Volume 30, 2023, Number 2

https://doi.org/10.18778/1231-1952.30.2.07

Abstract. Learning city networks are real-time laboratories related to national and local urban development policies. In order to support learning city networks, the Federal Institute for Research on Building, Urban Affairs and Spatial Development (BBSR) together with the Federal Ministry of Housing, Urban Development and Building (BMWSB), the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the German Marshall Fund of the United States (GMF), the Deutsche Gesellschaft für internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), and partner cities have developed and further enhanced the multi-level D4UC (Dialogues for Urban Change) Method since 2012. This method makes an international exchange on the specificities of urban transformation processes, based on purposeful projects, possible for participating cities. The article discusses methods and lessons learned and is framed within a theoretical background of learning networks.

Key words: urban laboratories, multi-level governance, D4UC method.

Ministers responsible for urban development of the Group of Seven (G7) met for their first G7 Summit on Urban Development in Germany in 2022 and agreed upon joining forces in order to make cities more liveable (G7 Germany, 2022). They highlighted the importance of coordinated multilateral cooperation in order to overcome global challenges (G7 Germany, 2022a:2). Germany’s Federal Chancellor Olaf Scholz stated that especially in cities ideas, concepts and solutions could grow (G7 Germany, 2022b). The Ministers’ communique highlighted the interconnection of cities on the global, national and regional level. City networks, according to the communique, “are becoming major global players” (G7 Germany, 2022a, p. 3). By building up and further developing multi-level and multiple-stakeholder cooperation, as well as sharing information at intra, inter and supra-national levels, cities play a central role for sustainability (G7 Germany, 2022a, pp. 4–5). This role can be strengthened by increasingly involving cities in the development and implementation of urban development policies and the dialogue between local and national levels (G7 Germany, 2022a, pp. 7–8), as cities remain crucial local arenas for decision-making (cf., Barber, 2013; WBGU, 2016).

The question of governance and actors willing to learn may play a major role in this context. The introduction of this context completes the topic in the same way as a conclusion is drawn focusing on which forms of learning networks are necessary in order to address all or some of the multi levels.

This decentralised power role of cities has been emphasised by a couple of agreements, particularly on the global level, e.g., the New Urban Agenda of the United Nations (United Nations, 2017) and the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (United Nations, 2015), or in a more informal setting by the Memorandum of Understanding on Urban Energies (Mueller, 2013).

Apart from the data-oriented and thus quantitative view on the multi-level analysis of urban development, taken by this special issue, this article focuses on a qualitative look at multi-level city learning networks and their impact on urban transformation processes. International cooperation on the future of cities and urban development policies seems to be more important than ever, as global challenges increase and influence cities in a direct way. The aforementioned agreement of the G7 Ministers clearly underlined this necessity and the importance of multi-level cooperation. Not only with the G7 Agreement of 2022 but in general it pursues the German Federal Government actively the international cooperation on urban development and housing. Accelerating urbanisation, as retraced by the United Nations while applying remote sensing data (UN DESA 2018), and still ongoing globalisation trends are seen as a chance to fostering an international dialogue on urban development, for example in the framework of urbanisation partnerships.

Germany’s international activities on urbanisation in a sustainable manner consist of five aspects (Deutscher Bundestag, 2015): (1) good governance and administration, (2) human rights and social engagement/ participation, (3) sustainable economy, (4) environmental protection, natural resources and climate, and (5) education, research, and culture. Considering the first aspect in this series, the Federal Government facilitates an international discourse on sustainable urban development and best practices at the national, regional, and local levels, i.e., in the sense of a multi-level approach. The German National Urban Development Policy, a joint initiative of the federal, state and local government(s), as well as their representative bodies, is one example of the implementation of this multi-level cooperation on urban development (BMWSB/ BBSR, 2023). It includes the D4UC international city learning network as the focus of this article. As global challenges and the so-called “wicked problems” (Weber and Khademian, 2008) increase, the need for a systematic international exchange becomes ever more urgent. As research on learning city networks within the field of urban development only exists in fragments, this article exclusively analyses the D4UC multi-level governance learning city network. Measurable indicators on the multi dimensions of urban development, as described in this special issue, are of outstanding value for urban development and related transformation processes. Successfully implementing changes, which are based on quantitative approaches, governance and learning processes constitute the second important aspect. This article thus aims at enlarging the primarily data-oriented view of this special issue by the qualitative aspect of multi-level governance and learning networks.

City networks, twinning partnerships, and exchange programmes have been for many years an essential part of international cooperation on urban development. Learning city networks on urban development including multi-level (national, regional and/or local) governance actors, in contrast, are relatively rare.

Learning networks in general “are a form of collaboration that enables groups of stakeholders to cultivate connections across communities and organizations and to strengthen a whole system simply by focusing on the potential for participants to share information and learn from one another” (Ehrlichman and Sawyer, 2018). New collaborative actions are not the primary goal of a learning network. The focus is rather on deeper connections and shared learning with the aim of building a robust network that can lead to a concrete strategy for change (ibidem).

Based on their experience with several networks over a few years, Ehrlichman and Sawyer (2018) defined four characteristics of learning networks:

Collecting information from the field and from participants, defining a clear process structure and work target, and providing a technical infrastructure to facilitate and share information within the network are the central tasks of a learning network. This includes listening and learning to and from the network (information in). Bringing information from outside the network into it is the second important issue (information out). Examples include newsletters, webinars, calls, and meetings. Yet, a learning network goes further than just collecting information. It aims at directly connecting stakeholders, independently from a central coordination and based on a self-organisation, as well as a support of members to coordinate activities on their own (information across) (Ehrlichman and Sawyer, 2018).

Learning from each other is the central aspect of a learning network. Simons and Ruijters (2004, p. 4) referred to learning as “implicit or explicit mental and / or overt activities and processes leading to changes in knowledge, skills or attitudes or the ability to learn of individuals, groups, or organizations. These can under certain conditions also lead to changes in work processes or work outcomes of individuals, groups, or organizations.” Implicit learning or “hands-on learning” (van den Dool and Schaap, 2020, p. 16) can also be seen as least or even more important than formal learning processes in training classes. Hambleton (2020, p. 32) has advocated for a focus on “relevant practices” instead of “best practices” in a city dialogue. A relevant practice, from his perspective, includes insights and approaches that can help cities look for specific objectives. This is especially important in a rapidly changing world that requires public innovation. Best practices already exist and are not necessarily an essential innovation (Hambleton, 2020, p. 33).

Learning in governance networks includes its own challenges, as problems have become more and more complex in the same way as finding solutions for the challenges requires communication and interaction with a diverse group of stakeholders. Handling these “wicked problems” on a governance level is complex, as national, state, and local authorities act in a relatively institutional framework (Weber and Khademian, 2008, p. 334; Riche et al., 2020, p. 148; Schaap and van den Dool, 2020a, p. 1). Global trends like climate change, migration or social polarisation affect cities often in an intense manner. Therefore, city leaders and administrations in particular have to find answers to these challenges. Many examples show that they are successful in finding these answers. Sharing successful stories and learning from each other is key to the future of cities.

A first step in a city learning network may thus be to clearly define the given problem (Schaap and van den Dool, 2020a, p. 4). Finding solutions for often diffuse and abstract urban development problems requires different methods than a specific problem, but provides more room for consideration and reflection (van den Dool and Schaap, 2020, p. 25). Weber and Khademian (2008, p. 337) have identified three dimensions of “wicked problems”: they are either/or unstructured, crosscutting and relentless. Handling these challenges requires broad knowledge to develop a new knowledge base and enable cooperation. Transferring, receiving, and integrating knowledge are seen as continuous central issues as “wicked problems,” modified in different dimensions.

Learning in a network includes individual and collective learning elements. The diversity of conditions affects these learning processes. Positive perceptions can foster individual learning within a network, whereas negative perceptions support individual learning from outside a network. In order to foster individual and collective learning, network leaders or moderators, who facilitate the sharing of information and the handling of different opinions, are crucial (Riche et al., 2020, p. 155). Learning in a governance network is more successful when informal rules enable creativity and consensus while formal rules provide guidance for imbalances and information exchange (ibidem, p. 158). Including different participants in governance networks and building trust between these stakeholders are other central elements of an effective network (ibidem, p. 147). As more and more “wicked problems” require the involvement of private and societal actors, a “hybrid” governance network of private and public participants would constitute another network type (Schaap and van den Dool, 2020, p. 2). Governments, businesses and citizens depend on each other and have thus to interact with each other (van den Dool and Schaap, 2020, p. 17).

Learning city networks “profit from the countervailing principle of governance and management, i.e., higher levels of governance respect lower levels of governance in the same way as lower levels of governance in return orient their work towards higher levels of governance and the pro-active participation of all relevant stakeholders” (Mueller, 2016, p. 3).

In order to support learning city networks, the Federal Ministry for Housing, Urban Development and Building (BMWSB), the Federal Institute for Research on Building, Urban Affairs and Spatial Development (BBSR), the Deutsche Gesellschaft für internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), all in Germany, as well as the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the German Marshall Fund of the United States (GMF) and partner cities have developed D4UC since 2012. D4UC is part of the German National Urban Development Policy (BMWSB/ BBSR, 2023) and aims at an international exchange to promote public welfare-oriented and integrated urban development. The multiple partners advocate for the (further) development and implementation of national urban development policies and promote innovation (GMF, 2015, 2019; Mueller, 2016). An important guideline and framework of Germany’s National Urban Development Policy is the New Leipzig Charter, which was adopted in 2020 by the European Ministers on Urban Matters. It also highlights the importance of multi-level governance: “As recommended by the Pact of Amsterdam and the New Urban Agenda, vertical and horizontal multi-level and multi-stakeholder cooperation, both bottom-up and top-down, is key to good governance” (BBSR, 2020, p. 38).

The D4UC “basically refers to the necessity of managing urban development and urban planning in a continuous dialogue of all those stakeholders and actors who carry out planning decisions and thus strive for an optimal shape of urban transformation processes” (Mueller, 2016, p. 4). This concept has been adopted in three different countries: the U.S., South Africa, and the Ukraine. This article focuses on the transatlantic part of the dialogue, based on a systematic literature review of the network’s observations published by GMF (2015, 2019) and Mueller (2016).

The dialogue is based on a joint declaration of intent in the field of urban development and housing signed by HUD and the German Ministry for Urban Development, as well as respective predecessor institutions and explicitly requesting multi-level exchange formats. The first declaration was signed in 2011, and an the agreement was amended in 2019. Ten cities on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean have participated in the network so far, six cities joined in late 2022.

Fostering integrated and sustainable urban development by including different stakeholders on different government levels is set as an important goal on both sides of the Atlantic. While policies and instruments vary between both nations (see Table 1), frameworks at the national and supranational level in Germany and the U.S. draw upon comparable political aims for urban development. The European New Leipzig Charter – the currently relevant political agreement in Europe − “aims to bolster integrated urban development for the common good, in the interest of preserving and improving quality of life in all of Europe’s cities and communities” (BMI, 2020). HUD’s six liveability principles constitute a foundation for interagency coordination on urban development in the USA (HUD, 2023b).

Table 1. National urban policies in Germany and the USA

| Variable | Germany | USA |

|---|---|---|

| Name of national urban policy | National Urban Development Policy – a joint initiative of the federal, state and local governments | No national urban policy, but cross-agency and cross-sector federal initiatives and locally-driven efforts, including Choice Neighborhoods Program, Promise Zone Initiative, Sustainable Communities Initiative and other place-based efforts |

| Date of national urban policy | 2007 | 2009 |

| Legal status | Administrative guidance/ framework document | Not applicable |

| How developed (e.g., through a participatory/ stakeholder process, or act of parliament) | Stakeholder participation, resolution of parliament, resolution of standing conference of ministers responsible for urban development | Legislative enactment with stakeholder engagement and locally-driven implementation |

| Type of national urban agency | General urban development authority | Not applicable |

| Implementation mechanism (e.g., committee, involvement of multiple agencies, national-local coordination) | National Urban Development Board | Involvement of multiple agencies, national-local coordination |

Source: OECD, 2017, p. 61 et seqq. and 133 et seqq.; HUD, 2023b.

The central characteristic of the D4UC transatlantic learning city network is an ongoing dialogue between local practitioners, the federal government and other ‘city makers’ in Germany and in the U.S. on the current topics of urban development. Mueller (2016, p. 4; see also GMF, 2015, 2019) has described three modules of the so-called D4UC method: (1) a real-time learning laboratory (project-based work), (2) a guided and spontaneous exchange of experiences (regular workshops), and (3) a zooming of the findings.

The uniqueness of the D4UC is based on:

Its multi-level approach, integrating local, regional, national, and subnational stakeholders, is special. The results of the network are transferred to all different levels and thus allow the influence of national policies related to urban development. Hands-on and pragmatic instruments, tools and processes are in the centre of the network discussions. Participants are active members and take responsibilities for topics and methods applied in the network sessions, as well as transferring lessons learned into actions (ownership) (GMF, 2015, 2019; Mueller, 2016).

The multi-level approach includes stakeholders from the local and the national level, as well as international organisations. Each network cohort usually includes three cities from the U.S. and three cities from Germany, with two to four participants on each side (see Table 2). These participants rely on a background in city administration, policy or civil society. If possible, participants should join the full network cohort. Apart from different institutions, participants bring different professional backgrounds to the network. This ensures a learning network that includes multiple professions and institutions, as well as multiple views on the complexity of urban development issues. Selection criteria for participating cities are existing pilot projects within the specific network focus theme. The national ministries of both countries define the overall themes. Furthermore, openness to new tools, experiments, processes, a critical reflection on one’s own work and processes, a curiosity for innovation, and a willingness to share own experiences with others are crucial in the same way as readiness to cooperate (GMF, 2015, 2019; Mueller, 2016).

Table 2. Overview of the transatlantic D4UC city networks

| Network cohort | I: 2011–2013 | II: 2013–2015 | III: 2016–2018 | IV: 2022–2023/2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network cities from Germany | Bottrop, Leipzig, Ludwigsburg | Bottrop, Leipzig, Ludwigsburg | Bottrop, Karlsruhe, Leipzig | Berlin, Frankfurt, Munich |

| Network cities from the USA | Austin, Flint, Memphis | Austin, Flint, Memphis | Baltimore, Charlotte, Pittsburgh | Atlanta, Seattle, St. Louis |

| Focus themes | Participation and engagement | Civic engagement and active planning processes | Integrated urban development | Breaking barriers to housing for all |

Source: GMF, 2015, 2019; Mueller, 2016.

Learning Laboratories (Labs), especially Urban Living Labs, are an essential setting (cf. Nesti, 2018), particularly in a real-time mode (cf. WBGU, 2016). These labs focus on project-based work and include real projects, for which the participating cities are currently responsible. This approach includes a moderated and well-organised as well as a spontaneous exchange and dialogue between the participating stakeholders and actors (information in and information out). In each cohort, site-visits in the U.S. and in Germany are part of the network programme. Network members are able to see most of the discussed projects in reality. During these face-to-face interactions, cooperation and exchange are organised in different digital formats, e.g., video-calls or webinars. The aims of and standards for the learning network are defined at the beginning of each cohort. Success is not only measured in numbers and data but also in implementing lessons learned in participant daily work routine (GMF, 2015, 2019; Mueller, 2016).

Especially sharing best and relevant practices, as well as successful solutions, is helpful for the learning process and testing new approaches and paths in urban development. A key element of the D4UC network is a ‘peer-to-peer’ learning method. Network participants exercise the role of a ‘peer’ or a ‘coach’ and work in teams – depending on the city structure and adequate projects, as well as the current challenges in urban development. In many ways, participants drive the learning process (information across) (GMF, 2015, 2019; Mueller, 2016). They prioritise, based on their knowledge, expertise and experience, learning issues (GMF, 2019, p. 8). Teamwork is later integrated into the full network in order to find common solutions, which are thought-provoking and stimulating for the cities (GMF, 2019, p. 22). These solutions can emerge independently of local specific contexts and are neutral and open for a broader transferability to others. The discussion includes repressive and promotive aspects. Experts in a specific theme, e.g., on creating a culture of participation or applying innovative media in civic engagement, provided external input in the second cohort (GMF, 2015, p. 12–13).

The multi-level approach is addressed in local-national sessions. National actors are able to learn about concerns and challenges on the local level. Due to the dialogue, local participants were able to intensify their contacts with their respective national government. Before the network started its work, 41% of the participants had little or no contact with the national level (GMF, 2019, p. 24).

A successful example of this peer-to-peer learning method is a project of the participating City of Pittsburgh. The city applied the ideas commonly created in the workshop to develop a pilot project that won a nomination for an award – the Champion Cities by Bloomberg Philanthropies – and subsequently received funding for implementation. The innovative idea was to enhance the demand for retrofitting housing by reducing costs through a group purchase of material and support of DIY product installation (GMF, 2019, p. 22). Another example was the City of Charlotte where – in the sense of the focus theme of integrated urban development – subsidised housing was geographically placed in areas of social and economic potentials in order to stimulate in the long run social mobility and a respective social upscaling (Chetty et al., 2022). These are two specific projects, addressing “wicked problems” of and for the network cities.

The first three network cohorts showed many similarities in urban development on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean – despite cultural and regulatory differences. A central element of the network is the common work on one main issue or question, which is of significance for the network cities and their daily work routines. Engaged individuals are often also important for the success of the network. So far, cities of different sizes have participated in three network cohorts, though size has not been a factor for success in the networks. The openness to and willingness for a trustful exchange and the sharing of information among each other has been the more important factor. An exchange on thematic basis seems more helpful than novelties and best practices. This includes applying instruments and concrete solutions in the respectively local administrative practice (GMF, 2015, 2019; Mueller, 2016).

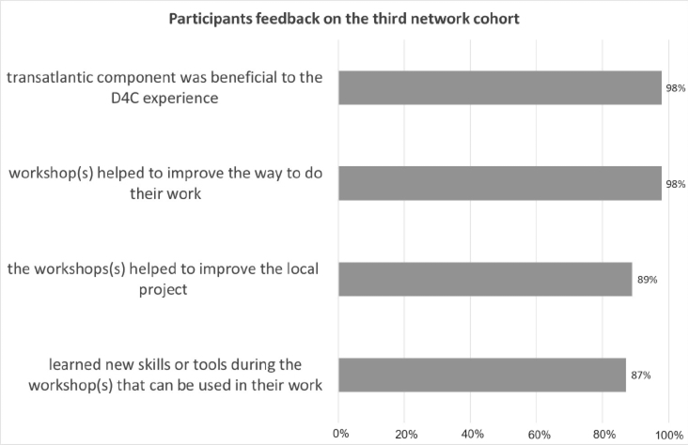

Participants of the third cohort gave feedback on their network experiences (see Fig. 1). A majority described the network experience as important for their own work. It helped to improve the way in which they carried out their work and thus enhanced the respective local project (GMF, 2019:8).

Based on the experiences so far, it could be possible to enhance the D4UC method in certain aspects. One modification scheme has already started in the fourth and current cohort. The network will be guided by two research teams supporting the network with in-depth research on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. The support in Germany includes an in-depth research on density and mixed-used development approaches (BBSR, 2023). Interviews with participating cities were undertaken as the first step to learn more about the specific challenges in the cities, as well as expectations and wishes for the network cohort (information in). The research teams[1] also bring new and external knowledge into the network (information out). Enlarging the city network has already grown by the inclusion of thematic experts on a case-to-case-basis, but it could also be intensified. Most of the dialogue occurs during the organised workshops on site or digitally. Deepening the relations among the network members in between those workshops could also help to strengthen processes and partnerships (GMF, 2015, 2019; Mueller, 2016).

Fig. 1. Participants’ feedback on the third network cohort 2016–2018

Source: own work based on GMF, 2019, p. 8.

A possible modification on the national level could be to foster exchange and dialogue between cities and multiple planning levels (local, regional, national, and supranational) on specific themes. Furthermore, giving best and relevant practices more attention via awards and promoting network results via conferences, publications and the use of social media, is another option in order to strengthen the network. Respective pilot projects and incentives could also be an alternative (GMF, 2016, 2019; Mueller, 2016). Besides, the multi-level approach of these learning networks generates many beneficial insights for the national level. These could be adapted by a stronger focus on planning tools and instruments in the international context, providing policy recommendations for different stakeholders and actors at the local, regional, and national level during the network cohort (i.e., policy paper) or enhancing learning methods and transferring lessons learned to other national and international city networks, with which both nations cooperate (GMF, 2015, 2019; Mueller, 2016).

Why is it important to anchor a city network on present issues of urban development on a respective national level? An international multi-level exchange not only offers fresh ideas, new solutions and new contacts, but also enables network participants to reflect on their own work by getting a feedback and resonance or suggestions from foreign experts and counterparts. It also enables a multi-level discussion between national, regional, and local stakeholders on existing and new tools and instruments, as well as regulatory barriers and processes.

Based on the four characteristics of learning networks defined by Ehrlichman and Sawyer (2018), an information flow across the network is particularly essential. Building deeper connections and enabling co-creation between multi-level and multi-sector stakeholders is at least as important as sharing information, best and relevant practices, and lessons learned with each other.

The so-called D4UC method facilitates and supports this information flow across the network in multiple ways through:

An information flow inside a network between participants themselves and the involved organisations is as important and helpful as an information inflow from the outside from external experts and research teams. The D4UC is a governance network that also includes non-public stakeholders. It works with formal rules within an organised context, but also allows an informal exchange between network participants (van den Dool and Schapp, 2020).

What may be learned from the learning network for further processes? The transatlantic cooperation in the context of Germany’s National and International Urban Development Policy achieves important impulses (e.g., inter-city dialogue, pilot projects, transnational exchange, and awards) for continuously adapting national urban development and building laws, as well as funding programmes. Based on the work of GMF (2015, 2019) and Mueller (2016), key factors for a successful city learning network secure network continuity and stability in the same way as they build trust among the participants. This is particularly important for cross-sector teams and different governmental levels. It may be fostered by peer-to-peer learning, providing network members an ownership role within the network. Taking multi-level and multi-disciplinary approaches across sectors and scales and institutionalising them is, therefore, another key component.

The D4UC Network shows how learning can be implemented in the complex field of urban development in an international and multi-level cooperation. The peer-to-peer method seem the most important among the different learning methods , just as the ownership principle of network members in designing the network workshops is. By sharing experiences, information and knowledge in a trustful surrounding, city networks contribute valuable lessons for handling global challenges.

Different forms and formats of a city learning network may be helpful in addressing the various levels of governance. An explicit exchange between the various levels, i.e., the federal/ national and the local, may focus on regulations, instruments or funding programmes, which are applied by the local level but designed by the federal/ national level. Delving deeper into specific local challenges may help achieving a better understanding of prevailing local challenges by all levels on the one hand, while, on the other, developing possible solutions for those challenges jointly may build a stronger and more trustful cooperation structure between local actors and stakeholders, as well as between the various levels of governance.

For the increasing international activities on the federal level in Germany, for example in the context of G7, the experiences and results made in the D4UC Network are of outstanding value. The D4UC proves profoundly that an international network can help find ideas to handle the wicked problems, like affordable housing. Learning methods include information in and out from a network and, most importantly, across a multi-level network.

BARBER, B. (2013), If mayors ruled the world. Dysfunctional nations and rising cities, New Haven: Yale University Press.

BBSR – BUNDESINSTITUT FÜR BAU-, STADT- UND RAUMFORSCHUNG (2023), Density and mixed-use: Innovative approaches to redensification in German and American cities, Research Project, https://www.bbsr.bund.de/BBSR/EN/research/programs/ExWoSt/Studies/density-mixed-used/01-start.html;jsessionid=FCE688CBB91481DBBBFBB8BA2187F084.live21323 [accessed on: 17.03.2023].

BBSR – BUNDESINSTITUT FÜR BAU-, STADT- UND RAUMFORSCHUNG (2020), The New Leipzig Charter: Synthesis and focus. Empowering cities to act in pursuit of the common good, documentation of work progress and presentation of results.

BMWSB – BUNDESMINISTERIUM FÜR WOHNEN, STADTENTWICKLUNG UND BAUWESEN / BBSR – BUNDESINSTITUT FÜR BAU-, STADT- UND RAUMFORSCHUNG (2023), Dialogues for Urban Change, https://www.nationale-stadtentwicklungspolitik.de/NSPWeb/EN/Projects/D4UC/d4uc_node.html [accessed on: 17.03.2023].

BMI – BUNDESMINISTERIUM DES INNERN, FÜR BAU UND HEIMAT (2020), Germany’s Presidency of the Council of the EU: New Leipzig Charter for urban development adopted. 30. November 2020, https://www.bmi.bund.de/SharedDocs/pressemitteilungen/EN/2020/12/new-leipzig-charter.html [accessed on: 17.03.2023].

CHETTY, R., JACKSON, M. O. and KUCHLER, T. et al. (2022), ‘Social capital I: measurement and associations with economic mobility’, Nature, 608, pp. 108–121. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04996-4

DEUTSCHER BUNDESTAG (2015), ‘Leitlinien der Bundesregierung zur internationalen Zusammenarbeit für nachhaltige Urbanisierung – Partner in einer Welt der Städte’, Drucksache 18/4924 des Deutschen Bundestags.

EHLICHMAN, D. and SAWYER, D. (2018), ‘Learn Before You Leap: The Catalytic Power of a Learning Network’, Stanford Social Innovation Review. DOI: 10.48558/813x-nk18

G7 GERMANY (2022a), ‘Ministerial Meeting on Sustainable Urban Development’, Communiqué. 13 September 2022, https://www.bmwsb.bund.de/SharedDocs/downloads/Webs/BMWSB/DE/veroeffentlichungen/termine/communique-g7.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=3 [accessed on: 17.03.2023].

G7 GERMANY (2022b), Joining forces to make cities liveable, G7 Ministers’ Meeting on Urban Development, https://www.g7germany.de/g7-en/news/g7-articles/g7-urban-development-ministers-2125542 [accessed on: 17.03.2023].

GMF – GERMAN MARSHALL FUND (2019), Dialogues for Change 3.0, a U.S.-German Cities Exchange for Sustainable and Integrated Urban Development 2016–2018, https://www.gmfus.org/sites/default/files/Dialogues%20for%20Change.pdf [accessed on: 17.03.2023].

GMF – GERMAN MARSHALL FUND (2016), Civic Engagement Principles for Transatlantic Cities: Inspiration from the Dialogues for Change Initiative 2013–2015, https://www.gmfus.org/sites/default/files/D4C%25202016.pdf [accessed on: 17.03.2023].

HAMBLETON, R. (2020), ‘From «Best Practice» to «Relevant Practice» in International City-to-City Learning’, [in:] VAN DEN DOOL, L. (d.) (2020), Strategies for Urban Network Learning. International Practices and Theoretical Reflections, Palgrave Studies in Sub-National Governance, Palgrave Macmillan, Springer Nature Switzerland, pp. 31–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-36048-1_3

HUD – US DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT (2023a), HUD Policy Areas, https://www.hudexchange.info/programs/policy-areas/#community-and-economic-development [accessed on: 17.03.2023].

HUD – US DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT (2023b), Six Livability Principles, https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/economic_development/Six_Livability_Principles [accessed on: 17.03.2023].

MUELLER, A. (2016), Intercultural Impulses for Urban Development in Germany. D4C Method, BBSR-Analysen KOMPAKT 02/2016, urn:nbn:de:101:1-201610274577.

MUELLER, A. (2013), ‘Ein Kommentar zum Memorandum «Städtische Energien – Zukunftsaufgaben der Städte»’, [in:] RWTH AACHEN UNIVERSITY (ed.) (2013), Schwerpunkt Integrierte Stadtentwicklungspolitik, pnd online 1/2013, https://publications.rwth-aachen.de/record/570510/files/PND%202013%2C1.pdf [accessed on: 17.03.2023].

NESTI, G. (2018), ‘Co-production for innovation. The urban living lab experience’, Policy and Society, 37 (3), pp. 310–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2017.1374692

OECD (2017), National Urban Policy in OECD Countries, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264271906-en

RICHE, C., AUBIN, D. and MOYSON, S. (2020), ‘Too much of a good thing? A systematic review about the conditions of learning in governance networks’, European Policy Analysis, 7 (1), pp. 147–164. https://doi.org/10.1002/epa2.1080

SCHAAP, L. and VAN DEN DOO, L. (2020), ‘Introduction: Studying for urban network Learning’, [in:] VAN DEN DOOL, L. (ed.), Strategies for Urban Network Learning. International Practices and Theoretical Reflections, Palgrave Studies in Sub-National Governance, Palgrave Macmillan, Springer Nature Switzerland, pp. 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-36048-1_1

SIMONS, P. R. J. and RUIJTERS, M. (2004), ‘Learning Professionals: Towards an Integrated Model’, [in:] BOSHUIZEN, H. and BROMME, R. (eds), Professional Learning: Gaps and Transitions on the Way from Novice to Expert, pp. 207–229. https://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-2094-5_11

VAN DEN DOOL, L. and SCHAAP, L. (2020), ‘Learning Processes in an Urban Governance Context: A theoretical Exploration’, [in:] VAN DEN DOOL, L. (ed.) (2020), Strategies for Urban Network Learning. International Practices and Theoretical Reflections, Palgrave Studies in Sub-National Governance, Palgrave Macmillan, Springer Nature Switzerland, pp. 13–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-36048-1_2

WEBER, E. P. and KHADEMIAN, A. M. (2008), ‘Wicked problems, Knowledge Challenges, and Collaborative Capacity Builders in Network Settings’, [in:] Public Administration Review, March/April 2008, pp. 334–349. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2007.00866.x

WBGU – GERMAN ADVISORY COUNCIL ON GLOBAL CHANGE (2016), Humanity on the move: Unlocking the transformative power of cities, Berlin.

UN DESA – UNITED NATIONS, DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL AFFAIRS, POPULATION DIVISION (2018), World Urbanization Prospects. The 2018 Revision, https://population.un.org/wup/Publications/Files/WUP2018-Report.pdf [accessed on: 17.03.2023].

UNITED NATIONS, GENERAL ASSEMBLY (2017), New Urban Agenda, resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 23 December 2016, A/RES/71/256-EN, https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/858344?ln=es [accessed on: 17.03.2023].

UNITED NATIONS, UNITED NATIONS OFFICE FOR DISASTER RISK REDUCTION (2015), The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015-2030, https://www.undrr.org/implementing-sendai-framework/what-sendai-framework [accessed on: 17.03.2023].