https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8592-8980

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8592-8980

Abstract. The goal of this paper is to increase knowledge about the social definition of love in the context of an intimate relationship. The empirical material analyzed comes from Focus Group Interviews, Bulletin Board Discussions online, and representative research conducted using the CAWI method. The research was an exploratory study, and the analyzed material presents one thematic area concerning how participants understand love and the importance they attribute to it in the duration of an intimate relationship. The first part of the paper will present thematic areas related to the attempt to understand what love is that were indicated by the respondents at the stage of qualitative research. The second part of the article will present the typology of attitudes towards love on the basis of the analysis of data derived from quantitative research. The following types were distinguished: optimists in love, waiting for love, rationalists in love, distanced from love.

Keywords: love, definition of love, intimate relationship, falling in love, relationships, partnership, marriage, coupling.

In the everyday world, as in scientific argument, there is no single view of what love is. People name feelings, formulate definitions of love, or describe and interpret the trajectory of their intimate relationships, drawing on personal beliefs, cultural resources, and experiences. For sociologists, the issue of love as a factor that constitutes the main bonding force of an intimate relationship has been the subject of consideration for several decades (e.g., Szlendak 2002; Luhmann 2003; Konecki 2003; Bauman 2005; Giddens 2006; Kaufmann 2012; Beck, Beck-Gernsheim 2013a; Beck, Beck-Gernsheim 2013b; Illouz 2016). The focus of interest is most often placed on issues concerning the course of the process “from falling in love to breaking up”, i.e., among others, the social determinants of partner selection (Blackwell, Lichter 2000; Beck, Beck-Gernsheim 2013a; Beck, Beck-Gernsheim 2013b; Przybył 2017; Kalinowska 2018), the emergence and dynamics of love relationships (Blood, Wolfie 1960; Bauman 2005; Szukalski 2013; Kwak 2014; Schmidt 2015; Żadkowska 2016), the reasons for their breakup (Illouz 2016; Paprzycka, Mianowska 2019). However, there have been rare attempts to explain how people understand this concept, especially in the context of an intimate relationship. The discourse on love tends to be dominated by psychology, social psychology, and cultural anthropology. The considerations in this research communication are part of the stream of reflection on love and intimate relationships.

“The Social definition of love…” survey was conducted in three stages. The first one was conducted at the University of Łódź, the other two by the Market and Opinion Research Agency in cooperation with the Sympatia.pl website. The research was conducted at the turn of 2018 and 2019 and consisted of three stages – two qualitative studies and one quantitative study, which will be described in detail below. The main objective of the study was to ascertain the opinions of Poles on the ways of understanding love and its role in creating a long-term intimate relationship. The research was divided into five thematic blocks: (1) The social definition of love and its role in maintaining an intimate relationship, (2) Love as a time-changing process, (3) Love pillars, (4) Crises and challenges in love relationships, and (5) The search for love. The present text is a communication on the first topic, i.e., the social definition of love and its role in creating an intimate relationship. Some of the analyses derived from this research have already been deepened in previous studies (Czernecka 2020a; Czernecka 2020b; Czernecka 2020c; Czernecka, Kalinowska 2020). This communication is based on our own analyses and the report “How Poles love” (Osek, Żołądek 2019).

The first part of the research comes from the pilot research project “The social definition of love and the role it plays in the duration of a heterosexual intimate relationship”, in which eight focus group interviews (FGIs) were conducted with women and men separately, in age ranges determined based on the life cycle (Dobrowolska 1992): 19–25 years old, 26–37 years old, 38–55 years old, and over 55 years old. All study participants had a college or high school education and had experience in an intimate, loving relationship of at least two years. Most were in long-term, stable partnerships or marriages (the length of the relationship was proportional to the age of male and female participants of the study and lasted from 2 to 40 years). It is worth noting, however, that in proportion to their age, most of the focus participants were in relationships with a “long” duration. The meetings were conducted in 2018 and were exploratory in nature, with the goal of designing a broader study on the topic. Each session was attended by between five and seven people, which allowed for a more intimate research situation due to the intimate nature of the topic covered. The analyses made at this step were used to design the next two phases of the study.

The second part of the study, also qualitative, which was based on the results of the focus group research, was the design of focus group interviews conducted online (Bulletin Board Discussions (BBDs) online conducted on the Recollective platform). It allowed all participants of the study to comment on the threads and to get individual responses. The study lasted seven days, and each day was devoted to a different topic thread. The participants in this study included 20 heterosexual individuals who were in stable partnerships or marriages, 11 heterosexual individuals who were single, and 11 non-heteronormative individuals with experience in stable partnerships between the ages of 18–55. Analysis of the participants’ statements in this first and second phases formed the basis of the interview questionnaire.

The third part of the survey was quantitative, conducted using the CAWI method on a representative sample of 1016 Poles. The sample reflects the structure of Poles in terms of gender, age, education, and size of the their hometown: there is a larger percentage of women (52%), the majority of respondents are over 35 years of age (64%), about 30% of respondents have a secondary or academic education, about 2/3 of respondents live in cities, and 1/3 in rural areas. The majority of people (79%) declared they were in a formal or informal relationship, while 21% were single. Among those in a relationship, one-third were in a relationship lasting over 20 years. The vast majority of respondents were heterosexual – 90%, homosexuals made up 5% of the research sample, bisexuals 3%, and asexuals 2%. Tertiary education was observed in 29% of women and 21% of men, and basic vocational education in 38% of men and 26% of women. The size of the hometown did not significantly differ between men and women. Gender differentiated between those in relationships and those who were single – there were more single men (56%), while women were more likely to be in stable relationships (54%).

The concept of love itself is certainly multidimensional and evokes various associations or reflections, but this research focused on the concept of love in an intimate relationship (although there were also references to other relationships, which will be discussed later). In the first phase of the focus research, the participants attempted to define the word “love”. They referred to several areas. First, love is associated with physical closeness, intimacy, and tenderness. Here the statements referred to a feeling of togetherness, “we two”, belonging to each other, a desire to be together “here and now”. It is also a kind of “stopping the moment” in closeness, slowing down the pace of life with the other person, “becoming quiet”, feeling the uniqueness of the relationship. Love is also manifested through gestures of “love” such as cuddling, sleeping together (not in the sexual sense), and being attentive to the other person’s emotional and physical states. Second, it is mutual physical attraction, passion, desire, sex, and “chemistry between partners”. Love is equated with desire, including full acceptance of both the partner’s appearance and personality traits. The manifestation of love in an intimate relationship also includes a balance of giving and taking sexual pleasure. Many of the study participants emphasized that the feeling of emotional closeness heightens desire, increases adoring, “picking up” and dating the partner, despite the passage of years. It is also associated with self-discovery in the sexual area and fulfilling each other’s erotic fantasies. Thirdly, love is associated with good communication, i.e., understanding “without words”, empathic feeling for the other person’s situation, and the ability to accept their perspective on a given situation. Fourth, love is identified with friendship, loyalty, responsibility for the other person, with a “we couple”, rather than “me” and “I” separately. It is also caring for a loved one, giving a sense of security, honesty, trust, sharing problems and joys, selfless help, and psychological support in difficult moments. Fifth, love is based on “looking in the same direction” – sharing similar goals and values in life, worldview, and common plans for the future and dreams to be realized. Sixth, love manifests itself in partnership, shared housekeeping on an egalitarian basis or the division of duties according to the partners’ preferences, daily support in performing household duties “out of the need of the heart” and not “because it is necessary, I must”. It is also a shared responsibility for running the home, and the absence of an instrumental approach to financial matters. Seventh, love in a lasting relationship is also the ability to spend free time together, share passions and interests, joy and fun together. Eighth, the sense of freedom and autonomy in the relationship is important in true love, as well as the acceptance of different tastes and preferences of the partner, own time, and space for each partner’s individual activities. Ninth, love is also understood as the building of a couple’s shared history, based on similar experiences, emotions, and memories. It is the nurturing of this shared history by taking pictures and videos, and telling anecdotes from shared experiences.

The research from the second part of the qualitative phase of the BBDs showed that people living in long-term intimate relationships more often refer to their own experiences of being in a relationship – describing love through the prism of emotional experiences, everyday events, and mutual relations. In contrast, singles largely focus on the images of love, mainly romantic manifestations of it, admitting that “true love” is an experience still ahead of them. There are also differences in the perception of love depending on the age of the respondents: in thinking about love, the youngest participants (18–29 years) focus more on its first, most emotional stages (e.g., the desire to spend time together, being together), while the oldest respondents (over 40 years) to a greater extent, focus on love as a holistic experience, evaluated from the perspective of years of the relationship, where aspects such as understanding and care are important. These people define love more through the prism of the relationship of both people, worked out over the years, than individual behaviors or emotions.

As for the quantitative part of the study, the participants were asked to assign points to the various types of love (the study participants were given a total of 20 points, and they were to distribute them according to the rank of importance – the more points they assigned, the more important the type of love was for them). The most important turned out to be love for a partner – wife/husband (on average 6.5 points were assigned to this love – 75% of respondents indicated this love as the most important), love for children/grandchildren (4.7 points), parents and grandparents (3.3 points), God (2 points), nature/animals (1.8 points), and homeland (1.4 points). In the opinion of Poles, love is the most important element that contributes to building a happy relationship: 80% of respondents say that love is needed to create a lasting relationship (this is the most frequently indicated answer among all potential factors). As many as 49% of those who consider love to be a factor in building a relationship believe that it is the most important factor (it is more often ranked first by people with a heterosexual orientation – 51%, than LGBT people – 35%).

In both phases of the qualitative research, the respondents often talked about so-called “true love”, i.e., one in which both partners are forced to care about the relationship and about each other, which is connected to the deep feelings they share (cf. the concept of a “pure relationship” in Giddens 2006). In their view, it is a “refined” version of mature love, based on a deep knowledge of the characteristics and behaviors of the partner, with full understanding and acceptance of both their good points and bad points. It is also a common support in different dimensions and areas of life, facing everyday challenges, having a similar vision of life, plans, and expectations from the partnership. Often, when defining “true love”, there are descriptions that speak of “looking in the same direction”, responsibility for the relationship, and concern for the other person. These perceptions of love are consistent regardless of the gender or group to which respondents belong. As many as 77% of respondents say they experience love. However, in this aspect, differences appear depending on status, with those who are in relationships more likely to agree with this statement. The presence of such love is described in the context of shared life experiences and different spheres of life. “True love”, to be lasting and provide stability to the relationship, requires work and commitment. It may encounter difficulties and crises, but they are surmountable precisely thanks to the sincerity of feeling and remaining open to the partner.

In contrast, 62% of singles believe that the experience of “true love” is still ahead of them. In descriptions of this type of love, this group often lacks references to their own experiences. What dominates here are the expectations towards the relationship and ideas of what such love should look like and how it should manifest itself. It is worth noting that, in general, the vision of true love represented by singles coincides with that described by people in relationships. Differences are also visible between men and women – (heterosexual) women have a stronger conviction that they experience true love on a daily basis. On the other hand, men and women from the LGBT group are more likely to claim that the experience of true love is still ahead of them.

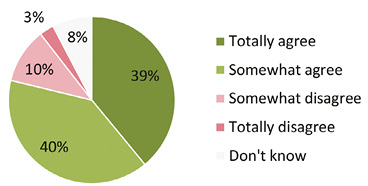

The analysis of part of the qualitative research shows that the experience of true love is mainly about working it out, the ability to cooperate and communicate between the two people involved. At the same time, 79% of Poles believe in love for the whole life – more often, such a belief is held by people in relationships, religious people, and women. The respondents often gave examples of true love “for life” that referred to family history – as an example, they mentioned couples such as their grandparents or parents, who managed to survive various crises and problems. The respondents were more likely to give examples of true love from their own environment than from pop culture.

Chart 1. I believe in lifelong love

Source: Osek, Żołądek 2019.

The respondents perceive a number of challenges on the way to true, lasting love. The first concerns functioning in moderately satisfying relationships, which are based on “pretending” that everything is fine and not looking for solutions to problems that arise. These types of situations are largely the result of a lack of commitment, a lack of willingness to cooperate, or a lack of love. The second challenge is giving up being in a relationship at the first problems that arise. According to the respondents, this is primarily due to fast and convenient lifestyles, resulting in an unwillingness to invest time and energy in developing a lasting relationship. As a result, people form many short-lived relationships or stay in a relationship that is not optimal for them.

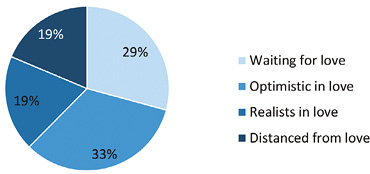

Chart 2. Types of attitudes towards love

Source: Osek, Żołądek 2019.

Love for this category of respondents is the basis of any long-lasting relationship; without it, there can be no happy relationship that is the result of joint work. The motto of this category of respondents is “I love and feel loved – love is happiness”. Thirty-three percent of the participants of the quantitative survey fell into this category; most of them are in a formal (67%) or informal relationship (24%), while the rest are single (10%). For them, love is the key aspect of life that gives it meaning (96% vs. 90% overall), and they are far more likely to believe that a lasting relationship should be based on love (88% vs. 47% overall) and that it is impossible to build a happy relationship without it (93% vs. 86% overall). They are more likely to believe in lifelong love (90% vs. 79% overall) and are also more likely to say that love will overcome any crisis (86% vs. 78%). They are most likely to say that sex without love is not satisfying (90% vs. 68% overall). They are more likely than others to admit that they love and are loved (91% vs. 81% overall). They are more likely to say that their relationship is based on partnership (strongly yes: 42% vs. 37% overall) and that they experience expressions of romanticism (75% vs. 69%). This category is more often represented by women (62% vs. 52% overall) and those with a college degree (29% vs. 25%), and more often by those who live with a partner (81% vs. 68% overall). They are a little more likely to be religious and practicing (49% vs. 44% overall).

This category of respondents had the motto “it is hard to find true love and persevere in a relationship, but still I wait for true love because I want to love and be loved”. This included nearly one-third of the survey participants (29%), of whom 32% are in a formal relationship, 21% are in an informal relationship, and 45% are single. Their main beliefs are that true love is hard to find in life (80% vs. 70% overall), love is more worry than joy (27% vs. 22% overall), and they are slightly less likely to believe in life-long love (74% vs. 79% overall). More often than for others, acceptance of their closest friends and family is important in building a relationship (18% vs. 11% overall). When it comes to relationship experience, 1/5 have never been in a long-term relationship (20% vs. 13% overall), are less likely to love and feel loved (66% vs. 81% overall), and are more likely to believe they have not experienced much love in their lives (39% vs. 24%).

Most people in this category are looking for a partner – 74% of singles are interested in forming a new relationship, and as many as 89% believe the experience of first love is still ahead of them (vs. 30%). Their relationship experience is primarily short-term (less than a year: 14% vs. 6% overall, 2–5 years: 26% vs. 18%). They experienced relationship crises more often (87% vs. 79% overall), and more often than in the population, it was a crisis of betrayal (24% vs. 19%) or a difference in values/expectations (24% vs. 16%), and they manage to overcome these crises less often. They more often met their current partner on a social networking site (16% vs. 9% overall). This category of people is dominated by younger people (from the group 19–25 years: 26% vs. 15% overall), they are more often single (55% vs. 34% overall), nearly half live with their own parents or their partner’s (if in a relationship 44% vs. 25% overall), and they are more likely to live in a single-person household (12% vs. 7% overall).

One in five respondents (19%) belongs to this category; the majority are in a formal (69%) or informal relationship (21%), although some singles (10%) also belong here. Their motto is: “love is important but not the most important thing; it is more important to know each other well than romantic excitement”. Love comes a little further down the list – they are most likely to believe that not every lasting relationship has to be based on love (89% vs. 43% overall), and they are more likely to agree that love is important primarily at the beginning of a relationship (39% vs. 32%). They are more likely to believe that love gives meaning to life (94% vs. 90% overall). They are more likely to say that sex without love is not satisfying (86% vs. 68% overall), and are more likely to say that the ability to compromise is important in building a relationship (59% vs. 52% overall). They are more likely to be in long-term relationships – 45% have been in a relationship for more than 20 years (vs. 32% overall). They are slightly more likely than others to have had 1–2 long-term relationships (79% vs. 72% overall), and are less likely than others to experience a display of romance in a relationship (61% vs. 69% overall). More often than others, they perceive partnership in a relationship as a commitment to living together (50% vs. 43% overall) but not necessarily an equal sharing of responsibilities, rather one that suits both parties (38% vs. 31%). They are more likely than others to experience a crisis related to the length of the relationship (29% vs. 22% overall) – 40% have managed to overcome it. This category is represented by the oldest participants – aged 45–65 (55% vs. 40% overall), living in 2-person households (36% vs. 25% overall), usually with a partner (77% vs. 68% overall). There is a slightly higher percentage of heterosexuals (95% vs. 90% overall).

One in five survey participants (19%) had the motto “love is a bonus; without love, you can live and enjoy life too”. Most were in a formal relationship at 61%, followed by an informal relationship at 25%, and 14% were single. Their main beliefs about love are that love is not essential to life and a relationship (13% do not think love gives life meaning vs. 5% overall). At the same time, they are more likely to believe that not every lasting relationship has to be based on love (50% vs. 43%) and that a happy relationship can be built without it (16% vs. 8% overall). They are unlikely to see love in a romantic, ideal way – they are more likely not to believe in love at first sight (35% vs. 28% overall), and they are less likely to believe in love for the whole life (73% vs. 79%). They believe that love will not overcome every crisis (26% vs. 15%) and feel that people who are not in a relationship have a harder life (59% vs. 39%). They believe that sex, even without love, is rewarding (92% vs. 22% overall). These individuals are more likely to have the experience of several relationships behind them: 3–5 relationships (21% vs. 14% overall). They are more likely than others to experience a crisis of over-commitment to work (20% vs. 14% overall). They are less likely than other segments to experience minor problems, such as lying to each other, serious arguments, petty bickering, or “quiet days”. This category is more often represented by men (62% vs. 48% overall), slightly less often among the youngest survey participants 19–25 years old (10% vs. 15% overall), and more often living with a partner (77% vs. 68%). They are a little more likely to be non-religious and non-practicing (21% vs. 13% overall).

The results may be a starting point for further in-depth research on the meaning of love and its role in intimate relationships. It is also worth looking at the typology of attitudes towards love and also deepen this research. In particular, love is indicated as the main factor that bonds an intimate relationship, determining its continuity and stability despite occasional crises. This topic fits into the context of reflections and analyses on the condition of the Polish family, marriage, and the number of divorces (Szukalski 2016). Perhaps it is worthwhile that love itself and the love life cease to be perceived by many sociologists as an issue that is too personal and individual, and that belongs to the mysterious and private world of largely irrational feelings, to be subjected to a broader sociological analysis. However, love is not only a private and very personal phenomenon; it is a universal emotion that is experienced by people regardless of the times and place in which they live, and how it is experienced, understood, and comprehended is strongly conditioned by the socio-cultural context.

Moreover, successfully living in a couple has become a marker of success or failure in life. And although we have many kinds of love – for oneself, family members, friends, nature, places, among others – love for one’s partner, husband/wife, based on will and emotional bonding, has been burdened in the process of individualization with the responsibility for a successful intimate life, creating one’s own love biography (Giddens 2006; Beck, Beck-Gernsheim 2013a; Illouz 2016). Personal life today has become like a never-ending “project” to be completed, which generates constant challenges and produces anxieties and fears about the survival or ending of a relationship (Bauman 2005). Individuals tend to attribute successes and failures in their love biographies to themselves, usually overlooking the context of deep-seated cultural conditioning, which is also worth examining.

Bauman Z. (2005), Razem osobno, transl. T. Kunz, Wydawnictwo Literackie, Kraków.

Beck U., Beck-Gernsheim E. (2013a), Całkiem zwyczajny chaos miłości, transl. T. Dominiak, Wydawnictwo Naukowe Dolnośląskiej Szkoły Wyższej, Wrocław.

Beck U., Beck-Gernsheim E. (2013b), Miłość na odległość. Modele życia w epoce globalnej, transl. M. Sutowski, Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, Warszawa.

Blackwell D.L., Lichter D.T. (2000), Mate selection among married and cohabiting couples, “Journal of Family Issues”, vol. 21(3), pp. 275–302, https://doi.org/10.1177/019251300021003001

Blood R.O., Wolfie D.M. (1960), Husbands and Wives: The Dynamics of Family Living, Free Press Glencoe, Oxford.

Czernecka J. (2020a), Miłość jako zmienny w czasie proces – opinie i doświadczenia kobiet i mężczyzn dotyczące przebiegu związku intymnego, “Rocznik Lubuski”, vol. 46(2), pp. 265–279.

Czernecka J. (2020b), Znaki miłości – praktyki tworzenia związku intymnego, “Kultura i Społeczeństwo”, vol. 64(4), pp. 115–135, https://doi.org/10.35757/KiS.2020.64.4.5

Czernecka J. (2020c), Definiowanie atrakcyjności – rola wyglądu i innych cech indywidualnych w doborze partnerskim w opiniach kobiet i mężczyzn, [in:] M. Bieńko, M. Rosochacka-Gmitrzak, E. Wideł (eds.), Obraz życia rodzinnego i intymności, Wydawnictwa Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, Warszawa, pp. 135–152, https://doi.org/10.31338/uw.9788323543572

Czernecka J., Kalinowska K. (2020), Semantyka miłości. Analiza metafor w narracjach kobiet i mężczyzn o uczuciach i związkach, “Przegląd Socjologiczny”, vol. 69(1), pp. 27–54.

Dobrowolska D. (1992), Przebieg życia – fazy – wydarzenia, “Kultura i Społeczeństwo”, no. 2, pp. 75–88.

Giddens A. (2006), Przemiany intymności. Seksualność, miłość i erotyzm we współczesnych społeczeństwach, transl. A. Szulżycka, Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, Warszawa.

Illouz E. (2016), Dlaczego miłość rani. Studium socjologiczne, transl. M. Filipczuk, Wydawnictwo Krytyki Politycznej, Warszawa.

Kalinowska K. (2018), Praktyki flirtu i podrywu. Studium z mikrosocjologii emocji, Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Mikołaja Kopernika, Toruń.

Kaufmann J.-C. (2012), Niezwykła historia szczęśliwej miłości, transl. A. Kapciak, Oficyna Naukowa, Warszawa.

Konecki K. (2003), Odczarowanie świata dotyczy także miłości, [in:] K. Doktór, K. Konecki, W. Warzywoda-Kruszyńska (eds.), Praca – Gospodarka – Społeczeństwo, Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego, Łódź.

Kwak A. (2014), Współczesne związki heteroseksualne: małżeństwa (dobrowolnie bezdzietne), kohabitacje, LAT, Wydawnictwo Akademickie Żak, Warszawa.

Luhmann N. (2003), Semantyka miłości. O kodowaniu intymności, transl. J. Łoziński, Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar, Warszawa.

Osek D., Żołądek W. (2019), Jak kochają Polacy? Raport wewnętrzny z badania (unpublished report – project internal materials), Agencja ARC Rynek i Opinie, Sympatia.pl.

Paprzycka E., Mianowska E. (2019), Płeć i związki intymne – strukturalne uwarunkowania trwałości pary intymnej, “Dyskursy Młodych Andragogów”, vol. XX, pp. 441–455.

Przybył I. (2017), Historie przedślubne. Przemiany obyczajowości i instytucji zaręczyn, Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu im. Adama Mickiewicza, Poznań.

Schmidt F. (2015), Para, mieszkanie, małżeństwo. Dynamika związków intymnych na tle przemian historycznych i współczesnych dyskusji o procesach indywidualizacji, Fundacja na rzecz Nauki Polskiej, Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Mikołaja Kopernika, Warszawa–Toruń.

Szlendak T. (2002), Architektonika romansu. O społecznej naturze miłości erotycznej, Oficyna Naukowa, Warszawa.

Szukalski P. (2013), Małżeństwo: początek i koniec, Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego, Łódź.

Szukalski P. (2016), Rozwód po polsku, “Demografia i Gerontologia Społeczna. Biuletyn Informacyjny”, no. 11.

Żadkowska M. (2016), Para w praniu: codzienność, partnerstwo, obowiązki domowe, Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Gdańskiego, Gdańsk.

Społeczne definiowanie miłości i jej roli w relacji intymnej. Typologia postaw wobec miłości

Abstrakt. Celem niniejszej publikacji jest poszerzenie wiedzy na temat społecznego definiowania miłości w kontekście związku intymnego. Analizowany materiał empiryczny pochodzi z grupowych wywiadów fokusowych, Bulletin Board Discussion on-line oraz badań reprezentatywnych prowadzonych metodą CAWI. Badania miały charakter eksploracyjny. Analizowany materiał przedstawia jeden wątek tematyczny dotyczący tego, w jaki sposób uczestnicy badania rozumieją miłość oraz jakie przypisują jej znaczenie w trwaniu związku intymnego. W pierwszej części artykułu zostaną przedstawione wątki tematyczne związane z próbą uchwycenia, czym jest miłość, które wskazali badani na etapie badań jakościowych. W drugiej części artykułu przedstawiona zostanie typologia postaw wobec miłości na podstawie analiz danych pochodzących z badań ilościowych. Zostały wyróżnione typy: optymiści w miłości, czekający na miłość, racjonaliści w miłości, zdystansowani do miłości.

Słowa kluczowe: miłość, zakochanie, związki, partnerstwo, małżeństwo.