https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5781-4297

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5781-4297

Abstract. The aim of this article is to examine, based on a literature review, the status of menstruation in professional sport from a sociological perspective. The first part of the article describes the broader sociocultural context that frames the perception and experience of menstruation and is followed by a review of the literature focused on sport. In the second part, the main factors that shape the status of menstruation in professional sport, i.e. the culture of concealment, the characteristics of the sport, the sport media coverage and menstrual activism, are discussed. As the article reveals, the coexistence of these factors causes that, on the one hand, menstruation is rarely the object of communication, mainly addressed to a broader public; on the other hand, menstrual activism contributes to some changes related to dress code or open discussion on menstrual issues. The conclusion indicates the meaning of sociological studies of menstruation in sports, pointing out the importance of the topic in basic and applied research and its social impact.

Keywords: menstruation, professional sport, sociology, culture of concealment, menstrual activism.

In the social sciences, research concerning menstruation has been conducted for several decades, and critical menstrual research has been developed recently (Bobel et al. 2020). However, professional sport is rarely the subject of this research. Rather, this literature covers physical activity in two contexts: (1) limited physical activity during periods and promises by the producers of menstrual products to lift restrictions on activity, and (2) the withdrawal of girls from physical activity, including physical education (PE) at school, during menstruation. Moreover, menstruation issues are omitted in publications concerning gender and sport, whose number has been increasing significantly in recent years.

Meanwhile, menstruation in professional sport is an exceptionally interesting and important topic of social research related to women and sport for at least three reasons. First, because of the centrality of the body, which seems reasonably obvious. A success in sport depends on the form of the body and its disposition on a day of competition. The body is crucial during training and sports performance, and any physical ailments, including menstrual cramps, may impact one’s results. Therefore, menstrual cycle management (adapting training, shifting the period, communication with the coaches and physicians, etc.) may be one of the crucial factors influencing a chance to achieve a good result in a competition. Second, sport is characterised by a constant display of the body. The stigma of menstruation is associated mainly with a leaky body, and female athletes frequently have limited choices regarding the uniforms in which they perform. Although some sports organisations have changed their dress codes or sport kits to make it easier for female athletes to hide their periods, “skimpy” and/or white outfits can still be a source of menstrual concerns. Third, sport privileges the male body and the values associated with it. In this context, concealing menstruation by female athletes can be interpreted as hiding biological femininity and the assumed weakness of the female body.

The aim of this article is to examine, based on a literature review, the status of menstruation in professional sport from a sociological perspective. In the first part of the article, I describe the broader sociocultural context that frames the perception and experience of menstruation. Then, I review the literature on menstruation in professional sport. In the second part, I present and discuss the main factors that shape menstruation’s (in)visible status in the sport, related on the one hand to the broader sociocultural context (in which menstrual activism confronts the culture of concealment) and on the second hand to the specifics of sport and (sport) media coverage.

Menstruation is personal and political, private and public, biological and sociocultural. On the one hand, it is an intimate, personal experience resulting from the physiology of the female body; on the other hand, the practices associated with it are regulated through sociocultural norms. Although menstruation is commonly associated with women, it is important to recognise that individuals across the gender spectrum, including some trans men, can also experience menstruation. Moreover, not all women menstruate, and amenorrhea (period cessation) is prevalent among female athletes (Verhoef et al. 2021). However, one can generalise that menstruation is one of the main differences between female and male bodies. As stated by Young (2005), menstruation marks girls and women as different from the normative and privileged male body.

Furthermore, in the case of women, there is more attention on leaking body boundaries (MacDonald 2007), as illustrated by physiological fluids, such as milk or menstrual blood. Although both fluids are natural, they are treated as abject and provoke reactions such as disgust (Kristeva 1982). A leaky body is read as a body that is out of control. On one hand, it is a question of body image. Women are expected to hide their bodies’ physiological aspects, including body hair, natural smells and menstruation. On the other hand, a woman is often treated as irrational, “controlled by their bodies” (Erchull 2013: 33), whose behaviours result from “emotional swings” related to the cycle phase and hormone levels. Consequently, the stigma of menstruation “marks women as ill, disabled, out-of-control, unfeminine, or even crazy” (Johnston-Robledo, Chrisler 2013: 10).

Numerous authors have described how menstrual taboos and stigma influence this female experience in different cultures, both today and in the past (see, e.g. Delaney, Lupton, Toth 1988; Merskin 1999; Johnston-Robledo, Chrisler 2013). In “the culture of concealment” (Houppert 1999), menstrual taboos and stigma cause women to feel shame in association with their period, which is accompanied by efforts to keep it invisible.

The imperative to conceal menstruation is reproduced through advertisements of hygiene products that guarantee discretion during “these days” (Houppert 1999; Johnston-Robledo, Chrisler 2013; Major 2018). Producers of sanitary pads or tampons guarantee that a woman can wear even tight and/or white clothes because the advertised products, invisible under clothes, will provide sufficient protection. They also claim that these products will cancel out physiological odours. The invisibility of menstrual blood is also reinforced by the use of blue liquid in advertisements instead of red to imitate blood (del Saz-Rubio, Pennock-Speck 2009; Przybylo, Fahs 2020).

As noted by Ussher (2006: 20), the menstruating body “must be subjected to the disciplinary practices of concealment and control”. Hygiene products are intended to assure women that their period will not be noticeable to others, as traces of menstrual blood on clothing are a source of shame and stigma. Therefore, “women go through great efforts to conceal their ‘menstruation’ status and prevent stigma-related ‘leakages’ from occurring” (van Lonkhuijzen, Garcia, Wagemakers 2023: 365).

Beyond invisibility, silence is the second key indicator of a “culture of concealment” (Delaney, Lupton, Toth 1988; Houppert 1999). Menstruation has been deemed unfit for public discussion, not even with relatives and friends (Houppert 1999; Johnston-Robledo, Chrisler 2013). Nowadays, however, the topic of menstruation is increasingly and more openly discussed in the public sphere, which will be described further; however, this does not mean that it has ceased being taboo. This is illustrated by the widespread use of euphemisms such as “time of the month”, “Aunt Flo”, “on the rag”, “shark week” (Chrisler 2011; Thornton 2013) or Polish “te dni” [these days], “trudne dni” [difficult days], “kobieca przypadłość” [female ailment] (Rode 2016; Major 2018) in advertising, social media and everyday conversations. According to MacDonald (2007: 347), “(…) the cultural message is clear: menstruation is not something we should speak of openly. We control menstruation, then, by clotting the flow of bloody words”.

Kissling noted that one could speak about three types of menstruation taboo in North America that appear to be common across Western culture, two of which – concealment and communication – have been mentioned above. The third taboo concerns activity. There has been a common belief that women must restrict physical activity during menstruation (Kissling 1996). Today, menstruation is less often presented in terms of an illness or pathological condition that prevents a woman from performing certain activities, including physical exercise. Moreover, hygiene products are advertised as freeing women from the restrictions imposed by the female body, allowing them to remain active (Rice 2014; Vostral 2008). Some of the advertisements present menstruating women as talking openly about their period and being strong and active despite it (see, for example, Sanofi’s ‘I have my period’ painkiller advertisement or Procter and Gamble CE’s sanitary pads advertisement). This change in the menstrual discourse, however, has evoked ambivalent reactions. On the one hand, it is perceived positively as breaking the frailty myth and liberating women from the (assumed) constraints imposed by a female body, but on the other hand, as forcing women to be active and in good condition, even when experiencing strong physical pain or feeling worse.[2]

In Poland, as the report Menstruation (2020) revealed, although menstruation is discussed more frequently in both public and private spheres than it used to be, it remains largely taboo. The dominant discourse about menstruation focuses on physiological elements, and the social perspective focusing on tension and emotions is niche. One-quarter of Polish women and teenagers perceive menstruation as a very negative experience, and the majority of women regard it as dirty and disgusting. During menstruation, many women feel socially isolated and excluded in their professional lives. Moreover, in many environments, there is no transfer of knowledge or experiences and no support; additionally, many stereotypes regarding menstruation are reproduced.

Although, as described above, menstruation remains taboo to some extent, and its disclosure can be a cause of social stigmatisation, it should be noted that the issue of menstruation is increasingly becoming a matter of public debate. The primary issues that are of interest to both researchers and non-governmental organisations are menstrual poverty (Bobel et al. 2020) and, to a much lesser extent, menstrual leave (see, e.g. Barnack-Tavlaris et al. 2019). In Poland, as the report Ubóstwo menstruacyjne w opiniach i doświadczeniach kobiet [Menstrual poverty in women’s opinions and experiences] (2021) states, the period exclusion is related not only to lack of access to hygiene products, lack of financial resources but also lack of appropriate education and maintaining taboos (see also: Menstruation 2020). Moreover, in schools, the issue of menstruation is discussed in classes with only girls, making it a “girl’s thing”.

Menstrual poverty may be considered within the framework of menstrual activism, which should, however, be understood more broadly. Menstrual activism addresses numerous social and political problems related to menstruation, such as its medicalisation, the toxic substances in menstrual products, the negative representation of menstruation in popular culture and menstrual education (Fahs 2016: 2, see also: Rode 2016). This activism takes different forms and styles, formal and informal, individual and collective and is expressed through art, political activities, media and educational campaigns, stories shared on social media, etc. In a Polish context, one should indicate the activities of the Różowa Skrzyneczka [Pink Box] Foundation, Akcja Menstruacja [Action Menstruation] Foundation, and Okresowa Koalicja [Periodic Coalition – an association of organisations, activists and experts], which fight against menstrual poverty by providing access to hygiene products to schools and those in need, break the taboos and educate about menstruation. Menstrual activism aims to increase consciousness about the social contexts of menstruation that engender the objectification of the female body and associated experiences of shame; it also aims to develop more positive representations of menstruation (Bobel 2010). Considering the subject matter of the article, it is worth noting that some professional female athletes have also been involved in social campaigns related to menstruation. For example, 50 of them have joined the #SayPeriod campaign to break the stigma regarding language related to periods (#SayPeriod: Hannah Miley discusses campaign urging people to break stigma on language around periods 2022).

Although professional sport do not exist in a social vacuum and female athletes’ perceptions and activities are shaped by the broader sociocultural context, the social sciences literature on menstruation and professional sport is scarce. Nevertheless, based on the literature review (including sport science), it is possible to distinguish three main themes being addressed.

First, the literature concerning menstruation in sport focuses on the effects of menstruation (or the menstrual cycle) on training and performance (see, e.g. Findlay et al. 2020; Solli et al. 2020; Meignié et al. 2021; Zawadzka, Grygorowicz 2023). Regarding this theme, it is essential to note that there is no expert consensus about the impact of menstruation on female athletes’ performance (Weaving 2017), and ‘there are still many questions with indefinitive answers’ (Brown, Knight, Forrest 2020: 2). Menstruation affects women differently, both within and outside of sport; therefore, it is crucial to adapt individual perspectives and analyse individual experiences and perceptions rather than measure group averages (Brown, Knight, Forrest 2020: 2). Sportswomen have rarely publicly addressed this topic; some have attributed their failure in competition to menstruation; conversely, others have broken world records despite menstruation (Weaving 2017). Moreover, despite the lack of clear evidence suggesting that menstruation negatively impacts women’s performance, some research findings have been used to maintain the frailty myth (Weaving 2017: 43). The scientists have also studied how athletic activity affects the menstrual cycle; however, this topic is beyond the scope of this article and will be not discussed further.

Second, considering the potential relevance of the menstrual cycle in relation to performance and the influence of sport careers on athletes’ health, it is not surprising that the second theme has been communication regarding this topic between athletes and their coaches, as well as between physicians and other staff. The results of the studies are not unanimous; however, the majority of them reveal that female athletes and coaches rarely communicate about menstruation and the menstrual cycle (see, e.g. Brown, Knight, Forrest 2020; Laske, Konjer, Meier 2022). Consequently, athletes do not adjust their training to the menstrual cycle (Laske, Konjer, Meier 2022); therefore, a lack of communication between athletes and coaches may impact sport performance (Brown, Knight, Forrest 2020). Amongst the most significant communication barriers, the previous studies indicated the following: (1) insufficient knowledge; (2) social norms related to the menstrual taboo and stigma that make conversations about menstruation embarrassing or awkward; (3) concerns about athletes’ privacy (Solli et al. 2020; Höök et al. 2021; Verhoef et al. 2021; Laske, Konjer, Meier 2022). The studies have also found that a lack of communication is more frequent in the cases of male coaches (Brown, Knight, Forrest 2020; Findlay et al. 2020; Solli et al. 2020; Laske, Konjer, Meier 2022), which is particularly important given that the vast majority of coaches in professional sport are men. Athletes are more willing to speak about their own menstrual cycle with female coaches (Findlay et al. 2020; Brown, Knight, Forrest 2021). However, the studies revealed that female coaches rely predominantly on personal experiences and lack professional education and knowledge (Höök et al. 2021; Laske, Konjer, Meier 2022).

The third theme that can be indicated concerns the media discourse. However, it should be noted that research concerning the media discourse around menstruation in sport remains sporadic. One such publication is Kissling’s (1999) article in which she analysed the sports pages of US newspapers for coverage of Uta Pipping’s victory (third in a row) in the 1996 Boston Marathon over her competitors and obstacles related to menstruation, such as menstrual cramps and heavy menstrual flow (and diarrhoea). Kissling (1999: 84) distinguished three news categories based on their handling of athlete menstruation: (1) complete omission of menstruation as the source of Pippig’s difficulties during the race, (2) explicit, nearly clinical coverage of menstruation and (3) the use of exaggeration and overemphasis on the “debilitating” effects of menstruation. According to the author, the first category maintains the menstruation taboo, while the second and third disregard it; however, the third also emphasises gender differences. Moreover, as Kissling (1999: 84) noted, “certain ideals of femininity have been both reinforced and undermined. Pippig’s ‘difference’, her status as female, is demonstrated by her visible menstruation, while her ‘unfeminine’ athletic prowess is emphasised by her victory”.

Another publication on this topic was written by Weaving (2017). The author, referring to Kissling’s (1999) article, stressed that Pippig’s body was portrayed as dysfunctional despite the German runner’s victory. The claims that the athlete should have withdrawn from the competition could also be linked to images of her leaking body (blood was running down her legs), which have no place in media coverage and the public space. Weaving (2017) also recalled media coverage of Heather Watson’s performance (British tennis player who attributed her loss in the first round of the Australian Open 2015 to “the girls’ things”), suggesting that using menstruation as an excuse for poor performance could reinforce the frailty myth and conviction that the female body, mainly during menstruation, is too frail for sport. However, it should be noted that Watson’s statements could have helped break the silence around menstruation.

Some authors have also mentioned the artist Kiran Gandhi, who ran the 2015 London Marathon while on her period without the protection of a tampon or pad, thereby engaging in ‘free bleeding’ (see, e.g. Weaving 2017; Bobel, Fahs 2020; Gottlieb 2020). However, this would appear to be encompassed within the topic of performance or activism rather than sport, highlighting a gap in the literature regarding this topic.

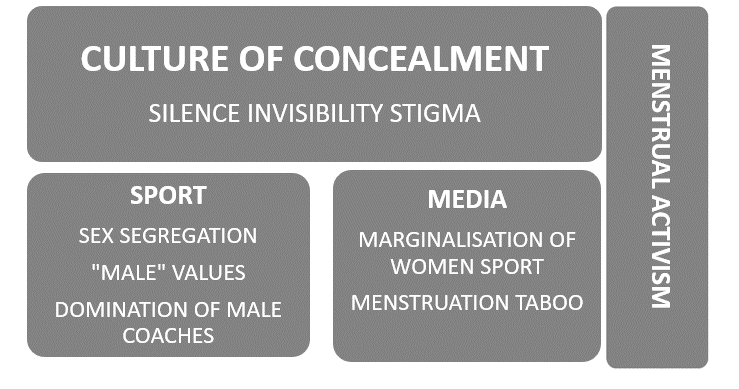

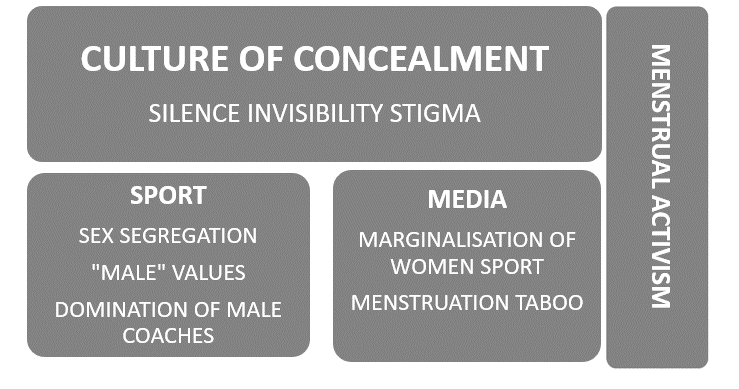

On the basis of the literature review and my previous investigations on women’s status in sport (Jakubowska 2014, 2015), I assume, which I would like to verify in further research, that the (in)visible status of menstruation in sport is shaped by four main factors: (1) the culture of concealment, (2) the specific nature of sport, (3) its media coverage, and (4) menstrual activism (Figure 1).

First, both sport and sport media are shaped by the broader sociocultural context. “The culture of concealment” (Houppert 1999) maintains menstrual taboo and stigma that may influence both communication with the coaches and the ways athletes present themselves in media. As women, female athletes have been socialized in a culture that has imposed silence and invisibility of menstruation. Female athletes have been taught that menstruation should remain something discreet and that the menstruating body should be controlled and disciplined. On the one hand, a leaking body can be a source of embarrassment; on the other hand, revealing a period can cause a woman to be perceived as driven by “emotional swings”, i.e. unprofessional. Consequently, despite knowing that the period can affect sport performance, some female athletes may not discuss the issue with their coaches. In this context, it should be repeated that the vast majority of coaches in professional sport are men, with whom conversations about menstruation are perceived as more embarrassing (Brown, Knight, Forrest 2020; Findlay et al. 2020). At the same time, female athletes may avoid communicating the issue of menstruation to a broader public, being aware that it remains taboo to a large extent.

Figure 1. The main factors shaping the status of menstruation in professional sport

Source: own elaboration

Second, the silence on the issue of menstruation may be due to the specific nature of the sport, which is sex segregation based on the dichotomy between male strength and female frailty (Dowling 2001). In this context, the concealment of menstruation, even if a woman suffers from some physical ailments, can be seen as breaking this myth. Outside of the field of sport, it has been revealed that women in China, for example, are hesitant to take menstrual leave because of fear that it will reinforce stereotypes of female fragility (Forster 2016). Revealing menstruation and the ailments associated with it could be seen as confirmation of a woman’s frailty. According to Schneider (2000: 132), coaches and decision-makers would perceive sportswomen’s bodies as “dysfunctional if they failed to function like male bodies.”

Disclosure of menstruation may evoke the aforementioned perception of menstruating women as out-of-control, ill and driven by emotions. The assumed lack of complete control over their own bodies and high susceptibility to emotions can undermine the image of women as “real” athletes who are expected to control their bodies and emotions (Dykzeul 2016: 8). Control and discipline over one’s own body, together with confidence in abilities and high-performance expectations, are key elements of an “athletic attitude” (Moreno-Black, Vallianatos 2005: 58–59). An athlete presenting this attitude is willing to continue performance despite pain or discomfort. For these athletes, menstrual ailments will be perceived as something that should be overcome and will not be used as an excuse for weaker performance, and disclosure of menstruation as contradictory to an “athletic attitude.” However, it should be noted that although pain is normalized in sport and is seen as part of “the prices of success,” it is also strongly related to masculinity. Visible pain, injuries, and blood confirm players’ masculinity, power, and sacrifice. Feminine menstrual pain should be masked, “rather than being a trophy, menstruation and menstrual pain are considered things to hide” (Moreno-Black, Vallianatos 2005: 62).

Third, the rare public statements by female athletes about menstruation can be linked, on the one hand, to the status of women’s sport in the media and, on the other hand, to the media taboo on menstruation described in the article’s first part. Women’s sport has been marginalised in media (Jakubowska 2015). Bearing in mind that the majority of sports fans are men, there is a concern that talking about menstruation will increase the marginalisation of women’s sport. Although athletes’ femininity is emphasized in media coverage, this happens when it fits into cultural ideals of femininity. These assume the disciplining of the female body and the concealing of those aspects of the body that remind us of its physiological nature, such as menstruation. Although there are other manifestations of body physiology in sport media coverage, such as sweating or whines (e.g. in tennis), they apply to both genders and may be perceived as a manifestation of the effort being made. Menstruation refers only to women’s sport (leaking woman’s body) and is not the result of a sport performance but rather an obstacle to its execution. Moreover, if menstrual blood is visible on screen, it would be a breaking of the principle of invisibility of menstruation in the media.

However, it should be noted that menstrual activism is gaining prominence, and public discourse on menstruation has encouraged some sport organisations to change the regulations and some female athletes to speak out on menstruation issues. For example, in 2022, the All England Club, Wimbledon’s organising body, changed their strict all-white dress code for the first time in the tournament’s nearly 150 years of history, thus allowing female players to wear dark-coloured undershorts as of 2023. In 2022 and 2023, the England women’s football team switched to blue shorts from white and some English football clubs, such as West Bromwich Albion and Manchester City, have transitioned to dark shorts for their female teams (Sheppard 2023). These changes were triggered by concerns raised by athletes about the possibility of staining clothing or leaking blood during menstruation. In the case of Wimbledon, they have also been supported by menstrual activists who protested during the tournament in 2022.

Moreover, some sportswomen have spoken openly about the influence of menstruation on their performance, which has attracted considerable media attention in the last few years. Amongst these are (1) the Chinese swimmer Fu Yuanhui, who attributed her weaker performance in the 4 × 100 m medley relay during the 2016 Rio Olympics to her period, which had started the previous day; (2) Israeli marathon runner Lonah Chemtai Salpeter, who was forced to pause her run during the 2020 (2021) Tokyo Olympic Games due to menstrual cramps; and (3) the Chinese player Qinwen Zheng, who attributed her loss against Iga Świątek in the fourth round of the French Open 2022 to ‘the girls’ things’. Therefore, one can say that although menstruation remains largely invisible in professional sport, the menstrual taboo is being broken as it happens in other areas of social life.

The current analyses of menstruation in professional sport derive mainly from sport science that rarely accounts for sociocultural factors. Meanwhile, perceptions of menstruation and communication regarding this issue are shaped not only by the characteristics of sport and being an athlete but also by a broader sociocultural context and being a woman (both inside and outside sport). The status of menstruation in this area can result not only from the broader context of ‘the culture of concealment’ but also from the status of women in professional sport. From this perspective, there is a concern that emphasising this exclusively female experience and its influence on performance will hinder women’s fight for equal status in the field of sport. For these reasons, menstruation in professional sport should also be analysed from a sociological perspective.

Challenging the culture of concealment and talking openly about menstruation creates the risk of returning to essentialist thinking. i.e. perception of gender differences as rooted in nature and biology. This issue requires in-depth research based on discourse analysis, amongst other things. Being aware of this risk, at the same time, I would argue for considering the body’s physicality in sociological research instead of treating the body solely as a social construct. Referring to Fingerson (2005), one can say that as sociologists, we should not only analyse ‘agency over the body’ but also the ‘agency of the body.’

Research on menstruation in sport can draw attention to the need to consider the specificity of the female body more in research. Most research from sport science has involved mainly male subjects (Mujika, Taipale 2019), a phenomenon which extends beyond sport science (Criado Perez 2019). An increase in the number of studies involving women, including as sole participants in research, could contribute to a better understanding of women’s physiology and sports performance and, consequently, perhaps help female athletes achieve better results. Regarding the social impact, the research on menstruation may contribute to better internal communications, the development of education regarding menstrual issues and institutional support for female athletes. Moreover, openly discussing menstruation by female athletes, who, as role models, impact girls worldwide, may help mitigate the menstruation taboo and stigma.

The article has been written based on a literature review and my previous investigations of women’s sport. I plan to conduct research on menstruation in professional sport, namely menstruation management (its dimensions related to everyday practices, communication and policy), as in my opinion, the analysis of this issue, in addition to the previously indicated application possibilities and social impact, may contribute to the development of three sociological subdisciplines: the sociology of sport, the sociology of the body and the sociology of gender, as well as (critical) menstruation studies.

Barnack-Tavlaris J.L., Hansen K., Levitt R.B., Reno M. (2019), Taking leave to bleed: Perceptions and attitudes toward menstrual leave policy, “Health Care for Women International”, vol. 40(12), pp. 1355–1373. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2019.1639709

Bobel C. (2010), New Blood: Third-Wave feminism and the politics of menstruation, Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick.

Bobel C., Fahs B. (2020), From bloodless respectability to radical menstrual embodiment: Shifting menstrual politics from private to public, “Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society”, vol. 45(4), pp. 955–983. https://doi.org/10.1086/707802

Bobel Ch., Winkler I.T., Fahs B., Hasson K.A., Kissling E.A., Roberts T.A. (eds.) (2020), The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies, Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore.

Brown N., Knigh C.J., Forrest L.J. (2020), Elite female athletes’ experiences and perceptions of the menstrual cycle on training and sport performance, “Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports”, vol. 31(1), pp. 52–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.13818

Chrisler J.C. (2011), Leaks, Lumps, and Lines: Stigma and Women’s Bodies, “Psychology of Women Quarterly”, vol. 35(2), pp. 202–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684310397698

Criado Perez S. (2019), Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed for Men, Chatto & Windus, London.

Del Saz-Rubio M.M., Pennock-Speck B. (2009), Constructing Female Identities Through Feminine Hygiene TV Commercials, “Journal of Pragmatics”, vol. 41(12), pp. 2535–2556. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2009.04.005

Delaney J., Lupton M., Toth E. (1988), The Curse: A Cultural History of Menstruation, University of Illinois Press, Chicago.

Dowling C. (2001), The Frailty Myth: Redefining The Physical Potential of Women and Girls, Random House, New York.

Dykzeul A.J. (2016), The Last Taboo in Sport: Menstruation in Female Adventure Racers, Master dissertation, Massey University Auckland, New Zealand.

Erchull M.J. (2013), Distancing through Objectification? Depictions of Women’s Bodies in Menstrual Product Advertisements, “Sex Roles”, vol. 68(1–2), pp. 32–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-0004-7

Fahs B. (2016), Out for Blood. Essays on Menstruation and Resistance, State University of New York Press, Albany, NY.

Findlay R.J., Macrae E.H.R., Whyte I.Y., Easton C., Forrest L.J. (2020), How the menstrual cycle and menstruation affect sporting performance: Experiences and perceptions of elite female rugby players, “British Journal of Sports Medicine”, vol. 54, pp. 1108–1113. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2019-101486

Fingerson L. (2005), Agency and the Body in Adolescent Menstrual Talk, “Childhood”, vol. 12(1), pp. 91–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/0907568205049894

Forster K. (2016), Chinese Province Grants Women Two Days ‘Period Leave’ a Month, “Independent”, August 18. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/asia/chinaperiod-leave-ningxia-womentwodays-a-month-menstruation-a7197921.html [accessed: 5.04.2023].

Gottlieb A. (2020), Menstrual Taboo: Moving Beyond the Curse, [in:] Bobel Ch., Winkler I.T., Fahs B., Hasson K.A., Kissling E.A., Roberts T.A. (eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies, pp. 143–162, Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore.

Höök M., Bergström M., Sæther S.A., McGawley K. (2021), “Do Elite Sport First, Get Your Period Back Later”. Are Barriers to Communication Hindering Female Athletes?, “International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health”, vol. 17/18(22): 12075. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182212075

Houppert K. (1999), The Curse: Confronting The Last Unmentionable Taboo, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, New York.

Jakubowska H. (2014), Gra ciałem. Praktyki i dyskursy różnicowanie płci w sporcie, Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, Warszawa.

Jakubowska H. (2015), Are women still the ‘other sex’: gender and sport in the Polish mass media, “Sport in Society”, vol. 18(2), pp. 168–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2013.854464

Johnston-Robledo I., Chrisler J.C. (2013), The Menstrual Mark: Menstruation as Social Stigma, “Sex Roles”, vol. 68, pp. 9–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-0052-z

Kissling E.A. (1999), When Being Female Isn’t Feminine: Uta Pippig and Menstrual Communication Taboo in Sports Journalism, “Sociology of Sport Journal”, vol. 16(2), pp. 79–91. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.16.2.79

Kristeva J. (1982), Powers of Horror: An Essay of Abjection, Columbia University Press, New York.

Laske H., Konjer M., Meier H.E. (2022), Menstruation and training – A quantitative study of (non-)communication about the menstrual cycle in German sports clubs, “International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching”, vol. 19(1), pp. 129–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/17479541221143061

MacDonald S.M. (2007), Leaky Performances: The Transformative Potential of Menstrual Leaks, “Women’s Studies in Communication”, vol. 30(3), pp. 340–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/07491409.2007.10162518

Major M. (2018), Z pewną taką nieśmiałością… O krwi menstruacyjnej w (neo)serialach dla dziewczyn i kobiet, [w:] Jachymek K., Major M. (eds.), Wydzieliny, pp. 183–203, Wydawnicwo Naukowe Katedra, Gdańsk.

Meignié A., Duclos M., Carling C., Orhant E., Provost P., Toussaint J., Antero J. (2021), The Effects of Menstrual Cycle Phase on Elite Athlete Performance: A Critical and Systematic Review, “Frontiers in Physiology”, vol. 12, pp. 1–10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2021.654585

Menstruation (2020), Report on quantitative and qualitative research conducted by research company Difference on behalf of the Kulczyk Foundation, Warsaw.

Merskin D. (1999), Adolescence, Advertising, and The Idea of Menstruation, “Sex Roles”, vol. 40, pp. 941–957. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1018881206965

Moreno-Black G., Vallianatos H. (2005), Young Women’s Experiences of Menstruation and Athletics, “Women’s Studies Quarterly”, vol. 33(1/2), pp. 50–67.

Mujika I., Tajpale R.S. (2019), Sport Science on Women, Women in Sport Science, “International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance”, vol. 14(8), pp. 1013–1014. https//doi.org.10.1123/ijspp.2019-0514

Przybylo E., Fahs B. (2020), Empowered Bleeders and Cranky Menstruators: Menstrual Positivity and the “Liberated” Era of New Menstrual Product Advertisement, [in:] Bobel Ch., Winkler I.T., Fahs B., Hasson K.A., Kissling E.A., Roberts T.A. (eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies, pp. 375–394, Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore.

Rice C. (2014), Becoming Women: The Embodied Self in Image Culture, The University of Toronto Press, Toronto.

Rode D. (2016), O kilku obliczach menstruacyjnego aktywizmu, “Civitas Hominibus”, vol. 11, pp. 123–135. https://doi.org/10.25312/2391-5145.11/2016_123-135

#SayPeriod: Hannah Miley discusses campaign urging people to break stigma on language around periods (2022), “Sky Sport”, October, 26. https://www.skysports.com/more-sports/swimming/news/29877/12729597/sayperiod-hannah-miley-discusses-campaign-urging-people-to-break-stigma-on-language-around-periods [accessed: 2.10.2023].

Schneider A.J. (2000), On The Definition of ‘Woman’ in The Sport Context, [in:] Tännsjö T., Tamburrini C. (eds.), Values in Sport: Elitism, Nationalism, Gender Equality, and the Scientific Manufacture of Winners, pp. 123–138, Taylor and Francis, London.

Sheppard E. (2023), Athletes and periods: how the sporting world is starting to smash taboos, “Positive.News”, March, 8. https://www.positive.news/society/athletes-and-periods-how-the-sporting-world-is-finally-starting-to-smash-taboos/ [accessed: 31.10.2023].

Solli G.S., Sandbakk S.B., Noordhof D.A., Ihalainen J.K., Sandbakk Ø. (2020), Changes in self-reported physical fitness, performance, and side effects across the phases of the menstrual cycle among competitive endurance athletes, “International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance”, vol. 15, pp. 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2019-0616

Thornton L.J. (2013), ‘Time of the Month’ on Twitter: Taboo, Stereotype and Bonding in a No-Holds-Barred Public Arena, “Sex Roles”, vol. 68, pp. 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-0041-2

Ubóstwo menstruacyjne w opiniach i doświadczeniach kobiet [Menstrual poverty in women’s opinions and experiences] (2021), Raport z projektu badawczego Fundacji “Różowa Skrzyneczka.” https://rozowaskrzyneczka.pl/badania/ [accessed: 30.04.2024].

Ussher J.M. (2006), Managing the Monstrous Feminine: Regulating the Reproductive Body, Routledge, London and New York.

Van Lonkhuijzen R.M., Garcia F.K., Wagemakers A. (2023), The Stigma Surrounding Menstruation: Attitudes and Practices Regarding Menstruation and Sexual Activity During Menstruation, “Women’s Reproductive Health”, vol. 10(3), pp. 364–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/23293691.2022.2124041

Verhoef S.J., Wielink M.C., Achterberg E.A., Bongers M.Y., Goossens S. (2021), Absence of Menstruation in Female Athletes: Why They Do Not Seek Help, “BMC Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabilitation”, vol. 13(1), 146. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13102-021-00372-3

Vostral S.L. (2008), Under Wraps: A History of Menstrual Hygiene Technology, Lexington Books, Lanham, MD.

Weaving Ch. (2017), Breaking Down the Myth and Curse of Women Athletes: Enough is Enough. Period, “Women in Sport and Physical Activity Journal”, vol. 25(1), pp. 43–49. https://doi.org/10.1123/wspaj.2016-0010

Young I.M. (2005) On Female Body Experience: “Throwing Like a Girl” and Other Essays, Oxford University Press, New York.

Zawadzka D., Grygorowicz M. (2023), The importance of the menstrual cycle in women’s sports – football players’ opinion, “Issues of Rehabilitation Orthopaedics Neurophysiology and Sport Promotion – IRONS”, vol. 43, pp. 19–30. DOI: 10.19271/IRONS-000187-2023-43

Abstrakt. Celem niniejszego artykułu jest opisanie, w oparciu o przegląd literatury, statusu menstruacji w sporcie profesjonalnym z perspektywy socjologicznej. W pierwszej części artykułu opisano szerszy kontekst społeczno-kulturowy, który kształtuje postrzeganie i doświadczanie menstruacji, a następnie dokonano przeglądu literatury poświęconej sportowi. W drugiej części omówiono główne czynniki kształtujące status menstruacji w sporcie profesjonalnym, tj. kulturę ukrywania, charakterystykę sportu, medialny przekaz sportu i aktywizm menstruacyjny. Jak wskazuje artykuł, współwystępowanie tych czynników powoduje, że z jednej strony menstruacja rzadko jest przedmiotem komunikacji, zwłaszcza tej skierowanej do szerszej publiczności, z drugiej zaś aktywizm menstruacyjny przyczynia się do pewnych zmian związanych z dress codem czy otwartą dyskusją na tematy menstruacyjne. W podsumowaniu podkreślono wartość socjologicznych badań nad menstruacją w sporcie, wskazując na znaczenie tego tematu w badaniach podstawowych i stosowanych oraz wpływ społeczny takich badań.

Słowa kluczowe: menstruacja, sport profesjonalny, socjologia, kultura ukrywania, menstruacyjny aktywizm.