Volume 30, 2023, Number 2

https://doi.org/10.18778/1231-1952.30.2.11

Abstract. The Western Region, located in the Central Region of Portugal, has a vast and rich natural and cultural heritage allowing a wide range of tourist experiences. Consequently, the aim of this study is to analyse the tourist interests and motivations that lead tourists to visit the Western Region of mainland Portugal. In 2021, 355 individuals were surveyed through a questionnaire survey, mostly living in mainland Portugal. The results reveal that the preferences of respondents for the types of tourism they most like or would like to undergo in the Western Region are Sun and Sea Tourism, Leisure Tourism, Cultural Tourism, Adventure and Nature Tourism, and Gastronomic Tourism. This study may contribute to a better understanding of the tourists’ motivations to visit the Western Region, and may be an important contribution to the tourism management entities, in order for them to enhance and/or improve their offers in this region of Portugal.

Key words: Western Region of Portugal, types of tourism, tourist offers, tourist motivations.

The tourism market evolves according to tourists’ needs and interests, also influenced by the socio-economic and political environment in which the society is. It highlights the importance of a destination tourist services and products in the growth of tourism, primarily intended to meet the needs and demands of tourists (Cunha, 2013; Jiménez and Martín, 2004; Smith, 1989). The factors influencing tourism demand are closely related to the models of consumer behaviour, such as attitudes, perceptions, images and motivations, the preponderant variables in the decision making regarding the choice to visit touristic destination (Amorim et al., 2019, 2020; Cooper et al., 2007; López-Guzmán et al., 2019; Yoo, et al., 2018).

The main objective of the present study is to analyse the motivations behind tourists visiting the Western Region of Portugal and to explore its attractions and potential for both internal and external promotion. The findings of this study will enable Destination Management Organizations (DMOs), municipalities, and other tourism-related entities to formulate strategies that create more enriching and satisfying experiences for tourists. These strategies will be informed by an understanding of the region’s potential and align with the interests and motivations of tourists.

To achieve this objective, the literature review will focus on exploring the predominant types of tourism in the western region, which include cultural tourism, leisure tourism, creative tourism, nature tourism, sun and sea tourism, and food tourism. Additionally, several models of tourism consumer behaviour will be examined to gain insights into demand patterns and the evolutionary trajectory of tourism from the perspective of the tourist consumer.

The sample of this study consisted of 355 individuals, mostly residents in mainland Portugal, and a questionnaire survey was applied in 2021. The data obtained was analysed and interpreted using the statistical software Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 26. It is intended that this study may contribute to a better understanding of the needs and motivations of tourists in the western region of Portugal and may be an added value for the communication and intervention action strategies of the tourism sector management entities of this Portuguese region.

Tourism development must consider the space and resources existing in the destinations. Also, tourism promotion should consider the territorial specificities, properly planned and structured according to the product-space perspective and articulated with the involvement of all public and private agents (Leiper, 1979; Mathieson and Wall, 1982).

Tourism products and offers originate various types of tourism, leading to a variety of interests and motivations by visitor and/or tourist. Oliveira (2003) defends, thus, the following tourism typology: leisure tourism, events tourism, thermal water tourism, sports tourism, religious tourism, youth tourism, social tourism, cultural tourism, ecological tourism, shopping tourism, nature and adventure tourism, food tourism, incentive tourism, tourism for the elderly, rural tourism, exchange tourism, cruise tourism, business tourism, gay tourism, health tourism, and ethnic and nostalgic tourism.

Culture is the central element in tourism and takes different forms over time and space. The tourism consumption of heritage assets, both tangible and intangible, serves as a lever for creating different types of cultural tourism (Declaration on Cultural Diversity, OECD, 2009). Cultural Tourism has been one of the tourism segments with great focus (Oliveira, 2003) considered by Guerreiro et al. (2014) a promising market segment, with a higher growth trend than other niches.

According to the United Nation World Tourism Organization (UNWTO, 2018), in cultural tourism, the visitor’s essential motivation is to learn, discover, experience, and consume the attractions or tangible and intangible cultural products in a destination. These attractions and products encompass a diverse array of material, intellectual, spiritual, and emotional characteristics that are deeply rooted in society. They embody such elements as arts and architecture, historical and cultural heritage, culinary heritage, literature, music, creative industries and peoples with their lifestyle, value systems, beliefs and traditions. Preserving this rich heritage and its cultural practices is of the utmost importance throughout the entire process. As pertinently argued by Richards (2010), it is through culture, tourism, and leisure that it is possible do convey economic growth and enhance the image of a destination.

Leisure tourism encompasses a wide range of tourism segments and is primarily characterised by trips undertaken for the purpose of pleasure, discovering new destinations, seeking a change of environment, seeking rest and relaxation, reconnecting with friends or visiting relatives, and indulging in the beauty of landscapes while enjoying a holiday with family. This form of tourism can be pursued anywhere, and the desire to explore new attractions and landscapes consistently is the primary motivation for leisure tourists. As a rule, they select places according to the tourism product that best suits their needs (Oliveira, 2003).

Carvalho (2017) presented a cataloguing of tourist strands that integrate the type of cultural tourism, namely: heritage tourism, art tourism, ethnic tourism, literary tourism, gastronomic tourism, indigenous tourism, archaeological tourism, musical tourism, film tourism, festival tourism, historical tourism, military tourism, dark tourism, among others.

The diverse tourism segments mentioned above contribute to the development of alternative tourism destinations, fostering fresh perspectives and new opportunities for various regions. This leads to the emergence of innovative tourism models and the rejuvenation of existing destinations, offering tourists an array of novel experiences and captivating attractions. These transformations enable tourists to actively participate in co-creating their travel experiences, as explored by Neuhofer, Buhalis, and Ladkin (2014). This interactive process of experience co-creation significantly impacts tourists’ decision-making and overall satisfaction with their journeys.

Considering this, in recent years, a new form of tourism known as creative tourism has emerged, stemming from cultural tourism. This evolving trend, often referred to as the “third wave of tourism” by various authors (Carvalho, 2011; Richards, 2010; Santos et al., 2012; UNESCO, 2006), builds upon the progression from beach tourism to cultural tourism. Creative tourism represents a fresh wave of tourism experiences that integrate cultural elements and actively engage tourists in participatory and creative activities.

Creative tourism is based on a growing emphasis on intangible resources (such as traditions, legends, cuisine, among others), enhancing, whenever possible, the historical areas of the regions, helping destinations to differentiate through originality, an essential factor to capture and attract tourists with increasingly demanding needs and interests in what concerns the tourist experiences they want to achieve. Novelty, surprise, excitement, and experience are crucial in tourist choice and motivations, and, therefore, higher levels of quality and satisfaction are achieved, which in turn influence the tourist loyalty towards the destination and/or experienced tourist product (Amorim et al., 2019).

In addition, nature tourism has experienced remarkable growth and increasing demand, both nationally and internationally. The COVID-19 pandemic has further reinforced the appeal of this particular tourism segment as it provides individuals with the opportunity to engage with natural surroundings, seek seclusion, and relish the freedom that comes from being away from densely populated areas prone to virus transmission (Sousa and Joukes, 2022).

This tourism product, based on the immersive experience of the environment, is recognised by the World Tourism Organization (WTO) as an important, dynamic and attractive tourism segment. It can also be effectively combined with other types of tourism, such as sports tourism, business tourism, cultural tourism and rural tourism (WTO, 2002). In line with this, Wang et al. (2019) conducted an investigative study focusing on the determinants of tourism demand specifically within the realm of rural tourism. Their findings highlighted a range of influential factors, including natural resources, cultural heritage, accessibility, government support, and marketing efforts, which significantly shape tourists’ decision-making processes and ultimately impact the overall demand for rural tourism destinations.

Over the years, many definitions of nature tourism have appeared in the literature (Valentine, 1992; Lang and O’Leary, 1997; Cunha, 2007; Bryden et al., 2010; Macouin and Pierre, 2003; Turismo de Portugal, 2023; Tisdell and Wilson, 2012). According to Turismo de Portugal (2023), nature tourism activities fall within the scope of tourist entertainment activities taking place in areas that are part of the National System of Classified Areas (SNAC). To be recognised, these areas must be approved by the Institute for Nature Conservation and Forests, I.P. (ICNF).

The National Nature Tourism Program (PNTN), which was approved by Resolução do Conselho de Ministros (RCM) no. 51/2015, on 21 July, is an integral part of the strategy for promoting nature tourism. Its main objectives include promoting and highlighting the values and potential of classified areas, as well as other areas with natural and cultural significance. Additionally, the program aims to foster the creation of innovative and sustainable tourism products and services. It also seeks to ensure integration and sustainability in various domains, namely nature conservation, local development, enhancement of the tourism offerings, diversification of tourism activities, and dissemination and enhancement of cultural heritage (Turismo de Portugal, 2021).

Nature tourism can be distinguished into two categories: soft nature tourism and hard nature tourism. The former includes lower-risk activities such as walks, excursions, hiking and wildlife watching. Hard nature tourism refers to more radical activities for the tourist, such as rafting, kayaking, hiking, climbing, among others, which require a high degree of concentration or knowledge (for example, birdwatching) (Turismo de Portugal, 2006).

In the case of hard nature consumers, they are generally young people between 20 and 35 years old, students and liberal professionals, practicing/involved in sports or activities of special interest. This type of consumer gathers information in specialised magazines, clubs/associations, and online, where they also buy activities and trips related to the Nature product. The type of accommodation where they stay is Bed and Breakfast, accommodation integrated in nature (country houses, camping...), and mountain refuges. The period when they most look for this type of tourism is spring and summer, normally up to 5 times a year. The activities they do are related to the practice of sports or special interest activities, to deepen the knowledge of nature and about environmental education.

Cunha (2007) has indicated that sun and sea tourism is also one of the types of tourism that maintains high levels of demand, continuing to have quite significant numbers of visitors and income generated. This type of tourism is present in tourist destinations that enable bathing activities on attractive beaches in a natural environment and is therefore a type of tourism that is limited only to the coastal areas of a given territory.

This type of tourism product faces several significant challenges, particularly in relation to spatial planning. These challenges manifest in the form of high levels of tourist concentration, environmental and landscape degradation, especially in coastal areas due to excessive development, pronounced seasonality, and issues of tourist overcrowding. As a consequence, the quality of tourist services can be compromised, with challenges such as precarious employment, inadequately trained human resources, and high turnover rates among staff members, among other concerns (Cunha, 2007). In response to these challenges, continuous efforts have been made over the years to promote innovation, requalification, and reorganisation. Additionally, strategic alliances have been formed with complementary tourism products, including golf tourism, sports tourism, and nautical tourism, among others, while maintaining sun and sea tourism as the primary focus (Cunha, 2007).

Cuisine tourism has also been in the spotlight in recent years, positively influencing the competitive strength and sustainability of a destination, the local economy and regional development (UNWTO, 2017). In 2027, the Strategic Plan for Tourism advocated for cuisine as a “priority strategic asset” (Andrade-Suarez and Caamano-Franco, 2020).

This type of tourism refers to all tourism activities related to the visitor’s experience with food and beverages in destinations that stand out for cuisine (UNWTO, 2012). Hall and Mitchell (2001) have argued that food tourism can include food festivals, food fairs, restaurants, farmers’ markets, food fairs, visits to food-related sites, and food tours.

For Tikkanen (2007), cuisine is considered part of local culture and a tool for local economic development; furthermore, it encourages tourism in the area. According to Kivela and Crotts (2005), food tourism plays an important role in tourists’ decision to revisit a place, in the destinations choice and in destination advertising. It is also one of the main factors that determine the attractiveness of a destination (Aydoğdu et al., 2016).

There are also authors who argue that cuisine may not be considered an essential part of the tourist trip, but it can also lead to the satisfaction of the tourist experience and needs (Björk and Kauppinen-Räisänen, 2019), being an element that may influence the tourist when choosing a destination (Levitt et al., 2019).

The field of tourism has witnessed a multitude of studies exploring the diverse range of factors that drive tourism demand (Wu et al., 2017). According to the comprehensive analysis conducted by Cooper et al. (2007), the factors that significantly influence tourism demand are closely related to models of consumer behaviour. The dimensions of attitudes, perceptions, images, and motivations emerge as preponderant variables in the decision-making process when choosing tourist destinations to visit.

Attitudes reflect individuals’ perceptions of the world, while perceptions involve the mental impressions that shape attitudes and behaviours towards products. Images encompass beliefs, ideas, and impressions associated with tourist destinations and products. Motivations are the inner needs that drive individuals to travel and initiate the demand for tourism.

Considering these dimensions, it becomes possible to gain insights into tourism consumption by:

1) Understanding consumer behaviour and decision-making processes related to tourism products, driven by needs, motivations, and decision processes.

2) Analysing the impact of promotional strategies on consumer behavior.

3) Identifying different market segments based on consumption behaviour.

4) Exploring ways for managers to enhance marketing effectiveness.

Figure 1 provides a simplified representation of the main influences affecting consumer decision-making.

Fig. 1. Framework of consumer decision-making

Source: Copper et al. (2007, p. 79).

Cooper et al. (2007) have proposed a system for analysing the tourism consumer’s decision-making process, consisting of four key elements. These elements include energisers of demand, which are the motivational forces that drive tourists to visit attractions or go on holidays. Demand enhancers involve the influence of learning processes, attitudes, and associations that shape consumers’ perception of a destination or tourism product. The roles and decision-making process highlight the involvement of family members in the various stages of acquiring and finalising decisions about when, where, and how to consume the tourism product. Lastly, determinants of demand play a crucial role in filtering and shaping consumer decisions, considering economic, sociological, and psychological factors that impact travel choices.

Tourist demand is driven by various motivational factors, encompassing sociological and psychological aspects that shape individuals’ norms, attitudes, culture, and perceptions. McIntosh et al. (1995) and Mathieson and Wall (1996) identified four categories of tourists’ motivations.

1) Physical motivators encompass rest, health, sports, and pleasure, providing activities that alleviate tension.

2) Cultural motivators reflect a desire to explore other cultures, learn about local lifestyles, music, art, folklore, dance, and other cultural aspects.

3) Interpersonal motivators involve the motivation to meet new people, visit friends or relatives, and seek unique experiences, offering an escape from routine relationships and satisfying spiritual motives.

4) Status and prestige motivators revolve around personal development, education, ego elevation, and recognition from others, enhancing one’s self-esteem. This category also includes personal growth through hobbies and education.

Regarding the effectors of demand, it is found that the image of a tourist destination is important for the individual because the image a tourist has is part of a general image of a tourist destination, and these two are closely interrelated. It is unlikely that if a tourist does not have a positive image about a destination, they will visit that same destination (Gunn, 1972). The presentation of the image of a tourist destination must be built on an existing image. The notion of image is closely related to the individual’s behaviour and attitudes, which are established based on the image internalised by the person, which will only change if there is the acquisition of new information or experiences. Mayo (1973) has argued that even more important than the image of a place in the choice of a tourist destination is the image that the tourist brings when returning from holiday.

Regarding roles and the decision-making process, the family plays a key role in the tourist destinations choice. According to Cooper et al. (2007), the family exerts influences on the individual since childhood, each element has a special role, and may represent the husband/father, wife/mother, son/brother, and daughter/sister. Decision-making within the family thus has its impact on certain family members and this decision-making can be shared or led by one person, with one family member being the facilitator. The family thus functions as organised purchasing unit whose different role patterns are directed towards particular formats of obtaining tourism products.

Consumer behaviour in the tourism decision-making process is intentional and goal-oriented, with individuals making free choices in their consumption decisions. According to Cooper et al. (2007), who referenced Ajzen and Fishbein (1975), individuals consider the implications of their actions before deciding to engage in a particular behaviour. This decision-making process involves several stages: the emergence and recognition of a need, the level of involvement in the decision process, the identification and evaluation of alternatives, the ultimate choice, the act of purchase, and post-purchase behaviour. In the context of travel, post-purchase behaviour often involves the need for reassurance and confidence renewal, which can be addressed through guarantees, access to customer service, or seeking recommendations from those who have already experienced a similar trip.

Schmoll (1977), as cited by Cooper et al. (2007), presented a model that outlined four fields influencing the final travel decision. These fields include triggers to travel, personal and social determinants, external variables, and the touristic destination itself. Triggers to travel involve external stimuli such as promotional communication and recommendations. Personal and social determinants are linked to travel-related needs, desires, expectations, and perceived risks. External variables encompass factors like trust in service providers, the destination’s image, acquired experiences, and practical constraints. Finally, the touristic destination’s characteristics play a significant role in the decision-making process and its outcome.

In a related model, Mathieson and Wall (1982) focussed on the system of travel buying behaviour, which built upon Schmoll’s model by emphasising external factors and the consumer’s active information-seeking intention. However, this model overlooks key aspects such as perception, memory, personality, and information processing. It primarily takes a product-cantered perspective rather than a comprehensive consumer behavioural perspective. The model consists of five stages, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Travel-buying behaviour model

| First stage | Feeling the need/desire to travel | A desire to travel arises, analysing the reasons for and against that desire. |

|---|---|---|

| Second stage | Information and evaluation | Prospective tourists obtain information with the help of intermediaries, brochures, travel advertisements, friends, family members with experience in travel. The evaluation of this information is confronted with the economic and time constraints, as well as the evaluation of factors such as accessibility and other options. |

| Third Stage | Decision to travel | This stage occurs after the selection of the tourist destination, mode of travel, accommodations and activities. |

| Fourth Stage | Preparing for the trip and travel experience | The trip takes place after confirming reservations, approving budgets, arranging clothes and equipment. |

| Fifth stage | Satisfaction evaluation with the trip | The experience is evaluated as a whole, during and after the trip and the results will have an influence on future travel activities. |

Source: Mathieson and Wall (1982).

These steps are influenced by four interrelated factors, namely:

1) Tourist profile: age, education, income attitudes, experience, and inner motivations;

2) Trip awareness: facilities and services of a tourist destination, considering the credibility of the source;

3) Features and characteristics of the tourist destination: attractions, and aspects of a tourist destination;

4) Travel aspects: distance, duration, and risk perception of the area visited.

Considering the fact that activities are also a fundamental link between the trip and the choice of the tourist destination, Moscardo et al. (1996, in Cooper et al., 2007) presented a different perspective for consumer behaviour, in which the choice of the tourist destination was made according to the activities offered. These authors supported the idea that segments of people who make their trips based on activities could be linked to the activities of tourist destinations through communication strategies and product development.

According to Gutiérrez and Bosque (2010) there is a set of attraction factors, comprising various destination attributes that possess motivational power leading the individuals to desire travel. Considering Abraham Maslow (1970) and the most classical theory on motivation, this concept focuses on universal human needs that span one’s life. Maslow’s hierarchy presents five types of needs (physiological needs, safety needs, love and belonging needs, esteem needs, and self-actualization needs), with higher level needs being fulfilled once the preceding lower-level ones have been satisfied. It is at the third level, where social needs arise, that Puertas (2004) has suggested the conditions are met for tourism to become a part of an individual´s life, as a form of social and cultural attainment, and enabling access to the two upper levels of Maslow’s pyramid, namely esteem and self-actualisation.

Additionally, Puertas (2004) has considered that the realisation of the tourist experience serves as a facilitator for achieving these latter two levels, and tourism motivations correspond to the answers that a tourist will give to the question “Why do I enjoy travelling?”

Undoubtedly, motivation plays a vital role in driving tourist activity (López-Guzmán et al., 2019; Yoo et al., 2018). Tourists embark on their journeys drawn by external forces that extend beyond the destination itself (Yoo et al., 2018). Heritage, cultural and natural resources are the determining factors influencing the tourism development and attractiveness of destinations (Amorim, 2019).

Tourism managers must possess knowledge and awareness of visitors’ and tourists, as well as their decision-making processes, as these factors are integral to the development of tourism in regions. Accordingly, marketing and communication strategies of destinations should be tailored to meet the needs and demands of participants, effectively motivating visitors and tourists to choose the destination (Amorim, 2019; Amorim et al., 2019; Cao et al., 2021; Humagain and Singleton, 2023; Kitterlin and Yoo, 2014).

Our study started from the research question: What motivates and interests tourists to visit the western region of Portugal? Based on this question, the following objectives were outlined:

1) To understand the preferred types of tourism practiced in the western region of Portugal.

2) To examine the factors influencing travel decisions in Portugal and identify the primary reasons for not visiting the region.

3) To identify he most appealing activities and attractions in the region, focusing on the key points of interest in the western of Portugal.

4) To understand the region’s potential for both internal and external promotion.

To address the initial question and meet the established objectives, the following hypotheses were formulated: Hypothesis 1: Sun and sea tourism, along with cultural tourism, are the preferred choices among tourists visiting the western region; Hypothesis 2: The lack of time is the predominant reason cited by tourists for not visiting the western region, despite their interest in exploring the region; Hypothesis 3: In addition to sun and sea tourism, cuisine emerges as a tourism offering with significant potential in the western region; Hypothesis 4: The western region demonstrates substantial potential for promoting integrated activities in creative tourism.

By investigating these hypotheses, we aim to gain valuable insights into the motivations and interests of tourists visiting the western region of Portugal, thus contributing to a deeper understanding of its tourism dynamics.

The methodology employed in this study is quantitative, as it aims to test the formulated hypotheses using structured and statistical quantitative data.

To gather data for this study, a questionnaire survey was applied from January to April 2021. The survey was distributed online, through social networks, and email. A non-probability convenience sample was used, which involved selecting individuals from the population who were easily accessible and willing to answer the questionnaire. The structure of the questionnaire was based on the literature review, as well as on the formulated research question and relevant constructs identified in the literature review. A mixed questionnaire was chosen, which includes open-ended, closed-ended and multiple-choice questions.

This approach enabled a comprehensive exploration of the research topic, enabling respondents to provide qualitative insights while also facilitating quantitative analysis of the collected data.

The initial version of the research instrument underwent analysis by four higher education teachers. Additionally, it was tested with two individuals from the same respondent universe as the study. The purpose of this testing phase was to identify any issues, collect feedback, and address any challenges encountered during the completion of the instrument.

Based on the suggestions and feedback received, necessary changes were made to refine the questionnaire. This iterative process ensured that the instrument was improved and tailored to effectively capture the required data from the respondents.

Once all questionnaires were collected, the data was analysed and interpreted using the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 26. A descriptive analysis of the data was conducted, providing an overview and summary of the collected information.

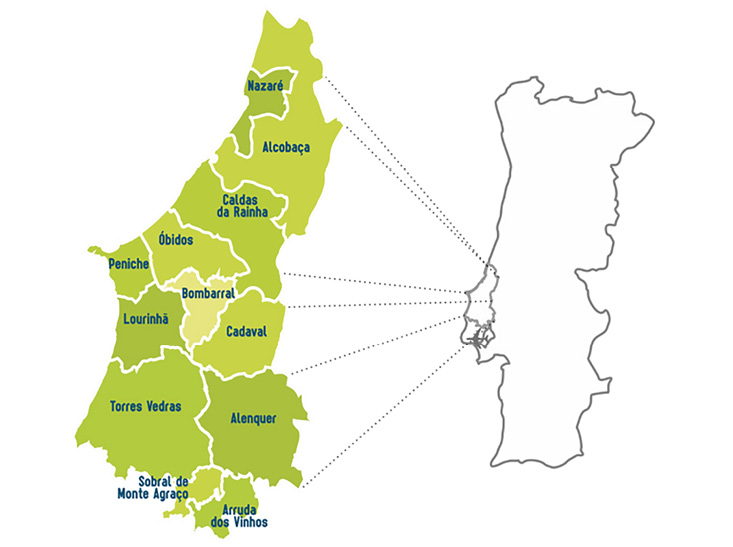

Regarding the study’s focus on the western region, here is a brief background: The region is part of the statistical territorial unit of level III (NUTS III), and is situated within the Central Region of Portugal. It encompasses the northern part of the Lisbon district and the southern part of the Leiria district. Geographically, the region spans an area of 2,486 square kilometres and borders the Lisbon Metropolitan Area to the south, the Lezíria do Tejo to the east, the Leiria region to the north, and the Atlantic Ocean to the west.

The region is widely recognised for its diverse natural and cultural attractions, making it an appealing destination for tourists. It boasts picturesque mountains and vineyards, offering scenic landscapes and opportunities for wine tourism. The region’s stunning cliffs and vibrant blue sea create an ideal setting for nature-based and sun-sea activities. Moreover, the region is home to golf courses, castles, theme parks, and faience, adding to its allure and attracting a wide range of visitors. The rich cultural and natural heritage of the western region enables the creation of customised tourist itineraries that cater to the preferences of tourists. With such a variety of activities and attractions available, tourists can engage in different experiences and explore the region’s unique offerings. This diversity further enhances the appeal of the region as a sought-after destination for travellers. (Turismo de Portugal, 2019).

The western region is highly recognised for its abundant natural resources, which include beaches, mountains, cliffs, and lagoons. In addition to its natural landscapes, the region boasts a rich cultural and historical heritage, with notable landmarks such as castles, churches, convents, and monasteries that contribute to its unique character.

The region also takes pride in preserving its socio-cultural traditions, and historical heritage exemplified through folkloric ranches, thematic events, festivals, and local celebrations. Moreover, it is known for its agricultural products, such as Alcobaça apple, rock pear, wines, and Ginginha de Óbidos (Região Oeste, 2022). This region is composed of 12 municipalities spanning the districts of Lisbon and Leiria. These municipalities are Alcobaça, Alenquer, Arruda dos Vinhos, Bombarral, Cadaval, Caldas da Rainha, Lourinhã, Nazaré, Óbidos, Peniche, Sobral de Monte Agraço, and Torres Vedras.

Fig. 2. Map of West region

Source: multisector.pt.

This section presents the findings of the study on the motivations and interests of tourists visiting the western region of mainland Portugal. According to Table 2, the sample of this study consisted of 355 individuals, 24% male and 76% female. Most of the respondents (63.7%) were married/living together and aged between 31 and 50. Regarding their education, 40.5% had a degree and 34.3% completed secondary education. As for the monthly household income, most individuals have between less than 1000 € and 2000 €.

The main motivations for travelling within the country were leisure (68.2%), family (17%), and work (9.1%), as shown in Figure 3. Also McIntosh et al. (1995) and Mathieson and Wall (1996) identified leisure as one of the main motivations for tourists to travel, as this way people could rest and practice activities that allowed them to reduce tension.

Table 2. Characterisation of the sample

| Variables | Options | Absolut frequency (n) | Relative frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 85 | 24 |

| Female | 270 | 76 | |

| Marital Status | Single | 98 | 27.6 |

| Married/ Living together | 226 | 63.7 | |

| Divorced | 25 | 7 | |

| Widowed | 6 | 1.7 | |

| Age | Under 20 | 10 | 2.8 |

| 21-30 | 56 | 15.8 | |

| 31-40 | 110 | 31.1 | |

| 41-50 | 99 | 28 | |

| 51-60 | 51 | 14.4 | |

| Over 60 | 28 | 7.9 | |

| Academic Qualifications | Basic School | 18 | 5.1 |

| Secondary School | 122 | 34.3 | |

| Undergraduation | 16 | 4.5 | |

| Graduation | 144 | 40.5 | |

| Master`s | 47 | 13.3 | |

| Ph.D. | 8 | 2.3 | |

| Monthly Household Income | Under 1000€ | 79 | 22.1 |

| 1,001−1,500 € | 94 | 26.4 | |

| 1,501−2,000 € | 82 | 23.2 | |

| 2,001−2,500 € | 42 | 11.7 | |

| 2,501−3,000 € | 19 | 5.4 | |

| 3,001−3,500 € | 15 | 4.3 | |

| 3,501−4,000 € | 7 | 2 | |

| Over 4,000€ | 17 | 4.9 |

Source: own work.

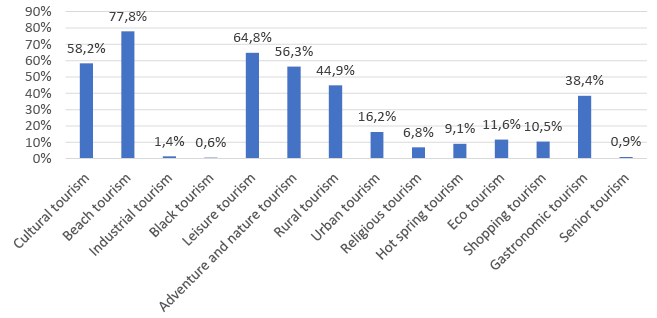

The survey results indicate that the individuals surveyed expressed a strong preference for certain types of tourism in the western region of mainland Portugal. The most favoured types of tourism among the respondents were beach tourism (77.8%), leisure tourism was the second most popular choice (64.8%). Cultural tourism also ranked high (58.2%), and adventure and nature tourism garnered significant attention as well (56.3%). The least preferred types of tourism among the respondents were black tourism (0.6%), senior tourism (0.9%), industrial tourism (1.4%), and religious tourism (6.8%), as shown in Fig. 4. These findings provide insights into the specific tourism preferences of the surveyed individuals, where resting, enjoying the sun and sea, contact with culture and exploring nature were the respondents’ main motivations.

Fig. 3. Factors responsible for trips within Portugal

Source: own work.

This data also reveals that the sample of this study aligns with two of the four categories of tourists’ motivations proposed by McIntosh et al. (1995) and Mathieson and Wall (1996), namely: physical motivators, which encompass activities aimed at resting the body and mind, addressing health concerns, engaging in sports, and seeking pleasure as a means to reduce tension; and cultural motivators, which reflect the desire to explore and learn about other cultures, local lifestyles, music, art, folklore, dance, and various cultural aspects (McIntosh et al., 1995; Mathieson and Wall, 1996).

Fig. 4. What type of tourism would you like to practice in the western region

Source: own work.

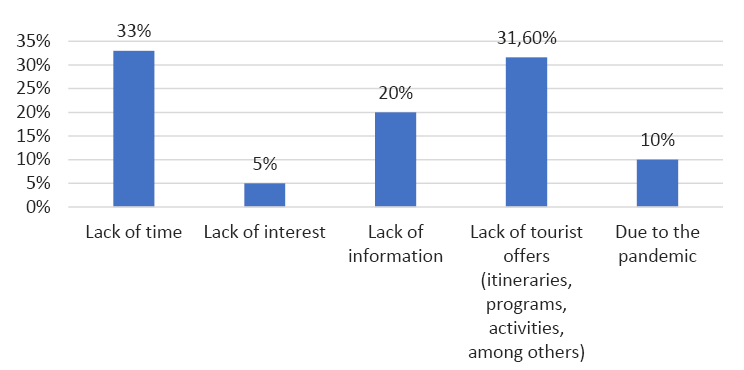

The western region has already been visited by most of the respondents (94.5%). Those who had not done so indicated as the main reasons the lack of time (33%) and the lack of tourist offers (itineraries, activity programs, among others) (31.6%). Figure 5 shows that the lack of interest in visiting the region is not a predominant reason, but it is important to invest in attractions to attract tourists to the region and disseminate more information about it. This data suggests that there may be some weaknesses in the communication strategies, and as Moscardo et al. (1996, in Cooper et al., 2007) argued that consumer behaviour in the choice of a tourist destination was influenced according to the activities offered, being the communication and product development strategies crucial in the decision-making process.

Fig. 5. Reasons for not visiting the western region

Source: own work.

The previous premise was confirmed when the respondents were asked directly about their interest in visiting the western region, where it could be seen that more than half (59.1%) said they were interested and 40.9% said they could be, and none of the respondents said they were not interested in getting to know the region. With these results one can induce that the region gathers tourist products and offers that motivate the displacement of many visitors and tourists to the region, considered by the Tourism of Portugal and by many who visit it one of the most fascinating and diversified tourist destinations of the Centre of Portugal.

According to Fig. 6, the most popular attractions in the western region are the beaches (85.7%), the fauna and flora (61.9%), the mountains (57.1%), the caves (47.6%), and the gastronomy (42.9%). In contrast, the region is less known for its fishing (4.8%), its winemaking (9.5%), and the preparation of food products such as honey, cheese, jams (19.2%), etc. There were also 4.8% of those who said they did not know at all about the attributes of the region. This data may suggest that it is crucial to invest in the promotion and dissemination of the western region’s attractions, also reflected in the results obtained according to Fig. 6, also revealing that this region is known, essentially and mostly, for its most visible natural elements, such as its beaches.

Fig. 6. Attractions you know in the western region

Source: own work.

Considering Fig. 7, the most desired tourist offerings in the western region, as indicated by the respondents, are the beach (4.54), mountains (4.41), cuisine (4.37), and caves (4.15). These are also the most well-known offerings. However, it is important to shed light on the remaining tourist offerings that the region has, which may not be as promoted and thus still unfamiliar to the majority of respondents. Considering that tourists often prioritise personalised and experiential visits to destinations (Borlido and Kastenholz, 2021), this calls for a reflection on the need for increased investment in communication and dissemination strategies in the region.

As Cooper et al. (2007) have argued, the decision-making process of the tourism consumer is integrated into a system consisting of four basic elements: demand energisers, demand effectors, the roles and process of decision making, and the determinants of demand. Furthermore, the choices made by tourists when selecting destinations are influenced by both their personal preferences and the characteristics of the destination itself (Yoo et al., 2018). These results highlight the importance for tourism agents and stakeholders to focus on demand energisers, which are the motivational forces that drive tourists to visit attractions or go on holidays, and the demand effectors, which shape the consumer’s perception through learning processes, attitudes, and associations influenced by promotional messages and information. These two interrelated factors are essential and influence the increase or decrease of consumer attitudes.

Scale: 1 – I would not like it at all; 5 – I would like it a lot

Fig. 7. Tourist attractions I would like to explore in the western region (average)

Source: own work.

87% of the respondents have already stayed overnight in the western region and 72.4% said they had access to information about the region. However, 27.6% of respondents said they had never received information about the region, which suggests the need for more information about the region, which could be an attraction to interest more tourists in the region.

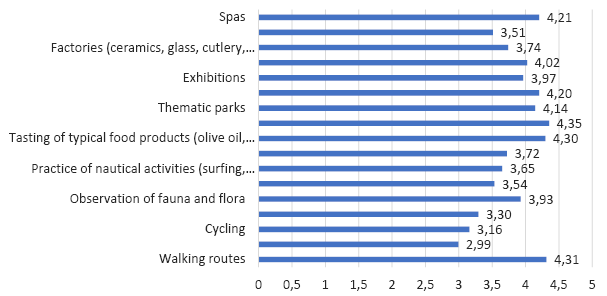

As shown in Fig. 8, the activities that respondents would most like to experience in the region are rural tourism farms (4.35), walking trails (4.31), tasting typical food products (4.30), and spas (4.21). The preference for these activities corresponds to the type of tourism that respondents also revealed they prefer. The least appealing activities were hang gliding (2.99) and cycling (3.16), i.e., activities that involve more physical exercise and adventure. However, the majority of the individuals surveyed were willing to try most of the activities.

Fig. 8. Activities I would like to do in the western region (average)

Source: own work.

Figure 9 reveals that more than half of the respondents (56.2%) if they participated in a tourist itinerary they would prefer to travel by car, followed by public transport (20.9%), and walking (12.7%). These results give an indication to the tourism agents, such as, for example, travel agencies that conduct this type of program and tourist offer, that the planning of tourist itineraries may consider this travel preference indicated by the study sample.

Fig. 9. How would you like to get around if you participated in a tourist itinerary

Source: own work.

The western region of Portugal is rich in natural and cultural resources, making it essential for tourism managers to identify the main motivations of tourists to strategically promote the various attractions of the destination.

The study results have confirmed three out of the four research hypotheses formulated for this study. In hypothesis 1, which suggested that tourists in the region preferred sun and sea tourism and cultural tourism, was confirmed. The survey results revealed that the highest percentages were indeed for sun and sea tourism (77.8%) and cultural tourism (58.2%). Additionally, leisure tourism (64.8%), and adventure and nature tourism (56.3%) were also preferred by the respondents. Rural tourism (44.9%) and food tourism (38.4%) were also highlighted as significant preferences among the respondents.

Hypothesis 2, proposing that the main reason for tourists not visiting the western region was a lack of time despite their interest, was not confirmed. Instead, the data indicated that the main reasons for not visiting the region were attributed to a lack of tourist offers (31.6%), and a lack of information (20%). These findings suggest the need for tourism managers to reconsider their communication and marketing strategies while also enhancing the attractiveness of their tourism offerings to generate greater motivation and interest among tourists capturing their visit and/or stay.

Hypothesis 3, which stated that one of the touristic offers in the western region with a lot of potential and tourist demand, besides tourism sun and sea, would be cuisine, was confirmed. Cuisine emerged as a preferred demand among tourists, following beach tourism, with 42.9% of respondents expressing their interest.

Hypothesis 4, proposing that the region has a strong potential for promoting integrated activities in creative tourism, was confirmed. The survey revealed that the activities with the highest interest among respondents were visits to crafts and handicrafts, picking of seasonal fruit, and participating in the preparation of handmade food products. These findings suggest that creative tourism has potential in the tourism development in the western region. The data obtained and the touristic activities indicated are integrated in creative tourism practices. This data can constitute important indicators for tourism managers to explore the practices of creative tourism and, thus, redefine their lines of action in the products promotion and tourist offers that are under their responsibility. In summary, the study’s findings highlight the main motivations of the surveyed individuals in the region, with preferences for sun and sea tourism (77.8%), leisure tourism (64.8%), cultural tourism (58.2%), adventure and nature tourism (56.3%), and food tourism (38.4%).

According to McIntosh et al. (1995) and Mathieson and Wall (1996) tourists’ motivations can be categorised into four main categories: physical motivators, cultural motivators, interpersonal motivators and status and prestige. In this research, the most prominent motivational factors (energisers of demand, Cooper et al., 2007) are physical motivators, which encompass the desire to rest the body and mind, engage in health-related activities, participate in sports, and seek pleasure. Cultural motivators, though, revolve around the curiosity to explore and understand the cultural aspects of the region.

These findings underscore the significance of cultural tourism, and creative and experiential tourism, where visitors interact and engage with the social environment of the destination, leading to unique and authentic experiences (Amorim, 2019; Campos et al., 2018; Long and Morpeth, 2016). This information is crucial for mayors and tourism agents in order to invest in and enhance tourism offerings in these specific areas.

From a theoretical perspective, the implications of this research affirm that motivation is a key driving force behind tourism activity (López-Guzmán et al., 2019; Yoo et al., 2018). Tourists are attracted to destinations by external forces (Yoo et al., 2018), and the attractions of a destination are pivotal factors in its tourism development and attractiveness (Amorim, 2019, 2020).

For tourism managers, it is vital to understand the participants’ tourism and recognise the essential role of decision-making processes. The marketing strategy must consider the participants’ needs and demands (Amorim, 2019; Humagain and Singleton, 2023; Kitterlin and Yoo, 2014). A well-defined plan based on touristic motivations can also influence the motivation to revisit the same destination or explore neighbouring destinations in order to continue to achieve satisfying experiences, thus contributing to touristic loyalty (Amorim et al., 2019; Cao et al., 2021).

The practical implications of the research are related to the contribution to a better understanding of tourists’ interests and motivations to visit the western region. This knowledge provides added value for tourism management entities, enabling them to improve and enhance their tourism products while recognising the importance of effective communication strategies. Therefore, by utilising the research findings, these entities can create enriching tourism experiences that capitalise on the region’s potential and align with the interests and motivations of tourists, ultimately attracting more visitors.

This study has some limitations that should be acknowledge. Firstly, considering the nature of the research, it focused solely on the western region of Portugal, which has its own unique characteristics and attractions. Therefore, the findings may not be generalisable to other regions or destinations.

Additionally, the sample size could have been larger, but it was constrained due to the data collection period coinciding with the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic likely had an impact on the number of responses obtained, potentially limiting the representativeness of the sample.

Furthermore, as with any survey-based research, there is a possibility of response bias or self-selection bias. The respondents who chose to participate in the study may not fully represent the entire population of tourists visiting the region.

It is important to consider these limitations when interpreting the results of the study and to exercise caution in generalising the findings beyond the specific context of this region of Portugal. Future research could aim for larger and more diverse samples, encompassing multiple regions, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of tourists’ motivations and interests in Portugal also considering differences of tourists living in large cities compared to those living in rural areas.

Acknowledgements. This work is financed by national funds through FCT - Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P., under the project reference no. UID/B/04470/2020.

AJZEN, I. and FISHBEIN, M. (1975), ‘Understanding attitudes and predicting social behavior’. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall’, [in:] COOPER, C., FLETCHER, J., FYALL, D. GILBERT, A. and WANHILL, S. (2007). Turismo: Princípios e práticas (3ª ed.), pp. 64−105, Porto Alegre: Bookman.

AMORIM, D. (2019), Turismo cultural, turismo criativo e animação turística em eventos locais: Análise da motivação, qualidade, satisfação e fidelidade em dois festivais de artes performativas, Tese de Doutoramento. Universidade de Sevilha, Faculdade de Turismo e Finanças, Espanha.

AMORIM, D., JIMÉNEZ-CABALLERO, J. and ALMEIDA, P. (2019), ´Motivation and tourists’ loyalty in performing arts festivals: the mediator role of quality and satisfaction´, Enlightening Tourism. A Pathmaking Journal, 9 (2), pp. 100−136. https://doi.org/10.33776/et.v9i2.3626

ANDRADE-SUAREZ, M. and CAAMANO-FRANCO, I. (2020), ´The relationship between industrial heritage, wine tourism, and sustainability: a case of local community perspective´, Sustainability, 12 (18), pp. 1−21. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187453

AYDOĞDU, A., ÖZKAYA, O. E. and KÖSE, Z. C. (2016), ´Destinasyon Tercihinde gastronomiturizmi’nin önemi: Bozcaada örneği´, Uluslararası Türk Dünyası Turizm Araştırmaları Dergisi, 1 (2), pp. 120−132.

BORLIDO, T. and KASTENHOLZ, E. (2021), ‘Destination image and on-site tourist behaviour: A systematic literature review’, Journal of Tourism & Development, 36 (1), pp. 63−80.

BJÖRK, P. and KAUPPINEN-RÄISÄNEN, H. (2019), ´Destination foodscape: A stage for travelers’ food experience´, Tourism Management, 71, pp. 466−475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.11.005

BRYDEN, D. M., WESTBROOK, S. R., BURNS, B., TAYLOR, W. A. and ANDERSON, S. (2010), Assessing the economic impacts of nature based tourism in Scotland Scottish Natural Heritage, (Commissioned Report nº398) Scottish Natural Heritage.

CAMPOS, A. C., MENDES, J., DO VALLE, P. O. and SCOTT, N. (2018), ‘Co-creation of tourist experiences: a literature review’, Curr. Issues Tourism, 21 (4), pp. 369–400, https://doi. org/10.1080/13683500.2015.1081158

CAO, L; QU, Y. and YANG, Q. (2021), ‘The formation process of tourist attachment to a destination’, Tourism Management Perspectives, 38, pp. 1−15, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100828

CARVALHO, G. (2017), ´Turismo cultural´, [in:] SILVA, F. and UMBELINO, J. (Coord.). Planeamento e desenvolvimento turístico, pp. 349−363, Lisboa: Lidel.

CARVALHO, R. (2011), Os eventos culturais e criativos poderão ou não contribuir para uma imagem diferenciadora do destino turístico maduro?, Tese de Mestrado em Desenvolvimento de Produtos de Turismo Cultural. Escola Superior de Gestão, Instituto Politécnico de Tomar, Portugal.

COOPER, C., FLETCHER, J., FYALL, A., GILBERT, D. and WANHILL, S. (2007), Turismo: Princípios e práticas (3ª ed.), Porto Alegre: Bookman.

CUNHA, L. (2007), Introdução ao Turismo, Lisboa: Verbo.

CUNHA, L. and ABRANTES, A. (2013). Introdução ao Turismo (5ª ed.), Lisboa: Verbo Editora.

GUNN, C. (1972), Vacationscape: Designing tourist regions, Austin: Bureau of Business Research, University of Texas at Austin. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728757301100306

GUTIÉRREZ, H. and BOSQUE, I. (2010), ‘Los factores estimulo y personales como determinantes de la formación de la imagen de marca de los destinos turísticos: un estudio aplicado a los turistas que visitan un destino vocacional’, Cuadernos de Economía y Dirección de la Empresa, 43, pp. 37−63. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1138-5758(10)70009-8

HALL, C. and MITCHELL, R. (2001), Wine and Food Tourism, Brisbane: Wiley.

HUMAGAIN, P. and SINGLETON, P. (2023), ‘Reprint of: Exploring tourists’ motivations, constraints, and negotiations regarding outdoor recreation trips during COVID-19 through a focus group study’, Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 41, pp. 1−11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jort.2021.100447

JIMENÉZ, E. and MARTÍN, R. (2004), Analisis y tendencias del turismo, Spain: Edição Piramide.

KIVELA, J. and CROTTS, J. C. (2005), ´Gastronomy tourism: a meaningful travel market segment´, Journal Culinary Science Technology, 4 (2–3), pp. 39−55. https://doi.org/10.1300/J385v04n02_03

LANG, C. T. and O’LEARY, J. T. (1997), ´Motivation, participation, and preference: A multisegmentation approach of the Australian nature travel market´, Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, 6 (3−4), pp. 159−180. https://doi.org/10.1300/J073v06n03_10

LEIPER, N. (1979), ´The framework of tourism: Towards a definition of tourism, tourist, and the tourist industry´, Annals of Tourism Research, 6 (4), pp. 390−407. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(79)90003-3

LEVITT, J. A., ZHANG, P., DIPIETRO, R. B. and MENG, F. (2019), ´Food tourist segmentation: Attitude, behavioral intentions and travel planning behavior based on food involvement and motivation´, International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Administration, 20 (2), pp. 129−155. https://doi.org/10.1080/15256480.2017.1359731

LICKORISH, L. and JENKINS, C. (1997), An introduction to tourism, Scotland: Reed Educational and Professional Publishing, Lda.

LONG, P. and MORPETH, N. (2016), Tourism and the Creative Industries, London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315735870

LOPEZ-GUZM, T, TORRES-NARANJO, M., PÉREZ-GÁLVEZ, J. C. and CARVACHE-FRANCO, W. (2019), ‘Segmentation and motivation of foreign tourists in world heritage sites. A case study, Quito (Ecuador)’, Curr. Issues Tourism 22 (10), pp. 1170–1189. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2017.1344625

MACOUIN, D. and PIERRE, I. (2003), Le tourisme de nature, Nantes: AFIT.

MASLOW, A. H. (1970), Motivation and personality (2ª ed.), New York: Harper & Row.

MATHIESON, A. and WALL, G. (1982), Tourism: Economic, physical and social impacts, London, New York: Longman.

MATHIESON, A. and WALL, G. (1996), Tourism: Economic, physical and social impacts, Harlow: Logman Scientific & Technical.

MAYO, E. J. (1973), ´Regional images and regional travel destination´. Proceedings of the Fourth Annual Conference of TTRA, pp. 211- 217, Salt Lake City, UT: Travel and Tourism Research Association.

MCINTOSH, R. W., GOELDNER, C. R. and RITCHIE, J. R. B. (1995), Tourism: Principles, practices and philosophies (7ª ed.), New York: John Wiley & Sons.

NEUHOFER, B., BUHALIS, D. and LADKIN, A. (2014), ‘A typology of technology‐enhanced tourism experiences’, International Journal of Tourism Research, 16 (4), pp. 340−350. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.1958

OLIVEIRA, A. (2003), Turismo e desenvolvimento: Planejamento e organização (4ª ed. revista e ampliada), São Paulo: Editora ATLAS.

OMT (2002), Cumbre Mundial del Ecoturismo: Informe final, Madrid: Organização Mundial del Turismo.

PUERTAS, X. (2004), Animación en el âmbito turístico. Ciclos formativos. FP Grado Superior Hostelaría y Turismo, Madrid: Editorial Sintesis.

REGIÃO OESTE, http://www.airo.pt/caracterizacao-da-regiao/ [accessed on: 01.06.2022].

REGIÃO OESTE, https://turismodocentro.pt/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Guia-Sub-Regional_Oeste.pdf [accessed on: 01.06.2022].

RICHARDS, G. (2010), ´Tourism development trajectories: From culture to creativity?´ Encontros Científicos. Tourism & Management Studies, 6, pp. 9−15.

SANTOS, J., CARVALHO, R. and FIGUEIRA, L. (2012), ´A importância do turismo cultural e criativo na imagem de um destino turístico´. Revista Turismo e Desenvolvimento – Produtos, destinos, economia, 3 (17/18), pp. 1559−1572.

SCHMOLL, G. A. (1977), Tourism Promotion, Londres: Tourism International Press, [in:] COOPER, C., FLETCHER, J., FYALL, A., GILBERT, D. and WANHILL, S. (2007), pp. 64−105, Turismo Princípios e Práticas (3ª ed.), Porto Alegre: Bookman.

SMITH, V. L. (1989), ´Hosts and Guests: The Anthropology of Tourism´ (2ª ed.). University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, PA., [in:] COOPER, C., FLETCHER, J., FYALL, A., GILBERT, D. and WANHILL, S. (2007), Turismo Princípios e Práticas (3ª ed., pp. 238−265), Porto Alegre: Bookman.

SOUSA, A. E. and JOUKES, V. (2022), ´O impacto da pandemia na hotelaria em Portugal Continental em 2020: Medidas e estratégias´, Tourism and Hospitality International Journal, 18 (1), pp. 116–138, https://thijournal.isce.pt/index.php/THIJ/article/view/56.

TIKKANEN, I. (2007), Maslow’s hierarchy and food tourism in Finland: five cases. British Food Journal, 109 (9), pp. 721−734. https://doi.org/10.1108/00070700710780698

TISDELL, C. and WILSON, C. (2012), Natured-based Tourism and Conservation-New Economic Insights and Case Studies. Northampton, EUA: Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781781005163

TURISMO DE PORTUGAL (2019), https://www.sgeconomia.gov.pt/noticias/ine-estatisticas-do-turismo-em-portugal-2019-span-classnovo-novospan1.aspx [accessed on: 22.05.2022].

TURISMO DE PORTUGAL (2021), https://business.turismodeportugal.pt/SiteCollectionDocuments/ordenamento-turistico/guia-orientador-abordagem-ao-turismo-na-revisao-de-pdm-out-2021.pdf [accessed on: 10.07.2023].

TURISMO DE PORTUGAL (2023), https://business.turismodeportugal.pt/pt/Planear_Iniciar/Licenciamento_Registo_da_Atividade/Agentes_Animacao_Turistica/Paginas/reconhecimento-das-atividades-como-turismo-de-natureza.aspx [accessed on: 10.07.2023].

UNESCO (2006), Towards sustainable strategies for Creative Tourism. Discussion Report of the Planning Meeting for 2008 International Conference on Creative Tourism. Santa Fé, New Mexico: USA, http://portal.unesco.org/culture/en/files/34633/11848588553oct2006_meeting_report.pdf/oct2006_meeting_report.pdf [accessed on: 27.02.2016].

UNWTO (2012), Global Report on Food Tourism, World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), Madrid, https://webunwto.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2019-09/food_tourism_ok.pdf [accessed on: 10.05.2022].

UNWTO (2017), Second global report on gastronomy tourism: sustainability and gastronomy, https://www.unwto.org/archive/global/press-release/2017-05-17/2nd-unwto-report-gastronomy-tourism-sustainability-and-gastronomy [accessed on: 10.05.2022].

UNWTO (2018), Report on tourism and culture synergies, Madrid: United Nations World Tourism Organisation, https://www.e-unwto.org/doi/epdf/10.18111/9789284418978 [accessed on: 10.05.2022].

YOO, C. K., YOON, D. and PARK, E. (2018), ‘Tourist motivation: an integral approach to destination choices’, Tourism Review. 73 (2) pp. 169–185. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-04-2017-0085

VALENTINE, P. (1992), Review: Nature-based tourism. Special Interest tourism, London: Belhaven Press.

WANG, R., HUANG, P., HU, J. and LI, Y. (2019), ‘Study on rural tourism experience of Wuyuan County based on online travel note’, Resources Sciences, 41, pp. 372–380.

WU, D. C., SONG, H. and SHEN, S. (2017), ‘New developments in tourism and hotel demand modeling and forecasting’, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29 (1), pp. 507−529. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-05-2015-0249