Abstract. Territories as relational geographical constructs are in constant formation and reformation, or rescaling, which results in spatial typologies of complex governance. The voting containers of a territory are merely one typology, often not matching the numerous functions within the other typologies. Under the assumption that voting containers are politically fixed, governance that adapts to the dynamics of territorial rescaling is required. This paper explores the relationship between territorial rescaling and polycentric governance in Albania. It concludes that polycentric governance can enable cooperation and efficiency throughout rescaling, assuming some conditions are in place for addressing the polycentricity gap.

Key words: polycentric governance, polycentricity, multilevel governance, territorial rescaling, territory, Albania.

Policy responses should be tailored to the territories[1] and should not be spatially blind. But as territories are in constant formation and reformation, with a myriad of purposes (Keating, 2013), the complexity of their governance increases. Governance limited within administrative boundaries appears to insufficiently address place diversity (Keating, 2014, 2013; Faludi, 2018, 2012; Hooghes and Marks, 2016, 2003, 2001; Walter, 2004; Agnew, 1994; Ostrom et al., 1961) because of the mismatch between government jurisdictions and proliferating, spatially overlaying territorial functions (ESPON, 2019; Behnke et al., 2019; Faludi, 2012; Baldersheim and Rose, 2010). Albania faces much of the same challenge. In 30 years, the government has undertaken reforms to decentralise power to promote territorial development and make the governance system more efficient and just. Yet the system is far from perfect and inequalities have been flourishing across territorial and societal strata, questioning the reforms and the quality of territorial governance (RDPA, 2018; Shutina et al., 2016; Toto et al., 2015; Toto, 2010).

The discourse on territorial development and regional policy in the European Union (EU) has emphasised since 1999[2] the need for multi-level governance and territorial polycentricity, in order to foster equity, competitiveness, and sustainability. To achieve them is a challenge that depends on institutional arrangements and on the stakeholders’ ability to continuously adapt to everchanging territorial constructs and to produce cohesive growth at any spatial scale. Decentralisation has often been described as the form of territorial rescaling, which together with territorial reforms shifts power between institutions and territorial levels for higher efficiency, but has also been criticised, at least in the case of CEE countries, for not contributing to lowering disparities (Loewen, 2018). Regionalisation, then, has played a role in the EU in restructuring territorial governance, leading to the regional policy discourse and new practices and forms of power sharing (ibid.) in a multi-level governance system. Therefore, multi-level governance has emerged as a means to govern through territorial scales and connect interests enabling territorial development and cohesion (Benz, 2019; Behnke et al., 2019; Hooghes and Marks, 2003, 2009, 2016). This ability to correct the failures of both, centralised and decentralised systems of governance, and the respective territorial constructs result from the multi-level configuration of institutional arrangements that are theoretically flexible compared to the voting containers in a territory. Such arrangements exhibit network and polycentric characteristics that may be “capable of striking a balance between centralised and fully decentralised or community-based governance” (Carlisle and Gruby, 2019, p. 928), while also mitigating the impacts of administrative and territorial reforms undertaken to satisfy electoral results and representations.

However, OECD (2016, 2011) has defined the presence of seven gaps that actors should overcome to achieve efficient multi-level governance and obtain territorial cohesion. The administrative gap – being a mismatch between political/functional boundaries and the policy gap – as fragmentation and miscoordination of polities could be overcome through cooperation. The other gaps (financial, capacity and information, and accountability and objective) interrelate with the first two, because conflicting territorial constructs and institutional designs cannot yield better resources, more knowledge, or cohesion and democracy. In this paper, we add and explore an eighth gap, that of polycentricity, which indicates the embeddedness of polycentric governance’s modus-operandi that is based on cooperation, into frequently changing territorial constructs.

The need to explore the polycentricity gap stems thus from the requirement for multi-level governance to connect territorial layers to governance and polities in a context of continuous territorial rescaling. Multi-level governance is proposed to solve issues of efficiency and cohesion, yet often being captured in territorial containers of power distribution. Early EU studies on cohesion identified territorial polycentricity as a spatial planning policy objective in Europe and a foundation for EU regional policy, aiming at sustainable development, regardless of the electoral containers. However, territorial polycentricity has yet to achieve its ambition (Rauhut, 2017; Waterhout et al., 2005; Davoudi, 2003) lacking even a commonly agreed measuring methodology (see ESPON, 2005; Meijers and Sandberg, 2008; Green, 2007; Brezzi and Veneri, 2015). Furthermore, territorial polycentricity as an objective that tackles territorial disparities while boosting competitiveness (CSD, 1999) has held true among countries, but has had limited empirical validity among regions[3] (Rauhut, 2017; Homsy and Warner, 2015; Brezzi and Veneri, 2015; Burger et al., 2014; Meijers and Sandberg, 2008) because it focuses on proving the morphology of development and the flows of functions in a territory without considering the governance arrangements (Finka and Kluvankova, 2015).

Despite that, a growing body of literature has explored polycentric governance under various disciplines and scholarships, particularly public administration and the commons (Carlisle and Gruby, 2019), since 1961 when V. Ostrom et al. conceived the concept in the frame of their discourse on metropolitan-area governance. In these studies, polycentric governance is attributed a number of theoretical and empirically observed advantages, such as risk adaptation and mitigation ability, recognition of scale diversity, higher economic efficiency compared to monocentric systems (Van Zeben, 2019), or the ability to address multiple goals in complex socio-ecological systems. This is not to say that polycentric governance systems are without any drawbacks. Indeed, their inherent complex designs may lead to internal conflicts among stakeholders (Lubell et al., 2020), high transactions costs due to the broad array of coordination measures, and even reduced accountability because of high dispersion or responsibilities among stakeholders (Carlisle and Gruby, 2019). Additionally, the performance of polycentric governance depends also on the specificities of the respective context, on the types of forums and cooperation arenas where stakeholders interact, and on the issues that bring them together. Therefore, polycentric governance will not succeed to the same extent in every setting (ibid.), and territorial constructs are eventually part of the factors that affect its functionality.

The concept of polycentric governance could indeed benefit from further clarification (Lubell et al., 2020; Carlisle and Gruby, 2019; Thiel et al., 2018), and a particular area of interest are governance studies that examine the role of polycentricity in addressing failures of decentralisation and territorial rescaling to achieve the objectives of efficiency and development cohesion. As a matter of fact, polycentric governance embodies competitive vertical and horizontal network interactions of autonomous decision-making institutions (Van Zeben, 2019; McGinnis, 2011; Ostrom, 1972; Ostrom et al., 1961), but the focus on territorial implications is insufficient. Even though polycentric governance raises also questions about its territorial dimension, the interaction between policy communities has remained its primary focus so far.

Our intention is to investigate whether polycentric governance can spur cooperation and efficiency throughout territorial rescaling when certain conditions are in place to address the polycentricity gap. These conditions are explained in detail in the following chapter and span from an overall decentralisation of the governance setting to the presence of multiple centres of decision-making that operate and compete within a system, and finally the territorial construct of the governance objective at stake. We formulate conditions referring to the reach scholarship on the functionality of polycentric governance, but also adding the territorial dimension. For this, we initially discuss theoretically territorial rescaling and polycentric governance to subsequently propose a model (of conditions) for analysing the polycentricity gap.

The model is applied to four governance cases (two development programs (regional and rural), participatory spatial planning, and forest common pool resources) in Albania, examined within the broader frame of Albania’s territorial rescaling reforms since 1990. We have chosen the cases to represent a diversity of governance arrangements and territorial scales, from the local to the regional and the national. Each case has at least a declared multi-level governance mechanism, but with different levels of decentralisation and initiating stakeholders. Also, at least one major territorial/administrative reform has taken place along each case. The research method is that of the case study for three of the cases, and investigation through observation, mapping and semi-structured interviews with commoners for the forest common pool resources.

Based on the analysis of the cases, the paper concludes that polycentric governance is adaptable and well-suited to handle the dynamics and effects of continuous political territorial rescaling, provided that the polycentricity gap is addressed in the first place. It also recognises that the number of the explored cases is rather limited to generalise the conclusion, therefore requiring the investigation of further cases. Finally, the results are contextual due to the territorial dimension, and, therefore, the application of the model to other territorial contexts would require a preliminary understanding of the respective territorial rescaling processes and the identification of contextual factors, including the related governance arrangements that have produced it or influenced it. This would lead to a recalibration of the model in terms of the indicators used to assess each of the polycentricity gap conditions.

It is hard to think of government without territory, the latter being commonly associated with a polity exercising power and authority within a space limited by designated boundaries (Lefebvre, 1974/1991, 2003; Taylor, 2003; Delaney, 2005; Keating, 2013, etc.). Originally geographically determined, territory has evolved towards being relational (Lefebvre, 1974/2003; Gottman, 1975; Harvey, 1993; Massey, 1993; Delaney, 2005; Raffestin, 2012), emphasising the social co-production. Faludi (2012) has criticised the container view on the territory as leading to the “territorial trap” (Agnew, 1994) and “poverty of territorialism” (Faludi, 2018), insufficient or ill-suited to govern the myriad of non-territorially bound social interactions and functions of an unknown or malleable spatial extent. Keating (2013) has argued between relational and deterministic approaches to the territory, maintaining both boundary and non-boundary views as valid, depending on the use purpose that a territory bears.

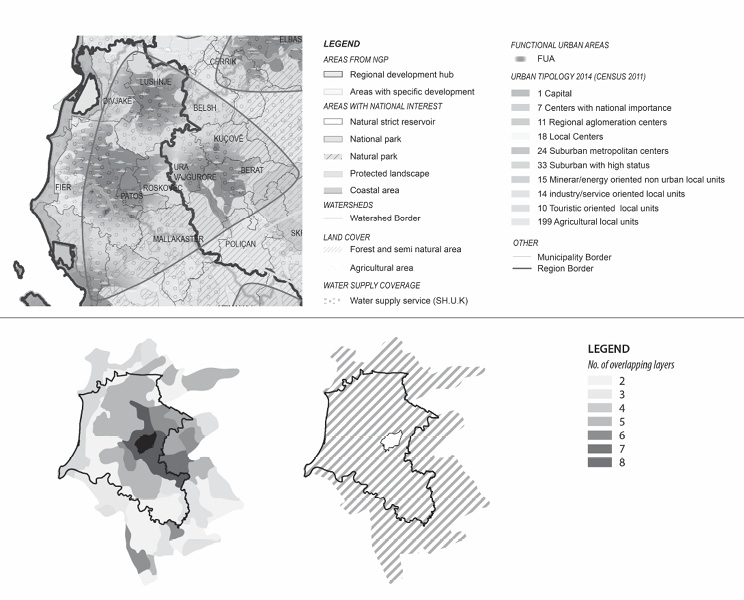

The territorial boundaries cause divides (Keating, 2014), best expressed through government jurisdictions. These jurisdictions are voting containers (Faludi, 2012) that seldom match functional boundaries, due to political implications, overlapping spatial typologies into ‘fuzzy territorial strips’ (Figure 1), and insufficient knowledge of the respective socio-ecological systems. Hence, territorial rescaling that favours the devolution of government as a solution to inefficiency and social-economic disparities (Mykhnenko and Wolff, 2018) instead produces further mismatch and complexity. The assumption that there exists an optimal scale for each territorial function (Hooghe and Marks, 2003, 2009) to which a government structure can be assigned is not helpful either, because once applied, it would still have to solve the governance of fuzzy strips. In addition, due to the relational character of the territory, a scale-fit, even if found, can never be permanent (Baldersheim and Rose, 2010).

To answer the question of governance efficiency for multiple and overlaying territorial levels, Hooghes and Marks (2001, 2003, 2016) have proposed in their seminal work two types of multi-level governance with logically coherent though alternative responses to coordination. The first focuses on interaction and power sharing between structures in a vertical hierarchy (Behnke et al., 2019) and the second on functional territories. Most institutional territorial rescaling involves type I, which tends to endure because of its political patronage and because it is modified only during policy and territorial reforms. With its rigid boundaries, type I cannot solve relational territorial problems, requiring ubiquitous type II arrangements – network-like, with overlapping memberships, locally and across levels. As territorial rescaling that implicates type I cannot perform the role of type II, the two systems must coexist and interact in a network of ‘policy communities’ (Clifton and Usai, 2018; Keating, 2014), embracing the conditions of polycentricity (Van Zeben, 2019; Carlisle and Gruby, 2017; Aligica and Tarko, 2012), and seeking territorial constructs that materialise the interests behind interactions. In this process, the policy communities must overcome multi-level governance gaps (OECD 2016, 2011), which emphasise the necessity for cross-scales and cross-actors cooperation, revealing a new gap, i.e., that of polycentricity. This gap entails the embeddedness of polycentric interactions into and among territorial constructs emerging from continuous rescaling processes.

Fig. 1. Fuzzy territorial strips, Fier, Albania

Source: own work (Shutina) for doctoral research, 2018.

The need to explore the polycentricity gap in multi-level governance has already been addressed in the introduction. Here we develop the model of conditions for analysing the polycentricity gap, basing it on the common understanding and findings on polycentric governance from literature. Polycentric governance is a highly complex multi-level, multi-type, multi-actors, multi-sector and multi-functional system (Van Zeben, 2019; Araral and Hartley, 2013; McGinnis, 2011; Boamah, 2018). It brings together territorial activities, structures and institutional designs in a polycentric network of formally independent centres of decision-making, or policy communities that compete under a specific set of rules, generating added value through synergies and mitigating conflicts (Lubell et al., 2020; Van Zeben, 2019; Boamah, 2018; Aligica and Tarko, 2012; Ostrom, 2008; Ostrom, 1972; Ostrom et al., 1961). In polycentric governance, emphasis falls on the independence of decision-making units, i.e., (local) governments and non-state actors, to self-regulate their actions in a self-concerted effort (ibid.) Obviously, this does not happen spontaneously, but it is bound by an “overarching shared system of rules,” “access to information,” and “capacity to learn” (Van Zeben, 2019, p. 27).

Homsy and Warner (2015) have argued empirically on the ability of local governments to achieve their objective efficiently by simply acting independently in a polycentric interaction. They promote instead multi-level governance with national governments supporting local action to raise efficiency,[4] by addressing the capacity and knowledge gaps with information moving up and down the levels of government (ibid., p. 53). As a matter of fact, such a finding only reinforces the conceptualisation of polycentricity in governance with all of its attributes, institutional essentials and prerequisites as summarised by Van Zeben (2019), shedding once again light on the implications of territorial scales in governance. Indeed, “polycentricity is the expression of a system’s capacity for self-governance, which over time will give rise to a complex system of governance institutions” (Van Zeben, 2019, p. 14), where the polycentric interaction does not exclude national governments. Instead, “decision-making centres also exist or operate across political jurisdictions” (Carlisle and Gruby, 2019, p. 938) and the involvement of national governments as one of the actors is inherent to the governance of nested or large scale (territorial) systems. Yet, this interaction has to happen upon an overarching system of shared rules (formal and informal) and the independence of the centres of decision-making, regardless of their level or size, should be guaranteed, as an inherent attribute of polycentric governance.

We conceptualise the polycentricity gap in a model of six conditions that policy communities should succeed on and apply to enable the embeddedness of polycentric governance in a setting of continuous territorial rescaling. We formulate these conditions (Table 1) based on the discourses of polycentric governance and territorial rescaling analysed so far, adding also from the conceptualisation of governance networks of Bogason and Zølner (2007, p. 6), citing Sorensen and Torfing (2006, Introduction, p. 9), the important dimension of contributing to the production of public purpose. In this paper, the public purpose is articulated broadly as the efficiency of services and functions and the territorial cohesion, or reduced disparities, towards which a multilevel governance system should steer, and may therefore relate to any policy objective.

| The polycentricity gap conditions | Carlisle and Gruby (2019, p. 20) |

Van Zeben (2019, p. 27) |

Bogason and Zølner (2007, p. 6) |

|---|---|---|---|

| The level of governance decentralisation |

Attribute: Multiple overlapping decision-making centres with some degree of autonomy Enabling condition: Decision-making centres exist at different levels and across political jurisdictions Enabling condition: Decision-making centres employ diverse institutions |

Institutional essential: Freedom and ability to enter and exit Institutional essential: Enforcement of shared system of rules Prerequisite: Access to justice |

Network governance is self-regulating within limits set by external agencies. |

| Subject of common interest for the decision-making centres |

Enabling condition: Decision-making centres exist at different levels and across political jurisdictions Enabling condition: Decision-making centres employ diverse institutions |

Prerequisite: Access to information | Contributes to the production of public purpose. |

| Independent interacting centres of decision-making |

Attribute: Choosing to act in ways that take account of others through processes of cooperation, competition, conflict, and conflict resolution Enabling condition: Decision-making centres participate in cross-scale linkages or other mechanisms for deliberation and learning |

Attribute: Multiple independent centres of decision making Attribute: Continuous competition, cooperation and conflict resolution Institutional essential: Peaceful contestation among different (interest) Groups Prerequisite: Capacity to learn |

Is a relatively stable horizontal articulation of interdependent, but operationally autonomous actors, who interact through negotiations. |

| Common niche of genuine attraction for cooperation |

Prerequisite: Access to information Institutional essential: Peaceful contestation among different (interest) groups |

||

| Territories to materialise the common and autonomous interests | Enabling condition: The jurisdiction or scope of authority of decision-making centres is coterminous with the boundaries of the problem being addressed |

Institutional essential: Peaceful contestation among different (interest) groups Prerequisite: Access to information Prerequisite: Access to justice |

|

|

A system of rules accepted by the actors in the network |

Enabling condition: Mechanisms for accountability exist within the governance system Enabling condition: A variety of formal and informal mechanisms for conflict resolution exists within the system Enabling condition: Generally applicable rules and norms, structure actions and behaviours within the system |

Attribute: Overarching shared system of rules Institutional essential: Enforcement of shared system of rules Prerequisite: Access to information Prerequisite: Access to justice Prerequisite: Capacity to learn |

Negotiations take place within a common regulative, normative, cognitive and imaginary framework. |

Source: own work.

In a summary, each condition is therefore described as follows:

The level of governance decentralisation: The national policy on governance should allow decentralisation and self-governance at sub-national levels, as well as decision-making autonomy for non-state actors (Van Zeben, 2019; Bogason and Zølner, 2007; Ostrom, 1959, 1993). This first condition is a contextual one in the sense that the level and type of decentralisation is variable and, therefore, the way in which it is measured will also vary between territories or states. Yet, this condition is a prerequisite for the following five to be met, because each is strongly linked to independent action and networking.

The subject of common interest for decision-making centres: The actors as centres of decision-making in a network have at least one common policy objective, related to the use of the territory, such as forests, water resources, tourism, economic development, etc., and to the governance objectives of cohesive development and efficiency. The policy objective(s) drive(s) their interaction in the network.

Independent interacting centres of decision-making: Polycentric governance brings several centres of decision-making, independent but complementary to one-another, and highly interactive among them in a three-dimensional network governance (Van Zeben, 2019; Carlisle and Gruby, 2019; Boamah, 2018; Berardo and Lubell, 2016; McGinnis, 2011; Bogason and Zølner, 2007; Ostrom, 1972; Ostrom et al., 1961). These centres handle applicable policy objectives in a constellation of cross-territorial connections and cooperation (Boamah, 2018; Berardo and Lubell, 2016).

Common niche of genuine attraction for cooperation: To achieve cooperation, there should be some minimal need or willingness for it – common niche of attraction for genuine cooperation among the centres of decision-making. This may be for instance the actors’ common desire to attract tourists in their area, each with specific interests. This common niche of attraction guarantees that individual actors engage in self-governance and are willing to spend considerable time and energy in crafting commonly accepted solutions and actively participating in their implementation (McGinnis and Walker, 2010). The ‘engagement’ in self-governance is what defines the difference between a ‘common niche of attraction’ and the ‘subject of common interest’. The ‘subject’ is a broad policy area/objective, which defines the scope and if absent, then there is no need to discuss cooperation at all. But for cooperation to occur, there should be competition that drives stakeholders towards identifying a niche of attraction within the subject and start interacting to achieve their interests (see Van Zeben, 2019).

Territories to materialise common and autonomous interests: For it to happen, cooperation requires a territory to use, to materialise the autonomous, complementary and/or competitive interests/objectives of actors. Territorial specificities and the construct define and shape the common niche of genuine attraction for cooperation (for instance mountainous versus coastal areas). In a metropolitan region there are many common interests (natural resources, infrastructures, industrial uses, etc.) The territorial construct is also the basis for the learning, information and knowledge prerequisite (see Van Zeben, 2019) to take shape and help achieving self-governance.

A system of rules accepted by the actors in a network: In polycentric governance, the autonomy of decision-making centres is pivotal to the notion, but the nodes do not operate in isolation. First, there is a constant interaction. Second, though it may seem as there is fragmentation due to size and overlapping scopes, as long as the centres compete by engaging in mutual value-added cooperation and in conflict resolution, they are considered as functioning as a system (Ostrom et al., 1961). Interaction happens based on a commonly agreed system of formal and informal rules (Van Zeben, 2019; Carlisle and Gruby, 2019; Boamah, 2018; McGinnis, 2011; Bogason and Zølner, 2007), avoiding overexploitation (tragedy of the commons) and under-consumption (free riders) dilemmas (Ostrom, 1990; Alexander and Penalver, 2012) as much as possible.

In chapter four, we analyse the governance cases in terms of the above six conditions. The qualitative indicators used to unravel each condition reflect the territorial constructs, rescaling and governance setting in Albania. The indicators were developed by Shutina in the frame of his doctoral research. We do not bring the indicators in this paper because these are contextual and exceed the scope of the paper, which is to provide a conceptual model, which for further application into various contexts should be adjusted for the indicators to reflect territorial and governance specificities. In order to contextualise our use of the model, we first provide a description of territorial development and rescaling in Albania.

The earliest study of regional disparities[5] in Albania covered the 2000s, revealing the country’s peripheral territorial development position compared to EU countries. Disparities between urban and rural areas, and among local governments were significantly higher than among regions.[6] The situation was similar in the two following studies by Shutina et al. (2016) and RDPA (2018). The analysis of over 110 indicators has shown that, economically speaking, the qark[7] of Tirana is always outdoing other qarks, while from an environmental perspective it is historically underperforming.

In addition, Albania has a monocentric territorial structure,[8] the unit of analysis being the 18 functional urban areas (FUA) defined by Toto et al. (2015).[9] The morphological polycentrism index, composed of three equal-weight sub-indices (size, location, and connectivity) has revealed a substantial level of polarisation (polycentricity index[10] 65.1 versus 56.2 of ESPON space in 2005[11] (ESPON, 2005, p. 73)). Polarisation is very high for the size index (97 – based on GDP and population according ESPON, (2005) and Spiekermann et al. (2015)), and high for the connectivity index (72.2). The dominant FUA is that of Tirana. The location index is low (28), revealing a “uniform distribution of cities across the territory” (ESPON, 2005, p. 60). The latter is due to historical path dependency[12] and suggests a locational opportunity for a polycentric territorial network of urban settlements in Albania. Yet, no government has supported the development of polycentrism and spatial polarisation is expected to sharpen. In addition, the functional polycentricity is low, too (Toto et al., 2015).

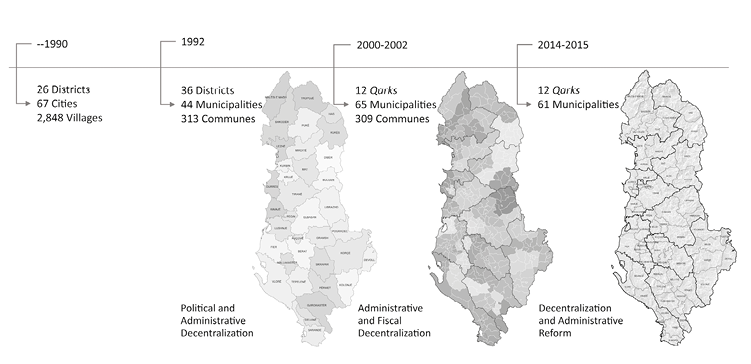

This territorial development has occurred alongside the institutional territorial rescaling processes (Keating, 2014) of the last 30 years. The first governance shift was the introduction of political decentralisation in 1992 following half a century of centralised government under the communist regime. By the end of the communist system in 1990, Albania had its centralised government organised locally into three levels, the urban areas (67 cities), the rural areas (2,848 villages), and 26 districts (regions). The pre-1990s model had a strong influence on the territorial structure of local government’s organisation in the decade of 1990–2000. In 2000, the parliament adopted the first law on local governments[13], organising them into two levels: municipalities (65 urban areas) and communes (309 rural areas) as the first tier; and 12 qarks as the second one. The district (36 such units) was maintained as a historical subdivision, merely to facilitate transition between systems, as most statistics were collected on that level, and several deconcentrated regional ministerial directorates operated at the district level. Local governments had exclusive/own and shared functions, yet, with functional and fiscal power limitations based on respective sectorial laws.

The Government of Albania revisited the decentralisation reform in 2014–2017 (Fig. 2) aiming at decentralising further functionally and fiscally. The reform, including at least three new laws, was supposed to tackle the low territorial, economic and institutional efficiency of service delivery at the local government level (Toto et al., 2014; Shutina, 2015), and spatial disparities. 373 local government units were merged to form 61 municipalities, becoming larger in size (Tirana being the largest one and growing from 45 sq. km to 1,100 sq. km), but also territorially more complex, with urban and rural areas, agricultural land and natural resources. This mixture alone is the epitome of the challenges in the implementation of the reform, by increasing the number of tasks and the volume of legal framework with which municipalities should deal, while also requiring diversification and consolidation of human and financial resources.

Fig. 2. Territorial rescaling processes after 1990, Albania

Source: own work.

The territorial tier that remained intact during the reforms was the qark. Since 2000, political actors intentionally have not given the qark any well-differentiated competences of governance. They merely assigned it a monitoring, coordinating and oversighting role for first-tier units to mitigate potential inefficiencies arising from a lack of cooperation, assuming that local governments have no concern for the spill-over effects of their activities beyond their administrative boundaries. To date, the qark is a territorial construct of a very weak governance role and weak historical identity, adding to the myriad of local government systems of Central and East European countries, characterised by weak intermediary levels of government (Swianiewicz, 2014; Loewen, 2018). Nonetheless, the qark’s mere presence is constantly used politically as an argument to block or contest development reforms.

These administratively-driven territorial rescaling processes have always claimed five criteria: political representation; the efficiency of service delivery; the economy of scales; local self-determination; and historical ties and boundaries. The criteria have been applied unevenly across the territory, with territorial polity dictating the final decision. The political actors declared efficiency and economy of scales as the reasons for initiating reforms, but overrode them in the course of each reform. The concept of ‘functional area’ was moulded to fit the political discourse and make decisions incontestable. In addition, the political language has constantly articulated historical ties merely to manipulate community sensitivities and achieve political ambitions. Finally, local self-determination would have been mere vocabulary had it not been for the existence of ethnic minorities, which were bestowed the right to govern autonomously the territories where they were settled. Basically, Albania’s territorial reforms emphasised the territorial dimension solely to accomplish power redistribution. Additionally, local governments were not keen either on embarking on territorial reforms, as they considered those as weakening the authority of local political stakeholders. They have continuously explored forms of territorial cooperation and, despite capacity gaps, they have come to far more rewarding solutions for their own territorial disparities and fragmentation than the top-down amalgamation. While also acknowledging urban-rural and regional disparities as problems that exceed their scale, blessed with place knowledge, local governments do not consider territorial rescaling neither a panacea, nor a one-time remedy, particularly when the political weight of a reform surpasses the genuine intention for sustainable territorial development.

In the autumn of 2021, the new government which formed after the national elections and the opposition political forces, expressed willingness to implement a new territorial and administrative reform. This potential rescaling phase has not turned into a commitment yet, but it is one of the headlines of political discourse in Albania.

As part of institutional territorial rescaling reforms, successive governments have adopted and implemented policies, programs, and practices, in a multi-level approach, aiming at enhancing territorial development and reducing spatial disparities. After the reform of 2000, the governments have focused on deepening functional and fiscal decentralisation for efficient services provision, higher accountability, increased financial resources, and enhanced capacities. In the subsequent reform, the government framed its programs and investments within regional development and regional policy as a remedy for the efficiency and governance failures of decentralisation and as a means leading to cohesion. This chapter will analyse the six conditions for addressing the polycentricity gap in four multi-level governance cases of policies and programs spanning across the reforms, in the context of persisting failures, including territorial disparities.

Each case has specific objectives of territorial development, but all aim at cohesion. In addition, each case is intertwined differently with the territorial rescaling processes since 1990 and they do not satisfy equally the polycentricity gap conditions.

Urban Renaissance (UR) was the regional development programme implemented by the government in the years 2014–2018, extending to almost every municipality in Albania (70 urban areas). UR, funded through the Regional Development Fund (RDF), aimed at regenerating public spaces in urban centres, assuming these interventions would resonate causing catalytic development effects regionally. Trackable data from the Ministry of Finance and Economy helps one understand how the fund operated territorially. Thus, in 2014–2018, almost all urban centres in Albania acquired between 200,000 euros and 30,000,000 euros for public space regeneration only, totalling approx. 147 million euros, or 41% of the RDF. The government reported 159 such projects by the end of 2017. Out of 61 municipalities, Tirana received the largest number of projects (13) and funds (approx. 30 million euros), followed by Durrës with 10 projects and approx. 20 million euros.

UR intended to promote the establishment of territorial partnerships. Historically, the RDF has been distributed on a competitive basis to support infrastructure improvements and has been allocated to line ministries or other relevant institutions for capital expenditures. The major institutional change for RDF during the UR implementation was the consolidation of funds previously allocated to ministries, and distributing them to local governments on a competitive basis (Dhrami and Gjika, 2018).

A detailed expenditure track study is necessary to draw the potential effects of these investments on the local and regional economies. The disparities analyses (2014–2018) do not reveal any improvements to regional development profiles, with disparities sharpening further. Hence, the program had an effect on city/urban landscape, improving urban quality, but not necessarily on development indicators. Ultimately, UR supported projects of local relevance and effect. In addition, RDF funds for UR were allocated through top-down decision-making and in direct communication with mayors, side-stepping other stakeholders.

The Integrated Rural Development Program, known as ‘100+ Villages’ is an ongoing initiative of the Prime Minister and the Ministry of Agriculture. Its aim is to coordinate development interventions in rural areas, through a cross-sectorial and multi-stakeholder approach, in line with the objectives of regional development as defined in the National Strategy for Development and Integration, and as a model that moves away from disconnected and fragmented interventions on the territory. Municipalities and the Albanian Development Fund (ADF) started gradually the implementation in 2019. According to ADF and Ministry of Agriculture reports, around 19 out of 100 villages received investments of over 81 billion euros in total[14] by 2020. Though implementation is not limited to public institutions, the funds so far have been allocated from the state budget and international donors, with no public-private partnerships being formed around investments. The specific objectives[15] of the program are: (i) Improvement of public infrastructure and public space; (ii) Economic development through diversification of activities; (iii) Development of social and human capital through rural networks, local action groups, vocational training, etc.; (iv) Establishment of the Albanian agritourism network; and (v) Creation of traditional brand store chain.

However, the projects implemented so far have focussed mostly on public space regeneration in village centres and the improvement of facades for traditional architecture buildings. Fewer investments went to agricultural activities, and the ministry of tourism invested in signs and information boards. Unlike the slow progress and fragmentation of implementation, the mobilisation of the program was strategically well-structured. Launched in early 2018, the challenge was to turn its objectives into concrete projects with a dedicated financial portfolio, reflecting the government’s interests and local issues. Therefore, the government built a governance mechanism, led by an inter-ministerial committee, which approves allocation and distribution of funding. At the technical level, the advisor to the Prime Minister on planning issues and the National Territory Planning Agency (NTPA) coordinated the design process, implemented with the involvement of five universities. NTPA assigned each university a group of villages and launched in the spring of 2018 the ‘100+ Villages Academia’, which produced development visions and proposed projects for implementation. The output of the academia guided the 2019–2020 budgetary provisions.

The fieldwork by universities, besides generating, gathering and exchanging knowledge, entailed also communication and negotiation with local communities, to justify not merely the legal requirements for participatory processes, but also a necessity to respond efficiently to territorial constructs. The proposals contained the views and requests of local communities. The management was decentralised, but decision-making remained central. Municipalities facilitated communication and knowledge exchange locally, and with the national government. Municipalities and communities did not have a say in the approval of programming documents, visions, or projects. They influenced the outcome only by being involved in the design phase.

To date, there has been no definitive figure regarding the total forest area in Albania, which varies between 20%[16] and 30% of the territory (Toto, 2019; Global Forest Watch, 2019; FAO[17], 2017). The current government’s initiative of establishing a forests’ cadastre should provide accurate and up-to-date figures, including fragmentation and a decrease of the total area/volume over the years, but it is still ongoing. The forest area is decreasing, despite the moratorium set by the government in 2016.[18]

A major institutional change was the introduction in the law in 2015 of forest governance as an exclusive function of local governments. Municipalities currently manage 82% of the forest area in Albania, 3% of forest land is privately owned, and 15% are forests classified as environmentally protected areas, which are managed centrally.[19] The forestry law had not recognised a regime of common forests governance, i.e. forests owned or managed in common by the adjacent living communities, until 2020. The recently approved law recognises these communities’ right to use forests, establishing community structures to manage forests in cooperation with local governments.

Toto (2018) has explained that at least 30% of municipal forests, located at altitudes of 800–1,200 metres above sea level and adjacent to rural settlements, are governed through a system of common pool resources (CPR). Until 2020, forest CPRs had been rather informal, ‘allowed’ by municipalities due to a lack of financial and human resources to execute their own function. The proximity factor is important in linking people to forests because it makes it easier and feasible to take care of them, and local families have sufficient knowledge in doing that. In addition, people value forests’ provisioning, regulatory and spiritual ecosystem services (Toto, 2019). Furthermore, before 1944, a portion of the forest land had been governed in common in Albania and this was recognised in both customary and modern laws (Gjeçovi, 1925; Ministria e Ekonomisë Kombëtare, 1930), with forest CPRs functioning through ‘proprietary rights’ (Ostrom, 2003). Historical ties were/have been strong and local population’s memory is so vivid that forest CPRs were reborn after 70 years of missing institutional support. Local communities have established internal sets of rules upon which each family takes care of its ‘share’ of common forests and all families monitor together (Toto, 2019). A nested forest CPR system exists with more than 200 local forest associations, all acting on behalf of the local commoners and supporting them (whenever possible) financially. The National Forest Federation is the highest-level entity and it supports the lower levels/nodes in the polycentric system through projects, funds, technical advice, and lobbying and advocacy at the national policy-making level.

Territorial planning is shared between local and national institutions. Municipalities draft local plans and local councils adopt them. However, comprehensive local territorial plans that address entire local territories are approved also by the National Territory Council. Additionally, the NTPA, as a technical body, monitors local planning processes, provides advice, and issues acts of compliance with the legislation and national territorial plans. The decision-making system is pyramidal, but legislation has defined the involvement of various actors during the planning process, constitutionalising a network of territorial governance interactions. Communities and interest groups do not have any decision-making authority, but they can influence decisions.

There are currently three participatory planning mechanisms, which constitute a nested system that is partially constitutionalised, and partially agreed upon by stakeholders themselves to improve their influence in the process:

In Hooghes and Marks’ (2003) taxonomy, the UR program and the 100+ Villages belong to type I arrangements, forest CPRs settle in the type II, while planning forums fall in between the two types. The government initiated and implemented the UR program concurrently with the territorial administrative reform of 2014. The implementation of the 100+Villages program started after the adoption of the new local government boundaries. Forest CPRs have existed since the early 2000s, surviving all territorial rescaling reforms. CAPs as part of the planning forums have existed since the early 2000s, while the other forums were born with the territorial reform of 2014.

The UR and the 100+ Villages programs were aimed at tackling spatial disparities, and creating visibility and an attractive image for the political ambition and its territorial power. As central government programs, they have had the opportunity to be territorially strategic. However, the fragmented intervention of UR, and the low number of projects implemented so far in the 100+ Villages program, make the approaches more of an injection, without regional effects. Studies on regional disparities have not reported so far any reduction of inequality. Tourism and services have been stimulated from investments, which increased confidence within respective local communities. The 100+ Villages program, though only partially implemented, was better diffused into the territory, because of its co-design process.

The purpose of the planning forums was to combine type I and type II multi-level governance approaches in one territorial planning governance system. CAPs depend particularly on a community’s organisation capacity and willingness to convey local knowledge in decision-making. The other forums depend on the accountability and coordination capacity of respective government entities. Finally, forest CPRs, aim to ensure resilience and local development objectives, adapting to the evolving institutional context. The polycentricity gap is almost fully addressed in forest CPRs and the system has been resilient since before 1945. More in detail in Table 2.

The UR program was envisioned as a program of multi-level polycentric governance with bottom-up initiatives feeding top-down programming and decisions into partnership-based implementation. Yet in reality, priorities were set centrally, the network of local actors was non-existent or bypassed, and the common interest was limited to political objectives. Instead of a competitive projects’ selection process, there were direct negotiations between mayors and the RDF committee. This undermined the public system of rules. Furthermore, UR was not based on the national strategy for development, or on the national territorial plan, or on any regional development policy.

The 100+ Villages program engaged numerous stakeholders during the design phase. They all had a common niche of genuine attraction for cooperation. The central government had an interest in inner peripheries and lagging regions. Through cooperation, the government was able to pack all initiatives into one financial portfolio to control during allocation and implementation. By mobilising the academia, the network of stakeholders was inclined to agree on a set of implementation rules. The program adopted polycentric governance during planning, but not during implementation. The full assessment of the program can only be concluded when it finishes, i.e., in 2022.

The Forest CPRs system of Albania is fully decentralised and polycentric, with a nested system, where nodes and layers have various degrees of power and decision-making across the territorial scales. Commoners and local associations cooperate with municipal officials. This complex system of polycentric governance works based on a set of internal rules and legislation. All critical factors for polycentric governance are fulfilled and the system is efficient, robust and adaptable to territorial dynamics. The recent legal changes will help the system extend CPR governance to larger forest areas, and increase the commoners’ opportunity to access public funds for forest maintenance.

The participatory planning forums form a system that fulfils almost all of the six polycentricity gap conditions. However, the system is not fully decentralised and the decision-making authority is shared among government institutions, with the exclusion of non-governmental actors. The latter’s role is limited to influencing the design stage. All these interactions are conducted within a nested system of stakeholders and networking relations clearly defined in a territory, where powers and authority are not equally shared among participants. The management and approval structures, as well as the sets of rules are clear.

| Conditions of polycentricity gap | ‘Urban Renaissance’ | ‘100+ Villages’ | Participatory Planning Forums | Forest CPRs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Governance decentralisation | No: Central decision-making; Communication to other stakeholders in the network. | No: Central decision-making; Beneficiaries and experts influenced decision during design phase. | Partially: Centralised – to – decentralised approaches; Unequally distributed across national territory. | Yes: Decentralised decision-making. |

| 2. Subjects of common interest for decision-making centres | Partially: Urban regeneration of city centres, for central government; Local development for the urban areas. |

Yes: Establish development practices for rural areas; Enhance tourism potential; Increase local economic opportunities. |

Yes: The General Local Territory Plans, approved by the Municipality and the National Territory Council. | Yes: Ensure sustainable use of local forests; Maintain forests legacy. |

| 3. Independent centres of decision-making | No: The central authorities manage the program and approve funds. | No: The central authorities manage the program; local actors influence the outcome of design phase. | Partially: All three types of planning forums as nodes of a larger participatory planning network. | Yes: Commoners; village-based groups of commoners; local forest associations; National Forest Federation. |

| 4. Common niche of genuine attraction for cooperation | No: Weak convergence between government interest and local needs for services & economic opportunities. | Partially: Economic/business opportunities and tourism activities for local development. | Yes: Concrete proposals on housing, land use, businesses’ locations and recreational activities. | Yes: Common forests, located adjacent to villages involved in the nested system of forest governance. |

| 5. Territories to materialise the common and autonomous interest | Yes: Centres of cities as government intention for urban cores to resonate into regions. | Yes: Village centres, clusters of villages: each defining the core of a specific rural region, representing sub-regions. | Yes: Local government administrative jurisdiction area. | Yes: Forest ecosystems in the country: close to villages, owned or managed in common prior 1940. |

| 6. System or rules accepted by actors in the network | Partially: Legal rules and implementation frameworks only. | Yes: Legal rules and frameworks mostly. Rules of participation defined ad hoc during design stage. | Yes: Internal rules always. A minimum of legally defined rules for the national forum and for local forums, not CAPs. | Yes: Internal rules always; fulfilment of forest legislation as well. |

Source: own work.

These four cases reveal different response to the territorial reforms’ dynamics, due to different levels of addressing the polycentricity gap. The more centralised the decision-making is, even in the case of capillary investments in a territory, the fewer conditions of the polycentricity gap are satisfied, and the less effective the system is. The knowledge factor is also very important. The case of forest commons is successful because knowledge about commons is available and transferable among stakeholders and generations. In the case of forums for participatory planning, knowledge and dissemination and exchange mechanisms have not increased the trust of the participants among themselves and on local governments, nor has the participants’ willingness to be involved and contribute to the planning output.

Finally, the territorial distribution of the cases is quite diverse. The cases with centralisation of power and authority have a hierarchical structure of multi-level territorial organisation. The amalgamation of local governments and the centralisation tendencies on the allocation of development funds suit the territorial display of governance in UR and in 100+ Villages. When decentralisation is high, as in forest CPRs or in CAPs, the territorial structure is also decentralised and polycentric from a functional perspective, represented by various centres of decision-making distributed across the territory. The sizes of municipalities have been irrelevant to the functioning of governance in these two cases, and the respective local government functions in each case have been effectively delivered because multi-actor cooperation and networking were at the core of the governance model, regardless of the changing administrative boundaries.

In Albania, consecutive governments have addressed local governance inefficiencies and territorial development through designation of optimal levels and sizes of government in the territory, considering network cooperation and functional interactions as institutionally sophisticated or inadequate to the context. The political discourse has almost uniquely influenced territorial reforms. The resulting arrangements of governance shifts have become more complex, without responding precisely to the needs for which the reforms were initiated all along. The government opted initially for a small-scale local government, to emphasise the need for closer links with citizens and to increase accountability. The small scale produced territorial fragmentation, which affected efficiency and redistribution negatively. Fragmented local governments can only allow for cross-subsidies, unless multi-actors’ cooperation and networking are in place. The resulting amalgamation did not lower disparities either. Actually, it concealed them, showing that any efficiency improvement in service delivery did not enhance territorial development. The institutional rescaling was in search for optimal territorial levels for each task, but such areas do not seem to exist, and even if they did, there is a complete asymmetry among local contexts and use purposes.

This paper started with the assumption that institutional territorial rescaling, implemented to eliminate governance inefficiencies, lower disparities, and boost territorial development, will still produce territorial constructs of fuzzy boundaries and complex governance, while not necessarily yielding cohesion. Whether through upscaling – more consolidation, or downscaling – further subdivision, new forms of territorial fragmentation will appear, particularly due to fixed, not so swift to change voting territorial containers. Multi-level governance that builds on polycentric interaction, without searching for optimal jurisdiction sizes, may enhance territorial development if the conditions to address the polycentricity gap in governance are satisfied.

To substantiate the assumption, we explored polycentric governance and examined the conditions to close the polycentricity gap in multi-level governance in Albania, in a setting of territorial rescaling and development that has spanned the last 30 years. As most CEE countries, Albania also went through government decentralisation since the outset of the transition in 1990. The autonomy of local governments and the respective high initial level of territorial fragmentation largely prevented rescaling efforts (see Loewen, 2018) from occurring for more than a decade. Subsequently, the government embarked on two other institutional rescaling processes for government and administrative boundaries, focusing only on the local level of the government. As a result, the regional level and regional development remained in hibernation, sometimes slightly animated by the government to justify its political ambitions for territorial rescaling. In this context of continuous territorial rescaling, policy objectives such as territorial development and cohesion and governance efficiency remained unsatisfied. This was due to both, the inherent gaps of multi-level governance and the political motivation behind the reforms. Therefore, taking the voting containers as a rather rigid territorial construct, we have argued that the way forward to achieve the policy objectives of cohesion and efficiency is through the embedding of partnerships and polycentric interactions in multi-level governance.

Methodologically, we built a model of six conditions of the polycentricity gap in governance and applied it to four cases of multi-level governance. Out of the four, two cases satisfied all or most of the polycentricity gap conditions, and revealed a significantly higher level of achievement of their policy objectives, including endurance, flexibility, and adaptation during all three rescaling periods, as opposed to the remaining cases. We conclude that addressing the problems of scale in multi-level governance implies overcoming the polycentricity gap and embedding polycentric interactions into territorial constructs generated by or contributing to continuous territorial rescaling. In a polycentric governance system, no one has the ultimate monopoly (Aligica and Tarko, 2012) and policy communities have decision-making authority, which they utilise based on a commonly agreed system or rules (laws and informal regulations). The power, which is related to specific policy objectives, diffuses among social actors instead of being captured by government institutions only. Policy communities are formed at various overlaying territorial scales and represent both, government and non-government actors. In order to adapt to the territorial rescaling dynamics, policy communities as centres of decision-making should share common interests that are materialised in territorial constructs.

On a theoretical level, this research adds to the efforts of polycentric governance scholars for “developing greater clarity around the concept of polycentric governance and the conditions under which it may lead to desired outcomes” (Carlisle and Gruby, 2019, p. 928). It does so by proposing a model that builds on the comparative deployment of dimensions, attributes, and enabling institutional conditions and prerequisites for polycentric governance identified by other authors, while bringing in a less researched dimension, i.e., the territory. The application of the model to the Albanian context yielded the expected results. However, we recognise two limitations of the research: i) the number of cases is limited – four cases, each representing a unique typology, and ii) all cases pertain to the Albanian context of territorial rescaling and development. Therefore, while the results provide a satisfying indication on the role of polycentric interactions in territorial multi-level governance, they also suggest the necessity for expanding the approach towards a larger number of cases and territorial contexts. In order to verify the validity of the model beyond the Albanian context, particularly in the Western Balkans where territorial rescaling dynamics resemble more the Albanian ones, the variables per each polycentricity gap condition should be adjusted to the territorial and governance specificities. Such a customisation is important for the validity of the model, and it basically emphasises that the territory is a contextual factor that affects polycentric interactions and, therefore, it creates variability of polycentric governance results in the different settings.

Acknowledgements. This paper builds on the doctoral research of Dritan Shutina, for his dissertation entitled Territorial Rescaling for Polycentric Governance: The Case of Albania’s Regions, defended in the framework of the IDAUP Ph.D. joint program of Ferrara University and POLIS University of Tirana in 2019.

AGNEW, J. (1994), ‘The territorial trap: The geographical assumptions of international relations theory’, Review of International Political Economy, 1 (1), pp. 53–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/09692299408434268

ALIGICA, P. D. and TARKO, V. (2012), ‘Polycentricity: From Polanyi to Ostrom, and Beyond’ Governance: An International Journal of Policy, Administration, and Institutions, 25 (2), pp. 237–262. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0491.2011.01550.x

ARARAL, E. and HARTLEY, K. (2013), ‘Polycentric Governance for a New Environmental Regime: Theoretical Frontiers in Policy Reform and Public Administration’, International Conference on Public Policy, Grenoble, 2013. IPPA. [Online] http://s3.amazonaws.com/arena-attachments/1753533/2d3d2d983dc492fdd09ad1d34af4aaab.pdf?1518527912 [accessed on: 9.01.2021].

BALDERSHEIM, H. and ROSE, L. E. (2010), ‘Territorial Choice: Rescaling Governance in European States’, [in:] BALDERSHEIM, H. and ROSE, L. E. (eds.), Territorial Choice The Politics of Boundaries and Borders, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230289826_1

BEHNKE, N., BROSCHEK, J. and SONNICKSEN, J. (2019), ‘Introduction: The Relevance of Studying Multilevel Governance’, [in:] BEHNKE, N., BROSCHEK, J. and SONNICKSEN, J. (eds.), Configurations, Dynamics and Mechanisms of Multilevel Governance, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 23–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-05511-0_1

BENZ, A. (2019), ‘Transformation of the State and Multilevel Governance’, [in:] BEHNKE, N., BROSCHEK, J. and SONNICKSEN, J. (eds.), Configurations, Dynamics and Mechanisms of Multilevel Governance, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-05511-0_2

BOAMAH, E. F. (2018), ‘Polycentricity of urban watershed governance: Towards a methodological approach’, Urban Studies, pp. 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098017750080

BOGASON, P. and ZØLNER, M., (2007), ‘Methods for Network Governance Research: an Introduction’, [in:] BOGASON, P. and ZØLNER, M. (eds.), Methods in Democratic Network Governance, Hampshire: Plagrave Macmillan, pp. 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230627468_1

CARLISLE, K. and GRUBY, R. L. (2019), ‘Polycentric Systems of Governance: A Theoretical Model for the Commons’, Policy Studies Journal, 47 (4), pp. 927–952. https://doi.org/10.1111/psj.12212

CLIFTON, N. and USAI, A. (2018), ‘Non-state nations: Structure, rescaling, and the role of territorial policy communities, illustrated by the cases of Wales and Sardinia’, Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, pp. 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654418815695

DELANEY, D. (2005), Territory: a short introduction, Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470773925

DHRAMI, K. and GJIKA, A. (2018), ‘Albania, Towards a More Effective Financing Mechanism for Regional Development’, Annual Review of Territorial Governance in Albania, 1, pp. 24–37. https://doi.org/10.32034/CP-TGAR-I01-02

ESPON (2005), Potentials for polycentric development in Europe: ESPON 1.1.1. Project Final Report, Luxembourg: ESPON. ISBN: 91-89332-37-7

ESPON (2019), Territorial Reference Framework for Europe. ESPON EGTC, Discussion Paper No.5.

FALUDI, A. (2012), ‘Multi-Level (Territorial) Governance: Three Criticisms’, Planning Theory and Practice, 13 (2), pp. 197–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2012.677578

FALUDI, A. (2018), The Poverty of Territorialism. A Neo-Medieval View of Europe and European Planning, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788973618

FINKA, M. and KLUVANKOVA, T. (2015), ‘Managing complexity of urban systems: A polycentric approach’, Land Use Policy, (42), pp. 602–608. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2014.09.016

GJEÇOVI, S. (1925), Kanuni i Lekë Dukagjinit, Tiranë: Shtëpia Botuese “Kuvendi”.

GOTTMANN, J. (1975), ‘The evolution of the concept of territory’, Social Science Information, 14 (3), pp. 29–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/053901847501400302

HARVEY, D. (1993), ‘From space to place and back again: Reflections on the condition of postmodernity’, [in:] BIRD, J., CURTIS, B., PUTNAM, T., ROBERTSON, G. and TICKNER, L. (eds.), Mapping the futures. Local cultures, global change, London: Routledge, pp. 2–29.

HOMSY, G. C. and WARNER, M. E. (2015), ‘Cities and Sustainability: Polycentric Action and Multilevel Governance’, Urban Affairs Review, 51 (1), pp. 46–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087414530545

HOOGHE, L. and MARKS, G. (2001), ‘Types of Multi-Level Governance’, European Integration online Papers (EIoP), 5 (11). https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.302786

HOOGHE, L. and MARKS, G. (2003), ‘Unravelling the Central State, but How? Types of Multi-level Governance’, American Political Science Review, 97 (2), pp. 233–243.

HOOGHE, L. and MARKS, G. (2009), ‘Does efficiency shape the territorial structure of government?’, Annual Review of Political Science, 12, pp. 225–241. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.12.041107.102315

HOOGHE, L. and MARKS, G. (2016), ‘Community, Scale, and Regional Governance’, A Postfunctionalist Theory of Governance, 2. 1st edition, Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198766971.003.0001

KEATING, M. (2013), Rescaling the European State: The Making of Territory and the Rise of the Meso, 1st edition, Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199691562.001.0001

KEATING, M. (2014), ‘Introduction: Rescaling Interests’, Territory, Politics, Governance, 2 (3), pp. 239–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2014.954604

LEFEBVRE, H. (2003), ‘Space and the State’, [in:] BRENNER, N., JESSOP, B., JONES, M. and MACLEOD, G. (eds.), State/Space: A Reader, Malden: Blackwell, pp. 84–100. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470755686.ch5

LOEWEN, B. (2018), ‘From Decentralization to Re-Centralization: Tendencies of Regional Policy and Inequalities in Central and Eastern Europe’, Administrative Culture, 18 (2), pp. 103–126. https://doi.org/10.32994/ac.v18i2.162

LUBELL, M., MEWHIRTER, J. and BERARDO, R. (2020), ‘The Origins of Conflict in Polycentric Governance Systems’, Public Administration Review, 80 (2), pp. 222–233. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.13159

MASSEY, D. (1993), ‘Power-geometry and a progressive sense of place’, [in:] BIRD, J., CURTIS, B., PUTNAM, T., ROBERTSON, G. and TICKNER, L. (eds.), Mapping the futures. Local cultures, global change, London: Routledge, pp. 60–70.

MCGINNIS, M. D. (2011), ‘Networks of Adjacent Action Situations in Polycentric Governance’, The Policy Studies Journal, 39 (1). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-0072.2010.00396.x

MCGINNIS, M. D. and WALKER, J. M. (2010), ‘Foundations of the Ostrom workshop: institutional analysis, polycentricity, and self-governance of the commons’, Public Choice, 143, pp. 293–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-010-9626-5

MEIJERS, E. and SANDBERG, K. (2008), ‘Reducing regional disparities by means of polycentric development: panacea or placebo?’, Scienze Regionali, 7 (2), pp. 71–96.

MINISTRIA E EKONOMISË KOMBËTARE (1930), Ligja e Pyjeve e Kullosave, Tiranë, Albania: Botime të Ministrisë së Ekonomisë Kombëtare, Shtypshkronja “Tirana”.

MYKHNENKO, V. and WOLFF, M. (2018), ‘State rescaling and economic convergence’, Regional Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2018.1476754

OECD (2011), ‘Water Governance in OECD countries: A multi-level approach’, OECD Studies on Water, OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264119284-en

OECD (2016), ‘Water Governance in Cities’, OECD Studies on Water, Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264251090-en

OSTROM, E. (1990), Governing the Commons, The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action, New York: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511807763

OSTROM, E. (2003), ‘How Types of Goods and Property Rights Jointly Affect Collective Action’,

Journal of Theoretical Politics, 15 (3), pp. 239–270. https://doi.org/10.1177/0951692803015003002

OSTROM, E. (2005), Understanding Institutional Diversity, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

OSTROM, E. (2008), Polycentric systems as one approach for solving collective action problems. [Online] Digital Library Of The Commons Repository – Indiana University http://dlc.dlib.indiana.edu/dlc/bitstream/handle/10535/4417/W08-6_Ostrom_DLC.pdf [accessed on: 14.05.2018].

OSTROM, V. (1959), ‘Tools for Decision-Making in Resource Planning’, Public Administration Review, 19 (2), pp. 114–121. https://doi.org/10.2307/973681

OSTROM, V. (1972), Polycentricity. [Online] APSA, http://hdl.handle.net/10535/3763 [accessed on: 9.05.2018].

OSTROM, V. (1993), ‘Epistemic Choice and Public Choice’, Public Choice, 77 (1), pp. 163–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01049230

OSTROM, V., TIEBOUT, C. M. and WARREN, R. (1961), ‘The organization of government in metropolitan areas: Theoretical Inquiry’, The American Political Science Review, 55 (4), pp. 831–842. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055400125973

RAFFESTIN, C. (2012), ‘Space, Territory, and Territoriality’, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 30 (1), pp. 121–141. https://doi.org/10.1068/d21311

RDPA (2018), Regional Disparities in Albania, Analytical reports in the frame of Regional Development Program in Albania, Tirana. With the support of Swiss Development Cooperation.

SHUTINA, D. (2015), Towards Regional Operational Programming: Methodology for DOP/ROPs, Tirana: Swiss Development Cooperation for the Government of Albania.

SHUTINA, D., BOKA, M. and TOTO, R. (2016), Assistance to Regional Development Policy Reform in Albania - 2015: Towards Regional Operational Programming. Analytical, Tiranë: Swiss Development Cooperation and GIZ.

SPIEKERMANN, K. et al. (2015), ‘TRACC Transport Accessibility at Regional/Local Scale and Patterns in Europe: Volume 2 TRACC Scientific Report’, Applied Research; Final Report | Version 06/02/2015. Luxembourg: ESPON.

SWIANIEWICZ, P. (2010), ‘If Territorial Fragmentation is a Problem, is Amalgamation a Solution? An East European Perspective’, Local Government Studies, 36 (2), pp. 183–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930903560547

TAYLOR, P. J. (2003), ‘The state as container: Territoriality in the Modern-World System’, [in:] BRENNER, N., JESSOP, B., JONES, M. and MACLEOD, G. (eds.), State/Space: A Reader, Malden: Blackwell, pp. 101–113. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470755686.ch6

THIEL, A. and MOSER, C. (2018), ‘Toward comparative institutional analysis of polycentric social‐ecological systems governance’, Environmental Policy & Governance, 28 (4), pp. 269–283. https://doi.org/10.1002/eet.1814

TOTO, R. (2010), ‘Rajonalizimi i Shqipërisë në debat - fuqizimi i decentralizimit dhe evoluimi drejt zhvillimit rajonal’, [in:] SHUTINA, D. and TOTO, R. (eds.), Politikëndjekës apo Politikëbërës Alternativa mbi Zhvillimin urban, manaxhimin e territorit dhe të mjedisit. 1st edition, Tiranë: Co-PLAN dhe Universiteti POLIS, pp. 315–342.

TOTO, R. (2019), ‘Forest Commons as a Model for Territorial Governance’, [in:] FINKA, M., JAŠŠO, M. and HUSAR, M. (eds.), The Role of Public Sector in Local Economic and Territorial Development. Innovation in Central, Eastern and South Eastern Europe, EAI/Springer Innovations in Communication and Computing. Cham: Springer, pp. 97–130. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-93575-1_7

TOTO, R., SHUTINA, D., DHRAMI, K., GJIKA, A., IMAMI, F. and SHTYLLA, A. (2015), Proposal on the Designation of the Development Regions of Albania, Tiranë: Co-PLAN. [Online] http://www.co-plan.org/en/designation-of-the-development-regions-of-albania/ [accessed on: 6.01.2021].

TOTO, R., SHUTINA, D., GJIKA, A. and ALIAJ, B. (2014), Rajonalizimi i Shqipërisë - Reforma qeverisëse, administrative dhe territoriale që i duhet Shqipërisë në nivel rajonal, Tirana: Co-PLAN and POLIS University. Supported by ADA and SDC, Albania.

VAN ZEBEN, J. (2019), ‘Polycentricity as a Theory of Governance’, [in:] VAN ZEBEN, J. and BOBIĆ, A. (eds.), Polycentricity in the European Union, Cambridge University Press, pp. 9–27. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108528771.003

WALTER, J. A. (2004), ‘Global civil society and the territorial polity: unfinished business’, [in:] COGHILL, K. (ed.), Integrated Governance: Linking Up Government, Business & Civil Society, Monash Governance Research Unit, pp. 1–10.