https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9534-6463

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9534-6463

Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń, Poland

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9534-6463

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9534-6463

Abstract:

In this article I analyze the actions of the Interdisciplinary Creative Research Center “Pracownia” using the author’s art-based research typology of six moves: downward (two types), upward, inward, along, and across. The paper considers culture animation/community arts to be practices of researching oneself and the world through art. I explain this via the example of “Pracownia” and select one photo of their actions from the years 1978–1981 in order to present every point of the typology. The research aims to fill in the gaps in the history of Polish community arts/culture animation, whilst providing analytical tools for social scientists and practical guidelines for culture animators/community artists

Keywords:

six-moves typology, arts-based research, Interdisciplinary Creative Research Center “Pracownia”, culture animation, community arts

Abstrakt:

W artykule autor analizuje działalność Interdyscyplinarnej Placówki Twórczo-Badawczej „Pracownia”, wykorzystując autorską typologię pomocną w badaniach opartych na sztuce. Jest to typologia sześciu ruchów: w dół (dwa rodzaje), w górę, w głąb, wzdłuż i w poprzek. Uznaje ona praktyki animacji kultury/sztuk społecznych za badanie siebie i świata poprzez sztukę. Autor wyjaśnia to na przykładzie „Pracowni”, wybierając jedno zdjęcie działań placówki z lat 1978–1981, by przedstawić każdy punkt typologii. Celem badań jest wypełnienie luk w historii polskich sztuk społecznych/animacji kultury, dostarczenie narzędzi analitycznych dla badaczy społecznych oraz praktycznych wskazówek dla animatorów kultury/artystów społecznych.

Słowa kluczowe:

typologia sześciu ruchów, badania oparte na sztuce, Interdyscyplinarna Placówka Twórczo-Badawcza „Pracownia”, animacja kultury, sztuki społeczne

In this article, I outline a proposal of typology that might be helpful in designing and verifying the research qualities of different artistic actions. I aim to inscribe my ideas into a research/social turn in arts and place culture animation activities[2] in a slightly different perspective. To do so, I invite the reader to take a look back to the turn of the 1970s and 1980s in northern Poland and explore a pile of old photos that stimulated me to reflect on the concept of the artist as a researcher, a border-art activist that negotiates alternatives within the system in times of crisis. The photos present the unknown stories and unrecognized praxis of one of the earliest groups contributing to this transdisciplinary practice – the Interdisciplinary Creative Research Center “Pracownia”, active in the last decade of communism in Olsztyn.

I assume that historical distance makes my argumentation more visible and unequivocal, and thus more useful. Furthermore, it is rooted in artistic practices as well as in anthropological and sociological theories, expressed through the lens of academia. I consider this vital, because I diagnose an urgent need to systematize the scientific knowledge about culture animation in Poland as well as to write its history in a socio-artistic manner. The location of this reflection in the academic context is also important, because social scientists need to undertake an analysis of culture animation projects as research tools providing data about animation itself but also – and most importantly – about local communities. Only in this way will we develop the field, enrich practices, and avoid poor management of funds for additional research of negligible effectiveness.

When analyzing the photos of “Pracownia”, one can detect more layers than just that of documentation and archiving. A closer look shows them as witnesses of in-depth citizen research activities engaging in dialog with the time, place, and memory; a visual memoir of the critical moment in the Polish culture that may constitute a reference for many past and future crises, and social-artistic reactions to it. In this text, I use visual material as a starting point for reflection on the aims and effects of socially-engaged arts projects as well as their critical and research potential.

Over the course of many months, I examined several folders with photographs that I received from my interlocutors in the project On the way to culture animation. An interdisciplinary research study of the Interdisciplinary Creative Research Center “Pracownia”. The photos fascinated me. They show some of the community arts actions organized by the alternative art group named “Pracownia” (“Workshop”) in the town of Olsztyn and the villages around it in the province of Warmia, a historical area in north-eastern Poland, which till 1945 was part of Eastern Prussia.

The photos show an incomplete portfolio of the group from the years 1978–1981. Two theater performances – Jumping Mouse, played inside in front of an audience of children, and Travels to many distant countries of the world, played outside in the garden of an orphanage and in the gloomy streets of a small Warmian town; winter workshops for high school students in the post-Warmian house in the village of Trękus; a traveling exhibition of large pictures of the painter Tadeusz Piotrowski, presented in the streets of Olsztyn in the summer of 1981; a summer action named Masks for the children from the village of Bęsia with a street mask parade and a spectacular bird puppet in the vivid green field; an ecological-artistic action A dragon from the river around the Łyna river crossing the town of Olsztyn; a street concert in the busy Bem roundabout; and a performance by the group Trumbonich Mimes invited by “Pracownia” to the local high school.

With time, more photos were found in the private archives. I felt great pleasure when they appeared, as there was an element of serendipity in it. Some of the new findings add more visual information to the action already known by me, some of them document actions I only heard of, as Journey Home form 1979, a drift through the abandoned houses of Warmia – making stops in few ruins, painting walls, lighting candles, eating soup; or a colorful street parade from the 1980’s being Olsztyn’s edition of the performance Happy Day by “Pracownia’s” befriended Academy of Movement from Warsaw. Some photos from mid 1980s, e.g., from the Jumping Mouse theater performance were also found in the emerging Węgajty Theater Archive by Magdalena Hasiuk and her research team.

“Pracownia”, as stated in its manifesto from 1977, was primarily divided into four labs: Open, Theory and Publishing, Educational, and Documentation. Ewa Scheliga was in charge of the fourth one, and worked on a company Zenit camera, developing the photos in a darkroom in 15 Okopowa Street. The task of this Laboratory was to prepare and select documentation of the activities of “Pracownia” and activities of other institutions, events, and phenomena that were of interest. The documentation technique depended on the nature of the event and only took place if it did not interfere with the internal structure of the event (Program Pracowni, 1977: III). Sometimes, when Ewa Scheliga was occupied with other organizational duties, or when she was absent, other people took pictures, mostly befriended photographers Krzysztof Wołoczko or Mieczysław Wieliczko.

The majority of the “Pracownia” photographs were merely meant to document the events and were not intended to be independent pieces of art. They are photos documenting from an insider’s perspective the everyday life of the group, equivalent to a countercultural understanding of work: the work-life. Sometimes when viewers and passers-by enter the frame, they show a countercultural view of mainstream social reality and make social differences visible. However, the vector of the us–them opposition is not applied to the individual members of society, but, rather, to the institutions which may not recognize this photography as a documentation of real work (Dobiasz-Krysiak, 2023: 305–306).

Illustration 1. Action Happy Day by the Academy of Movement in Olsztyn with members of “Pracownia”, Olsztyn 1980

Source: Sienkiewicz, 2014.

The intentional lack of a conventional “Pracownia” group photo was justified by the Group Photos action that ironically portrayed stereotypical rituals of photographic conventions. It proves that for “Pracownia” taking photos was not so much an expression of participation in social normality, but, rather, a fight for autonomy, a right for self-presentation and for a place in the collective consciousness (Drozdowski, Krajewski, 2010: 115–117, 124); a place for otherness, or alternatives. This autonomous gesture is described by Drozdowski and Krajewski as doubly independent: “Independent, firstly, of the models of esthetic and workshop correctness […] secondly, of the dominant views and ideas [of 1970s and 1980s in Poland – note M.D.-K.] about what is allowed to be photographed and in which situations one can reach for a camera and in which one cannot” (Drozdowski, Krajewski, 2010: 124–125). Although some of the pictures were taken by photographers that later became professional, most of them display rather amateur qualities. Consequently, I treat the photos as “iconic substitutes of language” that intended to avoid subsequent oral reporting of the events experienced for the needs of the institution (Drozdowski, Krajewski, 2010: 120). They are equal to all the data I gathered and become an element of triangulation – using various types of data to construct the theory (Harper, 2014: 155–156).

There had been a lack of the social circulation of these photos before I started the research. Most had been deposited in the archives of an organization that employed the last members of “Pracownia” and moved to a private archive when they retired, just at the same time when I started the project. They were cut into slides for viewing but had not been reviewed or publicly displayed for a long time. A few photos in the form of prints were kept in the private archive of a person who had moved abroad and had sporadic contact with members of the group before I began my research. All were scanned and put into public circulation because of the research project, which initiated their public dissemination in the media, social media, exchange between the members, and even the recognition of some of them. The photos of the Olsztyn-based performance of the Academy of Movement Happy Day circulated in the media, but not as one of “Pracownia’s” actions. My coworker recognized people in the picture and sent it to me because of my interest as a researcher.

The photographed actions are different, the authors and the quality of photos vary, but their common denominator is that they were all taken in spaces that we would today call public, although taken in times verging on crises: in the Polish Peoples Republic, during the 1970s recession, in the “Carnival of Solidarity”, and on the eve of introducing martial law (13th December, 1981 – 22nd July, 1983), and then the notion of public and private was more than problematic. This was interpreted by sociologist Elżbieta Matynia as the fluctuating dialectics of the official (that annexed the public sphere) and the unofficial (that covered the private and semi-private e.g., dissident sphere) (Matynia, 2008: 26). “Pracownia’s” actions played outside the conventional scene or the safe workshop space were there to expand the area of the “unofficial” into the realm of the “official” and to elaborate on the idea of the public character of those outside spaces.

Illustration 2. Music on Bem’s Roundabout in Olsztyn 1978

Source: Photo by Ewa Scheliga.

The dissident interpretation of the group’s aims is alluring, because it fits perfectly in the heroic narrative that sets the actions in the ethical context of opposing communism (Banasiak, 2020: 25–26). The story is, however, more complex and less black and white when we take a look at “Pracownia’s” formal location and its fate after 1982, which is less documented, sometimes forgotten, and, interestingly, hardly photographed.

The “Pracownia” Interdisciplinary Creative Research Center comprised a group of art historians, anthropologists, and artists[3] that operated in Olsztyn from 1977 as part of the “Pojezierze” Social and Cultural Association – a Warmian-Masurian association organizing local cultural life, publishing books and magazines, taking care of cultural heritage, and connecting creatives and social activists, being, however, under constant socialist party control (Sikorski, 1995: 87). The group was an alternative art movement of the turn of the 1970/1980s and is considered a part of the broadly understood third theater, although they did not always work theatrically. “Pracownia” maintained contacts with most of the significant groups of that period, including the Grotowski’s Laboratory Theater, the Academy of Movement from Warsaw, Gardzienice, etc. On its initiative, many groups visited Olsztyn, e.g., The Living Theater, Quatro Tablas, the Solvognen Theater from Christiania, and many more. The group was studied and befriended by humanistic sociologists who gathered around Prof. Andrzej Siciński from the Institute of Philosophy and Sociology of the Polish Academy of Sciences, who researched alternative ways of life, and were members of its program council. Despite this, the group has not received a monograph or a thorough analysis of its work. In order to get to know the specificity of “Pracownia”, I conducted ethnographic research in the form of: free interviews with its members and supporters[4], library queries, and searches in private and state archives. I also gathered and analyzed visual materials, photos, posters, invitations, or leaflets.

The members of “Pracownia” were educated in significant academic centers such as Warsaw, Wrocław, and Toruń, and came back to – or arrived at – the distant province mostly for professional reasons. Their trajectory fits into the tradition of many intellectuals and specialists filling the ranks of the intelligentsia of this land since its incorporation to Poland after World War II, connecting it with the center by their contacts and friendships. Warmia functioned in the official propaganda under the name “reclaimed land”, and in the 1970s and 1980s the displacement and migration processes known as the second family reunification action were still taking place there. As a result of these post-war forced displacements and emigration, most of the inhabitants – both Germans and Warmians – left Warmia, leaving their houses to the Polish state. There was, thus, a great exchange of population – the vast majority of newcomers were the inhabitants of the former borderlands, Mazovia, or displaced Ukrainians.

At first, “Pracownia” was meant to be a youth club, so its character was more workshop-oriented and closer to community arts/culture animation. In 1980, under the inspiration of third-theater groups and driven by the wind of Solidarity changes in the country, they published their second manifesto, titled the Geography of action, and started (at least partially) to evolve into a theater-oriented group (Kurowski, 1980). The activity of the Interdisciplinary Creative Research Center “Pracownia”, whose name already suggests its research location, was inspired by contemporary artistic trends (such as conceptualism, situationism, Fluxus, paratheatre, and counterculture), but was also immersed in intellectual practices (e.g., the anthropology of culture, the anthropology of theater, humanistic sociology, history of art, new regionalism) and was characterized by a turn toward social activity.

In March 1982, during martial law, “Pracownia” was dissolved by the party-oriented authorities of the “Pojezierze” Association via various unproven accusations (artistic immaturity, drug addiction, hooliganism, rumors of their political involvement). However, only three months later, in May 1982, owing to the acquaintances and connections of the members of “Pracownia”, it was reorganized under the name the “Pracownia” Center for Theater Activities within the Provincial Cultural Center in Olsztyn (WDK, later CEiIK), and the members were employed there full time as theater instructors whilst receiving monthly salaries.

Despite the crisis of 1982, the heroic narrative of freedom fighters in the totalitarian system is insufficient to understand “Pracownia”. A crack in the ethical paradigm appears, as the group did not function as a bottom-up creative association but was searching for alternative ways of fitting within the communist system – marching through institutions or creating “the third place”[5]. Moreover, in 1982, they did not boycott the state-owned system of art and culture but found their place within the official structures. Their life in the years 1982–1986 was far from comfortable, as some were forced to do military service and others fled the army by faking mental problems. The years of the martial law were tough, although, contrary to stories of stagnation (that support the heroic narrative, with boycotting any state-organized culture), archival documents confirm that “Pracownia” quickly reactivated creative activities. Early in 1982, they found an old house in Węgajty and started to arrange a barn for their training studio (Sobaszek, 2020: 21). In July, Wacław Sobaszek, Krzysztof Gedroyć, Maria Jenny Burniewicz, and Waldemar Piekarski conducted workshops The Way of the Theater [Pol. Droga teatru] (Sobaszek, 2020: 21); the group played Jumping Mouse in the region eight times from September to December 1982. In the second half of 1982, they were already traveling to their artistic friends in the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Germany, giving workshops and showing their performances, and they even managed to invite some western groups to Olsztyn. Between 1982–1986, they were also working on interesting inner projects in various cooperations: Exercises in Perceiving Movement and Oneself by Ryszard Michalski and Wacław Sobaszek; Vacuum Project and Vehicle Theater by Wacław Sobaszek and El Sur Theatre, the Voice Studio by Krzysztof Gedroyć, Ewa Scheliga, and Maria Jenny Burniewicz, and different theater and music initiatives for children and young adults by Maria Jenny Burniewicz. My collection of photos does not quite cover this period, as if all the activity after the introduction of martial law was meant to be invisible. The exception was events for children. Some pictures of children, dancers, and musicians accompany an article that was published on children theater workshops by Maria Jenny Burniewicz (Sobaszek, 1983). The other notable exception was mask performance Jumping Mouse, a photo of which was published by Wacław Sobaszek in Life Conspiracies [Pol. Spiski życiowe]. However, actors and children sitting on the threshold of the Węgajty barn are wearing animal masks – as if the activities taking place in the country at that time had to be “masked”, “conspired” (Sobaszek, 2020: 26–28), or even infantilized, so that they escape the eye of censorship.

Jakub Banasiak, who researches the disintegration of the state art system in Poland in the years 1982–1993, showed that the year 1986 was an unrecognized caesura marking the artistic “second thaw”. His analysis of post-martial law exhibitions of new art shows that around 1986, young artists decided to break the boycott and present their work, confront the public, get the attention of critics, and get their life together (Banasiak, 2020: 44). The year 1986 was also a clear turn in “Pracownia”s history, since they visibly started to disintegrate – the Węgajty Theater was organized in the distant Warmian village and the people working in Olsztyn in the Provincial Cultural Center were also turning from the artistic group into a loosely connected body of theater instructors, each one leading his/her own project, and sparsely cooperating. Ewa Scheliga and Maria Jenny Burniewicz both had gone abroad in 1986 and in the timeframe of “second thaw” were active in Olsztyn only in short periods of their return.

Even though the group split, the name “Pracownia” remained formally till the end of 1992 – the year of reorganization of the Provincial Cultural Center in Olsztyn – and then disappeared from documents. Similarly, Jakub Banasiak marks 1993 as the end date for the old state art system. In his perspective, the new periodization, including 1986 and 1993, makes the art history social, not political, which causes the researchers’ attachment to the turn of 1989. My research on “Pracownia” fits into Banasiak’s recognitions and supports the “bottom-up” perspective on human agency and the system:

[…] society is causative not only at the level of opposition to communism, but also at the level of its co-creation: constant renegotiation of its framework, influencing the shape of individual solutions, or even initiating them. Adopting a social perspective makes us rethink the issue of the attitude toward communism of both individuals and the communities functioning within it. (Banasiak, 2020: 31)

This historical and organizational background helps to situate “Pracownia” in the context of social movements in the late People’s Republic of Poland. The group was an alternative movement rather than an avantgarde one. The alternative involves the adoption of an either-or option. Alternativists do not seek to overthrow or completely change the system, but to find a “cultural niche” within a functioning system where they can pursue their goals. The culture they create is often complementary. Tadeusz Paleczny notes that they often use expressions “next to” or “instead of”. Their social status is also usually defined – they are creators, artists, writers, scientists. As the sociologist writes, “the status of this category is related to creative searches, striving for innovation, development and progress” (Paleczny, 2010: 75). The avantgardists, on the other hand, tend to violate the existing worldviews and canons – they are “breakers” of conventions and contestants of the existing values (Paleczny, 2010: 80). “Pracownia” – although not averse to subversion, irony, or even direct criticism of the system, e.g., working conditions – was rather looking for a space in between that would enable acting in the current world and expanding the dialogical public sphere. Next to the attempts at creating better worlds, they also used the weapon of the weak (Scott, 1990: XVI), practices of relatively powerless groups, who use tactics, not strategies as understood by de Certeau (2008): slowing down the process, sabotaging orders, etc., whilst maintaining a fairly high level of autonomy (Kuligowski, 2012: 36).

To better understand the practices depicted in the photos of “Pracownia”, it is worth putting them together with another photographic project I read about in an article by Marta Smolińska. The artist and curator wrote about East Side Story, a photographic endeavor of Anne Peschken and Mark Pisarksy. They used old photos of families that arrived at Myślibórz after WWII, to remake them using camera obscura techniques and work with the social memory of migration. The town is situated in the “recovered territories” on the west of today’s Poland, and until 1945 was within the borders of Germany under the name Soldin. The subject of the photos concerned settling in the regained territories – painting over old inscriptions in German, occupying post-German houses, sowing fields, harvesting, walking around the city with a stroller, posing in the yard of a newly occupied house, etc. The author interprets them after Anne Ring Petersen as photos confirming the new identity, belonging, visibility, and recognition. Appearing in the public sphere, she writes, quoting Arendt, that “it gives a person a sense of reality, that’s why the newcomers needed to take photos and create the gallery of their own, inner images” (Smolińska, 2022: 96, 97).

My collection of photographs of “Pracownia” displays many similar features, but simultaneously shows meaningful differences. Both collections of the pictures were taken in the times of the Polish People’s Republic in the “recovered territories”[6], and both present life practices in relation to the land and the existing cultural landscape. The East Side Story pictures document the moment of transition, change, discontinuity in the life of families subjected to historical politics, and a striving to regain their identity – also by producing its visual representations – picturing this process. “Pracownia’s” pictures document the ephemeral street actions, workshops, and performances of an art group. Documentation was needed to confirm their existence to the employer, the public (and the befriended sociologists that formed “Pracownia’s” program council) to build the portfolio and archives of the group. Documentation also sanctioned their artistic status in relation to other photos of art groups they knew as the Academy of Movement, and to establish their place in the art world. In this meaning, the photographs confirm and sanction their existence in the spirit of the old photos used in the East Side Story. It is about making things real, also when it comes to Arend’s “appearing in the public space”.

The difference in not in the artistic and non-artistic character of the photographed events. Both migrants to Myślibórz and the members of “Pracownia” perform, show something, play the role in the new land. The main difference is, however, in what the characters perform in the public sphere. The first group play the role of settlers that make the space of the abandoned house a home again. They re-privatize it. When they harvest the fields, pose in the porch, and drink vodka, they perform rituals of habitation through the practices of everyday life. The members of “Pracownia” do something completely different – they walk or play in the street. They visit abandoned houses and occupy them temporarily, as in a Journey Home action. They take the role of drifters, vagabonds, travelers, street actors, researchers. They perform rituals of othering and dialoging through art. They negotiate with the land, do not tame it in order to get used to it, to banish the German spirits, and to make it familiar. Rather, they ask the land questions of its compound identity in order to understand it and for the time (lifetime?) being, reside in a haunted house or land that we own only awhile, and to make deals with its ghosts. This type of home is not simply re-privatized but, rather, re-publicized: meaning open, common, and unofficial. This makes it close to Matynia’s sense of public sphere that is supposed to be an independent, democratic space of exchange. “Pracownia” being outside (on the road, in the street) might be interpreted as a symbolic action for the sake of regaining visibility, taking over control in the moment of crisis, and visually communicating with the natural audience in the public, spreading the idea of alternative ways of working with memory.

Illustrations 3, 4. Part of the Młyn (“The Mill”) action named Journey Home, April 27/28, 1979

Source: Photo by Ewa Scheliga.

Francis Gross writes in the Philosophy of Walking that wandering reverses the division between what is “outside” and what is “inside”. Gross shows that the wayfarer does not cross the land to stay in shelters but, rather, inhabits a landscape for many days and slowly comes into possession of it, makes it his/her home (Gross, 2021: 38). “Pracownia’s” walking is, in my interpretation, close to inhabiting the landscape, slowly getting acquainted with it by being in it and picturing oneself in it; its inscribing oneself in the land, making it feel like home. This does not cancel, however, their dreams of the “home”; rather, it creates a different, alternative one, joining the categories of the private and the public – an art community. First, the members of “Pracownia” made their basement in the headquarters in the “Pojezierze” building, open to young people who were hanging out there after school, drinking strong tea, smoking cigarettes, and presenting their art. They also visited Warmian houses occupied by their friends in Trękus and Plutki, and organized several-day creative workshops for young people. Then members of “Pracownia” were searching for an old house where they could work and live together in a commune. The idea of commune was quickly rejected and, finally, in 1982, they found a house in the Węgajty village, and turned a barn into a theater. The space was, however, difficult to share, and shortly after in 1986 they disconnected. The introduction of martial law was the moment they took the role of the settlers. It changed their condition forever – from the group present in the landscape, to castaways perched on the outskirts of reality.

The cultural semantics of being on the road, with its liminal character, does not include only walking in the wilderness. Roch Sulima analyzes the cultural landscape of the city and notes that the phenomenon that renews the original meaning of the street, and its cultural memory, is the demonstration. The demonstration as a spectacle “refers to the semantics of the road, the symbolism of peregrination, collective movement (march, procession), refers to ritual and religious forms (pilgrimage, etc.)” (Sulima, 2022: 327). Sulima calls demonstration, a street experience of being present – intentionally being in sight – regaining “the right to look” (after Nicolas Mirzoeff), creating countervisibility, demanding perceptual equality that guarantees political equality (Sulima, 2022: 297).

The street is a space of rituals that are revitalized in the times of great trauma, crisis, or a change, being a notion of symbolic representations of the social order. Many actions of “Pracownia” were in the form of a street parade (Masks in Bęsia – 1979, Tadeusz Piotrowski’s walking exhibition – 1981) or street performance (Travels to many Distant Countries of the World – 1980, A Dragon from the River – 1980, Music in the Bem Roundabout – 1978), taking place in urban space, for a random urban audience. Their dramaturgic form was so efficient that they did not require using words different from slogans similar to banners such as “Help River Łyna – do what you can” or “The earth does not belong to man, man belongs to the earth” – tag lines from the ecological action A Dragon from the River. Many of those street events took place in 1980, a year of carnival of Solidarity that Sulima considers crucial for the Polish reception of street demonstrations, when the audience became more competent in reading the symbolic imagination and experiencing the visuality of it (Sulima, 2022: 299). “Pracownia’s” street presence of 1980 has to be interpreted in light of the Solidarity strikes, inscribing itself in the poetics of protest. This is – in my opinion – also the clue of the lack of the visibility of “Pracownia” on the street and in photos after 1982. The introduction of martial law put an end to the street presence of demonstrators, and military forces took control of the street for the time being. “Pracownia” chose a rural hideaway and foreign getaways, and had to give up their street/landscape presence in order to outlast the crisis.

“Only in the road, only on paths, only on trails, we are not here”, as Gross writes (2021: 54). Being not here might mean also staying in the border-like state of mind. Sulima recalls the liminal character of the road, “a space where God intervenes, but also the devil/evil lurks, where truth, justice, community can be present, where the »guest« and »strangers« appear, where the rituals of greetings and farewells – confirming the bonds of community – intensify” (Sulima, 2022: 323). The notion of border is very meaningful for my interpretation, especially if the border is a phantom, or a movable one; once political, not natural, ethnic, or social, and having significant consequences for people, culture, and the holistic development of the land.

Photos of “Pracownia” – as well as photos used in the East Side Story project – constitute an example of border art dealing with issues such as border status, surveillance, nationality, migration, identity, etc. “Pracownia’s” actions such as Journey Home, Winter Actions, Workshop in Trękus, and Workshop of Music and Poetry all took place in abandoned Warmian houses and concerned the effects of migration on the land and the people. Group Pictures critically presented the stereotypical social interactions and masks, and negated them through their dramatized visualization. Playing with Straw in the Gallery was a subversive happening organized for the Central Harvest Festival Olsztyn of 1978. In the narrative of the socialist government, the festival should have confirmed the efficiency of the state. “Pracownia” challenged the surveillance and took two carts of hay to the art gallery, and immersed itself in it unproductively all day long. Smolińska writes that:

[…] key categories related to border art is creating alternative narratives to the officially binding ones. Therefore, it is a socially engaged and relational art, and the artist’s work on the borderline like critical researchers who redefine aesthetic regimes, treating vernacular photography as a lens through which important historical, socio-political conditions are negotiated, and through which strategies of self-representation and negotiating the identity of newcomers are constructed. (Smolińska, 2022: 99)

Elżbieta Matynia’s concept of “living through theater” from the 1980s – which she derives from her fieldwork on “Pracownia” and alternative theaters in 1980s – also focuses on research qualities:

Another important – and hardly noticed – feature of what I term “living through theater” is its orientation toward research. More precisely, it means tackling problems traditionally reserved for the broadly conceived social sciences – sociology and social psychology, ethnography, cultural anthropology, and ethics. It means a kind of exploratory approach to the world. The creative process displays some similarities with the research process. Creation is here an important means of learning. (Matynia, 1983: 140)

This concept of a border artist/animator as a researcher is very fruitful for my work. As Susan Finley writes, “art-making activities can be used to expose and critique current events […] as a democratic form of practice that enables a critical examination of visual cultural codes and ideologies to resist social injustice” (Finley, 2018: 562). She calls it “critical citizenship” and “cultural democracy,” because “critical arts-based researchers perform inquiry that is cutting edge and seeks to perform and inspire socially just, emancipatory, and transformative political acts” (Finley, 2018: 562). I argue that the activity of the “Pracownia” Interdisciplinary Creative Research Center that I present through the choice of photos shows these features. That is why I consider them one of the precursors shaping the Polish school of culture animation/community arts, but also art-based research.

In the Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, Finley and Denzin stress that there is a constant need, and even an urgency, to create and develop such horizontal, inclusive, non-conservative, “alternative” methodologies. (Finley, 2018). My proposal of typology is an introduction to addressing this demand, based on the assumption that deepened, reflective culture animation might be a Polish answer to action research, or critical art-based research. Its research inclination is also included in “Pracownia’s” full name – the Interdisciplinary Creative Research Center – as well as in its early animation and artistic practices that prove to be research-oriented reflective endeavors.

This is mostly shown in “Pracownia’s” writings. My in-depth research in “Pracownia” archives shows a large number of notes, reflective reports, descriptions, analyses, and proposals for research criteria, made for the sake of the group or for the purposes of publication (Interdyscyplinarna…, 1981/1982). I obtained files from the archive of Krzysztof Gedroyć that contains very dense, handwritten notes on small postcards, grouped into files regarding voice and body exercises, and analyses of sound production methods. There is a record of independent work, called “individual work”, as well as group work, especially exchanges with Ewa Scheliga and Maria Jenny Burniewicz, with whom he run the Voice Studio. As the file labels inform: “here are important general issues”, “text and language issues”, “verbs, movement in the text”. One can also find traces of the author’s intellectual inspirations: Grotowski, Gombrowicz, “Confessions” of St. Augustine, Merleau-Ponty and phenomenology, Husserl and Heidegger.

Gedroyć’s archive confirms the research and development dimension of this work. It is a reflection that results directly from action or reading; a detailed, methodical action. The notes give the impression of field notes, i.e., immediately made right after the experience. Nevertheless, they were later described, organized, and kept until his death as documentation of this action research.

As Maria Jenny Burniewicz recalls about her work in the Voice Studio, practical actions were deeply analyzed there. After every exercise, there were long hours of discussions, and they were described and interpreted in a “conscious” way (P_MB_K_65_MDK_2022). Bodily and vocal practices – as well as all the other art-based media they used – were treated as research and cognitive tools, and the research techniques such as note-taking, discussing, making typologies, filing, archiving, writing, and publishing were an immediate creative and research process.

Interpreting the street demonstrations in reaction to major trauma (such as the introduction of martial law), Roch Sulima names them “rituals of withdrawal” – voluntary and spontaneous commitment to the transparent, universal, sanctioned tradition, symbolic orders, and the rules of the ritual process (Sulima, 2022: 285). He names them moments of stagnation, “simulated life”, in opposition to his “rituals of success”. However, the other understanding of the same rituals might be different – moments of incubation, having a positive impact on overworking the critical situation, closer to Victor Turner’s interpretation of the ritual process that, when done correctly, is unyieldingly effective (Turner, 2005). Withdrawal and success are contradictory movements: backwards and forwards, regress and progress. To nuance this simple dichotomy of crisis and prosperity, I propose a typology of six different moves that may deepen the understanding of community arts activities.

Following the advice of Richard Sennet, who points out that the real cooperation between people requires dialog instead of dialectics – distanced empathy instead of emotional sympathy and indirectness (Sennet, 2013: 33–39) – I distinguish six-point typology that I call ‘six movements on the map of culture animation as research’. They might be treated as six ways of problematizing the sociocultural tissue through creative tools to free oneself from the dialectic dichotomy of right and wrong. I call them “rituals of dialog” with the research field. They also form a “packet” of techniques that enable different ways of dealing with problems when one method is insufficient (Sennet, 2013: 264). The artistic coating makes them indirect. This is important, because it fosters empathy needed to act in the spirit of Sennet’s secular rituals of cooperation, creation, and reparation (Sennet, 2013: 259–285). They are “rituals of dialog” that foster the collaboration and open new perspectives, broaden the horizons, and show the research field in a completely new light. This is why I consider them tools for critical thinking, deritualizing the dialectic thinking and searching for alternatives. I understand the research value of community arts/culture animation actions mostly through their potential of asking questions and provoking alternative answers to expand the public sphere and support communities.

In the chapters below, I outline a typology consisting of six moves. I show its potential based on the events portrayed in the photographs of the “Pracownia” Interdisciplinary Creative Research Center that I have previously described. The typology was built on the basis of the analysis of materials about “Pracownia”, including interviews, articles, archives, and photographs that I used for triangulation. I grouped the latter not only according to the key related to the event they represent, but also in relation to subsequent points of typology emerging from the material. The selection of photographs presented here is both a starting point for creating a given category as well as its exemplification and visual validation.

I first proposed this distinction in the article titled “Towards an Open Methodology: Culture Animation as Research. The Case of the Activities of »Pracownia« from Olsztyn” (Dobiasz-Krysiak, 2022), and this text is an attempt to clarify, simplify, and concretize my proposal so that it becomes more and more operational and unambiguous. I intend to show how to use the typology to interpret and analyze the community arts actions. To do so, I use the example of “Pracownia” and select one photo of their actions to present every point of the typology: a ritual of othering, dialog, or method of citizen research.

The first move is the degrading downward movement. It has two dimensions. Firstly, it means being open to action in crisis areas. Secondly, it indicates readiness for “dirtying the senses”, i.e., subversive, critical, political action. Then, there is an upward movement: uplifting, building koinopolitical communities of local thought. Another aspect is the movement inward – a journey into oneself. The last of the types of movement is moving along and across. The longitudinal research movement follows, discovers, and embodies geography. Lateral movement treads new paths and produces readiness to cross, modify, and dismantle the map.

To move down means to search on the margins of culture. The one who is performing a downward movement is researching areas degraded and marginalized. The areas that are “in the backyard” of the official, hidden, suppressed, unrepresentative. One can learn a lot about the dominant culture by going through its refuse, looking on the back side, and asking questions of why some elements are pushed aside and not discussed. Recognizing and finding the “dirt” is the most crucial aspect of the move downward. It does not require much more than just a diagnosis and disclosure – saying it out loud, making it visual, present. Rather, it requires determination to work with the “dirt”; it is an act of courage. However, it is a necessity. There is no hope for alternatives without revealing what the underlying issue of the cultural obviousness is.

Illustration 5. Part of The Mill action Journey Home, April 27/28, 1979

Source: Photo by Ewa Scheliga.

The photos of “Pracownia” that helped me formulate the idea of the move downward are pictures from Ewa Scheligas and Krzysztof Łepkowskis’s action Journey Home from 1979. They invited local youths to a long walk around the villages of Nowe Włóki, Plutki, Kabikiejmy, and Sętal, which ended with a bonfire and a shared meal. The event was organized with minimal artistic and esthetic interference. During the research reconnaissance, Ewa and Krzysztof leaned about the houses, made some drawings on the walls picturing things that are gone (a dog, a person, a stroller), and decorated the last visited house with some colorful tissue paper, candles, and blankets. “Pracownia” mapped the area with paper flags, cleaned the final house and lit the stove, and then cooked a meal for everyone. They also wrote on the wall lyrics from the song of The Theater of the Eight Day: “This is our home” (Materiały…, 1980): “This is a house / this is our home / radiant, eternal haven / from the rainbow of dreams paradise, shelter / a dead house – so safe”[7]. By doing it, “Pracownia” raised important social topics, such as the situation of lands and houses left behind due to forced migrations. They enabled young people from the city to physically experience the subject of uncomfortable memory, difficult politics – undiscussed in schools and passed over in silence at home. They also problematized a notion of home – private though public; safe but turned into a ruin threatening security; raped; abandoned.

Warmian families left the area in two waves of migration, so the population of the villages drastically decreased in a short period of time. The houses were quickly plundered by looters and left in a bad shape. There were no media and no lakes, which are considered a proof of the value of the landscape, and the villages are till now poorly connected with the larger centers, so the very act of getting there was hedged with hardships, wading in the mud, in the dirt. These were some of the reasons why there were no new settlers, and the houses were found by the members of “Pracownia” in 1978, having been destroyed. Some of them were turned into flats for employees of nearby state farms (PGR, SKR Gradki) and communal apartments for the poorest families. People say that, apparently, today the commune does not want to divide this area into plots, since it hopes to sell the whole for large investments (PO_AZ/AW_K_25_MDK_2023).

The idea of a “move downward” is still a very inspiring one. It opens up a lot of questions concerning the status of this land in the era of pathological developers fighting for every piece of land in this tourist-oriented area. Visiting the non-existent places is also a liminal experience dealing with the subject of social memory and questioning the primacy of humans in the Anthropocene.

In April 2023, we went to Plutki with a group of my ten cooperators, my daughter, and two of my students for the project titled Open Workshop [Pol. Pracownia Otwarta]. We were searching for a home in which “Pracownia” had been working in 1978. Although we had the best guide – Maciej Łepkowski, a cooperator of “Pracownia” and former inhabitant of Plutki – we spent a lot of time attempting to identify the remnants of this house, which had been the biggest one in the village. Later in July 2023, my cooperator Pola Rożek tried to find more houses from the Journey Home action, which were only afterimages of the existing buildings. She compared the stories and written accounts, put it together with pre-war maps and satellite views, and went there. She recalled afterwards:

I decided to check if I would be able to walk this way, if I would be able to track down these pre-war houses and check – what was left of them? I compared the pre-war topographic map with a modern satellite map – I marked on Google Maps potential places of former houses, comparing the topographic layout, almost invisible traces of old roads and tufts of greenery visible on the satellite map. […] In this way, I managed to reach 4 sites of old houses. I noticed the first house when approaching Plutki – I was struck by a cluster of trees different from the others. After a while, among the greenery, I saw stones, fragments of foundations and old walls. The place matched it on the map. I went inside. In the ruins I met a vineyard snail and a frog – new inhabitants.

I had to get to the next house by walking along a hardly visible path in the forest, and then in the meadow. Raspberry, larch, and linden trees helped to locate the second house. And a slight elevation covered with greenery and earth. Somewhere between the barely visible stones-fragments of the wall.

The third house turned out to be unreachable. Neither the road from the pre-war map, nor the road visible on the satellite map could help – it was thickly overgrown with bushes. I had to walk home from the back, via a different path. Eventually, a path trodden by animals led me to the place. A dense grove, on a raised platform, with no visible traces of the old house. Among the trees – a roe deer’s lair.

The pre-war road to the fourth house was guarded by a young spruce forest. I tried to force my way through, but it was a dense and prickly maze, and I gave up. Analyzing the satellite map, I found that this is another house that I had to get to from the back, using a different way, through the meadow. The site of the house was immediately visible, distinguished by a raised area, clusters of trees and raspberries among the evenly mowed meadow. The only tangible trace I found was a brick embedded in a tree. I took a piece with me. (PO_PR_K_40_MDK_2023)

Pola Rożek made a Google Map where she marked the locations of the non-houses she visited. What status does the map have today? For whom is it created? It is surely a post-urbex practice, since (as a passer-by said when asked by my co-workers looking for a way to Plutki) “there is nothing there”. It turned out that some of the members and friends of “Pracownia” still search for the old houses, or shrines. Ewa Scheliga advised Pola Rożek that one can recognize the non-existing house from the plants – e.g., raspberries (PO_PR_K_40_MDK_2023). Mieczysław Wieliczko – a photographer who took some of “Pracownia” photos – told me how he traces old Warmian shrines to take a photo, and sometimes has to drive kilometers in reverse gear, because there is no road back (P_MW_M_65_MDK_2023). I consider these practices of walking (driving) to these distant places similar to visiting cemeteries, and practicing memory of the place, landscape, and people – a “memory-place”.

Maria Mendel and Wiesław Theiss have developed this helpful category of memory-places, reworking the division of “memory sensitive to place” and “a place sensitive to memory”. They write that “memory is, therefore, a place, in particular a place in present reality, in which the subject processes the past, making it something that is part of today” (Mendel, Theiss, 2019: 32). It is a “third space,” a real fragment of the human world emergent at the interface of the past and the present (Mendel, Theiss, 2019: 39) As I understand it, it may be a place in space, in mind, or in the body.

The interlocutor of my students Agata Zamorowska and Agnieszka Teodora Walawska, whom they met in Plutki in August 2023, showed them with his hands where the non-existing houses had been located in space, mentioning specific names of the families who had left (PO_AZ/AW_K_25_MDK_2023). His practice of working with the memory by drawing in the air with his body a map of the past village recalls the theories of embodied knowledge. The non-existing landscape was embodied in the moves of his hands, and he was the only remaining reservoir of the memory of proxemics of the place. He was a map himself.

These are only some possible implications of making a move downward, and its meaning for community arts/culture animation practices understood as a method of research.

The second aspect of the move downward is stressed here to focus on its subversive potential. It is about not only discovering the “dirt”, but also showing it in public. The second movement downward unmasks and undermines cultural mechanisms. It is an opposition to the exclusive and elitist culture, which removes from sight everything that does not meet its conventional expectations. It is exposed via a purely visual culture of appearances. It also reminds us that we are, in truth, a society of spectacle (Sulima, 2022: 293).

“Pracownia” – just like the Situationist International – tried to arrange events that would reveal the superficiality and complexity of cultural experiences. The photos that perfectly illustrate the subversive nature of the second movement downward document the ecological action titled A Dragon from the River, directed by Krzysztof Gedroyć in 1980. The action was versatile and dramatized, although its central figure was a dragon on wheels, built by the members of “Pracownia” out of garbage they might have fished out from the Łyna river, which flows through Olsztyn. The dragon – a very symbolic figure of threat and protection – was carried around the streets of the Old Town and in the River Park at the usual time for walks on Sunday afternoon. The dragon had a baby doll in a gas mask in the front, and cans and plastic bags on its arms. From the pipes on its back, clouds of smoke were expelled (Interdyscyplinarna…, 1981/1982: 71). Things that were supposed to be thrown away, hidden in the waters of the river that turned into a sewer, were brought into public view, disclosed, manifested. The subversive action caused cultural interception (détournement by the Situationists) (Debord, Wolman, 1956) in the spirit of performative democracy on the line of official-unofficial/public-private (Matynia, 2008). The “private” and peripheral garbage appeared in the “official” and central public place, and temporarily disturbed the existing order. The second move downward recognizes the value of what Tadeusz Kantor called “the reality of the lowest rank”, i.e., the poorest places and rejected objects, devoid of prestige, which can reveal their meaning precisely through art (Kantor, 2000: 238–241). The elevation of the low (the garbage) to the highest status by artists is a carnival reversal of the official and makes room for the unofficial, then public.

Illustration 6. “Dragon from the river”, 1980

Source: Photo from the private archive of Andrzej Sakson, re-photographed by Martyna Siudak.

Illustration 7. “Dragon from the river”, 1980

Source: Photo from the private archive of Wiktor Marek Leyk.

The year 1980 – a very civic date in the Polish history – marks the beginning of conscious interest in ecology for “Pracownia”. As a result of the meeting with journalist Juliusz Grodziński, who raised the subject of the impending climate catastrophe during “Pracownia’s” cycle Open Study of Culture, the Ecological Section was established at “Pojezierze”. “Pracownia” organized two street art actions – A Dragon from the River and There Was a Tree – which drew attention to uncontrolled felling of trees in the city. The activities of the Section and the pressure on politicians turned out to be effective, leading to the withdrawal of the city authorities from the implementation of plans to concrete the banks of the Łyna river in the city (Sprawozdanie…, 1978–1980: 31). The citizen research empowered by artistic form made a real contribution to the expansion of the public sphere.

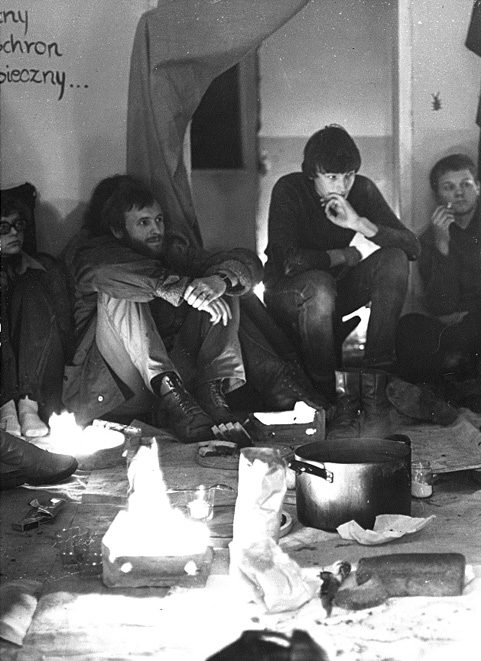

The next move on the typology map is a movement upward. The photo that helped me to conceptualize this point is the one picturing a group of young people sitting together in a small basement room in the first headquarters of “Pracownia”, i.e., at 15 Okopowa Street in Olsztyn. It is the so-called Tower [Pol. Baszta] building, where on the higher floors, the offices of “Pojezierze” were situated. They read Marcel Mauss’ Techniques of the Body and tried to eat pudding with their fingers. The situation was a part of a cycle of meetings called Readings, when different anthropological, sociological books with some practical elements to it were read – e.g., drawing or experimenting with the ideas in the text. The photo that I found in the State Archive in Olsztyn is the only one in my collection showing their activities inside of this building. I greatly value it, since it shows what Krzysztof Łepkowski called “domowisko” (a neologism that might be translated “a home-ing”), understood as “a place where something begins. A place that pushes you forward, upward” (Łepkowski, Wyka, 1983: 310). This is a place that joins the private and the public, another interception (detournement), a place stolen from the “official”. Creating such places, or situations that connect people, is a practice of – using the category of Maria Mendel – establishing koinopolis, i.e., a community of local thought. As Mendel writes, the common place is pedagogical; it shows the ability to teach and learn. It is a place “which is an active and unlimitedly creative, self-producing thought ‘from here’, common and local” (Mendel, 2017: 72). This somewhat rhymes with the thought of Tim Ingold, permeated with the idea of lines and weaves, who writes after Heidegger that “a thing originally did not mean an object, but a cluster, specifically interconnected threads of life” (Ingold, 2018: 91). Thus, “a home-ing” can be understood as a weave of lifelines of different people, times, biographies, experiences. Owing to accumulation and concentration, it gives the strength to act, to create, to start from the beginning.

The second manifesto of “Pracownia” from 1980, titled The Geography of Action, is full of koinopolitical thinking. It emphasizes the importance of acting locally – “in place”. It is it that is supposed to be the nursery of the “living culture” which, by its very nature, is not capable of losing touch with the place in the physical sense: the village, the city, the university, the backyard (Interdyscyplinarna…, 1981/1982: 64–65). “Pracownia” also emphasizes the transgressive, creative nature of such communities as well as their natural inclination to fill in the gaps, articulate their cultural needs and practices – to transcend what has already existed and create their own culture. Common and pedagogical places are, therefore, rooted in an urban community capable of further self-creation. This self-transcendence, this “upward movement”, which can only be done “in place”, but never alone, is a “cluster”, a “bundle”, or “weave” movement – heterogeneous, common, multiple, and one that works only because of the community.

Illustration 8. “Readings” in “Pracownia” in 15 Okopowa St, around 1978/79

Source: Photo from State Archive in Olsztyn.

An interesting aspect of the upward movement is the inward movement, which can have multiple aspects. One of these is connected with self-development and self-knowledge, interconnected with going beyond individual egoism for the sake of the community. It is, therefore, close to koinopolitical thinking, but focuses more on the role of the individual and their attitude toward creation and authorship. A move inward is “a journey into yourself”, as in the artistic research of Edward Stachura, important to “Pracownia”. Stachura, wanting to get closer to the ideal of the “nobody-man”, tried to remove his name from the cover of his book Fabula Rasa, published by “Pojezierze” in 1979.

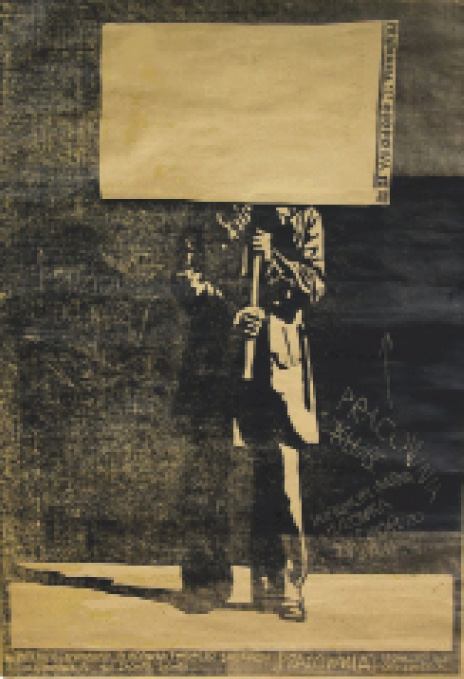

A picture that might represent the move inward is the so-called “blind poster” of “Pracownia”, made by Krzysztof Janicki. It was used as a frame into which information about the various activities of the group could be displayed. It depicts a “faceless” man against a graffiti strewn wall with the old name “Pracownia-Klub” (Club), (invented by “Pojezierze”) crossed out and the new one – Interdisciplinary Research Center “Pracownia” (proposed by Jerzy Grotowski) – added. The figure is holding a white banner at the height of his head as a peace manifesto and an empty space, ready to be filled with new content. The poster encourages the audience with the inscription “come to us” – inviting others to participate and co-create. It also refers to the theme of the road, through associations with a figure carrying a banner at a manifestation or pursuing “my own way” – searching for oneself or one’s own group identity.

Illustration 9. The so-called “blind poster” of “Pracownia” made by Krzysztof Janicki

Source: “Pracownia” archive, photo thanks to Ryszard Michalski.

The other aspect of inward movement is connected with a focus on the internal work of the group. This point is all about the processes of nourishing the members and the organization, the internal development, which is always reflected in external development of it. “Pracownia” promoted horizontal collaboration instead of the hierarchical structures characteristic of organizations of the time. Elite art was replaced by egalitarian creativity. Stars and “names” published by the “Pojezierze” Publishing House were opposed to the “ethos of the amateur” (Czyżewski, 1991) and collective work. The best artists and thinkers from Poland and abroad were invited to Olsztyn, and the young people gathered around “Pracownia” were involved in their activities. The very name can be understood as a “workshop”, and thus a place of work, a space for repairing what is broken, for tinkering, non-professional activity. A place to learn by trial and error or within theatrical rehearsals.

Janusz Bałdyga from the Academy of Movement [Pol. Akademia Ruchu] explained the use of this word in an interesting way in the context of “Pracownia Dziekanka”, which he founded in the second half of the 1970s in Warsaw. The name “Pracownia” was supposed to refer to academic workshops conducted by professors at the Academy of Fine Arts. Its nature was supposed to be educational, but dissident, subversive, because it was focused on bottom-up, peer learning (Sosnowska, 2018: 89–90). Vertical knowledge transfer has been questioned. Horizontal, due to the lack of a model, focused on research and self-discovery, which lead to the search for a new way of working: not theatrical, but creative, civic, and locally-oriented – what later became known as the animation of culture.

The “nobody-man” in the “Pracownia’s” poster represents also “every-man”. Moving inward also means an anthropological ability to go beyond the transparency of one’s own cultural, temporal, and spatial conditions; an empathic perception of the Other in oneself. This is especially important for artists working in the “recovered territories” and reflected in the performance by Krzysztof Łepkowski. It happened during the workshop initiating the founding of “Pracownia” in August 1977, which took place in the old Warmian house of the Doliwa family in Trękus, leased for years by Tadeusz and Maria Burniewicz. Łepkowski, shouting “I want to be somebody, who someone has already been” (according to the members of “Pracownia” – this was supposed to be a quote from Kaspar Hauser by Peter Handke) hit the wall of the barn several times with his shoulder, as if physically facing the material and spiritual heritage of Warmia and his brand-new presence under the old roofs. Many years later, another animator of “Pracownia” – Krzysztof Gedroyć – wrote in a similar spirit, outlining the spectrum, the gap between the multiman and the wholeman – the full humanity:

I should be a man multiplied, multi-person, full of biographies […] a non-fictional, or rather multi-fictional man […]. As a multiman – a person composed of many characters – […] I am the next rung on the ladder of evolution-degradation of the spirit, but the ease of transformation and the ability to live in parallel sometimes allow me to ascend to the level of a wholeman. (Gedroyć, 2003: 31)

Making a move inward, and rejecting the individual egoism, is about not only creating the self, but also transitioning the self in order to strengthen a community and intertwine with the memory of the place and its ghosts. It is a multidimensional development of the ego, the group, and the cultural dimension of the inhabited land.

Movement along paths and roads follows the lines marked by geography – in valleys, along rivers, around lakes. It is a research movement that enables the discovery and embodiment of the surrounding space. It is a movement that learns, embodies the landscape, finding its reverberations in one’s own body. The longitudinal movement on the ground enables cognition through movement. Walking in “Pracownia’s” case was inevitable – nobody had a car. Conscious walking to reach important places and along paths was also – as previously shown – a tool of developing a rooted identity and inhabiting the landscape, a transformation, a mutual adjustment; the first and basic type of relationship between a human being and earth.

Illustration 10. On the way to Plutki

Source: Photo from private archives of Tadeusz Burniewicz.

Movement along does not, however, colonize the place. It is not about ownership. As in the concept of “memory-place” as home, it helps the place to “achieve its freedom by liberating it from one ownership” and leaves the place open, being “a lived world of a simultaneous diversity of space” (Mendel, Theiss, 2019: 49–50).

The photo that made me think of movement along is the worn-out photo that Tadeusz Burniewicz found in his papers. It is winter, and Tadeusz Bury Burniewicz and Ewa Scheliga are looking into the lens of the camera, while two other men go forward to the village. People are dressed in sheepskin coats and wade through the snow that covers the path. The houses emerge against the background of the forest. It is the Plutki village, where Krzysztof’s brother, Maciej Łepkowski, occupied for a while an abandoned house that he received as a worker of a farmers’ cooperative (SKR) in the nearby village of Gradki. In 1978, the “Winter Activities” were organized there – a week-long workshop for youths, as well as a poetry and music event, where the audience, together with Piotr Bikont, read and recited American poetry: poems by Ginsberg, Ferlinghetti, Corso, McGregor, as well as contemporary Polish poets. In the spirit of “new life under old roofs”, they performed alternative culture activities in places with the quality of tabula rasa – places where something could start from the very beginning.

The promise of a brave new world was, however, burdened with logistical difficulties, resignation from amenities, constantly fighting the harshness of the weather and material conditions. Przemysław Radwański, an anthropologist who cooperated with “Pracownia” in the winter of 1980/1981, remembered going back to the freezing cold house in Trękus every day after working in Olsztyn and walking many kilometers in the darkness and the snow from the train station (P_PR_M_65_MDK_2022). Getting to know the land by making a move along is sometimes a challenge. Moving along is not, however, limited to the well-known roads, but also includes less obvious paths, long unused trails that need to be rediscovered.

It is surely inspired by the situationist drift – intentionally getting lost in space to see it in a new light, via disorientation. Drifting was, however, also recognized as a research method. Situationists used it to check how the urban environment shapes the desires the lives of its inhabitants, as well as to what extent they themselves influence its space-time; they created emotional maps of the studied field (Księżyk, 2015). The situationist borrowings are very significant here, as they give political meaning to activities as trivial as walking; a common gesture which in the socio-historical context turns out to be emancipatory, as it steals peripheral spaces and hands them over to alternativists, expanding the space of their involvement. However, “Pracownia” borrowed it intuitively rather than intentionally. As Ryszard Michalski recalls, they obtained a book about situationists, but in French, which no one knew (P_R_M_65_MDK_2022). Thus, it became an object of reference for building identity rather than a source of actual knowledge about their practices.

The drifting of “Pracownia” could also happen in an urban context. In 1978, Ewa Scheliga designed a city action called Lustration of the City in the spirit of drifting:

During the day.

Cold autumn or wintertime, when most people are studying or working. Before noon. The group gathered in “Pracownia” disperses to various parts of the city, each separately. There is an hour or two to contact some person – younger or older – who wanders around and does little useful for themselves or others. They are in a pub or somewhere. Waiting – not waiting. Thinking – not thinking. Try to bring the person over for tea, maybe a talk in “Pracownia’s” headquarters. Each member of the operational group brings one, maybe even two. It may happen that one of the operational group will not come at the appointed time, but will stay in the pub.

At night.

A similar effect on a summer night / late evening / when more than one holidaymaker or vacationer who cannot sleep on a hot night, wanders around the city. (Scheliga, 1978)

This and more similar city activities were often performed by “Pracownia”, especially in the spirit of an alternative getting to know the city, for guests and newcomers – making sightseeing non-stereotypical and liberating the tourist town from the cognitive cliches.

The last movement in this typology – movement across – makes it possible to change the world and create untrodden paths, third ways – alternatives that even if symbolic or temporary have the power of exposing the hidden possibilities of the world. By moving across we challenge the existing order, we ask “what if?”, we break our habits. In practice, the “movement across” is achieved by activities that juxtapose at least two, usually non-adjacent orders. They introduce something unknown, out of place, unusual.

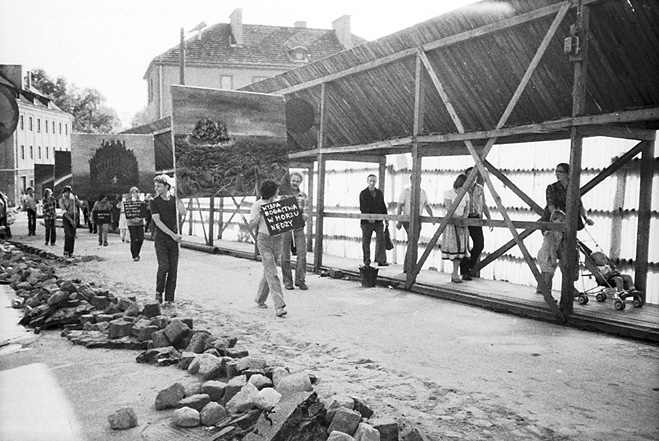

Illustration 11. Traveling exhibition of Tadeusz Piotrowski’s art. Olsztyn 1981

Source: Photo by Mieczysław Wieliczko.

A good example of a lateral movement that made me think of it as of another point of the typology was a traveling exhibition organized for the Olsztyn painter Tadeusz Piotrowski in the summer of 1981. The photographs by Mieczysław Wieliczko documenting it show a juvenile crowd gathered in front of the “Pojezierze” headquarters at Okopowa Street in Olsztyn, where the vernissage took place. Young people hold large-format paintings by Piotrowski with apocalyptic captions and lined up on the pavement. Then, they form a procession and go to the streets of Olsztyn, showing the traveling exhibition to random passers-by on the street. However, the in-depth value of this undertaking, portrayed so suggestively by the photographer (a record of everyday life in the city, dug-up streets, defensive walls supported by wooden piles, the locations of vegetable kiosks surprising today’s inhabitants, old-fashioned fashion) is not available without knowing the context. I became aware of it when I interviewed Piotrowski in the summer of 2022. While looking at the photos from the exhibition, I asked the painter: “Where are they going? Where are these streets?” He replied: “I don’t know, I’m from Olsztyn, but I don’t walk” (P_TP_M_70_MDK_2022).

Tadeusz Piotrowski, who died in February 2023, was a person with movement disabilities, a man who had used crutches, walking frames, and a wheelchair for years. For Piotrowski, movement was a technique, just like painting. He was fascinated with various painting methods – using different types of brush, cloth, or sponge to paint huge canvas at a very past pace. He would use this himself and while teaching his students, patients in the “Blue Umbrella” Association for Long-term Immobilized Patients where he worked as an art therapist. He painted a lot and gave away his paintings. Fascinated with horses, he would sketched with specially incised goose feathers, their silhouettes on the run, hurt, desperate. Tadeusz Burniewicz, who analyzed his art during the farewell meeting in Olsztyn’s Art Gallery in July 2023, called them self-portraits (P_TB_M_70_MDK_2023). Feathers, horses, fast mechanic painting techniques, they all resemble movement, galloping, and even flight, and for Piotrowski they were nothing like a substitute for walking. Movement was his obsession, a technique he mastered for years and which he lost in his last days.

The traveling exhibition from 1981, next to the apocalyptic imagery, was also tackling this problem. Due to the city’s poor adaptation to the needs of people with disabilities, Piotrowski’s paintings – set in motion by the members and supporters of “Pracownia” – could reach places that their author would not have reached. “Pracownia” put images and people who are absent, unrecognized, rejected, and marginalized in the city center.

By “moving across”, one can lift the limitations, even if only symbolically; create the alternative world anew: more inclusive, open, thought differently. This is a temporary interception, the carnivalization and subversion of order, a switching of places. Although carnivalization assumes the final confirmation and re-establishment of the existing order (the safety valve metaphor), it also contains elements of subversion. It reveals the arbitrariness of conventions and shows the possibilities hidden in everyday life (Dudzik, 2005: 103–115).

The pictures of “Pracownia” are more than just documentary photographs. They are a gesture of autonomy, a fight for the right to self-presentation and a search for a place for alternatives in the collective consciousness. They illustrate the subversive interceptions, the bountiful creation of common spaces, egalitarian ways of research of the world and oneself. In unstable times of crisis, in the border lands, and in the face of fluid identities, they show practices of rooting, embodying, othering, and dialoging with the world, to foster cooperation and create alternatives. They tell the story of different ways of negotiating with the memory-places and the communist system. Finally, they contribute to the creation of a bottom-up typology that fosters reflection on the aims and effects of culture animation projects as well as their critical and research potential.

The typology of six types of movement I propose (Dobiasz-Krysiak, 2022) helps to recognize culture animation as research through art. All of the moves are derived from praxis, community arts/culture animation actions conducted by pioneers of the field in Poland – the “Pracownia” Interdisciplinary Creative Research Center; six moves as six rituals of dialog, a packet of techniques to elaborate on social issues in an indirect, art-mediated ways; six ways of challenging but also empowering communities and individuals in order to expand the realm of the unofficial; six ways of asking questions and searching for new answers. They might be a starting point for the grass-roots, inclusive arts-based research methodology that Susan Finley is opting for. Every move in the typology opens a new research field and raises new research questions that may be presented in a Table 1.

Table 1. Typology of six moves

| No. | Type of movement | Research field | Main research question |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Move downward | Problem identification | What is missing? |

| 2 | Move downward 2 (subversion) | Ways of resistance | How to say no? |

| 3 | Move upward | Group building | Who is with me? |

| 4 | Move inward | Self-development | Who am I? |

| 5 | Move along | Land knowing | Where am I? |

| 6 | Move across | Change making | What if? |

Source: own elaboration.

By developing new, detailed research questions and applying them to new culture animation projects, I hope to eventually develop a methodology aiming at widening the democratic public sphere and expanding human agency, collaboration, and abilities of critical thinking in searching for alternative solutions in times of crisis.

By interdisciplinary study of the legacy of “Pracownia” and giving it its rightful place in the history of Polish social creative activities, the research aims to fill in the gaps in the history of the Polish community arts/culture animation. I hope this typology will provide useful tools for social scientists to understand and analyze culture animation projects in light of action research. There is a need to understand them as research tools providing information on the artists and communities. Furthermore, treating it as checklist or guidelines may allow animators from various schools and traditions to conduct in-depth animation and research activities. I hope it will stimulate discussion and contribute to building the coherence of culture animation and its theoretical amplification.

Cytowanie

Maja Dobiasz-Krysiak (2024), More Than a Photograph: An Analysis of the Photographs of the Interdisciplinary Creative Research Center “Pracownia” Using the Six-Moves Typology in Arts-Based Research, „Przegląd Socjologii Jakościowej”, t. XX, nr 3, s. 50–81, https://doi.org/10.18778/1733-8069.20.3.04

Banasiak Jakub (2020), Proteuszowe czasy. Rozpad państwowego systemu sztuki 1982–1993, Warszawa: Akademia Sztuk Pięknych w Warszawie, Muzeum Sztuki Nowoczesnej w Warszawie.

Certeau Michel de (2008), Wynaleźć codzienność. Sztuki działania, Kraków: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego.

Czyżewski Krzysztof (1991), Etos amatora, “i-miesięcznik trochę inny”, vol. 4.

Czyżewski Krzysztof (2017), Czas animacji kultury, [in:] Krzysztof Czyżewski (ed.), Małe centrum świata. Zapiski praktyka idei, Sejny-Krasnogruda: Pogranicze, pp. 137–147.

Debord Guy, Wolman Gil Joseph (1956), A User’s Guide to Détournement, translated by Ken Knabb, “Buerau of Public Secrets”, https://www.bopsecrets.org/SI/detourn.htm [accessed: 13.06.2024].

Dobiasz-Krysiak Maja (2022), Na drodze do metodologii otwartej, czyli animacja kultury jako badanie na przykładzie działań olsztyńskiej „Pracowni”, “Prace Kulturoznawcze”, vol. 26(4), pp. 37–62.

Dobiasz-Krysiak Maja (2023), Wydeptywanie geografii działania. O praktykach badawczych Interdyscyplinarnej Placówki Twórczo-Badawczej „Pracownia”, “Konteksty. Polska Sztuka Ludowa”, no. 3, pp. 300–312.

Drozdowski Rafał, Krajewski Marek (2010), Za fotografię! W stronę radykalnego programu socjologii wizualnej, Warszawa: Fundacja Bęc Zmiana.

Dudzik Wojciech (2005), Karnawały w kulturze, Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Sic!.

Finley Susan (2018), Critical Arts-Based Inquiry: Performances of Resistance Politics, [in:] Norman K. Denzin, Yvonna S. Lincoln (eds.), Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, Thousand Oaks: Sage, pp. 561–575.

Gedroyć Krzysztof Jan (2003), Listy z dolnego miasta, Białystok: Fundacja Sąsiedzi.

Godlewski Grzegorz (2002), Animacja i antropologia, [in:] Grzegorz Godlewski, Iwona Kurz, Andrzej Mencwel, Michał Wójtowski (eds.), Animacja kultury. Doświadczenie i przyszłość, Warszawa: Instytut Kultury Polskiej, pp. 56–70.

Gross Frederic (2021), Filozofia chodzenia, translated by Ewa Kaniowska, Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Czarna Owca.

Gudkova Svetlana (2018), Wywiad w badaniach jakościowych, [in:] Dariusz Jemielniak (ed.), Badania jakościowe. Metody i narzędzia, vol. 2, Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, pp. 113–127.

Harper Douglas (2014), Co nowego widać?, translated by Łukasz Rogowski, [in:] Norman K. Denzin, Yvonna S. Lincoln (eds.), Metody badań jakościowych, vol. 2, Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, pp. 153–174.

Ingold Tim (2018), Splatać otwarty świat. Architektura, archeologia, design, translated by Ewa Klekot, Dorota Wąsik, Kraków: Instytut Architektury.

Interdyscyplinarna Placówka Twórczo-Badawcza „Pracownia” (1981/1982), [in:] Ewa Dawidejt-Jastrzębska (ed.), Sztuka otwarta. Parateatr II. Działania integracyjne, Wrocław: Ośrodek Teatru Otwartego „Kalambur”, pp. 62–72.