https://orcid.org/0009-0006-4337-037X

https://orcid.org/0009-0006-4337-037X

Abstract. The article presents the results of a survey on the knowledge and experience of Polish women in the area of menstrual poverty. The article raises issues such as: respondents’ knowledge of the symptoms of menstrual poverty, characteristics of groups particularly vulnerable to deprivation in terms of menstrual health and hygiene, as well as the impact of menstrual poverty on the lives of people experiencing it. The survey raises the issue of tabooing and mythicizing the topic of menstruation. Respondents were also asked about initiatives to combat menstrual poverty. The respondents’ experience of menstrual poverty was also a key theme in the survey. The results of the survey indicate that menstrual poverty is an invisible and embarrassing subject, especially in Polish society. It is therefore essential to introduce into the public discourse an uninhibited debate on the psychosocial difficulties related to menstruation.

Keywords: period poverty, menstrual exclusion, menstruation, health and hygiene, taboo, mythization.

Meeting basic physiological needs is an essential foundation for health and well-being. Being able to take care of hygiene, including menstrual hygiene, remains an important condition for the psychosocial well-being of menstruating people (Cardoso et al. 2021: 1). It is estimated that the global population of menstruating people is now almost 2 billion people. Despite this, menstrual discourse remains socially and media tabooed (Kulczyk Foundation 2022: 5). World Bank data indicate that at least 500 million menstruating people face symptoms of menstrual poverty on a daily basis (World Bank 2018). According to the Central Statistical Office, 51.7 per cent of the Polish population is female (CSO 2020 after Kopiec 2020), but despite this, no systemic action is being taken to investigate the real risk of menstrual poverty.

Menstrual poverty (inability to meet menstrual health and hygiene, MHH) is defined primarily as a lack of access to menstrual hygiene products that is due to economic reasons. The World Health Organisation and UNICEF expand the definition of menstrual poverty to include elements such as the presence of obstacles to the ability to freely and safely exchange and dispose of used menstrual materials. Menstrual poverty also includes sanitary barriers to cleanliness and comfort, as well as constraints related to menstruating people’s access to reliable information about the menstrual cycle (WHO/UNICEF 2012 after Tull 2019: 3, 4). The Kulczyk Foundation in its international report on menstrual poverty entitled Bloody problem. Period poverty, why we need to end it and how to do it. emphasises that a supportive environment in which the topic of menstruation is not tabooed and stigmatised also remains a prerequisite for effective menstrual health and hygiene management. Effective menstrual health management (MHM) encompasses both economic and social and interpersonal factors that interact with each other (Kulczyk Foundation 2020: 5). Over the past few years, a number of NGO initiatives have emerged in Poland that are actively working to lift the menstrual taboo and counter menstrual exclusion. There is a chance that as time goes by, the problem will begin to be recognised in Poland, and this may contribute to its eradication. The content of this article presents selected results from a study on awareness and experiences of menstrual poverty among Polish women.

This article presents the results of a self-reported study carried out with 200 women. The quantitative study was carried out using an online survey, which was distributed via social media (Facebook) on a women’s group (#Asaversi)and via instant messaging (Messenger). Voluntary sampling was used. Data was collected in June 2022.

According to the conducted scientific search, the issue of menstrual poverty in Poland has not yet been the subject of extensive scientific research. The main objective of the conducted survey was to obtain information on the extent of knowledge of Polish women in the area of menstrual poverty. The survey was constructed on the basis of two main research questions: What is the extent of Polish women’s knowledge of menstrual poverty and ways to counter it? Do Polish women experience menstrual poverty and, if so, how? In many questions, female respondents were allowed to select more than one answer. Two questions were educational in nature.

The survey was targeted at women. The vast majority of those taking part in the survey were women aged between 19 and 30, who accounted for almost 84% of respondents. Most of the women surveyed lived in cities with more than 200,000 inhabitants. The distribution of the remaining group of surveyed women, living in smaller towns and villages, was almost proportional.

| Respondents | Indications | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | |

| Age | < 18 | 5 |

| 19–30 | 83 | |

| 31–45 | 7 | |

| 46–60 | 4 | |

| 61 > | 1 | |

| Place of residence | Rural | 29 |

| Town < 200 000 inhabitants | 32 | |

| Metropolitan > 200 000 inhabitants | 39 | |

| 1 | 2 | |

| Assessment of own financial situation | Very good/good | 49 |

| Satisfactory | 40 | |

| Unsatisfactory/Difficult | 10 | |

| Refusal to answer | 1 | |

| Education | Primary/Lower secondary | 4 |

| Secondary | 58 | |

| Higher | 38 |

The survey used the criterion of assessment of one’s own financial situation. One in ten respondents described their material situation as “unsatisfactory” or “difficult”. Almost half of the female respondents (49%) assessed their financial situation as “very good” or “good”. Female respondents were asked to indicate the highest education they had obtained at the time of the survey. More than half of the women surveyed had a secondary education, with 50% of the respondents declaring that they were continuing their education. The second largest group remained women declaring higher education.

Respondents were asked if they had ever encountered the term “menstrual poverty”. Over half of the responses were yes (54%), indicating, that as many as 46% of respondents had never encountered the term “menstrual poverty”. This result may be indicative of the tabooisation of menstruation and related issues in public discourse. Respondents who declared ignorance in this area were familiarised with the definition of menstrual poverty to enable the women interviewed to participate fully effectively in the study.

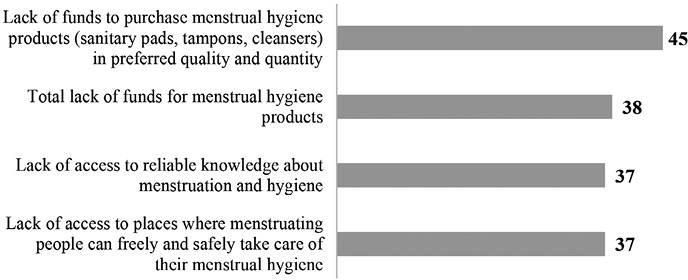

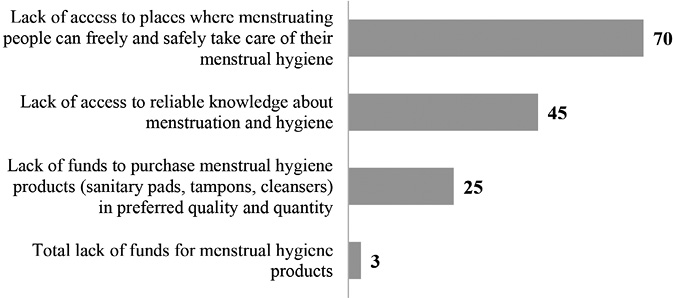

To introduce the respondents to the study, they were asked to indicate, from a given cafeteria, the dimensions of experiencing menstrual poverty. The graph shows a fairly proportional selection of responses that are manifestations of experiencing menstrual poverty. Respondents most frequently (45%) indicated a limitation in their ability to purchase menstrual hygiene products in their preferred quantity and quality. It was possible to indicate any number of responses, including not indicating any of the options given. Each respondents indicated at least one of the symptoms of experiencing menstrual poverty, which demonstrates the interviewed women’s understanding of the sources of the phenomenon.

Chart 1. Opinions of surveyed women on how menstruating people experience menstrual poverty? (N = 200; in %)*

* More than one answer possible

Source: own survey

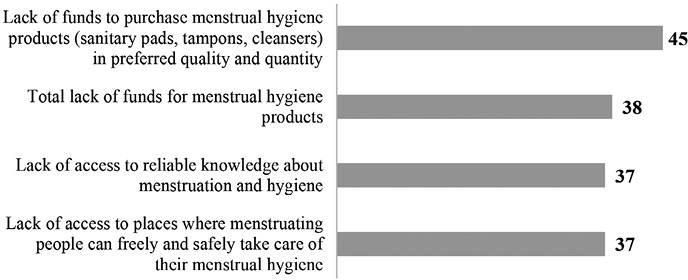

Chart 2. Vulnerable groups to experiencing menstrual poverty – in opinions of surveyed group of women (N = 200; in %)*

* More than one answer possible

Source: own survey

The study addressed groups particularly vulnerable to deprivation in the area of menstrual health and hygiene. Respondents were asked to indicate which groups of menstruating people they felt were particularly vulnerable to experiencing menstrual poverty. The most common responses indicated by female respondents remained, respectively, poor people, people in crisis of homelessness, people in a refugee/migration situation, and people affected by economic violence. Slightly more than half of the indications related to unemployed persons and teenagers. Literature relating to menstrual issues indicates a particular proportion of teenagers among groups experiencing menstrual exclusion. Adolescents are reluctant to talk to those close to them about menstruation, which remains a plane of informational exclusion and results in stigmatisation, as well as risking poor management of menstrual health and hygiene (Difference, Kulczyk Foundation 2020: 30–36).

Noteworthy is that all respondents unanimously agreed with the statement that experiencing menstrual poverty has an impact on the lives of those affected. The majority of the women interviewed (66%) agreed, that experiencing menstrual poverty impacts on the lives of menstruating people to a very high degree, while 31% responded that the impact remains significant. 3% of female respondents indicated that menstrual poverty affects the lives of individuals experiencing it to a small extent. The above is supported by the conclusion, that menstruation remains a significant dimension that impacts on other areas of social life.

Previous scientific knowledge on unmet needs in the area of menstrual hygiene has indicated that menstruating individuals living in low- and middle-income countries are affected. New research leads to the conclusion that experiencing symptoms of menstrual poverty also remains a problem for women of low economic status in high-income countries (Kuhlmann 2019 after Cardoso et al. 2021: 2). One in ten female respondents in the referenced study expressed a lack of satisfaction with their current material situation. According to the information obtained, 8 per cent of them experienced at least one of the given symptoms of menstrual poverty. An interesting finding of the study remains that 11% of the respondents who had ever experienced a total or partial lack of funds to purchase menstrual hygiene products described their current material situation as at least satisfactory or better, and the place of residence of most of them was a city of more than 200,000 inhabitants. In order to find out opinions on the incidence of menstrual poverty in Poland, female respondents were asked about it. A not inconsiderable proportion of the women surveyed (93%) perceived the existence of the problem of menstrual poverty in Poland.

Interestingly, half of the women surveyed (50%) indicated stigma and feelings of shame as the most distressing consequence of experiencing deprivation in the area of health and menstrual hygiene. The literature highlights that experiencing stigma and shame negatively affects menstruators’ life satisfaction and their ability to carry out daily activities, which translates into individuals withdrawing from society (Kulczyk Foundation 2020: 43). The referenced research findings indicate, that as often as psychosocial consequences, female respondents cited health consequences (39%). Research studies report that lack of knowledge about the treatment of infection and pain results in serious health problems (Kulczyk Foundation 2020: 43). Participants in the presented study prioritised the psychosocial effects of experiencing menstrual poverty over economic (6%) and educational (4%) consequences. Only two of the women interviewed (1%) did not indicate any of the stated consequences.

Almost all (96%) of the women surveyed agreed with the statement that the problem of menstrual poverty should be addressed by state institutions. Meanwhile, according to the previously cited studies, as well as our own observations, action in this area remains a grassroots initiative of NGOs. Since 2020, activists of the Periodic Coalition have been striving to bring the topic of menstrual poverty into the public debate and to change legislation, which resulted in the submission of a bill on menstrual poverty to the Parliament in June 2023 (Periodic Coalition 2023).

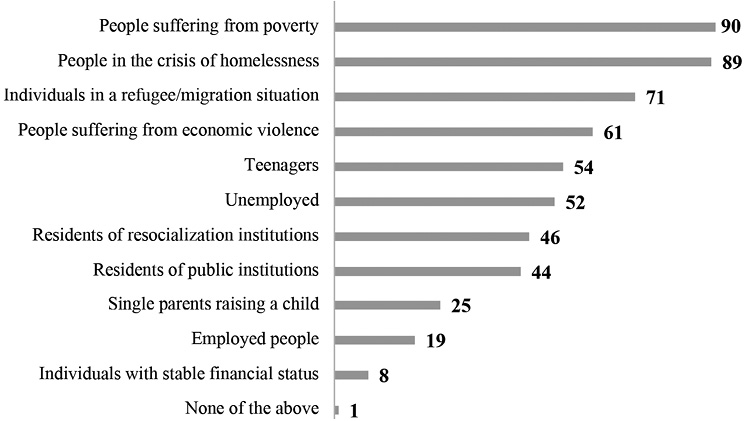

Chart 3. Knowledge of initiatives and non-governmental organizations that counteract menstrual poverty and attempt to abolish menstrual taboos – in the surveyed group of women (N = 102; in %)*

* More than one answer possible

Source: own survey

The survey asked female respondents about their knowledge of aid initiatives that remain aimed at intervening with people experiencing menstrual poverty, as well as popularising knowledge of this phenomenon. Slightly less than half of the female participants in the survey (49%) did not know how people experiencing menstrual poverty can get help. The topic of menstrual poverty and exclusion remains a socially tabooed phenomenon in Poland, but despite this, more and more initiatives are being developed in this area. Respondents declaring knowledge in this area (51%) were asked to indicate specific initiatives they knew.

The Pink Box Foundation remained the most frequently indicated answer (71%). Their activities focus on abolishing exclusion and menstrual taboos. The Pink Box Foundation also focuses on educating, as well as soliciting for universal access to knowledge about menstruation and fighting for systemic change on perimenstrual topics (Pink Box Foundation 2023). The activities of the Kulczyk Foundation and the team of authors of the international report on menstrual poverty, carried out within the framework of the same foundation, were very rarely mentioned. The results of the aforementioned report remain one of the main sources of many articles, including academic ones, addressing the topic of menstrual poverty. The Kulczyk Foundation remains a semi-transparent background to organisations that actively initiate activities in the public space. In addition to the most frequently selected initiatives: Biedronka&Femina (47%), Your Kaya (43%), Menstruation Action (40%), female respondents indicated other, unmentioned organisations. These included the Still Foundation and Procter&Gamble.

The exclusion of menstruating people from social life remains a consequence of the absence of menstrual issues in social discourse. The results of the referenced research show a high agreement of the women interviewed (88%) with the statement, that menstrual poverty is associated with a lack of conversation about menstruation. As the previously cited research shows, the tabooing and stigmatisation of the topic of menstruation strongly correlates with the emergence of myths about it. Furthermore, an overwhelming group of female respondents (90%) admitted to encountering mythicisation of the topic of menstruation. They were therefore asked to identify the myths they were aware of related to the topic of menstruation. The source of the given cafeteria of answers remains the publication Menstruation. A qualitative-quantitative research report prepared for the Kulczyk Foundation, which addresses the mythisation of the topic of menstruation (Difference, Kulczyk Foundation 2020: 18).

| Myths and beliefs | Indications |

|---|---|

| You cannot get pregnant during your menstruation | 87 |

| Menstruation must hurt | 86 |

| Physical activity should be strictly limited during menstruation | 46 |

| You should not bake cakes or pickle during your menstruation | 40 |

| Menstrual blood is dirty and toxic | 28 |

| You should not go to the dentist during your menstruation | 18 |

| Others | 5 |

| None of the above | 1 |

The above indications are justified by the lack of access to reliable knowledge about menstruation. The multiplicity and prevalence of scientifically unsubstantiated, stereotypical beliefs about menstruation are not conducive to its taming in public discourse. The most frequently identified myths about menstruation related to health aspects and dimensions result in reduced social activity. A not inconsiderable proportion of the population believes in the myths about menstruation presented in the table, which may result in the self-marginalisation of individuals during menstruation. Female respondents also pointed to culinary myths. They associated certain activities, or more precisely the prohibition of them, due to the ongoing menstruation at that time. These myths included baking cakes and pickling cucumbers. In addition, two respondents supplemented the category of gastronomic myths with other forbidden activities, i.e. making dumplings/cookies during menstruation results in failure.

As indicated by researchers, the tabooisation of menstruation contributes to the marginalisation of menstruating people and, moreover, results in a lack of facilities and adequate sanitation that allow for comfort and hygiene (Tull 2019: 6). An overwhelming group of female respondents in this study (92%) believe, that society places menstruation in the realm of taboo topics. This results in a lack of social discourse of menstruation. Attempts to normalise this area remain rather superficial and are not undertaken systemically. Many advertisements refer to experiencing menstruation as the days and depicts the blue menstrual blood, which denaturalises this physiological phenomenon (Difference, Kulczyk Foundation 2020: 11). The information contained in the Kulczyk Foundation’s comprehensive report reveals that menstruation remains a negative experience for one in four people menstruating. Furthermore, many adolescents face shame and fear of disclosing their ongoing menstruation (Difference, Kulczyk Foundation 2020: 23, 31–32). This article’s own research also addressed the issue of individual experiences of female respondents. The questionnaire included a question about the experience of being ridiculed, excluded or humiliated during menstruation. Almost half (48%) of the female respondents had experienced any of the above situations during menstruation. The data is worrying, as it shows that menstruation still remains a socially embarrassing subject, causing many negative emotions and experiences, and marginalising the people experiencing it.

Another issue that was addressed in the study presented here concerned the expenditure on menstrual hygiene. The majority of female respondents to the survey (93%) do not monitor their expenditure on menstrual hygiene at all. The survey questionnaire included an additional piece of information – a link directing respondents to a menstrual cost calculator. Thus, the survey was also applied. It encouraged to reflect on menstruation, as well as to try to estimate the expenditure on menstrual hygiene items.

As highlighted by researchers on the issue, the experience of menstrual poverty has not only economic and health dimensions, but also educational and psychosocial dimensions (Kulczyk 2022: 6). The complexity of the phenomenon of poverty and menstrual exclusion causes some difficulties in properly perceiving and defining it. In addition to the issues described above, the self-study also asked about the individual experiences of the women surveyed with regard to deprivation in the area of menstrual health and hygiene. It remains worrying that over half of the female respondents (55%) had been in a situation at least once in their lives that indicated that they were experiencing symptoms of menstrual poverty.

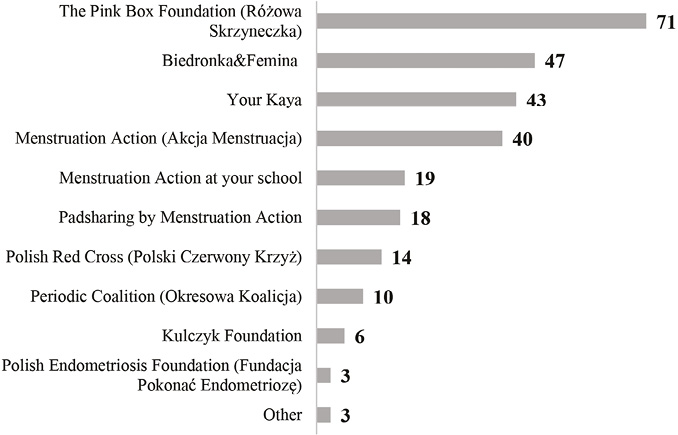

Chart 4. Experiencing menstrual poverty by the surveyed women (N = 109; in %)*

* More than one answer possible

Source: own survey

More than half of the women in the survey had experienced deprivation in terms of menstrual health and hygiene. The overwhelming majority of female respondents (70%) encountered with a lack of access to places to take care of menstrual hygiene in a relaxed and safe environment. In addition, slightly less than half of the women surveyed (45%) encountered constraints related to access to reliable menstrual knowledge. One in four respondents could not afford to stock up on at least once in her life of menstrual hygiene products in their preferred quantity and quality. 3% of the women surveyed experienced narrowly defined menstrual poverty, i.e. a complete lack of financial resources to purchase menstrual hygiene products. The results presented do not clearly indicate a high proportion of menstruating people who experience deprivation in terms of menstrual health and hygiene. However, the data shown articulates the frequent occurrence of situations in the lives of menstruating people that remain symptoms of menstrual poverty.

Respondents were also asked who they turn to for menstrual supplies. Respondents pointed to their immediate environment, as they usually turn for help to a partner, friend or other close person.

The women surveyed were also asked if they had ever had a menstruating person around them in whom they perceived symptoms of deprivation in terms of menstrual health and hygiene. The vast majority of women surveyed answered in the negative (78% of indications), while 6% of respondents refused to answer this question. 16% of the female respondents acknowledged that they had met a menstruating person who may have experienced menstrual poverty.

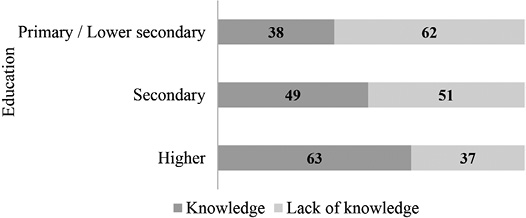

The vast majority (63%) of respondents declaring higher education knew what menstrual poverty is and how it manifests itself, while slightly less than half (49%) of respondents with secondary education had such knowledge. Among those who declared a primary education, ignorance in this area prevailed.

Chart 5. Knowledge of the concept of menstrual poverty and its symptoms by the respondents and the level of education (N = 200; in %)

Source: own survey

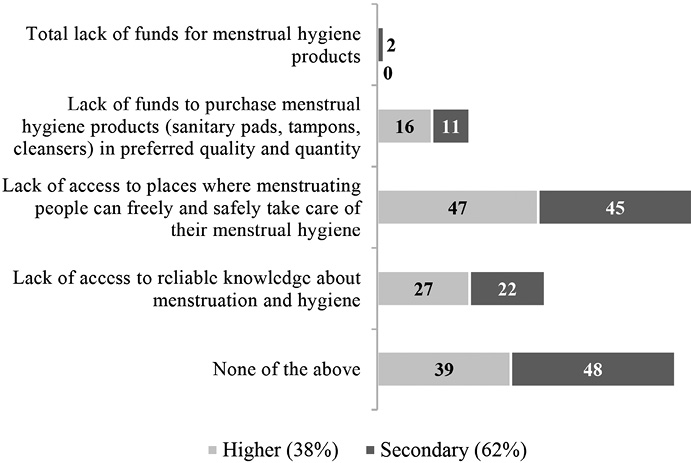

Women declaring primary, secondary or higher education participated in the survey. Only one person declaring primary education responded that she had encountered a lack of access to reliable information on menstruation. A complete lack of resources to purchase menstrual materials did not affect any of the women with higher education in the referenced study. 16% of the participants in the study who declared a higher education experienced a partial lack of funds to purchase menstrual hygiene supplies, in contrast to 11% among women with the highest level of secondary education at the time of the study.

The results of the survey show that, regardless of the educational level of menstruating women, they most often face a lack of access to safe places that allow them to take care of their menstrual hygiene with respect for intimacy and dignity. Menstruating people with both secondary and higher education experience menstruation-related information exclusion to a similar extent.

Chart 6. Experiencing menstrual poverty by the surveyed women and the level of education (N = 200; in %)*

* More than one answer possible

Source: own survey

The results of the referenced survey indicate that the vast majority of respondents living in rural areas did not know what the phenomenon of menstrual poverty prior to the survey (63% of indications). Also a large group, 39% of respondents living in cities, did not know the term. The results of the presented study show that menstruating women living in cities, slightly more often than women living in rural areas, encountered a lack of access to places where they can freely take care of their hygiene. In turn, rural residents experienced menstruation-related information exclusion with greater intensity than urban residents. Furthermore, female respondents living in rural areas were slightly more likely than urban residents to encounter myths about menstruation. Mocking, exclusion or humiliation was encountered slightly less frequently by female urban residents than by female rural residents. Slightly more than half (56%) of the respondents living in rural areas had experienced menstrual poverty. A worrying finding is that as many as 91% of urban respondents have experienced at least one symptom of menstrual poverty at least once in their lives.

The study presented in this communication had two objectives – scientific and applied. The main aim of the survey was to find out the opinions and individual experiences of the surveyed women in the area of menstrual poverty. Through the information contained in the survey, the aim was also to increase the awareness and knowledge of the surveyed women about this phenomenon. Until now, not much research has been conducted on menstrual poverty. The scientific literature on the social dimension of menstruation is still insufficient and menstrual issues are an invisible and shameful topic, especially in Polish society. It is therefore important to introduce an unfettered debate on the psychosocial difficulties associated with menstruation into the public discourse. After all, the experience of difficulties by certain social groups and individuals and the associated marginalisation of menstruating persons has an impact on the functioning of society as a whole. It also remains necessary to conduct comprehensive and representative research on the real risk of poverty and menstrual exclusion of women in Poland. The results presented in this communication may constitute a premise for further, in-depth research on the discussed topic.

Bank Światowy (2018), Zarządzanie higieną menstruacyjną umożliwia kobietom i dziewczętom pełne wykorzystanie ich potencjału, https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2018/05/25/menstrual-hygiene-management (accessed: 27.06.2023).

Cardoso L.F., Scolese A.M., Hamidaddin A., Gupta J. (2021), Period poverty and mental health implications among college-aged women in the United States, “BMC Women’s Health”, vol. 21, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-020-01149-5

Difference Market Research, Kulczyk Foundation (2020) Menstruacja. Raport z badania jakościowo-ilościowego przygotowany dla Kulczyk Foundation, Warszawa, pp. 11, 18, 23, 30–36, https://kulczykfoundation.org.pl/uploads/media/default/0001/05/0fbe618f4aa748170c8b3f096367e2c607888eb8.pdf (accessed: 26.06.2023).

Kopiec M. (2020), Interpelacja nr 3063 do ministra zdrowia w sprawie ubóstwa menstruacyjnego w Polsce, 2020, Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej, https://www.sejm.gov.pl/sejm9.nsf/InterpelacjaTresc.xsp?key=BMVEMG (accessed: 29.06.2023).

Kulczyk Foundation (2020), Bloody problem. Period poverty, why we need to end it and how to do it., pp. 5, 6, 43, https://kulczykfoundation.org.pl/uploads/media/default/0001/05/465728000cda27b8f50a3acc18d77c7b4df8b482.pdf (accessed: 26.06.2023).

Tull K. (2019) Period poverty impact on the economic empowerment of women, K4D Helpdesk Report 536. Institute of Development Studies, Brighton, UK, pp. 3, 4, 6, https://doi.org/10.29392/001c.32436

Websites

https://okresowakoalicja.pl/projekt-ustawy-o-ubostwie-menstruacyjnym-juz-w-sejmie (accessed: 29.06.2023).

https://rozowaskrzyneczka.pl/o-nas/ (accessed: 29.06.2023).

Abstrakt. Artykuł przedstawia wyniki badania ankietowego, dotyczącego wiedzy oraz doświadczeń Polek w obszarze ubóstwa menstruacyjnego. Podjęto w nim takie kwestie jak: wiedza respondentek na temat przejawów ubóstwa menstruacyjnego, charakterystyka grup szczególnie narażonych na deprywacje w zakresie zdrowia i higieny menstruacyjnej, a także wpływ ubóstwa menstruacyjnego na życie osób jego doświadczających. W badaniu poruszono problematykę tabuizacji oraz mityzacji tematu miesiączki. Respondentki zapytano również o inicjatywy na rzecz walki z ubóstwem menstruacyjnym. Kluczowym wątkiem w badaniu były także indywidualne doświadczenia respondentek w kwestii ubóstwa menstruacyjnego. Rezultaty badania wskazują, że ubóstwo menstruacyjne to niewidzialny i wstydliwy temat, zwłaszcza w polskim społeczeństwie. Istotnym jest zatem wprowadzenie do publicznego dyskursu nieskrępowanej debaty na temat psychospołecznych trudności związanych z menstruacją.

Słowa kluczowe: ubóstwo menstruacyjne, wykluczenie menstruacyjne, zdrowie i higiena menstruacyjna, tabuizacja, mityzacja.