https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8767-6702

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8767-6702

University of Social Sciences

Polish Geopolitical Society, ANZORA

e-mail: jowita.brudnicka@gmail.com

Abstract

In late December 2019 and early January 2020 the first cases of a new coronavirus occurred in Wuhan. It is a virus characterised by similarities to SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) and MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome). On January 25, 2020 the initial case of infection by SARS-CoV-2 caused the disease COVID-19 in an Australian patient who later died from it. During my PhD thesis defence in September 2018 I would not have thought that one of the possible security scenarios which I designed for the South Pacific region, related to epidemic threats, would soon come true. Despite some obvious and high indicators resulting, for example, from a geopolitical location in the vicinity of China, the probability of an epidemic outbreak seemed nigh unbelievable. This article focuses on societal security. It is impossible to make a solid analysis of an epidemic impact on societal security in various countries in a single article; therefore, I concentrate specifically on the case of Australia. The goal of this article is to explain how Australians cope with the epidemic and if they are prepared for a drastic change in their lifestyles. Do they put trust in governmental institutions? What issues appear to be main societal threats in Australian society during the pandemic? I conclude with thoughts about new societal directions that are going to be implemented should the scale of the pandemic persist. Due to limited length, my overview is not exhaustive; instead, it focuses on core findings about the condition of Australian society during the pandemic.Keywords: Australia, pandemic, national security, societal security, COVID-19

Day by day we observe and participate in diverse situations, see common reactions as well as differences in declared behaviors. Opinions about the epidemic can be shaped in varied ways depending on what people see in the streets, and what media resources they watch and read. It is estimated that about 16% of Australian society is epidemiologically at risk because of their 65-plus-age and 18.7% is 0–15 years old (Australian Bureau of Statistics qtd in. O’Sullivan et al. 134–151). In September 2020 there were no documented deaths cases caused by COVID-19 in the group of citizens aged up to 15 years old and there were 651 documented deaths cases for the group of citizens over 60 years old since January 20, 2020. Trust and its societal institution are crucial issues during the times of an epidemic crisis all over the world. Paul Dembinsky postulated long before the COVID-19 outbreak the necessity of coping with the lack of trust both to everything and everyone: citizens to government, institutions to central authorities etc. After the financial crisis in 2008 trust has been lost in a transnational way and rebuilding it was classified as a 21 st century challenge for modern democratic states (Brudnicka). Trust becomes even more central and critical during periods of uncertainty due to organisational crisis. Trust is, itself, a term for a clustering of perceptions (Chervany and Mcknight 3). The term belongs to a category of “societal values” which is wider than the definition of “value”, because it refers to most of the socially acceptable values which are actively present on a daily basis. Because of the very existence of values, there is the possibility to find a compromise in order to cooperate for the common good (Piwowarski 243).

Human beings are social creatures and feel the necessity to live among others from whom they expect to receive love, help, and satisfaction of their basic needs. The most well-known hierarchy of human needs is the so-called Maslow’s pyramid. Among the most basic needs, also known as the needs of scarcity, one can mention: physiological needs, security, and acceptance. Without those, one can never meet the needs of higher order which are needs of, inter alia: respect, recognition, and self-realisation. On a macro scale, in what can be identified as a society, there is a catalogue of needs of: acceleration of creating a modern civil society; including ensuring national security; creating individual security; control over the public administration; enhancement of positive national values; education; defence of the homeland territory (Skrabacz 186–189). In the 1980s Robert Ulman noticed the necessity of balancing the individual and state/national security (Ulman 130–133). An example of such balancing could be the decrease of military spending in favour of the social spending in many, especially European, state budgets. Many definitions of the term “societal security” can be summarised as: one of the categories of national security, focusing on ensuring existential foundations of living, ensuring the possibility of self-realisation (material and spiritual), especially creating workplaces, healthcare, and retirement insurance.

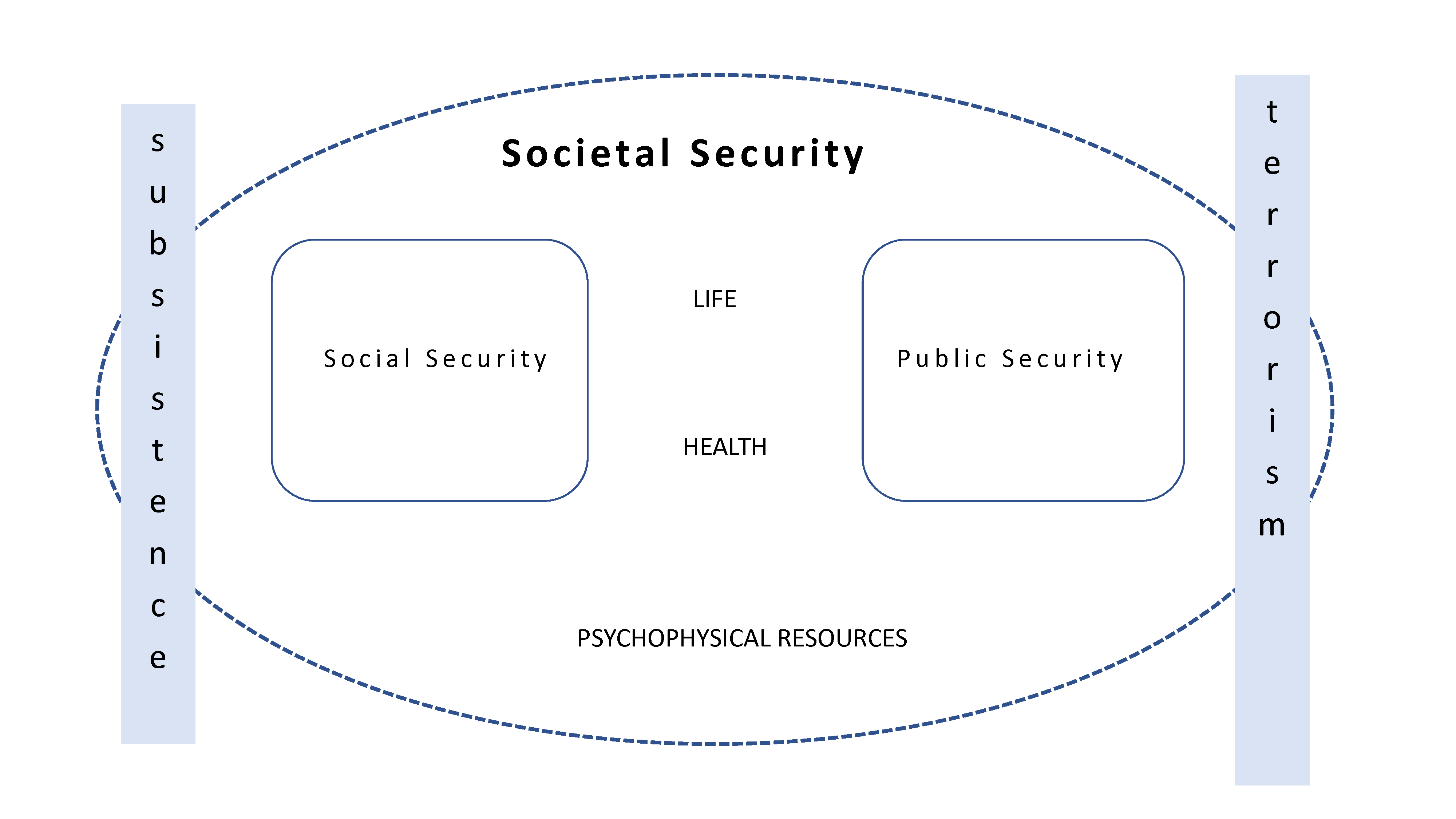

Some methodological findings have to be made. There is a need to separate the terms “societal security” and “public security”, because, until recently, those terms have not been used in widely understood security studies and their definitions’ ranges have been combined with some vital interests of a state. Societal security is associated with the reduction of probability of an undesirable phenomenon occurrence and the reduction of risks associated with issues of survival, quality of life, and national identity; while public security – directly with the protection of life, health, and property of citizens from the risk of terrorist attacks (Gierszewski 32).

Another existing term is “social security”. According to Cambridge Dictionary social security is “a system of payments made by the government to people who are ill, poor, or who have no job.[1] The Lexicon of Social Politics defines it slightly differently: social security is a state of freedom from paucity, the consequence of which is the lack of means of subsistence. The risks are: diseases, accidents at work, disabilities, senility, job loss, maternity, death of the breadwinner (Rysz-Kowalczyk). There are shared elements in the definitions, like the risk and the fact that where in social security they focus on material resources, in societal security they mention material but also psychophysical resources, originating in economy, policy, culture, etc.

These definitions show that a simple comparison of the societal impact of the epidemic situation on various countries has to include so many factors constituted for societal security, that it requires a separate monograph with explanations of, for instance, historical evolution of the term “social security”. The picture below shows a graphical representation of the mentioned terms’ dependencies.

The dotted lines mean that various securities’ fields have to maintain flexibility in crossing their competencies. It relates to a potential situation of, for instance, losing subsistence because of health issues caused by a terrorist attack. I am not a proponent of security sectors’ closed categorisation, so the dotted line being the frontier of societal security should remain open for free movement of national resources and institutional interactions.

On January 23, 2020 the passengers of a flight between Wuhan province and Sydney were screened on arrival, the outcome of which was the detection of four cases of coronavirus infected people within two days. Soon border restrictions were implemented: first for journeys for non-essential-reasons and then for non-citizens and non-permanent residents. Then came an automatic ban on public gathering of more than 500 people, and a rugby match and the Formula 1 Grand Prix 1 racing event in Melbourne were closed just hours before the start. Strict physical distancing measures introduced by the government were inconsistent in some opinions. The behaviour of Prime Minister Scott Morrison can be considered an example of such inconsistency: he ordered public restrictions and at the same time declared he was attending a major rugby league match. Such contradictory attitudes of a sports fan on the one hand, on the other, a policy decision maker, led to complex psychological and political outcomes. Josh Frydenberg from the Liberal Party of Australia defended the Prime Minister and said he “would have done the same given the opportunity” and “[that it was] good on him (the Prime Minister) for being passionate about his country and his footy”.[2]

There is no doubt that such a politician should lead by being an example during an extraordinary time like the period of a lockdown. Pictures from the stadium show he was sitting in a crowd without a mask, which is evidence of a measure of insensitiveness,[3] while other residents of Victoria were forced by law to live in isolation for the first six weeks. The bad reception of this incident in public opinion should not come as a surprise. Victorian Premier Dan Andrews neither wanted to comment nor begrudged him taking part in a “footy” celebration.

The not quite politically correct sequence of the Prime Minister’s actions affected the trust level especially in South Australia, where 62% of Australians are less appreciative of Scott Morisson’s efforts during the pandemic (OECD 17). Yet, at the same time, Queenslanders in 76% were satisfied with his work during the pandemic (Evans et al. 6): “Political trust has increased significantly in Australia in times of the COVID-19 pandemic and is strong in comparison with the trust levels in Italy, the UK, and the US: For the first time in over a decade Australians are exhibiting relatively high levels of political trust in the federal government (from 29 to 54%), and the Australian Public Service (from 38 to 54%)” (Evans et al. 4).

Evidently, the lack of decisive and consequent policy leadership causes a sense of anxiety and uncertainty. In the long run, it could generate a rise of doubts about possibly double standards and about the efficiency of the restriction measures taken. Considering every territory specified as an autonomic unit could also weaken central authorities. Doubts about the safety of children attending school form another example that could be perceived as a divergence in the government and states lines. In the first waves of the pandemic most Australian schools remained open with some reduction of attendance at the epidemic peak. Eventually, time of closure – and further reopening rules – of schools and early childhood education and care (ECEC) varied across state and territory jurisdictions, but the entire education system has faced some obstacles. For example, while 79% pupils from the Northern Territory went back to in class learning, only 3% in Victoria were in attendance (Sacks et al online). Normally there are four main ways of educating young Australians: based teaching and learning (in classroom); independent homeschooling; “school on air”, meaning implementation of some online equivalents; and school-led remote learning. The last one is based on giving students homework resources and assignments. Obviously, the popularity of this way of schooling increased during the pandemic but some new problems occurred. Those were problems like: restricted ability to monitor individual students’ progress, increased social isolation and reduced ability to support students’ well-being, differential levels of access to technology – including the Internet and devices – to support learning, interrupted learning support for the children with additional needs, and many others (Sacks et al. online). There are no unambiguous results of studies on how the virus affects children, but the numbers show that the symptoms of COVID-19, in comparison to other groups, are lower in range. The Lancet Child and Adolescence research showed that during the pandemic’s first wave “children and teachers did not contribute significantly to COVID-19 transmission via attendance in educational settings” (Macartney et al. online). But, in fact, most Australian students stayed at home despite the other educational modes’ disadvantages. Only those whose parents could not take care of them have been allowed to attend traditional classes. When the governmental restrictions wound back, Prime Minister Scott Morrison insisted that all the pupils should return to their educational institutions (Mercer online). Once again central and local political messages were discordant. It reflects the lack of responsibility or blurred responsibility for children’s health and for potential virus transmission from them to the teachers and the rest of school staff.[4] More specifically:

The trust level relating to Australian local authorities seems to be more acute in public opinion. Only 37% think that the state premiers are handling the coronavirus situation well. The highest performing state premier is Mark McGowan from Western Australia, while Steven Marshall from South Australia takes the second position. The poorest performing premiers at this time were Anastacia Palaszczuk from Queensland and Gladys Berejiklian from New South Wales.

The prolonged uncertainty which the parents felt about the process of their children heading back to school was surprising: “Every night we wait for the email. Sometimes it comes in the late afternoon, but many nights it doesn’t hit my inbox until 10 or 11 p.m. Eventually, it arrives, written by a beleaguered school principal letting us know that my son’s high school is still closed” (Letter 169 online).

Schools are not just places for learning. Children’s isolation will have lasting consequences, including diminishing children’s ability to continue their education. For some children schools are the places safe from abusive families and sometimes only educational institutions can provide them with a nutritious meal. Statistics are terrifying. While figures on violence against children remain difficult to collect there are studies showing that one in six women in Australia has experienced physical or sexual violence and one in four – emotional abuse. Even if only some of those women have children and some are single, there are still some “red flags”. A survey conducted by the Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education (FARE) shows that 20% of Australians purchased more alcohol before the pandemic and 70% of them drink more than usual. One third used alcohol daily and 28% reported that it helped to cope with stress and anxiety (FARE).

The Australian Psychological Society issued an information leaflet on coping with coronavirus anxiety, especially with regard to children. There are some basic precautions like: washing hands frequently, avoiding touching one’s face, staying home in case of feeling unwell, seeking medical help when experiencing the appearance of possible COVID-19 symptoms. There also is a tip to not to be scared of talking with children about the risks of the pandemic. All that parents should do is to maintain a calm manner of speaking, clarify all misunderstandings and rumors about it, say that feeling anxious is typical in such situations and that it is nothing to be ashamed of, and not to overwhelm kids with unnecessary information, and allow them regular contact with the people they are worried about.[5] From my pedagogical experience, I can only agree fully with these statements and add that it is very surprising how important it is to limit the exposure to the media, as some children are more sensitive to the suffering of others, especially those aged 7 to 13. One of my pupils was so worried about her grandmother’s health, that during an online lesson she replied to my question about her future dreams with “I just want my grandma to stay in good health during this pandemic.” It was a very heart-touching moment in a school teacher’s experience.

More than half a million Australians who experienced the aforementioned violence did so in the presence of their children (Family, Domestic vii-viii.). There are also additional concerns about the schools in lockdown: social isolation, decreased students’ well-being, and loss of education. There are still some challenges for the educational system to face: what role should the technology play in the delivery of all the modes of education and how will the technology landscape evolve to meet this role? How is the interruption in education caused by COVID-19 going to alter the learning trajectories of Australia’s children? How can those that have been disadvantaged be prevented from being left behind? (Sacks et al online)

The situation of students in higher education was similar. Over one million students and 100,000 staff employed by 43 universities were based at home. Many students had problems paying their bills because they lost their jobs during the lockdown period. “If, one month ago, someone had told me ‘in a month’s time you are going to be struggling to pay your bills, food and rent’, I wouldn’t have believed it”, said a student from Australia on an ABC podcast (Maslen online). The situation was difficult in places where the virus transmission was not declining, like in Melbourne. Even though the Victorian government provided funds in the form of one-off $1,100 for struggling international students in April 2020 and the number of students that obtained it was more than 21,000, it was still inadequate. The central government suggested that the international students who are not able to support themselves should go back to their homelands. It caused anxiety because of the possibility of the students losing visas and of them having no financial resources for the tickets home. And here we can once again see the dualism of political narration: foreigners are encouraged to leave Australia while national borders are closed. The options for returning home were disappearing. “I think I will lose [my] visa because the government also said just go home if you cannot support yourself”, a student said. “And then there is no ticket that I can afford. Maybe I will just be kicked out forcibly”, said an Australian student from Nepal (Henriques-Gomes online). On the one hand, they could feel unwanted as people who take over Australians’ workplaces, but at same time they do not want to lose their last chance to get a decent higher education in Australia. Six out of ten respondents chosen from international students said they had lost their jobs because of the pandemic and 15% of them had found a new job. Such indications could raise suspicion that foreign students are one of the most suffering groups in the labour market: “One in four respondents shared his or her bedroom with at least one other person who was not a partner, with 11% sharing a bedroom with two or more people. More than 200 respondents said they were forced to “hot-bed” – meaning to sleep in shifts, with the bed used by different people at different times. Despite such privations, one-sixth of respondents worried that they might face homelessness” (Ross online).

A problem other than financial ones is shared by other societal groups and it concerns the psychological aspect of the COVID lockdown and pandemic situation; namely, loneliness. It is estimated that 63% of respondents have felt lonelier since the epidemic outbreak. The life of international students appeared to be particularly precarious. A Sydney student said: ”I think no one would even know if I had died in my room if it wasn’t for a month when my landlady would come and ask for rent. Other than that, no one would even know.”[6] Such an opinion is shocking in all its brutal honesty.

In Australia one can find also pandemic outcomes more typical for this country than others because of its multicultural society. Some traditional groups can be misguided by rumored old ways of treatments without medical evidence. There is a huge need to create information channels in languages other than English, because the existing channels are not sufficient. Some cultural minorities are more vulnerable to racial abuse and this is especially true of Chinese, who are innocent victims of the geopolitical conflict between world powers. Prominent Chinese-Australians have written an open letter calling for an end to racial abuse towards Asian–Australians:

Family is one of the most important factors when facing racism, poor financial situations, etc. Considering how people have gotten through difficulties in the past, the family is the societal institution that could provide the greatest support, also by reminding people that many problems related to COVID-19 are limited. Respectful and open conversations about mental and physical concerns can be fundamental in these difficult times.[7] Depression and anxiety strongly affect family ties. These disorders affect adults and children, regardless of gender. In times of the pandemic there are some crucial matters: first of all, to take care of already diagnosed patients with mental problems, and secondly, to sensitise the entire society in order to primarily pick up on symptoms of mental illnesses, such as a drop in energy, increased fatigue, apathy, anxiety felt in the mornings (which doctors call “free flowing anxiety” – one is anxious of the coming day). It also means feeling indecisive, problems with concentration, thinking badly about one’s self. If such a state lasts for more than two weeks, one should start looking for help from a specialist. In these moments people in our nearest environment play a crucial role. This means family and friends, as someone stuck in a toxic situation is not able to evaluate a potential problem in an objective way. Mental illnesses are very common and not limited to depression. They could become a mix of disorders: depressive ones, anxiety and substance abuse disorders. One in five (20%) Australians aged 16–85 experience mental illnesses at any age in this range. Of the 20% of Australians suffering from a mental illness in any year, 11.5% suffer from one disorder and 8.5% suffer from two or more disorders (Australian Bureau of Statistics). The National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing (NSMHWB) of The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) provides the most comprehensive (albeit dated) estimates for mental disorders of Australian adults both over their lifetime and during the last 12 months. The Department of Health has said that there are no plans to fund another survey on mental health by the ABS (Cook online). During the time of pandemic rethinking such a statement should be highly recommended. A report commissioned by the Royal Australian & New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (RANZCP) estimated that in 2014 the costs of severe mental illnesses in Australia were $56.7 billion per year. This includes the direct economic costs of severe mental illness resulting from the use of health and other services, as well as indirect costs resulting from loss of productivity, as some ill people are unable to work (Cook online). Responsibility for funding and regulating mental health services in Australia is shared between the Australian, state and local governments. However, as stated in the Parliamentary Library publication, Health in Australia: a Quick Guide, their respective roles are not always transparent. On August 4, 2017, the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) agreed to the Fifth National Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Plan which established a national approach for collaborative government effort from 2017 to 2022. According to all strategic documents there are two main groups in which mental illnesses caused by the pandemic could be extremely difficult to fight: the homeless and Aboriginal community.

Recent information on homelessness was taken from the study conducted by the Australian Bureau of Statistics in 2016.[8] Since 2011, the number of homeless people in Australia has increased by 13.7% and it is estimated at 116,427 cases. 20% of these are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, which is a decrease, compared with 26% in 2011. In Australia’s capital cities during the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak a massive operation got underway, aiming to take about 7000 homeless people off the streets (Knight online). The homeless were supposed to find accommodation in empty student dormitories, hotels, and motels. Jenny Smith – the chair of Homelessness Australia[9] stated: “I’m not aware of it happening on this scale before” (Knight online). The CEO of Launch Housing in Melbourne – Bevan Warner – said: “It’s shown that homelessness is solvable. For the first time, we’ve got an opportunity to work with them from rough sleeping into a permanent home and a good life” (Knight online)..

The profile of the people who need housing also changed and it is estimated that there are more than 160 000 families waiting for an affordable place to live. As the Federal Minister for Housing, Michael Sukkar, comments: “Every year the Federal Government provides more than $6 billion in Commonwealth Rent Assistance and support to the states and territories to deliver social housing through the National Housing and Homelessness Agreement” (Borys online).

There are also expert opinions stating that dealing with homlessness by fighting the after-effects comes at higher costs than solving the problem before people get on the streets (Borys online). Shocking material about homelessness during the pandemic in Australia is shown on the Youtube channel “Invisible People”[10] where a wider audience can learn about the causes of homelessness.

Aboriginals are three times more likely to experience high or very high levels of psychological distress than other Australians, are hospitalised for mental and behavioural disorders at almost twice the rate of non-Indigenous people, and have twice the suicide rate than that of the rest of Australians. The breadth and depth of such high levels of distress of individuals, their families, and their communities is profound. The NSW Health plan mentions the most important issues to consider when developing pandemic services for Aboriginal communities:

It is quite clear that a strong link between financial resources and mental problems exists. The Australian government has established loans for small- and medium-sized businesses in a package of USD 66 billion. Because of the early social distancing measures and other precautions taken in New Zealand and Australia, it was possible to create a safe zone (social bubble) for the movement of people and goods between those two states (the trans-Tasman travel initiative). The special relationship between Australian and New Zealand is established not only in the tourism sector, but also in terms of societal cohesion: about 570,000 New Zealanders live permanently in Australia. A business partnership has been established between the local and central authorities.

The post-COVID-19 “policy settings that were finally settled upon by the government are looking as though they will reflect a complex mix of ideology and pragmatism and are likely to provide the issues on which the next national election is contested” (O’Sullivan et al. 145). Despite various problems in the area of societal welfare it does not seem that societal trust, understood as vertical trust in line authorities and habitants, was damaged to any great extent. That is why the results of trust level (according to media coverage) are even more interesting. Only 20% of people have confidence in social media; 39% in television; a little less in newsprint and the highest level of trust is located in the radio. Those numbers are separate from the confidence levels expressed in the opinions of scientists and experts. In the table below the general trust survey results are presented.

| Australian services | Level of societal trust (%) |

|---|---|

|

Government |

29–54 |

|

Army |

78 |

|

Health services |

77 |

|

Police |

75/p> |

|

Social media |

19–20 |

|

Television |

32–39 |

|

Newsprint |

29–37 |

|

Radio |

c. 38–41 |

|

Experts’ opinions |

77 |

Source: Based on data, Evans et al. in: Political Trusted Democracy in Times of Coronavirus: Is Australia Still the Lucky Country? (4–5)

There are some key issues involved in reducing COVID-19’s negative impact on society, like expert knowledge-based political and administrative decisions as well as a sufficiently financed, effective healthcare system. There is also a need for accompanying elements, such as public trust that guarantees respect for the law and for its implementation. According to the report titled “Political Trust and Democracy in Times of Coronavirus: Is Australia still the Lucky Country?”, it can be assumed that Australians put a lot of trust in their homeland’s public institutions. But some general conclusions, such as the following, have to be made.

Australia is an island country and the implicated isolation can be favourable for virus infection prevention. The way of life in Australia – because of the great area it covers and of families living in houses rather than apartments – also looks different than in Europe. Australia is characterised generally by a warmer climate, as well. While I am not an advocate of comparing any European country to Australia, it should be mentioned that a cluster of large coastal cities could create demographic conditions similar to those in Europe. The double hierarchy of government authorities was a crucial issue in fighting COVID-19. Thanks to that, state governments could apply an appropriate model of crisis management including specifying geographical and urban conditions. In comparison to the situation in New Zealand, immediate political decisions concerning the pandemic in Australia led initially to almost zero virus transmission (Thompson online).

The public quite well receives the restrictions implemented by the local and central authorities. It is tempting to say that they have to adopt three evaluation criteria: institutional trust statistics, the number of anti-lockdown protests, and reactions to “controversial” technological innovations that are supposed to help COVID-19 prevention. First, according to the discussed report titled “Political Trust and Democracy in Times of Coronavirus: Is Australia Still the Lucky Country?”, it seems that Australians put trust in their institutions. Confronting it with other sources of information – first Google search results of the phrase “trust Australia Covid” – proves it being high and even higher when compared to the delayed survey on the subject of trust in Australian society: “The ANU survey found between January and April, 2020 confidence in the federal government surged from 27% to 57% and confidence in the public service recovered from 49% to 65% as Australians gave a thumbs up to the coronavirus response” (Karp online).

Moreover, there is a high level of trust in Australian statistics compared to

COVID-19 world surveys. While data management in other countries is perceived as “sloppy”, Australia’s Chief Medical Officer said: “The only numbers I have total faith in are the Australian numbers” (Ross “How Do We?” online).

Protests in Australia against lockdown started in the first days of September 2020 and were repeated at the end of November in Melbourne. Hundreds of people clashed with the police. In effect 16 people were arrested and 96 fines were issued, for offences including not wearing a mask, violating public gathering directions, travelling more than 25 kilometres from home, assaulting the police and failing to state one’s own name and address.[12] Nevertheless protests under the slogan “Let us work” do not seem to lead to chaos spreading throughout Australian society.

That non-rebellious character was reflected also in the eager use of the CovidSafe App that is supposed to track people who’ve had possible contact with the virus. The government recommends installing such an app but it is voluntary. About 1 million people downloaded the app in the first days. Unfortunately, it was not possible to avoid some misunderstandings, the consequences of which were unsuccessful communication of the infection and – in the long run – a possible collapse of trust. The trust level in the central authorities differs from that in the local authorities.

There are a couple of groups in society that are more fragile than others during a pandemic. In Australia, like in any other country, there are seniors, children, and people with comorbidities, but there are also groups specific to Australia, like Aborigines and immigrants looking to change their lives thanks to education and work in Australia. These communities need help in various areas from grocery shopping, to economic prospects, to mental health. The last factor was an issue that was brought to the general public before the pandemic even broke out. Nowadays the isolation, lockdown and obvious economic deterioration of lifestyle will result in mental problems of varying severity to a much wider extent.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing: Summary of Results, 4326.0, 2007. ABS: Canberra 2009.

Brudnicka, J. „Zamiast zakończenia…Państwo w perspektywie rozwoju.” Wybrane aspekty funkcjonowania państwa w XXI wieku. Ed. W. Trybuł. Warsaw: Semper, 2019.

Chervany, N.L., Mcknight D., Meanings of Trust. University of Minnesota MIS Research Center Working Paper Series, 1996.

Evans, M. et al. Political Trust and Democracy in Times of Coronavirus: Is Australia Still the Lucky Country? Museum of Australian Democracy, University of Southampton, Trustgov, University of Canberra, Institute of Governance and Policy Analysis, 2020.

Family, Domestic and Sexual Violence in Australia: Continuing the National Story. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2019.

Gierszewski, J. Bezpieczeństwo wewnętrzne. Zarys systemu. Warsaw: Difin, 2013.

O’Sullivan, D., Rahamathulla M., Pawar M. “The impact and implications of COVID-19: An Australian perspective.” The International Journal of Community and Social Development 2.2 (2020): 134–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/2516602620937922

Piwowarski, W. Socjologia religii. Lublin: KUL, 1996.

Rysz-Kowalczyk, B. Leksykon polityki społecznej. Warszawa: Aspra JR F.H.U., 2007.

Skrabacz, A., Organizacje pozarządowe w bezpieczeństwie narodowym Polski, rozprawa habilitacyjna, Warszawa 2006.

Ullman, R. “Redefining Security.” International Security 8(1) (1983): 129–153. https://doi.org/10.2307/2538489

What does trust mean? “(…).holding a positive perception about the actions of an individual or an organisation” OECD, (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) Trust and Public Policy: How Better Governance Can Help Rebuild Public Trust, OECD Public Governance Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264268920-en

Alvaro, A. Tasmanian Students Start Back at School Toaday, We Explain How It Will Work. Web. 7 July 2021. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-05-25/tas-monday-back-to-school-explainer/12279400

Australian Government Department of Health. Covid-19 Deaths by Age Group and Sex. Web. 16 May 2021. https://www.health.gov.au/resources/covid-19-deaths-by-age-group-and-sex

Australian Psychological Society. Coronavirus (Covid-19) Anxiety and Staying Mentally Healthy. Web. 7 July 2021. https://www.psychology.org.au/getmedia/5f9cc6d4-ad5c-4b02-8b7f-d4153cb2ba2b/20APS-IS-COVID-19-Public-Older-adults_1.pdf

Australian Psychological Society. Tips for Coping with Coronavirus Anxiety.Web. 7 July 2021. https://www.psychology.org.au/getmedia/5a4f6500-b5af-4482-9157-5392265d53ce/20APS-IS-COVID-19-Public-P2_1.pdf

Bermingham, K. All WA school students ordered to return to school, marking end to coronavirus absences. Web. 7 July 2021. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-04-22/sa-parents-urged-to-send-children-to-school/12174872

Borys, S. Federal Government warned about rising risk of homelessness from

COVID-19. Web. 7 July 2021. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-09-28/government-warned-of-homeless-risk/12709156

Cook, L. Mental Health in Australia: A Quick Guide. Web. 7 July 2021. https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp1819/Quick_Guides/MentalHealth

Fang, J., Yang S. Chinese-Australian family targeted over coronavirus receives outpouring of support. Web. 7 July 2021. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-04-23/chinese-australian-family-racist-coronavirus-racist-attack-speak/12178884

FARE. Many Australians using more alcohol and worried about household drinking. Foundation for Alcohol Research and Education. Web. 7 July 2021. https://fare.org.au/many-australians-using-more-alcohol-and-worried-about-household-drinking/

Heaney, Ch. All WA school students ordered to return to school, marking end to coronavirus absences. Web. 7 July 2021. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-04-20/schools-open-nt-coronavirus-restrictions/12157006

Henriques-Gomes, L. ‘If I Give Up, All My Effort Is for Nothing’: International Students Thrown into Melbourne Lockdown Despair. The Guardian. 12 August 2020. Web. 7 July 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/aug/12/if-i-give-up-all-my-effort-is-for-nothing-international-students-thrown-into-melbourne-lockdown-despair

Homlessness Australia. Web. 7 July 2021. https://www.homelessnessaustralia.org.au

Josh Frydenberg Defends PM’s Appearance at NRL Game Amid Coronavirus Pandemic. The New Daily. 13 July 2020. Web. 21 June 2021. https://thenewdaily.com.au/news/2020/07/13/frydenberg-morrison-rugby-coronavirus/

Karp, P. PM’S Department Delayed Survey Showing Australians Don’t Trust Government. The Guardian. 19 August 2020. Web. 17 July 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/aug/19/australians-trust-public-service-government-covid

Knight, B.. Has the coronavirus pandemic proved that homelessness is solvable? Web. 5 July 2021. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-06-08/housing-homeless-in-pandemic-has-worked-lets-make-it-permanent/12330442

Laschon, E. et al. All WA school students ordered to return to school, marking end to coronavirus absences. Web. 7 July 2021. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-05-14/all-wa-students-to-return-to-school-as-coronavirus-absences-end/12245712

Letter 169. What Can Vistorian Schools Teach America About Reopening? The New York Times. Web. 8 July 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/30/world/australia/melbourne-schools-lessons-america.html

Macartney, K. et al. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in Australian educational settings: a prospective cohort study. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health 4.11 (2020): 807–816. Web. 21 June 2021. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanchi/article/PIIS2352-4642(20)30251-0/fulltext

Mercer, P. Australian Children to Gradually Return to School As COVID-19 Controls Ease. Web. 21 June 2021. https://www.voanews.com/covid-19-pandemic/australian-children-gradually-return-school-covid-19-controls-ease

‘No One Would Even Know if I Had Died in my Room’: Coronavirus Leaves International Students in Dire Straits. Web. 7 July 2021. https://theconversation.com/no-one-would-even-know-if-i-had-died-in-my-room-coronavirus-leaves-international-students-in-dire-straits-144128

NSW Government website. Pandemic Planning with Aboriginal Communities.

Web. 7 April 2021. https://www.health.nsw.gov.au/pandemic/Pages/engaging_aboriginal_communities.aspx.

Police arrest demonstrators at Melbourne protest against Victoria’s coronavirus lockdown restrictions. Web. 1 April 2021. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-10-23/anti-lockdown-protesters-converge-on-melbourne-shrine/12706900

Ross, J. Foreign Students ‘Disproportionately Impoverished’ by Pandemic. Times Higher Education. 10 August 2020. Web. 7 July 2021. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/news/foreign-students-disproportionately-impoverished-pandemic#%20

Ross, J. How Do We Know Statistics Can Be Trusted? We Talked to the Humans Behind the Numbers to Find Out. Web. 7 September 2021. https://theconversation.com/how-do-we-know-statistics-can-be-trusted-we-talked-to-the-humans-behind-the-numbers-to-find-out-148339

Sacks, D. et al. Covid-19 and Education: How Australian Schools Are Responding and What Happends Next. Web. 21 June 2021. https://www.pwc.com.au/government/government-matters/covid-19-education-how-australian-schools-are-responding.html

Scott Morrison Criticised for ‘Insensitive’ Outing during Victorian Lockdown.

Web 21 June 2021. https://7news.com.au/sport/rugby-league/scott-morrison-criticised-for-insensitive-outing-during-victorian-lockdown-c-1175489

Social security. Web. 16 May 2021. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/social-security

Thompson, J. et al. Modelling Victoria’s Escape from Covid-19. Web. 7 July 2021.

https://pursuit.unimelb.edu.au/articles/modelling-victoria-s-escape-from-covid-19