https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7692-5008

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7692-5008University of Silesia in Katowice, Poland https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7692-5008

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7692-5008

Abstract:

In 2020–2021, along with the growing interest in NFT art, some structures of the traditional art world were reproduced in the virtual space. They might be called CryptoArt world. This study investigates the state of the CryptoArt world in that period compared to the conventional art world. The aim is to classify CryptoArt world entities, specify their roles, characterize their internal and external relationships, and, finally, to indicate that the classic perspective of the production of culture is suitable for analyzing contemporary phenomena in art, such as NFT creativity. The analysis is based on the primary and secondary sources. These results show that the traditional art world was reproduced in the CryptoArt world in five areas: institutionalization, the acquisition of the privilege to legitimate art, hierarchization and polarization, centralization, and the emergence of ideological conflict. The results fill the gap in the NFT art qualitative analyses and expand the conclusions of previous papers on that subject.

Keywords:

NFT, art world, CryptoArt world, the sociology of art, the production of culture perspective

Abstrakt:

W latach 2020–2021 doszło do wzrostu zainteresowania sztuką NFT i jednocześnie do reprodukcji niektórych struktur klasycznego świata sztuki w przestrzeni wirtualnej. Tę nowo powstałą rzeczywistość można określić mianem świata kryptosztuki, który porównano w artykule z klasycznym światem sztuki. Celem opracowania była klasyfikacja podmiotów świata kryptosztuki, określenie ich ról, scharakteryzowanie relacji wewnętrznych i zewnętrznych, wreszcie wskazanie, że klasyczna perspektywa produkcji kulturowej jest adekwatna do analizy współczesnych zjawisk artystycznych, takich jak twórczość NFT. Badanie oparte było na analizie źródeł pierwotnych i wtórnych. Wyniki wskazują, że klasyczny świat sztuki został odtworzony w świecie kryptosztuki w pięciu obszarach: instytucjonalizacji, legitymizacji, hierarchizacji i polaryzacji, centralizacji, konfliktu ideologicznego. Wyniki wypełniają lukę w jakościowych analizach sztuki NFT i poszerzają wnioski z poprzednich prac na jej temat.

Słowa kluczowe:

NFT, świat sztuki, świat kryptosztuki, socjologia sztuki, perspektywa produkcji kulturowej

In early 2021, the global community was drawn to a project of online blockchain trading in artworks offered by their creators, signed with a unique non-fungible token (NFT), sold for cryptocurrencies. On February 25, 2021, The First 5000 Days (2021) by Mike Winkelmann, known as Beeple, was sold during an online auction at Christie’s. This event became a turning point for CryptoArt. For the first time in history, the solo NFT work was sold by a traditional auction house and hit an unexpected price of 69.3 million USD, which has contributed to a massive interest in NFT technology. Two million people followed the auction’s ending on Christie’s website. A month after the auction, Google Search Volume for the NFT entry reached the highest possible level of 100; in January, it was, on average, 2.5 (Google Trends, n.d.). In March 2021, over 509,000 NFT works were sold with a total value of over 85 million USD (Christie’s, 2021). It began the NFT art boom that lasted till the end of 2021 (Cascone, 2021).

From the sociological perspective, not only the increased attention paid to the NFT art segment is riveting, but also the processes taking place between the entities co-creating the environment around NFT art. The original purpose of using the NFT technology, initiated by artists in 2014, was to regulate the Intellectual Property rights to electronic works and, above all, to free creators from the need to cooperate with intermediaries: art dealers, galleries, auction houses (Dash, 2021). It was about the decentralization of artistic spheres. The trade in digital artworks was to take place through dedicated Internet portals available to the interested parties – artists and buyers. With time, entities that complimented the artist – work – buyer continuum emerged and evolved into a kind of art world and reproduced some features of established art worlds (Almeda, Hartmann, 2023; Colavizza, 2023). In connection to Howard S. Becker’s concept of art worlds (Becker, 2008), this new formation might be called the CryptoArt world and analyzed in terms of the production of culture approach, including theories of Howard S. Becker (1976; 2008) and Pierre Bourdieu (1996; 2015). The goal is to conduct an analysis of the state of the CryptoArt world in 2020–2021 (to classify its entities; to specify their roles in comparison with the traditional art world; to characterize its internal and external relationships) and to indicate that the classic perspective of the production of culture is suitable for analyzing contemporary phenomena in art such as NFT art. The paper fills the gap in the NFT analyses as this new phenomenon calls for a sociological exploration.

The idea of CryptoArt was presented in 2014. At that time, the first purchase of a digital artwork was assigned a non-fungible, unique, anti-counterfeiting sequence of identification marks called NFT (non-fungible token), deposited simultaneously in the memory of numerous computers connected to the network (the so-called blockchain). In detail, the goal of the creators of the cryptocurrency-based system was, first, to give artists control over the copyright for their works made available online; second, to enable them to profit from the decentralized marketing of digital graphics (without intermediaries); third, to combine new technologies with the area of artistic creation (Colavizza, 2003: 1–2; Dash, 2021). From the moment of implementation, sharing, selling, and reselling, CryptoArt takes place through dedicated platforms that tokenize individual works using specific digital certificates (NFT). As a result, the creator obtains perpetual confirmation of the copyright to their original product, and the buyer has the right to use it freely (i.e., display, duplicate, resell). The technology based on the decentralized register of non-removable and non-modifiable data stored on the blockchain enables the tracking of the fate of the tokenized work and related transactions (made in cryptocurrencies, mainly Ethereum). It also allows a commission to be charged on each sale, which provides artists (and/or sales platforms) with profits in the future.

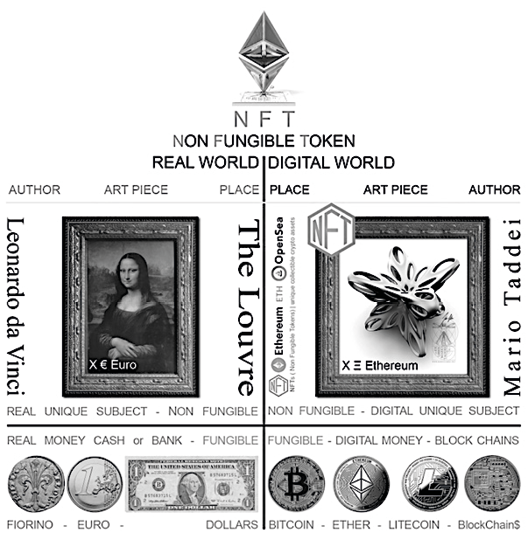

The activities of the entities of the traditional art world (more and less directly) focus on artworks. The same rule governs the CryptoArt world, although the works derived from it assume an intangible form. Nevertheless, NFT works should be attributed with features akin to traditional art products. CryptoArt, just like classical art, is manifested as unique, subject, non-fungible objects. Despite the existence of a copy or reproduction, there is only one real and digital original artwork; it remains the result of the work of a specific creator; it is deposited in a specific place; it is subject to valuation (Figure 1). The intangible NFT work is unique, stored on blockchains, and convertible into cryptocurrencies.

Figure 1. Real and Digital artworks compartment

Source: Taddei, 2021.

Not only digital art is subject to tokenization, but also other virtual objects – gaming, collectibles, metaverses, sports, and unity. The NFT market reached volume sales of 55,287,500 USD in 2020. CryptoArt had a 24% share in this market, although the proportion of transactions related to it was only 5%. It means a high price for individual works with a relatively small number of buyers, estimated at around 75,000 (Cabin VC, 2021). Even before the burst of global interest in CryptoArt in early 2021, its market value was systematically growing. In this segment, the value of transactions increased more than 20-fold in 2018–2020 (from approximately 619 thousand USD to almost 12 million USD) (Statista, 2021). In April 2021, NFT art’s total sales reached 78 million USD, peaked at 881 million USD in September, and systematically declined to 138.5 million USD in December. For the full year 2021, sales volume totaled about 3.1 billion USD. In 2022, it reached only approximately 748 million USD (Statista, 2023). This paper focuses on the phenomena in the CryptoArt world during its most remarkable growth in 2020–2021.

The issue of NFT art is relatively new. The research devoted to it is still not extensive (Nadini et al., 2021), the number of publications is limited, there is no established theory to build research on, and most works are exploratory (Mitu, Bota, 2023: 41–43). At the same time, their authors represent various fields of science. There are studies devoted to different aspects of NFT art, for example its relationship with cryptocurrencies (Boido, Alioano, 2023), new ways of financing artists (van Haaften-Schick, Whitaker, 2021), analogies between the methods used in the NFT sales platforms and other such digital platforms (Mitu, Bota, 2023), copyrights (Evans, 2019), but also criticism of the phenomenon of the artistic commercialization and monetization of art in the context of tokenized creativity (Grba, 2023), the existence of racial and gender prejudices on the NFT market (Zhong, Hamilton, 2023), or the enormous ecological costs of developing technology based on NFTs (Almeda, Hartmann, 2023). Some papers are based on the analysis of individual sales platforms (Vasan, Janosov, Barbasi, 2022), while others refer to interviews with CryptoArt word actors (Almeda, Hartmann, 2023). Consequently, knowledge about NFT art remains scattered.

Many NFT art analyses present curious conclusions, although they often omit or marginalize threads from sociology or the sociology of art. Shm Garanganao Almeda and Bjoern Hartmann (2023) partly reference the sociological theory in the paper titled “NFT Art World: The Influence of Decentralized Systems on the Development of Novel Online Creative Communities and Cooperative Practices.” The authors describe NFT platforms as “[…] sites that facilitate the cooperative activities of artists and artifact support networks” (Almeda, Hartmann, 2023: 253). Based on the analysis of the interviews with 16 online creators, they identify the practices of artists operating on various NFT platforms. Their observations regarding the NFT Art world are significant from this paper’s perspective. The authors point out that NFT technology provided new opportunities for access to art and its financing (e.g., global reach). On the other hand, operating costs (the use of enormous energy resources) and complicated technologies (the necessity to use cryptocurrencies) limit the CryptoArt world openness, which may “amplify advantages for already privileged individuals” (Almeda, Hartmann, 2023: 267). The researchers note that the NFT art world duplicates the barriers of the traditional art market (Almeda, Hartmann, 2023: 266–267). Giovanni Colavizza draws attention to the same problem, pointing to the erroneous belief that NFT art opens the market directly to sellers-buyers by marginalizing the role of intermediaries in the art trade – dealers, galleries, curators, experts (Colavizza, 2023: 1–2, 9). According to his research, the traditional art market and the NFT market do not differ in concentration or reference connections. As Colayza concludes, “The traditional art market is notoriously opaque and hard to access, with steep winner-take-all mechanics making it hard for most artists and collectors to benefit from it. Is the NFT art market any different? The answer is no” (Colvazia, 2023: 9). Similarities between the conventional art spheres and the NFT spheres are also noticed by Kishore Vasan, Milan Janosov, and Albert Laslo Barbasi, who examine the relationships between artists and collectors on the Foundation sales platform, which also resemble the relationships known from the traditional world of art (Vasan, Janosov, Barbasi, 2022).

The above observations arouse a deeper analysis of the NFT art world, showing how the CryproArt world and its areas responsible for producing, distributing, and receiving artistic pieces function in more detail. This study will expand the conclusions of previous papers, especially the research on NFT art worlds proposed by Almeda and Hartmann, which analyzes the impact of NFT art sales platforms on the development of creative communities rather than directly examining the CryptoArt world.

This article demonstrates that the classic theories of cultural production, which encompass various approaches to the social influence on the production, distribution, and reception of artworks, are adequate for analyzing contemporary artistic phenomena, including those materializing on the Internet. One of the basic assumptions of the production perspective is the claim that an artist’s work becomes recognized as art not solely due to their talent but through the efforts of individuals and institutions involved in its production, distribution, and reception (Peterson, 1994: 10). Researchers, despite some theoretical discrepancies, are unanimous that artistic circles function as a separate system (field, world, sphere, network) of interrelated elements (among others: artists, art academies, art dealers, galleries, museums, critics, art historians, art collectors, and art fairs). They remain in various types of relationships (e.g., cooperation, dependency, conflict) and are linked by a common interest (art) and a network of performed roles (not necessarily with similar goals). The art world adopts a specific structure driven by the nature of contacts and ties between the entities that create it. Some agents and agendas have the power of artistic confirmation, legitimization, exclusion, or contestation (White, White, 1965; DiMaggio, 1986; Bourdieu, 1996; Heinich, 2004; Baumann, 2007; Becker, 2008; Thorton, 2008; Alexander, Brewer, 2021).

The production of culture perspective has its sources in the philosophical works of Richard Dickie, who introduced the concept of qualifying institutions – historically variable, more or less formal social structures that have the power to objectify art (Dickie, 1974). In sociology and art history, Harrison C. White and Cynthia A. White were among the first to deal with similar issues, pointing to the crucial role of art dealers and art critics in the legitimization of French impressionism (White, White, 1965). Currently, the production of cultural approach is based mainly on two concepts, often treated complementarily (Baumann, 2007) – the world of art by Howard S. Becker (1976; 2008) and the field of art by Pierre Bourdieu (1996; 2015).

For Becker, interactions between entities of the art world are crucial, as artistic creativity results from the collective actions of agents. The art world is “The network of people whose cooperative activity, […] produces the kind of art works that art world is noted for” (Becker, 2008: xix). Artistic creativity results from the collective actions of agents undertaking core activities (closely related to the production, distribution, and perception of art) and support activities (base for core activities such as artistic tools producers). The art world is ruled by conventions (Becker, 2008: 253).

Pierre Bourdieu assumes that the field of art is a fragment of a system of many related fields within the field of power. A field is a system of objective relations (alliances, conflicts, competition, cooperation) between the positions occupied by agents and agendas with similar characteristics and aspirations. The field of art brings together artists as well as other individuals and institutions related to art education, exhibition, circulation, criticism, or collection. It is governed by internal (modifiable) rules. At the same time, it functions in connection with other areas of social life external to the field of art but remains in a closer or further relationship with it. Relations within a field are not constant, and there is a permanent game between social actors to maintain or take over a dominant position (Bourdieu, 2015).

Despite the differences between Becker’s interactional concept and Bourdieu’s relational approach, their theories provide a foundation for analyzing processes within the art environment. These are, among others:

The practices in the artistic environment are usually divided into three areas: production (e.g., creation and education: artists, schools, studios); distribution (e.g., presentation and circulation of art involving museums, galleries, art dealers, auction houses, art fairs, art advisors); and reception (e.g., consumption and evaluation by buyers, collectors, and viewers; evaluation by critics, art historians, trade magazines, websites, non-professional art experts – bloggers, and commentators) (Bourdieu, 1996; Heinich, 2004; Becker, 2008). While these roles often overlap, they collectively contribute to the art world’s functioning broader than just the art market (Thorton, 2008).

This study of the CryptoArt world aims to understand its organization and functioning during its boom of 2020–2021. I examined the production, distribution, and reception areas within the CryptoArt world, characterize its entities, and analyzed their roles and relations compared to the established art environment. Later, I verified how its typical processes are reproduced in the NFT art world.

The research is exploratory in nature, utilizing a mixed study of primary and secondary sources on NFT art in 2020–2021. All the analyzed primary sources were published within this period, while secondary sources were issued at that time and onwards.

The research unfolded in three distinct phases. Initially, I performed a non-systematic analysis of Internet content to gather general information on the NFT art world. It led to the identification of primary entities within the field, including NFT artists, sale platforms, curators, collectors, sellers/buyers, influencers, as well as traditional auction houses. Additional entities included NFT art museums, galleries, bloggers, commentators, critics, observers, as well as established galleries and fairs.

In the second phase, I chose particular entities for further in-depth research, which were the most recognizable artists, collectors, and influencers based on rankings and lists available online, as well as the largest NFT platforms (and their curators) and classic auction houses by income, according to professional reports devoted to NFT art. At the same time, I set data sources. The websites of those entities served as the primary sources; however, it should be noted that the commercial nature of some of them may have influenced their content to a certain extent (selected information, promotional bias). Nevertheless, they serve as indispensable data sources for the case study presented here, as they provide specialist knowledge and cover a range of relevant issues. They are compared with other sources to ensure a comprehensive analysis. Secondary sources contained relevant statistics and scientific research results as well as rankings, lists, and professional reports mentioned below. The selection was based on their widespread availability.

In the third phase, I conducted a systematic sources analysis, categorizing data into key aspects: production, distribution, and reception. Simultaneously, I examined materials on less recognized entities within the NFT art world, such as art museums, virtual galleries, smaller sale platforms, conventional galleries, fairs, bloggers, commentators, critics, and observers. Given the diffuse nature of available data on this domain, I employed the snowball method to recognize and focus traditional galleries, NFT museum and gallery web content; blogs; and online press comments and critiques. Some of the latter materials were used as commentaries for the broader analysis.

This methodology addresses the scarcity of systematic data in the NFT art domain and simultaneously emphasizes methodological accuracy. It demonstrates the usefulness of qualitative data research for initial, exploratory analysis in the field of the sociology of art.

Table 1. Data sources

| Primary sources on NFT art | |

|---|---|

| Sale platforms websites | Async Art; AutoGly; Eden Gallery; Foundation; KnownOrigin; MakersPlace; Nifty Gateway; SuperRare |

| Traditional auction houses platforms websites | Christies; Phillip’s; Sotheby’s; China Guardian |

| Other | Blogs, blogs’ imprints, traditional galleries websites, NFT museums and galleries websites (Private Museum; Open Air Museum) |

| Secondary sources on NFT art | |

| Reports | NFT Industrial Development Report Q1 2021 (Cabin VC, 2021); Yearly NFT Report 2020 (Non-Fungible, 2021); Yearly NFT Report 2021 (NonFungible, 2022); Art Basel & UBS Report ‘The Art Market 2022’ (2023) |

| Statistics | staticta.com |

| Rankings and lists | 15 Most Expensive NFTs Sold (So Far) (Thapa, 2021); 5 Great crypto art collectors (Art Rights, 2021); The 10 Most Expensive NFT Artworks of 2021 (Cascone, 2021); The 20 Top-Selling NFT Artists to Collect Right Now (Santillana, 2021); Top 200 Collectors (ARTnews, 2021); 15 Biggest NFT Influencers of 2021 (Hamacher, Hayward, 2021)’ |

| Others | Scientific research results, online press materials, blogs |

Source: own work.

Artists drive the art world yet face barriers due to origin, age, gender, and recognition status. A study of the Internet contents from 2020–2021 shows that the founding idea of openness and diversity in the CryptoArt world was still present in the NFT art narrative of the period. This is exemplified by a statement from Eden Gallery as it entered the NFT market: “The beauty of crypto art is its democratization of the art scene. Technology has allowed various artists and digital creators to get their work out to the world and find new, global fans and buyers” (Eden Gallery, 2021). However, discussing the same period and based on interviews with NFT artists, Almeda and Hartmann (2023) pointed out that the CryptoArt world introduced many barriers, primarily due to its machinery. “The tie to cryptocurrencies in particular was perceived as a complicating or problematic drawback to some of our participants and might impede the growth and maturation of the ecosystem into a network of healthy and sustainable online creative communities” (Almeda, Hartmann, 2023: 266–267). The requirement for fluency in technology to create works and the need to possess cryptocurrency wallets to execute transactions made Crypto artists “[…] digitally native and tech-savvy; they also tend to be CryptoPatrons or early adopters of cryptocurrency” (SuperRare, 2021).

In late 2021, the Gotham Magazine presented the ranking of The 20 Top-Selling NFT Artists to Collect Right Now (Santillana, 2021). It may be a source of information about NFT artists of the time, although many of them did not disclose complete personal information, with three remaining anonymous. Based on available data, the group was predominantly male (with only one female artist), aged 25–40, and mainly from Europe and North America. In terms of origin and gender, it recalls the structure of the traditional art world, in which mostly the works of men from Western countries have been noticed for most of history (Foster et al., 2016). Few top-selling NFT artists had formal art school training, indicating that such education was optional for acceptance in the CryptoArt world, unlike in the established art world (Crane, 1992: 76). In 2020–2021, art schools at various levels did not offer education courses in NFT art, limiting themselves to teaching digital art. From the end of 2021, the global training portal Udemy.com has offered the opportunity to participate in the ‘Creating Digital Art & Minting NFTs For Beginners’ course. On the other hand, before starting their activity in NFT art, almost all mentioned artists had practiced traditional or digital art recognized by the community. It means that the most established artists were not a group of random creators, and experience is appreciated in the NFT field.

The fact that 0.5 million pieces of NFT artwork were sold in 2020 (Cabin VC, 2021), and this number increased in 2021, with a peak of 117.4 thousand in July – August 2021 (Statista, 2023), raises questions about other than top-selling crypto artists mentioned above. Presenting characteristics of the less-known NFT artists is difficult due to the fragmented information available. The entire number of creators in 2020–2021 is unknown, but there were 865 active sellers of art NFTs in 2020 and 84,182 in 2021 (43% active in primary sales, 86% active in both primary and secondary sales) (McAndrew, 2023: 42).

Based on the accessible materials, it is possible to classify the creators of CryptoArt in 2020–2021 into groups. The first one, already mentioned, includes leading artists – a relatively hermetic group composed of experienced artists (Beeple, Trevor Jones or Jose Delbo), less often ‘new discoveries’ (Fewocious), selling their works in the most prestigious spaces (exclusive sales platforms, in traditional auction houses), for a high price. The second group consists of many aspiring to be in the circle of the most established artists. Those artists enjoyed some recognition in the worlds of conventional art and/or CryptoArt, whose works appeared on prestigious selling platforms (sometimes traditional auctions) but did not reach prices as high as those of the artists from the first group. This group was likely slightly more diverse in sociodemographic terms than the community of the most renowned artists, but further research needs to be carried out on this issue. The authors of the analysis titled Quantifying NFT-driven networks in crypto art (Vasan, Janosov, Barbasi, 2022), which is based on data from the prestigious Foundation sales platform (more on it later), point out that during the NFT art boom, the presence of a large number of artists and their works on the market resulted in its saturation, which made it difficult breakthrough of new creators, as well as that the reputation of certain artists was established (Vasan, Janosov, Barbasi, 2022: 5–6). The researchers distinguish three groups of artists selling works on the Foundation platform – the bottom 20% of the lowest income, the middle 75%, and the top 5% of the highest income. Price fluctuations for works created by artists from the above groups are small. “[…] [H]igh performing artists continue to receive a higher number of bids for new art and repeatedly attract high prices for their new art, while low reputation artists have difficulty demanding higher prices” (Vasan, Janosov, Barbasi, 2022: 7). It indicates the stabilization of prices and the reputation of creators, and, consequently, the establishment of a hierarchy of artists in the CryptoArt world in 2020–2021. It can be assumed that similar phenomena occur not only on the Foundation platform, but more broadly. It is important to note that the possibility of the advancement of artists who achieve middle and low incomes will verify the actual openness of the crypto art world.

The third and least recognized group of NFT authors comprises minor creators. Their works, available outside prestigious sales platforms, were numerous, poorly recognized online, relatively inexpensive, and mainly anonymous. According to several creator’s bios, they likely lacked significant experience in the art world; for some, NFT creation may have been a hobby or a hope for profit rather than a regular artistic activity. The rising value of NFT art acted as an incentive. The average price for NFT art increased from 200 USD in 2020 to 1,462 USD in 2021 (McAndrew, 2023: 42). However, in April 2021, nearly 55% of NFT art pieces sold for less than 200 USD (Kinsella, 2021).

The NFT art is digital. Therefore, the Internet is a natural space for its distribution. The virtual platforms hold the primary role in this process, which are mostly “[…] crypto art marketplaces which connect artists with buyers” (Franceschet et al., 2001). In 2020–2021, dozens of sales platforms operated online, but only a few became successful. In 2020, SuperRare achieved the highest market volume (6,000,743 USD), with nearly half the market share in the number of works sold. Five other platforms – MakersPlace, Async Art, KnownOrigin, AvaStars, and AutoGly – occupied slightly over a quarter of the market. The remaining 25% was taken by smaller portals (Non-Fungible, 2021). This distribution remained essentially unchanged in 2021, with six major NFT CryptoArt platforms – SuperRare, MakersPlace, KnownOrigin, Async Art, Foundation, and Nifty Gateway – holding almost 80% of the market share (Non-Fungible, 2022). Thus, the market was stratified. Platforms, with few exceptions, charged handling fees and commissions for artwork sales while allowing authors to profit from each transaction involving their work. According to Leon Pawelzik and Ferdinand Thies’s qualitative analysis of the NFT art market, artists accepted these fees and applied to exclusive platforms to support their business interests (Pawelzik, Thies, 2022: 8–9).

In 2021–2021, a large group of platforms remained open to all artists, while some small ones and the four leading platforms in 2021 – SuperRare, KnownOrigin, Async Art, and Foundation – applied a policy of the verification artists and works. High entry barriers (limited invitations, recommendations, positive evaluations of proposed works) were discussed in the CryptoArt world. Attention was drawn to the necessity of barriers due to rapid market growth. The NFT community expert’s statement represents this approach: “Each week there are thousands of new artists entering the space and the community is rapidly growing. While many of us want to escape the ‘old world’ structures of the traditional art world and its elitist attitude, it has become clear that without some sort of structure the CryptoArt world will easily become the Wild West. Curated NFT marketplaces have almost become a necessity with the rise in artists, collectors and tokenized artworks. Without some sort of guidelines to spotlight art pieces, creators and art collections, the number of NFT artworks could easily spiral out of control which would lead to less exposure and value for the artists themselves” (NFTPlazas, 2021). As a result, the role of professional selectors, so-called platform curators, has emerged in the CryptoArt world. Although detailed data on NFT art curators for 2020–2021 is lacking, it is known that in 2021, the Foundation recruited some curators from its users, while SuperRare employed digital art experts as curators. The introduction of curators signaled the emergence of intermediaries in the CryptoArt world, moving away from the direct sale of NFT art. There was a narrative in 2020–2021 advocating for the restoration of the founding principle of directness, even echoed by the elitist platform SuperRare. SuperRare emphasized that the selection privilege should be spread among a broader group of users: “SuperRare is embarking on a path of progressive decentralization – shifting ownership and governance of the network to our community” (SuperRare, 2020). However, in 2021, SuperRare noted that it was “still in early access, onboarding only a small number of hand-picked artists” (SuperRare, 2021). Other leading platforms employing the selection principle held similar perspectives. According to Pawelzik and Thies, in 2021, NFT many artists were enthusiastic about sales platforms’ curatorship policy. In their opinion, curators’ acceptance increased the chance of recognition and profit in the NFT art world (Pawelzik, Thies, 2022: 8–9). Satisfaction with exclusive sales platform strategies may suggest that NFT artists were interested in maintaining the established status quo in the CryptoArt world. This resulted in segmenting the NFT distribution area into elitist and public sale platforms.

In 2020–2021, apart from the sales platforms, CryptoArt was displayed and sold online through virtual galleries, which could not tokenize artworks. The NFT art was also presented in virtual museums that did not provide selling options. Despite the distribution of CryptoArt online, the growing interest in the NFT works disseminated outside the network. In March 2021, New York’s first gallery presented CryptoArt works. However, Art Basel Report stresses that eventually, in 2021: “[…] only a handful of established galleries such as Pace, König, and Nagel Draxler have shown any interest or attempt at foregrounding or launching serious NFT collections” (McAndrew, 2023: 123). The Artsy Gallery Insights Report (Artsy, 2022) indicates that in 2021, less than 11% of galleries worldwide sold NFT artworks, with only 5% achieving total sales volumes exceeding 250,000 USD (Artsy, 2022). NFT art debuted at the art fair (prestigious Art Basel) in the autumn of 2021, catching visitors’ attention. Opening day sales exceeded 90,000 USD (Brown, 2021). This means that in 2021, interest in distributing NFT art beyond the virtual space emerged, but it remained a novelty, with limited profits compared to online sales. Commentators noted that the primary obstacle was the requirement to use cryptocurrencies (Brown, 2021).

The main rapprochement between CryptoArt and the real art world occurred with the involvement of traditional auction houses in distributing the NFT art. After Christie’s million-dollar online auction of Beepe in March 2021, other auction houses (e.g., Sotheby’s, Phillips) sold more NFT works via their platforms. As Almeda and Hartmann observed, auction houses’ interest in NFT art allowed artists to enter previously inaccessible cultural spaces traditionally associated with high culture (Almeda, Hartmann, 2023: 364). On the other hand, fine art places opened for new art and technology. Christie’s 2021 total sales of NFTs were 150 million USD, in Sotheby’s – 100 million USD. At the same time, auction houses aimed to disseminate knowledge about CryptoArt. Christie’s and Phillips launched dedicated websites for CryptoArt. In July 2021, Christie’s organized the Art+Tech Summit: NFTs and Beyond at its New York headquarters (Christie’s, 2021). The sales platforms (and their curators) and the convectional auction houses became significant players in the NFT art distribution system and crucial mediators between the traditional art and CryptoArt worlds. It is worth noting that in many cases, auction houses served as primary market venues, where artworks were acquired directly from artists (like in conventional galleries) rather than in the secondary market spaces, where artworks are resold. The latter phenomenon occurred on selling platforms.

The community of NFT art buyers has emerged at the intersection of different impetus. Tuba Yilmaz, Sofie Sagfossen, and Carlos Velasco (2023: 9) identify monetary, functional, emotional, and social motivations as essential to all NFT object consumers. According to NFT commentators, the CryptoArt buyers were also influenced by motivations akin to those prevalent in the traditional art world: participation in the artistic community, following collecting trends, and supporting artists (Thapa, 2021). Additionally, NFT art was perceived as a speculative asset with potential value appreciation and a “tempting newness” that piqued buyers’ curiosity (Clark, 2021; Valeonti et al., 2021).

The most recognizable acquisitors in 2020–2021 were NFT art collectors, who participated in the most significant sales. Due to the high percentage of NFT art sales on the secondary market (21% of all sales in 2020 and 42% in 2021 – see: McAndrew, 2023: 43) and high frequency in resales (average time between purchase and resale in NFT art was 33 days – see: McAndrew, 2023: 46), the other NFT art acquisitors should be called buyers (and re-sellers). Simultaneously, it is important to underscore that their decisions may be driven by a desire for rapid profit generation or even speculation, a phenomenon observed in both the whole NFT and cryptocurrency markets (Nadini et al., 2021), but less common in the conventional art world. Until the popularization of CryptoArt, after the Beepe auction, the number of NFT art buyers was estimated at around 75,000 (Cabin VC, 2021), and it increased many times by the end of 2021. NFT art buyers might be assigned into three groups: small-transaction buyers, medium-sized players, and large-transaction buyers (often collectors). While detailed data on small and medium-sized market participants is lacking, the Art Basel Report indicates that in 2021, digital art accounted for 11% of high-net-value (HNV) collectors’ expenditures, with an average spending of 324,000 USD on NFT art. Notably, younger collectors (Gen. Z and Millennials) surpassed older generations (Gen. X and Boomers) in spending, with Millennials averaging 410,000 USD. In the traditional art sector, Boomers and Millennials spent the most (McAndrew, 2023: 229–231).

In 2021, the “Art Rights” Internet magazine introduced profiles of influential NFT art collectors. Their collections consisted mainly of works of the most established artists, but they occasionally invested in less-known ones (Art Rights, 2021). Vasan, Janosov, and Barbasi’s (2022) Foundation platform research concluded that collectors focused on a small group of preferred artists and wanted to purchase them repeatedly. It resembles the collection patterns of the traditional art world, where collectors often specialize in just a few artists (Vasan, Janosov, Barbasi, 2022: 7). This observation might be extended to influential buyers in other prestigious platforms in 2021. The influential NFT art buyers group included in the Art Rights ranking was made up of males, mostly of Asian or Western origin. Most of them had experience in the IT market and were related to the IT industry and the cryptocurrency market, not necessarily to art collecting (Art Rights, 2021). Comparing the list of the ten most influential collectors of material contemporary art of 2021 (ARTnews, 2021) and the ranks of the primary buyers of NFT art showed that the latter community was homogeneous in terms of gender (male only) and income-generating profession (almost exclusively sectors connected with the Internet). Material art collectors included females (four in the top ten, although listed with their husbands) and representatives of various business sectors (ARTnews, 2021). The top ten collectors in the conventional art world came from Europe or the USA (apart from two). In contrast, NFT art collectors mainly come from Asia, which means breaking the monopoly of the West on the collector’s market. On the other hand, the NFT art buyers’ group was deeply rooted in the Internet and NFT environment, and might be considered digitally hermetic. Its members dominated prestigious NFT art sales in 2021, in which the most influential collectors of material contemporary art were not interested, as they had yet to purchase an NFT work by the end of 2021.

The audience of NFT artwork in 2020–2021 extended beyond buyers to encompass various community members within the CryptoArt world, including bloggers, commentators, more or less professional critics, and observers. They often congregated via dedicated websites (e.g., forums, sales platforms, or auction houses), with some communicating through private websites, mainly blogs. Their primary role involved assessing NFT artwork and commenting on CryptoArt-related events, with many members remaining anonymous or using nicknames, which made their characterization challenging. Based on the blog imprints, many NTF art community members did not have specialized education in art history or economics. Despite this, they leveraged their knowledge of the crypto world to become experts in the field, reflecting a common phenomenon in the era of online media where events foster the emergence of grassroots experts (Castells, 2012: 465). Conversely, in 2021, sales platforms had their group of experts consisting not only of curators but also specialists editing and substantively moderating their portals. For example, SuperRare provided free-of-charge, extensive, constantly updated online Editorials on, among others, art, market reports, new artists, and events.

In 2021, influencers played a significant role in the CryptoArt world. As commentators stressed, “NFTs existed before 2021, but this year they went mainstream […] influencers have an outsized impact on the NFT space. Equally as important as the artists and creators themselves are the celebrities, curators, marketplace owners, and tastemakers who promote NFT projects on YouTube, Instagram, Discord, and, of course, Twitter – their primary platform of choice” (Hamacher, Hayward, 2021). Five of the fifteen most potent NFT influencers of 2021 were involved in the CryptoArt world as buyers, commentators, or artists themselves, with follower counts ranging from 163.8 thousand (Gmoney – among others, an investor in Art Blocks project that generates original NFT art via an algorithm) to over 19 million (SnoopDogg – among others, NFT art collector) (Hamacher, Hayward, 2021). Influencers had no education or connection to the traditional arts, but their opinions on the NFT art and investment suggestions had an audience of thousands. A massive number of followers might have reflected and, at the same time, increased interest in NFT art in 2020–2021, making influencers inherent intermediaries in the CryptoArt world.

In 2020–2021, the CryptoArt world remained dynamic, but it has already taken a specific form, operating – like a traditional art world – as a network of cooperative links leading to the coordinated actions of the participants (Becker, 2008: 34–35). The nature of its agents and agencies and the area of their practices were shaped by technology – emergence and flourishing cryptocurrencies and tokenization. The Internet served as the natural environment for NFT art, with few practices occurring outside the network. The NFT art field functioned as digital and virtual, yet it interconnected with the traditional field of art production. In the conventional art world, an extensive division of labor is fundamental (Becker, 2008: 13), which also occurred in the CryptoArt world in 2020–2021. The leading positions included artists (production), sales platforms, curators, auction houses (distribution), and buyers/collectors (reception). Additionally, less significant actors and institutions associated with NFTs have emerged (virtual galleries and museums, non-professional members of the Internet community related to NFT art). Some actors were unique to the NFT reality (sales platforms, platform curators, NFT art buyers, and influencers), while others paralleled the traditional art world (virtual galleries, museums) or belonged directly to it (some artists, auction houses, art fairs). In Becker’s terminology, they performed core activities in the CryptoArt world. The support activities suppliers, such as energy providers and hardware and software manufacturers, created a digital environment in which NFT art existed.

NFT art researchers found that the CryptoArt world in 2020–2021 reminded the classical art world in establishing the reputation of participants, their market patterns, and the reproduction of inequality (Vasan, Janosov, Barbasi, 2022; Almeda, Hartmann, 2023; Colavizza, 2023). The results presented in the preceding sections indicate that these parallels occurred at more levels than they had initially recognized. First, there was institutionalization involving the regulation of practices around NFT art within newly established specialized agencies, some of which took on roles beyond mere intermediation between the creator and the recipient. Eventually, this created a bipolar structure of the field, comprising professional and amateur poles. The former adhered to rules similar to the traditional art world, where artists’ creativity faced constant pressure and evaluation (Bourdieu, 1996), and artistic conventions regulated mutual relations and roles (Becker, 2008: 29).

In a professional pole, distribution agents were crucial in deciding what to spread and how to value it (Becker, 2008: 360). It resulted in the second process analogical to the classical art world – the acquisition of the privilege of legitimate art that emerged in this pole, along with strengthening the role of elite sales platforms and their curators. Together with experts representing auction houses, they have become powerful gatekeepers in the NFT art field. This phenomenon is typical of the traditional art world, where, according to Becker, “Some people occupy institutional positions which allow them, de facto, to decide what will be acceptable” (Becker, 2008: 151). Additionally, social media influencers, irrelevant in the conventional art world, have become gatekeepers in the crypto art world, assuming the role of art advisor and art critic. At the same time, exclusive sales platforms and their curators, who catered to customers’ businesses, functioned like galleries and dealers in the traditional art world, integrating artists into the economy by transforming esthetic value into economic value (Becker, 2008: 257). From 2020 to 2021, the role of traditional art galleries in distributing NFT art was marginal.

The professional pole was an area of allocating enormous financial resources and a place for artists to gain a position. The emergence of a group of the most recognized, dominating entities in the field (artists, collectors, intermediaries) led to hierarchization and economic polarization, which is the third process analogous to the traditional art world. In the classical world of art, subtle differentiation usually favors the exchange of relations with already established artists (Bourdieu, 1996: 81), and this pattern was also reproduced in the NFT world.

Taking the dominant position by powerful gatekeepers in 2020–2021 led to the fourth process analogous to the conventional art world, namely the centralization of the CryptoArt world around the principal, prestigious players: platforms, collectors, and auction houses. It occurred contrary to the foundational idea of decentralization and, consequently, the ideals of full diversity and openness were not maintained. The demographic structure of the significant actors indicated the dominance of young, IT-savvy men (among artists – of Western origin; among collectors – of Asian and Western origins), guided by motivations similar to those in the traditional art world. Prestigious intermediaries (platforms, auction houses) operated in Western countries.

Bourdieu emphasizes that the field of art is a space of competitive struggles, with each side striving to impose boundaries consistent with its interests, including ideas (Bourdieu, 1996: 365). In 2020–2021, the fifth process analogous to the conventional art world emerged: an ideological conflict within the professional pole regarding the role of prestigious platforms and their curators. They occupied a strong, influential position in the CryptoArt world, holding the power to legitimate creativity and polarize the artistic spheres. They simultaneously declared intentions to embrace egalitarianism and openness for all artists, which eventually did not happen in that period. The platforms faced pressure between the concept of decentralization and openness and the demands from experts, artists, and buyers for calling gatekeepers to ensure the quality of presented art.

The millions of dollars in price differences between individual NFT pieces in 2021 indicate economic polarization within the art field, also resulting in the existence of its second pole, the amateur one. This pole comprised artists and buyers associated with numerous non-prestigious, low-income sales platforms. Decentralized and difficult to characterize, this area included creators and buyers who did not achieve high prestige. Their work remained niche, failed to attract significant investments or collector interest, and lacked expert attention, underscoring its minor importance. In this pole, there were no entities with real legitimizing power. Therefore, the principle of direct contact between the creator and the buyer, which guided the beginnings of the NFT art market, has been maintained. The amateur field remained separate from the professional one. Like in the conventional art world, as Diane Crane emphasizes, works distributed by marginal organizations are infrequently assessed by recognized gatekeepers who provide access to prestigious institutions (Crane, 1992: 70).

Concerning the classical field of art, Bourdieu emphasizes that it remains in a relationship with external forces from other fields. Until this relationship becomes subordinate, activity in the artistic field is more or less limited by exogenously imposed norms and requirements. However, the potential in the field strengthens over time, and the field increasingly operates according to its laws and logic (Bourdieu, 2015: 257). The professional pole of the NFT art field had become independent and created its own rules, often modeled on the traditional art world. However, from 2020 to 2021, it was not yet entirely accepted by the conventional world of art, as evidenced by the lack of interest from significant traditional art collectors. However, the practices of other agents proved that these two worlds were getting closer. Auction houses played a crucial role in this process, as their policy was to incorporate CryptoArt within traditional artistic spheres. On the other hand, the presence of CryptoArt at the prestigious Art Basel fair in 2021 and its inclusion in the Art Basel Reports demonstrated its growing reputation in the classical world of art.

To summarize, the traditional art world’s reproduction occurred within the professional field. It manifested in institutionalization, the acquisition of the privilege to legitimate art, hierarchization and polarization, centralization, and ideological conflict emergence. Furthermore, as in traditional artistic circles, the roles of entities overlapped and duplicated (e.g., sales platforms played roles in distribution and perception, and artists were crucial in production and reception). The main difference between the conventional and CryptoArt worlds concerned the level of the virtualization of the NFT environment, which, despite increasing cooperation and acceptance by the traditional art world entities, remained digital in terms of the production and, primarily, distribution and perception of art.

The research results presented here are preliminary. They were limited by the small amount of NFT art data, the shortage of systematic sources, and the lack of detailed information about non-prestigious or non-influential entities of the CryptoArt world. Due to the short form of this paper, some generalizations were adopted, bearing in mind that the NFT art environment is more multidimensional and complex than it is described herein. It opens the way to further research work, on the one hand, devoted to the comparative characteristics of the NFT art world in different periods and in-depth research on individual entities and poles of the CryptoArt field. On the other hand, it invites the study of the CryptoArt world and its poles as a part of broader Internet phenomena. Additionally, there are questions – unaddressed here – about the artistic value of objects classified as NFT art, the methods of their artistic classification, the rules of their evaluation, and the criteria for their acceptance or rejection in terms of esthetics. This would necessitate a focus on artworks themselves, which is promoted by the perspective of the new sociology of art (de la Fuente, 2007). Another promising direction would be to search for and reveal overt and hidden interactions in the world of crypto art, including the informal connections among its participants, similar to the work of Mulkay and Chaplin (1982), who examined the context of Jackson Pollock’s success in the traditional art world. Moreover, it would be beneficial to reflect on the primary and secondary NFT art market in the context of Neil Cummings’ observation that in the traditional art world, “If the primary market relies on deep, personal and complex relationships between artists, gallerists, and collectors, then in the secondary market, artworks circulate through looser, more diverse and contingent networks outside the manipulation and monopolization of the primary market” (Cummings, 2014: 41–42). Attention may also be devoted in the future to a deeper analysis of the trajectories of individual careers – not only artists – but also other entities in the field of art, including, above all, curators, who, as Michael Brenson (1998) points out, play a central role in the conventional art world. The analysis proposed here can also be a starting point for research in other areas of NFT production (music, collectibles, sports) and the social worlds that have emerged around them.

Cytowanie

Barbara Lewicka (2025), The CryptoArt World in 2020–2021: The Reproduction of the Known, „Przegląd Socjologii Jakościowej”, t. XXI, nr 1, s. 76–97, https://doi.org/10.18778/1733-8069.21.1.04)

Alexander Victoria D., Bowler Anne E. (2021), Contestation in aesthetic fields: Legitimation and legitimacy struggles in outsider art, “Poetics”, vol. 84, 101485, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2020.101485

Almeda Shm Garanganao, Hartmann Bjoern (2023), NFT Art World: The Influence of Decentralized Systems on the Development of Novel Online Creative Communities and Cooperative Practices, Conference materials: DIS ‘23, July 10–14, 2023, Pittsburgh, pp. 353–370, https://doi.org/10.1145/3563657.3596034

ARTnews (2021), Top 200 Collectors, https://www.artnews.com/art-collectors/top-200-collectors/top-200-collectors/ [accessed: 2.04.2024].

Art Rights (2021), 5 Great Crypto Art Collectors, https://www.artrights.me/en/5-great-collectors-of-crypto-art/ [accessed: 2.04.2024].

Artsy (2022), The Artsy Gallery Insights: 2022 Report, https://partners.artsy.net/resource/2022-gallery-insights-report [accessed: 2.04.2024].

Baumann Shayon (2007), A general theory of artistic legitimation: How art worlds are like social movements, “Poetics”, vol. 35(1), pp. 47–65, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2006.06.001

Becker Howard S. (1976), Art Worlds and Social Types, “American Behavioral Scientist”, vol. 19(6), pp. 703–718, https://doi.org/10.1177/000276427601900603

Becker Howard S. (2008), Art Worlds, Berkeley: University of California Press.

Boido Claudio, Aliano Mauro (2023), Digital art and non-fungible-token: Bubble or revolution?, “Finance Research Letters”, vol. 52, 103380, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2022.103380

Bourdieu Pierre (1996), The Rules of Art: Genesis and Structure of the Literary Field, Redwood City: Stanford University Press, https://doi.org/10.1515/9781503615861

Bourdieu Pierre (2015), Manet: A Symbolic Revolution, Cambridge: Polity.

Brenson Michael (1998), The Curator’s Moment, “Art Journal,” vol. 57(4), pp. 16–27, https://doi.org/10.1080/00043249.1998.10791901

Brown Kate (2021), NFTs Make Their Debut at Art Basel, Where Collectors Are Curious – And a Bit Confused – About the New Art Medium, https://news.artnet.com/market/nfts-art-basel-2011438 [accessed: 2.04.2024].

Cabin VC (2021), NFT Industrial Development Report Q1 2021, https://web.archive.org/web/20221130084105/https://www.cabin.vc/img/NFTIndustrialDevelopmentReportQ12021-EN.pdf [accessed: 2.04.2024].

Cascone Sarah (2021), The 10 Most Expensive NFT Artworks of 2021, From Beeple’s $69 Million ‘Everydays’ to XCOPY’s $3.8 Million Portrait of ‘Some Asshole’, https://news.artnet.com/market/most-expensive-nft-art-yearend-2052822 [accessed: 2.04.2024].

Castells Manuel (2012), Networks of Outrage and Hope. Social Movements in the Internet Age, Cambridge: Polity.

Christie’s (2021), A record-breaking year at Christie’s: 2021 in numbers, https://www.christies.com/features/christies-auction-highlights-2021-12019-1.aspx?sc_lang=en [accessed: 2.04.2024].

Clark Mitchell (2021), NFTs, explained, https://www.theverge.com/22310188/nft-explainer-what-is-blockchain-crypto-art-faq [accessed: 2.04.2024].

Colavizza Giovanni (2023), Seller-buyer networks in NFT art are driven by preferential ties, “Frontiers in Blockchain”, vol. 5, pp. 1–12, https://doi.org/10.3389/fbloc.2022.1073499

Crane Diane (1992), The Production of Culture: Media and the Urban Arts, California: Sage Publications, https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483325699

Cummings Neil (2014), Joy Forever, [in:] Michał Kozłowski, Agnieszka Kurant, Jan Sowa, Krystian Szadkowski, Kuba Szreder (eds.), Joy Forever: The Political Economy of Social Creativity, Warszawa: Fundacja Bęc Zmiana, pp. 31–47, https://mayflybooks.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/9781906948191-web.pdf [accessed: 14.10.2024].

Dash Anil (2021), NFTs Weren’t Supposed to End Like This, https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2021/04/nfts-werent-supposed-end-like/618488/ [accessed: 2.04.2024].

Dickie George (1974), Art and the Aesthetic: An Institutional Analysis, Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

DiMaggio Paul (1986), Structural analysis of organizational fields: A blockmodel approach, [in:] Barry Stew, L.L. Cummings (eds.), Research on Organizational Behavior: An Annual Series of Analytical Essays and Critical Reviews, Greenwich: JAI Press, pp. 335–370.

Eden Gallery (2021), Crypto Art: What is it & How Does it Work?, https://www.eden-gallery.com/news/what-is-crypto-art [accessed: 2.04.2024].

Evans Toynia M. (2019), Cryptokitties, cryptography, and copyright 1 – BYU Copyright Symposium, “AIPLA QJ”, vol. 47, pp. 219–247, https://www.readkong.com/page/cryptokitties-cryptography-and-copyright-1257924 [accessed: 2.04.2024].

Foster Hal, Krauss Rosalind, Bois Yve-Alain, Buchloh Benjamin H.D., Joselit David (2004), Art Since 1900, London: Thames & Hudson.

Franceschet Massimo, Colavizza Giovanni, Smith T’ai, Finucane Blake, Ostachowski Martin Lukas, Scalet Sergio, Perkins Jonathan, Morgan James, Hernández Sebastián (2021), Crypto Art: A Decentralized View, “Leonardo”, vol. 54(4), pp. 402–405, https://doi.org/10.1162/leon_a_02003

Fuente Eduardo de la (2007), The ‘New Sociology of Art’: Putting Art Back into Social Science Approaches to the Arts, “Cultural Sociology,” vol. 1(3), pp. 409–425, https://doi.org/10.1177/1749975507084601

Google Trends (n.d), FAQ about Google Trends data, https://support.google.com/trends/answer/4365533?hl=en [accessed: 2.04.2024].

Grba Dejan (2023), Faux Semblants: A Critical Outlook on the Commercialization of Digital Art, “Digital”, vol. 3(1), pp. 67–80, https://doi.org/10.3390/digital3010005

Haaften-Schick Lauren van, Whitaker Amy (2021), From the Artist’s Contract to the Blockchain Ledger: New Forms of Artists’ Funding Using Equity and Resale Royalties, „SSRN Electronic Journal”, January, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3842210

Hamacher Adriana, Hayward Andrew (2021), 15 Biggest NFT Influencers of 2021, https://decrypt.co/89158/15-biggest-nft-influencers-of-2021 [accessed: 2.04.2024].

Heinich Nathalie (2004), The Sociology of Art, London: Routledge.

Hirsch Paul M. (1972), Processing Fads and Fashions: An Organization-Set Analysis of Cultural Industry Systems, “American Journal of Sociology”, vol. 77, pp. 639–659, https://doi.org/10.1086/225192

Kinsella Eileen (2021), Think Everyone Is Getting Rich Off NFTs? Most Sales Are Actually $200 or Less, According to One Report, https://news.artnet.com/market/think-artists-are-getting-rich-off-nfts-think-again-1962752 [accessed: 2.04.2024].

McAndrew Clare (2023), Art Basel & UBS Report ‘The Art Market 2022’, https://web.archive.org/web/20230326102749/https://d2u3kfwd92fzu7.cloudfront.net/Art%20Market%202022.pdf [accessed: 2.04.2024].

Mitu Florina-Gabriela, Bota Marius (2023), Exploratory Research on Using NFT for Selling Digital Art, [in:] Adina Letiția Negrușa, Monica Maria Coroş (eds.), Remodelling Businesses for Sustainable Development. 2nd International Conference on Modern Trends in Business, Hospitality, and Tourism, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, 2022, Cham: Springer, pp. 39–50, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-19656-0_4

Mulkay Michael, Chaplin Elizabeth (1982), Aesthetics and the Artistic Career: A Study of Anomie in Fine Art Painting, “Sociological Quarterly”, vol. 23, pp. 117–138, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.1982.tb02224.x

Nadini Matthieu, Alessandretti Laura, Di Giacinto Flavio, Martino Mauro, Aiello Luca Maria, Baronchelli Andrea (2021), Mapping the NFT revolution: Market trends, trade networks, and visual features, “Scientific Reports”, vol. 11, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-00053-8

NFTPlazas (2021), Curators in the CryptoArt Scene – A Necessary Controversy, https://nftplazas.com/cryptoart-curation/ [accessed: 2.04.2024].

Non-Fungible (2021), Non-Fungible Tokens Yearly Report 2020, https://nonfungible.com/reports/2020/en/yearly-nft-market-report-free [accessed: 2.04.2024].

Non-Fungible (2022), Yearly NFT Market Report 2021, https://nonfungible.com/reports/2021/en/yearly-nft-market-report-free [accessed: 2.04.2024].

Pawelzik Leon, Thies Ferdinand (2022), Selling Digital Art for Millions – A Qualitative Analysis of NFT Art Marketplaces, “ECIS 2022 Research Papers”, vol. 53, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/361461561_SELLING_DIGITAL_ART_FOR_MILLIONS_-A_QUALITATIVE_ANALYSIS_OF_NFT_ART_MARKETPLACES [accessed: 2.04.2024].

Peterson Richard A. (1994), Culture studies Though Production Perspective: Progress and Prospects, [in:] Diana Crane (ed.), The Sociology of Culture, Hoboken: Blackwell, pp. 163–190.

Santillana (2021), The 20 Top-Selling NFT Artists to Collect Right Now, https://web.archive.org/web/20241112011917/https://gothammag.com/top-selling-nft-artists [accessed: 2.04.2024].

Shaurya Thapa (2022), 20 Most Expensive NFTs Sold (So Far), https://screenrant.com/expensive-nfts-sold-so-far [accessed: 2.04.2024].

Statista (2021), Value of sales involving a non-fungible token (NFT) in gaming, art, sports and other segments from 2018 to 2021 (in million U.S. dollars), https://www.statista.com/statistics/1221400/nft-sales-revenue-by-segment/ [accessed: 2.04.2024].

Statista (2023), NFT art market, https://www.statista.com/study/112518/nft-art-market/ [accessed: 2.04.2024].

SuperRare (2020), Governance 101: How does the SuperRare DAO work?, https://help.superrare.com/en/articles/5429518-governance-101-how-does-the-superrare-dao-work [accessed: 2.04.2024].

SuperRare (2021), From Michelangelo to the metaverse: the past, present and future of art markets, https://medium.com/superrare/from-michelangelo-to-the-metaverse-the-past-present-and-future-of-art-markets-89d846fdd44b [accessed: 2.04.2024].

Taddei Mario (2021), My last NFT. Milão, https://twitter.com/MarioTaddei72/status/1393289985403637764/photo/ [accessed: 2.04.2024].

Thorton Sarah (2008), Seven Days in Art World, New York: Norton & Co.

Valeonti Foteini, Bikakis Antonis, Terras Melissa, Speed Chris, Hudson-Smith Andrew, Chalkias Konstantinos (2021), Crypto Collectibles, Museum Funding and OpenGLAM: Challenges, Opportunities and the Potential of Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs), “Applied Sciences”, vol. 11(21), 9931, https://doi.org/10.3390/app11219931

Vasan Kishore, Janosov Milan, Barbasi Albert Laslo (2022), Quantifying NFT‐driven networks in crypto art, “Scientific Reports”, vol. 12, 2769, http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-05146-6

White Harrison, White Cynthia (1965), Canvases and Careers: Institutional Change in the French Painting World, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Yilmaz Tuba, Sagfossen Sofie, Velasco Carlos (2023), What makes NFTs valuable to consumers? Perceived value drivers associated with NFTs liking, purchasing, and holding, “Journal of Business Research”, vol. 165, 114056, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2023.114056

Zhong Howard, Hamilton Mark (2023), Exploring gender and race biases in the NFT market, “Finance Research Letters”, vol. 53, 103651, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.frl.2023.103651