Abstract. The cohesion policy of the EU plays a key role in overcoming territorial disparities. The emergence of the policy was accompanied by a debate on a place-neutral or place-based approach. In the case of Hungary, the first fully implemented programming period of 2007−2013 and the still ongoing 2014−2020 period provide a good tool for comparison. Overall, the aim of the research was to provide an in-depth look into the change of territorial patterns of EU-funding distribution, on the example of the Baranya county, being part of one of the 20 least developed regions of the EU; how territorial patterns of EU funding changed between the two periods and how the county-level territorial objectives were reflected in the funding patters.

The introduction of the paper provides a review of relevant literature on EU cohesion policy, then the selection of the Baranya county as a case study is justified. The following part shortly presents the framework of regional development in Hungary, highlighting the relevant documents for the case study county. The presentation of the empirical study is divided into two parts. First, as qualitative research perceptions of the stakeholders of the key levels of regional policy decision-making are analysed. Second, a quantitative analysis of the territorial funding patterns of the two periods is presented, in light of established territorial objectives.

Key words: multi-level governance, cohesion policy, place-based policy, peripheral areas.

Decreasing regional disparities as an objective dates back to the Rome Treaty, as a precondition for an effective common market. The establishment of the European Regional Development Fund in 1975 was a major step in the European integration process. The European regional policy has become a synonym for the European social model: for the sake of the common market lagging regions should be helped to catch up, and promote their competitiveness (Streitenberger, 2013), which also contributed to creating legitimacy for the integration process (Manzella and Mendez, 2009). Although the policy is referred to as “regional,” the allocation of funding is made, in fact, at the national level, during negotiations with the European Commission, in coherence with EU level objectives.

Individual periods of the policy show a particular evolution process: while the policy moves towards complexity, tendencies of simplification and standardisation are also apparent. EU regional policy has been assessed from several aspects: numerous scholars examine its efficiency, providing mixed results. Although convergence is detected at the EU level among countries, it often follows a divergence between regions within a country (Bachtler and Gorzelak, 2007; Butkus and Matuzevičiūtė, 2016; EC, 2022). During its evolution, regional policy has become the second largest policy area in terms of funding provided, the majority of financial sources of which go to Objective 1 regions, those being below the 75% threshold in terms of GDP per capita compared to the EU average. Concerning the objective of reducing territorial disparities, some scholars claim that the policy in its current form is more an income support or redistribution mechanism than a tool of long-term sustainable development; it is not sufficient to offset market forces, rather prevent or slow down divergence tendencies (Rodríguez-Pose and Fratesi, 2004). As they represent a large share of projects that receive funding, large transport infrastructure projects – despite a positive impact on accessibility – generate an unfavourable macro-regional situation (Ecorys, 2006), while direct SME support schemes may negatively impact competitiveness, in the form of conservation of existing technologies (Varga, 2016) and generation of inflation (Varga and in’t Veld, 2010).

Reforms of the cohesion policy have attempted to target both cohesion and competitiveness, with changing focus. The strengthening of the sub-national level and the primacy of regional focus was challenged by several reforms and debates. The Lisbon Strategy (2006) put faster growth, innovation and employment into focus (Bachtler and Gorzelak, 2007), requesting Member States to earmark funding for the achievement of Lisbon goals (Mendez, 2011). This was in line with the approach of the World Development Report (2009) of the World Bank that promoted the focus on major centres, expecting cohesion to be achieved by a spill-over effect (Barca et al., 2012). The Barca Report in 2009, as an alternative, advocated the place-based approach, deriving from the European spatial structure (Barca et al., 2012). The document, along with the necessity of territorial strategies and territorially owned public goods, highlights the importance of appropriate institutions, and multi-level governance, which is a composition of endogen and exogen resources (Barca, 2009). The EU 2020 strategy once again put a stronger accent on the EU-level coordination of reaching key targets (smart, sustainable and inclusive growth – EC, 2010), defined also at the national and regional levels, which was the key guiding principle of the regulation for the 2014−2020 programming period of the cohesion policy.

In research on territorial cohesion, macro-level issues prevail. Studies focusing on institutions often highlight the quality of governance and its role in absorption (Mendez and Bachtler, 2022), including some analyses at the regional level (Fazekas and Czibik, 2021), and the connection between absorption and political changes (Hagemann, 2019). These analyses were made with nationally available indicators and absorption figures, however, regional analyses need local-level absorption data and qualitative research, i.e., interviews with stakeholders positioned outside the programme management bodies, which are done only sporadically, usually as case studies.

Hungary has been a member of the EU since 2004 and, therefore, one completed and one nearly finished programming periods are available for analysis. The 2007−2013 programming period was the first to be implemented completely after the accession. Those seven years were influenced by turbulent institutional changes: a centralised programme management system was established and accompanied by a structure of sectoral and regional (seven NUTS 2) operational programmes. Subsequent public administration and local government reforms led to some re-design of the programmes, resulting in the dominance of centrally made decisions and a decreased role of regional institutions. The 2014−2020 period, unlike the previous one, was prepared and implemented with a relatively stable political and institutional background, however, it was much more heavily influenced by the more uniform, EU2020-oriented regulation background. As programmes of the period must be closed by the end of 2023, some projects are still under implementation, final conclusions cannot be drawn. However, a comparison of the two periods from place-based policy point of view is possible, highlighting coherence and conflicts between programme-level objectives and implementation practices.

After the introduction and justification of the selection of the Baranya county as the case study, major stages of regional development policy in Hungary are presented, with special attention applied to the case study region. Research questions and the applied methodology is described in brief, which is followed by details of the qualitative analysis. The section about the quantitative analysis is introduced with a detailed methodological description, which is followed by a presentation of the results. The paper is closed with a conclusion that highlights the relevance of the results and outcome of some parallel research on the investigated topic.

Baranya has been in a particular position within Hungary since the political and economic change of the 1990s. Although it is located in the more developed “west” of Hungary, it has been one of the 20 least developed NUTS 2 regions of the EU (South Transdanubia or Dél-Dunántúl), being currently at 32% of the EU average in terms of GDP per capita.

Unlike the north-eastern counties of Hungary where the transitional crisis of the 1990s hit particularly strongly, Baranya showed an average level of development within Hungary in the 90s, without signs of severe economic or social crises. Despite its significant mining industry, the overall picture of the county’s economy showed a solid share of agriculture, a relatively low level of industry and an above-average service sector, which was only typical for the capital region of Hungary. While unemployment had been the main indicator of economic downturn in Hungary’s economy in the 1990s, Baranya was not critically affected by this phenomenon (Schwertner, 1994). Despite certain crisis tendencies of the 1990s, Pécs and Baranya seemed to be ready to open their economies (Faragó and Horváth, 1995), however, the war in the former Yugoslavia negatively affected them and made the county isolated. Baranya, in the end, failed to renew its industry through FDI (Nagy, 1995).

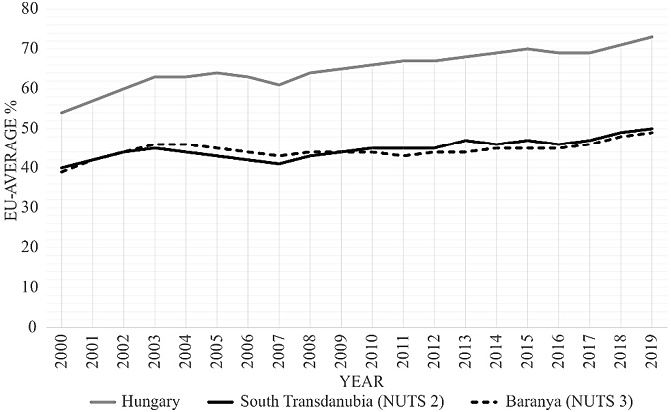

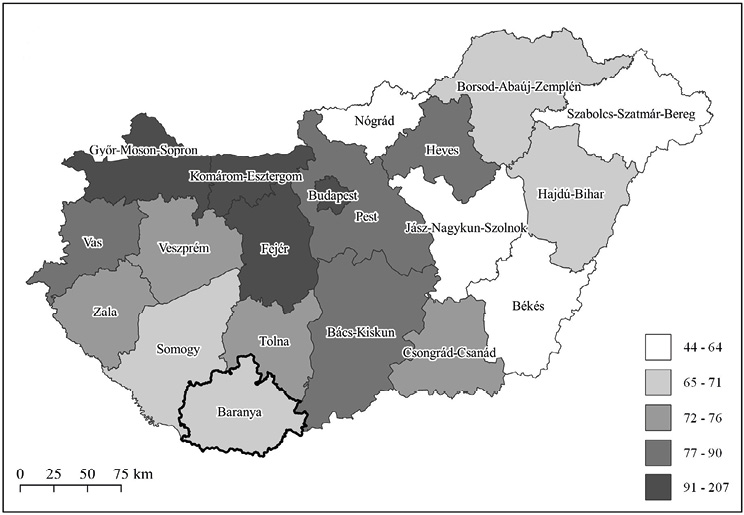

Baranya’s lagging in terms of GDP per capita started as early as in the 1990s. The economic upturn in the early 2000s showed signs of cohesion in Baranya as well. The economic crisis of 2007 hit the region somewhat less than Hungary in general, however, while at the national level one could observe a slow recovery process, in the case of Baranya it was rather a period of stagnation (Fig.1). Baranya currently is among the least developed counties in the western part of Hungary, and the country in general (Fig. 2).

The framework of regional development in Hungary was defined by the Act 1996: XXI on Regional Development and Spatial Planning, which used to be referred as a positive example of a newly established regional development institutional system since the end of the 1990s (Pálné Kovács, 2021). Although its main objective (reducing territorial disparities) was an integrated element throughout, it underwent several modifications, swings in terms of centralisation and decentralisation (Pálné Kovács and Mezei, 2016). Relevant development documents since 2000, regulated by this act, as well as by EU cohesion policy, are shown in Table 1.

Fig. 1. GDP per capita on current prices, as % of EU average

Source: Eurostat, own work.

Fig. 2. GDP per capita in percentage of national average, 2019 (%)

Source: own work based on Central Statistical Office of Hungary.

| Title of document | Type of document | Regulation |

|---|---|---|

| Regional Development Programme of Baranya County 2003 | county programme | Act on Regional Development and Spatial Planning |

| South Transdanubian Operational Programme (STOP) 2007−2013 | regional operational programme | EU cohesion policy – National Strategic Reference Framework 2007−2013 |

| Baranya County Regional Development Concept 2014−2020 | county concept | Act on Regional Development and Spatial Planning |

| Baranya County Regional Development Programme 2014−2020 | county programme | Act on Regional Development and Spatial Planning |

| Integrated Territorial Programme of Baranya County 2015−2020 | county integrated territorial programme | EU cohesion policy – Partnership Agreement |

The 2003 county development programme, designed in parallel with regional documents, rather focused on internal disparities, highlighting some institutional shortcomings as well (Pámer, 2021). The bottom-up approach of the document was considered as adequate to the role of the county at that time, which focused on small-scale local development interventions, mostly small settlements (Márton, 2009).

The 2007−2013 period, the first full programming period after Hungary’s EU accession, brought the emergence of the NUTS 2 regions. As part of the National Strategic Reference Framework for 2007−2013 each seven region got their own regional operational programme, including South Transdanubia (STOP). This resulted a significant shift from county to region in the institutional system as well. This meant in that period that no county level document was adopted in Baranya. The preparation of the STOP had been a long-running and thorough job, including the preparation of several sectoral strategic development plans and the creation of a wide regional stakeholder network (Márton, 2004). The document, again, focused on internal disparities, the main objective of the STOP was to halt further decline. The programme was designed with sectoral priorities, however, each priority applied certain place-based elements. The programme promoted the strengthening of small towns as the backbone of the settlement network, for the sake of concentrating services. Regionalisation of regional development brought the strengthening of the role of regional development councils and regional development agencies went through significant organisational development (Józsa, 2018). Regional development councils had the role of expressing their support for projects, however, the final decision was made at the national level. The agencies were involved in programming, the preparation of action plans, the evaluation of applications, preparation for decision-making, which resulted in an institution dominated by skilled professionals and unavoidable in case of regional development related initiatives in the region.

The 2011 amendment of the Act on Regional Development and Spatial Planning seized the regional development councils, the coordination of regional development was delegated to the counties, which seemed to be a rational step towards simplification and democratisation: decision-making on funding schemes was delegated from state-dominated regional development councils to locally elected counties. While the counties, which prior to the reform had been responsible for education, health and social care institutions, got regional development coordination as their only responsibility. Despite rhetorical decentralisation, the reform, in the end, led to a significant weakening of the county’s competences and human resources (Pámer, 2021).

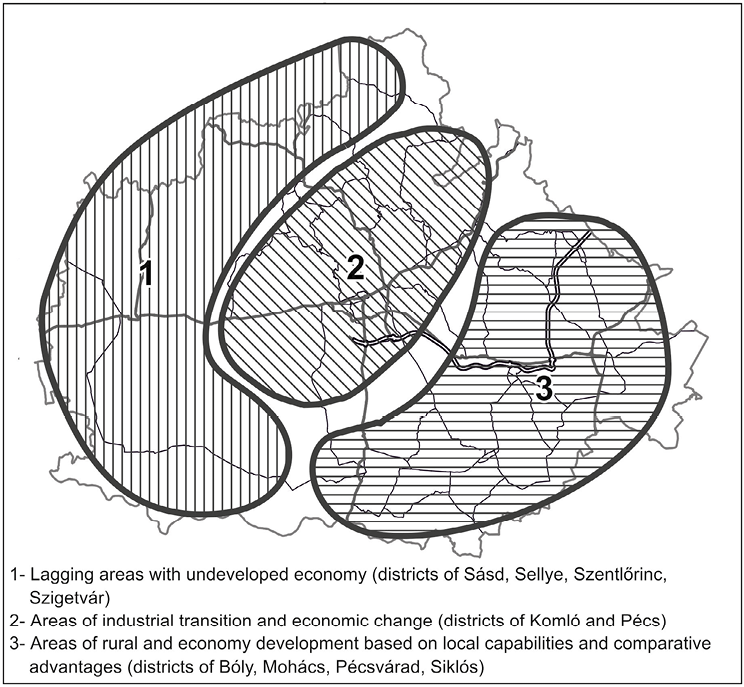

The Baranya development concept and programme for the 2014−2020 period was prepared by the county administration. The applied methodology was centrally defined, laying down the process of involvement and partnership in the designing phase. Unlike the two previous documents, the 2014−2020 concept aimed to position the county within Hungary as well. The document defined three territorial objectives: lagging areas, transitional areas, and rural and economy development areas (Fig. 3). This division reflected the long-lasting internal division of the county: the county’s core area (Pécs) and its north-eastern periphery (Komló) still suffered from the consequences of the unsuccessful economic recovery and incomplete re-industrialisation. The eastern and south-eastern peripheries of the county – with Mohács being the largest town – were more successful in the economic transition, due to relatively active SMEs. This area has also a better physical position, close to the main transport axis. As an opposite, the western periphery (around Szigetvár) lacks any particular perspective, not being close enough to the county’s core area or transport routes.

The Integrated Territorial Programme (ITP) of the Baranya County provided the link between the county-level development objectives and the nationally implemented ERDF-funded Territorial and Settlement Development Operational Programme (TSDOP) for the 2014−2020 period. The ITP, as a tool, is not to be confused with the Integrated Territorial Investment (ITI) defined by Common Provisions Regulation (CPR) of EU cohesion policy. While the ITI focuses on urban areas and finances interventions from multiple programmes with a strong territorial focus, the Hungary ITPs are established at the county level, dividing the county-ranked cities and the rural areas. Thus, besides the Baranya ITP, a particular ITP has been developed for the county-ranked city of Pécs as well. The Baranya ITP, unlike the urban-focused STOP, emphasised the importance of developing the lagging and peripheral areas.

Fig. 3. Territorial development objectives in Baranya county, according to the Baranya County Concept 2014–2020

Source: Baranya (2014, 21), own work.

In terms of decision-making, the place-based approach was applied through the co-decision system in terms of project selection. The “territorial project selection system” means the definition of county-specific evaluation criteria (coherence with the county concept and programme) for each centrally designed call, as well as joint decision-making on project selection between the state-led management of the TSDOP and the county concerned. In this regard, although the TSDOP is a more centralised programme in its design, in terms of decision-making it happened to be more decentralised than the regionally designed and centrally implemented STOP.

The overall aim of the research was to provide an in-depth insight into the change of territorial patterns of EU-funding distribution, on the example of the lagging region of the Baranya county. The presented research was divided into two parts. The qualitative research, on the one hand, aims at measuring the perception of the stakeholders at the relevant level of decision-making in regional development and its changing tendencies. The quantitative analyses, on the other, attempts to answer the following two questions:

In order to measure how the delegation of decision-making on regional development to the county level was perceived among stakeholders, on the sample of the Baranya county a questionnaire survey was conducted. The survey covered a total of 233 people from 66 local units. The involved people were not essentially key decision-makers; they included various segments of the local elite (former mayors, key persons of administration, entrepreneurs, education staff, etc.). Although not territorially representative, the survey covered all ten district centre towns, all four further towns, 22 municipalities with a population above 1,000 and 31 small municipalities up to 1,000 inhabitants. Pécs, as the county’s seat, was not included in the survey, as administratively the county does not include its seat. The questionnaire survey was followed by a serial of semi-structured in-depth interviews.

As for the key level of decision-making, a majority of the respondents considered the local level as the most important one, followed by the national level, which was particularly visible in the case of municipalities above 1,000 inhabitants. Despite re-introducing the county as regional development policy-maker, its importance has been proven as surprisingly low, particularly in towns. The district was also re-introduced in 2012, only for state administration purposes, without any regional development relevance, therefore, its low level of importance is not a surprise (Table 2).

| Type of settlement | Most important level of decision making (share of responses) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| local | district | county | national | EU | total | |

| district centres | 0.328 | 0.156 | 0.078 | 0.188 | 0.250 | 1.000 |

| other towns | 0.500 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.250 | 0.250 | 1.000 |

| municipalities above 1,000 | 0.311 | 0.095 | 0.122 | 0.338 | 0.135 | 1.000 |

| other municipalities | 0.351 | 0.052 | 0.195 | 0.260 | 0.143 | 1.000 |

| total | 0.339 | 0.093 | 0.128 | 0.264 | 0.176 | 1.000 |

A different question assessed the tendency of the change in the importance in the case of different territorial levels. Answers were provided in the interval of [-2; 2] as: significantly decreased, slightly decreased, did not change, slightly increased, and significantly increased. The most significant increase was measured at the local level, followed by the influence of the national level. The two intermediary levels were not perceived with growing importance (Table 3).

| Type of settlement | Change in the importance of decision making (weighted perception in the interval [-2; 2]) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| local | district | county | national | |

| district centres | 0.966 | 0.250 | 0.291 | 0.875 |

| other towns | 1.333 | 0.000 | 0.917 | 1.583 |

| municipalities above 1,000 | 1.110 | 0.200 | 0.444 | 0.718 |

| other municipalities | 0.900 | 0.379 | 0.418 | 0.657 |

| total | 1.014 | 0.264 | 0.422 | 0.791 |

Although the survey showed a clear preference towards the local level, the in-depth interviews revealed that a majority of the respondents had a clear experience about the increasing role of the state, even in the case of the smallest municipalities. The county level was perceived dominantly in the small villages. Members of parliament were perceived as players with significant growth of importance nearly by all respondents, however, judgement on their role varied. Some opinion leaders said they were the key players in decision-making, their involvement in each development initiative was a must. Others said their activities were limited to raising awareness about government policies, collecting and distributing information, and conducting political campaigns. Respondents oriented towards the nationally ruling Fidesz party were more eager to treat members of the parliament as being more important than local actors who identify themselves as opposition or independent (Pámer, 2022).

The analysis of the distribution of EU cohesion policy funding was done on the basis of a database provided by the Prime Minister’s Office of Hungary, responsible for the coordination of EU cohesion policy at the state level. The database was compiled at the municipality (LAU 2) level, thereof the data of the municipalities of Baranya were used. The data shows EU cohesion policy spending in Hungarian forints, without the beneficiaries’ own contribution, which may be used for comparison.

Data analysis took place in two dimensions and at three levels:

Intensity of funding (F) in the case of the analysed level (district, settlement, group of districts) was measured as the deviation from the average per capita funding in Baranya. In terms of the population, the data provided by the Central Statistical Office of Hungary as of 1 January 2019 was taken into consideration.

| F = | funding per capita of the assessed territory – funding per capita on county level |

| funding per capita on county level |

For measuring the concentration of funding in centres, a weighted core-periphery indicator was calculated from the settlement-level data: distribution rates by type of settlement were weighted then summed, as follows:

The weighted core-periphery indicator is in the range of [–1; +1], i.e., 1 if the funding was entirely spent by beneficiaries from district centres, while –1 if the funding was completely absorbed by municipalities not having more inhabitants than 1,000.

This simple method was developed for this analysis. The applied settlement type categories were defined with a functional approach. District centre towns obviously stand out in terms of function within their districts. Further (non-district-centre) towns have a considerably weaker role, however, they are usually towns with special characteristics (tourism, commuting settlements around Pécs) that may be either a strength or a weakness in terms of the accumulation of funding. Grouping municipalities from the functional point of view was complicated. The existing category of “large municipalities” includes only three municipalities in Baranya, which, in the case of a county of very small municipalities, does not represent all low-level area centres. Therefore, the population limit of 1,000 people was used, as – in the rural Baranya which is dominated by very small municipalities – all those above 1,000 play some kind of central roles in their area. There are some 26 of such municipalities in the county, while the number of ‘other municipalities’ is 261.

Funding absorbed in 2007−2013 and its distribution between Pécs and the countryside is listed in Table 4. In the case of the regional development focused STOP majority of the funding was provided outside Pécs, while in case of the economy development oriented EDOP – which primarily focused on SMEs – more than 50% of the financial resources landed in the county centre. Considering the weighted core-periphery indicator, STOP showed very low concentration, while EDOP showed a very high one, meaning that successful SME projects concentrated in the central settlements.

| Operational programme | Total payment made in Baranya (million HUF) | Spent in Pécs (%) | Spent outside Pécs (%) | Weighted core-periphery indicator |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| South Transdanubia (STOP) | 117,124 | 43.65 | 56.35 | 0.032 |

| Economy development (EDOP) | 35,003 | 56.21 | 43.79 | 0.521 |

| Total mainstream EU funding | 305,658 | 58.41 | 41.59 | 0.171 |

In the case of the 2014−2020 period the regional development focused TSDOP was, on the one hand, significantly smaller than STOP in the previous period, showing that territorial cohesion was somewhat less emphasised in the second period. On the other, spending from the SME-oriented EDIOP was doubled in Baranya, compared to EDOP in the previous period. Distribution of the funding of these two programmes between the county seat and the rest of Baranya was similar: TSDOP preferred more the countryside, while EDIOP rather concentrated in Pécs. The weighted core-periphery indicator shows a significant change: regional development funding was more concentrated in centres than before, while SME development support became less concentrated than in 2007−2013 (Table 5).

| Operational programme | Total payment made in Baranya (million HUF) | Spent in Pécs (%) | Spent outside Pécs (%) | Weighted core-periphery indicator |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Territorial and Settlement Development (TSDOP) | 74,454 | 44.25 | 55.58 | 0.379 |

| Economy Development and Innovation (EDIOP) | 77,869 | 57.36 | 42.64 | 0.187 |

| Total mainstream EU funding | 257,612 | 46.41 | 53.39 | 0.205 |

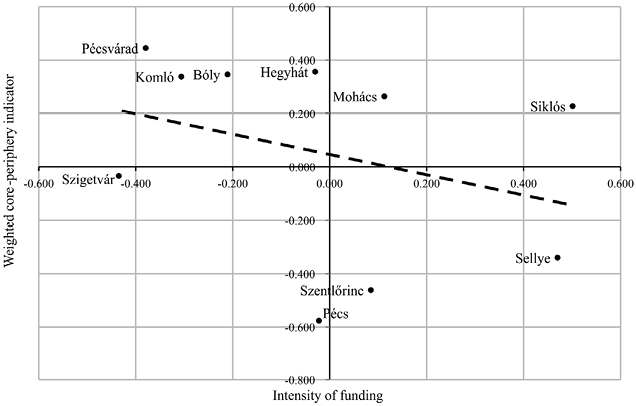

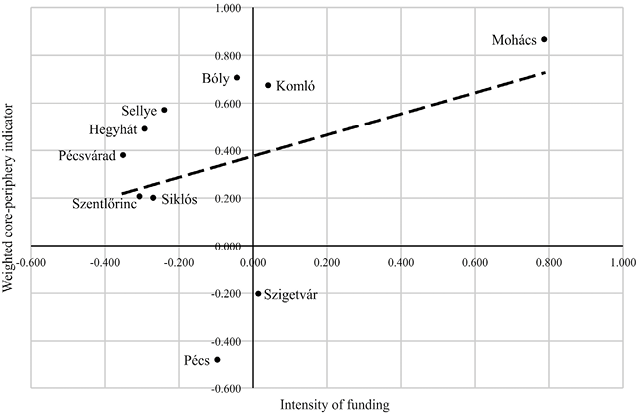

For the sake of a more in-depth comparison of the two territorial cohesion programmes, a scatterplot of the intensity of funding and the weighted core-periphery indicator was performed for the ten districts. As Fig. 4 shows in the 2007−2013 period, districts with relatively low per capita funding showed higher concentrations. The Szigetvár district, as an exception, was relatively poorly funded, also, most of the funding landed in its rural area. The town of Szigetvár proved to be a weak centre from the regional development point of view. In the case of districts with relatively high per capita funding, the weighted core-periphery indicator was lower, as the trendline shows.

The general approach of the STOP, i.e., territorial cohesion should be promoted through the area centres, was more or less fulfilled, as in the districts with lower funding the centres were more preferred, while in better absorbing districts also the rural areas could benefit.

The 2014−2020 period provides a completely different picture, showcasing the growth of absorption gaps between individual districts. Most of the districts were funded below average. Although Szigetvár is now funded around the average, it, again, showed a rather low concentration, maintaining its weak position as a district centre. Besides the gap between the poorly and the average-funded districts, an even larger gap is visible between the extreme standout of Mohács and all the rest (Fig. 5). Although the TSDOP advocated for a preference of peripheral areas, a concentration of funding has grown in the centres.

Fig. 4. Position of districts of Baranya county in terms of absorption of STOP funding per capita and the weighted core-periphery coefficient

Source: Prime Minister’s Office, own work.

Fig. 5. Position of districts of Baranya county in terms of absorption of TSDOP funding per capita and the weighted core-periphery coefficient

Source: Prime Minister’s Office, own work.

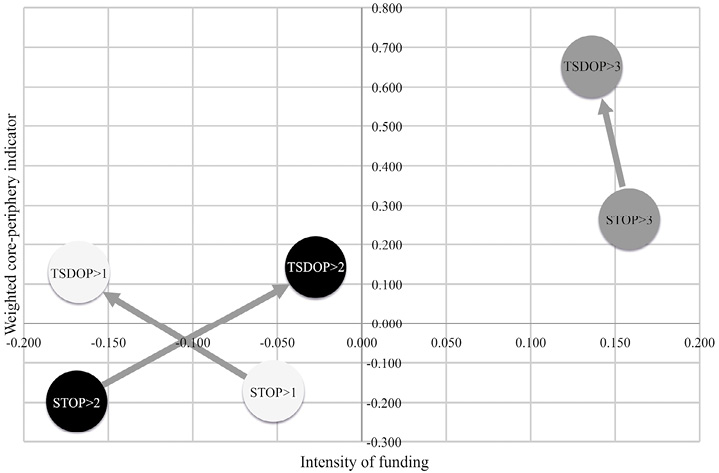

The comparison of funding patterns in areas according to the territorial objectives defined in the county development concept for the 2014−2020 period shows that lagging areas with undeveloped economies (1) were relatively low funded in both periods, their position even worsened in 2014−2020: less funding with higher concentration. In the case of the areas of industrial transition and economic change (2) more funding was provided in the second period, also with growing concentration. These figures resulted from the generous funding of the industrial town of Komló. In both periods most funding was accumulated in the areas of rural and economy development (3), however, concentration was also growing in this area (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Position of the different area categories in terms of intensity of funding and the weighted core-periphery indicator, in case of STOP (2007–2013) and TSDOP (2014–2020)

Source: Prime Minister’s Office, own work.

On the basis of the presented regional analysis, several conclusions can be drawn. In spite of the institutional change, the county is barely recognised as decision-making body. Instead, a growing importance of the state, through the emerging role of the members of parliament, is experienced.

Concerning funding patterns, regional development represented a significantly higher share in the first period than in the second one, meaning the county was left with much less funding to decide on since 2014 than the region did before. Funding from other programmes could not compensate for this decrease, resulting in a generally worsening position for Baranya. Although STOP in the first period promoted area centres as agents of territorial cohesion, funding was relatively balanced between the centres and the periphery. In the second period, when the TSDOP targeted the lagging and rural areas more, funding rather concentrated in the relatively developed districts and in the area centres. Thus, the rural shift of TSDOP did not occur, the biggest beneficiaries were the largest urban settlements (Komló and Mohács, in particular). It means the 2007−2013 programme better served the territorial objectives defined for the 2014−2020 period than the programme for which it had been developed.

A parallel related study revealed that in the 2014−2020 period at the national level more EU funding was spent in the less developed districts than in 2007−2013, while funding to more developed districts slightly decreased (Finta, 2022). It is important to note that the largest number of settlements – mostly those below 1,000 inhabitants – that did not receive funding from any of the two programmes, were in the Baranya county (Finta, 2022). These results highlight the importance of regional and subregional research, in order to test whether a more territorially balanced or a more concentrated approach may be more beneficial.

In general, the growing concentration of EU cohesion policy benefits in some selected urban areas that lead to a greater urban-rural divide. The decrease in access and visibility of EU funding (and a less visible EU in general) in the rural areas will need stronger governmental intervention, in the form of tailored and place-based regional schemes that, at the current stage, do not exist in Hungary. This would not only require a more intensive involvement of the state, but strong regional institutions as well.

Acknowledgements. Project no. 132294 was implemented with the support of the National Fund for Research, Development and Innovation of Hungary, funded under the K-19 funding programme.

BACHTLER, J. and GORZELAK, G. (2007), ‘Reforming EU Cohesion Policy’, Policy Studies, 28 (4), pp. 309−326. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442870701640682

Baranya (2014), Baranya Megyei Területfejlesztési Koncepció. Javaslattételi fázis [Baranya County Regional Development Concept. Proposal-making phase], https://docplayer.hu/11934816-Baranya-megyei-teruletfejlesztesi-koncepcio.html [accessed on: 07.09.2020].

BARCA, F. (2009), An Agenda for a Reformed Cohesion Policy – A place-based approach to meeting European Union challenges and expectations, independent report prepared at the request of Danuta Hübner, Commissioner for Regional Policy, http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/archive/policy/future/pdf/report_barca_v0306.pdf [accessed on: 05.07.2018].

BARCA, F., MCCANN, P. and RODRÍGUEZ-POSE, A. (2012), ‘The case for regional development intervention: place-based versus place-neutral approaches’, Journal of Regional Science, 52 (1), pp. 134−152. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9787.2011.00756.x

BUTKUS, M. and MATUZEVIČIŪTĖ, K. (2016), ‘Evaluation of EU Cohesion Policy Impact on Regional Convergence: Do Culture Differences Matter?’, Economics and Culture, 13 (01). https://doi.org/10.1515/jec-2016-0005

EC (2010), Communication from the Commission – Europe 2020 – A European strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, European Commission, Brussels 3.3.2010, https://ec.europa.eu/eu2020/pdf/COMPLET%20EN%20BARROSO%20%20%20007%20-%20Europe%202020%20-%20EN%20version.pdf [accessed on: 23.01.2023].

EC (2022), Cohesion in Europe towards 2050 – Eighth report on economic, social and territorial cohesion, Publications Office of the European Union, https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/information/cohesion-report/ [accessed on: 16.03.2022].

Ecorys (2006), Strategic Evaluation on Transport Investment Priorities under Structural and Cohesion Funds for the Programming Period 2007-13, Synthesis Report to the European Commission. ECORYS Nederland NV, Rotterdam. https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/docgener/evaluation/pdf/strategic_trans.pdf [accessed on: 28.04.2022].

FARAGÓ, L. and HORVÁTH, Gy. (1995), ‘A Dél-Dunántúl területfejlesztési koncepciójának alapelemei’ [Elements of the South Transdanubian regional development concept], Tér és Társadalom, 9 (3–4), pp. 47–77. https://doi.org/10.17649/TET.9.3-4.336

FAZEKAS, M. and CZIBIK, Á. (٢٠٢١), ‘Measuring regional quality of government: the public spending quality index based on government contracting data’, Regional Studies, 55 (8), pp. 1459−1472. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2021.1902975

FINTA, I. (2022), ‘Az Európai Unió átfogó fejlesztéspolitikai alapelveinek fejlődési trendjei és azok érvényesülése Magyarországon’ [Development trends of EU regional policy principles and their realisation in Hungary], Új Magyar Közigazgatás, 2, pp. 1–19.

HAGEMANN, C. (2019), ‘How politics matters for EU funds’ absorption problems – a fuzzy-set analysis’, Journal of European Public Policy, 26 (2), pp. 188−206. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2017.1398774

JÓZSA, V. (2018), ‘Quo vadis regionalizmus? Egy eszme- és értékrendszer tovább élése a szakemberek közvetítésével’ [Quo vadis regionalism? The subsistence of a conceptual and value systemthrough the professionals], Tér és Társadalom, 3, pp. 96−112. https://doi.org/10.17649/TET.32.3.3064

MANZELLA, G. P. and MENDEZ, C. (2009), The turning points of EU Cohesion policy, http://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/archive/policy/future/pdf/8_manzella_final-formatted.pdf [accessed on: 02.07.2018].

MENDEZ, C. (2011), ‘The Lisbonization of EU Cohesion Policy: A Successful Case of Experimentalist Governance’, European Planning Studies, 19 (3), pp. 519−537. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2011.548368

MÁRTON, Gy. (2004), ‘Az Első Magyar Nemzeti Fejlesztési Terv tervezési folyamatának tapasztalatai regionális szemszögből’ [Experiences of the first Hungarian National Development Plan from regional point of view], Falu Város Régió, 9, pp. 32−45.

MÁRTON, Gy. (2009), ‘Gondolatok a hazai decentralizált fejlesztési források felhasználásának megújításáról’ [Thoughts about the renewal of absorption of domestic decentralised development funds], Falu Város Régió, 3, pp. 23−27.

MENDEZ, C. and BACHTLER, J. (2022), ‘The quality of government and administrative performance: explaining Cohesion Policy compliance, absorption and achievements across EU regions’, Regional Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2022.2083593

NAGY, G. (1995), ‘A külföldi tőke szerepe és térbeli terjedése Magyarországon’ [The role and spatial spreading of foreign capital in Hungary], Tér és Társadalom, 9 (1–2), pp. 55–82. https://doi.org/10.17649/TET.9.1-2.327

PÁLNÉ KOVÁCS, I. (2021), ‘A centralizáció és a perifériák fejlődési esélyei’ [Centralization and the development potential of peripheral areas], Tér és Társadalom, 35. évf., 4. szám, 2021. http://doi.org/10.17649/TET.35.4.3372

PÁLNÉ KOVÁCS, I. and MEZEI, C. (2016), ‘Regionális politikai és területi kormányzási ciklusok Közép- és Kelet-Európában’ [Cycles of regional policy and territorial governance in Central and Eastern Europe], Tér és Társadalom, 4, pp. 54−70. https://doi.org/10.17649/TET.30.4.2810

PÁMER, Z. (2021), ‘A területi kormányzás és a területi integráció vizsgálata Baranya megye fejlesztési dokumentumaiban az uniós csatlakozástól napjainkig’ [Overview of territorial governance and territorial integration in development documents of Baranya county, since the EU accession to date], Tér és Társadalom, 35 (3). https://doi.org/10.17649/TET.35.3.3337

PÁMER, Z. (2022), ‘Az egyes területi szintek jelentőségének változása a magyar területfejlesztési politikában, Baranya megye példáján’ [Change of significance of the single territorial levels in Hungarian regional development policy on the example of Baranya county], Comitatus, 2022. különszám, pp. 69−81.

RODRÍGUEZ-POSE, A. and FRATESI, U. (2004), ‘Between Development and Social Policies: The Impact of European Structural Funds in Objective 1 Regions’, Regional Studies, 38 (1), pp. 97−113. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400310001632226

SCHWERTNER, J. (1994), ‘Parázsló munkaerőpiac’ [A Changing Labour Market], Tér és Társadalom, 8 (1-2), pp. 59−82. https://doi.org/10.17649/TET.8.1-2.296

STREITENBERGER, W. (2013), ‘The new EU regional policy: fostering research and innovation in Europe’, [in:] PÁLNÉ KOVÁCS, I., SCOTT, J. and GÁL, Z. (eds.), Territorial Cohesion in Europe – For the 70th anniversary of the Transdanubian Research Institute, Institute for Regional Studies, Centre for Economic and Regional Studies, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Pécs, pp. 36−45.

VARGA, A. (2016), Regionális fejlesztéspolitikai hatáselemzés [Impact assessment of regional development policy], Akadémiai Kiadó. https://doi.org/10.1556/9789634540151

VARGA, J. and in’t VELD, J. (2010), The Potential Impact of EU Cohesion Policy Spending in the 2007–2013 Programming Period: A Model-Based Analysis, European Commission, Economic and Financial Affairs.