The main objective of a case study and a planning process is to develop a community that safeguards common values and good living conditions for all groups, within the framework of sustainable development. Participatory processes and transparency in urban policies and spatial planning have positive effects on the legitimacy of decision-making processes for the well-being of every member of a community. The good and effective facilitation of public participation in planning is vital in securing well-functioning and efficient planning processes. However, it is also crucial for public participation to be a constant and recurring process, since it is a complex organisation that requires not only time and resources, but also the willingness of the actors. Therefore, the management and sustainability of a participation process require power, communication, and management skills in urban planning activities.

The case study in question acknowledges that the proposed municipal masterplan for Baleal Beach (Portugal) has resulted in conflicts and disputes between the stakeholders, where the lack of communication was severe. In this report, the authors suggest the implementation of a participatory approach in the spatial and urban planning processes overseen by the municipality as a solution to the problems analysed in Baleal Beach.

The report starts with an analysis of the Baleal case study, which includes a site visit and a stakeholder meeting, as well as a literature review to expand the knowledge about participation and community. Therefore, it is followed by a stakeholder analysis to understand the qualities of the actors involved in the process. Furthermore, a SWOT analysis of the implementation of the participation process led by the municipality is conducted to examine the consequences. In conclusion, actionable policies such as public consultation, grievance redressal, accessible disciplinary and scientific information, and creating minor design interventions in public spaces to start the conversation are suggested for an effective and transparent participation process as a planning tool, where the municipality is the key leader and the responsible actor.

A lack of transparency in governance and public participation in the decision-making process is the primary impediment to the implementation of effective planning proposals. According to Jorge et al. (2022), in Portugal there is a law that ensures public participation as a principle in public administrative actions and policies concerning land, urbanism, and spatial planning. The practice of the principle of citizen participation in inter-municipal programmes and the municipal master plans is fulfilled by periodic binding public discussions on the proposed plans and programmes. Citizen participation is ensured during the development, modification, alteration, and evaluation steps (Jorge et al., 2022). However, in Baleal, the citizens’ reaction to the plan has shown that the current instruments and policies for participation in planning procedure have either not been implemented or have not produced the expected results. This report aims to conduct an investigation and provide recommendations that can help the state apparatus understand the importance of participation. In fact, stakeholder participation is fundamental in planning service delivery and infrastructure investment with minimal conflict. The inquiry and recommendations proposed have been supported by a literature review of current and best practices, field study, stakeholder analysis, and SWOT analysis.

Participation and community are two words at the heart of the analysis conducted and instrumental in the policy recommendations. Participation is key because it is lacking in the process of spatial planning, but also something that is desired and recommended by international observer bodies (Jackson et al., 2010). Community is of key importance by dint of the conflict it has with the state. More importantly, it must live with the consequences of state actions. The state is sovereign and thus the final authority that decides about whether to implement an agenda either conceptualised by itself or by bodies that give legitimacy to the state.

Participation, on the one hand, has been defined as an action in which there is a sense of sharing or association. It has also been described as an intervention or an instrument to participate in the democratic process of the state (Van Cauwenbergh et al., 2018). It is an indication that a representative democracy operates with the consent of those who elect the representatives. In the case of planning, we can also find examples of people who bring to surface the internal contradiction in the word participation (‘part takers’) and depart from a process that is deceptive in its conception (Kaika, 2017).

Community, on the other, is the unit through which individuals can claim the liberties that are guaranteed to them in the state framework in which they live (Nancy, 1986). It is necessary for a community to recognise itself beyond the individual and as the subject of the state. It is necessary because through this self-realisation, the community can act as an agent of change to affect state policy.

The Portuguese law requires public participation, in principle. Furthermore, it recommends it on the municipal level for the evaluation and revision of planning documents (Jorge et al., 2022). There is also an educational instrument at the national level that works to inform various stakeholders about planning proposals and mobilise them to action to evaluate development programs. In the Portuguese legal framework the intention is for both participation and community to be active in the governance process. There is also a state portal where people can access policy documents and plans related to specific development proposals.

Participatory planning has also been recommended as a necessary planning tool by international observers. Local Agenda 21 affirmed that the state must involve the community in the decision-making process to ensure sustainable development (Jackson et al., 2010). Although the processes of ‘consensus building’ and ‘community’ as mentioned in the UN document have been problematised by various authors, the fundamental conceit has not been questioned (Jackson et al., 2010; Kaika, 2017). The idea of ‘community’ with respect to territory has been problematised by questioning whether a community can be recognised within a territory. This can then be used to question whether businesses operate within geographical or economic space, while also raising questions related to the effectiveness of administrative jurisdictions (Jackson et al., 2010). The issues raised relate to the language used in planning documents and the academic literature that analyses them. The chief issue is that of communication, i.e., the inability of the state to communicate with constituents and of disciplinary professionals to communicate with people with highly specific knowledge, but in disciplines other than planning.

Solutions to these problems include better standards of communication, as well as the creation and accessibility of appendices to planning literature, which can help people from different areas of knowledge understand each other. The challenge is for the literature and the planning process itself to become simple enough for everyone to understand (Weston et al., 2013). There are also other means through which communities have intervened in the planning process. This has happened through collective action and an organised and educated citizens. Citizens have participated in the planning process by refusing to participate in it, thus creating a contradiction for the state to resolve. In other cases, people came together to re-examine the legitimacy that they had bestowed on the state. Elsewhere, people chose to collectively become large stakeholders in the state apparatus by buying state resources and becoming investors in the state (Kaika, 2017).

Documented cases of the participatory approach to planning can be found in Spain, where stakeholder workshops were conducted based on stakeholder interest-power dynamic to facilitate a water management project. It resulted in the creation of working groups of stakeholders who would be directly or indirectly affected by the program (Cauwenbergh et al., 2018). Recommendations have been made for the creation of an indicator system that could assess community health and help state actors understand concepts such as belonging and ‘social cohesion’ (Erdiaw-Kwasie and Basson, 2018). Mapping studies in Zimbabwe and Sweden have been conducted to assess the subjects’ perception of a particular space to help planners in a consolatory manner, forming real links between the state and the subjects (Preto et al., 2016).

In conclusion, participatory planning has a legal and principled grounding in the Portuguese law. There is sufficient evidence to suggest that it can be used and it can evolve to work in multiple contexts. In addition, there are examples where people themselves were able to create planning instruments in the absence of state action.

Many research methods were used in the report, enabling a comprehensive analysis. The first and main method used for the research was case study analysis. Crowe et al. (2011) argued: “Case studies analysis can be used to explain, describe or explore events or phenomena in the everyday contexts in which they occur.” This method was used to identify the main problems in the area. The second method was a literature review. It is used to broaden the knowledge and understanding of an issue. It also specifies which methods can be used in the case and helps to identify, select, and analyse information (Kallet, 2004).

A field visit is a method that requires travelling to the site of analysis. In this method, it is important to take pictures and speak with residents to get an understanding of the first-hand experiences at the site of the study (Eden, 2019). During the survey, photographic documentation was collected, which enabled us to prepare a map of the study area. The ‘local talking session’ took place on 10 May 2022 and was a meeting with local citizens. This helped us better identify the problems and learn more about the area from the citizens’ perspective and led to the formulation of the main problems.

A stakeholder analysis is a method that leads to the selection of key stakeholders, i.e., people who will be affected or who are going to affect others. There is a need to identify and categorise them. Power versus interest grids is one of the research tools for mapping stakeholders. They help understand the underlying power dynamics between the state and people, as well as internal contradictions in these groups (Bryson, 2004). A SWOT analysis is a method used to identify strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. Strong and weak points are identified by examining the aspects of the environment, while opportunities and threats come from outside the environment (Gurel, 2017). These methods were instrumental for the authors in devising policy recommendations. A policy recommendation is a written advice for the authorities or people who are currently considered to have significant influence and power (CARDI, 2012).

Peniche is a tourism destination in the western part of Portugal with 27,753 inhabitants and an area of 77.55 sq. km. It has become a popular surfing destination in recent years. There has also been a growth in foreign population from 3.1% to 6.7% over the last 11 years.

The focus of our case study is Baleal Beach, which is part of the Peniche municipality (Fig. 1). It is a unique place with a beautiful view and, as one local resident said, a good place for people learning to surf. The tourism sector is a fundamental economic area for the generation of wealth and employment in Portugal, contributing to the growth and development of many territories, either on the coast, associated with sun and sea tourism, city breaks and golf tourism, or in the interior, within nature tourism, and cultural and cuisine tourism. The locals are content with the fact that tourism growth is occurring, but they are not interested in mass tourism. They would prefer sustainable high-quality tourism where one can also enjoy pristine nature. Many people come to Baleal Beach in caravans, causing heavy traffic in the city during the holiday season. There are also many problems in the spatial development of public spaces.

Fig. 1: Photo locations in Baleal Beach

Source: own work based on Open Street Map.

The main problem identified in the Baleal Beach area is the lack of communication between the municipality and the inhabitants. Residents want to be heard by the authorities and involved in the development process of their town, but to unite them, they need to find a way that will interest them in this process. As the inhabitants concluded in the ‘local talking’ session, “it is hard to get everyone talking to everyone.” This applies to both relationships: first, between the municipality and its residents; and second, between the residents themselves. There is also a problem with the organisation of spatial planning and transparency of decisions. The conflict was triggered by a new municipal master plan that was launched in 2012. Residents only learned about the planned solutions after it was announced and were not asked about any proposals that they would like to include in the city space. The space should be given to the inhabitants and mostly they should decide what their surroundings should look like. Social participation in this area does not run properly, which creates many misunderstandings.

Considering the proposed plan for Baleal Beach and Ferrel parish, we have also identified the following four issues in this area:

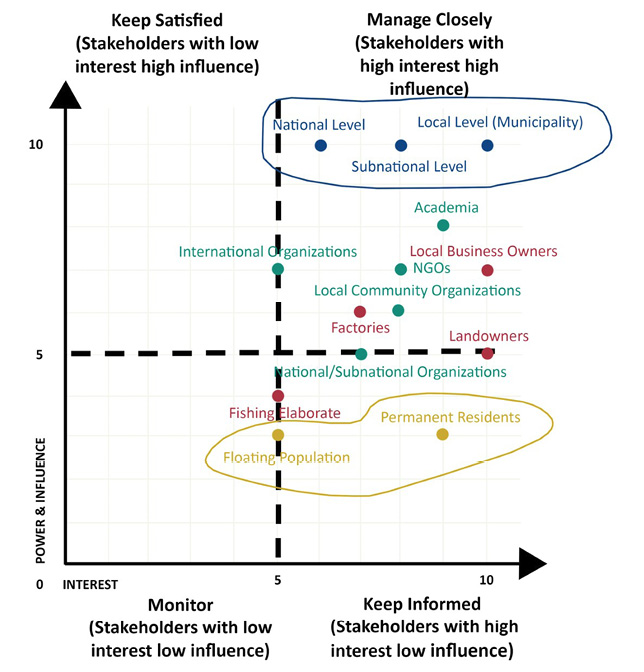

In the Baleal case study, a wide range of stakeholders has been defined and classified into four categories: investors, the government, inhabitants, and civil society. Furthermore, these categories have been divided into subcategories for a better understanding of their power-influence and interest levels on a scale of 1–10. The scores have been assigned based on a socio-economic analysis considering the various groups involved and include the following factors:

Considering the above parameters, we have classified stakeholders into categories of investors, the government, inhabitants, and civil society. The grades given to each member of a category class reflect our perception of the power they hold and the interest they may have in a planning exercise conducted by the state. These are in accordance with the considerations made above.

Table 1. Stakeholder analysis

| Category | Stakeholder | Characteristics | Power (1–10) | Interest (1–10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Investors | Landowners | Agricultural land Second homes |

5 5 |

10 7 |

| Local business owners | Hotels Bars Surfing businesses Supermarkets Restaurants Tourism related Shops (other) Real estate |

6 5 7 5 5 7 4 7 |

10 9 10 9 9 10 8 10 |

|

| Factories | 6 | 7 | ||

| Fishing | 4 | 5 | ||

| Government | Municipality | 10 | 10 | |

| Regional | 10 | 8 | ||

| National | 10 | 6 | ||

| Inhabitants | Permanent residents | Workers | 3 | 9 |

| Floating population | Second home owners Home rentals (long-term tourists) Tourists |

3 2 1 |

4 3 5 |

|

| Civil society | Community organisations (local) | 6 | 8 | |

| Community organisations (national / subnational) | 7 | 5 | ||

| Community organisations (international) | 7 | 5 | ||

| NGOs | 7 | 8 | ||

| Academia | Polytechnic of Leiria | 8 | 9 | |

Source: own work.

In addition, the scoring results are shown in the graph and categorised into four groups where each category is represented with a colour. The colour red is used for representing the stakeholders in Investors category, blue for the Government, yellow for Inhabitants, and green for the Civil society category in the matrix.

Most of the identified stakeholders are located on the Manage Closely group, where the stakeholders in the Government category (blue) take the highest scores for both interest and power (Fig. 2). The rest of the stakeholders are mostly located in the Keep Informed group, where the stakeholders in the Inhabitants category (yellow) score the highest interest with the lowest power.

Results of the matrix indicated that Inhabitants and the Government are the key stakeholders for the case study and proposed solutions. Therefore, a broader analysis of these key stakeholders showed that the power and interest scores also vary between these categories. As the result of the analysis, permanent residents from the Inhabitants category and the municipality from the Government category were identified as the final key stakeholders. Lastly, the analysis showed that although these two groups share a similar interest in the proposed project, there is a significant gap in their powers.

Fig. 2. Stakeholder analysis matrix

Source: own work.

A stakeholder analysis showed that focusing on the power dynamics between key stakeholders is crucial for the proposed solution, and, therefore, the municipality, as the most powerful key stakeholder, is suggested to assume the responsibility for the implementation of the participation process to overcome the current conflicts between the stakeholders. Furthermore, the implementation of the participation process as the main strategy in the local government agenda to diversify the power share is seen as the key solution. To understand the benefits and possible consequences of this strategy for the municipality, the SWOT analysis method has been used.

Table 2. SWOT analysis of the participation process for municipality

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|

|

|

| Opportunities | Threats |

|

|

Source: own work.

According to the analysis, there are various strengths in taking responsibility for leading an effective participation process. Firstly, it is a good way to show that the elected officials care for citizens. It is an indicator of democratic strategic decision-making and can be used as a tool to predict conflicts between stakeholders. It is a useful way for involving different perspectives. Lastly, it is a powerful tool for building trust between the authorities and citizens if the process also involves transparency.

However, there are also multiple weaknesses. It is a complex organisation as the number of actors and the ideas that need to be negotiated increase. Therefore, the process requires more resources such as time and funding, and the success of the participation process depends on the willingness of the municipality to share its power.

There are also some attractive opportunities for the municipality in assuming the responsibility for the participation process. It has the potential to affect the prestige of the municipality in a positive way and lead to it becoming a reference municipality in Portugal. Therefore, the opportunities for funding from the European Union may increase, and it can be used as a means of implementing social sustainability for the future of the area.

Lastly, there are also threats that can be analysed, namely the challenges of changing the current strategies which are long-term documents and the risk of it being used by the opposition to reduce the political support for the local government.

The SWOT analysis has indicated that municipalities claiming to implement the participation process in urban planning will not benefit their communities but also use their own success in the governing process.

The stakeholder consultation revealed that the most prominent issue had been the disconnect from the planning and implementation processes. Stakeholders spoke of the municipality being absent from public discussion and having no space or forum to negotiate or discuss the plan. Considering these issues, we have made the following recommendations addressing the municipality:

Fig. 3. A proposed form of invitation to public consultations

Source: own work.

After analysing all the problems that occur in the area studied and developing some recommendations, we can conclude that participation will play an important role in solving many problems. Authorities must take steps to unite the entire community without excluding anyone. The recommendations are intended for the authorities because their role is to create a space for residents to freely exchange ideas. They also need to encourage people to become more interested in the surrounding space; therefore, we propose to place temporary installations that will spark public discussion about the changes.

Acknowledgments. The authors would like to thank Sara Bonini Baraldi from Politecnico di Torino, and Denis Cerić from the S. Leszczycki Institute of Geography and Spatial Organization, Polish Academy of Sciences for their helpful scientific remarks during the study visit to the research area. We thank Katarzyna Leśniewska-Napierała for her technical help in preparing this report during the publishing process.

BRYSON, J. (2004), ‘What to do when Stakeholders matter’, Public Management Review, 6 (1), pp. 21–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719030410001675722

CARDI (2012), 10 guidelines for writing policy recommendations, Centre for Ageing Research and Development in Ireland.

CROWE, S., CRESSWELL, K., ROBERTSON, A., HUBY, G., AVERY, A., and SHEIKH, A. (2011), ‘The case study approach’, BMC medical research methodology, 11 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-100

EDEN, G., SHARMA, S., ROY, D., JOSHI, A., NOCERA, J. A. and RANGASWAMY, N. (2019), ‘Field trip as method: a rapid fieldwork approach’, [in] Proceedings of the 10th Indian Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, New York: Association for Computing Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/3364183.3364188

ERDIAW-KWASIE, M. O., and BASSON, M. (2018), ‘Reimaging socio-spatial planning: Towards a synthesis between sense of place and social sustainability approaches’, Planning Theory, 17 (4), pp. 514–532. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1473095217736793

GUREL, E., and TAT, M. (2017), ‘SWOT Analysis: A Theoretical Review’, The Journal of International Social Research, 10 (51), pp. 994–1006. http://dx.doi.org/10.17719/jisr.2017.1832

JACKSON, G. and MORPETH, N. (1999), ‘Local Agenda 21 and Community Participation in Tourism Policy and Planning: Future or Fallacy’, Current Issues in Tourism, 2 (1), pp. 1–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683509908667841

PRETO, I., MCCALL, M. K., FREITAS, M. and DOURADO, L. (2016), ‘Participatory Mapping of the Geography of Risk: Risk Perceptions of Children and Adolescents in Two Portuguese Towns’, Children, Youth and Environments, 26 (1), pp. 85–110. https://doi.org/10.7721/chilyoutenvi.26.1.0085

WESTON, J. and WESTON, M. (2013), ‘Inclusion and Transparency in Planning Decision-Making: Planning Officer Reports to the Planning Committee’, Planning Practice & Research, 28 (2), 186–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2012.704736

JORGE, J. P., OLIVEIRA, V., SANTOS, L. L., VIANA, A. S. and MALHEIROS, C. (2022), ‘The Spatial Planning System in Portugal’, Theoretical Framework Report on European Spatial Planning of Tourism Destinations.

KAIKA, M. (2017), ‘Don’t call me resilient again!’: the New Urban Agenda as immunology … or … what happens when communities refuse to be vaccinated with «smart cities» and indicators’, Environment and Urbanization, 29 (1), pp. 89–102. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247816684763

KALLET, R. H. (2004), ‘How to Write the Methods Section of a Research Paper’, Respiratory Care, 49 (10), pp. 1229–1232.

NANCY, J. L. (1991), ‘The inoperative community’, [in] CONNOR, P. (ed.), Theory and history of literature, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 1–42.

VAN CAUWENBERGH, N., CIURÓ, A. B., and AHLERS, R. (2018), ‘Participatory processes and support tools for planning in complex dynamic environments: a case study on web-GIS based participatory water resources planning in Almeria, Spain’, Ecology and Society, 23 (2). https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-09987-230202