Abstract. Cultural and historical heritage is inextricably linked to territorial capital. Over the years, the recognition of its importance has increased in the political and policy discourse. This paper examines these challenges considering spatial planning policies and instruments, namely “how effective spatial planning instruments are in addressing the goal of protecting and enhancing cultural heritage.” The research is focused on two Western Balkan cases of Albania and Kosovo, and takes a comparative approach, considering the ever-present conflict between “the old and the new”, and between growth and preservation, in the respective capital cities of Tirana and Pristina. Both countries have gone through drastic transformations in their planning systems over the last two decades, with an attempt to shift from traditional rigid urbanism approaches towards more comprehensive and integrated ones. Additionally, the two countries are in similar stages of socio-economic development, which include a trend of concentration and rapid urban development. The findings suggest that while cultural preservation and valorisation is ranked high in terms of planning policies, both countries fail to preserve these values when it comes to land development practices.

Key words: territorial governance, spatial planning, cultural heritage, cultural preservation, urban identity.

Cultural and historical heritage is inextricably linked to territorial capital. Over the years, the recognition of its importance has increased in the political and policy discourse. SDGs, the UN Urban Agenda Habitat III, the ESDP, the EU Territorial Agendas (2010, 2020, and 2030), and the EU Urban Agenda are just a few examples of policies on cultural and historical heritage that have been incorporated into international, national, and local policy making and territorial governance. “The protection and enhancement of cultural and historical heritage” is a common objective in all these documents.

The attention put towards heritage conservation and management practices in the last 70 years has been also accompanied by a subtle evolution in interpretation and management of the changes in historic environments (Chen et al., 2020). Such changes are relevant because they emphasise the importance of the social and political context in influencing the local practices of cultural preservation. This paper examines these challenges considering spatial planning policies and instruments, namely: ‘how effective spatial planning instruments are in addressing the goal of protecting and enhancing cultural heritage.’ The research is focused on two Western Balkan cases of Albania and Kosovo, and takes a comparative approach, considering the ever-present conflict between “the old and the new”, and between growth and preservation, in the respective capital cities of Tirana and Pristina. Both countries have gone through drastic transformations in their planning systems over the last two decades, with an attempt to shift from traditional rigid urbanism approaches towards more comprehensive and integrated ones. Additionally, the two countries are in similar stages of socio-economic development, which include a trend of concentration and rapid urban development.

After an initial overview of the international framework that addresses cultural preservation, the research analyses the relationships between spatial planning and cultural heritage in Albania and Kosovo, from legal, institutional, and development perspectives. Next, the focus will shift to local policies and practices in the cities of Tirana and Pristina, with examples of urban transformation and their coherence with national and local spatial planning policies.

Spatial planning, as one of the main tools for achieving territorial governance, plays a key role in respect to the promotion of cultural and historical heritage. Apart from sectoral policies initiated by respective institutions of cultural heritage, it is through spatial planning that these policies are enacted in a territory and become part of the broader territorial development framework. Spatial planning plays an important role in harmonising and smoothing conflicting sectorial policies and their impacts. Hence, it plays a leading role in achieving development objectives for cultural and historic heritage (Dobricic et al., 2016). In the Western Balkans spatial planning is a highly heterogeneous activity, due to the ever-growing dependency on market economic mechanisms (Berisha et al., 2018). Therefore, it is worth exploring how spatial planning policies targeting cultural preservation are implemented in Western Balkan countries.

Indeed, not only in the Western Balkans but also globally urbanisation trends are growing, which results in increased pressure on cultural and historical heritage in urban areas (Al-Houdalieh and Sauders, 2009). Meanwhile, the growing numbers of tourists and urban visitors are on the one hand raising opportunities for preserving historic urban areas, but on the other the pressure encourages their re-appropriation and use for touristic purposes. This activity increases the economic income of urban areas through tourism while, subsequently, posing new challenges for maintaining cultural and historical heritage (Al-Houdalieh and Sauders, 2009).

An important focus of urban research since the 1980s has been the role of culture and cultural heritage in city development at the global level. In the 20th century, cultural heritage started to be perceived not only as an image, but a pure living evidence of the past lifestyle and knowledge (Nijkamp et al., 1998). This includes the way of living passed from generation to generation, the practices, artistic values and expression, objects, etc. Nevertheless, when discussing conservation strategies, the issue remains problematic. A debate whether the conservation should be active, museum-like or pragmatic persists (Angelidoua et al., 2017).

Under the current circumstances of globalisation, this problem is highlighted in developing countries, like Albania and Kosovo, which face the ambitious challenge of acquiring a competitive advantage in a world marked by globalisation. Gunay (2008) highlighted the idea that with the ascendancy of neoliberalism, cities have become incubators for many of the major political and ideological initiatives, through which city space has been increasingly reorganised by market-oriented economic growth and elite consuming behaviour. This means that cities rely more than ever on the built capital for growth, and to some extent this approach devalues cultural preservation actions. In this sense, it is important to regard the “cultural heritage sector” as a tool for economic development, and integrate it to spatial planning practices.

Spatial planning can contribute in different ways to the protection and promotion of cultural heritage. The discourse on the protection of cultural heritage through spatial planning plays an important role in increasing the level of knowledge and awareness of citizens. UNESCO guidelines highlight the importance of urban planning policies in this respect (UNESCO, 2019). Land-use policies support the protection of cultural heritage through restricting development in areas which are sensitive in terms of heritage (Guzman and Roders, 2014).

Nevertheless, financing cultural heritage projects is not always easy. While public and private investments in cultural heritage and cultural tourism can produce optimal economic returns (Nijkamp, 2012), the use of hybrid financing instruments is optimal for ensuring financial sustainability (Finpiemonte, 2021; Jelincic and Šveb, 2021). Therefore, Financial Instruments of Land Development (FILDs) can offer incentives for the protection, promotion, and rehabilitation of heritage areas.

Lastly, yet not least importantly, these areas can be further promoted through direct investment in rehabilitation projects. Nevertheless, in order to achieve this protection, coordination is necessary between different institutions and stakeholders. Considering the general transition that has occurred in spatial planning from a strictly land-use urban oriented planning towards forms of strategic spatial planning, visions have started to play an important role. A vision is important as it not only projects the future goals for the development of a given space and it supports and directs planning decisions, but also it creates a narrative for involving citizens and other stakeholders, following the idea of a shared European model of society, based on the inviolability of human rights (Faludi, 2007). Spatial Visions play an important role in planning decisions and they are enacted through land-use provisions and other planning instruments.

Hence, one hypothesis that can be developed is that while a city, a municipality, a region, or even a state for that matter, has a vision of sustainable future development, the protection of cultural and historical heritage is incorporated. Additionally, this means that the spatial vision of sustainable territorial development would be enacted in terms of land-uses and other instruments in order to enable the protection of cultural heritage. While from a normative viewpoint this may persist, in reality, conflicts between cultural heritage protection and new development are at the forefront of spatial planning debates. The immense pressures of urban development and the different stakeholder interests are of a growing concern for the future of cultural heritage.

Over the years, there has been a growing body of international documents and frameworks that support the integration of cultural and historical heritage in spatial planning. Some, such as SDGs and the UN Urban Agenda, operate at the global level, while others such as the ESDP, the Territorial Agenda, and the EU Urban Agenda operate at the European level. Albania and Kosovo have both committed in terms of implementing SDGs and the UN Urban Agenda. Additionally, both aim to join the EU and as such, many EU Spatial Documents have permeated into the spatial discourses. The below table offers an overview of the main goals, visions, and objectives of the above-mentioned documents.

| Documents | Vision / Goals and Objectives |

|---|---|

| SDG | SDG 11.4 Strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage |

| UN- New Urban Agenda | Safeguard and promote cultural infrastructures and sites, museums, indigenous cultures and languages, as well as traditional knowledge and the arts; develop vibrant, sustainable and inclusive urban economies, building on endogenous potential, competitive advantages, cultural heritage and local resources; promoting planned urban extension, while preserving cultural heritage; policies that safeguard a diverse range of tangible and intangible cultural heritage and landscapes, and will protect them from potential disruptive impacts of urban development. |

| ESDP | Development of integrated strategies for the protection of cultural heritage which is endangered or decaying, including the development of instruments for assessing risk factors and for managing critical situations; Maintenance and creative redesign of urban ensembles worthy of protection; Promotion of contemporary buildings with high architectural quality; Increasing awareness of the contribution of urban and spatial development policy to the cultural heritage of future generations |

| Territorial Agenda 2007 | Strengthening of ecological structures and cultural resources as the added value for development |

| Territorial Agenda 2020 | Wise management of natural and cultural assets |

| Territorial Agenda 2030 | Prosperity based on local assets, characteristics and traditions, cultural, social and human capital and innovation capacities; Natural and cultural heritage is a unique and diverse asset to be protected, managed and further developed; awareness on protection and utilization/re-utilization of cultural assets and other unique values, through instruments of Cohesion Policy. |

| Urban Agenda for EU | Ensure good governance through all aspects of urban development, including cultural issues; Urban regeneration, including social, economic, environmental, spatial and cultural aspects. |

Source: SDG (2015); ESDP (1999); UN-New Urban Agenda (2017); Territorial Agenda (2007); Territorial Agenda 2020 (2011); Territorial Agenda 2030- A future for all places (2021); The Urban Agenda for EU (2016).

As the above table shows, there is a global and European recognition of the role that spatial planning can play in protecting and enhancing cultural and historical heritage. While the cultural component is addressed in an unspecific way, it generally is quite prominent and covers a diverse range of meanings, from assets, to heritage, architectural and built environment, etc.

Spatial Planning Systems in Albania and Kosovo have undergone considerable changes over the years. In an attempt to take a more comprehensive and integrated approach to spatial planning, legal changes have been undertaken in both countries. In Kosovo, the foundations of a new planning system were established in 2004 with the approval of the “Spatial Planning Law”, subsequently changed in 2010. Meanwhile in Albania, the major legal changes in spatial planning occurred in the period 2006–2009, and culminated in 2009 with law 10119 “On territorial planning”. Although later, in 2014, there have been subsequent legal changes, these have not altered the wider framework and aim of territorial planning in Albania. Table 2 offers a comparison of the two countries:

| Variable | Albania | Kosovo |

|---|---|---|

| Law | Law 107/2014 “On Territorial Planning and Development” | Law No. 74- L174 “On Spatial Planning” |

| National Level Institutions | National Territorial Council | Parliament of Kosovo |

| Ministry of Infrastructure and Energy | Ministry of Environment and Planning | |

| National Territorial Planning Agency | Institute of Spatial Planning | |

| National Planning Instruments | General National Territorial Plan | National Spatial Plan of Kosovo |

| National Sectorial Plan | Zoning Map of Kosovo | |

| National Detailed Plan for Areas of National Importance | Spatial Plans for Areas of Special Importance | |

| Local Planning Institutions | Municipal Council | Municipal Council |

| Directory of Planning | Directory of Planning | |

| Local Planning Instruments | General Local Territorial Plan | Municipal Development Plan |

| Local Sectorial Plan | Municipal Zoning Map | |

| Detailed Local Plan | Detailed Regulatory Plans |

Source: own work (Allkja, 2019).

Based on the comparison one can see that there is a general similarity in terms of institutions and instruments for spatial planning. Both countries operate at the national and local levels, while regional planning is absent. At the national level in Albania, the highest-level institution is the National Territorial Council (NTC), a collegial entity, led by the prime minister, and composed of the ministers responsible for territorial policies, including the ministry responsible for cultural and historical heritage. This institution is responsible for approving the General National Plan of Albania, as well as approving the General Local Territorial Plans. Meanwhile in Kosovo, the highest-level institution is the Parliament of Kosovo, responsible not only for the approval of the legislation in planning, but also the Spatial Plan of Kosovo. Municipal Development and Zoning Maps are approved by the Ministry of Environment and Spatial Planning in Kosovo. This is one of the main differences between the two countries – while in Albania they are approved by the NTC, in Kosovo the approval is given by a ministry. Additionally, the National Territorial Planning Agency (NTPA) in Albania and the Institute of Spatial Planning in Kosovo play similar roles in terms of preparing national planning instruments and supporting horizontal and vertical coordination in planning processes (Allkja, 2019).

Respective ministries responsible for territorial/spatial planning lead the process for the preparation of the national planning instruments. These plans are prepared as a joint effort by all ministries and are coordinated by the NTPA and the Institute of Spatial Planning. Institutions at the national level have the competences to establish areas of national importance, including those related to cultural and historical heritage. In Albania this process is done within the General National Territorial Plan (GNTP), while in Kosovo through the Kosovo Zoning Map. Meanwhile, at the local level, the process is similar in both countries, with the only difference being the approval of the plan as mentioned above. The General Local Territorial Plan in Albania is composed of three main documents: the Territorial Development Strategy, the Land-use Plan, and the Territorial Regulation. Meanwhile, in Kosovo, the Development Plan and the Zoning Plan are two separate instruments. These instruments have a broad spectrum of territorial policies and also include issues related to the cultural and historical sectors. Lastly, detailed local plans are quite similar in both countries. The main difference, however, is that Albanian legislation has also incorporated Financial Instruments of Land Development while in Kosovo these instruments are not present. FILDs are important instruments in achieving planning objectives at the local level, including those of preserving cultural and historical heritage. Such instruments, including Betterment Fees, Transfer of Development Rights, Intensity Bonus, etc. may provide a good opportunity for capturing added land value, to allocate it to the local ambitions for preserving cultural heritage (Allkja, 2019).

Both countries have approved their Spatial Planning Instrument at the national level. The table below offers an overview of their visions, strategic objectives, and policies regarding cultural heritage:

| Local Plans | Albania- GNTP (2015-2030) | Kosovo- NSP (2010-2020+) |

|---|---|---|

| Vision | Albania as an Integrated centre in the infrastructural and Economic European system, with a diverse and competitive economy in the Balkan space. A country that aims at parity of access in infrastructure, economy and knowledge. Ensuring protection of the natural, cultural and historical heritage with the aim of becoming an authentic destination. | A country integrated in the European Union; with sustainable socio-economic development, modern infrastructure and technology, with opportunities for education for all and a skilled workforce; a country that respects the environment, the natural and cultural heritage of its territory and its neighbours; an open society that promotes diversity and the exchange of ideas while respecting the rights of all. |

| Strategic Objectives | SO3. Ensuring physical and territorial integrity of the historic, cultural, natural and urban landscape in the whole Albanian Territory | SO3: Sustainable environmental development, balanced spatial development, preservation, and respect of resources – natural and cultural heritage of its territory and neighbours |

| Creating conditions for the protection of ecosystems, biodiversity, natural resources above and below ground, as well as of natural and cultural heritage, by balancing the impacts of settlements and economic activities. | - Planning the space for rational use of the territory - Environmental Protection - Balanced spatial development - Stimulating rural development policies - Utilisation of minerals for a sustainable development - Protection and sustainable use of natural and cultural heritage - Regulation of illegal constructions and informal settlements |

|

| Other Policies | Promotion of regional clusters based on cultural and historic heritage; Protection and promotion of cultural heritage as an asset to support urban development improving access to the cultural heritage |

The plan offers a map of protected areas and monuments; however, no reference is made to the approach that urban areas should take in terms of preserving cultural heritage. |

Source: General National Territorial Plan of Albania, (2016); National Spatial Plan of Kosovo (2010).

Clearly, in both plans, cultural heritage plays an important role. While in Kosovo there is a more traditional ‘containment’ paradigm, where the plan focuses on delineating protected areas, in Albania the approach is broader. There is a general attempt not only to define protected areas, but also to integrate cultural heritage with other policies such as tourism and urban development.

After considering the spatial planning framework in Albania and Kosovo, understanding also sectoral legislation and the institutional framework in the cultural and historic heritage is important. Table 4 offers an overview of the legislation, institutions, and instruments at the national and local level:

| Variable | Albania | Kosovo |

|---|---|---|

| Legislation | Law 27/2018 “On Cultural Heritage and Museums” | Law 02/88 “On Cultural Heritage” |

| Definition of Cultural heritage | Cultural heritage includes tangible and intangible cultural wealth, as a set of cultural values, bearers of historical memory and national identity, which have scientific or cultural significance | Architectural, archaeological, movable and spiritual heritage, regardless of the time of creation and construction, type of construction, beneficiary, creator or implementer of the work. The scope of the law should be defined for issues specifically related to cultural heritage. Cultural heritage related to or derived from religious denominations will also be governed by legislation governing the status of religious communities in Kosovo. |

| Institutions | - Ministry of Culture - National Council for the Management of Cultural Heritage - National Inspectorate for the Protection of Cultural Heritage National Institute for Cultural Heritage National Institute for the Registration of Cultural Heritage Regional Directorates of Cultural Heritage Institute of Archaeology |

Ministry of Culture Council of Kosovo on Cultural Heritage Inspectorate of Cultural Heritage |

| Local Institutions | Municipalities | Communes (Municipality) |

| What is considered cultural heritage? | among others: - immovable and movable property, which have artistic, urban, historical, archaeological or ethnographic interest of special importance |

Architectural heritage” consists of: a) Monuments: Constructions and structures distinguished in terms of historical, archaeological, artistic and scientific values of social or technical interest, including movable elements as part of it. b) Ensembles or totality of buildings: Groups of urban or rural buildings distinguished by historical, archaeological, artistic, scientific values, of social or technical interest, in interaction with certain topographic units. c) Areas of architectural conservation: Areas that contain combined works of human hand and nature, distinguished by historical, archaeological, artistic, scientific, social and technical interest. |

Source: Law 27/2018 “On Cultural Heritage and Museums”; Law 02/88 “On Cultural Heritage”.

Based on this overview, one can see that the legal and institutional frameworks for both countries are similar. In Albania, the law recognises the role that spatial planning plays in terms of cultural heritage protection and promotion. The planning instruments such as GLTPs[1] and DNPANI[2] are considered as instruments that need to incorporate cultural heritage and policies regarding it. In Kosovo there are similar legal provisions. From the coordination standpoint, in Albania, the Ministry of Culture and other respective national institutions of cultural heritage are consulted when planning instruments are prepared.

Tirana and Pristina are the capital cities of Albania and Kosovo, respectively. The cities were only named capital cities in the last century: Tirana in 1920 and Pristina in 1946, following the end of the Second World War, while Kosovo was still part of Yugoslavia. Following the end of the dictatorial regime in Albania (1991) and the end of the Kosovo War (1999), both capital cities faced rapid urbanisation, accompanied by a relevant economic growth tendency. During the first decades of transition, i.e. 1991–2000 for Tirana and 2000–2010 for Pristina, besides the densification of the cities with new construction, informal development also was a common factor (Ministry of Environment and Spatial Planning Kosovo, 2010; Allkja, 2019). Planning institutions were unable to coordinate and manage development, even in cases where this was done through legal instruments and construction permits were issued. Planning in the initial stages of the transition was weak and could not respond to the socio-economic dynamics. Both cities quickly evolved into the socio-economic centres of their countries and their populations almost tripled in less than two decades.

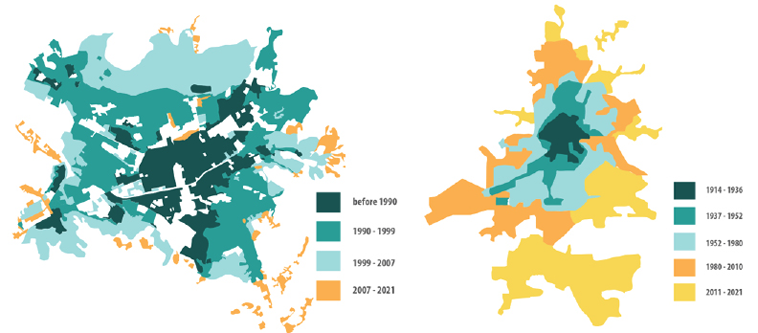

The quick population growth was also reflected in the urban fabric. Uncontrolled sprawl occurred in the outskirts of the cities, while within the centres, due to unplanned development, the cities underwent densification with little regard to cultural heritage, or attempts to preserve historic or distinct urban quarters. Most of the development has produced apartment blocks, while recently there is also a growing tendency of high-rise buildings (i.e. over 20 floors) in the city centre as seen in Fig. 1. Construction and densification trends continue to remain high in both cities.

Fig. 1. Urban Development Growth and Extension through time – Tirana and Pristina

Source: own work based on Co-PLAN, 2021; CDP Pristina – Map of Urban Development.

Pristina drafted its Municipal Development Plan in 2012 for the 2012–2022 period, while Tirana drafted its GLTP in 2013, then reviewed it due to the Territorial and Administrative Reform in 2016. Both cities have key planning instruments and they are now working on detailed local plans and detailed regulatory plans. Considering that the plans were drafted and approved in similar timeframes, it is interesting to compare their visions, objectives, and policies regarding cultural heritage. Table 5 offers an overview of that:

| Local Plans | Tirana | Pristina |

|---|---|---|

| Vision | Polycentric and kaleidoscopic metropole in equilibrium between urban and nature | A capital city for a new state; a city for youth; a territory with high quality |

| Objectives | An intensive and polycentric city an accessible city a city with biodiversity a Mediterranean centre a creative city a smart city an inclusive city A Balkan Garden a 24h city |

Sustainable economic development and employment growth in an attractive and creative city Pristina in World Networks Provide citizens with an effective and quality system of public services and a comfortable urban environment Moving people and goods efficiently and steadily Strengthening identity by valuing the historical and cultural landscape Rural development and preservation of natural heritage Towards a new model of urban spatial development |

| Policies on Cultural Heritage | Strategic Project 08- Protection of the Architectural Heritage of the 20th Century: protection of urban and rural landscape identification of areas constructed during different time periods such as ottoman empire; Italian occupation; dictatorial regime; areas with strong identity of villas, buildings, gardens etc collaboration with stakeholders (universities and ministry of culture) to propose new ways of treating the urban landscape |

Valorisation of historical heritage (Development of regulatory plans for the city centre and the historic area; rehabilitation of religious and historical sites, etc.); Promotion and development of various forms of tourism: archaeological tourism, eco-tourism or green tourism, taking advantage of nature and beautiful landscape; cultural tourism combined with rural tourism; Expansion of tourist attractions (qualify museums, etc.); Maintenance and creation of tourist infrastructure; |

Source: General Local Plan of Territorial Development of Tirana, 2015; Urban Development Plan of Pristina, 2012.

As seen in Table 5, both strategic plans offer clear visions for the development of the respective cities and at the same time have a strong component of cultural heritage. Compared to Pristina, Tirana has expressed its objectives through 13 key projects, one of them being dedicated to cultural heritage, and more specifically to the architectural heritage of the 20th century. This approach seems quite promising and shows that local authorities have an increased awareness in terms of the importance of cultural heritage for the future development of the city.

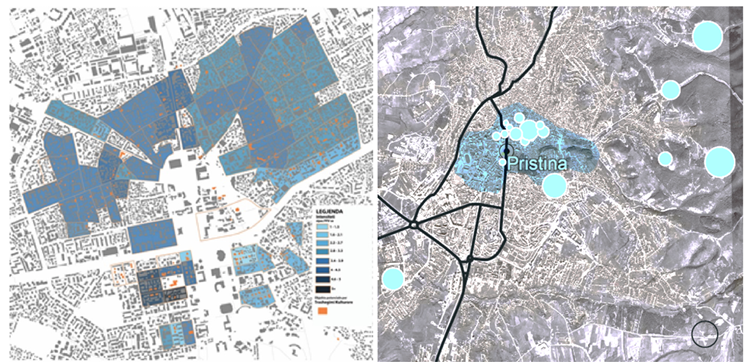

Despite their similar socio-economic development, the cities of Tirana and Pristina display distinctive typologies of culturally relevant assets and areas. In Tirana, the array of such cultural monuments ranges from traces of historic residential areas in the old city centre to more recently established low-rise housing built in the 1930s in the ‘Italian style’, and a rich catalogue of administrative and recreational buildings built in the 1920s or later. Pristina’s culturally significant areas include developments after the Second World War, which reflect a rare modernist architectural style. In both cities, religious monuments are also considered of high cultural relevance. The maps in Figure 2 show areas with cultural and historic heritage in Tirana and Pristina, as reflected in their respective planning documents. The map of Tirana shows the ‘density’ of culturally relevant buildings within each zoning area, while the Pristina map shows the location of cultural monuments in the territory.

Similarly to the city of Tirana, Pristina also has distinct areas that show a high potential for cultural and historic heritage that could be preserved and enhanced in the wider general framework of urban development. However, unlike in Tirana, the municipality only identifies the protected historical and cultural heritage.

Fig. 2. Potential cultural preservation areas, Tirana and Pristina

Source: Muka, R., 2020 (based on GLTP of Tirana, 2015), edited by authors;

Urban Development Plan of Pristina, 2012, edited by authors.

The Block area in Tirana and “Qyteza Pejton” in Pristina are two of the most intriguing sites located near the city centres, with considerable relevance for cultural and historical heritage. In both locations, low-rise villas were developed in the 1950s, displaying aesthetical and stylistic innovation for the time. The Block Area was reserved for the dictatorial regime’s political leaders and their immediate families. The general public had limited access to this area, and people could only enter if they had a pass. Following the fall of the regime, the block area became one of the most vibrant destinations in the city, with a plethora of recreational sites, as well as office and service outlets. Regardless of the drastic densification processes it has undergone, the area remains one of the most interesting parts of the city, due to its architectural value and symbolism associated with the communist era. The densification of the Block Area has occurred at the plot level, rather than area level, which entails both positive and negative outcomes. In terms of the former, the recent developments have not disrupted the rectangular pattern of the site. For the latter, though, plot-based development has a strong negative impact on the existing urban tissue, it is disproportional in scale and aesthetics, and causes a loss of urban quality.

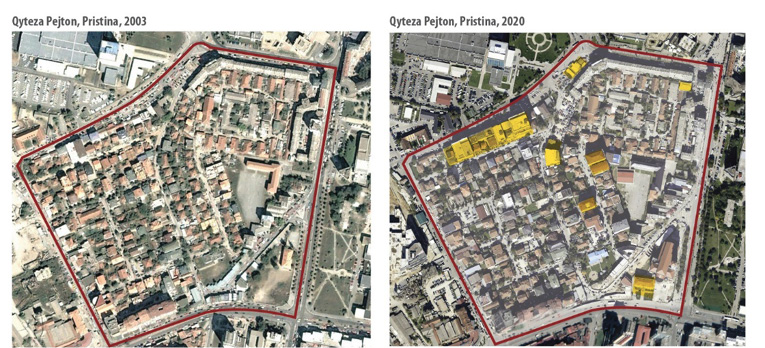

Similarly, “Qyteza Pejton” was developed with typologies of low-rise villas with high aesthetic and urban quality. During the Yugoslavian regime this was considered as a high-end area, hosting foreign embassies and administration. After the 2000s, the area became quite a vibrant destination, with several bars and restaurants, and many recreational facilities. In recent decades, there have been several point developments in the area, which do not affect drastically the overall quality of space (see Fig. 4).

Fig. 3. New high-rise developments at ‘Block area’, Tirana, disrupting the low-density urban pattern

Source: State Authority for Geospatial Information, 2021.

Fig. 4. New Developments disrupting the traditional urban tissue of Qyteza Pejton, Pristina

Source: Geoportal Kosovo, 2020.

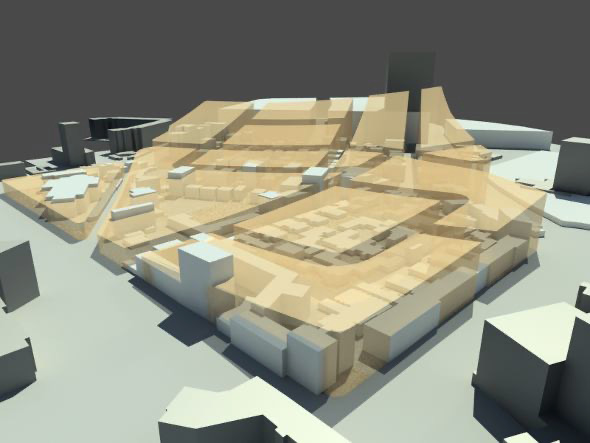

If one considers the commitments of municipalities in their planning documents to preserve the cultural built environment, these two sites would thoroughly fit the criteria for cultural and heritage preservation. However, when considering the land-use and density proposals and the local detailed plans of both areas, the opposite occurs. In Tirana, the GLTP proposes for the respective units (zones) of the Block Area[3] an increase in the intensity of development (FAR[4]), ranging from 3.5 to 5.5. This number is very high in regards to the capacity of the roads and public spaces to accommodate such density. These types of intensities suggest a complete transformation of the area from low-rise villas to high-rise developments, thus destroying the existing urban fabric. Similarly, “Qyteza Pejton” is also expected to redevelop, in order to accommodate medium to high-rise developments. Looking at the Local Detailed Regulatory Plan, the area is expected to undergo a complete transformation from a low-rise neighbourhood with modern villas towards a high-rise area with apartment blocks. The Municipality states that this design (Fig. 5) is a compromise between the development needs for high-rises and the existing low-density structure. Though it does commit to preserving some of the existing facades and the general layout (Municipality of Pristina et al., 2011).

Fig. 5. Development Concept for Qyteza Pejton

Source: Municipality of Pristina, A-Design, Atelier 4, 2011.

The analysis of these two distinct neighbourhoods shows a clear discrepancy between the expressed visions and objectives of the respective cities, and the ongoing development. On the one hand, they are potential areas for cultural heritage preservation and represent a distinct historical period of the city (though recent), while on the other, the approach by the local authorities in planning does not match the vision and the objectives of the respective local plans. Either case lacks any evaluation or awareness of the value of the places for city development, or any research or policy impact assessment whether the modernise or preserve and use these areas for the development of the city.

While urban planning should take a comprehensive and integrated approach in both countries and cities, the practice continues to regard cultural heritage in an individualistic approach, focused on buildings and objects, rather than the values that certain areas have in the city. Although the two cases presented reflect two small areas in the respective capital cities, the approach seems to be replicated, to some extent, in other cases as well. A clear example of the singular approach to cultural heritage through urban planning in Albania is the large discourse and discontent regarding the demolition of the National Theatre building in Tirana.[5] In this case, the discussion, led by public authorities, was oriented in two main directions. The National Theatre building, although constituting part of the city centre ensemble, and built in the same time-frame as other buildings, did not have a cultural heritage status, hence the building itself was proclaimed not to have any distinct architectural value. The second direction was to exclude stakeholder groups from discussions and decision-making by directing the whole public discussion and debate towards the needs of the artists to have a performance space, rather than arguing on the building and adjacent space as public property. This ‘smokescreen’ participatory process has been very present in institutional decision-making in Albania in recent years (Imami et al., 2019). The building was destroyed on 17 May 2020 amid protests of citizens and stakeholders and with highly questionable legal actions by the municipality of Tirana.

Similarly, in Pristina, there is a general approach to deal with individual buildings rather than urban ensembles. Historical neighbourhoods are being quickly transformed through private interventions of citizens to expand their living space, as well as through private investment in property development. Hence, individual buildings that do not have a recognised architectural or cultural heritage value (by respective institutions) are quickly being re-appropriated or destroyed thus creating a mixture of developments that do not fit with one another. These transformations, having become substantial covering the majority of the area, have led to a complete revamping and change in the city structure and the historical values of the neighbourhoods, while singular buildings that have a protected status are left as stand-alone buildings in the middle of new developments. Additionally, although legal provisions allow the use of Financial Instruments of Land Development, there is no evidence of their use in either of the cities. These instruments offer great opportunities and prospect in terms of supporting certain areas with additional funding and schemes for the protection and enhancement of cultural heritage areas.

Fig. 6. National Theatre of Albania

Source: Leeturtle via Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:National_Theater_of_Albania_(cropped).jpg [accessed on: 21.05.2021].

In this paper we investigated the ways in which cultural heritage is incorporated in territorial and spatial planning in Albania and Kosovo. The focus was to examine the extent to which cultural heritage is preserved and enhanced through spatial planning practices in developing countries. Our findings suggest that there are significant discrepancies between the legal and institutional framework provided at the local and national levels and the actual development and land management processes. We discovered that cultural heritage is a priority in both Tirana and Pristina, as specified in their respective ‘city constitutions,’ or municipal territorial plans. Nonetheless, the cities have failed to systematically incorporate cultural heritage in city initiatives or capitalise on it as an asset. On the contrary, in both cases areas of vast cultural interest have been redeveloped to accommodate new residential or commercial uses. This not only contradicts the engagement of the cities towards spatial planning at the EU and national levels (as well as the local level), but it also shows that ad hoc land development practices supersede the relevance of cultural heritage preservation, both in the eyes of land owners and local government.

In order to compensate for this pure economical factor, the municipalities need to develop capacities to enforce and implement land development instruments, such as transfer of development rights, betterment fees, Bonus Intensity, and other value capture instruments. While the legal milieu has been established for over a decade for these instruments, and their success has been continuously proven in even more challenging contexts in Latin America and Asia in the past 30 years, these implementation attempts have failed so far. Participatory planning has also failed as it has become a merely bureaucratic process. In Tirana, there are signs of a failed democracy, following the events of the demolition of the National Theatre. It is time to empower communities and capitalise on their dynamics and liveability in order to enforce better bottom-up decision-making at the city level. Fundamentally, as explained by Gunay (2008), what we leave behind today will be the living evidence of our lifestyle and knowledge for future generations.

AL-HOUDALIEH, S. and SAUDERS, R. (2009), ‘Building Destruction: The Consequences of Rising Urbanization on Cultural Heritage in the Ramallah Province’, International Journal of Cultural Property. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0940739109090043

ALLKJA, L. (2019), ‘Territorial Governance through Spatial Planning in Albania and Kosovo’, Annual Review of Territorial Governance in the Western Balkans, pp. 42–53. https://doi.org/10.32034/CP-TGWBAR-I01-04

ANGELIDOUA, M., KARACHALIOUA, E., ANGELIDOUA, T. and STYLIANIDIS, E. (2017), ‘Cultural Heritage in Smart City Environments’, The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, pp. 27–32. https://doi.org/10.5194/isprs-archives-XLII-2-W5-27-2017

ASIG (2021), Orthophoto, retrieved from Geoportal: https://geoportal.asig.gov.al/map/?fc_name=qytete&auto=true

BERISHA, E., COLIC, N., COTELLA, G. and NEDOVIĆ-BUDIĆ, Z. (2018), ‘Mind the Gap: Spatial Planning Systems in the Western Balkans Region’, Transactions of the Association of European Schools of Planning, 2 (1), pp. 47–62. https://doi.org/10.24306/TrAESOP.2018.01.004

CHEN, F., LUDWIG, C. and SYKES, O. (2020), ‘Heritage Conservation through Planning: A Comparison of Policies and Principles in England and China’, Planning Practice & Research. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2020.1752472

Directorate-General for Education, Youth, Sport and Culture (European Commission) (2018), Participatory governance of cultural heritage, Luxembourg: European Union. https://doi.org/10.2766/765030

DOBRICIC, M., RISTIC, S. and JOSIMOVIĆ, B. (2016), ‘The spatial planning, protection and management of world heritage in Serbia’, Spatium, 1, pp. 75–83. https://doi.org/10.2298/SPAT1636075D

EU (2007), Territorial Agenda of the European Union – Towards a More Competitive and Sustainable Europe of Diverse Regions, Leipzig: Informal Ministerial Meeting on Urban Development and Territorial Cohesion. https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/information/publications/communications/2007/territorial-agenda-of-the-european-union-towards-a-more-competitive-and-sustainable-europe-of-diverse-regions

EU (2011), Territorial Agenda of the European Union 2020 – Towards an Inclusive, Smart and Sustainable Europe of Diverse, Godollo, Hungart: e Informal Ministerial Meeting of Ministers responsible for Spatial Planning and Territorial Development. https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/information/publications/communications/2011/territorial-agenda-of-the-european-union-2020

EU (2020), Territorial Agenda 2030: A future for all places -Draft. https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/information/publications/brochures/2021/territorial-agenda-2030-a-future-for-all-places

EUROPEAN COMMISSION (1999), ESDP – European Spatial Development Perspective: Towards Balanced and Sustainable Development of the Territory of the European Union, EC. https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docoffic/official/reports/pdf/sum_en.pdf

FALUDI, A. (ed.) (2007), Territorial cohesion and the European model of society, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. https://www.lincolninst.edu/publications/books/territorial-cohesion-european-model-society

FINPIEMONTE (2021), Financial Instruments and Innovative Financial Schemes for Cultural Heritage, INTERREG Europe Project, financed by the European Regional Development Fund. Available online: https://www.interregentral.eu/Content.Node/02.- Financial-schemes.pdf

GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF THE UN (2015), Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, United Nations. https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda

GEOPORTAL (2020, November 02), Orthophoto Pristina, retrieved from Geoportal Kosovo: http://geoportal.rks-gov.net/search?municipalityId=19

GUNAY, Z. (2008), ‘Neoliberal Urbanism and Sustainability of Cultural Heritage’, 44th ISOCARP Congress Proceedings. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.572.8293&rep=rep1&type=pdf

GUZMAN, P. and RODERS, A. P. (2014), ‘Bridging the gap between urban development and cultural heritage protection’, “IAIA14 Conference Proceedings” Impact Assessment for Social and Economic Development, Vina del Mar, Chile: 34th Annual Conference of the International Association for Impact Assessment. https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.4633.7923

IMAMI, F. and DHRAMI, K. (2019), ‘Strengthening cooperation for spatial planning: A case study on participatory planning in Albania’, [in:] Annual Review of Territorial Governance in Western Balkans, 1, Co-PLAN and POLIS press. http://www.co-plan.org/en/strengthening-cooperation-for-spatial-planning-a-case-study-on-participatory-planning-in-albania/

JELINCIC, D. A. and ŠVEB, M. (2021), ‘Financial Sustainability of Cultural Heritage: A Review of Crowdfunding in Europe’, Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 14, p. 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14030101

MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT AND SPATIAL PLANING; INSTITUTE FOR SPATIAL PLANNING (2010), National Spatial Plan of Kosovo 2010-2020+, MESP. http://www.ammk-rks.net/repository/docs/Spatial_Plan_of_Kosova_2010-2020.pdf

MUKA, R. (2020), ‘Co-existence of urban cultural heritage with future developments in the city of Tirana through Financial Instruments of Land Development’, Master’s Thesis, Polis University.

MUNICIPALITY OF PRISTINA (2011), Regulatory Detailed Plan Pejton. Pristina: Municipality of Pristina. https://prishtinaonline.com/uploads/1.qyteza_pejton_13.06-shqip.pdf

MUNICIPALITY OF PRISTINA (2012), Communal Development Plan 2012-2022. Pristina: Municipality of Pristina. https://kk.rks-gov.net/prishtine/wp-content/uploads/sites/45/2018/02/PZHU-_Prishtina.pdf [accessed on: 26.11.2020].

MUNICIPALITY OF TIRANA, UNLAB (2015), General Local Plan for the Development of Territory, Municipality of Tirana. http://planifikimi.gov.al/index.php?id=732

NIJKAMP P., BAL, Fr. and MEDDA, Fr. (1998), ‘A Survey of Methods for Sustainable City Planning and Cultural Heritage Management’, Serie Research Memorandum, Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam. https://lib.ugent.be/catalog/rug01:001454739

NTPA; MINISTRY OF URBAN DEVELOPMENT; ATELIER ALBANIA (2016), National General Plan Albania 2030, NTPA. http://planifikimi.gov.al/index.php?id=ppk_shqiperia&L=2

PARLIAMENT OF ALBANIA (2018), Law 27/2018 On cultural heritage and museums. https://kultura.gov.al/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Ligji.nr27-_dt.17-05-2018.pdf

PARLIAMENT OF KOSOVO (2008), Law 02/88 On Cultural Heritage. https://gzk.rks-gov.net/ActDocumentDetail.aspx?ActID=2533

RODERS, A. P. and OERS, R. V. (2011), ‘Editorial: bridging cultural heritage and sustainable development’, Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development, 1 (1), pp. 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1108/20441261111129898

UN (2017), New Urban Agenda, United Nations, Habitat III. https://habitat3.org/the-new-urban-agenda/

UNESCO (1968), Recommendation concerning the preservation of cultural property endangered, Paris: Records of the General Conference of UNESCO Fifteen Session. http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=13085&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html

UNESCO (1976), Recommendation concerning the safeguarding and contemporary role of historic areas, Nairobi: Records of the General Conference of UNESCO Nineteenth Session. http://portal.unesco.org/en/ev.php-URL_ID=13133&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html

UNESCO (1982), World Conference on Cultural Policies: final report, Paris: UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000052505

UNESCO (2019), The UNESCO Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape, Paris: UNESCO. https://whc.unesco.org/en/hul/