https://orcid.org/0009-0007-0336-284X

https://orcid.org/0009-0007-0336-284X

Abstract. The article was devoted to analysing the specifics of the phenomenon of rituals and their social impact. Ritual activities can be diverse, and their characteristics are likely to be specific only to certain social groups. The peri-sport sphere is exceptionally saturated with ritual practices, and the interest in this phenomenon may be compounded by the fact that sports are a relatively under-researched area from a social perspective. In analysing aspects related to the practices in question, it was necessary to refer to psychological mechanisms, an anthropological perspective and a key one – the sociological approach of such theorists as Randall Collins, Erving Goffman, and Émile Durkheim.

In the remainder of the article, spectator and highly media-oriented sports were primarily scrutinised. These disciplines were chosen because the players practising them are characterised by a high degree of use of rituals, and they are activities that allow for more straightforward observation of many of the attributes associated with the practices in question. Prioritised in the context of this article was the analysis of a self-reported survey conducted on professional table tennis players. The fundamental data collection method was an online survey, the results augmented by participant observation. The purpose of the study was to find out the specifics of table tennis players’ rituals. Devoting attention to the plane associated with table tennis was essential due to the lack of scientific information on this social group and the widespread use of rituals by the players surveyed. As a result, the issue of athletes’ rituals was enriched with information on players’ habits of another exciting sport – table tennis.

Keywords: ritual, the social dimension of sports, contemporary, table tennis players, quantitative survey.

This article is devoted to a sociological analysis of the importance of rituals in the lives of athletes. Sports is a sphere of social life in which repetitive practices of a ritualistic nature are widespread. They have a particular impact on the functioning of athletes as individuals and in the context of group functioning – distinguishing them from each other while creating collective demands (Lenartowicz, Dobrzycki 2019: 74–83). The analysis was conducted on male and female table tennis players. The main research problem concerned the importance of rituals for table tennis players, accompanied by more specific research questions: What is the social extent of table tennis players’ rituals? How often do players perform rituals? What rituals do players practice? How do players define and perceive the impact of the rituals they practice?

An analysis of the importance of rituals in the lives of athletes requires placing the phenomenon under study in a broader theoretical context, as well as an approximation of what the role of rituals is in the context of the individual and the social view. The text references the theoretical works of such theorists as Randall Collins, Erving Goffman, and Émile Durkheim. Their assumptions and perceptions of rituals will impact the reflection strictly related to the possible properties of the ritual practices of sports players. The first part of the text provides an approximation of the scientific understanding and meaning of rituals. In the following part of the text, attention will be paid to contemporary rituals and specific practices observable in the peri-sport sphere. The next section of the article introduces my research methodology, while the last and most crucial part of the article is devoted to the analysis conducted on table tennis players.

Rituals are usually associated with a momentous ritual whose purpose is to bring about change, primarily in the status and role of the individual, which is what research anthropologists are most interested in. Victor Turner was an anthropologist who devoted much time to research on rituals and left a crucial mark in their analysis (Turner 2010: 115). The Briton made a significant impact trying to understand the essence of the practices in question, the description of their structure and properties. He introduced the rite of passage concept, derived from Arnold van Gennep’s approach (van Gennep 2006). Thanks to the broad interest of anthropologists in the phenomenon of ritual, they are generally identified with traditional societies. In contrast, today, in developed societies, the concept of ritual is much more complex and presented from different perspectives. Many rituals are firmly rooted in culture, inscribed to such an extent in the identity of individuals that they cannot function without them. For this reason, this phenomenon is an essential element in the functioning of society. Rituals often impart a high degree of organisation and systematisation in social life. On the other hand, it should be emphasised that the varieties, purposes, uses, and generally, the characteristics of rituals can change depending on the individual’s social role and his definition of the situation. Different rituals may be used by a labourer, a politician, a student and still others by an athlete, depending on the field of activity in which he finds himself.

In addition to the anthropological approach, the issue of the importance of rituals in the lives of athletes is also dealt with by social psychology. It allows us to understand in a certain way what is behind these repetitive actions and to find the mechanisms responsible for them. For example, a concept that may correspond to the rituals present in sports is the behavioural reinforcement theory created by Burrhus Frederic Skinner (Golnau 2018: 77–92). It primarily concerns reinforcing incentives contributing to winning or success during sports competitions. An athlete, seeing effective results, will repeat his ritual practices with much more enthusiasm. Another concept that inspires further psychological analysis of sports players’ rituals is the expectancy theory, created by Victor Vroom. According to it, when deciding on specific actions, an individual has certain expectations of them and expects imagined results (Vroom 1995: 350–432). When initiating a ritual correlated with a sport, the athlete has a form of desire associated with it, the manifestation of which is an expected result. In many cases, the athlete performs them to help himself somehow. On the other hand, different in its content but no less relevant to the subject of athletes’ rituals, is a mechanism called social proof. “Psychological research shows that people are more willing to engage in actions undertaken by others” (Dolinski 2002: 35–52). Seeing that a significant part of the group uses rituals, the individual also begins to replicate them. Very often, they become unique in some way and can be considered an identity feature of the social group. The last doctrine that will be addressed with athletes’ rituals in a psychological context concerns obsessive-compulsive disorder, otherwise known as obsessive neurosis. Sometimes ritual practices can manifest this nature. Over time, they no longer provide any form of pleasure, and their use becomes a real torment.

It should be emphasised that sociological theories that address the subject of ritual are much more in line with modern times and primarily the sports sphere. Erving Goffman (2012) and Randall Collins (2011) are among the sociological classics who have spent considerable time analysing the phenomenon of ritual in their reflections, and their interpretations can be applied to sports players (even if they mainly emphasised the interactional dimensions of rituals). First of all, Goffman and Collins pay attention to the concept of the situation when interpreting the phenomenon of ritual. In the case of athletes, this also becomes relevant since participation in the situation of training or sports competition conditions the ritual activities of the athlete. In his concepts, Goffman also referred extensively to the notion of stage and backstage, where for an athlete, such a place could be the field or hall, where the athlete undertakes competition and practices rituals. On the other hand, Collins mainly referred to the interactional form of repetitive practices, in which the mechanisms of emotional charge, attachment to symbols, and the related issue of motivation can also be referred to as athletes’ experiences (Collins 2011: 3–12). Another critical assumption of classic sociologists is to pay attention to the element of repetition of rituals, which, according to Émile Durkheim, makes them durable and robust (Durkheim 2010). The cited thought can also be applied and compared to the world of sports. The longer one practices rituals and has a conviction of their effectiveness, the more valuable they will be to the athlete and the consequence of which can be a great attachment to them. The cited theorist also alluded to maintaining group cohesion when analysing rituals. In sports, there are many practices that, when repeated systematically, can serve to maintain group unity, especially in the context of the so-called team spirit.

The space of the article needs to be more modest to recapitulate in detail the concepts of the theorists cited here, and it is also challenging to evoke a single, universal concept of ritual ideally suited to interpreting athletes’ behaviour. Given the interdisciplinary significance of ritual (from psychological meanings to social conditions), one may also be tempted to propose one’s understanding of ritual in the context of athletes’ practices. Ritual, concerning athletes, is a repetitive activity that deals with phenomena that have a specific meaning for the individual. It has a specific purpose, value and content and is accompanied by a subjective motive and emotion. It is associated with a specific place and situation in space. An important aspect is a specific scheme based on which a ritual is performed. Its basis can be secular or sacred, and the nature of the action is individual or collective. Only the individuals participating in it experience it fully. Rituals may be characterised by a particular frequency of their performance within a particular social group and replicated by a significant part. However, the isolated characteristics regarding such practices are diverse and dependent on the individual’s disposition. The next section of the article will aim to show (among other things, based on previous research) what such rituals look like in sports. It will attempt to interpret, to show the variation in the properties of rituals practised by players and teams in different sports.

The corporeal correlates of the repetitive practices of athletes are a noteworthy issue due to their frequent occurrence in modern society (Hargreaves 1995: 139–159). The role of the body is irreplaceable because, without bodily involvement, most sports would not exist. In addition to the necessity of engaging the athlete’s physical sphere, related to the desire to perform the role to the best of one’s ability, there are correlations with such planes as symbolism, emotions, defining situations, or at least – with the motivational field. A player’s body language can serve as a tool to convey something more than an imposed game strategy. Posture, gesticulation or motor activity can be used for varied practices and forms that carry an established message. A plethora of bodily practices and habits can be observed among footballers. Most of them are related to celebrating a goal (Turner 2012: 1–18). Krzysztof Piątek’s celebration seems to be the most characteristic, especially for Polish fans. After a goal is scored, the Polish footballer to his knees on the run and, crossing his arms, performs imitations of gunshots. Observing football matches, one can conclude that the more prestigious the games are, the more often the players perform their unique celebratory rituals. On the other hand, in other bodily rituals, one can notice the presence of a religious aspect. Before entering the field, Spaniards habitually touch the turf with their hand, kiss their palm, and make the sign of the cross, not infrequently looking up to the sky. Others are tasked with conveying a specific message – like the fact that their partner is pregnant. Football players convey such a message by holding their bellies and imitating thumb-sucking immediately after scoring a goal. However, tennis player Rafael Nadal is a specific symbol of bodily rituals. The Spaniard must touch his hair and nose before each serve. Without this action – he will not perform the service.

Repetitive practices, which need a form associated with spoken language to exist, can be called – verbal rituals. A bonding structure is formed around a team with similar goals and values. For this reason, a social group can share the same emotions and mutually “infect” each other with them: “As a result, the emotional mood becomes stronger and more dominant; competing feelings are displaced by the main group feeling” (Collins 2011: 129). The team becomes a unity in such moments and a collective that depends on each other and its emotions, which corresponds to the concept of group solidarity, which Émile Durkheim referred to as religious rituals and the aspect of integration (Jacher 1973: 43–62). In sports, such emotions often correlate with the interaction present during games, visible in various forms – interaction. Verbal rituals can cause an individual to be filled with much greater energy, motivation, confidence and willingness to fight. People who share a common vision and desire can motivate each other to succeed. Therefore, verbal forms of repetitive practices usually have positive and mobilising overtones. The tone, the timing of their performance, or, for example, the people toward whom the activity is performed – can be significant. As with any ritual, individuals may have their individual and specific habits. However, in the case of their verbal manifestation, they are often collective, shared by the group.

Numerous chants, slang or specific shouts are the most common form of such rituals. In the Polish sports world, the phrase “na cześć osób z drużyny przeciwnej, cześć!” which means: “in honour of those on the opposing team, cheers!” and has become accepted in many disciplines, emphasising the respect directed at competitors. However, in the context of chants, one of the most recognisable rituals seems to be the celebration of the Polish national football team, who, after a victory, sing such Polish hits as: “Bałkanica”, “Przez twe oczy zielone” or “Ona tańczy dla mnie”. This practice occurs in sports (especially at its professional level) relatively often, symbolising the joy of the players. Another recurring verbal practice is used by famous Brazilian football player Neymar, which involves a brief conversation with his father before the start of a match. Meanwhile, spoken language is also used when celebrating a goal or the joy of a point won, such as Iga Światek’s characteristic cry of “Jazda!” after almost every point scored. Verbal rituals, like bodily ones, are prevalent in the peri-sports sphere.

In the peri-sport area, many objects or objects simultaneously symbolise or carry significant meaning, becoming part of the athlete’s ritual. Despite their defined role and purpose, they can be treated ambiguously, creating their new use for the individual. One can think of such artefacts as trophies, clothing, jewellery or, for example, sports equipment. Athletes can create a certain aura around them, which they believe is conducive to good luck or hinders their path to success. This perception of “talismans” can be motivated by diverse factors. Religious, magical or separate from these spheres, secular content can be associated with the objects. Durkheim identified sacred things with emotions associated with a sense of attachment (Jacher 1973: 43–62).

It is also not uncommon for rituals concerning a particular artefact to be related to superstitions (Maranise 2013: 83–91) that the player believes in. A fascinating ritual is the one used by all athletes participating in one of the Grand Slam tennis tournaments – Wimbledon:

Athletes participating in this spectacle are required to choose tennis clothing only in white, and this rule applies to both male and female tennis players. This element symbolically can indicate the equality of all athletes, who prove their worth and superiority only on the tennis court, not racing, by competitions for the highest number of sponsor names written on their shirts (Kubaniec 2020: 65–76).

This is a collective ritual of players that has become a tradition. Another practice is for players to remove their jerseys after scoring a goal. Usually, this action is intended to convey a message from a particular player symbolically.

An example is the practice of Brazilian footballer Kaká, who, to show his deep faith to all viewers, wore a white one with the inscription “I belong to Jesus” under his club jersey. Meanwhile, when it comes to the specific habits of athletes, tennis player Rafael Nadal should be mentioned again. Before making a serve, the Spaniard must touch his shorts and socks. Rituals associated with artefacts are among the most diverse. This is due to the vast number of objects a ritual aura can surround.

The last ritual plane to be addressed is the mental one. It connects with imagined practices that usually exist mainly in the athlete’s imagination. They are often superstitions or the religious sphere close to the athlete. It is worth noting that a significant part of mental rituals are associated with superstitions or superstitions (Bleak, Frederick 1998: 1–15) that the athlete believes in. Habits, most of whose “scenario” takes place in the athlete’s imagination, manifest much freedom and flexibility in their possible variations. Such a superstition can be an athlete’s attachment to a certain number. Former Real Madrid football player Iván Zamorano showed loyalty to his lucky symbol powerfully. This was the number “9”, which for a long time appeared on his jersey during football matches. Another type of mental ritual, unrelated to a lucky or unlucky number, can be the belief in horoscopes and related beliefs about an individual’s future or character. They set a particular path that a superstitious athlete is inclined to follow. The tendency to believe in the validity of horoscopes and similar “prophecies” is distinguished by a former football player and current coach of Atlético Madrid club – Diego Simeone. With the issue of the presence of “magical” behaviours, it is important to note that in the sphere of sports, they are also popular among fans, as Przemysław Nosal touched on the example of bookmaker betting (Nosal 2023: 18–21). Mental rituals, on the other hand, lacking the approximate specificity focused on superstition, are often associated with prayer (Watson, Czech 2005: 1–16), visualisation of games or self-motivation.

Although the presented rituals were discussed separately as separate forms of activities, it should be noted that each of the cited areas can intertwine. Rituals are not always closely related to only one sphere, and this is due to their properties, which can be highly complex and multifaceted. As a specific underlying pattern, one can again invoke the figure of Rafael Nadal, whose habits would indeed find reference in each of the categories mentioned. For this reason, it is essential to remember that ritual is a highly multidimensional phenomenon, and sometimes its structure is not as simple as it may seem. Their multifaceted nature and popularity should prompt sociologists or psychologists to look more precisely at specifics. In the rest of this article, we will look at what properties the rituals of table tennis players have.

Table tennis is a sport relatively rarely studied regarding social functioning (Ciok, Lenartowicz 2020). Researchers, especially sociologists, do not address the ritual practices of the players of this sport and their social impact in their analyses. The following study fills this gap to some extent.

The discipline of table tennis and its players were chosen because of my own experience: I have been training the sport professionally for 18 years. Such long-standing expertise in functioning in the studied environment allowed me to move freely among the players and athletes and establish contact with them. The risk is that excessive “immersion” in the studied environment, an “insider” position, can lead to value judgments, certain simplifications and a lack of criticism. Despite such risks, I treated the table tennis environment as professionally as possible, maintaining objectivity and scientific integrity in my explanations.

The primary measurement tool was the CAWI technique, supported by the one I conducted – participant observation. CAWI is a data collection method that allows you to get responses from multiple respondents. Another impetus behind the choice of analysis tool was my seniority in the material collection environment. Being part of the table tennis community made getting the desired response returns much more accessible. Another factor that determined the choice of data collection technique was its possible reach. I could send questions to players from different parts of Poland through the online survey. On the other hand, it should also be mentioned what limitations the CAWI method may carry. The main drawback is the lack of adequate control over the respondent. Sending the survey over the Internet, we cannot control what happens later. The individual filling it out may not be the person whose answers we care about. However, in the case of a survey on athletes’ rituals, this is unlikely since the specifics of the questions correspond to a group like table tennis players. In analysing the goods and weaknesses of the chosen quantitative method, it is essential to emphasise that, despite the limitations, the material collected offered the possibility of concluding the rituals of table tennis.

An additional tool used in the study was overt participatory and non-participatory observation (Frankfort-Nachmias, Nachmias 2001: 220–239). With the ability to actively participate in the table tennis environment, systematically monitor players’ rituals and thus apply triangulation becomes available (Webb 2006: 449–458). The observation focused on the practices of either training or competition at different moments of activity. It is a qualitative snapshot that can enrich the study with essential conclusions.

Undoubtedly, a significant factor in the study is sampling (Babbie 2013: 204–206). Non-random selection methods – non-probabilistic – were used in the quantitative analysis. This is a technique in which the selection of respondents is usually subjective due to the knowledge of the specific structure of the study population. In the study on table tennis players, this type of respondent selection was desirable due to the focus on professional players only. Accordingly, two procedures were implemented. The first was the purposive selection method. It involves intentionally selecting respondents who qualify for specific characteristics correlated with the study. The second technique was the snowball selection method. A player who completed the survey was asked to pass it on to more tennis players.

Based on the research questions posed, the following hypotheses were formed and verified based on the self-examination:

In addition, the following section will analyse and interpret the qualitative method used, which played an enriching role in the results of the primary form of exploration of the table tennis community – an online survey.

A total of 108 professional male and female tennis players participated in the survey. The respondents belonged to different sports clubs, but all represented national colours belonging to Poland and had several years of playing experience. The selected players played in the country’s top leagues and appeared in the most prestigious tournaments at the national or international level. Their age varied, but most respondents were 19–21 (youth players) or 22–39 (seniors). At the same time, it is worth noting that the categories were divided according to the official regulations on the age range in Polish table tennis. After receiving the returns satisfactorily, there was a stage of precise data transfer to the SPSS statistical program.

This section will discuss the main results of the research conducted on table tennis players. First, it is advisable to present the quantitative method’s results. The base issue was to determine whether the players have any rituals related to the peri-sport sphere. The definition of the term ritual, adopted in the article, was presented to the respondents in a descriptive way in the questionnaire’s introduction. I divided the issue into repetitive activities correlated with training and table tennis competitions. Thanks to this juxtaposition, I can compare the two situations and conclude that a more significant proportion of respondents have rituals correlated with professional games (96.5%) than with training (90.4%). However, this is a slight difference, and it should be emphasised that in both cases, almost all players have their ritual habits. The data obtained from the survey leads to the conclusion that rituals are a widespread activity and have a specific role in the sports life of table tennis players. The following more detailed results will be presented in the form of charts.

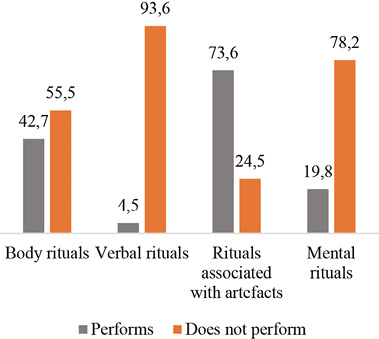

Chart 1. The type of rituals performed related to table tennis training (%)

Source: own research

Chart 2. Type of rituals performed related to table tennis competitions (%)

Source: own research

The charts presented above show data related to the characteristics of players’ rituals. Respondents who had previously declared practising rituals during training and/or competition were asked to describe their repetitive habits. A thorough analysis of each stated practice was necessary to separate the categories. Notably, the forms of rituals created did not blend, and their categorisation was not in doubt. Body rituals show the highest percentage of use among players when associated with training (46.4%), while those correlated with artefacts when associated with table tennis competitions (73.6%). It should be noted that the listed habits most often corresponded to both categories. Verbal rituals (less than 6%) and mental rituals (less than 20%) were used much less frequently by respondents, regardless of the type of activity. Several recurring practices, as well as more personalised and original ones, could be found in respondents’ answers. Providing examples of tennis players’ rituals relevant to the study is advisable.

| Ritual | Number of indications | Percentage of indications |

|---|---|---|

| Listening to music | 76 | 70.3 |

| Wearing a lucky shirt | 66 | 61.1 |

| Bounce the ball a specific number of times | 65 | 60.1 |

| Folding a towel into a cube | 44 | 40.7 |

| Touching the soles of shoes with the palm of the hand | 38 | 35.1 |

| Wearing special jewellery | 31 | 28.7 |

| Mental self-motivation | 30 | 27.7 |

Above, in the form of a table, the frequently repeated practices in the respondents’ declared answers were singled out. The listed activities were arranged in descending order, starting with the most frequently used ritual. It can be noted that (as the previous charts indicated) – practices related to artefacts predominate. It should be noted that rituals involving listening to music (70.3%), wearing a lucky shirt (61.1%) and bouncing a ball (60.1%) were mentioned by far the most frequently. This shows that repetitive practices are characteristic of the general collective in a sport like table tennis.

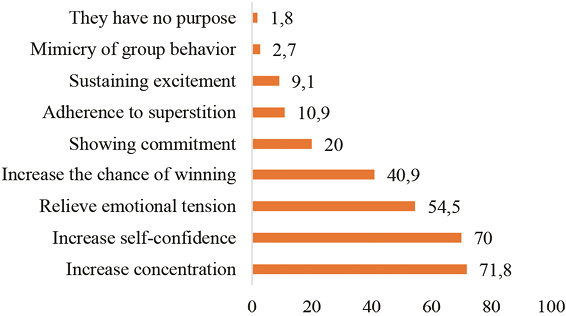

Chart 3. Purpose of the players practising table tennis rituals (%)

Source: own research

An essential question for the study was the issue of the purpose of tennis players practising rituals. It turns out that only 1.8% of players believe that their habitual actions have no meaning. This shows that by their practices, almost all respondents aim at something and have a specific, rational purpose. Most often, the intention of their rituals is correlated with increasing concentration (71.8%) and self-confidence (70%). Relatively often, tennis players also chose a role related to relieving emotional tension (54.5%) and increasing the chance of winning (40.9%). It is advisable to mention that those with religious rituals were much more likely to indicate the goal of observing superstitions (10.9%). Few respondents felt that the purpose of their rituals was to imitate the group’s behaviour (2.7%).

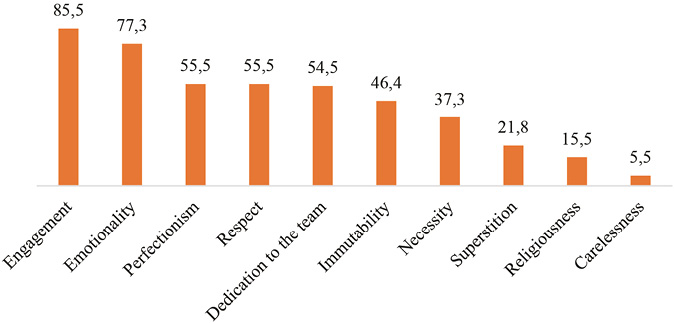

Chart 4. Terms that match the rituals of the players associated with table tennis (%)

Source: own research

Players should have assigned corresponding terms to them to understand the rituals’ characteristics better. The most significant number of respondents are related to commitment (85.5%) and emotionality (77.3%). Most tennis players’ qualities require a significant personal contribution and a particular effort on the part of the individual. This indicates that they are primarily attached to them and do not treat their rituals unequally. Such qualities as respect (55.5%) and devotion to the team (54.5%) undoubtedly have positive overtones, with which more than half of the respondents identify. In contrast, a trait with a more negative tinge – carelessness – was indicated as a property of rituals in only 5.5% of players.

| I agree | I rather agree | I rather disagree | I disagree | Hard to say | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Keeping your fingers crossed brings good luck | 22,2 | 38,9 | 10,2 | 22,2 | 6,5 |

| Grabbing a button when meeting a chimney sweep brings good luck | 9,3 | 25,9 | 24,1 | 37,0 | 3,7 |

| A found four-leaf clover brings good luck | 23,1 | 34,3 | 12,0 | 25,9 | 4,6 |

| Breaking a mirror brings 7 years of misery | 7,4 | 26,9 | 16,7 | 42,6 | 6,5 |

| Seeing a black cat crossing the road brings lousy luck | 9,3 | 19,4 | 25,9 | 39,8 | 5,6 |

| Shaking hands across the threshold brings lousy luck | 8,3 | 23,1 | 20,4 | 44,4 | 3,7 |

| The number 13 brings bad luck | 7,4 | 22,2 | 15,7 | 50,9 | 3,7 |

| It is necessary to knock on wood so as not to zap the excellent fortune | 10,2 | 31,5 | 14,8 | 38,0 | 5,6 |

| Getting out of bed with the left foot causes failures alone | 6,5 | 27,8 | 14,8 | 44,4 | 6,5 |

| Spilt salt brings bad luck | 5,6 | 23,1 | 15,7 | 48,1 | 7,4 |

Surveys conducted by CBOS show that in an increasingly rationalised world, the belief of Polish people in superstitions is still alive, and irrational customs continue to be quite popular in practice (CBOS 2018). Similar conclusions can be drawn from the table presented above, showing the degree to which athletes believe in the most common Polish superstitions unrelated to the sport they practice. During the study, examining the respondents’ susceptibility to superstitions unrelated to sports was deemed advisable to see if this impacts the number of rituals used and their characteristics. As can be seen, the percentages were distributed very differently, depending on the superstition in question. Most people believe in good luck, which they think is brought by keeping one’s fingers crossed and a four-leaf conch found. In contrast, the above data allowed us to draw the statistical conclusion that superstitious athletes have 19.4% more rituals than non-superstitious athletes, meaning those characterised by magical or irrational thinking are more prone to ritualistic behaviour. The obtained result indicates that superstitiousness, embodied in everyday life, may influence the amount of table tennis-related rituals used. Despite the presence of the cited relationship, it should be emphasised that non-superstitious players dominate the table tennis community.

In addition to the quantitative study discussed above, it is also worth considering the conclusions of the additionally conducted – qualitative analysis. Thanks to my personal experience, I systematically observed tennis players’ habits – regularly and over a long period. Participating in training and competitions daily, I had freedom and easy access to the subject of my study. The observation confirmed all the results collated so far, collected with the quantitative tool.

The first observable tendency relates to the players’ failure to consider shouts as their ritual. Very few of the respondents considered them when filling out the questionnaire. This result may surprise me since I can conclude that most tennis players have their own and often original shouts through regular observation. Athletes use them after winning a point or a match – celebrating victory. Reflecting on the fact that shouts are not counted as rituals, the following conclusion emerges. The players consider this practice exclusively part of the game or their strategy. Thus, it is a highly automatic activity identified with the games’ premise or concept. At the same time, it is not a ritual accompanied by complex symbolism.

Other customs whose presence was relatively low in the players’ responses were practices of a collective nature. In general, each respondent focused only on describing individual rituals. In doing so, it is essential to confirm the fact that they are the ones that significantly predominate in the athletes’ daily practices. However, observation proves that group rituals are also a widespread habit of athletes. Many professional tennis players are in the habit of eating dinner together with their team after a league match or competition. Regardless of the sports club attended, this ritual integrates the team and creates an aura of togetherness. It is a widespread practice that has become self-rule within the sport. Regardless of the result, every player seems aware that this ritual must be performed. Another supra-individual activity involves forgoing practice the day before games to spend it with teammates. This is a widespread practice that relaxes the player physically and mentally. The players spend time together so they do not think about the upcoming competition and thus do not get overly stressed. A vast number of tennis players use the cited ritual, and it can be said that it is also a strategic element through which the individual “clears his head”. One can first point out that table tennis is primarily an individual sport to justify the lack of group rituals in the respondents’ declarations. Consequently, rituals are associated with players in an individual and personal way. During the competition, they mainly rely on themselves, and it is up to them to determine how the game turns out. For this reason, the concept of ritual can be equated by tennis players with individual habits correlated with the sport they practice.

Above were approximations of the rituals used by the players, the presence of which could not be ascertained by analysing the quantitative survey. This shows that long-term and systematic observation was valuable for collecting material, enriching and justifying general conclusions. Wanting to deepen the analysis of a given issue further, it would make sense to conduct individual qualitative interviews with athletes.

An essential part of analysing the survey results is subjecting the research hypotheses set earlier to verification. Their confirmation/rejection will be resolved based on the quantitative survey supported by observation. In one case, the Spearman test was applied, but with the rest of the assumptions, it was impossible due to the nominal nature of the variables used. The hypotheses in question will be restated below, along with assessing their relevance to the data obtained.

Hypothesis confirmed. The quantitative study showed that 100% of the table tennis players surveyed use certain rituals associated with the sport (during training and/or competition). According to the results, it can be seen that the strength with which they correlate with particular individuals varies and depends on many factors. On the other hand, this does not change the fact that rituals are prevalent and overly used by tennis players.

Hypothesis rejected. Despite the high popularity of the use of body rituals, the most significant number of athletes reported having artefact-related practices. However, it should be noted that both of the cited categories dominate table tennis.

Hypothesis rejected. The purposes for which tennis players use their circadian rituals were highly variable. The intention to increase self-confidence was among the most frequently stated responses (70%). In contrast, players most often practice rituals to increase concentration (71.8%). As can be seen, this is not a large discrepancy, and both tendencies can be considered equally important.

Hypothesis confirmed. It was interesting to test the correlation between superstitiousness and ritual use. The quantitative study concluded that superstitious athletes have 19.4% more rituals than non-superstitious people. Such a result confirms the above hypothesis and the assumed correlation between the two variables. Despite the above result, verifying the obtained result further using Spearman’s test carried out in the SPSS statistical program for the quoted assumption was advisable. The strength of the correlation of the relationship between superstitiousness and the number of rituals used was measured. It oscillated close to a result equal to 0.6, indicating a moderately strong correlation.

In addition to verifying the hypotheses mentioned above, the study expanded knowledge regarding the peri-sport rituals associated with the niche sport of table tennis. Due to the limited research exploration of the social group in question, the results bring a certain amount of new knowledge. The study shows that the social practice area of athletes can be highly complex and exciting. It is worth studying to scientifically enrich sociological disciplines or sub-disciplines with further intriguing aspects of issues related to sports’ social groups.

Babbie E. (2013), Logika doboru próby, transl. A. Kloskowska-Dudzińska, [in:] Badania społeczne w praktyce, Warszawa.

Bleak J.L., Frederick C.M. (1998), Superstitious behaviour in sport: Levels of effectiveness and determinants of use in three collegiate sports, “Journal of Sport Behavior”, vol. 21(1), Washington.

CBOS (2018), Komunikat z badań: Przesądny jak Polak, Nr 93/2018, https://www.cbos.pl/SPISKOM.POL/2018/K_093_18.PDF

Ciok A., Lenartowicz M. (2020), Sportowi migranci. Zagraniczni zawodnicy w polskich ligach tenisa stołowego, Warszawa.

Collins R. (2011), Łańcuchy rytuałów interakcyjnych, transl. K. Suwada, Kraków.

Doliński D. (2002), Wpływ społeczny a jakość życia, [in:] Psychologia jakości życia, vol. 1, Warszawa.

Durkheim É. (2010), Elementarne formy życia religijnego, transl. A. Zdrożyńska, Warszawa.

Frankfort-Nachmias Ch., Nachmias D. (2001), Metody badawcze w naukach społecznych, Poznań.

Gennep van A. (2006), Obrzędy przejścia. Systematyczne studium ceremonii, Warszawa.

Goffman E. (2012), Rytuał Interakcyjny, transl. A. Szulżycka, Warszawa.

Golnau W. (2018), Teoretyczne podstawy i zasady kształtowania wynagrodzeń za pracę według wyników (część 1), “Zarządzanie i Finanse”, vol. 16.

Hargreaves J. (1985), The Body, Sport and Power Relations, “The Sociological Review”, 33(1_suppl), https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.1985.tb03304.x

Jacher W. (1973), Emila Durkheima koncepcja religii jako czynnika integracji społecznej, “Studia Philosophiae Christianae”, vol. 9(2).

Kubaniec D. (2021), Komunikacja niewerbalna i wykorzystanie gestów w sporcie, “Media – Kultura – Komunikacja Społeczna”, vol. 2(16).

Lenartowicz M., Dobrzycki A. (2019), Sumnerowski etos sportowo-rekreacyjny – obyczaje i wzory zachowań w kulturze fizycznej, [in:] Z. Dziubiński, N. Organista (eds.), Kultura fizyczna a etos, AWF Warszawa, SALOS RP, Warszawa.

Maranise A. (2013), Superstition & Religious Ritual: An Examination of Their Effects and Utilisation in Sport, “Sport Psychologist”.

Nosal P. (2023), Sportowe zakłady bukmacherskie. Społeczna praktyka grania, Wydawnictwo Naukowe UAM, Poznań.

Turner M. (2012), From ‘pats on the back’ to ‘dummy sucking’: a critique of the changing social, cultural and political significance of football goal celebrations, “Soccer & Society”, vol. 13:1, https://doi.org/10.1080/14660970.2012.627164

Turner V. (2010), Liminalność i Communitas, [in:] Proces rytualny. Struktura i antystruktura, transl. E. Dżurak, Warszawa.

Vroom V.H. (1995), Work and Motivation, San Francisco.

Watson N.J., Czech D.R. (2005), The Use of Prayer in Sport: Implications for Sport Psychology Consulting, “Athletic Insight – The Online Journal of Sport Psychology”.

Webb E.J. (2006), Unconventionaly, Triangulation, and Inference, [in:] N.K. Denzin, Sociological Methods: A Sourcebook.

Żerdziński M. (2007), Poradnik dla chorych na zespół natręctw, http://centrumpsychiatrii.home.pl/php/wyslane/aktualnosci/pliki/poradnik2.pdf

Abstrakt. Artykuł został poświęcony analizie specyfiki zjawiska rytuałów i ich społecznego oddziaływania. Działania rytualne mogą być zróżnicowane, a ich cechy charakterystyczne tylko dla określonych grup społecznych. Sfera okołosportowa jest niezwykle bogata w zastosowanie rytuałów, a zainteresowanie tym fenomenem potęgować może fakt, iż sport jest relatywnie słabo przebadanym obszarem pod kątem społecznym. Przy analizie aspektów związanych z omawianymi praktykami, konieczne było odniesienie do mechanizmów psychologicznych, perspektywy antropologicznej oraz kluczowego – ujęcia socjologicznego takich teoretyków jak: Randall Collins, Erving Goffman, czy Émile Durkheim. W dalszej części artykułu pod ogląd zostały wzięte przede wszystkim sporty widowiskowe i wysoce medialne. Dyscypliny te zostały wybrane, ponieważ zawodnicy je uprawiający charakteryzują się wysokim stopniem zastosowania rytuałów oraz są to aktywności, które pozwalają na łatwiejsze zaobserwowanie wielu atrybutów związanych omawianymi praktykami. Priorytetowa w kontekście niniejszego artykuły była analiza badania własnego, przeprowadzonego na profesjonalnych tenisistach stołowych. Kluczową metodą zbierania danych została ankieta internetowa, której wyniki wzbogaciła obserwacja uczestnicząca. Celem badania było poznanie specyfiki rytuałów tenisistów stołowych. Poświęcenie uwagi płaszczyźnie związanej z tenisem stołowym było istotne, ze względu na brak naukowych informacji na temat tej grupy społecznej oraz z uwagi na powszechne stosowanie rytuałów przez badanych zawodników. W efekcie, problematyka rytuałów sportowców, została wzbogacona o informacje dotyczące nawyków zawodników kolejnej, niezwykle interesującej dyscypliny sportowej, jaką jest tenis stołowy.

Słowa kluczowe: rytuał, społeczny wymiar sportu, współczesność, tenisiści stołowi, badanie ilościowe.