Abstract. After gaining independence, countries such as Slovenia put a lot of effort into adapting their legislations to new market conditions. While concentrating on legislation, they often dismissed several other factors which influence policy and decision making. Among them, a particularly important role is played by the Europeanisation of planning, and the turn towards a higher flexibility of processes and land uses as opposed to the predetermination via zoning. While shedding light on these issues, this paper reflects on the incremental evolution of the Slovenian spatial planning system from the approval of the first Spatial Planning Act in 2003 towards a territorial governance approach characterised by a mix of regulatory processes and plans.

Key words: spatial planning system, planning law, Europeanisation, Slovenia, territorial governance.

In the European spatial planning community Slovenia is usually considered a “country from the Eastern block” (Maier, 2012). The country gained independence in 1991, and the ministry responsible for spatial planning focused on planning legislation as the core transformation tool of the planning system. In 1991, the existing planning legislation (originally dating back to 1984) was adapted to the then new political and market conditions, and in 2003 the first new Spatial Planning Act (ZUreP-1, slo. Zakon o urejanju prostora) was adopted. In 2007 another law, the so-called ZPNačrt (slo. Zakon o prostorskem načrtovanju) followed, and in 2017 yet another one (ZUreP-2, slo. Zakon o urejanju prostora 2). Altogether, in the 30 years of Slovenia’s independence, the framework of the country’s spatial planning system changed four times. From socially oriented spatial planning to strategic planning; from strategic to zoning, and in the latest change to a hybrid model. In the last ESPON project on territorial governance in Europe, the Slovenian system was similar to those of German-speaking countries, Mediterranean (Greece and Italy), Baltic and Eastern European countries (Czech Republic, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Slovakia), categorised as following the logic of “market-led neo-performative system” (Berisha et al., 2021). More precisely meaning that land use rights are established by general municipal plans, but the binding plans that assign spatial development rights are specific for small areas thus verified on a case basis.

According to planning discourses in Slovenia, there is a general agreement among professionals and in the academia as to the type of spatial planning the state should enable and support. On the one hand, policymakers (depending on the prevailing political option) and the private sector argue that a good and functioning spatial planning system supports and fast-tracks investment. On the other, planning professionals aim for more strategic-oriented, evidence-supported planning in the direction of collaborative and integrative planning (Pogačnik, 2005; Gajšek, 2018). What both sides agree on is the presumption that the change of legislation will result in these aspirational changes of the planning system – through the altering of planning practice and documents. Nevertheless, Buitelaar et al. (2011, p. 928) questioned this approach noting that “planning laws are usually made with good intentions but do not always lead to good results – at least not when measured against their own goals.” Why is this the case? Specialists in the theory of sociology of law, such as Weber (1964), Luhmann (2008) have argued that laws should reflect the needs of society to be legitimate and effective. This contention has been confirmed by several authors in spatial planning field (McAuslan, 1980; Black, 2002; Needham, 2007; Baldwin and Black, 2008; Van Dijk and Beunen, 2009).

In addition to changes in planning law, another factor should be considered relevant to the shaping and transformation of the Slovenian planning system in last 10 years – Europeanisation. The term was first mentioned by Ladrech in 1994, who described the impact of the EU on internal political discourses in France. Nowadays, there are different interpretations of the term: some understand it as the development of different governance structures at the EU level (Boerzel and Risse, 2007), whereas others suggest that it represents the process of dispersion and the institutionalisation of rules, processes, political paradigms, and common values. More to that, it names the process when regulation, first adopted in the EU, is then transmitted to Member States (Gualini, 2003). In the planning sphere many authors have addressed this issue (Cotella and Janin Rivolin, 2011; Luukkonen, 2011; Faludi, 2014); with some being country specific and discussing EU influence on national planning systems (Duehr and Nadin, 2007; Ragmaa and Stead, 2014; Tulumello et al., 2020). Although planning is left to Member States to govern independently, the EU prepares some guidelines via strategic documents such as the Territorial Agenda 2030 (Informal meeting of ministers, 2020), and also provides financial support, which indirectly acts as an important tool for exchange of knowledge, learning, and, consequently, soft changes of the system as well (Purkarthofer, 2016).

In Slovenia, Europeanisation of spatial planning has been first addressed by Peterlin and Kreitmayer McKenzie in 2007, and lately by Marot in 2018, who elaborated on the EU’s impact on the planning system, planning terminology, and education. Apart from spatial planning, authors have addressed various other topics: influence of the EU on states and policy making (Mansfeldova, 2011; Geddes et al., 2013; Fink-Hafner et al., 2015; Komar and Novak, 2020), economy (Fenko and Lovec, 2015), foreign policy (Kajnč, 2011), education system (Fink-Hafner and Deželan, 2014; Klemencic, 2015; Mikulec, 2019), and more directly connected to planning, by focusing on Natura 2000, as one of the most evident impacts of EU legislation on Slovenian territory (Marot et al., 2013; Šobot and Lukšič, 2020).

Based on this, this article discusses the role of Europeanisation in the process of transforming the spatial planning system against the traditional conviction that a planning law is in the heart of the matter. By dint of its short independence path, Slovenia can serve as a good example to elaborate on the subject. The results section is divided into three parts: in the first, the evolution of Slovenian planning law is described for the whole period of 20 years. In the second, the emphasis is given to the 2000−2010 period and its evaluation with the help of Regulatory Impact Assessment, while in the third pard, it is shown how Europeanisation has influenced the shaping of Slovenia’s planning system since 2010. Finally, the discussion reflects on how the role of the planning law in the transformation of the planning system has lately become of lesser importance in comparison to other factors, such as Europeanisation, and what the stakeholders have or have not learnt from this.

The evolution of Slovenian spatial planning is described based on the regulatory impact assessment performed in 2010 (Marot, 2010, 2011) for the 2000−2010 period, and several studies (indirectly) related to the evaluation of the planning system for the period from 2010 to 2020. The results of the studies are for both periods reported for four major topics: understanding the legislation, institutional setting, legitimacy and public participation, and new paradigms. These topics resonate with how the role of planning law is shaping the planning system and how this corresponds to the assessment elements defined in the regulatory impact assessment from 2010.

The data for 2010 was collected using a survey conducted with municipalities (55 out of 210 participated), 11 interviews with planning professionals, and participation of the articles’ author in the planning process, and planning-related events. The data from the questionnaires, interviews and legislation analysis apply to both the 2003 and 2007 laws; some components of the 2003 law remained valid until 2017. The questionnaire consisted of 29 questions regarding the comprehension of the law, administrative planning capacities of municipalities, relationships and co-operation between actors at different administrative levels, the openness of the planning process, the implementation of the planning development goals, and so on. Participating municipalities covered 34% of Slovenia’s surface and 44% of its population as of 30 June 2009. These municipalities need to follow and implement the duties set in the planning law regardless of their area or population, or their individual administrative capacity. The tasks of interviewees included running the process of municipal spatial plan preparation, preparation of development plans, detailed site plans, spatial development conditions, etc.

The interviews were conducted in person in 11 planning companies, geographically distributed around Slovenia, in December 2009 and January 2010. Individual interviews consisted of 21 open questions dedicated to the state of the planning system, approaches to and experiences of the planning process, co-operation levels and the quality of the same between planning system actors, the understanding of the planning law, and an overall evaluation of the planning legislation and planning system. On average the interviewees had 17 years of planning-related experience and had, therefore, operated under the jurisdiction of all three pieces of legislation that had come into force since 1984.

The evaluation of the situation in 2020 was executed based on several studies by the author about Slovenian planning communities such as the Evaluation of the implementation of the Spatial Development Strategy of the Republic of Slovenia (Golobič et al., 2014), research on terminology of new planning paradigms (Marot, 2014), and the preparation of the last report on spatial development in Slovenia (not yet published). Unfortunately, the same comprehensive regulatory impact assessment as in 2010 has not been conducted as it has not yet been acquired by the ministry.

The law initiated in 2003 (Spatial Planning Act, 2003) introduced three administrative levels of planning, and two types of planning documents: strategic and implementation documents (see Table 1). All municipalities were required to adapt new municipal spatial plans. The state should have prepared the national spatial development strategy (released in 2004) and develop detailed plans in case of state infrastructure projects. In an innovative way, the law foresaw the intermediate planning level, by introducing the regional concept of spatial development as a connecting link. This assumed two forms. First, horizontally, between municipalities (the administrative reform after 1991 resulted in an increase in the number of municipalities from 64 to eventually 212), and then vertically, between national and local levels of governance. Although the intention of the act/policy makers was to focus on strategic planning, the success was only partial since no such concept was adopted (three were prepared in a draft version). The Spatial Development Strategy of Slovenia (Ministry of the Environment and Spatial Planning, 2004), which was derived from the 2003 act, was one of the few constants of the Slovene planning system, and it established the national spatial development objectives and priorities that were still in place in 2020.

| Level | Main aim | 2003 (ZUreP) | 2007 (ZPNačrt) | 2017 (ZUreP-2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| National | Strategic |

The Spatial Development Strategy of Slovenia Spatial Order of Slovenia |

National Strategic Spatial Plan |

The Spatial Development Strategy of Slovenia Action programme for delivery of the strategy (Spatial Order of Slovenia) |

| Detailed | National detailed site plan | National spatial plan |

National spatial plan National detailed site plan |

|

| Regional | Strategic | Regional conception of the spatial development | – | Regional spatial plan |

| Detailed | Intermunicipal detailed site plan | – | – | |

| Local | Strategic | Strategy of the Spatial Development of the municipality |

Municipal strategic spatial plan Intermunicipal spatial plan |

Municipal spatial plan (strategic) |

| Detailed |

Municipal Spatial Order Municipal detailed site plan |

Municipal spatial plan Municipal detailed site plan |

Municipal spatial plan (detailed) Municipal detailed site plan |

Source: own work.

Any attempts to rely on the strategic aspects of planning were diminished only four years later when, because of the change of the government, a new planning law was enacted. As the legislator argued at the time, the main reason for adopting this law was to accelerate the planning process and enable faster issuing of building permits. The new law (ZPNačrt, 2007) abolished the regional level of planning, and instead a rational of decision making (e.g. security of the potential investor) was seen as the one and only important principle of the planning system. Thus, the result of the planning process should be land use plans which would inform investors under what conditions land could be developed. Accordingly, the names of the plans were changed and the powers in the planning system were shuffled – the state gained more responsibility for overseeing what municipalities and other sectors were doing.

The Spatial Planning Act 2017 resembled the law from 2003; planning was once again envisioned as a three-level activity with regional spatial plans acting as strategic intermediaries between national and local levels. At the national level, two instruments were introduced with the purpose of easing the planning process, and at the local level more emphasis was placed on detailed plans and land use zoning. By now 182 out of 212 local communities have adopted municipal spatial plans. However, this has been done in the period of the last 20 years and under different spatial planning acts’ jurisdiction, which means these plans are of various names (and types) and content structure. A major novelty of the 2017 Act was that it required better horizontal co-operation at the national level (two new organisational arrangements to be put in place) and the establishment of a centralised spatial information system, which would be a basis for monitoring spatial development.

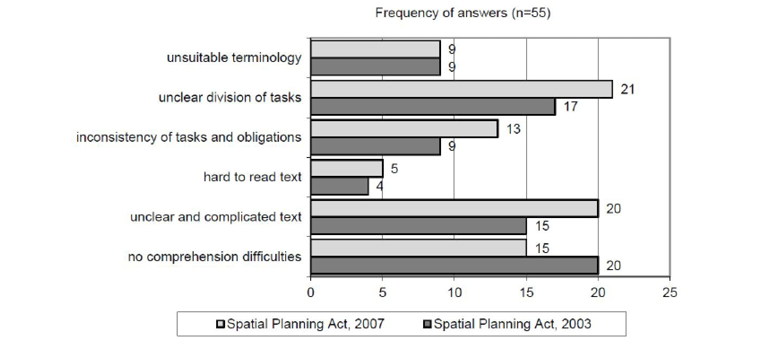

In the first step of the assessment, I was interested as to whether planning stakeholders understood the substance of the law and what action they undertook accordingly. Comparison of the texts of the 2003 and 2007 laws focused on issues of terminology and highlighted certain differences between the documents. The lists of professional terms were the same for fewer than half of the items (12 out of 25 terms), and the definitions for the rest of the terms differed, thereby adding to confusion as to how terminology was used in the field. Only a few of the respondents had not encountered problems with comprehensibility related to interpreting the laws. Around 36% of the respondents were familiar with the contents of the 2003 legislation, whereas less than a third (27%) were familiar with the contents of the 2007 legislation. The difficulties experienced by the respondents are illustrated in Fig. 1. The identified problems included: an unclear division of tasks amongst actors (ministries, municipalities, etc.) in the planning system, and ambiguous and complicated legislative text. Confusion was also reported to had already existed with regards to basic terminology, e.g., with the words used to name plans (two possible options), defining the phenomenon of dispersed settlements, and the functional lot of a building, a construction lot, and other facilities. The survey participants revealed that they had been coping with the problems by consulting the ministry responsible for spatial planning, namely the Ministry of the Environment and Spatial Planning, neighbouring municipalities, and planning companies.

Fig. 1. Difficulties in comprehending the law, as reported by the survey participants (Marot, 2010)

Source: own work.

In theory, if a legislator considers existing administrative structure and its capacity, no major obstacles should emerge during the implementation of the spatial planning law. Furthermore, the implementation of legislation is a feasible exercise. The 2003 Planning Act evenly distributed planning responsibilities across national, regional, and local levels, but from 2007 onwards, the majority of obligations have been centralised in the Ministry of Environment and Spatial Planning. The Ministry and sectoral bodies have assumed control with regards to determining draft municipal plans and have strongly interfered with the final contents of such plans.

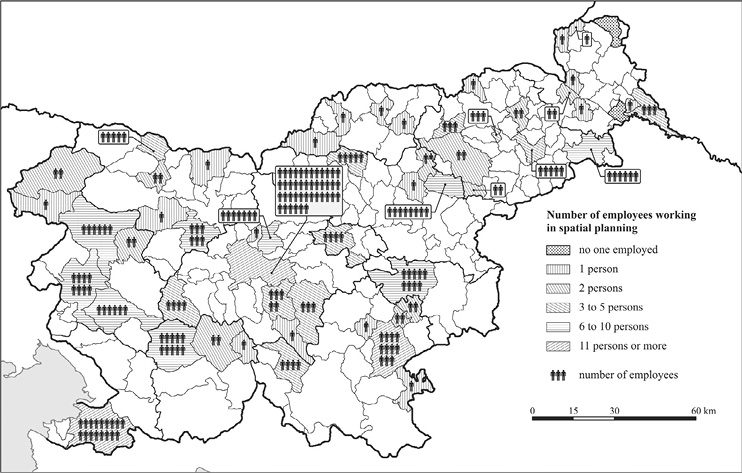

Research has shown that assorted municipalities (whether viewed individually or collectively) have insufficient human resources to conduct the responsibilities demanded of them (Fig. 2). Previous planning legislation mandated, for the first time ever, the employment of a municipal planner in every municipality, but this measure was not fully enforced. Municipalities also varied significantly in terms of their administrative arrangements for their planning departments. Some of them had individual planning departments, others only employed one person who covered public utilities and infrastructure, whilst others still hired external contractors to serve as urban planners.

Due to the restrictions introduced by the public employees’ law, which was formulated in response to the 2008 economic crisis, municipalities were prohibited from appointing new employees who could have confidently tackled the new challenges (e.g. climate change or mobility) that arose from spatial management. Alternatively, municipalities could act upon the low governance capacity accordingly to the Local Self-Government Act (2007) and establish joint administrations for planning. In 2010 only a few municipalities did this, which was understandable as this ‘solution’ was suggested to the newest municipalities who had just fought for administrative independence from their neighbourhood municipalities; given this, they were in no mood to immediately thereafter co-operate with them.

Fig. 2. Capacity of Slovenian municipalities to carry out the planning legislation (Marot, 2010)

Source: own work.

Apart from the lack of planning employees, deficiencies in funding for planning activities, e.g. studies, etc., were another problem encountered by the municipalities. Whilst their financial resources have continued to decline over the last decade, this study’s interviewees suggested that the municipalities had been moderately successful in terms of how proactive they had been in gaining EU funding or attracting investors. Only 5 out of 55 municipalities which participated in the survey had actually participated in any EU projects before. Furthermore, the municipalities which already had been EU project partners were the ones with the status of a city municipality (only 11 such municipalities among 212). Even the information gathered for all the municipalities did not show any better performance – in the period 2005–2008 only 10 out of 210 were engaged in the INTERREG IIIB project (a project which exposed those involved to processes of transnational exchange of knowledge and planning practices).

Legitimacy indicates the values and norms present in a planning system, and especially the perception of the planning system by its actors. With regards to the legitimacy of the legislative system, the drafting of the 2007 Act was driven by the political will of the ministry responsible for planning. Practically no or very little support for the renewal of the planning law was solicited from planners and academics since they were still in the process of delivering what the 2004 law demanded. Stakeholders were excluded from the legislative process and were only invited to public hearings, during which few of their suggestions for improvements were considered. In accordance with Arnstein’s (1969) ladder, the public participation score that this process would gain would be (level) four out of eight, i.e., consultation. Furthermore, no feedback to stakeholder comments was provided, and overall, the consideration of public proposals was significantly low. As a result the associations derived from the survey for the planning legislation were either negative or neutral. The respondents mostly stated that the planning legislation was confusing and excessively complex, thereby preventing both understanding of and trust in the law.

| Neutral associations (21) | Negative associations (23) |

|---|---|

|

– Spatial Planning Act (8) – Municipal spatial plan (5) – Spatial plan, spatial act (3) – Planning (3) – Construction Act (2) – Detailed municipal plan (2) – Spatial planning framework (2) |

– Lengthy procedures of municipal plan, preparation and adoption (6) – Problems, difficulties (6) – Complexity of procedures, bureaucracy (6) – Constant changes in legislation (4) – Incapacity, organisational chaos of the government (2) – No monitoring |

Source: own work.

The transparency of the planning system has been deemed relevant because it enables the examination of the level of information exchange and deliberation in the planning process, as well as in process of the formulation of planning legislation. The planning process was more open following the 2003 legislation because it introduced the planning conference concept at the beginning of the plan preparation process. As a result, it gathered all interested parties and supported the process of (municipal) spatial plan preparation from initiation to completion. Since 2010 only basic provisions (e.g., public hearings and the public display of plans) have been implemented after a supplemented draft of the plan was made available. This accounted for approximately two-thirds of all procedural steps.

Overall, in 2010, the level of public participation in Slovenia was low and reached only the second stage – defined as consultation – of the five-level scale (from inform to empower) applied by the International Association for Public Participation. This was concluded based on information provided in the survey conducted among the municipalities. On the one hand, modern public communication techniques (e.g., an online interface of adopted municipal plans) were implemented; on the other, public hearings were traditionally announced in newspapers and billboards. Some planning companies have introduced alternative techniques for engaging local people, such as workshops, public lectures, and project councils. Most advanced municipalities have introduced a supervisory board, which comprises planning experts that support municipal councils and mayors in planning decisions.

In the survey from 2010 I was also interested in the extent to which to the municipalities had transferred the new planning paradigms into their strategic documents and thence into everyday practice. In 2010, sustainability and sustainable development were perceived as the main principles to be adapted by planning actors while making their decisions about strategic projects, planning interventions, and the likes. A comparison of the legislative texts (2003 and 2007) revealed similarities in the spatial planning objectives with regards to balancing development and conservation needs, controlling settlement, rational land use, and “sustainable development” goals. In addition, the 2007 law also emphasized the importance of renovation instead of building anew, the need for regeneration of degraded areas, and the importance of securing the public health of all citizens; which could also contribute to sustainability. At the time, only half of the municipalities brought forward the sustainability goal as important for their own spatial development, 14 of them mentioned quality of life, and 13 the rational use of the land as crucial spatial development objectives. The sustainable development principle was recognised as relevant, however, it was also noted that it could not be pursued in practice if the mayor was the one in charge of the planning decisions. Especially so, if the mayor usually put the investors’ wishes first.

The practitioners argued that although they saw the social appeal of the sustainability for the planning practice, the sustainable development objective was too general and strategic, and misused by the inhabitants, professionals, and politicians. According to them, these groups might use the term, though they did not really know the real meaning of it. As one interviewee stated: “You just write sustainable development as a goal (…) like they put on each product label it has no cholesterol in it”. In general, one could argue that the study showed that the principles were correctly integrated into the policy documents and plans, but that they were not put into practice.

In this section a reflection is provided on how Europeanisation has influenced the planning system and its elements over the last 10 years. This is achieved by discussing the progress that has been achieved upon the same thematic points raised and discussed in Section 4.

The last planning law was adopted in 2017, 10 years after the previous one. This is against the ‘rule of thumb’ which claims that 10 years is needed to fully implement planning legislation and make it operable in the planning system (Dekleva, 1999). With the 2017 law, the legislators aimed for comprehensiveness which resulted in a very long legal act of 303 articles in total, compared to the previous act which only had 113 articles. Furthermore, the legislature decided to redefine some of the basic terminology, and for some reason introduced two synonyms for two different types of municipal plans, namely Slovenian “občinski načrt” and “občinski plan”, thereby causing confusion. One step in the direction of solving the terminology and comprehension issues among the planning community was the publishing of the planning glossary in 2016 (Mihelič et al., 2015). In addition, in order to improve understanding of the legislation, the ministry responsible for planning frequently issues FAQ explanations as official interpretations of the law and professionals discussed open issues in meetings.

In comparison to the previous period, the planning departments of municipalities have not, according to observation, changed their human capacities much. However, what has transpired when compared to the previous human resources situation, is that many municipalities have established the so-called development offices. These offices have emerged having the task to prepare applications for EU funding, e.g. Interreg, Cohesion funds, etc., and at the same time participate in EU projects when a municipality acts as a project partner. Although this change might not be directly relevant to the planning process and the planning law, it indirectly creates an added value to planning. More precisely, such projects tend to broaden the horizons and knowledge of municipal administrators and workers, who would otherwise be trapped in their daily administrative routines. The projects offer an intermediator and support exchange of good practices, as well as enable benchmarking and networking for further co-operation.

In addition to “European offices,” many municipalities have now appointed a municipal urbanist (required by law), who can be either contracted as an external consultant or a permanently employed person. A second solution for the problem of low human capacity is the establishment of joint municipal administrative offices, an option already mentioned in the section 4.2. In 2020, there were 52 joint administrative office, 9 of which are also performing the tasks of territorial governance. In addition to the planning-oriented joint offices, three administrative units address environmental issues.

Compared to 2010, the participative dimension of planning has improved significantly. This is mostly not an outcome of the planning legislation (the obligations for public participation are more or less the same as in the previous law), but because of the practice brought by EU projects, e.g., INTERREG, and more knowledge being available to planning actors regarding the forms of participation. Although this does not apply much to the official planning process – the preparation of plans – it does apply to other planning initiatives, such as the preparation of development strategies. INTERREG projects have, in particular, initiated further engagement strategies with the general public and the relevant stakeholders. Participation activities include: assessment of the current situation in a local community/region, expression of the population’s needs, and providing feedback on strategic proposals or on good practices. These have brought planning closer to the public, almost to the extent to which the latter are overwhelmed by all the initiatives and invitations, and do not want to co-operate anymore.

The last 10 years have yielded good results in the implementation of new planning concepts. Resilience, smart cities, and circular economy have all entered the planning discourse in Slovenia. Most commonly this has happened through EU INTERREG (prevailing) and H2020 projects, which have addressed these concepts in both theoretical and practical ways.

In the case of the new planning concepts’ transposition, the disagreement among stakeholders also occurs because the planning society simply does not want to deal with yet another concept when they have not sufficiently implemented the previous one yet. For example, resilience was introduced as a response to climate change, although sustainability had not been fully enforced. For Slovenia in general, one can claim scepticism to such new concepts which was also confirmed in the study about resilience, done by Marot (2014). The survey showed that 10 of the 24 respondents believed that resilience was not a new concept, instead it was just a different interpretation of existing concepts such as sustainability or vulnerability.

The practical approach to the emerging new concepts is via project activities, which usually follow the logic of analysis, strategic thinking, and pilot actions. In such projects the spatial plans or other strategic development documents are screened to identify to what extent they already integrate the elements of a singular concept. For such exercises, Kajfež Bogataj et al. (2014) on climate change and adaptability, Marot et al. (2019) on green infrastructure, and Marot et al. (2020) on resilience of tourism sector to COVID-19, have shown that planning concepts are not integrated in the strategic documents and if they are, they are not followed by measures or incentives which would enable implementation.

The first discussion point of this paper is that Slovenians really believe in planning legislation and its power to steer institutional change. At the same time, however, practice offers no proof of this (Marot, 2010, 2020; Gajšek, 2019). In fact, they care so much about the legislation that they easily forget about other elements of the planning system which could contribute to a better planning practice. Activities intended to evolve better planning practice include the initiatives for building the administrative capacities in the municipalities, seminars about public participation techniques and/or acquiring of EU funds, etc. These measures are all related to the institutional framework, its soundness and performance efficiency, and are related to domestic matters (Cotella and Stead, 2011). The excessively frequent adoptions of completely new planning laws do not allow municipal planners to transfer the provisions of the laws into practice. As the survey by Marot (2010) has proven, they mostly just resent the law (and the legislators) and act in a “business as usual” manner; the result is that the legislature does not see its planning system transformation goals realised. As Table 3 shows this has not changed in between the periods.

| Elements of the planning system | 2000–2010 | 2010–2020 |

|---|---|---|

| Period with no significant impact of Europeanisation, mostly planning law influence | Period with a more significant influence of Europeanisation | |

| Understanding the legislation |

Problems with continuous changes of the law No coherence with the previous law |

Problems with continuous changes of the law Glossary on planning terminology published No coherence with the previous law |

|

Institutional setting |

Planning offices mostly understaffed Only a few joint municipal administrative offices Only few municipalities participate in EU projects Minor transnational knowledge exchange |

Establishment of several joint municipal administrative offices Establishment of municipal development offices in addition to existing planning offices to absorb EU fund Transfer of good practices (transnational exchange) |

| Legitimacy and public participation |

Modest public participation Moderately opened planning process |

Increase in use of participative techniques Openness of planning process increased |

| New paradigms |

A small number of paradigms: sustainable development, cohesion General approval about the sustainable development goal |

A plethora of paradigms: smart cities, green infrastructure, resilience, adaptability, cohesion, etc. Mostly disapprobation with the new paradigms, only slow transposition into the planning practice |

Source: own work.

In contrast, the soft approaches advanced by the EU have proven much more effective and can be seen, according to Duehr et al. (2007), as an instrumental influence of the EU. For example, the reorganisation of the municipal departments to apply for EU funds and the change in the practices of public engagement offers proof that a slow shift towards a more open and collaborative system of planning is occurring. Yet again, planning legislation cannot claim responsibility for this change. Various practices of public participation have been implemented by stakeholders at all administrative levels, and the public more or less enthusiastically shares its own ideas and needs in the development process. In addition, the relationship to civil society has changed; now it is seen as an equal stakeholder in the planning process. However, as the latest governmental moves have shown, the scale of engagement still largely depends on the current government and its view towards public opinion.

As for the transfer of paradigms and their integration into the planning process, the so-called discursive influence (Cotella, 2020), Slovenia is moderately perceptive. While researchers and the ministry’s representatives are on track following the ideological shifts and narratives outside of the country, local communities do not follow the discourse at the same speed. Previous research (Marot, 2014; Marot et al., 2019) has shown that the society is sceptical of the new concepts for several reasons: they more or less represent a recycling of existing concepts, and actors have no capacity to adjust to a new concept every five years.

To conclude, Slovenian spatial planning system is in a unique situation which is neither path-dependent nor Western-inflicted. The mixture of hesitancy towards system changes, contradicting expectations towards planning from opposing political parties (while they are in charge), and a traditional neglect of spatial planning as a relevant political topic have resulted in ad hoc and slow adjustments of the spatial planning system. After joining the EU, the changes of the system were accelerated by various incentives. These incentives have been both arbitrary – an obligation to transpose EU directives – and voluntary – through the implementation of EU Interreg projects and other transnational initiatives as argued by Peterlin and Kreitmayer Mckenzie (2007). These projects offer new knowledge, as well as the transnational exchange of spatial planning practices, instruments, and processes. As learnt from the Slovenian example, the transformation of the planning process is an on-going process, steered by many intentional and unintentional factors. As McLoughlin argued already in 1969, changes within the planning system, like a change of the planning law, take long to manifest themselves. Consequently it should not be approached in a hectic manner, e.g., by changing key legislation every seven years and naively expecting major changes to be carried effectively. A more conservative approach to legislative change is evident in, for example, Germany and the Netherlands which, in the last 30 years, have been considered to possess very rigid and persistent planning systems (see, i.a., Muenter and Reimer, 2020). In Slovenia, 30 years after gaining independence, it is evident that some positive changes have occurred, however, further work is still necessary. It can be deduced from the work of this study that a co-evolutionary, bottom-up planning is not consistent with the current stage of the development of planning in Slovenia. Yet the last legislation changes in 2017 indicate a more comprehensive role of spatial planning (regional planning level, less national sectors’ interference) which does not only assign land use to lots but govern the territory in an integrative manner within a more flexible planning system.

However, as a final concluding remark and to prove the title right, I would argue that one certainly needs to mention that in autumn 2021 the new planning legislation (ZUreP-1) has been already prepared by the current government and introduced into legislative procedure. In December 2021, this law was also officially adopted.

Acknowledgements. The research was financed by the Slovenian Research Agency: the junior researcher grant in the period 2006-2010 and the research programme P4-0009 Landscape as a living environment in 2021. Both are fully financially supported by the agency.

ARNSTEIN, S. R. (1969), ‘A Ladder of Citizen Participation’, Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35 (4), pp. 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225

BALDWIN, R. and BLACK, J. (2008), ‘Really Responsive Regulation’, The Modern Law Review, 71 (1), pp. 59–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2230.2008.00681.x

BERISHA, E., COTELLA, G., JANIN RIVOLIN, U. and SOLLY, A. (2021), ‘Spatial governance and planning systems in the public control of spatial development: a European typology’, European Planning Studies, 29 (1), pp. 181−200. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2020.1726295

BLACK, J. (2002), ‘Regulatory Conversations’, Journal of Law and Society, 29 (1), pp. 163–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6478.00215

BUITELAAR, E., GALLE, M. and SOREL, N. (2011), ‘Plan-led planning systems in development-led practices: An empirical analysis into the (lack of) institutionalization of planning law’, Environment and Planning A, 43 (4), pp. 928−941. https://doi.org/10.1068/a43400

COTELLA, G. (2020), ‘How Europe hits home? The impact of European Union policies on territorial governance and spatial planning’, Géocarrefour, 94 (3). https://doi.org/10.4000/geocarrefour.15648

COTELLA, G. and RIVOLIN, U. J. (2011), ‘Europeanization of spatial planning through discourse and practice in Italy’, disP - The Planning Review, 47 (186), pp. 42–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/02513625.2011.10557143

COTELLA, G. and STEAD, D. (2011), ‘Spatial planning and the influence of domestic actors: Some conclusions’, disP - The Planning Review, 47 (186), pp. 77–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/02513625.2011.10557146

DEKLEVA, J. (1999), ‘Instruments of spatial development regulation’, [in:] DROZG, V. (ed.), The key instruments of urban and spatial planning at the start of the new millennium: the state of art and the trend (SI: Ključni vzvodi urbanističnega in prostorskega planiranja na prelomu tisočletja: stanje in trendi). Book of abstracts. 15. Sedlarjevo srečanje, Maribor, 21.–23. Ljubljana, Town and Spatial Planning Association of Slovenia, pp. 27–38.

DÜHR, S. and NADIN, V. (2007), ‘Europeanization through transnational territorial cooperation? The case of INTERREG IIIB North-West Europe’, Planning, Practice & Research, 22 (3), pp. 373−394. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697450701666738

DUHR, S., STEAD, D. and ZONNEVELD, W. (eds.) (2007), ‘The Europeanization of Spatial Planning Through Territorial Cooperation’, Planning Practice & Research, 22 (3), pp. 291–471. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697450701688245

FALUDI, A. (2014), ‘EUropeanisation or Europeanisation of spatial planning?’ Planning Theory & Practice, 15 (2), pp. 155–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2014.902095

FENKO, A. B. and LOVEC, M. (2015), ‘From a Good to a Poor Student: The De-Europeanisation of Slovenian Foreign Policy in the Light of (European) Economic and Financial Crisis’, Études helléniques/Hellenic Studies, 23 (1), pp. 111–140.

FINK-HAFNER, D. and DEŽELAN, T. (2014), ‘The political science professional project in Slovenia: from communist monism, democratisation and Europeanisation to the financial crisis’, Društvena istraživanja, 23 (1), pp. 133–153. https://doi.org/10.5559/di.23.1.07

FINK-HAFNER, D., HAFNER-FINK, M. and NOVAK, M. (2015), ‘Europeanisation as a factor of national interest group political-cultural change: The case of interest groups in Slovenia’, East European Politics and Societies, 29 (1), pp. 287–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888325414535625

GAJŠEK, M. (2018), ‘Prostorsko planiranje med državnim intervencionizmom in prostim trgom. Spatial planning in-between state interventionism and the free market’, [in:] ZAVODNIK LAMOVŠEK, A. (ed.), Prostorski načrtovalci 21. stoletja: 60 let KPP, 45 let IPŠPUP. Ljubljana: UL FGG – Fakulteta za gradbeništvo in geodezijo Univerze v Ljubljani, pp. 39–45.

GEDDES, A., LEES, C. and TAYLOR, A. (2013), The European Union and South East Europe: the dynamics of Europeanization and multilevel governance, London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203112267

GOLOBIČ, M., MAROT, N., COF, A., BANTAN, M., HUDOKLIN, J. and HOČEVAR, I. (2014), SPRS2030 – Analysis of the implementation of the Strategy of the Spatial Development Strategy of Slovenia. Ljubljana, Biotehniška fakulteta, Novo Mesto: ACER.

GUALINI, E. (2003), ‘Challenges to multi-level governance: contradictions and conflicts in the Europeanization of Italian regional policy’, Journal of European Public Policy, 10 (4), 616–636. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350176032000101280

Informal meeting of Ministers responsible for Spatial Planning and Territorial Development and/or Territorial Cohesion (2020), Territorial Agenda 2030. https://www.territorialagenda.eu/files/agenda_theme/agenda_data/Territorial%20Agenda%20documents/TerritorialAgenda2030_201201.pdf [accessed on: 13.01.2021].

KAJFEŽ-BOGATAJ, L., ČREPINŠEK, Z., ZALAR, M., GOLOBIČ, M., MAROT, N. and LESTAN, K. A. (2014), Groundworks for the evaluation of the risks and opportunities climate changes bring to Slovenia: final report, Ljubljana: Biotechnical Faculty, University of Ljubljana, p. 149.

KAJNČ, S. (2011), ‘The europeanisation of Slovenian foreign policy: from accession to presidency of the council of the EU’, Teorija in Praksa, 48 (3), pp. 668−687.

KLEMENČIČ, M. (2013), ‘The effects of Europeanisation on institutional diversification in the Western Balkans’, The globalisation challenge for European Higher Education: Convergence and diversity, centres and peripherie, Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang, pp. 117–138.

KOMAR, O. and NOVAK, M. (2020), ‘Introduction: (De) democratisation in Slovenia and Montenegro: Comparing the Quality of Democracy’, Politics in Central Europe, 16 (3), pp. 569−592. https://doi.org/10.2478/pce-2020-0026

LADRECH, R. (1994), ‘Europeanization of domestic politics and institutions: The case of France’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 32, pp. 69–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.1994.tb00485.x

LOCAL SELF-GOVERNMENT ACT (2007), Official Gazette of the Republic of Slovenia, 94, pp. 12729–12746.

LUHMANN, N. (2008), Law as a social system, Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, p. 498.

LUUKKONEN, J. (2011), ‘Europeanization of spatial planning. Exploring the spatialities of European integration’, Nordia Geographical Publications, 40 (3), pp. 1–59.

MAIER, K. (2012), ‘Europeanization and changing planning in East-Central Europe: An Easterner’s view’, Planning Practice & Research, 27, pp. 137–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2012.661596

MANSFELDOVÁ, Z. (2011), ‘Central European parliaments over two decades–diminishing stability? Parliaments in Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovenia’, The Journal of Legislative Studies, 17 (2), pp. 128–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/13572334.2011.574023

MAROT, N. (2010), An Assessment of the role of spatial planning legislation in the Slovenian spatial planning system, Doctoral thesis. Ljubljana: University of Ljubljana, p. 312.

MAROT, N. (2011), ‘Upravljavska sposobnost slovenskih občin na področju prostorskega načrtovanja’, Acta geographica Slovenica, 50, (1), pp. 131−157. https://doi.org/10.3986/AGS50106

MAROT, N. (2014), Resilience: a word non-existing, yet sufficiently integrated into planning, Spa-ce.net conference, Bratislava.

MAROT, N. (2018), ‘Evropeizacija slovenskega prostorskega načrtovanja - deset let prizadevanj in izkušenj = Europeanisation of Slovenian spatial planning - ten years of efforts and experiences’, [in:] ZAVODNIK LAMOVŠEK, A. (ed.), Prostorski načrtovalci 21. stoletja: 60 let KPP, 45 let IPŠPUP. Ljubljana: UL FGG - Fakulteta za gradbeništvo in geodezijo Univerze v Ljubljani, pp. 46–53.

MAROT, N. (2021), ‘Slovenia: [Countries subject to the Mediterranean ICZM Protocol]’, [in:] ALTERMAN, R. and PELLACH, C. (eds.), Regulating coastal zones: international perspectives on land-management instruments, (Urban planning and environment), New York: Routledge, pp. 220–236. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429432699-11

MAROT, N., KLEPEJ, D., OGRAJENŠEK, I., PERVIZ, L., URŠIČ, M. and HORVAT, U. (2020), Urban tourism and COVID-19; Report of the activity 3.5, WP3, Ljubljana: University of Ljubljana; Maribor: University of Maribor, p. 54.

MAROT, N., KOLARIČ, Š. and GOLOBIČ, M. (2013), ‘Slovenia as the natural Park of Europe? Territorial impact assessment in the case of Natura 2000’, Acta geographica Slovenica, 53 (1), pp. 91–116. https://doi.org/10.3986/AGS53105

MAROT, N., PENKO SEIDL, N., KOSTANJŠEK, B. and HARFST, J. (2019), Study on the green infrastructure and ecological connectivity governance in the EUSALP area: Action group 7: To develop ecological connectivity in the whole EUSALP territory, Ljubljana: University of Ljubljana, Biotechnical Faculty, p. 87.

MCAUSLAN, P. (1980), The ideologies of planning law, Oxford: Pergamon Press, p. 282.

MIHELIČ, B., HUMAR, M., NIKŠIČ, M. et al. (2015), Urbanistični terminološki slovar, Ljubljana: Urbanistični inštitut Republike Slovenije, ZRC SAZU. https://doi.org/10.3986/978-961-254-943-5

MIKULEC, B. (2017), ‘Impact of the Europeanisation of education: Qualifications frameworks in Europe’, European Educational Research Journal, 16 (4), pp. 455–473. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904116673645

MINISTRY OF THE ENVIRONMENT AND SPATIAL PLANNING (2004), Strategy of the Spatial Development of the Republic of Slovenia, Ljubljana, Ministry of the Environment and Spatial Planning.

MÜNTER, A. and REIMER, M. (2020), ‘Planning Systems on the Move? Persistence and Change of the German Planning System’, Planning Practice & Research, pp. 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2020.1832362

NEEDHAM, B. (2007), ‘Final comment: Land-use planning and the law’, Planning Theory, 6 (2), pp. 183–189. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473095207077588

PETERLIN, M. and MCKENZIE, J. K. (2007), ‘The Europeanization of spatial planning in Slovenia’, Planning, Practice & Research, 22 (3), pp. 455–461. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697450701666811

POGAČNIK, A. (2005), ‘Prispevek k integraciji prostorskega, socialnega, gospodarskega in okoljskega načrtovanja’, Dela, 24, pp. 49–59. https://doi.org/10.4312/dela.24.49-59

PURKARTHOFER, E. (2016), ‘When soft planning and hard planning meet: Conceptualising the encounter of European, national and sub-national planning’, European Journal of Spatial Development, 61, pp. 1–20.

RAAGMAA, G. and STEAD, D. (2014), ‘Spatial Planning in the Baltic States: Impacts of European Policies’, European Planning Studies, 22 (4), pp. 671–679. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2013.772730

SPATIAL PLANNING ACT (2003), Official Gazette of the Republic of Slovenia, 110, pp. 13057–13083.

SPATIAL PLANNING ACT (2007), Official Gazette of the Republic of Slovenia, 33, pp. 4585–4602.

SPATIAL PLANNING ACT (2017), Official Gazette of the Republic of Slovenia, 61, pp. 8254–8310.

ŠOBOT, A. and LUKŠIČ, A. (2020), ‘Natura 2000 Experiences in Southeast Europe: Comparisons from Slovenia, Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina’, Journal of Comparative Politics, 13 (1), pp. 46–57.

TULUMELLO, S., COTELLA, G. and OTHENGRAFEN, F. (2020), ‘Spatial planning and territorial governance in Southern Europe between economic crisis and austerity policies’, International Planning Studies, 25 (1), pp. 72–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563475.2019.1701422

VAN DIJK, T. and BEUNEN, R. (2009), ‘Laws, people and land use: A sociological perspective on the relation between laws and land use’, European Planning Studies, 17 (12), pp. 1797–1815. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654310903322314

WEBER, M. (1964), Max Weber, the theory of social and economic organization, New York: Free Press, p. 436.