Brazil is a member state of the Golden BRICS and the largest economy in South America. It is a big market with a population of more than 200 million. Brazil has abundant mineral resources and agricultural resources. In recent years, China has imported significant soybeans and iron ore from Brazil. Chinese enterprises have comparative advantages in the construction of infrastructure and mineral resources exploitation, green energy, and construction machinery manufacturing. Some famous Chinese enterprises have made direct investments in Brazil, e.g. the BYD Brazil Solar Panel Factory and the Pure Electric Bus Chassis Factory were simultaneously completed and put into operation in April 2017[1]; the China State Grid established a branch in Brazil[2]. The Guangxi Liugong Machinery Co., Ltd. (hereafter abbreviated as “the Liugong parent company”) established a subsidiary in Brazil in 2009[3] and in 2015 it opened a new factory located in the modern equipment manufacturing industry cluster in Moggiguasu, Sao Paulo, Brazil. The Liugong factory area is about 15,000 square meters (3,600 square meters), and it is a comprehensive factory integrating manufacturing, accessories, and customer training[4].

In the long run, Chinese tax experts did not pay enough attention to the double tax treaty practice or tax system in Brazil. The publication of academic papers on Brazilian taxation in Chinese journals is very rare. Xue Wei (2021) analyzed the tax risks of the BRICS countries from the perspective of tax treaties and tax business environment, and came to the following conclusions: “firstly, there are significant differences in the overall business environment of BRICS countries. In recent years, both China and India have continuously and significantly improved their respective business environments, Russia and South Africa have the most favorable tax and business environments, unfortunately Brazil has the worst business environment. In terms of tax compliance costs, Indian taxpayers have to made tax payments the most frequently, and Brazilian taxpayers have to spend the most time on doing tax compliance. In terms of the expenditure on taxes and levies, Brazil is the highest and South Africa is the lowest. Secondly, there are differences in the time threshold of constituting a permanent establishment and differences in the withholding tax rates for passive income (including dividend, interest and royalties income) either, and there are differences in the negotiation procedures due to the BRICS countries have different domestic laws.”[5] The research team of the Xiamen Local Taxation Bureau (2017) conducted a comparative study on overseas tax credit systems in the BRICS countries from several aspects, namely the object of credit, the limit of credit, and the treatment of overseas losses, to evaluate the operational effectiveness of overseas tax credit systems in BRICS countries. Under the premise of respecting the differences in the tax systems of the BRICS countries, the research team of the Xiamen Local Taxation Bureau (2017) suggested that the construction of China’s overseas tax credit system should be strengthened and international tax cooperation among the BRICS countries should be optimized[6].

The above tax literature has not offered concrete tax guidance for China enterprises that intend to make direct investments in Brazil. As a potential investor to the Brazilian market, a typical Chinese investor would like to know: (1) whether an intermediary holding structure is appropriate in the investment to Brazil; (2) whether there is any tax-efficient channel to pay passive income from a Brazilian subsidiary to the Chinese parent company; (3) how to avoid double taxation for the profits sourced from Brazil; and (4) how to exit from the Brazilian market in the end in a tax-efficient manner. This paper will try to analyze the above questions on the foundation of performing case studies on the Chinese enterprises’ investments in Brazil. This paper will also discuss some provisions relevant to Chinese enterprises’ investments to Brazil contained in the latest China-Brazil double tax treaty and the protocol signed in 2022.

For a China parent company, in its preliminary phase of doing business in Brazil, it is necessary to consider the forms of doing business. For instance, the Chinese company named as “the Chery Automobile Co., Ltd.” experienced four phases. In the first phase, it carried out cooperation with Brazilian automobile sales agents under general agency model. In the second phase, it established self-operated 4S automobile stores in Brazil, phasing out the former general agency model. In the third phase, it set up a self-operated manufacturing base in Brazil and registered as a wholly-China-capital subsidiary based in Brazil. In the fourth phase, it converted its wholly-China-capital subsidiary into a joint venture with 50% shares held by a Brazilian automobile group and 50% held by China shareholder.

In the following parts, some special tax issues arising in different investment stages or cases for Brazil subsidiaries will be discussed. These investment stages include but are not limited to the selection of a holding structure in the beginning, the exit from the Brazilian market in the end, the overseas tax credit during the operation period, and the repatriation of passive income from Brazil to China in case the Brazilian subsidiary makes profits or is able to bear interest or royalties.

In section 2.1., the cases of making investment to Brazil by two China manufacturing enterprises – the Liugong group and the Chery Automobile Co. Ltd. – will be studied so that light can be shed on Chinese enterprises when they consider how to plan their holding structure compatible with the Brazilian domestic tax regimes and the double tax treaty signed with China. For the Liugong group case, see the details in 2.1.1; for the Chery Automobile Co. Ltd case, refer to the details in 2.1.2.

As mentioned above, the full name of the Liugong parent company is “Guangxi Liugong Machinery Co., Ltd.”. It is a listed company with its shares traded in the Shenzhen Stock Exchange (stock number: 000528). Its headquarters are registered and located in the Liuzhou City, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region. It started international business in the 1990s. The company has established four manufacturing bases in India, Poland, Brazil, and Indonesia, as well as four overseas research and development institutions in India, Poland, the United States, and the United Kingdom. It also has multiple marketing companies with complete machine, service, accessories, and training capabilities, and provides sales and service support to overseas customers through more than 2,700 outlets of more than 300 distributors. Liugong’s overseas business covers most countries and regions along the “the Belt and Road”.

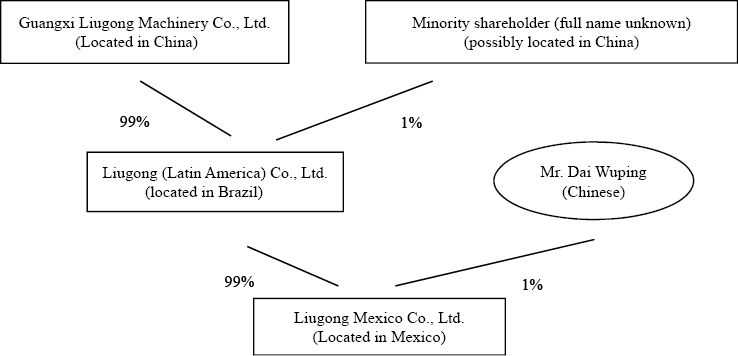

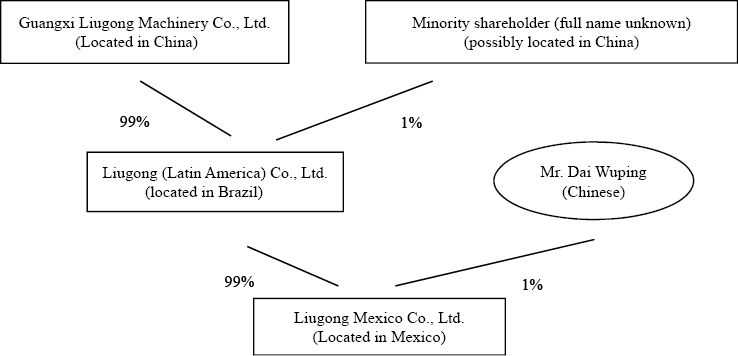

Liugong held the 24th meeting of the 5th Board of Directors on 6th November, 2008, and the meeting resolved to establish a wholly-owned subsidiary, Liugong Machinery Latin America Co., Ltd., with its registered office in Sao Paulo, Brazil, and a registered capital of 2 million USD. The company obtained the approval certificate of the Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China [2009] – Shanghe Overseas Investment Certificate No. 000490 – on 17th March, 2009, and received the registration certificate on 16th October, 2009. The Business scope of the Liugong Machinery Latin America Co., Ltd. is “research and development, manufacturing, distribution, leasing, service, and training of construction machinery products and spare parts”. The Liugong Machinery Latin America Co., Ltd. has been included in the consolidated financial statements of the company since the date of its establishment. In 2010, the incorporation capital of the Liugong Machinery Latin America Co., Ltd. was increased to 3 million USD, with 99% of its shares still directly held by the Liugong parent company and 1% shares indirectly held by its group associated company or person (note: the annual report of 2010 did not offer any information on the minority shareholder).

On 25th April, 2011, the Liugong parent company held the 10th meeting of the 6th Board of Directors. In the meeting, a resolution (LGGDZ (2011) No. 8–5) was passed to establish a sales company in Mexico – “Liugong Mexico Co., Ltd.”, which was in 99% owned by Liugong (Latin America) Co., Ltd., and in 1% owned by Mr. Dai Wuping, Senior Regional Manager of Latin America Company. As a subsidiary, Liugong (Latin America) Co., Ltd. was included in the consolidation scope of Liugong parent company.

The holding structure in year 2011 is set out as below:

From the above chart of the holding structure, it is obvious that the Liugong parent company did not use any intermediary holding company as the first step of making direct investment in Brazil. This holding structure for the Brazilian subsidiary is very different to the holding structure for the Polish subsidiary, where the investment path for the Liugong group’s Polish subsidiary is “China parent company – the Hong Kong intermediary company – the Netherlands holding company – the Poland subsidiary”.

Why did the holding structure for the Brazilian subsidiary not use any intermediary holding company? As a routine, Chinese investors, especially state-owned enterprises, usually use Hong Kong’s company as an intermediary holding company when they start their international business. Hong Kong is an ideal jurisdiction, since it adopts only source jurisdiction, does not exercise residence jurisdiction, its profits tax rate is only 16.5%, and it also offers preferential withholding tax treatments for the payment of passive income to a non-resident beneficiary party.

There is no tax treaty concluded between Brazil and Hong Kong. Since China concluded a double tax treaty with Brazil in 1991, this might be the reason that the Liugong parent company chose to make a direct holding to the Brazilian subsidiary without using any intermediary holding company. According to the “Dividend Exemption System” stipulated by the Brazilian domestic tax system, Brazil did not charge withholding tax on the payment of dividend to non-resident shareholders[7]. This might be the major reason to explain why the Liugong parent company chose to make direct investment in Brazil without using any intermediary holding company.

Similarly, another Chinese automobile enterprise also adopted a direct holding structure to making an investment in Brazil. The full name of this Chinese automobile company is “the Chery Automobile Co., Ltd”. It established its Brazilian subsidiary in 2010 with a registration capital of 0.4 billion USD. The Chery Brazilian subsidiary was incorporated in Sao Paulo, Brazil, in 2010. With regard to its business scope, it is “engaged in the import of complete vehicles, auto parts and related products and services, local procurement and construction of parts, manufacturing and sales of complete vehicles and parts, etc”. The holding structure of the Chery Brazilian subsidiary is as follows: the Chery Automobile Co., Ltd. holds 50.07% of the shares; the Chery (Shanghai) Investment Co., Ltd. holds 34.19% of the shares; the Wuhu Purui Automobile Investment Co., Ltd. holds 34.19% of the shares[8]. In a word, the above three China shareholders hold all the shares of the Chery Brazilian subsidiary. No overseas intermediary company is used in the investment from China to Brazil.

According to the “Dividend Exemption System” stipulated by the Brazilian domestic tax system, Brazil did not charge withholding tax on the payment of dividend to non-resident shareholders[9]. This might be the major reason why China shareholders chose to make a direct investment to Brazil without using any intermediary holding company.

Unfortunately, the Chery Brazilian subsidiary suffered continuous losses and its three shareholders finally made a difficult decision, i.e. to sell 50% of the shares in the Chery Brazilian subsidiary to the biggest Brazilian automobile manufacturing and sales company, namely the “CAOA Group”. After this share transfer deal was complete, the Brazilian domestic automobile manufacturing and sales company, the CAOA Group, became a new shareholder of the Chery Brazilian subsidiary, holding 50% of its shares. This Chery Brazilian subsidiary became the first joint venture between China and Brazil.

No details were disclosed on the possible capital gains tax exposures for the above Chery Brazilian subsidiary. In this case, the sellers of the shares include three China shareholders, while the buyer is a Brazilian domestic group. Article 13 (Capital gains) of the double tax treaty effective in 2017 (note: the double tax treaty signed in 1991 between China and Brazil) did not clarify whether the seller’s residence country or the buyer’s residence country should have the exclusive taxing right on the possible capital gains sourced from the transfer of company shares. The transfer of Brazilian subsidiary’s shares should not be categorized as the alienation of immovable property (see Article 13.1), or gains from the alienation of movable property forming part of the business property of a permanent establishment (see Article 13.2), or gains from the alienation of ships or aircraft (see Article 13.3). The tax outcome of share transfer should be based on Article 13.4, “gains from the alienation of any property other than that referred to in paragraphs 1, 2, and 3, may be taxed in both Contracting State”. China charges capital gains to its residents according to the Chinese corporate income tax law. If Brazil also charges capital gains to the M&A target (note: the target company is based in Brazil, whose shares are sold by its former Chinese shareholders) located in Brazilian jurisdiction, there will be double taxation on the capital gains tax. In the above case of the Chery Brazilian subsidiary, since the Brazilian subsidiary made continuous losses for several years, there might be capital losses rather than capital gains. The tax saving might be one of the reasons the Chinese shareholders decided to sell 50% shares to a Brazilian automobile group. Similarly, the financial situations of other Chinese automobile brands that have made direct investments in Brazil by either establishing sales companies or manufacturing bases are not optimistic either. Poor profitability in the Brazilian market might to some extent eliminate the possible capital gains from double taxation in the future, even though no Chinese brands expect to make losses in any jurisdictions.

China and Brazil signed a protocol on 23rd May, 2022. Unfortunately, the protocol to amend the old version of double tax treaty (signed in 1991) does not provide any solution to the possible double taxation caused by capital gains issue arising in the transfer of subsidiary’s shares when the subsidiary is located in the other contracting state.

China’s standard corporate income tax rate is 25%. High tech companies recognized by Chinese governments or enterprises located in the west of China and fulfilling designated conditions enjoy 15% corporate income tax rate. The Liugong parent company enjoys 15% corporate income tax rate, since it is located in the west of China and meets other designated conditions.

However, Brazil levies a very high corporate income tax rate. In Brazil, the fundamental corporate income tax rate (abbreviated as “IRPJ” in Brazilian) is 15%. For the enterprise’s annual profits exceeding the Brazilian Real 240,000, a surcharge of 10% should be imposed on the exceeding part of profits; and the CSLL rate is 9%[10], where the tax base is the accounting profits after making adjustments based on tax law. Roughly speaking, the approximate nominal tax rate of the Brazilian federal corporate income tax for a big size and profitable enterprise is 34% (note: 34% = 15% + 10% + 9%). The Brazilian rough tax rate of 34% is much higher than China’s standard corporate income tax rate 25% and even much higher than China’s preferential corporate income tax rate of 15%. According to Article 23.1(1) and 23.1(2) of the Brazilian double tax treaty signed with China, China adopts the direct tax credit method and the indirect tax credit method to eliminate double taxation for profits sourced from Brazil. However, there is no way to eliminate the over-paid tax burden (the Brazilian tax burden exceeding the tax payable under the Chinese domestic corporate income tax law) indirectly borne by Chinese parent companies. This is an important issue that should draw the attention of the Brazilian tax authority. In order to eliminate the non-creditable profit tax burden arising in Brazil, Chinese enterprises have a motivation to control the annual profits of their Brazilian subsidiaries carefully within the threshold of no more than the Brazilian Real 240,000 in order to eliminate the non-creditable tax burden when the dividend is repatriated back to the Chinese parent company, since the Chinese corporate income tax rate is much lower than the Brazilian federal corporate income tax rate (IRPJ + IRPJ surcharge + CSLL). The big difference in corporate income tax rates is an important issue that might prevent Chinese enterprises from shifting profitable assets or functions or high risks to the Brazilian market in order to maintain a thin profit in Brazil. Under the arm’s length rule, limited assets, functions, and risks are commensurate with limited profits. The Chinese parent company and the Brazilian subsidiaries should carefully manage their supply chain and align their assets, functions, and risks in a reasonable way in order to justify the possible thin profits earned in Brazilian market. Obviously, it is a rational choice made by Chinese enterprises and also a choice driven by the Brazilian government’s high tax rate system, because no Chinese enterprises expect to make this choice if they have any other options.

Interestingly, Article 16.2(b) of the protocol signed on 23rd May, 2022, stipulates: “If, after the 23rd day of May 2022, Brazil agrees, in an Agreement or Protocol with any other State to rates that are lower (including any exemption) than the ones provided in Article 10, 11, and 12, then such rates shall, for the purposes of this Agreement, automatically be applied under the same terms, from the time and for as long as such rates are applicable in that other Agreement. However, in the case of dividends, such rate shall in no case be lower than 5 percent, and in the case of interest and royalties, such rates shall in no case be lower than 10 percent”.

The paragraph in the above Article 16.2(b) of the protocol is very similar to “the most-favoured-nation rate of duty” that is usually adopted in custom duty field, but under the double tax treaty context, it could be viewed as the most-favored-nation rate of withholding tax. This is a very good practice for Chinese investors, since after this paragraph comes into force, Chinese parent companies could enjoy preferential withholding tax rate if such a preferential withholding tax rate exists in other tax treaties signed by Brazil with other non-Chinese tax jurisdictions. Chinese investors do not need to make great efforts to do treaty shopping or do tax planning merely for the purposes of paying passive income from Brazil to China. This paragraph in the above Article 16.2(b) of the protocol also set a bottom line for the withholding tax rates – for dividend rates it cannot be lower than 5% and for interest rate, and royalty rate cannot be lower than 10%.

Article 13.4 stipulates:

If information is requested by a Contracting State in accordance with this Article, the other Contracting State shall use its information gathering measures to obtain the requested information, even though that other State may not need such information for its own tax purposes. The obligation contained in the preceding sentence is subject to the limitation of paragraph 3 but in no case shall such limitations be construed to permit a Contracting State to decline to supply information solely because it has no domestic interest in such information.

This section is of practical significance under the “Belt and Road Initiative”. The Chinese government cannot directly appoint its tax officials to overseas enterprises located in other countries for doing tax inspection as what it does in the PRC jurisdiction. After Chinese enterprises go abroad for investment – although the Chinese government has strengthened its document requirements for Chinese domestic parent companies to submit overseas investment information – it does not mean that Chinese domestic parent companies will provide complete and truthful information required by the tax bureau. Therefore, the central tax administration of the PRC has motivation to strengthen the exchange of tax information with countries along the “Belt and Road”. Due to the insufficient tax collection and management capabilities of the countries other than China along the “Belt and Road”, the Chinese government has already funded many training courses for tax officials from these countries. However, this does not mean that these countries along the “Belt and Road” have a strong motivation to collect and share tax information of Chinese enterprises, which are incorporated or based in investment destination countries, with China’s central tax authority or provincial tax authorities. The reason behind these countries’ lack of motivation is easy to explain, since the tax information might be more inclined to benefit the Chinese government unilaterally, unless the Chinese enterprise also avoids or even evades taxes in these host countries along the “Belt and Road”, thus giving an excuse for these host countries to charge more tax revenues. Moreover, in order to attract Chinese investments, these host countries have already granted Chinese enterprises some corporate income tax, value-added tax, and import tariff preferences specifically designed to attract international investment inflow. In other words, these host countries do not have the willingness to be very strict to Chinese enterprises in tax administration and tax collection matters, and they naturally do not feel the need to collect tax information more than their own needs. Perhaps these host countries have made some efforts to collect tax information and share tax information with China; however, if the tax information only benefits China unilaterally in the long run, and if, on the other hand, these countries cannot obtain sufficient compensation for their costs incurred in collecting the tax information unilaterally needed by China, sooner or later, it might turn out that the collection and sharing of such tax information only remains on paper and cannot be sustainable.

In the China-Brazil economic cooperation, due to China’s significantly stronger economic strength than Brazil, China is more often a capital exporter, unilaterally exporting capital to Brazil. As a capital importing country, Brazil might have motivation to protect Chinese enterprises that have already been established in Brazil. This is a justification for the Brazilian tax authorities to be unwilling to respond to China’s request for tax information sharing, because even if Brazil provides tax information, it will only facilitate the Chinese government to conduct tax inspections, charge under-paid taxes, and impose late payment surcharges or even fines on its Brazilian subsidiary’s ultimate parent company in China. This will undoubtedly weaken the Chinese parent companies’ ability to reinvest in Brazilian subsidiaries in the future, but the taxes, late payment surcharges, and fines collected by the Chinese government will not be shared with the Brazilian government. Therefore, in the absence of a tax-benefit-sharing mechanism between capital exporting countries and capital importing countries, capital exporting countries may not necessarily be able to obtain the benefits of obtaining assistance offered by capital importing countries in collecting and sharing tax information. This might be a common challenge faced by all capital exporting countries. What the Chinese government can do is to add a tax interests sharing paragraph to the tax treaty protocol between China and Brazil to address the imbalance of enjoying tax interests in bilateral tax information sharing in order to realize the sustainable sharing of tax information with the Brazilian government in the future. This tax information may be more inclined to benefit the Chinese government unilaterally. Of course, now this is just a literal clause, and Chinese tax government still needs to wait and see whether the Brazilian government will do its utmost to implement it as the Chinese government wishes. In fact, even if the Brazilian government does not make every effort to enforce the clause and instead uses its discretion to enforce it, it may be difficult for the Chinese government to raise objections to this, as whether to make every effort or not depends on the current resources and willingness of the executing party.

In summary, the proposal of this clause is aimed at overcoming the “self interest” nature of both contracting parties’ habitual shortness and protection of their own tax base. However, even if the clause overcomes the limitations of the “self interest” of both contracting parties at the time of contracting, this does not mean that the clause can effectively overcome the limitations of “self interest” of both contracting parties during its implementation stage. Regardless of its realistic implementation outcome, the proposal of this provision is indeed a constructive response to the tax information sharing provisions of previous tax treaties and the current situation of tax information sharing.

Article 14 of the protocol set out very lengthy and detailed conditions for obtaining the qualification of enjoying treaty benefits. Obviously, both China and Brazil have both interests in curbing tax treaty abuse. Brazil has a tradition of set out a white list and a black list for anti-avoidance purposes. Article 14 of the protocol might serve the purpose of discouraging investors to structure faked transactions or shell companies merely for tax saving purposes.

Due to the differences in double tax treaties and domestic tax systems, for Chinese investors, to invest in the European Union Member States such as Poland and to invest in Brazil translate into different tax issues. The differences in tax issues would lead to different tax plans adopted by Chinese investors.

Being aware of the tax directives applicable in the European Union or the domestic tax laws in each Member State is easier for Chinese investors, since English is a commonly used language in Europe. However, in Brazil, the official language is not English, but Portuguese. Nowadays, in China, it is very difficult to find any tax expert who is familiar with taxation and also speaks Portuguese, since only few Chinese universities specialized in teaching foreign languages teach Portuguese. Most of tax practitioners in China could not speak Portuguese. This is a realistic obstacle preventing Chinese tax experts or Chinese enterprises from managing the tax risks arising in the Brazilian market. One Deputy to the National People’s Congress of China, who is a Macau resident, suggested that Macau – as an area once having so close link with Portugal and nowadays still having some residents able to speak Portugal – should build up a bridge between China and Brazil, and make efforts to deepen the economic cooperation between these two.

Chinese enterprises prefer to choose Hong Kong as an ideal location to set up an intermediary holding company and then make an investment through the Hong Kong intermediary company to the European Union Member States or to other Asian Pacific countries. Unfortunately, Brazil has not signed any double tax treaty with Hong Kong. However, it is also a pity that Brazil did not sign any double tax treaty with Macau either. Due to Macau’s historical link with Portugal and due to Portugal’s historical link with Brazil, if Brazil signs a favorable tax treaty with Macau, Macau might have a chance to be viewed as an attractive tax jurisdiction by Chinese enterprises for establishing an intermediary holding company before Chinese enterprises make investments in Brazil.

Brazylia jest członkiem „Złotego” BRICS i największą gospodarką Ameryki Południowej. Chiny są także państwem członkowskim „Złotego: BRICS i drugą co do wielkości gospodarką na świecie. Wzmocnienie wzajemnej współpracy gospodarczej w zakresie handlu i inwestycji jest zgodne z interesami obu krajów. Na tym tle w artykule omówiono kilka zagadnień podatkowych pojawiających się w sprawach dotyczących inwestycji przedsiębiorstw chińskich w Brazylii, z perspektywy umowy o unikaniu podwójnego opodatkowania oraz protokołu podpisanego w 2022 r. Ze względu na różnice w umowach o unikaniu podwójnego opodatkowania oraz krajowych systemach podatkowych, dla inwestorów z Chin inwestowanie w państwach członkowskich Unii Europejskiej, takich jak Polska, oraz inwestowanie w Brazylii będzie wiązało się z różnymi kwestiami podatkowymi. Różnice w kwestiach podatkowych prowadziłyby do różnych planów podatkowych. Większość doradców podatkowych w Chinach nie mówiła po portugalsku. Jest to realna przeszkoda uniemożliwiająca chińskim ekspertom podatkowym lub chińskim przedsiębiorstwom zarządzanie ryzykiem podatkowym powstającym na rynku brazylijskim. Makau, jako obszar niegdyś tak blisko powiązany z Portugalią, a obecnie niektórzy mieszkańcy nadal mówią po portugalsku, miejmy nadzieję, że może zbudować pomost między Chinami a Brazylią, jeśli Makau będzie miało plan podpisania atrakcyjnej dla Chin umowy o unikaniu podwójnego opodatkowania z Brazylią przedsiębiorstwa, a także posiada konkurencyjny krajowy system podatkowy.

Annual Report of Liugong 2009. (柳工2009年年报).

Chinese Investment Boosts Long Term Economic Development of Brazil, People’s Daily, August 14, 2017, http://news.gxnews.com.cn/staticpages/20170814/newgx59915e9c-16436979-.1.shtml (access: 8.12.2023). (“中国投资助推巴西经济长远发展”, 人民日报, 2017年8月14日, 网址).

Du Pengqing. Liugong Brazil’s New Factory Completed and Opened, Becoming Liugong’s Third Overseas Factory, Guangxi News Network, April 14, 2015, http://www.gxnews.com.cn/staticpages/20150414/newgx552c9719-12588637.shtml (access: 8.12.2023) (杜鹏卿. “柳工巴西新工厂建成开业 成为柳工第三个海外工厂”, 2015年4月14日的广西新闻网).

Reporter Gao Feichang. Is Chery Suddenly Selling 50% Equity of Its Brazilian Subsidiary, Divesting Non-performing Assets, or Is There Another Mystery? Economic Observer, October 12, 2017. (记者高飞昌. 奇瑞突然抛售巴西分公司50%股权, 剥离不良资产还是另有玄机? 经济观察报, 2017年10月12日).

Research Group of Xiamen Local Taxation Bureau. A Comparative Study of Overseas Tax Credit Systems in BRICS Countries, Fujian Forum · Humanities and Social Sciences Edition, 2018, Issue 5, pp. 26–35. (厦门市地方税务局课题组. 金砖国家境外税收抵免制度比较研究,《福建论坛 人文社会科学版》, 2018 年第 5 期, 第26–35页).

Research Team on Investment Tax Guidelines for Countries (Regions) under the International Taxation Department of the State Administration of Taxation. Tax Guide for Chinese Residents Investing in Brazil, August 31, 2022, p. 18. (国家税务总局国际税务司国别(地区)投资税收指南课题组. 中国居民赴巴西投资税收指南, 2022年8月31日, 第18页).

Xue Wei. Tax Risk Analysis of BRICS Countries: Based on Tax Agreements and Tax Business Environment, “Finance and Accounting Monthly” 2021, Issue 19, pp. 154–160. (薛伟. 金砖国家的税收风险分析— —基于税收协定和税收营商环境, 《财会月刊》, 2021年第19期, 第154–160).