The Dynamics of Social Networks Among Muslim Students in Kraków: Experiences of Cultural Interaction and Integration

AGH University of Krakow, Poland

İnönü University, Turkey

Abstract: Migration profoundly shapes the social, cultural, and psychological experiences of individuals. As a distinct migrant group, Muslim students face unique challenges and opportunities in forming social networks in host societies. This study examined how the social relationships developed by Muslim students in Kraków influence their adaptation and sense of belonging. Adopting a phenomenological approach, data was collected through semi-structured in-depth interviews and analyzed thematically. The participants included 14 Muslim students (10 male, 4 female). Findings revealed two interrelated themes: Social Environment and Isolation, reflecting limited interaction with the host society and reliance on culturally-similar networks; and Personal Resilience and Integration Efforts, highlighting the students’ individual strategies to build belonging despite structural barriers. The study concludes that Muslim students experience partial integration, depending largely on familiar networks, while actively navigating social challenges. These insights point to the need for more inclusive practices to support integration in multicultural settings.

Keywords: migration, social networks among foreigners, social integration, Muslim students

Dynamika sieci społecznych wśród studentów muzułmańskich w Krakowie – między interakcją a integracją kulturową

Abstrakt: Migracja głęboko kształtuje doświadczenia społeczne, kulturowe i psychologiczne jednostek. Studenci muzułmańscy, jako odrębna grupa migrantów, stają w obliczu wyjątkowych wyzwań i możliwości w procesie tworzenia sieci społecznych w społeczeństwach przyjmujących. Niniejsze badanie analizuje, w jaki sposób relacje społeczne nawiązane przez studentów muzułmańskich w Krakowie wpływają na proces adaptacji oraz ich poczucie przynależności.

Przyjmując podejście fenomenologiczne, dane zebrano za pomocą częściowo ustrukturyzowanych wywiadów pogłębionych, które następnie poddano analizie tematycznej. W badaniu wzięło udział 14 studentów muzułmańskich (10 mężczyzn i 4 kobiety). Wyniki wskazują na dwie powiązane ze sobą kwestie: środowisko społeczne i izolację – odzwierciedlające ograniczoną interakcję z lokalnym społeczeństwem i poleganie na kulturowo podobnych sieciach – oraz wytrwałość i osobiste zaangażowanie w budowanie więzi, ukazujące indywidualne sposoby radzenia sobie z wyzwaniami społecznymi i poszukiwaniem własnego miejsca. Studenci z krajów muzułmańskich doświadczają częściowej integracji, w dużej mierze opartej na znanych im sieciach kontaktów, jednocześnie podejmując aktywne działania, by odnaleźć się w nowym środowisku. Wyniki te wskazują na potrzebę wprowadzania bardziej inkluzyjnych praktyk wspierających integrację w wielokulturowych przestrzeniach akademickich.

Słowa kluczowe: migracja, sieci społeczne migrantów, integracja społeczna, muzułmańscy studenci

Introduction

Although Poland has historically been perceived as ethnically and religiously homogeneous, recent migration patterns have significantly diversified the country’s demographic landscape (Andrejuk, 2018). This diversification includes the presence of Muslims, whose roots in the region date back to the 14th century, revealing an often-overlooked component of the country’s historical diversity. In addition to the Tatar communities who had lived within the country’s borders for centuries (Szajkowski, 1999), waves of Muslim migrants and refugees since the second half of the 20th century have contributed to the growing diversity of Poland’s Muslim population. Current estimates place the Muslim population in Poland between 25,000 and 40,000, accounting for approximately 0.1% of the total population (Pędziwiatr, 2015; 2020).

Although Muslims represent a small demographic minority, they have been central to various political and social debates in Poland (Ratajczak, Jędrzejczyk-Kuliniak, 2016; Goździak, Márton, 2018; Łaciak, Frealak, 2018; Troszyński, El-Ghamari, 2022). These debates often portray Muslim migration through the lens of security threats and social disruption (Bartoszewicz, Eibl, Ghamari, 2022; Kabata, Jacobs, 2023). According to Andrejuk (2019a), Poland’s policy toward Muslim immigrants operates at two levels: admission and cultural recognition, each shaped by both discursive narratives (e.g., media, political statements) and legal regulations (e.g., migration and integration laws). Consequently, research on Muslims in Poland has intensified, especially in connection with rising Islamophobia across Europe (Górak-Sosnowska, 2016; Narkowicz, 2018).

The existing body of literature has predominantly focused on historical narratives, religious beliefs, and public perceptions (Włoch, 2009; Narkowicz, Pędziwiatr, 2016; Bobako, 2018; Stojkow, 2018; Groyecka et al., 2019). However, more recent work has expanded to include topics such as the experiences of Muslim women (Górak-Sosnowska, 2015; Stojkow, 2019; Krotofil et al., 2022), religious practices during the COVID-19 pandemic (Kostecki, Piwko, 2021), and orientalist stereotypes in legal discourse (Górska, Juzaszek, 2023). Other studies have addressed refugee migration, religious discrimination in schools, and the role of the Catholic Church in shaping social attitudes toward Islam (Anczyk, Grzymała-Moszczyńska, 2016; Pędziwiatr, 2018; Cieślińska, Dziekońska, 2019; Sealy, 2021). In parallel, research in Western contexts has highlighted the complex interplay between religion, ethnicity, and structural constraints in shaping the social networks of young Muslims. For example, Ameera Karimshah, Melinda Chiment, and Zlatko Skrbisa (2014) emphasized the role of the mosque in Brisbane as both a spiritual and social space that fosters belonging and identity among diasporic Muslim youth. These networks often reflect homophily formed along shared sociodemographic lines which can result in social insularity and limited civic engagement. Similar patterns have been observed in the UK and the USA, where religion has emerged as a more salient marker of identity than ethnicity for young migrants (Naber, 2005; Modood, 2007). This trend aligns with findings that young Muslims in the West often adopt a universalist religious identity, enabling belonging beyond ethnic or national affiliations (Dialmy, 2007; Jacobson, 2010).

Since Poland’s accession to the European Union in 2004, the country has witnessed increasing migration flows, driven by factors such as labor demand and flexible immigration policies (Łaciak, Frealak, 2018). In recent years, Poland has also become a growing hub for international students. In the 2022/2023 academic year, the number of foreign students surpassed 100,000 for the first time, with 105,404 students from 179 countries, accounting for 8.61% of the total student population (Polish Science, 2024). While the majority hail from Ukraine, Belarus, and Türkiye, a notable portion come from Muslim-majority countries such as Uzbekistan, Nigeria, Azerbaijan, and Saudi Arabia (Buczek, 2022).

This study aims to explore the cultural and social interactions, adaptation processes, and social networks of Muslim students living in Poland, with a particular focus on how these elements shape their sense of belonging and integration.

Methods

Research design

In this qualitative study, a case study design was utilized (Fossey et al., 2002). The case study design, often associated with the phenomenological approach, focuses on phenomena that require a deep and comprehensive understanding, which may not be immediately evident or fully grasped through surface-level analysis (Patton, 2002). Phenomenology, as a qualitative research method, allows individuals to articulate their perceptions, emotions, viewpoints, and experiences regarding a particular phenomenon or concept. Its primary aim is to gain profound insight into how individuals personally experience and interpret the phenomenon under investigation (Rose, Beeby, Parker, 1995). Phenomenology specifically examines phenomena that we are aware of but may not completely understand at a deeper level. These phenomena often manifest as events, experiences, perceptions, or situations encountered in daily life familiar yet inadequately comprehended. Therefore, phenomenology provides an effective research framework for exploring these everyday concepts that we encounter regularly but struggle to fully comprehend or make sense of (Yıldırım, Şimşek, 2016). This approach enables the researcher to capture the richness and complexity of lived experiences, offering valuable insights into phenomena that might otherwise be overlooked in more conventional methods.

Study group

The study group was selected through purposive sampling, specifically utilizing the criterion sampling method (Patton, 2002). To be eligible for participation, individuals must be university students who self-identify as Muslims, reside in Kraków, and have a duration of stay longer than three months. Additionally, participants should be willing to voluntarily take part in the research and must be 18 years of age or older. All participants were thoroughly informed about the study’s objectives, scope, and methodology. To ensure confidentiality, each participant was assigned an anonymized code – such as P1, P2, or P3 – to protect their identity. The study group consists of 10 male and 4 female participants, which is due to the fact that there are more male students arriving from Muslim countries than female students. The majority of the participants are aged ranging from 22 to 35. Most participants are single, and their duration of stay ranges from 9 months to 7 years, though the majority have stayed between 1 and 2 years. The participants come from various countries, including Indonesia, Pakistan, Iran, Jordan, Morocco, Egypt, and Türkiye. The students were affiliated with various academic institutions, including the AGH University of Science and Technology (AGH), the Jagiellonian University (UJ), the Kraków University of Economics (UEK), the School of Business (WSB), the Andrzej Frycz Modrzewski University (UAFM), and the Polish Academy of Sciences (PAN). Some respondents were undergraduate or graduate students, while others were preparing a doctoral dissertation. Although specific sectarian affiliations were not directly addressed during the interviews, it can be inferred from the participants’ countries of origin that they most likely adhere to Sunni Islam. Exceptions include students from Iran, where Shia Islam is the dominant denomination.

Data collection tools and analysis

The research data was collected in two stages. In the first stage, the semi-structured interview form was utilized (Creswell, Creswell, 2018). The participants were engaged in comprehensive face-to-face interviews, which were conducted between January and March 2024. Thematic analysis in this study followed the six-phase approach proposed by Virginia Braun and Victoria Clarke (2006). These phases include: (1) getting familiarized with the data; (2) generating initial codes; (3) searching for themes; (4) reviewing themes; (5) defining and naming themes; and (6) producing the final report. This structured process ensured a rigorous interpretation of the participants’ narratives, further strengthened by independent analyses conducted by two researchers to enhance reliability and credibility.

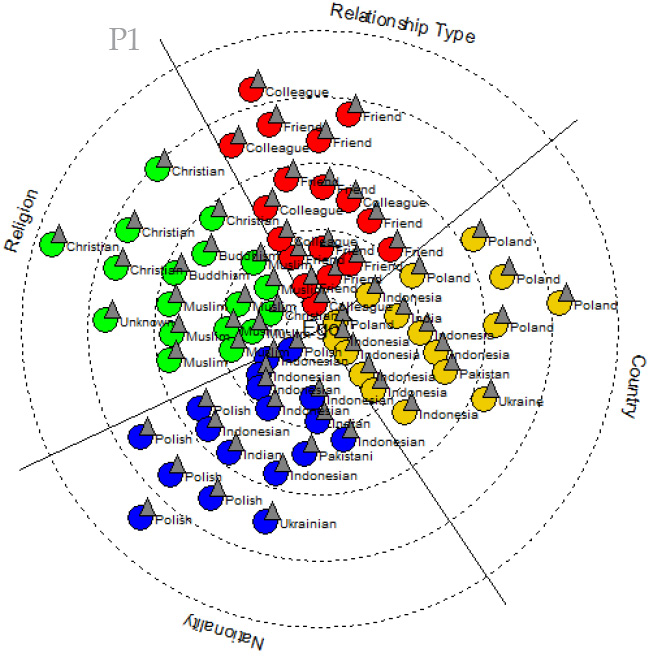

In the second phase of data collection, the participants were asked to complete a form prepared by the researchers to map their current social networks. The form consisted of four rows and five columns, with the columns labeled: Name (initials), Relationship Type, Country, Nationality, and Religion. These types of data allowed for a multidimensional understanding of each participant’s social network. Egocentric network data obtained through this form was subsequently analyzed using the EgoNet.QF software (version 3.00). The participants were presented with a diagram consisting of four concentric circles, with the center labeled “ego” to represent the self. They were instructed to enter the initials of individuals who were personally significant to them, placing these within the circles based on perceived relational closeness. The innermost circle indicated the closest relationships, followed by moderately close relationships, and, finally, more distant yet socially relevant connections (Straus, Pfeffer, Hollstein, n.d.; Djomba, Zaletel-Kragelj, 2016; Hollstein, Töpfer, Pfeffer, 2020). Within the software interface, sectors such as religion and relationship type were created, and participants organized individuals accordingly. Gender was visually indicated using shapes: a triangle  for males and a square for females

for males and a square for females  . Each network graph was color-coded for clarity. EgoNet.QF facilitated both the visualization of these networks through graphical maps and the extraction of data for descriptive statistical analysis. In this study, the software served as both a data collection instrument and the primary analytical tool for examining the participants’ social network structures.

. Each network graph was color-coded for clarity. EgoNet.QF facilitated both the visualization of these networks through graphical maps and the extraction of data for descriptive statistical analysis. In this study, the software served as both a data collection instrument and the primary analytical tool for examining the participants’ social network structures.

Social environment and isolation

The participants generally came to Poland motivated by academic opportunities, economic reasons, or its proximity to other European countries. For some, Poland was less of a planned destination and more of an alternative option. Economic factors and low living costs played a significant role in this decision, while academic goals remained the primary source of motivation.

“My main motivation for coming to Kraków was to develop myself academically abroad” (P13). “I wanted to go to countries like Norway, Sweden, or Germany, but I couldn’t find a position there” (P6). “[…] a friend in Malaysia connected me with my current advisor, which ultimately led me to Kraków” (P2). “I chose Poland because it is cheap, it is in the European Union, and it is a central European country” (P11). “I was looking for a scholarship for my PhD studies. I interacted with professors from many countries, but Poland was the only option available” (P10).

Furthermore, they may not possess the requisite knowledge to formulate expectations of their future life in Poland. Regardless of the length of stay, Muslim students’ social networks tend to involve students from their own country and fellow Muslims. The students who participated in the interview emphasized that: “Most of my friends are from Indonesia. I couldn’t make many friendships with local people” (P1), or that: “Foreigners hang out with foreigners because we have common problems” (P13). “Before coming here, I was a very social person in Pakistan and thought I would have many friends, which turned out to be true, but mostly within my own cultural circle” (P8).

Source: own elaboration using EgoNet.QF.

As seen in Figure 1, most of P1’s close friends are fellow Indonesians and Muslims, while P5’s close friends come primarily from Pakistan and India, which means that they reproduce friendship patterns from their regions of origin. Although these social networks provided a sense of solidarity among migrants, they also limited opportunities for broader cultural integration. This restrictive effect may be attributed to the relatively closed social structures of the local community. A close examination of the participants’ statements reveals that a number of factors influence the social integration processes of migrants in a new society. The majority of the participants have established their social circles primarily with individuals from their own cultural backgrounds, while a minority have also cultivated relationships with local individuals. The integration process of migrants into a new society is often accompanied by challenges, including language barriers, cultural differences, religious needs, and a sense of identity. However, an important factor in overcoming these barriers is the support that migrants receive from other migrant communities and their own cultural affiliations. The capacity to communicate in a common language, such as English, has been shown to facilitate interactions with the local population and thereby ease the integration process.

A close examination of the participants’ statements reveals that migrants predominantly form social relationships with individuals from their own cultural background. This phenomenon is exemplified by the following statement: “My social network here is mostly made up of people from my own culture. I spend time with foreign friends, for example, playing football with people we don’t know, organized through social media. My interactions with the local people are quite limited, as it is hard to form deeper connections due to language barriers and cultural differences. […] Generally, I spend time with people from the Arab world or similar cultures” (P6). The following statements are illustrative of the experiences of individuals in establishing social networks in Kraków: “I came to Poland for the first time as an Erasmus student, and I struggled to interact with locals, especially due to the language barrier. Before coming here, I didn’t know anyone, but now I spend my weekends participating in social activities and hanging out with my friends in the dorm. I usually choose my friends from my academic field, and I don’t enjoy discussing religion much because sometimes we get upset when we have different opinions. I regularly go to the Islamic Center, and my relationships there are more formal. My interactions with locals are limited because they usually speak Polish, and I always feel left out, which bothers me” (P9). “I usually spend time with foreign friends from Pakistan, India, and other countries. We go out together and organize dinners. My interactions with Polish people are limited to school, and we do not engage in other activities together. Due to the language barrier, we struggle to form strong friendships, as most Poles are hesitant to speak in English. I had difficulty adapting to the local culture, particularly with older people, as I had two negative experiences, such as a woman pushing me… These incidents were upsetting. If I had known the local language, I would have felt much more comfortable. Furthermore, I was unable to build strong relationships with most of my Polish friends because they tend to be wary of foreigners” (P10).

While some respondents indicated that their social interactions with the local community were satisfactory, such remarks were relatively infrequent.

It is noteworthy that several interviewees point to cultural differences regarding the way in which social networks are used, which manifests in social life and in cultural expectations. As one person articulated: “[…] my spouse and I are social people […] But friendships here are different. In Türkiye, you meet people weekly or daily, but here, you meet maybe once every 3–4 months or once a year. If you live in a dormitory, your social environment is better, but if you live at home and you’re married, there aren’t many people in your social environment. When you meet someone here, it’s very planned and organized. If I say, ‘I’ll meet someone next week,’ people don’t really adapt to that. It’s like, ‘This week doesn’t work, let’s meet next week or next month, we’re not available,’ and so on. Generally, most of our friends are married, so I see them often at home, sometimes we go for breakfasts or dinners” (P14).

The experiences of the participants have been shown to reveal a common theme of social integration struggles and the challenges of establishing meaningful connections in a foreign society. Language barriers emerge as a significant obstacle to forming friendships with locals, as many of the participants express frustration with the difficulty of communicating in Polish or English. This linguistic divide often results in the formation of social networks primarily composed of fellow international students or foreigners, creating a sense of community among people from similar backgrounds. While the participants initially encounter challenges in adapting to the local culture, their social circles evolve over time. The pursuit of linguistic enhancement is a common motivation among the participants, leading them to seek connections with individuals who speak their language or are in similar academic disciplines. However, as their language skills improve and their focus shifts toward professional networking, the participants begin to form a broader and more diverse set of connections. Nevertheless, challenges such as cultural misunderstandings, negative interactions with locals, and wariness toward foreigners persist, particularly in interactions with older generations or more conservative groups. Furthermore, some participants highlight the importance of formal spaces, such as religious centers, as an alternative for creating connections, but they still find these relationships to be somewhat more distant compared to those formed in informal social settings.

The participants also stated that they had encountered various prejudices related to their Muslim identity. Symbols such as headscarves or names have made these prejudices more visible.

“[…] I never thought before that a Christian country could be so religious. I thought that religious fanaticism was only in Muslims… When I say my name, Mehmet, their attitudes change immediately […]” (P13). “Some of my friends who wear headscarves told me about various problems they experienced outside” (P6). “[…] When people see my headscarf, they behave differently. They hesitate to interact” (P7).

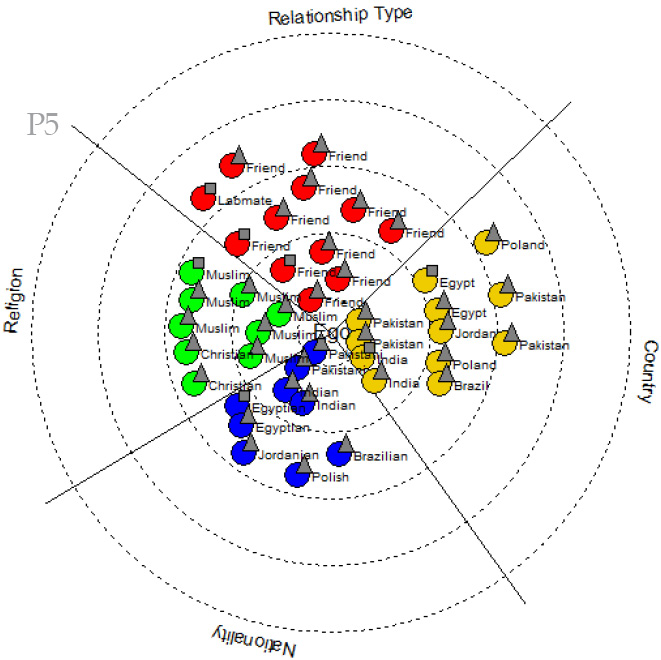

This can impact the social networks of Muslim-background female students (Figure 2).

Source: own elaboration using EgoNet.QF.

As seen in Figure 2, the majority of the female participant’s friends are Muslim students. Religious prejudices have made social acceptance more challenging and have led participants to feel excluded. Additionally, other challenges encountered in interactions with the local population have also affected the participants’ ability to establish connections with the community.

“An old woman pushed me while getting on the bus and shouted something in Polish…” (P10). “During my first month, someone wearing a hoodie deliberately walked into me on the sidewalk, pushing me hard. My phone fell and broke. It was a huge shock and a disappointing experience…” (P5).

These experiences suggest that cultural differences and misunderstandings can create barriers to the participants’ social integration, leading to the feeling of isolation. Visible markers of identity, such as the headscarf, seem to make these challenges more noticeable.

Personal resilience and integration efforts

Despite the challenges they faced, the students have made efforts to adapt to life in Poland through their individual actions. These efforts have allowed them to demonstrate resilience despite cultural differences.

“I started looking for hobbies like dancing or going to the theater to socialize more” (P12). “I enjoy meeting and spending time with local people, but the relationship doesn’t progress further. (P6) I joined a group for cultural exchange activities like hiking or playing billiards” (P3).

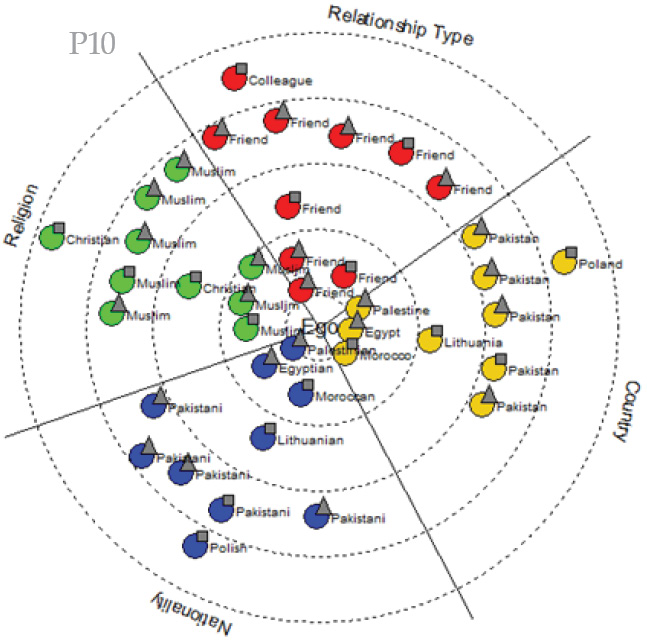

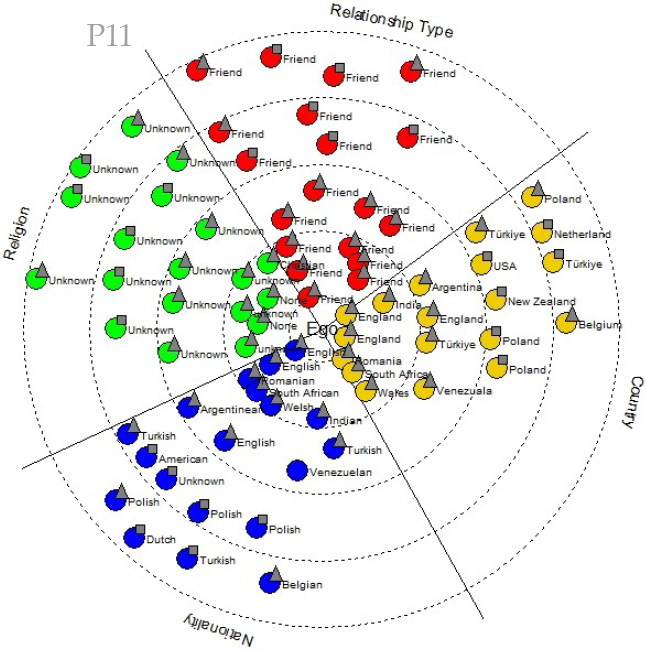

Source: own elaboration using EgoNet.QF.

As shown in Figure 3, Participant P11 has a more international social network. Individual efforts have played a key role in the integration process of the students. However, these efforts have not fully succeeded due to limited social acceptance. It is also expressed by some participants that the language acts as a barrier for Muslim students in establishing relationships with the local population.

In response to the question regarding their integration into the local culture, the respondents most frequently offer a negative response. For instance, one participant stated: “No, I don’t think I have integrated. There is a distance between people. Even with your colleagues, you can only have simple formal interactions; it doesn’t go further. I participated in various language exchange, dance activities, but my relationships with local people remained limited to the environment” (P6). Another one said that: “To be honest, no, I mostly socialize with people from my country and culture. Actually, I don’t know how to socialize with other people, especially with Polish people” (P2).

Discussion

This study examined the migration experiences of Muslim students in Kraków by exploring their reasons for selecting this destination, the cultural and social interactions they engaged in, and the strategies they employed for integration. In particular, it explored how the social relationships they established after their arrival shaped their adaptation processes and sense of belonging within the local context. According to the research findings, the participants chose Poland due to academic opportunities, economic reasons, and its strategic location within Europe. For many students, Poland is not their first choice but, rather, an option shaped by the existing circumstances. Previous research findings also support this. For students from non-European countries, Poland offers the opportunity to obtain a diploma recognized by the European Union (Kubiciel-Lodzińska, Ruszczak, 2016). Another study identified that the most significant motivations include gaining international experience, enhancing career prospects, improving language skills, and being in a different cultural nvironment (Bryła, 2018). Paweł Przyłęcki’s (2018) research concerning international medical students found that Poland’s affordability compared to other European countries, while the presence of friends or relatives studying there were key factors influencing the researched students’ choices. In another study, it was found that co-ethnic networks hold significant importance, particularly among Turkish migrants in Poland, whose mobility lacks institutional support from both the country of origin and the host state (Andrejuk, 2019b).

Another finding of the study highlights the complexity of social interactions between Muslim students and the local population due to closed social structures and language barriers. Some participants observed that the local people maintained a distant and cautious attitude. International student communities played a crucial role in overcoming these challenges. Previous studies had reported various adaptation difficulties among students in Poland (Przyłęcki, 2018; Safayi, Boulaghi, Maleki, 2023). An analysis of individual experiences suggests that many international students perceive disparities in their treatment within various social settings compared to local residents. They often feel that their cultural values are not fully understood or acknowledged, which leads to feelings of exclusion and emotional distress (Akhtar, Kröner-Herwig, 2015). These findings highlight the need for greater intercultural awareness and inclusive social environments to support the integration of international students. Strengthening local-international interactions could help reduce social distance and improve the students’ sense of belonging.

The perceptions of immigrants have been shaped within a negative framework due to media discourses and government policies. The media’s portrayal of immigrants as an economic burden appears to contribute to social exclusion. Many studies highlight that the initial perceptions of Muslims, in particular, are influenced by dominant narratives in the media, which often depict this religious group through a lens of cultural differences and social tension (Ratajczak, Jędrzejczyk-Kuliniak, 2016; Troszyński, El-Ghamari, 2022; Kabata, Jacobs, 2023). This also leads to the negative perception of students who are of Muslim origins (Przyłęcki, 2018; Safayi, Boulaghi, Maleki, 2023), limiting their interaction with the local people and culture as well as making their adaptation more difficult.

The students reported facing prejudices, particularly due to their Muslim identity. Religious symbols such as headscarves and names were identified as reinforcing these biases. Previous research (Przyłęcki, 2018; Stojkow, 2018; Safayi, Boulaghi, Maleki, 2023) suggests that names and headscarves, which directly represent Islam, negatively impact Muslim students’ social integration and restrict their interactions with the local culture. The intersectional perspective (Crenshaw, 1989) was applied to better understand the compounded forms of marginalization reported by several of the participants. For instance, female students who wear the hijab often experience overlapping challenges rooted in gender norms, religious visibility, and their immigrant status. These intersecting identities influence their interactions in the university setting, public space, and peer relations. As previous study had shown (Andrejuk, 2018), such experiences are not the result of a single social category, but of the simultaneous effect of multiple identities.

The study conducted by Asiye Safayi, Mahdi Boulaghi, and Amir M. Maleki (2023) shows that Muslim students are unable to establish sufficient relationships with the local people. A study conducted by Stojkow (2018) states that Muslim communities in social-media groups are generally segregated by gender and remain closed. This indicates that only specific types of individuals are accepted as members of these groups. These findings also support our research results.

Conclusion

This study provides an in-depth examination of the adaptation processes of Muslim student immigrants in Kraków and the impact of their social relationships with the local community on their sense of belonging. The findings indicate that Muslim students who migrate to Poland primarily choose the country for academic opportunities, economic reasons, and its strategic location within Europe. However, these choices are often shaped not by an ideal option, but by the existing circumstances and external factors. This suggests that the decision to stay in Poland is influenced not only by academic or economic motivations, but also by external challenges and constraints.

In terms of social relationships with the local community, our findings reveal that language barriers and the reserved attitude of the local population significantly hinder the students’ social integration. These obstacles make it difficult for the students to establish strong connections with the local community, often resulting in only superficial relationships. The students typically form stronger bonds within their own cultural communities and have limited depth in their interactions with the local population. This has led to a weakened sense of belonging and increased social isolation. Many of the students felt that their cultural differences and religious identities were not fully accepted by the local society, leading to feelings of exclusion and loneliness. Based on the findings, three distinct forms of cultural interaction among Muslim students in Kraków can be identified. First, community-based interaction occurs primarily within shared religious or national groups, offering emotional and social support. Second, institutional integration takes place within academic environments, where the students engage with university structures and activities. Third, some participants experience limited local engagement, often constrained by language barriers and the lack of sustained interaction with the host society.

Another key finding of the study is that Muslim students face discrimination due to their religious symbols and cultural markers, particularly headscarves and names. These symbols have made the students’ social integration more difficult and have limited their interactions with the local community. The students expressed that these identity markers further marginalized them and contributed to greater discrimination within the society.

This study demonstrates that the challenges faced by Muslim student immigrants in Kraków cannot be overcome solely through individual efforts. Although the students participate in various cultural activities to integrate socially, these efforts have often been insufficient to gain broader societal acceptance. The closed nature of the local community and limited forms of interaction have both prevented the development of a stronger sense of belonging among the students, leaving them in a more isolated social position. In this context, it is crucial to build stronger and more inclusive relationships between the local population and international students, reduce social distances, and embrace cultural diversity to improve the integration processes of Muslim students in Poland. These findings highlight the need for universities and policymakers to develop targeted support structures for international students. Institutions should consider implementing intercultural orientation programs, Polish language courses tailored for non-native speakers, and opportunities for structured social interaction between local and foreign students. Such initiatives may improve the quality of integration and foster a more inclusive academic environment.

However, it should also be noted that the number of interviews conducted in this research is limited, and this study represents only the initial stage of a broader investigation. Despite these limitations, the preliminary findings provide valuable insights that can guide further, more comprehensive research in the future.

Autorzy

* Maria Stojkow

* Ahmet Yasuntimur

Cytowanie

Maria Stojkow, Ahmet Yasuntimur (2025), The Dynamics of Social Networks Among Muslim Students in Kraków: Experiences of Cultural Interaction and Integration, „Przegląd Socjologii Jakościowej”, t. XXI, nr 3, s. 60–75, https://doi.org/10.18778/1733-8069.21.3.04

References

Akhtar Mubeen, Kröner-Herwig Birgit (2015), Acculturative Stress Among International Students in Context of Socio-Demographic Variables and Coping Styles, “Current Psychology”, vol. 34, pp. 803–815, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-015-9303-4

Anczyk Adam, Grzymała-Moszczyńska Joanna (2016), Religious discrimination discourse in the mono-cultural school: the case of Poland, “British Journal of Religious Education”, vol. 40(2), pp. 182–193, https://doi.org/10.1080/01416200.2016.1209457

Andrejuk Katarzyna (2018), Entrepreneurial strategies as a response to discrimination: Experience of Ukrainian women in Poland from the intersectional perspective, “Anthropological Notebooks”, vol. 24(2), pp. 25–40.

Andrejuk Katarzyna (2019a), Politicizing Muslim Immigration in Poland – Discursive and Regulatory Dimensions, [in:] Katarzyna Górak-Sosnowska, Marta Pachocka, Jan Misiuna (eds.), Muslim Minorities and the Refugee Crisis in Europe, Warsaw: SGH Publishing House, pp. 205–222.

Andrejuk Katarzyna (2019b), Strategizing Integration in the Labor Market. Turkish Immigrants in Poland and the New Dimensions of South-to-North Migration, “Polish Sociological Review”, vol. 2(206), pp. 157–176, https://doi.org/10.26412/psr206.03

Bartoszewicz Monika Gabriela, Eibl Otto, Ghamari Magdalena E. (2022), Securitising the future: Dystopian migration discourses in Poland and the Czech Republic, “Futures”, vol. 141, 102972, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2022.102972

Bobako Monika (2018), Semi-peripheral Islamophobias: the political diversity of anti-Muslim discourses in Poland, “Patterns of Prejudice”, vol. 52(5), pp. 448–460, https://doi.org/10.1080/0031322X.2018.1490112

Braun Virginia, Clarke Victoria (2006), Using thematic analysis in psychology, “Qualitative Research in Psychology”, vol. 3(2), pp. 77–101.

Bryła Paweł (2018), International student mobility and subsequent migration: the case of Poland, “Studies in Higher Education”, vol. 44(8), pp. 1386–1399, https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1440383

Buczek J. (2022), Raport: cudzoziemcy studenci i pracownicy polskich uczelni w roku akademickim 2021/2022, https://nawa.gov.pl/images/Badania-i-analizy/CUDZOZIEMCY_STUDENCI_PRACOWNICY_2021-22.pdf [accessed: 16.02.2025].

Cieślińska Barbara, Dziekońska Małgorzata (2019), The Ideal and the Real Dimensions of the European Migration Crisis. The Polish Perspective, “Social Sciences”, vol. 8(11), 314, https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8110314

Crenshaw Kimberle (1989), Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics, “University of Chicago Legal Forum”, vol. 1, pp. 139–167.

Creswell John W., Creswell J. David (2018), Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches, London: Sage Publications.

Dialmy Abdessamad (2007), Belonging and Institution in Islam, “Social Compass”, vol. 54(1), pp. 63–75, https://doi.org/10.1177/0037768607074153

Djomba Janet Klara, Zaletel-Kragelj Lijana (2016), A methodological approach to the analysis of egocentric social networks in public health research: A practical example, “Zdravstveno Varstvo”, vol. 55(4), pp. 256–263, https://doi.org/10.1515/sjph-2016-0035

Erudera (2024), Poland International Student Statistics 2024, https://erudera.com/statistics/poland/poland-international-student-statistics/ [accessed: 16.02.2025].

Fossey Ellie, Harvey Carol, McDermott Fiona, Davidson Larry (2002), Understanding and Evaluating Qualitative Research, “Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry”, vol. 36(6), pp. 717–732, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1614.2002.01100.x

Górak-Sosnowska Katarzyna (2015), Between Fitna and the Idyll: Internet Forums of Polish Female Converts to Islam, “Hawwa”, vol. 13(3), pp. 344–362, https://doi.org/10.1163/15692086-12341286

Górak-Sosnowska Katarzyna (2016), Islamophobia without Muslims? The Case of Poland, “Journal of Muslims in Europe”, vol. 5(2), pp. 190–204, https://doi.org/10.1163/22117954-12341326

Górska Ewa, Juzaszek Anna (2023), The “Other” in Court: Islam and Muslims in Polish Judicial Opinions Published Online, “International Journal for the Semiotics of Law”, vol. 36, pp. 1817–1842, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-023-10008-z

Goździak Elżbieta M., Márton Péter (2018), Where the wild things are: Fear of Islam and the anti-refugee rhetoric in Hungary and in Poland, “Central and Eastern European Migration Review”, vol. 7(2), pp. 125–151.

Groyecka Agata, Witkowska Marta, Wróbel Monika, Klamut Olga, Skrodzka Magdalena (2019), Challenge your stereotypes! Human Library and its impact on prejudice in Poland, “Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology”, vol. 29(4), pp. 311–322, https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2402

Hollstein Betina, Töpfer Tom, Pfeffer Jürgen (2020), Collecting egocentric network data with visual tools: A comparative study, “Network Science”, vol. 8(2), pp. 223–250, https://doi.org/10.1017/nws.2020.4

Jacobson Jessica (2010), Religion and ethnicity: Dual and alternative sources of identity among young British Pakistanis, “Ethnic and Racial Studies”, vol. 20(2), pp. 238–256, https://doi.org/10.1080/14782804.2022.2146072

Kabata Monika, Jacobs An (2022), The ‘migrant other’ as a security threat: the ‘migration crisis’ and the securitising move of the Polish ruling party in response to the EU relocation scheme, “Journal of Contemporary European Studies”, vol. 31(4), pp. 1223–1239, https://doi.org/10.1080/14782804.2022.2146072

Karimshah Ameera, Chiment Melinda, Skrbis Zlatko (2014), The Mosque and Social Networks: The Case of Muslim Youth in Brisbane, “Social Inclusion”, vol. 2(2), pp. 38–46, https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v2i2.165

Kostecki Wojciech, Piwko Aldona Maria (2021), Legislative Actions of the Republic of Poland Government and Religious Attitudes of Muslims in Poland during the COVID-19 Pandemic, “Religions”, vol. 12(5), 335, https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12050335

Krotofil Joanna, Górak-Sosnowska Katarzyna, Piela Anna, Abdallah-Krzepkowska Beata (2022), Being Muslim, Polish, and at home: converts to Islam in Poland, “Journal of Contemporary Religion”, vol. 37(3), pp. 475–493, https://doi.org/10.1080/13537903.2022.2101714

Kubiciel-Lodzińska Sabina, Ruszczak Bogdan (2016), The Determinants of Student Migration to Poland Based on the Opolskie Voivodeship Study, “International Migration”, vol. 54(5), pp. 162–174, https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12257

Łaciak Beata, Frealak Segeš (2018), The wages of fear. Attitudes towards refugees and migrants in Poland, https://www.isp.org.pl/en/publications/the-wages-of-fear-attitudes-towards-refugees-and-migrants-in-poland [accessed: 25.02.2025].

Modood Tariq (2007), Multiculturalism, Cambridge: Polity Press.

Naber Nadide (2005), Muslim First, Arab Second: A Strategic Politics of Race and Gender, “The Muslim World”, vol. 95(4), pp. 479–495, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1478-1913.2005.00107.x

Narkowicz Kasia (2018), ‘Refugees Not Welcome Here’: State, Church and Civil Society Responses to the Refugee Crisis in Poland, “International Journal of Political Culture and Society”, vol. 31, pp. 357–373, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10767-018-9287-9

Narkowicz Kasia, Pędziwiatr Konrad (2016), From unproblematic to contentious: mosques in Poland, “Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies”, vol. 43(3), pp. 441–457, https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2016.1194744

Patton Michael Quinn (2002), Qualitative research & evaluation methods, Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Pędziwiatr Konrad (2015), Muslims in Poland and Eastern Europe: Widening the European Discourse on Islam, [in:] A. van der Zee, A. Moors, T. Jahangir (eds.), Muslim minorities: Lived realities and contributions to Europe, Copenhagen: Centre for European Islamic Thought, University of Copenhagen, pp. 25–39.

Pędziwiatr Konrad (2018), The Catholic Church in Poland on Muslims and Islam, “Patterns of Prejudice”, vol. 52(5), pp. 461–478, https://doi.org/10.1080/0031322X.2018.1495376

Pędziwiatr Konrad (2020), Transformacje postaw wobec Arabów w społeczeństwie polskim z perspektywy członków społeczności arabskiej i muzułmańskiej, “Studia Humanistyczne AGH”, vol. 19(2), pp. 89–106.

Polish Science (2024), Raport „Studenci zagraniczni w Polsce 2023”, https://polishscience.pl/en/report-foreign-students-in-poland-2023/#:~:text=In%20the%202022%2F23%20academic,on%20data%20from%20the%20Central [accessed: 16.02.2025].

Przyłęcki Paweł (2018), International Students at the Medical University of Łódź: Adaptation Challenges and Culture Shock Experienced in a Foreign Country, “Central and Eastern European Migration Review”, vol. 7(2), pp. 209–232, https://doi.org/10.17467/ceemr.2018.13

Ratajczak Magdalena, Jędrzejczyk-Kuliniak Katarzyna (2016), Muslims and Refugees in the Media in Poland, “Global Media Journal”, vol. 6(1), https://globalmediajournal.de/index.php/gmj/article/view/51 [accessed: 15.02.2025].

Rose Pat, Beeby Jayne, Parker David (1995), Academic rigour in the lived experience of researchers using phenomenological methods in nursing in nursing, “Journal of Advanced Nursing”, vol. 21(6), pp. 1123–1129, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1995.21061123.x

Safayi Asiye, Boulaghi Mahdi, Maleki Amir M. (2023), Exploring the components of acculturative stress: A case study of İranian students in Poland, “Rocznik Lubuski”, vol. 49(1), pp. 87–101, https://doi.org/10.34768/rl.2023.v491.05

Sealy Thomas (2021), Islamophobia: With or without Islam?, “Religions”, vol. 12(6), 369, https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12060369

Stojkow Maria (2018), Polish Ummah? The Actions Taken by Muslim Migrants to Set up Their World in Poland, “Central and Eastern European Migration Review”, vol. 7(2), pp. 185–196, https://doi.org/10.17467/ceemr.2018.17

Stojkow Maria (2019), Muslim women in the mirror – the stigma of Muslim women in Poland, “Studia Humanistyczne AGH”, vol. 18(1), pp. 81–93, http://dx.doi.org/10.7494/human.2019.18.1.81

Straus Florian, Pfeffer Jürgen, Hollstein Betina (n.d.), EgoNet.QF: Software for data collecting, processing and analyzing ego-centric networks. User’s Manual for EgoNet.QF Version 2.12, http://www.pfeffer.at/egonet/EgoNet.QF%20Manual.pdf [accessed: 10.10.2024].

Szajkowski Bogdan (1999), An old muslim community of Poland: The Tatars, “ISIM Newsletter”, vol. 4(1), 27.

Troszyński Marek, El-Ghamari Magdalena (2022), A Great Divide: Polish media discourse on migration, 2015–2018, “Humanities and Social Sciences Communications”, vol. 9, 27, https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-01027-x

Włoch Renata (2009), Islam in Poland: Between ethnicity and universal umma, “International Journal of Sociology”, vol. 39(3), pp. 58–67, https://doi.org/10.2753/IJS0020-7659390303

Yıldırım Ali, Şimşek Hasan (2016), Sosyal bilimlerde nitel araştırma yöntemleri, Ankara: Seçkin Yayıncılık.