https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2637-760X

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2637-760XUniwersytet Jagielloński

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2637-760X

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2637-760X

Abstract: Enclaves of poverty are spaces of social stigmatization that can foster exclusion as well as enhance the impression of it. At the same time, they are milieus in the lives of specific human beings who co-inhabit and co-create these spaces; they are a home base – a place of safety, one that is the source of satisfaction and identification. The circumstances constituting and distinguishing these specific ecosystems were the inspirations for research conducted in 2014–2016 in enclaves of poverty – located in two large cities and in rural areas in Poland – to identify the ways of valuing and mental mapping performed by people living there. Based on the results of the author’s research, the article discusses three complementary issues covering the ways of identifying a space, identifying with a place and place identity. It focuses on the cognitive and practical value of such findings, which go beyond simplified and generalized thinking about enclaves of poverty, revealing the potentials of various neighbourhoods and the complexity of people’s connections with a place.

Keywords:

mental maps, enclaves of poverty, place identification, identifying with a place, place identity

Abstrakt: Enklawy biedy to przestrzenie społecznie napiętnowane, które mogą sprzyjać wykluczeniu lub wzmacniać jego wrażenie. Równocześnie to środowisko życia konkretnych ludzi, którzy je współdzielą i współtworzą; to przestrzenie domowe, bezpieczne, będące źródłem satysfakcji i identyfikacji. Okoliczności konstytuujące i wyróżniające te swoiste ekosystemy stanowiły inspirację do zrealizowania badań w latach 2014–2016 w enklawach ubóstwa zlokalizowanych w Polsce w dwóch dużych miastach oraz na terenach wiejskich, służących rozpoznaniu sposobu ich waloryzowania i mentalnego odwzorowywania przez zamieszkujących je ludzi. Bazując na wynikach badań własnych, w artykule omówiono trzy uzupełniające się wątki, obejmujące procesy identyfikacji przestrzeni, identyfikowania się z miejscem i tożsamości miejsca. Zwrócono uwagę na poznawczą i praktyczną wartość tego rodzaju ustaleń, które wychodzą poza uproszczone i generalizujące myślenie na temat enklaw biedy, ujawniają potencjały zróżnicowanych sąsiedztw i złożoność więzi ludzi z miejscem.

Słowa kluczowe:

mapy mentalne, enklawy biedy, identyfikacja miejsca, identyfikacja z miejscem, tożsamość miejsca

The space inhabited or occupied by people is an important component of their daily experiences. Not only can it facilitate orientation and give a sense of security and satisfaction (e.g. Lewicka, 2012), but it can also stigmatise and foster exclusion. The social stigma attached to a place can become a stigma for its inhabitants, with negative associations about a place being transferred onto its inhabitants (cf. Czykwin, 2008). The space itself can also be negatively marked when inhabited by people with features disqualifying them socially. Stigmatization of people and spaces combines in the social reception, resulting in socio-spatial exclusions. In this article, I focus on a particular space, namely enclaves of poverty. Such enclaves are usually a milieu in the lives of poor people in which their everyday lives take place. For some inhabitants, they are familiar, accepted places, while for others, they are alien and rejected. These are potentially safe neighborhoods, but at the same time, spaces of social stigmatization (e.g. Willmott, Young, 1957; Small, 2015; Wódz, Szpoczek-Sało, 2016). As such, enclaves of poverty are rarely explored as places of identification, from the perspective of which socio-spatial identities are (re)constructed. This fact provided the impetus for the research, aiming to identify the ways of valuing and mental mapping performed by people living there (see: Nóżka, 2016).

Based on the results of the author’s research conducted in Poland with the participation of residents of enclaves of poverty, the article discusses three complementary issues covering the ways of identifying a space as well as identifying with a place and place identity. Accordingly, when analyzing the collected material, answers to the following questions were sought: 1) Through which characteristics do the research participants identify the enclaves of poverty they live in? What are the attributes of these places from their perspective? How do they create the image of this place?; 2) Do the participants identify with the neighborhood they inhabit? Do they have a sense of being at home? Are they attached to it, and if so, how?; 3) Do the participants have the sense of being in the space? Do they discern its uniqueness? The structure of the article is based on this approach to the research problems.

First, based on the participants’ statements, it describes how they perceive the neighborhood they live in and how they (re)construct its image, which as such influences their own self-perception. Second, discussing identification with the place, the article refers to the participants’ diverse connections to the neighborhood they live in, their sense of being at home, attachments, belongings, growing into and being trapped in the place. Third, it attempts to reconstruct the place identity, which is formed by a sense of “being inside” and the uniqueness and distinctness a given neighborhood. These circumstances were recreated based on an analysis of the content of interviews, sketch maps, and photo walks, which revealed, among other things, the typical ways of being in the space as passers-by, strollers, and inhabitants of it. The above reflections are preceded by a theoretical introduction to the understanding of enclaves of poverty and the formation of local identities, as well as a discussion of the methodology of my own research.

The way of viewing the inhabited space, perceiving it as both a “significant” and a “signifying” place, is a reflection of what is individual, but it also tends to be environmentally negotiated and redefined. The objective of the article is to reflect on the cognitive and practical value of such findings referring to socially-marked areas, as they allow us to go beyond a simplified and generalized view of enclaves of poverty, revealing the potentials of diverse neighborhoods and the complexity of people’s connections with a place. I also aim to demonstrate that this information should be taken into account in decisions concerning the spatial relocation of people and/or revitalization of the spaces they inhabit, which, apart from being poor and degraded, have their own identities and residents associated with them in various ways.

Excluded, degraded spaces inhabited for decades by poor people have long been the subject of research interest, examples being Charles Booth’s mapping of poverty in London (https://booth.lse.ac.uk/), the exploration of the industrial districts of Chicago (Shaw, McKay, 1942), and Herbert Gans’ (1962) ethnographic fieldwork on the everyday life of a working class district of Boston, all of which are part of the debate on the “culture of poverty”, initiated by a series of publications by Oscar Lewis (1961; 1966).

Over time, research devoted to ghetto neighborhoods and enclaves of poverty has developed and encompassed diverse fields (e.g. Walks, Bourne, 2006; Bird, Montebruno, Regan, 2017). As an area of human life, enclaves of poverty have their own specific social, cultural, and geopolitical characteristics (e.g. Dupont et al., 2016; Nóżka, 2020). Among others, the processes of the emergence and establishment of such enclaves have been examined (e.g. Ooi, Hong, 2007). In Poland, the formation and continuation of urban and rural enclaves of poverty is connected to the socio-economic transformation and transition to a market economy in the 1990s. Among the effects of the unprecedented scale of restructuring and deindustrialization at the time were mass redundancies and impoverishment of industrial workers, especially in the extraction, metallurgy, and textile industries (Wódz, Szpoczek-Sało, 2014). This also concerned employees of closed-down state collective farms (hereafter: SCF) (Falkowski, Jasiulewicz, 1994), which had been established after the Second World War as a result of enforced collectivization of land and organization of agricultural workers in production cooperatives. As a result of the socio-economic transformation taking place in cities, owing to the low standard of the buildings inhabited by former workers, city authorities began to arrange social housing, the demand for which increased. Over time, these became home to mostly poor, uneducated, and less resourceful tenants (cf. Warzywoda-Kruszyńska, Jankowski, 2013). In defunct SCFs, meanwhile, most company-owned housing was sold to former employees at preferential prices. Yet, this did not improve their situation. Unattractive locations and the low standard of flats made them difficult to sell, thus tying people to the place, which was usually isolated, without access to cropland and potential workplaces (cf. Falkowski, Jasiulewicz, 1994; Tomaszewska, 2001). Therefore, enclaves of poverty in Poland formed in both rural and urban postindustrial sites, as well as in city-center and peripheral areas where buildings with government and social housing were over-represented.

What descriptions of enclaves of poverty appear to have in common is an accumulation of various kinds of deficiencies, deviations, and pathologies in their area (see, e.g., Jones, 2010), where the problems of unemployment and crime are more acute. These are areas that are rarely entered and difficult to leave, as demonstrated by research on housing mobility in poverty enclaves (Bolt, van Kempen, 2003; Kearns, Parkes, 2005; Warzywoda-Kruszyńska, Jankowski, 2013). At least three factors contribute to this. The first one is the poor condition of transport and housing infrastructure as well as the lack of investment and an appropriate economic base, which limits the residents’ potential, isolates them, and results in their unemployment. Secondly, inhabiting enclaves of poverty is the result of spatio-economic segregation, which means the concentration of the most disadvantaged people in the least advantaged areas. Thirdly, the mentioned circumstances have a devastating effect on the image of the place and the reputation of its inhabitants (Lupton, Power, 2002). As such, enclaves of poverty are considered to be pockets of intense deprivation, requiring intervention, investment, and social support (Nóżka, 2020).

Certainly, enclaves of poverty are areas of exclusion, but according to Mario L. Small, the focus on the deficiencies of the enclaves stems from the fact that many simplified narratives have grown around these spaces, with stereotypes remaining in social circulation, causing the simplification and generalization of their image (Small, 2015). The potential of these areas is not always recognized, especially in terms of the appearance of activities, social movements, and manifestations of solidarity unknown in richer areas of the city and in the suburbs (Annan, 2003; cf. Nóżka, 2020). The fact that enclaves of poverty can constitute local communities is demonstrated, among others, by fieldwork in the Bethnal Green district of east London conducted by Peter Willmott and Michael Young (1957). Fieldwork carried out in the Lipiny district of Świętochłowice in Poland also confirms that, contrary to stereotypes and negative views on the place, it is characterized by strong social bonds, willingness to help among neighbors, and a sense of group solidarity (Wódz, Szpoczek-Sało, 2016). Other studies provide evidence that a sense of belonging and identity with a poor neighborhood may be shared and transmitted between generations (Frost, Catney, 2020). There is no doubt that the inhabitants of enclaves of poverty attach various meanings to them: from sentiment and belonging, via ambivalence and indifference, to open hostility (e.g. Nóżka, 2016). It is, therefore, important to emphasize that, depeding on knowledge and experience, the same components of a space – not only from the perspective of an outside observer, but also for the inhabitants of the enclaves themselves – can be seen in different ways by different people who construct different visions of the same space (cf. Nęcki, 2004). These diverse ways of perceiving a space constitute its mental representations, identification of which can provide a source of knowledge on socio-spatial identities (cf. den Besten, 2010). Among the ways we can recognize these are interviews and sketch maps (Lynch, 1960; Downs, 1970; Downs, Stea, 1973).

The qualities people attribute to a place, on the basis of which they construct their ideas of it, are intertwined with ways of identifying with the place. The essence of this process is caring about the place’s positive image, a declared desire to remain there, liking it, a sense of security, attachment, a sense of belonging, and rootedness in the place (cf. Lewicka, 2012). Attachment as a specific attitude toward a space is defined through the prism of three components: affective, cognitive, and behavioral. The first one is an emotional bond, feelings, meanings, and symbols resulting from the physical characteristics of a place and experiences involving real and symbolic dependence arising in relationships with other people. The second one involves familiarity with a given space, knowledge about it, and everything that is considered significant. The third one constitutes individual and social actions taken within the framework and for the benefit of this space (see Bańka, 2011: 8). It is on this attachment that a sense of belonging is built, which may be habitual (everyday rootedness), conscious (“rooted by choice”), or relative (Hummon, 1992). It is a form of affiliation with the place, which expresses the social dimension of the bond connecting the individual with a place (Mesch, Manor, 1998) as well as the emotional dimension (cf. Proshansky, Fabian, Kaminoff, 1983). Attachment may also be functional and result in the emergence of place dependence. The place provides a property and conditions allowing them to meet a variety of needs. Space perception stems from two processes. The first one involves an assessment of the potential of a given place to meet the needs and objectives of the unit, while the second one is to compare the neighborhood with other areas where it is possible to meet these needs. Place dependence is also connected with “embedment”, which is another factor determining the relationship with the inhabited neighborhood. The formation of this type of dependence is fostered by sites that significantly satisfy human needs, sometimes resulting in “getting stuck”, or “sinking deep into” one place. However, rootedness is mentioned as the most intense form of ties with a place, which is a reflective relationship between safety and comfort typical of home (see Tuan, 1974; Stegner, 1992; Bańka, 2011: 9). People might also not identify with a place and have a sense of “placelessness” and alienation (Hummon, 1992).

Place attachment, according to Williams and Vaske (2003) is a two-dimensional construct that expressed both place dependency and place identity. For the purposes of this article, I assume that place identity goes beyond attachment and belonging to a place, which, in the experience of inhabitants, may be separate. I define place identity through interiority or a sense of being inside, experiencing the place as one’s own and something close, expressed through recognition of its uniqueness and distinctiveness (cf. Relph, 1976; Żmudzińska-Nowak, 2010; Lewicka, 2012). I assume that, through becoming settled and a feeling of a lack of alternative, people can be attached to and dependent on a place, without a sense of its identity.

Aiming to recognize the ways of identifying the space of enclaves of poverty, identifying with a place, and place identity, I will refer to the results of my own research carried out in 2014–2016.[1] The research was conducted in both rural and urban areas. The selection of the sites of the research was purposeful, based on three different types of enclaves of poverty. One is located in a postindustrial area in Łódź; the second is in Warsaw in a non-postindustrial area and, like the first one, regarded as a dangerous place in the social circulation. This was determined in reference to the so-called anti-ranking of districts based on the results of research conducted among residents of cities by property development companies and housing websites. The third area involves rural enclaves of poverty, i.e. estates with former-SCF flats owned by their inhabitants located in the municipality of Lewin Brzeski in the Opole Silesia region. The research area as a space representing enclaves of poverty was determined based on data from available academic publications, reports from local research, and reports of municipal social assistance centers, which were listed as examples of degraded and socially-isolated areas, with an overrepresentation of social housing and poor and unemployed clients of social services. On this basis, the opinions about these places circulating in society were determined; they were also collected during the interviews with their inhabitants. The names of these places, as well as of the research participants, were anonymized for ethical reasons. Their disclosure was deemed unimportant to the research results, but may result in the stigmatization of their residents, and in the case of small rural estates, two or three blocks located in former SCFs, it could potentially contribute to their identity being revealed.

In total, 32 people from towns took part in the study – 16 residents from the “first” enclave of poverty located in Łódź (8 women, 8 men), 16 residents from the “second” one located in Warsaw (8 women, 8 men), and 21 residents of rural settlements located not far away from each other on the site of former SCFs, but dispersed through the municipality of Lewin Brzeski, hereafter referred to as the “third” enclave of poverty (12 women, 9 men). The participants were social welfare clients for economic reasons. They were aged between 25 and 67, with a Polish ethnic background, and have been living in their current place of residence for between four years and several decades. Some have lived there all their lives, while others moved there in order to join their partner or because they obtained social housing in the area. On this basis, the research participants are differentiated between permanent residents (R) and strangers (S), which was taken into account when coding their statements.

The study, which lasted about an hour and a half, was carried out in the participants’ home and also involved taking a walk around the area. The selection of the sample was purposeful and based on the accessibility of the participants. After carrying out a reconnaissance and inventory of the space, it was determined that residents of the estates – both urban and rural – in which the research was planned were distrustful towards’ researchers; therefore, social workers familiar with the community took part in the recruitment process. They established the first contact with the residents, explained the purpose of the research and the manner of its implementation, and then verified the consent to meet the researcher. During the meeting, the researcher confirmed the subject matter and procedure of the research, obtained consent for audio recording and informed participants of the possibility of withdrawing at any moment. In this manner, the right of the participant to informed and voluntary participation in the research was secured.

The research methods used in the project were inspired by the work of Kevin Lynch (1960) and Peter Gould and Rodney White (1986). The former explored the physical structures of space by interpreting imaginary sketches, and the latter analyzed the spatial preferences of respondents obtained through interviews. In addition, mobile visual methods were applied, taking into account that people collect and activate information about the environment through their senses and direct experience of space. Thus, various methods of extracting, externalizing, and using people’s knowledge contained in mental maps were employed. The first consists in visualization, the second in recounting, and the third in visiting and experiencing.

Visualization was related to the imaging of spatial knowledge by the respondents, which consisted of drawing sketch maps of the neighborhood. The participants received a sheet of paper, in the middle of which the point symbolizing the place of the research was marked. They were then asked to sketch a map of the immediate area, what they remembered and what would fit on a piece of paper, and to describe what they were drawing.

The recounting process included describing drawings and sketches, answering questions contained in the interview questionnaire, and free statements of the respondents during the photo walks. The interview questionnaire consisted of closed, semi-open, and open standardized questions that concerned issues related to the identification, valorization, and use of a given space, e.g. What would the respondents call the inhabited area? How long have they been living there? Do they like to walk around the area? In this manner, additional information was obtained to determine the potential knowledge of the mapped space, and associated knowledge structures were activated. Questions were also asked about their sketch maps, including: Does the participant like the area? Is this a good neighborhood? Is it safe? Does it feel like home?

Visiting and experiencing was associated with the implementation of photo walks. The places depicted earlier by the participants on the sketch map and described during the interview were visited and photographed. Photographs were taken to encourage the participants to focus their attention on the elements of the space being walked through. The collected material complemented and enriched the data on the ways of imagining and valorizing the area inhabited by the participants.

Analysis of the results of research using mental maps is not standardized. Taking into account the research objective and diverse data collection methods, the analysis considered the form and content of the sketches as well as the connections between the graphical contents and the research participants’ statements during the interview and photo walk. In the reconstruction of the ways of understanding and being in the space of inhabitants of enclaves of poverty, each sketch was first analyzed individually. The cartographic and non-cartographic contents the participants included in the drawings were collated along with the information collected from them in the interview. Next, the similarities and differences between the maps were compiled and categorized, taking into account the buildings and elements of road infrastructure, their distribution and mutual links, and the meanings attached to them. In this article, I present the detailed results of this analysis, which revealed the ways in which the research participants identified the place, their identification with the place, and place identity, illustrating them with the sketch maps and quotations from the participants’ statements representative of these findings.

The research participants identified the space they lived in from the perspective of diverse attributes and factors. First of all, attention should be drawn to the way a space is referred to. In response to the survey question: What would you call the area in which you are right now?, taking all answers into account, one-third of the participants gave the name of their district, estate, or village. Usually, however, their response to this question referred to their personal associations with the district, as well as the general public view of the neighborhood. These associations were related to its physical aspects (location and infrastructure), as well as the social (categories of residents and the specifics of the relationship) and symbolic ones (values and marks/meanings). The first of these referred to various categories or types of space (e.g. a small settlement, housing estate, industrial district, suburb), location (e.g. outskirts, district center, far from civilization and the world, city beyond city), transport (e.g. everywhere is far and there are no buses, good access, it is easy to get to different places), and supplies (e.g. there is a good supply base, shops, the shopping center begins here, there are playgrounds, there is nothing specific here, they do nothing for children). Furthermore, the area was observed from the perspective of two types of confinement, which were connected with the way it is seen by people from the outside and perceived by those who live there: a) externally marked – isolation and social appointment (“Lost land, forgotten by everyone” (33.3.M.R[2]); “Slums, so they sometimes say” (43.2.F.S)); and b) internally marked – distinctiveness of the place and its inhabitants (“I am not, but normal people are afraid to walk in [this area]” (45.2.M.R)). Participants also expressed contrasting positive and negative opinions on the quality of people living in the surrounding area (“We all know one another here, we can count on each other, on their help” (37.3.M.R); “Drunkenness, trouble-makers” (43.2.F.S)).

The research participants living in enclaves of poverty usually indicated its ghetto-like nature. Firstly, they drew attention to the location, separating the neighborhood. Secondly, they emphasized the bad quality of the space as evidence of its degradation, including terrible communications, transport, and/or service infrastructure. Thirdly, they gave the reason for the space closing the door on other residents of the city/municipality as the specificity of the social tissue. Space isolation was also indicated by opinions according to which the inhabited area and/or its residents are neglected or less favorably treated by investors, administration, and local authorities. In the assessment of people’s own place of residence, the poverty of the population was relatively rarely mentioned, with a total of five respondents expressly referring to this question, not necessarily indicating it as a specific type of deficit.

Pointing to the enclave, and at the same time, the worse nature of the area, some of the participants directly referred to the negative opinions of other people, thus emphasizing a socially-created image of one’s area and its inhabitants, for example: “People say that this is a backwater, for outcasts from society” (38.2.F.R). All participants who noted the negative opinions about the area they inhabit in the social circulation also disputed them, emphasizing that the area is nice, safe, etc. Such measures – meaning the created image of a space – bore traits of universal strategies and could be identified, with different intensity, in the statements of all the participants who, for a variety of reasons, felt at home in the areas inhabited by them. To classify the ways in which the participants presented and (re)constructed the image of the space, let us start from the fact that they used all sorts of defensive strategies of a palliative nature, aiming to eliminate the unpleasant tension associated with a poor-quality living space. These strategies include downward comparison: “So be it that I do [like it here] there are worse hellholes” (27.3.M.R). Defensive fatalism was also linked to this strategy. This procedure is designed to show the area as one of many. Some participants argued that the undesirable circumstances, which are also a factor identifying the particular area, are nothing extraordinary, but occur in every area: “You can be beaten, it happens, but it can be on any street, anywhere” (46.2.M.S).

Participants also used strategies of whitewashing the image of their own area – especially when they were inevitably and inextricably tied to it. They noted that the area is not unequivocally bad, that positive changes can be observed: “I think it is accessible for the surroundings. It’s certainly prettier than before. A lot has changed. It is well-cared for, the buildings are renovated, it’s safer, with investments, it’s clearly apparent; it has changed for the better. It’s not the same district” (52.2.F.R). Such actions aimed at improving the image of an inhabited space – without denying its negative image – are part of compensatory strategies (cf. Baumeister, Jones, 1978). While not disputing the reputation of the surrounding area and/or its occupants, participants enriched the knowledge about it with new, positive information: “The fact that people are evicted is not because they are on the social margins. Sometimes their life situation forces them, they have no choice […]. Maybe it’s not a safe area, but it’s peaceful. There is peace and quiet here, no noise” (38.2.F.R).

A number of participants presented an image of the area through objective and subjective associations. They mentioned famous people living in the neighborhood, presence of people from the outside, media interest proving its attractiveness, as well as location of facilities regarded as prestigious: “There is a beautiful music school, recently renovated, it was shown on TV” (14.1.M.R). Some participants distanced themselves from what is negative and what could be associated with the area they inhabited. They indicated that undesirable circumstances occur or escalate outside their place of residence. Their own area was described by displaying its exclusivity and uniqueness in relation to other spaces: “This is my backyard, and the entire district is well-cared for. On this side, north of me, to the east, it is a ruin, the poorest people in the city live there” (10.1.M.R).

These strategies seem to confirm the conclusion that the value assigned to a place is of great importance for the self-image of its residents (Lewicka, 2004: 275). Strong and positive ties with a place are one of the key conditions for the integration of individual and social identity. For people living in ghetto-like spaces, it becomes a cognitive challenge. This means finding and making sense of life experiences, also those resulting from staying in unsatisfactory surroundings. It is a cognitive mechanism of perceiving – potentially and actually – a discrediting situation in a manner that is consistent with expectations, as part of something predictable and controllable (cf. Frankl, 2009). This way of identifying a place and one’s own acceptance of being in it can be heard in the words of a participant who said: “I like this area because I live here. If I lived somewhere else, I would like another one. You want me to say that I don’t like it? Life wouldn’t make sense then. If you lived somewhere and didn’t like it, what sense would it make? You’ve got to like what you have” (33.3.M.R).

A living environment that people choose or which is given to them must meet their basic needs for roots, identification, and acceptance (Lach, 2001: 129–130). What, then, if these conditions are not met and their achievement is significantly limited? The above quotation reveals the existential logic which is sometimes realized, verbalized, and concealed in different ways in cognitive strategies and everyday practices. It is also sometimes denied, intentionally masked, especially when realizing that these or other circumstances that define one’s own life situation may become a personally discrediting factor.

Identification with the place was discussed by referring to the concept of attachment and a sense of being at home. Let us note above all that a place that is known and familiar neutralizes risk factors and protects people from all kinds of forms of manifesting them (e.g. I know what is where, I know people, I know what to expect from them and how to react). Attachment to place appeared in the participants’ statements together with a declared sense of control over events, privacy, and peace. Secondly, the research participants usually pointed to place dependence, meaning an attachment in a functional way, as this allows them to satisfy various needs, including those that they think could not be fulfilled elsewhere. As one participant said: “Nobody nags me here […]. When I lived with my mother-in-law, she did so, and I wanted to have a place to call home, have peace of mind” (26.3.F.S).

A sense of place dependence encourages stability, or even stagnation manifested by limited intentions and capabilities of spatial mobility. This is due to a number of circumstances: from financial issues, via social competence, to the fear of leaving a safe enclave. The research participants experienced embedment, being trapped in the place, and in extreme situations also rootedness in place. The predominant theme which appeared in participants’ utterances was growing into a place, associated with getting used to it: “I grew up here, gave birth to my child, I have become accustomed to it and wouldn’t change anything [this area] is a part of me” (17.3.F.R).

Place dependence, meaning a connection with it, does not necessarily form on the basis of the positive aspects of knowing it (Stedman, 2003). The participants’ statements show that this may also result from an automatic, unreflective process of becoming at home in a space and growing into a place. As one participant said: “for those indigenous people, there is no other world outside this area”. Some participants confirm this observation, sometimes even signaling the existence of a specifically rigorous tie with a place – resulting from a sense of necessity or coercion: “I’ve been living here for ages. Where would I go now? I’ll stay here forever” (31.3.M.R).

The above factors in forming relationships with a place can manifest a syndrome of dysfunctional attachment, called homesickness (Fried, 2000).

[I feel at home] I’ve been here for so long and I’ve gone through so much. I can say that I am at home. I miss home when I leave, I want to come back as soon as possible. To see my old place and grandchildren (24.3.F.R).

Individuals’ own place is usually the one where they grew up, where they have friends and people they like, who create a specific kind of rhetorical community, which means that: “they are understood without any major problems and, at the same time, they understand their interlocutors without the need for long explanations” (Descombes, 1987: 179 after: Augé, 2011: 74). Overall, most of the participants stated that they feel at home in the area they inhabit. When talking about the feeling of being at home, three main factors were identified. Firstly, they pointed to factual links with the place: possession, ownership, knowledge of the area.

I have an apartment, here I have something of my own. I’m safe because I have a flat (36.3.M.R).

[I feel at home] at the moment […]. [Although] I have no guarantee that they will not change it because the owner appears, for the time being this is my place [the speaker is referring to the flat she is currently residing in and she has lived in the same neighborhood since birth, but in various homes] (32.2.F.R).

The next group of factors that determined the fact that participants felt at home in a given area were participants’ associations: relationships with people, friends, family.

Here I have friends, parents, family […]. I have safety, everyone will stand up for me if something happens, everybody cares for me (01.1.F.R).

The third group of factors can be referred to as emotional associations with the environment, a sense of pride, directly expressed affection. Usually, this category of factors was related to upbringing, being born in a given place.

I grew up here so there are a lot of nice, cool memories […] neighbors from my childhood are still alive, there is the atmosphere of kindness, neighbors visit each other, thanks to such memory there is a sense of community (10.1.M.R)

The feeling of being at home was also associated with autonomy. People’s house or other building was not only considered a safe haven but also an asylum where they could hide from the unaccepted world. This type of dependence on place, built on a belief in the hostile outside world before which it is best to conceal one’s own problems and shut oneself at home, is also corroborated by other research conducted on the terrain of former SCFs (Stanny-Burak, 2005). Two of the research participants did not identify with any place, saying that they did not feel at home anywhere and felt alienated. There were also people who missed their previous place of residence and the people from the neighborhood they had had to leave:

[I do not feel at home] It is a new neighbourhood, a new place. I feel at home in the place where I was born, an area and people that I know well, I remember them fondly (22.2.S).

One participant who was evicted from his previous flat located in another enclave of poverty in this same city did not identify with his current place of residence, spending time in his previous neighborhood and saying that he would like to live there again: “It is ugly and grim here. […]. I have to look behind me all the time, I have no security here. Where I lived it is nicely wooded, I grew up there, I know every nook and cranny” (09.1.M.S). He does not like the place where he lives at present, seeing it as an alien and hostile space.

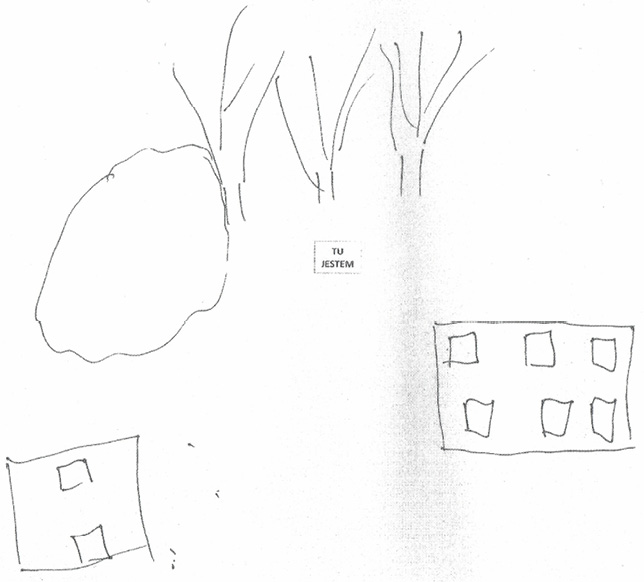

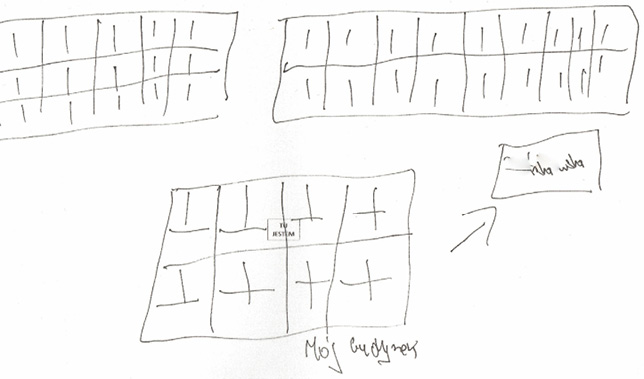

People create cognitive patterns while interacting with the existing architectural and natural spaces, usually using specific fragments of this space, driving and walking along a few or a dozen routes that connect them with offices, institutions, places for shopping, leisure, children’s school classes, and meetings with friends. These circumstances concretize the human existential space. To a large extent, the sketch maps showed the typical routes and mobility areas of participants who directly defined the neighborhood through places to be and to visit. Information shared by the participants concerning what was on the maps and what was not and why constitutes an important source of knowledge about place identity. A formal note might be a starting point for discussing the identity of the place from the perspective of the sketch maps produced by the research participants. While drawing a diagram of the nearest area, each participant had an A3-size sheet at their disposal and was asked to draw as much as would fit into the sheet. It was exceptional, however, for participants to use the entire sheet to draw their map. It is also important to note that the maps of the area were sometimes more similar to a path, rather than a cartographic map (see Figure 1, Figure 2), while others were restricted to several objects. Elements of communications and transport infrastructure usually appeared on the maps and included pavements and the roads the participants walked along, saw, or knew. It is evident from the analysis of the maps drawn by the participants that the paths are their integral element – sometimes the only one included in the maps – without what they described as less important items such as houses/buildings.

Examples of quasi-cartographic sketch maps:

There were also five maps on which roads did not appear; this concerned only the drawings by participants who, regardless of the length of the stay and place of residence, saw their neighborhood through at least one of the following characteristics: dangerous, alien, ugly, bad. The lack of roads and other elements of communications and transport infrastructure on the maps occurred together with reluctant and limited movement around the area.

Examples of sketch maps without paths:

Some of the maps made by people living in enclaves of poverty do not seem to support the thesis that increasing knowledge about the neighborhood leads to cognitive maps becoming more and more similar to cartographic maps (Bell et al., 2004: 113). The way of valuing the surrounding area seems to be an important circumstance here, and the phrase “knowledge about the environment” needs further clarification. The mere fact of inhabiting a particular area since birth as well as everyday use of roads, utilities, and service infrastructure is not reflected in the knowledge about it, as confirmed by the descriptions of the sketch maps of both rural and urban enclaves. What is striking in the participants’ utterances is limited intensity of what could be called being in a place and relationship with a place, especially when the neighborhood is perceived as extremely unattractive. As examples, I will quote passages from the descriptions of the sketch maps of inhabitants who declared that they had lived in a given place since birth and liked the neighborhood, but also thought it was an unattractive and/or dangerous place:

My house is here. Opposite it there’s a school. Here there’s a shop on the corner, a pharmacy, apart from that there’s nothing interesting (12.1.M.R)

There’s a housing block here. Standing there. You go on further, that way. Another block. There are only blocks. There’s nothing interesting here (28.2.F.R).

Most permanent inhabitants of urban enclaves identified not so much with the district they lived in as their immediate neighborhood, own backyard or tenement block, and its residents (Nóżka, 2020). It was their relationship with this “microworld” that the respondents highlighted; they felt included in it and they excluded strangers from it – and this was also confirmed by the statements of people who had not lived in the enclave in question since birth:

I have to look behind me all the time, I have no security here (09.1.M.S)

I’m not from here, and people like me are treated here… Well, they let you know you’re not from here (48.3.F.S).

Let us also note that sketch maps were close to cartographic ones primarily on drawings by people who lived in the given area in an acceptable way, and then among residents with long experience. In the process of drawing a map and/or during a photo walk, some people stressed the unique nature of the place and its autonomy compared to other parts of the city. For example, parts of the descriptions of the sketch maps of people living in a neighborhood since birth show that they see them as attractive and safe places:

There’s a theater here, currently being renovated. Not far away there’s the famous former Jewish mansion, which they now want to sell to private […]. And here is my building… (14.1.M.R).

My neighborhood is well-known, it’s a recognizable place. […] Basically, anyone you ask knows where X street is [the name of the street the speaker lives on]. I think every Pole, every Varsovian, should know that… (18.2.F.R)

Such descriptions were very rare, used exclusively by individuals who were strongly reactive to what is in the space, who in part of this section were classified as the so-called inhabitants of the space (and less frequently strollers).

Different associations and functions assigned to space emerge from the analysis of how the participants perform photo walks. The more the participant felt embedded in or connected to a given neighborhood, the more detailed were the descriptions of the route taken during the photo walk. They went beyond the mere characteristics of the route and included information about what is going on in the area, how the space looks or changes, and sometimes also highlighting its uniqueness by pointing to various historical events, the characteristics of buildings, and its famous inhabitants. The way the space is experienced and the abundance of impressions related to walking around did not depend on how remote the destination indicated by the research participant was. Some of the participants completed the route in silence and did not want to talk a lot about the space despite repeated encouragement on the part of the investigator. There were also those who chose close destinations, but spoke a lot and shared their memories. Based on analysis of the content of the sketch maps and the course of the photo walk, three ways of being in the space can be identified, described as: passer-by, stroller, inhabitant of the space.

A passer-by was a person who crossed the neighborhood while going to a specific place/point (shop, train station, bus stop), treating it as a transit space. Participants from this category were normally unaware of the details of the surrounding space, not seeing anything remarkable in it. The majority of the surveyed residents of the enclaves of poverty are passers-by for whom the neighborhood is a transit area, where they do not like to walk, and when they do, it is because they have to. A stroller is, in turn, someone who stays in a given space, visits it. This is a type of person who, while walking, sees what is around and pays attention to different, more detailed elements of the space. They walk around the neighborhood, because they like it. This is connected with greater sensory-motor sensitivity, expressed by describing the things that one is passing as well as commenting on what is pleasant and unpleasant in the space and how the area is changing. An inhabitant of the space, on the other hand, is embedded in a given space; not only is he/she familiar with the neighborhood and sensitive to the surroundings, but he/she also knows its history. In the experience of these participants, the identity of the place they inhabited, which went beyond their own backyard or tenement, was revealed in a particular way. Space for these people had far more meanings and evoked a number of associations with the past and the present.

The people’s way of being in the space identified above reveals a certain characteristic, namely that despite their declared identification with their local surroundings, the participants often manifested experiencing it superficially, often treating it – at least in some of its parts – as a space of transfer. Furthermore, the setting of houses and streets provided by the participants revealed some of the typical ways of movement, the way of “using” the neighborhood, elements considered important from the point of view of the assigned functions and everyday activities. Buildings, parks, urban fountains, and a country bridge are objects which not only allow spatial orientation, but give it meanings, activate the stories, experiences, and emotions saved in human history, which constitute central functions of the identity of place (cf. Qazimi, 2014). These elements of identity of the place are most strongly manifested in the way of being inhabitants of the space, who were also the smallest representation among the research participants. At the same time, regardless of the quality of the space, the vast majority of the participants felt at home in their neighborhood, are accustomed to that place, and have memories connected with it. They are familiar with it in terms of topography and their favorite services, as well as meeting and leisure spots are located there, they know its people, they have made friends, and are recognized. As a consequence of the research, only some places in the area which is subject to peculiar fragmentation can be internally experienced.

The need to belong to a place and be at home is a strong human motive, as shown particularly clearly by the research carried out in enclaves of poverty among the surveyed tenants of social housing, reliant – in their view – on administrative decisions. Analysis of the empirical material shows that socio-spatial exclusion and inclusion are not binary opposites and that it is not only excluded people who live in enclaves of poverty (cf. Crisp, 2010), but natives and strangers are also there; inclusion and exclusion are internal mechanisms to regulate social relations and spatial behavior (see: Nóżka, 2016; 2020). Living in an enclave of poverty, one can, therefore, both feel at home and be alienated. In terms of attachment and a sense of belonging, they are not homogeneous spaces. The research participants seldom identified with the whole neighborhood as their own place that they felt attached to, rather pointing to individual streets in the district, the tenement building they live in, and sometimes only the flat they and their family reside in as places of identification. These is a kind of “microworld”, i.e. places that are separate and distinct from the rest of the neighborhood, and – according to the participants – safe and well-maintained.

As the way the participants identified their neighborhood showed, when they feel at home there, they also have a sense of security and longing when they leave it. Identification with the place was usually inextricably linked to dependence on the place, aversion to leaving it owing to functional attachment and everyday rootedness, which was usually associated with a long stay and seldom leaving the neighborhood (cf. Hummon, 1992). A small number of the research participants could be regarded as “placeless” and alienated, with a negative attitude to the neighborhood they lived in and a desire to leave it (Nóżka, 2016).

Irrespective of the evident and visible negative characteristics of the place, the research participants identified with them, and they did so by using diverse tactics and strategies for presenting the place and “protective” reconstruction of its image. These were visible signs of identifying with a place and simultaneously identifying through a place (cf. Williams, Vaske, 2003). The research confirms the hypothesis that a space, including a socially-marked one, is an important element of building one’s own identification (e.g. Bańka, 2011; Lewicka, 2014). For these reasons, too, people who disassociated themselves from the enclave of poverty they were currently living in also usually pointed to their identifications with a place they had previously inhabited, even if it was another enclave of poverty, but one that they saw as a homely, safe place. On each occasion, a forced relocation – usually dictated by an administrative decision to allocate social housing in a different district of the city – was not conducive to identification with the new place of residence. This was also the case when the allocated housing was in a better technical condition.

Owing to the failure to take into account the important aspects of people’s relations with a place, processes of the revitalization of a space usually involve the revitalization of buildings rather than the social tissue that is a condition of care for the place. People are displaced from the places they know and relocated in social housing elsewhere, often in the belief that a better standard of home means a better life. As the results of research show (Willmott, Young, 1957; Warzywoda-Kruszyńska, Jankowski, 2013; Wódz, Szpoczek-Sało, 2016), displacing poor people from the spaces they know and transferring them to other places based on administrative decisions breaks ties with place and local communities. These, apart from actual lack of funds for revival, are the main reasons for the decay of a place. This is confirmed by the views of the research participants that the space is devastated by people without links to the neighborhood, with exclusion resulting from a lack of care for residents, which manifested in a lack of interest and underinvestment in the neighborhood they inhabit on the part of the district authorities. Failure to address the importance of socio-spatial identities generated in enclaves of poverty as well as succumbing to generalized and generalizing knowledge about them and the people who live there both mean that they are perceived not as a potential, but a burden for the neighborhood.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank all the people whose support contributed to the production of this article, namely the participants in my research, the members of the field research team composed of Przemysław Budziło, Adam Dąbrowski, Natalia Martini, Konrad Stępnik. I am also extending my gratitude to the anonymous reviewers for their insightful and constructive comments. I also thank my language consultant and translator, Ben Koschalka.

Cytowanie

Marcjanna Nóżka (2023), Identification with Place and Place Identity: The Perspective of the Mental Maps of the Inhabitants of Enclaves of Poverty, „Przegląd Socjologii Jakościowej”, t. XIX, nr 2, s. 6–27, (https://doi.org/10.18778/1733-8069.19.2.01)

Annan Kofi A. (2003), The challenge of slums: Global report on human settlements 2003, United Nations Human Settlements Programme, London–Sterling: Earthscan Publications Ltd.

Augé Marc (2011), Nie miejsca. Wprowadzenie do antropologii hipernowoczesności, translated by Roman Chymkowski, Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN.

Bańka Augustyn (2011), Przywiązanie do miejsca i jego znaczenie w cyklu życia człowieka, [in:] Augustyn Bańka (ed.), Symbole, przemiany oraz wizje przestrzeni życia, Poznań: Stowarzyszenie Psychologia i Architektura, pp. 7–14.

Baumeister Roy F., Jones Edward E. (1978), When self-presentation is constrained by the target’s knowledge: Consistency and compensation, “Journal of Personality and Social Psychology”, vol. 36(6), pp. 608–618, https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.36.6.608

Bell Paul A., Greene Thomas C., Fisher Jeffrey D., Baum Andrew (2004), Psychologia środowiskowa, translated by Maria Lewicka, Tytus Sosnowski, Jacek Suchecki, Agnieszka Skorupka, Aleksandra Jurkiewicz, Gdańsk: Gdańskie Wydawnictwo Psychologiczne.

Besten Olga den (2010), Local belonging and ‘geographies of emotions’: Immigrant children’s experience of their neighbourhoods in Paris and Berlin, “Childhood”, vol. 17(2), pp. 181–195, https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568210365649

Bird Julia, Montebruno Piero, Regan Tanner (2017), Life in a slum: Understanding living conditions in Nairobi’s slums across time and space, “Oxford Review of Economic Policy”, vol. 33(3), pp. 496–520, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/grx036

Bolt Gideon, Kempen Ronald van (2003), Escaping poverty neighbourhoods in the Netherlands, “Housing, Theory and Society”, vol. 20(4), pp. 209–222, https://doi.org/10.1080/14036090310018941

Crisp Beth R. (2010), Belonging, connectedness and social exclusion, “Journal of Social Inclusion”, vol. 1(2), pp. 123–132.

Czykwin Elżbieta (2008), Stygmat społeczny, Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN.

Descombes Vincent (1987), Proust, philosophie du roman, Paris: Éditions de Minuit.

Downs Roger M. (1970), Geographic space perception, „Progress in Geography”, vol. 2, pp. 65–108.

Downs Roger M., Stea David (1973), Image and Environment: Cognitive Mapping and Spatioal Behavior, Chicago: Aldine.

Dupont Véronique, Jordhus‐Lier David, Sutherland Catherine, Braathen Einar (eds.) (2016), The politics of slums in the Global South: Urban informality in Brazil, India, South Africa and Peru, Oxon: Routledge.

Falkowski Jan, Jasiulewicz Michał (eds.) (1994), Restrukturyzacja państwowych gospodarstw rolnych w świetle doświadczeń ogólnokrajowych, Koszalin: Wydawnictwo Uczelniane WSI.

Frankl Vincent E. (2009), Człowiek w poszukiwaniu sensu, translated by Aleksandra Wolnicka, Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Czarna Owca.

Fried Marc (2000), Continuities and discontinuities of place, “Journal of Environmental Psychology”, vol. 20, pp. 193–205, https://doi.org/10.1006/jevp.1999.0154

Frost Diane, Catney Gemma (2020), Belonging and the intergenerational transmission of place identity: Reflections on a British inner-city neighbourhood, “Urban Studies”, vol. 57(14), pp. 2833–2849.

Gans Herbert J. (1962), The urban villagers, New York: Macmillan.

Gould Peter, White Rodney (1986), Mental Maps, Boston: Allen & Unwin.

Hummon David M. (1992), Community attachment: Local sentiment and sense of place, [in:] Irwin Altman, Setha M. Low (eds.), Place attachment, New York: Plenum, pp. 253–277.

Kearns Ade, Parkes Alison (2005), Living in and leaving poor neighbourhood conditions in England, “Housing Studies”, vol. 18(6), pp. 827–851, https://doi.org/10.1080/0267303032000135456

Lach Kornelia (2001), O flichtowaniu [od niemieckiego fliehen: uciekać] i flichtlingach. Zmiana przestrzeni życiowej ludności pogranicza śląsko-morawskiego w latach 40. XX wieku, [in:] Piotr Kowalski (ed.), Przestrzenie, miejsca, wędrówki. Kategoria przestrzeni w badaniach kulturowych i literackich, Opole: Uniwersytet Opolski, pp. 125–131.

Lewicka Maria (2004), Ewaluatywna mapa Warszawy: Warszawa na tle innych miast, [in:] Janusz Grzelak, Tomasz Zarycki (eds.), Społeczna mapa Warszawy. Interdyscyplinarne studium metropolii warszawskiej, Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar, pp. 316–336.

Lewicka Maria (2012), Psychologia miejsca, Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar.

Lewis Oskar (1961), The children of Sanchez New York, New York: Random House.

Lewis Oskar (1966), The culture of poverty, “Scientific American”, vol. 215(4), pp. 19–25.

Lupton Ruth, Power Anne (2002), Social exclusion and neighbourhoods, [in:] John R. Hills, Julian Le Grand, David Piachaud (eds.), Understanding social exclusion, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 118–140.

Lynch Kevin (1960), The Image of the City, Cambridge: MIT Press.

Mesch Gustavo S., Manor Orit (1998), Social ties, environmental perception, and local attachment, “Environment and Behaviour”, vol. 30, pp. 504–519.

Nęcki Zbigniew (2004), Formowanie się postaw wobec otoczenia – od niewiedzy do nazwy, [in:] Ekologia społeczna – psychologiczne i środowiskowe uwarunkowania postaw, Kraków: Stowarzyszenie Ekopsychologia, pp. 111–115.

Nóżka Marcjanna (2016), Społeczne zamykanie (się) przestrzeni. O wykluczeniu, waloryzacji miejsca zamieszkania i jego mentalnej reprezentacji, Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar.

Nóżka Marcjanna (2020), Postawy wobec zamieszkiwanej przestrzeni i mobilność mieszkańców miejskich enklaw biedy w Polsce, “Etnografia Polska”, vol. LXIV(1–2), pp. 61–83.

Ooi Giok L., Hong Kai P. (2007), Urbanization and Slum Formation, “Journal of Urban Health”, vol. 84(1), pp. 27–34, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-007-9167-5

Proshansky Harold M., Fabian Abbe K., Kaminoff Robert (1983), Place identity: Physical world socialization of the self, “Journal of Environmental Psychology”, vol. 3, pp. 57–83.

Qazimi Shukran (2014), Sense of Place and Place Identity, “European Journal of Social Sciences Education and Research”, vol. 1(1), pp. 306–310, https://doi.org/10.26417/ejser.v1i1.p306-310

Relph Edward (1976), Place and placelessness, London: Pion.

Shaw Clifford, McKay Henry H. (1942), Juvenile delinquency and urban areas, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Small Mario L. (2015), De-Exoticizing Ghetto Poverty: On the Ethics of Representation in Urban Ethnography, “City & Community”, vol. 14(4), pp. 352–358, https://doi.org/10.1111/cico.12137

Stanny-Burak Monika (2005), Marginalizacja na obszarach popegeerowskich – społeczna konsekwencja transformacji, [in:] Lucyna Frąckiewicz (ed.), Wykluczenie społeczne, Katowice: Wydawnictwo Akademii Ekonomicznej im. K. Adameckiego, pp. 245–259.

Stedman Richard C. (2003), Is it really just a social construction? The contribution of the physical environment to sense of place, “Society and Natural Resources”, vol. 16(8), pp. 671–685.

Stegner Wallace (1992), The sense of place, New York: Random House.

Tomaszewska Danuta (2001), Przestrzenne aspekty sytuacji życiowej mieszkańców osiedli popegeerowskich – ujęcie typologiczne, [in:] Zofia Kawczyńska-Butrym (ed.), Mieszkańcy osiedli byłych Pegeerów o swojej sytuacji życiowej: raport z badań, Olsztyn: SQL, pp. 113–120.

Tuan Yi-Fu (1974), Topophilia: A study of environmental perception, attitudes, and values, Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall.

Walks Alan R., Bourne Larry S. (2006), Ghettos in Canada’s cities? Racial segregation, ethnic enclaves and poverty concentration in Canadian urban areas, “The Canadian Geographer”, vol. 50(3), pp. 273–297, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0064.2006.00142.x

Warzywoda-Kruszyńska Wielisława, Jankowski Bogdan (2013), Ciągłość i zmiana w łódzkich enklawach biedy, Łódź: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego.

Williams Daniel R., Vaske Jerry J. (2003), The measurement of place attachment: Validity and generalizability of a psychometric approach, “Forest Science”, vol. 49, pp. 830–840.

Willmott Peter, Young Michael (1957), Family and kinship in East London, London: Routledge Kegan Paul.

Wódz Kazimiera, Szpoczek-Sało Monika (2014), “Miejscy wieśniacy” w metropolii: przypadek świętochłowickiej dzielnicy Lipiny, “Przestrzeń Społeczna”, vol. 4(1), pp. 91–124.

Żmudzińska-Nowak Magdalena (2010), Miejsce – tożsamość i zmiana, Gliwice: Wydawnictwo Politechniki Śląskiej.