SENIOR HOUSING POLICY IN POLAND: DETERMINANTS AND DESIDERATA

Lidia GROEGER  *

*

Abstract. This paper aims to determine the comprehensive actions (which require interdisciplinary cooperation) to optimally prepare a high-quality housing environment for the growing population of seniors in Poland in the context of the current housing situation and the need to foster sustainable development. The paper outlines the determinants and specific actions to be taken to implement an effective senior housing policy in Poland. The study is based on the analysis of data obtained from the CSO on the senior housing environment, publications which study the expectations of the growing senior population and on the author’s own research conducted in 2024 among seniors residing in urban and rural areas. The results are a set of recommendations to facilitate the implementation of a rational housing policy targeted at the needs of seniors.

Key words: seniors, housing policy, senior housing, housing environment, housing space, sustainable development, Poland.

1. INTRODUCTION

Given the challenges in the fields of urban planning and architectural design to satisfy the requirements of the ageing population in Poland[1], it is important to understand the current determinants and directions of the housing policy[2] in order to satisfy the needs of seniors while complying with the guidelines of sustainable development. On the macro scale, housing policy is partly convergent with social and economic policies, especially as regards the operation of housing, financial and capital markets. However, on the meso and microscale, any housing policy is an integral part of urban policies (Lis, 2019). While the programmes to date do support housing development, it is mostly for first-time buyers and the current housing policy in Poland is primarily aimed at the needs of young people. Given the changes in age demographics, greater attention should be devoted to identifying the housing needs and preferences of older persons. They are a diverse social group with very different needs that incorporates both professionally active seniors and those who are no longer self-sufficient and require constant specialised care.

The implications that arise from the ageing society have become a pressing issue, which is being widely debated within the public sphere (Szatur-Jaworska, Błędowski, 2017; Szweda-Lewandowska, 2023). This debate focuses primarily on the issues of low birth rates and higher life expectancy (Szukalski, 2017; Błędowski et al., 2012). Jerzy Krzyszkowski (2018) has stressed that while the family in Poland has been traditionally seen as playing the leading role in the structure of senior care, in most cases it proves insufficient (Krzyszkowski, 2018). The long-held belief that the care of ageing parents rests with their children appears quite unrealistic in practice. Demographic changes, the migration of younger generations to major cities, and evolving family patterns all contribute to a decline in traditional family support. As a result, the caring capacity of the family for the safety and support of seniors in their place of residence is eroding. The elderly must increasingly rely on their own financial and organisational resources, which is not always feasible. Thus, the burden on local authority support for senior citizens in adapting their homes to their needs and to provide access to care and nursing services is growing. The decline in the caring potential of the Polish society will also require new, systemic solutions for a sustainable housing environment[3] that considers the needs and abilities of seniors.

An analysis of local spatial development plans at a municipal level reveals that they only contain rudimentary provisions on the adaptation of public space to the needs of an ageing population and on the changes to planning policies to meet demographic trends (Solarek, 2017). It seems imperative, however, to implement standards for the design of the housing environment that consider the needs of the changing demographics.

While senior citizens accounted for 17.2% of Poland’s population in 2005, this figure rose to 26% by 2023. With the decline in the total population of the country and the rise in the share of seniors within the population, there will be an increase in the dependency ratio, which reached 29.9% in 2022. These demographic changes call for systemic solutions for senior policy. A problem that is recognised as evidenced by the establishment of a new ministry for senior policy. Despite this there is still a lack of well-developed and effective tools that could be employed to improve the senior housing policy in Poland.

A number of studies show (Bojanowska, 2021; Magdziak, 2017; Niezabitowski, 2014; Zrałek, 2012) that the home is the most important place for older persons and a focal point of their life, providing shelter, and a sense of security, enabling their most basic needs to be met. As they get older and become less physically and mentally capable, senior citizens spend more time at home or in its vicinity. If they are to remain in their own housing environment, solutions must be implemented to make their everyday life easier.

The relevance of the home stems, inter alia, from its role in public policy. Article 75 of the Constitution of the Republic of Poland obliges public authorities to pursue policies conducive to satisfying the housing needs of citizens. This issue is also among the tasks assigned to local (municipal) governments, which are obliged to take measures to improve access to housing.

With this in mind, this paper aims to raise awareness of the need for action on senior housing policy in Poland; to establish the necessary standards and quality of senior housing; the housing needs of this social group and to identify desirable instruments for senior housing policy while commenting on their current performance.

2. LEGAL CONDITIONS

In 1991, the United Nations General Assembly adopted Resolution no. 46/91 called United Nations Principles for Older Persons, which provided recommendations on senior housing, stressing that older persons had the right to dwell in conditions adapted to their individual requirements and suited to their deteriorating health and capacities. The need for them to remain in their current place of residence for as long as possible was also stressed.

Article 23 of the (Revised) European Social Charter adopted by the Council of Europe in 1996 explicitly states that every older person has the right to social protection. This right aims to enable seniors to remain active members of society for as long as possible by providing means for a dignified life and active participation in public, social, and cultural life; supplying information on available services for seniors, guidance on how to use them and enabling them to continue their lifestyle, and remain independent in a familiar environment for as long as desirable and possible. This includes, inter alia, adapting housing to their needs and health requirements or assisting them in doing so; providing necessary medical care; and respecting their privacy and promoting their involvement in decisions about moving to more suitable accommodation (e.g., care homes).

The Act on Social Care of 2004 only stipulates that “a person who – due to age, illness or other reasons – requires assistance from others but does not receive such assistance, is entitled to custodial or skilled care.” The arrangement and provision of such care at the person’s place of residence is an obligatory task assigned to local authorities.

In 2014, the Council of Europe compiled a document on the protection of the rights of older persons, entitled Recommendation CM/Rec(2014)2 of the Committee of Ministers to Member States on the Promotion of Human Rights of Older Persons, which proposed a social policy structure divided into three key sectors. The first is public institutions in charge of planning and implementing state policies financed by public funds, the second sector, known as the market sector, is composed of a variety of for-profit entities and often relying on public support to meet social needs, while the third sector, often referred to as the non-government or civic sector, comprises a wide range of organisations that have different objectives and legal forms and are independent of the public sector. These not-for-profit institutions often rely on volunteers and are autonomous from public administration.

In Poland, senior policy only emerged as a separate field of public policy in 2012, following the initiative of The European Year for Active Ageing and Solidarity between Generations (Szatur-Jaworska, 2015). However, the Act on Older Persons of 2015 contains no regulations on the housing environment, except for a single recommendation to monitor housing conditions.

Similarly, the 2018 governmental publication Social Policy Towards Older Persons 2030: SAFETY – PARTICIPATION – SOLIDARITY [Polityka społeczna wobec osób starszych 2030. BEZPIECZEŃSTWO – UCZESTNICTWO – SOLIDARNOŚĆ] only provides recommendations on what ought to be done in social policy, without detailing who is responsible and within what timeframe the different actions need to be taken. As for senior housing policy, this publication, which is over one hundred pages long, contains only the following recommendations:

- “Reducing dependency on others by facilitating access to services that enhance independence and adapting the housing environment to the functional capabilities of dependent older persons.”

- “Promotion of activities aimed at the eradication of functional barriers within the housing environment of dependent older persons shall be pursued through implementing projects and raising public awareness of partners from all sectors within the field of universal design. Besides the measures aimed at providing direct services to dependent older persons, it is also imperative to adapt the housing environment to their needs and capabilities so as to enable them to remain in their own home for as long as possible.”

The manner in which these postulates are formulated and the little attention generally paid to senior housing policy in the said document indicate a lack of state policy on the senior housing environment in Poland.

3. HOUSING CONDITIONS FOR SENIORS

As of 2022, the majority of elderly persons resided in urban areas. At that time, the level of urbanisation among the 60+ population amounted to 64.1%, representing 27.9% and 23.0% of the total urban and rural populations, respectively (CSO, Situation of Older Persons in Poland [Sytuacja osób starszych w Polsce w 2022 roku]).

Source: CSO, Situation of Older Persons in Poland in 2022 [Sytuacja osób starszych w Polsce w 2022 roku].

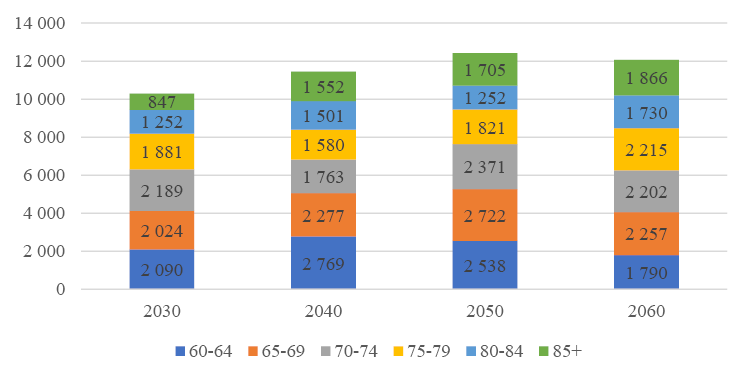

According to CSO projections, the 60+ population will reach 10.3 million in 2030 (an increase of 5.0% compared to 2022), 11.4 million in 2040 (+16.8%), and 12.4 million in 2050 (+26.6%). The projected age structure reveals that over the next fifteen years there will be a significant rise in the senior population aged both 60−70 and 80+. The peak is predicted in 2060, at which time the senior population is predicted to reach 11.9 million (+21.0% compared to 2022), accounting for 38.3% of the total population in Poland (Fig. 1).[4]

In 2022, households containing only people aged 60+ had an average monthly disposable income of 2,623 zlotys per person. However, their expenditure per capita was, on average, 26.3% higher than in households with no senior members.

As shown by the CSO data for 2022, the percentage of seniors taking out mortgages was 3.4%, with the average debt amounting to ca. 88,000 zlotys. In contrast, data from the Credit Reference Agency in Poland reveals that older persons have long primarily resorted to consumer loans, which are the most common type of debt among this age group. Data obtained from two Polish banks – PKO BP and mBank – indicates that this is virtually the only type of credit product available to seniors, and also that the interest rates on these loans are among the highest. Given the age restrictions imposed by banks, a mortgage is practically unattainable for seniors should they desire to purchase a new property that is better suited to their needs, and then sell the one they currently reside in, for instance.

The CSO data for 2022 also shows that the average usable floor space in senior-only household was 71.2 sq. m, with significant disparities between urban and rural areas. In cities, the average floor area of properties occupied by seniors was 64.7 sq. m, rising to 93.2 sq. m in rural areas. The average floor area of homes occupied by single seniors was slightly smaller, averaging 60.8 sq. m, while this figure amounted to 82.3 sq. m for two-person senior-only households.

| Details | Total | Urban areas | Rural areas |

|---|---|---|---|

| percentage of seniors' homes | |||

| Running water from water mains | 99.8 | 100.0 | 99.4 |

| Flushable toilet | 98.8 | 99.4 | 96.8 |

| Bathroom | 98.6 | 99.1 | 96.7 |

| Hot running water | 99.0 | 99.5 | 97.3 |

| Gas | 91.5 | 91.5 | 91.5 |

| from mains network | 67.8 | 79.6 | 27.7 |

| from gas tanks | 23.7 | 11.9 | 63.8 |

| Air-conditioning | 1.9 | 2.2 | 1.1 |

| Central heating | 86.4 | 88.3 | 80.0 |

| Boiler | 13.5 | 11.6 | 19.7 |

Source: CSO, Situation of Older Persons in Poland in 2022 [Sytuacja osób starszych w Polsce w 2022 roku].

Analysis of access to basic home facilities (Table 1) reveals that – save for air-conditioning or occasionally central heating – the situation for seniors is quite favourable, with elderly residents of rural areas only experiencing slightly worse housing conditions. Indeed, compared to data for all Polish citizens, it does not differ significantly from the national average. The exceptions here are the aforesaid air-conditioning, to which very few seniors have access, and the floor space per capita, which for seniors is considerably larger than the national average.

| Details | % of a given type of household within all households | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| with no over-60s | over-60s only | |||

| total | including | |||

| single-person households | two-person households | |||

| adequate technical and sanitary conditions | 96,7 | 93,4 | 89,9 | 97 |

| located in a noisy or polluted area | 5,5 | 6,1 | 5,4 | 6,8 |

| located in an area at significant risk of crime, violence, vandalism, etc. | 0,4 | 0,4 | 0,3 | 0,5 |

| located in an area with poor infrastructure | 7 | 8,1 | 9,4 | 6,8 |

| located in a particularly sought after area | 5,2 | 5,4 | 5,2 | 6 |

| has a balcony (patio), garden | 94,6 | 91 | 87,5 | 94,5 |

| sufficiently warm in winter | 98 | 96 | 93,8 | 98,2 |

| sufficiently cool in summer | 97,7 | 96,7 | 95,7 | 97,8 |

| located in a building with reduced access due to architectural impediments | 15,5 | 16,8 | 16,2 | 17,7 |

Source: CSO, Situation of Older Persons in Poland in 2022 [Sytuacja osób starszych w Polsce w 2022 roku].

Based on the subjective opinions provided by the surveyed senior citizens, it can be stated that the majority of homes meet adequate technical and sanitary standards (Table 2). In 2022, 96.0% of all households containing only people aged 60+ considered their housing conditions as adequate when it came to technical and sanitary standards. In urban areas, this was stated by 96.8% households, while in rural areas: 93.4%. The majority of homes provided adequate thermal comfort in winter (96.4%) and summer (96.0%). Finally, 78.9% of seniors stated that they had access to a balcony or garden at home.

However, research conducted by the CSO on the subjective opinions on housing quality also revealed that people aged 60+ considered access to a balcony or garden in their home to be worse than among younger age groups. The same applied to living in a building with architectural barriers that make access to the home difficult (28% of respondents). Senior citizens also consider the noise and pollution in their neighbourhood to be slightly worse than other age groups. However, they report the technical and sanitary conditions, as well as thermal comfort in winter and summer as acceptable.

The self-assessment of their financial situation and housing conditions by older persons shows a strong dependence on the number of members of the household. When compared to those in two-person households, seniors living alone are less likely to describe their financial situation as good or quite good (29.4% versus 49.2%) and more inclined to perceive it as bad or quite bad (12.7% versus 3.4%). Seniors living alone in rural areas are particularly negative in the assessment of their economic situation. In 2022, 17.0% of seniors in single-person rural households considered their situation as quite bad or bad. As in previous years, the highest financial contentment was stated by seniors living in two-person households in urban areas, where 52.7% considered their economic situation as good or quite good in 2022.

In late 2022, there were 31,600 patients aged 60+ in residential health care facilities, nursing homes, hospices, and terminal wards. The largest group were people aged 80+, amounting to 16,700 people. At that time, there were 2,082 full-time social care facilities, an increase of 67 units compared to 2021, including 902 social care homes and 632 centres providing 24/7 care for the disabled, chronically ill, and seniors.

When one considers that older persons account for a staggering 50% of the homeless population and ca. 40% of the residents of night shelters, it shows what serious problems they face in accessing permanent accommodation and effective support, a fact that demands tailored measures to resolve this travesty.[5]

The data above reveals how very different and difficult the housing and financial situation of Polish seniors can be. For this reason alone, it is essential to perform an in-depth analysis of the availability of financial instruments to support independent housing for seniors.

In 2015, an international survey (98 countries) of the living conditions among older persons was conducted, in which Poland ranked 32nd. The results showed that the homes of the Polish elderly are often unsuitable for their specific needs and limitations. The most common issues include high maintenance costs, limited accessibility due to reduced mobility, and poor access to public transport.

In addition, research conducted as part of the Pol Senior2 Project confirms that a large number of Polish high rise residential areas fail to meet the requirements of seniors, who, paradoxically, are the largest group residing there at this time (Niezabitowski, 2014). On the one hand, this stems from the fact that when they were erected (between the 1960s and 1980s), they were mainly populated by young parents who have now turned into elderly residents of limited mobility. On the other hand, this also results from the political transformation of 1989, and more specifically, from the changes in the real estate sector after 1990 (Szafrańska, 2010), which had led to pensioners today account for a significant percentage of property owners in Poland. According to a pilot census study conducted in the municipality of Połaniec on the housing and economic situation of seniors (Tomasz Duda, Housing policy and ageing [Polityka mieszkaniowa a proces starzenia], 2014), approximately 70% of people aged 60+ lived independently (without children) in their own flats or houses, with an average floor area of 90 sq. m.

The 2022 study by the Public Opinion Research Centre in Poland found that the average floor area per citizen aged 65+ amounted to 47 sq. m, which was ca. 12 sq. m more than for younger age groups. These figures imply that the floor areas of homes occupied by older persons often exceed what is considered the optimum size for them to live comfortably with low maintenance costs. Oversized homes burden their budgets, especially in winter, thereby further exacerbating their financial situation.

The monograph entitled Medical, Psychological, and Sociological Aspects of Aging in Poland [Aspekty medyczne, psychologiczne, socjologiczne starzenia się ludzi w Polsce] (2012) also addressed the issues related to the conditions of senior housing, showing that over 55% of respondents aged 80+ lived in single-family homes; 41% in multi-family residential units, and 0.6% in retirement homes. Among people aged 90+, retirement homes were home to 1.1% of respondents. In addition, architectural barriers pose a particular challenge for the oldest seniors, for instance, 22.8% of people aged 80+ state they are a major problem when attempting to leave home. The study further revealed that seniors rarely engage in refurbishment of their homes, exhibiting a passivity in this regard (Bartoszek et al., 2012).

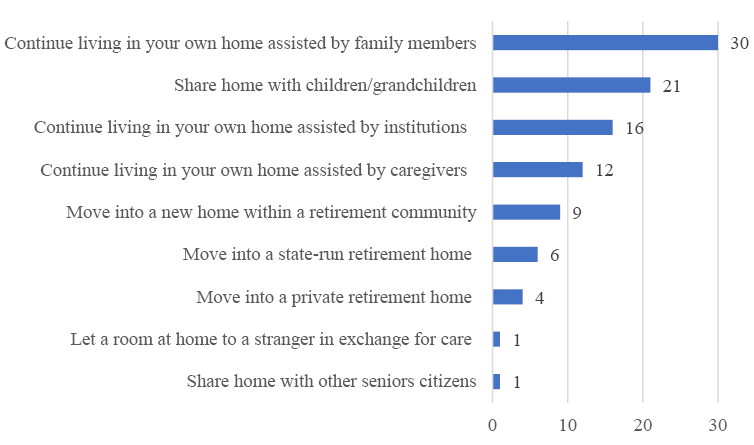

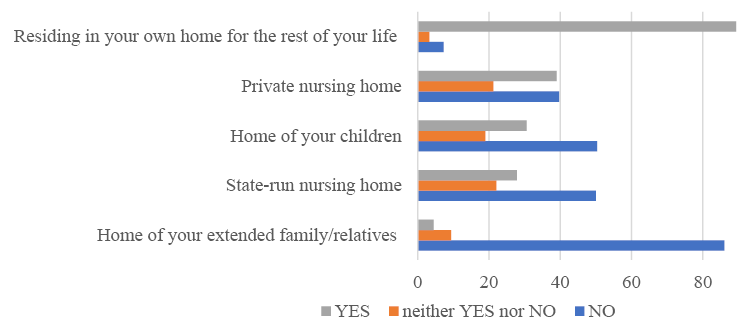

Regardless of the current condition of their housing, seniors are often reluctant to change their present home for a smaller, more cost-effective and modern one. This age group displays a strong attachment to their home, which sometimes makes the decision to move house difficult, even if it were to result in financial benefits and improved comfort (Fig. 3). 80% of seniors would rather stay in their present home while benefitting from various forms of support provided by relatives and/or caregivers, even if they were unable to lead a fully independent life.

Source: Łukasz Strączkowski, Marcin Boruta (2018), ‘Housing Conditions and Senior’s Decisions on the Local Housing Market’ [‘Warunki i decyzje mieszkaniowe seniorów na lokalnym rynku nieruchomości’], Krakow Review of Economics and Management, 3 (975), pp. 69−81.

Since there is still a dearth of comprehensive studies of the conditions of senior housing that consider: the spatial distribution, age structure, household size, and financial situation of senior households in Poland, research conducted for individual municipalities remains the main source of information (Duda, 2014; Mossakowska et al., 2012). This research indicates that the housing situation in rural municipalities for seniors shows they reside in homes that are larger but worse equipped and furnished than those in cities. The latter are smaller (mainly 36 to 60 sq. m) but primarily located in blocks of flats built between the 1960s and 1980s by housing co-operatives, which means the location is usually quite favourable, as are the technical conditions and access to green areas, services, and public transport. However, the ever growing utility bills coupled with general property maintenance costs in the city can put a financial strain on senior citizens. This burden is currently estimated at ca. 30% of the average retirement pension for seniors in urban areas (this type of data is unobtainable at present for those residing in rural areas).

A 2023 study of the housing situation in Poland conducted by the Habitat for Humanity Poland Foundation[6] showed that the cost of maintaining homes has grown noticeably, while residents’ ability to improve housing conditions has remained limited. The concern most often reported among those surveyed was the inability to perform the necessary renovations, and an increasing number of respondents also mentioned difficulties in maintaining thermal comfort in their homes throughout the year – a problem that has exacerbated in recent years, becoming the second most commonly cited housing-related challenge in Poland. Given the low disposable income of seniors compared to the overall average income among Polish residents, one may presume that this is the reason older persons are impacted even more.

4. SENIORS’ HOUSING PREFERENCES, CONSTRAINTS, AND NEEDS

Currently, there are neither comprehensive nor representative studies on seniors’ housing preferences and needs in Poland. However, this research subject has been addressed through surveys and interviews conducted primarily in urban areas and in relation to preferences on the housing market (Magdziak, 2017; Strączkowski and Boruta, 2018; Tanaś et al., 2019; Jancz and Trojanek, 2020). A broader picture was provided in a 2015 social cohesion study conducted by the CSO, which revealed that Polish seniors feel a strong attachment to their place of residence.[7] Namely, as many as 96% of respondents aged 65+ declared a strong bond with their homes, while 85% felt a connection with their neighbours and the local community. This attachment to the home was also observed to be more important than relations with neighbours, indicating the fundamental significance of home in their everyday life (Dudek-Mańkowska, 2017).

Trzpiot and Szołtysek (2015) reported that seniors attached great importance to a number of factors that supported health, mobility, quality of public space, safety, and daily life when assessing their place of residence. Accessibility of health centres and the quality of services they provide was a priority. As for mobility, they highly valued the possibility to travel easily, especially using mass transit. What mattered were comfort while waiting for a bus or tram, priority seats, the ease of transfer and the overall quality of public transport. The immediate surroundings of the home also played a major role. Seniors had a negative perception of neighbourhoods that were noisy, run-down or considered a poor neighbourhood with black market activity. High-quality public space was also of importance, especially places that fostered social interaction, e.g., parks, culture venues, community centres, etc., U3As, outdoor gyms, and health centres. Seniors particularly appreciated the proximity and easy access to such facilities. Top priorities for safety were safe pedestrian crossings, safe surroundings of bus and tram stops, streets, neighbourhoods and public spaces, as well as quick response times of rescue services in an emergency. As regards everyday life, support for vulnerable individuals, including the elderly and the disabled, was essential since it translates into sense of security and good quality of life.

Paweł Kubicki (2016) has identified three major obstacles that impede the social integration of older persons and affect how user-friendly cities and towns are for them. These are architectural barriers, difficulties in accessing health care, and financial constraints. For many senior citizens, the latter is a major obstacle to being active outside the home. Participation in activities also depends on health, which is often a prerequisite for an active life. This is where architectural barriers come into play as they may greatly limit the possibilities for seniors experiencing reduced mobility. Another issue is poorly adapted homes and buildings (lacking lifts and ramps, etc.), which further restricts mobility. A feature of public infrastructure that is crucial for the comfort and well-being of older persons are benches, ideally placed at distances from one another so that seniors can rest on their way to the shops or while out walking. Equally relevant is easy access to public toilets, which are still uncommon in many cities.

Strączkowski and Boruta (2018) have confirmed that the elderly generally wish to reside in their homes for as long as possible, using the assistance of official (caseworkers, etc.) or unofficial (relatives) caregivers. Younger seniors are more open to alternatives to staying in their current home, including senior housing communities or co-living with other persons in exchange for care, and seniors living alone are more likely to consider living in a retirement home, be it private or state-run (Strączkowski and Boruta, 2018).

Feedback collected in the project Seniors Decide – Senior Citizens’ Dialogue in Kraków [Seniorzy decydują – dialog obywatelski seniorów w Krakowie] (Spasiewicz-Bulas, 2013) has revealed that factors like financial independence, access to quality health care, regular contact with relatives, and the ability to remain as independent as possible are vital for seniors. The last element largely depends on the removal of architectural barriers in urban space, as confirmed by studies into the activity of the elderly and the disabled (Bujacz et al., 2012), which indicate that the needs of the elderly are poorly addressed in new urban developments. For instance, there are often no clear markings separating pavements from cycle paths and too few benches (only 10% of the 102 streets under study in Kraków have them).

Senior citizens also report a number of issues inside their homes and within the buildings where these are located, especially in blocks of flats that have no lift, which greatly impedes their mobility, resulting in reduced social contact and impaired health. They mention difficulties within their flats, e.g., the non-ergonomic positioning of bathroom fittings that render it difficult to maintain personal hygiene and increase the risk of a fall and injury, which for an elderly person can have grave health consequences. Another issue are cupboards and cabinets that are often positioned too high or too low, thus making it hard to reach the items stored there. These factors often cause seniors to become isolated, contributing to social exclusion and deteriorating well-being. If their homes were adapted to their needs, it would be fundamental to improving their quality of life and independence.

As part of her own research aimed at expanding the knowledge on how seniors in rural and urban communities of Łódź and its vicinity assess their home and what preferences they have in this regard, in 2024 the author conducted twenty in-depth interviews with people aged 65−90. Given the complete lack of such data on seniors in rural areas, it was deemed imperative to include them into the study alongside elderly residents in urban areas. During the interviews, common opinions of home and specific needs were revealed, although these depended on the place of residence, the household size, and the age of the respondent.

Besides the opinions and preferences indicated above, the interviewed seniors reported a strong attachment to their homes, where they have had often lived for many years, further strengthened by good rapport with neighbours (often the only form of social interaction). Seniors spend their time mainly in the private space of their flat, allotment or garden (if any), and these factors determine the level of satisfaction with their current home. While members of two-person households considered their living conditions the best, those aged 80+ would often like to be assisted by and reside with relatives under the same roof, but in separate living quarters. Although they are generally reluctant to use day care centres, they still consider the possibility of moving, motivated by easier access to health care, better relationships with new neighbours, and the possibility to remain reasonably independent. They favour living in smaller towns with good access to health care and shops, believing that the public space in such places (e.g., Koluszki or Łęczyca, both ca. 13,000 residents; CSO, 2023) is better adapted to their needs than in large cities like Łódź. In their place of residence, they value peace and quiet, e.g., they are easily disturbed by loud church bells, heavy traffic, etc. Other issues that may deter them are uneven pavements, potholes, dogs running loose and making them feel unsafe, and “too few benches, not enough green spaces, as these are blocks of flats made for dwelling, not leisure.”

In rural areas seniors mostly would like a decent road with a separate pavement for pedestrians but, if there is one, they would still complain, this time about the traffic. They also complain about the long distances to bus stops and shops (“everywhere is far from here”), which translates into poor mobility, especially among those who have no driving licence (mainly elderly women). Thus, demand for a mobile grocery van or a mobile hairdresser is reported. Although seniors are aware that they can shop online, they do not often use this option. And since they rarely use the Internet, they also have limited knowledge of help dedicated to seniors or cultural events promoted online. Although affected by the rising cost of home maintenance, seniors still claim that it is paying for medication that poses a greater financial burden on them.

Seniors who reside in urban areas consider flats of ca. 40 sq. m to be the optimal size for their needs and in terms of maintenance costs. They greatly appreciate it if their flat has a large balcony. The most commonly reported problem with the building itself is the absence of lifts and stair handrails, while for the immediate vicinity it is places to sit and rest. Seniors also would like air-conditioning, dedicated parking spaces for the residents of the building, and push-button activated pedestrian crossings. If assistance is needed, they rely on family or friends, and use taxis if mobility is impaired. Younger seniors would like to have a café in the vicinity of their home, a graduation tower, and a venue for events dedicated to seniors that would enhance their well-being without having to travel longer distances.

Although older persons often choose to remain in their current housing environments for as long as possible, even if their independence is reduced (Fig. 3), the aforesaid survey among seniors in Połaniec revealed that this decision was by no means absolute. When given the opportunity to move to a home adapted to their needs and allowing them to maintain independence, over 70% stated they would be willing to do so, which indicates a potentially high demand for such solutions (Duda, 2014).

Source: a survey by Elżbieta Bojanowska, Martyna Karwińska (2018) entitled Attitudes of Senior Citizens towards Old Age and the Social Determinants of Ageing, on a Sample of 453 Respondents Aged 60+, Residents of the Warmian-Masurian Province [Postawy seniorów wobec starości i społecznych uwarunkowań starzenia się, na próbie 453 respondentów w wieku 60 lat i więcej, mieszkańców woj. warmińsko-mazurskiego].

In order to allow seniors to benefit from living at their home for as long as possible, thereby reducing the costs of social care and supporting intergenerational relationships in their place of residence, the housing stock should be adapted to meet the specific needs and requirements of older persons. This requires a number of measures to be taken at the national level, namely the launch of support schemes that would make it possible to fund renovations and adaptations so that current housing could meet seniors’ needs. A legal obligation for property developers to build a certain percentage of homes adapted to the needs of the ageing population is also an option worth considering. However, the greatest room for action remains with local authorities and could be pursued under the slogan: “one day you will also be a senior,” for example.

5. INSTRUMENTS OF THE HOUSING POLICY AIMED AT SENIOR CITIZENS

A housing policy that focusses on older persons and is implemented on national and municipal scales by both public-private partnerships and private entities should consider a variety of aspects so as to provide senior citizens with safe, comfortable and tailored housing. The key components of the policy proposed are as follows.

5.1. Financial availability

Nearly all activities require financing, and thus, financial assistance for low-income seniors should be made available, including subsidies, tax exemptions, and dedicated banking products to enable them to sell their present properties in order to buy, or rent long-term, homes better suited to their needs.

The only instrument currently available to seniors is the housing benefit disbursed by municipalities. In 2022, 2,648,000 households in the country reportedly benefitted from this support, with an average allowance of 276 zlotys (CSO, 2023). However, there is no detailed data on the number of seniors that received this benefit. Although the benefit itself and the criteria for its acquisition[8] are positives, the list of documents required (property information sheet certified by the housing co-operative or community, pension statement for the three months preceding the application, extract from the land and mortgage register confirming ownership of the property, forms that need to be downloaded from the office’s website and then filled out), the difficulty in understanding the information on calculating the benefit amount, and then the need to repeat the whole procedure every six months, render the entire process rather problematic to seniors.

Another instrument, tax deductible renovation costs, was in force in the 1990s, resulting in the refurbishment of a large number of homes and reducing the grey market of contractors, as invoices were required to obtain the tax deduction. As a result, it also generated revenue for the budget (Groeger, 2016). Currently, only subsidies for boiler replacement and thermal modernisation of the building are available, but there are no schemes to support the renovation of bathrooms, their adaptation to seniors’ needs, or the installation of lifts or balconies. Even when an elderly person has the financial means, they would still find it immensely difficult to single-handedly manage an investment project of this scale. Thus, it would seem sensible to offer a “documentation to finished state” renovation of their bathroom or installation of a lift, especially given the fact that there is a wide range of similar services on the market, e.g., from renovation companies that replace windows and doors. As regards the installation of a lift, a further hindrance is the legal requirement to obtain the consent of all tenants within the building, which often renders the investment unfeasible.

As stated above, a home mortgage loan is virtually unattainable for seniors, even if they own another property that could act as collateral (based on information from PKO BP and mBank) for agents operating on the property market who would like to recommend this product to their senior customers (Strączkowski and Celka, 2012). Older persons are usually only able to take out a high-interest commercial loan of up to 250,000 zlotys, which frequently prevents them from replacing their current home with one better suited to their needs.

Since 2014, a reverse mortgage has been available for seniors who own a property that fulfils the requirements. This equity release allows the house owners to improve their current financial situation. The loan amount depends on the market evaluation of the property in question, and generally ranges from 30% to 60% of its estimated value. The funds can be paid out either for the rest of the senior’s life or over a contractually stipulated period. Upon the death of the loan recipient, either the financial institution acquires the property or the senior’s heirs keep it upon repaying the loan with any interest accrued. Despite the transparent legal regulations for this solution, it remains rather an unpopular option and, so far, no bank in Poland has decided to offer this product.

There is also a product called life annuity provided by mortgage funds, which are entities unregulated by banking law, making this instrument quite risky. According to the Bankier.pl website and based on data from the Association of Financial Enterprises, between 2010 and 2022, mortgage funds paid out only 30 million zlotys, with an average monthly benefit of ca. 1,000 zlotys, despite managing properties worth 150 million zlotys at the time. These figures testify to the low coverage and the still perceived high risk of participating in this scheme.

5.2. Housing availability

A well-designed senior housing policy should accommodate a variety of housing options for older persons, considering their family situation and level of independence.

The most desirable accommodation type amongst seniors today in Poland is independent living and, if affected by disability, it is care homes known as Social Care Homes (SCH) or nursing homes known as Residential Health Care Facilities (RHCF). However, the number of beds in these units is limited and the standard of service varies. In 2024, the monthly fee to stay in a state-run SCH ranged from 6,000 to 9,000 zlotys, depending on the location. The cost must be borne by the senior citizen, their relatives and/or the municipality. Other accommodation options include assisted living, sheltered housing, supported living, intergenerational homes, and retirement homes (Dudek-Mańkowska, 2017).

A more appropriate housing policy and greater commitment to its development would extend the period of independence for seniors and allow them to be supported more effectively in the place where they live, often for decades. The demographic projections noted previously reveal the importance of this action, which means the problem will escalate over time and a number of housing policy measures should be taken with no further delay.

One such desirable measure would be to promote or even mandate housing adapted to seniors’ needs, i.e., free from architectural barriers. There are architectural design studies that focus on the needs of seniors at different ages, e.g., a study by Maria Bielak-Zasadzka and Dominika Szweda (2022) which has considered a broad spectrum of factors, i.e., the need for housing that is easily accessible by public transport, has proximity to green areas, easy access by road, is within a safe neighbourhood, and has no serious nuisance factors in the vicinity. The body of the building itself should have a maximum of three floors, use natural finishing materials, shared spaces suitable for its residents (wide corridors, staircases, etc.), a clearly marked and easily accessible main entrance, and no architectural barriers. The building should contain single or two-person housing units, and be well lit by daylight. The housing development itself should allow convenient access to the building (incl. facilities for the disabled), have a sufficient number of parking spaces, be favourably orientated to make the most of the daylight, and have no architectural barriers. Designing buildings and their immediate surroundings to suit the needs of seniors of all ages should be fostered through architectural competitions and be widely promoted among municipal authorities and property developers.

Assisted living is a solution addressing the housing needs of seniors who, while in need of some support, still wish to live independently and be part of the local community. This housing option can be a major component of the long-term care system for older persons. For instance, in the USA it is enjoyed by over a million residents across ca. 36,000 facilities (Andrews, 2010). Assisted living aims to support seniors to live independently outside the relatives’ home or care centre, through providing professional assistance from caregivers, wardens and volunteers.

In Poland, assisted living projects are implemented by municipalities, but their scope remains very limited.[9] Private property developers have considered the introduction of senior apartments,[10] but this product has so far been aimed at wealthy citizens who do not require permanent care. Gradzik (2017) has argued that only 3% of Polish seniors can afford this type of accommodation, making assisted living an option available to a tiny fraction of the senior population and thus a marginal housing option on the national scale.

In Poland, there are very few social or council housing units adapted to senior’s needs. Priority is given to families with children and those at risk of eviction. Many municipalities do not provide social or communal housing at all, as it is perceived too heavy a burden given the obligation to maintain the housing infrastructure. And in cities that offer this type of housing, there is a long waiting list, which is a major challenge for senior citizens.[11]

5.3. Safety

Safety at home should include the categories of physical, economic, welfare, and social safety. Based on the results of the surveys cited above on the preferences and nuisances reported by seniors, it should suffice to introduce renovation programmes (e.g., applying the tried and tested rules governing the thermal modernisation of buildings) and to impose mandatory regulations for lifts, ramps, and widened entrances to staircases and flats to be implemented in the existing buildings. A recommended conduct for interiors would involve offering affordable refurbishment of bathrooms (replacing bathtubs with showers, installing bath and shower grab bars, etc.), smoke and water leak detectors, and periodic inspections by relevant experts. With consent, visual monitoring and an easily accessible alarm button could also be installed inside the flat. Given how great the uptake for replacement windows and doors to improve thermal and acoustic comfort has been among seniors, it is quite likely that a programme to enhance safety at home, which would not require direct, physical involvement on their side, would be equally popular with seniors and they may be more than willing to fund it. A balcony clearly adds to the comfort at home. Alas, a number of factors, including the procedure to obtain a planning permission, the legal obligation to get the consent of all other tenants, and the necessity to coordinate the entire investment, render it unfeasible for most individuals in Poland. The same applies to the addition of lifts in blocks of flats that were not originally equipped with these facilities. Thus, appropriate legislative measures to simplify the procedural requirements behind such investments would be advisable in this regard.

Physical safety near home is determined by well-lit streets, smooth pavements, not too steep ramps and, of course, regular benches (which seniors mention repeatedly), which should be provided as standard along footpaths and within residential areas. Another factor to be considered is to construct public toilets in grocery discount chains and local shops in exchange for incentives for the owner, e.g., reduced taxes or rent.

The sense of safety among seniors is also strongly impacted by home delivery services, e.g., the delivery of shopping or meals. Although available on the market (e.g., boxed diets), these solutions are often difficult for seniors as they may lack the necessary online skills or experience financial or health constraints. In Poland, the implementation of long-term care insurance, which has long been available abroad (e.g., in Germany since 1995, in Japan since 2000, and in France since 2007), should also be considered (Zych, 2019).

5.4. Health care and nursing services

All surveys conducted to uncover seniors’ attitudes show the paramount importance of easily accessible health care and nursing to their place of residence. For this reason they have been placed in a separate section of this paper, even though they are unquestionably related to the safety at home discussed above. Since seniors state that medical costs are the greatest burden to their budget, this issue should be entrusted to relevant institutions. To counteract loneliness and the feeling of helplessness at home, psychological and social support programmes as well as group therapy for seniors should be implemented using support groups, voluntary work or social activation schemes. These initiatives, however, require suitable and publicly accessible space within residential areas.

5.5. Community and integration

In any housing development it is important to promote intergenerational communities, in which seniors can live close to younger people and benefit from mutual support. One worthy approach is the concept of time banking, an informal barter network where time replaces money. Participants provide services, be it child or pet care, tuition, cooking lessons, doing shopping, cleaning, etc. The key principle is all services are valued equally, regardless of their actual market price elsewhere, and the unit of account is time, i.e., a single hour. Time spent by one participant helping another can be reclaimed when yet another participant assists them in a different matter. To launch a time banking scheme, one needs a group of people willing to exchange services, and this should include senior citizens. While service exchange are easier managed online, such schemes can still operate without access to the Internet. However, it is always mutual trust between participants that is a prerequisite to launch them (Pędziwiatr, 2015).

There should also be communal spaces where seniors could meet and participate in activities near their homes. In 2014, the state-run Senior-WIGOR programme was launched, which, from 2016, ran under the name Senior+ and covered the years 2015−2020 as part of Premises of the Long-Term Senior Policy in Poland of 2014−2020 [Założenia Długofalowej Polityki Senioralnej w Polsce na lata 2014–2020]. The programme allowed local authorities to decide which of the two types of day-care facilities for the elderly they would like to establish: a Senior-WIGOR day-care home or a Senior-WIGOR club, differing in the range of services offered. The choice depended on the actual needs, and the financial support from the state budget that was earmarked for local authorities (often under budget pressure) with high proportions of the elderly within the population and insufficient infrastructure to provide social care and nursing services outside of seniors’ place of residence.

Having analysed the implementation of the programme, Grzegorz Gawron reported that over a five-year period 7,070 seniors benefited from day care centres and 12,134 seniors from senior clubs (Gawron, 2023). The predominant beneficiaries were residents of rural municipalities (367 municipalities) and urban-rural municipalities (226). In contrast, only 117 urban municipalities and 62 cities with powiat rights participated in the programme. All senior participants claimed to have been very satisfied with the initiative, and between 80% and 90% reported that almost all important aspects of their lives had improved (Gawron, 2023).

The said initiatives should be assessed positively and be promoted accordingly. The only concern is the poor recipient reach, which may be evidence of limited publicity and insufficient public awareness.

5.6. Education and communication

In Poland, only 0.6% of the 60+ population participate in courses, lectures or educational programmes, compared to 5% in other EU Member States (Zych, 2019). The inclusion of seniors in the process of shaping the living space could be achieved through the involvement of local leaders who are knowledgeable about the administrative processes and regulations that shape local land use laws (Bujacz et al., 2012). For this reason, it is essential to educate seniors on how local governments operate, how municipal policies and local regulations are developed, and what local initiatives that support seniors on legal, social and economic issues are available.[12] This issue could be addressed by help and advisory desks for seniors, providing information on support programmes and opportunities to solve housing issues, available online and on-site. Another effective way of reaching seniors would be traditional letters containing guidelines on the available support instruments, services, institutions, voluntary organisations, time banking schemes, etc., sent to their home address. Fortunately, younger seniors in years to come will most likely be able to make use of the information posted online more effectively.

5.7. Transport

Providing easy access to public transport adapted to senior’s needs (low-floor vehicles, priority seats, raised stop platforms, etc.) has been partially achieved in large cities. Other improvements should include more legible timetables (large font, more conveniently placed signboards), seats at stops, and more push-button pedestrian crossings. As for rural areas, the organisation and performance of public transport is still quite a challenge. As is often the case, solutions should incorporate a number of complementary activities: communication, social integration, and coordination of actions within a given area. Once up and running, local senior citizens’ associations prove to be very successful, especially when acting on their own behalf. Seniors become more active and willing to help each other, and they no longer feel alienated in their housing environment (Gawron, 2018).

5.8. Assistive technologies

In technologically developed countries like Poland, support should be given to the promotion and subsidisation of home assistive technologies for seniors, including telecare systems, smart home devices, and health monitoring applications, which are all relatively easy to implement. While email communication and the use of dedicated patient service applications should be standard in health clinics today, practice shows that in primary health centres the simple renewal of a prescription for regularly taken medication still requires seniors or their caregivers to appear there in person and present a prescription. Equally desirable would be the application of AI in contacting seniors for early identification of their needs. Clearly, the comprehensive and efficient implementation of the software should be preceded by training on how to use this modern technology, constantly available online for seniors or carers.

5.9. Long-term policy

Measures for senior housing policy should shift away from short-term, small-scale programmes to the long-term operation of proven support instruments that produce the most desirable results (e.g., Senior+ programme). Developing a long-term housing strategy that considers the ageing population and the growing housing needs of seniors would reduce the population waiting for a place in nursing homes and the associated exorbitant costs for families and municipalities. Harnessing the potential of senior citizens and activating them would also facilitate the development of the so-called silver economy, thus responding to market demands in a number of fields and sectors. It would also be necessary to constantly monitor and assess how effective the implemented programmes are, a task that should be performed by the Supreme Audit Office.

5.10. Intersectoral collaboration

All the constituents of the senior housing policy advocated above require intersectoral collaboration of government agencies, NGOs, experts, and private businesses in order to create comprehensive solutions for the senior housing environment. One sign that this need has been recognised is a brand new addition to the government – a minister for senior policy. The inclusion of the said constituents can foster an effective senior housing policy that provides older, and often less able persons, with decent housing and support in their daily life.

6. CONCLUSIONS

The applied model for a senior housing policy is not only a direct product of the adopted social policy, but it is also determined by the current economic and political situation, and the cultural and demographic circumstances, which are subject to dynamic changes over time.

Since senior citizens differ substantially in needs and incomes, it is imperative to recognise both the needs of those facing poverty and social exclusion, and those who can easily afford to rent or buy a property that meets their changing needs. In all cases, improving housing means improving seniors’ lives, thus helping them to remain independent and self-reliant in their preferred place of residence, highlighting how important it is for the state to develop an effective housing policy. The economic, social, and societal safety of senior housing is affected not only by the aforementioned instruments, but also by housing options and efficient social care which helps to secure the fundamental requirements of seniors in their current place of residence. Although there are a number of measures to support older persons, they are only implemented to a limited extent. The most favourable climate for organisations that support seniors is found in large cities, which – due to the advanced demographic structure and greater needs among seniors – boast a well-developed social infrastructure and ample financial resources. In mid-sized towns, the situation is heterogeneous: some offer a variety of initiatives to benefit seniors, while others only provide basic care services. The most formidable challenge, however, is in rural areas, which lack well-structured and tailored support for the elderly in their place of residence. One source of hope for improving local initiatives aimed at seniors can be the fact that they are an active electoral group, which may motivate local decision-makers to take action on their behalf.

Despite the growing awareness of the unfavourable demographic trends, the local housing policy in Poland still focuses on economic development, competitiveness, and attracting new residents, while ignoring the potential of seniors and the silver economy. At the central government level, priority is given to constructing new housing, while the need to renovate existing homes is neglected, even though they could be adapted to the requirements of the expanding senior population. The current housing policy, centred on newly built but increasingly more expensive housing from property developers, is not particularly suited to seniors. An alternative could be the revival of communist-era type housing developments made up of large-panel-system blocks of flats, where – at a relatively low cost – a comfortable housing environment can be created for seniors and younger residents, offering them an optimum floor space of 40−60 sq. m in green surroundings and a familiar social space that promotes safety and comfort of living.

Autorzy

REFERENCES

ANDREWS, R. (2010), ‘Assisted living communities’, The RMA Journal, 93 (1), pp. 16−21.

ANDRZEJEWSKI, A. (1987), Polityka mieszkaniowa, Warsaw.

BELL, A. P., GREENE, C. TH., FISHER, D. J. and BAUM, A. (2004), Psychologia środowiskowa, Gdańsk: Gdańskie Wydawnictwo Psychologiczne.

BIELAK-ZASADZKA, M. and SZWEDA, D. (2022), ‘Kształtowanie przestrzeni kompleksu mieszkalnego dla seniorów na podstawie badań własnych’, Builder, 26 (8), pp. 34−37. https://doi.org/10.5604/01.3001.0015.9190

BŁĘDOWSKI, P. et al. (2017), ‘Model wsparcia społecznego osób starszych w środowisku zamieszkania’, [in:] SZATUR-JAWORSKA, B. and BŁĘDOWSKI, P. (eds), System wsparcia osób starszych w środowisku zamieszkania, Warsaw: Biuro Rzecznika Praw Obywatelskich, pp. 11−37.

BŁĘDOWSKI, P., SZATUR-JAWORSKA, B., SZWEDA-LEWANDOWSKA, Z. and KUBICKI, P. (2012), Raport na temat sytuacji osób starszych w Polsce, Instytut Pracy i Spraw Socjalnych, Warsaw.

BOJANOWSKA, E. (2008), ‘Opieka nad ludźmi starszymi’, [in:] SZUKALSKI, P. (ed.), To idzie starość – polityka społeczna a przygotowanie do starzenia się ludności Polski, Warsaw: Instytut Spraw Publicznych, p. 146, http://www.isip.org.

BOJANOWSKA, E. (2021), ‘Środowisko i miejsce zamieszkania w życiu osób starszych’, Polityka Społeczna, XLIII (11−12), pp. 10−16. https://doi.org/10.5604/01.3001.0015.5996

BOJANOWSKA, B. and KARWIŃSKA, M. (2018), Badanie ankietowe nt.: Postawy seniorów wobec starości i społecznych uwarunkowań starzenia się.

BUJACZ, A., SKRZYPSKA, N. and ZIELIŃSKA, A. M. (2012), ‘Publiczna przestrzeń miejska wobec potrzeb seniorów. Przykład Poznania’, Gerontologia Polska, 2, pp. 73−80.

CBOS (2022), “Sytuacja mieszkaniowa Polaków”, komunikat z badań nr 107/2022.

DUDA, T. (2014), Polityka mieszkaniowa a proces starzenia.

DUDEK-MAŃKOWSKA, S. (2017), Mieszkanie dla seniora – formy budownictwa senioralnego oraz stan ich rozwoju w Polsce, Konwersatorium Wiedzy o Mieście, 30. https://doi.org/10.18778/2543-9421.02.03

GAWRON, G. (2018), ‘Modelling the community support for seniors. The case studies in low-and middle-income countries’, Prace Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu, 510, pp. 32−48. https://doi.org/10.15611/pn.2018.510.03

GAWRON, G. (2023), Koprodukcja usług społecznych źródłem osobistej i społecznej produktywności osób starszych, Studium socjologiczne na przykładzie beneficjentów Programu Wieloletniego “Senior+”. Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego. https://doi.org/10.31261/PN.4156

GRADZIK, B. (2017), ‘Mieszkalnictwo senioralne a możliwości finansowe seniora’, Społeczeństwo i Ekonomia, 2 (8), pp. 71−82. https://doi.org/10.15611/sie.2017.2.05

GROEGER, L. (2016), Programy wspierania budownictwa mieszkaniowego w Polsce i ich wpływ na rynek nieruchomości mieszkaniowych, Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego, Łódź, pp. 139−140. https://doi.org/10.18778/1733-3180.18.09

GROEGER, L. and SZCZEREK, A. (2015), ‘Mieszkalnictwo ludzi starych’, [in:] JANISZEWSKA, A. (ed.), Jakość życia ludzi starych – wybrane problemy, Łódź: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego, pp. 187−213. https://doi.org/10.18778/1733-3180.14.11

JANCZ, A. and MANASTERSKA, T. (2023), ‘Preferencje mieszkaniowe seniorów w miastach średniej wielkości w Polsce’, Dziennik Zrównoważonego Rozwoju Transportu i Logistyki.

JANCZ, A. and TROJANEK, R. (2020), ‘Housing Preferences of Seniors and Pre-Senior Citizens in Poland – A Case Study’, Sustainability, 12 (11), 4599. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12114599

KRZYSZKOWSKI, J. (2018), ‘Deinstytucjonalizacja usług dla seniorów jako element polityki senioralnej’, Problemy Polityki Społecznej, Studia i Dyskusje, 42 (3), pp. 37−52.

KUBICKI, P. (2016), Miasto przyjazne seniorom, http://centrumis.pl/assets/files/konferencja-04-2016/1-Miasta_i_gminy_przyjazne_starzeniu.pdf

LIS, P. (2019), Polityka mieszkaniowa dla Polski. Dlaczego potrzeba więcej mieszkań na wynajem i czy powinno je budować państwo?, Forum Idei, Fundacja im. Stefana Batorego, Warsaw.

MAGDZIAK, M. (2017), ‘Typologia osób starszych pod kątem potrzeb mieszkaniowych’, [in:] SZEWCZENKO, A. (ed.) Badania interdyscyplinarne w architekturze, 3, Gliwice: Wydział Architektury Politechniki Śląskiej, pp. 93−105.

MELUCH, B. (2013), ‘Budownictwo mieszkaniowe dla seniorów – warunki realizacji przez fundusze inwestycyjne’, [in:] Finansowanie nieruchomości, 1 i 2.

MOSSAKOWSKA, M., WIĘCEK, A. and BŁĘDOWSKI, P. (2012), Aspekty medyczne, psychologiczne, socjologiczne i ekonomiczne starzenia się ludzi w Polsce, Poznań: Termedia Wydawnictwa Medyczne, pp. 169−180.

NIEZABITOWSKI, M. (2014), ‘Znaczenie miejsca zamieszkania w życiu ludzi starszych. Aspekty teoretyczne i empiryczne’, Problemy Polityki Społecznej. Studia i Dyskusje, 24 (1), pp. 81−101.

OSTROWSKA, M. W. (1991), Człowiek a rzeczywistość przestrzenna, Autorska Oficyna Wydawnicza “Nauka i Życie”.

PĘDZIWIATR, K. (2015), ‘Aktywizacja społeczna osób starszych w Polsce’, Space–Society–Economy, 14, pp. 123−136. https://doi.org/10.18778/1733-3180.14.07

PYTEL, S. (2014), Osiedla mieszkaniowe dla seniorów w przestrzeni miast, Prace Komisji Krajobrazu Kulturowego, 25, pp. 155−165.

ROWLES, G. D. (1983), ‘Place and Personal Identity in Old Age: Observations from Appalachia’, Journal of Environmental Psychology, 3, pp. 299−313. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(83)80033-4

SALOMON, M. and MUZIOŁ-WĘCŁAWOWICZ, A. (2015), Mieszkalnictwo w Polsce. Analiza wybranych obszarów polityki mieszkaniowej, Habitat for Humanity, Warsaw.

SOLAREK, K. (2017), ‘Trzy wymiary integracji w planowaniu dostępnych miast’, Studia KPZK PAN, 176, pp. 11−36.

SPASIEWICZ-BULAS, M. (2013), ‘Kształtowanie przestrzeni miejskiej przez i dla seniorów’, Zeszyty Pracy Socjalnej, 18 (3), Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego.

STRĄCZKOWSKI, Ł. and BORUTA, Z. (2018), ‘Warunki i decyzje mieszkaniowe seniorów na lokalnym rynku nieruchomości’, Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego w Krakowie, 3 (975), pp. 69−81. https://doi.org/10.15678/ZNUEK.2018.0975.0305

STRĄCZKOWSKI, Ł. and CELKA, K. (2012), ‘Opinie pośredników o stanie rynku mieszkaniowego, preferencjach klientów i możliwościach ich realizacji’, [in:] Potrzeby mieszkaniowe na lokalnym rynku nieruchomości mieszkaniowych i sposoby ich zaspokajania, Poznań: Katedra Inwestycji i Nieruchomości, Uniwersytet Ekonomiczny w Poznaniu.

SZAFRAŃSKA, E. (2010), Wielkie osiedla mieszkaniowe w okresie transformacji – próba diagnozy i kierunki przemian na przykładzie Łodzi, Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego, Łódź.

SZATUR-JAWORSKA, B. (2000), Ludzie starzy i starość w polityce społecznej, Aspra-JR, Warsaw.

SZATUR-JAWORSKA, B. (2015), ‘Polityka senioralna w Polsce – analiza agendy’, Problemy Polityki Społecznej. Studia i Dyskusje, 30 (3), pp. 47−75.

SZUKALSKI, P. (2017), ‘Sytuacja mieszkaniowa seniorów w przyszłości’, Demografia i Gerontologia Społeczna – Biuletyn Informacyjny, 11, pp. 1−6.

SZWEDA-LEWANDOWSKA, Z. (2023), ‘Wybrane ekonomiczne konsekwencje zmian demograficznych w Polsce-perspektywa krótko i długoterminowa’, Studia BAS (3), pp. 9−26. https://doi.org/10.31268/StudiaBAS.2023.22

TANAŚ, J., TROJANEK, M. and TROJANEK, R. (2019), ‘Seniors’ revealed preferences in the housing market in Poznań’, Economics & Sociology, 12 (1), pp. 353−369. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-789X.2019/12-1/22

TRZPIOT, G. and SZOŁTYSEK, J. (2015), ‘Analiza preferencji jakości życia seniorów w miastach’, Studia Ekonomiczne. Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego w Katowicach, 248.

TUROWSKI, J. (1979). Środowisko mieszkalne w świadomości ludności miejskiej, Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, Wrocław.

ZRAŁEK, M. (2012), ‘Zaspokojenie potrzeb mieszkaniowych osób starszych. Dylematy i kierunki zmian’, [in:] HRYNIEWICZ, J. (ed.), O sytuacji ludzi starszych, Rządowa Rada Ludnościowa, III, Warsaw, p. 104.

ZYCH, A. A. (2019), ‘Współczesna polska polityka senioralna: deklaracje i działania’, Praca Socjalna, 34, pp. 103−125. https://doi.org/10.5604/01.3001.0013.7260

REPORTS AND DOCUMENTS

Sytuacja osób starszych w Polsce w 2022, GUS.

“Senior +” na lata 2015–2020.

Recommendation CM/Rec(2014)2 of the Committee of Ministers to Member States on the Promotion of Human Rights of Older Persons.

Ustawa o pomocy społecznej z dnia 12 maja 2004 r. (Dz.U. z 2004 r., nr 64, poz. 593).

Ustawa z dnia 11 września 2015 r. o osobach starszych (Dz.U. z 2015 r., poz. 1705).

Plan na rzecz Odpowiedzialnego Rozwoju, 2017, Ministerstwo Funduszy i Polityki Regionalnej.

Polityka społeczna wobec osób starszych 2030. Bezpieczeństwo – uczestnictwo – solidarność, 2018, http://www.monitorpolski.gov.pl/mp/2018/1169/M2018000116901.pdf

Prognoza ludności na lata 2014−2050, GUS.

Habitat for Humanity Poland, 2023, Mieszkalnictwo w Polsce szanse i wyzwania w latach 2022–2023.

Jakość życia osób starszych w Polsce na podstawie wyników badania spójności społecznej 2015, 2017, GUS, Warszawa, http://www.stat.gov.pl/files/gfx/portalinformacyjny/pl/defaultaktualnosci/5486/26/1/1/jakosc_zycia_osob_starszych_w_polsce.pdf

Ogólnopolskie badanie liczby osób bezdomnych, 2024, Ministerstwo Rodziny i Polityki Społecznej, https://www.gov.pl/web/rodzina/ogolnopolskie-badanie-liczby-osob-bezdomnych

ONZ, Global Age Watch Index 2015, HelpAge International, London, 2015.

Opinia Europejskiego Komitetu Ekonomiczno-Społecznego w sprawie uwzględnienia potrzeb osób starszych, Dz. Urz., UE 2009/C 77/26.

Konstytucja Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej z dnia 2 kwietnia 1997 r. (Dz.U. z 1997 r. Nr 78, poz. 483).

FOOTNOTES

- 1 According to the CSO report entitled Situation of Older Persons in Poland [Sytuacja osób starszych w Polsce], the population of people aged 65+ could range from 9 to almost 11 million in 2050 depending on the scenario; at present, this population in Poland amounts to 7.5 million (CSO 2023).

- 2 Housing policy is defined as key directions and approaches taken by the state and by other public, political or social organisations that affect the housing sector and the provision of housing needs (Adam Andrzejewski, Polityka mieszkaniowa, Warsaw, 1987).

- 3 Jan Turowski (1979) studied the impact of the housing environment on shaping favourable living conditions for residents, distinguishing three main tiers of this environment. The first is the micro-environment, i.e., the space of the flat or house and its immediate vicinity. The second is a wider housing environment, i.e., the residential structure within the housing estate and the district, with its particular type of housing. The final, macro-environmental tier, encompasses extended urban systems, including roads, transport routes and networks, and any other urban infrastructure which affect the quality of life throughout the city.

- 4 CSO, Situation of Older Persons in Poland in 2022 [Sytuacja osób starszych w Polsce w 2022 roku].

- 5 National Survey on the Homeless Population by the Ministry of Family and Social Policy (2024); https://www.gov.pl/web/rodzina/ogolnopolskie-badanie-liczby-osob-bezdomnych [accessed on: 9.10.2024].

- 6 This CAWI survey was conducted on a representative sample of Polish men and women aged 18−65 via the ePanel.pl research panel.

- 7 Graham D. Rowles (1983) identified three key aspects of older people’s attachment to their place of residence: (1) social insideness, which refers to the level of integration with the social environment: the local community, social groups, neighbours, etc. (the so-called significant others); (2) autobiographical insideness, which is emotional attachment to places associated with significant life events and memories that evoke different stages of life; and (3) physical insideness, i.e., attachment arising from a sense of comfort and spatial orientation, based on familiarity with the physical features of the housing environment, formed through everyday experience (after: Bojanowska, 2021).

- 8 Income in a single-person household; costs converted to a floor area of 35 sq. m; allowance applicable irrespective of the legal title to the home occupied.

- 9 Measures to support seniors in retaining their independence include, inter alia, the Nie Sami Programme in Stargard Szczeciński and the Workers’ Initiative Programme called Mieszkanie na Winogradach in Poznań. As part of the former, a building with twenty-four flats for let to people aged 55+ was built in 2009. As for the latter, an old flat in Poznań was renovated to create sheltered housing. It comprises four bedrooms, a kitchen with a dining area, a bathroom and a toilet (Dudek-Mańkowska, 2017).

- 10 Poland’s first housing complex for seniors, called Senior Apartments, was built in the municipality of Wiązowna near Warsaw (https://seniorapartments.pl). The complex consists of eighteen detached houses and offers a wide range of support services, including catering based on customised diets, nursing care, 24/7 medical care, consultations with a GP and a physiotherapist, 24/7 supervision for emergencies, private assistance (concierge), housekeeping assistance (e.g., cleaning), to-door grocery deliveries, and Internet access. As of 2024, the monthly long-term rent for a single room was 2,790 zlotys and for a whole apartment: 5,790 zlotys; the prices did not include fees for the extra services offered.

- 11 In Poland, 126,425 households are on waiting lists for social or council housing (CSO, as of 31 December 2022).

- 12 One measure to support older persons in legal matters is free legal aid, which is available at senior day centres and as part of the government programme called Free legal Aid and Citizens Advice [Darmowa pomoc prawna i poradnictwo obywatelskie] (darmowapomocprawna.ms.gov.pl). Another worthy initiative, modelled on solutions employed in the West, is the “sliver haired legislature,” – a panel of deputies elected by seniors to identify and promote legislative priorities relevant to seniors and to exert pressure on legislative bodies to implement these regulations on the local and national scales. There is also a number of local initiatives in Poland to support seniors in legal and economic matters, e.g., the economic security and debtor support programme implemented in Gdańsk, the Academy of Law for Seniors project [Akademia Prawa dla Seniorów] run by the Warsaw Bar Association, and the research projects of the Warsaw Legal Education Foundation: On Law for Seniors [O prawie dla seniorów] and Survey of Seniors’ Needs [Badanie potrzeb seniorów], which delve into legal and economic needs among the group in question (Zych, 2019).