https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7370-3490

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7370-3490University of Lodz, Poland

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7370-3490

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7370-3490

University of Lodz, Poland

Abstract: The paper deals with the concept of empathy applied in the contemplative experiment to understand the suffering of the victims of the war in Ukraine. I discuss the concept of empathy in the phenomenological perspective and symbolic interactionists’ view. I needed this discussion to frame the conclusions from the contemplative experiment I did with my students. I used the contemplative methods of research. The students did self-observations and self-reports on their lived experiences while observing photos of the victims and refugees from Ukraine. Breathing exercises (pranayama) were practiced between different self-observations to clean the minds and release tensions. At the end of the experiment, the students were also asked about the empathy deficit in contemporary society, and provided comments on it. Finally, I concluded how empathy is evoked and embodied, and I answered the question about whether it is possible to be empathetic toward people in a totally different and traumatic situation. I end with the statement that empathy is a direct reaction to the condition of the suffering of other people. However, it is also socially-framed. I conclude that it could be socially-developed to cope with an empathy deficit.

Keywords:

war in Ukraine, empathy, symbolic interactionism, phenomenology, contemplative research

Abstrakt:

Artykuł dotyczy koncepcji empatii zastosowanej w eksperymencie kontemplacyjnym w celu zrozumienia cierpienia ofiar wojny w Ukrainie. Omówiono w nim koncepcję empatii w odniesieniu do perspektywy fenomenologicznej i symbolicznego interakcjonizmu. Dyskusja ta była autorowi potrzebna do osiągnięcia pewnej ramy interpretacyjnej wniosków z eksperymentu kontemplacyjnego, który przeprowadził ze studentami. W eksperymencie zastosowano kontemplacyjne metody badawcze. Studenci wykonywali autoobserwacje i autoraportowanie swoich przeżyć podczas oglądania zdjęć ofiar wojny i uchodźców z Ukrainy. Ćwiczenia oddechowe (pranajama) były praktykowane pomiędzy różnymi autoobserwacjami, aby oczyścić umysły i uwolnić napięcia. Na koniec eksperymentu studenci zostali również zapytani o deficyt empatii we współczesnym społeczeństwie i przedstawili swoje wnioski na ten temat. Na koniec podsumowano, w jaki sposób empatia jest wywoływana i ucieleśniana oraz odpowiedziano na pytanie, czy można być empatycznym wobec osób znajdujących się w zupełnie innej i w dodatku traumatycznej sytuacji. Artykuł kończy się stwierdzeniem, że empatia jest bezpośrednią reakcją na stan cierpienia innych ludzi. Jednak jest ona również ramowana społecznie. Autor stwierdza, że empatię można społecznie rozwijać, aby poradzić sobie z aktualnie występującym deficytem empatii.

Słowa kluczowe: wojna w Ukrainie, empatia, interakcjonizm symboliczny, fenomenologia, badania kontemplacyjne

A cultural philosophy can help predict the future as long as it creates it.

Florian Znaniecki, The Fall of Western Civilization

I am constantly writing contemplative notes; it is my way of researching the world through my mind (Konecki 2018; 2022). I assume that the academic mind could be empathetic enough to investigate the world from the first-person perspective (Bentz 1995; Giorgino 2015; Bentz and Giorgino 2016).

For what do we need theoretical, methodological, and abstract elaboration of empathy? Why do we need a justification for thinking about it? Maybe instead of these theoretical contemplations, justi-fications, and elaborations, we only need empathetic acting? All these endeavors to define everything and categorize the world that we make mean something; it shows how the academic mind works in the modern era. We do not just trust in empathy in the academic world, we do not trust that empathy exists, or do we think that others do not trust and believe it does not exist? Why do we think that empathizing could be helped by theoretical advice on others’ feelings and opinions? Maybe it should be less theory and more insight into lived experiences.

Maybe there are other explanations for this consideration of the phenomenon of empathy. There are many definitions; perhaps we need to have clear categories for identifying our activity and feelings. Do we need a scientific or theoretical explanation of what we feel? Am I empathetic, and what am I doing in an empathy-induced action? Or are there other motives behind my behaviors? The art of distrust develops, maybe we still follow Nietzsche’s idea of distrust of everything that is officially presented, and especially sociologists follow the debunking motive that supposedly represents the humanistic perspective (Berger 1963).

The concept of empathy was translated from the German language, where the term Einfühlung was used by psychologists, for the first time by Vischer (1994). It meant taking an imaginary bodily perspective (Ganczarek, Hünefeldt, and Olivetti Belardinelli 2018: 141) and, later, was referred to by Lipps (1903; 1906) to explain aesthetic experiences.

Among sociologists, Charles H. Cooley came up with the concept of sympathy. This concept is close to the meaning of empathy used in sociology, especially in the symbolic interactionist perspective (Ruiz-Junco 2017).

Empathy involves taking the role of others (Mead 1934) or, using the language of Alfred Schütz (1962), is connected with the reciprocity of perspectives; if it is difficult to achieve this reciprocity, it is difficult to activate empathy. Thus, the breakdown of the basis of the lifeworld (in this case, the reciprocity of perspectives) creates the conditions for the emergence of the Deathworld (Bentz et al. 2018). The lack of empathy here can be both a consequence and a prerequisite for the proliferation of the Deathworld (Bentz and Marlat 2021). Empathy allows us to keep truthful communication based on sharing the norms, and the speakers can examine their experiential background (Bentz and Marlatt 2021: 324–325). Empathy could emerge in such a situation. However, there could be the so-called no-empathy zone (Hochschild 2013), where empathy is absent, like in the territories of war or ethnic conflicts. The media and state propaganda could create such zones (as for the Russian publicity, such a zone was made in Ukraine during the war; 2022 – see Beehner 2022; Dickinson 2022; di Giovanni 2022; Russia vows no mercy… 2022).

Suppose I follow Peter Berger (1963) and apply the debunking motif, seeing through the facades of social structure (it is the art of mistrust) what empathy means. In that case, analysts, and theorists analyzing empathy, can see the term in a different light (Shuman 2011). The same principle of historical contextualization should be applied to understanding empathy as a term used by researchers or participants in everyday life in some current historical situation (Endacott and Brooks 2013). It is necessary to see the political location of the empathizing/non-empathizing persons, in what environment they operate, the cultural norms of their social environment, and their social site in the empathizing situation. In such a context, it will be easier for us now to understand the lack of empathy/sympathy for works of Russian artists among many Ukrainian intellectuals (Zabużko 2022) as well as the feeling of empathy for banned Russian artists by some American intellectuals (see Nossel 2022). Empathy is socially-located, even if I reconstruct its essential and universal qualities, which may seem trans-contextual and unconditional. And I, writing these words, have to deal with such attitudes of people living in partibus infidelium, where one empathizes with aggressors causing wars and committing genocide.

However, I’m not a fan of this sociology of suspicion, this “art of distrust,” which produces distrust on many levels of human existence, whereby not trusting others and institutions, we ultimately don’t even trust ourselves, and we are finally a self-deceiving subject caught up in alien but, after all, our discourses and network of institutions. These are situations where an evaluative/critical/misleading attitude precedes knowing another person’s voice and, ultimately, oneself. Could we find the golden mean between mistrust, the motive of unmasking, and the trust necessary to create community and social ties? We may try…

Empathy is connected with knowing. And what we can say about empathy is only knowledge of empathy that exists in the social typifications and a system of relevancies that refers to empathy. This is a phenomenological view. According to Schütz, we cannot be empathetic toward other animate organisms, because we do not share the inner view and knowledge of others. We do not have original access to any other consciousness and experience (Barber 2013: 316; see also Barber 2006). Especially with persons far from us and whom we do not know personally, we are not in a familiar situation; we can use mainly typifications. There could be one escape from this dilemma for Schütz by going to sociology, especially the sociology of knowledge that connects the I and the Other. The escape is in the intersubjective knowledge transferred by the language in typifications, cultural language formulas (proverbs and sayings), and, generally, in some systems of integrated experts’ knowledge (Schütz 1962). We cannot know what the other feels if we do not have the language testimony in the interaction or some confirmation of it that becomes the social index of the phenomena.

However, my knowledge about the war and the victims of war, while I do not participate in it, is also based on my bodily knowledge (we should turn to genetic phenomenology). I accumulated knowledge about the suffering, pain, fear of losing life, thrill, and sweating in the situation of great anxiety that may become conscious. My body knows that the fear is based on the similarities experienced in the past (Barber 2013: 320–321; see also Merleau-Ponty 2005; Rosan 2014). Based on the similarities of various species and humans, there is a phenomenon of synchronization of feelings among humans and between humans and animals. We could see the synchronization that usually occurs at the bodily level, e.g. when we yawn, laugh, cry, or feel sad (de Waal 2009). Wherever we find the roots of empathy or compassion (in the physiology of the animals or the spirit of humans and human history, evolution, or even in an individual’s past), there is proved that they are embodied (Stein 1989), and the acts of empathy are intentional (Jardine and Szanto 2017) and connected with feelings (Svenaeus 2018: 745). The perception of others goes together with the feeling which others could experience at the moment, and it is based on the primordial experience of a living body (Stein 1989: 63; Merleau-Ponty 2005)[1]. But the feeling means not only knowledge about feeling, but also experiencing somehow the feelings or emotions: “But the first important point is that the terms empathy and sympathy suggest that this understanding is not primarily gnostic, cognitive, intellectual, technical – but rather that it is, indeed, pathic: involving the emotions, the body, the poetic, the pathetic, and the pathically inspired” (Van Manen 2014: 268). And the reaction of empathy is almost immediate and automatic, and we do not have much control over it. We are directly transposed to the position of the subject of empathy, and it goes beyond only imagination (Stein 1989). So, empathy is a unique experience, and intention with the direction to the object of empathy is needed.

We enter the bodies of other people, and then their thoughts, emotions, and moves of bodies are like our own (de Waal 2009). The transfer of senses of “animate organisms” can be considered when we analyze how consciousness works: “Perhaps Husserl emphasized that the transfer of this sense takes place across a wide variety of beings, from humans to dogs to gorillas to fish to worms to accentuate how the smallest similarities evoke the transfer despite much larger differences than those that Schütz points out” (Barber 2013: 321). Here the sensual empathy can be activated (Svenaeus 2018). Empathy is the essential ability of a human being to access other minds, and it is an intentional experience that any material or social condition cannot determine (Jardine and Szanto 2017). “The feelings we have about other people may not always be the focus of conscious attention” (Owen 2007: 90). The intention can appear after the first reaction which can be unconscious.

I interpret empathy from the phenomenological point of view inspired by Barber (2013; see also 2017). Suppose we use the contemplative approach and be mindful of our bodies. In that case, we can feel the emotions of others vicariously in our imagination (Jardine and Szanto 2017); it is an appresentation from the self to others, even if the other is not present to us, but the mind imagines as he/she were present (Owen 2007: 79, 84); also, the feelings of other people connected with the war, such as fear, anxiety, rage, or sadness are appresented (see Konecki 2018: 234–235). Seemingly not being there, I never experience it directly. However, my senses are directed by the mind, the memory of the appearance of other bodies when sharing fear and the thoughts about them create the emotions, and the accumulated memory about the death and illness of others brings me closer to the actual situation. I suffer. Kineasthesia as a way of knowing works here, although in lieu. There is a mechanism as if I were there and were her/him. But it is not only the work of my imagination; it is a different mode of experiencing targeted at the Other, not only in my memory and past recollection of feelings concerning the situation. Knowledge of the Other is essential here, but it is not enough to feel empathy. You need to initiate the intention and motivation to go outside your consciousness. According to Husserl (1977a; 1980), the understanding of ourselves is strictly connected with an understanding of others:

Our “common psychosocial nature” is fundamental to empathy and co-empathy. The crossing of our visions of the world is a necessary condition for the emergence of empathy.

* * *

I want to introduce an interpretative understanding of empathy, mainly from the earliest grounds for symbolic interactionism. One can find the earliest concepts related to empathy in the work of Charles H. Cooley (1922).

I will do this presentation referring to the war in Ukraine, because I later searched for empathy in the context of war, especially after the mass invasion of Russia on Ukraine on 24.02.2022. The war caused a lot of damage in Ukraine, bringing suffering to civilians, genocide, and the destruction of many cities.

Though my mental and bodily experiments in imagining the war could be very sophisticated and advanced, and create the phantasy of actual war, in the back of my mind I know that I am more or less safe. I am far from the war. Therefore, it should also be critical concerning the context of social actors perceiving the phenomena and feeling empathy (Shuman 2011: 154).

The imagination is important here: “There is nothing more practical than social imagination; to lack, it is to lack everything” (Cooley 1922: 142). Sociologists have forgotten about it and do not treat “the mind with the imagination pictures” as the interesting subject of the study. However, it would be interesting to know why I think I can or cannot imagine other thoughts and feelings in some situations. What is the structure of my knowledge at hand that protects me against the thesis of the existence of empathy? One can only say that some people do not want to be empathetic or are protected by their socialization or other social influences (propaganda) from some empathy. What is the knowledge at hand (Schütz 1962); what are the emotions at hand (or the knowledge about possible feelings) that influence my imagination skills?

Sociologists underline the socio-psychological phenomenon of role-taking. So, the cognitive way of going into another body and environment is significant here (Mead 1934; Misheva 2009). Mead gives the cognitive base to empathy; however, it does not mean sharing feelings with others (Ruiz-Junco 2017: 417). The sympathy could appear as the consequence of taking the role of others (Ruiz-Junco 2017) And as the cognitive frame, it could be changed in society and shaped by political decisions and educational activity.

Empathy is a social construction (Ruiz-Junco 2017: 415). It is a social construction not only at the direct interactional level when it is launched by observation and/or imitation (de Waal 2009). The activity in the interaction and being active in observation is at stake here. Empathy starts in our communicational processes and embodied communication. However, it could also be constructed at the macro level by informational and propaganda policy as well as an educational system that directs us to whom one should feel empathy and to whom not.

Empathy/sympathy[2] concerns the mental operations: “[…] one has to bear in mind that it denotes the sharing of any mental state that can be communicated, and has not the special implication of pity or other ‘tender emotion’ that it very commonly carries in ordinary speech. This emotionally colorless usage is, however, perfectly legitimate, and is, I think, more common in classical English literature than any other” (Cooley 1922: 137).

Therefore, sympathy/empathy is mainly cognitive and, for Cooley, is socially-grounded. The human being could be morally evaluated by having the skills to feel sympathy for others (“sympathy is a measure of his personality”). Also, the skills help him/her to have power (“sympathy is a requisite to social power” – Cooley 1922: 141). So, empathy can also be used for purposes of domination and power. It allows one to diagnose the thoughts and emotions of another person and, therefore, in a sense, predict his/her future actions. It could be helpful in the work situation (instrumental empathy; see Hochschild 1983; Junco-Ruiz 2017: 429). These social and cognitive levels of empathy could be dissociated from some emotions: “I have already suggested that sympathy is not dependent upon any particular emotion, but may, for instance, be hostile as well as friendly…” (Cooley 1922: 159). One can enter the another person’s mind, but one can hate the person, and the emotion could be a stimulus to act (Cooley 1922: 160). Sympathy is not necessarily connected with the feeling of altruism, friendship, and love. It could be used differently. It is not compassion. As Cooley indicates: “Sympathy in the sense of compassion is a specific emotion or sentiment, and has nothing necessarily in common with sympathy in the sense of communion. It might be thought, perhaps, that compassion was one form of the sharing of feeling; but this appears not to be the case. The sharing of painful feeling may precede and cause compassion, but is not the same with it” (Cooley 1922: 137, Footnote 1). However, some sympathy can have a universal meaning when it connects with the love of God (Cooley 1922: 160) or with the whole nature, as is the case in Buddhist teachings (Hanh 1999). One sees a need for values, including the humanistic coefficient, not only from the sociological and methodological perspective, but also in the standard educational system of humanistic education based on values (Znaniecki 1988).

The society exists, because we are able to be empathetic and to understand the social order we should in order to feel empathy (at least cognitive empathy) and understand the Other. The effects of empathy we can see in the institutions that organize our society and are organized by the empathetic attitudes:

To come into touch with a friend, a leader, an antagonist, or a book, is an act of sympathy; but it is precisely in the totality of such acts that society consists… And, turning the matter around, we may look upon every act of sympathy as a particular expression of the history, institutions, and tendencies of the society in which it takes place (Cooley 1922: 167).

Susan Shott’s concepts (1979) follow the classical way of thinking about empathy, not only in symbolic interactionism. She also emphasizes imagination and the importance of taking the role of others, which could be the base for feeling other people’s emotions (Ruiz-Junco 2017: 418). Susan Shott’s conception also touches on sharing negative and positive emotions with others. The feelings of the empathizer are not identical to that of the recipients, but the empathizer tries to evoke similar emotions in himself/herself.

Natalia Ruiz-Junco (2017) proposes her own concept of empathy, also rooted in the symbolic interactionist perspective. However, at the beginning, she also follows Goffman’s concept of a frame (Goffman 1974). Individual-experience empathy is based on the cultural frames of experiencing emotions. The frame consists of three elements: the culturally-defined role of empathizers, the role of the recipients of empathy, and moral claims of empathy (some kind of beliefs or ideology; see Ruiz-Junco 2017: 421). The sociological vision of empathy indicates the societal and structural determinants (the frame) that define the possibility of the emergence of empathy.

The frame predetermines an empathizer position by the visual presentation of suffering children, who, as victims of the conflict, fall into the position of model empathy recipients… rights. In summary, empathy frames have a discursive structure that defines a moral claim for empathy based on shared values and on different positions for empathizers and recipients (Junco-Ruiz 2017: 421).

The media can be a very influential agent of empathy (Höijer 2004). We have this situation now that the war in Ukraine is going on. Media in the West create a mood of empathy for Ukrainian citizens experiencing genocide and a lot of suffering, including theft of belongings, torture, rape of women, killings of children, and the destruction of houses, hospitals, and schools (see Harding 2022).

Junco-Ruiz introduces to her sociological view of empathy the concept of empathy rules. She follows Hochschild’s (2016) idea of the ideological background of empathy. Empathy is socially-defined and indicates an empathy-deserving situation (e.g. in a war zone). Secondly, there is the identification of rightful empathizers and proper empathy recipients. Empathy-deserving situations are socially-defined, so her perspective is also sociological and oriented at recognizing and identifying the social conditions of empathy constructions.

We know that there is much information and media coverage of the wars. And one can experience this by observing what is going on in Ukraine: bombing, refugees fleeing to other countries, the fear and cry of civilians, etc. And the massive amount of information could be significant for getting to know about the life of the people in war, but also for evoking empathy. At the same time, it is too much of a burden on our perception and emotional responsiveness. However, one feels pressure that one should respond to: “Global compassion is considered to be morally correct in the striving for cosmopolitan democracy, and the international community condemns ‘crimes against humanity’” (Höijer 2017: 19). We know that media-mediated process of experiencing others is a common phenomenon of modern times; we are affected emotionally, and we know that we never meet the persons presented in media (Höijer 2004). Mass media and social media are the phenomena of modernity. However, the sympathy and empathy aroused by the narratives have been known in many cultures since ancient times. The Odyssey was told in antiquity, passed down from generation to generation, and aroused various emotions among the hearers.

There are also a lot of critics concerned with our interest in distanced suffering that we want to keep far away from our situation. There could be an experience of empathy deficit in contemporary society (Junco-Ruiz 2017: 414). Also frequent is that our charity is connected with this strategy of maintaining ontological security[3].

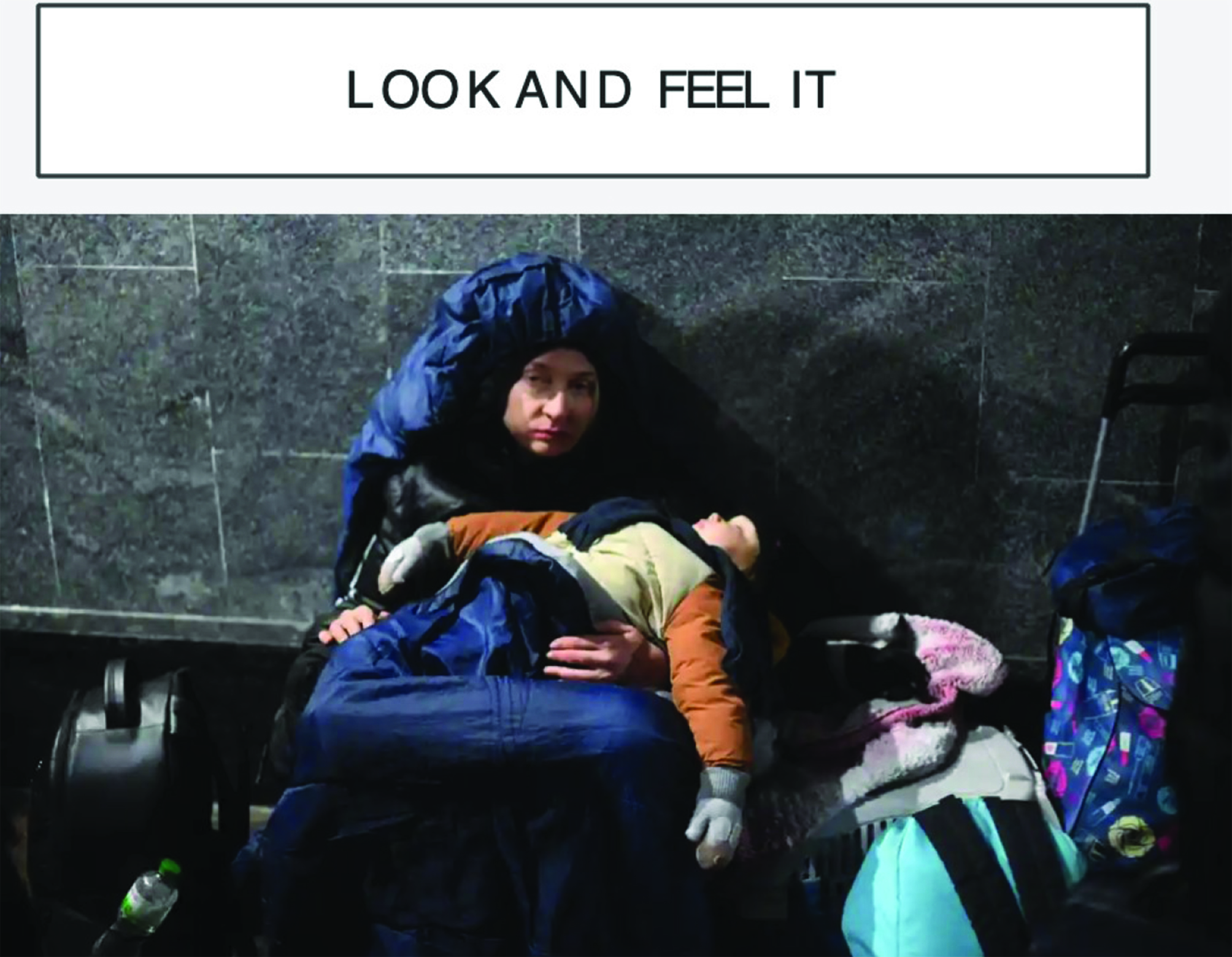

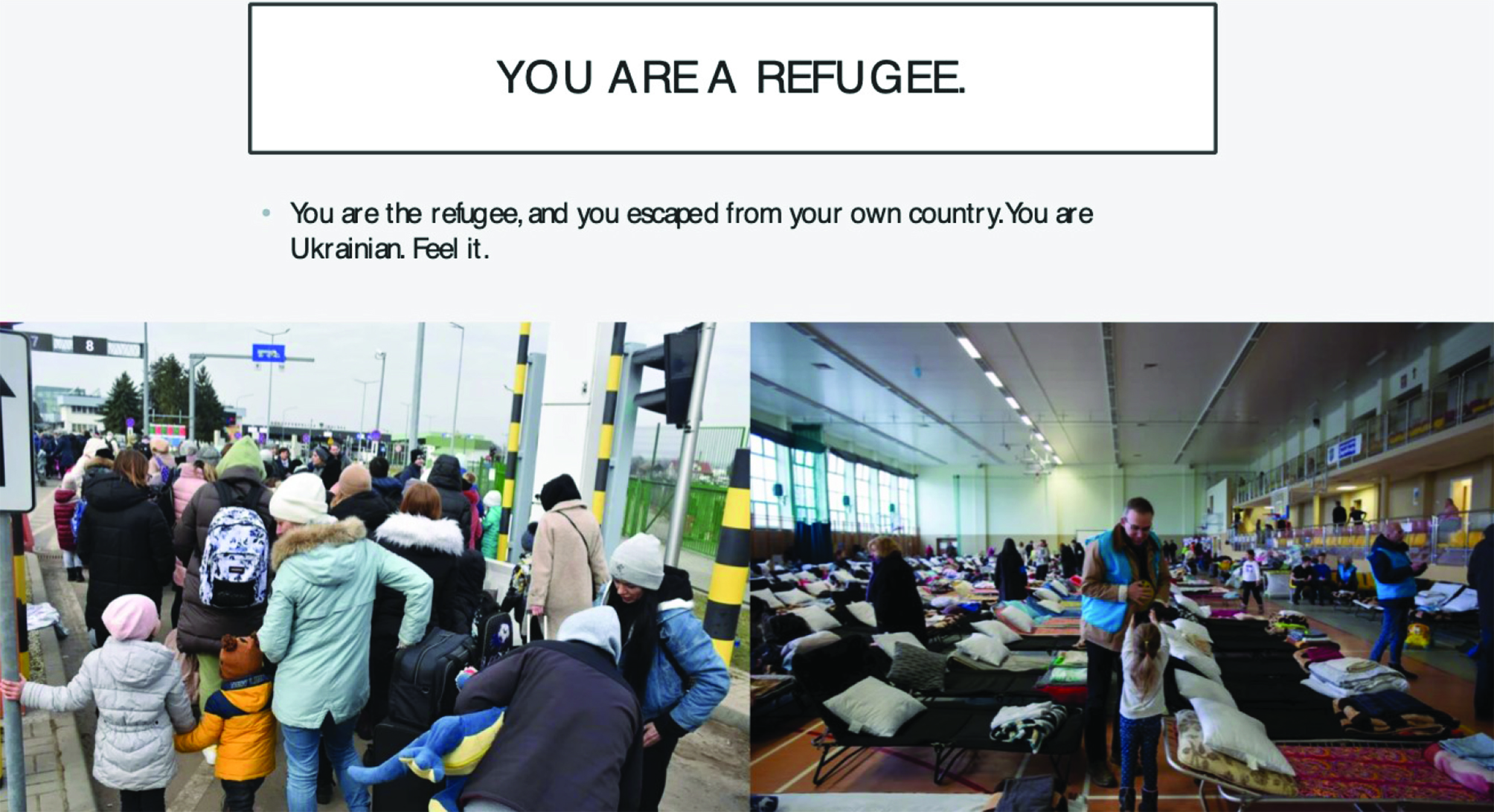

I wanted to check how the pictures of the war evoke empathy. The photos for an experiment were chosen to show the war and refugees’ circumstances and to have a punctum (Barthes 1981). It means that it should have something that can disarrange one perception of the world at the moment. It is an element in the photo that attracts one and makes thinking and feeling. It also causes some surprise and says something more than one sees. What emotions, thoughts, and body feelings are revealed at the moment of looking at pictures? What reflection appears when some emotions emerge? I thought about the reflection on the meaning of empathy and its presence in modern society, as well as about empathy deficit. I did a contemplative experiment with my students (for contemplative experiments, see Konecki 2018: 233–235) in order to answer these questions[4]. It is not an experiment on discourse and the context of text-appearing. It is an experiment on experiencing empathy:

Empathetic experiments are a part of the practice of contemplation. We put ourselves in the role of other, with the full awareness and observing our emotions and bodily feelings. We make an imaginative transfer of our body to the position of the other… This practice is very useful for social education… After making the experiment, we should write down what we experienced during it: our thoughts, visual images, bodily feelings and emotions (Konecki 2018: 234).

The experiments are understood here not scientifically but more as creating the situation to experience emotions and bodily feelings. It is more about uncovering the essential features of the phenomenon in order to understand it than about explaining the reasons for its emergence. Empathetic experiments are the contemplative methods to search for the meaning and the essence of lived experiences (Konecki 2018: 234–235). I borrow the lived experiences of the students to understand the meaning of empathy[5].

I think that contemplation and contemplative or phenomenological studies with students can teach us more about the concepts, theories, and social phenomena one experiences in the lifeworld (Bentz and Shapiro 1998; Bentz and Giorgino 2016; Konecki 2018; 2022; Bentz and Marlatt 2021). It is often not only about understanding, but also transforming ourselves (Rehorick and Bentz 2008). Moreover, as teachers and researchers, we can also learn from our students. The didactic process is interactive and we cannot assume that, as teachers, we have a better position for knowing (Rehorick and Taylor 1995).

I presented to the participants of the experiment, the students, the photos from the media, newspapers, and some websites which distribute the news from newspapers[6]. I asked the students what they felt in their bodies and minds and what emotions they experienced when they looked at the pictures. The pictures referred to the war in Ukraine between March and April 2022: pictures of destroyed cities, rescued civilians, children in the war, pregnant women fleeing hospital, a farewell of boyfriends and girlfriends, and refugees. I did the experiment in April 2022. Before the whole experiment, we had practiced for a few weeks hatha-yoga and meditation (I am an instructor of hatha yoga), and directly before the experiment, we practiced breathing exercises (pranayama) as well as a short meditation[7]. I instructed the students on the exercises, i.e. how to do them and what will happen afterward. Later, before and after seeing each picture, the students breathed deeply three times and tried to concentrate on breathing to clear the mind and the heart (the practice of pranayama), and be prepared for seeing and feeling the next visual image.

My inspiration for the experiment comes from my lived experiences of empathy with Ukrainian citizens and refugees. I was moved emotionally by the sufferings of the Ukrainians and their sad stories that I read and watched on TV or the Internet, but also from personal testimonies. I felt fear, anxiety, anger, and even hate for the aggressors at the beginning of the war, and empathy for Ukrainians. I wanted to create the base for identification with the victims of the war in the experiment by using some questions and instructions, and see how it works when the imagination is triggered by photos. Especially for me, it was important, because I had students from different cultures and countries, mostly those far away from the space of war. I wanted to see if their lived experiences share the same themes of empathy.

The students were from the course “Meditation for Managers” (2021/22, summer semester; University of Lodz), which was dedicated mainly to the Erasmus+ mobility program students from many countries, such as Spain, Turkey, Greece, Japan, Portugal, as well as Poland. The active participation in the experiment (writing self-reports on the feelings) was voluntary, 35 students took part in the class (22 women and 8 men), and, finally, I received 14 self-reports describing the emotions, thoughts and body feelings from the experiment. The students were aged 21–26. They gave their informed consent to participate in the investigation which was going on during the classes and to the researchers using their protocols in our research for explicating their lived experiences. The structure of the experiment was as follows:

I took for analysis pictures from Internet media; however, I did not discuss the media discourse on compassion or empathy (see Hoijer 2004; 2017). The photos were only the tool for the investigation of empathy. Visual images were important tools for attracting the public’s attention to social and human problems.

I practiced pranayama (Iyengar 1983) with the students, which meant deep breathing at the beginning of the experiment. It was work on the mind (cleaning the mind), releasing tensions, and building energy, and its aim was to prepare for the direct reception of the pictures. Below I quote the attitude of the students toward the practice of breathing:

Starting the class with breathing exercises made me start to relax and have a greater connection with myself. (woman)

I was breathing since many of these photographs have significantly impacted me due to the hardness they represent. (man)

As always, we start with breathing, which I appreciate to be able to mentalize that what we are going to do is calm down, think, meditate and concentrate on ourselves. (woman)

The breathing also helped to release the tension because of the difficulty of the situations presented in the pictures:

I would like to mention that I liked and it helped me a lot the pause we did after each question to take a breath because the questions were related to tough situations (due to the war). I noticed how my body got tense because I imagined myself in that situation and felt a lot of anxiety inside me. (woman)

Generally, in this paper, I present the students’ evocative first-person statements from self-reports. Sometimes, I think it is better not to interpret them but present them as they were written down in order to show the original expressions without any possible bias by the interpretations of the author of this paper.

After breathing exercises, I asked the students the question and gave an instruction: “What is empathy? Just write down, please, do not refer to the Internet.”

The most often expressed description and understanding of empathy was the following: it is connected with “putting yourself in the place of others” and understanding the emotions of others (see the quote below). This common-sense definition is similar to that proposed by symbolic interactionists. Therefore, one sees that often the theoretical concepts are constructed above the mundane understanding of terms that are used conventionally (the so-called “construct of the second degree”; see Schütz 1962: 6, 59):

Then, when the debate began on what empathy is, I began to reflect, and I agree with many of my colleagues on the definition of empathy: it consists of always putting yourself in the place of the other and trying to understand what their emotions and feelings are like so that we can take care of the way we act with these people. After this, and showing some images of the tragedy that Ukraine is experiencing, we were able to put the concept of empathy into practice and try to put ourselves in the shoes of the Ukrainian people and feel what they are feeling. (woman)

What is empathy for each one? For me, empathy is about thinking about others and putting yourself in their situation, communicating feelings and thoughts, understanding them, and being able to feel the other person’s feelings. (woman)

But understanding the emotion of others could go on together with understanding our own emotions. What is interesting here is that it is also connected with self-identifying with others and their feelings for the moment of empathizing:

For me, empathy is the feeling of understanding the other person and your own emotions. It is learning multiple perspectives, trying to identify with others and their feelings, problems, dilemmas. (woman)

Some of the students write about empathy as the synchronization of feelings with others. This understanding is close to the ethologists’ vision that emphasizes the synchronization of emotions among animals (de Waal 2009). However, the answer below underlines the real feelings, not only the presentation of self, as is the case in the Goffmanian vision (1959). What is interesting for the students (see below) is that it also relates to the past, not only to the present[8]. The present is the base to evoke the past to experience empathy with others here and now. For this reason, the historical persons could also be understood by using empathy. This kind of reflection appeared spontaneously in our research:

Synchronicity of feelings with others, and to have the same emotion at the bottom of heart, not on the surface. It is shared beyond time; we can have empathy towards historical people. (woman)

For what do we need empathy? We can feel it and do nothing. However, empathy was created for some purposes, to make something in social relation, to generate the ‘we’ relationship. If the pro-social activity follows the feelings of empathy, we can observe the whole social meaning of it. Some students emphasize that empathy is a human feeling which precedes helping others:

I think it is a very human feeling because through knowing the suffering of another person you can take actions to improve their situation, and you always tend to take care of others. (man)

It is the human emotion that is often associated with compassion, which is felt because of suffering; it is the feeling of sympathy for others that is also important for protecting the community life:

If I had to define empathy from a more personal point of view, I would say it is the natural human reaction to the pain that surrounds us and a way to protect ourselves and help us live in a community. (man)

Interestingly, one of the students said that empathy is a way of connecting with others. It is a very sociological interpretation; empathy creates the solidarity between humans, because it connects them. Another sociological meaning in the quotation below is an opinion that empathy is socialized and can be learned (see Heyes 2018). This opinion about empathy indicates that it is a social construct:

To me, empathy is a way of connecting. Empathy shows or tries to show that you know what someone is experiencing, even if you don’t know how they are feeling. Empathy says, ‘I want you to know that you are not alone, and I want to understand how you feel.’ Also, I think that empathy is not something you are born with; it is something you develop throughout life. (man)

From these quotations above, one can see that the students understand the term ‘empathy’. It is, according to them, the ability to “put yourself in the place of others”, but also understanding the emotions experienced by others and the synchronization of emotions. The students also wrote about compassion with the suffering ones, and connecting with other[9].

I presented to the students the following slides:

Slide 1. Bombing Kyiv

Slide 2. Rescuing civilians

Slide 3. Bombing Kharkiv

After seeing the slides, the students were asked:

Seeing the picture of the bombed city, students felt fear, anger, helplessness, sadness, and a lack of understanding (they often asked: ‘Why does it happen?’). It could be seen further that the fear and anger repeat many times in the descriptions of the war situation. The pictures affect the viewers emotionally; the felt emotions seem strong. The feeling of impotence is evident. The students also refer to their position and feel fear for their families. Therefore, the lived experience that emerges connects the imagining of other people’s situation and feelings with own ones. Embodied emotions are also perceived:

In a situation like that, I think that I will feel fear obviously, but also impotence and anger from the sensation that there’s nothing I can do about the imminent destruction of my home. (man)

I feel destroyed on the inside, lost, surprised. I’m trying to find something to cling to help me through this hard time: the grief, the sadness, the injustice. I care for my loved ones, and I am afraid. I wonder if my home is still a safe place. (woman)

I’m sad and terrified; I don’t want any of my family and friends to die. I’m confused because I don’t understand why this is happening. (woman)

Often, the reactions full of emotions coming at the same time were also embodied: “Helplessness, sadness, anguish, and injustice were some of the feelings I experienced. Seeing the harsh images makes me sad, and chills run through my whole body.” We see here that the body can be tuned to emotional reactions, and we can understand more from my relations to the world: “The pathically tuned body recognizes itself in its responsiveness to the things of our world and to the others who share our world or break into our world” (Van Manen 2014: 269).

After breathing deeply, the students observed the following pictures and wrote their self-reports. The instruction was short: “Write what you feel, please. Body, mind, and emotions.” According to their definition of empathy, the students tried to imagine being in the situation of refugees (see Junco-Ruiz 2017: 421).

Slide 4. Child refugees and mother

The students felt cognitive empathy for children suffering during the war. They could imagine being in the situation. There is the ethical stance that children should not experience such conditions. On the other hand, there are statements about not understanding the problem of children. In empathy, there is also some prediction of the future, that the war will leave a mark on them for life. Beyond this, children could feel confusion and helplessness:

You are a child in the war. How do you feel?

It is a situation that no child should go through. It must be very confusing for them; they don’t understand the magnitude of the problem, they don’t understand why they have to leave home, don’t understand why they see fire, don’t understand why mom and dad cry or they don’t understand why dad is not with them. It’s hard because they can’t do anything about it. They take it with them. And the most challenging part is knowing that this incident will leave a mark on their personal lives that they will carry with them for the rest of their lives. (man)

Slide 5. Child refugees

This is very difficult for me. I think a child’s mind is much more innocent than a teenager’s, but I still believe that children should not understand what is happening. To me, they must know something strange is happening, but they do not understand. They are leaving their stuffed animals, beds, movies, and playgrounds, but they don’t know why. If I were a Ukrainian child, I would feel confused with a strange feeling and a lot of helplessness to have to leave everything I know. I would feel a sense of being clueless and not understanding what my new situation would bring. Although I don’t think they know what is going on. (man)

The difficulty of understanding children’s situation is felt together with the defenselessness of the child, impotence, and the evaluation of the condition of children from the moral point of view (“heinous act”). The concerns about the children and the future of the child also appear:

I would feel a sense of bewilderment for not knowing what is happening since the innocence of children means that they do not fully understand why this type of situation occurs. In the same way, I would feel great sadness knowing that I am moving away from my family, my friends, and the place where I was born and that I will probably never have many of these things again. I also think it is tough to put yourself in the shoes of a child since each one can act differently, while in the case of adults, the answer we would give would be much more similar. In the same way, many of these children are defenseless, and there is no one to watch over their safety, and that seems to me to be one of the most heinous acts in this war. (man)

Terrified, very afraid, for the baby above all. And impotence and uselessness when you cannot save him from that situation and see that you are facing a situation that does not depend on you. We can see the desperation and abandonment on the mother’s face as she no longer knows what she can do to save the baby. (man)

The self-confidence disappears, and the weakness of the self and concerns about the children and the child’s future emerge. The self-identification with the role of the mother appears among women:

I feel weak without strength, I don’t believe in myself, and I don’t think I will make it. The war is more than me, I want to give peace to my baby, but there’s no peace in our place now. I want the best for him and give it to him, but if I can’t, even if this makes me sad, I’ll send him wherever he can be in peace. (woman)

There are often mechanisms of “as if” used, ‘what would happen if I were in such a situation.’ The sense of being lost as well as fear commonly appear by interpreting conditions presented in the pictures. Self-identification with the child emerges:

I’m trying to understand why every day looks different; I feel fear, an inexplicable sense of loss. I cling to loved ones (mom, dad). I’m looking for my bed and warmth. (woman)

There are also difficulties with understanding/imagining the situation of children during the war. Mainly it happens to children:

I think that, even if we make an effort to put ourselves in their place, it is very difficult to feel what they are experiencing. (man)

Children usually are emphasized more than adults. They belong to the so-called “ideal victims” (Hoijer 2017: 26), and it could be seen in media reporting from the wars. The “ideal victim” is a social construction that also depends on the current political and historical situations[10]. The interpretation in the frame of the “ideal victim” could also happen in our experiment.

The relations with parents are also noticed, and the suffering is connected here with the whole group of the family. It could be seen through the prism of own relations with parents, and it helps to imagine what the feeling would be in a real war situation:

I feel a lot of pain to think that some people kill others, that children have to live through hell to see their mother, father and other family die. (man)

The empathetic reactions were full of emotions of fear, but the fear was also embodied. The empathizer could imagine the feelings of the body such as discomfort, cold, fatigue, stress, and pain, and, once again, the relations with parents are visible:

I would be scared; I don’t know if I would understand what was happening if I could trust people because I couldn’t say who is good or bad. It would be tough for me to have to leave my house. I would be terrified. From the photos I have seen, I suppose I would also be freezing and hungry; it would hurt me to see my parents sad and scared. Sleeping in stations or public transport to be able to leave Ukraine, I would feel awful physically, my neck would hurt, my back, indeed, would be combined with mental fatigue from sleeping poorly, and the stress that each one endures. (woman)

The direct experience of seeing the situation of refugees is engaging empathy here (not from the pictures); the mother and the children who finally meet (it is the same student as above). The empathy works here in terms of seeing the picture and seeing the actual situation:

The other day, I went to Warsaw, and the station was full of Ukrainian people, with blankets, food offered by Poles, and children playing with what people gave them; it was a challenging situation to watch. On the return train, when I got off at the station, I saw two small children with flowers waiting for their mother, and the mother was crying because she was seeing her children. That image gave me a mixture of sensations. This shiver made my hair stand on end to see how hard the feeling must be for the mother and the children. There is also a lot of tenderness in seeing the image of the happy children hugging their mother with the flowers, and a feeling of sorrow in seeing how devastated Russia is leaving Ukraine and the damage they are doing to many families, older people, and young people. (woman)

After seeing the previous pictures and after a deep-breathing exercise, the instruction to students was as below:

You are a woman giving birth in the bombed hospital; how do you feel? What do you feel in your body and mind? What thoughts are coming to your mind?

Slide 6. The pregnant woman

Concerning the empathy for the pregnant woman under the bombing, the students feel desperation. The future horizon is taken into account, but it is difficult to predict what will happen, and this causes the feeling of sadness:

Desperation. It’s the first feeling that enters my head. It makes me reflect that life is hard, and some people suffer more than others because, in a moment as beautiful as having a child when you should be happier than ever and eager to see what the future holds for your child, you are thinking about whether the war will let Ukraine have a future or not. It’s sad. At that exact moment where you can’t move from the hospital, and you have to see how they destroy your country while you suffer the pain of the last weeks of pregnancy. (man)

As I mentioned before, sometimes the students express their problems and difficulties with self-identifying with other situations and emotions, especially when the empathy receiver is different in an important aspect of the case presented in the picture:

Then we saw the infamous image of a woman being evacuated from a hospital when she was pregnant. I don’t think I would be able to understand such a pain, so I prefer to respectfully not give an opinion. (man)

A difficulty in understanding the situation appears once again. However, it does not mean that the person is unable to feel empathy. Just the opposite; it is possible to see many proofs of the emotional manifestation (fear, sadness):

Definitely; the first word I thought of was “fear”. I try to put myself in that woman’s shoes, and, as I said before, I think it’s impossible to feel the same way. The thoughts that come to my mind are of great concern, the uncertainty of not knowing what will happen to your life and that of your baby, and above all, great sadness at seeing that you are bringing a child into the world in the worst of situations. (man)

The student quoted below evidently empathizes with the pregnant woman. She is like her and wants to give birth to her child desperately. She asks a question – ‘Why?’ As the author of this paper, I believe her; I feel it (my meta-empathy). Below we can read a very evocative statement:

Why should this happen to my unborn child? It is a life that was finally given to me, and I finally came this far after overcoming a painful period of hyperemesis gravidarum, but… I want to give birth to her. I want to show this child to my husband and parents. I don’t care what happens to me.

Sincerely clinging to God. (woman)

Strong emotions such as fear, pain, anxiety, and uncertainty are experienced in lieu. However, they look very authentic to me:

Unimaginable fear – for myself and the baby. Uncertainty, pain, desire to disappear for the moment. The desire for a safe place and people around. (woman)

I would feel a sense of fear and dread because the most important thing for me would be the safety of my child above my own, but the fact is that I know that I can do nothing to ensure the safety of my baby. It would make me possibly be with the worst feeling of anxiety that I could experience throughout my life. In addition, I would have to be alert at all times since, at any moment, I may have to run out of there in a state that could generate great consequences due to the inhumane conditions that many Ukrainian cities are going through that are no longer suitable for living, or for giving birth or for anything. (man)

The emotions observed during empathizing with the different situations of the war horrors are similar (mainly fear). The fear happens frequently, as well as the feeling of helplessness:

If I were a pregnant woman, I think what would matter most to me would be to be able to give birth safely. If I were in a hospital, I would feel much fear. There is a lot of pressure in my chest because you know that you will give birth to the most important thing in your life and the unconditional love you feel. That’s why I think I would feel a lot of desire to survive and, above all, a lot of fear. I would also feel helpless and want to scream because it would seem unfair that my child had to be born in those conditions. (man)

After pranayama, a breathing exercise, the instruction for the students was the following:

The students gave comprehensive reports concerning the issue of parting with a close person. The reason could be that it is at their age when they start close relationships with partners. They recognize the emotions from the nonverbal signs and gestures (see Cooley 1922); for this reason, they can feel empathy for this situation and people.

Slide 7. People that are close to each other say goodbye

The questions of despair often happen (‘Why does it happen?’) together with the intense emotions of sadness, fear of death, and anger, and even the willingness to fight together with the boyfriend:

I would feel great sadness and injustice. The questions that come to my mind are: why choose us? Why does my boyfriend have to leave me and defend our country? After all, it’s not his fault… Why do young people die because of Putin’s cruelty? Why does anyone have to die overnight because of the war? I would be sad, torn, and angry at the same time. I would have thought that we may never meet again. I wish he would stay with me, but I would understand why he has to stand up for it. (woman)

I feel so sad; I want to stay with him; why is he the one who must endure, and I am the one leaving? Why is he fighting, and I’m not? It’s not fear. We are the same age; the only difference is gender. I don’t want him to die, he is in danger, and I wouldn’t be able to live my life without him; I can’t lose him. I wish I could stay and fight, and he could leave and be in peace. He should come with me; this is unfair. I’m so sad my heart is broken. I think the worst because I cannot be optimistic about this situation. (woman)

In the self-observation quoted below, the student (woman) shows the fear and probable pride in him fighting for the country, but also a lot of pain connected with parting. Her empathizing is embodied; she feels the warmth and does not want to forget this feeling:

Want to meet again, I may not be able though… He will fight for our country; I should be proud of him. But it’s painful. I want to be with him. Tears come out. But I’m happy to be in love with such a brave person. I also have to live strong as he does. I want him to be safe. This can be the last moment; I don’t want to forget this warmth. (woman)

The bodily reactions come together with the fear and concerns about the future of the relations. The perception of the world combine here with the lived bodily feelings (see Van Manen 2003; Merleau-Ponty 2005):

I would feel despondent because, from what I have studied and know of similar situations in the past, I know that it is difficult to meet a person again after the war. Also, I would feel terrified if that person is a man I know who has to fight in the army. A terrible lump in my throat that wouldn’t let me breathe. Despite that, when I say goodbye, I would try to be positive so that the last memory of this person with me will be as pleasant as possible. I would try to feel her touch as much as possible; I would listen to her voice so I wouldn’t forget her, her smell, the color of her eyes… (man)

Many emotions appear, such as fear, anxiety, and restlessness, and it can even end in depression. Moreover, the feeling of empathy can be here extended to other people, not only the closest one:

Fear, feelings of loss. Confusion and a lack of clarity about the future. A desire to turn back or speed up time. Moving away from closeness, from warmth. Hope, love, faith in people. (woman)

I would feel a horrible sense of fear if I was part of the couple who had to go to war, knowing that I might not be able to see not only my partner but all the people who have been a part of my life or who I’m not even going to get out of there alive. On the other hand, if I were part of the couple who fled the country or was not on the front lines of the war, I would feel anxiety and restlessness that would probably bring me depression. Knowing that it is very probable that I will not return to see the most important person in my life with whom I would like to form a future and that I may not even be able to communicate with her. (man)

There is also a sense of the self that is split into two parts:

I am split in two, one half of my self, or at least best part of me, hopes to see each other again (woman)

Another student also expresses these feelings of splitting:

A lot of anger; I would want to cry because a part of you is leaving with him. It’s a moment of uncertainty because you don’t know if you’re going to see him again… nobody deserves that. Besides, you don’t even have the opportunity to be in contact to know how each of the parties is doing, it must be very hard, and you have to be very strong to face such a situation. (woman)

Difficulties of the emotions of parting with a close person are expressed by some of the students, even if students do not want to imagine the situation:

I don’t want to imagine how hard it must be to separate you from your partner knowing that there is a possibility of never seeing her again. Again, the feeling of sadness takes over me. (man)

The difference between the standard parting in a peaceful time and parting during the war is emphasized, with the feelings of sadness and uncertainty:

But here it is different because it is overnight, because of the feeling of knowing that you can meet again but that nothing is certain and you may never see each other again. It’s hard and sad. (man)

One of the students described, besides the embodied fear (sleeping difficulties), also the activity that she would take in the situation of parting with her boyfriend (checking the news and providing support):

If I was a girl saying goodbye to the boy? If I had to say goodbye to a person I love and kept thinking he was putting his life in danger, it would be cumbersome on my conscience. I would have a hard time sleeping; I would be worried all day and attentive to the news, I would try to be in contact with that person as much as possible, and I would try to support him at all times and encourage him. (woman)

Often mentioned is impotence, not only in this situation, but the helplessness is a significant part of the mode of empathizing with the victims:

I would feel very sad and afraid to think that I might never see him again, impotence for not being able to do anything to change the situation and not being able to be with him. (man)

Slide 8. Refugees

One student wants to escape her thinking and feeling about the suffering (see the quote below). She also shows her worries and fear about her family. She thinks about the historical moment and asks why it happened. Her empathizing is also embodied; she has even sensual feelings such as cold and pain, asking why it happened and why the world does not help us. This tone of the narrative is almost like crying:

What should I do from now on? I can’t help; I would like to escape all the suffering… I don’t know what to do from now on, but I have to move my legs to survive tomorrow. I’m worried about my family remaining in Ukraine. Are they safe? Or not alive anymore, no, I don’t think anymore. Cold, painful. I’m living in the middle of history. Is it the 21st century? Isn’t it a nightmare? Why the world doesn’t help us? (woman)

The emotion of anger is always present, although the countries receiving the refugees do their best:

I think you feel weird. You miss your home, you feel like a foreigner looking for a new home, but it will never be your home. The countries that host refugees do their best to make them feel comfortable, but even so, I would feel alone, sad, helpless, and angry because you have been kicked out of your home. (man)

Evocative statements are connected with the uncertainty about the life of the refugees:

Feeling that you have to flee your country to stay alive has to be one of the worst emotions. It’s hard to feel this. To think that you have to carry your whole life in a simple travel suitcase. Your house, clothes, memories, and whole life are left behind with the uncertainty of not knowing if you will ever get it back. (woman)

Along with the feeling of sadness, a sense of gratitude also appears because of receiving help from others:

I would feel a great sense of melancholy and sadness since I have left behind my family, my friends, my home, and the country where I grew up and where I have lived all the years of my life, but at the same time, gratitude and a feeling of appreciation due to the great reception that the refugees are receiving in the countries of Europe. Above all, I would feel obligated to return that favor because they are doing it without receiving anything, especially from the families that welcome many refugees. They feed them, give them a mattress to sleep on, a roof to live under… and all this without expecting anything in return. Also, thank all the volunteers and the mobilizations people for what they are doing to stop the war, since knowing that we are not alone gives me more strength to continue fighting. (man)

The gripping reaction is the sense of pride. When others help the refugee, self-esteem can go down, and protecting the sense of self is necessary. There is an interesting psychological problem of being grateful and at the same time keeping high self-esteem. The student empathizes with this feeling:

I feel like it is a new opportunity in life, but at the same time, I think I’m living a life that is not mine because this is not what I’m used to. I feel thankful to the people that are helping me, but at the same time, I don’t want them to help me because I don’t want them to think that I’m less than them. After all, I’m not. But seeing how they look at me with sad faces makes me feel this way. Am I a less worthy person? (woman)

Despite the emotional empathy when the students try to feel the emotions of the people presented in the pictures or generally the feelings of the refugees, they also recognize the emotions that refugees could handle. There is the cognitive aspect of recognizing the feelings of other people from the faces or from the details of the situation that is described (Cooley 1920), shown or presented at the moment:

I consider myself very empathetic, and I can feel their suffering the most by looking into their eyes. I see emptiness, a feeling that they cannot express; I see it in the Ukrainian families who have moved to Lodz. It’s a shame. I imagine it has to be a mixture of feelings such as sadness, anguish, helplessness, discomfort, anger, loneliness, or silence. (man)

The cognitive recognition of emotions among the suffering people can be blocked by own feelings of the potential empathizer. There appears to be anger against journalists taking pictures of the victims. Finally, however, the psychological mechanism of cognitive empathy – ‘what I would feel if I were there’ – helps to recognize the emotions of others:

– How would you feel if you were a citizen in Kyiv?

– A disappointment and feeling will arise about photographers and journalists who take pictures and don’t help. My heart will die. I can’t feel anything. I will kill my emotions to protect my heart. But if my family, friends, or loved ones get hurt or even die, sadness, anger, and resentment will all come at once. It was a happy place, but now… I might be disappointed to realize the gap between the hometown in my memory and reality. (woman)

Another question I asked at the end of the experiment was – “What is ‘empathy deficit’, and what are the reasons for it?” (for the concept of empathy deficit, see Junco-Ruiz 2017).

Some of the students observe the different approaches to different groups concerning empathy. Some indicate that in Poland, the approach to Ukrainian refugees is different to that concerning refugees coming from other parts of the world (e.g. from the Middle East). So, empathy is socially-contextualized and connected with some assumptions of the proper group and individuals that can be receivers of empathy, compassion, and help. Therefore, it can be noticed that empathy deficit is created by some assumptions and prejudices. Moreover, we also had “better victims” and others, those not deserving empathy (Höijer 2017: 26). The “better victims” deserve more empathy and attention than “less worthy victims”:

I think the answer to this question [about empathy deficit – K.K.] can be varied concerning the issue or area we are talking about, but focusing on the issue of the war, I think there is a lot of lack of empathy. The reason for this is that right now, we see that countries like Poland are doing everything they can to help the Ukrainians who have been affected by the war by providing enough resources to make them feel at home and at ease. I have noticed that they have not done the same with other countries like Israel or Syria, which have been at war for much longer. This is an example of the lack of empathy because what is happening in Israel or Syria is not as close to us as in Ukraine. Therefore, we do not pay any attention to what is happening there, and we do not put ourselves in their shoes to try to understand their situation and help them in the best way we can. (woman)

The deficit of empathy is also caused by technology that is used in everyday life, which creates a lack of direct contact and face-to-face interactions with others:

I think that the deficit of empathy is experienced today, and I believe that social networks are the critical factor. It is something positive that the world is much more globalized. The appearance of new technologies to unite people from different parts of the world has made many things more accessible. Still, at the same time, feelings cannot be shown 100% through a screen, and the world has gotten out of the habit of dealing with people face-to-face and not over the phone. I am just as addicted as all teenagers to social networks, but at the same time, I am fully aware that the value of living in the world outside the screen is much greater, and I think that the goal of all should be to find the balance. (woman)

But there is a different opinion, namely one that technology helps in empathizing; it gives information about other people and makes it easier to empathize:

[…] but I think that people’s empathy is increasing because thanks to new technologies and social networks, we can be continuously updated on what is happening in each part of the world. This helps us be more aware of what is happening; therefore, it is easier to put empathy into practice with other people. (woman)

Some students had a general reflection on the reasons for empathy and the empathy walls (Hochschild 2016; Konecki 2021: 125–126). Something in us can protect us against feelings of empathy; Edith Stein calls it “negative empathy” (Stein 1989: 15). It can be connected with some background experiences that generate a blockage of empathy. Except for technology, the style of life in contemporary civilization kills compassion and empathy. The consumerism, greediness, making a career, and money are all more important than perceiving the suffering of other human beings:

I do believe that there is a lack of empathy in contemporary society, both on the part of adults and young people. On the part of young people – because it seems that they are more aware of their mobile phones, of the notifications that reach them, the applications they use, the trends that they are wearing at all times or the clothes they want to buy, and none of these things have the importance compared to what is happening in Ukraine or in many other countries that are also at war, like Syria. It seems that people are putting aside the suffering of many others, and we selfishly focus on ourselves and our well-being, but then when we need help, we are the first ones who, if they do not give it to us, feel betrayed or experience a sense of no one caring. On the other hand, concerning adults, the lack of empathy they have is not so strong, but many of them only think about moving up professionally to earn more money to use later for themselves. Ultimately, the more money people have, the more they want. They always use it for their benefit, which is what many adults wish for in life, a high salary and good quality of life, so they don’t have worries about their future, but then the concerns of the rest do not seem to matter to them. Likewise, concerning the war in Ukraine, we have seen a significant citizens’ mobilization to end this horror. Still, as the days go by, people return to their everyday lives and look the other way when talking about this issue. (man)

Some of the students, while seeing the concentration on the self and selfishness, also mention the educational problem connected with the issue of empathy. Empathy is not taught at schools:

I can feel the empathy deficit in the contemporary world. I think that nowadays almost everybody thinks about themselves and not about others. In the theme of the Ukrainian war and the refugees, I believe Poland is very empathic because people are helping so much. But in my country (Spain), this is not like that. Some people are offended if others give more opportunities to refugees than own citizens because they aren’t empathic; they only think they are losing a chance to work; for example, they are not thinking about those people’s problems and situations. This is an education-related problem. Also, I see this inside schools; kids should be taught in an empathic environment to understand how differently others think, feel, and act. (woman)

Some students indicated that the lack of empathy could be connected with the self-defense psychological mechanism. Too much bad news around could be challenging to bear:

At last, in conclusion, we have talked about the lack of empathy today. I would say that sometimes I understand it as a self-defense mechanism because we are constantly being informed about bad news worldwide, and it would be impossible not to be depressed if we were always being empathic with those suffering. But still, I think it is time to be strong and help as much as possible and not be afraid of others’ pain. (man)

But if we speak in general, I think there is a huge lack of empathy in the world. I don’t know why; maybe our mind blocks anything that hurts us, and by doing this, we don’t feel what the other person is feeling, which makes us less empathetic. (man)

And so, this self-defense psychological mechanism is used, but another reason for empathy deficit could be seen in media (Höijer 2004; 2017). If one hears too much bad news from the media, one can become indifferent to the real problems of others:

Speaking more specifically about what the culprit is, in my opinion it is the social networks. I also think that part of the blame lies with the media, for the news has put us in anguish. After bad news do this, we get tired of so many bad things we take that we finally act in a way that is not ours. This is how, in my opinion, we also lose that ability to react empathetically to the pain of others. (man)

One student’s meaningful reaction (see below) is that she is lucky not to have experienced such a situation. She indicated how important existential security is in life. She also has a future perspective, but is connected with the hope that the war will finish soon:

I have also finished the class reflecting on how lucky I am and how lucky that we have a home to live in and family and friends with whom to share life. After seeing these harsh images of Ukrainians, I feel luckier than ever. I hope this tragedy ends soon and all these people get their homes back as soon as possible. (woman)

After the experiment, some of the students are saying that they should be more reflective about themselves concerning empathy. Looking deeply into the self could help overcome the deficit of empathy. And it happened after the experiment. I think that the statement below touches on the didactic goal that we assumed at the beginning of the empathy experiment:

I think I am an empathetic person, but it is also true that I often assumed or criticized things that if I were empathizing, I wouldn’t criticize. It is effortless not to self-evaluate and say that you are empathetic to feel comfortable with yourself. I believe that I am empathetic frequently but that many other times I lack empathy. (man)

I present some theoretical conclusions now, taking into consideration the results of the research. According to Hochschild (2016: 5), empathy wall is “an obstacle to the deep understanding of another person, one that can make us feel indifferent or even hostile to those who hold different beliefs or whose childhood is rooted in different circumstances.” The author indicates that the socialization process as the base for empathy is a profoundly sociological perspective (Hochschild 2016). Politicians can also create the empathy wall which is socially-constructed (Konecki 2021: 126–127; see also Stein 1989: 15). Therefore, the attitudes built around the walls can be changed by practicing empathy.

The experiment presented in the paper shows that it is possible to gain some insight into the situation of sufferers. The first step is cognitive empathy, when we can see a particular case from the point of view of another person, the receiver of empathy. Of course, this is an experiment, and you cannot be entirely realistic in this situation (if we are distant from this situation). Still, we try to use various images to activate the memory, enter this situation in our imagination, and see how it might look. This is cognitive empathy. We use it in our “practice of consciousness to project itself beyond itself” (Barber 2013: 317). We have the inherent tendency to transgress ourselves and go beyond our minds and self.

Many self-reports show that you can experience certain emotions, even vicariously. The second layer of empathy is the basis for compassion. The cognitive layer (similar to “perception-like empathy”; see Jardine and Szanto 2017) is a prerequisite for the occurrence of the emotional empathy layer, when the imagination begins. It refers to many situations presented in the pictures. Of course, a further step may be the emergence of compassion and the helping phase, which is also a continuation of empathy. The activity can be a kind of the summary of learning about the other person’s situation, and feeling their emotions. The students generally show significant level of empathy in the cognitive and emotional layers. This is indicated by the language etiquettes related to naming emotions and describing situations from one’s own perspective as well as the Others’ points of view (fear, anxiety, agitation, regret, sadness, loss, depression, hope, gratitude, etc.)

The second important element of empathy is the embodiment of emotions. The students often feel the emotions in their bodies concerning many situations presented in the pictures. The reaction of empathy in imagining extreme conditions seems to be common, if not universal. It could be called a high level of empathy (Svenaeus 2018: 744). Therefore, the embodiment also has the second property, namely the embodiment of emphasizing feelings. The breathing exercises and the earlier hatha-yoga practice in the project helped the students notice the bodily reactions and also see how the mind works, how the emotions appear, and where they are located. The experiment was a didactic tool for teaching about recognizing the emotions in the body and the role of the body in empathizing. The breathing exercises also show how the physical exercise helps to reduce stress while empathizing with the problematic situations and terror that the victims of war experience.

The third element that can be distinguished in self-reports is the moment of doubting the possibility of fully empathizing with the situation of people suffering during the war and of refugees. But that is not a strong theme in the auto-reports. Sometimes students feel confused about empathizing with war victims and war refugees. They do not know what to do in the face of the horrors of war. They also wonder how others will react to such situations. Although empathy is noticeable in all the students participating in this project, it was often said that it is challenging to imagine and impersonate characters whom you should empathize with. This may be understandable as the war situation is an extreme one. But still, you can imagine what can happen to you, being isolated from your loved ones, being under fire from artillery, or hearing and seeing bombs falling nearby. One can make such an experiment and imagine it; of course, one cannot fully imagine it without experiencing the situation directly. But usually, my reaction of empathy is immediate (Jardine and Szanto 2017). Nevertheless, the answer I could not understand would have been answered in terms of running away. From the phenomenological point of view, I can say that the students have a problem in living in two worlds, even imaginatively in one of them (war); there is some discrepancy between their lifeworld and the lifeworld of the Other that is becoming Deathworld (Bentz and Marlatt 2021; Konecki 2022: Chapter 3). These two worlds are challenging to understand at the same time. The taken-for-granted assumptions about the “normal” lifeworld become questioned (Schütz 1962; Schütz and Luckman 1973; Shuman 2011). We should be careful about romanticizing empathy in perceiving victims in extreme situations which we can feel the same as the receiver of empathy (Berger and Harris 2008; Shuman 2011). But what is optimistic about it is the reflection that appears. The short moment of alienation from the so-called “normal” world starts the process of thinking about the fragility of taken-for-granted assumptions about the “normal” lifeworld.

The empathy related to imagining the situation of war victims and refugees is connected with the assumption that there are things that are unimaginable and impossible to understand. It is justified when encountering death, imagining death, and coming across an imminent death threat. But this assumption removes us from the compassionate empathy that can arise if we do not fully embrace it. When we activate our imagination, we do a thought experiment; we will force ourselves emotionally to live a surrogate experience in a particular situation. We do some self-violence in this situation, but emotional feelings are necessary to fully activate empathy and compassion. Merely imagining and cognitively structuring a specific situation is not enough; it is a prelude to genuine empathy in general and compassion for the suffering in particular. We should remember “the basic and widespread tendency of mental life to identify and assimilate” others in their conditions of life (Barber 2013: 317), and we should remember that refusing the possibility of empathy is connected with not seeing “the level beneath thought at which empathy occurs” (Barber 2013: 317).

Suppose we base our approach to morality – empathy on the sociological vision that everything comes from the society that wants to be integrated, and that morality and religion have this function (Durkheim 2008). In that case, we are in the cognitive trap, which cannot aid in explaining why people help each other and empathize with others without concern for social norms that divide people on who is worth empathizing with. The ontological anxiety and safety problem is significant here (Giddens 1990), but when it is interpreted from a contemplative perspective, different conclusions arise (Bentz and Giorgino 2016). Sometimes, in order to be empathetic, we need to show our courage against the whole of society and find ourselves in danger of being killed. It happened during the time of the Holocaust when some people from the occupied countries helped Jewish to survive. It was dangerous for life, but it did happen. And we had, on the other hand, the silence of society, indifference to the murders of Jews. It was socially acceptable to be silent when the Holocaust was going on around during the Second World War (Bauman 1989).