Abstract. The EU Cohesion Policy was observed to be marked by financial compliance problems due to a relatively high level of irregularities. This problem brings into question the issue of how to prevent such infringements of the rules applicable to EU expenditure. Against this backdrop, this article investigates how Poland worked to prevent irregularities during the 2014–2020 programming period. Specifically, the focus is on whether prevention measures enhanced Poland’s financial compliance performance. For this purpose, a novel model of ‘non-compliance financial rate’ (NCFR) is proposed and triangulated with qualitative findings from semi-structured interviews and documentary analysis, which has shown encouraging results that might be relevant also for other Member States.

Key words: Cohesion Policy, financial compliance, Poland, quality of government, Technical Assistance.

The EU Cohesion Policy (henceforth: CP) constitutes a relevant domain to investigate financial compliance in EU expenditures. Specifically, financial compliance stands for the conformity with financial rules applicable to the EU’s budgetary expenditure, such as public procurement or state aid (Mendez and Bachtler, 2017; Stephenson et al., 2020). Financial compliance is a crucial part of financial accountability, providing scrutiny and legitimacy of how EU Funds are spent, which is essential for the credibility of the European project (Davies and Polverari, 2011; Stephenson et al., 2020). Furthermore, CP is a “massive area of the budgetary expenditure” as financial allocations to this area exceed one-third of the EU’s seven-year budget (Hoerner and Stephenson, 2012; Mendez and Bachtler, 2017).

However, compliance problems have been reported in the case of CP as evidenced by a high number of irregularities found against other areas of the EU’s budgetary expenditure (Davies and Polverari, 2011; Mendez and Bachtler, 2011). Irregularities imply both fraudulent and non-fraudulent infringements of contractual obligations and rules applicable to EU expenditure (Mendez and Bachtler, 2017; Stephenson et al., 2020). Deficiencies in the administrative capacity of some Member States have been argued to be a critical cause for ineffective and incompliant ESI spending (Dotti, 2016; Incaltarau et al., 2020; Kuhl, 2020; Mendez and Bachtler, 2017). Notably, this problem concerns the Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries, such as Poland, where reforms in public administration did lag (Verheijen, 2007). Further, as reported by the European Court of Auditors (2019), compliance has not received enough attention due to the lack of formal requirements for Member States to assess fraud risk before adopting Operational Programmes. This requirement is critical to prevent money misuse in CP spending, thus ensuring compliance. Along these lines, detection and reporting irregularities constitute essential elements of the management and control system of ESI Funds (Kuhl, 2020; Stephenson et al., 2020). Next, should irregularities be detected in payment procedures, Member States’ authorities are responsible for applying financial corrections and recovering ineligible expenditures from beneficiaries (Kuhl, 2020; Stephenson et al., 2020). In other words, financial correction refers to the recovery of undue funding by withdrawing ineligible expenditures. Notwithstanding the importance of detection and reporting irregularities, there arises the problem of how to prevent such infringements.

Against this problematic backdrop, this article addresses the following research question: “Did measures aimed at preventing irregularities in the EU Cohesion Policy contribute to enhancing Poland’s financial compliance during the 2014–2020 programming period?”. In other words, the analysis seeks to show whether those measures contributed to stimulating Poland’s financial compliance performance in CP for the 2014–2020 programming period. Within this scope, the article uses a triangulation method combining content documentary analysis (i.e., policy reports), semi-structured interviews with key policymakers, and statistical data on irregularities. As a result, this approach enables the addressing of the research question posed.

This article is structured as follows. The next section reviews the literature in the field of CP, focusing on compliance. Section 3 presents the article contribution, its research approach, and how this approach is operationalised. Section 4 and Section 5 present and discuss the empirical analysis. The final section concludes with a reflection on the findings and limitations.

Research on EU law compliance has gained increased prominence over the last decade, investigating the underlying reasons for (non-)compliance, as well as analysing cross-country patterns (Börzel and Buzogány, 2019; Falkner et al., 2004; Falkner and Treib, 2008; Toshkov, 2012; Zhelyazkova et al., 2017). However, this research field has faced challenges in measuring compliance performance across Member States and policy sectors (Hartlapp and Falkner, 2009; Treib, 2014; Versluis, 2005). In addition to that, academics have had difficulties in proving clear-cut solutions for improving Member State compliance performance, and they mainly focused on the transposition of EU directives to measure compliance (Börzel and Buzogány, 2019; Falkner and Treib, 2008; Toshkov, 2012; Zhelyazkova et al., 2017).

Regarding the financial dimension of EU law compliance, CP has been a major focus of attention because of the substantive EU budgetary investments in this domain (Cipriani, 2010; Davies and Polverari, 2011; Kuhl, 2020; Mendez and Bachtler, 2017). To provide a deeper understanding of EU financial compliance in CP, Mendez and Bachtler (2017) examined financial correction patterns for the European Regional and Development Fund (ERDF) across Member States during the 2000–2006 programming period. This assessment dismantled a commonly argued ‘fault-line’ in compliance performance between the EU-10 and EU-15. On the contrary, the highest correction rates were found in Spain, Greece, and Ireland, while Latvia, Hungary, and Cyprus were among the top five best performers regarding financial compliance (Mendez and Bachtler, 2017). Although this assessment of financial compliance was narrowed to financial corrections, not every irregularity necessarily leads to a financial corrections imposition. Davies and Polverari (2011) showed yearly trends in the number of errors (i.e. incorrect project accounting or non-compliance with contractual and legal requirements), as detected by the European Court of Auditors. Notably, most yearly errors resulted from non-compliance with EU rules and ineligible spending (Davies and Polverari, 2011). Indeed, the level of errors during that period remained relatively high, indicating the necessity to reduce such financial compliance problems in CP expenditure.

The 2004 EU enlargement further increased the attention on CP performance due to the geographical shift of the Funds’ allocation in favour of the EU-10, of which Poland is the largest beneficiary (Ferry, 2013; Incaltarau et al., 2020; Manzella and Mendez, 2009). Indeed, CP has played a significant role, especially since the 2007–2013 programming period, attracting an extensive debate on its impacts and effects across CEE (Bachtler and McMaster, 2008; Dąbrowski, 2007; Dąbrowski et al., 2014; Ferry and Mcmaster, 2005). Regarding Poland, the main reasons for academic interests include the size of the country with notable interregional disparities, the post-communist transition, and the strategic relevance of the ESI Funds for the regional development. In general, scholars found a positive contribution of CP to Poland’s economic growth by reducing the unemployment rate and leading to a substantial extension and upgrade of the transport infrastructure (Czudec et al., 2019; Rokicki and Stępniak, 2018) which is a singular case, significantly different from other regions. A dynamic panel data model was applied to investigate the impact of EU funds on the progress made towards closing these development gaps. Among the analysed development gaps, only the structural gap was not reduced in the period 2004–2015. Studies have also revealed the different impact of Structural Funds on each category of development gaps: a positive impact on reducing the regional transport accessibility gap and the investment gap, but negative – on reducing the innovation gap. However, economic growth has not been sufficient to reduce economic gaps across Polish regions, especially along the regional East-West divide (Czudec et al., 2019; Dąbrowski, 2007; Dorożyński et al., 2014) which is a singular case, significantly different from other regions. A dynamic panel data model was applied to investigate the impact of EU funds on the progress made towards closing these development gaps. Among the analysed development gaps, only the structural gap was not reduced in the period 2004–2015. Studies have also revealed the different impact of structural funds on each category of development gaps: a positive impact on reducing the regional transport accessibility gap and the investment gap, but negative – on reducing the innovation gap. In this regard, CP was judged insufficient in addressing the (growing) interregional disparities because of the limited administrative capacity of national and regional authorities, hampering effective CP investments (Bachtler et al., 2014; Dotti, 2016; Incaltarau et al., 2020).

Summing up, it is crucial to ensure EU financial compliance to achieve proper CP expenditures, which is a precondition of effective spending (Cipriani, 2010; Kuhl, 2020; Mendez and Bachtler, 2017). Therefore, compliance performance must accompany implementation performance. Despite some contributions to EU financial compliance in CP, two ‘gaps’ exist. First, the previous CP research has little studied the implementation of measures to improve EU financial compliance. In general, anti-fraud measures, including efficient management and control system of ESI Funds, have gained importance in the broader debate on building administrative capacity with a growing emphasis on training for managing authorities, peer-to-peer networking, and the “Integrity Pacts” (Kuhl, 2020; Stephenson et al., 2020). Nonetheless, existing research has devoted limited attention to the effects of those measures. Second, CP studies have lacked a more strategic approach to assess EU financial compliance performance by triangulating qualitative and quantitative methods. In the following section, we present our approach aimed at addressing these ‘gaps’.

The article’s objective is to investigate whether measures aimed at preventing irregularities in CP spending implemented by Poland contributed to improving the financial compliance performance. Our case study focused on the 2014–2020 Polish Operational Programme ‘Technical Assistance’ (OP TA). Poland constitutes a significant case due to being the primary beneficiary of the ESI Funds since 2007. Specifically, in the 2014–2020 programming period, Poland received EUR 86 billion, amounting to nearly a quarter of all the ESI Funds. Moreover, since its pre-accession period to the EU, fraud and corruption in public expenditures have had remained a highly politicised issue among Polish authorities leading to a suspected misuse in CP expenditure. For these reasons, the OP TA is considered highly relevant to reinforce Poland’s administrative capacity in CP. Poland had a complex system of CP implementation due to the multiplicity of OPs (i.e., 6 national and 16 regional ones) co-financed by different ESI Funds. Furthermore, the East-West divide in Poland’s regional development triggered the necessity to reinforce effective management of the CP and investments in preventing irregularities were a key element for effective ESI Funds spending in 2014–2020. Therefore, the OP was conceived as an ‘umbrella’ for several relevant measures, encompassing those to prevent irregularities and stimulate effective CP performance.

Our analytical framework combined key concepts from three theories: rationalism, management, and constructivism. These particular theories differently explain why states (do not) comply with international obligations, such as EU law, and they, thus, provide different measures to solve compliance problems (e.g. Börzel and Buzogány, 2019; Chayes and Chayes, 1993; Tallberg, 2002; Versluis, 2005). Therefore, we applied these different theoretical approaches to the CP context to explore how Poland prevented irregularities in the ESI Funds (see Table 1). These (theoretical) measures served as the first indicator under the category OP TA (cf. Table 2).

| Theory | Measure to prevent irregularity | Relevance in the context of the EU Cohesion Policy |

|---|---|---|

| Rationalism | Controls (monitoring and auditing) | Financial controls are essential measures to fight/prevent fraud in ESI Funds. (Kuhl, 2020; Stephenson et al., 2020) |

| Management | Administrative capacity building | The administrative capacity-building measures are considered crucial to address compliance weaknesses. (Kuhl, 2020; Mendez and Bachtler, 2017) |

| Rules interpretation/ transparency | Guidelines for beneficiaries constitute relevant supplements to clarify actors’ responsibilities, protecting the EU’s financial interests. (Kuhl, 2020; Stephenson et al., 2020) | |

| Constructivism | Policy learning | Policy learning is considered a crucial element of the implementation and financial accountability, stimulating performance improvement. (Dotti, 2018; Stephenson et al., 2020) |

Source: own work.

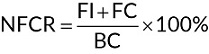

Second, three indicators to measure Poland’s financial compliance performance in CP were proposed, as depicted in Table 2. These indicators benchmarked the two last programming periods to verify Poland’s progress in financial compliance in CP. In addition, a (novel) ‘Non-Financial Compliance Rate’ (NFCR) indicator was developed to assess financial compliance performance. The NFCR is obtained as follows:

where:

FI = Total amount affected by Financial Irregularities,

FC = Total amount affected by Financial Corrections,

BC = Total Budgetary Contribution.

The NFCR is lower when a Member State complies more with applicable EU rules, namely the EU Regulations 2013/1303 and 2018/1046. Thus, the ideal value is zero, meaning a Member State is perfectly compliant. The analysis compared two programming periods to test whether Poland financial compliance has improved from 2007–2013 to 2014–2020.

| Category | Indicator |

|---|---|

| OP TA 2014–2020 | (1) Implementation of prevention measures |

| EU financial compliance assessment | (2) Number of fraudulent irregularities reported in 2007–2013 and 2014–2020 |

| (3) Number of non-fraudulent irregularities reported in 2007–2013 and 2014–2020 | |

| (4) Number of financial corrections imposed in 2007–2013 and 2014–2020 |

Source: own work.

This article combined qualitative and quantitative methods. The documentary analysis has enabled us to measure the first indicator. The relevant documents included guidelines by Polish authorities and the European Commission on combating irregularities in ESI Funds, and Annual Reports on the Protection of EU Financial Interests (PIF Reports), which contain statistical datasets.

The findings from the qualitative and quantitative analysis were triangulated with six interviews with key policymakers and experts. The interviewees were relevant policy officials from Poland’s Ministry of Development Funds and Regional Development (MDFRD), the EU Commission DG-REGIO’s Unit in charge of Poland, and the European Court of Auditors. Our analysis aims to provide a complete perspective to be triangulated with reports and data by combining standpoints from both EU officials and Poland’s civil servants.

The primary responsibility of ensuring EU financial compliance in CP lies with Managing Authorities (MAs), together with the ESI Funds beneficiaries, and involves preventing irregularities. In the 2014–2020 programming period, Poland undertook several measures under OP TA to reduce the likelihood of irregularities. Those measures encompassed a management and control system of the ESI Funds, fraud-awareness and training activities, and IT tools in public procurement. According to respondents from both DG REGIO’s and the Polish side, these particular measures were relevant to stimulate EU financial compliance.

The management and control system consisted of a three-level control mechanism, instead of the four-level mechanism common in other Member States. Specifically, Poland established a shared management system where the MDFRD was both the Managing Authority (MA) and the Certifying Authority (CA) (European Commission, 2010). Thus, the first level was both the MA and CA, while the second level was established as Auditing Authority (AA), and the EU Commission acted as the third, supreme level. Those control mechanisms encompassed independent, complementary processes of verifying ESI Funds expenditure. As explained by both the EU Commission and Polish officials, the primary control and management mechanisms were undertaken by the Polish side. They involved annual audits, year-round monitoring, and inspections of payment claims for projects co-financed with the ESI Funds. Those inspections were relevant to prevent irregularities, thus enabling an effective verification of submitted documents for project co-financing, and in turn eligibility of expenditures (European Commission, 2019; Ministry of Investment and Development, 2018a). Further, some Polish respondents stressed “very good and continuous cooperation” between the MA and the AA regarding inspections of eligible ESI expenditure. The latter “regularly audited” the management and control system to check its compliance with relevant EU and national rules (Ministry of Investment and Development, 2018; interviews 4 and 5). Summing up, those management and control measures served as ‘rationalist’ anti-irregularities measures.

The primary objective of fraud-awareness and training activities implemented by Poland was to minimise the risk of irregularities, particularly those of fraudulent nature (European Commission, 2015). These activities targeted MA’s staff and beneficiaries. They encompassed different aspects of fraud prevention, such as interpreting relevant financial rules, MA’s guidelines issued to beneficiaries, and annual bilateral meetings between the MA and beneficiaries. Specifically, the bilateral meetings were relevant to beneficiaries to explain how to avoid irregularity-related mistakes. Similarly, bilateral, regular cooperation meetings were held jointly by the MA and DG REGIO. Interviewees identified all these bilateral meetings as particularly relevant to discuss irregularity-related matters.

Furthermore, the MA staff participated in the Working Group for irregularities in CP, as well as in national and European conference series on “Control and irregularities in the spending of resources from Structural Funds and the Cohesion Fund” (European Commission, 2015; Ministry of Investment and Development, 2018a). Those activities enabled the exchange of knowledge and experience, contributing to further improvements in irregularities prevention (Ministry of Investment and Development, 2018; interviews 2 and 5). In addition to that, the MA implemented the Government Anti-Corruption Programme, whose primary measure was a successive improvement of a system for countering corruption threats (European Commission, 2015; Ministry of Investment and Development, 2018a). Finally, training, workshops and conferences played a relevant role in raising awareness regarding fraud and exchanging best practices to prevent irregularities (European Commission, 2014; Ministry of Investment and Development, 2018; interview 4). Thus, those activities enabled the MA and beneficiaries to ‘learn’, which stimulated administrative capacity-building.

In conclusion, those fraud-awareness and training measures served as ‘management measures’ boosting Poland’s administrative capacity. Furthermore, those activities constituted ‘constructivist’ measures facilitating policy learning, thus, exchanging knowledge and best practices to avoid irregularities-related mistakes.

IT tools were fundamental in preventing irregularities, as some respondents reported. For instance, the MA established and launched a ‘Competition Database’ intended for ESI Funds beneficiaries. The Competition Database constituted an IT tool for implementing competition rules regarding the eligibility of expenditure under ESI programmes in 2014–2020 (European Commission, 2017, p. 54). Notably, that IT tool served as a fraud prevention measure ensuring compliance with competition and public procurement rules, specifically, this tool was effective for those irregularities not covered by the Public Procurement Act (European Commission, 2017; Ministerstwo Funduszy i Rozwoju Regionalnego, 2015). Furthermore, the Competition Database was a relevant control tool providing greater transparency of those relevant rules and public scrutiny.

To conclude, the IT tool concerned served as two types of measures. First, it was a ‘rationalist’ measure considering its inspection purpose. Second, it was a ‘management’ measure to facilitate public procurement rules, interpretation, and transparency.

Table 4 presents Poland’s financial compliance performance in CP for two programming periods, namely 2007–2013 and 2014–2020.

| INDICATOR | PERIOD | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Unit | 2007–2013 | 2014–2020 | |

| Amount of fraudulent irregularities reported in 2007–2013 and 2014–2020 (Indicator 2 in Table 2) | (mn EUR) | € 422.41 | € 45.70 |

| Amount of non-fraudulent irregularities reported in 2007–2013 and 2014–2020 (Indicator 3 in Table 2) | (mn EUR) | € 1,318.93 | € 121.99 |

| Total Irregularities (Indicator 2+3) | (mn EUR) | € 1,741.35 | € 167.69 |

| Amount of financial corrections imposed in 2007–2013 and 2014–2020 (Indicator 4 in Table 2) | (mn EUR) | € 621.19 | € 659.50 |

| Total budgetary contribution | (mn EUR) | € 66,907.18 | € 76,345.21 |

| NFCR (Indicators (2+3)/4) | 3.54 | 1.08 | |

Source: European Commission, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020; D.-R. European Commission, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, own work; O. European Commission, 2020.

First, in each programming period, non-fraudulent irregularities significantly exceeded fraudulent ones. Those irregularities did not necessarily result from ineligible expenditures but, for instance, ‘unintentional’ mistakes in documents. Second, lower numbers of both fraudulent and non-fraudulent irregularities were reported under 2014–2020 against 2007–2013. Both findings confirm the results emerging from the above section about the effectiveness of prevention measures on Poland’s financial compliance performance. According to both institutional documents and interviews, those prevention measures were identified as the primary source of this improvement.

However, in 2014–2020, CP Funds spending by Poland were more affected by financial corrections imposition against 2007–2013. The reason behind this phenomenon was that, under the shared management, the MA was expected to identify irregularity and impose corrections before a payment was approved to reduce the number of ineligible expenditures. This ex-ante mechanism significantly reduced non-compliance. Furthermore, only the irregularities above EUR 10,000 were reported to the European Commission, which imposed financial corrections to enforce compliance with EU financial rules (Ministry of Investment and Development, 2018b). Finally, as a result of annual audits, the EU Commission was empowered to impose financial corrections if the Polish MA and AA authorities did not detect the irregularities.

Although compliance covers all irregularities, a distinction between a missing document and a fraudulent action must be carefully made (Interview 6). Not every financial correction is imposed because of fraud, as shown by lower fraud contribution in 2014–2020 against 2007–2013. This substantial amount of financial corrections imposed in 2014–2020 could have resulted from different reasons, such as ex-ante controls or ‘administrative’ irregularities (e.g., improper configuration of documents or ineligible claim for reimbursement of items). All these findings demonstrate progress in Poland’s financial compliance performance in CP because fewer ESI Funds were affected by ineligibly spent expenditures. Lastly, NFCR was considerably lower in 2014–2020 when compared to 2007–2013. This cumulative finding demonstrates that fewer CP expenditures were affected by ineligible spending in 2014–2020 compared to the previous period. Thereby, this indicates Poland’s significant progress in financial compliance performance in CP.

To sum up, the findings presented throughout this section constitute relevant evidence on the improved EU financial compliance performance in Poland. Thus, the anti-irregularities measures concerned have indeed contributed to improving Poland’s compliance performance in CP.

“Compliance in terms of legality and regularity is a precondition of good spending,” an interviewee reported to us. This statement perfectly sums up the significance of EU financial compliance in CP. These findings showed that prevention measures contributed to Poland’s financial compliance performance in CP. First, as our analysis demonstrated, there is no single measure preventing irregularities. Instead, various ones (i.e. ‘rationalist,’ ‘managerial,’ and constructivist’) need to complement one another to improve compliance performance. Our findings showed that the amount of non-compliant CP expenditures reduced in 2014–2020 compared to the previous programming period. Therefore, Poland can be considered a successful case of improving its financial compliance performance in CP.

Second, the cooperation between multiple actors at Poland’s national level and the EU level was found to stimulate EU financial compliance. Thereby, against the previous research identifying adverse effects of the shared management on ensuring compliance (Cipriani, 2010; Stephenson et al., 2020), this system may actually enhance Member State financial compliance performance in CP if an integrated, multidimensional approach is adopted to prevent irregularities. Nonetheless, further research comparing Member States and sectors should be conducted to investigate such a relationship.

The main article limitation is the focus on a single country. In contrast, comparison with other Member States, especially those that joined the EU after 2004, might be relevant to offer a more comprehensive perspective. Further, a benchmark with other policy fields (e.g. the Common Agricultural Policy) regarding EU financial compliance assessment might provide a deeper understanding of this topic.

BACHTLER, J. and MCMASTER, I. (2008), ‘EU Cohesion Policy and the Role of the Regions: Investigating the Influence of Structural Funds in the New Member States’, Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 26 (2), pp. 398–427. https://doi.org/10.1068/c0662

BACHTLER, J., MENDEZ, C. and ORAŽE, H. (2014), ‘From Conditionality to Europeanization in Central and Eastern Europe: Administrative Performance and Capacity in Cohesion Policy’, European Planning Studies, 22 (4), pp. 735–757. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2013.772744

BÖRZEL, T. A. and BUZOGÁNY, A. (2019), ‘Compliance with EU environmental law. The iceberg is melting’, Environmental Politics, 28 (2), pp. 315–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2019.1549772

CHAYES, A. and CHAYES, A. H. (1993), ‘On compliance’, International Organization, 47 (2), pp. 175–205. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818300027910

CIPRIANI, G. (2010), The EU budget: Responsiblity wihtout accountability?, Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS): Brussels.

CZUDEC, A., KATA, R. and WOSIEK, M. (2019), ‘Reducing the development gaps between regions in Poland with the use of European Union Funds’, Technological and Economic Development of Economy, 25 (3), pp. 447–471. https://doi.org/10.3846/tede.2019.9483

DAVIES, S. and POLVERARI, L. (2011), ‘Financial Accountability and European Union Cohesion Policy’, Regional Studies, 45 (5), pp. 695–706. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2010.529118

DĄBROWSKI, M. (2007), Implementing Structural Funds in Poland: Institutional Change and Participation of the Civil Society, 2, p. 21.

DĄBROWSKI, M., BACHTLER, J. and BAFOIL, F. (2014), ‘Challenges of multi-level governance and partnership: Drawing lessons from European Union cohesion policy’, European Urban and Regional Studies, 21 (4), pp. 355–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776414533020

DOROŻYŃSKI, T., ŚWIERKOCKI, J. and URBANIAK, W. (2014), ‘The Use Of EU Structural Funds By Enterprises In The Lodz Region’, Comparative Economic Research. Central and Eastern Europe, 16 (4), pp. 79–99. https://doi.org/10.2478/cer-2013-0029

DOTTI, N. F. (ed.) (2016), Learning from implementation and evaluation of the eu cohesion policy. Lessons from a research-policy dialogue, RSA Research Network on Cohesion Policy.

DOTTI, N. F. (ed.) (2018), Knowledge, Policymaking and Learning for European Cities and Regions. From Research to Practice, Edward Elgar Publishing.

EUROPEAN COMMISSION (2010), The control system for Cohesion Policy. How it works in the 2007–13 budget period, Office of Official Publications of the European Union.

EUROPEAN COMMISSION (2014), Fraud risk asssessment and effective and proportionate anti-fraud measures, Brussels: European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docgener/informat/2014/guidance_fraud_risk_assessment.pdf

EUROPEAN COMMISSION (2015), Commission Staff Working Document. Implemention of Article 325 TFEU by the Member States in 2014. Protection of the European Union’s financial interests—Fight against fraud 2015 Annual Report, European Commission.

EUROPEAN COMMISSION (2017), Commission Staff Working Document. Implementation of Article 325 TFEU by the Member States in 2016. Protection of the European Union’s financial interests—Fight against fraud 2016 Annual Report, European Commission.

EUROPEAN COMMISSION (2019), Commission Staff Working Document. Implementation of Article 325 TFEU by the Member States in 2018. 30th Annual Report on the Protection of the European Union’s financial interests—Fight against fraud—2018, European Commission.

EUROPEAN COMMISSION, D.-E. (2014), 2013 Annual Activity Report: Annexes [Annual Activity Report 2013 – Annexes], European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/activity-report-2013-dg-empl-annex_march2014_en.pdf

EUROPEAN COMMISSION, D.-E. (2015), 2014 Annual Activity Report: Annexes [Annual Activity Report 2014 – Annexes], European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/activity-report-2014-dg-empl-annex_august2015_en.pdf

EUROPEAN COMMISSION, D.-E. (2016), 2015 Annual Activity Report: Annexes [Annual Activity Report 2015 – Annexes], European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/activity-report-2015-dg-empl-annex_april2016_en.pdf

EUROPEAN COMMISSION, D.-E. (2017), 2016 Annual Activity Report [Annual Activity Report 2016 – Annexes], European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/file_import/aar-empl-2016_en_0.pdf

EUROPEAN COMMISSION, D.-E. (2018), 2017 Annual Activity Report: Annexes [Annual Activity Report 2017 – Annexes], European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/file_import/empl_aar_2017_annex_final.pdf

EUROPEAN COMMISSION, D.-E. (2019), 2018 Annual Activity Report: Annexes [Annual Activity Report 2018 – Annexes], European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/empl_aar_2018_annexes_final.pdf

EUROPEAN COMMISSION, D.-E. (2020), 2019 Annual Activity Report: Annexes [Annual Activity Report 2019 – Annexes], European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/empl_aar_2019_annexes_en.pdf

EUROPEAN COMMISSION, D.-R. (2014), 2013 Annual Activity Report: Annexes [Annual Activity Report 2013 – Annexes], European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/activity-report-2013-dg-regio-annex_march2014_en.pdf

EUROPEAN COMMISSION, D.-R. (2015), 2014 Annual Activity Report: Annexes [Annual Activity Report 2014 – Annexes], European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/activity-report-2014-dg-regio-annex_august2015_en.pdf

EUROPEAN COMMISSION, D.-R. (2016), 2015 Annual Activity Report: Annexes [Annual Activity Report 2015 – Annexes], European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/activity-report-2015-dg-regio-annex_april2016_en.pdf

EUROPEAN COMMISSION, D.-R. (2017), 2016 Annual Activity Report [Annual Activity Report 2016 – Annexes], European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/file_import/aar-regio-2016_en_0.pdf

EUROPEAN COMMISSION, D.-R. (2018), 2017 Annual Activity Report: Annexes [Annual Activity Report 2017 – Annexes], European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/file_import/regio_aar_2017_annex_final.pdf

EUROPEAN COMMISSION, D.-R. (2019), 2018 Annual Activity Report: Annexes [Annual Activity Report 2018 – Annexes], European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/regio_aar_2018_annexes_final.pdf

EUROPEAN COMMISSION, D.-R. (2020), 2019 Annual Activity Report [Annual Activity Report 2019 – Annexes], European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/regio_aar_2019_annexes_en_0.pdf

EUROPEAN COMMISSION, O. (2020), 30th Annual Report on the Protection of the European Union’s financial interests: Fight against fraud 2018 (No. 30; Report on the Protection of the European Union’s Financial Interests), European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/anti-fraud/sites/antifraud/files/pif_report_2018_en.pdf

EUROPEAN COURT of AUDITORS (2019), Tackling fraud in EU cohesion spending: Managing authorities need to strengthen detection, response and coordination (Special Report 06/2019 No. 6), European Court of Auditors.

FALKNER, G., HARTLAPP, M., LEIBER, S. and TREIB, O. (2004), ‘Non-Compliance with EU Directives in the Member States: Opposition through the Backdoor?’, West European Politics, 27 (3), pp. 452–473. https://doi.org/10.1080/0140238042000228095

FALKNER, G. and TREIB, O. (2008), ‘Three Worlds of Compliance or Four? The EU-15 Compared to New Member States’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 46 (2), pp. 293–313. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5965.2007.00777.x

FERRY, M. (2013), ‘The achievements of Cohesion Policy: Evidence and methodological challenges from an EU10 perspective’, GRINCOH Working Paper Series, Paper No. 8.01, pp. 1–33.

FERRY, M. and MCMASTER, I. (2005), ‘Implementing structural funds in polish and Czech regions: Convergence, variation, empowerment?’, Regional & Federal Studies, 15 (1), pp. 19–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/13597560500084046

HARTLAPP, M. and FALKNER, G. (2009), ‘Problems of Operationalization and Data in EU Compliance Research’, European Union Politics, 10 (2), pp. 281–304. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116509103370

HOERNER, J. and STEPHENSON, P. (2012), ‘Theoretical Perspectives on Approaches to Policy Evaluation in the Eu: The Case of Cohesion Policy’, Public Administration, 90 (3), pp. 699–715. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2011.02013.x

INCALTARAU, C., PASCARIU, G. C. and SURUBARU, N. (2020), ‘Evaluating the Determinants of EU Funds Absorption across Old and New Member States – the Role of Administrative Capacity and Political Governance’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 58 (4), pp. 941–961. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12995

KUHL, L. (2020), ‘Implementation of Effective Measures against Fraud and Illegal Activities in Cohesion Policies’, The European Criminal Law Associations’ Forum, 2020 (2), pp. 121–133. https://doi.org/10.30709/eucrim-2020-011

MANZELLA, G. P. and MENDEZ, C. (2009), The turning points of EU Cohesion policy, Working paper.

MENDEZ, C. and BACHTLER, J. (2011), ‘Administrative reform and unintended consequences: An assessment of the EU Cohesion policy «audit explosion»’, Journal of European Public Policy, 18 (5), pp. 746–765. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2011.586802

MENDEZ, C. and BACHTLER, J. (2017), ‘Financial Compliance in the European Union: A Cross-National Assessment of Financial Correction Patterns and Causes in Cohesion Policy: «Exploring financial compliance in the EU»’, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies, 55(3), pp. 569–592. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12502

MINISTERSTWO FUNDUSZY I ROZWOJU REGIONALNEGO (2015, December 10), Baza Konkurencyjności Funduszy Europejskich uruchomiona, Portal Funduszy Europejskich. https://www.funduszeeuropejskie.gov.pl/Strony/Wiadomosci/Baza-Konkurencyjnosci-Funduszy-Europejskich-uruchomiona

MINISTRY OF INVESTMENT AND DEVELOPMENT (2018a), Procedura dotycząca środków zwalczania nadużyć finansowych w POPT 2014–2020, Ministry of Investment and Development. https://www.popt.gov.pl/media/87487/Procedura_IZ_POPT_pazdziernik_2018_wersja_koncowa.pdf

MINISTRY OF INVESTMENT AND DEVELOPMENT (2018b), Wytyczne w zakresie sposobu korygowania i odzyskiwania nieprawidłowych wydatków oraz zgłaszania nieprawidłowości w ramach programów operacyjnych polityki spójności na lata 2014–2020, Ministry of Investment and Development. https://www.funduszeeuropejskie.gov.pl/media/66947/Wytyczne_korygowanie_wydatkow_odzyskiwanie_i_zglaszanie_nieprawidlowosci_031218.pdf

ROKICKI, B. and STĘPNIAK, M. (2018), ‘Major transport infrastructure investment and regional economic development – An accessibility-based approach’, Journal of Transport Geography, 72, pp. 36–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2018.08.010

STEPHENSON, P., SÁNCHEZ BARRUECO, M. L. and Aden, H. (eds.) (2020), Financial accountability in the European Union: Institutions, policy and practice (1st Edition). London: Routledge.

TALLBERG, J. (2002), ‘Paths to Compliance: Enforcement, Management, and the European Union’, International Organization, 56 (3), pp. 609–643. https://doi.org/10.1162/002081802760199908

TOSHKOV, D. (2012), ‘Compliance with EU Law in Central and Eastern Europe. The Disaster that Didn’t Happen (Yet)’, L’Europe En Formation, 364 (2012), pp. 91–109.

TREIB, O. (2014), ‘Implementing and complying with EU governance outputs’, Living Reviews in European Governance, 9. https://doi.org/10.12942/lreg-2014-1

VERHEIJEN, T. (2007), Administrative Capacity in the New EU Member States: The Limits of Innovation?, The World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-0-8213-7155-8

VERSLUIS, E. (2005), Compliance Problems in the EU. Paper prepared for the 3rd ECPR General Conference, Budapest, 8-10 September 2005. Panel 3.3: ‘Theorizing Regulatory Enforcement and Compliance’.

ZHELYAZKOVA, A., KAYA, C. and SCHRAMA, R. (2017), ‘Notified and substantive compliance with EU law in enlarged Europe: Evidence from four policy areas’, Journal of European Public Policy, 24 (2), pp. 216–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2016.1264084

| Information on the interviews | ||

|---|---|---|

| # | Role | Period |

| 1 | Representative of the Polish Ministry of Development Funds and Regional Policy: Department of Assistance Programs. | April 2020 |

| 2 | Three Representatives of the European Commission’s DG-REGIO: Unit F3 in charge of Poland. |

April 2020 |

| 3 | Representative of the European Commission’s DG-REGIO: Unit supervising operational programmes on Technical Assistance. |

April 2020 |

| 4 | Representative of the Polish Ministry of Development Funds and Regional Policy: Department of Assistance Programs. | May 2020 |

| 5 | Representative of the Polish Ministry of Development Funds and Regional Policy: Department of Assistance Programs. | May 2020 |

| 6 | Policy officer: the European Court of Auditors | May 2020 |