Abstract. The article aims to show the main political-geographic trends of the 2020 parliamentary elections in Georgia. The political systems of the post-Soviet counties are still imperfect and fragile. Although international observers recognised the vote results in Georgia as legitimate, many opposition parties boycotted the parliament for almost six months. It took several western officials to engage in regulating the post-election crisis. The work focuses on analysing turnout and voting patterns pointing to the changes that occurred in the last decade. A geographical study of elections enables one to identify the merits and drawbacks of the electoral process from the regional standpoint. The findings of the work underline the complexity of the election outcomes. While certain legal and political changes bring Georgia closer to European democracies, the country still lags in terms of several electoral/geographical features.

Key words: Georgia, parliamentary elections, voter turnout, voting, election districts.

The mapping of election results and identification of the geographic aspects of voting behaviour are still among the major topics of electoral geography (Kovalcsik and Nzimande, 2019, p. 10). A territorial overview of elections may serve as a good illustration of the progress that Georgia has made towards more democratisation.

The article deals with the main political/geographical trends of the 2020 parliamentary elections in Georgia which are compared to those of the previous three elections, i.e. in 2008, 2012, and 2016. The research focuses on analysing regional data on election turnout and voting patterns pointing to the changes that occurred during the last decade.

The research employs the following methods: collection–processing–analysing official data provided by the Election Administration of Georgia and National Statistics Office of Georgia; a review of academic works on the subject, as well as reports of international organisations and NGOs; GIS technologies for preparing and integrating maps through ESRI ArcGIS; and visual presentation of the results – Adobe Illustrator.

The main research method consisted of collection, processing, and analysis of official data. The major portion of the election data was obtained from the official website of the Election Administration of Georgia. The supreme body of the Election Administration of Georgia is the Central Election Commission (CEC), which directs, manages, and controls work of all (territorial) levels of election commissions (Election Administration of Georgia, 2021). In few cases, data provided by the Parliament of Georgia was used.

A significant part of the paper is dedicated to the analysis of voter turnout (VT). In order to measure VT, we used the method of registered turnout (the ratio of those who voted among those registered as eligible voters) which is traditionally used by the Georgian election authorities.

In order to review and assess political and legal variables of the elections, we considered reports and results of exit polls of the following international organisations/NGOs: OSCE – ODIHR, International Republican Institute (IRI), National-Democratic Institute (NDI), Edison Research, IPSOS, etc. One of the approaches of the research was based on the method of critical review and analysis of the academic literature on the subject.

For data storing, processing, and preparation for visualisation Open Geospatial Consortium (OGC) standards were used. For the integration of the collected/received and spatial data RDBMS (PostgreSQL/PostGIS) was used. This approach enabled us to create plan links between electoral districts/precincts and statistical data. Data preparation for mapping was based on GIS (QGIS): this tool permitted us to create a mapping model according to the aforementioned plan. The final design of the maps was done by Adobe Illustrator. As a result, we received static maps without interactive possibilities, however, a further implementation of internet technologies, based on the existing data, can offer much more flexible possibilities.

The 10th parliamentary elections in Georgia were held on 31 October 2020. There have been 150 members in the single-chamber Parliament of Georgia since 2008. Until 2016 it was elected through a mixed system – half or little more of the MPs as per party lists and the remaining portion as direct candidates, normally nominated by parties, who ought to receive 50% + 1 vote in their election districts.

Before 2003 the results of the elections were easily predictable: the winner always was the ruling party/political bloc. The so-called Rose Revolution of 2003 staged by opposition parties led by the United National Movement (UNM) under Mikheil Saakashvili changed the pattern. But the Rose Revolutionaries who declared the parliamentary elections of November 2003 rigged and triggered snap elections in March 2004, followed double standards from the very beginning: the snap elections easily won by the UNM concerned just a half of the Parliament and were held according to party lists only.

Georgia was a presidential republic since April 1991. After changes in the Constitution in 2010, the country gradually became a parliamentary republic. Thus the elections to the Parliament which has a fixed term of four years became the most important political event in the country.

The 2012 parliamentary elections were won by a newly established political bloc Georgian Dream – Democratic Georgia (GD) under Bidzina Ivanishvili. The former ruling party, the UNM, retained a substantial base of supporters and became the strongest opposition party. Throughout the 2010s there was a political competition in Georgia between the two largest parties – GD and the UNM – which combined received approx. 95% of all votes in the 2012 parliamentary elections and 75% in 2016 and 2020 elections.

A negative attitude of a substantial number of the Georgian voters towards the UNM has been successfully used by GD to mobilise their base to win all elections since 2012. But Georgians became somewhat tired of the same party (GD) running the country for 8 years. This trend could be seen in the results of the 2020 elections in the largest city, Tbilisi (see below).

There was a common demand from several parties to change the mixed electoral system into an entirely proportional one. The GD-majority Parliament adopted changes in the Constitution in 2018 which established the elections to the parliament on an entirely proportional basis to be held from 2024. Opposition parties demanded the introduction of the proportional system already in 2020. It took the joint mediation of the Council of Europe Office, the EU Delegation, and the US Embassy in Tbilisi to reach a compromise political agreement between all political stakeholders on the electoral system in Georgia on 8 March 2020. According to the new law, 120 members of the 2020 Parliament were to be elected by proportional representation and 30 members – in single-mandate districts. In order to permit a larger representation of parties and restrict the dominance of one party, a temporary electoral threshold of 1% was introduced. A capping mechanism for the number of mandates for a single party was established. A complete change to the proportional system is planned for 2024.

Formally, participation in elections is a civil duty of citizens and, therefore, VT indicates the level of involvement of the population in the political life of a country.

Table 1 reveals that the absolute number of eligible voters remained more or less stable in Georgia throughout the 2010s. According to national legislation, all citizens residing abroad and having valid Georgian passports are enrolled in electoral lists. Georgian voters living abroad are eligible to vote in electoral precincts, opened on the premises of Georgian diplomatic missions in many but not every foreign country. Many eligible voters, if residing far away from an electoral precinct or staying abroad on an illegal basis, avoid voting.

| Year of elections | Registered voters | Actual votes | Voter turnout (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 3,465,736 | 1,850,407 | 53.39 |

| 2012 | 3,621,851 | 2,215,661 | 61.31 |

| 2016 | 3,473,316 | 1,814,276 | 51.63 |

| 2020 | 3,501,931 | 1,970,540 | 56.11 |

Source: Own work based on data of the Election Administration of Georgia [parliamentary elections 2008, 2012, 2016, and 2020].

Some scholars (e.g., Blais and Rubenson, 2012; Kostadinova, 2003, Kostelka, 2014, Solijonov, 2016) have argued that VT has a declining trend in post-communist societies. Statistics show that an average decline of VT in such societies amounts to 1% per year. M. Comsa’s research revealed that the decrease in VT is characteristic for a majority of post-communist countries, but six exceptions were mentioned: VT remained stable in Hungary, while in Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Serbia, and Tajikistan it even increased (Comsa, 2017, p. 31). VT decreased significantly in Georgia from approx. 70% in the early 1990s to 53% in 2008. However, during the last 12 years, a steady decrease in VT has not been observed.

Based on an overview of theoretical works in this field several sets of concepts/hypotheses could be proposed to explain the VT decline.

In the first set, we include two intertwined concepts: “post-honeymoon effect” and “post-communist demobilisation” (Inglehart and Catterberg, 2002; Kostadinova, 2003). The former implies that soon after the downfall of communist regimes the citizens of these countries got disappointed with the worsening of the socio-economic situation which did not meet their high expectations. This could be an explanation of the rapidly growing electoral absenteeism in such societies. In the case of the latter, a sort of demobilisation was observed: after decades of the communist rule a part of people simply decided not to participate in the elections at all. The latter phenomenon was apparent for a short period of time, mainly the 1990s, therefore it cannot serve to explain why VT declined steadily in the following decades.

The second set of concepts explaining a long-term decline of VT is related to deteriorating economic and political conditions. The first years of the new democracies have been characterised by severe and growing economic hardship (such as hyperinflation and increasing unemployment), which had a negative impact on VT (e.g. Bell, 2001; Pacek et al., 2009). However, other studies indicate that there is no obvious correlation between VT and the economic situation. Despite the facts of political instability, e.g. “colour revolutions”, corruption, scandals, and intrigues within parties, there is no clear link between political conditions and the decline of VT (e.g., Blais and Dobrzynska, 1998; Geys, 2006, Kostadinova, 2003).

The third set is related to the importance of elections or to the concept of “electoral (political) stakes” (Downs, 1957; Riker and Ordeshook, 1968; Tullock, 1967), which shows that the electorate tends to differentiate between important and less important elections. This became more obvious soon after the fall of communism. Voters in the new democracies would participate more actively in the elections when more was at stake. The hypothesis has found empirical support (e.g., Pacek et al., 2009). In this paper, we argue that in contemporary Georgia VT highly depends on political stakes.

The fourth set includes such institutional variables as mandatory or compulsory voting, voting system type, voting age, population size, and income inequality (e.g., Power, 2009; Stockemer, 2017). We believe that none of the mentioned variables affect significantly VT in Georgia.

A fifth set of factors leading to VT decline are linked to economic globalisation. This hypothesis has been more widely applied in highly developed countries (Brady and McNulty, 2011; Steiner, 2010) and the concept may be applicable to few post-communist countries. As far as Georgia is a country with a less developed economy, the influence of global economic trends on its VT seems negligible.

A sixth set is linked to migration. We argue that migration to a large extent contributed to turnout decline in former communist countries. A significant number of migrants from such countries remain citizens of the country of their origin retaining strong ties with it. They send remittances to their families and try to build businesses in their homelands. In other words, having far-reaching goals the migrants are ready to play an important role in political decision-making. Meanwhile, in the receiving countries many migrants live relatively far from the places where voting takes place (in the case of Georgia, from its embassies or consulates) and due to low accessibility to ballot boxes, an insignificant part of them participates in elections.

To sum up the discussion on the factors affecting VT in Georgia, we came to the conclusion that mass emigration and political stakes played the most influential role in determining the level of voter participation in the parliamentary elections.

It ought to be noted that after the dissolution of the Soviet Union two ethnic conflicts, civil standoff, and economic dislocation ensued in Georgia. Hundreds of thousands of Georgians left the country mostly for Russia and the EU. In the mid-1990s net migration rate amounted to -40 (per 1,000 inhabitants). The negative net migration figure remained high up to 2013 (about -10 per 1,000 inhabitants). Later the figure stabilised at the level of -2 per 1,000 inhabitants (Net Migration Dynamics, 2021). Therefore, during the last 7–8 years migration was still an important but no longer a decisive factor affecting the level of VT.

With migration remaining more or less stable, in the last 12 years voter turnout has no longer been steadily decreasing in Georgia and it sometimes even increased. This could be explained by an approach that argues that post-communist societies actively participate in elections when political stakes are high (Johnston et al., 2007; Matsubayashi and Wu, 2012; Reif and Schmitt, 1980). One research has proven that it happens in 90% of cases, especially in poor countries (Pacek et al., 2009). Further, VT is higher in closely contested elections (Blais, 2006, p. 122) or when the political environment is polarised.

Out of four parliamentary elections in Georgia since 2008, those of 2012 seemed to be important to the majority of voters who desired a change of power in the country. The 2020 elections were also politically important as they were held in a situation of harsh confrontation of political forces: despite the pandemic, 56.1% of people eligible to vote went to polling stations. In contrast, 2008 and 2016 parliamentary elections were held in situations when a substantial part of voters were confident that “nothing would change!”

Georgia is no longer a country with artificially boosted voter turnout. In the recent past, this was quite a problem. For example, in the 2004 presidential elections the officially recorded level of voter turnout was 88% (Saakashvili Declared..., 2008). The inadequacy of 2008 parliamentary elections results is demonstrated by the difference between the districts of the lowest and the highest turnouts which was almost double: in five election districts the voter turnout exceeded 80% and in the other five districts it was below 45%, while the average figure for the country stood at 53.4% (Voter Turnout, 2008).

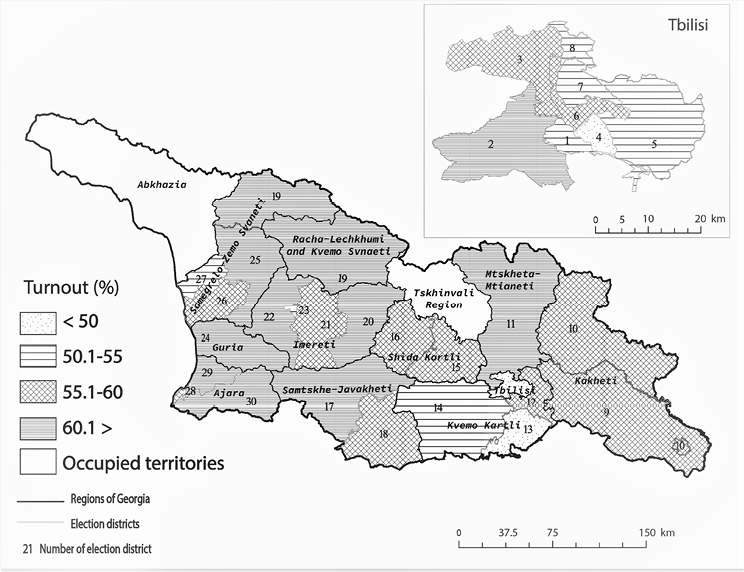

In the 2020 parliamentary elections none of the election districts reported a turnout level exceeding 65% or below 45%. Higher than average turnout was reported in ten election districts, and lower than average – in four (Voter Turnout, 2020) (see Fig. 2).

It must be noted that parts of the internationally recognised territory of Georgia, i.e., Abkhazia and the Tskhinvali region (South Ossetia), are left blank on Figures 1, 3, and 4, as elections are not being held there: they are beyond Georgian jurisdiction due to the deployment of Russian troops and are considered as occupied territories.

Fig. 1. Voter turnout by election districts: 2020 parliamentary elections in Georgia

Source: own work based on data of the Election Administration of Georgia, 2020.

As a rule, Georgia’s rural voters are more active. In the 2020 parliamentary elections voter turnout in all big cities, Tbilisi, Kutaisi (#23), Batumi (#28), and Rustavi (#12), was below the national average (Voter Turnout, 2020). In Georgia’s election history, 2012 parliamentary elections were the only elections when voter turnout was higher in three big cities (Tbilisi, Batumi, and Rustavi) compared to the rest of the country (Voter Turnout, 2012).

The relationship between VT and the incumbent’s performance is another issue for electoral studies. There is no scientifically-supported correlation between VT and an incumbent’s share of the votes (Grofman et al., 1999; Jordan, 2017; Vaishnaw, and Guy, 2018). However, empirical evidence in post-Soviet countries suggests that higher voter turnout means higher votes for the incumbent party. Indeed, the voter register in many countries has been used as a tool for manipulating election results in less democratic societies. Georgia followed the same pattern before 2012. For example, in the 2008 parliamentary elections, the ruling party (UNM) received over 70% of the votes in each of those districts where VT was 70% or higher (Georgian Election Data: Parliamentary, 2008; Voter Turnout, 2008). It is noteworthy that this post-Soviet trend has changed in Georgia during the last two parliamentary elections, a fact which could be attributed to the improvement of the electoral administration.

The low electoral threshold for the 2020 Parliament contributed to the participation of a large number of parties in the elections: there were 48 parties and two electoral blocs registered. Despite the Covid-19 pandemic, which implied many restrictions for mass gatherings, there was an ample possibility for parties to conduct their electoral campaigns. The elections were observed by the International Election Observation Mission (IEOM). Despite some irregularities before and during the elections reported by the IEOM and some observers, the general consensus was that the elections were competitive with fundamental freedoms respected and that parties could campaign freely. The OSCE and the EU were to some extent critical of the elections but cast no doubts about the results (Final Report: OSCE–ODHIR, 2021).

Multiple polls predicted victory for GD, second place with half the votes – to the UNM, and less than 3–4% of votes to 6–7 other parties. On the day of elections, 31 October, four separate exit polls, commissioned by different television stations, all gave the lead to GD and second place to the UNM. The closest to the actual results was the exit poll conducted by Edison Research commissioned by an opposition-leaning TV Formula, which predicted 46% of votes for GD and 28% for the UNM (Diverging Exit Polls Give Lead to GD, 2020).

The actual results were very close to what was predicted. GD garnered 48% of votes according to party lists, and the second was the UNM with 27.2% (Results, 2020). None of the other seven political parties which passed the electoral threshold were able to gather more than 3.8% of votes. For example, European Georgia (EG) created by former members of the UNM who left the latter in 2016 had 21 MPs in the 2016 Parliament but won just 5 mandates in 2020. That was because during the election campaign EG failed to demonstrate it differed from the UNM.

For some, however, the fact of gathering even 2–3% of votes was a certain success, i.e. for the new parties established several months before the elections (Girchi, Lelo, Strategy Aghmashenebeli, or Citizens). These parties were more successful in big cities than in rural areas.

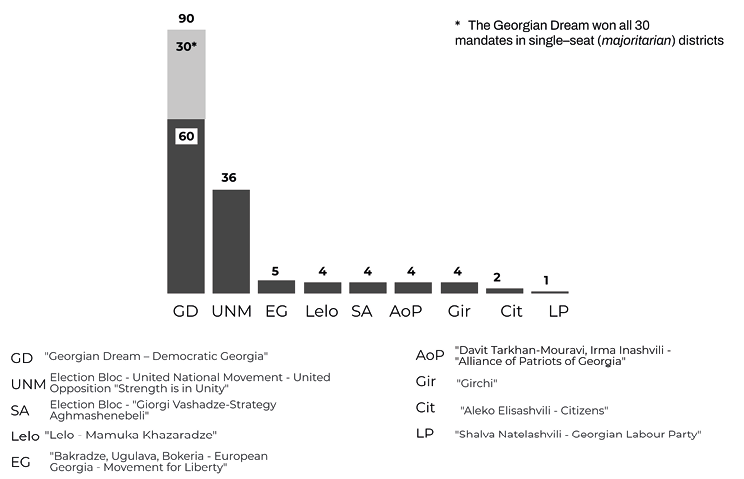

All 30 MPs elected as direct candidates represent GD in the 2020 Parliament. Actually, in the first round, GD had won in just 14 out of 30 electoral districts. The second round in 16 districts where no candidate passed the threshold of 50% had been scheduled to be held three weeks later. In at least 8 districts a strong competition was envisaged among the ruling party and opposition candidates. But opposition parties recklessly boycotting the elected Parliament (see below) did not participate in the second round of the elections, and permitted GD to win easily in all 16 districts. Thus, the number of mandates of GD in the Parliament increased to the pre-set limit for a single party – 90 seats.

The decision by opposition parties led by the UNM to discredit the results of elections by refusing to enter parliament, boycotting the second round of elections, baselessly demanding snap elections could be considered a political mistake. Attempts to organise anti-government rallies were supported by a very small number of people. The tense political situation in the country lasted for almost six months and was finally resolved with substantial diplomatic help of the EU and the USA. The absolute majority of opposition political parties eventually joined the Parliament.

GD received 48% of votes in proportional parliamentary elections, the result almost similar to that of the 2016 elections (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Distribution of Mandates: 2020 parliamentary elections in Georgia

Source: own work based on data of the Election Administration of Georgia, 2020.

A considerable reduction of single-mandate electoral districts did not allow GD to gain a constitutional majority (75%) of parliamentary seats. However, in the 2020 parliamentary elections the ruling party won all 30 single-seat districts.

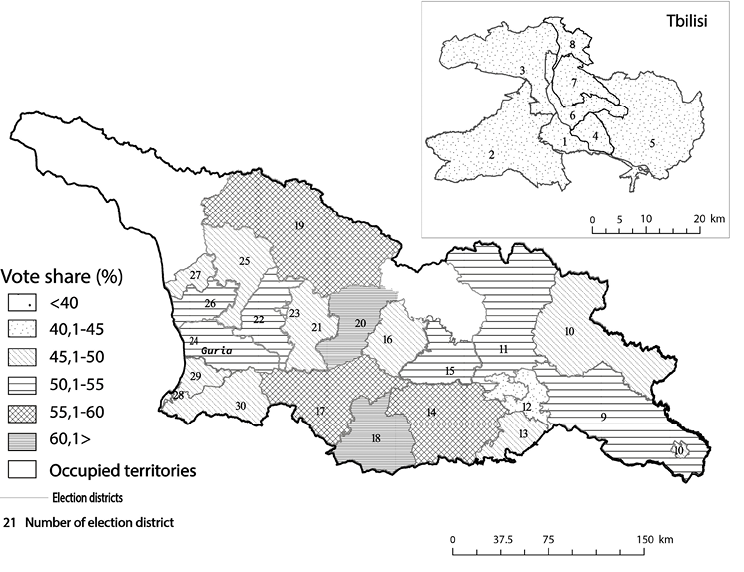

GD traditionally garnered high numbers of votes in Guria, Racha-Lechkhumi, Svaneti, and Mtskheta-Mtianeti. It also solidified its positions in Samegrelo and Samtskhe-Javakheti.

However, its popularity declined in all big cities, as well as in the Kvemo Kartli, Kakheti, and Ajara regions (see Fig. 3).

It is important to note that the ruling party did not receive high support in any of the districts in the 2020 elections, something that had been an acute problem before 2012. GD got over 60% of the votes only in two districts: in Javakheti (district 18) and the easternmost part of the Imereti region (district 20). Javakheti remains an area that traditionally supports all ruling parties, as for district 20 – it is the place where the founder of GD, Bidzina Ivanishvili, was born.

Fig. 3. Votes received by Georgian Dream – Democratic Georgia

Source: own work based on data of the Election Administration of Georgia, 2020.

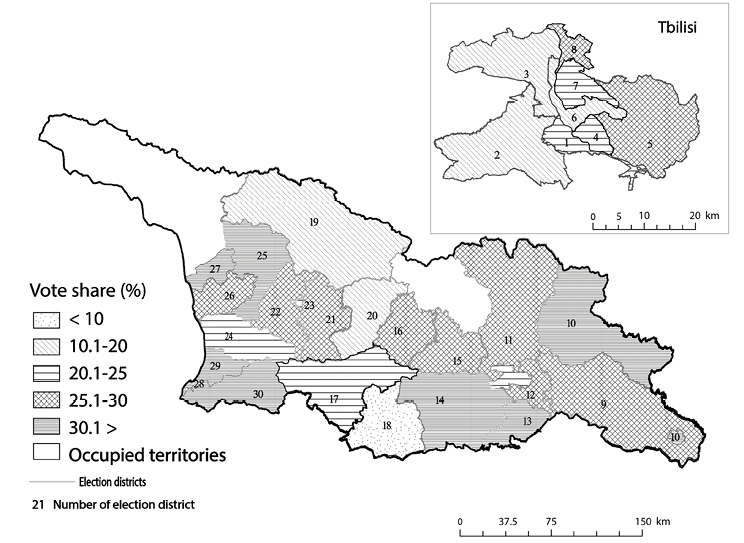

The 2020 elections have proved that the UNM has remained the major opposition force in Georgia. The party suffered a serious intellectual loss soon after the 2016 parliamentary elections when experienced politicians left party ranks. However, the charisma of the ex-president Saakashvili (who has lived in Ukraine in 2013–2021, became its citizen but actively interferes with the policy of Georgia) proved to be strong enough to garner 50,000 more votes to the UNM in 2020 than in the previous elections.

Support for the UNM varies between 20–35% throughout the regions of Georgia. The party achieved better results in Kakheti, Kvemo Kartli, Shida Kartli, and Ajara in 2020 compared with those in 2016, but lost positions in Samegrelo, Imereti, and Samtskhe-Javakheti (see Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Votes received by the election bloc United National Movement – United Opposition “Strength is in Unity”

Source: own work based on data of the Election Administration of Georgia, 2020.

The UNM received very low support (3.9%) in Javakheti, settled predominantly by ethnic Armenians (Results, 2020). There is a possible explanation: after hostilities erupted in Nagorno Karabakh in September 2020 between Azerbaijan and Armenia, Mr. Saakashvili intervened from Ukraine and stated: “Nagorno-Karabakh is a sovereign territory of the Republic of Azerbaijan and nothing will change that” (Saakashvili: Nagorno Karabakh..., 2020). Although the statement was in line with international law, most probably it irritated ethnic Armenian voters in Javakheti and backfired against the UNM.

Political integration of ethnic minorities is gradually improving in Georgia. The case of Kvemo Kartli (districts 13 and 14) is notable from this standpoint. Before 2016, this region, where the majority of the population are ethnic Azeri, unconditionally supported all ruling parties. However, in 2020 that was not the case: the UNM garnered almost 37% of the votes in the mainly ethnic Azeri populated election district #13 (it was the second-highest result for the UNM among the election districts). The increasing political activity of the representatives of ethnic minorities of Georgia and their support for different political parties and not only the ruling one is a positive development.

Tbilisi, being the capital and by far the largest city has a special place in Georgia’s elections. The history of Georgia’s parliamentary elections has proven that Tbilisi is a “protest city”. Ruling parties never enjoyed the absolute majority of votes there. Furthermore, in the 1990 and 2012 elections overwhelming support of the Tbilisi electorate for the united opposition played a decisive role in a power change through the ballot box.

In the last decade, the support for GD among the Tbilisi electorate has been diminishing. As the main opposition force in the 2012 parliamentary elections GD received 68.3% of votes in the capital city, but being the ruling party, it received much less support in the next elections: 47.1% in 2016 and 40.8% in 2020 (Results, 2016; Results, 2020).

Analysis of the last three elections enabled us to identify one more important feature of the Tbilisi electorate. Local voters have a disapproving attitude not only towards the ruling party, GD, but towards the UNM as well. In the 2012 elections the UNM (then ruling party) received much lower support in Tbilisi (27.1%) than in other regions of Georgia. The figure decreased even more during the 2016 (23.3%) and 2020 (22.6%) parliamentary elections (Results, 2016; Results, 2020). In other big cities of Georgia, such as Kutaisi, Rustavi, and Batumi, the UNM had about 10 percentage points higher support than in Tbilisi in 2020.

Tbilisi’s electorate is quite pluralistic. Traditionally, even relatively small parties enjoy some support there. The majority of the votes which were gained by the new parties in 2020, came from big cities, e.g., Girchi received the support of 8% of the Tbilisi electorate, Strategy Aghmashenebeli and Lelo – 6–7% (Results, 2020).

A time/space analysis of recent parliamentary elections has enabled us to conclude that Georgia’s election patterns are now closer to those of European democracies. However, despite some progress, Georgia still lags behind in terms of several electoral-geographic features.

In the last four parliamentary elections in Georgia, the voter turnout varied between 50–60%. For a country of intensive emigration, it is hardly possible to have a higher level of electoral participation.

The history of Georgia’s elections demonstrates that VT was in direct correlation with two main factors: (I) mass emigration (especially during the first 15–16 years after independence had been achieved in 1991), and (II) the domestic political context, i.e. dependence on what the odds at stake are (since 2012).

Improvements to both election legislation and electoral administration have resulted in the elimination of a practice where voter turnout and support for the ruling party were artificially boosted. Thanks to the achievements in election monitoring by political parties, NGOs, and international observers, none of the districts reported unrealistically high turnout or very high support for the ruling party in 2020.

It has been for three parliamentary elections already that two political parties dominate the Georgian political arena. GD and the UNM together garnered three quarters of the votes in 2020. But the opposition, in general, remains weak: it has failed to win even in a single constituency both in proportional or single-mandate elections. In this regard, Georgia is still behind the post-communist countries which are now EU Member States, where the political spectrum is more diverse.

A geographical analysis of electoral behaviour indicates that electoral regions are still in the process of formation in Georgia, although some exceptions could be observed. The Samtske-Javakheti region, where an ethnic minority (Armenians) prevails, traditionally supports the ruling party. On the other extreme, the Kvemo Kartli region with another ethnic minority (Azeri) is turning into a politically pluralistic area, which is a positive development.

The political system of post-communist (especially post-Soviet) countries is fluid, and, therefore, making predictions tends to be difficult (Redžić and Everett, 2020, p. 231).

The purpose of this paper was not to analyse the 2020 elections from a legal or administrative points of view. We would like to note that international monitoring missions positively assessed the recent elections in general, although their reports (Final Report: OSCE-ODIHR, 2021; Parliamentary Election Interim Report: IRI, 2020; Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, 2021) also highlighted problems and challenges.

Acknowledgements. The authors thank Ms. Eleonora Chania for her assistance in producing the maps for this paper.

BELL, J. (2001), The political economy of reform in post-communist Poland, Cheltenham, UK; Northampton, MA: E. Elgar.

BLAIS, A. (2006), ‘What Affect Voter Turnout?’ Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci., 9, pp. 111–25. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.9.070204.105121

BLAIS, A. and DOBRZYNSKA, A. (1998), ‘Turnout in electoral democracies’, European Journal of Political Research, 33 (2), pp. 239–261. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.00382

BLAIS, A. and RUBENSON, D. (2013), ‘The Source of Turnout Decline: New Values or New Contexts?’, Comparative Political Studies, 46 (1), pp. 95–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414012453032

COMSA, M. (2017), ‘Explaining Turnout Decline in Post-Communist Countries: The Impact of Migration’, Studia UBB Sociologia, 62 (LXII), 2, pp. 29–60. https://doi.org/10.1515/subbs-2017-0010

CORSO, M. (2013), Georgia: Low Turnout Overshadows Presidential Election. https://eurasianet.org/georgia-low-turnout-overshadows-presidential-election

CZESNIK, M. (2006), ‘Voter Turnout and Democratic Legitimacy in Central Eastern Europe’, Polish Sociological Review, 4, pp. 449–470.

Diverging Exit Polls Give Lead to GD (2020). http://civil.ge/archives/379162

DOWNS, A. (1957), An Economic Theory of Democracy, New York: Harper and Row.

Election Administration of Georgia (2021), About us: Election Administration of Georgia. https://www.cesko.ge/eng/static/1521/vin-vart-chven

Final Report: OSCE – ODIHR (2021), Limited Election Observation Mission. Georgia Parliamentary Elections, 31 October 2020. Warsaw, May 5, 2021. https://www.osce.org/odihr/elections/georgia/467364

Georgian Election Data: 2008a. Parliamentary – Party List. https://data.electionsportal.ge/en/event_type/3/event/3/shape/30695/shape_type/1?data_type=official

Georgian Election Data (2008), Presidential. https://data.electionsportal.ge/en

Georgia Election Watch Report on October 31, 2020 Parliamentary Elections (2020), National Democratic Institute. https://civil.ge/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/NDI-Georgia-VEAT-Statement-Nov-2-2020-ENG.pdf

GEYS, B. (2006), ‘Explaining voter turnout: A review of aggregate-level research’, Electoral Studies, 25 (4), pp. 637–663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2005.09.002

GROFMAN, B. et al. (1999), ‘Rethinking the Partisan Effects of Higher Turnout: So What’s the Question?’, Public Choice, 99 (3/4), pp. 357–376. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018397327176

INGLEHART, R. and CATTERBERG, G. (2002), ‘Trends in Political Action: The Developmental Trend and the Post-Honeymoon Decline’, International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 43 (3–5), pp. 300–316. https://doi.org/10.1177/002071520204300305

IRI polls: 33% would vote for ruling Georgian Dream, 16% for opposition party UNM (2020). Agenda.ge, 12 Aug 2020. https://agenda.ge/en/news/2020/2526

JOHNSTON, R., MATTHEWS, S. J. and BITTNER, A. (2007), ‘Turnout and the Party System in Canada, 1988–2004’, Electoral Studies, 26 (4), pp. 735–745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2007.08.002

JORDAN, J. (2017), ‘The Effect of Electoral Competitiveness on Voter Turnout’, WWU Honors Program Senior Projects, 43. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwu_honors/43

KOSTADINOVA, T. (2003), ‘Voter Turnout Dynamics in Post-Communist Europe’, European Journal of Political Research, 42 (6), pp. 741–759. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.00102

KOSTELKA, F. (2017), ‘Distant souls: post-communist emigration and voter turnout’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 43 (7), pp. 1061–1063. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2016.1227696

KOVALCSIK, T. and NZIMANDE, N. (2019), ‘Theories of the voting behaviour in the context of electoral and urban geography’, Belvedere Meridionale, 31 (4), pp. 207–220. https://doi.org/10.14232/belv.2019.4.15

MATSUBAYASHI, T. and WU, J. D. (2012), ‘Distributive Politics and Voter Turnout’, Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 22 (2), pp. 167–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2012.666555

Net Migration Dynamics (2021), National Statistics Office of Georgia. https://www.geostat.ge/en/modules/categories/322/migration

PACEK, A., POP-ELECHES, G. and TUCKER, J. (2009), ‘Disenchanted or Discerning: Voter Turnout in Post-Communist Countries’, The Journal of Politics, 71 (2), pp. 473–491. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381609090409

Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (2021). Progress of the Assembly’s monitoring procedure (January-December 2020) [Doc. 15211].

Parliamentary Election Interim Report: IRI (2020). Technical Election Assessment Mission: Georgia. https://www.iri.org/sites/default/files/iri_georgia_team_interim_report.pdf

Population and Demography (2020). National Statistics Office of Georgia. https://www.geostat.ge/en/modules/categories/316/population-and-demography

POWER, T. J. (2009), ‘Compulsory for Whom? Mandatory Voting and Electoral Participation in Brazil, 1986–2006’, Journal of Politics in Latin America, 1 (1), pp. 97–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/1866802X0900100105

Public Attitudes in Georgia (2020). Results of December 2020 telephone survey carried out for NDI by CRRC Georgia during 17–24 December, 2020. National Democratic Institute, Tbilisi, pp. 1–65.

Public Opinion Survey (2019). International Republican Institute – Center for Insights in Survey Research.file:///C:/Users/User/Documents/Elections/2020%20Parliament/IRI%20-20georgia _poll_ 11.18.2019 _final.pdf

REDŽIĆ, E. and EVERETT, J. (2020), ‘Cleavages in the PostCommunist Countries of Europe: A Review’, Politics in Central Europe, 16 (1), pp. 231–258. https://doi.org/10.2478/pce-2020-0011

REIF, K. and SCHMITT, H. (1980), ‘Nine Second-order National Elections: A Conceptual Framework for the Analysis of European Election Results’, European Journal of Political Research, 8 (1), pp. 3–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.1980.tb00737.x

Report (2012), The Central Election Administration. The Elections of the Parliament of Georgia 2012. https://cesko.ge/res/old/other/13/13973.pdf

Results (2016), The Central Election Administration. October 8, 2016 Parliamentary Elections of Georgia. https://archiveresults.cec.gov.ge/results/20161008/index.html

Results (2020), The Central Election Administration. October 31, 2020 Parliamentary Elections of Georgia. https://results.cec.gov.ge/#/en-us

RIKER, W. H. and ORDESHOOK, P.C. (1968), ‘A theory of the calculus of voting’, American Political Science Review, 62 (1), pp. 25–42. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000305540011562X

Saakashvili Declared Winner of Georgia’s Presidential Election (2004), https://www.voanews.com/archive/saakashvili-declared-winner-georgias-presidential-election-2004-01-15

Saakashvili: Nagorno-Karabakh Sovereign Territory of Azerbaijan (2020), Georgia Today, http://georgiatoday.ge/news/22518/Saakashvili%3A-Nagorno-Karabakh-Sovereign-Territory-of-Azerbaijan

SOLIJONOV, A. (2016), Voter Turnout Trends around the World, International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance. https://www.idea.int/sites/default/files/publications/voter-turnout-trends-around-the-world.pdf

STOCKEMER, D. (2017), ‘What Affects Voter Turnout?’, Government and Opposition, 52 (4), pp. 698–722. https://doi.org/10.1017 /gov.2016.30

Summarizing Protocol (2008), The Central Election Commission of Georgia, Parliamentary Elections May 21, 2008. https://cesko.ge/res/old/other/8/8722.pdf

Summarizing Protocol (2012), The Central Election Commission of Georgia, Parliamentary Elections. https://cesko.ge

The Parliament of Georgia: Parliamentary Elections 1990, 28 October. http://www.parliament.ge/ge/

TULLOCK, G. (1967), Towards a Mathematics of Politics, University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor.

VAISHNAW, M. and GUY, J. (2018), Is Higher Turnout Bad for Incumbents, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. https://carnegieendowment.org/2018/05/07/is-higher-turnout-bad-for-incumbents -pub-76238

Voter Turnout (2008), The Election Administration of Georgia, May 21, 2008 Parliamentary Elections of Georgia. https://cesko.ge/ge/archevnebi/2008/parlamentis-archevnebi-19-ge (in Georgian)

Voter Turnout (2012), The Election Administration of Georgia, October 1, 2012 Parliamentary Elections of Georgia. https://cesko.ge/ge/archevnebi/2012/parlamentis-archevnebi-2012-136-ge/aqtivoba-2012 (in Georgian)

Voter Turnout (2016), The Election Administration of Georgia, October 8, 2016 Parliamentary Elections of Georgia. https://cesko.ge/en/archevnebi/2016/saqartvelos-parlamentis-archevnebi-2016/amomrchevelta-aqtivoba

Voter Turnout (2020), The Election Administration of Georgia, October 31, 2020 Parliamentary Elections of Georgia. https://cesko.ge/en/archevnebi/2020/october-31-2020-parliamentary-elections-of-georgia/aqtivoba