https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8111-4998

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8111-4998University of Lodz  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8111-4998

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8111-4998

The article discusses Steve McCaffery’s The Basho Variations with a focus on various modes of transtranslation/transcreation/transaption of Matsuo Bashō’s famous frog haiku. The emphasis is placed on the complexities (of the processuality) of transtranslation which deliberately alters, distorts and reimagines the source text. The intercultural and intertextual quality of McCaffery’s poems is discussed in the context of multilevel references to classical Japanese aesthetics of haiku writing. The comparative reading of McCaffery’s and Bashō’s texts foregrounds the issue of events, or “frogmentary events,” and the importance of the role of the reader in completing poetic messages.

Keywords: haiku, frog, Steve McCaffery, Matsuo Bashō, translation, transcreation, transtranslation, event.

“The only thing that is different from one time to another is what is seen

and what is seen depends upon how everybody is doing everything.”

(Stein 497, 500)

“Haiku shows us what we knew all the time, but did not know we knew;

it shows us that we are poets in so far as we live at all.”

(Blyth, The Genius of Haiku 63)

“to see what lies / below / the lines”

(bpNichol, The Captain Poetry Poems)

This article looks at Matsuo Bashō’s famous frog haiku, and shows how it still inspires avant-garde poets in Canada. It shows how Steve McCaffery playfully and subversively writes through the seventeenth-century poem. In my analysis of this peculiar transcultural phenomenon I place emphasis on the complexities of transtranslation/transcreation/transaption which alters, distorts and reimagines the source text. The (cultural and textual) in-betweenness is seen (or heard?) in multilevel references to classical Japanese aesthetics of haiku writing, but is also manifested in allusions to Bashō translations by Allen Ginsberg and Alan Watts.

Brian Henderson notes that in the radical poetry of McCaffery and bpNichol “signs are ‘events’ we are to experience rather than traditionally read” (1–2). In my transactive reading of Canadian experimental poems, I link the philosophy of “frogmentary events” with classical haiku aesthetics where the power of suggestion plays the key role, and where the poem must be completed by the reader. Bashō famously said that “the haiku that reveals seventy to eighty percent of its subject is good. Those that reveal fifty to sixty percent we never tire of” (qtd. in Yasuda 128). If this holds true for traditional haiku poems, then we may expect that their verbivocovisual avant-garde incarnations will offer extra challenges for the reader.

One of the aesthetic categories in classical Japanese haiku is called yūgen (“profound mystery”) which, as Eliot Deutsch puts it, “teaches us that in aesthetic experience it is not that ‘I see the work of art,’ but that by ‘seeing the I is transformed’” (32). In Jeffrey Johnson’s view, yūgen is the key aesthetic category both in classical haiku and its avant-garde incarnations (16, 19–28). It is certainly in operation in Steve McCaffery’s Basho’s Variations which can be seen as an homage to Bashō but also to the avant-garde experiments of bpNichol and Dom Sylvester Houédard.

There are many surprising affinities between Bashō’s haiku and contemporary Canadian poetic experiments. As Masako Hiraga and Haj Ross point out (27), Bashō’s haiku was written at a gathering called kawazu awase (“frog meeting”), or as Haruo Shirane calls it, a “frog competition” (Traces of Dreams 17, 124), which was later edited and published by Senka, one of Bashō’s disciples (Shirane, Traces of Dreams 16). For the Japanese, the communal setting and dialogic responses to previous poems in haikai sequences are part of Bashō’s poetic tradition, but many Western readers often forget that Bashō’s hokku was the first poem in a long exchange in the form of linked verse. Shirane discusses this issue in his Traces of Dreams: Landscape, Cultural Memory, and the Poetry of Bashō, and particularly in his article “Beyond the Haiku Moment: Bashō, Buson and Modern Haiku Myths”; he notes that “the exchange, which continued to juxtapose and exchange various points of view, extended for 24 rounds and involved 41 poets” (Traces of Dreams 17). I mention all this because Mike Borkent discovers a similar dynamics in Barwin and beaulieu’s frogments from the frag pool: haiku after Bashō; he argues that the collection might be examined as a contemporary intertextual kawazu awase inspired by this initial gathering (195). In his insightful discussion of visual responses to Bashō’s haiku, Borkent shows many fascinating parallels in terms of imagery building, composition, and games of sense activated by the two Canadian poets, whose collaborative project has been inspired by Steve McCaffery’s Basho Variations. I would only add that the way I see it frogments from the frag pool is a kawazu awase in a double sense: first, it is a collaborative project, and second, it makes multimodal references to Bashō’s immanent poetics. McCaffery’s poetic project cannot be called a kawazu awase, but the idea of working along what Shirane calls “ vertical axis”—a reference (often parodic) or an allusion to, a twist on earlier poetry, from either the Japanese or the Chinese tradition (Shirane, “Beyond the Haiku Moment”)—is certainly in operation. More than that, McCaffery applies one more technique taken from the Japanese tradition; the “vertical axis,” understood as “cultural memory, a larger body of associations that the larger community can identify with” (Shirane, “Beyond the Haiku Moment”), is activated not only in his playful references to Bashō’s haiku, but also by widening the perspective of reading through the haiku by means of opening a number of intertextual (both literary and cultural) associations. The notion and practice of ex(change)/linkage will be immensely important here.

In his book Traces of Dreams, Shirane discusses the two axes: the horizontal (focusing on the present, the contemporary world), and the vertical (leading into the past, to history, to other poems):

Bashō believed that the poet had to work along both axes. To work only in the present would result in poetry that was fleeting. To work just in the past, on the other hand, would be to fall out of touch with the fundamental nature of haikai, which was rooted in the everyday world. Haikai was, by definition, anti-traditional, anti-classical, anti-establishment, but that did not mean that it rejected the past. (Shirane, “Beyond the Haiku Moment”)

For Shirane, any discussion of Bashō’s poetics (and responses to his writing) that does not take into account humor, transgression of established rules of poetry writing, and the emphasis on the innovation is in effect more or less reductive. Bashō was a master of “seeking new poetic associations in traditional topics” (Shirane, “Matsuo Bashō’s Oku no Hosomichi and the Anxiety of Influence” 182). As Koji Kawamoto notes, “[t]he key to [haiku’s] unabated vigour lies in Bashō’s keen awareness of the utility of the past in undertaking an avant-garde enterprise, which he summed up in his famous adage fueki-ryuko, which can be roughly translated as ‘permanence and change’” (“The Use and Disuse of Tradition in Bashō’s Haiku and Imagist Poetry” 709). Bashō’s notion of the new “lay not so much in the departure from or rejection of the perceived tradition as in the reworking of established practices and conventions, in creating new counterpoints to the past” (Shirane, Traces of Dreams 5). Bearing the idea of creating new literary and cultural counterpoints in mind, we can see McCaffery poetic experimentation as a fascinating continuation in the spirit of Bashō. But let us see first how it worked in Bashō’s poem.

It should be noted that in terms of its imagery—and particularly kigo, the seasonal word—Bashō’s poem was revolutionary and innovative, for, as Shirane argues, it worked “against the established conventions of the frog topos” (Traces of Dreams 17). The preface to Kokinshu, the first imperial anthology, describes “listening to the warbler singing among the blossoms and the song of the frog dwelling in the water” (Kawamoto, The Poetics of Japanese Verse 76). Bashō’s image of the frog departed from that poetic ideal:

According to one source, Kikaku (1661–1707), one of Bashō’s disciples, suggested that Bashō use yamabuki ya (globeflower!) in the opening phrase, which would have left Bashō’s hokku within the circle of classical associations. Instead Bashō worked against what was considered the “poetic essence” (hon’i), the established classical associations, of the frog. In place of the plaintive voice of the frog singing in the rapids or calling out for his lover, Bashō gave the sound of the frog jumping into the water. And instead of the elegant image of a frog in a fresh mountain stream beneath the globeflower (yamabuki), the hokku presented a stagnant pond. (Shirane, Traces of Dreams 15; see Crowley 57)

Commenting on the technicalities of imagery building, Chen-ou Liu stresses “the transformative power of the newness created by parodying established practices and cultural associations” (54). Yosa Buson (1716–83), one of the greatest masters of haiku, and Bashō’s admirer, composed the following meta-commentary which clearly affirms establishing a new perspective:

jumping in

and washing off an old poem—

a frog (qtd. in Shirane, Traces of Dreams 15)

Shirane refers to Ogata Tsutomu’s opinion that Bashō’s haiku is not only about the frog as such, but a peculiar invitation to his haikai partners, suggesting the following: “The frog has always been regarded as a creature that sings, especially in fresh streams, in the spring, but I want to look at the frog differently. Wouldn’t you be interested in doing this together?” (Shirane, Traces of Dreams 16). And when we look at the number of McCaffery’s poems in Basho Variations, we can be sure what his answer would be.

And before I begin my discussion of McCaffery’s poems, let me quote two more poems-responses to Bashō’s haiku. Clearly, both of them are parodies. The one written by Buson could be read as “a commentary on the pitiful situation of the haiku community of his day” (Liu 55):

Inheriting one of our Ancestor’s verses:

the old pond’s

frog is growing elderly

fallen leaves (qtd. in Liu 55, Crowley 55)

The one written by Ryōkan (1758–1831), the noted Zen priest-poet, is much closer in mood to McCaffery’s experiments:

a new pond—

not even the sound of

a frog jumping in (qtd. in Shirane, Traces of Dreams 17)

According to Hiroaki Sato, the author-editor of One Hundred Frogs: From Renga to Haiku to English, there are more than 135 English versions of Bashō’s frog haiku. Here is the original poem in transcription and four translations. The first two translations are made by two esteemed scholars of Zen Buddhism and Japanese aesthetics. Both Suzuki and Blyth wrote about the frog haiku extensively. Blyth’s translations and commentaries[1] influenced many innovative English poets, including Gary Snyder, Jack Kerouac, Kenneth Rexroth and Allen Ginsberg.

Furu ike ya

kawazu tobikomu

mizu no oto (qtd. in Sato 118)

Into the ancient pond

A frog jumps

Water’s sound! (translated by D. T. Suzuki; qtd. in Sato 154)

The old pond;

A frog jumps in,—

The sound of the water. (translated by R. H. Blyth; qtd. in Sato 154)

The old pond,

A frog jumps in:

Plop! (translated by Alan Watts; Watts)

The old pond

A frog jumped in,

Kerplunk! (translated by Allen Ginsberg; qtd. in Sato 164)

The first pages of McCaffery’s Basho’s Variations immediately foreground the issue of (double?) intersemiotic translation; here we find two versions of the frog haiku—one from Scotland (by Dom Sylvester Houédard), and one from Canada (by bpNichol)—and Watts’s and Ginsberg’s expressive translations seem much closer to them in terms of aesthetics.

I am calling them “versions,” as it would be difficult (and risky) to term all of them translations, as some English-speaking poets creatively play with the notion of a faithful translation, and they deliberately alter, distort and reimagine the source text. We can speak of a considerable number of creative transpositions, or “transcreations” of Bashō’s frog haiku rendered into English by bpNichol, Steve McCaffery (but also by Gary Barwin and derek beaulieu in their collaborative project frogments from the frag pool); one could even argue that they constitute a separate sub-genre.

“Transcreations,” the term bpNichol and McCaffery (the Toronto Research Group) adopted from Haroldo de Campos, foregrounds “the creative dimensions of translation as a form of writing” (Godard, “Translating Apollinaire” 208); translation here is viewed as “a project for transformation and renewal” (208). The link with twentieth century experimental writing (both avant-garde and, to use Marjorie Perloff’s term, arrière-garde texts) is of utmost importance; Barbara Godard notes that for bpNichol and McCaffery, just as for “Pound, Stein and Valery, ‘the translative act is an act by words upon words,’ one which enables the poet to ‘borrow entirely his content and invent entirely his form’” (Toronto Research Group 81; Godard, “Translating Apollinaire” 208).

In his most perceptive discussion of Barwin and beaulieu’s frogments from the frag pool, Mike Borkent coins the term “transaption.” He refers to Linda Hutcheon’s definition of adaptations as “palimpsestuous” and “inherently double- or multilaminated works” that do not value “proximity or fidelity to the adapted text,” but rather foreground “(re-)interpretation and (re-)creation” (Hutcheon 6, 148, 172), and he argues that some texts (like those written by Barwin and beaulieu) “can exhibit features of both types of intertextual relation, thereby straddling the borders of translation and adaptation” (Borkent 190). A peculiar combination of “textual experiences of fidelity and repetition (translation)” and “experiences of doubling and re-interpretation (adaptation)” (190) is at the core of his analyses; Borkent searches for the borderland between translation and adaptation to show how Barwin and beaulieu construe certain characteristic features of the content and style of Bashō’s haiku. My attitude in reading McCaffery’s poems will be similar.

Interestingly, the source text for McCaffery’s (and some of Barwin and beaulieu’s) transcreations is not necessarily Bashō’s Japanese haiku, but its concrete re-writings by Dom Sylvester Houédard and bpNichol, which is why terming them transtranslations is also quite justified. In his article titled “Rewriting and Postmodern Poetics in Canada,” John Stout tries to capture the essence of transtranslation: “Rejecting the notion of a faithful translation, a transtranslation takes liberties with its source text by making a lack of respect for faithful reproduction of pre-existing meanings and forms into a productive aesthetic strategy” (93). In Stout’s opinion, the phenomenon of transtranslation has become a notable trend in Canadian poetry ever since bpNichol published his text Translating Translating Apollinaire (that happened in 1979, but the fact that the book was republished in 2013 might be indicative of how influential this piece still is, especially for avant-garde artists).

One could argue that the practice of rewriting in Canadian poetry is part of a larger phenomenon. In Writing in Our Time: Canada’s Radical Poetries in English (1957–2003), Pauline Butling expands on Fred Wah’s notion of “re poetics” and writes what follows: “Re posits lateral, spiral, and/or reverse movements rather than the single line and forward thrust of avant-gardism. . . . A re poetics involves rewriting cultural scripts and reconfiguring literary/social formations. The goal is to change, not conserve, past and present constructions” (21). It should be noted that in contemporary Canadian poetry this process of “changing” is often playful, fluid and rhizomatic, similarly to Translating Translating Apollinaire, a project which, as Pauline Butling stresses, “disrupted notions of meaning and authorship” (68). The term rhizomatic is not a coincidence here, as both Butling and Barbara Godard draw links between Translating Translating Apollinaire and theories by Deleuze and Guattari, especially those pertaining to the porousness of authorship and the enfolding/unfolding of meaning. I shall come back to this “strand of narration” in the latter part of this essay. The first publication of bpNichol’s open-ended collaborative project included not only his own “translations”/transcreations/transtranslations, but also those by other writers (Dick Higgins, Steve McCaffery, Richard Truhlar, Douglas Barbour and Cavan McCarthy, to mention just a few). When discussing Steve McCaffery’s Basho’s Variations, we need to see them “in alignment” with bpNichol’s school of transmission; instead of traditional practice of translation as from one language to another, these artists are mainly interested in inventing other modes (such as Nichol’s “sound translation,” or his “walking east along the northern boundary looking south”). As Henderson aptly notices, “all these versions of the poem compose a kind of ‘Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,’ but without the blackbird. . . . But they are certainly play—play that renders language opaque except as far as vectors of change can be followed from one version to another” (29). Henderson stresses that as the “Translating Translating” in the title suggests, “we are urged to look into the writing, not out from it to conventional meanings” (29). McCaffery’s book can be considered a major contribution to this eccentric (non)genre, and it will definitely make the readers look into the writing. Similarly to Translating Translating Apollinaire, The Basho Variations foregrounds the relation between the play of form and sense (but also (non)sense) in the shifting meanings that are produced with each rewriting/writing through (see Godard, “Translating Apollinaire” 210).

Let me come back to Brian Henderson’s argument about signs as “events” we are to experience rather than traditionally read in McCaffery’s and bpNichol’s poetry. “In short,” he says, “it is a transformation of what reading is that such poetry demands” (2). As McCaffery himself explains: “[A]n issue formulates itself between a reading (of words) and a perceiving (of events within a zone of syntax) in which to read is to risk association, in which association in itself is to risk encounter with chaos” (“Notes” 42). Thus, “reading becomes perceiving,” Henderson concludes (2). I think that in reading poems by bpNichol and McCaffery one needs to learn how to see, how to notice signs that are there, even if they are to some extent invisible. I am interested in the philosophy of the event in Bashō’s haiku and its truly playful (often verbivocovisual) re-readings which form something that we may call “frogmentary events.”

Steve Odin notes that in the Japanese tradition of aestheticism we may speak of “a variety of highly refined, elegant, and pervasive qualities of atmospheric beauty such as aware (sad beauty), yūgen (profound mystery), wabi (rustic poverty), sabi (loneliness), shibumi (elegant restraint), mu (negative space), iki (chic), and fūryū or fūga (windblown elegance)” (99). Many critics agree that in classical Japanese haiku yūgen plays a special role. As Eliot Deutsch puts it, yūgen “teaches us that in aesthetic experience it is not that ‘I see the work of art,’ but that by ‘seeing the I is transformed’” (32). But how does it work?

In his informative Zen and the Japanese Culture, D. T. Suzuki begins his discussion of the quality of yūgen by referring to the meaning of the word itself; we learn that is it a compound word yū (meaning “cloudy”) and gen (meaning “impenetrability”), and the combination meaning “mystery,” “unknowability,” “obscurity,” “beyond intellectual calculability” (Suzuki 220). As I have already mentioned in the introduction, Jeffrey Johnson views yūgen as the key aesthetic category both in classical haiku and its avant-garde incarnations. It is certainly in operation in McCaffery’s Basho Variations. In order for us to grasp the importance of yūgen both in the frog haiku and in Canadian transcreations/transaptions/transtranlations, we need to come back to D. T. Suzuki and his detailed description of the complexity of yūgen dynamics:

An object so designated is not subject to dialectical analysis or to a clear-cut definition. It is not at all presentable to our sense-intellect as this or that, but this does not mean that the object is altogether beyond the reach of human experience. In fact, it is experienced by us, and yet we cannot take it out into the broad daylight of objective publicity. It is something we feel within ourselves, and yet it is an object about which we can talk, it is an object of mutual communication only among those who have the feeling of it. (221)

And as if this description was not enough, Suzuki goes on to say that yūgen “is hidden behind the clouds, but not entirely out of sight, for we feel its presence, its secret message being transmitted through the darkness however impenetrable to the intellect” (221); he immediately adds though that “it would be a great mistake if we took this cloudiness for something experientially valueless or devoid of significance to our daily life” (Suzuki 221).

In his article titled “Rewriting and Postmodern Poetics in Canada: Neo-Haikus, Neo-Sonnets, Neo-Lullabies, Manifestos,” John Stout argues that “in haiku, an object seen in a particular moment in time shocks the perceiver into a new awareness of life’s mystery and strangeness” (89). We can only guess that in neo-haikus the idea of shocking the perceiver might be even more intense. Stout notes that McCaffery “stretches the haiku well beyond its traditional limits, turns it inside out, and reimagines it in fundamental ways” (89). Interrogating language, playing with the possibilities of form are crucial here, but the most important thing, in Stout’s opinion, is taking lyric poetry into new territory. The issue of perceiving presence/absence, and perceiving events will become a crucial element of the processuality of reading.

Since the beginning of his career, McCaffery has conceived of his translative project as an attempt to see “what is to be gained from a break with the one-dimensional view of translation” (Rational Geomancy 27). McCaffery describes the two coordinates of his project as “injunction and transgression respectively” (8x8 44). Even though he maintains the original intention of the source text, his translations usually foreground some marginal piece of the original work: “Rather I try to take a deconstructive approach [to translation] by locating certain areas of suppressed preinscription within the source texts and then bringing these preinscriptions to an inscriptive surface: the target texts. This frequently resulted in radically different texts, but were all authenticated by these suppressed preinscriptions” (8x8 45).

As I have already mentioned, McCaffery’s collection offers new and surprising, mind-bending versions of Bashō’s haiku. Even the titles give us an idea of McCaffery’s range of forms and discourses: “THE GASTRONOMIC BASHO” (for Daniel Spoerri), “THE GOLF COURSE AND ANIMAL RIGHTS BASHO,” “THE SUPREMATIST BASHO” (for Kasimir Malevich), “THE PRESBYTERIAN BASHO,” “THE HINDU ARYAN BASHO,” “THE DINGBBAT BASHO,” “A LEWIS CARROLL BASHO” (for Jean-Jacques Lecercle). The last is comprised of two lines which (just like any other poem in the collection) contain the essence of McCaffery’s exercises in style:

Alice through the Looking-Pond

where no word means the same thing twice

Words and proliferation/dissemination/fluidity of meaning, achieved (?) or maybe (dis)/(un)covered (?) once Alice “swims” through the Looking-Pond? Perhaps Alice does not have to do anything in order to go through the Looking-Pond; perhaps her reflection in the Looking-Pond (the Pond that Looks) does the trick. . . . Nothing is certain here, no fixed image/scene is given. The readers must activate their “imaginative empathy” (Addiss 12) in order to enter the scene. We are not given 50-60% of the image content that needs to be complemented by the reader (Suzuki); this is definitely less than 50%.

The mystery and lack of “countours” may take other forms. The fluidity of meaning and processuality of reading is even more pronounced by the fact that some minimalist poems are three pages long (each subsequent page is occupied by only one word). Also, page numbers are not given—but who needs page numbers in a book which attempts to poetically affirm the non-dualistic framework of mind which favours interdependency over clear-cut definitions?

Speaking of poetic visionaries equally strongly attracted to the idea of non-duality, the book opens with three poems: Matsuo Bashō’s frog haiku in transcription, Dom Sylvester Houédard’s famous “frog / pond / plop” and bpNichol’s “fog / prondl / pop.” What follows is an astonishing number of multimodal transtranslations. The collection might be titled Translating Translating Basho, as each of these texts brings new preinscriptions to an inscriptive surface.

Quite surprisingly, The Basho Variations is categorized by the Canadian Cataloguing and Publication data as a work of translation. In an interview with Ryan Cox, McCaffery offers a comment regarding this peculiar categorization. He says:

[I]t’s an interesting categorization that I’m happy to live with. Certainly, translation and creative translation, maverick translation, has been a long interest of mine, which I developed both with Dick Higgins when we developed the notion of the allusive referential, and with bpNichol in some of the first research reports of the Toronto Research Group. Can you creatively mistranslate?

The answer to this question is obviously: Yes!

The poem which opens the collection, titled “PROEM: THE LOGIC OF FROGS # 383” (dedicated to Dick Higgins), contains this passage:

– what happens here?

– a translation? or an allusion?

– perhaps the translation of translation itself?

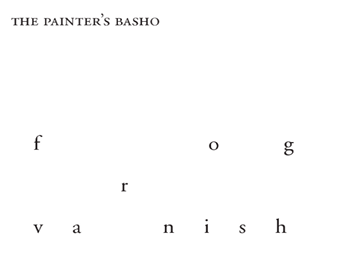

So many question marks in only three lines of the first p(r)oem. McCaffery’s translative commitment is to the absent, the latent, the silent, the other. One of his favourite “areas of suppressed preinscriptions” (8x8 45) is obviously linguistic materiality. For instance, in his verbivocovisual constellation titled “THE PAINTER’S BASHO,” McCaffery chooses to convey the ephemeral signifier over the eternal signified.

This poem exemplifies McCaffery’s favourite kind of transcreation that may actually encompass many routine semiotic acts, including simple rewording, arrangement and interpretation. It might be seen as a classical “borderblur,” a “transgressive form located between the verbal and visual arts, and . . . between translation and adaptation as well” (Borkent 192). Borkent takes this term from bpNichol, who attributes it to Dom Sylvester Houédard, and defines it as “poetry that arises from the interface” (Miki 134). It is no coincidence that the name of Houédard should appear, as the poem becomes a peculiar meeting point of three masters of concrete poetry and concrete philosophy. “THE PAINTER’S BASHO” comes, to use bpNichol’s words in The Cosmic Chef, “from that point where language &/or the image blur together into the inbetween & become concrete objects to be understood as such” (78).

This minimalistic design invites the reader in; it encourages the reader to enter the scene and co-create the meaning. The working of the poem is based on the “shimmering” of the sign imperceptibly shifting its semantic course: foggy background (of a pond) in the first line with a frog entering the scene, and then the frog vanishes in the third line leaving (?) a layer of varnish; but this painterly scene foregrounding shimmering signification may be pointing to an act of “varnishing” oppositional distinctions, of going beyond the opposition of visible/invisible, present or absent; certainly, what we are witnessing and experiencing here is the absence of certainty. To conceal and to reveal are two aspects of the same phenomenon, McCaffery seems to be saying.

McCaffery is a master of playful open-ended poetic narratives. The mystery of the pond scene is even more noticeable in “THE METAPHYSICAL AND ZEN CHARTERED ACCOUNTANT’S BASHO” where the brevity of haiku is stretched to its limits and turned into a self-reflective poem of questions in search of balance (also in accounting):

was it the frog or the pond

that jumped into the poem?

did the poem hold one

or both of them?

how many frogs can a single poem hold?

how many poems to each pond?

“was it the frog or the pond / that jumped into the poem?”—what a thought-provoking question! This text belongs to a group of poems which attempt to question not only the course of events in the poem by Matsuo Bashō, but also playfully discuss the philosophy of the haiku as a poem about a particular event. I would argue that McCaffery subtly shifts the emphasis from what happened (the first two lines) to extratextual matters, especially in the last two lines. This brings me back to Stout’s argument about taking lyric poetry into a new territory. Innocent as they may seem, McCaffery’s simple questions open more links to Bashō’s haiku and its philosophy than one would imagine at first glance. Mindful reading of his poems (we should not be deceived by their apparent simplicity!) reveals hidden depths, usually in the form of “question marks.” These highly intertextual games of sense contain (multimodal: verbal, visual and sonic) references to various (literary, visual) texts of culture but also science (for instance cognitive science in “THE GHOST OR BOUMA SHAPE BASHO”).

McCaffery’s exercises in reading comprehension may manifest as an ingenious blend like the one in a poem titled “TO MAX ERNST: ALL MY LOVE BASHO,” or a complex structure of a frog-soliloquy such as one we find in “HAMLET’S BASHO.” “TO MAX ERNST: ALL MY LOVE BASHO” writes through Bashō’s haiku by making references to Houédard’s translation:

(Untitled poem by Dom Sylvester Houédard)

Mike Borkent aptly notices that this poem “dramatically reduces Bashō’s haiku to its key sensorial focus, enacting Houédard’s understanding of visual poetry as ‘Constrictive (contractive) constructive & coexistential’” (199). In Borkent’s view, Houédard reduces each line to its central, four-letter element, and lines them up in order to introduce “a sense of the letters interacting both vertically and horizontally” (199). More than that, the emphasis placed on the letter “o” and other circular typographic elements (like the final word “plop”) “further reflects the ripples on the pond’s surface and the final onomatopoeic phrase of Bashō’s haiku” (Borkent 199). In McCaffery’s poem, the emphasis on the letter “o” (“mizu no oto” in the original) is even more pronounced, it seems. If Houédard’s composition foregrounds the immediacy of poetic image—we can see all three words at once; they form a grid which activates a sense of symmetry and parallelism between words and letters (Borkent 199)—McCaffery decides to slow down the pace of reading. His poem is three pages long! Each word appears in big capital letters, centre-justified on separate pages, and the third page features a mysterious word “loplop” which obviously echoes Houédard’s “plop” sound, but more importantly it is preceded by two letters and thus the music of “plop” metamorphoses into the name of a birdlike character featured in prints, collages and paintings by Max Ernst. Through the heightened emphasis on the visual and the aural in this poem, “reading becomes an exploration of possibilities—sonic, lexic and/or iconic” (Henderson 1–2). In a way, by jumping into the pond the frog changes into a bird-like creature.

The same (?) frog enters a metaphysical meditation on the nature of action or rather non-action in “HAMLET’S BASHO.” And, surprising as it may be, we are coming full circle to Bashō’s revolutionary gesture towards the frog. As Liu puts it, “[i]nstead of giving ‘the song of the frog,’ Bashō focused on the water sound of a diving frog. . . . In juxtaposing these two seemingly incongruous worlds and languages of ga (elegance) and zoku (vulgarity), Bashō humorously inverted and recast established cultural associations and conventions of the frog” (54). As a result, he created a “parody of classical poetry that refers to the frog as expressive of romantic longing” (Crowley 57). McCaffery reverses the scheme, and plays the game in the opposite direction. In his two-page long poem, the frog enters the scene in Shakespeare’s play, and we read the most elegant song of the frog, a sort of soliloquy. Here is the beginning:

To

jump

or

not

to

jump,

that

is

the

ques

tion;

The poem reads vertically in the sense that most lines consist of one word (or syllable) in the manner of an ideogram. By following the frog’s inner voice speaking, the readers’ eyes move downwards, plunge in a way into the frog’s inner world of troubles, as it speaks of suffering “the / waves / and / ripples / of / out / rage / ous / wa / ter.” “HAMLET’S BASHO” reads vertically also in a metaphorical sense mentioned by Haruo Shirane; by moving along the vertical axis, McCaffery links the moment before the jump in Bashō’s poem with Hamlet’s indecision concerning his next move. The two columns of fragmented so-li-lo-quy fill the silence before the jump, and given the context of the play, the readers are not even sure whether the actual jump will take place (“To / swim, / per / chance / to / drown, / aye / there’s / the / rub”).

The focus on silence, the lack of words, the uncertainty and mystery of the scene features prominently in “THE GHOST OR BOUMA SHAPE BASHO.” Here, McCaffery uses the theory of bouma shape to accentuate or foreground the notion of latent meaning of words and the play of visible/invisible or present/absent that are at the core of Bashō’s poem. This poem is one of three poems which have been accompanied by notes at the end of the collection. McCaffery provides readers with the information about the term “Bouma Shape” as “used in cognition studies to refer to the sub-optical silhouette surrounding an individual word.” Some typographers argue that, while reading, people are able to recognize words by deciphering boumas, which is seen as a natural strategy for increasing reading efficiency. McCaffery’s poem unfolds on three subsequent pages; the readers can see the first two pages side by side, and in order to see the mysterious page three, they need to turn the page. This act simultaneously reveals and conceals the message of the poem. How does it work? Each page offers a new version of the same scene. Page one features three words: frog, pond, plop centre-justified in a relatively big size (but not in capitals), forming a sort of pillar of words; each word is surrounded by empty space. The second page presents the same words surrounded by boumas. Page three, the most mysterious of them all, shows only the contours of meaning, or three emptinesses, three meaningful spaces waiting to be deciphered:

It is no coincidence that this open-ended poem marks the end of the collection, leaving the reader at a loss concerning the actual action of the frog, the significance of the whole scene, and how the poem may res(pond) to Bashō’s haiku. One possible reading is that McCaffery suggests that the frog has disappeared into itself, or as Barwin and beaulieu put it:

o

frog leaping

into the centre of

itself (Barwin and beaulieu 76)

It seems that the idea of developing extraordinary reading efficiency and embracing the challenges that we encounter while reading complex transtranslations/transaptions is what informs McCaffery’s collection as a whole. Let me refer to one more poem by Barwin and beaulieu from frogments from the frag pool, clearly inspired by McCaffery’s Basho Variations. It opens their collection and by means of a minimalistic design conveys the idea of multi-faceted, all-embracing (all-encapsulating) transtranslation:

(every(all at(toge(frog)ther) once)thing)

(Barwin and beaulieu 7)

The frog is at the centre of the design, but it is enfolded in/by a number of “brackets”/“ripples” of meaning, “ripples” of sense creation. Everything, all at once, all cultural associations together, all games of sense in operation, simultaneously. With each poem readers face a different perspective of looking at the same scene from Bashō. This poem best sums up the processuality of transaption in McCaffery’s Basho Variations.

In her discussion of bpNichol’s Translating Translating Apollinaire, Barbara Godard speaks of a “configured logic” (configuration as information) as not given a priori, but rather made in the process “wherein an idea is grasped as ‘form-in-sense’” (Godard 210; Drucker 169). Godard links this process(uality) with what Deleuze and Guattari have to say about translative reworking, and which has (hopefully) been made visible in my analyses of written-through frog haiku: “[T]he text is potentiality without a unified essence or identifiable centre” (Godard, “Translating Apollinaire” 210); it manifests only in “planes of consistency” and “lines of flight” as an “abstract machine of assemblage in which it undergoes molecular change according to the charged vectors of desire” (Deleuze and Guattari 19). Godard adds that “language and textuality are events in this rhizomatic ‘logic of the AND . . . AND . . . AND’ (Deleuze and Guattari 36)” (“Translating Apollinaire” 210).

This is how we come full circle to my initial argument about the philosophy of “frogmentary events” in McCaffery’s translations of Bashō’s haiku. Now we can link the processuality of experiencing “events” in Basho’s Variations with the workings of translation seen (and functioning) as “fold.” Translation as fold intertwines “outside with inside in multi-directional movements of folding, unfolding and refolding” (Godard, “Translating Apollinaire” 210–11). “As fold,” Godard argues, “translation sets up a different geography of relations than ‘the abyss-in-need-of a bridge,’ one of variation and amplification rather than dualism and opposition, producing ‘change in the place of meaning’” (“Deleuze and Translation” 60). McCaffery’s poems seem to embody the dynamics that Godard so vividly describes. As a result, mindful readers have a chance to catch a glimpse of a Japanese literary practice that may be lost in translation, but found in transtranslation (see Borkent 210).

Addiss, Stephen. Haiga: Takebe Sōchō and the Haiku Painting Tradition. Marsh Art Gallery/U of Richmond in association with U of Hawaii P, 1995.

Barwin, Gary, and derek beaulieu. frogments from the frag pool: haiku after Bashō. Mercury, 2005.

Blyth, R. H. A History of Haiku, Vol. 1: From the Beginnings up to Issa. The Hokuseido, 1963.

Blyth, R. H. The Genius of Haiku. Readings from R. H. Blyth on Poetry, Life, and Zen. The British Haiku Society, 1994.

Borkent, Mike. “At the Limits of Translation? Visual Poetry and Bashō’s Multimodal Frog.” Translation and Literature, vol. 25, no. 2, 2016, pp. 189–212. https://doi.org/10.3366/tal.2016.0246

Butling, Pauline, and Susan Rudy. Writing in Our Time: Canada’s Radical Poetries in English (1957–2003). Wilfried Laurier UP, 2005.

Cox, Ryan. “Trans-Avant-Garde: An Interview with Steve McCaffery.” Rain Taxi, Winter 2007/2008, https://www.raintaxi.com/trans-avant-garde-an-interview-with-steve-mccaffery/, accessed 25 Sept. 2020.

Crowley, Cheryl A. Haikai Poet Yosa Buson and the Bashō Revival. Brill, 2007. https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004157095.i-310

Deleuze, Gilles, and Felix Guattari. Mille Plateaux. Éditions de Minuit, 1980.

Deutsch, Eliot. Studies in Comparative Aesthetics. Monographs of the Society for Asian and Comparative Philosophy No. 2. U of Hawaii P, 1975.

Drucker, Johanna. “Intimations of Immateriality: Graphical Form, Textual Sense and the Electronic Environment.” Reimagining Textuality: Textual Studies in the Late Age of Print, edited by Elizabeth Bergmann Loizeaux and Neil Friastat, U of Wisconsin P, 2002, pp. 152–77.

Godard, Barbara. “Deleuze and Translation.” Parallax 14, Jan. 2000, pp. 56–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/135346400249289

Godard, Barbara. “Translating Apollinaire after bpNichol.” One Poem in Search of a Translator: Rewriting “Les Fenêtres” by Apollinaire, edited by Eugenia Loffredo and Manuela Perteghella, Peter Lang, 2009, pp. 193–221.

Henderson, Brian. “New Syntaxes in McCaffery and Nichol: Emptiness, Transformation, Serenity.” Essays on Canadian Writing, vol. 37, Spring 1989, pp. 1–29.

Hiraga, Masako, and Haj Ross. “The Bashō Code: Metaphor and Diagram in Two Haiku about Silence.” Iconic Investigations, edited by Lars Elleström, Olga Fischer and Christina Llungberg, John Benjamins, 2013, pp. 25–42. https://doi.org/10.1075/ill.12.05hir

Hutcheon, Linda. A Theory of Adaptation. Routledge, 2006. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203957721

Johnson, Jeffrey. Haiku Poetics in Twentieth Century Avant-garde Poetry. Lexington, 2011.

McCaffery, Steve. “Notes on Trope, Text, and Perception.” Open Letter, vol. 3, no. 3, Fall 1975, pp. 40–53.

McCaffery, Steve. The Basho Variations. Book Thug, 2007. N. pag.

McCaffery, Steve, and bpNichol. Rational Geomancy: The Kids of the Book Machine: Reports of the Toronto Research Group. Talonbooks, 1992.

McCaffery, Steve, et al. 8x8: La Traduction a L’Epreuve. Ellipse, vol. 29/30, 1982.

Kawamoto, Koji. The Poetics of Japanese Verse: Imagery, Structure, Meter. Translated by Stephen Collington, Kevin Collins and Gustav Heldt. U of Tokyo P, 2000.

Kawamoto, Koji. “The Use and Disuse of Tradition in Bashō’s Haiku and Imagist Poetry.” Poetics Today, vol. 20, no. 4, Winter 1999, pp. 709–21.

Liu, Chen-ou. “The Ripples from a Splash: A Generic Analysis of Basho’s Frog Haiku.” Ripples from a Splash: A Collection of Haiku Essays with Award-Winning Haiku, by Chen-ou Liu, A Room of My Own, 2011, pp. 51–58.

Miki, Roy, editor. Meanwhile: The Critical Writings of bpNichol. Talonbooks, 2002.

Nichol, bp. The Captain Poetry Poems. Blewointment, 1970.

Nichol, bp, editor. The Cosmic Chef: An Evening of Concrete. Oberon, 1970.

Odin, Steve. Artistic Detachment in Japan and the West: Psychic Distance in Comparative Aesthetics. U of Hawaii P, 2001. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780824861506

Sato, Hiroaki. One Hundred Frogs: From Renga to Haiku to English. Weatherhill, 1983.

Shirane, Haruo. “Beyond the Haiku Moment: Bashō, Buson, and Modern Haiku Myths.” Haiku Reality, Summer 2011, http://haikureality.theartofhaiku.com/esejeng79.htm, accessed 25 Sept. 2020.

Shirane, Haruo. “Matsuo Bashō’s Oku no Hosomichi and the Anxiety of Influence.” Currents in Japanese Culture: Translations and Transformations, edited by Amy Vladeck Heinrich, Columbia UP, 1997.

Shirane, Haruo. Traces of Dreams: Landscape, Cultural Memory, and the Poetry of Bashō. Stanford UP, 1998.

Stein, Gertrude. “Composition as Explanation.” A Getrude Stein Reader, edited by Ulla E. Dydo, Northwestern UP, 1993, pp. 493–503.

Stout, John. “Rewriting and Postmodern Poetics in Canada: Neo-Haikus, Neo-Sonnets, Neo-Lullabies, Manifestos.” Public Poetics. Critical Issues in Canadian Poetry and Poetics, edited by Bart Vautour, Erin Wunker, Travis V. Mason and Christl Verduyn, Wilfrid Laurier UP, 2015, pp. 87–106.

Suzuki, Daisetz Teitaro. Zen and Japanese Culture. Routledge/Kegan Paul, 1959.

Toronto Research Group (bpNichol and Steve McCaffery). “Report I: Translation.” Open Letter Second Series, no. 4, Spring 1973, pp. 75–93.

Watts, Alan. “Matsuo Bashō: Frog Haiku (Thirty-two Translations and One Commentary).” Bureau of Public Secrets, http://www.bopsecrets.org/gateway/passages/basho-frog.htm, accessed 10 Oct. 2020.

Yasuda, Kenneth. “‘Approach to Haiku’ and ‘Basic Principles.’” Japanese Aesthetics and Culture: A Reader, edited by Nancy G. Hume, State U of New York P, 1995, pp. 125–50.