https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7370-3490

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7370-3490University of Lodz, Poland https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7370-3490

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7370-3490

Abstract:

The paper is a contemplative explication of the walking process. What are the essential features of walking, and how do those who stroll around the city experience walking? We used contemplative research methods and explication of the phenomenon of walking. The research is based on self-observation and self-reporting about the thoughts, body feelings, and emotions that emerge during walks.

In the paper, we describe the features of the phenomenon of walking. First, we investigate the minding process generated by walking in the city. Then, we elaborate on the pathic dimension of walking (especially the mood), body feelings (lived body), lived relations, and reflections on life and self that are a consequence of walking.

Keywords:

contemplative studies, walking in the city, body, emotions, self-observations, sociology of body, sociology of emotions

Abstrakt:

Artykuł jest kontemplacyjną eksplikacją procesu spacerowania. Jakie są istotne cechy spacerowania i w jaki sposób osoby spacerujące po mieście tego doświadczają? W opracowaniu wykorzystano kontemplacyjne metody badawcze i dokonano eksplikacji fenomenu chodzenia. Badania opierają się na autooobserwacjach i autoopisach myśli, odczuć ciała i emocji, które pojawiały się podczas spacerów u uczestników projektu badawczego.

W artykule opisano cechy zjawiska spacerowania. Najpierw przeanalizowano proces myślenia generowany przez chodzenie po mieście. Następnie omówiono patyczny (ang. pathic) wymiar chodzenia (zwłaszcza nastrój), odczucia cielesne, doświadczanie relacji z innymi oraz refleksje nad życiem i sobą, które są konsekwencją chodzenia/spacerowania.

Słowa kluczowe: badania kontemplacyjne, chodzenie po mieście, ciało, emocje, autoobserwacje, socjologia ciała, socjologia emocji

Walking seems to be a simple activity that is taken for granted; people walk because they must go to work or church, see friends, or walk for no reason. They have always walked, and they will walk in the future. They should move their body across the space to achieve some goals, and they walk without any specific purpose. Walking has an evolutionary background since primates developed bipedality about three million years ago (Lovejoy, 1988; DeSilva, 2022). Genetically, we are predisposed to walk (Lewis, 2023). This evolutionary innovation of the humanoids had pragmatical reasons, but today, walking is culturally marked by multiple meanings.

Walking is so natural that we do not think much about it; it just happens. We are not aware of walking. We do not have a reflection on how we walk, what it means to walk, where we walk here and now or in our whole life, in which direction we navigate, and what we will achieve by walking our entire life somewhere.

The activity of walking seems to be an essential feature of our being. Some people cannot walk, but they have moved across the space sometimes because they must do it. Some people do not move; they stay in the same space for many reasons: illness, imprisonment, being on the run or trapped in a cave, for example.

Reflection on walking happens very rarely. It comes when we have a strong incentive from the outside or the inside of our mind, body, or feelings when we experience strong emotions or have a traumatic experience. Then we start to think sometimes about walking; it is usually practical thinking – what walking can do for me. But sometimes it’s a contemplative reflection, when we think about walking as a way of living and struggling with the lifeworld (Kaag, 2018). So, there we can study this reflection, the “immersion” in the world, immersion in walking here and now, so the presence in here and now can be learned and experienced by senses (Low, Kalekin-Fishman, 2018; Svensson, 2021; Oblak et al., 2022). The mind observes the self, and the reason is self-conscious. The mind and body create the consciousness of the present. The presence of self and body is embedded in the lived space; it is experienced directly by the subject moving and feeling the body. Reality is constructed by our lived experiences of space, time, body, and relations with others (van Manen, 2014).

We can express our lived experience in the language that we know. We also base our perception on some knowledge that we learned before (Solnit, 2008). There is no other choice. Language is often limited in its ability to fully express how we experience the space: “But lived space is more difficult to put into words since the experience of lived space (as lived time, body) is largely pre-verbal, we do not ordinarily reflect on it. And yet we know that the space in which we find ourselves affects the way we feel” (van Manen, 2016: 102). But the operations we do in any language could help touch what we feel in a pathic way (van Manen, 2014: 270), a deeply felt emotional way of experiencing the world and the objects in any situation we are thrown into. We can use metaphors or poetry, or we can describe our feelings in a specific sequence of words to capture what we have just felt.

Walking also has a historical dimension. The fashion for waking was created in the United Kingdom in the 18th/19th centuries. It was slowly accepted by the aristocracy and middle class as entertainment, allowing them to admire the natural landscape. Village surroundings were more appreciated at the time, and gardens and parks were created especially for walking, looking for solitude, reflection, and private talks (Solnit, 2008).[1] Walking in the city was never so appreciated, even now. However, attitudes have changed, and the 19th century saw the arrival of the phenomenon of flâneur, the term introduced by French poet Charles Baudelaire in his essay “The Painter of Modern Life” (1964). A flâneur is an “objective,” detached observer who strolls, explores the town’s space and its diversity, and appreciates the city’s atmosphere and heterogeneity. He/she can also be inspired to create some art.[2]

These days, we have organized walking tours to appreciate a city’s architecture or learn about its exciting places. Generally, walking is a must in the city when we want to get to some places, and the research described below concerns mainly such situations.

The space can be perceived as a physical structure. Maps of the roads, paths, and buildings within a space reflect this physical image. However, when we move with our body through this physical space, the space is lived, which can be significant in how we act and feel while walking. In every city, a specific mood can be created, and some specialists even say that the atmosphere is related to the rhythm of walking, as well as the unique spots and places in the city (see Paetzold, 2013). The mood can be different in Delhi and different in Łódź or Warsaw. The rhythm of moving in Delhi cannot be determined by individual will – there are always traffic jams and many people on the streets. The rhythm of the whole city moves the people forward (Caparrós, 2020); they should adjust to the rhythm. Sometimes, it is hard to move on foot, like in Jakarta (Cochrane, 2017). Individuals can have more choices in less congested cities. To understand walking, we should dereify the space[3]; it is reified when perceived as independent. However, when we look at the subjective experience, we can see the mindful connection of the person to the object – in our case, the physical space and the things in it. There is no space in the human world without experiencing it. Walking is more than a physical activity; it is always experienced in a unique way. We have a pathic approach to walking, and to space, too. Therefore, both walking and space will be dereified in our investigation.

Walkers in the city use tactics to move and go forward (de Certeau, 1984; Kočková, 2015). They are micro-choices they make within architectural structures that are imposed by the strategy developed by those with power (see also Middleton, 2011). Not everything is copied by the city flâneur, although he is the gamer of the space (Bauman, 1994). It is challenging to be a flâneur in a contemporary Western city where people are in the “acceleration cycle” (Rosa, 2020) to better themselves in their careers. They live in an achievement society where they are their own entrepreneurs and exploiters (Byung-Chul, 2022). Walkers adapt to a particular environment that has already been designed. However, everything takes place within the framework of a particular plan, which the walkers do not necessarily follow. This basic thesis by de Certeau (1984) shows a particular sphere of freedom in choosing paths that lead to a goal or options made while free walking (without a specific purpose, it is a flâneur style of walking, Benjamin, 1997; Rosenbloom, 2023). Tactics are usually unpredictable, arising from individual needs and adapting to the environment. The accompanying experiences can also be particular and individualized if tactics are unpredictable. Thus, to de Certeau’s theory, we can add one dimension, the experiential domain, which is always associated with human walking. It shows what happens in the mind and body of the person walking when she/he makes a particular decision and then acts, i.e., walks, takes shortcuts, speeds up, slows down, or perhaps is lost or does not know what to do. Often, the person’s experience oscillates between feeling happy and experiencing suffering. Emotions constantly imbue experiences with meaning (Clark, 2002). The walking becomes pathic.

In our research, I wanted to capture and understand the lived experiences of walking in the city. Many contemplative experiments were arranged (see examples in Konecki, 2018: chapter 10, for methods; Konecki, 2022: chapter 5) to allow me to describe the essential features of walking based on the lived experiences in different situations. Walking is the object of the study, but it is also the method (Hall, 2009; Middleton, 2011). I had planned descriptions of different types of walking. However, I did not know which kinds would emerge. Together with students participating in the project, I reconstructed the following types of walking, as each type has a different intention/motivation: walking to university/work (purposive walking), walking without any goal (free walking, strolling, similar to flaneur style), walking while being lost in the city (trying to find the road to the destination, like a hotel), and walking to favorite places in the city (to appreciate them). Later, we deepened the descriptions by repeating the walks in these types. We wanted to get the feelings of the body and the emotions that appeared and dominated thoughts while walking; it was aimed to be an individual walk.

Fifty-seven students participated in the project. The first experiments started during the class “Meditation for Managers.” The course was voluntary for Erasmus Program students (from Spain, Portugal, and Turkey) and Polish students in the 2022 summer semester (the classes were in English); thirty-four students participated. They participated in yoga practice online and in a park, and they had walking exercises. The exercises of meditation, mindfulness of the body in yoga practice, breathing exercises, and mindful walking (walking meditation, Nhat Hanh, 2021) prepared them for a contemplative approach to research.

In these experiments, other students also participated in another class, “Contemplative Sociology. Experiencing Self, No-Self, and the Lifeworld” (23 students, 2022–2023, winter semester). It was for Erasmus students (from Spain, Turkey, Portugal, and Japan) and Polish students, who chose the course voluntarily. Once again, the students participated in yoga practice, meditation, and breathing exercises to prepare them for self-observation and self-description (see Konecki, 2018: chapters 8 and 10). They received instructions on how to make a self-observation and a self-description (these methods are instructively described in Konecki, 2018: 229–231), and we discussed them during the class. The self-descriptions were presented during the course and collaboratively discussed and analyzed.

Walking meditation in the park was an essential part of the research preparation, and was done collectively. The students learned to observe their thoughts, feelings, emotions, and surroundings while walking in the park. They were also encouraged to see the difference between mechanical (not mindful) and conscious walking.

The students were obliged to walk and make self-observations while walking individually and write their self-reports, but they were not obliged to present them publicly and elaborate. In the experiments, they agreed to give their self-descriptions and to elaborate on them, and they also agreed that their self-reports could be published. All the self-reports were written in English, and the reports’ explications were also done in English.

The students were from many different countries; some were strangers and did not know the city, and some were inhabitants of the town. This may have influenced the knowledge and individual experience of the space. However, we looked for the general features of walking. Even being a stranger could intensify the experiencing and mindful perception of some walk types (e.g., fear of being lost in the city). Therefore, it was easier to reconstruct the features and describe the experience (emotional/pathic dimension of walking). We considered many elements of the walking situation: being a stranger or inhabitant of the city, gender, weather, temperature, architecture, street layout, and type of walking (goal of the walk), among others.

The phenomenological and contemplative approaches are the theoretical and epistemological background of the research (Bentz, Shapiro, 1998; Rehorick, Bentz, 2008; van Manen, 2014; 2016; Bentz, Georgino, 2016; Konecki, 2018; 2022). The research is based on the self-observations and self-description of the lived experiences while walking. The method aims to capture and describe the experiences as soon as possible. We wanted to reach the point where the background is a starting point for reflecting on the phenomena. In this way, we can reconstruct the meaning of the phenomena as it emerges in lived experiences. “The world is not what I think, but what I live through… If one wants to study the world as lived through, one has to start with a direct description of our experience as it is” (Merleau-Ponty, 1962: xvi–xvii). The body gives us access to the world.[4] Therefore, we can observe our relations to other people and material objects and feel the atmosphere of the place/space. We resonate with the surroundings through a pathically tuned body. Everyday language or poetic language can express pathic knowledge and meanings, but it is sometimes impossible to describe them more abstractly. The mood of the space, for example, a cemetery (Konecki, 2022: chapter 5) or public places in the city (Konecki, 2017), is inherent in sensual, emotional aspects felt mainly by the body. The mood is experienced directly and immediately; it is not analyzed at the moment it is felt (for a similar view on the atmosphere of the city, see Paetzold, 2013); it is also pathic. The pathic relationship with the world means “the immediate or unmediated and conceptual relation we have with the things of our world” (van Manen, 2014: 270). The phenomenon of walking could be interpreted in a pathic way, first by experiencing it in a concrete situation and second by reflecting on the experiences. The research participants and author express their feelings vocatively (pathic resonance of the situation), and reflection will follow the style of this appearance.

Contemplation is the meditative and insightful way of explicating living experiences while referring to the phenomenon and contexts/situations where the phenomenon is experienced (Konecki, 2022). We want to see not only the expression of the experiences from the first-person perspective but also to make explicit the assumptions of the description and explication of the phenomenon. We tried to do it in our research by writing the contemplative memos that make this research report readable.

In the paper, we explicate the minding process generated by walking in the city. Next, we elaborate on the pathic dimension of walking (especially the mood), body feelings (lived body), lived relations, lived time (van Manen, 2014), and reflections on life and self that are a consequence of walking.

Thinking about the present and past is often connected with walking. We can be more conscious and concentrate on the signs that are reminders of the past. The body remembers the places, and some thoughts and emotions come to the stroller when walking in a particular area. The area could be the park, which was created as a place for walking in the 18th/19th centuries (Solnit, 2008), and we still benefit from this invention.

Walking in some areas of the city can become memory walking. It means that those walking about recollect some events that they experience in the space where they are in the moment. These thoughts are sometimes connected with emotions (sadness or nostalgic feelings); for example, during the same walk, negative and positive emotions can appear, as in the example below. The pathic dimension is always present in walking:

Across the road, I see a cat running, and I think about how much of a threat it is. Unfortunately, I recall that my cat was hit by a speeding car a few years ago and died. I feel a stab of sadness… I remember when I was little, in this park with my mother and my previous dog, and I start smiling. (woman, free walking)

While walking, we can experience many things. Life becomes more holistic when we notice it. We can notice refreshing temperatures, hunger, a desire to eat, seeing friends, and dog walkers. However, we can also feel the smog and difficulties in relaxing in a city full of fumes, dirt, and cars that do not care about pedestrians. Drivers own the space; even when we go on the sidewalk, we can be splashed by the cars. The chaos of the city prevails in the perception of strollers. A lot is happening on the street; however, we should be mindful to notice it.

I decided to go on the far side of the pavement, which turned out to be a good idea just a few minutes later as I was startled by the same couple, who were once again soaked by a puddle. It made me laugh a bit; however, simultaneously, I felt pity for them. It was only the morning, and they already knew it wasn’t their day. They walked across the lawn resignedly, and I quickly lost sight of them in the fog. Not long after that, I got hungry. Fortunately, I quickly found a Żabka, a convenience store, and bought some snacks. It made me sad when I realized they were much cheaper and tasted better a few months ago, and I’m likely to stop buying them for a while. Soon after, I ran into a friend who was out for a walk with a dog; we decided to walk together for a while before I went home. In the end, meeting a friend was the only good thing during that walk. Maybe it wasn’t that noisy, except for some cars passing by, but I couldn’t relax. Most of the time (over an hour), I walked around houses with inhabitants who took Kaczynski’s words too literally to burn anything except tires.[5] Over a dozen times, I had to cover my mouth and nose; sadly, walking was meaningless in such dense smog, and I coughed a few times. It didn’t even make me angry; it made me more irritated and sorrowful as I could not go out and breathe fresh air. (man, free walking)

Some students achieve the mindfulness of walking spontaneously; without instruction, they observe; for example, they have feet, and they cannot understand why they are doing it. But concentration appears anyway:

While walking without slowing down, I realize something: I constantly look at my feet and count. I don’t even know what or why I’m counting, but I always catch myself counting. While walking with my headphones on, I look around. I try to walk without looking at my feet, but after a while, I catch myself looking at my feet again. I can hear the cars, people, and trams passing by, but I don’t see them because my eyes are always on my feet. After passing the stop on Sterlinga Street, I try to pay more attention to my surroundings because if I don’t turn left, I will take the wrong road again. (woman, going to University)

The mind is observed, and mindfulness emerges. However, mindful walking shows that walking is also an emotional process; it could start from one emotion and finish with another. The mind collaborates here with the emotional part of the self. In the case below, the woman initially experienced fear and anxiety, but later, she became calm and relaxed:

After this walk, I was very calm. It was only a 20-minute walk, but I experienced a lot of emotions, beginning with fear and anxiety and ending with calm, relaxation, and peace. It is amazing how deeply we can feel emotions. (woman, free walking).

Students used walking to relax and calm down on their way to university. They wanted to relax before the exam, to stop thinking about it, because it was incredibly stressful for them. So, walking is used instrumentally; it’s challenging to walk without any purpose because we are usually used to walking to a particular destination point or walking to do something or achieve some effects, to stop thinking, or change the topic of thinking:

I had a tough exam this week. Because I was very stressed, I decided to go to university on foot to calm down before the exam. In my head were mainly thoughts related to the test that I was about to take, but I decided to focus on what was happening around me because I knew that excessive thinking and stressing would not help me. […] All the time, I was trying to breathe deeply and evenly. At a steady, not-very-fast pace. What distracted me was a family of ducks that swam across the pond. I paused momentarily to look at the mother and the little ducklings. They looked cute, and I felt very nice. The walk through the park before the exam turned out to be an excellent idea because I relaxed and entered the room very calm and relaxed. (woman, walking to University)

My first-person perspective

But where do the thoughts about walking come from? Only from the body and direct experience of roaming? I refer here to my experience and having a phenomenological perspective. I want to bracket my thoughts and reflections about walking. Here are my initial free associations about walking:

Walking is life for me. Walking inspires me to write poems and scientific articles; it stimulates my body and thinking, so I create new ideas. I want to contemplate the beauty of my surroundings and my feelings of the body and mind. Moreover, it is healthy to walk 8000 steps a day. I read about it. I should measure it.

I want to wander in my city, but I’m hindered by many things: renovations, potholes in the road, and those damn drivers who want to run me over. The worst are cyclists. I don’t like them. But when I ride a bike, I don’t like pedestrians. I get sick of walking in the city. (Wow, what the strong emotions appeared!). I go out into the woods. Is that an escape? (man, free associations with walking)

Now I make an epoché and list the principles that I have gotten from my lifeworld concerning cultural and scientific presumptions:

When analyzing the experience of walking, I should have in my mind what I already knew about it. I cannot escape from these assumptions that I have learned. However, if I take them away and look at what is left, I concentrate on the body’s feelings and the specificity of the mind and emotions while walking. These processes of connecting the mind, emotions, and body remain to be explored more deeply, and I can see them beyond the given cultural and scientific filters.

The pathic dimension seems to be the most interesting aspect of walking, especially in mindful and free walking, even as we strive to achieve the practical goal of the research. We feel emotions and experience the world, but we do not always notice it (Kotarba, Johnson, 2002). When we see it, we wonder that the world exists not only in our mind but also in our mind and body. We can perceive what is around us and create a particular recognition of our being in the world. We react to the outside world, which is full of objects, but only when we are open to and explore them. The flâneur style of walking helps.

We did many kinds of walking in the project: purposeful walking (walking to and from University or work), free walking (without any goal), and walking to favorite places. All these kinds of walking had common basic features. Emotions and sensual feelings permeated them, and the environment was the object to interact with. The different kinds of walking also had distinctive features, but walking, in general, has basic qualities that make it unique.

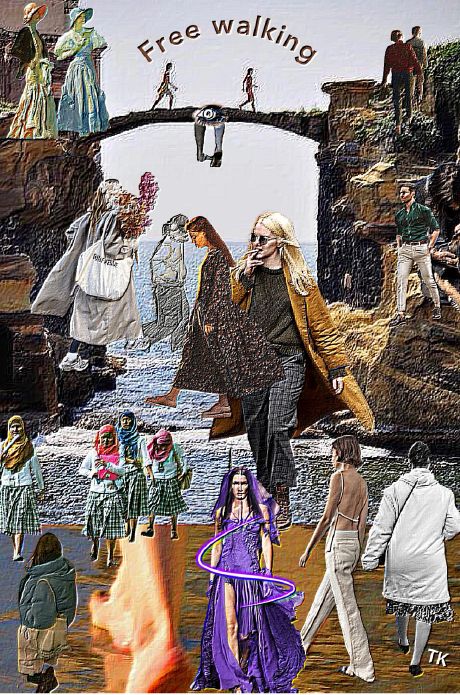

Collage 1. Free Walking, flâneur style. Visual impressions of the author about walking without a goal; based on the self-reports

Source: collage by the author of the paper.

The pathic aspect of walking can be observed while walking to university or work. It is connected with emotions, which are an essential part of the way we approach our destination. The future and the distance to cross may be associated with fear, for example.

Students sometimes felt fear while going to university. They were afraid of what would happen in the class if they could not face the difficulties of studying.

On my way to university, I pass through the EC1 building, where people start their work. The fear I felt was probably caused by fear of the rest of the day at college. Can I do all my jobs? Will the lecturer demand anything from me beyond my capabilities? Or maybe I’m just scared? (man, going to university)

The fear can also come from imagining some danger on the street. Female students (foreigners) can feel fear. The student below is afraid of the backyards, where somebody could suddenly appear and pull her in, so she is scared of the people who walk on the streets and could follow her. This is the student’s interpretation, but maybe it is based on some experiences or information about the danger she has heard from other students:

After I turn the corner, I am disturbed as I realize a middle-aged man is staring at me. I speed up my steps. I feel like, at any moment, one of the entrances of the backyards of the buildings I pass by will grab me and pull me in. Then I look back and see the man following me, even if the distance is between us. Since I don’t feel safe, I just walk to Sterlinga Street, stop, and take the tram from there. (woman, returning from university)

Returning from University is also connected with pathic feelings – students no longer felt the burden of the emotions, and they felt safer, especially when they were going back in a group. Their bodies could feel it. The relationships with others gave them feelings of happiness, and being together was not connected with the formality of the class:

When I left the university, I felt a slight relief in my chest; the stress slowly flowed from me. At that time, I focused only on returning to the apartment as soon as possible, where I could rest. Whenever I go back home, I am rarely alone because I am accompanied by friends from uni and feel safe for some parts of my return time.

My journey to and from university was an emotional rollercoaster, starting with a fear that sat somewhere deep in my head to a sense of security throughout my body in the presence of friends. (man, returning from university)

At my parent’s house, the first thing I see as soon as I step outside the front door is the green but already dried-out grass; I see my dog running happily towards me; I see the forest behind the fence – then I feel free and happy.” (woman, after returning from university)

The contact with nature in the last quotation gives happiness. There is a feeling at home and in nature at the same time. The body’s reciprocal and close relationships at home and in nature after returning from university.

The feeling of happiness could be connected with feeling a specific mood. Mood is felt, but it also has symbolic meanings associated with particular emotions. Grey buildings represent coldness and emptiness. Mood can be enjoyable or sad. City streets have the potential to create a particular mood at some time, in some situations. The weather, the atmosphere, and the natural surroundings can interact with our minds and hearts; a unique mood is created by just being on the street. Cold weather, empty streets and the gray colors of the roads and nature make the landscape sad and depressing. This is where associations with emptiness appear. The landscape is void of vibrant colors and warmth. Instead, it is full of coldness, grayness, and sadness. Pathic description emerges:

The emptiness I felt was because of the landscape. As I mentioned, the leaves looked pale, and some trees were now completely naked; their color was also a pale gray, so they looked sad. Plus, the people’s mood in the streets and the cold hard walls of the buildings [were] in cold color tones; the landscape looks sad, and it leaves a sensation of emptiness. Though calm, the lack of a vivid atmosphere makes the city quite a depressing place for me. I also saw a set of big grey buildings; I remember that view as representing coldness and emptiness. (woman, going to university)

Enjoyment can also be felt during the cold weather because it is, at least partially, accepted. We can also find exciting things while walking, such as murals, which are the new aesthetics of contemporary cities. They are created for the modern pedestrian (Paetzold, 2013). Therefore, we can enjoy the weather and our bodies’ reaction to the coldness.

How we protect our bodies could also be an exciting experience. We can clearly re/interpret the enjoyment of walking in cold weather. The mood depends on our dialogue with nature and changes in time. It could be accepted as part of nature influencing our body, but at the same time, it may not accepted for psycho-social reasons:

At last, I felt enjoyment as I walked. I like observing and being curious, walking through streets I don’t know, and finding others I know. I also like the fresh and refreshing feeling of coldness and seeing how my breath is visible in the form of steam; I have always wanted that about winter, something I can only see in that season in my city. However, I can now see it every day, just by barely breathing. At the same time, it was freezing, so I also enjoyed the warm feeling of putting my hands in my pockets or the feeling of covering my neck and half of my face with a light scarf; if you don’t place it too tight, you can feel the warmness through the movement. During the walk, I also found an interesting mural I hadn’t seen before. It had great details, and I took pictures of it; in that sense, I find Łódź entertaining. Finally, when I entered the hall of residence again, it was warm inside, which I found comforting. Still, I found it boring mainly, which meant I enjoyed being outside, walking, and feeling the cold… (woman, returning from university)

Free walking (without any purpose) can be a challenging experience because the students are not used to walking without any goal. They are usually busy thinking about what they should be doing soon. The practical side of life prevails, although finally, the walking can be felt to be enjoyable:

The walk was a tough experience because I didn’t have much time for it, but finally, it was enjoyable. (man, free walking)

Some students felt unsure about the meaning of free walking – whether it is possible with time constraints; business, as a feature of the lifeworld, prevails:

Walking without a destination gives you the feeling of being liberated, not being lost. You don’t limit yourself to going anywhere. It’s nice to be able to turn right just because you wanted it at that moment and turn left at the next crossroads just because you wanted to. However, I think that for this, we should empty our day. If we give ourselves a time constraint without a destination, we’re still limiting ourselves and deflecting the purpose of walking without a destination. (from correspondence with a student, woman)[6]

Intense emotions appear while walking, especially when the students are lost in the city. Being lost in the town creates negative feelings, and emotions close to panic. Sometimes, we feel stressed thinking about how to save ourselves and get home. However, constructive ideas come, and self-indications (Blumer, 1969) connected with calming down are evoked. Negative emotions go out. A person feels relief and can recognize the familiar surroundings in the city’s space. The exciting thing is that when the technology stops working (e.g., Google Maps, smartphones), the problem of finding the way into the town starts. Today, technological devices often direct walking. Below, we can see a pathic and vocative description of the situation:

I remember the last time I got lost. It was a few weeks ago, and my sense of direction is lousy. I took a different bus home because Google Maps told me to. But then, when I was on the bus, my phone stopped working, so I didn’t know where to get off, and my house was a few meters away from the stop. So, I didn’t stop at the correct stop. I stopped so far away I thought I was about an hour away from home. I didn’t recognize any streets, trees, signs, bars, shops… I was utterly lost and without a phone or money. I was by myself looking for an address that would give me a clue to get back home. I felt overwhelmed, stressed, and in panic. I didn’t enjoy the feeling until I sat on the floor supported by a wall and started thinking about what to do while observing a flock of birds. I guess they were migrating; that was beautiful. When I started noticing that, I felt peace in my heart, and then I could think clearly without having this dark cloud in my head of negative thoughts. I realized I could take the bus and stop at a few stations to at least feel in the city’s center. But I didn’t have money, and my ticket was expired, so I had this terrible feeling of being caught on the bus, so I started praying and manifesting that everything was going to be okay. So, I was looking out the window, singing this song in my head by Chelou, Real, and this line came to me: ‘It’s only as bad as you make it.’ So, I stopped at the next station, started walking in the direction I thought was correct, and then noticed things that looked familiar. So, I felt relieved and calm. I knew where I was and knew where I should go. (woman, report on being lost in the city)

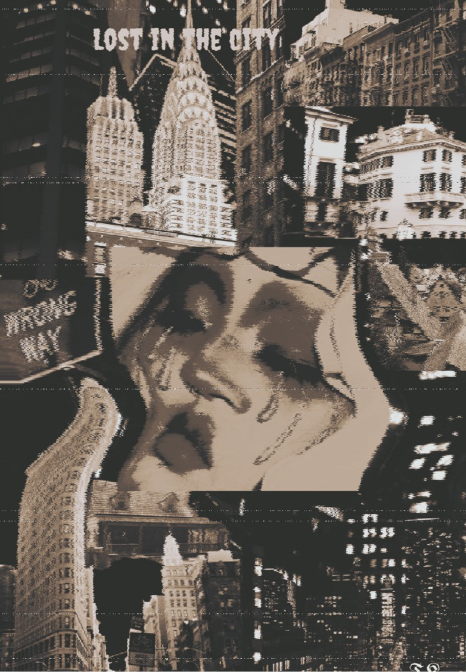

Collage 2. Lost in the city. Visual impressions of the author about being lost in the city; based on the self-reports

Source: collage by the author of the paper.

Walking can be divided into different stages of mood. Temporality is important when experiencing walking. Initially, people who are walking can be in a good mood, enjoying their surroundings, and thinking about only pleasure and pleasant things. But after some time, their mood changes when they realize they are lost in the city. Initially, they feel a little annoyed, but still self-confident that they can find their way without help from others. Embarrassment and anger can appear after a few moments of wandering around the urban space. Some desperation also comes to their minds, and asking others about how to get to the destination can start. The worse the mood, the more the anger manifests itself. But suddenly, when others help us find our way, the mood changes, and once again, we feel safe in an urban space that was previously so difficult to decipher and start to enjoy walking together with strangers.

The three stages of walking, as determined by the mood criterion, can be differentiated in the typical example of being lost (see below): enjoyment while walking, negative feelings from being lost, and back to joy after finding the way.

The first road was enjoyable. We admired the beautiful palm trees by the huge beach and the unusual view. It was nice to see people spending a great time with their friends on this great beach with gentle waves coming from the sea. The other side was not so pleasant when we were returning to the hotel. Not having telephones and no signs leading to the hotel was challenging. We thought we knew the way, or so we thought, because the trip in the first direction went without any complications. We told each other, ‘It will be easy; we will get back to the hotel without anyone’s help.’ Unfortunately, we were wrong. It’s hard to remember the topography of a city that was in a foreign country. We walked thinking we knew how to walk; we wandered around the center of the city for another hour, and then we realized that we were going around in circles and that something had gone wrong. Furious and embarrassed, I felt like a leaf moving in a vast wind leading nowhere. My girlfriend started laughing at me and told me to calm down because we were on vacation and had plenty of time. However, it was late at night, most tourists were already in their hotels, and on the streets were mostly locals, which confused me even more. We approached a local and asked in English if he knew the way to the hotel where we spent our holiday. However, it turned out that his English was not of a high standard. He tried to answer us something, but he combined English with his language, and in the end, we did not learn anything from him. So, we went on, wandering through the center’s narrow streets, getting lost again. There were a lot of local groups of Spaniards on these streets, which put me in a gloomy mood, so I approached one of the groups, asking them if they knew the way. These people could not answer the question, so I left and walked on. My girlfriend also lost her good mood and developed great anger and fear. Our mood to travel further did not make it easier for us; we also felt we were there alone. We found a bench and sat down because we were exhausted and it was hot, despite the late hour. Sweat was pouring out of us like from a waterfall. We had no water to drink with us. We sat on this bench, wondering how to go on, probably for the next quarter of an hour; we got up, cooled down, and started our journey. Despite the rest, we continued walking with a very nervous step. A group of Polish people appeared on our way; these people were a great salvation for us. They knew how to get to our hotel because they were also spending their holidays there. So, we started laughing; our whole mood changed; we were fortunate they had water with them, and they gave us a drink. (man, report on being lost in the city)

Aesthetic feelings can create the mood. Some students mentioned their favorite places in the city, concentrating on describing the sites as streets. The aesthetics become essential for them in these moments. They reflect on the sites, for example, on changes in the road and on the mindful walking itself:

I finally arrived at Piotrkowska Street. This is one of my favorites, of course. It looks well-kept and is full of people who spend their free time in cafes and restaurants. I feel safe here, and the renovated buildings and sidewalks satisfy my sense of aesthetics. Christmas decorations are already hanging above the sidewalk and glowing. Christmas trees are being set up by workers and plugged in. Looking around the buildings, I can see the changes that have taken place on this street since a few years ago. In addition to the fact that the main road is renovated, the side streets also look well-kept. It looked much worse when I lived in Piotrkowska about 13 years ago. (woman, returning home)

Many thoughts can come to mind while walking, but the students also noticed that slow walking, changing the body moves, changes their mood; they become gradually calmer. So, the body influences feelings. The students also were mindful that stopping and noticing breathing (sometimes slowly) can help them concentrate on what is happening in their minds and see the things around them from a unique perspective, occasionally close to a poetic view of the world (“I notice that the trees look a bit ghostly”).[7]

The park was lit, very quiet, and you could hear only the rustle of leaves. As I moved on, I tried to shut down my mind and not think about anything, but it was difficult during the hard days before. I thought about the tasks I had to do for my studies and the book I had started reading. I felt lost in thought. I started walking slower; I took my time. I got to the pond, where I heard the ducks. My dog saw them first, and I was drawn to them, which distracted me. I walked towards the little bridge, and there, I unconsciously stopped and looked into space. I started to breathe deeply and slowly. I felt that, and then I began to calm down and quiet my mind. I also felt as if the world had stopped. I remember when I was little, in this park with my mother and my previous dog, and I started smiling. (woman, free walking)

As I kept walking, I realized how empty the streets are on Sunday morning, as if the world had stopped for a while to get the energy for the coming week. I started to focus on my breath because I was losing my mind with many thoughts and couldn’t even focus on one at a time. On the other hand, I noticed I was walking fast, as if I was late for a meeting, so I reminded myself that I had no purpose for the walk, and that I could slow down and try to enjoy it, so I did. (woman, free walking)

I head towards the nearby park. I enter its grounds and step onto a path of poured asphalt on which there is still a layer of slightly melting snow. I try to relax, breathe slowly, and stroll through the park. I see a milky white, translucent mist in front of me. It feels like I’m in the clouds. I notice that the trees look a bit ghostly in these conditions. (woman free walking)

Sometimes, we can find a place we are attached to for a long time in the city. Our commitment to the site can come from the primary socialization period, when our parents took us to this place for walks. The place often gives peace of mind and is suitable for contemplation. However, when the site is reconstructed or liquidated, sadness, nostalgia, a sense of loss, and longing for a new “my place in the city” appear. The mood radically changes. The previous “my place” becomes alien and rejecting. The pathic voice emerges from the subject. The past as the lived time is evoked, and the scheme of the “personal city” (Majer, 2015) connects with the past:

Since childhood, I had one place in the neighborhood, which was a substitute for peace, nature, and greenery despite the short distance from the busy street. The hill is a place to go sledding, play with my dad, and contemplate in case of dilemmas or life problems. The hill was a sign that home was close by; it evoked a sense of security in me. Whenever I rode the tram passing by, I would look in its direction, my head reflexively turning to see it. I still do it. However, the hill is no longer there. For the past year or so, construction work has been taking place on the hill site in connection with digging the rail tunnel for the commuter rail network. The Lodz-Kozi-ny station is to be built there in place of the hill. Today, when I walked in the area of the hill and couldn’t stand on the site where it used to be, I felt sadness and disappointment. I have a feeling that lately, everything related to my carefree childhood, joy, and sense of security is disappearing... I wanted to regain peace, and I felt like an intruder. The big fence, the lack of paths, the mud, and the many stares from passers-by made me feel uneasy and a sense of loss. When there was a hill, I knew what to do with myself – climb it, sit down, watch the city life (fascinating, I love it). I didn’t know where to go; I was flitting around the fenced area. The branches of the tree snagged my head and tore off my hat. I felt that the place was driving me away, that it was no longer MY PLACE. It is OBVIOUS, bland, gray, drab, rejecting. I took my hat and stated that I was going away. I don’t want to stand here anymore; I feel bad here. (woman, free walking)

The students usually did not notice their bodies while walking. The body is given, and it is an unnoticeable subject. But it exists in the background of our thinking. Therefore, it is easier to see the body’s feelings when we have the instruction to observe what is going on in our body while walking. The students often also noticed that phenomenon, that it is easier to focus on the body when they have in mind such an instruction, especially when they have just been to a yoga class or meditation.

When walking under challenging conditions, the body can be more noticeable, and the low temperature outside can create such conditions. We concentrate on this condition. While walking, the students saw how the body becomes an interaction partner and how they are in dialogue with it:

Suddenly, I became aware of these thoughts and feelings, so I tried to return to the present moment in this more optimistic mood, but it was difficult because I was still freezing. I started thinking, “How will I survive this winter here?” My body and mind couldn’t focus on anything else, so after 15 minutes, I was back in the faculty. (woman, walking to university)

The body’s schema to react to some temperatures is a very stable element of our body’s reaction to the environment. The body schema is a sensory system that functions without awareness. The body knows first about the changes in the background, and the mind is next (Gallagher, 2005: 24; quoted in Tanaka, 2018: 224). Self-observation and reflection come when we are stimulated to do it. The student from Spain had such feelings about the body in the cold surroundings:

Then I started to analyze my tense body, which felt uncomfortable, probably because of the cold, but also because I needed to stretch. Some minutes later, I noticed I couldn’t feel my nose and hands, and my eyes almost cried because of the cold wind. Apart from that, my mind reminds me of the cold of the city and the empty streets, maybe not that empty. Still, it is different than in Spain, where I always see people, more than I usually see here; maybe it is just because I was focused on it, and it is just my perception, but it is how I felt it. (woman, going to university)

It is easier to feel the temperature if we come from a warm country and move to a frigid one, like Poland is for Spaniards, for example. The feeling of the body concerns the habitus of the sensing of temperature that is usually experienced in our hometown or home country. Suddenly, changing the country, we noticed how the body reacts. It happens when there is a drastic change in the surrounding temperature. The body is a part of the surroundings, and it is natural for us and is usually taken for granted. But when we recognize that we are in a different climate, we start to reflect, and even a nostalgic feeling emerges from the body.

Although it is initially difficult to understand what is going on if the experience with cold weather is new, it could also be refreshing and give a new perspective (“Like if I was being born again”). It seems like the body is cleaned, and the perception is renewed, the coldness becomes unimportant, the body adjusts to the weather, and a feeling of warmth appears. Interestingly, the warmness also seems to be in the mind. Another student from Spain expressed it in the following poem:

Cold weather

I don’t know how to feel,

either my mind or body,

everything is frozen in this cold weather.

But I keep walking

even if I can’t see anything,

I keep walking,

even if hope is left

behind,

I keep walking.

Then, at some point,

I don’t know how or when,

I see myself in a place

where the cold is still there

but I started feeling something else.

Like if I was being born again

I can focus on the outside,

I see everything with new eyes,

the colors, the wind, the snow…

my body is feeling warm again,

so, does my mind.

(woman, free walking)

People can feel temperature differently. This can be a surprise for some students, and they can doubt their senses; there could be challenges in understanding how the body senses temperature. Discovering that some people can feel temperature differently is quite a big surprise. It also provides a topic for reflection on the differences between the bodies:

When I got off the tram, all wrapped up in a scarf, a thick jacket, a scratchy wool sweater, and gloves, I ran into a young girl dressed only in a thin jacket, which was unbuttoned, and underneath, she had only a crop top. It was an amazing encounter for me because the girl did not look cold; she walked upright, and her teeth did not chatter. I just thought how amazing people can feel the same temperature differently. I was shivering like jelly in my combat gear, and she walked proudly with her head held high. This encounter stayed in my mind, and while walking around the Cathedral Square area, I just looked at people’s clothing. I wondered if it was me or if she was experiencing the temperatures incorrectly. Or maybe both of us? Or neither of us. (woman, report on being lost in the city)

Sometimes, the students felt something interesting would happen to them, and they could discover something new. Walking close to buildings allowed them to admire beautiful architecture and constructions. Even if they felt uncomfortable because of the cold, they enjoyed walking. The feeling of being powerful appeared and perseverance to walk and return to the destination:

The weather was still the same after my class, maybe a little warmer. I decided to change the direction of the walk and lose myself in the city to discover something new.

When I was walking, I realized that I tend to look at the ground when I’m walking alone as a way to protect myself from the rest of the people. So, I tried to look up at the beautiful buildings and constructions, and I felt more empowered with myself. (woman, report on being lost in the city)

As we have already mentioned, the research participants noticed a change in mood during the walk. However, it is connected with the feelings of the body and feeling the world through the senses (auditory sense; Pink, 2009). Senses give the feeling of presence and “it is mine”, my body belongs to me (“I started being aware of every part of my body. Every finger and toe, arms and legs, ears and nose are parts of my body! I felt them; they are mine, and I am grateful”). After some time of walking in anxiety, they relaxed. They started thinking about why they walk very fast; they feel it as time passes, feel the body, and feel grateful for all the positive things that come from walking. The noise is not unpleasant, and it is accepted. They can handle even the wholeness of the self and coherence with surrounding by walking in the city step by step:

I decided to get off the tram three stops earlier that day, so my way to university took about 45 minutes. After the first 10 minutes, I started feeling more relaxed. I realized that the slowness of my walk was pleasant. There was a chill in the air that day. For the first 10 minutes, I was (like always) the reason why I walked fast. Then, I realized that the chill on my cheeks proves that I live (does that sound crazy?). The longer I walked, the more embodied I felt. I became aware of every part of my body. Every finger and toe, arms and legs, ears and nose are parts of my body! I felt them; they are mine, and I am grateful.

During the second part of my walk, I started acknowledging the environment’s influence on my body. I am a person who reacts badly to noise and every strange sound. But after taking my headphones off, the sounds started being one coherent whole (which was pleasant). Sounds of urban life can be annoying – dogs barking, cars passing by, people talking loudly, and trams emitting loud sounds. But it is okay. I started to accept it and take it as a coherent whole. (woman, going to University)

The body also senses smells and hears sounds, so they could be an incentive to return to the memories and feel nostalgia. The lived time is evoked by the senses, and it is visible in the description below:

Someone in the neighborhood uses a coal-fired stove, and the smell reaches everywhere. If I had to describe the scent of winter, it would be the smell of these stoves in my village. I hear a skein of geese flying overhead. I am cruelly cold, even though we have a mild winter.

This place had lost its original meaning for me but gained a new one; when I went to this forest edge, I suddenly sank into my memories, mostly good ones, completely forgetting everything wrong that happened to me afterward. It didn’t matter then; I suddenly longed for the years when everything seemed more colorful. (woman, self-description of favorite place)

The students felt the smoke and smell from the car fumes, and some tried to breathe not so deeply to avoid inhaling this polluted air. It happens on the way to university and back; nothing changed over the course of the day:

I try to breathe as little as possible because the cars standing in traffic fill the whole street with smoke…

I can smell the fumes wafting from the car, and I can see the traffic jam piling up; I can also smell the cigarette smoke of passersby – again, I try to breathe as little as possible. (woman, coming home)

The problem with breathing in the polluted air also happens while free walking. And one of the tactics is to avoid inhaling that dirty air, short breaths and short walks:

I inhale the air; I can smell the smoke from the chimneys of the people living next to the park. At this time of year, when the temperature outside remains very low, I find that brisk walks or short breathers are preferable. All because of the omnipresent air pollution, the smoke from coal or wood-burning ovens. And worse still, the occasional habit of burning rubbish makes me nauseous. (woman, free walking)

Another sense was also essential to feel the city – hearing. Some students also found boisterous streets to be places they disliked. They try to avoid such roads and feel comfortable. Narrow streets could be dangerous because of the puddles that are splashed on the walkers (the sense of touch starts to operate):

Finally, I turned onto Pilsudski Street. Again, it isn’t quiet here. Several trams are passing by. Many cars stand waiting for the green light. I feel overwhelmed by the number of stimuli; it is noisy, and there are many people. I walk faster because of this. I get hot again and feel uncomfortable. Fortunately, I quickly turned onto Politechnika Street. I like this street very much, so I feel comfortable on it. The sidewalks are uneven, but I cross to the other side where Poniatowski Park is located. There is a comfortable sidewalk here. (woman, going home)

The body can be separated from the mind, and senses are suppressed by using technology while walking. The feeling of presence could be limited by the technology. Listening to music through headphones can focus the attention on separate worlds rather than on the direct surroundings. It can be an obstacle to walking mindfully. This obstacle comes from us, from our everyday habits. We cannot enjoy walking fully because we are in different places in our mind and imagination. We can also experience a shock filled with emotions when we suddenly don’t have a noise in our ears, but we will listen to and see what we are going through. Emotions appear when distractions are gone. The perception of time can also be disturbed, and it can be challenging to feel the passing of time clearly (lived time):

The words of Andrzej Tucholski (a business psychologist who publishes his thoughts online) were the impulse to take my headphones off, and after I tried, I was terrified of the silence and the appearing emotions.

That is why I was scared of doing that homework.

I am used to putting my headphones on immediately after going out to university or home. It is a habit. It was no surprise that leaving my headphones at home (on purpose) caused nasty feelings. During the first 10 minutes or so, I was feeling anxiety and stress. My mind was stunned, and my whole body was shocked by the lack of a simple device. I do not remember that first 10 minutes clearly. I could not observe because my body was tense, and my mind was foggy. I remember walking fast, but I felt that University took more time than usual. (woman, returning from University)

The sounds of nature are boring, and the mind and body need the other sounds, music. Listening to music while walking is a habit:

Passing the park, I notice all the leaves have already fallen. It has become a bit depressing as long as there is no snow. I’m starting to feel tired of the journey and bored with the lack of music. (woman, walking home)

During bad weather, for example, while it is snowing and there are low temperatures, slush and water could be on the street. It can create the problem of being splashed by slush and water from the wheels of the cars going through puddles. The body is a concern in this situation of encountering obstacles while walking. The mind collaborates with the body and wants to protect it (the lived body):

The temperature is close to 0°C; it’s pretty cold, which is excellent for me. Like always, in such weather, people are shaking, rubbing their hands, and trying to heat up a bit; luckily, I don’t have such problems. Unfortunately, the road I’m walking on has more slush than snow; hence, I don’t feel the pleasant, crunching sound made by snow, but I feel like I’m drowning in a swamp or quicksand. At one point, a car was driving dangerously close to me, and I had to jump away from the road to avoid getting splashed. It worked, but I landed in deeper sludge, which made my boots messy, and the thought of cleaning them after only a few days made me sigh with resignation. (man, free walking)

It is possible to describe the experience of walking by writing a poem. I wrote a poem in December 2022 about the temperature while walking. It shows the importance of the senses and feelings of the body. I felt the smell of the smog that has been killing the people in my city. Observing the inner life and outer life is possible while free walking; the intention decides:

Walking in the city

Sounds of the city

come with the smell of the Deathworld.

I am touching the earth,

my feet hurt,

my fingers are frozen,

my eyes are watering,

nearly not breathing.

The noise of the lifeworld.

Wheeze.

Am I still alive?

I touch the branches of trees.

Jay on the tree.

He is observed.

Somebody walks in silence

in the foggy December.

While walking, we sometimes encounter obstacles. In this situation, the body becomes a concern. Pedestrian traffic (sometimes renovations of the street also become an obstacle) can be an issue – to avoid bumping into other people and keep the speed of walking:

Unfortunately, it’s difficult because I have to, on occasion, avoid people who are walking in the opposite direction. (woman, going to university)

Speedy walking is often connected with going to University or work. It is a body schema that is associated with this kind of walking. There is a lot of attention on obstacles on the sidewalks to avoid crashing into people or any obstacle that can slow down the walk:

I looked at the watch to see how much time I had to get to the bus – it was 1:50 p.m., and I had a bus at 2:01 p.m. It wasn’t a big distance from my home to the bus stop, but I felt like I couldn’t walk like a zombie; I needed to speed up, so I started to walk faster – I felt like my heart started beating faster and faster. All the people around me, as always, thought that they were the only ones on the sidewalk, so I felt irritated because I needed to avoid them like obstacles, and I was worried that I might miss my bus. (man, going to university)

Encountering animals can also be an obstacle that sometimes appears with other obstacles, such as cars going at excessive speed. The students wanted to protect their bodies as much as they could:

Going to the forest in the alley next to me, I met a few wild boars, which also scared me a lot, but I managed to avoid them with a calm step and go ahead. (man, free walking)

Observing others in public places comes naturally and is usually taken for granted. Other people are a certain constant in the urban landscape. Are they essential for walkers? We do not know them personally. In general, events and people who stood out from their surroundings were noticed, and it was usually surprising for the observer:

I pass the liquor shop where an adult woman came out earlier, carrying beers in her purse. I glance down at her shoes and notice the ankle monitor. I think about what might have led to her having to wear it. I walk a few more steps and see that the same woman comes to the gate of my tenement and opens it, slightly holding the gate for me. I thank her and think that this is probably the same woman who shouted at her partner in the middle of our townhouse courtyard a few evenings ago; I feel embarrassed. So, I quickly enter the stairwell and go to the flat. (woman, returning home)

The memory is activated to arrange the interpretation of a person’s observation (see above example) into a comprehensible whole that conforms to generally accepted interpretive schemes, such as who could shout at his partner at night in the middle of the yard. Answer: A person wearing an ankle monitor.

Another example of events with people is connected with astonishing incidents. For students from warm climates (for example, Spain), it is surprising that some people are almost naked in freezing weather, such as during the autumn in Poland.

Gazing at others invokes uncomfortable feelings (Goffman, 1967); people in the city try to avoid direct and prolonged gazing at others to avoid embarrassment:

And last, I mention a man I saw in a window. He was shirtless and shaking his hands through the window with his entire arms outside; it looked like he was trying to shake something off. I couldn’t think of anything else but, ‘Isn’t he cold?’ I found the situation funny; he saw that I saw him from afar, and he also stared at me. Then I stopped looking, not to make him uncomfortable, but I was left with this image of a half-naked man in the window shaking his hands in this cold weather. (woman, free walking)

Usually, while lost in a city, helping others appears. However, the aid seems to be when the lost person is active and asks for help. At least, that is what it looks like in Poland. I remember that in Japan, people help when somebody looks around in the metro and does not know where to go. But in Poland, it is different; the initiative should come from the person needing help.

In both situations, the lived relationships come with the category of helping others. We should also notice the pathic dimension of these relationships:

At first, I was deeply frightened by the lack of a device at hand, which I always needed. I remember leaving the shopping mall and looking for a suitable stop. I wandered a lot, hit the wrong stops, and finally found the right one. While standing there, I checked the hours of the bus that was supposed to take me to the station; I asked people nearby about the time and whether they would get to the same place. Thanks to this, I met a girl whose name I no longer remember, but her destination was the same as mine. Her presence made me feel inner peace and start to feel safer. When the right bus arrived, we got on together and sat down. The girl said she would let me know when we would get off, so I didn’t have to worry about anything. We talked all the way, and it turned out that she knew my friends, which made me a little inexplicably happy. (man, report on being lost in the city)

Sometimes, the reflection about being lost appears in more general terms, and the students thought about others who might be lost and in a more difficult situation than someone relatively close to their home city. What can people feel when they are far from home and have lost their homes entirely, as happens during the war and among refugees? Lived relationships are experienced here imaginatively but with deep pathic feelings:

Being lost is an extraordinary emotion. You are somewhere, but you don’t know where you are. Everyone seems suspicious, and you must have eyes on the back of your head. Now, I am thinking about the Ukrainian people who came to Poland to shelter from the war. I feel huge compassion for them and their kids. They probably don’t know any of us; they don’t know where they can get any help. They must start all over again. I was lost only in Warsaw, about 100 kilometers from my home. What can people feel in a different country, thousands of kilometers from their real home? I can’t even imagine how traumatic a situation they have. (woman, report on being lost in the city)

We have many examples from literature and philosophy that walking is a significant incentive to reflect on the world and self. A sequence of thoughts emerges based on the reviews that appeared while walking. Great ideas sometimes emerge during a walk, and we also wonder about what we experience, as happened when Fredrich Nietzsche was walking in the Alps (Kaag, 2018). The same is true with Rousseau, Thoreau (Gros, 2021), and Wordsworth (Solnit, 2008; see also Coverley, 2012). The feelings of freedom and the greatness of nature appear and provide an incentive to reflect on the relation of self to nature and eternity. We can also reflect on the current civilization that limits walking and how walking, especially city walking, developed in the context of urbanization and technology development and generally under high capitalism (see Benjamin, 1997). We should remember that the love for nature and walking went together with the new esthetical needs of the Western culture (Solnit, 2008).

Students had such impressions, and while their reflections may not be on the same philosophical or artistic originality scale, they touch on essential and often ultimate issues.

They expressed the satisfaction that walking gave them, even when lost in the space, as they were able to look with fresh eyes at the new surroundings, see new things, admire the city’s beauty, or meet other people. The feeling of self-acceptance can appear. The person gives self-indications and converses with him/herself as if they were with another person to get respect; there is a lot of self-learning about “Who Am I?” Self-identity-work starts when we are lost and walking:

I kept walking and walking, trying to recognize something, but everything was new: the buildings, the people, the murals, the birds, the trees – everything was so beautiful. I love the first time you visit a place and look at everything with new eyes. I can’t remember my body’s feelings, but I was calm and comfortable in my mind and body; I also remember having thoughts like “Where am I? Am I sure this is the way?… Okay, relax, there’s no problem at all if you get lost you can always check your phone or ask someone, you can relax.

Sometimes, I speak to myself as if I were another person; that way, it’s easier for me to treat myself with respect and patience because I tend to be hard on myself. (woman, report on the topic of “being lost in the city”)

Being lost in the city is an incident that pressures us to act and reflect, and it naturally appears. The self is once again discovered, and we regain consciousness of it. There is some excitement in finding the way back, which can be why I am proud of it. The case of being lost is treated as a game where we can check our skills and abilities to navigate the city without the maps. There is also checking the emotional composure of the person and the rational way of solving the problematic situation. It is treated as an exciting experience, showing that there is always a solution in difficult situations:

Fortunately, on that second try, I got it right and managed to get to the street. The feeling was very, very relieving. I felt great satisfaction, and it was all worth it and a great experience for me. I felt proud of my orientation, and in the end, it was a fun and exciting experience. I hadn’t been lost in a long time (until now, maps have solved everything for me). I enjoyed the “challenge” and remember feeling adventurous during a “trip.” For me, being lost, in general, is something that I enjoy because it feels like a game, and even when it’s a bit problematic, in the end, you still have to get out of there, so it is interesting for me to see how to manage to do so. I feel like I’m testing my calmness and decision-making, and I can always learn something from it. (woman, report on being lost in the city)

While free walking/traveling, mindfulness appears, and some reflection follows.[8] Thanks to the mindful walking in the city and the instructions that I gave to the students to be constantly aware and be detailed observers, they could change their attitude toward the difficulties of returning home from university. Depending on the interpretation, they could vary their view and see that small things can be pleasant. The transformation of how we view some parts of the lifeworld becomes more accessible when we are mindful of the surroundings that we are walking through. The world is created by our perceptions and feelings that follow some points of attention:

Now I can see how different the way to university and back from university are. It all depends on my mood, weather, and area. I have never explained that deeply about my way to university. It was just a simple, daily activity for me. Now I know that I want to change it a little bit. The anger that accompanied my way home was unnecessary. I have to study how to enjoy little things. I could think, “Oh, the train is very crowded, but I am young, and standing isn’t a problem. The free seats are needed more for older people.” I also have to change my way of thinking; I should be thankful that I can study, travel by train, and go back to my own house, where somebody is waiting for me. (woman, returning home)

Some students even changed their attitudes to their health problems and became calmer. The changing mood happened with observation and enjoying the beauty of nature (the park). The grey colors of nature during autumn were connected with the “gray mood” of the student. The acceptance attitude appeared:

I wasn’t feeling perfect. The night before, my sugar levels were crazy, which gave me a headache and weakness for the day, and I was focusing my mind on it for a long time during the walk. Complaining about my health problems, feeling tired and hopeless, sometimes I have days where I feel I cannot take it anymore. Then, I started to be gentler on myself and remind myself that I’m doing my best, even if some days don’t go as expected; that’s life. When I became more positive, I was going through a lovely park. I don’t know which one it was or where I was, but it was beautiful; I’d never been there. I began to focus on the colors and how quickly they changed. Now everything seems more grey, neutral, as if the colors were losing their power… I thought, “Wow, today I’m feeling the same – grey and colorless.” But instead of trying to quit those emotions and feelings, I stayed with them; I felt them as they passed. (woman, free walking)

The same student felt the effects of mindful walking (walking meditation in the park that we did together), which was a better reception of the senses, for example, the smell. The senses also give the impulse to act. For example, when we felt the aroma of bread, we decide to go to the shop and buy some:

When I crossed the park, I felt a little better inside, but my body was telling me it needed some rest, so I started to go back home. I was glad that I had gone out for a while and gotten some fresh air, even though, on the other hand, I would have preferred to stay home. As I was getting home, I smelled coffee and bread from a nearby bakery, and that made me remember that I had to buy some bread, so I did. I love bread, and the smell was amazing inside the bakery, similar to toasted cereals. I bought a whole grain loaf that looked so good. And finally, I got home, tired and sleepy. (woman, free walking)

Contemplation on life also appeared, especially while free walking. When somebody stands still and thinks about life, the self-observation about the feelings here and now can be a general introduction to contemplating life. It happens during mindful walks. The feeling of the body and focusing on nature and the surroundings make one admire the world that is passing by:

Despite the strong wind, there was also great peace there. There were no people, no streets, no sound of cars, only nature itself and me. I stood there for a few minutes, staring at the water, the surrounding grass, and the trees in the distance of the field, and I reflected on my life and reminisced about many of my rallies and my life’s failures.

It was approaching 11:00 a.m., so I began to walk along a dirt path, where I walked on slightly damp grass. Thanks to this grass, I also felt a closer attachment to nature; I felt as if my feet were growing into the ground. I also passed fields that will grow corn or some other grain during the holidays. Finally, I reached the stables, where horses are usually free to roam, but they were closed as it was winter. Despite everything, I could admire the stables, the vast paddock, and the forest house with a straw roof. (man, free walking)

The body resonates with the surroundings while walking, mainly through the senses. But to resonate, both it and the mind should be open to observing the interaction with external objects. They become part of the subjectivity because the body’s feelings coproduce the emotions with the mind and react to things. The subject becomes part of the space and time in a particular situation. It is not easy to differentiate the self from it. Time is blurred, the city’s noise is accepted, the body is felt, and the feeling of relaxation appears. The resonance (Rosa, 2020) occurs on the subjective level, contemplating relations with self, other people and surrounding. The interaction with objects (buildings), nature (trees and animals), and other people becomes part of walking if the mind perceives it. The pathic relations appear, and various emotions change from annoyance and irritation to calmness and relaxation. However, first is the motivation; the person should want to perceive it and be open to what is coming from outside and inside. Although the distinction between outside and inside is artificial, everything outside has a definition of being external and should be perceived internally as such it is. Shogu Tanaka wrote the following about walkers walking and interacting with the environment:

Although “I can” walk in the street without any deliberation, there are numerous potential procedures of bodily movements to be performed in this action – how firmly to kick off the ground to step forward, how to keep the trunk straight while moving, how far to make one’s strides, at what tempo to swing the arms, and so on. In addition, all of these procedures must be adjusted according to environmental changes such as hills or ramps, curved paths, slippery surfaces, other pedestrians, and traffic signals. (Tanaka, 2018: 224)

During this interaction, the subject’s mood alters. There are two kinds of mood changes. One is gradual, the other abrupt. The temporality is expressed here by the lived time of the mood. The gradual change is connected with the slowing motion of the body; the abrupt change happens when our actual perception of the object is very different from the perception from the past. The changes in mood are always connected with the feelings of the body based on the senses’ receptions, and the “body schema” matters in this change: “body schema is a system of sensory-motor capacities that function without awareness or the necessity of perceptual monitoring” (Gallagher, 2005: 24; quoted in Tanaka, 2018: 224). The body schema adapts the self to the space and object, but it has the same potential for modification based on the surroundings. Hence, the modification comes with feelings and emotions, which also can change. The perception comes from body schema: “It also adjusts the whole bodily action in correspondence to the ongoing environmental changes (which implies that the body schema is also operating as a perceptual system). And thus, as a body-as-subject, ‘I’ appears in the world with the mode of ‘I can’ before ‘I think’” (Tanaka, 2018: 224).

The importance of body schema was noticed in our research during the adjustment to the temperature of the air (cold weather), i.e., how it is difficult to do anything in such temperature, and how the body must send signals (by thermoception, the sensor that detects temperature) to the subject.

The body schema is connected with the type of walking. If we go to school, we are usually very fast, walking is speedy, and we are worried about being on time. However, the schema of the body in free walking has different speeds of walk. Generally, in free walking, we can stroll. This kind of walking also allows us to be more mindful and feel the being of here and now because we can focus more on the senses that perceive the world.

Finally, based on the inference from the self-descriptions of the research participants, we can list the basic features of walking in the city. Some of these features are characteristic of mechanical walking; body concerns or pathic dimensions appear but are not mindfully perceived or reflectively elaborated. However, we can perceive and reconstruct these features by being mindful and doing self-observations:

The senses operate while walking. Sounds and smells are essential, evoking memories and thoughts connected with past experiences in the particular space of the city (lived time). We can have a specific relationship with some parts of the town (lived space). The city space is evoked in the experience, usually in pathic mode. The city can be created as a “personal city” (Majer, 2015). It becomes ours or foreign in our experiences, and the lived body plays a vital role in our commitment to the space.