Abstract. This paper seeks to contribute to debates about the negative consequences of inequality, by examining the resilience of the failed and damaging doctrines of neoliberal supply-sidism in terms of the powerful hegemony of economic and political interests allied to the financial services sector, focussing the role of the UK in facilitating that hegemony. It deploys the concept “permissive neoliberalism”, signifying both the formal embedding of property rights over financial assets as the legal encoding of the short-term predatory hunt for “yield”, and the political toleration of criminal and criminogenic activity. The description of some of the most egregious examples of predatory financialisation illuminates the sanctification by the neoliberal state of ruthless value-extraction and the toleration of an increasingly chronic dependence on of the UK political economy on the City of London and its archipelago of secrecy jurisdictions.

The shorter second part of the paper charts the growth of a mindset of entitlement on the part of economic and political elites and the role of psychopathic narcissism in crafting a legitimating narrative of their hegemony. The chronic disorder in the allocation of humanity’s material and financial resources invites a strong conclusion that financialised capitalism is not simply “killing the host” qua sustainable economic order, but is threatening the very survival of humanity’s biosphere by blocking the deployment of financial and human capital at sufficient scale to rescue the world’s climate from catastrophe.

Keywords: financialised capitalism, neoliberalism, misallocation of capital, negative environmental effects, ecocidal trend

Towards a theory of parasitic value-extraction.

In Killing the Host, Michael Hudson (2015) employs the metaphor of destructive parasitism in the global political economy in a direct and persuasive way; the “host” is the capitalist economic order. This paper deploys the metaphor beyond Hudson’s politico-economic effect to assert that the host is indeed the whole biosphere upon which humanity and other living organisms depend; its provisional conclusion is that the fundamental misallocation of capital inherent in financialised capitalism represents a critical diversion of resources AWAY from the urgent priority of ensuring the environmental sustainability of the planet and that, in the absence of an effective reversal of that misallocation, the host qua biosphere will be critically damaged. This deliberately alarming hypothesis nevertheless chimes with the thinking of those advocating a progressive and radical socio-ecological transformation, but also demands a closer analysis of the causal link between the hegemonic (dis-)order of financialised capitalism and environmental degradation.

Let us start with a review of the concepts of value and utility. In the aftermath of the 2007–2009 global financial crisis, there were a number of analyses which focussed on the “socially useless” nature of many features of banking and financial services,[1] with the inferred need either to outlaw such services or to tax them punitively. These analyses gave rise to a brief and active public debate about particular aspects of banking, notably about sub-prime mortgages, derivatives-trading and proprietary trading (Mazzucato 2018: 142ff) and to a longer-lasting scholarly interest by heterodox economists in the widespread predatory practices of the FS-sector (Mellor 2010; Pettifor 2017; Raworth 2017; Shaxson 2018 etc.). Within this debate, scholars have revisited the concepts of value and utility, questioning above all the dogmatic definition of value as the price set by market actors for a given commodity or service, a monetary price which represents the cost of production – factor costs – and the additional profit from the sale of that good/service. This static and atomised theory of the value, represented by an ‘exchange value’ is weakened immediately if one admits a broader set of factors of historical and social interdependence in the creation of the exchanged product/service: knowledge, skills, techniques accumulated over time, the highly complex division of labour in the process of production and sale, the role played by non-monetised domestic and voluntary labour and the fundamental social nature of capital and accumulated wealth (see, above all, Murphy, Nagel 2002) on the “myth of ownership” and the complex interdependence of “value-creation”.

It is the commodification of use-values, above all the establishment of a legal and exclusive entitlement to a resource, product, service, technique and process, that in practice neutralises any philosophical notion of a complex genealogy of value. Value – exchange-value – is coded in the legal rights of the private individual or corporation, and guaranteed by the state qua jurisdiction through the formal frameworks of the separation of powers. The Code of Capital (Pistor 2020) simplifies the administration of the (increasingly complex) division of labour within capitalist societies, even if it completely distorts the epistemological nature of value and cements the power hierarchies and inequalities rooted in the myth of ownership (Murphy, Nagel 2002). Above all it establishes the core institutions and processes for the extraction of rent from the legal entitlement of owning and controlling an asset.

A good illustration of the legal privileges and entitlement of ownership can be found more recently in what Birch and Muniesa (2020) term “the assetisation of knowledge”. In short: knowledge is not just intellectual power over nature but, when accorded the legal title of ownership, is a potential source of monopoly rent. Just as the legal enclosure of the Commons by political decree or parliamentary act established exclusive control by a landowner, and the right to the agricultural product of the surface soil and of the mineral resources below the surface, so the granting of a legal patent to a product, technique, idea or even plant DNA bestows the right to monopoly value-extraction for a regulated length of time (20 years historically). Implied, above all, in the notion of intellectual property is the sense, firstly, of the knowledge appearing ex nihilo without acknowledging the historical determinants of that knowledge – as humanity’s intellectual Commons.

The appropriation of knowledge as a commodity with an exchange-value defies the historical reality of a genealogy of knowledge, skill, discourse and reflective science; i.e. defies Isaac Newton’s honest concession: “If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants”. Mariana Mazzucato provides a convincing illustration of the illogicality/inequity of the atomised juridified extraction of knowledge for private profit, by elaborating the extraordinary advantages bestowed on research companies, who are permitted to exploit the profits of research findings that were partly or wholly conducted by state-funded institutions, processes and staff (Mazzucato 2013, 2018). She cites fairly dramatic but persuasive examples of such profiteering.

An ounce of jurisdiction is worth more than a pound of gold

(Motto of 15th Century Belgian Lawyer)

The recent COVID-19 pandemic has produced a marked increase in debates within civil society in Europe and elsewhere about “value”, specifically about the value of the work of particular, critical occupations within the health services, within social care, within the basic utility services – the fields of human activity essential to life. By the same token, attention has also been directed towards the incomes of indispensable workers and the (hitherto largely unquestioned) higher earnings of “non-essential” professions. This discourse has thus had a more pronounced, if limited, class dimension, but has been accompanied by a more intensive preoccupation on the part of political economists and other interdisciplinary social scientists in value theory. Within a general labour theory of value, the focus of these heterodox approaches has been in large measure on the role of financialised capitalism in predatory and damaging modes of accumulation where the “takers” parasitise the productive economy of “makers” (Foroohar, Shaxson), weakening the structural coherence of industrial/commercial capitalism and ushering in an intensified system of “value-extraction” (Mazzucato) and “rentierism” (Christophers, Vercellone, Monbiot).[2]

Some of the most illuminating accounts of the new rentierism consider the role that legislation and legal statute play in embedding the rights of ownership, along with the international significance of jurisdictions with differing legal privileges and opportunities. Katharina Pistor, in The Code of Capital, notes the primacy of law in the operation of a kind of logic of capital, despite the absence of a global state as coercive enforcer of that law (2020: 132ff). This “puzzle” is resolved by the dominance of the legal norms of a handful of advanced states where the rights of capital are acknowledged by an elite international community, even if there are clear differences between the legal statutes of individual states. The core truth remains: “There is no capital without law, because only law can bestow priority, durability, and universality on assets, and therefore privileges its holders. Capitalism exists because modern legal systems are built on and around individual subjective rights and put the state in the service of protecting these rights [my emphasis – JL]” (Pistor 2020: 229).

This paper attempts to build on Pistor’s wealth of insights, by stressing the particular political role played by what I term “permissive neoliberalism”, where the “permissiveness” relates to the willingness of “market radical” jurisdictions like Margaret Thatcher’s UK, Ronald Reagan’s US and other members of the OECD family to extend the property rights of (international) capital to an increasingly diverse set of assets beyond land, real estate, productive and commercial enterprises. Brett Christophers outlines the extent of state permissiveness towards new classes of capital assets in his major work Rentier Capitalism. Who Owns the Economy and Who Pays for It (2020: xxxi), some of which will be examined below.

Christophers’ examples are certainly not confined to the UK, but have been adopted to a greater or lesser degree in most other OECD states and shamefully included in “structural adjustment programmes” imposed by the Bretton Woods institutions (IMF/World Bank) on a string of less developed countries.[3] However, of central importance for this paper is the abandonment of the operational frameworks of most advanced economies established after the Second World War, most notably the primacy of public control of natural monopolies (in physical infrastructure of water & sewage services, communications networks, electricity and gas production and supply, in social housing, local and national public transport). Many of these natural monopolies and social institutions were subject to a wave of privatisation measures. These permissive reforms were delivered ideologically in terms of “market efficiencies” that could be applied to the bureaucratic “behemoths” of state organisations. However, Christophers and others (Monbiot; Vercellone 2010) assert persuasively that the privatised monopoly was unsurprisingly a colossally effective vehicle for the extraction of monopoly rent. What is important at this stage in the paper is that the conferring of legal title onto such vehicles was a core function of permissive neoliberalism; of equal importance is the fact that the (fraudulent) narrative of market efficiencies was given active, strong support by the global corporations that dominated the mainstream print and broadcast media. Heterodox scholars, on the other hand, saw in this coalition of global economic elites and national political and, yes, academic elites increasing evidence of oligarchic power, frequently popularised under the banner of “the economics of the 1%” (cf. Weeks 2014 etc.). The key indicators for heterodox observers were the reversal of the trend in the first three decades after WW2 towards a more equitable distribution of national income (qua wages ratio and profit ratio) and the marked widening of income disparities within leading advanced economies, most notably the UK and the US (in terms of both the Gini Coefficients of Income and Wealth Distribution, and the specific favouring of the top percentiles of the income distribution).

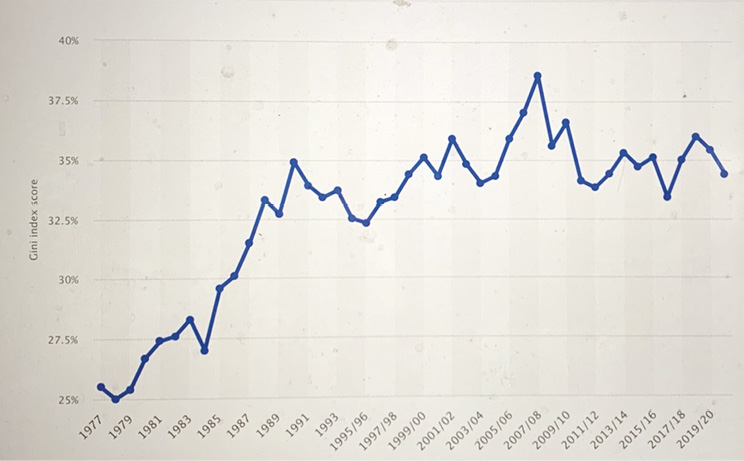

Figure 1. The Gini Coefficient of Income in the UK 1977–2020

Source: Statista (accessed: 8.12.2022).

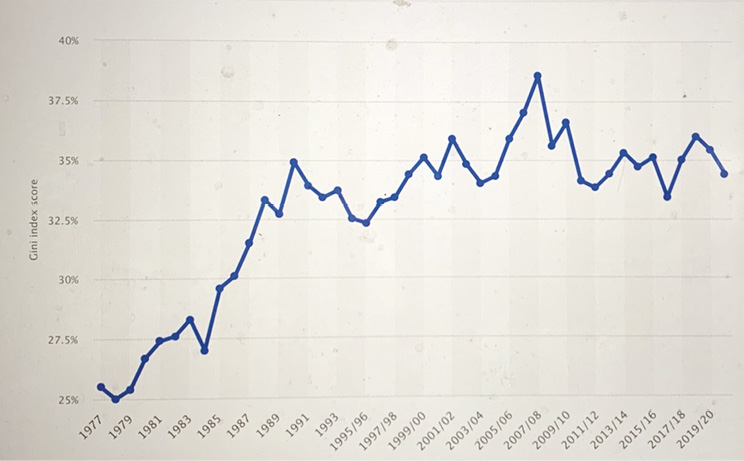

These and similar charts are well-known: declining levels of income inequality to 1955, stabilisation at a lower level between 1955 and 1980, followed by a marked increase in income disparities measured by Gini and decile/percentile distribution.[4] Again, the legal facilitation of this trend-reversal is central to the argument here: deregulated capital market controls and re-regulated, restrictive controls on employment and trade union rights formed the foundation, flanked by the legislated imposition of budgetary austerity, of cuts to Corporation Tax rates (see below) as well as a rise in structural unemployment.

UK market-radical libertarianism was thus embedded in legal reforms to the rights of capital (enhanced) and those of labour (reduced) and administered judicially over four decades of seamless neoliberal hegemony (including 13 years of New Labour governance).

Law is thus the indispensable buttress to the power of capital and to an altered balance of power in employment relations. The combination of permissive and authoritarian neoliberalism became the foundation of economic governance in Britain. Of particular relevance in the context of this paper: as value-extraction by the powerful increases, so the need to limit the legal recourse to claims against state and elite on the part of subaltern groups grows, i.e. the need for the neoliberal state to impose authoritarian controls. A new hegemony was born, supplanting the welfare “consensus” of post-war Keynesianism.

Figure 2. Supply-Side Tax Relief for Capital (Corporate Profits)

Source: World Tax Database (accessed: 8.12.2022).

Legislation thus facilitated the wave of commodification/assetisation which, in the first instance, converted public goods as use-values into tradable exchange values, but also set in motion a further wave of derivative “products” which, at first and second glance (!) lack any perceivable use-value, except to the trader. It is the growth and scale of both the permissiveness of legislation in the advanced group of OECD economies that increased the threats to that traditional symbiotic relationship of industrial/commercial capital with finance capital, generating the global neoliberal disorder of predatory financialised capitalism which, in Hudson’s words is “killing the host”. The blindness of both global elites and their mainstream economic advisors[5] to this threat is summed up neatly by Rana Foroohar, author of Makers and Takers (2016) and “Financial Times” journalist, in a recent commentary on the May 2022 World Economic Forum in Davos:

The point here is that western business leaders have for many years blamed governments for not delivering on basic public services. But blanket privatisations and the neoliberal race to the bottom for offshoring both wealth and labour has ensured that it’s harder and harder for them to do so (Foroohar 2022).

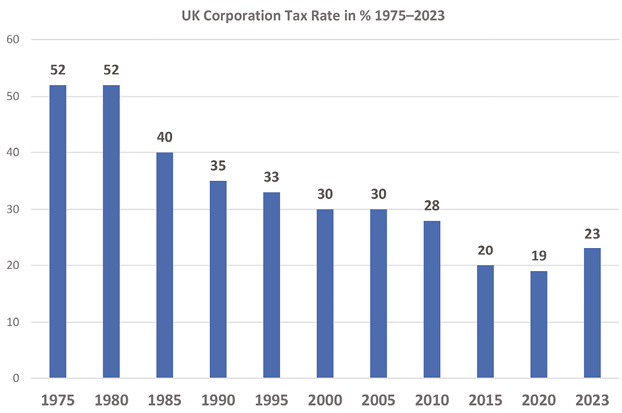

Foroohar’s understated scorn for the inability of economic and political elites to reflect on the comprehensive failure of neoliberal, supply-side policies and the statistical evidence of that failure, is broadly shared by heterodox economists and political economists who in turn have expressed their bewilderment about the “triumph of failed ideas” (Lehndorf), the “return of depression economics” (Krugman) the pursuit of “Fool’s Gold” (Tett 2010) or the onward march of “mad money” (Strange). There is no need in this context to rehearse the refutation of neoliberal “theory” beyond reference to the simple comparison of a rising profit ratio and a declining investment ratio, where the supply-side boosting of profits was supposed to result in a corresponding increase in investments, generating growth, higher real wages and higher state revenue, but in fact achieved an accelerated decline in private investment.

Figure 3. Profits Ratio and Investment Ratio (as % of National Income) Advanced Economies 1980–2005

Source: Reversing the neoliberal deformation of Europe, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/262911285_Reversing_the_neoliberal_deformation_of_Europe (accessed: 8.12.2022).

The failure to reflect on the screamingly obvious contradiction between the promise and the real outcome of the four desperate decades of neoliberalism is a mystery which will be examined in the second part of this paper. The conclusion of this section underlines both the crucial role of permissive legislation, tolerant of the rampant abuse of national and global conditions, and the resulting astonishing enrichment of the economic and political 1%/0.1% and the resultant widening inequalities in leading economies. The economic, social, political and fiscal costs of this inequality must be included on the negative side of the balance sheet – as “negative externalities”, even if their structural determinants are decidedly endogenous, informed as they were by a theocratic faith in the market allocation of resources.

It is instructive to note that Adam Smith, David Ricardo, Karl Marx and John Maynard Keynes all viewed rent as parasitic in nature (see Mazzucato 2018: 72f; Christophers 2020: xxif); rent can be defined, in their shared view, as “payment for monopoly control of an asset” (Christophers 2020: xxif). The standard view of rent as payment to a landowner by a tenant farmer has, with the growing complexity of the division of labour, been extended to encompass a growing number of “assets”, the legal ownership of which entitles the owner to extract a tribute/price even when that owner contributes nothing to the tenant’s value-creation. Rent is the exclusive privilege of a legally embedded property entitlement and, as such, was defined as “unearned income”, with the implied moral judgement of “undeserved” privilege, as associated with usury. Mazzucato, in her account of value-extraction, observes that “Ricardo and Marx refined the theory of rent to make it clear that rent is income from redistributing value and not from creating it” (2020: 55). Because the monopolist’s legal privilege tends to generate higher rates of return/profit than enterprises in relatively competitive markets, it is plausible to infer a natural tendency towards monopoly among many participants in capitalist markets (viz. Wallerstein etc); this was certainly the logic of attempts within advanced states over the last century-and-a-half to introduce legal mechanisms to control the power of cartels, trusts and true monopolies and to introduce/maintain public control of certain natural monopolies (water & sewage services, power production and distribution, transport systems, gas services, policing and prison services, social housing etc) to prevent the excessive value-extraction that concentrated economic power affords. Even after the weakening of social rentierism through the combined forces of inflation and recession in the 1920s, the persistent trend towards sectoral and conglomerate concentration strengthened state efforts towards monopoly controls within both statist/Keynesian and “ordo-liberal” policy regimes. This continued over three decades after the end of the 2WW against the background of a broad acknowledgement within the policy community that there was a causal link between the social inequalities of the 19th and early 20th centuries and the economic and political disorder of the first half of the 20th century. The relative success of this policy consensus is arguably demonstrated by the favourable trend of the Gini Coefficient/labour share of national income noted above.

It is a grim irony of economic history that this consensus was broken by the abuse of monopoly power in the shape of the OPEC cartel and the global economic disorder of the 1970s. The political nature of the oil cartel arguably strengthened the anti-Keynesian/anti-statist tendencies among academic economists and their allies within economic and political elites. With the support of monetarist institutions like the Bundesbank and the Federal Reserve, the state forces within the OECD that had presided over les trentes glorieuses were overwhelmed by a new (but infantile) consensus that blamed state, high taxes, high indirect labour costs and trade unions for the stagflationary chaos – infantile, not because Welfare Keynesianism was faultless (which it clearly wasn’t). It was because stagflation was essentially caused by an exogenous shock, informed by a broad set of global economic and political factors, including critical post-colonial developments.

Irony or not, the relatively rapid transition to a new neoliberal orthodoxy set in motion a wave of legal changes to the constitutional and statutory foundations of post-war statism, which don’t need to be rehearsed here (cf. Harvey, Piketty, Mazzucato, Altvater, Huffschmid etc.). Alongside the deregulation of employment law, of exchange controls and the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates, it was the extensive programmes of privatisation within most advanced economies and in many debt-burdened developing economies that ushered in the new era of rentierism.

The UK is a good example of the privatisation of major public sector assets, framed within a narrative of public sector “inefficiency” and the unquestioned cost efficiencies of private ownership and the benefits of competition. The core of this narrative was specious, as a brief glance at the list of privatised public enterprises below indicates; above all, the vast majority of companies in the energy sector, the transport sector, water services, telecoms, postal services were and, with the exception of telecoms,[6] remain natural monopolies.

| Energy | Industrial Manufacturing | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| British Petroleum | 1979–1987 | Jaguar | 1984 |

| Enterprise Oil | 1984 | British Shipbuilders | 1985 et seq |

| British Gas | 1986 | Rolls Royce | 1987 |

| British Coal | 1994 | British Steel | 1988 |

| British Energy | 1996 | AEA Technology | 1996 |

| British Aerospace | 1981–1985 | ||

| Transport | Other | ||

| National Freight Corp | 1982–1985 | Water Services | 1989 |

| British Airways | 1987 | Electricity | 1990 |

| British Airports Authority | 1987 | National Power | 1991 |

| Railtrack | 1996 | Powergen | 1995 |

| National Air Traffic Services | 2001 | British Telecom | 1984–1993 |

| Train Operating Companies | 1996–1997 | Cable & Wireless | 1981–1985 |

| Trust Ports | 1992–1997 | Royal Mail | 2013–2015 |

The pricing power of monopolies, the reason for earlier political preferences for collective ownership, was/is admittedly subjected to a set of regulatory monitors with the power to limit price-profiteering, but studies of UK privatisation demonstrate consistently a) that rates of return rose very significantly after privatisation[7] and b) directors’ incomes – including bonuses – rose dramatically; in the case of water company bosses, annual average income in 2018 stood at £1.1 million. Dieter Helm (as cited in: Laville 2020) concludes that “what we have seen is a complete regulatory failure to control the companies”. The key issue here is not the quantitative damage of “the delusions of privatisation” in the UK (cf. Funnell, Jupe 2009 etc.) but merely to note the critical contribution to commodification/financialisation represented by the irresponsible disposal of so many state monopolies by successive libertarian (Conservative) regimes in Britain. The evidence of a monumental scale of rent-extraction is clear. What needs to be stressed is the signalling by Thatcherite “reformers” of a new permissive climate for the naked pursuit of more favourable “rates of return” (ROR) in the purchase and disposal of assets. In conjunction with the “Big Bang” liberalisation of financial markets in 1986, the “selling-off of the family silver”, of hitherto ring-fenced public goods opened the gate to the wholesale plunder and commodification of other public assets.

In The New Enclosure, Brett Christophers also documents the, largely unnoticed, disposal of public land since Thatcher’s accession to power in 1979 – land previously held by public enterprises and public authorities. Excluding the extensive holdings of the water utilities, this “new enclosure”[8] accounted for 1.6 million hectares or 8% of the total UK land mass in less than four decades. There was both a commodification effect, with land prices multiplying some four-fold after 1975 (Christophers 2018: 289) and a volatility effect which mirrored the particular financial crises of 1987 and 2007–2010, contributing in no small measure to the inordinate rise in the cost of housing – both owner-occupied and rented. Parallel to this assetisation of land by legal transfer to private ownership, the disposal of (affordable) social housing under the “right to buy” programmes (Ryan-Collins et al. 2017: 90f) saw both the virtual disappearance of local authorities’ housing stock and the active promotion by government and mortgage-lenders of the narrative home-ownership as investment, employing a range of fiscal and ideological inducements. 2.6 million Council Houses have been sold since 1980, generating a whole new political economy of housing according to Ryan-Collins et al. (2017: 91ff) and, arguably, a new mindset among householders which approves or tolerates a “speculative house-building model”, itself generated by the accumulation of “land-banks”, acquired in part through the disposal of public land (see also: Foster 2018).

It is argued persuasively by many heterodox economists that the commodification/assetisaton/financialisation of land and private housing has, predictably, contributed significantly both to the global financial crisis of 2008, through the securitisation of high-risk sub-prime mortgage-derivatives, and secondly to the more recent penetration of hedge funds and private equity companies into private housing as a supposedly reliable source of higher rates of return. Gabor and Kohl (2022) provide an invaluable guide to this potentially destructive trend of “housing as a financial asset”. The marked increase in the real estate holdings of PE companies like Blackstone (to $230 billion) underlines this more recent predatory phenomenon which exploits the human need for shelter as a human right, but from the perspective of the logic of capital and rent-seeking.

The history of financial derivatives of housing and other real estate mortgages is instructive, as outlined so convincingly by Pistor, who points out above all the tenacity of derivatives (as fictitious values) in the behavioural responses of both investors and state/ parastate institutions:

“One would think that what a legislature has given [legal sanction for derivative “products” – JL] it can also take back. But this proved more difficult, not the least because of the size of the global derivatives markets” (Pistor 2019: 150). To this short – to medium-term impediment of the heavy commitment of financial markets to derivatives, Pistor adds the critical feature of the global competition between financial centres for the privilege of hosting the £ trillions of footloose capital in search of favourable returns. Indeed this conundrum underpins so much of post 2008-crisis economic and political history, explaining the frustrating failure of the international community to counteract the pernicious activities of “casino capitalism” to any measurable degree.

The above brief discussion of the financialisation of real assets as vehicles for rent-extraction led of necessity into the more recent feature of fictitious “assets” whose market legitimacy/legal coding becomes fatally entwined with the vast transactional network that makes up the whole global financial sector. It is the sheer speed and scale of the expansion of fictitious investment “products”, marketed by trusted investment banks, given top ratings by esteemed ratings agencies, lauded my financial journalists and monitored by complacent regulatory institutions that explains the sudden and extraordinary traction of casino capitalism and the hegemony of “mad money” and “fools gold” (Strange 1986, 1998; Tett 2010). The second half of this paper will seek to explain the mindset that maintains the delusions of this hegemony; what counts here at this stage is the political and legal ecosystem which permitted and promoted the descent into madness and waved through the Emperor and his vast entourage as they dominated the ridiculous pageant in their naked finery.

There is no space to describe in any detail the now permitted rent-extraction from all the categories identified by Christophers (Table 1). Suffice it to say that it involved in large measure the unprecedented “enclosure” or capture of a “knowledge commons” (Pistor etc.), where corporate or individual entitlement to the exclusive exploitation of a natural resource (coal, minerals, rare earths, water, forests, seabeds) is sealed and coded legally and, in extreme cases involve the patenting of natural phenomena (plant DNA, human DNA, bacteria) (Pistor 2020: 108ff; cf. Durand 2017: 119ff).

With permissive neoliberalism’s facilitation of monopoly rent-extraction, a key social protection against the economic abuse of market power was sacrificed; the parallel weakening of trade unions and workers’ bargaining power through reforms of labour law, predictably raised levels of inequality and poverty. Crucially, for the subsequent march of financialisation, the rates of return from monopoly income streams generated a more general expectation among investors, notably investment banks, of higher yields throughout the economy. However, because the declining wage share of national income reduced the effective demand of private households, the incentive for enterprises to invest in new plant and machinery was correspondingly reduced, breaking the first link in the chain of supply-side logic: higher profits did not trigger higher investments (Figure 3). Successful enterprises found themselves with higher and growing reserves of capital which simply joined the capital reserves of oil-exporting countries and existing offshore reserves in a worldwide “hunt for yield”, ideally above-average returns on industrial and commercial stock. The preconditions for the dramatic expansion of “casino capitalism”, of the self-referential, socially “useless” recycling of financial assets (habitually and shamefully termed as “products”) were created. The “decoupling” of financial (unproductive) markets from the productive markets (that contributed in some way to increasing the sum of human welfare) proceeded in short order, mediated in particular by the main global financial centres, notably the City of London and its “archipelago” (Ogle 2017) of “crown dependencies” and associated overseas territories: tax havens and secrecy jurisdictions.

The “archipelago” was already well established under the protective arm of the British State in the 1950s and 1960s (Sagar et al. 2013: 107ff; Ogle 2017) and fed initially by the modest but growing market in globally tradeable Eurodollars (Bullough 2019: 36f; Mazzucato 2018: 112f; Shaxson 2018: 55–59). While the Swiss may wish to claim the honour of inventing the “tax haven” phenomenon, the sheer geographical spread and the number of constituent jurisdictions has made the UK’s parenthood fairly evident. Yes, there has been a clear expansion of the global offshore world of secrecy jurisdictions and tax havenry, but the City of London’s network still figures among the most egregious, according to the Tax Justice Network, with four of the top 10 worst offenders, six if one adds Hong Kong and Singapore (as clear members of the archipelago) to the list:

| 1. | British Virgin Islands (British Overseas Territory) |

| 2. | Cayman Islands (British Overseas Territory) |

| 3. | Bermuda (British Overseas Territory) |

| 4. | Netherlands |

| 5. | Switzerland |

| 6. | Luxembourg |

| 7. | Hong Kong |

| 8. | Jersey (British Crown Dependency) |

| 9. | Singapore |

| 10. | United Arab Emirates |

Source: Tax Justice Network, https://taxjustice.net/press/tax-haven-ranking-shows-countries-setting-global-tax-rules-do-most-to-help-firms-bend-them/ (accesed: 8.12.2022).

It is important to introduce secrecy jurisdictions and tax havenry into the narrative here because they were important if not indispensable pre-conditions for the successful expansion of financialised capitalism, inasmuch as they supplied the “plumbing” of a global network of interrelated locations for the discreet and opaque processing of $ trillions away from the state authorities in 200 or so nations in the visible, official global politico-economic order; the processing served predominantly to protect the assets of private corporations and “high net-worth individuals” (HINWIS) from the tax or police authorities of the world’s states.

The existence and flourishing of tax havenry involves a set of fundamental contradictions, involving above all its coexistence within a complex system of both national and international law which is rooted in the commitment to and trust in the proper functioning of the rules of trade, payments and taxation for the world’s 7.87 billion population. The IMF, the World Bank, the BIS, UNCTAD, the OECD family of advanced economies are all signed up as opponents of tax evasion and money-laundering. However, since the declarations by G20, G7 and EU leaders to wage war on tax havenry in the wake of the Global Financial Crisis, little progress has been made beyond warm statements of approval for the OECD’s BEPS (base-erosion and profit-shifting) initiative. It is reported that significant proportions of global trade and investment are still channeled through secrecy jurisdictions (Hebous, Johannesen 2021). The revelations of the Panama Papers, the Paradise Papers and the Luxleaks by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, by Global Witness, be the Tax Justice Network and others have generated considerable public attention, but with little in the way of follow-through by politicians.

It is in part plausible to argue that the existence of over 200 separate jurisdictions and of marked disparities between their respective bodies of tax and commercial law encourages both the practice of tax and regulatory arbitrage by corporations and corresponding efforts by jurisdictions to attract inward investment, which helps to explain the slow progress to act on multilateral pledges, for example to pursue the OECD’s BEPS initiative. At the other end of the explanatory spectrum one might even be tempted to support conspiracy theories linking global economic and political elites in a cynical kleptocratic programme of plunder and concealment. This behavioural dimension will reappear in the second half of this paper. What, however, seems evident at this stage is that permissive neoliberalism involves not just a flawed faith in market efficiencies and the sanctity of ownership, but also a permissive approach to policing and compliance, where tax evasion and money laundering simply become second order political priorities, especially when the actual administrative capacity of respective jurisdictions has been reduced through staff cuts to departments responsible for policing malfeasance and driving compliance.[9]

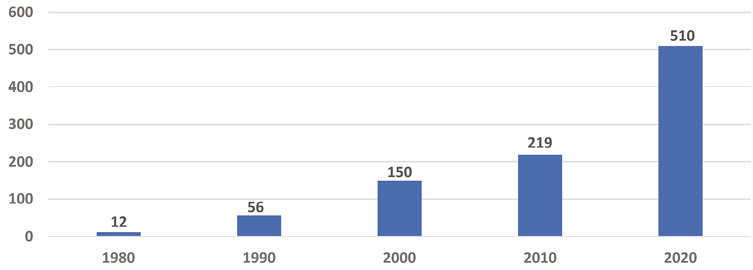

Figure 4. Global Financial Assests, $ Trillions

Source: McKinsey.

The remarkable growth of total global financial assets from $12 trillion in 1980 to $510 trillion in 2020 – or from 106% to 602% of global GDP – was thus arguably fed by a combination of factors: the core hub-and-spoke structure and transactional processes of the UK’s archipelago of secrecy jurisdictions, secular trends of increasing capital concentration, the wave of privatisations adding to monopoly incomes streams, inflated expectations of higher yields (compared to those of traditional production/distributions circuits), growing volumes of vagabond capital, the new policy orthodoxy of permissive neoliberalism and, crucially, the wave of kleptocracy and money-laundering that followed the break-up of the Soviet Union and its satellite state system; that these interests of post-communist kleptocrats were serviced by the legal and accountancy expertise of the City of London was arguably a critical accelerator of the new hegemony of finance capital and its attendant disorder.

“Offshore” is very much a “metaphor we live by” but a metaphor, the perversity of which is still not understood by most members of civil society throughout the world. Its core paradox is that offshore is both somewhere and nowhere, registered in shell companies at 29 Harley Street, London, or 1209 North Orange Street, Wilmington, Delaware or Ugland House on the Caymans,[10] but managed in other jurisdictions – predominantly jurisdictions with stricter tax and regulatory controls. Offshore is little more than a flag of convenience for the “beneficial owners” to avoid/evade tax and regulatory liabilities in their actual location(s) of economic activity: offshore represents “the strange hidden space between capital and the state, the secret realm at the ambiguous heart of Western modernity, the ever-kept secret contradiction between the individual and the authority of the law” (Brittain-Catlin 2005: 6).

The inescapable conclusion from any survey of the extensive literature on tax havens and secrecy jurisdictions is that they provide a “criminogenic” environment (Christensen 2011), in which key financial centres in the first world, above all the City of London, were and continue to be complicit.[11]

Once the core ambition of statehood to promote use values and human welfare is abandoned through privatisation and the assetisation of everything, the notion of the political regulation of the new circuitry of global capital becomes subordinated to the promotion of growth through the accumulation of exchange value. Anything goes, as long as it can be counted on the plus-side of national accounts, and yields from (higher) turnover taxes and the taxation of the ballooning profits of onshore financial corporations are adequate.[12] This delusionary point of departure of neoliberal orthodoxy ignores, above all, the negative side-effects of the misallocation of capital, of time and of humanity’s creative energy, where the social and environmental well-being of the overwhelming majority of “humanity” is under unprecedented threat. High frequency trading is a perfect and disheartening example of this misallocation.

The erosion of physical market-trading in the world’s security markets was driven by major technological advances in online trading-systems, by the globalisation of financial services and the deregulation of international exchange controls, and in the new century by the growing frequency of severe market fluctuations/full-blown financial crises. The process was further accelerated by the absolute interruption of physical commercial life by the COVID-19-pandemic. Within this gradual digitalisation process, there was a discernible trend towards a shortening of the life-span of security portfolios, as noted by Huffschmid (2002: 40ff). He notes that the global average life-span for share-holdings had fallen from 19 months in 1980 to just 6 months in 2000. The trend since the turn of the new millennium has been dramatically accelerated, above all with the appearance of the phenomenon of High Frequency Trading (HFT); this was decisively driven by the abandonment of regulatory obstacles to the early disposal of shares, for example in the suspension of Capital Gains Tax for short-term holdings by the Thatcher government in the UK in 1982. This and similar measures in other OECD countries shifted the function of share-ownership and stockbroking away from the detailed assessment of the long-term prospects of a publicly listed company, and potential gains from extensive holdings, to a speculative game, rooted increasingly in sophisticated algorithms which were able to take advantage of short-term fluctuations in share-prices in multiple financial centres, by generating minute but critical differences between a bid-price and a subsequent (high) sale price; the key objective was/is to accumulate millions of such sales in as short a time as possible. ‘Added value’ is represented solely by the surplus of revenue from myriad transactions over costs. It is the crassest example of the triumph of exchange-value over utility/use-value which is made even more surreally absurd by the reported technological “race” for ever faster transaction margins of 0.000005 to 0.000010 seconds; the process has been endearingly dubbed “sniping” (shooting a victim from a concealed position) (Stafford 2020), the commercial tactic more arcanely as “latency arbitrage”!![13]

Defenders of HFT suggest that some of its practices “bring benefits such as liquidity and improved price discovery to financial markets” (McNamara 2016; see also Picardo 2022). Both assertions are unconvincing, to say the least. The liquidity of financial markets has arguably been chronically excessive for several decades, culpably boosted by recent spates of “quantitative easing” by central banks, but driven in the main by the successful “privatisation of the production of money” through global debt markets (Keen 2017; Pettifor 2017; Mellor 2010). As Figure 4 above shows, the ratio of global financial assets to global GDP grew from rough equivalence in 1980 to a staggering 6:1 in 2020. By the same token, the volume of global Forex transactions in 1970 matched global trade transactions; by 2021 trade accounted for a mere 1.3% of Forex turnover.[14] The ballooning of liquidity has, as noted above, not only failed to boost real, productive investment, but generated a further intensification of socially useless speculation in the decoupled global casino, sucking in above all the financial reserves of enterprises in the “real economy”, attracted as these are by the artificial rates of return of the financial services “industry”.

The consistent abuse of the term “industry” by both traders and mainstream reporters of their activities is perhaps most grotesquely represented by the following statement in the financial press, answering the question “What is the biggest opportunity for growth in the High Frequency Trading Industry in the US?”:

Investor uncertainty is an indicator of stock market volatility. More volatility on exchanges makes more money available for high-frequency traders because they generate revenue and profit through very fast-paced purchases and sales. In 2020, investor uncertainty is expected to increase sharply, representing a potential opportunity for the industry (Ibis World).[15]

The political toleration of a fundamentally predatory business model, exploiting the “latency” of transactions measured in nano-seconds, is one crass (and unpardonable) example of several culpable features of permissive neoliberalism. Another example has to be the short-selling wheeze beloved by hedge funds.

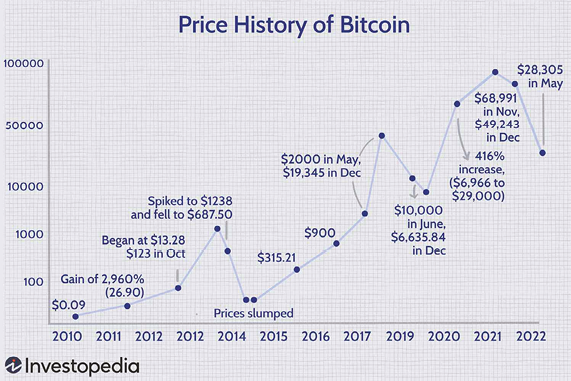

One of the most egregious examples of financial innovation has to be the emergence of the market for crypto-currencies. There are wide disparities in assessments of the size of crypto markets. Most reliable estimates would suggest a peak valuation of some $3 trillion by the autumn of 2021 (Time, Statista). Opinions diverge as to the utility of these “assets” from a wholehearted approval by libertarians, viewing them as viable substitutes for sovereign state fiat currencies, to a wholesale rejection of cryptos as a “Giant Ponzi Scheme” (Mortavazi). The phenomenon of Bitcoin is only thirteen years old; its dubious provenance derives from the very combination of the image of a material means of exchange (coin) with the smallest digital unit, the bit, which lacks any materiality. It is essentially a fictitious unit, available for purchase and sale within the imaginary space of the web-universe. It began life in this fictitious space, for sale at $1 per unit of the “cryptocurrency”.

In contrast to the coins, notes and the officially recorded financial assets denominated in a sovereign currency and guaranteed by one or more central political authorities, Bitcoin and its virtual clones (Ethereum, Dogecoin, Binance Coin, Monero and 17 others) operate within decentralised “blockchains” on virtual “ledgers” that rely not on any proper collateral security (whatever “pegged” cryptocurrencies might claim) but on the simple faith of the investors. The 13-year history of Bitcoin which saw astonishing fluctuations in market price from tens of dollars in the early years to $68,991 in November 2021, should of itself give pause for thought, as should the subsequent slump to under $30,000 in May 2022 (August 2nd: $22,947). There have, of course, been alarm-calls from a number regulatory authorities (European Securities and Markets Authority, European Central Bank, the IMF, the UK Financial Conduct Authority), with outright bans in China. Other key institutions have produced more ambivalent assessments, including the Federal Reserve, the BoE and the World Bank, while several countries have either sanctioned the use of cryptos (Panama) or tolerated their widespread use (Pakistan, Nigeria, South Africa, Brazil, Argentina, Kenya and Vietnam). Rishi Sunak, former UK Chancellor of the Exchequer/ Finance Minister, has even expressed the policy ambition of making the UK “a global hub for crypto” (“Financial Times” 2022, April 5).[16]

Figure 5. Fraudulent and Volatile: Unsuitable and Unnecessary

This lack of a unitary response from policy-makers and organisations in the international community of states is a clear obstacle to a timely disabling of the destructive potential of cryptos. Above all, the very decentralised nature of crypto blockchains and their anonymity make them both immune to international monitoring, policing and enforced compliance, and therefore very attractive to organised crime. Jon Cunliffe, a BoE deputy governor for financial stability, noted pithily that “the volatility of their value makes unbacked crypto-assets generally unsuitable for making payments – except for criminal purposes”.[17]

The reason for both the stratospheric appreciation of Bitcoin and its volatility is to be found in its essence: as a vehicle of speculation – and predation – beyond the usual jurisdictional controls. It does seem to resemble a giant Ponzi scheme with the potential for colossal losses, particularly for investors who can’t afford it, and for a corresponding destabilisation of financial markets. Given the surprisingly large numbers of citizens in both advanced and emerging states that have been drawn into the gravity pull of cryptos,[18] destabilisation looks more and more likely in the short term. Sceptical voices, while increasing, are still being drowned out by the desperate faith that sustains the participants in this variant of the Emperor’s New Clothes. Purely at the level of assessing the utility of these fictional assets, I find myself in full agreement with the following assessment by a Financial Services insider:

I’ve never seen a scam of such proportions as Crypto. It has multiplied and thrived like an alien virus, spawning its own ecosystem of tokens, stable-coins, NFTs, digital assets. It’s fuelled a whole industry, community and belief system in crypto – and 99.9% of the participants don’t seem to get it, and just don’t know how completely they are being scammed (Blain 2022).

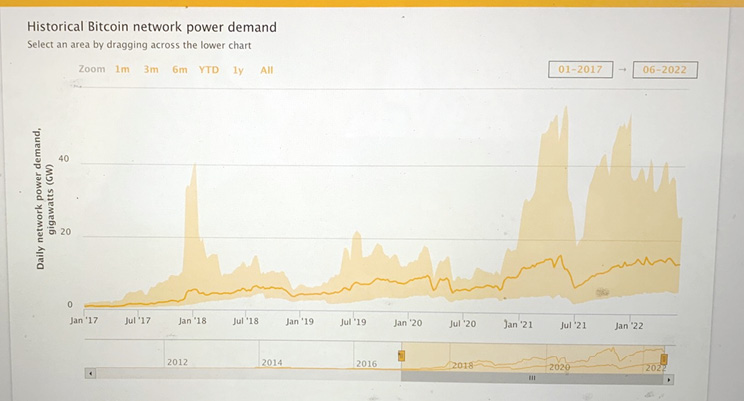

Figure 6. The Bitcoin Madness 2017–2022

Source: The Cambridge Bitcoin Electricity Consumption Index, https://ccaf.io/cbeci/index (accessed: 8.12.2022).

Once the utility of these fictitious financial innovations are reduced to the level of criminality, predation and fraud, it is probably more important to point to the real, materially destructive feature of cryptocurrencies, namely the colossal toll it exacts in the power usage incurred in the process of “bitcoin-mining” (the perverse misnomer for the algorithmic game of chasing encrypted new blocks of the “currency”). Cryptocoin-“mining” consumes 0.5% of annual global energy consumption, which puts it currently above the total electricity consumption of the Netherlands and 187 other countries!!!! The algorithmic guesses are known as “hashes”. One recent estimate suggested a hash-rate of 200 quintillion per second (Howson 2022). The Cambridge Bitcoin Electricity Consumption Index (sic) has been tracking the colossal environmental footprint since January 2017, providing sufficient evidence for responsible political authorities to outlaw the cryptocurrency madness for environmental reasons alone.

The reluctance of regulatory authorities to neutralise the economic and ecological threat of cryptocurrencies is culpably irresponsible, and symptomatic of the permissive mindset that neoliberalism has helped to “trickle down” into the darker recesses of the financial services sector. Perniciously, permissive neo-liberalism provides legal protection to its elaborate fantasy-innovations, no longer anchored in any conceivable code of ethical or social responsibility. On balance the judgement that “bitcoin is worse than a Madoff-style Ponzi scheme” (McCauley 2021) would seem both correct and applicable to the whole sorry ecosystem of crypto-fantasists.

There is no point in beating about the bush. The evidence above should be sufficient to give all those interested in the survival of humanity pause for thought – at the very least. The destructive contradictions of capitalism were already identified in the 19th century. The trend towards capital concentration and centralisation and its widespread distortions of “market efficiencies” is evident everywhere: monopolies, monopsonies, oligopolies, oligopsonies, global corporations acting as strategic gatekeepers in the material and financial supply-chains. This has been all too evident in the string of crises facing humankind in recent decades, most acutely in the current European war.

Concentration pre-programmes inequality, but has been incontrovertibly compounded by permissive neoliberalism: a) facilitating and legally embedding ownership rights and b) through benign neglect of criminogenic arrangements and criminal activity on a colossal scale. Kleptocracy only works with the active or passive cooperation of global financial institutions and networks (Burgis 2020; Bullough 2019, 2022; Shaxson 2011, 2018; Brittain-Catlin 2005).

Wilkinson and Pickett, together with the Equality Trust and many others, have demonstrated the sinister correlation of levels of inequality with levels of social and economic dysfunction: the more unequal a society, the higher are the levels of crime, murder, imprisonment, poor health, teenage pregnancies, infant mortality, mental illness, life expectancy, obesity and much more (cf. Wilkinson, Pickett 2010, 2019).

Permissive neoliberalism, at the very least, tolerates corruption – through weak regulation, through lax tax rules, through half-hearted monitoring, through lower levels of staffing for pursuing non-compliance. In reality (beyond this minimum measure) permissive neoliberalism arguably promotes corruption through specific channels, programmes and procedures:

Government practice of this kind in the UK, and elsewhere, nurtures a culture of benign neglect and “pragmatism” in a world increasingly characterised by location competition, tax and regulatory arbitrage and associated beggar-thy-neighbour policies. This arguably sits well with the narrative of market competition and virtuous, hard-working individualism, combined with a narrative which demonises state interventionism, citing acknowledged examples of tyranny and inefficiency. These narratives, typical of the political and economic elites of the late 20th and early 21st centuries, have had a profound effect on public discourse concerning society, economy and politics, critically mediated by print and broadcast organisations and – in the case of economic analysis – dominated by a complicit academic research establishment. The latter is both fiercely resistant to self-reflection outside the narrow parameters of neo-classical orthodoxy and, as a result, heavily dependent on mathematical modelling. The heterodox demand for an interdisciplinary, multidimensional approach to economic analysis stressed the utter inappropriateness of this “autistic” approach to a much altered global political economy beset, as it is and remains, by factors that mainstream orthodoxy habitually categorized as externalities. Kate Raworth’s bold attempt to internalise these externalities – notably environmental and distributional – used the metaphor of an inclusive analytical “doughnut” to describe the embedded economy in its dynamic complexity.

Explaining why such a persuasive account is still fiercely resisted by supply-side and monetarist orthodoxy requires more than a bemused shrug of the shoulders. My tentative hypothesis is that the elite narratives of financialised capitalism are informed by a hyper-individualised psychopathy which justifies inequality through a distorted lens of self-interest. This lens acknowledges only exchange-value and the primacy of short-term parasitisation of economic relationships, with scant regard to any evidence that it might be killing the host, and itself in the process. Within this hypothesis, I would place particular stress on the role played by the particular sociopathic features of toxic masculinity, with its characteristic absence of empathy.

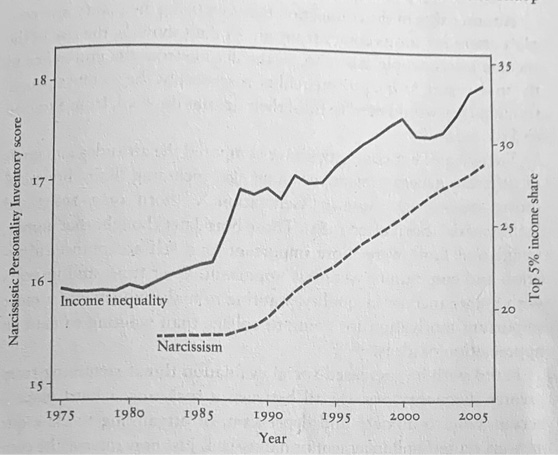

We can distinguish between explicit approval of the benefits of inequality (Gilder’s “enriching mysteries”), arguments in support of meritocracy and individual deserts, propositions asserting the specific advantages of reducing the top marginal rates of taxation for investment, innovation and growth (Laffer) and implicit judgements of extreme self-worth associated with Narcissistic Personality Disorder. In The Inner Level, the sequel to The Spirit Level, Wilkinson and Pickett (2019) present persuasive evidence of “self-enhancement bias” (Wilkinson, Pickett: 64) and a “narcissism epidemic” (Wilkinson, Pickett: 68ff), the latter derived from research by Twenge and Campbell (2009):

Figure 7. College Students’ Narcissistic Personality Inventory Scores over Time

Source: Wilkinson & Pickett 2019: 69.

We had predicted that narcissism and self-enhancement would be related to greater inequality because inequality makes social status more important. Where some people are ‘worth’ so much more than others, we judge each other more by status. Narcissism is the sharp end of the struggle for social survival against self-doubt and a sense of inferiority (Wilkinson, Pickett 2019: 69f).

Figure 7 clearly indicates an increase in levels of narcissism parallel to the increase in inequality, measured by the rise in the share of national income enjoyed by the top 5% of the population. Other correlations – with physical appearance, mental illness and dependence on medication – are also revealed in The Inner Level. In the context of this paper it is the rising sense of entitlement that characterises the narcissistic personality, along with a lack of empathy, “too high a tolerance for risk in business” and a reduced ability to work in groups. As Wilkinson and Pickett note: “Narcissism is another consequence of the ‘each against all’ logic, of the way inequality replaces co-operation with status competition” (Wilkinson, Pickett 2019: 74). A decisive piece of evidence, supporting my correlation of financialisation and predatory psychopathic behaviour, is provided by the 2010 study by Babiak, Neumann and Hare on Corporate Psychopathy: Talking the Walk which concluded that up to 20 percent of all Chief Executive Officers are psychopaths, correlating with similar studies of convicted offenders in prison.[20] Wilkinson and Pickett invoke the Orwellian view of “psychopaths at the top” in a thoroughly persuasive way; this chimes with the view of the psychologist, Steve Taylor, in his disturbing invocation of the notion of “pathocracy” (Taylor 2021):

The frequency and ease with which, people with psychopathic and narcissistic traits rise into positions of power suggests deep-rooted problems with our social institutions and values. These encourage competition and selfishness and devalue compassion and empathy, enabling people with ruthless amoral traits to thrive, and facilitating the development and expression of such traits.

In the same way that corporations can be brought to their knees by the behaviour of a small number of disordered individuals in high positions, our whole societies – and the world itself – are being badly damaged by the actions of a small number of disordered politicians in positions of high power (Taylor 2021).

This paper has attempted to contribute to current debates about the negative consequences of inequality, by seeking to explain the resilience of the failed and damaging doctrines of neoliberal supply-sidism in terms of the powerful hegemony of economic and political interests allied to the financial services sector and with particular to the role of the UK in facilitating and maintaining that hegemony. The choice of the term “permissive neoliberalism” signifies both the formal embedding of supply-side policies relating to the property rights over financial assets as the legal encoding of, above all, the short-term predatory hunt for “yield”, and the political practice of (permissive) toleration of criminal and criminogenic activity. The privatisation of natural monopolies and the benign neglect of increasing capital concentration marks a decisive shift towards the commodification/assetisation of everything with an exchange value, regardless of whether there was either a socially beneficial use-value or indeed a negative value (predation). The description of some of the most egregious examples of predatory financialisation seeks to underpin the sanctification by the neoliberal state of ruthless value extraction and the toleration of an increasingly chronic dependence on an economic infrastructure of that extraction: the City and its associated archipelago of secrecy jurisdictions. This is followed by a brief survey of the depth and extent of the abuse of elite privilege in facilitating money laundering, kleptocracy, tax evasion and other criminal activity.

The shorter second part of the paper charts the growth of an ideology/mindset of entitlement on the part of economic and political elites and the role of psychopathic narcissism in crafting a legitimating narrative of their hegemony and its associated disorder. Above all the chronic disorder in the allocation of humanity’s material and financial resources invites a strong conclusion that a criminogenic financialised capitalism is not simply “killing the host” qua sustainable economic order, but, above is threatening the very survival of humanity’s biosphere by blocking the deployment of financial and human capital at sufficient scale to rescue the world’s climate from catastrophe.

Babiak P., Neumann C., Hare R. (2010), Corporate Psychopathy: Talking the Walk, “Behavioural Sciences and the Law”, vol. 28, pp. 174–193, https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.925

Birch K., Muniesa F. (eds.) (2020), Assetization. Turning Things into Assets in Technoscientific Capitalism, MIT Press, Cambridge, https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/12075.001.0001

Blain B. (2022), The Crypto Bubble is Bursting – Open Your Eyes and Spot the Ugly Naked Truth, https://morningporridge.com/blog/blains-morning-porridge/the-crypto-bubble-is-bursting-open-your-eyes-and-spot-the-ugly-naked-truth/ (accessed: 8.12.2022).

Brittain-Catlin W. (2005), Offshore: The Dark Side of the Global Economy, Picador, New York.

Bullough O. (2019), Money Land: Why Thieves & Crooks Now Rule the World & How to Take it Back, Picador, London.

Bullough O. (2022), Butler to the World: The book the oligarchs don’t want you to read – how Britain become the servant of tycoons, tax dodgers, kleptocrats and criminals’, Picador, London.

Burgis T. (2020), Kleptopia: How Dirty Money is Conquering the World, William Collins, London.

Christensen J. (2011), The Looting Continues: Tax; and Corruption, “Critical Perspectives on International Business”, vol. 7(2), pp. 177–196, https://doi.org/10.1108/17422041111128249

Christophers B. (2018), The New Enclosure: The Appropriation of Public Land in Neoliberal Britain, Verso, London–New York.

Christophers B. (2020), Rentier Capitalism. Who Owns the Economy and Who Pays for It, Verso, London–New York.

Cunliffe J. (2021), Is ‘crypto’ a financial stability risk? – speech by Jon Cunliffe, https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/speech/2021/october/jon-cunliffe-swifts-sibos-2021 (accessed: 8.12.2022).

Dorling D. (2014), Inequality and the 1%, Verso Books, New York.

Durand C. (2017), Fictitious Capital. How Finance is Appropriating our Future, Verso, London.

Foroohar R. (2016), Makers and Takers. How Wall Street Destroyed Main Street, Crown, New York.

Foroohar R. (2022), Talk of doing good rings hollow at Davos, “Financial Times”, 30 May.

Foster D. (2018), Just look at housing to see the true cost of privatisation, “The Guardian”, 12 June.

Funnell W., Jupe R. (2009), In Government we Trust: Market Failure and the Delusions of Privatisation, Pluto Press, London.

Gabor D., Kohl S. (2022), My Home is an Asset Class. The Financialization of Housing in Europe, http://extranet.greens-efa-service.eu/public/media/file/1/7461 (accessed: 8.12.2022).

Hare R.D. (2002), The predators among us, Keynote address to the Canadian Police Association Annual General Meeting, St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador, 27 August.

Hebous S., Johannesen N. (2021), At your service! The role of tax havens in international trade with services, “European Economic Review”, vol. 135, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroecorev.2021.103737

Howson P. (2022), Cryptocurrency price collapse offers hope for slowing climate change – here’s how, “The Conversation”, 17 May.

Hudson M. (2015), Killing the Host: How Financial Parasites and Debt Bondage Destroy the Global Economy, ISLET, Dresden.

Huffschmid J. (2002), Politische Ökonomie der Finanzmärkte, VSA-Verlag, Hamburg.

Keen S. (2017), Can we avoid another financial crisis?, Polity, London.

Laville S. (2020), England’s privatised water firms paid £57bn in dividends since 1991, “The Guardian”, 1 July.

Mazzucato M. (2013), The Entrepreneurial State. Debunking Public vs Private Sector Myths, Anthem & Penguin, London.

Mazzucato M. (2018), The Value of Everything. Making and Taking in the Global Economy, Allen Lane, London.

McCauley R. (2021), Why bitcoin is worse than a Madoff-style Ponzi scheme, https://www.ft.com/content/83a14261-598d-4601-87fc-5dde528b33d0 (accessed: 8.12.2022).

McNamara S. (2016), The Law and Ethics of High Frequency Trading, “The Minnesota Journal of Law, Science & Technology”, https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mjlst; https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2565707 (accessed: 8.12.2022).

Mellor M. (2010), The Future of Money: From Financial Crises to Public Resource, Pluto Press, London.

Murphy L., Nagel T. (2002), The Myth of Ownership: Taxes and Justice, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Ogle V. (2017), Archipelago Capitalism: Tax Havens, Offshore Money, and the State, 1950–1970s, “The American Historical Review”, vol. 122(5), pp. 1431–1458, https://doi.org/10.1093/ahr/122.5.1431

Parker D. (2004), The UK’s Privatisations experiment: the passage of time permits of the sober assessment, “CESifo Working Paper”, no. 1126, https://www.google.pl/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwin--eNvOz7AhW6QvEDHQkwDcMQFnoECAwQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.ifo.de%2FDocDL%2Fcesifo1_wp1126.pdf&usg=AOvVaw2CRGJVZp9S0sTwKXFT8jJP (accesed: 8.12.2022).

Pettifor A. (2017), The Production of Money. How to Break the Power of the Bankers, Verso, London.

Picardo E. (2022), 4 Big Risks of Algorithmic High-Frequency Trading, Investopedia, https://www.investopedia.com/articles/markets/012716/four-big-risks-algorithmic-highfrequency-trading.asp (accessed: 8.12.2022).

Pistor K. (2020), The Code of Capital, Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Raworth K. (2017), Doughnut Economics. Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st Century Economist, Random House, London.

Ryan-Collins J., Lloyd T., Macfarlane L. (2017), Rethinking the Economics of Land and Housing, Zed Books, London.

Sagar P., Christensen J., Shaxson N. (2013), British Government Attitudes to British Tax Havens in British Dependent Territories from 1967–1975, [in:] J. Leaman, A. Waris (eds.), Tax Justice and the Political Economy of Global Capitalism, 1945 to the Present, Berghahn Books, New York–Oxford.

Shaxson N. (2011), Treasure Islands. Tax Havens and the Men who Stole the World, Bodley Head, London.

Shaxson N. (2018), The Finance Curse. How Global Finance is Making Us All Poorer, Bodley Head, London.

Stafford P. (2020), FCA researchers outline $5bn “tax” imposed by high-speed trading, “Financial Times”, January 27.

Strange S. (1986), Casino Capitalism, Blackwell, Oxford.

Strange S. (1998), Mad Money, Manchester University Press, Manchester, https://doi.org/10.3998/mpub.10897

Taylor S. (2021), The problem of pathocracy, “The Psychologist”, vol. 34, pp. 40–45, https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.45.1.40

Tett G. (2010), Fool’s Gold: How Unrestrained Greed Corrupted a Dream, Shattered Global Markets and Unleashed a Catastrophe, Abacus, London.

Twenge J., Campbell K. (2009), The Narcissism Epidemic. Living in the Age of Entitlement, Simon & Schuster, New York.

Vercellone C. (2010), The Crisis of the Law of Value and the Becoming-Rent of Profit. Notes on the systemic crisis of cognitive capitalism, HAL, https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00516801 (accessed: 8.12.2022).

Weeks J. (2014), Economics of the 1%. How Mainstream Economics Serves the Rich, Obscures Reality and Distorts Policy, Anthem Press, London–New York–Delhi.

Wilkinson R., Pickett K. (2010), The Spirit Level. Why Equality is Better for Everyone, Penguin, London.

Wilkinson R., Pickett K. (2019), The Inner Level. How More Equal Societies Reduce Stress, Restore Sanity and Improve Everyone’s Well-being, Penguin, London.

Anatomia pasożytnictwa w stadium kapitalizmu sfinansjalizowanego: roszczeniowość i destrukcyjny charakter permisywnego neoliberalizmu

Abstrakt. Artykuł niniejszy jest przyczynkiem do debaty o negatywnych konsekwencjach współczesnych nierówności ekonomicznych oraz mechanizmach służących ich legitymizowaniu. Analizuje on, w jaki sposób zdyskredytowane i szkodliwe neoliberalne podejścia podażowe w ekonomii są nadal traktowane jako prawomocne doktryny ekonomiczne, przyczyniając się tym samym do podtrzymywania hegemonii sprawowanej przez sektor finansowy, zwłaszcza w Zjednoczonym Królestwie. Artykuł ten wprowadza pojęcie „permisywnego neoliberalizmu”, przez które rozumie zarówno legalne praktyki wykorzystywania aktywów finansowych w celu realizacji krótkoterminowych zysków, jak i polityczną ochronę rozpiętą nad kryminalną i kryminogenną działalnością na rynkach finansowych. Opisuje najbardziej bulwersujące przypadki drapieżczej finansjalizacji jako przykłady usankcjonowania przez neoliberalne państwo bezwzględnego procesu ekonomicznego wyzysku i tolerowania w coraz większej mierze systemowego uzależnienia ekonomii politycznej Zjednoczonego Królestwa od londyńskiego City z towarzyszącym mu archipelagiem tajnych zamorskich jurysdykcji.

W drugiej, krótszej części niniejszego artykułu zaprezentowano proces formowania się postawy roszczeniowej wśród reprezentantów gospodarczych i politycznych elit oraz roli, jaką psychopatyczny narcyzm odgrywa w procesie uprawomocnienia ich hegemonicznej pozycji społecznej. Systemowa niezdolność do takiego inwestowania zasobów materialnych i finansowych ludzkości, które uchroniłoby ją od skutków nadciągających zmian klimatycznych, skłaniają do sformułowania wniosku, że kapitalizm w swoim obecnym stadium jest nie tylko pasożytem uniemożliwiającym osiągnięcie zrównoważonego wzrostu gospodarczego, ale że wręcz stanowi on zagrożenie dla samych ekologicznych warunków przetrwania ludzkości jako gatunku.

Słowa kluczowe: finansowy kapitalizm, neoliberalizm, błędna alokacja kapitału, negatywne skutki dla środowiska, tendencja ekocydalna