https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0636-3294

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0636-3294University of Torino https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0636-3294

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0636-3294

The 2018 edition of the Sámi festival Márkomeannu elaborated a narrative about the future of both the environment and society by articulating fears of an oncoming apocalypse and hopes for Indigenous Sámi futures through a concept presented to festivalgoers via site-specific scenography, visual narratives, and performances. This essay, addressing the festival as a site of artistic activism, reveals the conceptual bases and cultural significance of the festival-plot in relation to Indigenous Sámi cosmologies, the past and the possible future(s) in our time marked by escalating climate change. I argue that Márkomeannu-2018, providing a narrative about the future in which, amidst the Western societies’ dystopic colonial implosion, Indigenous people thrive, can be regarded as an expression of Indigenous Futurism. Counterpointing 19th-century theories predicting the imminent vanishing of Indigenous peoples while positioning the Sámi as modern Indigenous peoples with both a past and a future, this narrative constitutes an act of empowerment. Sámi history and intangible cultural heritage constituted repositories of meaning whereas a folktale constituted a framework for the festival-plot while providing an allegorical tool to read the present.

Keywords: Sámi festivals, artistic activism, climate change, Indigenous Futurism

Colonial anthropogenic climate change[1] is increasingly threating the environment. According to Streeby, the physical and socio-economic ramifications of climate change will have a particularly destructive impact in the global South and in what she calls the “South within the North,” i.e. the Arctic and its local Indigenous communities, among them the Sámi, the only recognized Indigenous people of Europe (Guttorm). Climate change is already damaging the environment in the world’s northernmost regions. Such dramatic mutations are experienced by young generations bearing witness to how climate change is altering their ancestors’ worlds in unforeseeable ways.

Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia have partitioned Sápmi, Sámi peoples’ ancestral homeland, since the 16th century. Among the worst consequences of colonial encroachment, forced conversion to Christianity led to a gradual loss of Indigenous worldviews and ritual practices. Albeit highly localized and characterized by significant variations, Sámi worldviews shared some important features: no founder, no scriptural authority, no codified doctrines; fluidity, adaptability to socio-cultural changes. Sacred authority came from spirits by revelations in dreams and states of altered consciousness (Rydving). Indigenous Sámi worldviews were polytheistic and animistic, with humans sharing the world with other-than-human entities transcending most humans’ perception, their relations characterized by reciprocity and respect (Helander-Renvall 50–53).

In addition, the Sámi developed a profound understanding of nature, through centuries-old interaction with their surroundings. Experience-based knowledge of natural phenomena enabled Sámi societies to thrive in the Arctic, perceived by colonial settlers as harsh and inhospitable. Sámi months’ names testify to both Sámi’s deep knowledge of the Arctic environment and its natural cycles and to ancient subsistence activities depending on such knowledge (Bergman). Ancient Sámi societies most likely had a cyclical or spiralling understanding of time and temporality. Although influenced by cyclical models, following colonial assimilation and integration into hegemonic societies, today Sámi people live according to linear understandings of time (Helander and Kailo). Assimilation led to many other major structural changes including language shift. Only a minority of Sámi now speak one of the Sámi languages (Gaski). Despite persisting stigmatization, in recent decades scholars and activists have engaged in language revitalization processes (Pasanen).

However, colonialism persists in subtle forms. Critical analysis of the impact of mining, windfarms, dams and other forms of land-grabbing shows that Indigenous (and marginalized) communities suffer from destructive land-exploitation more than members of hegemonic cultures do. In Sápmi, these phenomena are widely attested, hindering Indigenous practices like reindeer-herding, a traditional Sámi subsistence activity based on the management of semi-domesticated reindeer herds seasonally migrating across the tundra. Reindeer-herding is obstructed by States’ regulations, increasingly changing ecological conditions and the expansion of multinationals’ environmentally-destructive activities: logging, mining, and energy production (hydro-electric dams, windfarms) along with pollution threatened pastures, forests and settlements, to the long-term detriment of local habitats and cultural-specific lifestyles. The multiple manifestations of colonialism have encountered various forms of resistance: in recent decades, politically-engaged Sámi artistic expressions have prominently articulated Indigenous Sámi resistance against the colonial overtones permeating Nordic societies.

Through the lens of the Márkomeannu festival, this paper examines a Sámi response to these challenges. In 2018, Márkomeannu engaged with hopes for, and fears of, what the future might bring. That festival edition offered its guests a highly articulated plotline implemented through site-specific art and a 3-day-long participatory performance in which they were co-opted as actors. The plotline, published on the Márkomeannu website, is set 100 years in the future and foresees the Earth wrecked by climate change and social inequalities. In this post-apocalyptic scenario, only Indigenous peoples have managed to preserve nature and culture in isolated enclaves framed as Indigenous sanctuaries, one of which Gállogieddi, where Márkomeannu takes places.

Site-specific artworks conveyed strong social and environmental messages grounded in contemporary concerns over the future of Sápmi while offering an emic perspective over Sámi pasts and present. This festival theme is ascribable to the literary genre of Indigenous Futurism, a theoretical lens I will use to address the meanings conveyed by Márkomeannu-2118. The reflections above make Márkomeannu-2118 particularly interesting for this issue of Text Matters because it enables observation of how Indigenous Sámi are trying to make sense of past, present, and future challenges deriving from anthropogenic climate change, socio-economic disparity, and colonial violence through written, visual and performative arts. Furthermore, it offers an emic perspective of Indigenous understanding of recent Sámi history in relation to environmental exploitation on the part of multinational companies and the Fennoscandinavian States, the latter seldom publicly perceived as colonial powers exerting violence against local Indigenous people. Epitomizing Indigenous resilience while embodying hope, Márkomeannu-2118 symbolizes Indigenous creativity and politically-engaged cultural activism, challenging Western understandings of apocalypse while calling for action against the potential devastation of climate change.

This article develops themes I addressed in my PhD thesis, for which I conducted 16-month-long fieldwork (employing qualitative methods such as semi-structured in-depth interviews and participant observation) in Sápmi, as a young, female Italian anthropologist. My sources for this essay include interviews with the Márkomeannu-2018 CEO and written and/or visual material from the festival, as well as my own fieldwork observations while a volunteer at Márkomeannu-2118.

Scholars (see Whyte, “Indigenous Science (Fiction)”; Trexler) agree that Indigenous Futurism–a term coined by Indigenous scholar Grace Dillon—constitutes a powerful means for imagining a future that, albeit devastated by colonial anthropogenic climate change, allows Indigenous peoples not only to survive but to thrive. Dillon developed Indigenous Futurism from “Afrofuturism,” a cultural- philosophical movement analyzing the intersection of technology and African diasporic cultural expressions. Grounded in postcolonial theory, Afrofuturism encompasses understandings of history, time and temporality diverging from Western ones, speculating about realities in which Black identities are normative rather than marginalized. Built upon these premises, Indigenous Futurism articulates Indigenous perspectives of not only the future but also the past and present. Counteracting Indigenous absence from mainstream speculative genres (Medak-Saltzman; Streeby), Indigenous Futurism offers a means of projecting Indigenous peoples not just as individuals but as communities in the future, providing a way of counteracting Western narratives, rooted in nineteenth-century positivist social sciences that excluded Indigenous peoples from the future, thus making this movement an act of resistance against colonialism.

In Indigenous-sensitive scientific literature, this aspect is often framed through an intergenerational approach highlighting that the authors’ present is past generations’ future and their lifespan is their descendants’ past (Claisse and Delvenne; Medak-Saltzman; Streeby), as Whyte explains in his 2017 article: “Our Ancestors’ Dystopia Now: Indigenous Conservation and the Anthropocene.” Whyte emphasizes that devastating features associated with apocalypse in Western cultures are familiar to Indigenous peoples worldwide: many Indigenous societies have already experienced socio-cultural apocalypses in the past and are still living in their aftermath. Apocalypse concerns the future as much as the past (Horton 60) while also being lived in the present: radical relocation and concurrent cultural disintegration, often accentuated by the disruption of relations with non-human entities connected with ancestral homelands, meant “lost access to a culturally or economically significant plant(s) or animal(s) due to colonial domination” (Whyte, “Indigenous Science (Fiction)” 226). These animals or plants were not just inaccessible but as if extinct, a situation evoking Western post-apocalyptic scenarios.

Today, Márkomeannu is a well-established musical and cultural pan-Sámi festival held on the premises of the Gállogieddi Sámi open-air museum. Attended mostly, but not exclusively, by Sámi, Márkomeannu is a venue for Sámi artisans and artists to sell their products and duodji (handicrafts). Inspired by Sámi values—i.e. leaving no traces in nature of one’s passage–and contemporary environmental concerns, Márkomeannu aims at environmental sustainability. Clearly marked recycling and composting bins encourage waste sorting. Volunteers keep the festival-areas clean during and after the festival; free fresh water is available; served in compostable crockery, most of the dishes are locally produced.

In 1999, when it was first held, it was a small-scale event arranged by the local youth to celebrate their Márka-Sámi identity based on small-scale farming, long stigmatized by Norwegian and hegemonic reindeer-herding Sámi cultures alike. The festival’s name encapsulates its aims: Márkomeannu is a compound noun formed from two North Sámi words: Márku, designating the inner areas of the mountainous Stuornjárga peninsula,[2] and Meannu, meaning “noise/party” and “riot.” Márkomeannu is a party and a rebellion against cultural oppression in the Márka. Since its early editions, the festival has been characterized by ethno-political overtones, often engaging with political debates in Sápmi. Based on these premises, the theme of Márkomeannu-2018 is consistent with the festival’s spirit.

Although held in late July 2018, Márkomeannu was imagined to be taking place in 2118.[3] The shifting temporality between present and future was the core of the storyline. Introduced to the public through promotional material (videos, digital content and short texts) the festival-concept informed every aspect of the event framing public discussion, seminars, theatrical performances and art exhibitions. Fusing elements of reality, history, and Sámi non-Christian worldviews, the Márkomeannu-2118 plotline was encapsulated in the following text available on Márkomeannu’s webpage:

100 years have passed, and the earth is caught in unavoidable darkness. The year is 2118 and the world is about to collapse in power struggle, nuclear war, colonization and environmental disasters. The indigenous peoples have found a way to create their own sanctuaries hidden from the dark colonial power led by the power-hungry world chancellor Ola Tsjudi. The Sámi peoples’ sanctuary is at Gállogieddi, where they are trying to build a new world for themselves. The combination of new quantum technology and the rediscovery of the ancient Sámi belief have enabled society to return pioneers from ancient times. Over the years, much of the Sámi tradition and wisdom have disappeared in the struggle to survive as people. The pioneers are retrieved from the Saivo (the land of the dead) to assist in the creation of a peaceful, well-organized society. (Márkomeannu-2118)

Here, references to Sámi recent history (ancient Sámi beliefs being lost as consequence of cultural assimilation) and concerns for the future merge. The text describes possible repercussions of colonial anthropogenic climate change on Earth and human societies 100 years from now. By portraying an apocalyptic future, the organizers created a transposition of the present by exacerbating current political dynamics while warning about what might happen if today’s socio-environmental behaviour does not change. To do so, as I shall demonstrate, Sámi folktales worked as their framework.

Alternating tones characterize the text: gloom and pessimism, conveying a sense of helplessness, when describing Earth devastated by Ola Tsjudi, and hope and reassurance in the portrayal of Indigenous enclaves where nature and Indigenous societies survive. Cultural insiders were aware of a deeper message—encoded in the names—transcending the dichotomy. As the text suggest, Sámi from all Sápmi gather where Márkomeannu takes place: at Gállogieddi, a backcountry for a long time perceived as marginal not only by the hegemonic Norwegian society, but also by other Sámi communities (see Skåden, “In the Pendulum’s Embrace”).

The epithets employed in the festival’s introductory text constitute key elements for understanding the 2118 festival-plotline. The first character the reader encounters is the evil Chancellor Ola Tsjudi. This appellation evokes in Sámi audiences a set of emotions grounded in their history and folklore; whereas the title of chancellor conjures science-fiction scenarios, echoing the galactic enemy par excellence, the Star Wars series Supreme Chancellor Palpatine, the name “Ola Tsjudi” is culturally meaningful, as the then festival CEO explains:

It was kind of a fun reference for us. I’m on Sápmi’s Norwegian Side. When a person from the majority talks like a representative for the Norwegian society, he is an “Ola Nordmann,” or “Ola Norwegian.” . . . “Ola” stands for a prototypical colonizer’s male first name, and then “Tsjudi” was a hint to the stories about Čuđit people that used to raid Sámi villages. We wanted a name that had some fun puns to it, but also with some historical references that can be played with. We didn’t put a lot of talk into it, but we wanted it to be a pun. It was a bit funny, even though he was an evil controlling dictator. (Reinås Nilut)[4]

In other words, the common Norwegian name Ola has various connotations while metonymically standing for the stereotypical male Norwegian agent of the hegemonic colonial society engaged in exploitative actions, be they mining, logging or damming. The fictional surname Tsjudi bears strong connections with Sámi folklore as it is modelled upon Čuđit, the folklore enemies looming over Sámi siidas (social units). Cultural outsiders—like myself—were able to grasp Tsjudi’s implicit meanings only if we had previous knowledge of Sámi folktales but Sámi festivalgoers immediately identified the Chancellor with the enemies of their oral tradition. Ironically, the name is reassuring: Sámi are aware that, at least in folktales, their enemies are defeated. This conveys a message hidden between the lines: the Sámi will survive Ola Tsjudi.

In Sámi folktales, the “Čuđit” are fearsome human foes who plunder helpless Sámi communities, menacing the survival of Sámi society. Čuđit folktales revolve around a prototypical plot complying with a specific narrative repetitive in time and space: a band of merciless thieves murder Sámi to steal their belongings. The Sámi hero/ine manages to trick them and saves the rest of the community. To drag the enemy to their death, s/he resorts to her/his knowledge of the local landscape to her/his advantage. This hero/ine is known in Sámi as ofelaš (plural: ofelaččat), pathfinder.

Čuđit legends have long offered a means, grounded in Sámi cultural heritage, of understanding the present. The early twentieth-century Danish ethnographer Demant-Hatt, reporting the dark emotions Čuđit evoked in her interlocutors, wrote: “[W]ith Čuđit legends, a sense of helplessness and fear of a horrible and overbearing enemy that never shows compassion, still remains behind these narratives” (104). Demant-Hatt suggested that, albeit set in a timeless past, Čuđit stories articulated contemporary challenges for the Sámi. Čuđit were not ancient enemies but narrative elaborations of hostile neighbours (Swedes, Norwegians, Finns or Russians). Similarly, Frandy considers Čuđit stories as reflecting border dynamics revealing colonial violence and the threat this process continues to pose to Sámi communities, their lifestyles and cultural values.

Today artists resort to these paradigmatic antagonists to represent the new collective enemy of the Sámi: multinationals and colonial infrastructures exploiting sub/arctic natural resources in Sámi territories. Through the Čuđit, Sámi folktales have become important tools for dealing with crises, as Nils Gaup’s 1987[5] film Ofelaš shows. Set previous to the Christianization of Sápmi, Ofelaš offers a transposition of the ofelaš-Čuđit legend. In his analysis of Gaup’s film, Thomas DuBois considers the Čuđit to be dangerous not because “foreign, but rather, because they are evil: they have lost track of the unity which binds all things together and saves mankind from disintegration and depravity” (271). Almost 20 years after Ofelaš was produced, the prototypical figure of the Čuđit is explicitly used to criticize the exploitation of Sápmi through Indigenous frameworks. In 2016, the Sámi singer Sofia Jannok released a song entitled “Čuđit.” Translating the term as “colonizer,” she wrote on her Facebook webpage: “ČUĐIT is about the colonizing power.” Similarly, in a protest-poster, the anonymous Sámi artist-activist collective Suohpanterror[6] relied on Čuđit symbolism to convey a political message. Suohpanterror openly established a link between the contemporary mining exploitation of Sápmi and Sámi storytelling tradition, providing a reading of the exploitation of Sápmi grounded in Sámi frameworks (Cocq and DuBois). The poster reproduces a Čuđe, extrapolated from Gaup’s film, pointing a crossbow at the viewer. Logos of mining companies exploiting Sápmi dots the background. A text in Sámi dominates the poster. Cocq and Dubois translate it as: “Sámi people! The Čuđit are back and they want our minerals.” The message of Suohpanterror poster’s resonates with Sofia Jannok’s “Čuđit” and, in my opinion, is twofold: the exploitation of Sápmi is not a new phenomenon but its extent is, and the methods of the mining companies are modern counterparts to the Čuđit raids. Nevertheless, the poster implies that as in folktales the Sámi defeat the Čuđit through their knowledge of the local landscape, so the Sámi today will manage to overcome the threat of colonial exploitation of Sápmi.

When referring to the Čuđit, contemporary Sámi artists and activists resort to narrative structures and lexicon originating in ancient Sámi worldviews but that, encapsulating the centuries-long struggle for survival and self-determination, emerge as appropriate to denounce neo-colonial practices and other forms of exploitation and oppression in contemporary Sápmi. The Čuđit represent a form of symbolic continuity between the threats of the past and those of the present, threatening Sámi survival and therefore their future as a people. Thus, these folktale enemies have become an important element connecting contemporary Sámi experiences to the Sámi past, and to a Sámi future which will only exist as long as these adversaries are defeated. Through artistic criticism (Berg and Lundgren) and art-activism, art has become one of the most important ways to express concerns, fears and hopes about the future of the Sámi people.

Therefore, the future evil chancellor Ola Tsjudi symbolizes contemporary threats to Sámi society. This menace, in the Márkomeannu-2118 plotline, is tackled by heroes/ines from the recent Sámi past: the pioneers.

During the festival, the identity of the pioneers mentioned in the plot was revealed: they were Elsa Laula, Jakko Sverloff and Anders Larsen, three Sámi political activists who, between the late 19th- and the early 20th-century, contributed to the promotion and the protection of Sámi rights and cultural values. In the festival-material, the three activists are called “pioneers”[7] in English, veivisere in Norwegian, and ofelaččat in North-Sámi. Both veivisere and ofelaččat mean “those who show the way,” i.e. guides or pathfinders. In Sámi languages, ofelaš has come to mean “leader” but its importance lies in its original function as the hero/ine who saves the Sámi from the Čuđit. The three ofelaččat mentioned in the Márkomeannu-2118 text symbolize collective ancestors to all Sámi peoples, present and future. The encounter between the ofelaččat and their symbolic future descendants—incarnated by festivalgoers—delineates a dialogical narrative between descendants and ancestors (Whyte, “Indigenous Science (Fiction)”) at odds with Western linear conceptions of time but perfectly fitting within a spiral understanding of it, characteristic of many Indigenous understandings of time (De Vos 2–3).

According to the plotline, the ofelaččat were to guide the Sámi of the future in building a society inspired by Sámi values. The 2018 CEO Anne-Henriette Reinås Nilut explains:

Sámi people in 2118 had managed to build a quantum-bridge to connect with Saivo, the Sámi afterworld, where some spirits live. They call these three spirit-guides back to help, guide them. Each of them had a specific role. Elsa Laula was chosen for her ability to unite people in a cause.

The recalling of dead leaders to guide new generations of Sámi in establishing a Sámi society is a narrative device grounded in Sámi ways of transmitting experience-based knowledge across generations: the young shall learn from the elders. Contemporary Sámi societies are still facing challenges similar to those Laula, Sverloff and Larsen dealt with 100 years ago: resource exploitation, curtailment of agency and sovereignty, stigmatization, forced assimilation. Consequently, these past leaders can teach new generations how to cope with familiar threats. The plotline projected these challenges in an imagined future in order to foster discussion on how to tackle them in the present. Anne-Henriette Reinås Nilut explains: “We wanted to challenge our audience. We wanted them to attend the festival not only for partying, socializing and music, but also to provoke some thoughts about the plot: What is a safe place for us? . . . and remind ourselves that we could survive anything.”

Site-specific art enacted the festival-plotline through sound installations, scenography, and digital drawings portraying the Márkomeannu-2118 future. The 3-day-long performance Sáŋgarat máhccet (The Heroes Return) engaged the public, allowing festivalgoers to participate in the plot. To fulfill the festival-concept, Márkomeannu organizers relied on the expertise of Siri Broch-Johansen (playwright), Stein Bjørn (project manager), Anders-Ánndaris Rimpi (sound artist), Mari Lotherington (scenographer) and Nina Valkeapää, Ánte Siri, and Aleksi Ahlakorpi (actors), who produced a sensory experience transforming Gállogieddi into a futuristic Sámi landscape.

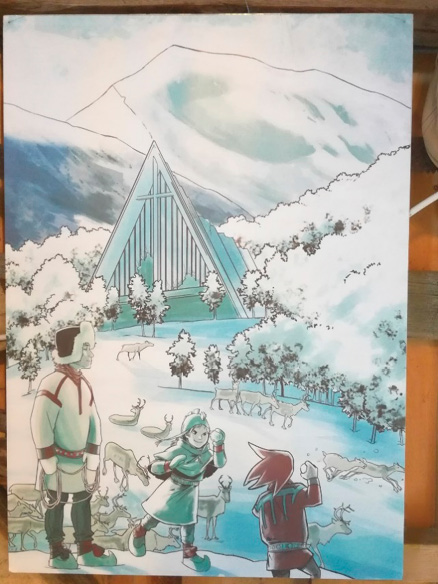

In addition, illustrator Sunna Kitti produced ten drawings visualizing the concept, especially what unfolded outside Gállogieddi, not staged but left to festivalgoers’ imagination. Kitti’s drawings depict two different contexts: six images focus on colonial violence and Sámi attempts to escape from it; and four focus on Sámi thriving in colonial-free Sápmi. As with the festival’s text, two contrasting notes characterize the illustration: the first six paintings are dark, violent, dramatic, their subjects suggesting both past and present events. Three of these images encapsulate both fears and optimism: in Leading Family to Safety, concerns over a contaminated Earth and hope for a safe future for Sámi peoples coexist. The drawings depicting a Sámi-managed future are light-coloured and reassuring scenes of joy, freedom, and harmony between Sámi and nature (as in All is Fine Again, fig. 1). The drawings draw upon actual events affecting Sámi peoples: for example, Nuclear Fallout evokes the effects of the Chernobyl disaster on reindeer-herding (Bostedt).

Fig. 1. Márkomeannu-2018, scenography, detail, 2018. A reproduction of Kitti’s artwork All is Fine Again is hanging on the barn’s wall. Photo by the author.

Fig. 2. Márkomeannu-2018, scenography, detail, 2018. A reproduction of Kitti’s artwork Forced Slaughtering is hanging on the Gállogieddi Museum’s barn. Photo by the author.

Forced Slaughtering (fig. 2)—showing shackled Sámi being forced to butcher their reindeer—evokes WWII episodes: Sámi in German-occupied territories were forced to slaughter reindeer to feed the soldiers and reindeer were killed upon the Nazi retreat (Evjen and Lehtola 34–35, 37). The image also alludes to colonial governments’ control upon reindeer-herding by evoking a recent judiciary case epitomizing the conflict between Sámi reindeer-herders and the Norwegian government. The latter ruled against a young reindeer-herder, Jovsset Ánte Sara, who had to reduce his herd to comply with Norwegian regulations.[8] Kitti describes “forced slaughter” as follows:

The Nordic countries have always had the custom of ensuring that a reindeer herder does not have too many reindeer, in which case the herd had to be slaughtered. For many, giving up their traditional livelihood is difficult . . . The dictator . . . can force the reindeer herders to work. When reindeer herding disappears, the area will be freed up to install other industries.

Similarly, in the festival narrative, the evil Chancellor wants to make the land profitable by installing factories and industries. This understanding of natural resources as something to be exploited rather than used and respected is at the core of the epistemological difference between Sámi and colonial approaches to resource-management. In the long term, the downsizing of reindeer-herding will threaten Indigenous economic subsistence systems, freeing the land for the colonizers and undermining the survival of the Sámi and their cultures.

Within the Márkomeannu-2118 framework, today-threatened Sámi cultures are the basis of daily life within Gállogieddi, a Sámi “Ecotopia” in a colonial dystopia. This ecologic utopia is a projection of aspirations towards Sámi sovereignty and relationships with nature based on reciprocity. The disintegration of Western institutions and the concurrent political/social/economic/environmental collapse emerge as the premises of Indigenous empowerment, epitomized in Kitti’s art in All is Fine Again (fig. 1). Set in Tromsø, this illustration shows reindeer roaming free in front of an adult man looking after the reindeer and two children playing, all dressed in Sámi clothing. In the background, the Sámi sacred mountain Sálašoaivi/Tromsdalstinden dominates the landscape while woods surround the Arctic Cathedral, a symbol of the city of Tromsø, here depicted as collapsing.

A political message lies between the festival-plot’s lines: if self-regulation and Indigenous sovereignty were the norm, Sámi peoples would thrive and they would do so by building on their ancestors’ collective knowledge. In contrast to Tsjudi’s tyranny, at Gállogieddi-2118 decisions are taken collectively, and the elders—represented by the ofelaččat—guide new generations. Gállogieddi-2118 thus resembles pre-colonial Sámi societies where decisions were collective, based on reciprocity and respect for non-human entities, offering an alternative to Western decision-making models (for instance, Scandinavian parliaments are the model for the Sámi on the Norwegian, Swedish and Finnish side of Sápmi). Nevertheless, Gállogieddi-2118 is not a re-enactment of the past. The Sámi of the future—as those of the present—embrace a certain version of modernity, symbolized in the plot by “quantum technologies” while valorizing Indigenous Sámi epistemologies, represented by the Saivo/land of the dead and the ancient Sámi belief ruthlessly persecuted by Christianity and “rediscovered” by the Sámi of the future. The passage refers to colonial violence which, through enforced Christianization, suppressed native knowledge, and to Indigenous empowerment through decolonial reappropriation of Indigenous epistemologies. Rejecting the commonplace that sees the Indigenous peoples as not engaged in modernity and challenging teleological progress-oriented narratives interpreting the present as inherently more “advanced” than the past, the mixing of futuristic technology and ancient spiritualities is a foundation of Indigenous Futurism (Whyte, “Indigenous Science (Fiction)”; Trexler). Although not thoroughly examined by the organizers, this element is central to Márkomeannu-2118, substantiating the hypothesis that the festival represents an example of Sámi Indigenous Futurism.

The call for Sámi sovereignty of Gállogieddi-2118, grounded in Indigenous epistemologies, constitutes a critique of social problems Sámi face today because of assimilation, and resonates with contemporary battles Sámi people fight against corporations taking advantage of Sápmi’s natural resources and strategic position. Sápmi, rich in metals, wood and fish, is the centre of Arctic Europe. This region, once the ice melts, will be fully navigable, allowing new trading routes connecting Asia and Europe. Then, the local environment and Sámi activities like reindeer-herding—already heavily damaged by climate change—will suffer even more from infrastructures such as harbours and railways (Finland is already considering an Arctic railway) upon whose construction the Sámi have little say.

Agency and resilience are the cornerstones of the whole Márkomeannu-2118 concept, as it envisioned not only the existence of Sámi peoples in the future but also their flourishing. By proposing a Sámi utopia within a Western-made dystopia, the festival’s concept constitutes an act of resistance in its own right: the background story—and the festival itself—disproves 19th-century social Darwinist theories envisaging the Sámi as relics of a long-gone past. Not only did Western scholars consider Indigenous peoples as destined to vanish—and hence without a future—but they construed them as lacking a proper past. Disregarding Indigenous oral cultures, many Western scholars considered Indigenous peoples as “peoples without history” (Wolf X, XVI, 18, 335). A double negation, that of past and future, thus relegated Indigenous peoples to perpetual temporal marginality (Ginsburg and Myers 29–31), living in an atemporal dimension at the fringes of the present (Fabian 37). The future of 19th- and 20th-century Indigenous peoples is the present of contemporary Indigenous peoples. Their existence is an act of resistance against colonial attempts to erase them in the past. Indigenous peoples across the globe have defied such understandings and, by engaging in Indigenous Futurism, are claiming their space not only in the present but also in the future. Imagining Indigenous existence in the future is a both a statement and an act of emotional and intellectual resilience (Medak-Saltzman 156). Furthermore, by envisaging Indigenous peoples thriving in the future, Indigenous Futurism not only offers ways of coping with the present, but also of standing up for Indigenous rights for generations to come.

The envisioning of a Sámi future at Gállogieddi builds on the strength that enabled the Sámi to survive as a people despite oppression, enforced assimilation, and land dispossession. This strength often derived from the close connection that the Sámi enjoy with their natural surroundings. As the imagined future Márka is separated from the wrecked Earth through an invisible barrier, festivalgoers had to go through to reach their haven (physically represented by a tunnel connecting the present outside the festival-area to the future inside of it), so locals perceived the mountains as protecting the Márka from Norwegian interference. Professor Geir Grenersen, who worked for many years in the Márka, explained to me (in a private conversation) that the mountains surrounding the Márka—making it difficult for Norwegians to reach Stuornjárga’s inner areas—were often conceptualized as the local landscape protecting its Márka-Sámi people from the Norwegian(ized) sea-culture. Thus, imagining a future Gállogieddi as a safe haven—visualized in the festival material as a bubble—actually transposes local conceptualizations of the Márka landscape and its protective function.

A call for action against colonial anthropogenic climate disaster is at the heart of the Márkomeannu-2118. The plotline urges festivalgoers to take actions to prevent the worst from happening, and the 2118-scenario from fulfilling itself. By envisaging a dystopic colonial world, Márkomeannu-2118 denounced past and contemporary socio-environmental malpractices and their catastrophic consequences, offering an insight into Sámi narratives concerning the connections between colonial violence and anthropogenic climate change. Such narratives, Whyte explains in “Indigenous Science (Fiction),” are often obfuscated by Western post-apocalyptic scenarios. Despite the gloomy future envisioned at Márkomeannu-2118, the storyline was designed as an inspiration and a means of fostering change. As Anne-Henriette Reinås Nilut explains, one of the festival-theme’s main purposes was to encourage guests to reflect upon the role that individuals have at this critical time in human history:

We made an extreme scenario where the world is no longer in danger, the irreversible damage is already done. At the same time, it plays on this, that there is only the now. We wanted to challenge people to discuss themes of time and lifestyles, putting them into a different time [that] is not the time they are now. So [the plotline] was practical because it helps explaining the backstory. But also, part of our goal was to inspire guests to discuss deeper issues.

Márkomeannu-2018’s focus on the consequences of colonial anthropogenic climate change positions the festival’s plot within the coordinates of Indigenous Futurism with influences from climate fiction. By creating an experiment of prefigurative practice through theatrical experience, engaging the participants in a future in which socio-climatic catastrophes have already occurred, Márkomeannu-2118 offered festivalgoers the opportunity to reflect upon the consequences of climate change and social inequalities. It also implicitly challenged Western economic systems exploiting resources and nature as if they were infinite disregarding the effects of this approach on the environment while urging festivalgoers to take responsibility for their future and that of their descendants.

Many of these plot elements resonate with cli-fi[9] topoi. According to Trexler, the incommensurable scale of the oncoming climate disaster is hard to comprehend in the present, but climate fiction, by envisaging life in a future shattered by anthropogenic (colonial) disasters, has the power to make climate change and its consequences visible to contemporary audiences, motivating them to change their behaviour in an attempt to avoid climate catastrophe. While cli-fi may help fight climate change by instilling panic, Indigenous Futurism helps imagine a future for Indigenous communities in which they are once again in control of their lands and cultures. By making possible futures tangible and visible, cli-fi and Indigenous Futurism have the power to inspire social movements while establishing connections among different temporalities and spaces, offering a means to reflect upon climate change (Streeby; Jensen). Through art, activism, and Indigenous Futurism, Indigenous peoples—and peoples of colour—address the intersection between climate change and colonial violence, by evoking the future—and claim their presence into it—through performance and imagination, making futures present from an experiential perspective, translating speculations into experiences. Through Indigenous Futurism, Indigenous authors and artists recall their people’s past while imagining their possible futures. Moreover, they allow the public to reflect upon the present in the hope of avoiding worst-case scenarios. Colonial anthropogenic climate change is a serious threat to the world and it may ultimately result in the collapse of ecosystems, species loss and environmental depletion, the devastating potential consequences of these phenomena on human societies ranging from economic collapse to radical relocation causing drastic changes in peoples’ lifestyles. As Márkomeannu-2118 shows, by engaging in cli-fi and Indigenous Futurism as a way of imagining Indigenous peoples in a near future shaped by climate change, Indigenous communities are trying to reclaim a future for themselves and their descendants.

The frame of Márkomeannu-2018 is embedded in the global Indigenous struggle for, and global concerns about, climate change and climate justice. As Hickey notes, Indigenous Futurism is expressed through written and visual arts and the enactment of the Márkomeannu-2118 storyline demonstrates performative arts’ engagement with this cultural movement. Márkomeannu-2118 epitomizes Indigenous Futurism at the intersection of decolonial and environmental activism, ethno-politics, and art because it aimed to raise awareness of climate change and social inequalities, and is thus in line with those features Hickey identifies as intrinsic in Indigenous Futurism. Through the lens of a culture that endured colonization, Márkomeannu-2118 envisions a Sámi future shielded from the downfall of colonial societies caused by their capitalistic greed, in a haven built upon the implosion of the colonizers’ society. In this dystopic utopia, Sámi cultures are the basis of continued existence. Besides reaffirming the Sámi presence in the present/future, this concept articulates contemporary concerns about climate change, especially in Arctic contexts. Whereas a key feature of Márkomeannu-2118 was hope, it also expressed Indigenous agency and resilience by being emblematic of cultural-artistic activism epitomizing both Indigenous creativity and political engagement. This also symbolizes a form of contemporary collective storytelling engaging the (festival) community and offering an alternative to Western perceptions of apocalypse grounded in a teleological linear understanding of time. Finally, it elicited action to prevent doom-laden climate change scenarios. Thus Márkomeannu-2018 may be regarded as a locus of resilience and resistance, as well as an arena for politically-engaged cultural activism that looks towards the future while treasuring the legacy of the Sámi past.

Berg, Lind, and Anna Lundgren. “We Were Here, and We Still Are: Negotiations of Political Space Through Unsanctioned Art.” Pluralistic Struggles in Gender, Sexuality and Coloniality, edited by Erika Alm et al., Palgrave Macmillan, 2020, pp. 49–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-47432-4_3

Bergman, Ingela. “Indigenous Time, Colonial History: Sámi Conceptions of Time and Ancestry and the Role of Relics in Cultural Reproduction.” Norwegian Archaeological Review, vol. 39, no. 2, 2006, pp. 151–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/00293650601030024

Bostedt, Goran. “Reindeer Husbandry, the Swedish Market for Reindeer Meat, and the Chernobyl Effects.” Agricultural Economics, vol. 26, no. 3, 2001, pp. 217–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-0862.2001.tb00065.x

Claisse, Frédéric, and Pierre Delvenne. “Building on Anticipation: Dystopia as Empowerment.” Current Sociology, vol. 63, no. 2, 2015, pp. 155–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392114556579

Cocq, Copellie, and Thomas DuBois. Sámi Media and Indigenous Agency in the Arctic North. Washington UP, 2019.

Demant-Hatt, Emilie. By the Fire: Sámi Folktales and Legends. Minnesota UP, 2019.

De Vos, Laura Maria. “Spiralic Time and Cultural Continuity for Indigenous Sovereignty: Idle No More and The Marrow Thieves.” Transmotion, vol. 6, no. 2, 2020, pp. 1–42. https://doi.org/10.22024/UniKent/03/tm.807

Dillon, Grace. Walking the Clouds: An Anthology of Indigenous Science Fiction. Arizona UP, 2012.

DiPaolo Marc. Fire and Snow: Climate Fiction from the Inklings to “Game of Thrones.” SUNY P, 2018.

DuBois, Thomas. “Folklore, Boundaries and Audience in the Pathfinder.” Sámi folkloristics, edited by Juha Pentikäinen, 2000, pp. 255–76.

Evjen, Bjørg, and Veli-Pekka Lehtola. “Mo birget soadis (how to cope with war). Adaptation and Resistance in Sámi Relations to Germans in Wartime Sápmi, Norway and Finland.” Scandinavian Journal of History, vol. 45, no. 1, 2020, pp. 25–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/03468755.2019.1607774

Fabian, Johannes. Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes Its Object. Columbia UP, 2014. https://doi.org/10.7312/fabi16926

Frandy, Tim. Introduction. Inari Sámi Folklore: Stories from Aanaar, edited and translated by Tim Frandy, The U of Wisconsin P, 2019, pp. xxv–xxvii.

Fredriksen, Lill Tove, and, Sigbjørn Skåden “Anders Larsen.” Store Norske Leksikon, https://snl.no/Anders_Larsen, accessed 11 Mar. 2022.

Gaski, Lina. “Hundre prosent lapp?”: lokale diskurser om etnisitet i markebygdene i Evenes og Skånland. Sámi Instituhtta, 2000.

Ginsburg, Faye, and Fred Myers. “A History of Aboriginal Futures.” Critique of Anthropology, vol. 26, no. 1, 2006, pp. 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308275X06061482

Grenersen, Geir. Personal communication with the author. 15 Apr. 2019.

Guttorm, Hanna. “Flying Beyond: Diverse Sáminesses and Be(com)ing Sámi.” Reconceptualizing Educational Research Methodology, vol. 1, no. 9, 2018, pp. 43–54. https://doi.org/10.7577/rerm.2703

Helander, Elina, and Kaarina Kailo, editors. “No Beginning, No End”: The Sami Speak Up—Circumpolar Research Series. U of Alberta P, 1998.

Helander-Renvall, Elena. “Animism, Personhood and the Nature of Reality: Sámi Perspectives.” Polar Record, vol. 46, no. 1, 2010, pp. 44–56. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0032247409990040

Hickey, Amber. “Rupturing Settler Time: Visual Culture and Geographies of Indigenous Futurity.” World Art, vol. 9, no. 2, 2019, pp. 163–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/21500894.2019.1621926

Horton, Jessica, L. “Indigenous Artists Against the Anthropocene.” Art Journal (Special Issue: Indigenous Futures), vol. 76, no. 2, 2017, pp. 48–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/00043249.2017.1367192

Jannok, Sofia. “Čuđit.” Facebook, 18 Dec. 2016, https://www.facebook.com/sofiajannok/posts/new-songmy-latest-single-release-from-this-fall-i-could-fill-an-ocean-with-all-m/10155895171653849/, accessed 28 Feb. 2022.

Jensen, Casper. “Wound-up Worlds and The Wind-up Girl: On the Anthropology of Climate Change and Climate Fiction.” Tapuya: Latin American Science, Technology and Society, vol. 1, no. 1, 2018, pp. 186–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/25729861.2018.1485245

Junka-Aikio, Laura. “Indigenous Culture Jamming: Suohpanterror and the Articulation of Sámi Political Community.” Journal of Aesthetics & Culture, vol. 10, no. 4, 2018, pp 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/20004214.2017.1379849

Kitti, Sunna, 2118. Instituto Iberoamericano de Finlandia, https://madrid.fi/expo/2118/, accessed 7 Nov. 2021.

Márkomeannu-2118. Márkomeannu, http://www.markomeannu.no/, accessed 15 Nov. 2018.

Medak-Saltzman, Danika. “Coming to You from the Indigenous Future: Native Women, Speculative Film Shorts, and the Art of the Possible.” Studies in American Indian Literatures, vol. 29, no. 1, 2017, pp. 139–71. https://doi.org/10.5250/studamerindilite.29.1.0139

Minde, Henry. “Assimilation of the Sami—Implementation and Consequences.” Acta Borealia, vol. 20, no. 2, 2003, pp. 121–46.

Ofelaš. Directed by Nils Gaup, performances by Mikkel Gaup and Nils Utsi, Filmkameratene A/S/Mayco/Norsk Film/Norway Film Development, 1987.

Pasanen, Annika. “‘This Work is Not for Pessimists’: Revitalization of Inari Sámi Language.” The Routledge Handbook of Language Revitalization, edited by Leanne Hinton, Leena Huss and Gerald Roche, Routledge, 2018, pp. 364–72. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315561271-46

Reinås Nilut, Anne-Henriette. Interview with the author. 19 Sept. 2020.

Rydving, Håkan. The End of Drum-Time: Religious Change among the Lule Saami, 1670s–1740s. Almqvist & Wiksell, 1995.

Skåden, Sigbjørn. Fugl. Cappelen Damm, 2019.

Skåden, Sigbjørn. “In the Pendulum’s Embrace.” Nils-Aslak Valkeapää/Áillohaš, edited by Geir Tore Holm and Lars Mørch Finborud, Nord-Norge Kunst Museum, 2020, pp. 39–61.

Streeby, Shelley. Imagining the Future of Climate Change. U of California P, 2017.

Trexler, Adam. Anthropocene Fictions: The Novel in a Time of Climate Change. U of Virginia P, 2015.

Whyte, Kyle P. “Indigenous Science (Fiction) for the Anthropocene: Ancestral Dystopias and Fantasies of Climate Change Crises.” Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, vol. 1, no. 1–2, 2018, pp. 224–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/2514848618777621

Whyte, Kyle P. “Our Ancestors’ Dystopia Now: Indigenous Conservation and the Anthropocene.” The Routledge Companion to the Environmental Humanities, edited by Ursula K. Heise, Jon Christensen and Michelle Niemann, Routledge, 2017, pp. 206–15.

Wolf, Eric. Europe and the People without History. U of California P, 2010.