https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5500-3749

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5500-3749

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2069-1032

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2069-1032

Abstract. In the work of Prof. Paweł Starosta, issues related to social capital have not only been discussed frequently but their various dimensions have also been dealt with. Social capital-related considerations, according to the authors of this article originally include the following issues: (i) a recognition of the predominance of associative functions of social capital over those that are of a generative nature, (ii) the attribution of particular importance to networks of cooperation, knowledge exchange and the benefits derived from individuals’ abilities to situate themselves in these networks; and (iii) the cardinal importance of the “institutional encasing” of social capital givenits quality and the specific quality of the social capital of the Polish Third Sector as the “capital of local leaders”. The aforesaid perception of social capital was the frame of reference for us to analyse the material collected for their research on the condition of the Third Sector in rural Poland. Starosta’s reflections on social capital were highly useful in considering the specific features of “civic rurality” in Poland: the advantages and disadvantages of leadership social capital, the paucity of network links inthe third sector in the rural areas of the country and finally, the discordance between a high sense of agency, on the one hand, and disillusionment emerging from the unfavourable environment concerning social activism in local communities, on the other.

Keywords: social capital, non-governmental organisations, local development, rural development.

Reflections on social capital constitute an important part of Professor Starosta’s multithreaded and multifaceted scientific output, in particular on social capital’s significance in local and regional development. He has devoted several articles, reviews, commentaries and polemics to the subject.

The issue of social capital appears in Starosta’s work in variousways, also indicating the direction of his reflections on thereal-life manifestations of this concept. These include theoretical reflections and research concerning the types of social capital, its components and functions, social networks and network social capital, cooperation capital, forms and the role of social trust and their role in development and the importance of helpfulness and fairness in development. These themes also manifest in his scholarly work on local development in the broadest sense.

Starosta’s theoretical reflections on social capital comprise inter alia, instructive and inspiring contemplationson the interrelationships between social capital (its quality and type) and citizens organisedinto associations. Here, on the one hand, we consider the influence of a certain type of social capital on the emergence, persistence (and form of persistence), mutual cooperation/competition and disintegration of NGOs. On the other hand, we consider the opposite relationship, where the quality of social capital is determined, inter alia, by the number and density of associations in a given area and the scale of involvement of individuals in their activities. We can also propose a third dimension to this relationship when existing social organisations are part of the institutional backbone through which social capital is deployed.

This article aims to apply Starosta’s reflections on social capital and related issues to the analysis of the condition of rural NGOs in Poland. A perspective of analysis was applied based on the two following key assumptions:

(i) the substantive relevance of Starosta’s reflections on social capital to the analysis of data collected during research on the rural third sector in Poland (Knieć, Marcysiak, Piszczek 2022)

(ii) the dearthof publications linking Starosta’s scientific attainments in the field of research on social capital and its derivatives to the analysis of the quality of civil society in the contemporary Polish countryside. As far as we are concerned, there is considerable cognitive potential resulting from linking Starosta’s theories concerning social capital, its structure and function, with attempts to understand the condition of rural social organisations.

This part of the article provides insight into the three types of interrelationships between social capital and civil society mentioned in the introduction to this paper. These are, in our opinion, Starosta’s most important theoretical achievements concerning social capital. The third part of this article illustrates their practical applicability to the analysis of the collected research material on the condition of rural NGOs in Poland.

We begin with principia issues, i.e. by the way the essence of social capital is understood in Starosta’s work. An extensive summary of Starosta’s reflections on social capital can be found in the article Social capital in the context of interaction, included in Social Problems. Persistence and variability in a dynamic reality (Starosta 2022). Herein, Starosta draws on his recomposition of the concept of social capital, based primarily on trust, norms of reciprocity, responsibility for others along withsubjectivity and interaction networks (including informal ones). Starosta proposes, “a fundamental factor in building social capital becomes the shared values and norms referred to as civic virtues” (Starosta 2022: 110), which can be reduced to norms of solidarity, tolerance and responsibility for others. Their natural alter ego becomes the ‘stowaway’ situation, where individuals and groups benefit from the altruism of others, remaining passive during the initiation and implementation stages of initiatives, and derivesocial, political and economic benefits if the initiatives succeed. The aforementioned ‘civic virtues’ enable the creation and persistence of “a system of institutions that form a specific structural context” (Starosta 2022: 110). Among them, NGOs should be singled out in the first place.

Particular attention was paid by Starosta to the network component of social capital or network social capital. In his paper titled The network component of social capital, published in 2013, in the monograph Nowy ład (English translation: New Order). It discussed the dynamics of social structures in modern societies (Starosta 2013). Starosta contends that in a situation of economic underdevelopment (at least in Polish conditions), social capital plays a secondary role in creating regional development prospects. This happens when the pressure of individualistic values and the promotion of competitionas a norm produce life strategies that are oriented towards the attainment of material goods and doing this rather alone as maintained by Robert Putnam in his famous book Bowling Alone (Putnam 1995). Analysing the results of his research on the importance of social networks (Starosta 2013, 2018), Starosta concludes that this importance is significant at the micro-social scale and secondary or tertiary for meso- and macro-structures. Accordingly, for him the presence of individuals in (mainly informal) networks is critical to their life chances. In particular, the ability to situate oneself in these networks (collegial, social, family, professional, etc.), i.e. in positions that help access key information is critical. That said, the size and quality of social networks do not translate into the economic position of the counties in which they are present. It is questionable whether or not this lack of connection is a derivative of the strong dominance of informal networks (social or family), which leads tothe low involvement of individuals in formal networks (civic associations, trade unions, etc.)?

Starosta observes an important and interesting relationship between the subjectivity of individuals and small local communities, on the one hand, and the level of development of social capital based on formal institutions (the de facto reference here is to bridging-type social capital), on the other. In general, social capital based on informal family and social relationships is not conducive to making a case for changing the world based on the structures, institutions and procedures available in a democratic system.[1] Conversely, social activity based on formal and semi-formal structures enables individuals and groups to go beyond the corset of familism or clannishness (Starosta 2022). However, an individual’s ability to situate themselves in good quality networks almost guarantees them career success and, in turn, significantly increases the likelihood of material success (Starosta 2013: 328). Starosta’s research in Poland’ Łódź region in 2012 led to another interesting conclusion: the network component of social capital present there mainly involves local leaders. In Poland, as interpreted by Starosta from the data obtained, there is a situation “where, in the conditions of an underdeveloped civil society at the level of the territorial collectivity, it is not so much the networks of residents as the networks of local leaders that are important” (Starosta 2013: 329). This social capital, built and based largely on the activity of local leaders, seems to be a resource that is solely at their disposal and only serves, as Starosta notes, the purpose of mutual empowerment of organisations instead of building capital of an associative nature. Do we have a specific type of sociological vacuum that separates the leaders and the unaffiliated ‘locals’? To what extent is this phenomenon, related to the problem of ‘activating the already active’ and ‘activating the already activated’, which is faced repeatedly in research on the Polish Third Sector? (Goszczyński et al. 2013). This is an extremely interesting issue that requires further empirical exploration. In the second part of this article, we will address it based on the data collected and analysedas part of the present research.

Starosta’s reflections on the social functions of social capital (and the lack of it) – generative, associative and creating certain types of collective order (Starosta 2022; Starosta et al. 2017) – are also interesting. The former shows the role of social capital as a form of social network asset multiplication. Accordingly, it is an element that raises the efficiency of group activities by enabling individuals and groups to do the following: (i) position themselves in value-added networks; (ii) consequently, reduce transaction costs (through, inter alia, ‘honour contracts’); and (iii) generate constructive competition. This ‘market’ approach towards understanding how social capital functions results, in Starosta’s view, fromthe fact that, for a long time, social capital has been treated as axiologically neutral, i.e. as something that can be used for all sorts of purposes, implicitly if need be – including purposes which may not be in line with the values of the society on the whole. As if in response to such a dictum, Starosta links the associative function of social capital to the identification of variables or indicators, whose existence and intensity will foster the realisation of a vision of development that is congruent with the overall values of the society. This apllies primarily about building civil society, based on social capital manifested in the ability to act collectively to achieve common goals. Starosta defines this potential as a commonly shared belief, subsequently transformed into a tendency that favours activities that favour the community, rather than those carried out while competing for resources. As stated elsewhere (Starosta 2018), this pro-community spirit, going by Piotr Sztompka’s theory concerning a culture of trust (Sztompka 2007), is most effectively stimulated (animated) and sustained through the institutional fabric – whether governmental, (more) local governmental or (most likely) non-governmental.

Finally, Starosta draws our attention to concepts of social capital whereby it is constructed from several elements, occurring in configurations, on which the balance of this capital depends, and this has a direct bearing on the type of collective order that obtains in a given community (Frykowski, Starosta 2008a). In this sense, social capital can be associative, pro-civic and pro-tolerant, but it cannot, under the right conditions, lead to amoral familism or the formation of communities that are highly integrated but hostile to their surroundings.

In Starosta’s opinion, the consideration of the functions of social capital brings with it significant theoretical controversy, the discussion of which convinces him that the ‘dark sides’ of social capital (amoral familism, clannishness andexclusivity of groups) do not constitute its essence; they are like its ‘disease mutations’. To point to their equivalence, given their associative nature, is an oversimplification.

On the other hand, as mentioned above, caution in estimating the importance of social capital in stimulating socio-economic development is recommended. For Starosta, this importance is limited, usually secondary or tertiary, because “social capital cannot and does not replace modern technologies that facilitate the satisfaction of social needs and improve the quality of life, whether they operate in a more or less integrated society” (Starosta 2022: 115). In the process, he draws, inter alia, on his research on the links between the strength of social networks and the level of economic development of a commune (Starosta 2013), describing this phenomenon more broadly from an international comparative perspective in articles from 2016 (Ambroziak, Starosta, Sztaudynger 2016) to 2022 (Sztaudynger, Ambroziak, Starosta 2022). They conclude that, first, the strength of the social networks studied in the Łódź region is not considerable: these networks are small (few, spatially limited); however, the intellectual capital present in them is quite significant. Second, the network dimension of capital does not, however, translate into the economic position of the poviat (county).[2] However, as mentioned earlier, the establishment of an individual in good quality social networks all but guarantees professional and economic success. A broader perspective, however, leads us to somewhat different conclusions – a comparative analysis based on data from 22 European countries shows that the growth of the so-called cooperation capital can account for as much as 1/6th to 1/8th of economic growth, as measured in GDP terms. Starosta also points to a clear relationship between types of social capital and patterns of civic participation even as he proposesan interesting, multidimensional template for a methodology to measure the quality (strength?) of social capital (Starosta, Frykowski 2008b).

To conclude, Starosta’s reflections on social capital are highly relevant for analysing the condition of contemporary rural NGOs in Poland, in particular by applying the following considerations to the analysis:

(i) recognising the predominance of associative functions of social capital over generative ones. This concerns Starosta’s belief in the superiority of the pro-collectivist (communitarian) role of social capital (the ability and willingness to work together for the common good) as opposed to discounting it for economic (macro) or career (micro) benefits;

(ii) accepting the importance of ‘institutional encasing’ of social capital (in the form of both governmental institutions (local and central) and social organisations, formal/semi-formal associations, etc.), through which this capital is more effectively strengthened (and animated);

(iii) recognising the values and norms known as ‘civic virtues’ as the foundation of social capital: solidarity, cooperativism, tolerance and responsibility towards others;

(iv) accepting the value of networking and knowledge exchange, as well as the benefits of individuals’ ability to situate themselves in these networks. This also applies to the benefits that accrue to the individuals who associate with social organisations, including those at the local level;

(v) drawing attention to the emerging specificity of third sector social capital as ‘local leaders’ capital’, i.e. social capital built, sustained and developed by the elected members of organisations that represent community interests (which, in Poland, is more often the case).

In 2021, we conducted a study of rural NGOs through questionnaire-based interviews and focus groups with the leaders of these organisations. We have provided the details of the methodology in the article Citizenship on the periphery. The condition of rural NGOs as perceived by their leaders (Knieć, Marcysiak, Piszczek 2021). For this article, we limited ourselves to signalling a few key issues related to the methodology. We applied multistage sampling for determining the questionnaire survey respondents. Poland’s administrative divisions comprise voivodeships and poviats. We focused on rural poviats (drawing in turn voivodeships, rural poviats and NGOs). We encountered a serious problem concerning the disregard by the poviat offices fortheir obligation to publish a list of NGOs operating in their area. Moreover, we used the existing database at the disposal of the Forum for Rural Areas Activation (FAOW) in the draw, which included 1,120 rural NGOs. We consider asample of 333 rural NGOs in Poland.[4] Our interviewees were individuals representing the drawn NGOs (usually presidents, directors, orchairpersons).

Our respondents were mostly females with secondary and higher education, who usually represented Local Action Groups (LAGs), Farmers’ Wives Associations (FWAs) or foundations. Men most often represented associations. The average duration of activity of our respondents in a given organisation was five years.

The qualitative part of the study consisted of focus groups, with representatives of different types of NGOs countrywide. We conducted four such interviews with a total of 37 leaders of rural organisations.

Important changes were necessitated in the planned survey methodology due to the sanitary restrictions imposed by the Polish authorities following the COVID-19 pandemic (2021). We avoided the risky and much-discussed solution of conducting the survey face-to-face (questionnaire interviews were conducted over the phone and focus groups online). We were concerned mainly about problems with refusals, the length/comprehensiveness of the questionnaire (in which we also included many (semi-)open-ended questions or the comfort/freedom of the focus interviews in the online Teams version. The risk we took provedrewarding, with the pandemic, which had been present for some time, having changed our style of working and communication very much, resulting in complete freedom to talk online or on the phone. They were so natural to our respondents that we were surprisedat some of the responses when we suggested that perhaps (if the restrictions were lifted), we could meet at ‘traditional’ focus groups. There were comments such as “Why waste time getting there?” and “Let’s meet online, it’s more convenient that way, and it doesn’t change anything in the conversation”. Moreover, during these meetings, there was a kind of savoir vivre – quite obvious to everyone – e.g. muting microphones, not interrupting others, a special place for the interview (no third parties/interference/noise), etc. Apart from one case of a respondent temporarily ‘dropping out’ of the interview because of connection problems, we did not observe any technical disturbances (despite most of our respondents beingin the countryside homes at the time). As mentioned, the limited format of this article prevented us from presenting all the details of the methodology or the demographics of our respondents. Those interested may peruse other publications produced using the study described here.

In presenting the selected analyses, we are aware of the limitations of the questionnaire design/content of the questions, andthose of the focus interview. As we followed Starosta’s analysis of social capital, we came acrossissues that were of particular interest to us. These issues were coveredin our study, and they relate to the following:

(i) the broadly understood cooperation of NGOs with the social environment (unfortunately, we did not study the issue of trust – one of the key issues in Starosta’s capital analyses. The aspectof social trust was not addressed in the theme of the study, although we are aware of its relevance. We focused on the following aspects recognised by Starosta as being of particular importance to us: capacity building for bottom-up actions, legitimisation of non-profit activities, socialisation and cooperation);

(ii) the condition of the leaders of the analysed NGOs (this is all the more important as, once again, Polish rural and small-town NGOs seem to be ‘leaders’); and

(iii) leaders’ assessment of the ‘climate’ for NGO activities in Poland from a local (village, commune) and national perspective.

In our survey, we inquired about cooperation with entrepreneurs, local authorities (commune authorities andcommune units) and ‘supra-local’ authorities (poviat andmarshal’s office), or other social organisations. The ‘cooperation rating index’ created, based on these variables, could take values from a minimum of 4 points (worst rating) to a maximum of 20 (best rating). On average, leaders awarded cooperation in the social environment 16 points, which we think is a high score.

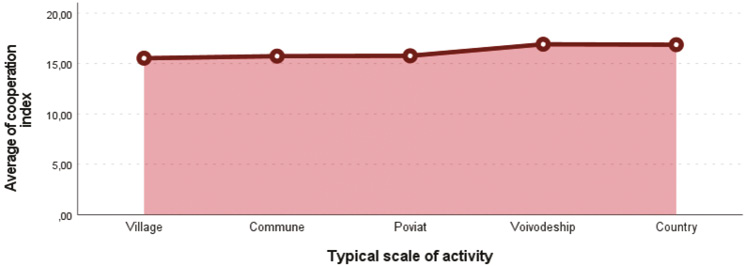

Of interest to us was whether and to what extent the ‘cooperation’ thus defined is related to the typical field of action. It is found that, on average, it manifests itself best in rural NGOs operating on the voivodeship and national levels. The differences are small at approximately 17 points in these areas of operation, compared to 15 points at the village, commune and poviat levels.[5]

Chart 1. Averages of the ‘cooperation’ index by area of operation of the surveyed NGOs

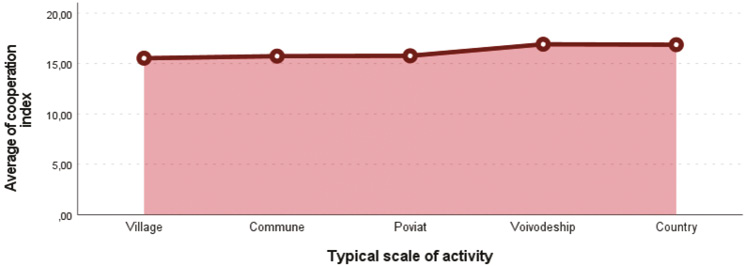

Notably, ‘cooperation’, broken down into its components, already presents a somewhat different picture, compared to a typical NGO area. On average, each type of cooperation we studied performs slightly worse among locally active NGOs (Chart 2). Particularly outstanding here was the poor assessment of ‘cooperation with entrepreneurs’, despite the significantand systematically increasing share of entrepreneurs in the ‘most active members’ of the surveyed organisations (Knieć, Marcysiak, Piszczek 2021: 56–57). Interestingly, we recorded the lowest average rating for ‘cooperation with the commune and commune units’ among rural NGOs. In contrast, cooperation with ‘other local government units’ (at poviat and marshal’s office level), scores the lowest among NGOs operating at the commune level. ‘Cooperation with other social organisations’ received the closest and highest marks in all areas of operation. Thus, the surveyed leaders were generally highly satisfied with the cooperation of their organisation (recall that, out of a maximum of 20 points, the average score for satisfaction was 16); however, satisfaction with the cooperation of individual ‘partners’ already falls differently, depending on the declared typical area of activity.

Chart 2. Mean scores for cooperation with different entities by declared area of NGO activity

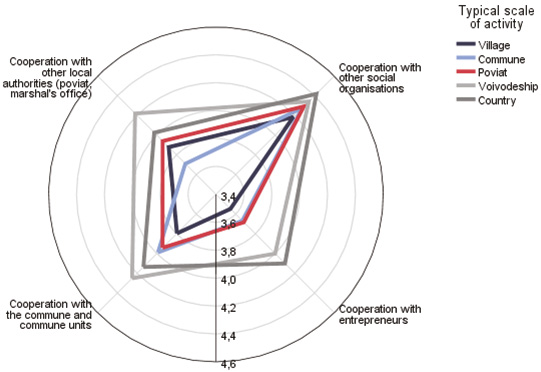

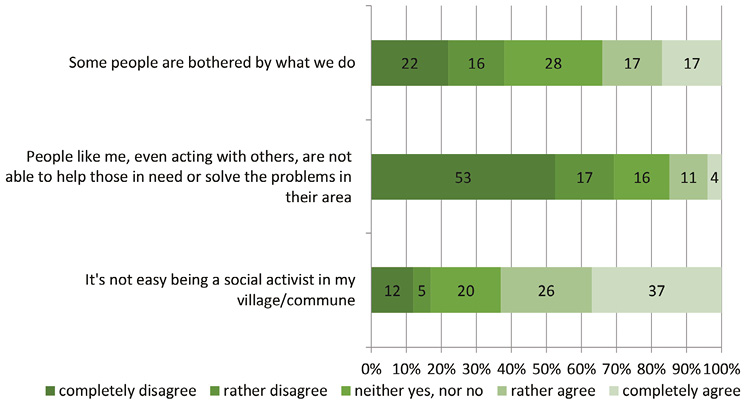

Another issue of interest was the condition of the leaders (feelings about the local environment’s perception and assessment of its activities). They admit that despite feeling that they are ‘doing something good’, and ‘appreciated in their community’, they are convinced that ‘being a social activist is difficult’ (Chart 3).

Chart 3. ‘Condition’ of the leader in the local environment (%)

Besides the aforesaid opinions (Chart 3), we have included others,[6] creating a so-called ‘sense of agency index’. Its maximum score is 35 (indicating a high sense of agency), and the minimum is 7 (very poor assessment of sense of agency). As revealed by the analyses, the average sense of agency, like the median, was 26 points. The minimum score of our respondents is 16 points and the maximum is 35. We can therefore consider this a rather positive result and the sentiment among leaders too as positive. The results of the analyses of the open-ended questions, or the statements obtained during the focus groups, contrast somewhat with these assessments. Comments on fatigue, overburdening of leaders, discouragement, the gap between the expectations of the environment and the actions taken, lack of support, etc. are highlighted. Finances, project settlement and related bureaucracy remain the most sensitive issues most negatively assessed by respondents (Knieć, Marcysiak, Piszczek 2021, 2022). In most of the studies after 1989, these issues are commonly identified as the crucial and typical problems of contemporary rural social organisations in Poland (Herbst 2008; Chrzczonowicz 2019; Charycka, Gumkowska, Bednarek 2021; Goszczyński, Knieć 2022). Besides these seemingly obvious facts, we would also like to draw attention to other somewhat less frequently mentioned issues. These relate to statements concerning the open question about the ‘biggest issues/problems’. These were answered by all respondents. Let us reiterate that the opinions cited here were not prompted by the researchers. We, therefore, treat them as reliable (strong) indicators of existing problems, particularly relevant in social capital analyses. Of course, it is difficult to make a strong statistical analysis in this case; we have, however, counted the responses (giving their percentage vis-à-vis the 333 leader comments), which we have assigned to the following types of problem points:

Type 1: Local community (89 indications [approximately 27%]). We deal mainly with ‘lack of interest from the public’, ‘lack of activity of the residents’ (also described as weakening, passivity, dependent on remuneration ‘scarce financial capabilities – everything is voluntary – this does not mobilise the residents’, ‘lack of volunteers’. ‘lack of interest of younger people (in a more formalised form of cooperation’, ‘The society is closed; it is hard to rebuild social relations’, ‘Sometimes it is difficult to get people out of their homes, and then they still complain that nothing is happening’. Particularly clear and frequent is the complaint about the inactivity of youth, ‘Young people do not want to be socially active. She retreated into those mobile phones, the Internet. Worst of all, however, they don’t want to contribute; for them, it feels strange (to do so)’.

Type 2: Organisation’s staff problems (38 indications [approximately 11%]).These are mainly related to the reluctance of people to engage. Leaders emphasise that even when an organisation looks large (formally), in practice, ‘everything is done by one person, or as they say: a bricklayer, a plasterer, an acrobat. So, one runs events, raises funds and accounts for them while activating the others. In the long run, it’s hard to stand like a locomotive engine that has no support’. Leaders explicitly indicated that they are bothered about ‘professional burnout of leaders’, ‘limited time’, ‘lack of support among the members of the organisation in fundraising, documentation (all work ceded to one person), including problems with division of tasks, lack of time for activities, and difficulty in getting a larger group together’. There are also times when, for example, the illness of a leader causes the organisation to ‘wither’ away completely.

Type 3: Cooperation with commune/administration offices (33 indications [approximately 10%). The most prominent resonance here was ‘lack of cooperation with the commune’, ‘blocking (of) initiatives’. Respondents stressed the importance of connections, in the absence of which it is impossible to securefunding for projects. ‘We are not waiting for money to fall from the sky. We take part in competitions, but we feel that you have to be a parish to win competitions. We know we write good projects because (right) from school we have been writing and winning). (...) the same people write for the association, and we are continually refused’, ‘Cronyism: you have to do everything via connections, ... (even)... (for)public (interest) activities. In competitions, projects from the (centre of) decision-making...next to Poznań, also win. And the farther away they are, at the edge of the voivodeship, they are ignored’.

Type 4: Cooperation with other organisations (8 indications [approximately 2%]). Leaders here principally mentioned competition for (financial) resources and lack of assistance/support from other institutions ‘Local support group – we have a very bad experience with help, not even a support organisation that should be helping’, ‘Appears as though resources are being diverted; a lot of competition, competition with other organisations for funds, lack of tools to work with business’, ‘competitionwith the village representative’.

The aforementioned types communicate problems concerning both the ‘condition of the leader’ and their (even more than the leader’s organisation), skills and ability to cooperate. We, therefore, tested whether these two issues somehow coexist, using the already mentioned ‘sense of agency index’[7] and the ‘cooperation index’. The relationship between these variables was found to be statistically significant, but not very strong. Leaders with a higher sense of agency assign a better rating for an NGO’s ‘cooperation’, while those with a lower sense of agency offer a worse rating.[8]

Generally, the surveyed leaders are convinced of their (the respective NGO’s) positive impact on the activity of the inhabitants (confirmed by 75% of respondents, including 35% who even describe it as very positive). If we juxtapose this issue with the assessment by the NGO leaders of the ‘activity-inactivity’ atmosphere characterising the localities in which they are active, we find that the higher the activity of the inhabitants, the more positive the impact of the NGO is assessed to be (this is not a strong relationship, but statistically significant[9]). Further, a statistically significant correlation was obtained when examining the impact on residents’ activityvis-à-vis their (residents’) ‘(non)compliance- quarrelsomeness’. However, it is weaker than ‘activity-passivity’.[10] That is to say, the more ‘quarrelsome, discordant’ the environments in which the NGOs in question operate, the weaker their impact on resident activism is judged by their leaders-to-be.

The environment in which NGOs operate is, of course, not only local authorities or the local community; it is also the ‘environment’ created by state policy, understood as legal regulations, administrative support, or simply as the state’s attitude towards NGOs. In Tables 1, 2, and 3 below, we have juxtaposed selected issues/opinions/assessments of various (often already mentioned in this article) issues related to NGO activities, with an assessment of the ‘climate’ for conducting social activities in a commune, or in Poland in general. The numerical values in the table cells are calculated using Spearman’s ρ. We have noted statistically significant correlations in these locations and have ranked them in descending order of the points scored in the ‘climate in the commune’ column.

| Evaluation of the NGO’s selected aspects as perceived by its leader (From 1 point [Very negative] to 5 points [Very positive]) |

Better climate for social activities in the commune (From 1 point [change is not important, irrelevant] to 5 points [change is absolutely necessary]) |

Better climate for social activities in Poland in general (From 1 point [change is not important, irrelevant] to 5 points [change is absolutely necessary]) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Cooperation with the commune and commune units | –0.4 | –0.17 |

| Cooperation with other local authorities (poviat, marshal’s office) | –0.2 | Irrelevant |

| Influence on the activities of the villagers | –0.2 | Irrelevant |

| Cooperation with other social organisations | –0.16 | Irrelevant |

| Cooperation with entrepreneurs | –0.16 | Irrelevant |

| Fundraising for the organisation | –0.16 | Irrelevant |

| Attracting new members | –0.15 | Irrelevant |

| Financial situation of the organisation | –0.15 | Irrelevant |

| State attitude towards NGOs | Irrelevant | –0.3 |

| Dealing with ‘bureaucracy’ in running the organisation | Irrelevant | Irrelevant |

| NGO leader’s opinions about selected aspects of their organisation’s performance (From 1 point [Completely disagree] to 5 points [Completely agree]) |

Better climate for social activities in the commune (From 1 point [Change is not important, irrelevant] to 5 points [Change is absolutely necessary]) |

Better climate for social activities in Poland in general (From 1 point [Change is not important, irrelevant] to 5 points [Change is absolutely necessary]) |

|---|---|---|

| It’s not easy being a social activist in my village/commune | 0.25 | Irrelevant |

| Some people are bothered by what we do | 0.2 | Irrelevant |

| Theorganisation is appreciated for what it does | –0.15 | Irrelevant |

| Social organisations like the one we are a part ofwill develop in the future | 0.14 | Irrelevant |

| The organisation is doing something good | 0.11 | 0.23 |

| People like me, even acting with others, are not able to help those in need or solve the problems in their area | Irrelevant | Irrelevant |

| The organisaton will get more members | Irrelevant | Irrelevant |

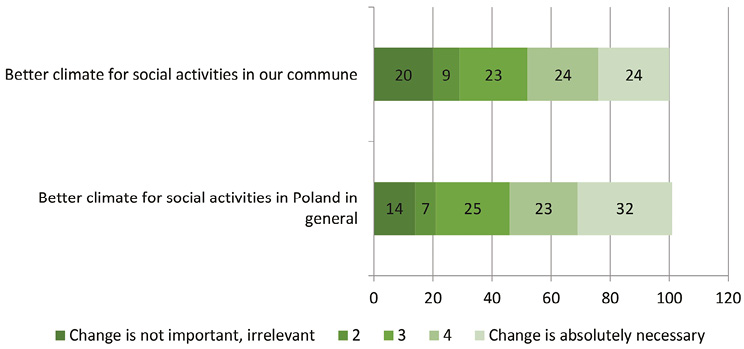

It is clear that the ‘local climate for action’ is more important (and statistically significant) for the functioning of rural NGOs than the ‘national climate’. Incidentally, we should add that the ‘action climate’ both in the commune and in Poland is not rated the best (Chart 4).

Chart 4. Assessment of the necessity of a change of climate concerning the operation of surveyed NGOs in the commune and Poland in general (%)

The ‘local climate’ correlates most strongly with the assessment of cooperation at the commune, poviat and voivodeship levels alike; the stronger the opinion that the climate for activity in the commune needs to change (for the better), the worse is the assessment of cooperation with local government units/offices. It can also be observed that the more this change in the local climate (for the better) is necessary (according to the leader), the worse is the evaluation of the impact of his/her/their organisation on the activity of the villagers. The more the need felt for such change, the more the leaders agree that people are not happy with their work, and the more they think it is not easy to be a social activist.

| Indexes | Better climate for social activities in our commune | Better climate for social activities in Poland in general |

|---|---|---|

| Index of cooperation | –0.33 | Irrelevant |

| Sense of agency index | –0.15 | Irrelevant |

In conclusion, we revert to the ‘cooperation’ and ‘sense of agency’ indices. Again, it can be seen that ‘local climate’ is crucial for the rural NGOs’ activities, with a stronger correlation with ‘cooperation’ than ‘sense of agency’ (Table 3). This is because even when unfavourable conditions for national action arise, rural NGOs can cope by mobilising not only ‘formal’ resources but also ‘informal’ ones because, as the data shows, they usually do not have large budgets, and their scope of action is local. They are, hence, able to adapt, or to use a biological term, to form into an ‘endospore’. This does not mean, of course, that the policy of a government is indifferent to rural NGO leaders. What is evident from the statements of these NGO leaders is their fear of centralisation and their general lack of trust in NGOs on the part of the powers that be.

This is best described by the following statements of the interviewees: ‘We are being treated like thieves’, ‘There are two perspectives from which I observe this. The first is the local perspective, i.e. the commune and the poviat, and here I have to say that I can’t particularly complain. The old rule of thumb is that if you can’t help, at least don’t make it harder, and somehow that’s the climate in which things are going on here. The broader, national perspective, on the other hand, seems to me to be a little worse because there is a very visible attempt to centralise decisions, which is reminiscent of time passed. We have developed a certain self-government model in Poland, which consists of giving decision-making powers as low as possible, including in the areas of operations of NGOs. Now, there is an increasing move towards centralisation, where only a legitimate and competent Areopagus (a council of elders) of different people will make decisions for me – although I hope it won’t come to that’.

In summary, the optics proposed in Paweł Starosta’s work for perceiving the structure and function of social capital have worked very well in analysing the condition of the rural Third Sector in Poland. Firstly, by using it, we have shown the importance of the associative nature of social capital for the smooth operation of NGOs. Relationships between social organisations and their surroundings – those further afield and those closer to them – do not always prove sustainable and important; so, a significant proportion of organisations has a minimal reach and scale of impact (a single village, 1–2 initiatives per year). This also brought up the subject of the difficult cooperation between NGOs and local authorities, which one respondent put simplyas follows: ‘They help because they don’t make it harder’. Secondly, we empirically confirmed the conclusions of Starosta’s research on the ‘leadership type of social capital’ in Poland. The leaders of the organisations we studied see this model more as an institutional threat and individual burden than as a desirable and functional direction for the activities of ‘their’ associations. Ultimately, we revealed a kind of split ego of local leaders balancing a high sense of agency and satisfaction with implemented activities and a relatively unfavourable climate for social action in the Polish countryside.

Ambroziak E., Starosta P., Sztaudynger J. (2016), Trust, helpfulness, and fairness and economic growth in Europe, “Ekonomista”, issue 5, pp. 647–673.

Charycka B., Gumkowska M., Bednarek J. (2021), The capacity of NGOs in Poland, Klon/Jawor.

Chrzczonowicz M. (2019), The non-governmental sector in Poland. Brief overview, active citizens fund, https://aktywniobywatele-regionalny.org.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/M_Chrzczonowicz_The_NGO_sector_in_Poland_ENG.pdf

Frykowski M., Starosta P. (2008), Kapitał społeczny i jego użytkownicy, “Przegląd Socjologiczny”, vol. 57, pp. 31–62.

Goszczyński W., Knieć W., Czachowski H. (2015), Lokalne horyzonty zdarzeń. Lokalność i kapitał społeczny w kulturze (nie)ufności na przykładzie wsi kujawsko-pomorskiej, Wydawnictwo Muzeum Etnograficznego w Toruniu.

Goszczyński W., Knieć W., Obracht-Prondzyński C. (2013), Kapitał społeczny wsi pomorskiej, Wydawnictwo Kaszubskiego Uniwersytetu Ludowego.

Herbst J. (2008), Wieś Obywatelska (Civic Rural Areas), [in:] J. Wilkin, I. Nurzynska (eds.) Rural Poland 2008. FDPA report on rural situation, FDPA, Warsaw.

Knieć W., Goszczyński W. (2022), Local horizons of governance. Social conditions for good governance in rural development in Poland, “European Countryside”, vol. 14, no. 1. https://doi.org/10.2478/euco-2022-0002

Knieć W., Marcysiak T., Piszczek E. (2022), Obywatelskość na peryferiach. Kondycja wiejskich organizacji pozarządowych w Polsce, Adam Marszałek, Toruń.

Knieć W., Marcysiak T., Piszczek E. (2022), Wiejskie organizacje pozarządowe w Polsce w czasie pandemii COVID-19, “Trzeci Sektor”, vol. 58.

Putnam R.D. (1995), Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital, “Journal of Democracy”, vol. 6(1), pp. 65–78. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.1995.0002

Starosta P. (2013), Sieciowy komponent kapitału społecznego, [in:] J. Grotowska-Leder, E. Rokicka (eds.), Nowy ład? Dynamika struktur społecznych we współczesnych społeczeństwach. Księga pamiątkowa poświęcona Profesor Wielisławie Warzywodzie-Kruszyńskiej z okazji 45-lecia pracy naukowej i dydaktycznej, Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego, Łódź, pp. 289–331. https://doi.org/10.18778/7525-967-4.18

Starosta P. (2018), Społeczny potencjał odrodzenia miast poprzemysłowych, Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego, Łódź.

Starosta P. (2022), Kapitał społeczny w kontekście współdziałania, [in:] A. Kacprzak, M. Gońda, I. Kudlińska-Chróścicka (eds.), Problemy społeczne. Trwałość i zmienność w dynamicznej rzeczywistości. Księga jubileuszowa z okazji 45-lecia pracy naukowej i dydaktycznej Profesor Jolanty Grotowskiej-Leder, Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego, Łódź, pp. 93–120. https://doi.org/10.18778/8220-767-5.07

Starosta P., Frykowski M. (2008b), Typy kapitału społecznego i wzory partycypacji obywatelskiej w wiejskich gminach centralnej Polski, [in:] M. Szczepański, K. Bierwiaczonek, T. Nawrocki (eds.), Human and social capital and region competitiveness, Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego, Katowice.

Starosta P., Brzeziński K., Stolbov V. (2017), The structure of social trust in post-industrial cities of Central and Eastern Europe, January, issue 12, pp. 79–88.

Sztaudynger J., Ambroziak E., Starosta P. (2022), Generalized trust, helpfulness, fairness and growth in European countries. A revised analysis, “Comparative Economic Research”, vol. 25, issue 3, pp. 135–160. https://doi.org/10.18778/1508-2008.25.25

Sztompka P. (2007), Zaufanie. Fundament społeczeństwa, Wydawnictwo ZNAK, Kraków.

Abstrakt. W twórczości naukowej prof. Pawła Starosty problematyka związana z kapitałem społecznym występuje często i w sposób wielowymiarowy. Oryginalność rozważań nad kapitałem społecznym według autorów niniejszej publikacji obejmuje następujące kwestie: uznanie przewagi asocjacyjnych funkcji kapitału społecznego nad tymi o charakterze generatywnym, przyznanie szczególnej ważności sieciom współpracy, wymiany wiedzy oraz korzyści płynących z umiejętności jednostek do sytuowania się w tych sieciach, wreszcie – kardynalne znaczenie „obudowy instytucjonalnej” kapitału społecznego dla jego jakości oraz zwrócenie uwagi na specyfikę kapitału społecznego polskiego Trzeciego Sektora jako „kapitału lokalnych liderów”. Autorzy postanowili wykorzystać tak zarysowaną optykę postrzegania kapitału społecznego do analizy zebranego przez siebie materiału z badań nad kondycją Trzeciego Sektora na terenach wiejskich Polski. Stwierdzono wysoką przydatność rozważań Pawła Starosty nad kapitałem społecznym do wyjaśniania specyficznych cech „obywatelskiej wiejskości” w Polsce: zaletami i wadami liderskiego kapitału społecznego, niedostatkiem powiązań sieciowych wiejskiego Trzeciego Sektora, wreszcie – zderzania się wysokiego poziomu poczucia sprawstwa z rozczarowaniem niekorzystnym klimatem wokół aktywności społecznej w środowiskach lokalnych.

Słowa kluczowe: kapitał społeczny, organizacje pozarządowe, rozwój lokalny, rozwój obszarów wiejskich.