https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2156-6754

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2156-6754University of Warsaw

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2156-6754

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2156-6754

University of Warsaw https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8503-4845

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8503-4845

Abstract:

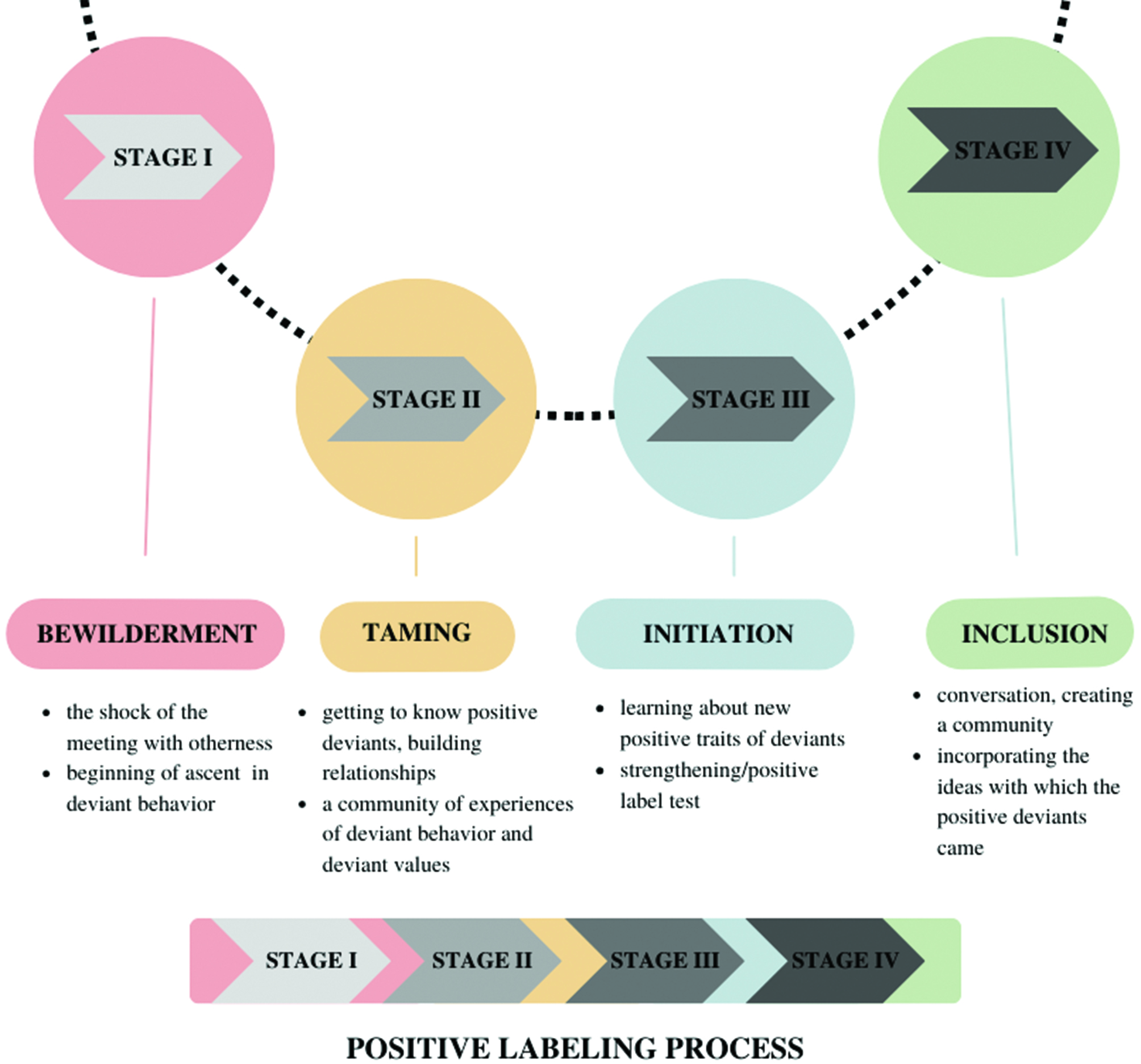

The evaluation of the pedagogical-theatrical project Trolls is a source of data on the basis of which we propose the use of positive labeling categories. We expanded it by naming the stages of this form of labeling: bewilderment, taming, initiation, and inclusion. We described the social consequences of gradually becoming familiar with differences, including and placing people with disabilities in the center. We showed how the labeling mechanism was used in artistic-educational activities and redirected toward a discussion of the values of social diversity.

Trolls is a play and workshop created by the Theatre 21 Foundation. It is aimed at primary school students and conducted in classrooms. Through explicit observations, and by referring to the relations between theater educators and actors and class teachers, we examined what the visit of the titular trolls, or actors from Theatre 21, most of whom have Down syndrome or autism, brings to the school and how these actions resonate with the participants.

Owing to the processual character of the evaluation, we were able to discover new research categories. Our research was of an abductive nature. Sensitizing concepts enabled the development of the main category of positive labeling.

Keywords:

integration through art, evaluation, sensitizing concepts, positive labeling, theatre pedagogy

Abstrakt:

Ewaluacja projektu pedagogiczno-teatralnego „Trolle” to źródło danych, na podstawie których autorki artykułu zaproponowały użycie kategorii pozytywnego etykietowania. Rozszerzyły ją, nazywając etapy takiej formy naznaczania: oszołomienie, oswajanie, wtajemniczenie i inkluza. Opisały społeczne konsekwencje stopniowego zaznajamiania się z innością, włączania i stawiania osób z niepełnosprawnościami w centrum. Autorki pokazały, jak mechanizm etykietowania został wykorzystany w działaniach artystyczno-edukacyjnych i przekierowany w stronę dyskusji o wartościach różnorodności społecznej.

Trolle to spektakl i warsztaty stworzone przez Fundację Teatr 21. Projekt jest skierowany do uczniów szkół podstawowych i realizowany w klasach szkolnych. Za pomocą jawnych obserwacji oraz odnosząc się do relacji pedagogów teatru, aktorów i wychowawców klas, autorki zbadały, co wizyta tytułowych trolli, czyli aktorów Teatru 21, w większości osób z zespołem Downa i autyzmem, wnosi do szkoły i jak te działania wpływają na uczestników. Dzięki procesualnemu charakterowi ewaluacji autorkom udało się odkryć nowe kategorie badawcze. Prowadzone przez nie badania miały charakter abdukcyjny. Uczulające pojęcia umożliwiły rozwijanie głównej kategorii – pozytywnego etykietowania.

Słowa kluczowe:

integracja przez sztukę, ewaluacja, pojęcia uczulające, pozytywne etykietowanie, pedagogika teatru

The main goal of this text is to guide the reader through the various stages of interaction between artists and audience members, as studied during the implementation of the project titled Trolls, in order to demonstrate the potential of the category of positive labeling identified in evaluative studies. Trolls is an interactive theatrical event produced by the Theatre 21 Foundation[1], addressed to students and teachers in grades 1–3 of primary school.

The titular roles of trolls were played by actors, the majority of whom had Down syndrome and autism. At the beginning of the performance, they wore masks. Gradually, they revealed themselves to the children through visual encounters (open permission to stare at each other), sounds, music, movement, and touch (from shaking hands to stroking and hugging). The creators of the event wrote about them as follows:

There are many legends and stories about trolls that adults tell children. In many of them, trolls resemble wild creatures. They are oddities somewhat like humans and somewhat like animals. Trolls live in hiding, stick together, and rarely expose themselves to the gaze of others. Only a few people speak well of them. Many people are afraid of trolls, even though they have never met one in their life. Trolls have also heard fantastic stories about humans and for many years preferred not to show themselves. It’s time to put an end to that! The time has come to finally see each other! (Teatr 21, n.d., Trolle)

The trolls entered the schools. They hid in classrooms and when the children and their teachers entered, they tried to establish a relationship with them. Many individual micro-interactions such as making eye contact, touching, joint writing, or making sounds, and then conversation, led to the discovery of otherness, but through its gradual taming. It was these micro-interactions that constructed the socio-artistic situation we observed, and their description was an essential source of our data.

We see the performance together with the workshop as an interaction consisting of many micro-interactions (such as gazing, touching, stroking, exchanging of words, making sounds). We used the term ‘interaction’ in reference to the dramaturgical approach created by Erving Goffman, which resonates strongly with the issues we studied due to its references to the world of theatre (Goffman, 1956). Trolls is an interaction, because it is a dialog between two groups (Goffman, 1956) – the actors and the audience members. Referring to the entire theatrical event (performance and workshops) in the text, we used the word Trolls written in capital letters. We referred to the context in which the activities took place and referred to the history of the Theatre 21 Foundation, i.e. the theatre “with one extra chromosome”[2], but it was Trolls that was the subject of our research and the main point of reference.

In the text, we presented the theoretical part after describing the methodology to reflect the process of identifying the category of positive labeling from the analysis. We referred to theoretical material that we compared with empirical data during the research. Then, using the results of intertwined exploration and inspection, we presented the characteristics of positive deviants and the stages at which the positive label emerges, using Trolls as an example.

The research conducted by us was part of the evaluation of the O!Swój[3] project in 2019. The project, which has been implemented since 2014, with a slightly different formula each year. The common denominator of each edition was an attempt to penetrate school reality with artistic methods, a program of diversity integration, ideas of inclusive education, and theatre pedagogy. The main feature of the project was its processuality, based on the assumption of safety in introducing changes. The process took place through small steps. “O!Swój is penetrating through cracks”[4]. In 2019, the educational offer of Theatre 21 within the O!Swój project included artistic residencies, workshops for plays (including the play Trolls), and meetings for educators. The main goal of the undertaken activities was to introduce ideas of inclusive education into schools and to build sensitivity to difference, which is an element of the social integration of people with disabilities, as well as the idea of the Theatre 21 Foundation’s activities.

Trolls was a collaboration with six public and six non-public primary schools in Warsaw. In 2019, a total of eighteen performances were held (including one for a group of teachers). Nine of them took place in public schools and seven in non-public institutions. In the evaluation conducted in 2019 (Babicka, Kalinowska, Zalewska-Królak, 2019), we focused on the issues of the possibilities and impossibilities of introducing changes in school reality through artistic activities. The evaluation was conducted in a flexible way, which allowed for the discovery of new research leads. We had no goals, hypotheses, or even main research leads. The persons commissioning the evaluation were willing to learn about new perspectives, such as angles with which their creativity and actions had not been previously examined. The trust developed between the Foundation’s representatives and the evaluators of previous editions (Kalinowska, Rożdżyńska, 2017; Kalinowska, 2018) ensured that we were met with openness to our proposals from the outset.[5] Such research possibilities led us to decide on qualitative research embedded in the tradition of symbolic interactionism when planning the evaluation of the Trolls project. We had a defined research problem that we wanted to address, but we also wanted to discover concepts during the research. We treated concepts according to Herbert Blumer (1986) as something that allows us to capture and retain the content of experience. We focused on searching for concepts that sensitize and should be constantly corrected and explained in confrontation with the empirical world. The method we chose was abduction and analytical induction (Kaufmann, 2013). We applied researcher triangulation.

The research material gathered in the Trolls module consisted of observation cards of artistic events (8); surveys filled out by teachers (10); reports from theater pedagogues and actors from Theatre 21 who conducted workshops (15). This data was expanded with reflections from the project’s implementers during a focus group interview held in January. The constructed material revealed the polyphony of observations, its multidimensionality, and phenomenological character. It allowed us to grasp the researched reality in its everyday context by listening to different voices. We created analysis tools during the research. They were the result of repeated transitions from exploration to inspection.

The direct inspiration that led us to the theory of labeling was the culmination of the interaction between trolls (actors from Theatre 21) and students, which involved the trolls bestowing upon the class a patch made of troll fur at the end of each meeting. The students and their teacher found a place in the classroom for this gift, which served as a symbolic sign of the trolls being accepted into the class. The patch was meant to remind the students of their encounter with the foreign and the different, while also becoming a label that characterized the newly met trolls. The patch was made of a pleasant material that people want to stroke, which triggered positive associations and recalled the actions that took place in the play. During the event, we observed how children hugged the same material attached to the board, as well as touched and stroked the trolls’ masks and fur. The label was unambiguously positive, and by taming the trolls, the patch helped create a positive context.

The projects that accompanied the production and implementation of Trolls included O!swój and Gap się[6]. Their combination with the micro-interactions we observed in the project, culminating in the placement of patches in classrooms (such as conversations between children or between teachers and children, workshop themes, smiles, and engagement, for example) inspired us to seek deeper interpretive paths related to the concepts of deviation, stigma, and labeling. Describing the process of taming, but emphasizing the consent to “staring” or even encouraging people to pay attention to what is normally invisible or overlooked in public spaces, was made possible through the analysis of publications on Theatre 21’s activities (Godlewska-Byliniak, Lipko-Konieczna, 2016; 2018; Godlewska-Byliniak, 2017; Kietlińska, 2019). Including the context in which Trolls was created in our research allowed us not only to describe the characteristics of positive labeling through the example of Trolls, but also to identify the stages that lead to assigning a positive label.

The theory of labeling, or the theory of stigmatization, has its roots in works that form the foundation of symbolic interactionism, which we have adopted in our research. An example of this can be seen in Charles Horton Cooley’s concept of the “self” from 1902, which he coined by referring to Adam Smith’s theory. This concept was further developed in the work of Frank Tannenbaum (1938) and Edwin Lemert’s theory of secondary deviation (Lemert, 1951). Howard Saul Becker (1963) also drew on this concept in developing the labeling theory. Another important perspective, also built on the concept of the self, was George Mead’s social psychology (Mead, 1909). Erving Goffman (1963) and Thomas Scheff (1966) contributed to the later development of labeling theory in sociology from an interactionist perspective. Many sociological and criminological theories initially focused primarily on the role of social control as a factor that forms the basis of social order, enabling the existence and integration of society (Krajewski, 1983). The shift from a positivistic to an interactionist perspective contributed to a gradual departure from a deterministic approach to this issue (Krajewski, 1983), which was an important turning point for us. Previous concepts did not resonate with the results of our empirical research. It was important to us when researchers’ interest shifted from seeking the causes of phenomena to observing their course and the context that accompanies them. However, both approaches still shared a similar research problem related to the concept of deviance. The question of what causes it was replaced with the question of what it is. Observing deviance rather than searching for its causes is an approach closer to our analytical categories, which is why we directed our theoretical research in this direction.

We examined the concept of deviance created by various authors and compared it with the results of our analysis. Jerzy Kwaśniewski, writing about labeling, briefly stated that deviance is equivalent to abberation (Kwaśniewski, 2012: 64). In sociology, however, this term is often used interchangeably with social problems, state of disorganization, or social pathology, and to distinguish certain categories of people, institutions, or subcultures (Kwaśniewski, 2012: 65). The common feature of all these phenomena, referred to as deviance, is their “anchoring” in the generally accepted norm, i.e. focusing on human perception of social reality. As Peter Berger and Thomas Luckman (1967) emphasize, people tend to order events by referring to the accepted image of social order. Using the term “symbolic universe”, the authors show how historically accumulating theoretical generalizations, which integrate institutionalized order of a given community into a symbolic whole, provide us with justifications for this order (Berger, Luckman, 1967). According to the labelling theory, deviance is a phenomenon created by society. As Becker emphasizes, a person who has been successfully labeled as deviant is called a deviant. Deviant behavior is behavior that people label as such (Becker, 1963). The characteristic of “otherness” is assigned to human behavior by the social reaction to that behavior. The “otherness” of the perpetrator depends on it (Kwaśniewski, 2012: 72). Both what deviates from the norm and what fits into it have no objective characteristics. According to the labeling theory, deviant behavior is the meaning given to it as a result of the interaction between the individual and the social group. This research perspective emphasizes the role of the audience. It is the audience that decides whether certain behavior or group of behavior will be labeled as deviant (Erikson, 1962: 308). This means that it is not the violation of the norm that decides on deviance, but the reaction of the group. Kai T. Erikson, describing the concept of the “social audience,” shows that interactions between members of the social group comprising the audience and processes occurring in that group determine the interpretations that will be given to the behavior of other people, and consequently, the labeling of certain categories of people or behaviors as deviant through the use of sanctions (Erikson, 1962). Deviance from the perspective of labeling theory is an assigned status, not an achieved one, and focuses mainly on the study of behavior. This perspective of looking at deviance and defining it in this non-deterministic way proved crucial for the analysis of Trolls and enabled the creation of the categories of positive labeling.

In our research, the theory of labeling, focusing on the process of becoming a deviant as a result of stigmatization, was of great importance. Lemert distinguishes between primary and secondary deviation. The former has many causes and arises from various cultural, psychological, and physiological factors. From a social perspective, it is negatively evaluated. The latter occurs through the mechanism of reflected self (Lemert, 1967). Attitudes of the group perceived by the individual shape their self-esteem. If they feel that they are perceived as deviant, they may begin to see themselves in the same categories imposed on them by the audience. When the negative trait begins to dominate in the individual’s self-esteem, there is a danger that this individual will be identified and evaluated mainly according to the “master status” (Becker, 1963). We observed a similar mechanism, but in the case of positive labeling. It ceases to be a danger and becomes a potential. The labeling theory emphasizes the role of social interpretations and evaluations in the genesis of control actions of social groups, but mainly focuses on deviant labels, thereby neglecting the study of positive label functioning. Gregory A. Thompson (2014) identifies the foundation for a positive labeling perspective in the operationalization of labeling as a phenomenon that occurs in real interactions, not post hoc. According to the author, giving labels is a relational process. However, it is noticeable that the perspective of positive labeling is still underestimated (Kwaśniewski, 2012; Pyszczek, 2012; Thompson, 2014). Jerzy Kwaśniewski points out that “the little interest of Polish researchers in the attitudes and behaviors of positive social deviance is quite incomprehensible, given that social sciences, also Polish, have interesting theoretical concepts of positive deviance” (Kwaśniewski, 2012: 82). An example may be the theory of civilizational over-achievement (Znaniecki, 1974) or the theory of the so-called positive disintegration of personality (Dąbrowski, 1967). Studies of exceptional individuals are also studies of hero cults (Czarnowski, 1956) and the knightly ethos (Ossowska, 1973). Antonina Kłoskowska’s idea of heroism as a personal symbol of cultural value (Kłoskowska, 1971) is also close to this perspective. The fact that such a perspective is rare is indicated by the small number of scientific institutions that focus on research on altruism, innovation, and creativity. There are none in Poland at all (Kwaśniewski, 2012).

Comparing the perspective of virtuology (Latin virtus – virtue) (Kwaśniewski, 2012) with our observations of microinteractions during the Trolls event allowed us to examine the figure metaphorically represented as a troll and recognize them as a positive deviant. The actions of the Positive Deviance movement were also a significant inspiration for us. Unlike the assumptions of Jerzy Kwaśniewski’s concept (or Florian Znaniecki’s, from which Jerzy Kwaśniewski’s theory originated), they do not assume a conflict between the positive deviant and society, but, rather, focus on the potential for such cooperation (Pyszczek, 2012). Defining a deviant as someone who has different characteristics than the average participant in a given social environment (Pyszczek, 2012: 158) is close to the phenomena we have observed.

The establishment of virtuology as a new discipline within the social sciences is an initiative of Jerzy Kwaśniewski (Pyszczek, 2012). Its focus is on the study of positive deviations from social norms. According to the author, “deviation can be understood as all individual or collective behaviors that go beyond the realm of social indifference, i.e., elicit condemnation (repulsion) or strong social approval (apulsion)” (Kwaśniewski, 2012: 77). Positive deviance for Jerzy Kwaśniewski includes pro-social behaviors that result from altruistic motivation, innovative (creative) non-conformism, constructive antagonism, moral perfectionism, “creative anxiety,” pro-social heroism, civilizational abnormality, positive social maladjustment, etc. (Kwaśniewski, 1976: 215), which can be both individual and collective. The author’s research and publications indicate three research directions related to the analysis of positive deviance (Pyszczek, 2012):

In this article, we refer to all of these research directions while analyzing the interactions of Trolls in terms of the characteristics that Jerzy Kwaśniewski identifies as positive deviance (Kwaśniewski, 2012: 80):

We will attempt to demonstrate how the characters of the trolls, and thus the disabled actors playing them, reflect the four aforementioned characteristics. Trolls are creatures that were discovered by children in grades 1–3 in several primary schools in Warsaw. In the description of the event, we can read: “The performance Trolls is a missing lesson that shows the potential of a meeting, class, and school. How many possibilities does a class contain? What power and meaning does this meeting have? How can we be together without running away from ourselves in fear?” (Teatr 21, n.d., Trolle). We will try to show how the characters of trolls, and the artists with disabilities who portray them in Theatre 21, reflect the four characteristics mentioned above.

We are invoking these passages to show that the event project is based on a certain type of stigma as understood by Erving Goffman (1963) as a discrediting attribute. Stereotypes that emerge during the analysis of prejudices about people with disabilities were recorded and analyzed by Katarzyna Kalinowska and Kaja Rożdżyńska (2020), referring to the evaluation of the first editions of the O!Swój project (Kalinowska, Rożdżyńska-Stańczak, 2017; Kalinowska, 2018). We draw attention to the context of the work of Theatre 21, as it is an important factor in the formation and maturation of positive stigma. It also demonstrates the first feature of positive deviation mentioned by Jerzy Kwaśniewski – exceeding expectations. Individuals gathered at the Theatre 21 Foundation incorporate the creativity of people with disabilities into the fields of art, culture, and science, changing the reality of both the artists themselves and the audience, thus creating a subculture of positive deviation. Their presence broadens perspectives and provides new opportunities. On a micro-scale, trolls are an example of this. They break the class order. They represent behaviors that “deviate from the observed »normality« […] we are dealing with the breaking of the »upper« limit of social expectations” (Kwaśniewski, 2012: 71). Interaction brings different relationships to the school, entering it with the idea of changing the perspective of looking at otherness in general, not just at disability.

The thread concerning the potential stigma of work also shows motivation for a kind of rebellion against prevailing standards (the second characteristic of positive deviance). It can be clearly seen in the publications of Theatre 21 (Godlewska-Byliniak, Lipko-Konieczna, 2016; 2018; Godlewska-Byliniak, 2017; Kietlińska, 2019; Garland-Thomson, 2020). In our opinion, Trolls is intentionally attempting to change the existing social order while respecting norms such as time constraints arising from the school system or spatial constraints associated with the decision to perform the play in a classroom. There is no place for individuality or difference in the school world. There is no time for a safe encounter with diversity, let alone confronting it. Utilizing the potential provided by the classroom allowed for the presentation of rebellious behaviors of the trolls; for example, while the children still sat in their usual seats, the trolls could climb onto windowsills, benches, or write on the blackboard without the teacher’s permission. Below, we described in more detail what significance it had in the process of positive labeling.

The third characteristic of positive deviation, which is “the non-selfish character of motivation or decision which encourages an individual or group to deviate from the existing order” (Kwaśniewski, 2012: 81), accurately reflects the idea behind the Theatre 21 Foundation. An example of this can be seen in the main motivation for the Gap się season, during which the play Trolls was produced – a reflection on the visibility of people with disabilities in public space rather than a profit for the creators. For the Trolls project, the school becomes a particularly important public space. The aim of the actors, director, screenwriter, and later also the theatrical educators (during workshops), is a gradual and safe familiarization with otherness. The nature of this process is not accidental. The creators and trolls enter with a specific proposal for change for the school – a one-time event, but with the potential for a new perspective. Despite numerous technical difficulties, the project’s creators unanimously agreed that the trolls had to enter the school. This performance could not take place in a theater. One of the project’s goals was to introduce a theatrical event full of delicacy, mindfulness, gradual familiarization, and gentleness, symbolized by the use of soft fur in the set design and leaving a fur patch to help deal with stress, nerves, and tensions that can arise in an educational institution. The trolls were meant to show that other types of relationships are possible in school. The otherness they work with is an acknowledgment of differences, but not as a negative stigma, but as a positive one.

The occurrence of objectively positive effects of deviant acts is the final element characterizing positive deviance. Due to the lack of long-term studies, we cannot determine the long-term effects. However, the history of Theatre 21’s activities, which can be observed as a recipient of their projects, indicates a process of professionalizing actors with disabilities, which we can unequivocally describe as positive. And what were the effects of the trolls’ actions as deviants observed in the classrooms? They were mainly related to the final outcome of the meeting, which we described in the next part at the final stage of the positive labeling process. As Jerzy Kwaśniewski emphasized, research on positive labeling “is not easy due to the fact that it is difficult to determine and attribute the characteristics of positive deviance to certain behaviors before conducting them, because on the one hand, these characteristics concern specific motivations for behavior, and on the other hand, their social function and perception” (Kwaśniewski, 2012: 80). In the case of our research, the category of positive labeling was the result of analysis, not the starting point. The actions we observed were a meeting of children with people with disabilities. At the level of events designed by the creators, a mechanism occurred, the reflection of which in the crooked but positive mirror was the mechanism described in the theory of social labeling. We broke it down into its first parts to discover the process that influenced the occurrence of positive stigmatization.

“The feature of »otherness«, deviancy, is given to human behavior by the social reaction to these behaviors. The »otherness« of the doer also depends on this reaction” (Kwaśniewski, 2012: 72). For this reason, it should be emphasized that labeling, as a process whose stages are outlined below, assumes the presence of people who carry it out. In the case of Trolls, it took place within the framework of a theatrical performance and the labelers were the spectators. It is a case of the performativity of a social situation, which had been designed by the creators of the show and the workshop leaders. Such interaction had a planned, repetitive course. Its elements could, but did not have to, assume specific reactions of students. Observing these reactions during several events, we noticed patterns that indicated repetitive elements of the process carried out by students who were recipients and participants. It was the process of positively labeling trolls, and then positively labeling people with disabilities playing them.

Labeling behaviors that we call deviant by intentionally going beyond school norms did not become dangerous because of the safe frame of the theatrical situation. The overturning of a certain social order was in this case limited to theatrical fiction. However, a relationship was truly established and lasted even when the actors took off their masks and stepped out of their roles. Theater has become a tool that treats children as subjects, not objects, by creating a space for them that is not devoid of new experiences, but is safe. In such conditions, changes and development are comfortable.

If we assume that positive stigmatization can be both a primary social reaction to behavior and also a type of reaction that appears after having previously negative label, it becomes important to try to answer the question asked by Jerzy Kwaśniewski (2012: 86): “What are the characteristics of the doer, his act, situation and social environment which evoke positive stigmatization and determine the course and effects of this process?”.

0. BASELINE

In the process we studied, we noticed two main features of the initial situation in which the child viewers could be at the beginning. They are concern a relation to trolls and people with disabilities. We acquired knowledge about them at the last stage of interaction, but it concerned previous impressions.

– The first one: exclusion and stereotypical thinking about others

The children talked about taming the otherness of a character about whom one could have had an unfavorable opinion before. The conversation disarmed the theme of duplicating untrue opinions about a topic or generalizing opinions about one person to the entire group he/she represented.

– The second one: fear of the unknown

The children shared their experiences concerning reasons for being afraid of meeting unknown people and situations. They talked about their ways of taming people, things, and situations which are safe, as well as about the courage.

1. BEWILDERMENT

the shock of encountering the otherness/unknown; the beginning of self-experiencing; the beginning of going into positive deviance

The show was designed to be performed in an “ordinary school classroom”. It is usually rectangular. After entering the hall, on the right side we see a blackboard, behind it there is a teacher’s desk, right next to the wall with decorated windows, opposite the blackboard there are two or three rows of school desks, often one for two people. Classes of students from the initial stage of education are distinguished by a space prepared for play. This is usually an empty seat or carpet in the back of the classroom.

The trolls in the performance blended into the classroom space. They hid in alcoves, under desks, as well as they stood on windowsills and behind the furniture. They tried not to interfere with the existing space. Tables were not rearranged, objects were not moved. The stage set was based on the appearance of the classroom and was flexible (portable potted flowers and other movable elements). There were only soft, earthy fur coats on the blackboard and carpet, green flowers in pots, and furry trolls. What is more, there was music played live by one of the trolls. Students entered the space prepared in this way. Usually, especially if the room was a classroom for a group, students would take their assigned seats upon entering. Despite the slight intrusion into the familiar room, they noticed the differences right away, pointing fingers at each other or glancing meaningfully in their direction. It was accompanied by a sense of strangeness and change. It was often associated with laughter or fear, which could mean children’s uncertainty. In several cases, we observed how students manifested hesitation by going under the desks or putting a hood over their heads. After a while, the teacher came to them and carefully checked if everything was okay. Actors also approached such children, trying to gently check whether contact with them would be helpful. Sitting in a school desk did not allow for withdrawal or a moment of isolation with the possibility of returning. The beginning of the performance, full of novelty and uncertainty, revealed the difficulties of functioning in the classroom.

The children were both spectators and students. They observed what was happening around them, but at this stage of interaction, they were in school desks that were facing the blackboard. The actions of the actors did not take place as during a typical lesson, only in front of their desks. The desire to follow the trolls required turning in different directions. This constant movement gave the students an experience that went against the norm of sitting upright in a desk. It was necessary to turn around here. This is the first moment of this interaction, in which the viewers experienced first-hand going beyond the norms accepted in the classroom and entering into behavior that could be perceived as deviant.

The initial stage of positive labeling was associated with the encounter with otherness and deviants. It did not assume “positivity” yet. It was characterized by a feeling of uncertainty and strangeness. What is important to our further analysis, we emphasize that self-experience deviant behavior by children was not without significance the fact that we began to experience deviant behavior ourselves.

2. TAMING

gradual taming; getting closer, building relationships; discovering what is different and unknown

The next stage started when the participants and trolls were discovering and getting to know each other. Gradual familiarization led to a process-based relationship-building between the trolls and the audience (Goffman, 1963). Strangeness turned into taming.

Words were not necessary. Gestures came first. During the workshops, children emphasized that at the beginning of the performance they were afraid of trolls, but gradually they became more and more attracted to them. The hardest thing was long eye contact. Children were not used to it. The way they usually sit in the classroom makes them look especially at the teacher. However, in the event, they could closely observe the trolls and their behavior, and notice details that they had not paid attention to before. Staring at each other was explicitly allowed[7].

The taming proceeded through gradual physical approaching each other. After exchanging glances, you could see timid greetings (shake hands, smile, high five). Next, the trolls were introducing themselves. Together with the students, the trolls read the name “TROLLS” from the blackboard, and then invited the children to touch and cuddle up to the pleasant-to-touch fur hanging on the wall.

The characters of the play still did not follow the school rules. They ran, walked on the desks, opened all the lockers, wrote on the blackboard without the teacher’s permission, hid. Both during the performance and the workshops, the children had the opportunity to use the classroom space in a similar way. It took place in an atmosphere of fun and joy, with the sounds of music inviting to dancing. However, several times this met with the teacher’s interference, which was associated with the need to maintain safety. Such situations clearly demonstrated the essence of deviating from school norms in the behavior of trolls, and at this stage also of the students invited to cooperate. The common experience of being outside the school norms, but still in the safe conditions of a theatrical event, was, in our opinion, an important factor in positive labeling – common, somewhat rebellious and unusual fun became the basis for building relationships.

In the taming phase, labeling started to take positive shape. The micro-interactions between children and trolls brought smiles and closeness from moment to moment. By then, strangers had become close, but not the same. Labeling them was inevitable, because they clearly indicated what made them different. However, differences at this stage began to be perceived as an advantage. The fur hanging on the wall was supposed to give a sense of pleasure and relief. It became a kind of sign of trolls, but also a metaphor for a good, friendly relationship. Trolls wanted to give children who were immersed in the reality of school friendship, joy, fun and stress-free relief. This is the stage where positive deviants give their audience insight into their idea. This insight takes place through shared experience – not only of deviant behavior, but also of the values that guide “deviant”.

3. INITIATION

removing masks, discovering the truth; entering a deeper level – because of the previously built taming – no longer causes fear; the glue for positive label is the relationship and shared experience (we did it all together, we “broke” the norms together)

The last element of the process of getting to know the Trolls was the moment when performers and spectators sat together on a fur carpet. Barriers made by school desks were already disappearing. While the arrangement of space was changing, the relationship was changing, too. From a hierarchical, school-based one, focused on student-teacher contact, to a more equal one, with the possibility of looking closely at everyone. In such a meeting, the actors took off their masks. It was like the final moment of the process of getting to know each other and taming the trolls, which became a symbolic meeting with disability. We observed the curiosity and attentiveness of the children. Sitting close to each other, the actors greeted the audience again, this time saying their real names. The children answered the same. There were handshakes, hugs, touches. The fur rug invited everyone to lie down and relax. Everything in an atmosphere of peace and joy.

At this stage, which we call initiation, the children were invited to discover the next level of the trolls’ features. They saw that the trolls were different not only because they behaved differently from what was accepted at school, but also because they had something special that was showed by their different appearance. We no longer observed the bewilderment and the sense of strangeness. In this phase in the labeling process, the consequence of earlier events began to become apparent. The viewers had already given a positive label to the troll character and its behavior – they liked each other, established a relationship, built common experiences. When the masks were removed, the process of stepping out of the role began, in which a new topic appeared, namely the actor’s disability. The positive label given did not come off with the mask. Because of the established relationship, the label was maintained and moved to the next level during the workshop meeting.

4. INCLUSION

workshops; conversation; exchange; adopting the idea of a new look at otherness as one’s own; acceptance; finally, otherness put in the spotlight (patch)

The workshops took place after a short break. The time spent together on fur in closeness at the end of the play was for building deeper relationships. During the workshop, the children were bolder and they initiated interactions themselves. This stage was the next step in getting to know people with disabilities. First of all, children got to know the actors through conversations: the initial one, in which one of the actors talked about himself, his interests, and being an actor, and the final one, during which he took part in the discussion, shared his opinion, and expanded children’s knowledge about him. He made himself known also through movement activities built on the common experience of the performance and fun. Disability was elevated to the rank of an element of identity of which the actors are proud. It resonated as a theme in the actors’ stories, but also as a result of questions posed directly by the children, or coming from the theater pedagogue who co-led the workshop whit the actor. Observations and reports from them indicated noticeable reactions of the participants listening to the actors’ statements. Many times, the moments when the actors spoke during the workshop were moments of stopping and increased attention. It was noticeable that the children focused with interest. The topic discussed and the manner of speaking drew their attention, increased close observation, and prompted them to ask questions that deepened the discussed topics. It happened that the children referred to the subject of disability, paying attention to the features of appearance, way of speaking or moving. Sometimes, the topic was discussed deeply – children asked about the causes and duration of the disability. There were also talks about the name of Theatre 21 and chromosomes. There were also some questions about the previous children’s experiences with disabilities, which gave a lot of individual stories.

Parallel to the topic of disability, which appeared in the initiation stage in the labeling process described by us, an earlier subject, i.e. the theme of school, was still alive. Being confronted with a disability reminded children of the challenges they face in the school reality. These were stories related to exclusion and the consequences of stereotypical thinking about others. It was helpful for the moderators to return to the common experiences of the performance and the emotions associated with the encounter with the trolls. The topic of taming otherness, which previously could have had an unfavorable opinion, was discussed. The conversation also disarmed the theme of duplicating untrue opinions about a certain topic or generalizing opinions about one person to the entire group he/she represented. The children also shared experiences in which the false information concerned themselves and/or indicated situations in which they excluded others.

The trolls entered the classroom with a critical, deviant view of the school system, but at the same time they showed students their world. They gave subversive experiences that could happen during the performance, but they also opened up the children’s earlier experiences related to the school space, otherness, and disability. They built a relationship both through a community of experiences here and now, and the similarity of experiences elsewhere, giving a safe space for understanding them and finding solutions for the future. We called this stage of positive labeling inclusion, because it was about incorporating the idea into the way of seeing the world by the spectators, i.e. the children. It was the idea with which the positive deviants entered. The trolls were no longer shocking aliens. They were actors with disabilities who proudly told about their ways of experiencing otherness. Differences were made clear, so the inclusion was not a naive conclusion that we are all the same. We are different and that is the value! Thus, the children gave a positive label to the actors of Theatre 21, creating a common universe of experiences and values – a micro-community composed of an artistic team and students.

The final symbol of this label becomes a fur patch that remains in the classroom as a souvenir of the meeting with trolls. The children placed it where they chose. This decision was often accompanied by long talks and negotiations, followed by a final thanksgiving, depending on the energy of the group and the ideas of the children (e.g. a common shout, troll dance).

Graph 1. The positive labeling process

Source: own study. Graph made in CANVA.

In the article, we have shown that the entry of trolls into a Warsaw primary schools is more than just familiarizing one with differences. The event involves the process of positive labeling. The reverse of social deviation that we observed prompted us to describe the characteristics and stages of positive labeling, using Trolls as an example. We noticed that what the trolls do is deviate “upward” from social expectations and be rebellious. This rebellion, along with the actions they take, has an altruistic character. It is driven by a desire to achieve positive effects – to showcase diversity as a positive thing.

Erving Goffman’s idea about the nature of social interactions assumes that when people are in a group, they tend to either gather new information about others or utilize the information they already have (Goffman, 1963). The analysis of Trolls indicated how the potential of this statement was utilized. The creators based it on stigma to slowly and safely turn it into a positive label. The process occurred toward both trolls and people with disabilities.

The initial bewilderment that came with the situation full of novelty and uncertainty exposed the challenges associated with functioning in the classroom. It also showed confirmation for the validity of building relationships in school based on closeness, mindfulness, and subjectivity. However, for the children, it primarily gave them the experience of encountering otherness. It became the first and very important step of labeling. Since a multitude of signs and symbols provide opportunities to expand both information and sources (Goffman, 1963), the presence of trolls in the classroom gave the viewers the potential for exploration.

This exploration gained momentum in the stage we called taming. It was at this stage that positive deviants gave their audience insight into their idea. This insight occurred through shared experiences – not just deviant behaviors, but also the values that drive the “deviants.” This was made possible by bringing about shared experiences – rebellion, play, discovery, and relationship-building.

The initiation stage illustrates the statement that when reality is intentionally presented in a way that creates the illusion of authenticity for the audience, that illusion can become their reality, which they accept as true (Goffman, 1963). Trolls revealed this truth when they took off their masks. The overturning of a certain social order in this event was limited to theatrical fiction. However, in reality, a relationship was established that continued even after the actors left their roles. Theater became a tool for talking about otherness, only to later observe it without theatrical disguise. Fiction turned into reality when the relationship between the trolls and the children did not disappear on the path leading from one to the other. The question of generalizing this stage to other positive labeling processes devoid of theatrical framing has its answer in replacing the word “theater” with “interaction”. Taking off masks is nothing more than a deeper entry into a dialog with a positive deviant, which, owing to experiences from previous stages, does not disappear under the influence of discovering previously unknown characteristics.

The culmination of the positive labeling process becomes inclusion, understood as the inclusion of people marked by the ideas and values brought by the positive deviant into the world. Combining them with one’s own experiences helps to accept and broaden one’s own perspectives.

Examining the course of the defined stages, we have paid attention to the essence of their processual character. The stages were interrelated and impacted each other. It is worth emphasizing that the idea of social labeling is inherently fluid, highlighting that nonconforming behavior can only be comprehended through the lens of ever-evolving conditions that reflect intricate interactive processes (Schur, 1969).

What does this mean? Theater allows for the experience of change in safe and comfortable conditions. For us as sociologists, it has given us a chance to observe, study, and describe regularities that at a general level may constitute an important answer to the question of what elements build positive labeling and have an impact on changing the perception of the different-foreign to the different-close.

Cytowanie

Maria Babicka, Aleksandra Zalewska-Królak (2023), Trolls at School: A Story about the Stages of Positive Labeling of People with Disabilities Through Micro-Interactions, „Przegląd Socjologii Jakościowej”, t. XIX, nr 3, s. 14–33 (https://doi.org/10.18778/1733-8069.19.3.02).

Babicka Maria, Kalinowska Katarzyna, Zalewska-Królak Aleksandra (2019), Przenikanie przez szczeliny – Teatr 21 w szkole. Raport z ewaluacji projektu O!Swój, Warszawa: Fundacja Teatr 21.

Becker Howard S. (1963), Outsiders: Studies in the sociology of deviance, New York: Harper Collins Publishers.

Berger Peter, Luckmann Thomas (1967), The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge, Garden City–New York: Doubleday.

Blumer Herbert (1986), Symbolic Interactionism: Perspective and Method, Berkeley: University of California Press.

Czarnowski Stefan (1956), Kult bohaterów i jego społeczne podłoże: Święty Patryk, bohater narodowy Irlandii?, [in:] Stefan Czarnowski (ed.), Dzieła, vol. IV, Warszawa: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe.

Dąbrowski Kazimierz (1967), Personality Shaping Though Positive Disintegration, Boston: Little Brown.

Erikson Kai T. (1962), Notes on the Sociology of Deviance, “Social Problems”, vol. 9(4), pp. 307–314.

Garland-Thomson Rosemarie (2020), Gapienie się, czyli o tym, jak patrzymy i jak pokazujemy siebie innym, Warszawa: Fundacja Teatr 21.

Godlewska-Byliniak Ewelina (ed.) (2017), Odzyskiwanie obecności. Niepełnosprawność w teatrze i performansie, Warszawa: Fundacja Teatr 21.

Godlewska-Byliniak Ewelina, Lipko-Konieczna Justyna (2016), 21 myśli o teatrze, Głogowo: Fundacja Win-Win.

Godlewska-Byliniak Ewelina, Lipko-Konieczna Justyna (eds.) (2018), Niepełnosprawność i społeczeństwo. Performatywna siła protestu, Warszawa: Fundacja Teatr 21, Biennale Warszawa.

Goffman Erving (1956), Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, London: Penguin Books.

Goffman Erving (1963), Stigma. Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity, London: Penguin Books.

Kalinowska Katarzyna (2018), Wchodzenie „tylnym wejściem” jako wariant zmiany społecznej. Raport z ewaluacji projektu O!Swój. Edycja 2018, Warszawa: Fundacja Teatr 21.

Kalinowska Katarzyna, Rożdżyńska-Stańczak Kaja (2017), Jak się zerwie izolację, to kogoś może kopnąć prąd. Raport z ewaluacji projektu O!Swój, Warszawa: Fundacja Teatr 21.

Kalinowska Katarzyna, Rożdżyńska Kaja (2020), Separujące i ochronne funkcje izolacji. Narzędzia oswajania inności na przykładzie działalności artystyczno-edukacyjnej Teatru 21, “Przegląd Socjologii Jakościowej”, vol. XVI, no. 2, pp. 80–101.

Kaufmann Jean-Claude (2013), Kiedy Ja jest innym, Warszawa: Oficyna Naukowa.

Kietlińska Bogna (2019), Nie ma wolności bez samodzielności. Działanie Teatru 21 w perspektywie zmiany, Warszawa: Fundacja Teatr 21.

Kłoskowska Antonina (1971), Heroizm i personalne symbole wartości kulturowych, [in:] Janusz Kuczyński (ed.), Filozofia i pokój, Warszawa: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, pp. 37–54.

Krajewski Krzysztof (1983), Podstawowe tezy teorii naznaczania społecznego, “Ruch Prawniczy, Ekonomiczny i Socjologiczny”, vol. XLV(1), pp. 225–245.

Kwaśniewski Jerzy (1976), Pozytywna dewiacja społeczna, “Studia Socjologiczne”, no. 3(62), pp. 215–233.

Kwaśniewski Jerzy (2012), Czy istnieje dewiacja społeczna?, “Prace Instytutu Profilaktyki Społecznej i Resocjalizacji”, no. 19, pp. 63–88.

Lemert Edwin M. (1951), Social Pathology: A Systematic Approach to the Theory of Sociopathic Behaviour, New York: McGraw-Hill Book Co.

Lemert Edwin M. (1967), Human Deviance, Social Problems and Social Control, Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall Inc.

Mead George Herbert (1909), Social Psychology as Counterpart to Physiological Psychology, “Psychological Bulletin”, no. 6, pp. 401–408.

Ossowska Maria (1973), Ethos rycerski i jego odmiany, Warszawa: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe.

Pyszczek Grzegorz (2012), Jerzego Kwaśniewskiego pochwała dewiacji pozytywnej, “Normy, Dewiacje i Kontrola Społeczna”, no. 13, pp. 139–160.

Scheff Thomas Jefferson (1966), Being Mentally Ill, London: Aldine Publishing Company.

Schur Edwin M. (1969), Reactions to Deviance: A Critical Assessment, “American Journal of Sociology”, vol. 75(3), pp. 309–322.

Tannenbaum Frank (1938), Crime and the Community, Boston: Ginn and Company.

Teatr 21 (n.d.), Idea, https://teatr21.pl/idea (accessed: 26.02.2023).

Teatr 21 (n.d.), https://teatr21.pl (accessed: 26.02.2023).

Teatr 21 (n.d.), O!SWÓJ / 2017–2019, https://teatr21.pl/oswoj-2017-2019-projekt/ (accessed: 26.02.2023).

Teatr 21 (n.d.), Sezon GAP SIĘ!, https://teatr21.pl/sezon-gap-sie/ (accessed: 26.02.2023).

Teatr 21 (n.d.), Trolle, https://teatr21.pl/show-item/trolle/ (accessed: 26.02.2023).

Thompson Gregory A. (2014), Labeling in Interactional Practice: Applying Labeling Theory to Interactions and Interactional Analysis to Labeling, “Symbolic Interaction”, vol. 37(4), pp. 458–482.

Znaniecki Florian (1974), Ludzie teraźniejsi a cywilizacja przyszłości, Warszawa: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe.