Abstract. The aim of the paper is to evaluate alternative food networks (farmers’ markets and community gardens) in Slovak towns in order to determine the views of town self-governing authorities. Data was collected through a questionnaire sent to representatives of towns. The results have shown that only 39% of towns regularly organise farmers’ markets but, overall, 52% of towns support or plan to support their organisation. There are a total of 40 community gardens in 17 towns, mainly in the west of Slovakia. The paper discusses the ways in which Slovak towns support alternative food networks.

Key words: farmers’ markets, community gardens, Slovakia, town authorities.

Alternative models of consumption have been developed against the conventional model in which there is a longer supply chain between producers and consumers (producer → wholesale → retail → consumer). The aim of alternative consumption can be conceived as a supply chain in the form of producer → consumer. This type of supply chain is sometimes referred to as an alternative food network. In the paper we consider alternative food networks (AFNs) as a short production and distribution chain integrating the dimensions of spatial, economic, and social proximity (Barbera and Dagnes, 2016) in as few relations as possible. It is based on local, decentralised approaches that respect quality, health, freshness, traditional production techniques, and local identity. “Alternative (local) food systems are rooted in particular places, aim to be economically viable for farmers and consumers, use ecologically sound production and distribution practices, and enhance social equity and democracy for all members of the community” (Feenstra, 1997, p. 28). This local food system can be seen as building new producer/consumer alliances and creating experimental spaces to develop novel practices of food provision that are more in tune with their values, norms, and needs. The desire for higher values results from the reproduction and revaluation of local sources, and that result in food of distinct and better appreciated qualities (Roep and Wiskerke, 2012). AFNs represent a bipolar alternative to conventional agriculture that has strongly benefited from certain consumers’ preference for quality and a growing mistrust of standardised food (Kizos and Vakoufaris, 2011; Maye and Kirwam, 2010; Sage, 2003).

AFNs include a wide variety of initiatives such as farmers’ markets, box schemes, farm shops, community gardens, food cooperatives, and community-supported agriculture (Dansero and Puttilli, 2014; Spilková et al., 2016; Tregear, 2011). The paper focuses on two elements of AFNs, i.e. farmers’ markets and community gardens, because these two alternatives are the most common and popular forms of ANFs in Slovakia (Hencelová et al., 2020). Geography has recently shown significant interest in researching the problems of towns and consumption. Research into public space is valued when it increases the chances for unused and neglected public spaces to find use as the target of activist, ecological, and town-planning projects (Blazek and Šuška, 2017). The creation of AFNs affects the sustainability of towns. It also provides support for local communities and the solution for the social questions they face (Barbera and Dagnes, 2016; Gould and Lewis, 2016; Wachsmuth and Angelo, 2018). Food justice organisations create spaces (farmers’ markets, community gardens, cafés, and health food stores) inside towns. Its activism has positive environmental effects and contributes to the reduction of the urban heat island effect. However, the development of such green spaces in terms of food justice activism contributes to green gentrification which appeals to elite workers, more attractive housing offers, displacement of the middle and lower indigenous inhabitants, and a disruption of existing neighbourhood social relations (Alcon and Cadji 2020; Anguelovski et al., 2019).

The potential for AFNs in the post-socialist countries of Central and Eastern Europe depends on the interaction between various aspects (in history, geography, and urban planning) and the influence of the local post-socialist context (Spilková and Perlín, 2013). Although ANFs have existed in many post-socialist countries for more than two decades, the emergence of AFNs can be considered a modern phenomenon of the last 10 years (Hencelová et al., 2020). AFNs research remains in the background in Slovak geography and is still in its infancy. The intention of the authors is therefore to evaluate the support of town authorities of these two forms, the level of support and development of farmers’ markets and community gardens in Slovakia.

The aim of the paper is to evaluate AFNs (farmers’ markets and community gardens) in Slovak towns and to determine the views of town authorities on their organisation, establishment, operation, and their future potential. The paper seeks to answer the following research questions:

Q1: Do farmers’ markets and community gardens have a representation in Slovakia? The aim is to identify farmers’ markets and community gardens in the context of their development.

Q2: Do town authorities support the development of farmers’ markets and community gardens? The aim is to measure the level of support from town authorities.

The current dynamics in urban development in Slovakia and other post-socialist countries of Central and Eastern Europe is related to the historical factors that delayed development in the economic and material-spatial dimensions (Malý et al., 2020; Spilková and Perlín, 2013; Sikora-Fernandez, 2018). In Slovakia, as in Czechia, the 1990s saw rapid liberalisation of agriculture leading to numerous changes in the structure of production (Spilková and Perlín, 2013). Ideologically and centrally controlled urban planning practices were replaced by an uncoordinated exploitation of land resources and complicated property-law relations (Hirt, 2013). Schmidt et al. (2015), Sykora and Bouzanovsky (2012) have discussed issues such as spatial chaos, the shortages of funds, and depopulation. Post-socialist towns have a special structure that differs from that of other types of towns, one which is the result of the legacy of communist spatial planning. Šveda and Šuška (2014) have concluded that urban and suburban development in the post-socialist towns of Central and Eastern Europe can be interpreted as the consequence of a wide-ranging transformation processes in society, the transition to a market-oriented economy, and the region’s integration into global processes. AFNs are associated with benefits, from fresh food provision, through ecological, environmental, social and economic benefits (Schram-Bijkerk et al., 2018; Zoll et al., 2017). Residents make a positive contribution to the development of community gardens and farmers’ markets as modern locations of consumption, a fact which affects the social life of consumers (Renting et al., 2003).

When one considers urban gardening, self-provision and the need for productive land has had a long tradition in Slovakia. Towns were characterised by access to healthy food through allotment gardens in the past, which were formed at the urban fringes. Allotment gardens (“garden colonies” called in Slovakia) began to appear in the 1960s (Duží et al., 2014). The period of 1980–1990 saw a rapid development of allotment gardens, when traveling abroad and leisure activities were limited by the totalitarian regime. People spent a lot of their free time and holidays in the countryside. Duží et al. (2014) provided a review of home gardens – another traditional type of urban gardening in Slovakia. However, gardening in the towns changed rapidly. The political and social changes in the 1990s also affected the development of allotment gardens and their members. While at the beginning of 1957 the number of members of the Slovak Union of Gardeners was 1,800, in 1989 it exceeded 221,000 members, while in 2011 it had 80,648 members (the Slovak Union of Allotment and Leisure Gardeners, 2012). The extinction of colonies was caused not only by the degradation of the land, but also by the sale of land for the construction of residential or infrastructural projects. As Spilková et al. (2016) have claimed, while allotment gardens have been declining, new forms of AFNs have been emerging – farmers’ markets and community gardens. However, allotment gardens are still the prevailing form of urban agriculture, while community gardens emerge at random in towns. The members of colonies of the Slovak Union of Allotment and Leisure Gardeners can be found in as many as 44 districts of Slovakia (the Slovak Union of Allotment and Leisure Gardeners, 2012).

The protection of the urban environment and the need to regenerate destroyed (abandoned) lands are the problems of post-socialist towns in general (Duží and Jakubínský, 2013). The issues of towns that have stagnated affect the current existing gardening and food provision practices in towns. As Matacena (2016, p. 53) stated, AFNs occurred naturally in urban environments […] “since their aims of inclusion and re-localization are deeply intertwined with city governments attempts to realize a better management of local foodscapes, directed to build a healthier and more just local food system.” The author presented AFNs in the context of urban food policies and the adaptation of urban food strategies in towns. From a different point of view Barbera and Dagnes (2016) have discussed AFNs as a characteristic of self-organisation, with individuals acting locally and with insufficient involvement of institutions.

Production and consumption in the system of AFNs are closely interconnected, both economically and socially (Kitchin and Thrift, 2009). As a result of political and social changes since the 1990s, not only retail in Slovakia has changed, but also consumer behaviour in terms of consumption has transformed gradually (Križan et al., 2019). Šuška (2014) indicated the importance of the changes in consumer shopping habits during the socialist era. Consumer behaviour in Slovakia has ever since been affected by various globalisation trends. Changes in attitudes to shopping and consumption as global trends made shopping a full-fledged leisure activity (Spilková, 2012). Global homogenisation can be discussed in relation to consumption (Howes, 1996). It is a global convergence of tastes and consumer practices in societies. Many multinational private companies have an impact on consumption and can be termed the intermediaries of global consumption. Processes such as McDonalisation or Coca-globalisation have led to homogenisation, so that societies are becoming consumable (Križan and Bilková, 2019). In the first decade of the 21st century, a kind of a counter-current to the globalisation trend emerged, including various alternatives, which could be generalised by the term “sustainable consumption”. Alternative forms of retail and consumption were developed in opposition to globalisation. Consumer preferences increased for various forms of shopping involving the consumption of local healthy foods and the revival of social relations between consumers and producers through shopping at farmers’ markets or small, specialised shops (Spilková et al., 2013). Together with community gardens, as a place for people to grow their own food in the town, they have been one of the most significant trends of the last ten years. Many of the new trends relate to economic factors and marketing that are outside the scope of geographical research.

Slovakia is one of the post-communist countries of Central and Eastern Europe where AFNs have gradually emerged over the last 10 years (Hencelová et al., 2020; Škamlová et al., 2020). Interest in AFNs among Slovak consumers is clearly growing based on inspiration from consumption patterns in other countries (Hencelová et al., 2020). The conditions for the establishment and operation of AFNs are also related to town support. Therefore, the aim of this case study is to evaluate the actual situation in Slovak towns and present the experiences.

The questionnaire survey for towns was conducted in August 2019. Data was collected using an online questionnaire created using Google Forms and distributed via e-mail (cf. Jarosz, 2008; McClintock et al., 2016). It was sent to mayors and relevant employees of all the towns in Slovakia except Bratislava, which was excluded because the community gardens and farmers’ markets there had been analysed in detail in a previous research (Hencelová et al., 2020). No specific criteria were used for the selection of the towns. The questionnaire was sent to the towns which are defined in Slovak context in accordance with the Act No. 369/1990 Coll. on Municipal Establishment (The Act No. 369/1990 Coll. on Municipal Establishment). It was an electronic questionnaire survey completed by the respondents themselves (cf. Saunders et al., 2009).

The questionnaire was divided into two sections. The first section concerned community gardens and included questions about the number of community gardens in the town, the interest in implementing community garden projects, the town’s support and the fact of drafting development documents in respect to community gardens, and the town’s views on future measures related to community gardens. The second section concerned farmers’ markets, how often they were held, the conditions for such markets, and who organised them. This section also asked about the town’s support for organising such markets or for the emergence of such markets, and about the future of farmers’ markets in the town. We received responses from 130 town authorities in Slovakia (93%).

The analysis of the quantitative data was based on descriptive statistics and visualisation. We applied a cartographic representation of the analysed phenomenon, especially the method of figural characters. The technique of word cloud (tag cloud) was also used for visualising respondents’ answers. The primary attribute of the analysis was the mapping of town support and the measures for the implementation of farmers’ markets and community gardens. In the case of farmers’ markets, the research also investigated the frequency of such events and the character of the organiser.

The responses obtained in the questionnaire were transcribed in full and analysed in detail. Qualitative data sources gave us an understanding of the attitudes (positive, negative or neutral) expressed by the representatives of town authorities regarding AFNs. Any stated reasons for such attitudes were also recorded. The qualitative approach was used to evaluate the authorities’ perceptions, and to understand the problems and the way in which towns handle and manage the forms of AFNs (cf. Bonow and Normark, 2018).

In accordance with the ethics of social science research, the data was anonymised to preserve the anonymity of the respondents – representatives of town authorities (cf. Saunders et al., 2014). The reported opinions and quotations from representatives of town authorities were anonymised using a key in which towns were classified according to various criteria (see below).

Farmers’ markets can be characterised as modern places of consumption where food is sold directly from the producer to the consumer (Spilková et al., 2016). They support local craft workers and small producers, growers and farmers who care about the quality of their products. The products sold are of local or regional origin with minimal (or no) sale of foreign products. Consumers thus receive healthy and sustainable alternative products and reduce the environmental impact of transporting food to conventional supermarkets (Duram and Oberholtzer, 2010).

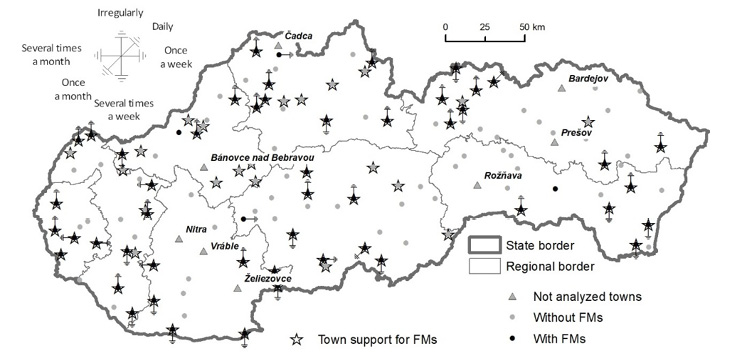

In Slovakia, markets are mainly organised in the traditional form in marketplaces or market halls. Such markets also offer other products besides food (clothing and footwear, consumer goods, etc.) Traders come from further afield and sell products that are not of local or regional origins (e.g. exotic fruit, saltwater fish, etc.) Consumers often confuse the concepts of a local marketplace and a farmers’ market. The incorrect interpretation of the terms is associated with the efforts to make marketplaces more attractive and the trend for AFNs – seeking something local and attractive. It can be said that the organisation of farmers’ markets in Slovakia is still at an early stage of development. The survey of town authorities in Slovakia indicates that farmers’ markets are organised in 51 towns (39% of the participating 130 towns) (Fig. 1). They tend to be organised as special events.

Fig. 1. Farmers’ markets and the frequency of their organisation analysed in Slovak towns in 2019

Source: own work.

Farmers’ markets in Slovak towns are usually held on an irregular basis (55%) or several times a week (31%). Most farmers’ markets are organised by private persons (57%). Self-governing authorities organise 24% of them, and non-profit organisations organise 14%. There are cases of cooperation in organising farmers’ markets. A total of 68 town authorities (52%) support the organisation of farmers’ markets. They are organised in various forms: “By decisions of the council, provision of suitable conditions”, “By a low price for renting a stall for the market”, “The town council has approved market rules for farmers’ markets”, “By providing space on land owned by the town”, or “Allocation of public areas, support for the accompanying programme by the town”. Towns provide space, financially support for the implementation of farmers’ markets, or assist in their promotion and marketing (e.g. media advertising): “We contact businesses and other private entities to ask them to participate and help in implementing farmers’ markets”. It should also be noted that the authorities in many towns (41% of the participating 130) show no interest in implementing farmers’ markets: “So far, no local farmers have asked us to organise markets”, “It’s still hypothetical. None of the local population has raised the issue”. In some cases, plans for farmers’ markets were not successful: “There was a plan to build a farmers’ building in the town where farm products could be sold but the potential implementer eventually pulled out.”.

The town authorities that did not support organising farmers’ markets (41%) offered various explanations: “No employee of the town has considered the question yet” (district town in the north of Slovakia); “To hold farmers’ markets, it would be necessary to amend the town’s by-laws” (district town in the south of Slovakia); “We don’t have any tradition of such events and so far nobody has asked for a permission for such an activity. There are only a few independent farmers in the local area and the town is in an industrial part of Slovakia” (district town in the north of Slovakia). Authorities felt no need to organise farmers’ markets for various reasons: “The town does not have a large population. It is more rural in character and from experience we know that farmers would not be very interested in such a market because they would not reach many customers. There is already a shop selling farm products in the town. The neighbouring village has two businesses selling animal products from farms and our people are used to going there. People can buy plant products on the town market during the summer or grow them in their own gardens. The town authority does not feel any need for the organisation of farmers’ markets” (district town in central Slovakia). Or there are statements of the type: “Our town is too small to organise farmers’ markets” (town in the east of Slovakia) or “It is not one of the town’s priorities!” (town in the east of Slovakia) or references to past experience: “In the past (2010–2014), the town organised farmers’ markets but they did not catch on because of the strict conditions laid down by the veterinary administration” (district town in the east of Slovakia) or “The range of products varies. For example, from widely available meat and dairy products to special products from beekeepers. The sale prices for commonly available products tend to be twice as high as for products of the same quality from retail chains” (town in the south of Slovakia). The most frequent arguments (31%) put forward by town authorities was the lack of interest among the local population or among the farmers in the region or the claim that “This type of market has no tradition in our micro-region” (town in the east of Slovakia) or “First somebody has to want to sell their products and then we can look for a place and method” (town in central Slovakia).

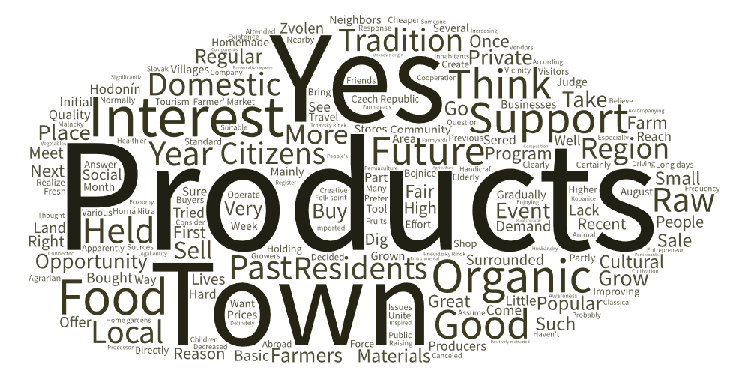

Town authorities tended to take a positive view of organising farmers’ markets in the future (Fig. 2): “Of course, people are getting more and more interested in buying fresh, local products, but the local farmers and producers do not sell their products in this way, or only in very small quantities, because of the many legislative obstacles and restrictions and the mass of red tape. If there was a permanent space with better rental conditions, there would probably be interest among the producers of local products. It would also be necessary to amend the legislation so that there would be fewer restrictions and more relaxed conditions” (district town in the east of Slovakia). “Yes, they have potential in the future, the townspeople are interested in them and the town has decided that it will organise them so that people don’t have to travel to nearby villages to get quality food and ingredients” (district town in the south of Slovakia).

Fig. 2. Respondents answers to the future of farmers’ markets

Source: own work.

The aim of a town in the west of Slovakia is to combine farmers’ markets with other social events in their towns: “Yes, but probably as part of the accompanying programme of other cultural and social events.” Town authorities see added value in farmers’ markets besides the sale of local foods: “People meet each other and talk together, children get creative ideas and the whole town feels like one community” (town in the west of Slovakia) or “Definitely, yes, it supports the region and it’s a way to increase people’s awareness of environmental issues and a chance to bring the community together” (district town in the north of Slovakia) or “Some of our people (especially older people and the people who live out in the country) see market days as a social event and a chance to meet their friends and neighbours” (district town in the west of Slovakia). There are towns where organisation duties are left for others: “Yes, but it very much depends on the involvement of the younger generation because at the moment things are in the hands of the older people” (town in the east of Slovakia) while others do not care about the future of organising farmers’ markets: “Farmers’ markets have no future in this town. At least 95% of the goods are generally available in several stores for a lower price” (town in the south of Slovakia).

The emergence of community gardens in Slovakia was preceded by urban gardening in allotment gardens, first established under the socialist regime in Czechoslovakia (cf. Spilková and Vágner, 2016). Community gardens are generally considered one of the alternative ways to improve local access to food and can be found mainly in urban contexts (Guitart et al., 2012). The modern phenomenon of establishing community gardens in Slovakia has become popular in both small towns (e.g. Modra) and larger urban centres (Banská Bystrica). In general, there is no evident correlation between population size and the emergence of community gardens. Bratislava, which currently has 13 working community gardens, can be considered a pioneer in the development of this phenomenon (Hencelová et al., 2021). Based on the consumption patterns in other developed countries, we can expect further growth in Slovakia.

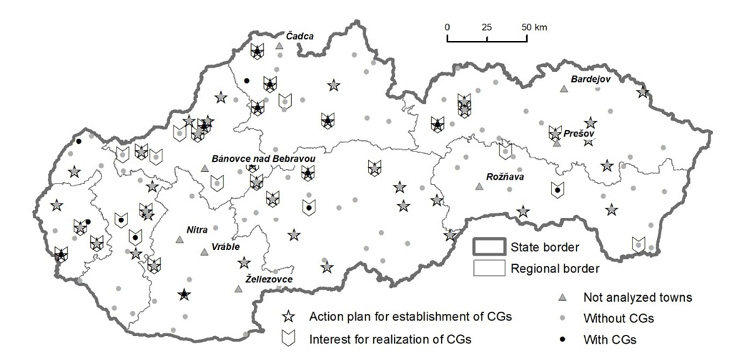

As 10 town authorities did not participate in the survey, it was necessary to conduct a search for community gardens through various websites. This research indicated that community gardens exist in four of the towns that did not participate in the survey (Rožňava, Prešov, Nitra, and Tvrdošín). The other non-participating towns (Vráble, Želiezovce, Galanta, Bardejov, Bánovce nad Bebravou, and Čadca) did not have community gardens at the time of the survey.

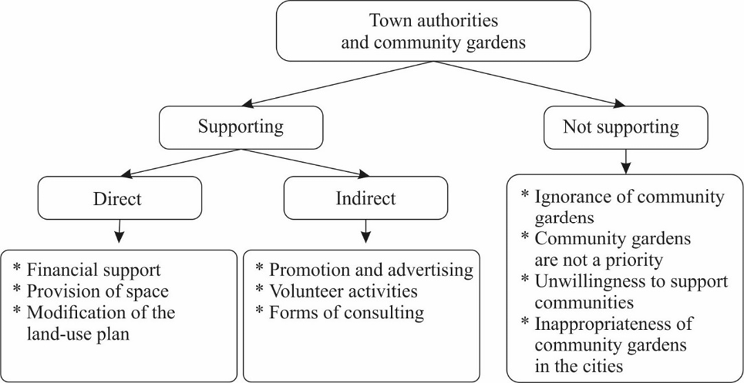

There are a total of 40 community gardens in 17 towns in Slovakia. These are mainly towns in the west of Slovakia, but similar developments can also be expected elsewhere. Thirty-one towns expressed interest in supporting the establishment of community gardens. Support takes a variety of forms: “Included in a project to regenerate the spaces between blocks of flats in the town supported by European funds” (district town in central Slovakia); “The town is able to provide land for community gardens, information for potential garden operators and expertise in preparing project” (district town in the west of Slovakia); “We have supported the creation of raised beds by production, volunteer work and financial support” (town in the north of Slovakia); “A grant request has been filed for a project supporting community gardens” (town in the west of Slovakia); “Advice, provision of land owned by the town” (town in the west of Slovakia). Town support can be divided into two categories. The first is direct support through the lease of space or through financial support. The second is indirect support through grant and project applications, the organisation of volunteering, and various forms of consulting. There are, however, some town authorities that do not take the initiative but are supportive towards community gardens: “As nobody has yet expressed an interest in such activities, the town has not provided any support. If anybody presents such a project, we will certainly support it” (district town in the west of Slovakia).

Not all town authorities were aware of community gardens: “This issue never came up in any meetings. I don’t think the councillors or the town management know about community gardens” (town in the west of Slovakia). There were also responses that were apathetic: “Community gardens are not an urgent problem in our town” (town in the west of Slovakia) or even negative: “We do not think that community gardens are appropriate in public space or on housing estates; where there are detached houses, people have fenced-off gardens; it is something that could be done in schools to teach children how to grow food and care for plants” (district town in the north of Slovakia). Yet another town in the north of Slovakia had incorporated the implementation of community gardens into its land-use plan. In total, 44 towns plan to implement measures supporting the establishment of community gardens in the future (Fig. 3) and land-use decisions for community gardens had been requested in 6 towns.

Fig. 3. Community gardens analysed in Slovak towns in 2019

Source: own work.

An important factor for the establishment of community gardens in Slovak towns is the initiative of local residents. Town authorities encounter such initiatives rarely but if there is interest, they are supportive. An initiative is not all it takes to implement a community garden, however, and towns encounter problems maintaining community gardens: “In our town we have received a request to establish a community garden but that it should all be managed and cared for by the town’s subsidised organisations. The citizens want to create a community garden, but they don’t want the responsibility of caring for it. It comes from a few citizens who may not be very well informed” (district town in the west of Slovakia).

It should be noted that the present research focused on towns in Slovakia, which are varied settlements established by political decisions. Many of them are made up of detached houses that have their own gardens. This may explain why some town authorities took a neutral view on community garden projects: “Our is a small town with many family houses with their own gardens. There are also three large allotment gardens that provide adequate space for gardening by people living in blocks of flats. The town authorities therefore see no need to establish community gardens” (town in central Slovakia) or “In small towns like ours, there are many individual gardens and most of the population has adequate space to grow fruit, vegetables on their own land or that of family members. There has so far been no requests or need to allocate space for this purpose. Should interest arise, we have plenty of space (in the town parks, etc.) to implement this type of plan” (town in central Slovakia).

In Slovakia, as in other developed countries, an increasing number of consumers prefer alternatives to conventional forms of consumption (Duží et al., 2017; Koopmans et al., 2017; Pearson et al., 2010). As a result, AFNs are developing, especially in the form of farmers’ markets and community gardens. The results of the survey evaluate AFNs in Slovakia – town support for the establishment of community gardens and farmers’ markets, the interest of town authorities in AFNs, and future steps for the development of these alternatives. The results provide data on the current distribution of farmers’ markets and community gardens, and support the creation of a database which has so far been lacking in institutional documentation in Slovakia.

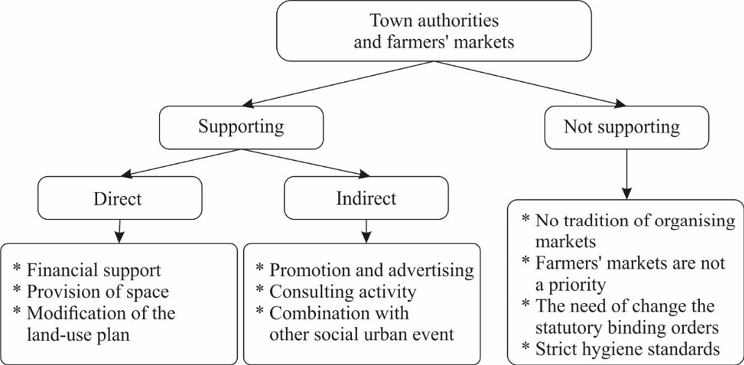

Slovak towns do not strongly support the trend of organising farmers’ markets although the trend of organising farmers’ markets has future potential in many towns. Support for the organisation of farmers’ markets may take various forms (Fig. 4): approval by the town council, provision of favourable conditions, provision of space, financial support or promotion and marketing support from the town authorities. There are towns (30%) where the authorities would like to combine farmers’ markets with other social events in the town, increase the awareness of environmental issues, and bring the community together as a means of increasing the social value of farmers’ markets. In this regard, it is necessary to consider the towns’ duty to provide services to people in the surrounding area. Some town authorities (41%) do not participate in the organisation of farmers’ markets nor do they envisage any such participation in the future. The reason for such a lack of interest may be the prejudice that such markets have no tradition in the town or that they are not a priority of the town. These town authorities also defend their lack of interest with reference to the need to amend by-laws or comply with strict hygiene standards.

Markets have a long tradition in Slovakia and their spheres of influence can be mapped geographically (Žudel, 1973). Town authorities therefore need to pay attention not just to the population of their own town but also consider the issue of farmers’ markets in broader spatial contexts or in the context of the hierarchical relationship between the town and its surrounding areas.

Fig. 4. Town authorities approach to the farmers’ markets

Source: own work.

Community gardens are still at an early stage of development in Slovakia (Hencelová et al., 2020). In general, there is no evident relationship between population size and the emergence of community gardens. Thirty-one towns (26%) expressed interest in supporting the establishment of community gardens. Town support can be divided into two categories (Fig. 5). The first is direct support by providing space or funding, the second is indirect support in the form of grant and project applications, the organisation of volunteering, and various forms of consulting. The problems for the future of community gardens include maintaining the condition of gardens and ensuring their proper operation. Despite that, the phenomenon of community gardens continues to grow and 44 town authorities (37%) have plans for the establishment of community gardens in the future. The arguments of town authorities (65%) against establishing community gardens based on the food-growing functions of gardens fail to consider the social function of community gardens. The social function of community gardens and the motivation they provide for community participation is more important than their productive function (Hencelová et al., 2020).

Fig. 5. Town authorities approach to the community gardens

Source: own work.

The case study highlights the state of support and the approach of town authorities to the development of AFNs. Consumers, town authorities and researchers have shown considerable interest in farmers’ markets and community gardens over the last decade. Our intent was to evaluate the approach of local authorities to farmers’ markets and community gardens, as they could be supported through their assistance. The connection of the analysed two forms concerns the possible development and support of an alternative (local) food system in Slovakia.

Farmers’ markets support and develop local economies and increase the income of local farmers and craftsmen in general. The overall social relations between consumers and farmers in Slovak towns would increase. Those towns which do not support organising farmers’ markets display a prejudice that such markets have no tradition in the town or that they are not a priority of the town. There are towns in Slovakia with plans to establish a community garden in the future. A town’s priority may be to support relations in local communities, food production, or to follow new trends in urban planning. Community gardens contribute to higher diversification and support green sustainability. Thus, the environmental approach should be another reason for their future establishing in Slovakia. Towns that oppose the establishment of community gardens may already have a tradition in urban agriculture, i.e. home gardens and allotment colonies.

The case study presents various solutions for a possible support of AFNs, community gardens, and farmers’ markets in Slovakia. Town authorities decide what kind of support they wish to offer. It is expected that AFNs will continue to develop in post-socialist towns. Therefore, the dynamics of the development of AFNs depends on the policy of town authorities. Our analysed approaches may be an inspiration for policy makers in other countries.

This case study is a pilot study in mapping farmers’ markets and community gardens as the markers of AFNs in Slovak geography. It presents new data for understanding town authorities’ perceptions and support for AFNs, as well as the possibilities for their future development.

Acknowledgments. This work was supported by the Slovak Research and Development Agency under contract No. APVV-16-0232, APVV-20-0302 and by VEGA 2/0113/19.

ALKON, A. H. and CADJI, J. (2020), ‘Sowing seeds of displacement: Gentrification and food justice in Oakland, CA’, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 44 (1), pp. 108–123. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12684

ANGUELOVSKI, I., CONNOLLY, J. J., GARCIA-LAMARCA, M., COLE, H. and PEARSALL, H. (2019), ‘New scholarly pathways on green gentrification: What does the urban «green turn» mean and where is it going?’, Progress in Human Geography, 43 (6), pp. 1064–1086. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132518803799

BARBERA, F. and DAGNES, J. (2016), ‘Building alternatives from the bottom-up: The case of alternative food networks’, Agriculture and Agricultural Science Procedia, 8, pp. 324–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aaspro.2016.02.027

BLAZEK, M. and ŠUŠKA, P. (2017), ‘Towards dialogic post-socialism: Relational geographies of Europe and the notion of community in urban activism in Bratislava’, Political Geography, 61, pp. 46–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2017.06.007

BONOW, M. and NORMARK, M. (2018), ‘Community gardening in Stockholm: participation, driving forces and the role of the municipality’, Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, 33 (6), pp. 503–517. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742170517000734

DANSERO, E. and PUTTILLI, M. (2014), ‘Multiple territorialities of alternative food networks: six cases from Piedmont, Italy’, Local Environment, 19 (6), pp. 626–643. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2013.836163

DURAM, L. and OBERHOLTZER, L. (2010), ‘A geographic approach to place and natural resource use in local food systems’, Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, 25 (2), pp. 99–108. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742170510000104

DUŽÍ, B. and JAKUBÍNSKÝ, J. (2013), ‘Brownfield Dilemmas in the Transformation of Post-Communist Cities: A Case Study of Ostrava, Czech Republic’, Human Geographies, 7 (2), pp. 53–64. https://doi.org/10.5719/hgeo.2013.72.53

DUŽÍ, B., FRANTÁL, B. and ROJO, M. S. (2017), ‘The geography of urban agriculture: New trends and challenges’, Moravian Geographical Reports, 25 (3), pp. 130–138. https://doi.org/10.1515/mgr-2017-0012

DUŽÍ, B., TÓTH, A., BIHUŇOVÁ, M. and STOJANOV, R. (2014), ‘Challenges of urban agriculture: highlights on the Czech and Slovak Republic specifics’, Current Challenges of Central Europe: Society and Environment, Praha: Karolinum, pp. 82–107.

FEENSTRA, G. (1997), ‘Local food systems and sustainable communities’, American Journal of Alternative Agriculture, 12, pp. 28–36. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0889189300007165

GOULD, K. A. and LEWIS, T. L. (2016), Green gentrification: Urban sustainability and the struggle for environmental justice, New York: Routledge.

GUITART, D., PICKERING, C. and BYRNE, J. (2012), ‘Past results and future directions in urban community gardens research’, Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 11 (4), pp. 364–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2012.06.007

HENCELOVÁ, P., KRIŽAN, F. and BILKOVÁ, K. (2020), ‘Klasifikácia a funkcia komunitných záhrad v meste (prípadová štúdia z Bratislavy)’, Sociológia, 52 (1), pp. 51–81. https://doi.org/10.31577/sociologia.2020.52.1.3

HENCELOVÁ, P., KRIŽAN, F., BILKOVÁ, K. and SLÁDEKOVÁ MADAJOVÁ, M. (2021), ‘Does visiting a community garden enhance social relations? Evidence from an East European city’, Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift-Norwegian Journal of Geography, 75 (5), pp. 256–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/00291951.2021.2006770

HIRT, S. (2013), ‘Whatever happened to the (post) socialist city?’, Cities, 32, pp. S29–S38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2013.04.010

HOWES, D. (ed.) (1996), Cross-cultural Consumption, London: Routledge.

JAROSZ, L. (2008), ‘The city in the country: Growing alternative food networks in Metropolitan areas’, Journal of Rural Studies, 24 (3), pp. 231–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2007.10.002

KITCHIN, R. and THRIFT, N. (2009), International encyclopedia of human geography, London: Elsevier.

KIZOS, T. and VAKOUFARIS, H. (2011), ‘Alternative Agri‐Food Geographies? Geographic Indications In Greece’, Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 102 (2), pp. 220–235. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9663.2010.00612.x

KOOPMANS, M. E., KEECH, D., SOVOVA, L. and REED, M. (2017), ‘Urban agriculture and placemaking: Narratives about place and space in Ghent, Brno and Bristol’, Moravian Geographical Reports, 25 (3), pp. 154–165. https://doi.org/10.1515/mgr-2017-0014

KRIŽAN, F. and BILKOVÁ, K. (2019), Geografia spotreby: úvod do problematiky, Bratislava, Univerzita Komenského v Bratislave.

KRIŽAN, F., BILKOVÁ, K. and HENCELOVÁ, P. (2019), ‘Maloobchod a spotreba’, [in:] GURŇÁK, D. et al., 30 rokov transformácie Slovenska. Bratislava, Univerzita Komenského v Bratislave, pp. 309–336.

MALÝ, J., DVOŘÁK, P. and ŠUŠKA, P. (2020), ‘Multiple transformations of post-socialist cities: Multiple outcomes?’ Cities, 107, 102901. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102901

MATACENA, R. (2016), ‘Linking alternative food networks and urban food policy: A step forward in the transition towards a sustainable and equitable food system?’ International Review of Social Research, 6 (1), pp. 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1515/irsr-2016-0007

MAYE, D. and KIRWAN, J. (2010), Alternative food networks, Sociology of Agriculture and Food Entry for Sociopedia.isa. Sage: Thousand Oaks.

MCCLINTOCK, N., MAHMOUDI, D., SIMPSON, M. and SANTOS, J. P. (2016), ‘Socio-spatial differentiation in the Sustainable City: A mixed-methods assessment of residential gardens in metropolitan Portland, Oregon, USA’, Landscape and Urban Planning, 148, pp. 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2015.12.008

PEARSON, L. J., PEARSON, L. and PEARSON, C. J. (2010), ‘Sustainable urban agriculture: stocktake and opportunities’, International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability, 8 (1–2), pp. 7–19. https://doi.org/10.3763/ijas.2009.0468

RENTING, H., MARSDEN, M. K. and BANKS, J. (2003), ‘Understanding alternative food networks: exploring the role of short food supply chains in rural development’, Environment and Planning A, 35 (3), pp. 391–411. https://doi.org/10.1068/a3510

ROEP, D. and WISKERKE, J. S. (2012), ‘On governance, embedding and marketing: reflections on the construction of alternative sustainable food networks’, Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 25 (2), pp. 205–221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10806-010-9286-y

SAGE, C. (2003), ‘Social embeddedness and relations of regard: alternative ‘good food’ networks in south-west Ireland’, Journal of Rural Studies, 19 (1), pp. 47–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0743-0167(02)00044-X

SAUNDERS, B., KITZINGER, J. and KITZINGER, C. (2014), ‘Anonymising Interview Data: Challenges and Compromise in Practice’, Qualitative Research, 15 (5), pp. 616–632. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794114550439

SCHMIDT, S., FINA, S. and SIEDENTOP, S. (2015), ‘Post-socialist sprawl: A cross-country comparison’, European Planning Studies, 23 (7), pp. 1357–1380. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2014.933178

SCHRAM-BIJKERK, D., OTTE, P., DIRVEN, L. and BREURE, A. M. (2018), ‘Indicators to support healthy urban gardening in urban management’, Science of the Total Environment, 621, pp. 863–871. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.11.160

SIKORA-FERNANDEZ, D. (2018), ‘Smarter cities in post-socialist country: Example of Poland’, Cities, 78, pp. 52–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2018.03.011

SPILKOVA, J. (2012), ‘The birth of the Czech mall enthusiast: the transition of shopping habits from utilitarian to leisure shopping’, Geografie, 117 (1), pp. 21–32. https://doi.org/10.37040/geografie2012117010021

SPILKOVÁ, J. et al. (2016), Alternativní potravinové sítě: Česká cesta, Praha: Karolinum.

SPILKOVÁ, J. and PERLÍN, R. (2013), ‘Farmers’ markets in Czechia: Risks and possibilities’, Journal of Rural Studies, 32, pp. 220–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2013.07.001

SPILKOVÁ, J. and VÁGNER, J. (2016), ‘The loss of land devoted to allotment gardening: The context of the contrasting pressures of urban planning, public and private interests in Prague, Czechia’, Land Use Policy, 52, pp. 232–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2015.12.031

SPILKOVÁ, J., FENDRYCHOVÁ, L. and SYROVÁTKOVÁ, M. (2013), ‘Farmers’ markets in Prague: a new challenge within the urban shoppingscape’, Agriculture and Human Values, 30 (2), pp. 179–191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-012-9395-5

SÝKORA, L. and BOUZAROVSKI, S. (2012), ‘Multiple transformations: Conceptualising the post-communist urban transition’, Urban Studies, 49 (1), pp. 43–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098010397402

ŠKAMLOVÁ, L., WILKANIEC, A., SZCZEPAŃSKA, M., BAČÍK, V. and HENCELOVÁ, P. (2020), ‘The development process and effects from the management of community gardens in two post-socialist cites: Bratislava and Poznań’, Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 48, 126572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2019.126572

ŠUŠKA, P. (2014), Aktívne občianstvo a politika premien mestského prostredia v postsocialistickej Bratislave, Bratislava: Geografický ústav SAV.

ŠVEDA, M. and ŠUŠKA, P. (2014), ‘K príčinám a dôsledkom živelnej suburbanizácie v zázemí Bratislavy: príklad obce Chorvátsky Grob’, Geografický časopis, 66 (3), pp. 225–246.

The Act No. 369/1990 Coll. on Municipal Establishment, https://portal.cor.europa.eu/divisionpowers/Pages/Slovakia.aspx.

The Slovak Union of Allotment and Leisure Gardeners (2012), Spravodajca, Výročie 55, Slovenský zväz záhradkárov 1957–2012, (1), pp. 6–11.

TREGEAR, A. (2011), ‘Progressing knowledge in alternative and local food networks: Critical reflections and a research agenda’, Journal of Rural Studies, 27 (4), pp. 419–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2011.06.003

WACHSMUTH, D. and ANGELO, H. (2018), ‘Green and gray: New ideologies of nature in urban sustainability policy’, Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 108 (4), pp. 1038–1056. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2017.1417819

ZOLL, F., SPECHT, K., OPITZ, I., SIEBERT, R., PIORR, A. and ZASADA, I. (2018), ‘Individual choice or collective action? Exploring consumer motives for participating in alternative food networks’, International Journal of Consumer Studies, 42 (1), pp. 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12405

ŽUDEL, J. (1973), ‘Trhové sféry na Slovensku v roku 1720’, Geografický časopis, 25 (4), pp. 299–312.