https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8198-9900

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8198-9900AGH University of Krakow https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8198-9900

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8198-9900

Abstract:

People with disabilities during the COVID-19 epidemic were particularly vulnerable to information exclusion, e.g. press conferences were not translated into PJM, there was no information in plain language, etc. In addition, restrictions were introduced on social contacts and the possibility of carrying out previous activities and using the support of volunteers or assistants. This made social media an important tool during the COVID-19 pandemic for people with disabilities as it often provided a way to connect with a wider community, maintain social relationships, and obtain information about the epidemic and the restrictions being imposed. The aim of the article is to demonstrate the significance of social media during the COVID-19 pandemic in Poland from 2020 to 2021 for people with disabilities. This will be facilitated by netnographic research, which will be based on the analysis of content published in 10 Facebook groups for people with disabilities between March–April 2020 and December–February 2021.

The results of the research indicate that social media played an important role for people with disabilities during the crisis situation of the pandemic. Analysis of the content of social media group profiles showed that they provide a space for seeking and exchanging information, sharing concerns, seeking support, and fighting for their rights by people with disabilities.

Keywords:

social media, disability, COVID-19 epidemic, isolation, exclusion

Abstrakt:

Osoby z niepełnosprawnościami w okresie epidemii COVID-19 były szczególnie narażone na wykluczenie informacyjne, np. konferencje prasowe nie były tłumaczone na PJM, brakowało informacji w języku prostym itp. Dodatkowo wprowadzone zostały ograniczenia w kontaktach społecznych i możliwości realizowania dotychczasowych aktywności oraz korzystania ze wsparcia wolontariuszy, asystentów. Sprawiło to, że w tym okresie istotną rolę odegrały media społecznościowe, które często były jedyną możliwością kontaktu z szerszym otoczeniem oraz własną społecznością, a także stanowiły miejsce, gdzie można było uzyskać wsparcie, podtrzymać relacje społeczne i otrzymać informacje dotyczące epidemii i wprowadzanych ograniczeń.

Celem artykułu jest ukazanie znaczenia mediów społecznościowych w okresie epidemii koronawirusa w Polsce w latach 2020–2021 dla osób z niepełnosprawnościami. Przeprowadzone badania netnograficzne oparte zostały na analizie treści opublikowanych w dziesięciu grupach skupiających osoby z niepełnosprawnościami w okresach od marca do kwietnia 2020 roku i od grudnia 2020 do lutego 2021 roku na portalu społecznościom Facebook.

Uzyskane wyniki badań wskazują, że media społecznościowe w czasie sytuacji kryzysowej, jaką była pandemia, odegrały ważną rolę dla osób z niepełnosprawnościami. Analiza treści profili grup na portalach społecznościowych pokazała, że stanowią one przestrzeń poszukiwania i wymiany informacji, dzielenia się obawami, poszukiwania wsparcia oraz walki o swoje prawa przez osoby z niepełnosprawnościami.

Słowa kluczowe:

media społecznościowe, niepełnosprawność, epidemia COVID-19, izolacja, wykluczenie

On March 14, 2020, a State of Epidemic Emergency was declared in Poland (Official Journal of Laws of 2020, item 433). This was followed by the implementation of an Epidemic State on March 20, 2020, as per an ordinance issued by the Minister of Health (Official Journal of Laws of 2022, item 340). The restrictions imposed during that period to curb the spread of the virus applied to everyone, irrespective of age, gender, competence, or fitness. Such significant restrictions on mobility, activities, and social contacts have disrupted daily life (cf. Kocejko, 2021; Kocejko, Bakalarczyk, Kubicki, 2021). Although the effects of the epidemic impacted everyone, the social consequences varied from person to person (cf. Robinson et al., 2020; Dobransky, Hargittai, 2021). The COVID-19 pandemic has worsened social inequalities and further marginalized the already vulnerable social categories (cf. Chanda, Sekher, 2020; Patel et al., 2020). It also exacerbated the problem of digital exclusion, which was further intensified by the lack of support in this area throughout the pandemic (Nguyen et al., 2021).

People with disabilities were especially disadvantaged (cf. Armitage, Nelums, 2020; United Nations, 2020; Kocejko, 2021). Compulsory isolation has severely limited the ability of this social category to access healthcare, education or employment and to participate in social life, thereby restricting daily interactions (cf. Boyle et al., 2020; United Nations, 2020; Kocejko, Bakalarczyk, Kubicki, 2021). This disruption has impacted the functioning of people with disabilities and contributed to a heightened sense of isolation (cf. Banerjee, Rai, 2020).

In response to the imposed restrictions, much of the activity during the epidemic period took place online. People worked and studied remotely, participated in video conferences, and used social media (Dobransky, Hargittai, 2020). The Internet allowed them to access information about the COVID-19 pandemic, share it, and interact with others about it (Dobransky, Hargittai, 2020; 2021; Nguyen et al., 2021). This was particularly important for people with disabilities, since messages broadcast in traditional media (the television, press, and radio) regarding the restrictions and safety guidelines during the epidemic were not accessible to many of them (cf. Kocejko, Bakalarczyk, Kubicki, 2021).

Ongoing studies show that social media played a significant role during the COVID-19 pandemic (Dobransky, Hargittai, 2021; Nguyen et al., 2021). In this light, my objective is to present the significance that social media had for people with disabilities in Poland. Analyzing the content posted on Facebook during the epidemic will help me reconstruct the role which social media played for people with disabilities in Poland during that period.

The importance of social media in crisis communication had been studied prior to the outbreak of the 2020 epidemic. This topic was explored in a study by John Morris, James Mueller and Michael Jones (2014), which demonstrated that public entities fail to effectively utilize social media during times of crisis. However, as revealed by the researchers, crisis communication strategies should incorporate social media to disseminate official information and publish announcements regarding available support and assistance. This is particularly significant for deaf respondents, as they were found to be the most inclined (among all study subjects) to utilize social media for receiving, verifying, and sharing information related to emergency situations (Morris, Mueller, Jones, 2014). Other studies revealed that in the event of disasters, public entities seldom utilize social media to communicate and spread information. This can lead to dissemination of false, unverified, and potentially hazardous information (Alathur, Kottakkunnummal, Chetty, 2021; Alathur, Pai, 2023). Published studies have also highlighted the challenges associated with accessing online content (Kent, Ellis, 2015; Ellis et al., 2019). Furthermore, they have indicated a scarcity of accessible information and ineffective communication between organizations and individuals with disabilities. These factors have hindered crisis management efforts among people with disabilities (Hay, Pascoe, 2019).

Despite these limitations, the COVID-19 outbreak demonstrated the crucial role of social media during this health crisis. Social media usage enabled people with disabilities to remain up-to-date about COVID-19, share relevant information, and engage in diverse interactions on the subject (Nguyen et al., 2021). People with disabilities were more likely to use social media to share information about the COVID-19 epidemic, interact with others, and support one another in coping with the effects of the epidemic (Dobransky, Hargittai, 2021). This was particularly significant for individuals with sensory disabilities (Dobransky, Hargittai, 2020). During the pandemic, people with disabilities also engaged in community-building activities and anti-discrimination efforts in social media to improve the situation of people with disabilities (Żuchowska-Skiba, 2021).

Research indicates that the ways in which people use the Internet, social media, instant messaging, and online gaming were prone to significant changes during the COVID-19 pandemic. These modalities were used as a new means of interaction between friends and family (Nguyen et al., 2021). This includes people with disabilities, who, even before the epidemic, had been able to establish and sustain relationships online (Dobransky, Hargittai, 2016; Masłyk et al., 2016; Lin, Yang, Zhang, 2018), form communities, and connect with those who shared their interests and needs via virtual communities, forums, and profiles (Goggin, Newell, 2003: 132; Żuchowska-Skiba, 2018). Moreover, the World Wide Web provided a sense of connectedness and enabled individuals to engage with communities that brought together people with similar experiences and challenges (Wright, Bell, 2003). This helped alleviate the feelings of isolation and alienation among people with disabilities (Poppen, Bradley, 2003; Goggin, 2015). That, in turn, made it possible for those at risk of social exclusion and for marginalized individuals to actively participate in public life (Burke, Crow, 2017; Huang, Wang, 2023).

Social media facilitated the search, acquisition, and exchange of information or knowledge (cf. Kent, 2020). They provided a platform for people to find experts on specific health issues (Wright, 2016) as well as to self-organize and seek mutual aid (Klemm et al., 2003; van Uden-Kraan et al., 2008; Verdegem, 2011; Stojkow, Żuchowska-Skiba, 2014; 2015). They also provided an opportunity to find support (Goggin, Newell, 2003: 131–132; Kampert, Goreczny, 2007) as well as enabled people to express their emotions (Shoham, Heber, 2012) and build relationships while participating in informal groups that brought together individuals from diverse backgrounds (cf. Kent, Ellis, 2015; Juszczyk-Rygałło, 2018; Huang, Wang, 2023). Social media also fostered a sense of belonging to a community of people with similar experiences and helped mobilize and strengthen the participation of individuals with disabilities in political and public activities. This was achieved by providing an opportunity for symbolic support, such as adding an overlay to one’s profile picture to express agreement or demonstrate disapproval (Li et al., 2018). Unfortunately, social media also became platforms where individuals with disabilities were exposed to misinformation and content potentially harmful to human health (cf. Alathur, Pai, 2022).

This highlights the significant potential of social media in crisis situations for establishing inclusive and effective communication for individuals with various disabilities, which justifies the necessity to examine the significance of social media during health crises for individuals with diverse disabilities. To date, research has concentrated on decoding patterns of social media usage and identifying disparities between the general population and individuals with disabilities in terms of their social media usage during the pandemic (Dobransky, Hargittai, 2021). My objective was to reconstruct the posts published in social media groups in order to ascertain what type of content held significance for individuals with disabilities during the pandemic.

I studied ten Facebook groups that brought together people with various types of disabilities. Two of them addressed people with hearing disabilities, two of them with visual disabilities, two targeted those with motor disabilities and the other four groups had users with any type of disability. For the study, I selected groups that had been active since at least 2017, specifically targeted individuals with disabilities (as indicated in each group’s description) and which had a minimum membership of 200 people during the study period. Additionally, I focused exclusively on groups that had a minimum of one published post per day throughout the study period.

Due to the fact that the study subjects belonged to virtual communities of Facebook groups, I decided to use the netnography method. This approach has already been used by researchers to analyze the activities and utterances of people with disabilities and their families in social networks (cf. Smieszek, Borowska-Beszta, 2017; Smieszek, 2021), and to study the formation of online communities (cf. Roland, Spurr, Cabrera, 2017). In this light, my objective is to reconstruct the role that social media played for people with disabilities. For this purpose, I analyzed the content of posts that appeared on Facebook group profiles during the COVID-19 epidemic. In the course of the analysis, I wanted to answer the following questions: “What kind of contents was posted in Facebook groups?”, “What kind of contents generated discussions in Facebook groups?”.

Responses to the above questions enabled me to categorize the content that was most commonly shared in Facebook groups, revealing the activities and topics that held significance during the pandemic for individuals with disabilities. I was familiar with the groups under study, as I was their participant. I published posts or commented on the content being published in the period preceding the study and maintained interpersonal relations with the community members. During the period of study, my involvement was limited to observing and collecting posts, but I remained responsive to questions directed at me by group members. This has influenced my adoption of an emic perspective in my ongoing research. Therefore, throughout the study, I simultaneously adopted the roles of both a participant in the virtual community and a researcher. I did not explicitly emphasize my profile as one of a researcher, but I provided details about my workplace and its nature in my profile description (cf. Headland, 1990; Zielińska-Pękał, 2014). I decided to fully anonymize the respondents’ data. During the analysis and presentation of results, I refrained from quoting people’s statements and avoided using the names of Facebook groups or the nicknames of those who posted.

Eight of the groups under study were private (requiring approval from an administrator to join). As I was a participant in these groups and aimed to observe and analyze the published contents, I sought permission from the administrators of each group to conduct the study using the netnographic method. The administrators, after reading the description of the method and learning about the purpose and scope of the study, were assured that it would be anonymous and that neither the names of the groups nor the nicknames of their users would be published. With this understanding, all of them agreed to allow me to collect data from the profiles they were administering.

The two remaining groups were public, and although the posts were freely accessible to anyone, I still requested permission from the administrators to observe and analyze the content posted by users. In this case, I obtained the permission, too. The observation of the Facebook groups was conducted in two stages. The first stage covered the period from March 25 to May 4, 2020. That period was associated with restrictions limiting social contacts and free mobility, except for specific situations related to professional duties or volunteer work (cf. Official Journal of Laws of 2020, item 522). The second stage covered the time from December 28 to February 1. At that time, Poland had implemented restrictions mandating social isolation due to increased incidence rates, leading to a significant shift toward online activities. These restrictions imposed limitations on people’s mobility and social contacts between individuals outside the household (Przedłużamy etap odpowiedzialności…, 2020). During this time, I collected a total of 2,352 entries. I categorized the posts and performed the analysis using Maxqda, a qualitative data analysis program.

Through this analysis, I identified eight main thematic categories of contents published by individuals with disabilities in the Facebook groups under study. During the pandemic, the posts in these groups addressed the following issues: (1) functioning within the community and establishing or maintaining relationships; (2) sharing information about the epidemic; (3) the issue of discrimination; (4) digital exclusion; (5) social security, including access to benefits and services; (6) self-esteem; (7) self-determination; and (8) daily functioning and access to assistance in meeting one’s needs. These categories covered almost the entire collected material. Entries outside of these categories did not exceed 2% of the entire material collected in either the first or the second study stage.

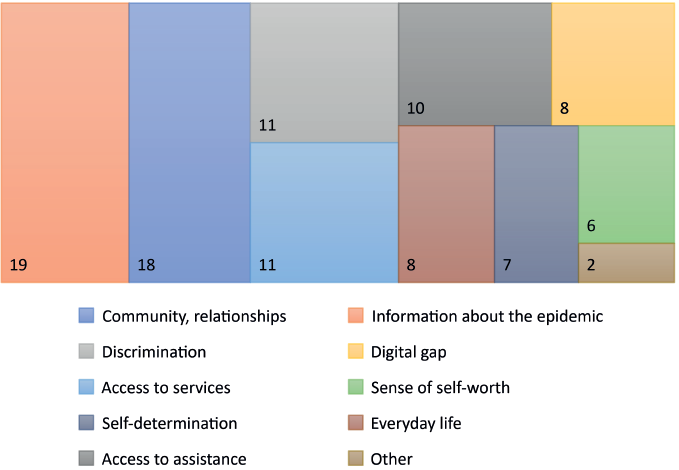

Analyzing the content of the utterances reveals that during the initial phase of the epidemic (March–April 2020), the majority of the information posted in Facebook groups revolved around the epidemic, the virus, and the restrictions imposed by the Polish government to mitigate the spread of disease (cf. Figure 1). This category included information regarding the incidence of COVID-19 in Poland and around the world, ways to mitigate the coronavirus risk, and the risks associated with comorbidities that could lead to a severe course of the disease. Facebook group members shared information about the directives or referred to other media sources, such as Twitter or the government’s website dedicated to the epidemic. This allowed others to learn about the regulations being introduced. The groups also frequently shared memes, funny comic strips, movies, and puns that humorously commented on the restrictions imposed by the authorities or made amusing references to the epidemic itself and the coronavirus.

Figure 1. Categories of content in Facebook groups during the period of March 25, 2020, to May 4, 2020

Source: own research.

This category also included articles shared by the profiles under study, videos explaining the causes of the coronavirus outbreak and how it works as well as simulations illustrating the spread of the epidemic. There were numerous conspiracy theories, including the one about the supposed threat from 5G networks. Entries in this category were often followed by a significant number of comments and reactions. This demonstrates that these entries have generated interest among the individuals comprising these communities.

Entries reporting on the introduced restrictions and describing the epidemiological situation were most commonly observed in groups that brought together the Deaf and hard-of-hearing community members. This was due to the fact that press conferences on the epidemic and the implemented restrictions were not being translated into the Polish Sign Language (PSL). Therefore, users posted videos in PSL, explaining the restrictions or demonstrating how to sign terms such as “coronavirus,” “quarantine”, etc.

Relationships and communities were frequently discussed during the study period. Study subjects engaged in conversations about building or maintaining relationships within their communities. They shared comments under posts and expressed their opinions on games, movies, books, and television shows. Topics related to past experiences in social relationships were also popular, as well as jokes about remote work, online relationships, and medical advice provided over the Internet. Groups for the Deaf and hard-of-hearing would share videos that allowed people to discuss important community-related issues in the PSL and enabled members to express their opinions. This facilitated the building of relationships within the community. A significant number of study group members participating in the discussions used overlays to ask others to “stay home and maintain social distancing.”

During this epidemic period, there were posts reporting discrimination against people with disabilities. Most such contents appeared on groups for the d/Deaf. Users described issues related to accessing healthcare services and aid organizations, as these entities relied heavily on phone communication and did not provide support through instant messaging systems. There was also a shortage of the Polish Sign Language interpreters at hospitals and in test swab collection facilities. This shortage was evident in posts published in the group, where users asked for explanations regarding the swabbing procedure and how to obtain the results.

Between March and May, numerous entries addressed the issue of digital exclusion. Users expressed their beliefs that reliable Internet connection and high-quality devices are essential for work and education. The respondents shared their own solutions and the software they were using. They offered to help one another learn how to use various features of social networks, instant messaging systems, and online work or education platforms. There were also numerous requests for donations or support in purchasing computer equipment for the participants or their children. These inquiries were typically answered by respondents.

Many statements referred to the availability of benefits or assistance, mostly regarding the challenges of accessing medical aid for rehabilitation and coping with daily life without the support of certain institutions that had been utilized by people with disabilities before the pandemic. Users described their negative experiences with telephone appointments with physicians, expressing their frustration over the inability to access rehabilitation benefits or seek assistance from various institutions during the quarantine and isolation period. Many posts also discussed coping with daily life tasks such as shopping, purchasing medications, cooking, cleaning, and other aspects of day-to-day life management.

However, during that time, the topics of self-esteem and self-determination were rarely mentioned. Only 2% of all the contents addressed issues of self-determination and expressed a demand for equality in accessing information about the epidemic and receiving support to meet one’s needs during a health crisis situation. These themes were overshadowed by other topics. The category of self-esteem occupied a marginal portion of the entries (accounting for approximately 8% of the total).

The next phase of the study covered the period between December 28, 2020, and February 10, 2021. During this time, strict isolation rules were implemented, including mobility restrictions and limitations on meeting people outside of the household, due to the increased incidence of COVID-19. However, the situation differed from that of spring 2020, as the COVID vaccine was released in December, and a vaccination campaign to combat the virus was launched (cf. Stróżyk, 2020).

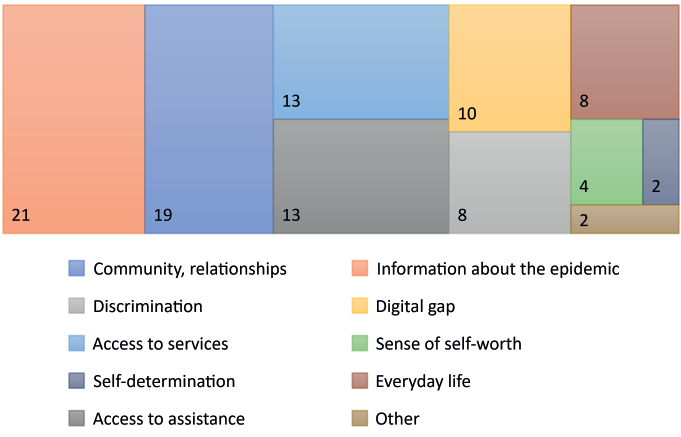

During this period, the content with information about the epidemic was the most prevalent (cf. Figure 2). In addition to questions and discussions about new virus mutations and the spread of the disease in Poland and abroad, the topic of vaccination emerged. While many comments encouraged people to get vaccinated as soon as possible, there were also numerous statements that expressed criticism or aversion toward vaccination.

Figure 2. Categories of content on Facebook profiles from December 28, 2020, to February 10, 2021

Source: own research.

Compared to the previous period, there was a notable increase in statements that undermined the existence of the epidemic itself and referred to it as a “plandemic,” suggesting hidden benefits for those in power behind the introduced restrictions. There were plenty of funny comic strips, videos, verbal jokes and memes that humorously depicted various aspects of the coronavirus, vaccination, infected individuals, physicians, police officers, the restrictions implemented through orders and bans, as well as people’s reactions to them.

The next most popular category was centered around relationships and communities. The prevailing content consisted of requests for advice on mitigating the effects and surviving a coronavirus infection, as well as concerns regarding a potential wave of new infections. There were also frequent discussions about coping with quarantine or isolation during Christmas and the New Year’s Eve. Many of the published comments focused on establishing new relationships or strengthening the existing ones. Group members suggested interactions such as “Do you want to talk?” or “I’m in quarantine. Is anyone up for a chat?” Recommending movies, books, TV shows, and computer games was also a common occurrence.

During this period, there was an increase in statements from individuals expressing feelings of discrimination. This was most often attributed to the fact that people with disabilities, despite being at a higher risk of severe coronavirus infection, were not prioritized in the initial vaccination group (Boyle et al., 2020; Kocejko, Bakalarczyk, Kubicki, 2021). In addition, d/Deaf individuals pointed out that the absence of the Polish Sign Language interpreters and the use of full-face masks in hospitals and ICUs made communication with medical staff extremely challenging. The issue of discrimination against this category was also raised when masks were mandated instead of clear visors. The d/Deaf and hard-of-hearing using social media faced challenges in understanding what vendors said and encountered difficulties in communicating with others as they were unable to observe the speaker’s mouth. Individuals with visual disabilities and mobility impairments mentioned significant difficulties arising from the fear of others approaching them and providing assistance while adhering to the social distancing rule which was, supposedly, strictly enforced by the police. The group members emphasized the need for regulations to reflect their specific situation.

Many comments also revolved around the category of digital exclusion. Users said that the solutions implemented by public institutions were inaccessible, highlighting the incompatibility of published digital materials with screen readers. Lectures and synchronous meetings did not provide subtitles or the Polish Sign Language interpreting, which frequently rendered work, education, and online activities inaccessible to individuals with disabilities.

Numerous comments were also made regarding the category of access to benefits and assistance. Within the community, there was a significant amount of information sharing regarding the process of obtaining disability certificates during the epidemic. This was particularly important for individuals whose certificates were about to expire and who needed to acquire new ones. Many posts also discussed telemedical appointments and the issuance of disability certification by default.

A significant number of comments revolved around describing personal health or legal situations, and seeking advice on which benefits to apply for as well as on the appropriate course of action. Social media users claimed that obtaining comprehensive advice from the institutions responsible for issuing certificates or from the Social Security Institution was challenging. As a result, they relied on support and information provided by social media groups. On the other hand, in the category of everyday life, there were statements that addressed problems with the purchase of medications or specific accessories. Frequent requests for the information on where to buy particular drugs were made. In addition, there were comments discussing various issues of daily living such as commuting to work, pet-related problems and parking space issues. In this category, users also shared their experiences and recommended specialized devices such as wheelchairs, gloves, and pillows. It also included questions such as “How do you handle your wheelchair in the rain?” or “What do you use to prevent your wheels from smudging the floor at home?” These discussions revolved around disability-related matters and focused on the issues of day-to-day living.

During this period, themes related to self-determination and self-esteem were more prominent. People with disabilities observed that this category was marginalized by the regulations being introduced and the activities planned in relation to the pandemic. Users posted content highlighting the importance of demanding that their rights to medical care, rehabilitation and vaccinations be respected. Group members claimed that they were excluded from the discussion regarding their prioritization for vaccination; they said that their voices were not considered while outreach activities aimed at the community were being planned, and that such activities should also be provided online.

The conducted study enabled me to reconstruct the statements shared by people with disabilities in social media groups, highlighting the significance of social media networks for this specific social category during the epidemic. By comparing the content of posts from the period between March and May 2020 with the period between December and February 2021, I observed the transformation of content and the evolving role of virtual communities during the crisis caused by the epidemic. Throughout the entire pandemic period, it could be observed that the most frequent posts in Facebook groups for people with disabilities were those related to the epidemic itself. Users not only shared information on the topic, but also actively engaged with posts by sharing them with friends, adding comments, or using reaction icons to express support, anger, surprise, or worry. The category of community and relationships also frequently emerged, which was driven by feelings of loneliness and isolation as well as the desire to seek support within the community during quarantine due to infection. Alongside these categories, it is noteworthy that people with disabilities within the realm of social media highlighted instances of discrimination and exclusion, and voiced their demand for respect and exercise of their rights. This demonstrates the tremendous potential of social media for people with disabilities in emergency situations, as they provide a platform for seeking information, sharing concerns, finding support and advocating for one’s rights. However, it is worth noting that Facebook also harbored conspiracy theories and false information regarding vaccinations, the epidemic itself, and its causes. These issues can pose a threat to individuals with disabilities and, in crisis situations, potentially place them at risk by encouraging vaccination refusal or denying the existence of epidemics.

The conducted study reveals that people with disabilities in Poland actively searched for and shared information about the epidemic in social media. This pattern was consistent in both the first and second phases of the study, with health-related issues and experiences of coronavirus infection being the most prevalent topics. These findings align with ongoing studies which indicate that compared to the general population, individuals with disabilities typically exhibit greater interest in health information and are more likely to search for it online (cf. Andreassen et al., 2007; Dobransky, Hargittai, 2016). During the COVID-19 epidemic, topics related to infection, disease progression, and preventive measures were even more prevalent within the disability community than among the general population (cf. Dobransky, Hargittai, 2021). Unfortunately, there was also harmful content spreading misinformation and false information being published. This highlights that social media during a health crisis can contribute to negative phenomena and dissemination of fake news while posing challenges to emergency management institutions (Alathur, Pai, 2023).

The themes of discrimination, exclusion, and inadequate health benefits or assistance services during the lockdown periods in Poland were also frequently discussed. These topics formed part of a broader discourse highlighting that the solutions implemented in 2020 and 2021, which were intended to facilitate online work, education, and the use of public services, were, in fact, inaccessible (cf. Nguyen et al., 2020). The sense of marginalization and discrimination expressed by the members of the Facebook group under study aligns with the research conducted during the epidemic. That research indicates that the public debate surrounding the lifting of self-isolation measures and reopening of certain industries, institutions, and facilities often prioritized the needs and desires of the general population, while it overlooked the dangers faced by vulnerable individuals, including people with disabilities, who are at a higher risk of experiencing severe complications from the disease (Dobransky, Hargittai, 2020). This highlights the potential of social media and new technologies to foster the inclusion of people with disabilities. However, it is crucial that these platforms are designed with accessibility in mind, adhering to the principles of universal or inclusive design (cf. Toquero, 2020; Dobransky, Hargittai, 2021).

Cytowanie

Dorota Żuchowska-Skiba (2023), The Importance of Social Media for People with Disabilities in Poland During the COVID-19 Epidemic, „Przegląd Socjologii Jakościowej”, t. XIX, nr 3, s. 80–95 (https://doi.org/10.18778/1733-8069.19.3.05).

Alathur Sreejith, Pai Rajesh (2023), Usefulness and barriers of adoption of social media for disability services: an empirical analysis, “Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy”, vol. 17(1), pp. 147–171.

Alathur Sreejith, Kottakkunnummal Manaf, Chetty Naganna (2021), Social media and disaster management: influencing e-participation content on disabilities, “Transforming Government: People, Process and Policy”, vol. 15(4), pp. 566–579, https://doi.org/10.1108/TG-07-2020-0155

Andreassen Hege, Bujnowska-Fedak Maria, Chronaki Catherine, Dumitru Roxana, Pudule Ivete, Santana Silvina, Voss Henning, Wynn Rolf (2007), European citizens’ use of E-health services: A study of seven countries, “BMC Public Health”, vol. 53(7), pp. 1–7, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-7-53

Armitage Richard, Nellums Laura (2020), The COVID-19 response must be disability inclusive, “The Lancet Public Health”, vol. 5(5), pp. 257–261, https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpub/article/PIIS2468-2667(20)30076-1/fulltext (accessed: 5.03.2023).

Banerjee Debanjan, Rai Mayank (2020), Social isolation in Covid-19: The impact of loneliness, “International Journal of Social Psychiatry”, vol. 66, pp. 525–527.

Boyle Coleen, Fox Michael, Havercamp Susan, Zubler Jennefer (2020), The public health response to the COVID-19 pandemic for people with disabilities, “Disability and Health Journal”, vol. 13(3), pp. 1–4, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2020.100943

Burke Lucy, Crow Liz (2017), Bedding Out: Art, Activism and Twitter, [in:] Katie Ellis, Mike Kent (eds.), Disability and the social media: Global perspectives, London: Routledge, pp. 57–74.

Chanda Srei, Sekher T.V. (2020), Disability during COVID-19: Increasing vulnerability and neglect, “Economic and Political Weekly”, vol. 55(30), pp. 30–33.

Dobransky Kerry, Hargittai Eszter (2016), Unrealized potential: Exploring the digital disability divide, “Poetics”, vol. 58, pp. 18–28.

Dobransky Kerry, Hargittai Eszter (2020), People with Disabilities During COVID-19, “Contexts”, vol. 19(4), pp. 46–49, https://doi.org/10.1177/1536504220977935

Dobransky Kerry, Hargittai Eszter (2021), Piercing the pandemic social bubble: Disability and social media use about COVID-19, “American Behavioral Scientist”, vol. 65, pp. 1698–1720.

Ellis Katie, Goggin Gerard, Halle Beth, Curtis Rosemary (2019), Disability and Media – An Emergent Field, [in:] Kate Ellis, Gerard Goggin, Beth Haller, Rosemary Curtis (eds.), The Routledge Companion to Disability and Media, New York: Routledge, pp. 5–15.

Goggin Gerard (2015), Communication rights and disability online: Policy and technology after the World Summit on the Information Society, “Information, Communication and Society”, vol. 18(3), pp. 327–341.

Goggin Gerard, Newell Christopher (2003), Digital disability: The social construction of disability in new media, Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield.

Hay Kathryn, Pascoe Margaret (2019), Disabled people and disaster management in New Zealand: examining online media messages, “Disability and Society”, vol. 34(2), pp. 253–275, https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2018.1545114

Headland Thomas (1990), Introduction: a dialogue between Kenneth Pike and Marvin Harris on emics and etics, [in:] Kenneth L. Pike, Marvin Harris (eds.), Emics and etics: The insider/outsider debate, London: Sage Publications, pp. 13–27.

Huang Shiwei, Wang Yuwei (2023), How People with Physical Disabilities Can Obtain Social Support through Online Videos: A Qualitative Study in China, “International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health”, vol. 20(3), pp. 2423–2437, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032423

Juszczyk-Rygałło Joanna (2018), Nowe media jako element kształtowania kapitału społecznego ich użytkowników, “Media i Społeczeństwo”, vol. 8, pp. 51–60.

Kampert Amy, Goreczny Anthony J. (2007), Community involvement and socialization among individuals with mental retardation, “Research in Developmental Disabilities”, vol. 28(3), pp. 278–286, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2005.09.004

Kent Mike (2020), Social media and disability: It’s complicated, [in:] Katie Ellis, Gerard Goggin, Beth Haller, Rosemary Curtis (eds.), Routledge companion to disability and the media, New York: Routledge, pp. 264–274.

Kent Mike, Ellis Kelly (2015), People with disability and new disaster communications: access and the social media mash-up, “Disability and Society”, vol. 30(3), pp. 419–431.

Klemm Paula, Bunnell Dyane, Cullen Maureen, Soneji Rachna, Gibbons Patricia, Holecek Andrea (2003), Online Cancer Support Groups: A Review of the Research Literature, “CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing”, vol. 21, pp. 136–142, https://doi.org/10.1097/00024665-200305000-00010

Kocejko Magdalena (2021), Sytuacja dzieci z niepełnosprawnościami w czasie pandemii COVID-19 – analiza intersekcjonalna, “Dziecko Krzywdzone. Teoria, Badania, Praktyka”, vol. 20(2), pp. 76–91.

Kocejko Magdalena, Bakalarczyk Rafał, Kubicki Paweł (2021), Wpływ pandemii koronawirusa na politykę wobec niepełnosprawności i starości, [in:] Artur Zybała, Krzysztof Księżopolski, Andrzej Bartosiewicz (eds.), Polska… Unia Europejska… Świat w pandemii COVID-19. Wybrane zagadnienia, Warszawa: Dom Wydawniczy Elipsa, pp. 96–116.

Li Hanlin, Bora Disha, Salvi Sagar, Brady Erin (2018), Slacktivists or Activists? Identity Work in the Virtual Disability March, Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on “Human Factors in Computing Systems”, vol. 225, pp. 1–13, https://doi.org/10.1145/3173574.3173799

Lin Zhongxuan, Yang Liu, Zhang Zhi’an (2018), To include, or not to include that is the question: disability digital inclusion and exclusion in China, “New Media and Society”, vol. 20(12), pp. 4436–4452.

Masłyk Tomasz, Migaczewska Ewa, Stojkow Maria, Żuchowska-Skiba Dorota (2016), Aktywni niepełnosprawni? Obywatelski i społeczny potencjał środowiska osób niepełnosprawnych, Kraków: Wydawnictwa Akademii Górniczo-Hutniczej.

Morris John, Mueller James, Jones Michael (2014), Use of social media during public emergencies by people with disabilities, “The Western Journal of Emergency Medicine”, vol. 15(5), pp. 567–574.

Nguyen Minh Hao, Hargittai Eszter, Marler Will (2021), Digital inequality in communication during a time of physical distancing: The case of COVID-19, “Computers in Human Behavior”, no. 120, 106717.

Nguyen Minh Hao, Gruber Jonathan, Fuchs Jaelle, Marler Will, Hunsaker Amanda, Hargittai Eszter (2020), Changes in Digital Communication During the COVID-19 Global Pandemic: Implications for Digital Inequality and Future Research, “Social Media + Society”, vol. 6(3), pp. 1–6.

Nguyen Minh Hao, Gruber Jonathan, Marler Will, Hunsaker Amanda, Fuchs Jaelle, Hargittai Eszter (2021), Staying connected while physically apart: Digital communication when face-to-face interactions are limited, “New Media and Society”, vol. 24(9), pp. 1–8, https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820985442

Patel Jay, Nielsen Freja, Badiani Ashni A., Assi Sarah, Unadkat Vrajeshkumar, Patel Bakula, Ravindrane Ramyadevi, Wardle Heather (2020), Poverty, inequality and COVID-19: the forgotten vulnerable, “Public Health”, vol. 183, pp. 110–111.

Poppen William, Bradley Natalie (2003), Assistive technology, computers and Internet may decrease sense of isolation for homebound elderly and disabled persons, “Technology and Disability”, vol. 15(1), pp. 19–25, https://doi.org/10.3233/TAD-2003-15104

Przedłużamy etap odpowiedzialności i wprowadzamy dodatkowe ograniczenia – zamknięte stoki i nowe zasady bezpieczeństwa w Sylwestra (2020), https://www.gov.pl/web/koronawirus/przedluzamy-etap-odpowiedzialnosci-i-wprowadzamy-dodatkowe-ograniczenia (accessed: 5.03.2023).

Robinson Laura, Schulz Jeremy, Khilnani Aneka, Ono Hiroshi, Cotten Shelia R., McClain Noah, Levine Lloyd, Chen Wenhong, Huang Gejun, Casilli Antonio A., Tubaro Paola, Dodel Matias, Quan-Haase Anabel, Ruiu Maria L., Ragnedda Massimo, Aikat Deb, Tolentino Natalia (2020), Digital inequalities in time of pandemic: COVID-19 exposure risk profiles and new forms of vulnerability, “First Monday”, vol. 25(7), pp. 1–7.

Roland Damian, Spurr Jesse, Cabrera Daniel (2017), Preliminary evidence for the emergence of a health care online community of practice: Using a netnographic frame work for twitter hashtag analytics, “Journal of Medical Internet Research”, vol. 19(7), pp. 252–265.

Shoham Snunith, Heber Meital (2012), Characteristics of a virtual community for individuals who are d/deaf and hard of hearing, “American Annals of the Deaf”, vol. 157(3), s. 251–263.

Smieszek Mateusz (2021), Aktywność i głos osób z dysfunkcjami sensorycznymi na portalach społecznościowych. Raport z badań netnograficznych, “Praca Socjalna”, vol. 36(6), pp. 37–65.

Smieszek Mateusz, Borowska-Beszta Beata (2017), Nethnographic Research Report on Families with Members with Disabilities in Social Media and Facebook, “Psycho-Educational Research Reviews”, vol. 6(2), pp. 89–102.

Stojkow Maria, Żuchowska-Skiba Dorota (2014), Od porad medycznych ku prozie życia – czyli przemiany dyskursu osób z niepełnosprawnościami w Internecie, “Niepełnosprawność – Zagadnienia, Problemy, Rozwiązania”, no. 3, pp. 41–55.

Stojkow Maria, Żuchowska-Skiba Dorota (2015), Aktywność osób z niepełnosprawnościami na profilach i forach społecznościowych w społeczeństwie sieci, “Polityka Społeczna”, vol. 42(5), pp. 17–21.

Stróżyk Agata (2020), Pandemia koronawirusa na świecie i w Polsce – kalendarium, https://www.medicover.pl/o-zdrowiu/pandemia-koronawirusa-na-swiecie-i-w-polsce-kalendarium,7252,n,192 (accessed: 5.03.2023).

Sweet Kayla S., LeBlanc Jennifer K., Stough Laura M., Sweany Noelle W. (2020), Community building and knowledge sharing by individuals with disabilities using social media, “Journal of Computer Assisted Learning”, vol. 36, pp. 1–11.

Toquero Cathy M.D. (2020), Inclusion of People with Disabilities amid COVID-19: Laws, Interventions, Recommendations Multidisciplinary, “Journal of Educational Research”, vol. 10(2), pp. 158–177.

Uden-Kraan Cornelia van, Drossaert Constance, Taal Erik, Shaw Bret, Seydel Ervin, Laar Mart van de (2008), Empowering processes and outcomes of participation in online support groups for patients with breast cancer, arthritis, or fibromyalgia, “Qualitative Health Research”, vol. 18, pp. 405–417.

United Nations (2020), Policy Brief: A Disability-Inclusive Response to COVID-19, https://unsdg.un.org/resources/policy-brief-disability-inclusive-response-covid-19 (accessed: 12.02.2023).

Verdegem Pieter (2011), Social Media for Digital and Social Inclusion: Challenges for Information Society 2.0 Research & Policies, “Triple C”, vol. 9(1), pp. 28–38, https://doi.org/10.31269/vol9iss1pp28-38

Wright Kevin (2016), Social Networks, Interpersonal Social Support and Health Outcomes: A Health Communication Perspective, “Front Community”, vol. 1, pp. 10–19, https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2016.00010

Wright Kevin, Bell Sally (2003), Health-related Support Groups on the Internet: Linking Empirical Findings to Social Support and Computer-mediated Communication Theory, “Journal of Health Psychology”, vol. 8(1), pp. 39–57, https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105303008001429

Zielińska-Pękał Daria (2014), Wykorzystanie strategii emicznej w badaniach nad poradniczymi praktykami wspólnot wirtualnych, “Dyskursy Młodych Andragogów/Adult Education Discourses”, vol. 15, pp. 154–169.

Żuchowska-Skiba Dorota (2018), Niepełnosprawność w dobie Web 2.0. Znaczenie portali społecznościowych dla osób z niepełnosprawnościami, [in:] Ewa Grudziewska, Marta Mikołajczyk (eds.), Wybrane problemy społeczne: teraźniejszość – przyszłość, Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Akademii Pedagogiki Specjalnej, pp. 138–148.

Żuchowska-Skiba Dorota (2021), The social dimension of the Internet from the perspective of people with disabilities during the Covid-19 pandemic, “Przegląd Socjologiczny”, vol. 70(3), pp. 31–47.