https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2302-5553

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2302-5553

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0844-2869

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0844-2869

Keywords: sport shooters, access to guns, social capital, sport organizations, organizational engagement, sport for development

In the scientific and public discourses on the current state of civil society in Poland it is believed that the number of Poles belonging to nongovernmental organizations is insufficient and that the level of local activity is low.[1] Researchers associate this state of affairs with an insufficient level of social trust (Asadullah 2017), which is a capital necessary not only for the creation of broader, i.e., nonfamily, social networks (social bridge networks) (Pratten 2017; Growiec 2009: 56, 64; Hlebec et al. 2010) but also for economic growth (Francois, Zabojnik 2005; Będzik 2010: 20).[2] Some authors interpret this deficit, a low level of generalized confidence (Hanamura et al. 2017; Klein, Marx 2018), in terms of Poland’s incompatibility with the West (Nowakowski 2008: 216, 217). Other authors combine the low level of social capital with the lack of integration efforts. During the transformation, there was blurring of norms, and this led to a generalized lack of trust (Ziółkowski 2005: 200; Kornai et al. 2004). According to some analysts, the low level of social capital (including trust) does not bode well for Poland’s economic development as achieved by Western countries. This conclusion appears, among others, in the cyclical “Social Diagnosis” (Czapiński, Panek 2015: 340; Czapiński 2006). Not everyone, however, agrees with this narrative; they point to an overly “looking at the West” as a form of (inferiority) complex (Giza-Poleszczuk 2018). Western European countries do not have to be a reference point in all aspects of the evaluation of Polish transformation, which in fact was largely an imitative transformation.[3] The low level of membership in organizations of people in the post-working age can be explained, for example, by the lack of time due to involvement in family life, which is usually richer than that in the post-protestant countries – especially in the care of grandchildren.

In the context of this discussion, one should note that membership of an organization itself, as a form of social commitment, is an important social resource. It is a space to form so-called weak bonds, which some scholars consider more important for economic development than their strong counterparts (Granovetter 1973). The low membership rate (only 13.4% of Poles had membership in 2015; Czapiński, Panek 2015: 341) raises the importance of participation in sport organizations, which are most popular in Poland, after religious ones. Membership in sport organizations is thus related to the issue of Polish society development.

Considering the number of people practicing in sports clubs in Poland, sport shooting is ranked high at the fifth place among sport disciplines. Football, volleyball, swimming, and karate occupy higher positions than sport shooting in this ranking. A smaller number of people practice, e.g., in clubs related to athletics or basketball (GUS 2019: 240). Sport shooting, however, is not a popular sport in Poland. It does not have huge supporters following the struggles of professional representatives of this discipline. It is not a sport that Polish society live and breathe everyday (like football, ski jumping, or athletics). It should also be remembered that the number of people practicing in clubs is not the same as the number of amateurs practicing a given discipline. Other physical activities such as running or cycling boast a much higher number of amateurs (some of them became recently extremely fashionable – see ‘running boom’: Stempień et al. 2022). However, they are not usually associated with sports clubs. Shooting is therefore distinguished by the large number of people practicing in clubs, which is largely because of the procedures for maintaining a license for weapons. The fact that many amateurs are associated with sports clubs (regardless of their motives for such membership) emphasizes the social role of this discipline.

In his article David Yamane claims the lack of ‘sociology of gun culture’ in the United States (2017). He proves that the research on guns are dominated by criminological and epidemiological studies of gun violence. There is also the sociology of leisure approach present (sport shooting, collecting guns) (Murray et al. 2016). But gun culture 2.0 as Yamane calls it refers to armed self-defence, the culture of armed citizenship. Both recreational and self-defence gun owners are members of vast social world and many networks, organizations and social relations (Yamane 2017: 7).

Although sport shooting has a relatively large number of practitioners in Poland (and it seems its popularity is growing (Zwarycz 2020)), it has been rarely subjected to sociological analysis too. From the “civic” perspective presented above, this activity should be viewed positively as an expression of filling a “sociological vacuum” (cf. Pawlak 2015) and as a hope for building (or an indicator of occurrence) of social capital. On the other hand, however, sport shooting is associated with the issue of access to firearms, and thus indirectly with the relationship between their availability and the number of crimes and suicides committed using them (Wiebe 2003: 771), theft of weapons (access to illegal weapons) (Azrael et al. 2017: 51), improper storage of weapons (Betz et al. 2016: 543), and the problem of implementing adequate legal regulations (Hahn et al. 2005: 40–41). Access to firearms, especially during periods of media coverage of armed crime, raises numerous concerns and controversies. These concerns include the belief that possession of a weapon is always a threat. Hence, it is only a step toward an axiological dispute, i.e., to seek an answer to the question of the legitimacy of restricting (denying) the right to possess a weapon (including for personal defense purposes) on the grounds that it may be (potentially) misused (Cook, Ludwig 1997: 1). This dispute, on a cultural level, is related to the issue of alternative orientations of individuals. The right to own a weapon is compatible with the “Western” individualistic orientation. The alternative orientation toward collectivist values is associated with a tendency to limit and question this right (Celinska 2007: 232–233).

The ongoing debate, based mainly on the realities of American society (i.e., society with very high rates of access to weapons), only partially matches the realities of sport shooting in Poland (a country with relatively low weapon saturation). Poland belongs to the group of a few countries with the lowest number of weapons per hundred people in Europe (less than 5). Other so poorly armed countries include Romania, the Netherlands, and Lithuania. In France, Germany, or Norway, the ratio is approximately 30 weapons per 100 citizens. In Finland and Switzerland, the rate is even higher, at around 45 weapons per 100 people.[4] In the United States, the number of weapons is close to or exceeds the number of citizens (Karp 2018: 4), which is the subject of deeper analysis that combines such a liberal right to own weapons with other aspects of social life, e.g., the map of pollution and discrimination against certain categories of citizens (cf. sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild writing about the free arms trade and the right to stand your ground in the state of Louisiana as part of a whole series of laws which, in her opinion, favor white men over women and African Americans (2017: 118–120)). It is also important here to know that practicing sport shooting is only one of the many reasons to obtain a gun permit[5] (see Table 1). Combining sport shooting with the wider problem of citizens’ access to weapons is therefore only partially justified here and should be done with due proportions.

Table 1. Number of persons who were issued a weapon license (as on December 31, 2018)

| Purpose for which the arms license was issued | Number of persons who were issued an arms license for a given purpose | Number of weapons registered by arms license holders |

|---|---|---|

| Hunting | 127 768 | 322 451 |

| Personal protection | 36 499 | 40 641 |

| Sport | 30 792 | 76 761 |

| Collecting | 18 064 | 59 318 |

| Commemorative | 1 668 | 2 444 |

| Training | 575 | 3 418 |

| Historical Reconstructions | 64 | 240 |

| Protection of persons or property | 9 | 10 |

| Other | 163 | 146 |

| Total | 215 602 | 505 429 |

Source: http://statystyka.policja.pl/st/wybrane-statystyki/bron/bron-pozwolenia/170176,Bron-pozwolenia-2018.html (accessed: 22.01.2020).

Sport shooting in Poland is organized within the framework of the Polish Sport Shooting Association established in 1933. Provincial unions (16 within the whole country) have associated clubs and their members. For example, in the West Pomeranian Association of Sport Shooting, there are 28 clubs and 1864 sport shooters.[6] It is estimated that 45 thousand sport shooters are formally associated in the sport shooting clubs all over the country (GUS 2019: 240), of which the number of people actively practicing this sport may amount to 23 thousand. These are mainly players of the so-called common group. This group comprises amateurs who practice this sport for recreational purpose. They usually have neither aspirations nor skills to enter the national team.

It should be noted that this form of sporting activity has been gaining popularity in recent years. This is evidenced by the fact that the number of gun licenses granted for sport purposes is gradually and clearly growing (cf. Table 2). The analysis of these data should also consider the fact that the number of licenses issued is only a partial indicator of interest in this sport, as some shooters use club weapons or borrow them from friends or family members, while other players use their own weapons. An increase in the number of the shooters themselves (counted in absolute numbers) will therefore each time be greater than the number of licenses issued.

Table 2. Number of gun licenses issued for sporting purposes in 2014–2018

| Year of issue of licenses | Number of licenses issued | Increase as compared to the previous year |

|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 1488 | base |

| 2015 | 2824 | 90% |

| 2016 | 3605 | 28% |

| 2017 | 4910 | 36% |

| 2018 | 5172 | 5% |

Source: http://statystyka.policja.pl/st/wybrane-statystyki/bron/bron-pozwolenia (accessed: 15.01.2020).

The proper classification of weapons (types of weapons possessed) is also significant for the proper characterization of Polish sport shooting. Martin J. Dougherty (2015: 7) emphasizes that “sporting weapons” may mean all kinds of weapons that are not designed to fight people and that the category of sport shooting includes target shooting (recreational and sports), hunting, and even pest control. In Poland, however, such a definition would be considered too broad. Sportsmen and hunters are recruited by separate organizations. They are also subject to other procedures concerning the acquisition and maintenance of the right to possess a weapon and to be allowed to shoot. Shooters participating in sports competitions may use weapons that are typically used for sporting purpose and also those weapons used in uniformed services. An important point here is only the conformity of its type that is specified in the competition announcement (e.g., central ignition weapons).

The context of access to weapons (the possibility of possessing weapons) and social reception of weapon possession is not without significance for Polish sport shooters. The article presents three analytically separated aspects of practicing this sport, which have been developed on the basis of results of research conducted among active sport shooters from the entire country. This analysis is therefore aimed at identifying (reconstructing) the image of sport shooting from its “internal” perspective, i.e., competition. The aim of this article is to answer the following research questions:

All the aforementioned issues are developed on the basis of the results of empirical research on active sport shooters in Poland.

The present research was conducted from January 16 to May 15, 2019. The research population (the category into which the results of the research can be generalized) were people actively involved in sport shooting in Poland. The research sample included 253 shooters associated with sport shooting clubs throughout the country. The authors of the research made every effort to ensure that information about the research (as well as the possibility of participating in the research) was available throughout Poland. The survey was conducted using the computer-assisted web interviewing (CAWI) technique; the internet addresses for the survey were made available to the members of sport shooting clubs via websites: The West Pomeranian Association of Sport Shooting and some clubs associated with the PSSA, such as https://strzelec.edu.pl. A link to the survey page was sent to clubs associated in all other regional sport shooting associations. The research sample included 236 men (93.3% of the respondents) and 17 women (6.7% of the respondents). The sample size was approximately 0.56% of sport shooters from the registered clubs and approximately 1% of active sport shooters from the entire country.

Sample structure: The research sample was dominated by people with higher education (70% of respondents) and in the age categories 41–50 (36% of respondents) and 31–40 (30% of respondents). The majority of the respondents came from medium-sized and larger cities (cities over 50 thousand inhabitants; 54% of respondents), were married (70% of respondents), and had two (35% of respondents) or one (31% of respondents) child. Generalizing these results based on population revealed that a typical active sport shooter in Poland is a well-educated man at the age of 31–50 years, lives in a city with more than 50 thousand inhabitants, is married, and has one or two children.

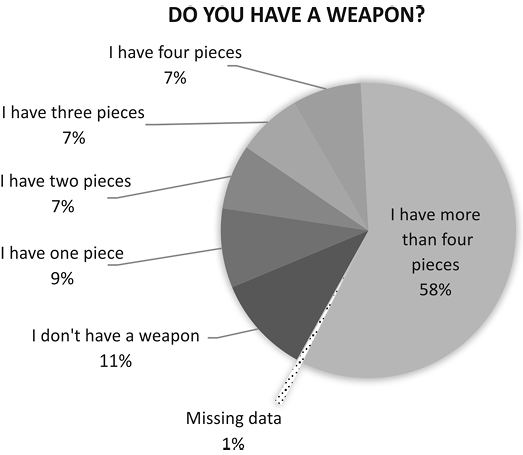

Practicing a given sport does not always have to be part of the basic goal of sports training, which is self-improvement (and subsequently competition) of players. For sport shooting, an important factor of interest in this discipline is the access to firearms itself. This access is possible because of acquiring and maintaining (through active participation in competitions) the status of “sport shooter” (which is confirmed annually by a competitive license issued by PSSA). As shown in Figure 1, sport shooters make relatively “wide” use of these opportunities. Most of them (58% of respondents) have more than four weapons. For 11% of respondents, involvement in the discussed sporting activity does not mean the possession of weapons. This is a specific characteristic of the discussed discipline. Being a sportsperson translates into the right to purchase items (weapons) that are not available to the vast majority of society. The possibility of possessing a weapon should be considered an important motivator both to associate with organizations (sport shooting clubs) and to actively participate in competitions, which constitute a pass for further possession of a weapon.

Figure 1. Number of weapons available to sport shooters

Source: own research.

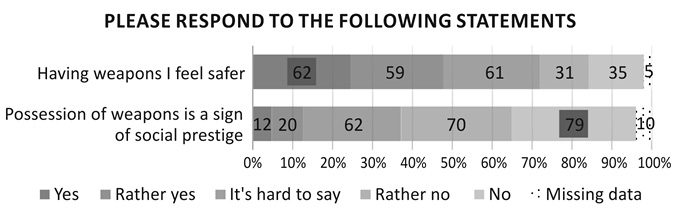

The possibility of possessing a weapon poses a question about its importance and functions that goes beyond the sports competition itself. Two motives in particular are of interest here: the improvement of a perceptible level of safety (possibility of using weapons for personal defense purposes) and, in a broader social context, the acquisition of greater social prestige because of possessing rare goods (here weapons) (cf. Figure 2).

Figure 2. The importance of access to weapons in the opinion of sport shooters

Source: own research.

Almost half of the respondents (48%) agree with the statement that access to firearms increases their safety level. This factor should therefore be considered important in the context of the analysis of motivation to practice sport shooting. Practicing other disciplines such as combat sports also has the indicated potential (building a sense of security) (Lickiewicz 2006: 143). For sport shooting, this feeling is shaped not so much by the skill itself as by the access to means of defense.

The second motive is no longer relevant here. Prestige (besides earnings) is considered to be one of the basic “general awards”. Social prestige is an important resource that positions people in the social hierarchy. However, according to the respondents, a weapon is not a factor that builds the personal prestige of its holder. Only 13% of respondents hold a contrary view. Having a weapon “for show” cannot therefore be treated as an important motive to engage in sport shooting. This can be partly explained by the rules of weapon storage. This is because weapons are usually hidden from the view of others, which reduces their potential to raise the prestige of persons possessing them. The fact that a weapon is associated with danger and crime is also important.

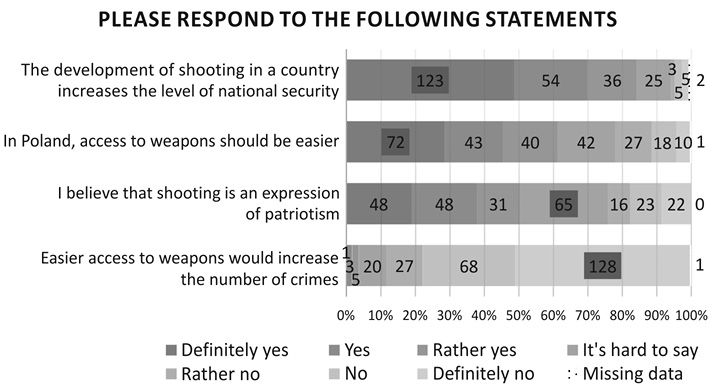

However, according to shooters, it is not reasonable to combine access to weapons with the threat of using them for criminal purposes; this is usually due to a lack of knowledge and negative stereotypes. The vast majority of respondents believe that easier access to weapons would not reflect an increase in the number of crimes (cf. Figure 3). This conviction is consistent with the conviction that access to weapons in Poland (currently very limited) should be easier. The advantage of such changes would be (according to the respondents) an increase in the level of national security. Liberalization of the law related to access to weapons would, in their opinion, contribute not so much to an increase in the threat as to an increase in the level of both national and personal security (in terms of greater sense of security mentioned earlier). Interestingly, the research shows that active participation in the sport in question does not have to be an “expression of patriotism”. These answers show different ways of defining shooting by the shooters themselves, who may or may not define shooting in terms of sport. The large number of hesitant respondents (65 people chose “hard to say” option) in the scope discussed may be a manifestation of the belief that sport shooting is primarily one of the sport disciplines whose function is to compete and improve, not to spread patriotism. This belief may be based on a clear political polarization of Polish society where its various parts perceive history and “national heroes” in a different way and values the tradition differently. Different definitions of patriotism (related to different political options) could be a source of conflicts in the shooting community. Focusing on purely sporting functions reduces one of the fields of disintegration; organization system reduces the complexity of its environment, which (from the perspective of its integrity) should be seen in functional terms (Luhmann 1970: 115–117).

Figure 3. Access to firearms and out-of-sport shooting functions

Source: own research.

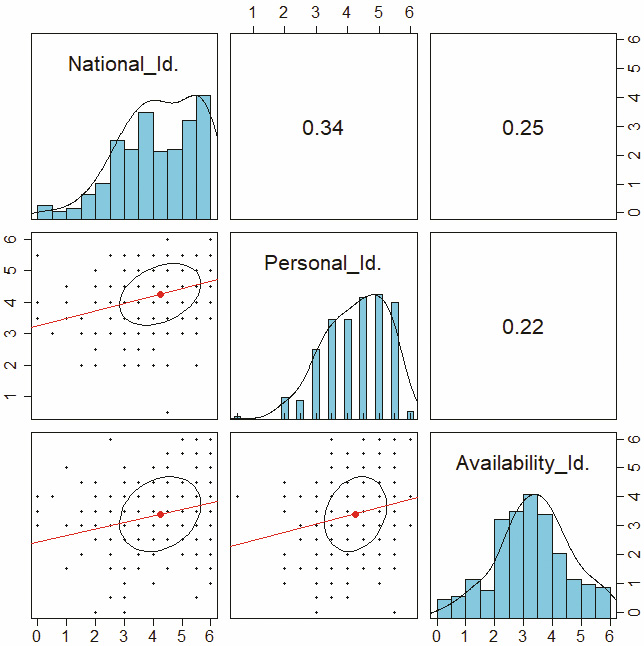

Using the above specific questions, we created three indexes indicating the degree of belief that:

The indices were standardized in the range of 0–6, where 6 indicates the highest degree of acceptance of the above statements.

Below is the correlation matrix (Figure 4), along with a frequency analysis for the indicated indices.

Figure 4. National and personal security vs. availability of firearms – correlation matrix

Source: own research.

According to Figure 4, there are weak positive correlations between the indexes (Pearson r coefficients are given in the graph). It is worth noting the asymmetry of the distributions of the first two indexes (National_Id. and Personal_Id.). This means that the majority of respondents agree with the statement that the development of shooting enhances the level of national security and that owning weapons increases the sense of personal security. The distribution of the index “Availability_Id.” in contrast, is much more symmetrical.

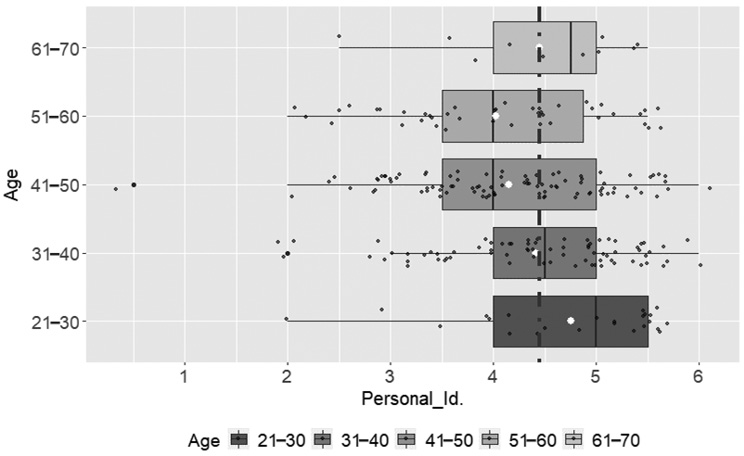

In Figure 5, we show the “Personal_Id.”, that is, the level of belief that access to weapons increases security with age of respondents distribution.

Figure 5. Characteristics of “Personal_Id.” by different age categories*

* White points on the graph indicate the arithmetic mean.

Source: own research.

In Figure 5, the two extreme age categories for this survey (21–30 and 61–70) stand out, whose representatives are more likely to believe that access to guns increases personal safety.

Membership of an organization poses a question about the mechanism of recruitment of its participants. For sport shooting as far as spending free time is concerned, the main role is played by the circles of friends. Future members of shooting clubs join them mainly because of the network of their social contacts (mainly due to friends and also due to family or teachers) (cf. Table 3). Intentional activities of the club itself (advertising on the internet or in the press) are less important here. It may be expected that such a (internal) recruitment mechanism (including people whose friends or families are already members of the clubs) will affect the homogamy (unification) of the shooting community.

Table 3. Sources of knowledge on shooting possibilities*

| How did you learn about the possibility of sport shooting? | ||

|---|---|---|

| Class | Number | Percentage |

| Friends | 157 | 52 |

| Internet | 63 | 21 |

| Family | 28 | 9 |

| Teacher | 16 | 5 |

| Press | 10 | 3 |

| Other | 24 | 8 |

| No data | 5 | 2 |

| Total | 303 | 100 |

* More than one source was identified.

Source: own research.

The question on the degree of openness of the shooting clubs (whether they should be open to all willing) clearly differentiates the respondents. A significant proportion of respondents (47%) believe that sport shooting should be reserved for appropriately selected people. In line with previous findings, this position is rather not related to the fear of losing prestige (let us recall that access to weapons is not considered a marker of prestige). The concern about the selection of the right people rather stems from the fear of its misuse: about creating a threat not only to the wider society but also to the shooters themselves (image loss or the risk of an accident at the shooting range). This issue is presented in more detail later in the article.

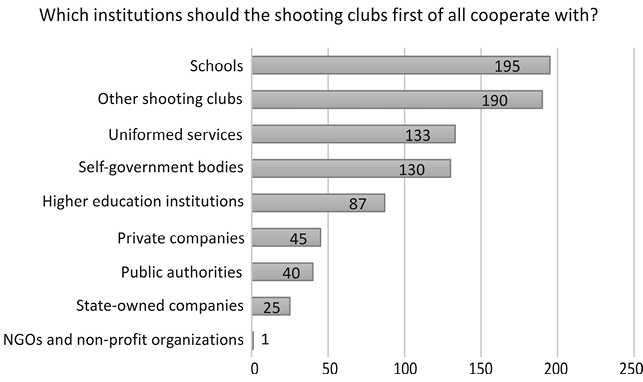

Sport shooting can perform various functions. Apart from its primary sporting function, this form of activity can also be associated with educational or patriotic activities. According to the respondents, sport shooting clubs should primarily cooperate with schools and other shooting clubs, which emphasizes the educational and sporting character of shooting (cf. Figure 6). Other functions of shooting (patriotic, commercial) are less important in the light of the presented data. It is significant that only one person indicated NGOs (clubs were excluded). The obtained distribution of responses is because of the low rate of Poles belonging to such centers. This phenomenon can be (at least partly) explained by a short history of their activity in post-socialist countries.

Figure 6. Desired institutional links*

* Multiple answers possible.

Source: own research.

The image of a given discipline, and thus of the sportspersons themselves, is determined by several factors. These include the degree of given sport mass range, costs related to its practice, or compliance with the principles of a healthy lifestyle, which are significant in this context. For example, running, one of the most frequent (although associated with membership in sports clubs to a small extent) forms of physical activity of Poles, fits into the model of a healthy lifestyle. This fact creates a positive image of runners in society. However, the mass range of this sport also has its negative (image) consequences. Large-scale mass events (amateur running competitions) lead to a temporary stoppage of traffic, which in turn translates into dissatisfaction of drivers of large cities.

Although sport shooting associates with a relatively large group of people (in sports clubs), the discipline itself is not popular in Polish society. It does not enjoy greater interest of supporters (people who do not practice it). The number of practicing (amateur) people is also not very high as compared to that of other disciplines (mass sports), where a significant number of practicing people do not belong to any club. This partly explains the distribution of answers to the question about the image of a sport shooter. The dominance of the answers that prove a relatively neutral image (68% of responses) coincides with the lack of knowledge on this discipline (lack of interest in this discipline) in the society.

Despite the fact that the image of sport shooting (according to shooters) in Poland today is rather neutral, most of them believe that it is necessary to work on the image of the sport (87%). This image due to several factors (Table 4a, 4b) may deteriorate in the future. A particularly important point here is the issue of access to firearms and the risks associated with them. Shooters are most concerned about the unjustified (automatic) combination of weapons and threats. Hence, they need to work (mainly education) and defend themselves against any unjustified attacks on the shooting environment. A detailed list of threats identified by the shooters is presented in Tables 4a and 4b.

According to sport shooters, the main factor detrimental to their image in Polish society is the insufficient level of knowledge of the average citizen about this activity. On several occasions, the image of a sport shooter is covered with clichés related to hunters’ circles or even with the criminal world. An element common to these circles is the fact of possessing weapons. However, the manner in which a weapon is used and its purpose are completely different in each of these environments.

Moreover, the shooters believe that EU policies are geared toward restricting access to weapons on the pretext of increasing security. They believe that the national police adopts a similar course of action. These actions place weapons owners, including those who have acquired them legally, in a negative light.

According to the respondents, supporters of left-wing, or communist ideology (roots dating back to the time of the People’s Republic of Poland) also have a negative impact on the image of the shooters. The henchmen of such “hostile” ideology are mainly journalists who intentionally or due to a lack of their own knowledge misinform public opinion.

Despite noticing many external threats, the shooters are also self-critical, and they also point out “internal” defects – problems of their own social environment. They think that they do not promote themselves enough and to an appreciable extent. They also notice cases of inappropriate behavior with a weapon in their own environment: individual “promotion” (carrying a weapon for show) and insufficient care for safety and level of shooting training.

In addition to the problems highlighted in Tables 4a and 4b, the respondents also indicated the political and historical context unfavorable to their environment. Some respondents suggested that shooting is linked (or is linked by the shooters themselves) with ideas represented by the extreme right-wing, i.e., with patriotism perceived in terms of defense. Others, in turn, reminded that the propaganda still practiced by the communist authorities (historical conditions) was to blame, thereby convincing people that only servants and criminals had weapons. These actions consolidated the conviction that the average Polish citizen “is not mature enough” to possess a weapon.

Table 4a. Factors and conditions detrimental to the image of a sport shooter in Poland

| Categories | fi | Declared problems | Sample statements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lack of knowledge – stereotypes in society | 66 | Stereotypes |

|

| Lack of knowledge |

|

||

| Unjustified linking of access to weapons to crime | 19 | Perception of the weapon itself as a source of danger |

|

| Identifying the owner of the weapon with a criminal offence |

|

||

| Firearms offences and making them news |

|

||

| Hostile ideology – propaganda | 11 | Left-wing, communist propaganda |

|

Source: own research.

Table 4b. Factors and conditions detrimental to the image of a sport shooter in Poland

| Categories | fi | Declared problems | Sample statements |

|---|---|---|---|

| The media and journalists – inappropriate information in the media | 59 | Deliberate disinformation by journalists |

|

| Lack of knowledge among journalists |

|

||

| Searching for sensation |

|

||

| Shooting environment – inappropriate behavior and lack of organization | 40 | Inappropriate shooting organization |

|

| Inappropriate behavior of shooters |

|

||

| Insufficient training of shooters |

|

||

| Hunters – the association with hunting or the hunters themselves | 30 | Confusing sport shooting with hunting |

|

| Hunting as such (hunters) |

|

||

| The false image of hunting |

|

||

| Politicians | 21 | Negative attitude of national and EU politicians |

|

| Police | 6 | Negative attitude of the police towards wider access to weapons |

|

Source: own research.

Despite a relatively strict law regulating access to weapons in Poland, social activity aimed at easing the requirements for potential weapon holders and popularizing shooting skills does not take a clear (crystallized) form in Poland. Organizations such as ROMB, Pobudka, or Braterstwo (https://romb.org.pl/o-nas/, https://www.pobudka.org, https://braterstwo.eu, respectively) indicate that liberalization of access to weapons in Poland would increase the security of citizens, stimulate the upbringing of children and young people in the spirit of patriotism, improve knowledge of the history of the country and its weapons, and contribute to the development of a responsible civil society.

However, there seems to be a common perception among the major parties that there is no need to change the existing rules on the possession and use of weapons. Contrary to appearances, even the ruling right-wing PiS party intended to introduce restrictions on, e.g., black powder weapons, which can now be purchased without permission. However, after protests of representatives of interested circles, among others sport shooters (https://braterstwo.eu/tforum/t/71167/#amv, accessed: 5.02.2020) – a model protest letter addressed to MPs), who participate in such competitions, the most far-reaching changes were finally withdrawn. Other changes were to include the need to label each part of the weapon. This labeling was missing in particular in replicas of historical weapons held under the so-called arms collection permit. Such weapons may also be used during sports competitions (if such a competition is organized). Concerns about the introduction of a stricter law are manifested in the statements of the respondents themselves, who considered politicians to be an unfavorable factor for the development of sport shooting (cf. Table 4b).

The double morphogenesis of social movements (Sztompka 1987; 2005: 265) assumes two sides of this process. The internal dynamics of social movement includes its creation, mobilization, expansion of structures, and the end of activity. It is difficult to evaluate whether organizations related to the promotion of a positive image of law-abiding citizens having weapons and to the fight against false stereotypes associated with the pursuit of legal possession of weapons form a social movement (in a strictly sociological sense).

The Polish Sport Shooting Association has existed for a relatively long time – since 1933. However, several organizations referring to the possession of weapons in a broader sense, invoking human and civil rights, operate for much shorter periods. It should be remembered that during the period of the People’s Republic of Poland, the activity of nongovernmental organizations was significantly limited; they could operate only under strict control of the ruling party. The influence of Polish history on the perception of shooting was also noted by the respondents themselves.

At present, it is difficult to unequivocally identify the factors that initiate the creation of a movement for the right to own weapons (a proper system of structural tensions or a single charismatic leader who would direct the mobilization phase). Although the number of permits issued for weapons has been growing in recent years, it is also difficult to prove some spectacular expansion of structures. It seems that the ideas represented by organizations related to sport shooting partly overlap with those of some wider community, whose aim is to promote the liberalization of the right to own weapons, or at least not to tighten the criteria for issuing the weapons permits. However, some of the sportsmen participating in the present research link the organizations associated with these efforts with political and not just civic activity. These associations, i.e., combining sport with the issues of history, patriotism, and defense (values inscribed in the organizations’ missions related to the promotion of access to weapons), arouse reluctance in some respondents. Presently, there is some confusion related to the different definitions of sport shooting, in terms of its purely sporting and nonsporting interpretation.

It is also ambiguous to analyze the external dynamics of social movements, i.e., how (and whether) a given movement affects society. The movement that popularizes the right to possess weapons has some effects on the political sphere in Poland (here, we should note the pressure that resulted in the removal of the most sensitive provisions in the amendment of the Weapons and Ammunition Act). It also has some impact on the economy (impact on the image of armaments industry plants). However, activities aimed at popularizing sport shooting encounter significant barriers. A good example of this is the Ministry of National Defense project from 2016: “A shooting range in every poviat”. This project (assessed from today’s perspective) has failed. Enough to say that to date, there is only one such facility created, despite there being 380 poviats in Poland.[7]

Although organizations that spread access to weapons refer to the idea of social movement on their websites, it is impossible to call them a mature social movement at present. It seems more appropriate to define them as a collective actor of civil society. In the current political situation, this actor is unlikely to have any influence on structural changes. Perhaps, however, these organizations will cause some conscious changes. These efforts have already yielded some success by introducing the subject of access to arms into public discourse, which did not occur during the communist era. However, this “success” will not quickly translate to concrete benefits for the shooting community. The social climate is currently unfavorable to the spread of such ideas and such activities; thus, almost all actors on the political scene are reluctant to take up this subject. Thus, if the “movement” popularizing the right to own weapons somehow influences the political scene in Poland, it will manifest itself mainly in stopping unfavorable changes.

The practice of sport shooting by a common group (amateur sport) may be associated with organizational involvement, community capacity building, and the concept of sport for development (SFD). The social world of shooters includes other collective actors and creation of social cooperation networks. For example, the process of establishing a shooting range in Poland involves the management of the club that will be responsible for it; the authority approving the shooting range’s regulations; and representatives of organizations that own the ground, e.g., the authorities of the State Forests (if the shooting range is in an open field, i.e., outside the building) or schools or non-governmental organizations. During the ceremonial opening of the shooting range, representatives of the stakeholders are also often present; furthermore, sometimes a priest is also invited, who blesses this place and prays for the safety of the shooters.

In cultures that promote individualism, development is often understood in terms of raising an individual’s potential. In a broader sense, however, it may also mean the development of community, community capacity, preventing social exclusion, and building social capital (Jaitman, Scartascini 2017) or even peaceful global coexistence. The framework of such development, i.e., community development, includes providing encouragement to clubs and sport associations to develop SFD programs (Breuer 2014). Shooting clubs in Poland conduct such activities. Some of them organize international competitions (e.g., Grajcar club from Police has organized competitions to which shooters from border German cities were invited many times in the last decade). Many clubs are open to membership for people with disabilities, and some of these organizations are even dedicated to such people. Women and young people under adult supervision are always welcome. During many local competitions, all those people who are willing can participate in individual competitions, including those without a proper shooting license. The activity of these clubs can therefore be associated with the implementation of the postulates of inclusion (social inclusion as opposed to various kinds of exclusion) and diversity management. This is where the social power of sport organizations is manifested, with their activating, inclusive, and bonding potential for local impact. For sport shooting clubs, this potential has its partial origin in the need to have weapons that can be satisfied by belonging to an organization.

In 2001, the United Nations (UN) appointed its first Special Adviser to the Secretary-General on Sport for Development and Peace.[8] At the same time, Robert Chaskin published an article in which he presented a definition of “community capacity” as the interaction of human capital, organizational resources, and social capital existing within a given community that can be leveraged to solve collective problems to improve or maintain the wellbeing of a given community. This may operate through informal social processes and/or organized effort (Chaskin 2001).[9] The potential of the community built up by, among other things, sport interactions can improve the health of both individuals and entire communities (Lee, Jung 2018). Organizational commitment, which is usually associated with the business world, is crucial here. However, this logic should be extended to include membership in nongovernmental organizations (Malinen, Harju 2016), including sports clubs and other associations.

Asadullah M.N. (2017), Who Trusts Others? Community and Individual Determinants of Social Capital in a Low-Income Country, “Cambridge Journal of Economics”, vol. 41(2), pp. 515–544.

Azrael D., Hepburn L., Hemenway D., Miller M. (2017), The Stock and Flow of U.S. Firearms: Results from the 2015 National Firearms Survey, “The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences”, vol. 3, no. 5, pp. 38–57.

Betz M.E., Azrael D., Barber C., Miller M. (2016), Public opinion regarding whether speaking with patients about firearms is appropriate: Results of a national survey, “Annals of Internal Medicine”, vol. 165(8), pp. 543–550.

Będzik B. (2010), Deficyt kapitału społecznego zwiastunem nadchodzących kłopotów, “Acta Scientiarum Polonorum Oeconomia”, vol. 9(1), pp. 15–22.

Breuer C. (2014), Sport for development – the role of sports clubs, Conference: The 2nd International Symposium on International Development and Peace through Sport, [in:] TokyoVolume: National Institute of Fitness and Health & University of Tsukuba (ed.), The 2nd International Symposium on International Development and Peace through Sport, National Institute of Fitness and Health, University of Tsukuba, Tokyo, pp. 53–65, https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.4524.9607

Celinska K. (2007), Individualism and collectivism in America: The case of gun ownership and attitudes toward gun control, “Sociological Perspectives”, vol. 50(2), pp. 229–247.

Chaskin R.J. (2001), Building Community Capacity: A Definitional Framework and Case Studies from a Comprehensive Community Initiative, “Urban Affairs Review”, vol. 36(3), https://doi.org/10.1177/10780870122184876

Cook P.J., Ludwig J. (1997), Guns in America: National Survey on Private Ownership and Use of Firearms, US Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice, Government Printing Office, Washington.

Czapiński J. (2006), Polska – państwo bez społeczeństwa, “Nauka”, no. 1, 2006, pp. 7–26.

Czapiński J., Panek T. (eds.) (2015), Diagnoza społeczna 2015. Warunki i jakość życia Polaków, Rada Monitoringu Społecznego, Warszawa.

Dougherty M.J. (2015), Broń sportowa. Rodzaje uzbrojenia. Techniki użycia, transl. T. Prochenka, M. Wasilewski, Bellona, Warszawa.

Francois P., Zabojnik J. (2005), Trust, Social Capital, and Economic Development, “Journal of the European Economic Association”, vol. 3(1), pp. 51–94.

Giza-Poleszczuk A. (2018), Jako socjologowie straciliśmy zdolność prawdziwej analizy (interviewed by Krzysztof Mazur), https://klubjagiellonski.pl/2018/05/20/giza-poleszczuk-jako-socjologowie-stracilismy-zdolnosc-prawdziwej-analizy-rozmowa/

Granovetter M. (1973), The Strength of Weak Ties, “American Journal of Psychology”, vol. 78(6), pp. 1360–1380.

Growiec K. (2009), Związek między sieciami społecznymi a zaufaniem społecznym – mechanizm wzajemnego wzmacniania?, “Psychologia Społeczna”, vol. 4, no. 1–2(10), pp. 55–66.

GUS (2015), Wartości i zaufanie społeczne w Polsce w 2015 r., Wydział Analiz Przekrojowych, Departament Badań Społecznych i Warunków Życia Głównego Urzędu Statystycznego, Ośrodek Statystyki Matematycznej Urzędu Statystycznego, Warszawa–Łódź.

GUS (2019), Mały Rocznik Statystyczny Polski, Główny Urząd Statystyczny, Warszawa.

Hahn R.A., Bilukha O., Crosby A., Fullilove M.T., Liberman A., Moscicki E., Snyder S., Tuma F., Briss P.A. (2005), Firearms laws and the reduction of violence: A systematic review, “American Journal of Preventive Medicine”, vol. 28, pp. 40–71, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2004.10.005

Hanamura T., Li L.M.W., Chan D. (2017), The Association Between Generalized Trust and Physical and Psychological Health Across Societies, “Social Indicators Research: An International and Interdisciplinary Journal for Quality-of-Life Measurement”, vol. 134(1), pp. 277–286.

Hlebec V., Filipovič Hrast M., Kogovšek T. (2010), Social Networks in Slovenia: Changes during the Transition Period, “European Societies”, vol. 12, no. 5, pp. 697–717.

Hochschild A.R. (2017), Obcy we własnym kraju. Gniew i żal amerykańskiej prawicy, transl. H. Pustuła, Wydawnictwo Krytyki Politycznej, Warszawa.

Jaitman L., Scartascini C. (2017), Sports for Development, Inter-American Development Bank, https://doi.org/10.18235/0000962

Karp A. (2018), Estimating Global Civilian Held Firearms Numbers, “Small Arms Survey. Briefing Paper”, June 2018, http://www.smallarmssurvey.org/fileadmin/docs/T-Briefing-Papers/SAS-BP-Civilian-Firearms-Numbers.pdf (accessed: 15.02.2020).

Klein D., Marx J. (2018), Generalized Trust in the Mirror. An Agent-Based Model on the Dynamics of Trust, “Historical Social Research / Historische Sozialforschung”, vol. 43, no. 1(163), pp. 234–258.

Kornai J., Rothstein B., Rose-Ackerman S. (2004), Creating social trust in post-socialist transition, Palgrave Macmillan, New York.

Lee S., Jung M. (2018), Social Capital, Community Capacity, and Health, “The Health Care Manager”, vol. 37(4), https://doi.org/10.1097/HCM.0000000000000233

Lickiewicz J. (2006), Osobowość i motywacja osiągnięć osób trenujących sztuki i sporty walki, “Annales Universitatis Mariae Curie-Skłodowska. Sectio J, Paedagogia–Psychologia”, vol. 19, pp. 133–146.

Luhmann N. (1970), Soziologische Aufklärung. Aufsätze zur Theorie sozialer Systeme, Westdeutscher Verlag, Köln–Opladen.

Malinen S., Harju L. (2016), Volunteer Engagement: Exploring the Distinction Between Job and Organizational Engagement, “International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations”, vol. 28(1), pp. 1–21.

Murray D.W., Martin D., O’Neill M., Jason Gouge T. (2016), Serious leisure: The sport of target shooting and leisure satisfaction, “Sport in Society”, vol. 19(7), pp. 891–905.

Nowakowski K. (2008), Wymiary zaufania i problem zaufania negatywnego w Polsce, “Ruch Prawniczy, Ekonomiczny i Socjologiczny”, vol. 70(1), pp. 213–233.

Pawlak M. (2015), From Sociological Vacuum to Horror Vacui: How Stefan Nowak’s Thesis Is Used in Analyses of Polish Society, “Polish Sociological Review”, vol. 1(189), pp. 5–27.

Pratten S. (2017), Trust and the Social Positioning Process, “Cambridge Journal of Economics”, vol. 41(5), pp. 1419–1436.

Stempień J.R., Dąbkowska-Dworniak M., Stańczyk M., Tkaczyk M., Przybylski B. (2022), Particular Dimensions of the Social Impact of Leisure Running: Study of Poland, “Sustainability”, vol. 14(18), 11185, https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811185

Sztompka P. (1987), Social movements: structures in statu nascendi, “The Polish Sociological Bulletin”, no. 2, pp. 5–26.

Sztompka P. (2005), Socjologia zmian społecznych, Wydawnictwo Znak, Kraków.

Wiebe D.J. (2003), Homicide and suicide risks associated with firearms in the home: A national case control study, “Annals of Emergency Medicine”, vol. 41(6), pp. 771–782.

Yamane D. (2017), The sociology of U.S. gun culture, “Sociology Compass”, vol. 11(7), e12497, https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12497

Ziółkowski M. (2005), Utowarowienie życia społecznego a kapitały społeczne, [in:] W. Wesołowski, J. Włodarek (eds.), Kręgi integracji i rodzaje tożsamości. Polska, Europa, świat, Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar, Warszawa.

Zwarycz P.A. (2020), Czy strzelectwo jest sportem? Zarys problematyki strzelectwa sportowego w Polsce jako przedmiotu socjologii sportu, „Acta Universitatis Lodziensis. Folia Sociologica”, vol. 75, pp. 33–48, https://doi.org/10.18778/0208-600X.75.03

http://statystyka.policja.pl/st/wybrane-statystyki/bron/bron-pozwolenia/170176,Bron-pozwolenia-2018.html (accessed: 22.01.2020).

http://www.pzss.org.pl (accessed: 24.02.2020).

http://www.smallarmssurvey.org/fileadmin/docs/A-Yearbook/2007/en/Small-Arms-Survey-2007-Chapter-02-annexe-4-EN.pdf (accessed: 15.02.2020).

https://www.zzss.pl (accessed: 24.02.2020)

https://braterstwo.eu/tforum/t/71167/#amv (accessed: 5.02.2020).

https://communitydevelopmenttoolbox.weebly.com/community-capacity-building.html (accessed: 22.03.2020).

https://romb.org.pl/o-nas/ (accessed: 3.03.2020).

https://www.gazetaprawna.pl/artykuly/1107514,cbos-o-zaangazowaniu-polakow-w-dzialalnosc-spoleczna.html (accessed: 10.03.2020).

https://www.giz.de/en/worldwide/42673.html (accessed: 26.02.2020).

https://www.gov.pl/web/obrona-narodowa/konkurs-ofert-strzelnica-w-powiecie-2020-nr-32019-wwzs (accessed: 26.01.2020).

https://www.pobudka.org (accessed: 3.03.2020).

Statistics were done using: R version 4.2.1 (2022-06-23 ucrt), dplyr (v1.0.10; Wickham H., François R., Henry L., Müller K.), ggplot2 (v3.3.6; Wickham H.), psych (2.2.9; Revelle, W.), Excel Microsoft 365.

Strzelcy sportowi w Polsce: kapitał społeczny zaangażowania organizacyjnego a kontrowersje związane z dostępem do broni

Abstrakt. W artykule przedstawiono strzelectwo sportowe w Polsce na tle społeczno-politycznym. Społeczeństwo polskie po przełomie antykomunistycznym diagnozowane jest jako wspólnota, której brakuje kapitału społecznego, a w szczególności zaufania. W tym kontekście przynależność do klubów sportowych, traktowana jako forma zaangażowania społecznego, jest bardzo pożądana, gdyż rozszerza sieć współpracy społecznej. Jednak bycie strzelcem sportowym wiąże się również z dostępem do broni, co zawsze budzi kontrowersje, nawet jeśli w Polsce wskaźniki dostępu obywateli do broni palnej są niskie. Autorzy przeprowadzili badania (CAWI, N = 253) wśród strzelców sportowych w Polsce. Wyniki (opinie strzelców sportowych) analizowane są w trzech kontekstach: posiadania broni i stosunku do broni (motywacja do uprawiania strzelectwa sportowego), klubów strzeleckich (analiza organizacji strzeleckich w Polsce) oraz wizerunku strzelca sportowego (ocena wizerunku strzelców sportowych w społeczeństwie polskim). Podstawowym problemem, który wyłania się z analizy empirycznej, jest niejednorodna interpretacja strzelectwa sportowego przez samych strzelców. Strzelanie może być postrzegane zarówno w kategoriach sportowych (aktywność ukierunkowana na samodoskonalenie i współzawodnictwo), jak i jako aktywność o celach pozasportowych (patriotycznych, wychowawczych, obronnych). Różne definicje wspólnej aktywności mogą prowadzić do napięć interpretacyjnych (znaczeniowych), a ostatecznie do konfliktów w obrębie badanej kategorii osób.

Słowa kluczowe: strzelcy sportowi, dostęp do broni, kapitał społeczny, organizacje sportowe, zaangażowanie organizacyjne, sport dla rozwoju