https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3357-8303

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3357-8303

University of Bialystok https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3357-8303

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3357-8303

Informed by the current call for a reassessment of the concepts of radicalism and extremity in the fields of literature and visual arts, my study aims to investigate the radicalities entailed by the tactics of turning inside out the materialities of poems and artworks as exemplified, respectively, by Emmett Williams’s concrete poetry and Roman Stańczak’s sculptural works conceptualized as inverted everyday objects. Taking a cue chiefly from Catherine Malabou’s explorations of plasticity, I propose to argue that by destabilizing the interior/exterior dichotomy of the forms belonging to their respective fields, both Williams and Stańczak challenge the commonplaceness, transparency and rigidity of text, sign, and the quotidian object, thus, on the one hand, gesturing towards what the philosopher terms as “the twilight of writing” and, on the other, articulating a need for a more processual and contingent, or plastic as Malabou would have it, way of thinking about literature, art, and life. As I hope to demonstrate, by employing certain strategies to exteriorize the “insides” of the poem (the syntax, the page grid, spacing, or the shape of the grapheme), Williams foregrounds the discursive interplay of the graphic and the plastic, whereas Stańczak’s altered objects foray into inquiries on (the lack of) transcendence. The final part of my analysis seeks to envision political dimensions of both concrete poetry and Stańczak’s visual works as filtered through the lens of plasticity. The implications brought about by plastic reading, as I claim, link with new models of meaning-making and forms of resistance to ideologies of power.

Keywords: concrete poetry, sculpture, plasticity and inversion, Emmett Williams, Roman Stańczak, Catherine Malabou

In her multifaceted considerations of the concept of the dusk of the written form in her seminal Plasticity at the Dusk of Writing, Catherine Malabou develops a link between the term and the notion of insomnia, “the melancholic state into which the psyche of someone who cannot mourn the lost object descends,” which further translates as “the impossible end of writing, with plasticity infinitely opening the wound of an interminable mourning” (15).[1] In effect, as the philosopher imagines it, “even when it is dead and replaced by plastic sublation, writing would nevertheless return, other and stronger . . . , speculatively promoted” (16). Thus, however firmly pronounced, the twilight of writing, understood by Malabou in a Derridean fashion not merely as a “transcription of speech or simple ‘written form’” (12), but in an enlarged sense as “arche-writing,” “the general movement of the trace” (12), “all that gives rise to inscription in general, whether it is literal or not” (Derrida qtd. in Malabou, Plasticity 58), appears to fail to mark a definite departure from the linguistic-graphic paradigm of organizing human thought. Noticing the dusk to have “too many dusks” in itself (Malabou, Plasticity 16), Malabou detects the space between writing and plasticity as “a darkened frontier” and “a passage to the other on the same ground” (16); and if the philosopher perceives this indistinct area to be guided by a reprieve, mourning, melancholy, and separation, what could be said about the perimeters of a writing that is metamorphic and cannot depart? I would like to argue that the specificities of writing in twilight are well communicated by concrete poetry, whose radical aesthetics invite one to reappraise their protrusion from the sanctioned idioms of artistic expression into something larger than writing. Aiming to delineate the plastic implications of concretism, I engage in a discussion of Emmett Williams’s concrete poems which attempt to materialize the compositional “insides” of the poetic form and which find a silent partner in the inverted textures of Roman Stańczak’s sculptures.

Emerging at the beginning of 21st century together with other critical ventures classified under the aegis of “new materialism,” Malabou’s reflection on the need to recalibrate our thinking about the modalities of writing partakes in voicing larger concerns about focalizing critical attention on the notion of representation and rehabilitating language as an epistemic tool, all characteristic for social constructionism and the so-called linguistic turn. The preoccupations of academe at the turn of the centuries have been succinctly summarized by Karen Barad:

Language has been granted too much power. The linguistic turn, the semiotic turn, the interpretative turn, the cultural turn: it seems that at every turn lately every “thing”—even materiality—is turned into a matter of language or some other form of cultural representation. . . . What compels the belief that we have a direct access to cultural representation and their content that we lack toward the things represented? How did language come to be more trustworthy than matter? (801)

Believing, on the one hand, that “language and other forms of representation [are given] more power in determining our ontologies than they deserve” (Barad 802) and, on the other, willing to generally decolonize critical thought from its foundations that always subsume discussions within the logic of binary oppositions (nature/culture, subject/object, language/matter, among others), the advocates of new materialist theories have sought to build their endeavors around restoring the agency of matter.

Along with various other domains, this paradigmatic shift has entailed a number of implications for the fields of literature, literary studies and literary theory. Surveying a wide range of literary materialisms, Liedeke Plate observes that the material turn in literary criticism and creative endeavors have existed in fertile reciprocity, with the former helping to generate “new objects of literary study,” yet simultaneously constituting “[a] response to new literary and artistic practices,” which have otherwise posed an insurmountable problem for dominant critical paradigms (11). For Plate, an object of study “attesting to the importance of the materiality of literature” (10) and requiring a thoroughly reconsidered methodology of criticism is perfectly typified by Emily Dickinson’s envelope poems, a set of works “written on bits of salvaged envelopes, torn or carefully pried apart at the seams and flattened out” (9) which were not discovered until the mid-1990s. In the scholar’s own words,

Dickinson’s envelope poem demands that the scholar accounts for the materiality of the paper, its shape, folds, and traces of former uses and that she accounts for the ways in which she holds the paper in her hand, feels its texture, turns the multidimensional physical object around. In consequence, the new object of study also requires another language, a vocabulary to speak of materials and the materiality of literature; a language that is largely unknown to the student of literature, whose glossary of literary terms includes burlesque but not buckram, interpretation but not interleaved, rhyme but not rubbed. (11–12)

In the second half of the 20th century, parallel challenges to readerly habits and critical tools were openly reiterated by concrete, visual and conceptual poetry, whose modalities anticipated a host of new materialisms’ premises by predicating on the arbitrariness of binaries such as the verbal/the visual and language/matter, to say nothing of their mistrust of representation. Interestingly enough and concurrently to the emergence of new materialisms, in the first decades of the 21st century these poetics have enjoyed a steady revival of interest with poets, publishers and curators. Some scholars have attributed this resurgence to the current perimeters of culture that bespeak of living through the “late age of print,” in which all “the literary [becomes revaluated] as an ‘analogue’ verbal-visual art” (Plate 11). Others, which is equally significant for my later discussion of plasticity in Williams’s and Stańczak’s works, have sought to link its momentum with the circumstances of the crisis of culture. Willard Bohn and Grant Caldwell concur in claiming that the renewed interest in crafting visual poetry, which Caldwell wishes to subsume into the category of concrete poetry (and which is certainly debatable), converges with “a crisis of the sign, which reflects a crisis of culture” (Caldwell).[2] In François Rigolot’s view, this translates as a phase when “the formulators of culture . . . question their expressive medium” (qtd. in Caldwell), which is undoubtedly facilitated by the emergence of new technologies and forms of communication. The ebbs and flows of interest in visually-oriented poetics, Bohn continues, are not confined to the last century, but are a phenomenon that has continued at least since the Alexandrian period, always foreshadowing paradigmatic shifts in culture (qtd. in Caldwell). Thus, foundational for the practice of visual poetry, the idea of the crisis of the sign, defined in its basic sense as “an object, quality, or event whose presence or occurrence indicates the probable presence or occurrence of something else” (“Sign”) comports with the premises of new materialisms which disavow and plunge the ontological powers of representation into discredit. The literary, which fades into the “analogue” verbal-visual in the late age of print, appears to intersect with the condition of the “linguistic-graphic scheme” of human thought heralded by Malabou as “diminishing and . . . enter[ing] a twilight” (Plasticity 59) to be eventually superseded by the plastic modality. Plasticity is further explored and expanded by the philosopher in a number of works, including the 2009 The Ontology of the Accident: An Essay on Destructive Plasticity, which, among other contexts, grounds the concept within the perimeters of Freudian psychoanalysis, neuroscience and trauma studies to recognize the ontic character of the accident and destruction and reflect on its implications for subjectivity. The book brings further complexity to the notion, discussing “the phenomenon of pathological plasticity, a plasticity that does not repair” (Malabou, The Ontology 6) as set against transformation and elasticity, both of which do not close on facilitating one’s redemptive return to initial form. Such distinctions, as I hope to demonstrate while reflecting on Stańczak’s sculptures, find reverberations in the realm of aesthetics.

Returning once more to Malabou’s intuitions on identifying the dark territory between the paradigms of writing and plasticity, I would posit that the aesthetics of concrete poetry have always gestured towards the limits and extremities of verbivocovisual expression (to use the term coined by the Brazilian Noigandres group), thereby enacting writing at dusk. Self-referential, permutational and materiality-oriented, concrete poetry can be perceived as a solipsistic exorcism and an act of grieving over the defectiveness of logos, to whose linguistic-graphic manifestations it nonetheless melancholically holds in the act of expression. Concurrently, forming the Malabouian “passage to the other” (Plasticity 16), selected works of concrete poets such as Emmett Williams, whose material concerns have been echoed in recent decades by the sculptural output of Roman Stańczak, foreshadow a number of processes comprising the new plastic paradigm. As I hope to stress, among other operations they foreground the interplay of the graphic and the plastic as well as engage in the Malabouian-Heideggerian debate on the closure of transcendence. In a more general perspective, involved in autotelic and anti-mimetic artistic procedures, both Williams and Stańczak lend themselves to a plastic reading, which typically “seeks to reveal the form left in the text through the withdrawing of presence, that is, through its own deconstruction. It is a question of showing how a text lives its deconstruction” (Malabou, Plasticity 52).

However, a significant problem evoked by Malabou’s perception of plasticity comes with the question of how one should situate their work in relation to the French philosopher’s wish to confine plastic readings to philosophical discourse. As Malabou posits, “it is necessary . . . to delocalize the concept of plasticity outside the field of aesthetics. More specifically, it is a matter of breaking with the idea that the primary area of meaning and experience for this concept is the aesthetic or artistic field” (56). Reflecting further on the reading of form as a Gestalt and calling it “the most suspect of all metaphysical concepts,” Malabou understands the ethical necessity, on the one hand, “to give up on the scene understood as presentation, representation, or figuration” and, on the other, “to privilege the formless, the unpresentable, ‘the defiguration,’ the scenic removal” (54). To some extent, literary scholarship has been able to address and grapple with these concerns. Arguing that the notion of plasticity “finds echoes in literary critical conversations about form” and “already belongs to the aesthetic analysis of poetry” insofar as it predicates on “the reciprocal giving and receiving of form” (197), Greg Ellermann points to the speculative powers of Romantic-period thought and poetry as represented by Keats, Coleridge and their contemporaries. No less significantly, Ellermann identifies the source of Malabou’s plasticity in the very field of aesthetics. In the same vein, working on the interstices of poetry and plasticity and discussing the plastic potential of The Waste Land (first and foremost focalized around Tiresias’ metamorphic potencies), Matthew Scully propounds that “Malabou’s concept might be productively transposed from ontological form to poetic form and thereby mobilized for a literary reading” (167). Finally, it is also in Plasticity at the Dusk of Writing that we find Malabou’s own assessment of deaesthetization of form as a praxis which, in a paradoxical manner, generates “artistic significance” (56). At one point, in order to substantiate her thoughts on the dialectics of form and the trace, the philosopher refers to Giuseppe Penone, a sculptor whose operations she wishes to see as enactments of the formation of the trace and the emergence of form (Plasticity 49–50, 93n115). The respective praxes of Williams and Stańczak intersecting at foregrounding the metamorphosability of matter, with the inside-out inversion being exemplary means of achieving this, resonate with scholarly reconsiderations of utilizing the concept of plasticity in literary criticism thus furthering the search for aesthetic implications of Malabou’s argument.

Before venturing into charting the plastic modalities of Williams and Stańczak, it is also interesting to notice that a type of configuration of form made evident by a plastic reading—in Malabou’s words, “the fruit of the self-regulation of the relation between tradition and its superseding and which at the same time exceeds the strict binary terms of this relation” (Plasticity 52)—aligns in a peculiar way with the trajectory of reception of concretism in literature. The extreme character of concrete poetry relegated the movement to the margins of what has been aptly defined by Charles Bernstein as the “official verse culture” (246). What the culture endorses, Bernstein notes, is “a restricted vocabulary, neutral and univocal tone in the guise of voice or persona, grammar-book syntax, received conceits, static and unitary form” (245). Not being any of this, concrete poetry has come in for a wide scope of denigration. This ranges from “a common criticism . . . that it represents nothing more than a kind of automatism where isolated words are arbitrarily thrown together” (Tolman 156), through conceiving of it as something “usually lucid and simple . . . [with its] appeal often more sensuous than intellectual, more immediate than dependent on long study” (Scobie qtd. in Beaulieu 24), to peak with strong declarations as represented by Louise Hanson, who claims that “no concrete poetry is literature” (79). Together with the challenges posed by defining concrete aesthetics, all this made concrete poetry, Kenneth Goldsmith notes, “a little, somewhat forgotten movement in the middle of the last century” (qtd. in Beaulieu 23).[3] Unsuccessful as they turned out to be in opening a larger crack in the sanctioned and sanctified dominant literary discourses, the practices of concrete poets nevertheless appear to have marked an interesting and perhaps an ongoing moment of Malabouian self-regulation between traditional notions of poetic form and something which is yet to come. Given this context, the invitation by the Noigandres group to envisage concrete poetry as “tension of things-words in space-time” (Campos 72) could be seen as related not only to the confines of the page but also to the paradigmatic frictions effectuating the metamorphoses of the historicity of literature. There is, therefore, yet another reason why the failed revolution of concrete poetry might be worth returning to and reappraising for its radical inquiry into the transformative and plastic capacities of form.[4]

The plastic implications of Emmett Williams’s poetry, as manifested via the tactics of turning inside out the materialities of the poem, would not be by any means identified as the chief characteristics of the artist’s prolific output. Alongside his interdisciplinary and collaborative involvement in the visual arts, performance, editing and coordination of Fluxus events, all of which raised arguably the biggest critical interest in his work, Williams is typically remembered and credited for editing the first American anthology of international concrete poetry published in 1967 by New York-based Something Else Press. His own work in concrete poetry has been recognized as significant for the early development of concrete aesthetics while simultaneously garnering startlingly little criticism. As Nancy Perloff observes, “[d]espite Williams’ role as an enthusiastic promoter of concrete poetry . . . and as a leading figure within Fluxus, there are currently few scholarly articles and no monographs . . . analyzing his long artistic career and collaborations” (“Getty Research”). It may be that the failure to address Williams is a symptom of a bigger problem besetting criticism—namely, its inability to seriously approach “any radical deviation from a printing norm” and its “difficulty of talking about visual prosody; we lack a sophisticated critical tradition and ready vocabulary” (Dworkin 32).

Since it approximates Williams’s poetic tactics, Malabouian perception of discursive alterities may offer one specific way of framing an approach to concrete aesthetics, partially making up for the deficiencies of criticism. To begin with and to reiterate an earlier point, the philosopher’s discussion of plasticity is grounded in confronting the graphic model of writing, being analogous to the Derridean work of the trace and the infinite entanglement of the signifier in the movement of differance, with plasticity as a reformulated paradigm for human thought going beyond deconstruction, engaging neuroscientific findings and manifesting the “aptitude to receive form, . . . the ability to give form, . . . [as well as] the power to annihilate form” (Malabou, Plasticity 87n13). However, oppositional as they are, Malabou continues, the graphic and the plastic convene and may be perceived as indispensable to one another. By referring to Lyotard’s Discourse and its discussion of this specific space of discourse which “is not itself a linguistic space in which the work of meaning takes place, but a kind of worldly, plastic, atmospheric space in which one must move about, circle around things, to vary their silhouette and be able to offer such and such meaning that was hitherto hidden” (qtd. in Malabou, Plasticity 55–56), Malabou wishes to see “plasticity . . . [as] the condition of existence of meaning [in the graphic] in as much as it confers its visibility upon it” (56). Significantly, as Malabou concludes, the implications of language exteriorizing itself into the graphic via plastic space of the discourse extend to the field of art, which facilitates the movement “from the interior of discourse . . . into the figure” (Lyotard qtd. in Malabou, Plasticity 56), thereby generating an incessant alterity of forms, a flow of “energy, infinitely composed in painting, fiction, music and poetry, [being] precisely the form of writing” (Malabou, Plasticity 56).

A significant part of Emmett Williams’s poetic and artistic output appears to enact the moment of moving from the plastic to the graphic as delineated by Malabou and Lyotard. Turning to works comprising Selected Shorter Poems, one is bound to notice that most of them share combinatorial, substitutional and permutational operations as their generative engine. The elements being subjected to permutations range from the letters of a single word (such as “words”) (Williams, Selected Shorter Poems 53), graphemes (56), phonemes and positions of syntactic elements (71) to mirrored clauses (as in “i think therefore i am”) (27). What is additionally discernible in the poet’s works is his fixation on the alphabet; in several poems Williams utilizes twenty six letters of the English alphabet to craft alternative alphabetical orders and to alternate the visual modes of their representation (see Fig. 1 and Fig. 2, respectively, “bacedifogu” and “ab”) (58–59). Pushed to the extreme, the performed actions produce the unreadable; one operation of overwriting letters results in an illegible ideographic rendition of the alphabet executed as twenty six thick lines/strokes of black ink, in which both the alphabetical order of letters, their actual selection and even the very relation of the lines to the alphabet are nothing but speculative (“26 alphabets” in Fig. 3) (60). The other pole of radical operations on the alphabet comes with Williams’s far-from-minimalist “The Alphabet Symphony,” described by the poet himself as

a public “universal poem” . . . [in which] twenty-six objects and/or activities are substituted for the letters of the alphabet [and performed], so that, for example (and the examples are not meant to prove anything), during the London performance the word “love” could have been spelled the smoking of a cigar plus blowing a silent dog whistle plus eating the chocolate off the floor like a puppy plus tooting a little ditty on the flute. . . . (163–67)

|  |  |

| Fig. 1 | Fig. 2 | Fig. 3 |

Copyright 1975 The Emmett Williams Estate.

Thus, by attacking the most basic code of the logos and corrupting it by implanting in it other codes such as algorithms and permutations, and producing alternative alphabetical orders and models of their graphic representations thereby, Williams foregrounds the plastic contingencies of discourse. In a way, the alphabetic poems seize the moments of externalizing various potentialities of the plastic, which confers forms, such as linguistic codes, that amount to the plastic form of writing. Moreover, the Malabouian postulate of deaestheticizing form, which in a peculiar manner helps it to gain a deeper artistic significance (Plasticity 56), finds its successful realization in Williams’s poems. In keeping with Malabou’s argument, the emergence and accentuation of the graphic/the figural in the concrete poem is “not a means of [exhibiting] plastic resistance to discourse but [a way of uttering] the depth of the field of discourse itself” (56). Put in other words, reduced to the most basic units of the linguistic code and inflected with algorithms, Williams’s alphabetic procedures make visible the act of conferring visibility onto meaningful units. Accordingly, the illegible poetic form from Fig. 3 seems to reenact in a twofold way the opposite and the extreme of the aforementioned act, which is, respectively, the discursive invisibility of the action and the event that Carloyn Shread has aptly termed as “the infinite slippage of the signifier in the graphic model” (130).

Throughout Williams’s career the praxis of deaestheticizing the aesthetic (and, as Malabou helps us to see, bringing to light the nucleus of the form of writing) was orchestrated in many other ways. In Schemes & Variations, showcasing a selection of his works from the late 1950s to the early 1980s, the artist stresses that

[t]he most important part of the process of making art is the desire to understand the process of making art. I like to see, and I like to show, the bare bones of the process. In most of my serial works, the variations are only steps towards the last picture in the series—but the last picture, without the variations that lead up to it, is not enough. The series must be looked at as a whole. Following the process . . . is really what the work is all about. (11)

Analogically, alongside visualizing the undoing of the alphabet, much of Williams’s poetry attempts to exteriorize other structural and material components of the poetic form. Looking once more at the discussed alphabetical poems, the works presented in Fig. 2 and Fig. 3 disestablish the apodeictic axes of reading—predilection for horizontal and linear sequence of phrases building up the verse—by inviting the reader to a more vertically-oriented, algorithm-guided, paragrammatic reading. In terms of text layout, the poem in Fig. 3 appears to additionally destabilize (and thus expose) the grid of the page by overlaying multiple strings of letters, and by doing so, bringing out (the lack of) line spacing. The black lines generated therefrom may be also seen to be activating, intensifying and, to a certain extent, mocking the property of word-spacing (despite reinforcing spacing, the text is illegible).

Another noteworthy constructive element which is inverted inside-out by Williams is syntax. In “do you remember” through an act of recollection the speaker develops a narrative by alternating between their own and their addressee’s past activities and states. The verse is generated by applying what might be called a gradual and cyclical permutation; the variables of a consecutive position in a clause grow by one, with an invariable conjunction and beginning every line (the mathematical pattern would thus be: and plus pronoun+1 plus verb+2 plus adjective+3 plus adjective describing color+4 plus noun+5). An example of one full cycle is as follows:

and i loved mellow blue nights

and you hated livid red valleys

and i kissed soft green potatoes

and you loved hard yellow seagulls

and i hated mellow pink dewdrops

and you kissed livid blue oysters (Selected Short Poems 250)

Copyright 1975 The Emmett Williams Estate

The tactic seems to but graphically highlight, and again likely mock, the rigidity of sentence structures (such as the fixed grammatical order of multiple adjectives). Anaphorically emphasized and being the only invariable element, the coordinating conjunction is literally at the forefront perhaps to signal the concretist preference for the equal valence of clauses over the necessity of subordinating one meaning to the other.

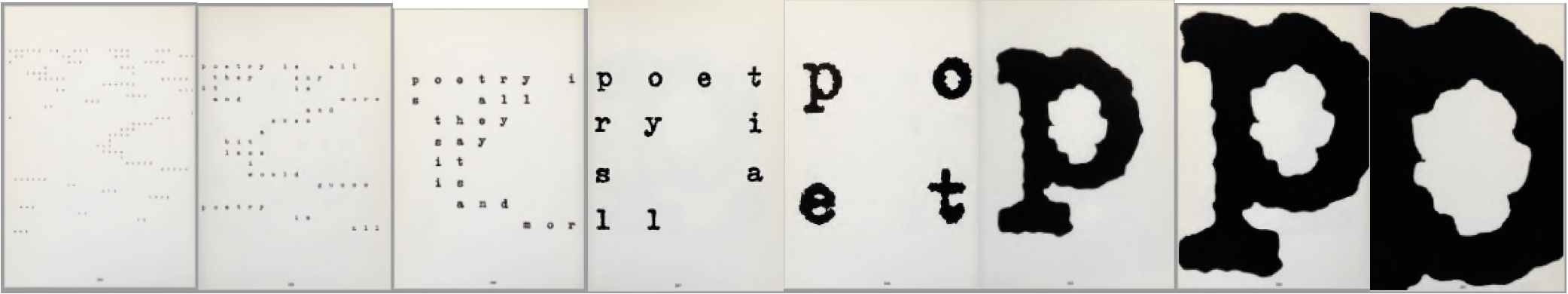

Finally, Williams’s 1970 “poetry is all” features a type of a zooming-in technique which, as if by reaching the other side of the grapheme, materializes the nuances of the shape of the sign and the medium of ink (Fig. 4). Composed as a sequence of eight developmental pieces, the poem loops the phrase “poetry is all they say it is and more and even a bit less i would guess” in each stage (Selected Short Poems 384) while successively increasing the font size. In the final installment, which illustrates the magnified bowl of the letter “p” and accentuates its counter of white space, the well-accustomed graphic form of the utilized character is somewhat lost, with a smooth curve giving way to a blotted and jagged stroke.

Fig. 4

Copyright 1975 The Emmett Williams Estate

The finale of the sequence invites one to read it as an act of undermining the firmness and rigidity of signs as well as a homage to the medium of ink, whose substance enables signs to take their material form. Somewhat reminiscent of a microscopic look-through the holes in Georgia O’Keeffe’s pelvis series or Roy Lichtenstein’s sculptural practice pivoting between two- and three-dimensionality, Williams’s serial poem, as it were, pierces through the two dimensions of the text and the page to further destabilize the dichotomy between the verbal and the visual.

The plastic radicalities of Emmett Williams’s experiments bringing out the sculptural qualities of poetic form seem to naturally segue into the work of a sculptor whose autotelic praxis, on the one hand, strongly echoes the investigations of concrete poetry and elicits further aspects of Malabouian plasticity, on the other. Roman Stańczak has been most recognized for his practice of violating the matter of quotidian objects by using chisel, wooden mallet or hammer to subsequently turn them inside-out. Misquic (1992) brings to light the discolored and rusted insides of a kettle, whose metal substance was melted until it became fluid. Cupboards (1996) showcases an inverted furniture set, reminiscent of a casual Polish transformation-era wall unit, which displays its fibroboard interiors and is covered in wood shavings produced by hammer work. Untilted (1996) features over a hundred scooped-out loaves of bread, with the removed bits and crumbs on the floor, which take all of the space of three wooden tables. Stańczak’s inversion of everyday items might be said to have found its twisted culmination in Flight (2019), an act of turning inside-out a private jet by means of splitting it and welding the inverted halves back; the commissioned sculpture drew much critical attention, representing the Polish pavilion at the 2019 Venice Biennale.

Stańczak’s works have been discussed in numerous contexts, offering both audiences and critics a cornucopia of interpretative possibilities. Compacting the potential of the artist’s oeuvre to Flight, one might traverse Dorota Michalska’s view and claim that Stańczak’s artistic output is “not easily framed by a singular discourse [for it] refers to a number of social, material, political and religious phenomena while not fitting neatly in any of them.” While absolutely significant and stimulating, these contexts, perhaps apart from the material concerns, eclipse the ontic register of Stańczak’s sculptures, which has not been given due critical attention and with which Malabou’s discussion of plasticity seems to strongly resonate. Of the few critics going beyond figurative readings of the inverted objects, Jan Verwoert senses the existential weight of Stańczak’s inquiry into the mutability of the altered items’ matter. In his eyes,

[i]t is as if a war was on. You feel it. Everything is under threat. Nothing is safe. . . . You are not imagining this. It’s real. . . . Things stay still. They remain real. That’s the scary bit. No ghosts. Just reality. . . .

This is the state of mind that work by Roman Stańczak can put you in. You sense that things are not entirely safe around his pieces. You feel that something is about to happen, or has happened, and the point is how to deal with it. Maybe Stańczak . . . is already trying to deal with it, and the outcome of his attempt is the very sculpture you are facing. (71)

The existential anxiety sensed and located by Verwoert in the viewer’s feeling of spiritual bereavement and being at the mercy of the brute and contingent reality of fluctuating matter reverberates through that part of Malabou’s framework which predicates on the plastic economy in Heidegger’s thought. Specifically, it is informed by the Heideggerian dissemination of being, which, as stressed by Malabou, posits a definite closure to transcendence as a potential outside-of-being:

Being-in-the-world, existing, amounts to experiencing an absence of exteriority, which is equally an absence of interiority. There is neither an inside nor an outside of the world. Dasein transcends itself, or in other words, ex-ists, only in the absence of a way out. To exist is thus neither to enter nor to leave but rather to cross thresholds of transformation. Dasein, says Heidegger, transcends itself only by becoming modified. (Plasticity 68)

Without transcendent alterity to rely on, Malabou continues, the only rule is the rule of the plastic; “[a]bsolute convertibility, the migratory and metamorphic resource of alterity, is the rule. Absolute exchangeability is the structure” (47). Verwoert, then, is right not only about the lack of a transcendental aid to rely on (“no ghosts”) when faced with Stańczak’s “bared things” (71–72), objects which have been literally deaestheticized and whose interior/exterior dichotomy has been distorted; he is also correct in noticing that they are being caught by the viewer in some act of conversion, defined neither by “already,” nor by “yet” (“something is about to happen, or has happened”) (71). Likewise, in keeping with plasticity’s power to both receive and give forms, which is in unison with Heidegger’s perception of experience (“To undergo an experience is to receive another inflection and another form from the other as well as to give the other these changes in return” [Malabou, Plasticity 41]), Stańczak’s sculptures are a self-reciprocal mechanism that invokes a transitory condition both for the viewer and the artist. Let us turn again to Verwoert who places additional stress on an array of affects the artist must have been going through as well as the levels of physical strength, stamina and persistence necessary to strip the objects down; in the end, one more party bared in the process is Stańczak himself (72). It is in this solipsistic closure, with the matter of the work deaestheticized and in flux, that the artist’s sculptures find close correspondence with Williams’s operations on signs, words and grammatic codes. Just like the bare and delyricized basic components of writing which make up the poet’s works, Stańczak’s self-referential sculptures invite one to let themselves be revealed as nothing more than quotidian objects, stripped of their surfaces and insides and so bereft of claims for a sense of Malabouian/Derridean presence. As such, both praxes signal the crisis of signification and representation, letting forms live through their own deconstruction to see them construct anew in a permanent dialectics of the plastic and the graphic.

But, following once more Malabou via Heidegger, there is also a kind of alterity to the absolute alterity—the plastic and unrelenting convertibility of forms is the rule, yet what more could be said about the inner dynamics of inverted sculptures? Why, instead of simply eradicating the items, Stańczak decided to turn them inside-out? Transforming the objects, yet aiming for a form as approximate as the original one is where another form of plastic metabolism resurfaces; since, as posited by Heidegger, there is no otherness beyond essence, “metamorphosis makes it possible to discover the other ‘in what is essential’” (qtd. in Malabou, Plasticity 41). As Malabou continues, this type of otherness “reveals first the strangeness of its essence there where an outside is lacking . . . [which brings it close to a] common definition of the fantastic, in which the frightening, the surprising, and the strange always arise from that which is already there (41). This uncanny aura of Stańczak’s altered items, making for a different type of plasticity, cannot be denied and is perhaps what Verwoert notices when he claims that

[i]n being bare, Stańczak’s sculptures are highly alive. . . . It’s the strangest thing: by virtue of being bare, you would assume, the sculpture should have something “reductive” or “subtractive” about them. But they don’t. . . . Nothing is taken away. Something is given. Something that was maybe already there. (76)

Given the context of a plastic reading of Stańczak, the inflicted damage is by no means insignificant—in The Ontology of the Accident Malabou specifies the surplus value of destruction: “Something shows itself when there is damage, a cut, something to which normal creative plasticity gives neither access nor body: the deserting of subjectivity” (6), which further helps one to realize that “a power of annihilation [with no point of elastic return] hides within the very constitution of identity” (37). In this way Stańczak’s inverted sculptures prefigure “a form of alterity, when no transcendence, flight or escape is left” (11) and as such deprive the viewer of a sense of safety.

As I hope to have demonstrated, the radicalities of inside-out inversion, employed by Emmett Williams and Roman Stańczak in their artistic explorations of the respective fields of concrete poetry and sculpture, on the one hand, comport with many concerns of contemporary materialist criticism and, on the other, help to rethink creativity in extremis. Also, in a manner complementary to one another and to Malabou’s project, both artists’ works signal, excavate and enact various aspects of plasticity, such as the interplay between the plastic and the graphic or the metabolism of the non-transcendental essential and its other. At the same time, my discussion of Williams and Stańczak does not by any means wish to retrench the richness of their respective artistic idioms, nor does it in any way exhaust the potential for a more developed plastic investigation of their praxes.

Charting paths for further explorations, Malabou’s discussion of nerve information networks as necessitating new metaphors of representation bears affinity to models of meaning-making in concrete poetry. Specifically, the neuroplastic configurations of organizing human thought, which in Malabou’s view must supersede the no-longer-relevant model of writing embedded in the work of the graph and the trace, seem to strongly resound with the poetic format of constellation (perhaps best recognized as the trademark of Eugen Gomringer’s concretist idiom), which abolishes traditional syntax in favour of visual and typographic grammar. If, as wished by the philosopher, plasticity “may be used to describe the crystallization of form and the concretization of shape” (Plasticity 67), then it might be worth elucidating the ways in which neuroplastic “linkages,” “relationships,” and “spider’s webs” (60) hold analogy to crystalline and constellational compositions of poetic units in concrete poetry.

Finally, by corrupting the pragmatism and banality of quotidian items, Roman Stańczak’s modified objects urge the necessity to address and challenge the dominant capitalist mindsets, otherwise ideologically guised as progress and modernity. The irreversibility of forms inferred on the objects by the artist connects it to Malabou’s discussion of destructive powers of plasticity as contrasted with flexibility and elasticity; being plasticity’s hyper-capitalist ideological reverses, the latter fetishize conforming and returning to forms, while remaining oblivious to annihilation with no point of return. In a similar way, by stimulating “the defiant activity of words when they refuse to be merely containers for instrumental communication” (Dworkin 11) and abolishing traditional syntax “function[ing] as a forward movement” (Finlay qtd. in Perloff 28), concrete poetry may be seen as refusing to pander to—referencing Debord’s idea—“words work[ing] on behalf of the dominant organization of life” (qtd. in Dworkin 11), a model of human thought to which Malabou bids farewell.

Barad, Karen. “Posthumanist Performativity: Toward an Understanding of How Matter Comes to Matter.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, vol. 28, no. 3, 2003, pp. 801–31. https://doi.org/10.1086/345321

Beaulieu, Derek. “Text Without Text: Concrete Poetry and Conceptual Writing.” 2014. University of Roehampton, PhD dissertation.

Bernstein, Charles. “The Academy in Peril: William Carlos Williams Meets the MLA.” Content’s Dream: Essays 1975-1984, Sun & Moon, 1985, pp. 244–51.

Caldwell, Grant, “Visual Poetry—Crisis and Neglect in the 20th Century and Now.” Creative Explorations, vol. 4, no. 1, 2014, https://www.axonjournal.com.au/issues/4-1/visual-poetrycrisis-and-neglect-20th-century-and, accessed 15 Aug. 2022.

Campos, Augusto de, et al. “Pilot Plan for Concrete Poetry.” Concrete Poetry: A World View, edited by Mary Ellen Solt, Indiana UP, 1968, pp. 71–72.

Dworkin, Craig. Reading the Illegible. Northwestern UP, 2003.

Ellermann, Greg. “Plasticity, Poetry, and the End of Art: Malabou, Hegel, Keats.” Romanticism and Speculative Realism, edited by Anne C. McCarthy and Chris Washington, Bloomsbury Academic, 2019, pp. 197–216. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781501336416.ch-010

“Getty Research Institute Acquires Archive of Poet and Visual Artist Emmett Williams.” Getty Center, 3 Apr. 2020, https://www.getty.edu/news/getty-acquires-archive-poet-and-visual-artist-emmett-williams, accessed 1 Sept. 2022.

Hanson, Louise. “Is Concrete Poetry Literature?” Midwest Studies in Philosophy, vol. 33, 2009, pp. 78–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4975.2009.00193.x

Hurley, Michael D., and Michael O’Neill. The Cambridge Introduction to Poetic Form. Cambridge UP, 2012.

Malabou, Catherine. Plasticity at the Dusk of Writing: Dialectic, Destruction, Deconstruction. Translated by Carolyn Shread, Columbia UP, 2010.

Malabou, Catherine. The Ontology of the Accident: An Essay on Destructive Plasticity. Translated by Carolyn Shread, Polity, 2012.

Michalska, Dorota. “Roman Stańczak, Allegories of Flight. Polish Pavilion at the 58th International Art Exhibition—la Biennale di Venezia, 2019.” ARTMargins, 23 Sept. 2019, https://artmargins.com/roman-stanczak-allegories-of-flight-polish-pavilion, accessed 23 Sept. 2022.

Perloff, Nancy, editor. Concrete Poetry: A 21st-Century Anthology. Reaktion, 2021.

Plate, Liedeke. “New Materialisms.” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Literature, 31 Mar. 2020, https://oxfordre.com/literature/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.001.0001/acrefore-9780190201098-e-1013, accessed 26 Sept. 2022, pp. 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.013.1013

Scully, Matthew. “Plasticity at the Violet Hour: Tiresias, The Waste Land, and Poetic Form.” Journal of Modern Literature, vol. 41, no. 3, 2018, pp. 166–82. https://doi.org/10.2979/jmodelite.41.3.14

Shread, Carolyn. “Catherine Malabou’s Plasticity in Translation.” TTR, vol. 24, no. 1, 2011, pp. 125–48. https://doi.org/10.7202/1013257ar

“Sign.” Encyclopedia.com, 8 June 2018, https://www.encyclopedia.com/science-and-technology/computers-and-electrical-engineering/computers-and-computing/sign, accessed 29 Sept. 2022.

Tolman, Jon M. “The Context of a Vanguard: Toward a Definition of Concrete Poetry.” Poetics Today, vol. 3, no. 3, 1982, pp. 149–66. https://doi.org/10.2307/1772395

Verwoert, Jan. “Graced by Bareness. On the Work of Roman Stańczak.” Roman Stańczak: Life and Work, edited by Jan Verwoert et al., Nero, 2016, pp. 70–77.

Williams, Emmett. Schemes & Variations. Edition Hansjörg Mayer, 1981.

Williams, Emmett. Selected Shorter Poems, 1950–1970. New Directions, 1975.