GASTROPROBLEMS AND TIME GAMES THE PRECARITY OF POLISH CATERING WORKERS

Hanna Szalecka *

https://orcid.org/0009-0008-7444-6095

https://orcid.org/0009-0008-7444-6095

Abstract. This paper aims to analyse the work in catering through the lens of temporal categories and the mechanisms of precarity governing the catering sector. The article is based on a study conducted in 2024, in which both former and current catering staff participated. The data discussed in the text illustrate the central role of the passage of time in the organisation of work in catering and its consequences for the private lives and futures of workers.

Keywords: catering, precarity, time, labour market, social consequences of work, chronosociology.

GASTROPROBLEMY I IGRZYSKA CZASU. PREKARYJNOŚĆ POLSKICH PRACOWNIKÓW GASTRONOMII

Abstrakt. Celem artykułu jest analiza pracy w gastronomii przez pryzmat kategorii temporalnych i przyjrzenie się mechanizmom prekaryjności rządzącym sektorem gastronomicznym. Artykuł powstał na podstawie badania przeprowadzonego w 2024 roku, w którym udział wzięły byłe i obecnie zatrudnione w gastronomii osoby. Omawiane w tekście dane obrazują centralną rolę upływu czasu w organizacji pracy w gastronomii i jej konsekwencje dla życia prywatnego i przyszłości osób pracujących.

Słowa kluczowe: gastronomia, prekaryjność, czas, brak kontroli.

1. Introduction

Catering is one of the fastest-growing sectors of the Polish economy. This is illustrated by data from recent years showing an increase in the number of catering establishments from 64,449 (2020) to 83,937 (2022) (GUS 2023: 32). This is all the more surprising given that this is a pandemic period when many as 97.4% of entrepreneurs operating in the ‘accommodation and catering’ sector report experiencing ‘severe or threatening business stability’ difficulties (GUS 2022: 3). However, paradoxically, the catering industry has not experienced a regression but has grown. In the context of catering establishments, the lack of data on the people employed in this sector is noticeable. Estimates range from 0.5 million (Lipiec 2022) to 1 million (Szymkowiak 2021), but these are unofficial figures. No report is currently available on the employment structure of the catering industry, which is mainly due to the great difficulty in obtaining data due to high mobility within the sector and the prevalent absence of contracts.

However, hospitality is not only a macro-structurally relevant industry, but also one that plays a significant role in the personal experience of those who use it. Catering establishments are important places to meet, establish relationships and provide resources to support human well-being. Besides, it is an integral part of the city and tourism and a space that positively influences other people’s lives.

The processes and events in the hospitality business make it a sociologically interesting area of research. In addition, there is a thematic gap in the field, as the research tradition related thereto is not long, and the scarce scientific publications are works from recent years (Adamkiewicz, Zielińska 2024; Lipiec 2022; Zielińska 2014, 2015). Notably, there is no discussion of the key actors – the people working in the catering industry – who make it work. This deepens the level of ignorance about the situation of the people employed in catering. Taking into account the popularity of employment in the hospitality industry among young people, the need to study the catering business as a place that often establishes initial, yet not always appropriate, work patterns is increasing (Kiersztyn 2015; Wysocka 2013; Winogrodzka, Mleczko 2019: 87–91).

In this article, I aim to address the following questions: How do mechanisms of precarity exist in the labour market utilised to organise work in the hospitality industry, and what is the impact of these mechanisms on employees? This article is the result of my two-stage, quantitative and qualitative, study in which I analysed how the nature of employment in catering and its specific mechanisms related to work organisation affect the people working in this industry. This text aims to fill a gap in research on hospitality, presenting it as a sector characterised by specific working conditions and analysing it from the perspective of time. Temporal categories do not appear when considering the catering industry, but it is in them that I will look for the mechanisms that determine the processes that take place in catering and the lives of the people who work in it. Looking from the perspective of time, I also intend to demonstrate that the precarity of the labour market precarizes the catering industry not only as the area of work but also affects the entire life of the individual (Palęcka, Płucienniczak 2017).

2. Catering industry, precarity and precariat: A literature review

The interest in the catering sector in sociology is relatively new. The texts that have been published so far are activist in tone; they draw attention to the problems encountered in catering, such as bullying and employer-employee relations (Pawłowska 2017), the deplorable working conditions that threaten the safety and well-being of workers (Kaleta 2016) and the prevalence of non-employee form of employment as a violent means of keeping people ‘in a state of expired youth’ (Kaleta 2016). The available articles are also often journalistic attempts to map the problems present in the catering industry (Greon 2024). However, catering is not only depicted negatively, and the difficulties encountered at work are sometimes minimised (Gładczak 2019). To date, most attention has been paid to waitpeople, particularly on the wave of the 2014 tape scandal, in terms of the profession’s rules and the changes taking place (Bednarczykówna 2018) and by portraying waitpeople as confidants of secrets and close observers of the changes society was going through (Pobiedzińska 2020).

Nevertheless, precarity remains the key category in describing the hospitality industry, arising as a consequence of labour market precarization (Lorey 2015). The choice of ‘precarity’ over ‘precariousness’ is significant. Following Butler’s (2009) framework, precariousness, the ‘experience of fragility and suffering’ (Mrozowicki et al. 2020: 24), is an inherent and unavoidable aspect of human life due to bodily limitations and associated risks. Precarity, on the other hand, refers to a condition in which specific groups are deprived of access to ‘social and economic support networks and become, to varying degrees, vulnerable to harm, violence, and death’ (Butler 2009: 25). Thus, precarity is a more precise term in the context of precarization, emphasising that individuals’ experience of instability does not stem from the mere fact of being human – fragile and mortal – but rather from systemic injustices of the labour market, which actively inflict economic harm, subsequently affecting broader social and welfare structures.

Precarity, however, remains the key category for describing the catering industry. Guy Standing, as one of the key creators of the modern precariat concept (Standing 2014), shows how neoliberal processes affect the individual – forcing them to adapt to the unequal rules of the free market, making them part of an inferior category. Standing characterises precariat through the lens of the lack of seven types of security: (1) labour market security, (2) employment security, (3) workplace security, (4) job security, (5) skill reproduction security, (6) income security, (7) representation security (Standing 2014: 49), which illustrate the multidimensionality of challenges this group encounters. The precariat is a product of flexible forms of employment proliferating due to the emergence of new forms of work organisation (Sennet 2006, 2010). The ever-increasing number of temporary, open-ended or seasonal job offers, with the enticing promise of flexible and tailored working hours, is a trap of flexibility behind which, in the guise of promises of freedom and liberty lined with ideas of individualism, lurks fear for one’s fate, uncertainty and anxiety (Palęcka, Płucienniczak 2017). The leitmotif of flexibility is ‘nothing for long’ (Sennet 2006: 22), which ‘puts an end to long-term actions, cuts the bonds of trust and commitment, separates the will from the actions of the person’ (Sennet 2006: 35). ‘Nothing for long’ implies temporariness, loosens social networks and makes it difficult to establish relationships, and does not allow for routine. The trap of flexibility lies in its short-term appeal. It may indeed help in the day-to-day lives of male and female workers (Zielińska 2015), strengthening their sense of agency in deciding about their own lives, but it is an illusion designed to distract from other consequences of flexibility, such as the lack of social benefits, social security or a stable future in general. These consequences, as opposed to the short-term advantages of flexibility, are long-term and substantially impact an individual’s sense of security – flexible forms of work are the reality of forces that ‘bend people’s necks’ (Sennet 2006: 55).

In the context of the catering industry, Justyna Zielińska (2014, 2015) paid much attention to precarity and especially precarious flexibility. The researcher sees flexibility as an opportunity for employers and a cost for employees. However, the latter, particularly students, see flexible work schedules as an opportunity to fit in with their current life situation (Zielińska 2015: 22). The topics of precarity and the catering industry were also taken up by Stanisław Lipiec (2022), examining the processes taking place from sociological and legal perspectives. The catering industry and its accompanying precarity in microstructural terms are presented based on a comparative analysis of employees working in catering establishments in Vienna and Warsaw (Adamkiewicz, Zielińska 2024). The interest in precarity and flexible forms of employment, correlating with the catering industry, can also be seen in research on food delivery workers (Polkowska 2019, 2020, 2023; Mika 2023), which received attention in the theatre production: ‘Delivery Heroes. Bohaterowie na wynos’ (Błażewicz, Cichoń 2024). As platform workers, couriers represent a distinct category of precarity that I do not include within the definition of those working in the hospitality industry.

Flexibility is an intrinsic theme of precarity, so incorporating it into the research on the catering industry is crucial. Far less attention, in the context of research on precariat, has been paid to the relationship between time and precarity, and this relationship seems essential for the catering sector.

3. Time and precarity

Time is the basis of the social order, the goal and condition necessary for change and stability (Adam 1994). Although the human capacity to manage time is increasing, it remains external to the individual as an organising mechanism of social life (Durkheim 2010: 264–396; Hall 1999; Kramarczyk 2018). It, therefore, accounts for the rhythmicity (Adam 1994) of people’s actions. Controlling time and having influence over it is one of the most valuable human resources and privileges (Lebhar 1958; Tarkowska 1992). However, society’s perception of time varies. In the case of the precariat, the scope for subjectivity and legitimacy in deciding one’s own time is limited. The management of people through time is, along with flexibility, one of the most calculated because it is an invisible and yet powerfully influential form of neoliberalism. Lack of control over one’s time forces one to live in the present – forced because living in the short-term becomes a necessity rather than an individual choice: ‘Presentism is a way of adapting to situations of long-term crisis, ambiguity and uncertainty of the future’ (Tarkowska 1992: 130).

Standing devoted a separate chapter to time, seeing it as a resource organised by industrialisation (Standing 2014: 235). The author presents precarious men and women as subject to time pressure, i.e., working and therefore spending time on work, which translates neither into their economic security nor a stable career path (Standing 2014: 264). The monetarist approach to time can also be seen in the belief that although time flows independently of us, the way and rate at which we earn in that time depends on the worker’s productivity (Adam 1994: 113). The central role of time in the organisation of our profit-driven reality is also emphasised by Crary (2022). The author sees the manifestation of opposition to time-consuming mechanisms in sleep – ‘sleep is a radical break in the theft of our time carried out by capitalism’ (Crary 2022: 23). Difficulties related to leisure are caused by the blurring of the boundary between ‘working time’ and ‘after-work time’ (Standing 2019: 259), which in turn is linked to flexible working hours and the feeling of constant availability (Mroczkowska 2023: 13), which Crary categorises as the state of ‘dormancy’ (Crary 2022: 42), i.e. a constant state of readiness. Some researchers argue that leisure is a non-existent concept (Kosiewicz 2012) or difficult to define (Czajkowski 1979: 17; Niezgoda 2014: 103); others adopt assumptions regarding the objectivity and subjectivity of time (Neulinger, cited in Mokras-Grabowska 2015: 17). In the context of the discussion presented in this article, I consider the most important aspects of leisure to be ‘freedom, choice, and self-expression’ (Mroczkowska 2020: 147), and more broadly:

leisure is an activity that, first, takes place in time, yet is not defined by time or space but by the attitudes and emotions associated with it [author’s emphasis: H.S.]; second, it can take forms that are infinitely diverse, yet still allow for identification; third, it is a processual experience, realised through action, not just a state of mind or mood. Moreover, freedom is not the absence of boundaries or limitations, but is linked to self-determination (Kelly 1996: 20–25, cited in Mroczkowska 2020: 135).

I will consider the time in the catering industry based on the data obtained from the perspective of (1) short time, a period of one day spent within the work itself, a kind of ‘here and now’, using which I will approximate the structure of a working day in the catering industry, (2) medium time – a perspective of about one month, through which I will illustrate the ‘near’ but not immediate consequences experienced as a result of short time processes, and (3) long time, by means of which I will show a broader biographical perspective in the context of long-term consequences, that is, consequences that are not directly noticeable but that shape the individual’s life story, particularly their opportunities in the labour market and social security. I see time in the catering industry as social time, i.e. qualitative rather than quantitative time, which:

Does not run in one direction but is reversible, it can be linear, cyclical, spiral, recurring. It does not contain a single, mutually translatable system of measurement, but many different systems. It is not an empty lapse, but a factor affecting social life, influencing people’s behaviour, inducing certain actions (Tarkowska 1993: 23).

Short, medium and long-term in hospitality are not three separate units of measurement – they are all separate areas creating unique conditions for a given time while at the same time remaining in a close relationship, making it impossible to analyse them separately.

4. Methodology

The main research question posed in this paper is: What are the methods by which precarious mechanisms existing in the labour market are utilised to organise work in the hospitality industry, and what is the impact of these mechanisms on employees?

The research underlying the paper was conducted as a part of a research project within a grant from the ID-UB program titled ‘Gastroproblems, or precarity of Polish hospitality workers’. The research was carried out in two stages: quantitative (duration: 23.01.–17.04.2024) and qualitative (duration: 9.03.–27.05.2024). The quantitative phase was conducted using an online questionnaire tool distributed via social media, specifically in Facebook groups dedicated to the catering industry. The survey was aimed at former and current female and male catering staff employed between 2020 and 2024, which was verified by a filter question. As a result, I obtained responses from 446 respondents (including 298 current and 148 former catering staff): 320 female, 113 male, 11 – gender ‘other’ and 2 – ‘prefer not to specify’. The quantitative survey consisted of seven sections related to (1) seniority and nature of work in the catering industry, (2) contract, (3) working conditions (safety), (4) welfare and health, (5) pay, (6) relationships at work and (7) private life.

The qualitative phase was conducted using the in-depth individual interview method with a structured interview scenario and medium flexibility, in which themes were deepened depending on the additional topics taken up in the interview, and resulted in 12 people being interviewed (including four men and eight women, aged 20–31) from Krakow, Wroclaw and Poznan. The selection of cities was motivated by the wide range of catering offers; the selection of respondents was purposeful, as I was keen to reach people with a wide variety of individual situations and experience in the catering sector. The predominance of women is justified by increased access to this group, unlike men, for whom reaching out was a limitation; the age of the respondents results from the very high availability of this age range. Participants in the survey were former and current employees, people making a living in the catering industry, people regarding the sector as their supplementary income, students and non-students, people with many years of experience, and people with about a year’s experience. The interviewed participants are hospitality workers employed as waiters, bartenders, baristas, cooks, runners, and salespeople and are employees of bars, restaurants, cafés, patisseries-bakeries and beach bars, both local and corporate. The accompanying quotations in the article are taken from the respondents’ statements and coded sequentially by interview number, gender (F: female, M: male) and age of the respondents.

The approach used to analyse qualitative data is thematic analysis (TA) (Maison 2022: 271–272). The data coding stage and further analysis showed that the experience of precarity and mechanisms specific to the catering sector vary depending on a given period, directly related to the physical presence and absence of work by employed people. Time also turned out to be one of the most important categories in work in the catering industry, and it was time that stood out in the statements of working people regarding their past, present and plans for the future. Data from the quantitative analysis stage in the article were selected from the areas of employment, remuneration, sense of representation, and work organisation. The collected material from the survey indicates the scale and intensity of the phenomenon of precarity (in particular, flexibility and lack of economic and social security). It exemplifies the dominant tendencies in the food industry, thus corresponding to the data from the qualitative study. The combination of quantitative and qualitative methods filled the gaps in both approaches – it made it possible to reach a broad group of people and map gastronomic processes and honoured personal stories that reflected the sector’s complexity in a more detailed way. Considering the limited autonomy in time utilisation by the precariat (Standing 2014), I decided to draw on chronosociology and establish time as a catalyst for gastronomic processes to understand them better.

5. Short time

I perceive a short time as part of a day within the processes during work. Adopting this perspective more accurately reflects the characteristics of the organisation of work in the catering business. Short time captures male and female workers in the exact moment of experiencing working in the catering industry, allowing them to see their ‘here and now’.

5.1. Marathon runners: Long-lasting intensity and no control over time

Pay per hour worked is the mechanism by which I would like to point out the short-time perspective. It is one of the trappings of the flexible model of precarious employment, based on the logic of work determined by proverbial will and desire, upon which an individual’s financial capital depends. This is directly related to the shift from the welfare state, the organisation of the social insurance system, to workfare, the ‘readiness to work’ system (Mrozowicki, Czarzasty 2020: 36), where financial benefits, within the framework of individual efforts, may be allocated to social benefits (McDowell 2001). The mandate contract and the hourly minimum wage entirely shift the responsibility onto the individual – it is up to them to decide how many ‘hours they will work’, i.e., how high their salary will be. The hourly wage seems to suggest that working individuals can earn as much as they want – the wage level is determined by their decisions regarding work duration rather than a fixed salary. This leads to multi-hour marathons, ‘working beyond their limits’ (Standing 2019: 243), during which those working in catering operate, disregarding physiology and the body. Eleven out of twelve participants in the qualitative study cited situations where they worked a dozen hours daily. Only one person did not have this experience – due to working in a catering corporation, where working hours are regulated by law:

(...) I was there every day for 14 hours at a time, so I didn’t have a period specifically to not be at work even physically (...) as I think about it now, I very much wonder how I managed to do it physically for 2 months (2M21).

Hours spent at work are hours taken away from leisure time. In the case of marathons, the working time does not total the typical eight but rather a dozen or so hours:

(...) I neglected some family relationships, I neglected close acquainances, all because of being at work. Well, it may sound ridiculous, but well that was the case that you were constantly at work and didn’t have time for anything else (5K25).

Interviewees pointed out that shifts of a dozen or so hours put a noticeable strain on the body, both physically and mentally:

And it was just that the work was hard in that, especially, in the first place, that there was also mega traffic there, it was very hard, and it was a 12-hour job (...) (6K22).

In the context of a temporal analysis of the precarious catering industry, the lack of control over one’s own time becomes an important theme. Marathons also occur because of unclear working hours, depending on the intensity of duties and the number of visitors. They result in unplanned, longer stays at work. The time spent completing duties depends on the actions of those working, and, as with hourly pay, the responsibility lies with them:

(...) you still have to clean the whole place afterwards, for example, while you work an extra 3 or 4 hours (11K21).

Catering marathons are often undertaken not of one’s own free will – working several hours is often not the result of a conscious decision but is the result of financial needs and the unpredictability of the working environment. A person working in a catering business can, therefore, easily lose control of their time through the externally established remuneration mechanism of flexible forms of employment and as a result of the intense randomness – the unpredictability of the course of the working day, depending on the number of service recipients – of the catering industry. Awareness of a non-guaranteed fixed salary results in pernicious ‘working the hours’ that should become more rewarding. The bluff of temporal precarity is that even if an individual receives a satisfactory payout, the costs they incur in return will be even higher.

5.2. Sprinters – a battle against time

People working in the catering industry are not only participating in marathons – in fact, virtually every day at work in the catering sector is also similar to a short-distance run, intending to complete the duties as quickly as possible. The pace of work, i.e. completing one task quickly and undertaking the next efficiently, is one of the most important time categories of catering work. Again, the responsibility for getting the job done rests with the workers. It is evident from the statements of the female and male catering workers that pressure and pace are not abstract notions; instead, they are bodily and mentally felt and exercised in practice:

(...) it is not an easy job because it is a job under pressure. If you don’t serve something on time, you are chasing time, so someone resents you for not serving it. You, however, are trying to do it faster, even though you’re busting a gut (5K25).

Time pressure is embedded in the daily organisation to such an extent that it permeates how a person working in the catering industry functions. The rapid pace of work and the accompanying stimuli are adapted, even become desirable and practised, but this does not mean that they are not problematic:

I catch myself being able to get ahead of the customer, that the customer hasn’t finished the transaction yet – the coffee is already waiting for them. (...). Also, I don’t feel some kind of terrible pressure, but that is due to the fact that I have learned (7M20).

The relentless passing of time, like a ‘go’ command and the firing of a sporting gun, dictates the behaviour of the caterer throughout their shift. Time creates pressure and tension and transfers the emphasis of importance from the individual to their performance. For those working in the catering industry, the relevance of passing time is felt in the course of work from a ‘here and now’ perspective. Operating within such an outlined time frame makes it difficult to live according to a long-term perspective and reflect on the far-reaching consequences of such a way of life.

5.3. No breaks: Do not sit, eat, or breathe – work

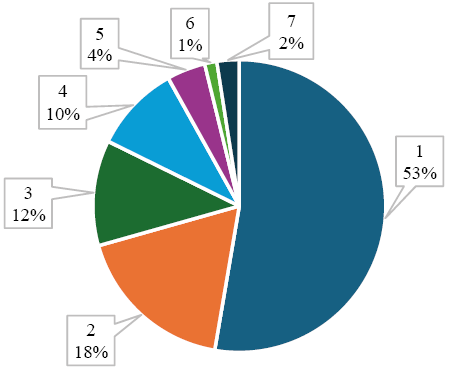

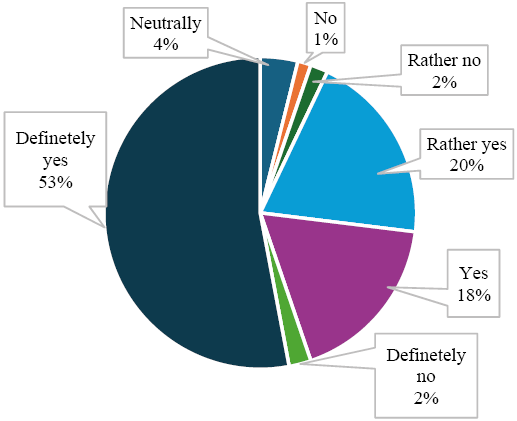

While discussing the daily organisation, the situation of breaks needs to be carefully examined. The quantitative survey results show that break time in the catering business is essentially absent. The number of responses to the first question (‘breaks were when there was little traffic’) of 53% illustrates the scale of the worrying organisation of breaks.

Source: author’s study.

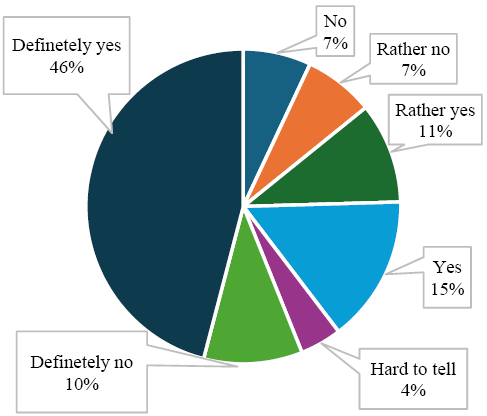

The lack of breaktime translates into difficulties in meeting the most basic physiological needs, like eating, drinking or using the toilet, which are essential for the proper functioning of the body and the well-being and productivity of the worker. In varying degrees of severity, these difficulties were encountered by 72% of respondents (‘definitely yes’: 46%, ‘rather yes’: 11%, ‘yes’: 15%).

Source: author’s study.

The results obtained from the qualitative interviews show that the guarantee of a break is held by employees of catering corporations, such as ‘McDonald’s’ and ‘Starbucks’, where the corporate structure dictates that they take a 15-minute break. Only one of the twelve people surveyed was aware of the upcoming guaranteed break when going to work. The remaining eleven participated in a game where the stakes were to use the toilet or eat a meal.

I will say this, in general, and everywhere in catering: there is no such thing as a break time (11K21).

The vast majority of participants in the qualitative interviews categorised the lack of break time as a difficulty. At the same time, those who were satisfied with their current workplace (due to good working relations, the prevailing atmosphere, etc.) or those with more seniority (which meant more privileges) noticed the lack of breaks but were compensated for it by the aforementioned factors. Conversations with people working in the catering industry revealed two ways to enable more breaks: (1) courtesy of colleagues who work together to create more opportunities for a break:

If there’s a need [for breaks], that’s not a problem either, but it’s already so internal to us at a particular café, and it’s just our initiative that it works that way (12M23).

Moreover, (2) smoking as a pass to go out for a break:

Well, and the break time is usually when you go out for a cigarette. This is the easiest way. (...) in most places, it’s basically the case that if there’s a bit of traffic, you can go out for a smoke (9K22).

A catering marathon or sprint is challenging to interrupt due to the lack of dedicated break time. This is usually not a matter of restaurant policy – interviewed respondents cited situations where they neglected their well-being primarily due to the whirlwind and pace of work rather than the rules. A dedicated break time could interrupt the intensity of the work and have a positive impact on the well-being of the workers. The work in catering revolves around the passage of time, which is dictated by the rhythm of individual activities. Nevertheless, as strongly as it prioritises it at work, it downplays it in matters of importance to the individual – rest, breaks, paid holidays, weekends off, a fixed rather than an hourly wage.

The lack of breaks, the sprint, and the marathon are specific features of the daily work organisation that must be analysed from a short-term perspective. The effects of short-time processes, on the other hand, must be sought in the medium-time.

6. Medium time

I categorise the medium time as lasting between one week and one month, i.e. the length of a few to a dozen or so days of work – during such a period, it is possible to see recurring work patterns in catering and to test the correlation between work and employees’ well-being. This perspective also makes it possible to see the close consequences of working in catering, holistically affecting the employees’ lives.

6.1. Limited control of decision-making over your own time: Time thieves

The determinants of the lack of control over time felt by those working in the catering industry should be sought regarding the intensity of the environment in terms of the stimuli experienced. I will use a medium time to analyse the problematic nature of the stimuli in terms of cause and effect. The quantitative survey results showed that those employed in catering perceive it as a particularly challenging industry in terms of the specific situations experienced. The combination of service and commercial work aspects, with simultaneous contact with food and the performance of physical labour, creates a specific working environment where different sectors and industries intersect.

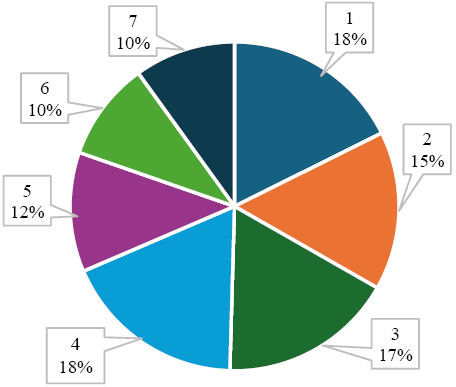

Source: author’s study.

The accumulation of various stimuli in the form of communication between employees, contact with customers, performing multiple tasks simultaneously, time pressure and working at a fast pace, accompanied by the sounds characteristic of catering establishments, creates a demanding and unique working environment. The stimuli are so intense and long-lasting in their effects that they remain in the workers as a sludge [in Polish: ‘osad’] (Krajewski 2016) – the residue of an intense series of events, i.e. a sequence of days working in catering. The stimuli are closely related to overwork – a series of stimuli, together with demanding physical work, result in ailments that indicate a considerable amount of work interfering with the well-being of individuals. Overstimulation-overwork, a kind of ‘de-episodisation’ (Krajewski 2016: 156), is vented off after work and has consequences for an individual’s private life – it interferes with the nature and conduct of relationships, mental and physical well-being and how time is spent after work.

It’s certainly also often the case that you feel the shift on the second day, your legs hurt, your arms hurt, some kind of soreness appears, so the shifts are felt very strongly, also physically (7M20).

(...) I’ve neglected my partner, for example, because really, the only thing you want is just to lie down, sleep, take a bath and just say absolutely nothing (5K25).

Catering employees have limited control over their own free time, which is devoted to unwinding and calming down after work. Overwork and its consequences, like thieves robbing people working in the catering industry of their time. Work dictates the nature of private free time:

There are times when I just get overstimulated to the max, and if 0150 I don’t even want to, when I come home or watch any TV series, movie, I just want to lie down (10K31).

The separation of time catering workers into ‘work time’ and ‘after-work time’ therefore seems a breakneck procedure. The ‘after-work time’ seems to be a convalescence, during which the individual physically and mentally feels the effects of working in catering. I consciously use the concept of ‘time after work’ instead of ‘free time’ because, following Mroczkowska (2020), I notice significant difficulties in considering it as evidence of ‘freedom’ and the possibility of ‘choice’ of employees, especially since their own ‘attitude and feelings’ do not indicate that. The transition from the work sphere to the private sphere is not easy to achieve. Work-related situations or responsibilities remain with the individual once they leave work and imperceptibly creep into leisure time, preventing full-time rest:

In fact, sometimes it happens that in the evenings you still think about either not having done something, for example, or that you still have to do something, so sometimes it’s mentally hard work too, not only physically (8M22).

A medium-term perspective of a few weeks or months makes the precarity of catering workers visible, as it demonstrates the precarious pattern of working in the catering industry – not one, but a whole series of days working under time pressure, holistically affects the person working in catering.

6.2. The work of some, the relaxation of others: Disproportions in free time

In the context of the catering industry, I also notice a temporal paradox in the perception of so-called days off: weekends, holidays, or the summer period in general, a higher holiday season. By definition, these are days off work and, therefore, a time of rest or relaxation. At the same time, the opposite is true for people working in catering – not only is it not ‘leisure time’ for them, it is actually ‘working time of increased intensity’:

You can definitely feel the pressure on days like this [weekend], because you have to make decisions quickly, do things quickly and very erm, so to speak, have things in order and make good use of the moments when things are quieter (12M23).

Catering workers often cannot use their statutory days off, as they function as ‘normal’ working days included in their professional obligations. Respondents classified these as difficulties in time management and an obstacle to ‘full’ rest:

(...) it’s working on all the holidays and on May Day; however, the lack of time off at weekends bothers me personally. Because I lead such a lifestyle that it would suit me better to work from morning to afternoon and maybe not at weekends, but well, you know that’s not going to happen (4K24).

The data from the qualitative interviews demonstrate an important feature of the catering work – namely, the use of catering services in legally regulated free time and the rest taken in them are only possible thanks to other people’s work. Catering is the sector that organises the majority of society’s free time.

A conclusion should undoubtedly be drawn – the understanding of time by those working in catering differs from other people’s conceptualisation of it. A medium-term perspective also makes it possible to note that time is not under control. Thanks to assuming the perspective of a few weeks, a pattern can be seen: (1) the dynamism and density of the activities undertaken at work are the result of the demands placed on those working in catering, which prioritise the pace of work and its rhythmic flow over human capacity, (2) which in turn makes an impact on the health and well-being of the individual. (3) To function appropriately, the individual isolates themselves from those close to them and gives up extra activities – (4) recuperates but does not rest. Because of this, (5) the time after work is not necessarily free – as the freedom to choose how to spend it is minimal and often sacrificed to mitigate the effects of overwork – instead, it is a period of recovery, during which work is still alive. One thinks about it and experiences bodily sensations, i.e. an intrusion into private life and ‘(not) free time’.

7. Long time

I assume that the long time is a perspective of one to several years. This allows us to see the ‘further’ consequences of working in catering, that is, the mechanisms that produce or maintain precarity, whose presence seriously and profoundly affects the stability and security of an individual’s life. Their importance is minimised in favour of immediate advantages, which aligns with the idea of flexibility. The issues below relate to Standing’s (2014: 49) insecurities: insecurity of employment and representation.

7.1. Job at once, please, or protracted temporariness and insidious flexibility

The catering sector is based on seasonality, which is not just related to the season or bank holidays but is also reflected in how its employees treat it. The workers in the catering industry regard it as seasonal, i.e. temporary and momentary, because it quickly satisfies the need to get a job and earn money. Although the impulse is the same, as demonstrated by participants in the qualitative interviews, the motivations for taking up work are varied, often coupled with a change in life situation – starting university, moving house, graduating from high school, wanting to make the most of free time on holiday:

And, and overall, I was kind of just looking for that kind of casual work. I don’t know if casual, well, just a source of income (9K21).

Getting a job in most catering establishments is relatively easy due to the fast recruitment and training process. Fast, because time is of the essence: for employers, it is a question of keeping the current performance of duties, which results in a rhythmic flow of customers and the money they spend; for employees, getting work sooner means getting paid sooner and having stable living conditions.

The taking up of work should involve signing a bilateral agreement, which, however, does not have to be based on labour law: ‘taking up work without a legal basis or in a form other than specified in the labour law is also to be regarded as the establishment of an employment relationship’ (Lipiec 2022: 33), resulting in contracts of questionable quality and unclear terms of employee protection. Most respondents to the quantitative survey reported working without a contract (‘several times’: 49%, ‘very often’: 12%) despite being ‘officially’ hired, which illustrates the current illegal employment of people ‘off the books’. The vast majority of respondents (71%) identified the contract of the mandate as the predominant form of employment, illustrating the high flexibility of catering and, therefore, its precarious nature. It is difficult to categorise the results regarding the perception of safety and security provided by a binding contract. The sense of security provided by the contract ranked 3.6 on a 7-level scale, with 39.5% of the responses indicating levels 1–3 come from respondents bound by a contract of mandate.

Source: author’s study.

This allows for a conclusion that, in the minds of respondents, the contract of mandate is unlikely to ensure security for workers and that issues related to the terms and conditions of employment are not the most commonly addressed for those working in catering.

Most respondents (ten of whom were bound by a contract of mandate, two by an employment contract) demonstrated a predominantly positive attitude towards the contract of mandate, with respondents under 26 and students seeing it as beneficial. They saw the flexibility associated with the contract as an advantage and an opportunity to combine work and study. The qualitative interviews also illustrated Senett’s ‘nothing for long’ concept in working in the catering industry. None of the people considered working in the catering sector as purely gainful employment, quite to the contrary, they were able to point out the positive impact of working in catering on their own lives and showed satisfaction with their activities. However, only one of the twelve people saw their future in it. A common argument in this regard turned out to be a salary that was disproportionate to the workload:

I don’t think it’s going to be a job forever, although I’d like to, but still, no, no, it’s not possible, well, because you can’t make a living out of it (4K24).

A widespread tendency among respondents to temporarily treat work in the hospitality industry as a source of income before securing their desired job fits into the concept of a bridge (Giermanowska 2013), i.e. a path intended to facilitate the transition from unstable to stable employment. Precarious employment and the exposure to deepening precarity were not seen by the interviewees, who were still studying, as a threat, but rather as a state easily changeable depending more on their own decisions than on the labour market:

I consider it as an additional activity alongside studying, so the financial aspect [the salary amount] is not that painful (12M23).

Former catering workers drew attention to the unfavourable social insurance and security provisions of the contract of mandate:

(...) for example, I was not happy with being a catering worker and having a contract of mandate because it is such a junk contract for me, it doesn’t really give me any guarantee, and it’s as if the time that, for example, that I have worked for 4 years in catering has escaped somewhere, no, because, for instance, that period will not go towards my retirement (5K25).

Furthermore, the difficulties in finding a job in the profession or a job more attractive than work in the catering industry:

(...) Well, I hope I won’t go back to working in hospitality. But still... I suspect life will verify that (...) Many of my friends who are looking for jobs also have a big problem finding work. There are just very few job offers and many candidates for one position (3K22).

A day-to-day life that lasts weeks, months or even years goes against the idea of temporary and flexible working. The danger is that ‘for a while’ can imperceptibly turn into ‘for a long time’ or ‘I don’t know how long’. The essence of the flexibility trap spans a long term – in the short term it offers many benefits and a (false) sense of control over one’s life, but is not reflected in the context of the individual’s overall life, long-term benefits and security.

7.2. The urgent need for recognition and lack of representation

Using the long time, i.e., the long perspective, I would like to illustrate another problem-consequence related to working in the catering industry: the lack of representation of the employees in this sector and, consequently, the lack of public interest in their important work. According to Graeber’s thesis (2018) on the meaning of work, working in the catering industry is an activity of individuals that positively affects other people’s lives without causing harm, and therefore, it is meaningful work. This is also how participants in the interviews spoke about their work:

It may not be a job that saves lives, but it is a job that makes other people happy, and that is what I found rewarding (3K22).

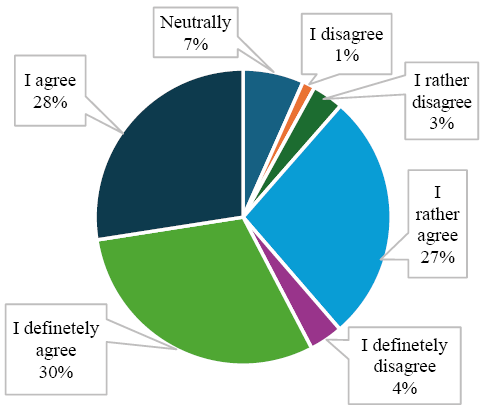

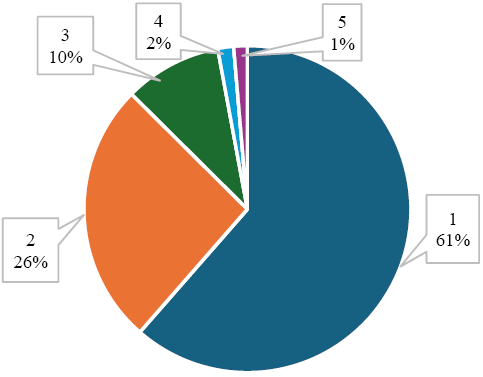

The sense of having a socially important role is a widespread phenomenon. The quantitative survey showed that this is a belief, not an individual testimony, shared by catering workers.

Source: author’s study.

Although not a ‘life-saving job’ or a job that shapes or supports the well-being and awareness of society (as is the case for those working in education or health care), catering work has been around for decades. However, it does not translate into a noticeable self-organisation of workers or their visibility by the rest of society, as the qualitative and quantitative survey data showed:

But I also think that even most people don’t realise that it’s really hard work and not just mentally, but physically as well (...) Well, and it’s sad that nobody takes us a bit more seriously (10K31).

They don’t consider the factors a person is going through. When working in the catering industry, due to the lack of knowledge (...) they treat this interaction and the person working in this position in such a very automatic way that they simply come in and think to themselves: “Okay, I came here for coffee (...) and I don’t care how these people have to do it in order for my expectations to be met” (1K22).

Source: author’s study.

The sense of having a socially relevant role does not come with a sense of having a noticeable representation, which is another pitfall of flexibility and a feature of precarious work. Describing the catering industry from a long-term perspective shows that the lack of representation of hospitality workers is a long-term phenomenon. The consequence of the lack of representation is the low visibility of people employed in the catering industry, i.e., society does not notice their needs. Considering the importance of gastronomic actors in society’s everyday lives, their lack of appropriate representation is concerning.

A long-term outlook sheds light on the neglected need to notice and recognise those who work every day in a sector that is important to society. Recognising those working in the catering industry and assuring representation could positively translate into improving their economic and social standing.

8. Conclusions

By analysing the results obtained employing the category of time, it can be seen that processes occurring in hospitality (1) are rooted in the precarization of the industry, manifesting in flexible employment forms, hourly wages, and a lack of social security, and (2) are also embedded in the temporal aspects specific to catering – its organisation, pace and rhythm, as well as the hourly-based wage system, all of which are oriented toward task completion in insolation from human needs and constraints. Catering work is physically demanding and involves significant interaction with others, leading to various situations that result in overwork and emotional exhaustion. Issues related to precarization, temporal categories, and the sector-specific conditions described in this article constitute what I term ‘gastroproblems’, which affect the entire economic, legal, and social trajectory of individuals employed in hospitality. When examining the catering work, it can be observed that the employees perceive it as beneficial from a collective life perspective and consider their work meaningful. Awareness of the lack of social security and the difficulties associated with job responsibilities does not diminish the attractiveness of the work – even when changing jobs, workers choose to stay within the sector, as its flexibility is particularly appealing to young people. One wonders, therefore, whether catering offered more attractive working conditions and opportunities for development, people working in it would be more likely to tie their future to it rather than treating it as merely temporary.

The results of the quantitative survey and the statements from the qualitative study showed that considerations of precarity are strongly coupled with the extent of an individual’s subjectivity in the face of passing time. When it comes to the working time of the catering employees, short, medium and long, influencing and managing it is not easy to achieve and is gradually being reduced. The situation of those working in catering could be improved by balancing the time spent working with economic and social benefits and increasing their visibility within the rest of society.

Projekt badawczy i artykuł powstał przy pomocnych konsultacjach naukowych z prof. UAM dr. hab. Przemysławem Nosalem, za które autorka serdecznie dziękuje.

Autorzy

* Hanna Szalecka

Bibliography

Adamkiewicz W.B., Zielińska J. (2024), Praca w “małej gastronomii” z perspektywy zatrudnionych w Warszawie i Wiedniu. Studium przypadku, “Przegląd Socjologii Jakościowej”, vol. 20, no. 2, pp. 196–219.

Bednarczykówna K. (2018), Kelner to jest misja. Dziś kelnerów nie ma, są podawacze jedzenia. 10 przykazań dla kelnera [REPORTAŻ], https://warszawa.wyborcza.pl/warszawa/7,54420,23060551,kelner-to-jest-misja-dzis-kelnerow-nie-ma-sa-podawacze-jedzenia.html?utm_source=mail&utm_medium=art_polecane&utm_campaign=artid_23060551&token=TUC3fg_3g2de8KLCP-kSVruf1Wnj-8joRWIgGgCH2-P0UWBo5FO-2_-7c97cBcUX (accessed: 24.08.2024).

Błażewicz A., Cichoń D. (2024), Delivery Heroes. Bohaterowie na wynos, https://teatr-polski.pl/spektakle/delivery-heroes-bohaterowie-na-wynos/ (accessed: 24.08.2024).

Butler J. (2009), Frames of War: When is Life Grievable?, Verso, London.

Crary J. (2022), 24/7: późny kapitalizm i celowość snu (trans. D. Żukowski), Karakter, Kraków.

Czajkowski K. (1979), Wychowanie do rekreacji, Wydawnictwa Szkolne i Pedagogiczne, Warszawa.

Durkheim É. (2010), Elementarne formy życia religijnego. System totemiczny w Australii (trans. A. Zadrożyńska), Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, Warszawa.

Giermanowska E. (2013), Ryzyko elastyczności czy elastyczność ryzyka. Instytucjonalna analiza kontraktów zatrudnienia, Wydawnictwa Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, Warszawa.

Gładczak P. (2019), Pracownik – największy problem gastronomii?, https://wroclawskiejedzenie.pl/2019/12/13/pracownik-najwiekszy-problem-gastronomii/ (accessed: 24.08.2024).

Graeber D. (2018), Praca bez sensu. Teoria, http://pl.anarchistlibraries.net

GUS (2021), Wpływ pandemii COVID-19 na koniunkturę gospodarczą – oceny i oczekiwania (dane szczegółowe oraz szeregi czasowe). Aneks do publikacji “Koniunktura w przetwórstwie przemysłowym, budownictwie, handlu i usługach 2000–2021 (marzec 2021)”.

GUS (2023), Rynek wewnętrzny w 2022 r.

Hall E.T. (1999), Taniec życia. Inny wymiar czasu (trans. R. Nowakowski), Warszawskie Wydawnictwo Literackie MUZA, Warszawa.

Honneth A. (2012), Walka o uznanie: moralna gramatyka konfliktów społecznych (trans. J. Duraj), Zakład Wydawniczy „NOMOS”, Kraków.

Kaleta E. (2016), Gastrowyzysk. Pracownicy gastronomii zakładają związek zawodowy, https://wyborcza.pl/duzyformat/7,127290,20493477,gastrowyzysk-pracownicy-gastronomii-zakladaja-zwiazek-zawodowy.html (accessed: 24.08.2024).

Kiersztyn A. (2015), Niepewne uczestnictwo – młodzi na polskim rynku pracy w latach 2008–2013, Instytut Filozofii i Socjologii Polskiej Akademii Nauk, Warszawa, https://rcin.org.pl/publication/176596/edition/204245/niepewne-uczestnictwo-mlodzi-na-polskim-rynku-pracy-w-latach-2008-2013-wybrane-wyniki-polskiego-badania-panelowego-polpan-1988-2013-kiersztyn-anna-orcid-0000-0001-8112-6059?language=pl (accessed: 8.02.2025).

Kosiewicz J. (2012), Free Time versus Occupied Time in a Philosophical Context, “Physical Culture and Sport. Studies and Research”, vol. LV.

Krajewski M. (2016), Incydenty. Badając gęste społeczeństwo, “Studia Socjologiczne”, vol. 2, no. 221, pp. 145–162.

Kramarczyk J. (2018), Życie we własnym rytmie. Socjologiczne studium slow life w dobie społecznego przyspieszenia, UNIVERSITAS, Kraków.

Lebhar G.M. (1958), The use of time, Chain Store Publishing Corp., New York.

Lipiec S. (2022), Gastronomia. Praca i prekariat. Studium socjologiczno-prawne, Wydawnictwo Rys, Poznań.

Lorey I. (2015), State of Insecurity: Government of the Precarious, Verso, London.

Maison D. (2022), Jakościowe metody badań społecznych. Podejście aplikacyjne, Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, Warszawa.

McDowell L. (2001), Father and Ford Revisited: Gender, Class and Employment Change in the New Millennium, “Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers”, vol. 26, no. 4, pp. 448–464.

Mika B. (2023), Satisfaction Despite Precarity. Applying the Concept of Flexibility to Understand Tricity Uber Drivers’ Attitudes to Their Work, “Miscellanea Anthropologica et Sociologica” 2022, vol. 23, no. 2–3, pp. 125–141.

Mokras-Grabowska J. (2015), Czas wolny w dobie postmodernizmu, “Folia Turistica”, no. 34.

Mroczkowska D. (2020), (Z)rozumieć czas wolny. Przeobrażenia, tożsamość, doświadczanie, Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Adama Mickiewicza, Poznań.

Mroczkowska D. (2023), Czas wolny – o codziennych i niecodziennych scenariuszach doświadczania, “Studia Humanistyczne AGH”, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 13–32.

Mrozowicki A., Czarzasty J. (2020), Oswajanie niepewności. Studia społeczno-ekonomiczne nad młodymi pracownikami sprekaryzowanymi, Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar, Warszawa.

Niezgoda A. (2014), Czas wolny a zmiany na rynku turystycznym, [in:] Przeszłość, teraźniejszość i przyszłość turystyki. Warsztaty z geografii turyzmu, Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego, Łódź, pp. 101–112.

Palęcka A., Płucienniczak P. (2017), Niepewne zatrudnienie, lęk i działania zbiorowe. Trzy wymiary prekarności, “Kultura i Społeczeństwo”, vol. 61, no. 4, pp. 65–85.

Pawłowska A. (2017), Byłyśmy zastraszane, wyśmiewane i upokarzane. Pracownice kociej kawiarni przeciwko właścicielce, https://noizz.pl/spoleczenstwo/bylysmy-zastraszane-wysmiewane-i-upokarzane-pracownice-kociej-kawiarni-przeciwko/tsk1wkd (dostęp: 24.08.2024).

Pobiedzińska J. (2020), Napiwku nie będzie: sekrety kelnerów, Agora, Warszawa.

Polkowska D. (2019), Między światem realnym a wirtualnym: obietnice vs. rzeczywistość. Prekarna praca kierowcy Ubera?, “Przegląd Socjologii Jakościowej”, vol. 15, no. 4, pp. 224–249.

Polkowska D. (2020), Platform work during the COVID-19 pandemic: a case study of Glovo couriers in Poland, “European Societies”, vol. 23, pp. S321-S331.

Polkowska D. (2023), Przyspieszenie czy spowolnienie? Praca platformowa dostawców jedzenia w dobie pandemii Sars-Cov-2, “Studia Socjologiczne”, vol. 4, no. 243, pp. 109–133.

Sennett R. (2006), Korozja charakteru: osobiste konsekwencje pracy w nowym kapitalizmie (trans. J. Dzierzgowski, Ł. Mikołajewski), Warszawskie Wydawnictwo Literackie MUZA, Warszawa.

Sennett R. (2010), Kultura nowego kapitalizmu (trans. G. Brzozowski, K. Osłowski), Warszawskie Wydawnictwo Literackie MUZA, Warszawa.

Standing G. (2014), Prekariat: nowa niebezpieczna klasa (trans. K. Czarnecki, P. Kaczmarski, M. Karolak), Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, Warszawa.

Szymkowiak H. (2021), Polska gastronomia w czasie pandemii, “Tutoring Gedanensis”, vol. 6, no. 1, pp. 79–88.

Winogrodzka D., Mleczko I. (2019), Migracja płynna a prekaryzacja pracy. Przykłady doświadczeń zawodowych młodych migrantów z wybranych miast średniej wielkości w Polsce, “Studia Migracyjne – Przegląd Polonijny”, (XLV), vol. 171, no. 1, pp. 85–106.

Wysocka E. (2013), Wschodząca dorosłość a tożsamość młodego pokolenia – współczesne zagrożenia dla kształtowania tożsamości. Analiza teoretyczna i empiryczne egzemplifikacje, “Kwartalnik Colloquium Wydziału Nauk Humanistycznych i Społecznych”, no. 1, pp. 69–96.

Zielińska J. (2014), Współczesny rynek pracy w Polsce. Kondycja psychospołeczna i ekonomiczna. Prekariat w branży gastronomicznej, [in:] H. Liberska, A. Malina, D. Suwalska-Barancewicz (eds.), Współcześni ludzie wobec wyzwań i zagrożeń XXI wieku, Wydawnictwo Difin, Warszawa.

Zielińska J. (2015), Dwuznaczny urok elastyczności, czyli o pracy w branży gastronomicznej, “Polityka Społeczna”, vol. 492, no. 3, pp. 20–25.