Abstract. The EU integration process contributes to influence the ongoing institutional changes in the Western Balkans. At the same time, the incremental inflow of Chinese capital in the region that followed the launch of the Belt and Road Initiative is progressively reshaping power relations there. This article sheds light on the interaction between these two processes, discussing whether the increasing inflow of resources may gradually erode EU conditionality and hinder the overall integration process. To do so, the authors draw on an extensive review of academic and policy documents and on selected expert interviews, upon which they compare the actions of the EU and China in the region.

Key words: Belt and Road Initiative, the Western Balkan Region, EU enlargement, China, conditionality.

During the last 20 years, China’s global political and economic influence has grown exponentially. The Chinese government undertook its so-called going-out strategy, which gained further concreteness with the launch of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013 and is expected to produce “a great impact on global economy through the integration of a large part of the world” (Sarker et al., 2018, p. 626). While some of its branches are already completed, the consequences of the BRI for Europe are still uncertain. The majority of Western states show a rather lukewarm attitude, while Eastern countries appear more open to engagement. This is especially true for the countries of the Western Balkan Region (WBR),[1] which see the resources channelled through the BRI as a potential way out of an unsatisfactory economic situation (World Bank, 2012).

At the same time, since the 2000s, the WBR countries have been engaged in a complex process that will eventually lead to their integration into the European Union (EU), and which influences them through the complex juxtaposition of conditionality logics (Schimmelfenning and Sedelmeier, 2005; Borzel et al., 2017; Cotella and Berisha, 2016; Berisha, 2018; Berisha and Cotella, 2021). While Slovenia and Croatia already achieved full membership, the integration of the other countries is proceeding at varying paces, as a consequence of a number of contextual contingencies that have at various moments in time altered the priorities of the actors involved (the global financial crisis, the progressive raise of euro-sceptic parties throughout Europe, and the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic and its unpredictable effects).

While the growing role that China plays in the WBR is undeniable, no assessment has been attempted yet of its impact on the integration of the region into the EU (Hake and Radzyner, 2019). In order to contribute to this direction, the authors build on the latest literature and policy documents, as well as on interviews conducted with selected stakeholders, to address and compare the role and influence of the EU and China in the WBR. Particular attention is devoted to the conditionality mechanisms that characterise the enlargement process, and to the impact that the BRI may have on them. After a brief introduction, a theoretical framework to understand EU conditionality in candidate countries is outlined, building on recent contributions in the field of European integration studies. The paper then focuses on the role that the EU plays in the WBR, discussing where the various countries stand along the process of integration. The fourth section illustrates the BRI’s vision and objectives, together with its implications for the WBR. The fifth section compares the role of the EU and China in the WBR through a number of interpretative lenses. Building on this comparison, some considerations are brought forward, reflecting on the potential implications that the increasing influence of China may have on EU conditionality in the region and, ultimately, on the region’s future integration into the EU.

Europeanisation studies traditionally concerned the impact of European integration on Member States (Olsen, 2002; Featherstone and Radaelli, 2003; Radaelli, 2004). However, a distinctive sub-area of research has recently emerged, focusing on the mechanisms through which the EU, by means of its enlargement process, influences the development of the rules and policies in candidate countries (Grabbe, 2002; Schimmelfennig and Sedelmeier, 2005; Vachudova, 2005; Balfour and Stratulat, 2011).

The theoretical framework adopted in these studies concerns the conditions under which the EU has an impact, and the mechanisms through which the impact is delivered (Schimmelfennig, 2011, 2012). These mechanisms are usually identified as depending on legal, economic, and cognitive conditionality (Cotella and Stead, 2011; Cotella, 2020; Cotella and Dabrowski, 2021), with the first two models being externally driven in comparison to the latter, which features a mix of social learning and lesson-drawing episodes (Schimmelfenning and Sedelmeier, 2005). Previous researches focusing on the Eastern Enlargement have demonstrated the dominance of incentive-based Europeanisation, and suggest the need to analyse its impact through the so-called external incentives model, which conceptualises accession conditionality as a bargaining game. The decisions of the actors involved in this game depend on self-interest and cost-benefit calculations. Accordingly, through conditionality mechanisms, the EU imposes target governments with its rules, through a strategy of reward-based reinforcement. The rewards vary from financial assistance to political entrustment, with full membership that constitute the final prize. Here conditionality acts as a function of a strategic calculation of the target government, which complies with EU rules only if the benefits of the reward outweigh domestic material and political costs (Zhelyazkova et al., 2018).

In EU enlargement towards Central and Eastern Europe, the effectiveness of conditionality mainly depended on membership incentive by the EU and rather low domestic adoption costs (Schimmelfennig et al., 2006; Schimmelfennig, 2007). Credible political membership enabled EU-enthusiast governments to pursue reforms, protecting them against the opposition from EU-sceptic actors (Schimmelfennig, 2005). When it comes to the WBR, more stringent accession criteria, lower credibility of membership, weaker administrative capacity, and higher domestic costs contributed to a slowing down of the pace. EU conditionality is showing a differential impact on rules’ adoption in the region. Capacity-building initiatives and intermediate rewards independent from the accession could explain the continuous progress of compliance in some Western Balkans countries. At the same time, the low absorption of EU funds and scarce institutional capacity may lead to frustration and eventually to an overall disaffection with EU logics.

Overall, in combination with ‘weaker’ conditionality mechanisms, other external factors may alter the strategic calculations of the national governments, and eventually drive their choices towards immediate and less burdensome benefits (Adams et al., 2011b). Our argument is that the growing volume of Chinese investments in the WBR may play a similar role, triggering alternative conditionality influences and, in turn, inducing domestic changes that are not necessarily compatible with those hoped for by the EU.

The integration of the WBR into the EU formally started in 1999, with the stipulations of the Stabilisation and Association Agreements (SAAs). Since then the process has continued at varying paces, with Croatia being the only country that effectively joined the EU while the others are still dealing with the transposition of the acquis communautaire (Table 1). Montenegro and Serbia initiated negotiations in 2012 and 2014, respectively. North Macedonia has been a candidate since 2005 and in 2009 the European Commission recommended opening negotiations. Albania started the analytical examination of the acquis in 2018. In March 2020, the Council finally decided to open accession negotiations, pending the fulfilment of a set of conditions. In July 2020, the Commission presented a draft negotiating framework to Member States. One year later, accession negotiations with Albania – and North Macedonia – have not yet been opened. Finally, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Kosovo are still at an early stage, with the former only having applied for membership in 2016, while the latter has not even apply yet.[2]

One must note that, when it comes to the influence exerted by the EU, the current enlargement strategy significantly enhanced its determinacy by framing its legal conditionality into a stricter and more coherent system of monitoring. Overall, the conditionality increased in terms of the breadth and scope of the reforms (Dimitrova, 2016). In contrast to previous enlargement rounds, in order to obtain EU membership, the candidate countries are now required not only to adopt the regulations and conditions set out in negotiating chapters, but also to have the most difficult acquis sections effectively implemented before accession.[3] An additional innovation concerns the change of the suspension clause, with the Commission that now may withhold its recommendation to open/close other chapters and adapt the associated preparatory work until sufficient progress under the ‘rule of law’ chapters is achieved. In summary, the conditionality applied to candidate countries through the new approach is formulated in such a way that the EU can exercise influence and steer reforms on issues that are politically highly sensitive. While this is expected to positively influence the compliance of Western Balkans countries, it has also led to a higher variation of determinacy of the EU conditions across the countries, with a lack of clarity in regards to the nature and scope of EU acquis, which has negatively affected consistency and impact (Pech, 2016).

| Steps | Agreements | Albania | Bosnia and Herzegovina | Montenegro | North Macedonia | Serbia | Kosovo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-adhesion Agreement | Potential Candidate | 2000 | 2003 | 2000 | 2000 | 2000 | 2000 |

| SAA | 2006–2009 | 2008–2015 | 2008 | 2001 | 2008 | 2014–2016 | |

| Application for EU membership | 2009 | 2016 | 2009 | 2004 | 2009 | n.a | |

| Candidate Status | 2014 | n.a. | 2010 | 2005 | 2012 | n.a. | |

| Screening | Analytical examination of the acquis | 2018 | n.a. | 2011 | 2018 | 2013 | n.a. |

| Negotiation | Chapters’ Discussion Period | n.a.a | n.a. | 2012– | n.a.b | 2015– | n.a. |

| Adhesion | Adhesion Treaty | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| Status | Member State | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a | n.a. | n.a. |

|

a In March 2020 the European Council endorsed the General Affairs Council’s decision to open accession negotiations with Albania and in July 2020 the draft negotiating framework were presented to the Member States. However, the negotiation process has yet to start. b The North Macedonia negotiation phase is under discussion. However due to some regional dispute with Bulgaria, the process is now in stand-by. |

|||||||

Source: own work based on Cotella and Berisha, 2019.

In parallel to the varying progress achieved in the implementation of the acquis, in the last three decades it has been possible to witness a progressive economic convergence between the EU area and the WBR. Moreover, according to official data (EEAS, 2017) growing economic ties have been established between the EU and the WBR, with the share trade volume reaching the value of 49.5 billion euros in 2017 (EEAS, 2017). Today, EU countries represent the region’s best trading partners, accounting for 73% of the total trade volume, a leading role that is also confirmed when considering inward Foreign Direct Investments. This data confirms that the EU has a strong influence on WBR economy, trade and investment system, and this economic interdependency is expected to consolidate further once full integration is achieved (EEAS, 2017). For this purpose, the EU has mobilised a set of funding schemes that target different sectors of WBR economy. These schemes contributed to strategic fields like transport infrastructure, energy production and efficiency, environmental protection, and greenfields.[4] In particular, since its introduction in 2007, the so-called Instrument of Pre-Accession (IPA) has delivered over 23 billion euros in the region (see Table 2), supporting regional cooperation and connectivity (Pinnavaia and Berisha, 2021).

When it comes to the 2021–27 programming period, according to the political agreement between the European Parliament and the Council on the new IPA III, the multi-annual financial framework will mobilise 14.2 billion euros to support economic convergence primarily through investments dedicated to inclusive growth, sustainable connectivity, and green and digital transition (EC, 2020). Moreover, a recent communication of the Commission (EC, 2020) indicated that IPA III will team up with the European Green Deal in promoting joint actions to tackle the challenges of green transition, climate change, biodiversity loss, excessive use of resources, and pollution. Importantly, apart from the territorial impacts produced through IPA’s funded actions, one should highlight that these tools, similarly to the pre-accession tools implemented in Central and Eastern Europe throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, have contributed to facilitating the consolidation of EU concepts, priorities, and procedures in the region (Cotella, 2007, 2014; Cotella et al., 2012; Adams et al., 2011).

| Sector | Albania | Bosnia and Herzegovina | Croatia | Montenegro | North Macedonia | Serbia | Kosovo | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007–2013 | Justice [%] | 18 | 18 | 9 | 17 | 12 | 16 | – |

| PA Reform [%] | 13 | 13 | 9 | 23 | 13 | 22 | – | |

| Transport [%] | 16 | 8 | 12 | 13 | 20 | 10 | – | |

| Energv. and Climate [%] | 18 | 16 | 15 | 8 | 18 | 19 | – | |

| Social Development [%] | 10 | 14 | 34 | 8 | 12 | 22 | – | |

| Agriculture and Rural development [%] | 22 | 5 | 21 | 18 | 17 | 6 | – | |

| Others [%] | 3 | 26 | 0 | 13 | 8 | 5 | – | |

| Total (M€) | 512 | 554 | 802 | 191 | 508 | 1.213 | 679 | |

| 2014–2020 | Democracy and rule of law [%] | 27 | 28 | – | 19 | 15 | 22 | 22 |

| Democracy and governance [%] | 16 | 8 | – | 11 | 11 | 15 | 14 | |

| Rule of law and fundamental rights [%] | 10 | 7 | – | 7 | 4 | 8 | 8 | |

| Competitiveness and growth [%] | 23 | 42 | – | 30 | 35 | 27 | 28 | |

| Environment, climate change, and energy [%] | 3 | 6 | – | 6 | 10 | 10 | 12 | |

| Transport [%] | 2 | 3 | – | 5 | 10 | 3 | 0 | |

| Competitiveness, innovation, agriculture, rural development [%] | 14 | 4 | – | 12 | 11 | 11 | 10 | |

| Education, employment, and social policies [%] | 5 | 2 | – | 8 | 4 | 4 | 6 | |

| Total (M€) | 1279 | 789,3 | – | 568,2 | 1217 | 3078,8 | 1204,2 |

Source: own work based on EU data (European Commission, 2015 and DG NEAR, 2018).

Since the turn of century, China has been expanding its influence worldwide (Pu, 2016). With this aim in mind, in 2013 it launched the so-called Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), aiming at promoting economic connectivity between China and the countries involved in the initiative.[5] Importantly, the BRI should not be regarded as a single megaproject, rather as a continuously growing initiative with a large portfolio of projects for rail, road, sea, and airport infrastructure, power and water links, real estate contracts, and, more recently, digital infrastructure (Sielker and Kaufmann, 2020). In this sense, it is seen as the most ambitious and economically relevant initiative ever undertaken, comparable only with the Marshal Plan launched by the United States after the Second World War.[6]

The reasons behind the BRI have been widely debated (Liu, 2015; Grieger, 2016; Djankov, 2016; Tonchev, 2017; Cai, 2017). On the one hand, the initiative was triggered by domestic market needs, where China in order to counteract the economic slowdown caused by its internal market reaching its limits is continuously looking for new markets (Pu, 2016; Cai, 2017). Geopolitical conditions also play a relevant role, with the BRI taking advantage of the swinging stability of the EU and the US’ retreat from a number of multilateral agreements under president Trump’s leadership.[7] As explicitly argued by Xi Jinping during the Peripheral Diplomacy Work Conference in 2013, the objective of China’s economic policy is to turn the country into a world economy pivot. At the same time, the future consequences of the BRI are subject to debate, as they will depend on the attitude that the various countries will adopt in response to the structured bilateral cooperation proposed by China. Despite the launch of the EU-China Strategy 2020, the EU has not yet managed to unite its member and candidate countries on a common position and the latter engage with China through a plethora of bilateral relationships.[8] This contributes to reinforce the Chinese influence in Europe beyond individual projects and geopolitical debates, especially in these Central and South Eastern European Countries that constitute the BRI’s main entry points (Maçães, 2018; Sielker and Kaufmann, 2020).

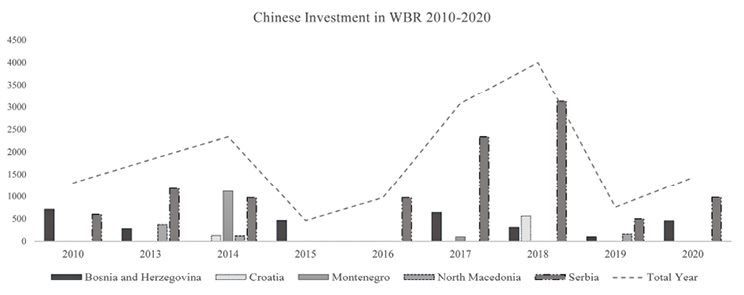

Central and Eastern Europe and WB countries signed their bilateral investment agreements with China in 2012, hoping it would support their recovery from the global economic crisis (Furceri and Zdzienicka, 2011). The “16+1 Cooperation” was then launched in 2013, to facilitate Chinese public and private investments aiming at the implementation of the BRI vision.[9] Benefiting from a strategic position between Eastern and Western Europe, the WBR has been attracting the majority of Chinese investments in key sectors such as heavy industry, energy, infrastructure, and logistics (Fig. 1).[10] At the same time, the cooperation also favoured the proliferation of multinational coordination platforms in different sectors like tourism, agriculture, infrastructure, logistic, energy, etc., aiming at facilitating cooperation among institutional and non-institutional actors (Jakóbowski, 2015).

Fig. 1. BRI-related investments in the WBR in the period 2010–2020 (in M$)

Source: own work based on AEI data (https://www.aei.org/china-global-investment-tracker/).

The 16+1 cooperation implements the vision of the BRI through the facilitation of trade investments and the acquisition of local businesses by Chinese companies. Altogether, this leads to an inflow of a growing volume of economic resources, aiming at increasing connectivity between the Chinese and the European markets. However, unlike the EU, China does not show interest in the socioeconomic and environmental impacts of its investments (Tonchev, 2017), and this raises a number of challenges (Liu, 2015). The implementation of the BRI in the WBR occurs through various financial institutions that act either through direct investments, aimed at the acquisition of local companies, or through open credit lines, used to develop strategic infrastructures (the Silk Road Fund, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, and the China CEE Investment Co-operation Fund). While a number of authors have reported a positive impact of these investments, they have also warned against the acquisition of national debt shares by Chinese state funds, which in the long term may negatively impact the involved countries (Stumvoll and Flessenkemper, 2020; Hurley et al., 2018).

In the 2011–2014 period, Chinese investments financed the construction, of, e.g., the Mihajlo Pupin Bridge in Belgrade, the Stanari thermal power plant in Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Bar-Boljare motorway in Montenegro (Jakóbowski, 2015), and the Balkan Silk Road from Piraeus to Budapest (Bastian, 2017). Detailed data provided by the American Enterprise Institute and The Heritage Foundation shows that, during the period of 2010–2020, China invested more than 16 billion dollars in the WBR, becoming one of the main investors in the region (see Table 3). The majority of the investments are dedicated to the transport and energy sectors, followed by technology, logistics, and utilities. It is particularly interesting to note that the contractors and credit providers are always Chinese companies, largely limiting the spill-over effects of the interventions on domestic economies.[11]

| Country | Year | Sector | Amount (M $) | Chinese Entity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serbia | 2010 | Transport | 260 | China Communications Construction |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 2010 | Energy | 710 | Dongfang Electric |

| Serbia | 2010 | Energy | 340 | Sinomach |

| Serbia | 2013 | Transport | 850 | China Communications Construction |

| Serbia | 2013 | Transport | 330 | Shandong Gaosu |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 2013 | Energy | 280 | Power Construction Corp |

| Macedonia | 2013 | Transport | 370 | Power Construction Corp |

| Montenegro | 2014 | Transport | 1.120 | China Communications Construction |

| Croatia | 2014 | Logistics | 130 | China National Building Material |

| Serbia | 2014 | Energy | 970 | Sinomach |

| Macedonia | 2014 | Transport | 120 | Power Construction Corp |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 2015 | Energy | 460 | Dongfang Electric |

| Serbia | 2016 | Transport | 230 | China Communications Construction |

| Serbia | 2016 | Energy | 230 | Sinomach |

| Serbia | 2016 | Technology | 170 | Huawei |

| Serbia | 2016 | Transport | 220 | Power Construction Corp |

| Serbia | 2016 | Metals | 120 | Hebei Steel |

| Serbia | 2017 | Energy | 720 | Sinomach |

| Serbia | 2017 | Energy | 210 | Shanghai Electric |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 2017 | Transport | 640 | Shandong Gaosu |

| Serbia | 2017 | Transport | 520 | China Communications Construction |

| Serbia | 2017 | Utilities | 310 | Sinomach |

| Serbia | 2017 | Transport | 350 | China Railway Engineering |

| Montenegro | 2017 | Energy | 100 | State Power Investment |

| Serbia | 2017 | Energy | 230 | Power Construction Corp |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 2018 | Energy | 310 | China Poly, Sinomach |

| Serbia | 2018 | Energy | 140 | Shanghai Electric |

| Croatia | 2018 | Energy | 220 | Norinco |

| Croatia | 2018 | Transport | 340 | China Communications Construction |

| Serbia | 2018 | Transport | 1.090 | China Railway Engineering, China Communications Construction |

| Serbia | 2018 | Metals | 650 | Zijin Mining |

| Serbia | 2018 | Transport | 990 | Shandong Linglong Tire |

| Serbia | 2018 | Other | 260 | China Communications Construction |

| Macedonia | 2019 | Real estate | 160 | Sinomach |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 2019 | Transport | 100 | State Construction Engineering, Power Construction Corp, China Communications Construction |

| Serbia | 2019 | Metals | 120 | Hebei Steel |

| Serbia | 2019 | Metals | 380 | Zijin Mining |

| Serbia | 2020 | Metals | 800 | Zijin Mining |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 2020 | Metals | 110 | Sinomach, China Nonferrous |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 2020 | Energy | 220 | China Energy Engineering |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 2020 | Energy | 120 | China Energy Engineering |

| Serbia | 2020 | Transport | 180 | Shandong Gaosu |

|

TOTAL |

16.180 |

|||

| a In the case of Albania there is no exact data. However, Chinese companies have acquired various local enterprises, e.g., the International Airport of Tirana (acquired by China Everbright Limited in 2016), and the Bankers Petroleum (by Chinese Geo-Jade in 2017). More information available at: http://al.china-embassy.org/eng/zgyw/t1484485.htm b To date, there has been no information about Chinese investments in Kosovo, and China has not officially recognised Kosovo as an independent state. |

||||

Source: own work based on the database of the American Enterprise Institute and The Heritage Foundation, https://www.aei.org/china-global-investment-tracker/.

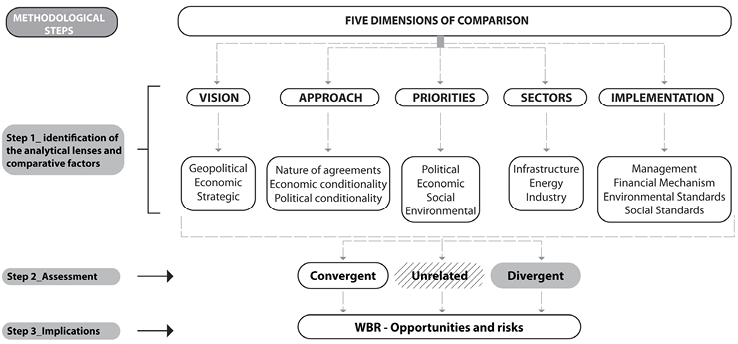

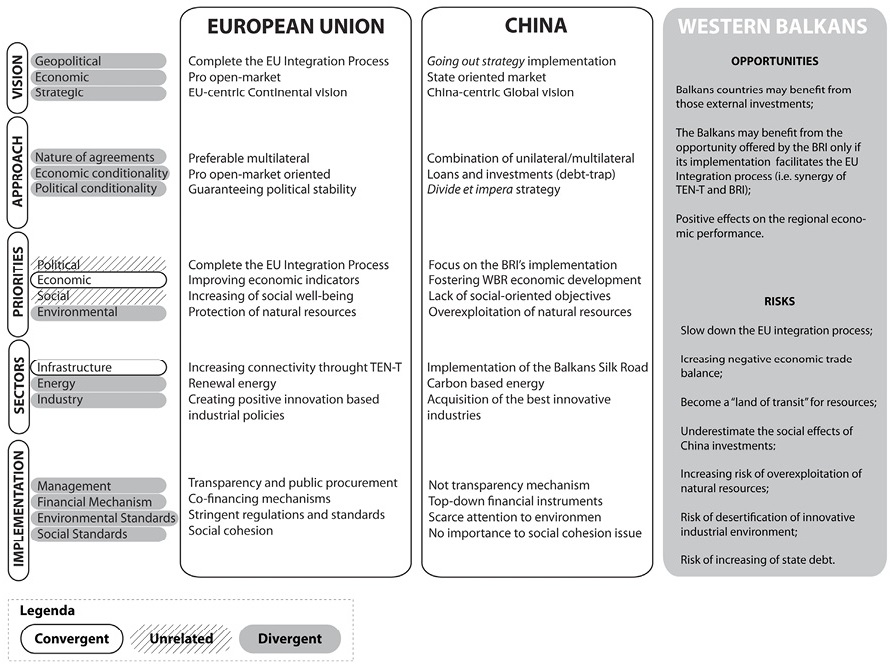

Despite the fact that during the recent Western Balkans Summit that was held in Sofia Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission, confirmed that the accession of the Western Balkans country remains a priority for the EU, how this process is affected by the increasing influence of China in the region remains unclear. In order to shed some light on the matter, this section attempts to offer a preliminary comparison of the attitudes adopted by the EU and China towards the WBR, according to three main steps (Fig. 2): (1) identification of the analytical lenses and comparative factors; (2) assessment and (3) implications.

Step 1 consists of the identification of the analytical lenses through which to explore the main similarities and differences that characterise the approaches of the EU and China towards the region. To offer more detail, five categories have been identified, each characterised by a number of comparative factors:

For each category, the roles of the EU and China were analysed and assessed as either convergent (with both players adopting similar strategies), divergent (with players adopting different, often opposite approaches) or unrelated (when there is no explicit relation between the action of the EU and China) (Step 2). Finally, the implications of the results of the analysis were presented, in terms of potential opportunities and risks for the WBR (Step 3).

Fig. 2. Methodological approach

Source: own work.

When considering the collected evidence, it becomes obvious that the attitudes of the EU and China towards the region largely differ (see Fig. 3). More specifically, in relation to their strategic visions for the region, a substantial divergence emerges. China’s ‘going out’ strategy is characterised by a centrally-driven approach whereby China establishes the main objectives and defines the rules of the game while the other countries are rarely included in the process. Conversely, the EU approach is founded on the vision to complete the economic and political integration of the continent. The WBR can be negatively influenced politically and economically as a consequence of the increasing tension between these two approaches, with China often acting according to divide et impera logic that may transform the region into a space of future geopolitical disputes (Bechev, 2020). In this perspective, the risk of turning the WBR into a transit corridor for goods and resources that remains poorly integrated into the EU is relatively high (Fruscione, 2021).

The second category focuses on the nature of the approach to the region adopted by each player. In this respect, the EU and China follow different paths in relation to the types of agreements they employ (multilateral versus bilateral), the mechanisms of resource distribution (co-financing and grants versus loans), and the direction of their political conditionality (political stability versus divide et impera) (Cotella and Berisha, 2019). The name 16+1 given to the cooperation platform is a symptom of how China conceives its prominent role in diplomatic relations. As recognised by Zweers et al. (2020), indeed, the ‘+1’ model self-establishes China as the only extra-regional participant in the cooperative scheme. Moreover, Chinese pragmatism in international relations usually favours bilateral over multilateral agreements, aiming at accelerating the implementation of the BRI. On the contrary, EU institutions favour complex multilateral arenas to create a broad consensus (Cotella and Berisha, 2019) and full socio-political awareness (Zweers et al., 2020). In this respect, Western Balkan countries risk being left within a number of bilateral negotiations that, while producing immediate direct economic benefits, may at the same time overshadow the importance of regional integration into the EU economic market (Mardell, 2020).

The third analytical category explores the short and long-term priorities of the EU and China in the region. In this respect, the EU and China display very different political, economic, social, and environmental attitudes. While the EU views sustainability in a holistic manner through the conditions and regulations specified in its Treaties, Chinese initiatives apparently pay less attention to the environmental impact and the overexploitation of natural resources they generate, nor do they seem concerned with their socioeconomic impact on local communities (Tonchev, 2017). According to Zweers et al. (2020), although not directly responsible for the side effects of their implementation (i.e. low environment standards or high corruption), the investments made by China may perpetuate local networks of patronage and corruption (Doehler, 2019). Despite that, both players converge on the importance of the economic growth of the region and its capacity to convey goods and resources towards wealthier EU regions (Cotella and Berisha, 2019).

In relation to the sectors targeted by the investments, the EU has explicitly argued in favour of a joint action towards a better connection between Europe and Asia. Both players are concerned with the region’s infrastructural development, and the Orient-East Med corridor planned by the EU coincides with the respective segment of the BRI. In this sense, the “Memorandum of understanding on establishing a Connectivity Platform between the EU and China” (2015) marks an opportunity to strengthen the synergies between the BRI and the Trans-European Networks. According to Zweers et al. (2020, p. 8), however, “China’s main interest in the Western Balkans relates not primarily to the region’s countries as such, but to their proximity to the EU, which is a major export market for China.” In this light, the acquisition of the Piraeus harbour, the Piraeus Europe–Asia Railway Logistics (PEARL) railway company, and a share of the Budapest train terminal constitute important indicators. A number of divergences emerge also in relation to the energy and industrial fields, with the EU promoting an eco-friendly and sustainable use of resources by financing renewable energy provisions and inviting local government to adopt circular economy logics, while China continuing to finance coal power plants such as the Kakanj plant in Bosnia and Herzegovina (Cotella and Berisha, 2019) or the Kostolac B3 coal power plant in Serbia (Zweers et al., 2020). At the same time, while the EU introduced funding programmes dedicated to stimulate research and innovation in the WBR, China rather acquires local innovative industries, thus hampering local development dynamics.

Fig. 3. Evidences of the EU and China’s attitudes towards the Western Balkans

Source: own work.

When it comes to the mechanisms of implementation, evident divergences emerge in relation to the nature of management, the quality of financial mechanisms, and the environmental and social standards that are adopted. As many researchers have reported (see Bechev, 2020; Zweers et al., 2020), the majority of Chinese projects activated in the WBR have been awarded to Chinese companies through rather opaque selection procedures, and concern Chinese contractors, suppliers, workers, and materials (EIB, 2018).[12] This drastically reduce the spill-over effect that this kind of interventions could activate. In contrast, the EU has established a procurement package that defines how tenders should be conducted, guaranteeing the principles of transparency and open access.

To conclude, the different attitudes of China and the EU towards the WBR carry both opportunities and risks. On the one hand, the region can benefit from two different sources of funds, which altogether increase the share of investments in the region, possibly contributing to enhancing regional competitiveness. One the other, however, this dual scenario may result in a progressive slow-down of the EU integration process, with the increase of economic inference of Chinese companies that may lead to a further overexploitation of natural resources, as well as to a progressive desertification of innovative entrepreneurship and, ultimately, to incremental indebting of Western Balkan countries with China and a consequential increased influence of the latter on the countries’ domestic politics.

There is a growing literature focusing on the implication of China’s action on the EU territory, in particular in relation to the future of EU integration (Bechev, 2020; Zweers et al., 2020). To contribute to this debate, the article has addressed the question of whether China could support the integration of the WBR into the EU or, conversely, become an agent of ‘de-Europeanisation’.

Despite the important progress made, the majority of WB countries are still struggling with the transposition of the acquis communautaire and the fulfilment of EU requirements (Berisha, 2018; Berisha et al., 2021 a, b, c). This process will take years since there is no chance of joining the EU before 2030 (European Commission, 2018), also as a consequence of the stricter requirements. At the same time, the role of China in the region has increased, as the EU Enlargement Commissioner Johannes Hahn that recently admitted in an interview how “the EU has overestimated Russia and underestimated China”. In this light, Stumvoll and Flessenkemper (2020) have highlighted that China’s growing momentum derives from the country’s ability to meet real investment needs in the region, a dynamic that the EU has been slow to acknowledge (Cotella and Berisha, 2019). At the same time, China’s influence has also grown as a consequence of the slowing down of the EU accession process in the aftermath of the global economic crisis and, more recently, of the refugee crisis, Brexit, and the COVID-19 pandemic. The credibility of EU membership is much lower than when compared with previous enlargement rounds.[13]

WBR countries that do not seem yet to possess the economic and administrative capacity to implement the EU accession requirements to a full extent, bearing at the same time higher adaption costs in comparison to the countries of Central and Eastern Europe. In particular, while the number of domestic veto players appears relatively low, EU political conditionality in most cases directly affects sensitive issues of national and ethnic identity and statehood (Freyburg and Richter, 2010; Subotic, 2010; Schimmelfennig, 2008; Noutcheva, 2009; Elbasani, 2013, Gordon et al., 2013).[14] Similarly, even EU-supportive governments may not be willing to reform institutions that operate currently in a way that is favourable to their political and electoral interests.[15] In this light, the lower domestic costs related to Chinese investments certainly offer an appealing perspective.

Overall, the BRI seems to have found a hole in the EU integration system, which it could easily fill. The growing volume of Chinese investments in the area demonstrates this and, while lowering the attractiveness of the EU intermediate rewards for the candidate countries, they at the same time may trigger alternative conditionality influences, in turn inducing domestic changes that are not necessarily compatible with those promoted by the EU. However, despite these potential pitfalls, the fact that Chinese investments do not come as an alternative to EU integration, allows WBR countries to pursue both ways at the same time – and they should do so.

While being fascinated by Chinese investments and their more pragmatic mechanisms, domestic authorities should continue to progressively metabolise EU rules and regulations in terms of transparency, quality standards, and public procurement. The EU will remain the biggest investor in the region and this path seems to ensure the highest long-term domestic benefits. More specifically, the conditions attached to EU rewards will strengthen the WBR internal coherence, and further consolidate its links with Europe. An additional momentum to this process may come from the EU’s increasing commitment towards the region, as recently argued in a number of official communications[16] and demonstrated by the introduction of the WBIF – IPF7 (Western Balkan Investment Framework – Infrastructure Project Facility). Overall, the EU should aim at accelerating the integration of the region, and the recent allocation of 9 billion euros dedicated to this goal is a step in the right direction (European Commission, 2020a). However, it should be acknowledged that, in the presence of further delays, the influence of China in the region is likely going to increase, potentially triggering episodes of de-Europeanisation in the long run.

ADAMS, N., COTELLA, G. and NUNES, R. J. (2011a), ‘Spatial planning in Europe: The interplay between knowledge and policy in an enlarged EU’, [in:] ADAMS, N., COTELLA, G. and NUNES, R. J. (eds.) (2011), Territorial Development, Cohesion and Spatial Planning: Knowledge and Policy Development in an Enlarged EU, London: Routledge, pp. 1–25. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203842973

ADAMS, N., COTELLA, G. and NUNES, R. J. (eds.) (2011b), ‘Territorial knowledge channels in a multi-jurisdictional policy environment. A theoretical framework’, [in:] ADAMS, N., COTELLA, G. and NUNES, R. J. (eds.) (2011), Territorial Development, Cohesion and Spatial Planning: Knowledge and Policy Development in an Enlarged EU, London: Routledge, pp. 26–55. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203842973

BALFOUR, R. and STRATULAT, C. (2011), ‘The democratic transformation of the Balkans’, European Policy Centre, 66, pp. 1–53.

BASTIAN, J. (2017), The potential for growth through Chinese infrastructure investments in Central and South-Eastern Europe along the Balkan Silk Road, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, Athens/London, pp. 1–62, retrieved from: https://www.ebrd.com/documents/policy/the-balkan-silk-road.pdf

BECHEV, D. (2020), ‘Making Inroads: Competing Powers in the Balkans’, [in:] FRUSCIONE, G. (ed.) (2020), The Balkans: old, new instabilities. A European region looking for its place in the world, ISPI - Istituto per gli studi di politica internazionale. DOI: 10.14672/55262477

BERISHA, E. (2018), The evolution of spatial planning systems in the Western Balkan Region. Between international influences and domestic actors (PhD dissertation), Politecnico di Torino, Italy, retrieved from https://iris.polito.it/retrieve/handle/11583/2707105/199191/Phd%20Dissertation_Erblin%20Berisha.pdf

BERISHA, E. and COTELLA, G. (2021), ‘Territorial development and governance in the Western Balkans’, [in:] BERISHA E., COTELLA, G. and SOLLY, A. (eds.) (2021), Governing Territorial Development in the Western Balkans – Challenges and Prospects of Regional Cooperation, Advances in Spatial Science, New York: Springer, pp. 23–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-72124-42

BERISHA, E., COTELLA, G. and SOLLY, A. (2021a), ‘Governing Territorial Development in the Western Balkans: Conclusive Remarks and Future Research Perspectives’, [in:] BERISHA, E., COTELLA, G. and SOLLY, A. (eds.) (2021), Governing Territorial Development in the Western Balkans – Challenges and Prospects of Regional Cooperation, Advances in Spatial Science, New York: Springer, pp. 357–381. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-72124-4_17

BERISHA, E., COTELLA, G. and SOLLY, A. (2021b), ‘Introduction: The Western Balkans Between Continuity and Change’, [in:] BERISHA, E., COTELLA, G. and SOLLY, A. (eds.) (2021), Governing Territorial Development in the Western Balkans - Challenges and Prospects of Regional Cooperation, Advances in Spatial Science, New York: Springer, pp. 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-72124-4_1

BERISHA, E., COTELLA, G. and SOLLY, A. (eds.) (2021c), Governing Territorial Development in the Western Balkans – Challenges and Prospects of Regional Cooperation, Advances in Spatial Science, New York: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-72124-4

BORZEL, T., DIMITROVA, A., and SCHIMMELFENING, F. (2017), ‘European Union enlargement and integration capacity: concepts, findings, and policy implications’, Journal of European Public Policy, 24, 2, pp. 1–20. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315147109-1

CAI, P. (2017), Understanding China’s Belt and Road Initiative, Lowy Institute for International Policy, pp. 1–22, retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/11540/6810

CHEN, D. (2014), ‘China’s «Marshall Plan» Is Much More’, The Diplomat, Retrieved from: http://thediplomat.com/2014/11/chinas-marshall-plan-is-much-more/

COTELLA, G. (2007), ‘Central Eastern Europe in the global market scenario: Evolution of the system of governance in Poland from socialism to capitalism’, Journal fur Entwicklungspolitik, 23 (1), pp. 98–124. https://doi.org/10.20446/JEP-2414-3197-23-1-98

COTELLA, G. (2014), ‘Spatial Planning in Poland between European Influences and Dominant Market Forces’, [in:] REIMER, M., GETIMIS, P. and BLOTEVOGEL, H. (eds.), Spatial planning systems and practices in Europe: A comparative perspective on continuity and changes, London: Routledge, pp. 255–277.

COTELLA, G. (2020), ‘How Europe hits home? The impact of European Union policies on territorial governance and spatial planning’, Géocarrefour, 94 (3). https://doi.org/10.4000/geocarrefour.15648

COTELLA, G., ADAMS, N. and NUNES, R. J. (2012), ‘Engaging in European spatial planning: A central and Eastern European perspective on the territorial cohesion debate’, European Planning Studies, 20 (7), pp. 1197–1220. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2012.673567

COTELLA, G. and BERISHA, E. (2016), ‘Changing Institutional Framework for Spatial Planning in the Western Balkan region. Evidences from Albania, Bosnia Herzegovina and Croatia’, EUROPA XXI, 30, pp. 41–57. http://doi.org/10.7163/Eu21.2016.30.3

COTELLA, G. and BERISHA, E. (2019), ‘From space in transition to space of transit. Risks and opportunities of EU and China investments in the Western Balkan Region’, Annual Review of Territorial Governance in the Western Balkans, 1, pp. 16–26, retrieved from: Annual-Review-of-Territorial-Governance-in-the-Western-Balkans.pdf (tg-web.eu)

COTELLA, G. and DABROWSKI, M. K. (2021), ‘EU Cohesion Policy as a driver of Europeanisation: a comparative analysis’, [in:] RAUHUT, D., SIELKER, F. and HUMER, A. (eds.), EU Cohesion Policy and Spatial Governance Territorial, Social and Economic Challenges, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, pp. 48–65. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781839103582

COTELLA, G. and STEAD, D. (2011), ‘Spatial planning and the influence of domestic actors: some conclusions’, disP – The Planning Review, 186 (3), pp. 77–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/02513625.2011.10557146

DIMITROVA, A. (2016), ‘The EU’s Evolving Enlargement Strategies: Does Tougher Conditionality Open the Door for Further Enlargement?’ Maximizing the integration capacity of the European Union: Lessons of and prospects for enlargement and beyond (MAXCAP) working paper series 30, retrieved from: http://userpage.fu-berlin.de/kfgeu/maxcap/system/files/maxcap_wp_30.pdf

DOEHLER, A. (2019), ‘How China Challenges the EU in the Western Balkans’, The Diplomat, retrieved from: https://thediplomat.com/2019/09/how-china-challenges-the-eu-in-the-western-balkans/

DJANKOV, S. (2016), ‘The rationale behind China’s Belt and Road Initiative’, [in:] DJANKOV, S. and MINER, S. P. (eds.), China’s Belt and Road Initiative, motives, scope and challenges, Institute for International Economics, PIIE Briefing 16–2, pp. 36–39, retrieved from: 17 The Rationale Behind China’s Belt and Road Initiative.pdf (cdrf.org.cn)

ELBASANI, A. (2013), ‘Europeanisation Travels to the Western Balkans: Enlargement Strategy, Domestic Obstacles and Diverging Reforms’, [in:] ELBASANI, A. (ed.), European Integration and Transformation in the Western Balkans: Europeanisation or Business as Usual? Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 1–9. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203386064

EUROPEAN COMMISSION (2015), The transformative power of enlargement, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. EU, retrieved from: https://publications.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/18a7ff84-fbba-11e5-b713-01aa75ed71a1/language-en

EUROPEAN COMMISSION (2018), A credible enlargement perspective for and enhanced EU engagement with the Western Balkans. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, retrieved from: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/communication-credible-enlargement-perspective-western-balkans en.pdf

EUROPEAN COMMISSION (2020a), Western Balkans: An Economic and Investment Plan to support the economic recovery and convergence. Brussels: Publications Office of the European Union, Belgium, retrieved from: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_20_1811

EUROPEAN COMMISSION (2020b), EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment. Brussels: Publications Office of the European Union, retrieved from: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_20_2541

EUROPEAN EXTERNAL ACTION SERVICE (2017), Factsheet: EU Engagement in the Western Balkans. Brussels: European External Action Service, retrieved from: https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage/29660/factsheet-eu-engagement-western-balkans_en

EUROPEAN INVESTMENT BANK (2018), ‘Infrastructure investment in the Western Balkan Region. A first analysis’, Economic – Regional Studies. Luxembourg: European Investment Bank, retrieved from: Infrastructure Investment in the Western Balkans: A First Analysis (eib.org)

FEATHERSTONE, K. and RADAELLI, C. (2003), The Politics of Europeanisation, Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/0199252092.001.0001

FREYBURG, T. and RICHTER, S. (2010), ‘National Identity Matters: The Limited Impact of EU Political Conditionality in the Western Balkans’, Journal of European Public Policy 17 (2), pp. 263–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760903561450

FRUCIONE, G. (2021), How China’s Influence in the Balkans is Growing, Rome: Italian Institute for International Political Studies, retrieved from: https://www.ispionline.it/en/pubblicazione/how-chinas-influence-balkans-growing-29148

FURCERI, D. and ZDZIENICKA, A. (2011), ‘The real effect of financial crises in the European transition economies’, Economics of transition, 19 (1), pp. 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0351.2010.00395.x

GIANDOMENICO, J. (2013), ‘EU Conditionality as a Transforming Power in Macedonia: Evidence from Electoral Management’, [in:] ELBASANI, A. (ed.), European Integration and Transformation in the Western Balkans: Europeanisation or Business as Usual? Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 70–84.

GORDON, C., KMEZIC, M. and OPARDIJA, J. (eds.) (2013), Stagnation and Drift in the Western Balkans: The Challenges of Political, Economic and Social Change, Berlin, Bern: Lang. https://doi.org/10.3726/978-3-0351-0581-0

GRABBE, H. (2002), ‘European Union conditionality and the Acquis communautaire’, International Political Science Review, 23 (3), pp. 249–268. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512102023003003

GRIEGER, G. (2016), One Belt, One Road (OBOR): China’s regional integration initiative, Brussels: European Parliamentary Research Service, retrieved from: One Belt, One Road (OBOR): China’s regional integration initiative – Think Tank (europa.eu)

HAKE, M. and RADZYNER, A. (2019), ‘Wester Balkans: Growing economic ties with Turkey, Russia and China’, BOFIT Policy Briefs, 1, retrieved from: Western Balkans: Growing economic ties with Turkey, Russia and China (helsinki.fi)

HURLEY, J., MORRIS, S. and PORTELANCE, G. (2018), ‘Examining the Debt Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative from a Policy Perspective’, CGD Policy Paper, 121, retrieved from: Examining the Debt Implications of the Belt and Road Initiative from a Policy Perspective (cgdev.org). https://doi.org/10.24294/jipd.v3i1.1123

JAKÓBOWSKI, J. (2015), ‘China’s foreign direct investments within the ‘16+1’ cooperation formula: strategy, institutions, results’, Centre for Eastern Studies, 191, retrieved from: OSW Commentary 191.

LE CORRE, P. (2018), ‘China’s Rise as a Geoeconomic Influencer: Four European Case Studies’, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. M-RCBG Associate Working Paper No. 104, retrieved from: China’s Rise as a Geoeconomic Influencer: Four European Case Studies – Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

LIU, Z. (2015), ‘Europe and the Belt and Road Initiative: Responses and Risks’, China’s Social Sciences Publishing House, retrieved from: Liu-ZuokuiEurope-and-Belt-and-Road-Initiative.pdf (geopolitika.hu)

MAÇÃES, B. (2018), Belt and road: A Chinese world order, London: Hurst Publishers.

MARDELL, J. (2020), China’s Economic Footprint in the Western Balkans, Berlin: Bertelsmann Stiftung, retrieved from: asia-policy-brief-chinas-economic-footprint-in-the-western-balkans-28c4d775834edcc469f4f737664f79f932d6f9a1.pdf (pitt.edu)

MÜFTÜLER-BAÇ, M. and ÇIÇEK, A.E. (2015), ‘A Comparative Analysis of the European Union’s Accession Negotiations for Bulgaria and Turkey: Who Gets in, When and How?’, MAXCAP, 7, retrieved from: http://userpage.fu-berlin.de/kfgeu/maxcap/system/files/maxcap_wp_07.pdf

NOUTCHEVA, G. (2009), ‘Fake, partial and imposed compliance: the limits of the EU’s normative power in the Western Balkans’, Journal of European Public Policy 16 (7), pp. 1065–1084. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760903226872

OLSEN, J. P. (2002), ‘The many faces of Europeanization’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 40 (5), pp. 921–952. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5965.00403

PECH, L. (2016), ‘The EU as a Global Rule of Law Promoter: the Consistency and Effectiveness Challenges` Asia’, Asia Europe Journal, 14 (1), pp. 7–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10308-015-0432-z

PINNAVAIA, L. and BERISHA, E. (2021), ‘The role of cross-border territorial development. Evidences from Albania’, [in:] BERISHA E., COTELLA, G. and SOLLY, A. (eds.) (2021), Governing Territorial Development in the Western Balkans – Challenges and Prospects of Regional Cooperation, Advances in Spatial Science, New York: Springer, pp. 309–332. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-72124-4_15

PU, X. (2016), ‘One Belt, One Road: Visions and Challenges of China’s Geoeconomic Strategy’, retrieved from: (29) (PDF) One Belt, One Road: Visions and Challenges of China’s Geoeconomic Strategy | Xiaoyu Pu - Academia.edu

RADAELLI, C. M. (2004), ‘Europeanisation: Solution or problem?’, European Integration Online Papers, 8 (16), pp. 1–26, retrieved from: http://eiop.or.at/eiop/texte/2004-016.htm

SARKER, M. N. I., HOSSIN, M. A., YIN, X. H. and SARKAR, M. K. (2018), ‘One Belt One Road Initiative of China: Implication for Future of Global Development’, Modern Economy, 9, pp. 623–638. https://doi.org/10.4236/me.2018.94040

SCHIMMELFENNIG, F. (2005), ‘Strategic calculation and international socialization: Membership incentives, party constellations, and sustained compliance in Central and Eastern Europe’, International Organization, 59 (4), pp. 827–860. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0020818305050290

SCHIMMELFENNIG, F. (2007), ‘European Regional Organizations, Political Conditionality, and Democratic Transformation in Eastern Europe’, East European Politics and Societies, 21 (1), pp. 126–141. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888325406297131

SCHIMMELFENNIG, F. (2008), ‘EU Political Accession Conditionality after the 2004 Enlargement: Consistency and Effectiveness’, Journal of European Public Policy, 15 (6), pp. 918–937. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501760802196861

SCHIMMELFENNIG, F. (2012), ‘EU External Governance and Europeanisation Beyond the EU’, [in:] LEVI-FAUR, D. (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Governance, Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199560530.013.0046

SCHIMMELFENNIG, F., ENGERT, S. and KNOBEL, H. (2003), ‘Costs, commitment and compliance: The impact of EU democratic conditionality on Latvia, Slovakia and Turkey’, Journal of Common Market Studies, 41 (3), pp. 495–518. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5965.00432

SCHIMMELFENNIG, F. and SEDELMEIER, U. (2005), The Europeanization of Central and Eastern Europe, Ithaca, Cornell University Press, retrieved from: http://hdl.handle.net/1814/2860

SIELKER, F. and KAUFMANN, E. (2020), ‘The influence of the Belt and Road Initiative in Europe’, Regional Studies, Regional Science, 7 (1), pp. 288–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2020.1790411

STUMVOLL, M. and FLESSENKEMPER, T. (2020), ‘China’s Balkans Silk Road: Does it pave or block the way of Western Balkans to the European Union?’, [in:] WAECHTER, M. and VEREZ, J. C. (eds.), Europe, between fragility and hope, NOMOS eLibrary, pp. 125–132. https://doi.org/10.5771/9783748909767-125

SUBOTIC, J. (2010), ‘Explaining difficult states. The problems of Europeanization in Serbia’, East European Politics and Societies, 24 (04), pp. 595–616. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888325410368847

TONCHEV, P. (2017), ‘China’s Road: into the Western Balkans’, European Union Institute for Security Studies, retrieved from: Brief 3 China’s Silk Road.pdf (europa.eu)

VACHUDOVA, A. (2005), ‘Europe undivided, Democracy, Leverage, and Integration After Communism’, The Washington Quarterly, 21, New York: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/0199241198.001.0001

WORLD BANK (2012), South East Europe Regular Economic Report N.3 – From Double Deep Recession to Accelerated Reforms. Poverty Reduction and Economic Management Unite Europe and Central Asia Region, retrieved from: http://hdl.handle.net/10986/26832

ZHELYAZKOVA, A., DAMJANOVSKI, I., NECHEV, Z. and SCHIMMELFENNIG, F. (2018), ‘European Union Conditionality in the Western Balkans: External Incentives and Europeanisation’, [in:] DZANKIC, J., SOEREN K. and KMEZIC, M. (eds.), The Europeanisation of the Western Balkans. A Failure of EU Conditionality?, Basingstoke: Palgrave, pp. 15–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91412-1_2

ZWEERS, W., SHOPOV, V., VAN DER PUTTEN, F. S., PETKOVA, M. and LEMSTRA, M. (2020), ‘China and the EU in the Western Balkans. A zero-sum game?’, Clingendael Report, Netherlands Institute of International Relations, retrieved from: https://www.clingendael.org/sites/default/files/2020-08/china-and-the-eu-in-the-western-balkans.pdf