Abstract. As several Western Balkans countries aspire to become members of the European Union (EU) in the (near) future, it is interesting to explore to what extent EU territorial trends are adopted in both the official national regulations and spatial planning practice. To do so, we: 1) screen EU territorial policies to elucidate the trends and principles of territorial development, 2) analyse the contents of spatial plans in Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, and 3) compare the practical application of the principles such as decentralisation, diffusion of power, subsidiarity, multi-actorship, synergy, transparency, citizen participation, coordinated action (among various disciplinary bodies), and holistic strategies. The findings show the ineffectiveness of declaratively adopted EU territorial trends against place-based territorial policy approaches.

Key words: territorial development, spatial planning, vertical coordination, multi-sectorial cooperation, multidisciplinary cooperation, Western Balkans.

Despite the number of different programmes and strategies triggering the episodes of Europeanisation of spatial planning among EU Member States (Adams et al., 2011; Stead and Cotella, 2011; Cotella, 2020; ESPON, 2018), bodies at the supranational level, e.g., the European Commission (EC), have never been officially recognised as the competence holders to develop EU territorial policies. Consequently, Member States are not obliged to follow EU-defined principles and priorities of territorial development. Nevertheless, since the need for coordinated development was acknowledged as one of the highest priorities, many EU Member States have adopted the crucial EU territorial policies despite their non-binding nature (ESPON, 2013, 2017).

The extent to which the adopted policies are effective in practice is related to the notable duality between the ‘conformance’ and ‘performance’ (Faludi, 2000; Waterhout, 2008; Janin Rivolin, 2008; Stead, 2012). Many EU Member States have adopted fundamental principles – sustainable development, territorial cohesion, strategic planning, good governance – in their national spatial plans and strategies. However, the effectiveness of EU territorial policies depends on the way how European input has been translated and adapted into national settings (Purkarthofer, 2019). As expected, the implementation of EU principles is far more demanding than their pure inclusion in national documents.

Western Balkan (WB) countries[1] seem to be more complicated in this regard (Belloni, 2016; Börzel and Grimm, 2018; Džankić, 2019). The WB is not officially obliged to fulfil any EU standards. However, as most WB countries are candidates for EU membership,[2] a relevant approach would be to follow EU guidelines and prepare relevant pre-accession chapters timely. Though WB states are persistent in undertaking steps towards EU integration (Elbasani, 2013; Vučković and Djordjević, 2019), the issues of territorial development and spatial planning are not well addressed in EU enlargement policies, as the first set of documents with which one should comply. As a result, each WB state interprets EU policies and programmes focused on the territorial dimension and adapts these to national developmental conditions (Cotella, 2018; Cotella and Berisha, 2016; Trkulja et al., 2012).

With this in mind, we assume that spatial planning in WB is shaped by EU trends in territorial development. To explore the extent of domestic acknowledgement of EU territorial policies, we intend to determine what has been addressed, i.e., the topics and scales of cooperation, and how the recognised trends are proposed to be applied (e.g., through different forms of vertical or horizontal cooperation). In other words, we aim to identify the principles inscribed in both the substantial and procedural aspects of territorial development as given in the spatial planning regulatory frameworks of Serbia and of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Although once part of the federal state of Yugoslavia, these countries nowadays differ in terms of their 1) accession status to the EU (Serbia is a candidate country, whilst Bosnia and Herzegovina is considered a potential candidate), hence depicting different stages of compliance to EU territorial policies, and 2) territorial organisations, which also affect different administrative bodies competent for spatial planning. Informed by the overview of the main trends and principles covered in the domestic spatial planning documents, the paper further examines the similarities and differences in translating EU trends into spatial planning practice in the selected WB countries. Ultimately, this will elucidate the dichotomy of the ‘conformance’ to EU standards and their actual implementation.

The paper is structured as follows. After introductory remarks, we identify the trends and principles related to the procedural aspect of territorial development in the crucial EU territorial policies prepared to date. Followed by an insight into the methodological approach applied, we provide an overview of the leading spatial planning documents of Serbia and of Bosnia and Herzegovina. More precisely, we focus on national spatial development plans as the core elements inscribed in the planning traditions of the mentioned countries, which thus represent the key instruments of their national spatial planning systems. The comparative analysis helps elucidate to what extent the mentioned cases apply EU principles related to the procedural aspect of territorial development – revolving around vertical coordination, multi-sectorial cooperation, and multidisciplinary cooperation – in their planning practice. Finally, the findings on the relationship between EU trends and their national performance are observed through the lens of the broader socio-political conditions of WB.

To elucidate the procedural aspect of territorial development in the EU spatial planning narrative, i.e., to identify different forms of vertical coordination and horizontal cooperation, we provide a brief chronological overview of EU territorial policies. The cross-cutting issues and principles of crucial EU territorial policy documents are given in Table 1.

| Documents | Cross-cutting issues and principles |

|---|---|

| Territorial Agenda 2030(EU Ministers, 2020) |

|

| Urban Agenda for the EU (EC, 2016) |

|

| Integrated sustainable urban development – Cohesion policy 2014–2020 (EC, 2014) |

|

| Territorial Agenda of the European Union 2020 (EU Ministers, 2011) |

|

| Urban Dimension of Cohesion Policy (EP, 2009) |

|

| Green Paper on Territorial Cohesion (CEC, 2008) |

|

| Leipzig Charter on Sustainable European Cities (EU Ministers, 2007) |

|

| European Spatial Development Perspective (CSD, 1999) |

|

Source: own work.

Evidently, territorial governance is one of the umbrella concepts that spans over different principles introduced in the documents covered in Table 1. The concept comprises two notions: multi-level polities and governance, closely connected to understanding the governmental hierarchy, as well as ‘functional spill-over,’ respectively (Böhme et al., 2015; Bache and Flinders, 2004; Perić, 2019). Regarding the multi-level governmental hierarchy, the focus is on formal authority being spread from the nation states to both supranational institutions and sub-national authorities. The aspect of governance focuses on single-purpose functional jurisdictions, i.e., specialised, task-specific organisations (governmental and non-governmental) which criss-cross judicial boundaries (Piattoni, 2016). In the domain of EU studies, such a transformation refers to the integration process, emphasising not only the role of Member States and the EU, but explaining how the system actually works (Faludi, 2012).

A closer consideration into documents reveals three tendencies towards better territorial governance: addressing jurisdictions at different territorial scales (from neighbourhoods to macro-regions); the involvement of relevant stakeholders (private sector, local economy, public officials, civil society, and citizens) to strengthen democracy through increased participation; and cross-sectorial horizontal cooperation (between the bodies in charge of different aspects, e.g., transport, environment, demography, and economy, as related to spatial and territorial development). Based on this, we have recognised three broad categories related to the procedural aspect of territorial development: 1) vertical coordination (among administrative bodies at various territorial scales), 2) multi-sectorial cooperation (between public, private, and civil sectors), and 3) multidisciplinary cooperation (among various sectoral bodies in charge of preparing policies with spatial/territorial effects). In the empirical part of the paper, the principles associated with the mentioned categories will be firstly identified in national spatial planning documents and their implementation in the spatial planning practice shall be further discussed.

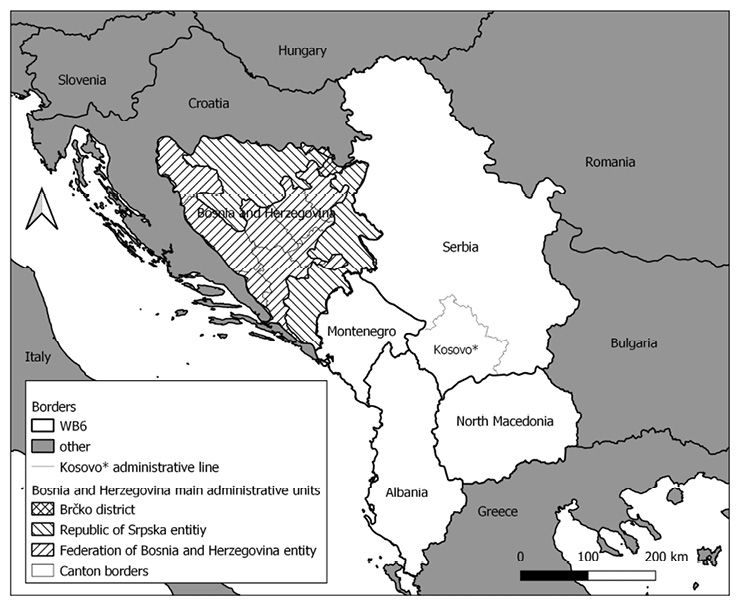

Separated by the Drina River, Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina are two neighbouring WB countries with many cultural similarities and a common historical background as they were part of the same state over the centuries. Notably, spatial planning systems in both countries have been inherited from former Yugoslavia, a decentralised federal state composed of six republics, each with their own planning laws and spatial plans. The preparation of the first Spatial Plan of the Republic of Serbia started in 1968 and it was only adopted in 1996 with a timeframe of until 2010, while the Spatial Plan of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina was adopted in 1981 setting 2000 as the end of the timeframe.[3] After the fragmentation of Yugoslavia after 1991 and civil wars in Croatia and in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the latter faced a serious reorganisation of its government and territorial structure, seen in two entities (the Republic of Srpska and the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina), and one district (Brčko district),[4] as depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. The spatial organisation of Bosnia and Herzegovina within the WB6

Source: own work.

Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina differ in terms of their territorial and administrative structures, a fact which also affects the levels of government competent for spatial planning. In Serbia, there are five territorial and administrative layers: republic, province (pokrajina), district (okrug), local self-government unit (jedinica lokalne samouprave), and local commune (mesna zajednica). Administrative and operational functions of districts and local communes are very weak, while the republic, an autonomous province, and municipalities have institutions responsible for spatial planning. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, the administrative structure comprises the state, two entities (with the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina divided into ten cantons), one district, local self-government units (cities and municipalities), and, finally, local communes. Spatial planning institutions and responsibilities appear at all levels except the state and the local commune levels.

As the highest administrative tiers responsible for spatial planning are republic and entities (in Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, respectively), the paper focuses on a comparative analysis of the three cases – the Republic of Serbia, the Republic of Srpska, and the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. This proves particularly interesting given that territorial organisation and spatial policies in the Republic of Srpska, although being part of Bosnia and Herzegovina, are more like those in Serbia (Bijelić and Djordjević, 2018). For the empirical analysis, we have selected the crucial national/entity spatial planning documents – two currently (as of April 2021) valid spatial plans and one which attained the final phase of its adoption: Spatial Plan of the Republic of Serbia 2010–2020 (OG RS 88/2010), Spatial Plan of the Republic of Srpska 2015–2025 (OG RoS 15/2015), and draft Spatial Plan of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina 2008–2028 (FMSO, 2013).

To collect the relevant data, we relied on personal professional experience,[5] used the insight into the main primary sources (the national/entity spatial plans of Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina), additional primary sources (e.g., legal documents in relevant domains, and supplementary regulation), as well as secondary sources that place the data from the primary sources into specific contexts.

The documentary analysis, as the primary method used in the research, will follow a two-step process. Firstly, to analyse conformance with EU trends in the selected WB countries, we shall analyse selected spatial plans to identify the substantial aspect of territorial development, i.e., topical coverage (e.g., sustainable development, territorial cohesion, and nature of land-use policy), and the scale of territorial cooperation (e.g., from local to supranational). We shall also identify the proposed procedures for implementing the mentioned topics and classify them under previously identified three categories: 1) vertical coordination, 2) multi-sectorial cooperation, and 3) multidisciplinary cooperation. More precisely, we shall address the following principles: 1) decentralisation, diffusion of power, and subsidiarity; 2) multi-actorship, synergy, transparency, and citizen participation; and 3) coordinated action (among various disciplinary bodies) and holistic strategies (including different topical domains). Thus, we shall identify the extent to which EU territorial trends inform the domestic substantial and procedural aspects of territorial development.

Secondly, we shall analyse the performance of EU trends in the selected WB countries using additional primary sources (relevant legal and regulatory frameworks of the selected WB countries) and secondary sources (academic literature by domestic scholars) that interpret and, thus, offer a better understanding of the domestic spatial planning contexts. To illuminate the real implementation of the declared EU territorial trends, we shall particularly focus on the procedural aspect of territorial development, comprising the categories of: 1) vertical coordination, 2) multi-sectorial cooperation, and 3) multidisciplinary cooperation. The overview of the associated principles is done through a comparative analysis of the spatial planning practices of Serbia and of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

By studying the aims and visions as presented in the spatial plans in the Republic of Serbia, the Republic of Srpska, and the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, we address the substantial and procedural aspects of territorial development as proposed in core national policies. More precisely, we examine whether the principles under the categories of topical coverage and the scale of territorial cooperation (substantial aspect), as well as under vertical coordination, multi-sectorial cooperation and multidisciplinary cooperation (procedural aspect) are interpreted in the plans and if so, to what extent. Table 2 summarises the adoption of the main EU trends in national spatial plans.

| Aspect | Categories / principles | Republic of Serbia |

Republic of Srpska |

Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

S U B S T A N T I A L |

Topical coverage | |||

| sustainable development | • | • | o | |

| territorial cohesion | • | • | o | |

| nature of land-use policy | • | • | o | |

| Scale of territorial cooperation | ||||

| cross-border | • | • | o | |

| interregional | • | o | o | |

| supranational | • | o | o | |

|

P R O C E D U R A L |

Vertical coordination | |||

| decentralisation | • | o | o | |

| diffusion of power | • | o | o | |

| subsidiarity | • | o | o | |

| Multi-sectorial cooperation | ||||

| multi-actorship | • | • | o | |

| synergy | o | o | o | |

| transparency | • | o | o | |

| citizen participation | • | o | o | |

| Multidisciplinary cooperation | ||||

| coordinated action | o | o | o | |

| holistic strategies | o | o | o | |

• addressed o partially addressed o not addressed

Source: own work.

The currently (as of April 2021) valid Spatial Plan of the Republic of Serbia addresses the period between 2010 and 2020 (OG RS 88/2010).[6] As the second spatial plan prepared for the republic stratum,[7] it is based mainly on the preceding plan (OG RS 13/1996) and its planning proposals. However, the new plan applies an updated methodology: it provides strategic guidelines binding for elaboration in lower-tier spatial planning documents. The Spatial Plan of the Republic of Serbia 2010–2020 was prepared in two years, involving a comprehensive team of experts from various sectors, several thematic round tables, and public hearings on its draft plan. It contains the vision, five goals, and many sectoral objectives.

The overarching idea of the plan supports the principle of sustainable development grouped into environmental, social, and economic chapters. According to EU recommendations, territorial cohesion should be achieved through balanced regional socio-economic development based on efficient regional organisation and coordinated regional policy. An innovative cross-sectoral chapter on transboundary territorial cooperation recognises cross-border, interregional, and transnational cooperation. Land-use policy is considered a task for lower territorial units, while the national spatial plan addresses only four core land types (agricultural, forest, water, and construction areas). The proposed land-use policy is of a strategic nature: it offers the main directions of formulating the future territorial policy and reserves the land for a specific use of national importance, e.g., infrastructure corridors, natural and cultural protected areas, water accumulations, mining areas, etc.

The plan explicitly lists the principles of decentralisation, division of power, and subsidiarity as prerequisites for more efficient spatial planning decision-making. However, the region is considered only a territorial stratum and not an administrative unit. In addition, the plan does not include mechanisms which would indicate how to achieve active participation of lower jurisdictional levels in solving complex spatial problems.

The basic principles of multi-sectorial cooperation are given in the plan as follows: 1) active implementation of the spatial development policy by public participation, through the permanent education of citizens and administration, 2) the development of instruments for directing the activities of spatial planning, and 3) the development of service functions (agencies or non-profit organisations) at the municipal and/or city levels to consolidate all spatial development actors and create synergy. In terms of institutional responsibility, the plan requires the development of legally stipulated, locally conditioned informal forms of participation in the decision-making process (involving citizens and their associations, spatial development actors, associations, and political parties). This should resolve the conflict concerning the public-private relationship and generate further support for implementing policies, strategies, and plans collaboratively.

The plan proposes a multidisciplinary approach by recognising diverse areas of spatial development, yet through the lens of separate topics and without attending to cumulative spatial effects of many sectoral domains. For example, the proposal of a transport infrastructure corridor lacks an acknowledgement of nature protection: the Požega–Užice motorway should pass between two national parks, Mokra Gora and Zlatibor. Furthermore, the economy is observed apart from the territory and settlements. Demography has continued to be studied through extensive analysis without enough impact on planning proposals. The development of social services lacks innovative approaches towards sustainable development. GIS systems based on spatial development indicators are a tangible tool for coordinated action among different disciplines. They enable an evidence-based approach with the monitoring of trends and promote a better quality of planning proposals in the forthcoming plans.[8]

After the first spatial plan for Republic of Srpska was adopted in 1996, and the second one in 2008, the currently (as of April 2021) valid plan was amended in 2015 for the timeframe until 2025. In terms of its contents, the Spatial Plan of the Republic of Srpska 2015–2025 (OG RoS 15/2015) has many similarities with the Spatial Plan of the Republic of Serbia 2010–2020,[9] mainly seen in its structure (vision, five goals, and many sectoral objectives) and topical coverage. In short, the plan focuses on the pragmatic implementation of objectives and goals towards the overall vision.

The principle of sustainable development is considered the backbone for structuring spatially relevant activities around three pillars – the economy, environment, and social development. The concept of territorial cohesion is viewed holistically: cohesion is perceived as a balance between economic, social and territorial factors that can jointly act as a tool against a post-socialist market influencing diverse social, territorial, and cultural resources. The translation of the Europe-scale forms of territorial cooperation is relatively weak: e.g., the supranational territorial cooperation is presumed only to happen as cross-border cooperation. The land-use policy is pragmatic in its nature: the key instruments in this regard include urban regulation plans, plans for special-use areas, and municipal and city plans for land use outside the urban settlement area.

As the Republic of Srpska lacks an intermediate governmental or statistical level, vertical coordination is not the focus, suggesting the main channel of communication between the national and local levels in a top-down approach. Decentralisation is not an issue, as the plan lacks the operationalisation tools for empowering local governments to address the spatial problems affecting their administrative areas.

However, the plan proposes a relatively comprehensive horizontal cooperation to be pursued through different networks: 1) cooperation between diverse institutions (Chamber of Commerce, public enterprises, agencies, institutes, offices and operators for infrastructure, social services, statistical office, and cadastre), 2) joint activities among the entity ministries, and 3) cooperation among the spatial planning institutions in the other entity (Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina) and neighbouring countries as well. In addition, the final chapter of the spatial plan refers basically to the implementation through the spatial plans of smaller territorial units like special-use areas and municipalities.

Multidisciplinary cooperation among various institutions and organisations aimed at concerted actions and holistic visions is superficially addressed in the spatial plan. Social development strategy needs more operationalisation mechanisms, while the conventional economic development strategy lacks attention to other sectors. Infrastructure as the backbone of spatial development is not focussed sufficiently to reduce existing spatial conflicts. Nevertheless, and similarly to the spatial plan of Serbia, the indicators are defined as a tool for more accessible data collection and an improvement of spatial development policies towards fostering overall development.

The draft Spatial Plan of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina 2008–2028 (FMSO, 2013) is quite different from the spatial plans of Serbia or of the Republic of Srpska, foremost due to a specific administrative set-up of the entity. Namely, the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina is composed of ten cantons, each with an independent legal system. Therefore, in addition to the law on spatial planning at the entity level (OJ FBiH 45/2010), there are ten laws valid for every canton. The Federation’s spatial plan has not been adopted yet (as of April 2021), although the draft version was finalised in 2012 and a part of the enaction procedure was undertaken until 2014, though not concluded. Since then, the approval of the draft spatial plan has been delayed. The planning approach applied in the draft plan is conventional: the regulatory dimension of spatial planning based on steering the development and addressing the present problems is emphasised compared to long-term spatial visioning.

Regarding topical coverage, the plan acknowledges neither the concept of sustainable development nor territorial cohesion to a greater extent. Instead, such topics as population, land policy and infrastructure are highlighted, although not coherently. Land-use policy is not the subject of this plan. As for macro-regional territorial cooperation, the cooperation across various geographical and jurisdictional levels (cross-border, interregional, and transnational) is not considered in the plan.

Vertical coordination is not an element of the entity’s spatial plan, as the intermediate administrative and territorial level – canton – has a vital role in spatial planning decision-making. Notably, in the absence of entity strategic spatial plan, the adopted cantonal plans provide the direction for the development at lower levels.[10]

As the chapter on implementation is missing, the elements of multi-actor cooperation are not envisioned in the plan. The closest step towards implementation and, hence, proposed collaborative approaches promoting the inclusion of different sectors, tackles planning proposals and plans for smaller territorial units within the sectoral chapters of the spatial plan.

Similarly, the multidisciplinary approach is omitted. Extensive population analysis is not connected to or made usable for the domains of land policy or infrastructure. The social and economic policy is not well incorporated in the plan, whilst the environmental aspect of development is inferior. The infrastructural network does not fit the territory to enable its development but rather provides spatial-transport conflicts. Finally, the draft plan defines no spatial development indicators.

The above analysis confirms the initial hypothesis that the spatial plans in Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina consider EU territorial development trends yet to varying extents: Serbia seems to pursue a far more proactive approach than the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. However, the question remains whether the nature of adopting the trends is declarative or real. In the following paragraphs we shall place the EU spatial planning narrative into the spatial planning contexts of Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. More precisely, we are going to compare the principles inscribed in the procedural aspect of territorial development, i.e., these associated with the following categories: 1) vertical coordination, 2), multi-sectorial cooperation, and 3) multidisciplinary cooperation. In doing so, we will elucidate: the coordination between administrative bodies at different territorial strata; the involvement of stakeholders other than public authorities in the spatial planning decision-making; and the organisation of spatially relevant activities among sectoral departments.

The principles of decentralisation and subsidiarity are only recognised in Serbian spatial documents. However, this is in discrepancy with the actual spatial organisation in Serbia, which operates in a centralised manner, with the national (republic) level in charge of spatial planning, whilst the regional level (districts) is considered merely a territorial and not an administrative unit. More precisely, regional spatial plans in Serbia refer to groups of districts with very weak institutions, except for the autonomous province of Vojvodina and the administrative territory of the City of Belgrade. Therefore, the national administration in charge of spatial planning takes the leading role in creating regional plans (Maruna et al., 2018). The attempt to pursue the ‘shift from government to governance’ has been recognised in the crucial Serbian laws relevant for spatial development. Namely, the Act on Local Self-government Units (OG RS 47/2018) identifies local self-governments as being responsible for preparing municipal and city spatial plans. However, the lack of professional capacity makes cooperation with national-level bodies weak (Zeković and Vujošević, 2018). Similarly, the Act on Planning System of the Republic of Serbia (OG RS 30/2018) has introduced a bottom-up approach as the necessary type of cooperation among jurisdictional levels and, thus, established a framework for territorial governance. Nevertheless, such an approach has not yet taken root in practice (Maruna et al., 2018).

The spatial plan of the Republic of Srpska does not address coordination or dialogue among administrative units, which is reflected in the jurisdictional organisation of the entity: the regional level between the entity and municipalities is entirely missing. Consequently, the national government subordinates local authorities in the process of spatial planning decision-making (Bijelić and Đorđević, 2018).

The draft plan of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina does not explicitly prescribe the need for power diffusion. However, due to the specific territorial organisation of the entity, the principle of decentralisation is applied in an advanced manner compared to Serbia and the Republic of Srpska. Notably, the regional level units – cantons – are essential for spatial planning as cantonal authorities are responsible for preparing cantonal spatial plans. Due to the lack of the official federation spatial plan, cantons play a key role in steering spatial development at lower administrative and territorial strata (Jusić, 2014).

What is typical for all the cases is the inferior position of local administration in planning and decision-making. The top-down coordination – from the national/entity towards the local level in Serbia and the Republic of Srpska, respectively, and from the cantonal to the municipality level in the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina – prevail over the bottom-up approach (Zeković and Vujošević, 2018; Bijelić and Đorđević, 2018; Bojičić-Dželilović, 2011; Maruna et al., 2018). The reason behind such a discrepancy between the norms proposed in the plans and spatial planning reality is the complexity inscribed in the coordinative effort – an acknowledgement of data from the local plans, their synthesis, and adaptation for use at the regional and national levels require various resources, mainly time and expert skills. Hence, moving beyond the general narrative on a bottom-up approach means establishing a mid-governance level with competence in spatial planning. Ultimately, this enables the introduction of a regulatory framework that promotes a new planning paradigm focused on territorial governance, thus dismissing the firmly rooted tradition of government, i.e., a top-down approach.

All the cases (though to various extents) indicate the public sector as the most active actor, whilst the private and non-governmental sectors’ participation is supported declaratively in documents, yet rare in reality. The spatial plans recognise the need to bridge that gap, however, clear and transparent mechanisms to achieve multi-actor efforts are missing (Bijelić and Đorđević, 2018; Jusić, 2014). Poor public response results from the complex nature of spatial plans and excessive use of technical jargon, finally disabling citizens and other stakeholders to grasp the main ideas as presented in plans.

In comparison to both entities of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia seems to make a shift in this regard, as its spatial plan instructs the promotion of local initiatives (educational, and social and cultural services and activities) adjusted to the needs and interests of the local population. The document also recommends introducing incentive measures for the active involvement of citizens and civil society organisations in planning and creating partnerships between local authorities and civil society. Such efforts have been formally supported by the Act on Planning and Construction (OG RS 145/2014), which introduced the mechanisms of early public inspection and public inspection, enabling the public to have an insight and offer comments for a draft and the final plan, respectively. The reality is significantly different: participation only serves to provide legitimacy for the planning procedure, planners usually neglect the citizens’ input, which, eventually, results in mistrust among the general public to institutions (Čukić and Perić, 2019; Perić, 2020a, 2020b). Notably, lacking the mechanisms for effective involvement of stakeholders other than governmental institutions, public support to decision-making becomes more declarative. Therefore, to boost the proper participatory process, the first step is to make plans user-friendly so that citizens and any interested party can understand the visions proposed in a plan. The public reaction will then logically follow. Also, the previously mentioned data processing based on spatial development indicators can be done by non-governmental organisations or private consultancies, not only the public sector.

An integrated, comprehensive and multidisciplinary approach to sustainable spatial development is mostly neglected in the analysed spatial plans. In the federation’s draft plan, multidisciplinary cooperation is rudimentary and it is not applied in practice. In Serbia and the Republic of Srpska, while they implement proposals from the plan, the integration of different sectors does not occur mainly due to a considerable complexity of data collection and its analysis when coming from more than one institution (Bijelić and Đorđević, 2018). For example, the Serbian spatial plan proposes tourist routes in central Serbia near the cultural heritage areas. However, the implementation programme[11] is highly fragmented as it lacks a coordinated timeframe for execution, involvement of interdisciplinary agencies, and joint financial sources. Such elements became part of the methodological procedure of strategic planning introduced by the Act on Planning System of the Republic of Serbia (OG RS 30/2018), binding for strategic spatial plans.[12]

In addition to a pragmatic perspective on collaborative activities between various disciplines, the holistic and comprehensive approach can also be seen at a rather abstract level. More precisely, an insight into the topical coverage of three spatial plans elucidates a weak to moderate relationship between the domains of spatial development and other sectoral policies and their spatial effects (demography, social development, environment, economy, and infrastructure). In contrast, the utmost impact of multidisciplinary cooperation is a balanced representation of sectors and topics, as is the attending to the spatial effects of sectoral policies.

The previous overview of the planning practices of the selected WB countries indicates poor implementation of the principles that promote a more coordinated approach to territorial development, as summarised in Table 3.

| Aspect | Categories /principles | Republic of Serbia | Republic of Srpska | Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

P R O C E D U R A L |

Vertical coordination | |||

| decentralisation | o | o | • | |

| diffusion of power | o | o | • | |

| subsidiarity | o | o | • | |

| Multi-sectorial cooperation | ||||

| multi-actorship | o | o | o | |

| synergy | o | o | o | |

| transparency | o | o | o | |

| citizen participation | o | o | o | |

| Multidisciplinary cooperation | ||||

| coordinated action | o | o | o | |

| holistic strategies | o | o | o | |

• applied o partially applied o not applied

Source: own work.

In summary, we have confirmed the initial hypothesis that EU territorial policy trends are declaratively addressed in the key spatial development documents of Serbia and of Bosnia and Herzegovina, but poorly applied in planning practice. However, the overview indicates an interesting case of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Although the draft entity plan does not acknowledge the crucial principles of EU territorial development, it does not prevent the entity from applying its spatial development policy efficiently compared to both Serbia and the Republic of Srpska. Some observations on the reasons behind such a situation follow in the conclusion.

The examination of the territorial development principles in both the official regulations and planning practice of the selected WB states has showed the discrepancy between the Europeanised narrative in the documents on the one hand, and its weak implementation on the other. As prescribed by EU policies, the crucial idea inscribed in the procedural aspect of territorial development is cooperation – between different jurisdictional strata, multiple stakeholders, and experts. The first is, however, tightly related to the territorial organisation of a state. This is the key to understanding why intense vertical and horizontal cooperation cannot flourish easily in Serbia, which inherited the centralised system from the former Yugoslavia, or in the Republic of Srpska, which copied its administrative organisation from Serbia. However, the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina wisely used the opportunity to transform its territorial-administrative system after the break with the rules of Yugoslav heritage in 1995. Even without acknowledging the principle of vertical coordination in the draft spatial plan, the federal organisation of the entity genuinely contributes to implementing some European territorial governance trends.

The relationship between the declarative adoption of EU trends and the extent of their actual implementation should also be viewed through the lens of both internal and external tensions. The former result from the lack of a democratic political culture and independent institutions, and a dominance of the authoritarian regimes in both Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina (Bojičić-Dželilović, 2011; Perić, 2020a). Within such political systems, cooperative spatial planning decision-making efforts are considered a threat, not the desired type of social action.

External pressures arise as WB countries are not (yet) EU Member States, thus allowing other international factors to play a decisive role when entering domestic actor-networks. For example, the Republic of Srpska is highly politically influenced by the Republic of Serbia, in addition to the previously mentioned influence of Serbian planning experts and their continuous consultancy in addressing the spatial problems of the Republic of Srpska. The Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina has another role model for its territorial organisation, again outside the EU: Switzerland with its cantonal structure. Finally, spatial development in the entire Balkan region is interesting to many foreign non-European players – from China investing in the Balkan route of the Belt and Road Initiative, to Russia, which has been financing the railway development between Serbia and Montenegro, Turkey as a sponsor of the railway line between Sarajevo and Belgrade, and American consortiums in support of a road line between Niš (Serbia) and Pristina (Kosovo*), and further towards Tirana and Durrës, in Albania (Bijelić and Djordjević, 2018; Perić and Niedermaier, 2019; Miletić, 2020). Such international stakeholders demand strong national leadership as the key partner for executing the mentioned transboundary initiatives. Consequently, the decentralised governance approach and multidisciplinary planning are neglected as they are seen as hindrances rather than facilitators of development.

Finally, when drawing lessons from Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina for other WB countries, we can highlight two instruments: 1) the cantonal spatial plans of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina as the main instruments of spatial development, and 2) advanced mechanisms for multi-sectorial cooperation as prescribed in the Serbian spatial plan. As for the former, although cantonal plans hinder the process of adopting the entity’s spatial plan, i.e., cantonal plans as strategic documents cover some elements of the entity plan, cantons as mid-territorial scale administrative units with their effective spatial instruments have proven to be a useful link in connecting the federal/national level with the local one. Regarding the latter, the tools for various stakeholders to express their conflicting interests and enable consensus-building are designed to promote social action. Nevertheless, as the analysis has showed, to strengthen cooperation across administrative and institutional boundaries and engage different actors, as according to EU trends, it is necessary for the actors at all jurisdictional strata and all the sectors to actively participate in territorial development. Such an endeavour, however, demands raising the collective awareness of the benefits of cooperative decision-making on the one hand, and a shift of socio-spatial settings from proto-democracy, on the other. The fulfilment of both conditions is part of a long-term transitional process.

ADAMS, N., COTELLA, G. and NUNES, R. (eds.) (2011), Territorial Development, Cohesion and Spatial Planning: knowledge and policy development in an enlarged EU, 46, London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203842973

BACHE, I. and FLINDERS, M. V. (eds.) (2004), Multi-level Governance, Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/0199259259.001.0001

BELLONI, R. (2016), ‘The European Union Blowback? Euroscepticism and its Consequences in the Western Balkans’, Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding, 10 (4), pp. 530–547. https://doi.org/10.1080/17502977.2016.1211387

BIJELIĆ, B. and ĐORĐEVIĆ, D. (2018), ‘Non-compliance of spatial plans of the highest rank in Bosnia and Herzegovina’, Collection of the Papers, LXVI-1, pp. 89–97. https://doi.org/10.5937/zrgfub1866089B

BOJIČIĆ-DŽELILOVIĆ, V. (2011), Decentralization and Regionalization in Bosnia- Herzegovina: Issues and Challenges. Research on South East Europe, London: London School of Economics.

BÖHME, K., ZILLMER, S., TOPTSIDOU, M. and HOLSTEIN, F. (2015), Territorial Governance and Cohesion Policy: Study, Brussels: European Parliament, Policy Department B: Structural and Cohesion Policies.

BÖRZEL, T. A. and GRIMM, S. (2018), ‘Building Good (Enough) Governance in Postconflict Societies & Areas of Limited Statehood: The European Union & the Western Balkans’, Dædalus, 147 (1), pp. 116–127.

CEC (Commission of the European Communities) (2008), Green Paper on Territorial Cohesion: Turning Territorial Diversity into Strength, Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

COTELLA, G. (2018), ‘European Spatial Integration: The Western Balkans Discontinuity’, Annual Review of Territorial Governance in Albania, I, pp. 156–166.

COTELLA, G. (2020), ‘How Europe hits home? The impact of European Union policies on territorial governance and spatial planning’, Géocarrefour, 94 (3). https://doi.org/10.4000/geocarrefour.15648

COTELLA, G. and BERISHA, E. (2016), ‘Territorial Governance and Spatial Planning in the Western Balkans between Transition, European Integration and Path-Dependency’, Journal of European Social Research, 2, pp. 23–51.

CSD (Committee on Spatial Development) (1999), ESDP – European Spatial Development Perspective. Towards Balanced and Sustainable Development of the Territory of the European Union, Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

ČUKIĆ, I. and PERIĆ, A. (2019), ‘Transformation of the spatial planning approach in Serbia: towards strengthening the civil sector?’, [in:] SCHOLL, B., PERIĆ, A. and NIEDERMAIER, M. (eds.), Spatial and transport infrastructure development in Europe: example of the Orient/East-Med corridor, Hannover: Academy for Spatial Research and Planning (ARL), pp. 272–290.

DŽANKIĆ, J., KEIL, S. and KMEZIĆ, M. (2019), The Europeanisation of the Western Balkans. A Failure of EU Conditionality?, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91412-1

EC (European Commission) (2014), Integrated sustainable urban development – Cohesion policy 2014-2020, Brussels: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

EC (European Commission) (2016), Urban agenda for EU, Brussels: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

EC (European Commission) (2020), Enlargement. https://ec.europa.eu/environment/enlarg/candidates.htm [accessed on: 20.10.2021].

ELBASANI, A. (2013), European integration and transformation in the Western Balkans: Europeanization or business as usual?, London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203386064

ESPON (2013), ESPON TANGO: Territorial Approaches for New Governance, Final Report, Luxembourg: ESPON.

ESPON (2017), European Territorial Review. Territorial Cooperation for the Future of Europe, Luxembourg: ESPON.

ESPON (2018), COMPASS – Comparative Analysis of Territorial Governance and Spatial Planning Systems in Europe, Final Report, Luxembourg: ESPON.

EU MINISTERS (2007), Leipzig Charter on Sustainable European Cities, Agreed on the Occasion of the Informal Ministerial Meeting of Ministers responsible for Urban Development, 2 May, Germany.

EU MINISTERS (2011), Territorial Agenda of the European Union: Towards an inclusive, smart and sustainable Europe of diverse regions, Agreed on the Occasion of the Informal meeting of Ministers responsible for Spatial Planning and Territorial Development, 19 May, Hungary.

EU MINISTERS (2020), Territorial Agenda 2030: A future for all places, Agreed on the Occasion of the Informal meeting of Ministers responsible for Spatial Planning and Territorial Development and/or Territorial Cohesion, 1 December, Germany.

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT (2009), Urban Dimension of Cohesion Policy, Strasbourg: EP.

FALUDI, A. (2000), ‘The performance of spatial planning’, Planning Practice and Research, 15 (4), pp. 299–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/713691907

FALUDI, A. (2012), ‘Multi-Level (Territorial) Governance: Three Criticisms’, Planning Theory & Practice, 13 (2), pp. 197–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2012.677578

FMSO (Federal Ministry of Spatial Organisation) (2013), Spatial Plan of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina 2008–2028 (draft), Sarajevo: FMSO, http://www.fmpu.gov.ba/prostorni-plan-fbih [accessed on: 01.11.2020].

JANIN RIVOLIN, U. (2008), ‘Conforming and performing planning systems in Europe’, Planning Practice and Research, 23 (2), pp. 167–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697450802327081

JUSIĆ, M. (2014), Local communes in Bosnia and Herzegovina – challenges and perspectives of institutional development (in Bosnian), Sarajevo: Analitika – Centar za društvena istraživanja.

MARUNA, M., ČOLIĆ, R. and MILOVANOVIĆ RODIĆ, D. (2018), ‘A new regulatory framework as both an incentive and constraint to urban governance in Serbia’, [in:] BOLAY, J.-C., MARIČIĆ, T. and ZEKOVIĆ, S. (eds.), A Support to Urban Development Process, Lausanne/Belgrade: CODEV EPFL/IAUS, pp. 80–108.

MILETIĆ, M. (2020), ‘Why is the highway to Durres (not) cost effective for us?’, Istinomer, 4 October. https://www.istinomer.rs/analize/zasto-nam-se-ne-isplati-auto-put-do-draca/ [accessed on: 21.10.2021].

OG RoS 15/2015 (Official Gazette of the Republic of Srpska 15/2015). Spatial Plan of the Republic of Srpska 2010-2025 – amendments.

OG RS 13/1996 (Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia 13/1996). Act on Spatial Plan of the Republic of Serbia until 2010.

OG RS 88/2010 (Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia 88/2010). Act on Spatial Plan of the Republic of Serbia 2010–2020.

OG RS 145/2014 (Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia 145/14, 83/18, 31/19, 37/19, 9/20). Act on Planning and Construction.

OG RS 30/2018 (Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia). Act on Planning System of the Republic of Serbia.

OG RS 47/2018 (Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia). Act on Local Self-government Units.

OG RS 47/2019 (Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia). Strategy of Sustainable Urban Development of the Republic of Serbia until 2030.

OJ FBiH 45/2010 (Official Journal of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina 2/06, 72/07, 32/08, 4/10, 13/10, 45/10). Act on Spatial Planning and Land Use for Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

PERIĆ, A. (2019), ‘Multi-Level Governance as a Tool for Territorial Integration in Europe: Example of the Orient/East-Med Corridor’, [in:] SCHOLL, B, PERIĆ, A. and NIEDERMAIER, M. (eds.), Spatial and transport infrastructure development in Europe: example of the Orient/East-Med corridor, Hannover: Academy for Spatial Research and Planning (ARL), pp. 91–105.

PERIĆ, A. (2020a), ‘Public engagement under authoritarian entrepreneurialism: the Belgrade Waterfront project’, Urban Research and Practice, 13 (2), pp. 213–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/17535069.2019.1670469

PERIĆ, A. (2020b), ‘Citizen Participation in Transitional Society: The Evolution of Participatory Planning in Serbia’, [in:] LAURIA, M. and SCHIVELY SLOTTERBACK, C. (eds.), Learning from Arnstein’s Ladder: From Citizen Participation to Public Engagement, New York: Routledge Press, pp. 91–109. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429290091-10

PERIĆ, A. and NIEDERMAIER, M. (2019), ‘Orient/East-Med Corridor: Challenges and Potentials’, [in:] SCHOLL, B., PERIĆ, A. and NIEDERMAIER, M. (eds.), Spatial and transport infrastructure development in Europe: example of the Orient/East-Med corridor, Hannover: Academy for Spatial Research and Planning (ARL), pp. 35–70.

PIATTONI, S. (2016), ‘Exploring European Union Macro-regional Strategies through the Lens of Multilevel Governance’, [in:] GÄNZLE, S. and KERN, K. (eds.), A ‘macro-regional’ Europe in the making: theoretical approaches and empirical evidence, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 75–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-50972-7_4

PURKARTHOFER, E. (2019), ‘Investigating the partnership approach in the EU Urban Agenda from the perspective of soft planning’, European Planning Studies, 27 (1), pp. 86–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2018.1527294

STEAD, D. (2012), ‘Best Practices and Policy Transfer in Spatial Planning’, Planning Practice and Research, 27 (1), pp. 103–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2011.644084

STEAD, D. and COTELLA, G. (2011), ‘Differential Europe: Domestic actors and their role in shaping spatial planning systems’, disP-The Planning Review, 47 (186), pp. 13–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/02513625.2011.10557140

TRKULJA, S., TOŠIĆ, B. and ŽIVANOVIĆ, Z. (2012), ‘Serbian Spatial Planning among Styles of Spatial Planning in Europe’, European Planning Studies, 20 (10), pp. 1729–1746. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2012.713327

VUČKOVIĆ, V. and DJORDJEVIĆ, V. (2019), Balkanizing Europeanization: Fight against Corruption and Regional Relations in the Western Balkans, Berlin: Peter Lang. https://doi.org/10.3726/b15731

WATERHOUT, B. (2008), The Institutionalisation of European Spatial Planning (doctoral dissertation), Delft: Delft University Press/IOS Press.

ZEKOVIĆ, S. and VUJOŠEVIĆ, M. (2018), ‘Land construction and urban development policy in Serbia: impact of key contextual factors’, [in:] BOLAY, J.-C., MARIČIĆ, T. and ZEKOVIĆ, S. (eds.), A Support to Urban Development Process, Lausanne/Belgrade: CODEV EPFL/IAUS, pp. 28–56.