Volume 31, 2024, Number 1

https://doi.org/10.18778/1231-1952.31.1.02

Abstract. German settlement in Poland has been the subject of numerous studies. The causes and determinants of migratory movements have been discussed extensively, while little attention has been paid to the spatial aspects of the phenomenon. The aim of this study, which is part of geographical and historical research, is to determine the size of the influx of migrants of German nationality into the rapidly developing textile production centre of Łódź in the 19th century, as well as the geographical origins and distribution of this nationality group in the urban space. These considerations are complemented by the identification of key issues related to the social integration and assimilation processes of the German minority. In the first half of the 19th century, the influx of skilled labour, almost entirely recruited from the German population, conditioned the development of the textile industry in Łódź. It also had a key influence on the demographic development of Łódź, which soon became the largest centre of textile production in Poland. In subsequent decades, there was a tendency among German immigrants towards separation in the sphere of professional and social activities, but already by the end of the 19th century the German community settled in Łódź was diverse in terms of the sense of nationality. In addition to a certain proportion of the immigrants who were already Polonised, there were persons declaring German nationality, as well as those undecided about the issue.

Key words: German settlement, national minority, Łódź, migration.

Germans have been settling Polish lands for centuries. German settlement, spontaneous until the middle of the 18th century, grew significantly towards the end of the century. Colonisation, mainly limited to rural settlements, over time increasingly involved an influx of German people into towns and newly established craft settlements. The beginnings of German settlement in today’s Łódź urban agglomeration date back to the last decades of the 19th century. A particularly intense influx of this ethnic group was brought by the period of 19th century industrialisation. However, until the early 1820s, immigrants generally avoided the typically agricultural and neglected Łódź[1], which was surrounded by a ring of German peasant settlements established in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

The creation of the Kingdom of Poland in 1815 allowed the initiation of measures to promote the economic development of the country. Łódź was among the settlement units indicated by the Polish government as particularly predisposed to industrial development – a small settlement with several hundred inhabitants, a de facto rural stead, though formally possessing a charter.

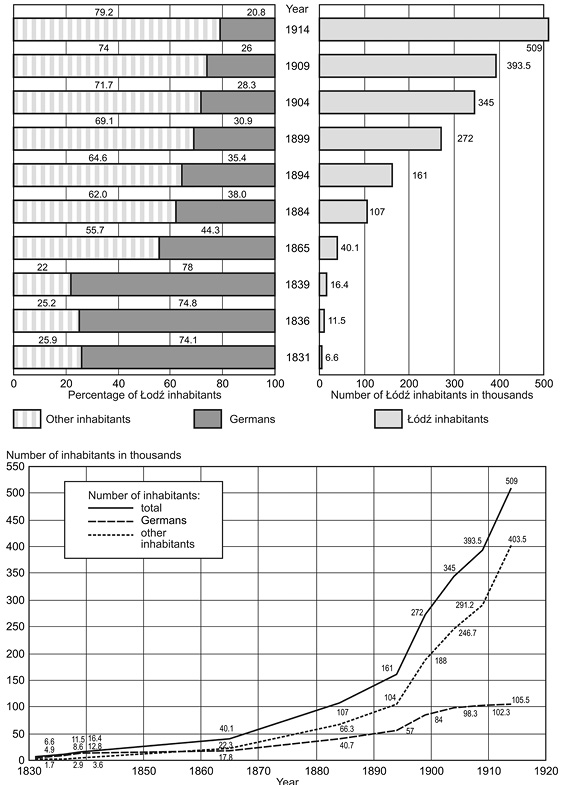

As a result of the measures taken by the government, Łódź experienced rapid economic development, with the number of inhabitants increasing more than sixfold in the third decade of the 19th century alone, reaching 4,700 by 1831. This demographic development was primarily the result of an influx of German settlers, whose share of the city’s population reached 75% by the 1830s. The decrease in this ratio in the following decades did not mean a decrease in the number of German inhabitants in Łódź – it was only the result of the spontaneous and rapid development of this industrial centre, which was associated with a rapid influx of Polish and Jewish people into the city. Łódź, which still had a population of just over 30,000 in the mid-19th century, grew to around 300,000 inhabitants by the end of the century, and the city – still the largest concentration of German origin population in Central Poland – was inhabited by three nationality groups of a roughly similar sizes: Polish, Jewish, and German.

The issue of German settlement in Poland has been the subject of numerous studies by both Polish and German historians. The causes and determinants of migratory movements have been discussed extensively, while little attention has been paid to the spatial aspects of this phenomenon, especially in the Łódź region. The aim of this study, which is part of geographical and historical research, is to determine the size of the influx of migrants of German nationality into the rapidly developing textile production centre of Łódź in the 19th century, as well as the geographical origins and distribution of this nationality group in the urban space. The discussion of the spatial aspects of German settlement in Łódź is complemented by the identification of key issues related to the processes of social integration and assimilation of the German national minority.[2]

German rural settlement reached the area of Łódź in the 1780s. During the last two decades of this century, a number of new settlements populated by German immigrants were established in the royal and private estates in the area of the present-day urban agglomeration of Łódź.[3]

In 1793, as a result of the Second Partition of Poland, the Łódź region found itself within the borders of the Prussian state, whose authorities pursued a policy of settling German population in the newly occupied areas. Prussian colonisation de facto continued the earlier settlement processes of the pre-partition period.[4] The Prussian colonisation campaign was most intense between 1801 and 1806. Newcomers settled in existing villages or in new locations built from scratch. The area in which the colonisation campaign was undertaken in the early years of the 19th century was the secularised Łaznów estate (as well as the Wiączyń and Gałkówek estates).[5] In the autumn of 1800, 39 Swabian families were brought from southern Germany to Łaznów, for whom fifty plots of land of about 15−16 ha each were prepared in Łaznowska Wola (Grömbach).[6] New German agricultural colonies were established on government dominion land.[7] The largest and wealthiest Swabian village on Polish soil was Nowosolna (Neu-sulzfeld), to which the first sixty families arrived from Württemberg, Baden, Alsace, and the Palatinate in 1801 (Woźniak, 2015, p. 110).[8] As Germans came, owners of private estates near Łódź (including Stoki, Mileszki, Bedoń, and Chojny), ceded land to them (often lying fallow) in their estates for a small rent (see Rynkowska, 1960, p. 36).

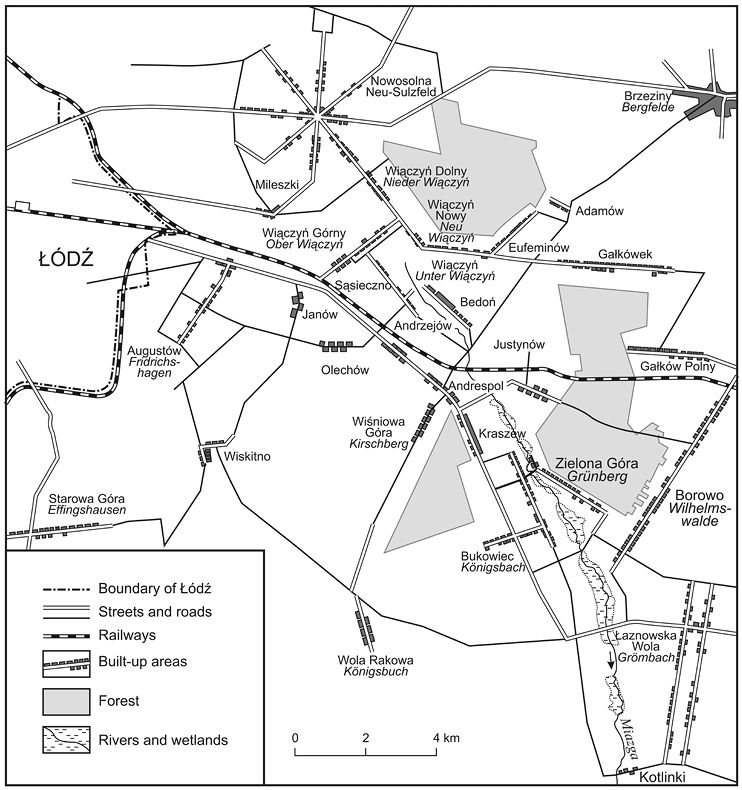

Fig. 1. German settlement until 1815 in the areas east of Łódź

Source: own work based, among others, on Schmit, 1942.

According to the recommendations of Prussian authorities, newly founded villages were to be settled exclusively by German settlers – Nowosolna and Olechów were purely German. But since German colonisation also extended to villages already in existence in many settlements, some of the inhabitants were also of Polish nationality.[9]

The number of settlers arriving from Bavaria, Württemberg, and the Palatinate (see Kossmann, 1985, p. 147), and in the following years also from Poznań and Prussia[10], grew particularly rapidly in Nowosolna, which in the last years of the Prussian rule surpassed Łódź in terms of population.[11]

During the Prussian period, German-speaking newcomers also settled many other towns in the region and thus, even before 1815, the sparsely populated forested area around the small town of Łódź was becoming a region of increasingly intensive agricultural production. A particularly strong concentration of German settlement was in the area to the east of Łódź (see Fig. 1). In the following decades of the 19th century, a number of settlements settled by German colonists were incorporated into the borders of the rapidly developing industrial Łódź. The names of many inner-city settlement units and locations in the suburban zone of contemporary Łódź are related to the names of former settlements.

The turn of the 18th century was a period of an influx of German colonists mainly in rural areas. But it was also a time marked by some, initially small, movements of craftsmen of German nationality into the cloth production that was developing in many centres.[12]

After the Congress of Vienna, Łódź found itself within the borders of the Kingdom of Poland, established in 1815 and until First World War linked to the Russian Empire. In its first period of existence, until the outbreak of the 1830 uprising, its large autonomy allowed it to pursue its own economic policy aimed at the industrialisation of Poland. The government identified a number of centres designated for industrial development, while guaranteeing them support in the form of a number of privileges. The choice of Łódź and the surrounding area for the development of textile production was determined primarily by its favourable natural conditions: sufficient supply of water allowing the placement of the fulling and dyeing plants, numerous small rivers with rapid currents as a source of energy, and forests providing material for the construction of houses.

The turning point in the development of Łódź came in the 1820s when, as a result of a well-planned action by the government of the Kingdom of Poland, a textile production centre was established here.[13] Securing a workforce with the right skills and capital was a key condition for ensuring development. To this end, an extensive campaign was launched to bring in settlers mainly from Germany, but also from Bohemia and former Polish territories (Silesia and the Grand Duchy of Posen, where a large proportion of the population was of German nationality). Clothiers, weavers, and spinners were eager to migrate, motivated partly by the situation in their countries of residence, where textile manufacturing was in crisis due to competition from English mechanised mills. In the Kingdom of Poland the government protected domestic production through a system of protective tariffs.

Among other things, the settling clothiers were offered free land for construction and free building materials (cf. Janowicz, 1907, p. 18). In government towns set up as factory settlements, under the 1820 decree of the royal governor, the immigrants settling there were provided with, among others, the opportunity to live in low-rent houses built by the government[14], free timber to build houses, and assistance in building an evangelical church and housing for the pastor (Gąsiorowska, 1965, p. 74). The children of the settlers were able to study in schools in their native language. The government also provided loans for the purchase of workshops and raw materials for production. Settlers were exempted from paying taxes for the first few years, and their sons were not required to perform military service. A further decree was issued in 1823, which not only confirmed but also extended the previously granted benefits. In 1824, assurances were given to factory owners that in the next decade the ban on imports of cloth products would not be revoked or amended, and the right to import materials needed for production from abroad would be maintained (Koszutski, 1905, p. 44). The government attached particular importance to the construction of water facilities, fulling mills and bleacheries, supporting these investments organisationally and financially. To receive support, one had to be suitably qualified and to fulfil certain previously accepted obligations, under the threat of losing rights to the allotted parcel of land and eviction.

The situation of industrial settlers in the Kingdom of Poland was secured from the legal point of view by agreements concluded with state authorities (and municipal after 1827) in the case of government towns, or with owners in the case of private estates.

The influx of industrial settlers to the previously omitted Łódź was initiated by the preparation in 1822 of 202 plots of land in the newly established clothmaking settlement of Nowe Miasto (Flatt, 1853, pp. 61–62).

The first foreigner to initiate the development of industrial Łódź was Karol Sänger, who came from Chodzież. Thanks to him, in the autumn of 1823, the first group of immigrants arrived in Łódź − a dozen or so master clothiers and a shearer from Saxony, as well as several experts in the construction of weaving workshops and houses. Between 1823 and 1825, nearly 200 skilled craftsmen settled in the town, most of whom (around 60%) were weavers. The establishment of a settlement for cotton and linen weavers with 307 plots in 1824 and a settlement for linen spinners with 167 plots in 1825 in the following years resulted in a further fast-growing migration of skilled German settlers. The first cotton weavers arrived in September 1824.[15]

Many of the industrial settlers came from Saxony, a region with liberal migration policy, where the textile industry, which had developed strongly in the 17th and 18th centuries, was experiencing difficulties after the loss of eastern markets. Impoverished Saxon weavers migrated en masse to the Kingdom of Poland from the mid-1820s until the outbreak of the November Uprising. The influx of Saxon settlers was particularly intense between 1824 and 1830, and between 1837 and 1844 (Missalowa, 1964, pp. 76, 83). Most of them, including many cotton weavers, headed for Łódź and the surrounding textile production centres.

Migrants arriving in Łódź, which was becoming a fast-growing industrial centre, mostly came from: (cf. Rynkowska, 1951, pp. 31–35; Bajer, 1958, p. 53)

The first settlers to arrive in Łódź were mainly Saxons and Germans from Bohemia (North Bohemia). In the following years, the number of refugees from Silesia grew (Staszewski, 1931, p. 264).

In the first Łódź settlement, “Łódka”, settled between 1825 and 1830, about half of the settlers came from Saxony, about a third were immigrants from Bohemia, and the rest were almost exclusively from Prussian Silesia (Rynkowska, 1951, p. 34).

One of the first activities of the immigrants coming to the city was associating in craft guilds. In 1824, the linen makers guild and the clothiers guild were established in Łódź (Rynkowska, 1951, pp. 210−211). In 1825, the Master Craftsmen House (“Meisterhaus”) was opened and became the centre of social and cultural life for German craftsmen. In the same year, a brotherhood of apprentice weavers became active. In later years guilds were organised in Łódź grouping representatives of other professions (Sztobryn, 1999, p. 15).

A special government commissioner was sent to Saxony, Bohemia, and Prussia to recruit industrialists with more substantial capital. These activities bore fruit and in the second half of the 1920s, Łódź welcomed, among others: Frederick Wendisch from Chemnitz (Saxony), Daniel Ill from Groschönau (Saxony), Jan Traugott Lange from Chemnitz (Saxony), Ludwig Geyer from Neugersdorf near Lobau (Saxony), and Tytus Kopisch from Schmiedeberg (Lower Silesia). Some of them, after settling in the Kingdom, took over government production facilities.[16] The arrival of wealthier factory owners meant that the previous equality of economic positions among the settlers was disturbed, and that small-scale manufacturers, often working domestically, became a link in a production chain dependent on wealthier entrepreneurs.

The spatial development of the textile production centre of Łódź was complemented by the establishment of the Ślązaki weaving and spinning settlement with 42 plots in 1828. All these government actions resulted in a total of 366 plots of land being taken over by immigrants arriving in Łódź by 1829 (see Staszewski, 1931, p. 272). As early as 1826, the first German school, subordinate to the municipal authorities, for the children of the settlers – an Evangelical primary school – was set up in Łódź.

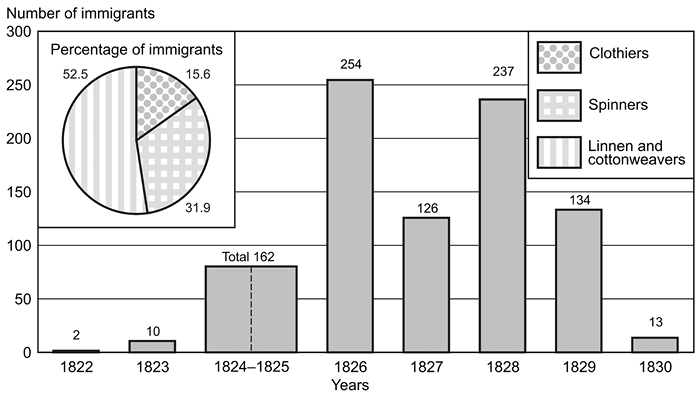

In the 1820s (up to the outbreak of the November Uprising), around a thousand immigrant craftsmen of German origin, together with their families, settled in Łódź – which still had a mere 799 inhabitants in 1821 – which means an estimated arrival of around 4,000 people of this nationality.[17] The influx of migrants, among whom cotton and linen weavers predominated, was particularly intense between 1826 and 1829 (cf. Fig. 2).

As a result of the demographic processes taking place in the third decade, the nationality structure of Łódź changed completely, and by the turn of the 1820s it had become a city with a large proportion of immigrant German-speaking population and one of the main German population centres in Central Poland.[18] The immigrant nature of Łódź’s demographic development is confirmed by data stating that in 1839 as many as 68% of its permanent inhabitants were allochthones (born outside the city).[19]

Fig. 2. Number and occupational structure of migrants settled in Łódź from 1822 to 1830

Source: own work based on A. Rynkowska, 1951.

In the pre-uprising decade, industrial settlers dominated among the newcomers from Germany. The influx of skilled labour, almost entirely recruited from the German population, conditioned the development of the cloth industry, both in Łódź and in other textile manufacturing centres in the Kingdom of Poland. The period of the first increased influx of German craftsmen into Polish industry, the greatest intensity of which occurred in the middle of the third decade of the 19th century, ended with the outbreak of the November Uprising.

The November Uprising and the difficult political situation after its collapse – reflected in the restriction of the Kingdom of Poland’s independence in the sphere of economic policy – were of great significance from the point of view of German settlement. Opportunities for productive investment declined and the effects of the first major economic crisis, which lasted for several years, were felt particularly strongly by German craftsmen involved in textile production. The uprising resulted in the economic crisis of 1830−1834, which put much of the immigrant German population out of work. For many clothiers in the Łódź region, the outbreak of the uprising spelled economic disaster. The effects of the ongoing hostilities were compounded by retaliatory changes in Russia’s economic policy – a reduction in Polish-Russian trade relations, cutting off sources of raw materials and markets. These steps were particularly acute in a situation of very few orders placed by the Polish government for the military.

But already the years 1837−1845 brought a second wave of migration of craftsmen from Saxony, who headed primarily for Łódź and the surrounding manufacturing centres. As in the second half of the 1820s, the largest number of migrants came from eastern Saxony (the area around Chemnitz and Dresden), where a strong textile manufacturing area developed near the border with Bohemia (cf. Missalowa, 1964, p. 78). The Saxon migrants almost exclusively consisted of skilled weavers and professionals familiar with textile machinery, and only a very small group of unskilled labourers. After 1845, the influx of new migrants from Saxony almost completely stopped. Between 1837 and 1845 there was also an influx of craftsmen from Bohemia and Moravia, mainly from the northern Sudetenland adjacent to the Saxon border. It was a region with a predominantly German population, so the majority of newcomers were from this nationality group. The incoming settlers from Bohemia, unlike those from Saxony, were not always highly qualified professionally and, in terms of occupation, it was a much more diverse migration, with a high proportion of labourers and poor people.

In 1861, among the 383 journeymen temporarily living in Łódź (on temporary passports) and employed in textile production, about half came from the Prussian partition, nearly a third from Saxony, almost a fifth from Bohemia and Moravia, while only a couple of people came from other German-speaking regions.[20]

The crisis following the collapse of the November Uprising, caused by Russia’s restrictive policy and the introduction of customs duties on cloth exports to that country, proved short-lived and in the long term had little impact on Łódź’s booming industrial production. As early as in the second half of the 1830s and early 1840s, as a result of a strong influx of German industrial settlers, the number of Łódź inhabitants increased significantly. Between 1833 and 1845, Łódź recorded a more than threefold increase in population (from 5,700 to nearly 17,300) (Janowicz, 1907, p. 29) and became the second largest city in the Kingdom of Poland, after Warsaw (Janczak, 1982, p. 50).

According to O. Kossmann’s estimates, probably slightly overestimating the number of people of German nationality in Łódź[21], this ethnic group in the first half of the 1830s accounted for nearly three-quarters of the city’s population, and by the end of that decade its share further increased slightly (see Table 1). However, the population of German nationality given by the magistrate of Łódź in October 1851 was undoubtedly underestimated at 5,800 (1,440 families), which accounted for 32% of the city’s permanent residents (Rynkowska, 1960, table after p. 86). According to E. Rosset, in 1857 Łódź had a population of 26,100, of which 41.1% (10,700) were German, while in 1860 it had 32,600 inhabitants, of which 37.3% (12,200) were ethnic Germans (Rosset, 1928, p. 336). These figures for the German minority, due to underreporting, are highly debatable.[22]

| Nationality | Year | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1831 | 1836 | 1839 | ||||

| thousand | % | thousand | % | thousand | % | |

| Polish | 0.8 | 17.4 | 0.8 | 13.9 | 1.1 | 13.2 |

| German | 3.5 | 74.1 | 4.4 | 74.8 | 6.7 | 77.7 |

| Jewish | 0.4 | 8.5 | 0.7 | 11.3 | 0.8 | 9.1 |

| Total | 4.7 | 100.0 | 5.9 | 100.0 | 8.6 | 100.0 |

Source: Kossmann, 1936, pp. 28−29, 47; and Kossmann, 1966, p. 164.

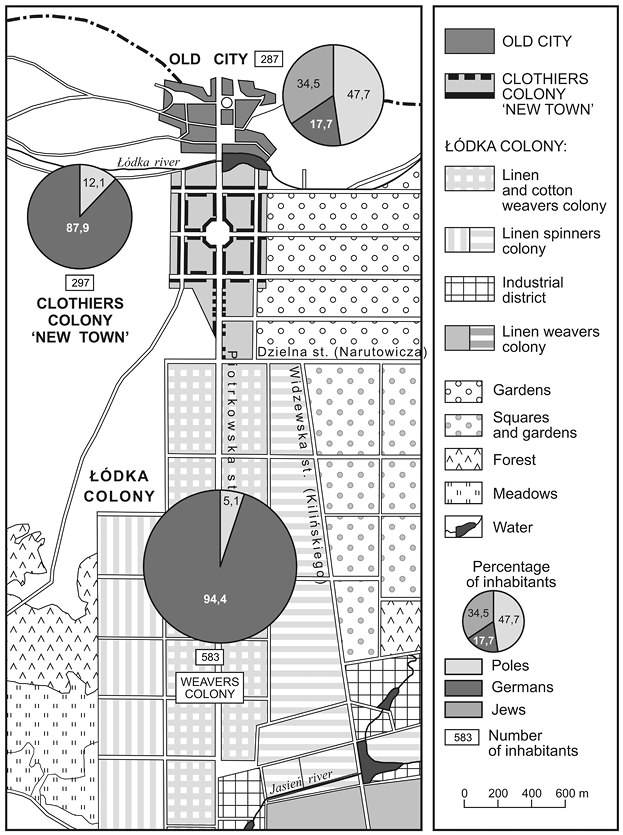

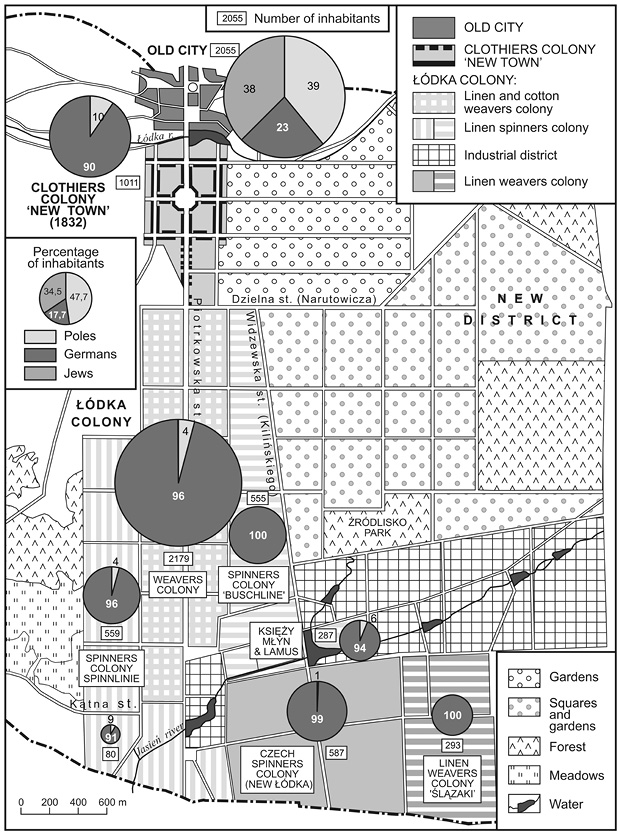

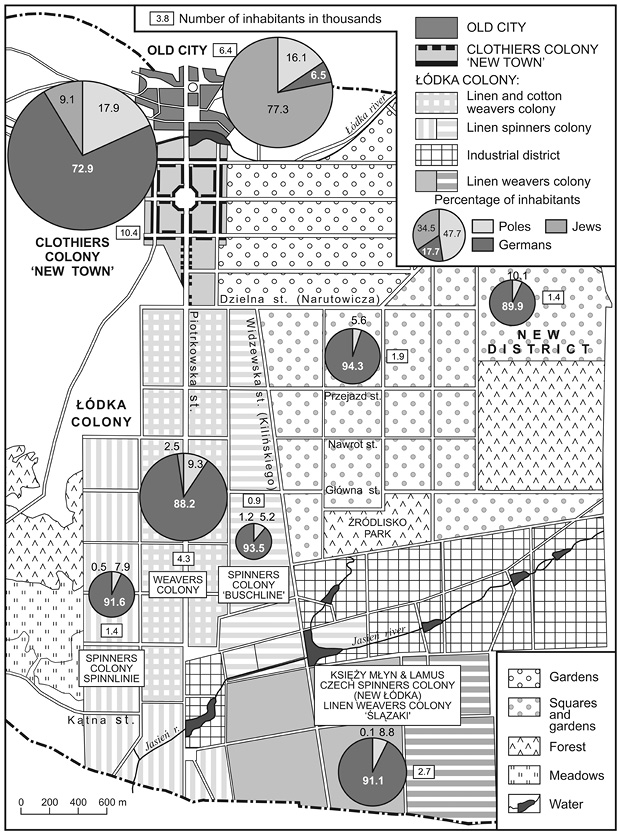

In the 1830s, the number of inhabitants of German nationality in Łódź almost doubled. Its largest concentration throughout the fourth decade of the 19th century was the weaving settlement located along the town’s main street, which in 1839 was home to just under 2,200 settlers, almost exclusively of German nationality. Similarly high, exceeding 90%, was the proportion of representatives of this ethnic group in the remaining districts of Łódź, except for the “Old Town” (cf. Fig. 3 and Fig. 4). In the “New Town”, already in 1832 with a population of more than 1,000 inhabitants, 9 out of 10 people were of German nationality. The nationality structure in the oldest part of Łódź, or the “Old Town”, was quite different, where Poles remained the most numerous ethnic group in the 1830s. However, their percentage gradually decreased, mainly in favour of the Jewish population and those of German origin (cf. Fig. 3 and Fig. 4). In this northernmost part of the city, the percentage of the German minority did not exceed a quarter in the late 1830s.

Fig. 3. Nationality structure of the population of Łódź (by number of families) in 1831 by districts

Source: own work based on: Kossmann, 1936, p. 28; Kossmann, 1966, p. 151; and Kossmann, 1985, p. 39.

Fig. 4. Nationality structure of the population of Łódź in 1839 by districts

Source: own work based on: Kossmann, 1936, p. 30; Kossmann, 1966, p. 152; and Kossmann, 1985, p. 40.

At the end of the 1830s, a sizeable proportion, up to one-fifth, of the population of Łódź was made up of the next generation of settlers who had already been born in the city. Overall, one in three inhabitants of Łódź of German nationality had a place of birth in the Kingdom of Poland. The proportion of settlers coming from the Bohemian Sudetenland (about a quarter), Prussia (about one-fifth) and Saxony (about one-seventh) was significant. There were distinct differences in the territorial origin of the inhabitants between the different districts – created at different times as the city developed and differing in the nature of the productive activities carried out in them. This was probably because migrants coming from a certain region and often representing similar professional qualifications often came to Łódź in larger groups. There was a large proportion of Prussians in the “New Town”, while the weaving settlement had more inhabitants from Saxony (see Table 2). In the linen colony “Ślązaki” and the spinning colony “Nowa Łódka”, Germans from the Czech Sudetenland dominated among the settlers, while in “Księży Młyn” and the “Lamus” area, migrants from Hesse were most numerous.

There was also a significant group of Catholics among the German immigrants settling in Łódź, most of whom were of the Protestant faith. The Catholics largely came from the Czech Sudetenland (Sudeten Germans) and settled in the south-eastern part of the “Łódka” settlement, south of the Jasień River valley, in the spinning settlement along the “Böhmische Linie” (“New Łódka”), where they made up the majority of the population in 1839. The newcomers from Silesia formed a cluster in the former Zarzew area along the so-called “Schlesische Linie” (“Schlesing”/ “Silesians”) in the linen settlement, where their share of the total population reached almost two-thirds.

| District | Place of birth (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Łódź | Kingdom of Poland | Saxony | Bohemia | Prussia | Hesse | South Germany | unknown | |

| “Old Town” | 26 | 23 | 4 | 15 | 20 | 6 | 4 | 2 |

| Clothmakers’ settlement “New Town” – 1832 | 18 | 17 | 10 | 13 | 37 | - | 0 | 5 |

| Weaving settlement | 21 | 10 | 24 | 20 | 20 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| “Spinnlinie” spinning settlement | 23 | 10 | 5 | 10 | 34 | 16 | 2 | 0 |

| “Przy Kątnej” | 20 | 22 | 7 | 26 | 18 | 7 | - | - |

| “Buschlinie” spinning settlement | 21 | 9 | 21 | 19 | 17 | 7 | 3 | 3 |

| “Księży Młyn” and “Lamus” | 24 | 17 | 3 | 3 | 16 | 26 | 5 | 6 |

| Czech spinning colony “Nowa Łódka” | 22 | 6 | 1 | 51 | 16 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Linen colony “Ślązaki” | 20 | 1 | - | 63 | 14 | 2 | - | - |

| TOTAL (without “New Town”) | 22 | 11 | 14 | 24 | 20 | 5 | 2 | 2 |

Source: own work based on: Kossmann, 1936, pp. 35−36; Kossmann, 1966, p. 155; and Kossmann, 1985, p. 41.

The occupational structure of German immigrants settled in the cities shows their involvement primarily in activities related to the sphere of industrial production and crafts. In Lodz, the largest urban centre of the German minority, in 1851, 1,125 settler families were making a living from manufacturing activities while only seventeen were involved in trade.[23]

Already in the 1930s, with the influx of representatives of other non-textile professions to Łódź, the gradual professional diversification of the German nationality group was marked. In 1836, in addition to the guilds of clothiers and cotton and linen weavers, the guilds of carpenters, butchers, millers, bakers, tailors, and hosiery makers appeared in the register of the Łódź magistrate (Sztobryn, 1999, p. 15). Over time, the second half of the 19th century saw a declining share of the German minority in the total number of employees in the rapidly expanding industry, in which the growing demand for labour was increasingly met by an influx of workers of Polish nationality. At the same time, the proportion of ethnic Germans in the non-manufacturing sectors of the economy gradually increased.[24]

Immigration to Łódź was accompanied by the development of German education, to which the newcomers attached great importance. Between the uprisings, there were two elementary schools in the town for the children of German settlers. In 1845, a four-grade German-Russian District Real School was established in Łódź. And in 1862, two more new evangelical schools were opened (Sztobryn, 1999, p. 95-97).

In the first half of the 19th century, German settlement was a crucial element stimulating the economic development of the country and was one of the main sources of the demographic development of Central Poland and Łódź, which at that time became a thriving centre of textile production, the largest in the country.

After the January Uprising (1863−1864), in 1865, Łódź had a permanent population of 32,400. A key component of the demographic and economic potential of this largest urban centre in Central Poland continued to be the population of German nationality, amounting to 14,400 (Janczak, 1982).[25] The proportion of the population of German origin exceeding 44% was higher than the proportion of Lutherans in the total population, since a number of members of this ethnic group were of Catholic faith (cf. Janczak, 1997, p. 44). There were four Protestant elementary schools in the town, and in 1866 the first seven-grade German secondary school was opened (Rosset, 1928, pp. 355–356).

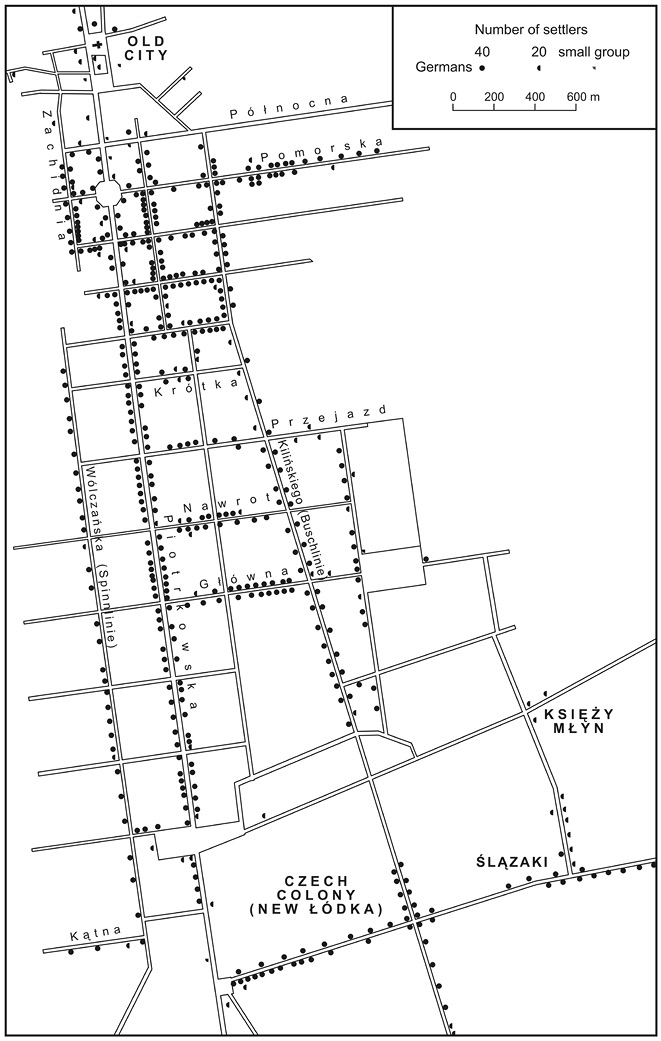

In the initial period of the influx of German craftsmen to Łódź, the migrating craftsmen settled mainly in the newly established industrial settlements, which involved a strong spatial concentration of this nationality group. A certain weakening of the degree of spatial segregation of the German population in the urban space came in the 1840s and 1850s. At that time, in comparison with the 1830s, a slightly greater diversification of the nationality structure of industrial settlements and a more even distribution of the German nationality group were noticeable (cf. Fig. 5 and Fig. 6).

Fig. 5. Nationality structure of the inhabitants of Łódź in 1864 by district

Source: own work based on Kossmann, 1966, p. 160.

Fig. 6. Distribution of the German population in Łódź in 1864

Source: own work based on Kossmann, 1966, annex 22.

In the mid-1860s, in the “Old Town”, with a population of 6,400 (more than 3-fold increase since 1839), dominated by the incoming Jewish population, Germans, whose total number remained unchanged over the past quarter of a century (400), accounted for only 6.5% of the total population. In the “New Town”, despite a significant increase in the number of people of German nationality (from 900 in 1839 to 7,600 in 1864), the share of this ethnic group in the total number of inhabitants of the district gradually decreased and just after the January Uprising did not exceed three-quarters (Fig. 5). In all other districts of the city, although the proportion of ethnic Germans had also been slowly decreasing over the past 25 years (4−8%), in 1864 only one in ten people were of non-German nationality.

By the mid-1860s, more than half of the city’s inhabitants of German nationality were born in Łódź, and another quarter were born in other towns in the Kingdom of Poland. The territorial origin of emigrants arriving from outside the Kingdom and living in Łódź in 1864 was dominated by newcomers from Bohemia (Sudeten Germans), with a relatively small share, compared to the 1820s and 1830s, of settlers coming from Prussia (cf. Table 3). The post-uprising period also saw a certain disappearance of the spatial segregation of the German nationality population coming from different regions in the various industrial settlements of Łódź, still quite pronounced at the end of the 1830s.

| District | German population (%) | Immigrants from (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| born Łódź | immigrants | Kingdom of Poland | Saxony | Bohemia | Prussia | other and unknown | |

| “Old Town” | 57 | 43 | 58.5 | 2.8 | 8.5 | 20.8 | 9.4 |

| Clothmakers’ settlement “New Town” | 55 | 45 | 54.8 | 9.4 | 10.0 | 18.3 | 7.6 |

| Weaving settlement | 58 | 42 | 46.6 | 14.9 | 14.7 | 15.2 | 8.7 |

| “Spinnlinie” spinning colony | 56 | 44 | 42.6 | 10.6 | 11.5 | 20.5 | 14.8 |

| “Buschlinie” spinning colony | 55 | 45 | 43.3 | 15.2 | 21.7 | 12.0 | 7.8 |

| Czech spinning colony “Nowa Łódka”, linen colony “Ślązaki”, “Księży Młyn” and “Lamus” | 58 | 42 | 41.2 | 5.2 | 32.0 | 13.7 | 7.9 |

| “New Quarter” | 53 | 47 | 47.1 | 14.8 | 15.0 | 12.2 | 10.8 |

| Krótka (now Traugutta), Przejazd (now Tuwima), Nawrot, Główna (now Piłsudskiego) streets | 57 | 43 | 46.6 | 14.4 | 19.8 | 12.2 | 7.1 |

| TOTAL (without New Town) | 56 | 44 | 49.1 | 11.1 | 15.1 | 16.1 | 8.6 |

Source: Kossmann, 1966, p. 155.

During the final three decades of the 19th century, the number of people of German nationality in Łódź doubled, also as a result of the population flow from neighbouring industrial centres. At the same time, the proportion of this ethnic group in the total population of the rapidly growing city saw a sharp decline. Data from various sources give rather different estimates of the German minority in Łódź at the turn of the 19th century. The government census carried out in 1903 showed 90,800 people of German nationality, i.e., 28% of the total population (313,100).[26] However, according to the 1911 census, the number of people of German nationality in Łódź amounted to approximately 80,000 (Informator Miasta Łodzi, 1918, p. 25). These figures do not quite correspond with the data presented in Fig. 7 (in the author’s opinion the most reliable), according to which just before the outbreak of First World War Łódź was inhabited by 105,500 people of German nationality, which accounted for slightly more than one-fifth of the city’s population.[27] These discrepancies, as far as they are within certain limits, should not be surprising in light of the impossibility of establishing an objective criterion of nationality.

In the post-uprising period, as a result of a massive influx of Polish (mainly rural) and Jewish (from western Russian governorates and small towns in the Kingdom of Poland) inhabitants to Łódź and the gradual process of polonisation of some newcomers from across the western border of the Kingdom of Poland, the proportion of the German minority in the total population of the city decreased (cf. Fig. 7). The German population, which had been the dominant national group since the time Łódź was transformed into a factory town until the January Uprising, steadily decreased its share of the city’s demographic potential in the following decades and by the outbreak of the First World War accounted for only about a quarter of the city’s population.

Despite a decrease in the share of the German population in the total number, the development of industrial Łódź in the last decades of the 19th century was linked to the key role of this ethnic group in the city’s economic potential.

In 1865, among the 388 owners of Łódź industrial plants, centralised manufactories and craft workshops employing more than five people, as many as 245 (63.4%) belonged to people of German nationality (cf. Table 4). In the 1880s and 1890s, the percentage of ethnic Germans among Łódź entrepreneurs was around 53−57% and only dropped to 44% before the outbreak of First World War. While Jews prevailed among the petty bourgeoisie, people of German nationality were far more numerous among medium-sized and especially large entrepreneurs, as well as in all non-textile branches of industry.[28] Significantly, Łódź’s industrial plants were among the most technically and organisationally advanced in the Russian Empire.

Fig. 7. Population of German nationality in Łódź 1831−1914

Source: own elaboration based on: „Pierwaja wsieobszczaja pierepis…”, 1905, pp. 246−247; Janczak, 1982, pp. 108−109; Kossmann, 1966, p. 158.

| Year | Industrialists of German nationality | Industrialists total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Textile industry | Other industries | |||||

| number | % | number | % | number | % | |

| 1865 | 242 | 62.4 | 3 | 0.8 | 388 | 100 |

| 1869 | 185 | 58.4 | 3 | 1.0 | 317 | 100 |

| 1879 | 126 | 42.0 | 21 | 7.0 | 300 | 100 |

| 1884 | 101 | 46.3 | 23 | 10.6 | 218 | 100 |

| 1893 | 158 | 36.3 | 75 | 17.2 | 435 | 100 |

| 1900 | 207 | 32.0 | 120 | 18.5 | 648 | 100 |

| 1904/1905 | 246 | 22.5 | 222 | 20.3 | 1093 | 100 |

| 1910/1911 | 282 | 25.7 | 214 | 19.5 | 1097 | 100 |

| 1913 | 306 | 24.5 | 242 | 19.4 | 1247 | 100 |

Source: Pytlas, 1991, p. 57.

In 1897, more than one in four people employed in industry and crafts in Łódź were of German nationality. There was an even higher proportion of people of German origin among those living on income from capital and related sources, and a slightly lower proportion among those living on state funds (Janczak, 1982, pp. 159, 163-166). According to the 1897 census, 73% of the population of German origin in Łódź made their living from industrial and craft occupations, 8% from trade, and 10% from serving others and other professions (Janczak, 1997, p. 66; Janczak, 1991, p. 50). The employment of representatives of the German minority in clerical and administrative positions was relatively low, compared to other large cities in the Kingdom, due to the weakness of the administrative and cultural functions of this eminently industrial city. Compared to other national groups, German population was relatively the best educated – in Łódź, the literacy rate in this ethnic group in 1897 exceeded 59% and was much higher than the average 50.5% for the entire population of the city’s inhabitants.[29]

The beginning of the 20th century, with the deterioration of working conditions, brought the emergence of economic tensions. Strikes began to break out in numerous factories in the Russian partition in 1905. The unrest also extended to Łódź, where strong social tensions had clear national connotations. Of great importance was the fact that the economically strongest nationality group was the Germans, involved in industrial activities. In 1913, 27 joint-stock companies (only one Polish), ninety-five factories (10 Polish) and 251 trading companies (125 Polish) remained in the hands of this ethnic group in Łódź. Persons of German nationality owned 1,422 properties (while Poles held titles to 700 properties) (Karwacki, 1972, p. 9). Of the fourteen largest businesses operating in Łódź in the early 20th century, ten were German-owned (see Kessler, 2001, p. 18). Of just over 1,000 foremen and skilled technical staff in the Łódź textile industry, two-thirds were of German nationality.[30] This structure of capital and employment in Łódź and the region was determined by the dominance of textile industry, in which newcomers from across the western border of the Kingdom of Poland had been involved for generations.

Among the German immigrants, there was a clear tendency towards separation in the sphere of professional and social activities, which was manifested, among other things, in the reluctance to join existing Polish-Catholic associations and craft guilds. Where settlers formed sufficiently strong concentrations, as in Łódź, they established their own German organisations.[31] This led to the formation of a kind of professional ghetto, to some extent isolated from Polish society and characterised by cultural, linguistic and religious distinctiveness.

A gradually developing school system for the children of German settlers helped to maintain a sense of national identity. A network of Protestant religious schools with German as the language of instruction was developing, often without Polish as part of their curriculum.[32] The assimilation processes were counteracted by the religious separateness of the dominant part of the German settlers belonging to the Evangelical Church of the Augsburg Confession.

During the pioneer period, which lasted until the end of the third decade of the 19th century, assimilation processes occurred to a limited extent – especially where the German minority formed larger clusters – and affected a small number of people. Rather, these were times of adaptation of the German community to the new, and rapidly changing, living conditions in their new place of settlement (Pytlas, 1996, p. 14). Over time, the process of social integration has gradually become more pronounced in successive generations of migrants, with a growing sense of rootedness in the new place of settlement in part of the German population. The assimilation of the German population, which slowly progressed during the inter-uprising period, also in Łódź, clearly slowed down in the mid-1860s.

Growing unemployment among workers and the increasing emigration of the Polish population to Western European countries to find jobs contributed to the emergence of certain national tensions in the 1870s and 1880s also in the industrial centres. In Łódź, antagonism gradually grew between some of the German factory owners, who, with the permission of the imperial authorities, employed workers imported from Germany, and the impoverished Polish population.

The polarisation of national attitudes was reflected in the fact that people of German nationality were favoured in the selection of personnel for the more attractive factory positions.[33] On the other hand, Polish employees were ill-disposed even to situations where the filling of a position by a person of German nationality was entirely justified by professional qualification needs. The increasing influx of immigrants into Łódź industry in the late 1870s and early 1880s clearly weakened the ongoing assimilation processes of the German minority. The newcomers, unlike the earlier settlers, were not inclined to learn Polish, nor did they feel the need to integrate with the Polish community.[34] Barriers of a socio-economic nature as well as differences resulting from religious beliefs were factors slowing down the process of Polonisation (Falęcki, 1996, p. 78).

With its population dominated by immigrants, without any significant cultural traditions or historical heritage that could have fostered the integration and assimilation of newcomers from abroad, Łódź was quite unique in terms of the ongoing integration and assimilation processes of the German minority. Initially, the predominance of recently settled people of German nationality in the city, together with the lack of Polish intelligentsia, encouraged people to close themselves within their own ethnic circle. It was not until the last forty years of the 19th century that the percentage of German inhabitants in the rapidly expanding Lodz decreased significantly. However, the multinational character of the city with a growing number of inhabitants of Polish nationality only accelerated the Polonisation processes to a certain extent, as the Łódź bourgeoisie, largely of German nationality, showed weak ties with Polish culture, and the city itself remained on the margins of Polish culture until the outbreak of World War I, which did not create a climate conducive to assimilation processes (cf. Nietyksza, 1986, pp. 306–308).

In a situation where the German community was dominant, the attraction of the culture, language and customs of this ethnic group for large sections of the population of other nationalities grew. The activity of bourgeoisie of German nationality in the cultural field was crucial. As early as the 1850s, amateur theatre groups were active.[35] The preservation of the language and culture of their country of origin was helped by the activities of numerous German singing associations.[36] In 1906, the Association of German-speaking Foremen and Workers was founded in Łódź, followed in 1907 by Łódź School and Educational Society (Radziszewska and Woźniak, 2000, pp. 46–70). From the point of view of the preservation of German culture and language, important support came from the press, whose first German-language titles appeared in Central Poland in the last decades of the 19th century.[37]

These measures aimed at preserving the language and native culture of the German minority, while undoubtedly delaying, could not stop the processes of assimilation and Polonisation, which were becoming increasingly pronounced over time, especially among earlier settlers who had managed to grow attached to their country of settlement.

Among the multi-ethnic community of Łódź, ethnic diversity and a sense of nationality were generally not a source of major dilemmas. All were citizens of the Russian Empire for whom Russian was the official language (from 1865 onwards) and, regardless of their origins and the language they used at home, they had a fairly limited sense of connection with their own national culture, feeling themselves to be primarily members of local communities. The German population did not so much feel a connection to an ideological homeland, but above all identified with the environment of their place of residence, settlement, town or region. For the most part, these were people who could hardly be considered assimilated, but who, while not completely renouncing their national identity, at the same time tried to be loyal to Polish society.

At the end of the nineteenth century quite a numerous group of non-Polonised people of German nationality emerged, mainly from the metropolitan business community, with a loyalist attitude to every authority. For this group, a sense of nationality was of secondary importance, and the key issue was the possibility of doing business.[38]

This phenomenon at the beginning of the 20th century was particularly evident in Łódź which

despite being neither a country nor a state, has its own nationality – these are called ‘Lodzermenschen’ in German. Their original homeland was Germany; their prolonged residence in our country for several generations eventually transformed their Germanic patriotism but did not attract them to Polish nationality. These people are mostly politically unprincipled – they have found their homeland in Łódź, here they have earned their living and their positions, they have become attached to the city ... among many of these ‘people of Łódź’ a turn towards assimilation with us can be observed, and the children of ‘Lodzermenschen’ sometimes openly call themselves Poles already (Górski, 1904, pp. 21–24).

At the turn of the 19th century, the German community settled in Łódź was truly diverse in terms of its sense of nationality. In addition to a certain part of it, especially older immigrants in the following generations, who had already been Polonised, there was also no shortage of people declaring their German nationality (and among them also germanised Poles and germanised Jews) as well as those undecided about their nationality (Górski, 1904, p. 22, 24). And although it is difficult to speak of advanced processes of Polonisation among the entire ethnic German community, most of them were well integrated into the social environment of the city.

The German settlers arriving in Łódź in the 19th century made an unquestionable and very significant contribution to the development of the city. The influx of professional labor force of German origin determined the development of the textile industry in Łódź. The settlers coming from abroad were characterised by the typical Protestant diligence and thriftiness, sense of responsibility and respect for work. The tendency to invest at the expense of limiting current consumption facilitated adaptation to a new place of residence and was particularly important in the period of accelerated industrialisation. Over the course of several 19th-century decades, Łódź grew from a small, neglected settlement into the main urban centre of Central Poland and the largest concentration of textile production on Polish territory.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Germans involved in industrial activities were the economically strongest national group in Łódź. Most of the joint-stock companies, factories, trading companies and real estate remained in the hands of this ethnic group. The German-speaking population constituted the majority of qualified technical personnel in the textile industry of Łódź.

When Poland regained independence in 1918, the role of the German minority in the city’s demographic and economic potential was somewhat limited. The population of German origin in the interwar period, numbering about 50,000−60,000 people (about 10% of the city’s population), still had a significant influence on the development of Łódź, and most of the owners of large production plants had German roots. There was a strong concentration of this national group south of the Łódka River (where industrial settlement had already begun in the first half of the 19th century), especially in the southern part of the city center.

The Second World War brought radical transformations in the national structure of the inhabitants of Łódź, once a city where three nationalities (Polish, German, and Jewish) lived side by side for a century and a half, resulted in. The extermination of the Jewish population and the escape and displacement of the German population resulted in the city becoming mono-national. The second half of the 20th century – a period of communist rule in Poland and the related historical policy − was not conducive to maintaining the multinational heritage of Łódź.

The situation changed significantly after 1990, with the democratisation of life in the country and local governments independence. The past three decades have seen attempts at restoring the memory of the achievements of German settlers and their role in the development of Łódź. This role is documented by the heritage left behind, visible in the contemporary structure of urban space − Evangelical cemeteries, factory buildings, factory owners’ palaces, and buildings of German financial and educational institutions. The contribution of the German minority to the development of the city, which was repressed from social consciousness in the first post-war period, is now being recalled again, which can be seen, for example, in the concern for the relics of the post-German cultural heritage, or in the sphere of toponymy − many streets and objects of the rapidly revitalising city space recall the memory of its distinguished citizens of German origin. Łódź, today devoid of German and Jewish inhabitants, due to its heritage still remains a multicultural city.

BAJER, K. (1958), Przemysł włókienniczy na ziemiach polskich od początku XIX wieku do 1939 roku. Zarys historyczno-ekonomiczny, Łódź.

BARANOWSKI, B. and FIJAŁEK, J. (eds) (1980), Łódź. Dzieje miasta, Warsaw–Łódź.

BUDZIAREK, M. (2001), ‘Katolicy niemieccy w Łodzi (wybrane zagadnienia)’ [in:] KUCZYŃSKI, K. A. and RATECKA, B. (eds), Niemcy w dziejach Łodzi do 1945 r., Łódź, pp. 41−76.

EICHLER, A. (1921), Das Deutschtum in Kongresppolen, Stuttgart.

FALĘCKI, T. (1996), ‘Niemcy w Łodzi i Niemcy w województwie śląskim w okresie międzywojennym. Wzajemne powiązania oraz podobieństwa i różnice pod względem społeczno-ekonomicznym i świadomościowym’ [in:] WILK, M. (ed.), Niemcy w Łodzi do 1939 r., Łódź, pp. 74−88.

FLATT, O. (1853), Opis miasta Łodzi pod względem historycznym, statystycznym i przemysłowym, Warsaw.

FRIEDMAN, F. (1933), ‘Początki przemysłu w Łodzi 1823–1830’, Rocznik Łódzki, 3, pp. 97−186.

GĄSIOROWSKA, N. (1965), ‘Osadnictwo fabryczne’, Ekonomista, 22 (1–2), [in:] GĄSIOROWSKA-GRABOWSKA, N., ‘Z dziejów przemysłu w Królestwie Polskim’, Warszawa, pp. 70–135.

GINSBERT, A. (1962), Łodź. Studium monograficzne, Łodź.

GÓRSKI, S. (1904), Łódź współczesna: obrazki i szkice publicystyczne, Łódź.

Informator Miasta Łodzi na 1919 r., Łódź 1918.

JANCZAK, J. (1982), Ludność Łodzi przemysłowej 1840–1914, Łódź.

JANCZAK, J. (1991), ‘Struktura narodowościowa w Łodzi w latach 1820–1939’ [in:] PUŚ, W. and LISZEWSKI, S. (eds), Dzieje Żydów w Łodzi w latach 1820–1944, Łódź, pp. 42−54.

JANCZAK, J. (1997), ‘Struktura społeczna ludności Łodzi w latach 1820–1918’ [in:] SAMUŚ, P. (ed.) Polacy – Niemcy – Żydzi w Łodzi. Sąsiedzi dalecy i bliscy, Łódź, pp. 40−69.

JANOWICZ, L. (1907), Zarys rozwoju przemysłu w Królestwie Polskim, Warsaw.

JAWORSKA, J. (1988), ‘Prasa’ [in:] ROSIN, R. (ed.), Łódź. Dzieje miasta, 1, Warsaw-Łódź, pp. 546−555.

HEIKE, O. (1979), 150 Jahre Schwabensiedlungen in Polen 1795–1945, Leverkusen.

KARWACKI, W. L. (1972), Związki zawodowe i stowarzyszenia pracodawców w Łodzi (do 1914 roku), Łódź.

KESSLER, W. (2001), ‘Rola Niemców w Łodzi’ [in:] KUCZYŃSKI, K. A. and RATECKA, B. (eds), Niemcy w dziejach Łodzi do 1945 r., Łódź, pp. 11−30.

KOSSMANN, E. O. (1936), ‘Das alte deutsche Lodz auf Grund der städtischen Seelenbücher’, Deutsche Wissenschaftliche Zeitschrift für Polen, Hf. XXX.

KOSSMANN, O. (1966), Lodz: eine historisch-geographische Analyse, Würzburg.

KOSSMANN, O. (1985), Deutsche mitten in Polen, Unsere Vorfahren am Webstuhl der Geschichte, Berlin/Bonn.

KOSZUTSKI, S. (1905), Rozwój ekonomiczny Królestwa Polskiego w ostatnim trzydziestoleciu 1870–1900, Warsaw.

KOTER, M. (1969), ‘Geneza układu przestrzennego Łodzi przemysłowej’, Prace Geograficzne, 79, Warsaw.

KOTER, M., LISZEWSKI, S., MARSZAŁ, T. and PĄCZKA, S. (1993), ‘Man, Environment and Planning in the Development of Lodz Urban Region’ [in:] MARSZAŁ, T. and MICHALSKI, W. (eds), ‘Planning and Environment in the Lodz Region’, Kronika Miasta Łodzi, 1, pp. 9−34.

KOTER, M., KULESZA, M., PUŚ, W. and PYTLAS, S. (2005), Wpływ wielonarodowego dziedzictwa kulturowego Łodzi na współczesne oblicze miasta, Łódź.

KUCNER, M. (2001), ‘Prasa niemiecka w Łodzi 1863–1939’ [in:] KUCZYŃSKI, K. A. and RATECKA, B. (eds), Niemcy w dziejach Łodzi do 1945 r., Łódź, pp. 209−234.

KULIGOWSKA-KORZENIEWSKA, A. (1997), ‘Łódź teatralna polska, niemiecka i żydowska. Współpraca i rywalizacja’ [in:] SAMUŚ, P. (ed.) Polacy, Niemcy, Żydzi w Łodzi w XIX-XX w.; sąsiedzi dalecy i bliscy, Łódź, pp. 240−259.

LÜCK, K. (1934), Deutsche Aufbaukräfte in der Entwicklung Polens, Plauen.

MARSZAŁ, T. (2020), Mniejszość niemiecka w Polsce Środkowej. Geneza, rozmieszczenie i struktura od końca XVIII w. do II wojny światowej, Łódź. https://doi.org/10.18778/8142-751-7

MARSZAŁ, T. (2022), ‘German immigrants in Central Poland in the late 18th and early 19th centuries’, European Spatial Research and Policy, 20 (1), pp. 25−51. https://doi.org/10.18778/1231-1952.29.1.02

MARSZAŁ, T. (2023), ‘Social integration and assimilation processes of the German minority in Central Poland in the XIX century’ [in:] RYKAŁA, A. (ed.) W kręgu geografii politycznej i dyscyplin okolicznych, Łódź pp. 323−342. https://doi.org/10.18778/8331-035-0.12

MISSALOWA, G. (1964), Studia nad powstaniem łódzkiego okręgu przemysłowego (1815–1870), I ‘Przemysł’, Łódź.

MISSALOWA, G. (1967), Studia nad powstaniem łódzkiego okręgu przemysłowego (1815–1870), II ‘Klasa robotnicza’, Łódź.

MISSALOWA, G. (ed.) (1957), Materiały do historii miast, przemysłu i klasy robotniczej w okręgu łódzkim, I ‘Źródła do historii klasy robotniczej okręgu łódzkiego’, Warsaw.

Pierwaja wsieobszczaja pierepis nasielenija Rossijskoj Imperii 1897, Obszczyj zwod, l, Petersburg 1905.

PODGÓRSKA, E. (1988), ‘Szkolnictwo’ [in:] ROSIN, R. (ed.), Łódź. Dzieje miasta, 1, Warsaw–Łódź, pp. 508−526.

PUŚ, W. (1987), Dzieje Łodzi przemysłowej (zarys historii), Łodź.

PYTLAS, S. (1991), ‘Skład narodowościowy przemysłowców łódzkich do 1914 r.’ [in:] PUŚ, W. and LISZEWSKI, S. (eds), Dzieje Żydów w Łodzi w latach 1820–1944. Wybrane problemy, Łódź, pp. 55−78.

PYTLAS, S. (1996), ‘Problemy asymilacji i polonizacji społeczności niemieckiej w Łodzi do 1914 r.’ [in:] WILK, M. (ed.), Niemcy w Łodzi do 1939 r., Łódź, pp. 13−20.

PYTLAS, S. (2006), ‘Sylwetki łódzkich przemysłowców niemieckich w XIX i na początku XX w.’ [in:] PYTLAS, S. and KITA, J. (eds), Historia – społeczeństwo – gospodarka, Łódź, pp. 148–156.

RADZISZEWSKA, K. and WOŹNIAK, K. (eds) (2000), Pod jednym dachem. Niemcy oraz ich polscy i żydowscy sąsiedzi w Łodzi w XIX i XX wieku, Łódź.

ROSSET, E. (1928), ‘Łódź w latach ١٨٦٠–١٨٧٠. Zarys historyczno-statystyczny’, Rocznik Łódzki, I, pp. 335–378.

RYNKOWSKA, A. (1951), Działalność gospodarcza władz Królestwa Polskiego na terenie Łodzi przemysłowej w latach 1821–1831, Łódź.

RYNKOWSKA, A. (ed.) (1960), ‘Początki rozwoju kapitalistycznego miasta Łodzi (1820−1864). Źródła’, Materiały do historii miast, przemysłu i klasy robotniczej w okręgu łódzkim, IV, Warsaw.

SCHMIT, M. (1942), Mundart und Siedlungsgeschichte der schwäbisch-rheinfränkischen Dörfer bei Litzmannstadt, Marburg.

STASZEWSKI, J. (1931), ‘Początki przemysłu lnianego w Łodzi’, Rocznik Łódzki, 2 , pp. 261–277.

SZTOBRYN, D. (1999), Działalność kulturalno-oświatowa diaspory niemieckiej w Łodzi do 1939 r., Łódź.

ŚMIAŁOWSKI, J. (1999), ‘Niemców polskich dylematy wyborów’ [in:] CABAN, W. (ed.), Niemieccy osadnicy w Królestwie Polskim 1815–1915, Kielce, pp. 209–224.

WĄSICKI, J. (1953), ‘Kolonizacja niemiecka w okresie Prus Południowych 1793–1806’, Przegląd Zachodni, Y. 8, (9/10), pp. 137–179.

WOŹNIAK, P. K. (2015), ‘Pruskie wsie liniowe w okolicach Łodzi i ich mieszkańcy w początkach XIX w.’, Acta Universitatis Lodziensis. Folia Geographica Socio-Oeconomica, 21, pp. 106–108.