Abstract. Regional development and spatial planning in Croatia are organised as parallel planning systems regulated by different legislations and coordinated by two ministries, the development of which has been strongly influenced by the European Union (EU). In the last two decades, the intensive development of strategic documentation on a local, regional, and national level regarding diverse territorial governance aspects has had extensive analytical scope but little potential for implementation due to the overlapping of responsibilities and disconnected budget and implementation instruments. The Integrated Territorial Investments (ITI) mechanism of implementation contributed to the understanding of multifaceted territorial governance beyond strategic document drafting. This paper analyses the first phase of ITI implementation in Croatia, i.e. the processes which unified functional urban areas, creating the possibility to develop joint management structures and strategies, integrated projects, and common participative planning models.

Key words: strategic spatial planning, urban planning, territorial governance, ITI mechanism, Croatian case-studies.

This paper examines strategic spatial urban planning in Croatia considering the Regional Development Act, the new Act on the System of Strategic Planning and Development Management of the Republic of Croatia, as well as legislation related to land use planning. The authors discuss the link between traditional land use planning and strategic planning focusing on the impact of the ITI as an opportunity in the development of strategic spatial planning. The main objectives of the paper are as follows:

All four objectives are mutually intertwined and tackled in the paper, as are regional development, urban development, strategic planning, and the ITI mechanism in Croatia. The authors showcase the impact of EU policies on the development of territorial governance models and outline specific lessons learned from the implementation process. Likewise, the article provides an overview of strategic planning in Europe and Croatia to avoid possible future shortcomings and build upon the transferability of results in the changing contexts of other countries of the Western Balkan Region. Thus, Zagreb and Zadar are presented and compared as two urban areas with different characteristics (geographical, demographical, political, social, etc.).

The methodology comprises a thorough review of literature and legislation related to strategic and spatial planning, urban planning, territorial governance, and ITI. Relevant data was collected on European, national, and sub-national levels (office research methods), while informal interviews with public servants and officials in the sector of strategic planning and ITI implementation were conducted and used as input in the research. The process included relevant actors on the national level but more importantly actors at the local level directly involved in implementation activities with extensive experience in the field. The authors’ expertise in the field of sustainable urban development and spatial policies in various territorial development issues, with a specific focus on sustainable urban development and territorial cohesion (including great involvement in the preparation and implementation of the ITI mechanism), proved crucial for understanding the connections and (missing) links in the system. Preliminary conclusions had been discussed in another round with the interviewees before the final conclusions were made.

Fig. 1. Methodological and analytical illustration

Source: own work.

The concept of governance has been the focus of academic debates in recent decades, the shift from government to governance, in particular. Governance refers to the emergence of overlapping and complex relationships, involving “new actors” that are external, who are not only professional politicians, and the term government refers to the dominance of (state) power organised within a traditional hierarchy (Painter and Goodwin, 1995).

Territorial governance can be defined as the process of organisation and coordination of actors to develop territorial capital in a non-destructive way in order to improve territorial cohesion at different levels (Davoudi et al., 2008) and this paper mostly focuses on the level of urban areas and agglomerations.

Strategic spatial planning in Western countries started to evolve in the 1960s and 70s to a system of comprehensive planning, while the shift from urban and regional planning practices to focusing on projects occurred in the 1980s. The focus was particularly on projects regarding the revival of rundown parts of cities and regions, and on land-use regulations (Albrechts, 2004). This paragraph is a terse summary of EU territorial and urban planning approaches in recent decades.

Land-use planning can be defined as the proposed use of land according to policies and regulations. At the EU level, it mainly focuses on municipalities or functional urban regions. Traditional land-use planning controls land use through a zoning system. It regulates land use and directs development by enabling desirable activities and ensuring that undesirable development does not occur (Albrechts, 2004). However, there is a gap between strategic and traditional land-use planning which we shall discuss in more detail later in the text.

Strategic spatial planning (SSP) focuses on a limited number of strategic key issue areas and has a critical approach to the planning area with a detailed analysis of resources, potentials, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (Bryson and Roering, 1988; Poister and Streib, 1999). It identifies stakeholders, considers deep involvement during the planning process and develops a long-term vision (Healey, 1997). Moreover, strategic spatial planning designs plan-making structures (Mintzberg et al., 1998) and develops decision frameworks for influencing and managing spatial change (Faludi and Van der Valk, 1994; Healey, 1997). It is focused on objectives, priorities, actions, and projects with measurable results (Faludi and Korthals Altes, 1994). According to Albrechts (2004), new, ‘alternative’ strategic planning is a democratic, open, selective and dynamic process that envisions and frames problems, challenges, and short-term actions within a revised democratic tradition.

Furthermore, SSP’s new syntax in is sustainable development that is linked to the Cohesion (regional) policy of the EU with an aim to achieve a balanced development. It emphasises the need for change in formulating development guidelines and policies through an integrated approach to use limited resources in the most optimal way. In the 2014–2020 programming period the importance of territorial cohesion has been recognised, a fact which led to the articulation of territorial cohesion aiming to strengthen the specifics of each area. Development specifics of the European territory and the territorial dimension are important in achieving the Europe 2020 strategy goals. Thus, the Territorial Agenda 2020 (TA 2020) was elaborated as a document emphasising the need for integrated, polycentric and balanced territorial development, as well as the role of cities as its generators. The TA 2020 transformed the perspective of competitive and sustainable Europe to the concept of smart and sustainable Europe. Therefore, the economic policy has become more important than spatial planning, which indirectly caused the decrease in regional disparities. The 2030 TA follows this direction (Geppert, 2021). In addition, since the majority of the EU’s population lives in urban areas (including functional regions and peri-urban areas), their significance in development planning has also been recognised through The European Urban Agenda. The need for this new and integrative approach was recognised already in 1999 in the European Spatial Development Perspective (ESDP), a document representing the spatial development policy framework. Some of the main goals of the ESDP refer to the development of polycentric and balanced urban systems and strengthening partnerships between urban and rural areas.

Strategic urban development planning cannot solely consider the planning of cities, but has to encompass wider urban areas and zones shaped through stratification of historical and spatial processes merging into one another. Although these urban areas are common in Europe, Albrechts (2000) conveyed relevant questions in relation to polynucleated urban areas.[1] The harmonisation of development processes of city centres and their functional areas leads to cooperative advantages and multiplier effects at the regional, national, and international levels. (Kaczmarek and Kociuba, 2017). As stated above, complex urban areas comprise of different social, administrative, and economic structures with unclear boundaries in need of collective solutions for various problems connected to management and spatial planning. Since it is a relatively new concept, some organisational and administrative problems and discrepancies can occur, as it is the case in some countries with more than two administrative levels. Thus, Kaczmarek and Kociuba (2017) have considered the management of functional areas of large cities as the greatest and most difficult challenge which the public policy and territorial management face.

Traditional land use planning seems unfit for solving the complexity of planning the development of urban areas and there is a need for a different type of planning aimed at intervening more directly, coherently and selectively in social reality and development (Albrechts, 2001). This new SSP can be considered as a clear shift from traditional land-use planning to a process providing opportunities to debate relevant topics.[2] Tasan-Kok et al. (2019) have discussed how contemporary urban planning dynamics are based on negotiation and contractual relations creating fragmented planning processes, whereas according to Piere (1999) the changing forms of governance have been transforming urban planning towards a process that exploits various managerial instruments. Other authors also argue that the SSP is not a well-defined process, rather a framework for: (a) different approaches to planning[3] (Persson, 2020), and (b) a set of ‘concepts, procedures, and tools that must be tailored carefully to whatever situation is at hand’ (Albrechts, 2004). According to Healey (2009) the significance of strategic planning lies in shaping future development trajectories that include understanding current societal trends and what is desirable, possible and at stake. Hence, SSP borrows concepts and methods developed in business management (see Mintzberg, 1994) and by focussing on local and regional economic growth it makes cities or municipalities attractive for inward investment.

In recent years, there focus has increased on the programming of financial operations from EU Structural Funds to the specific role of cities and their functional areas, especially through ITI. ITI is discussed in more detail further in the text, as it is closely related to strategic planning in Croatia.

In 1997, the European Commission published the Compendium of Spatial Planning Policies and Systems in the European Union, in which spatial planning systems were grouped into four categories according to the planning tradition.[4] That classification was updated in 2006. However, it is still difficult to make a clear distinction between the categories. Nadin and Stead (2008) have stated that there is a convergence of today’s planning systems due to social changes that occurred in the process of transition and Europeanisation. This is especially true for the countries of Central, South-eastern, and Eastern Europe.

Urban planning in Croatia during the second half of the 20th century (in the socialist regime) could be divided into five phases over which urban planning experienced decentralisation from the federal to the communal level, advancements in public participation, and the involvement of environmental considerations in the decision-making process.[5] Frequent changes and reforms of urban planning acts had a great impact on the system and resulted in practicing planning in ever-changing conditions. After its introduction in 1949, the general urban plan has remained the main document of urban planning to date.[6] Furthermore, the detailed urban plan has also been an important legacy of socialist planning. It is interesting that socialist planners cultivated active engagement with western planning theories and methods, so Croatian planning was in line with Western Europe and the USA, and the public participation and environmental concerns were introduced (at least on paper) at the same time as in other western countries. However, multi-disciplinarity was delayed by several decades and one could ask whether it is being practiced today at all. Another important remnant of the socialist system are legal urban planning procedures and tools that are still being used in modern Croatia (Tandarić et al., 2019).

The current Croatian planning system is determined by the Physical Planning Act (Official Gazette, 153/13, 65/17, 114/18, 39/19, 98/19) and its by-law acts. Following the principle of an integrated approach based on a comprehensive view of the use and protection of space and an organised hierarchical system (national, regional, and local spatial plans), the Croatian spatial planning system can be considered as the model of a comprehensive integrated approach. Land-use planning can be considered an integrated and qualitative way of planning with the location, intensity, and the form of land development required for the predefined functions such as housing, industry, recreation, transport, society, agriculture, etc. (Chapin, 1965; Cullingworth, 1972).

As different acts define different forms of planning, several ministries are responsible for their implementation (Table 1).

| Sector | Name | Institution |

|---|---|---|

| Physical/spatial planning | Physical planning act (OG 153/13, 65/17, 114/18, 39/19) | Ministry of physical planning, construction and state assets |

| Strategic planning/development | Regional development act (OG 147/14, 123/17, 118/18) | Ministry of regional development and EU funds |

| The act on the system of strategic planning and development of the Republic of Croatia (OG 123/17) | ||

| Post-earthquake reconstruction | The act on reconstruction of buildings damaged by earthquakes in the area of the City of Zagreb, Krapina-Zagorje county andd Zagreb County (OG 102/20) | Ministry of physical planning, construction and state assets |

Source: own work.

The Physical Planning Act of the Republic of Croatia regulates the spatial planning system and it is the legal framework for the implementation of spatial planning as a multidisciplinary profession.[7] The integration of activities and the need for space into spatial plans is considered a common responsibility of various professions through direct or indirect participation. The spatial planning system is linked to territorial organisation, with the exception of areas whose boundaries are determined on the basis of natural, cultural, historical, and economic values. According to the Act, there are three main levels on which decisions are made for each level, i.e. efficiency, expertise, and enforcement.[8] On the regional/local level, the ministry oversees representative bodies, while governing bodies plan enforcement. The relationship between the spatial planning system and other administrative areas (sectors) is regulated by special laws making it more challenging to establish an effective vertical and horizontal cooperation.

Strategic planning in Croatia is mostly defined by two acts. In the Croatian territory, there are numerus developmental processes. To coherently manage these processes, the Regional Development Act was adopted in 2014.[9] Among other things, the Act regulates the domain of strategic development planning in urban agglomerations, and in larger or smaller urban areas. The Croatian population of around 4 million is mostly gathered in cities and four largest ones[10] have more than a quarter of the country’s total population. To stimulate the development of all parts of the country, laws and by-laws have been enacted, prescribing the development of strategic development documents for the purpose of implementing regional development policy. Lower-level strategic development documents thus became an important tool for development management at the regional and local levels, as well as the basis for identifying projects for funding from EU funds. The Act regulates the objectives and principles of regional development management of Croatia, regional development policy planning documents, bodies responsible for regional development management, the assessment of the level of development of local and regional self-government units, the manner of determining urban and assisted areas, encouraging the development of assisted areas, implementation, monitoring and reporting on the implementation of regional development policy to make the most efficient use of EU funds. It focuses on sustainable development by creating conditions that enable all parts of the country to foster competitiveness. The above-mentioned act introduced the concept of urban areas in Croatia and defined three new territorial categories: urban agglomerations, and larger and smaller urban areas. Therefore, the biggest urban centres are four urban agglomerations, while the larger urban areas are 10 cities with more than 35,000 inhabitants and are not included in urban agglomerations. Smaller urban areas are 19 other settlements that have more than 10,000 inhabitants or are administrative centres of their counties (2011). All urban areas may, with the prior consent of their representative bodies, include neighbouring self-government units with whom they form functional units.

The Act on the System of Strategic Planning and Development Management of the Republic of Croatia regulates the system of strategic planning of Croatia and the management of public policies, e.g. preparation, drafting, implementation, reporting, monitoring of implementation and effects, and evaluation of strategic planning acts for the formulation and implementation of public policies prepared, adopted, and implemented by public bodies. The system is based on the principles of accuracy and completeness, efficiency and effectiveness, responsibility and focus on results, sustainability, partnership, and transparency.[11] Strategic Planning and spatial planning systems in Croatia exist within two separate regulatory frames. Spatial planning is defined by the Physical Planning Act, while strategic planning is defined by the Act on the System of Strategic Planning and Development Management and the Regional Development Act. Despite different laws, strategic and spatial planning must be harmonised.[12] Although both systems have balanced and sustainable development stated as a goal, they remain defined by different regulatory and institutional frames. The problem of implementing urban renewal in Croatia is evident in the impossibility to implement complex city projects, which is partly a result of the nature of land-use planning system and its traditional limitations. In short, it does not express what it needs, but states what it does not want (Albrechts, 2002).

Other local administrative units in Croatia are not required to develop strategic development documents but they mostly follow the directives of Regional Development Act of the Republic of Croatia and the Act on the System of Strategic Planning and Development Management of the Republic of Croatia, and develop their own local strategic documents. The Ministry of Regional Development and EU Funds (MRDEUF) is responsible for implementing regional development policy, which means a comprehensive and coordinated set of goals, priorities, measures, and activities aimed at stimulating long-term economic growth and overall quality of life in accordance with the principles of sustainable long-term development to reduce regional disparities. The 2030 National Development Strategy (NDS) should steer the development of Croatia until 2030 and the purpose of the NDS is to set a clear long-term vision for the country providing a strategic guidance to all development policies and lower-ranking strategic planning documents. While documents with extensive visions had been produced in Croatia in the past, this is the first time that the government has decided to employ a comprehensive and evidence-based process using a participatory bottom-up approach. Additionally, the analytical underpinning prepared for the NDS has been used by MRDEUF in the programming of the 2021–2027 European Union period.

Furthermore, a territorial approach to development is aimed at increasing the competitiveness of the economy. Strategic development documents are an opportunity to direct the development of a particular environment through the implementation of activities, programs, and projects, and to create positive long-term socio-economic effects in an area. As in foreign examples (some of which are mentioned in this paper), strategic documents contain an analysis, identify development directions (goals, priorities), and define the measures and activities that will be implemented to achieve the set goals. There is a link between planned activities (projects) and local, regional, national, or EU funding. Few documents have been developed since the adoption of the new Act and in most cases, strategies are still just a “wish list”, as they are not clearly linked to budget planning. Croatia is still far from a developed system of strategic planning that ensures strong cross-sectoral coherence of strategic goals and priorities, monitors the achievement of goals, and has mechanisms for taking corrective actions (when deviations are identified) or reformulating goals (when required) (Bajo and Puljiz, 2017). The law on strategic planning seeks to strengthen strategic planning and management of public policies through a harmonised system of planning and preparation, development, implementation, and monitoring and evaluation of implementation success. This is still not the case. Numerous strategic planning documents are still divided into several categories.[13] There are three kinds of documents: long-term, mid-term and short-term, divided further into development plans and implementation programs. Likewise, it is important to note that the quality of strategic planning at the local and regional levels is dependent on a large number of local and regional self-government units mainly lacking human resources or development potential for serious strategic planning.

The strengthening of the mechanisms for the territorial coordination of intervention and management in functional areas in the current perspective manifests itself in the establishment of a new EU tool of the cohesion policy such as Integrated Territorial Investments (ITIs) under the Common Strategic Network. ITI implementation was optional and those who are doing so are implementing it differently. In fact, it is an integrated strategic approach addressing economic, environmental, social, climate, and demographic challenges in urban areas that considers the needs and simultaneously promotes urban-rural links by improving cooperation between cities and their surroundings, creating partnerships between different stakeholders, and reducing disparities within urban areas. Thus, a key feature of the ITI mechanism is parallel emphasis on sectors and territorial integrity (Katurić et al., 2016).

The Regional Development Act prescribed the obligation to prepare county development strategies and also urban area development strategies as a prerequisite for using ITI funds to strengthen the role of cities as drivers of economic development and to promote territorial governance – a place-based approach, partnership, and participatory planning. The new approach to territorial development in Croatia is implemented as part of the use of the ITI in seven largest cities with the capacity and needs to implement projects under this mechanism – Zagreb, Split, Rijeka, Osijek, Zadar, Slavonski Brod, and Pula. The cities have formed urban agglomerations or urban areas with their surroundings on the basis of functional connections, and the main goal was to facilitate the implementation of territorial development strategies. The support for these areas is to be programmed by an integrated, inter-sectoral territorial strategy – the ITI (Urban agglomeration/area) Strategy. It is comprehensive and enables the execution of territory-based integrated projects to solve complex development problems, as well as to more efficiently exploit the specific potential of the urban areas.[14] To summarise, the process of preparation for the ITI implementation included:

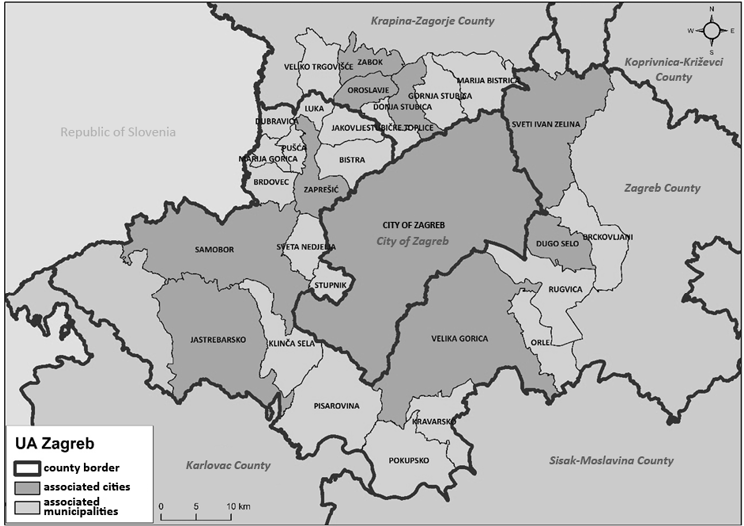

To define the coverage of an urban agglomeration, mandatory criteria were prescribed based on the share of at least 30% of employed daily migrants who migrate to the central city of the urban area/agglomeration, which is in line with the criteria used by European Statistical Office (EUROSTAT). Additional criteria included shared development resources (natural or infrastructural) and the existence of mutual, specific development problems and needs. The need for spatial continuity was also noted as a special criterion, but other factors (such as political) resulted in some spatial inconsistencies (e.g. Rijeka, Pula) of the urban areas. The boundaries of the urban agglomeration have been defined on the basis of the administrative boundaries of local self-government units (cities and municipalities) that are part of urban agglomerations. There are many differences in urban agglomerations and urban areas in Croatia. We will briefly compare Zagreb and Zadar urban areas to showcase some of them.

Fig. 2. Zagreb Urban Agglomeration

Source: own work.

The Zagreb Urban Agglomeration, along with the City of Zagreb as the centre of the agglomeration, includes 29 local self-government units, 10 cities and 19 municipalities in three counties.[15] The average population density is over 370 inhabitants / km², which indicates a high concentration of people and goods.

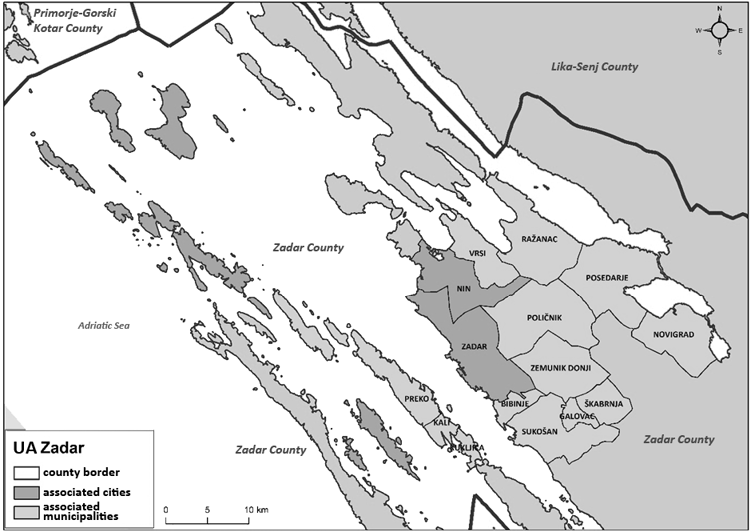

Fig. 3. Zadar Urban Area

Source: own work.

The City of Zadar is the largest Croatian city with more than 35,000 inhabitants. The Zadar Urban Area includes two cities and 13 other municipalities in the Zadar county.[16] Average population density is 143.1 inhabitants/sq. km, which is almost twice as many as the Croatian average. That corresponds to a usually higher density in urban areas relative to the overall territorial average.

Moreover, the Partnership Council is a very important body in strategic planning and preparation process in ITI. Both Zagreb and Zadar (as well as others) established partnership councils as an advisory bodies that participate in all phases of preparation and implementation of the development strategy. Every local unit within an agglomeration scope has its representative in the Partnership Council, which follows the need for equal representation of key stakeholders from the public, private, and civil sectors. Likewise, some urban areas have established coordination councils of mayors and deputy mayors.

The strategies were made using the Guidelines issued by the Ministry of Regional Development and EU Funds. Databases have been formed and tracked, macro sectors extensively analysed, and development problems and potentials formulated. In addition, a long-term vision has been defined, as well as a strategic framework consisting of goals, priorities, and measures. There were numerous regional disparities in the contents of the strategies, but as specific objectives for EU financing were predefined, all strategies were steered in a similar direction that could be considered as an interference in independent strategic planning. When one compares the strategies, one will find that there are certain similarities in the priorities identified as key enablers of urban area development: (a) improving conditions for further economic development through a focus on high added-value branches, (b) improving the urban mobility system within the urban area/agglomeration, and (c) sustainable spatial development through revitalisation and restoration of brownfield areas (Table 2).

| Zagreb Urban agglomeration | Zadar Urban area |

|---|---|

| Improving the quality of life, public and social infrastructure, and human resources | Development of human resources and high quality of social facilities and services |

| Development of the competitive and sustainable economy | Competitive economy based on active cross-sectoral integration |

| Improving environmental, nature and space management | Sustainable management of spatial resources with improved quality of urban environment |

Source: The City of Zagreb, 2017; The City of Zadar, 2016.

Urban agglomeration and urban area strategies are joint development documents based on partnership and participation of all relevant stakeholders within the territorial scope. As a prerequisite for using the ITI mechanism they were initially established using the prescribed and sometimes excessively complex methodology. This was especially visible in case of the Zagreb Urban Agglomeration, since the regulatory framework did not entirely recognise the special status of the City of Zagreb as the capital, city and county. Complex three-level coordination proved to be a challenge itself. The experiences from the first phase of ITI implementation are generally positive, and strengthening partnership and cooperation proved to be an asset in strategic planning and ITI implementation process. Partnership has strengthened between different sectors (private, public, academia, and non-governmental organisations), different self-government units, and the ministry and cities involved. The network that has been built through ITI implementation for the 2014–2020 period is a strong base for developing other initiatives, programs and projects not necessarily linked to this mechanism.

Furthermore, with the help of ITI, cities have gained the ability not only to rethink their territorial strategic planning directions, but also to directly decide how to use the funds within their urban areas. The organisational framework gave them a wider set of responsibilities, and some seized the opportunity more successfully than others. Urban areas were given ten specific objectives for project financing from the EU, which had an influence on development strategies and priorities. In the next programming period (2021–2027), these predefined financing opportunities should be defined in close cooperation with the urban areas to meet the actual needs of ITI cities, as an adequate response to their challenges and needs. According to current MRDEUF information there will be further expansion of the ITI mechanism to a total of 14 (or even more than 20) cities to strengthen development centres in Croatia and thus contribute to balanced regional development. However, the programming for the 2021–2027 period is still ongoing, and alternations are expected. Nevertheless, the strategies were comprehensive and beyond ten ITI defined financing objectives. But when it comes to the implementation phase, only ready projects with prepared documentation and clear ownership could have been financed through ITI, which resulted in highest implementation and allocation in centres of urban areas and a certain feeling of injustice from smaller municipalities included in the planning process and urban areas. Also, some could ask whether projects were truly ‘integrated’ or ‘territorial’.

Regarding practical experiences, it is clear that the process of the implementation of the ITI mechanism in Croatia in the 2014–2020 period could be characterised as long-lasting. The main reason for this was the delay in the preparation of the ITI structure, which partly affected the later start of the absorption of ITI funds from the ESF. In mid-2021 Croatia is still in the programming phase and it remains unclear whether the described process of new territorial governance units will be continued in the 2021–2027 period. It has still not been confirmed how many urban areas will be included in ITI, how the urban agglomerations and areas will be defined or what the development strategies will look like. All this is to conclude that some lessons are still to be learned.

One of the key goals of the ITI mechanism was the strengthening of the cooperation of self- government units within the urban agglomeration scope. A new form of coordination, participation and partnership has been established, and this is the first visible impact of the ITI implementation. The impact has a long-term potential, and the first phase will be expanded with new urban agglomerations. In the 2021–2027 period larger allocations are expected for urban development. This is an opportunity for connection between cities as possible beneficiaries so they can use it for best practice insights, exchange of ideas, and policy development. More efficient implementation of integrated projects has been the second impact of the ITI implementation. Having their own administrative units responsible for ITI implementation, cities had an opportunity to create calls for specific projects that responded comprehensively to the needs and problems of their urban areas. This contributed to stimulating competitiveness and also to a better use of their resources since projects need to be co-financed from local budgets. ITI is an important tool in the decentralisation of planning but also in the implementing phase of the territorial development.

Finally, the process showed the essential need for further building of administrative capacity for strategic planning and project preparation. It is important to enhance the internal capacities of all stakeholders involved in strategic planning and implementation so they can in the best possible way contribute to developing strategic goals. Strategic planning is a long term and flexible process, and therefore it is crucial to invest in local capacities so they can be the creators of their progress and development.

ALBRECHTS, L. (2001), ‘How to proceed from image and discourse to action: As applied to the Flemish Diamond’, Urban Studies, 38 (4), pp. 733–745. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980120035312

ALBRECHTS, L. (2002), ‘Strategic (spatial) planning re-examined’, [in:] VAN DEN BROECK, J., BRYSON, J. B. and ROERING, W. D. (1988), ‘Initiation of Strategic Planning by Governments’, Public Administration Review, 48 (6), pp. 995–1004. https://doi.org/10.2307/976996

ALBRECHTS, L. (2004), ‘Strategic planning reexamined’, Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 31 (5), pp. 743–758. https://doi.org/10.1068/b3065

BAJO, A. and PULJIZ, J. (2017), ‘Institucionalna potpora za strateško planiranje i gospodarski razvoj Republike Hrvatske’, Osvrti Instituta za javne financije, 93, pp. 1–4. https://doi.org/10.3326/ao.2017.93

CHAPIN, Jr., F. S. (1965), ‘Urban Land Use Planning’, American Journal of Sociology, 71 (1), pp. 116–117. https://doi.org/10.1086/224017

COMPENDIUM OF SPATIAL PLANNING POLICIES AND SYSTEMS IN THE EUROPEAN UNION, European Commission, Brussels, 1997.

CULLINGWORTH, J. B. (1972), Town and country planning in Britain: the changing scene, London: Allen and Unwin.

DAVOUDI, S., EVANS, E., GOVERNA, F. and SANTANGELO, M. (2008), ‘Territorial Governance in the Making, Approaches, Methodologies, Practices’, Boletin de la A.G.E.N., 46, pp. 33–52.

ESPON Project 2.3.2 (2006), Governance of territorial and urban policies from EU to local level, Final report – part 1, Valencia: ESPON.

FALUDI, A. and KORTHALS, A. W. (1994), ‘Evaluating communicative planning: A revised design for performance research’, European Planning Studies, 2 (4), pp. 403–418. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654319408720278

FALUDI, A. and VAN DER VALK, A. (1994), Rule and Order Dutch Planning Doctrine in the Twentieth Century, The GeoJournal Library, Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-2927-7

GEPPERT, A. (2021), ‘Spatial planning in the implementation of the territorial Agenda of the European Union 2030’, Keynote speech for the Conference Putting the Territorial Agenda 2030 into practice Local and regional pilot activities and their supporting framework conditions, Berlin, German Association for Housing, Urban & Spatial Development.

HEALEY, P. (1997), Collaborative Planning: Shaping Places in Fragmented Societies, Planning Environment Cities, London: Palgrave.

HEALEY, P. (2009), ‘In search of the ‘strategic’ in spatial strategy making’, Planning Theory & Practice, 10 (4), pp. 439–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649350903417191

KACZMAREK, T. and KOCIUBA, D. (2017), ‘Models of governance in the urban functional areas: Policy lessons from the implementation of integrated territorial investments (ITIs) in Poland’, Quaestiones Geographicae, 36 (4), pp. 47–64. https://doi.org/10.1515/quageo-2017-0035

KATURIĆ, I., TANDARIĆ, N. and SIMOV, S. (2016), ‘Integrirana teritorijalna ulaganja kao instrument urbane obnove u Republici Hrvatskoj’, [in:] KORLAET, A. (ed.), Strategije urbane regeneracije, Zagreb: Hrvatski zavod za prostorni razvoj.

MINTZBERG, H. (1994), ‘The fall and rise of strategic planning’, Harvard Business Review, 72 (1), pp. 107–114.

MINTZBERG, H., AHLSTRAND, B. and LAMPEL, J. (1998), Strategy safari: A guided tour through the wilds of strategic management, Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River.

NADIN, V. and STEAD, D. (2008), ‘European Spatial Planning Systems, Social Models and Learning’, DISP, 172 (1), pp. 35–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/02513625.2008.10557001

PAINTER, J. and GOODWIN, M. (1995), ‘Local governance and concrete research: investigating the uneven development of regulation’, Economy and Society, 24 (3), pp. 334–356. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085149500000014

PERSSON, C. (2020), ‘Perform or conform? Looking for the strategic in municipal spatial planning in Sweden’, European Planning Studies, 28 (6), pp. 1183–1199. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1614150

PIERRE, J. (1999), ‘Models of urban governance: the institutional dimension of urban politics’, Urban Affairs Review, 34 (3), pp. 372–396. https://doi.org/10.1177/10780879922183988

POISTER, T. H. and STREIB, G. (1999), ‘Performance Measurement in Municipal Government: Assessing the State of the Practice’, Public Administration Review, 59 (4), pp. 325–335. https://doi.org/10.2307/3110115

TANDARIĆ, N., WATKINS, Ch. and IVES, Ch. D. (2019), ‘Urbano planiranje u Hrvatskoj tijekom socijalističkog režima/ Urban planning in socialist Croatia’, Hrvatski geografski glasnik, 81 (2), 5–41. https://doi.org/10.21861/HGG.2019.81.02.01

TASAN-KOK, T., VAN DEN HURK, M., ÖZOGUL, S. and BITTENCOURT, S. (2019), ‘Changing public accountability mechanisms in the governance of Dutch urban regeneration’, European Planning Studies, 27 (6), pp. 1107–1128. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1598017

THE ACT ON THE SYSTEM OF STRATEGIC PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT MANAGEMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF CROATIA, Official Gazette, 123/17.

THE PHYSICAL PLANNING ACT OF REPUBLIC OF CROATIA, Official Gazette 153/13, 65/17, 114/18, 39/19, 98/19.

THE REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT ACT OF THE REPUBLIC OF CROATIA, Official Gazette 147/14, 123/17, 118/18.