https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0618-2066

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0618-2066

University of Wrocław, Poland https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0618-2066

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0618-2066

Abstract:

In the context of past winners of the Pritzker Architecture Prize, how can one interpret the decision to honor the architectural work of Francis Kéré in 2022? This article problematizes the West’s interest in African architecture. Is it really due to the fact that African architecture excels in conditions of scarcity and climate crisis? The 18th Venice Architecture Biennale shows that Africa can be regarded as a kind of the “laboratory of the future.” Or is the Pritzker Architecture Prize more of a patronizing and orientalizing gesture that renders African architecture a curiosity, while the Global North chasteningly points out that it is time to rein in the overly spectacular ambitions of contemporary starchitecture, which has neglected its social role? The posed questions direct the analysis toward Kéré’s architecture being interpreted as a local variant of modernism, and his work as a kind of advocacy. Jyoti Hosagrahar’s helpful concept of Indigenous Modernities is invoked as a medium through which Africa’s emerging and important current of participatory architecture may be viewed from the postcolonial perspective and considered beyond the center – periphery opposition.

Keywords:

Indigenous Modernities, African architecture, Francis Kéré, modernism, colonialism, postcolonial perspective

Abstrakt:

Jak w kontekście dotychczasowych laureatów nagrody The Pritzker Architecture Prize można interpretować decyzję o wyróżnieniu w 2022 roku architektonicznej działalności Francisa Kéré? W artykule problematyzowane jest faktyczne zainteresowanie afrykańską architekturą. Czy rzeczywiście wynika ono z tego, że afrykańska architektura doskonale sprawdza się w warunkach niedoborów i kryzysu klimatycznego? 18 Venice Architecture Biennale pokazuje, że Afrykę można traktować jak swoiste „laboratorium przyszłości”.

A może The Pritzker Architecture Prize to raczej protekcjonalno-orientalizujący gest, który czyni z afrykańskiego architekta ciekawostkę, a Globalnej Północy karcąco wskazuje, że czas powstrzymać nadmiernie spektakularne ambicje współczesnej starchitektury, która zapomniała o swojej społecznej roli?

Postawione pytania kierują analizę w stronę architektury Kéré, interpretowanej jako lokalna odmiana modernizmu, i jego działalności jako swoistego rzecznictwa. Pomocna koncepcja rdzennych nowoczesności (Indigenous modernities) Jyoti Hosagrahar jest przywoływana jako medium, za pomocą którego można postrzegać z perspektywy postkolonialnej rodzący się w Afryce niezwykle ważny nurt architektury partycypacyjnej, rozpatrywany poza opozycją centrum – peryferia.

Słowa kluczowe:

rdzenne nowoczesności, architektura afrykańska, Francis Kéré, modernizm, kolonializm, postkolonialna perspektywa

When Francis Kéré won the “architectural Nobel Prize” in 2022, those interested in architecture on the one hand rejoiced that perhaps we were witnessing at last an appreciation of sustainable, environmentally-respectful, human-scale architecture. It was a hope for the end of the triumph of big capital and the esthetic sophistication of Western architecture. Others, less enthusiastic, appreciated Francis Kéré’s architecture as an exotic curiosity, an indulgent and affectionate look from the global center to the African periphery. How should we interpret this award today? Who is Francis Kéré, and what is African architecture? To answer these questions, I have chosen the case study method, for it is through this method that one can capture and nuance all of the characteristic features of the context in which the phenomena analyzed here are embedded. African architecture viewed from a non-African perspective requires special attention paid to spatiality, locality, and globality, to the specific time when certain events in the world of architecture are happening, to its absent history, to the social context of migration and climate crisis. Through the case study, all of the contextualized problems mentioned here are brought into focus[1]. The method as it is applied here is used to explain the phenomenon of architecture as a tool of power in the broadest sense (the power to look, to judge, to valorize). Of course, this does not relate to explanatory possibilities in the sense of the methodology of the natural sciences, but, rather, to a form of explanation that the humanities call critical interpretation using specific theoretical concepts – in this case based on critical postcolonial theory, engaging the notion of Indigenous Modernities proposed by Jyoti Hosagrahar (2005). This is a thick description in the Geertzian sense (Geertz, 1973).

When analyzing an architectural prize or architecture biennial, as well as architectural press and academic research in the field of architecture, I treat them all as discursive practices played out within architecture. These practices take place in the domain of the center – the Global North – and are conducted under the rules set by that culture[2]. The Pritzker Architecture Prize is thus analyzed here as a practice of distinction (Pierre Bourdieu), reward, and differentiation; as a social institution that determines the order, hierarchy, and structure of the world of architects, and in this sense is part of the order of symbolic power; it is also part of the writing of architectural history. In turn, the architecture biennial, in addition to the aforementioned function, also serves as a critical practice, not only interpreting how architects interpret reality and the role of architecture. In addition, this derivative hermeneutics is conducted as a certain emancipatory strategy – a critical one, to be precise.

I am therefore applying discourse analysis:

The analysis of discourses devoted to African architecture – but practiced mainly in the center, in the Global North – prompts the adoption of the postcolonial perspective that problematizes the center – periphery opposition and allows us to look at the discursive practices analyzed using the category of Indigenous Modernity (J. Hosagrahar, H. Haynen). This makes it possible to see African architecture as modern, but at the same time raises the question of the nature of modernism and its internal contradictions: is it a colonial, exclusionary, and oppressive architectural style, or a tool for social change? The case of Francis Kéré is examined from the postcolonial perspective of the transfer of ideas, of the merging of the global with the local.

The adopted methodology makes it possible to build an interpretation-dense description of this architect’s activities as an advocate (rather than an expert in the Western European sense, as the possessor of specialized, socially-inaccessible knowledge protected by the authority of expertise and science). It also makes it possible to take a critical look at the hegemonic position taken by the West, despite its declared position of favoring equality, and to expose its strategies of orientation and marginalization, or the played-out fascination with simplicity and sensitivity (“noble savage” versus indulgent, spectacular architecture). This phenomenon has already been well diagnosed by Olu Oguibe, and his selected studies of various cases (non-Western artists) have revealed the facade and hegemonic nature of the “culture game” (2004). The discourse analysis proposed here using Jyoti Hosagrahar’s categories of Indigenous Modernity provides new research perspectives and a basis for interpreting Francis Kéré’s modernist architecture and the architect’s projected role (as an agent of change) beyond the opposition of tradition–modernity, progressive–backward, global–local, and at the same time allows us to question not only the authority of a certain narrative about Western modernist culture – to see it in a much more pluralistic fashion (pluralism of modernism) – but also, going a step further, to delegitimize or unmask the condescending and domineering gestures toward the periphery and decolonizing thinking about Africa.

The International Pritzker Prize, commonly known as “architecture’s Nobel,” is awarded annually to living architects for their significant achievements. It was established by hotel magnates, the Pritzker family of Chicago, through their Hyatt Foundation in 1979.

The current chairman of the foundation says that the Pritzker family was deeply aware of the role architecture holds, residing in the city that birthed the skyscraper and filled with buildings designed by legendary architects, such as Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright, Mies van der Rohe, to name but a few (www.pritzkerprize.com).

Therefore, it can be argued that the founders of the award, on the one hand, appreciate the art of architecture and understand its influence on human behavior and the shaping of cities; on the other hand, through the phenomenon of this award, it is apparent that architecture – like no other art – is strongly linked to power relations. Specifically, architecture is linked with capital. Architecture is the language of power, simply because it is impossible to realize a building without having access to someone who has capital and will finance the project. When completed, it, in turn, will influence people’s behavior, the shape of cities, lifestyles, and public space.

However, those awarded the Pritzker Architecture Prize so far have usually been men and from the rich Global North, such as Robert Venturi, Frank Gehry, Rem Koolhaas, etc. The first female architect, Zaha Hadid, was not awarded until 2004, followed by Ivonne Farrell and Shelley McNamara in 2020, and the duo Anne Lacaton and Jean-Philippe Vassal in 2021.

The 2022 Pritzker Prize for Architecture was won by Diébédo Francis Kéré, a native of Burkina Faso, educated in Berlin, and the first dark-skinned architect in the history of the award. His architecture is far from spectacular, focusing on the budget, climate, the availability of materials, and the skills and ability of the local community[3].

This is not his one and only international award. His first was the Aga Khan Award for Architecture (2004). This award is unique for architects working in the so-called developing countries of Asia, Arya, and the Middle East. Established in the 1970s, it was a response to the state of architecture after the colonial period. Kéré has won many honors and awards in the world of architecture, but the Pritzker is considered in the area of the Global North as special, more prestigious[4].

I would call Francis Kéré a spokesperson for African architecture. Despite his educational background, winning the architectural Nobel, having been a guest speaker at many of the world’s universities[5], joining the New European Bauhas roundtable (New European Bauhaus…, 2022), and having his unquestionable insight into design, he does not position himself as an expert. His involvement on behalf of African architecture as a manifestation of sustainable development and climate consciousness – as well as his vision and concepts for the future goals of architecture, its participatory dimension, and its promotion in Africa – makes him someone far beyond this narrowly specialized social role. His expertise extends to broad non-academic and non-specialist circles. His speeches, lectures, and presentations are more of a dialog to raise awareness of what is happening beyond the Global North, and of Africa’s cultural and environmental contexts. They are vivid, self-referencing, autobiographical, reconstructing the journey he went through, both as a young man leaving Burkina Faso and as an architect with a sense of duty to the place he came from (many of his autobiographical and visionary speeches can be found online: Kéré, 2012a). This kind of engaged advocacy is an opportunity to promote the idea of local architecture, based on participation, community, respect for the environment, and the use of local materials.

Francis Kéré’s biography is quite well-known, and one would assume it does not need mentioning, but it is significant (for the only monograph on Francis Kéré to date, see Lepik, Beygo, 2016). It gives voice to the difficult path that an architect of African descent is made to follow, something that is not obvious to a European. Context, after all, is of great importance. Kéré often emphasizes in interviews and public appearances what a huge step forward it was for him to leave Burkina Faso, receive a scholarship in Berlin, and start studying at the Technische Universität, graduating in 2004[6]. He is also aware of the special privileges he enjoys; he began with a financial debt, which resulted from Gando’s local community pitching in for his education, but also the debt of hope and trust that the villagers placed in him. While he was a student, Francis Kéré sold his handmade drawings, organized fundraisers among his fellow students, and in 1998 he founded the Schulbausteine für Gando Foundation – today’s Kéré Foundation. In 2001, while still a student, Kéré returned to Gando to repay the debt, building an elementary school. Public buildings in Burkina Faso and many other African countries are often erected with concrete, which has symbolic (colonial) significance. The construction process is expensive, complicated, and requires access to specialists and electricity, unavailable in Gando and in most other villages in Africa. This means that concrete is an “alien” material, degrading the environment, disregarding the climate, past building and spatial practices, in addition making residents feel reliant on its availability and specialists (Choplin, 2023, in particular chapter: “Uninhabitable Concrete”).

All this led Kéré to decide to build with clay, a material that is widely available in his country, inexpensive, and easy to work with. In Gando, this did not arouse enthusiasm; the designs were considered unmodern and unsustainable. As the residents claimed, “The clay can’t withstand the rainy season, and Francis wants us to build a school out of it. He spent so much time studying in Europe instead of working with us in the fields for this?” (Kéré, 2012a; 2018; see also: Rodgers, 2014). In Burkina Faso, people traditionally build with clay, but they do not see its potential. “That’s what I used my studies in Berlin for – I learned to combine traditional techniques and materials with modern technologies,” as Kéré explains during his lectures.

The architectural process began with long and difficult discussions. Before the physical work began, Kéré, as in a laboratory, had built prototypes, experimented, done tests, taught, and persuaded villagers of his ideas and technological solutions.

We made a brick and put it in a bucket of water, where it stayed for five days. After that period, we took it out and the block was still solid. That’s convincing. (Baratto, 2022)

The production of bricks and clay blocks was not only cheap but also relatively easy, ensuring the participation of the local community in the project. After all, collaborative construction is a common practice in African villages. The technology was developed in such a way as to allow everyone to participate in the process. This involvement helped to expand local know-how through the use of new technological solutions, but also to deepen the understanding of the existing construction practices, identify flaws, and bring residents closer to what Richard Sennett calls “material consciousness” (Sennett, 2009: 119–146).

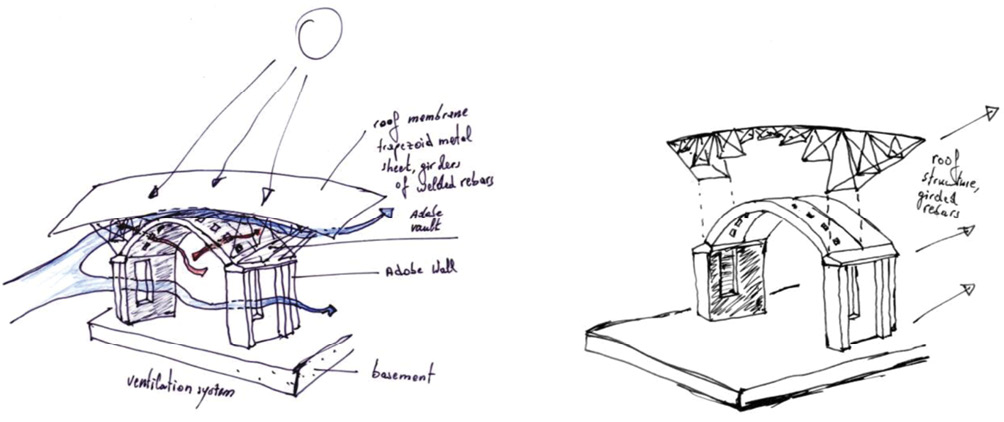

The clay walls were further protected by a wide sheet metal roof projecting beyond the building’s outline. This, in turn, was associated by the residents with a material that was completely impractical, heating up rapidly, and releasing heat just as quickly inside the building. Besides, it was regarded as an “unwanted gift” or, rather, as garbage from the West. Kéré explained to the residents how ventilation worked and that the sheet metal raised on ribbed structures above the perforated brick vaulted ceiling “collects” the heat, effectively protecting the interiors from overheating. By using simple drawings, he had to explain complicated technical issues to people who were never taught to read and write. He built a prototype clay vault and encouraged people to jump on it, proving to the locals that it worked. Only then did they allow the construction to commence. Kéré also discovered the virtues of laterite, a sedimentary rock found in Burkina Faso that hardens in the sun when mined and exposed to air, making it ideal as a building material.

Illustration 1. Natural ventilation in School Extension. Sketch by Francis Kéré

Source: Kéré Foundation, n.d., Architecture.

The Gando school, built in 2001, is the first of many projects the Burkinabé architect has completed in his homeland (Kéré, 2012b). It proved so popular that it was significantly expanded in the following years. In the beginning, it was intended for just over a hundred students; today there are as many as 350 children studying there, with another 150 waiting for admittance. Alongside the main structure, a complex of houses for teachers was also built. Kéré figured that only by providing good living conditions would it succeed in attracting teachers to a poor village in the middle of nowhere.

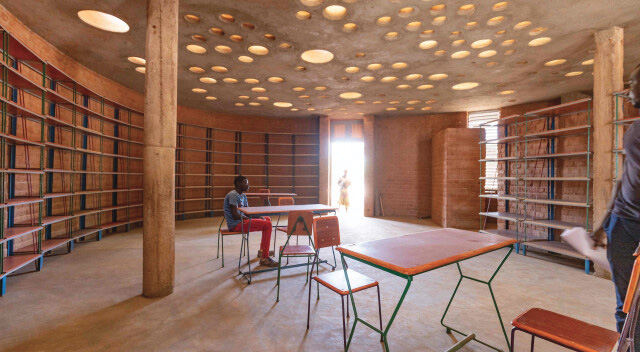

His next project was a library in Gando, a place where children as well as adults could learn to read and write. As basic building materials were often in short supply, clay pots and jugs containing food and water were used to build the library, creating vents that give an outlet for the hot air and let in daylight by functioning as skylights.

Illustration 2. Formwork for clay brick ceiling, School Extension. Photo by Francis Kéré

Source: Kéré Foundation, n.d., Collaboration.

Illustration 3. Women carrying clay pots. Photo Francis Kéré

Source: Kéré Foundation, n.d., Resources.

Illustration 4. Gando School Library, formwork concrete ceiling. Photo by Kéré Architecture GmbH

Source: Kéré Foundation, n.d., Education.

Illustration 5. Gando School Library

Source Kéré Foundation, n.d., Education.

All of the projects in Gando are always related to educating people, consequently making the local community more proactive as well as having a causative effect on their environment and surroundings. That way, “people are able to use their skills to make money themselves. Architecture can be inspiring for communities to shape their own future,” as Kéré explains (Kéré, 2012a).

What can and certainly should be mentioned is that Francis Kéré’s architecture is modernist in the sense specified by the first German modernists, with Ernst May in the vanguard. It is an instrument of social change involving the emancipation of the local population, including women[8] and children; it also takes into account and respects the local environmental, social, and economic context. It is engaged and performative in the sense that it influences the formation of social relations. Architecture is not about buildings, but about the process of building – a process during which the transformation of each member of the community, of every one building, takes place. It strengthens ties and makes people feel proud and empowered, but also teaches craftsmanship, the understanding of construction processes, and material consciousness, while also granting livelihood.

Illustration 6. Polishing a rammed earth floor. Photo Francis Kéré

Source: Kéré Foundation, n.d., Resources.

One of the largest projects Kéré is currently involved in is the development of a complex called Opera Village in Laongo. He designed a complex of buildings located on 14 hectares (34 acres) of land, which includes residential buildings, a school, nursery, health center, and a section dedicated to the arts – art studios and workshops, a gallery, and an auditorium for 500 viewers. This brings to mind Ernst May’s comprehensive social housing projects in Frankfurt, which provided public spaces and social services for its residents – a true modernist social laboratory. Although the scale is causing controversy due to its grandeur, Kéré stands by it, explaining that although Burkina Faso is a poor country, its people do have a sense of dignity, and projects such as Opera Village help create a sense of community and self-worth. Housing in many parts of Africa is underdeveloped, and people live in dire conditions. This is not an outcome of laziness. The cause is the lack of education and opportunities. As Kéré demonstrates, these shortages can be eliminated through a cheap, affordable, and easily accessible architectural process.

Is it even warranted to attribute modernist characteristics to Francis Kéré’s architecture? By this comparison, are we not falling into the colonial trap of the Western civilization’s fascination with simple, primitive architecture? Is the Pritzker Prize a kind of cultural game here, as Olu Oguibe wrote? Or is it an alibi for the modern remorse associated with overblown ambition and overgrown, spectacular architecture? Does an increasingly civilizationally-advanced modernity have more and more problems eliminating the irrational solutions and construction techniques which it itself produces? The legitimacy of posing such questions is substantiated in Hilde Heynen’s excellent text titled “The Intertwinement of Modernism and Colonialism” (Heynen, 2013). The postcolonial perspective adopted by the author makes us look with a sensitive eye at our Eurocentric, greedy, appropriating interpretations involving the attribution of modernist features to African architecture. On the other hand, however, we cannot overestimate the hegemonic role of modernity. After all, it dispersed from the center to the periphery and took on different forms in the process (e.g., tropical modernism). Therefore, let us look at the ambivalences of modernism.

If architecture itself is the language of power, then modernism conquers its position. Why is modernism unusual, special in this? Through its use of functionalism, with universality as its key, modernism imposes, bleaches, levels, removes localisms, as well as manifests and preaches[9]. It has built its rhetoric on ethics. It perceives society as an art form (Le Corbusier, 1925/1980). However, modernism is ambiguous. It is important to recall that during the first Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM), there was an extremely important discussion taking place on determining the role of architecture. One side was represented by Le Corbusier and the other by Ernst May and his associates, including Sigfried Giedion. For the latter, the aim was to establish and promote an idea of architecture that would meet the most common needs of the masses – housing (habitat) and emancipation were the main concerns. Hence, while Le Corbusier viewed architecture as an end in itself, May saw it as a tool for social change (Bauer, 1934; Syrkus, 1976; Giedion, 1985; Matysek-Imielińska, 2020: 37–59).

Thus, the inherent inconsistency of modernism lies in the fact that, on the one hand, it brought emancipation and improved living conditions, but on the other hand, at its inception, it was an instrument of exclusion, as not everyone suited the esthetic vision of the new society, the modern human being, and the new vision of the city. By losing the qualities it was initially so proud of, forfeiting political and social programs, it started focusing on style, ultimately becoming a cold and distant form. It could be argued that since the 1980s modern architecture has turned away from its original role and has become an expression of its negation.

Past Pritzker Prize winners are heirs to modernism in a twofold sense, i.e., both in terms of style and ideology. They create architecture that is spectacular, dignified, timeless, functional, and using concrete, steel, and glass. On the other hand, behind it still lies Le Corbusier’s (colonial) idea of a new esthetic; a civilizational, progressive model of society – the unfulfilled fantasy of modernity.

This, of course, does not mean disregarding architecture built by the people and for the people, from the bottom up. Vernacular architecture exists, of course, but it is not the one that structures the symbolic order and the history of architecture. However, among the many socially-engaged architects, the work of Alejandro Aravena and his elemental housing project is worth mentioning, as well as his curatorial work at the 15th International Architecture Exhibition, entitled Reporting from the Front (ELEMENTAL, 2012; Aravena, 2016). That same year, El Anatsui, a Ghanaian artist living in Nigeria, received the Golden Lion at the 56th Venice Biennale for lifetime achievement.

In this regard, we can also witness a harbinger of change. For example, on 9th and 10th June, 2022, the Reconstructing the Future for People and Planet conference was held in Rome, whose organizers, Bauhaus Earth and the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, were particularly sensitive to local traditions. At the event, Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, the founder of the Bauhaus Earth, stated the following: “The conference will address a key challenge of our time: averting climate collapse by the deep and rapid transformation of the global built environment. The construction sector can go from climate villain to climate hero, especially by switching to bio-based materials such as timber and bamboo. This transformation will require an unprecedented collaboration between the Global South and the Global North, the integration of advanced technology and vernacular knowledge, and the re-entanglement of nature and civilization in urban space. This is why we convene a superb diversity of experts from around the world and across all relevant disciplines” (Florian, 2022).

Adopting modernist design principles does not immediately mean accepting the dominance of the Western discourse. The modernist idea of emancipation-through-architecture does not have to remain exclusively associated with Europeans, or with those who consider themselves to be more advanced or civilized. In light of postcolonial considerations, one should be extremely careful about pointing out that modernism, and modern architecture, are inextricably intertwined with a belief in the superiority of the West, and associated with its condescending, orderly, and appropriating nature. Heynen subheads her article: “The Hopes Embodied in Modernism”, and in it she suggests that it is from this postcolonial perspective that we should view the hope embodied in modernism. She deconstructs two commonly held assumptions – that modernity belongs exclusively to the West and that architecture and modernism are a matter of style. Architects not only design and construct buildings, but through architecture they aim to change the world, and they do so not only in the West. Here, she recalls Sigfried Giedion’s book Befreites Wohnen, the very title of which indicates that architecture was meant to liberate people from oppression and deprivation. It is worth noting, in passing, that the social role of modernism is best realized by those architects and architecture researchers who, for whatever reason, happen to be on the periphery – in a broad sense, of course, situated at varying distances from the center of events. From the perspective of the Polish periphery, Helena Syrkus clearly understood the social role of architecture as well as the ideological conflict between Le Corbusier and May (Bauer, 1934; Syrkus, 1976; Giedion, 1985; Matysek-Imielińska, 2020). Hilde Heynen also sees this issue perfectly, as does the Indian architect Jyoti Hosagrahar, who is also a researcher, urban planner, and the current Deputy Director of the UNESCO World Heritage Center. Hosagrahar seeks to appreciate the pluralistic nature of modernism as well as to legitimize its various interpretations. She introduced the category of indigenous or local modernities, coining the term Indigenous Modernities (Hosagrahar, 2005). She advocates reconciling the abiding opposition between tradition and modernity. This is because tradition is associated with what is non-Western, regressive, while modernity with that which is Western, dominant, colonial, and progressive. As she states, “By questioning the cultural authority of this narrative about modernity and its manifestations in architecture and exploring the influence of politics in shaping ‘modern’ and ‘non-modern’ identities, we have a chance to recognize that all modernisms derive from the characteristics of the context in which they are embedded: place, time, history and community” (Hosagrahar, 2005: 13).

Given this conclusion, we can see that architectural projects, such as those in Gando, are created as hybrid phenomena – as local versions of modernity – of an understanding of progress, or of emancipation. This is a different modernity, not aspiring to that of Europe, not seeking, adapting, or imitating modernist forms. For Hosagrahar, the idea of “modernity” is a normative attribute, a tool for social change, culturally-constructed under the extreme injustices caused by colonialism and based on the view that buildings, spaces, and society are constitutively intertwined.

These forms, emerging through Kéré’s advocacy, cannot be examined in isolation from the cultural processes through which they are created and used. If modernism was colonial, it was so because it imposed, equalized, and disposed of locality. Today, localities can express their own language by using modernist solutions in a critical sense. That is why Francis Kéré’s architectural advocacy is so important, as he carefully outlines his context, by highlighting the social role of buildings, their educational component, and the local setting. His buildings are a reflection of the native African world. They are not esthetic objects. Rather, they show how the reshaping of life, labor, nature, and materiality occurs. Hosagrahar uses the term “indigenous” to emphasize context and locality. “Indigenous modernities denotes the paradoxical features of modernities rooted in their particular conditions and located outside the dominant discourse of a universal paradigm centered on an imagined ‘West.’ As a seemingly coherent ‘traditional’ built environment ruptures, indigenous modernities are expressed in the irregular, the uneven, and the unexpected. In the actualization of universal agendas in a particular place, indigenous modernities negotiate the uniqueness of a region and its history with the ‘universals’ of science, reason, and liberation. In using the term ‘indigenous’ I emphasize context and locality, the regional interpretations and forms of modernity rather than engage in an exercise of distinguishing endogenous and exogenous influences in architecture” (Hosagrahar, 2005: 6).

Through the category of Indigenous Modernities, we can understand that this polarization of “traditional” and “modern,” “ruler” and “subject,” or “East” and “West” is rooted in politics and has been constructed artificially.

Whether the Pritzker Prize is evidence of this, I am not quite certain. It could be an institutional “culture game” (Olu Oguibe), or a colonial gesture of orientalization (Said, 1979), owing to which the Western world is introduced to African architecture, and Francis Kéré’s work is rendered a kind of curiosity. Or perhaps it is late-modern remorse, a reckoning with the existing design practices of (increasingly harmful) spectacular architecture? One may wonder whether the discernible commitment of Kéré’s work to climate action (the 13th Sustainable Development Goal of the United Nations) and the need to prioritize the issues of climate change have played any role in attracting the Jury’s attention to his work. Is it also a reflection of Kéré’s understanding of the Western culture game? It seems, however, that his understanding of the consequences of climate change comes not so much from the discernment of a double consciousness or a cultural game, but, simply, from surviving in climatically harsh conditions, which he knows very well because of where he comes from. At the award ceremony, Kéré said: “What are the challenges today? What is our big concern today? Climate crisis is real, material is limited. If we take everything, it’s finito, there’s no more… Conflicts for resources will intensify everywhere around the world, and population growth is imminent. No matter where we are from, this should concern us.”

Does the architecture of the Global North give expression to such concerns? Does it care about resources?

It feels as if the prize judges were pointing out to modern architects what lessons they should learn from those developing countries that are destined for economics and, needless to say, architectural scarcity. Why is this only an impression? Because, it seems, it is a passing phenomenon for now.

After all, modernism has forgotten that architecture is communal, as opposed to individualized, and that it brings buildings into line with their natural surroundings, as opposed to starchitecture, which disregards the landscape as well as social and cultural contexts. It has forgotten that it seeks to create protected, well-defined spaces, as opposed to the gargantuan, urban sprawl primarily symbolizing capital and class-based housing, that it is sensitive to solving practical problems rather than focused on style and spectacular form, and that it is humane, in the sense that it serves the common good rather than generating income.

My doubts stem from the ambivalence present in the global architectural scene. Following the award for Kéré and noting sustainable architecture, the 2023 Pritzker Prize went to Sir David Alan Chipperfield, focused on the elegant heritage of the Western world. In addition to the already mentioned hopeful example of the Reconstructing the Future for People and Planet conference, we can add the 18th Venice Biennale of Architecture, curated by African-born Lesley Lokko, who is a Ghanaian-Scottish architect, lecturer, and researcher, as well as the founder and director of the African Futures Institute (AFI) based in Accra, Ghana.

This year’s Biennial’s title, proposed by Lokko, is “The Laboratory of the Future”. The curator is convinced that the real laboratory of the future – i.e., what awaits us in the not-too-distant future – is contemporary Africa, with its many issues related to the climate crisis, water, and housing shortages, as well as rampant urbanization. In its official statement explaining the reason for this topic, Lokko pointed out two aspects:

Firstly, Africa is the laboratory of the future. We are the world’s youngest continent, with an average age half that of Europe and the United States, and a decade younger than Asia. We are the world’s fastest urbanizing continent, growing at a rate of almost 4% per year. This rapid and largely unplanned growth is generally at the expense of local environment and ecosystems, which put us at the coal face of climate change at both a regional and planetary level (Lesley Lokko…, 2022).

The second aspect concerns the exhibition itself, reminiscent of the workshop from which the laboratory originated, as Richard Sennett shows. Thus, it is about collaboration, cross-learning, joint methodical meandering, searching for solutions. “We envisage our exhibition as a kind of workshop, a laboratory where architects and practitioners across an expanded field of creative disciplines draw out examples from their contemporary practices that chart a path for the audience – participants and visitors alike – to weave through, imagining for themselves what the future can hold” (Lesley Lokko…, 2022).

For the first time in the Biennale’s history, the focus was on Africa and the African diaspora. African practitioners – and it is worth noting that Lokko deliberately goes beyond the narrow category of architect, bringing to mind Marcus Miessen’s category of critical spatial practitioners – account for half of all participants in the exhibition and are described as agents of change. They have been asked to show Africa as the focus of all issues of inequality, race, scarcity, and fear, but also hope. The Biennale showcased a number of artistic and architectural decolonization practices, attempting to reimagine Africa without colonial influences (e.g., Nigerian artist Olalekan Jeyifous). Lesley Lokko’s outlook on Africa is intended first and foremost to decolonize how we think about the continent, its people, and space. It is also worth noting the prizes awarded in this year’s Biennale and the justifications for these choices[10]. Thus, in keeping with the exhibition’s slogan, forward thinking focused on decolonization, decarbonization, and localism was appreciated.

The curator points out that ethnic or national minorities, viewed from the European perspective, are, de facto, the majority of the world’s population. Not only in the countries of the Global South or the Arab World, but also in Europe, the subjugated or colonized groups are no longer an insignificant minority. But is that really the case? The Pritzker Prize and architecture biennials are, of course, mainstream and even hegemonic institutionalized and well-established forms of practices for maintaining distinction in the architectural world. That the topic of decolonization and indigenous modernity has found its way into their focus is, of course, a harbinger of change. Or at least, it is evidence of the recognition of this phenomenon in the world of the Global North. However, this does not come without cost.

It is impossible to ignore the fact that three curators from Ghana, whose works we can view at the Biennale, were not allowed into Europe by officials of the Italian embassy, fearing that they would leave the Biennale and not exit the Schengen zone before their visas expired (Lowe, 2023; Seymour, 2023). While it is possible to see this gesture as nothing more than local politics, as Italy’s ruling party is anti-immigration, it is evidence of the absurdity of a show dedicated to Africa to which Africans were denied entry. Perhaps it is that we are eager to see Africa’ architecture, just not Africans.

I would like to express my gratitude to the Reviewers for their insightful reading and accurate, valuable comments. They have greatly strengthened the text qualitatively. I would also like to thank the Kéré Foundation, which provided illustrations for this publication on 20th April, 2024, under the copyright Francis Kéré, Kéré Architecture GmbH. The usage is limited and free of charge for this project.

Cytowanie

Magdalena Matysek-Imielińska (2024), Francis Kéré: A Spokesperson of African Architecture? Modernism and Decolonization, „Przegląd Socjologii Jakościowej”, t. XX, nr 3, s. 122–141, https://doi.org/10.18778/1733-8069.20.3.06

Aravena Alejandro (2016), Biennale Architettura 2016. Reporting from the Front, https://www.labiennale.org/en/architecture/2016 [accessed: 24.09.2023].

Baratto Romullo (2022), Who Is Diébédo Francis Kéré? 15 Things to Know About the 2022 Pritzker Architecture Laureate, “ArchDaily”, 15.03, https://www.archdaily.com/978508/who-is-diebedo-francis-kere-15-things-to-know-about-the-2022-pritzker-architecture-laureate [accessed: 24.08.2023].

Bauer Catherine (1934), Modern Housing, Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Bauhaus Guest Professor Diébédo Francis Kéré Awarded the 2022 Pritzker Architecture Prize (2022), https://www.uni-weimar.de/en/university/news/bauhausjournal-online/titel/bauhaus-guest-professor-diebedo-francis-kere-awarded-the-2022-pritzker-architecture-prize/ [accessed: 24.08.2023].

Choplin Armelle (2023), Concrete City: Material Flows and Urbanisation in West Africa, Hoboken: Wiley.

ELEMENTAL (2012), Incremental Housing and Participatory Design Manual, Berlin: Hatje Cantz.

Florian Maria-Cristina (2022), Ursula von der Leyen Leyen and Francis Kéré Open the Bauhaus Earth Conference, “ArchDaily”, 13.06, https://www.archdaily.com/983511/ursula-von-der-leyen-and-francis-kere-open-the-bauhaus-earth-conference [accessed: 24.08.2023].

Flyvbjerg Bent (2004), Five Misunderstandings About Case Study Research, [in:] Clive Seale, Giampietro Gobo, Jaber F. Gubrium, David Silverman (eds.), Qualitative Research Practice, London–Thousand Oaks: Sage, pp. 390–404.

Geertz Cliford (1973), Thick description: toward an interpretive theory of culture, [in:] Cliford Geertz, The interpretation of cultures: selected essays, New York: Basic Books, pp. 3–30.

Giedion Sigfried (1985), Befreites Wohnen, Frankfurt: Syndikat.

Gilroy Paul (1993), The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Heynen Hilde (2013), The Intertwinement of Modernism and Colonialism; A Theoretical Perspective Modern Africa, Tropical Architecture, “Docomomo Journal”, vol. 48, pp. 10–19.

Hosagrahar Jyoti (2005), Indigenous modernities: Negotiating architecture, urbanism, and colonialism, New York: Routledge.

Kéré Foundation (n.d.), Architecture, https://www.kerefoundation.com/en/practices/architecture [accessed: 24.08.2023].

Kéré Foundation (n.d.), Collaboration, https://www.kerefoundation.com/en/practices/collaboration [accessed: 24.08.2023].

Kéré Foundation (n.d.), Education, https://www.kerefoundation.com/en/projects/education [accessed: 24.08.2023].

Kéré Foundation, n.d., Resources, https://www.kerefoundation.com/en/practices/resources [accessed: 24.08.2023].

Kéré Francis Diebedo (2012a), How to build with clay and community, TEDCity 2.0 TEDPrize, https://www.ted.com/talks/diebedo_francis_kere_how_to_build_with_clay_and_community [accessed: 24.08.2023].

Kéré Francis Diebedo (2012b), School in Gando, Burkina Faso, “Architectural Design”, vol. 82, pp. 66–71.

Kéré Francis Diebedo (2018), Primary School, Gando, “Arquitectura Viva”, 28.02, https://arquitecturaviva.com/works/escuela-primaria-de-gando-10 [accessed: 24.08.2023].

Le Corbusier (1925/1980), L’Art décorative d’aujourd’hui, Paris: Arthaud.

Lepik Andreas, Beygo Ayça (2016), Francis Kéré: Radically Simple, Berlin: Hatje Cantz.

Lesley Lokko announces theme for Venice Architecture Biennale 2023 as „The Laboratory of the Future” (2022), https://worldarchitecture.org/architecture-news/enzfv/lesley-lokko-announces-theme-for-venice-architecture-biennale-2023-as-the-laboratory-of-the-future-.html [accessed: 24.08.2023].

Lowe Tom (2023), Denied visas for Ghanaian participants sour build up to Africa-themed Biennale, “Building Design”, 12.05, https://www.bdonline.co.uk/news/denied-visas-for-ghanaian-participants-sour-build-up-to-africa-themed-biennale/5123161.article [accessed: 24.08.2023].

Matysek-Imielińska Magdalena (2020), Warsaw Housing Cooperative. City in Action, The Urban Series, Cham: Springer.

New European Bauhaus: Francis Kéré joins high-level roundtable (2022), https://www.arc.ed.tum.de/en/arc/about-us/news/news-single-view-en/article/new-european-bauhaus-francis-kere-joins-the-neb-high-level-roundtable/ [accessed: 24.08.2023].

Oguibe Olu (2004), The Culture Game, Minneapolis, London: University of Minnesota Press.

Rodgers Bill (2014), Architecture. Diébédo Francis Kéré: The Gando Project, https://cfileonline.org/architecture-diebedo-francis-kere-gando-project/ [accessed: 24.08.2023].

Rotbard Sharon (2015), White City, Black City: Architecture and War in Tel Aviv and Jaffa, London: Pluto Press/MIT Press.

Said Edward W. (1979), Orientalism, New York: Vintage Books.

Sennett Richard (2009), The Craftsman, London: Penguin Group.

Seymour Tom (2023), Venice Architecture Biennale curator criticises Italian government for denying visas for three Ghanaian curators, “The Art Newspaper”, 19.05, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2023/05/19/venice-architecture-biennale-curator-criticises-italian-government-for-denying-visas-for-three-ghanian-staff [accessed: 24.08.2023].

Syrkus Helena (1976), Ku idei osiedla społecznego, Warszawa: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe.

The Awards of The Biennale Architettura (2023), https://www.labiennale.org/en/news/awards-biennale-architettura-2023 [accessed: 24.08.2023].

Golden Lion for Best National Participation to Brazil(Terra [Earth])– for a research exhibition and architectural intervention that center the philosophies and imaginaries of indigenous and black population toward modes of reparation.

Special mention as National Participation to Great Britain (Dancing Before the Moon) – for the curatorial strategy and design propositions celebrating the potency of everyday rituals as forms of resistance and spatial practices in diasporic communities.

Golden Lion for the best participant in the 18th Exhibition The Laboratory of the Future to DAAR – Alessandro Petti and Sandi Hila – for their long-standing commitment to deep political engagement with architectural and learning practices of decolonization in Palestine and Europe.

Silver Lion for apromising young participant in the 18th Exhibition The Laboratory of the Future to Olalekan Jeyifous – or a multimedia installation that explores a world-building practice that expands public perspectives and imaginations, offering visions of a decolonized and decarbonized future.

Special mentions to the participants in the 18th Exhibition The Laboratory of the Future to:

Twenty Nine Studio / Sammy Baloji – for a three-part installation that interrogates the past, present, and future of the Democratic Republic of Congo, through an excavation of colonial architectural archives.

Wolff Architects – for an installation that reflects a collaborative and multimodal design practice as well as a nuanced and imaginative approach to resources, research, and representation.

Thandi Loewenson – for a militant research practice that materializes spatial histories of land struggles, extraction, and liberation through the medium of graphite and speculative writing as design tools (The Awards of The Biennale Architettura, 2023).

Furthermore, Nigerian-born artist, designer, and architect Demas Nwoko is also the recipient of the Golden Lion Award for Lifetime Achievement.