rule in which the proportions as well as the degree of light and darkness vary all the time, in each and every second of the video. The drone-generated poem appears to be superimposed on the images of waves:[5]

The 4-lined text is far from being figurative. The main poetic device here results from the oxymoronic expression about the sharpness of the air. The serration connotes violence (see the military context) and jagged edges of a demarcating line that drone is supposed to draw. Additionally, sharp points bring to mind the raggedness of the machine vision. Readers are informed that the observation point is above the water surface, which is supposed to create an artistic effect of the drone’s own aerial account. Many statements here seem to be paradoxical, as if undermining the human-centered viewpoint. The clouds do not have pointed edges and they are limitless, therefore they cannot lengthen (see “extended”). The transparent constituent parts (“points”) of air are indeed made of atom particles and so is the observing drone. The ocean situated beneath (“below”) the clouds produces mellow soundscapes, which dilutes the raggedness of the visual material.

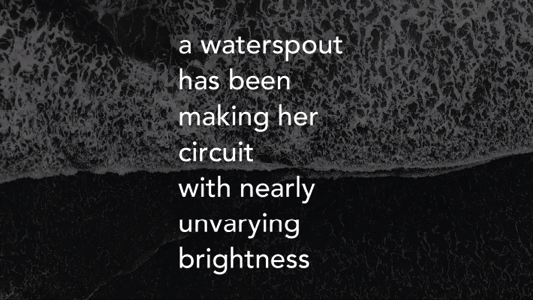

The subsequent task of drawing the boundary is performed far more accurately by drones, which shows that the machine is indeed learning fast. The second textscape follows:

The most imaginatively unexpected part of this poem comes from the usage of the pronoun “her” in relation to a waterspout. The waterspout’s meaning alters depending upon the gender pronoun: cloud vortexes are feminine and the gutter-pipe is masculine. The large lexical disparity between two senses of this term creates an additional humorous effect. The noun denotes a type of cloud (usually a cumulonimbus or a cumulus congestus) that take shape of a whirlwind, which actually can outspread, as the previous poem suggested. The difference to be recognized requires a dictionary entry, which establishes a sort of lexical closeness in human-machine learning. Going round in circles, the waterspout is endowed with agency. Waves are generated by the wind, therefore, any change in the atmosphere, affects the surface of the water. If the previous poem focused on lines and forms, this one concentrates on light and darkness. Once more, a metaphoric element links wave movement with illumination. The modifier “unvarying” with regards to brightness is an overstatement as light nearly always changes and so does human perception of it. One may wonder: can drones perceive light as constant?

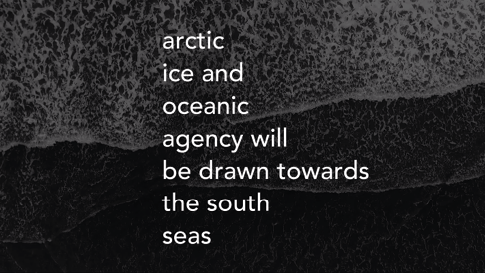

The visual image number three may seem misleading at it renders two potential dividing lines: the foamy, disintegrating into the sea, and the latter, spray-less, which encroaches the land. Therefore, the program (drone?) has to decide which one is more “real.” The verdict is made in favor of the line that goes further into the coast, even though it is much more blurred and less sharp in the context of the light/darkness contrast. From a human perspective, such a choice would be disputable, if not erroneous. The clash of perspectives makes one realize the span of more-than-human outlooks. The question remains open which option is to be considered as mistaken and why there cannot be two “right” answers. After the soundscape sequence, the following poem enters:

The passage above meditates upon the forces that regulate the oceanic cycles. The related phenomenon appears to be alarming. The north arctic areas and their climate should be located as far as possible from the southern regions. The poem in its future form sounds like a grim prophecy of impending doom. Its source is not derived from immediate observations. The Cornish sea temperature ranges from 7 degrees to 18 in summer, hence it is very far from the arctic cold. Moreover, the drone could not have processed the visuals of ice in their observing spot; therefore, this concept must have been obtained indirectly from the literary feed. “Ice and oceanic agency” is an unexpected expression but very accurate, as it renders its formative capacities. Its plural dimension conveys the concept of acting together. Their potency is, however, qualified by a solid force of “being drawn” towards the south. The implied message could relate to climate change, melting icebergs and the rising temperature of water supplies.[6] Once the ocean’s agency is declared, it vanishes immediately when the words fade away.

The visuals depicted above render a similar unresolved dilemma: there are two places where the land meets water, and software, as before, draws the line the furthest into the beach. It is an almost accurate line but for the lack of curves. When faced with the choice, the program almost by default chooses the line that seems to be going deepest into the beach. The poem underneath seems to address the “shadowy” question of a choice:

The cited passage is written in the form of a quest journey. The crucial question to consider is the subject of enunciation “it” (the wind? the wave? the drone?). Its non-human form suggests the drone’s aerial explorations. Strickland and Montfort call human-machine creative interaction provocatively a “collaboration with ‘it’” (6), emphasizing how underappreciated in artistic exchanges the role of more-than-human co-authors may be.[7] The expression “meeting with the shadows” sounds ominous and it renders the part of the journey when courage and determination are put to the test. The antiquated “thenceforth” intensifies the archaic tone of the poem. For drones, shadows are the most challenging points to render them visually since the contrast between the light and darkness is faint and shapes lose their sharp contours. Furthermore, shade is the point when light fuses with darkness, creating chiaroscuro, the points where “either/or” options are not applicable, therefore becoming ambiguous for drones. Overall, the poem reflects upon perpetuation, but this time the movement is directed northwards.

The perfectly edged line (with some circular elements) identifies digital poetic collaborative practice. The words are superseded upon the image located in light, overpowering darkness.

The poem meditates upon the storm or hurricane that sunk human dwellings. This time, however, one can discern the unexpected affect in the selection of lexicon: “irresistible” and “fury,” which conveys rather a human (?) emotive angle. The narrative of people’s settlement, gradually going under the water, is connoted with expressions of unstoppable rage. For the first time, the melodic elements appear: three subsequently alliterated words: “second swept / still” echo with “submerging.” Apart from consonant “s” also “r” is repeated in the opening sequence, echoing the droning sound. The “second swept” could refer to the double lines and the ocean encroaching deeper and deeper into the land, taking back its territory.

The excerpt below brings an almost bucolic tone:

The passage above seems to resemble the Middle English frivolous and joyful adorations of the end of winter. The fragment introduces a concept of seasons. It puts the visual date on a temporal scale of the beginning of the new cycle. However this temporality somehow clashes with the chronological video output. One might get the impression that the drone’s watch (surveillance) never ends. Once again we have two alliterated initial words: “spring” and “spent,” the passive construction seems to refer to the older (formal) versions of English rather than contemporary ones. At that stage, the atmospheric conditions (“cloudy,” “foggy”) make the observation difficult, if not impossible. “Breaking the (waves?) lines and circles” appears to refer to the flaws and irregularities in drawing the line between the sea and the land. The textspaces do not terminate or begin; they are fragments, loosely related to each other, and readers can replay them as many times as they want:

The poem explores the destructive activities of humans with regards to the ocean. “Men” (humans? or male mariners?) who succeeded in their “unearthing” toil appear to be rendered with an ironic twist. “Throw up” evokes bringing to light, along with devastating by turning things upside down. The sea’s vulnerable liquidity clashes with firm foundations. The process related in the poem might also be a comment on how images are structured on video in their fluid form.

The poem seems to be ungrammatical, its twisting sequence suggesting breaks in the half of the narrative. This time the subject “we” remains unclear: it is not certain whether it refers to people, drones, or their more-than-human collaboration. The passage ironically opens with “naturally” although there is nothing “natural” either in the form, text or images that readers follow. The collocations of “naturally” with “every picture” intensifies a paradoxical message. “We take / leave”—the equity sign is created between moving and staying, comparable to the flows and ebbs. “Hitherto” sounds archaic, which destabilizes the temporal framework. Every image that is recorded corresponds to the one that is still ahead, to the “unknown sea.”

The final poem constitutes an homage to the sea: surprisingly, the drone this time produces a relaxed and even exhilarated output. It generates a clear note of emphasis, even surplus, in this passage. Yet “fantastic form” is not an expression commonly heard with regard to the ocean. There is a note of falseness in it, which would stand out in the Turing test. It brings to mind the altering dynamics of the machine-human vulnerabilities. The ocean remains the nearly Platonic form, ideal and permanent essence, yet whose substance is always changing. Because one cannot regulate in advance a generative poetic practice, it also means accepting the random and changeable outcome of multimodal interactions.

On the one hand, the vulnerabilities of the drone’s vision enable humans to identify to some extent with its imperfections but its scope and viewpoint always remains more-than-human. On the other hand, bearing the military dimension in mind, they also demarcate a fragile and imprecise line between observation and killing. What is perceived as belonging to the so-called natural world and what to the so-called constructed world becomes blurred in Waveform. “Natural” waves become “artificially” pixelated and their “original” sound is technologically simulated as well. Yet it is no sooner than with the arrival of the graphic drawn boundaries of the machine vision that readers become confronted with arbitrariness of their seeing concepts. Last but not least, imposing the words upon the waves/image digitally processed and presented from more than human perspective distorts the arbitrary line between the mediated vision and the so-called reality.

In conclusion, as shown above, drone-generated poetry encompasses diverse variables within a human-machine and waves cooperative spectrum. Instead of assuming an environmental or sensory-engineering angle, the article has attempted to approach drone-generated poems as textscapes that cannot be analyzed outside the digital realm and without taking multimediality or code into account. Not reducing digital literature to analogue writing, drone-generated poems create an aesthetic and literary output of the human-machine collaboration, revealing the points of tension and the vulnerabilities of such exchanges.

katarzyna.ostalska@uni.lodz.pl

Bell, Alice, et al. “A [S]creed for Digital Fiction.” Electronic Book Review, 3 July 2010, https://electronicbookreview.com/essay/a-screed-for-digital-fiction/, accessed 18 Dec. 2022.

Bell, Alice, et al. “From Theorizing to Analyzing Digital Fiction.” Analyzing Digital Fiction, edited by Alice Bell et al., Routledge, 2014, pp. 2–17. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203078112

“Bayraktar.” Translated by Taras Borovok. Lyrics Translate, https://lyricstranslate.com/en/bayraktar-bayraktar.html, accessed 10 Jan. 2023.

Carter, Richard A. “Airborne Inscription: Writing with Drones.” BCS Learning and Development Ltd. Proceedings of Proceedings of EVA London 2018, UK, pp. 367–73. Science Open, July 2018, https://www.scienceopen.com/hosted-document?doi=10.14236/ewic/EVA2018.69, accessed 5 Jan. 2023.

Carter, Richard A. “Drone Poetry—On Deploying Sensory Technologies as Tools for Writing.” The Writing Platform, 5 Sept. 2017, https://thewritingplatform.com/2017/09/drone-poetry-deploying-sensory-technologies-tools-writing/, accessed 5 Jan. 2023.

Carter, Richard, A. Waveform. Richard A. Carter, https://richardacarter.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/Waveform-Web.pdf#view=FitV&toolbar=0&navpanes=0&scrollbar=0, accessed 18 Feb. 2023.

Carter, Richard A. “Waveform.” The International Journal of Creative Media Research (Special Issue 5: Digital Ecologies: Fiction Machines), Oct. 2020, https://www.creativemediaresearch.org/post/waveform/, accessed 5 Jan. 2023. https://doi.org/10.33008/IJCMR.202017

Carter, Richard A. “Waves to Waveforms—Performing the Threshold of Sensing and Sense Making in the Anthropocene.” Arts (Special Issue: The Machine as Artist [for the 21st Century]), vol. 7, no. 4, 2018. MDPI, 30 Oct. 2018, https://www.mdpi.com/2076-0752/7/4/70, accessed 16 Jan. 2023. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts7040070

Cayley, John. “The Advent of Aurature and the End of (Electronic) Literature.” The Bloomsbury Handbook of Electronic Literature, edited by Joseph Tabbi, Bloomsbury, 2017. E-book.

Cayley, John. “Time Code Language: New Media Poetics and Programmed Signification.” New Media Poetics: Contexts, Technotexts and Theories, edited by Adalaide Morris and Thomas Swiss, MIT P, 2006, pp. 307–33. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/5002.003.0021

Chamayou, Grégoire. A Theory of the Drone. Translated by Janet Lloyd, The New, 2015.

Funkhouser, C. T. New Directions in Digital Poetry. Continuum, 2012.

Golding, Alan. “Language Writing, Digital Poetics and Transitional Materialities.” New Media Poetics: Contexts, Technotexts and Theories, edited by Adalaide Morris and Thomas Swiss, MIT P, 2006, pp. 249–83. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/5002.003.0017

Hayles, N. Katherine. Electronic Literature: New Horizons for the Literary. U of Notre Dame P, 2008.

Hayles, N. Katherine. “The Time of Digital Poetry: From Object to Event.” New Media Poetics: Contexts, Technotexts and Theories, edited by Adalaide Morris and Thomas Swiss, MIT P, 2006, pp. 181–209. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/5002.003.0013

Joyce, Michael. Of Two Minds: Hypertext Pedagogy and Poetics. U of Michigan P, 1995. https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.10599

Memmott, Talan. “Beyond Taxonomy: Digital Poetics and the Problem of Reading.” New Media Poetics: Contexts, Technotexts and Theories, edited by Adalaide Morris and Thomas Swiss, MIT P, 2006, pp. 293–306. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/5002.003.0020

Morris, Adalaide. “New Media Poetics: As We May Think/How to Write.” New Media Poetics: Contexts, Technotexts and Theories, edited by Adalaide Morris and Thomas Swiss, MIT P, 2006, pp. 1–46. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/5002.001.0001

Naji, Jeneen. Digital Poetry. Palgrave Macmillan, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-65962-2

Naji, Jeneen. “The Art of Machine Use Subversion in Digital Poetry.” Hyperrhiz: New Media Cultures, vol. 20, 2019. https://doi.org/10.20415/ hyp/020.net02

Raichlen, Fredric. Waves. MIT P, 2013.

Rettberg, Scott. Electronic Literature. Polity, 2019. E-book.

Strickland, Stephanie. “Born Digital.” Poetry Foundation, 13 Feb. 2009, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/69224/born-digital, accessed 5 Jan. 2023.

Strickland, Stephanie, and Nick Montfort. “Collaboration in E-lit.” American Book Review, vol. 32, no. 6, 2011, pp. 6–7. https://doi.org/10.1353/abr.2011.0134

Swanstrom, Elizabeth. Animal, Vegetable, DIGITAL: Experiments in New Media Aesthetics and Environmental Poetics. U of Alabama P, 2016.

Woolf, Virginia. The Waves. 1931. Collector’s Library, 2005.

Wright, David Thomas Henry. “Collaboration and Authority in Electronic Literature.” TEXT: Journal of Writing and Writing Courses (Special Issue 59: Creating Communities: Collaboration in Creative Writing and Research), vol. 24, 2020, pp. 1–12. https://doi.org/10.52086/001c.23486

Zylinska, Joanna. AI Art: Machine Visions and Warped Dreams. Open Humanities, 2020.