Abstract. Tourism may be an important leverage for local development. At the same time, it may trigger unwanted effects, ranging from the congestion of services and infrastructures to the progressive deterioration of the assets that they plan to valorise. The article sheds light on this tension, discussing the multiple implications that increasing tourism fluxes generate in the vineyard landscape of Langhe-Roero and Monferrato, included in the UNESCO World Heritage List since 2014. The case study highlights the need to coordinate and enhance coherence among the existing planning and management instruments, towards the consolidation of a multi-level integrated territorial governance framework aimed at the sustainable spatial planning of tourism in the area.

Key words: UNESCO, wine regions, landscape planning, spatial planning, sustainable tourism.

Tourism is often identified as the cornerstone of territorial development strategies by local and regional authorities, motivated by the added value that increasing flows of visitors may bring to local economies. At the same time, tourism activities may trigger unwanted effects, ranging from the congestion of services and infrastructures to the progressive deterioration of the assets from which they extract value. These challenges have recently gained prominence in the international arena, also as a consequence of the high level of uncertainty raised by climate change and the COVID-19 pandemic (Dodds and Butler, 2019; Cotella and Vitale Brovarone, 2021a, 2021b). Among the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) launched by the 2030 Global Agenda (UN, 2015), SDG 11 aiming at “Building sustainable and resilient cities and communities” devotes particular attention to inclusive and sustainable urbanisation (Target 11.3), the strengthening of cultural and natural heritage (Target 11.4), the reduction of disaster-related human and economic losses (11.5), environmental quality (11.6 and 11.7), and regional development and climate change adaptation (11.a and 11.b) (Berisha et al., 2022). Similarly, the European Union’s (EU) “Green Deal” and the so-called “New European Bauhaus” support sustainability, aesthetic, and inclusion principles through integrated spatial planning and the implementation of cross-sectoral strategies that also include tourism (CEC, 2019).

While the main urban areas are better positioned to capitalise on the emerging development paradigms and the strategic and financial opportunities that they will bring (Evans et al., 2019), small and medium-sized cities and rural areas are only recently reaching out to these issues, due to their lesser engagement in knowledge exchange networks and a common perception as ‘idyllic locations’ that do not yet suffer from the negative impacts of overdevelopment (Rye 2006; Cotella and Vitale Brovarone, 2022).[1] However, accelerating globalisation has progressively also increased their visibility as tourism destination (Assumma and Ventura, 2014); while the more virtuous contexts have seized this opportunity to synergistically integrate tourism within multi-dimensional development trajectories, in various cases the implementation of quick-win enhancement strategies has led to the consolidation of “mono-functional seasonal showcases”, often disconnected from their spatial surroundings.

Overall, the development of a touristic offer that provides an outstanding experience to visitors without overexploiting the existing resources and assets or worsening the quality of life of residents remains a tangle that still needs to be unravelled (Adie et al., 2020; Bohac and Drapela, 2022). The conundrum is even more complex in relation to UNESCO Heritage sites (Di Giovine, 2008), where the cultural values, both tangibles and intangibles, that contribute to the uniqueness of a given context have to be valorised and at the same time preserved for future generations (UNESCO, 2003). As a matter of fact, while several studies have shown a positive correlation between tourism specialisation and long-term economic growth (Arezki et al., 2009), the results in relation to preservation are often less encouraging, as it emerges from multiple UNESCO areas from around the world (Lo Piccolo et al., 2012; Caust and Vecco, 2017; Tesfu et al., 2018; Tien et al., 2019; Krajíčková and Novotná, 2020). Of course, selected virtuous examples also exist, where the attractiveness of tourism destinations has been enhanced and managed through systemic and balanced sustainable development models that satisfy tourists and local stakeholders’ expectation (Loulanski and Loulanski, 2011; Liburd and Becken, 2017; Saarinen and Gill, 2018; Panzer-Krause, 2019; Del Baldo and Demartini, 2021; Trišić et al., 2022). As these experiences show, the reconciliation of environmental, economic, and social aspects is most often effectively pursued through the establishment of a coherent and integrated territorial governance framework (Lesniewska-Napierala et al., 2022).[2]

Acknowledging the above, with this paper we aim to contribute to the ongoing academic and policy debate on how to plan more sustainable tourism dynamics within UNESCO Heritage areas (see, e.g.: Di Giovine, 2008; Arezki et al., 2009; Lo Piccolo et al., 2012; Caust and Vecco, 2017). In particular, we argue that the multi-level integration and coordination of different instruments – spatial strategies, landscape plans, territorial management plans, etc. – is essential to define, steer and manage territorial development dynamics in areas of outstanding landscape beauty, both considering the logics of tourism-driven economic development, as well as ensuring their sustainability. Our argument is detailed with particular reference to a specific UNESCO World Heritage area – the vineyard landscape of Langhe-Roero and Monferrato (Italy) (WHL, 2014). Case studies are used extensively in tourism research and teaching as they can, among others, illuminate general issues through the examination of specific instances (Beeton, 2005) and support the evaluation of ongoing policy processes (Yin, 1992).[3] In particular, the case at stake has been investigated through a mixed methodology composed by document and policy analysis, as well as by focus groups involving selected local stakeholders. The policy analysis had a twofold use: on the one hand, it enabled us to understand the main characteristics of the area and to reflect on the challenges and potentials surrounding tourism development therein; on the other, it has helped us to outline the governance and policy framework through which the development of the area is currently managed, as well as to identify the main contents of the instruments that have been put in place. Once a preliminary understanding of the case study has been consolidated, its main elements have been discussed in a focus groups, organised to test, validate and enrich them with additional governance nuances that only actors that deal with tourism dynamics in the area could provide.[4]

The results of this activity is presented in the text below, structured into four sections. After this introduction, section 2 presents the case study of the Langhe-Roero and Monferrato wine region. Section 3 focuses on the territorial governance framework that has consolidated through time to steer, regulate, and manage the development of the area at stake, with particular reference to the Regional Landscape Plan and the UNESCO site management plan, and to the challenges that still persist. Finally, section 4 completes the contribution, summarising its main arguments and paving the way for future research on the matter.

A general premise on the main characteristics and challenges that characterise wine regions and tourism activities therein is provided here, to subsequently focus the attention on the Langhe-Roero and Monferrato wine region.

Wine regions are complex territorial systems usually covering large surfaces, which concern different administrative levels (e.g., various municipalities as well as wide area bodies as provinces and regions). They often feature polycentric systems composed of small and medium-sized settlements that depend on selected larger municipalities for the access to primary services. Due to their nature, they are characterised by both strengths and fragilities (Assumma, 2021). On the one hand, their local economies are rather strong and focussed on production of wine and other certified gastronomic excellences, which are sold nationally and exported internationally. Property values are generally high, due to the proximity to cultural and environmental assets and services. Moreover, the presence of a high share of forestry contribute to reducing the risk of natural hazards and mitigating their impact when they occur. All these aspects contribute to the economic attractiveness of wine regions (Tyrväinen and Miettinen, 2000; Van der Heide and Heijman, 2013; Gottero and Cassatella, 2017; Gullino and Larcher, 2014; Assumma et al., 2019), which are increasingly subject to recognition and strategies at the international level (Cassatella et al., 2021).[5]

On the other hand, however, wine regions face a number of socio-economic, climatic, and environmental challenges (Jones and Webb, 2010; Mozell and Thach, 2014). In some regions, for example, local communities have moved to main cities in search of higher quality of life, in so doing favouring the acquisition of agricultural lands by foreign investors and their transformation into vineyards. While the resulting increase in vineyards certainly generates a high economic return, it also contributes to a severe alteration of the landscape characteristics and value of these areas, which are very often rapidly turning to monoculture landscapes (Basso and Fregolent, 2021). At the same time, this substitution also occurs to the detriment of local cultural values as, although vineyards represent the structural factor of wine regions, this should not necessarily imply the exclusion of other permanent crops and their economies (e.g., olive groves, almond trees, etc.), which have in the past characterised the area. Additional challenges have been raised by climate change dynamics, which caused considerable losses in terms of vine plants and soil damages due to temperature and weather variations (e.g., heavy storms, strong winds and hailstorms, and low run-off performance) (Moriondo et al., 2013).

Be that as it may, the environmental and landscape value of wine regions is acknowledged by many entities, including various international organisations aiming at their management and preservation. As evidence of this incremental recognition, the UNESCO World Heritage List (WHL) counts several cultural landscapes characterised by the presence of the wine-growing areas, of which many are located in Europe: the Alto Douro wine region in Portugal (2001), the Tokaj region in Hungary (2002), the Langhe-Roero and Monferrato area in Italy (2014), the Champagne, Caves et Coteaux de Champagne in France (2015), etc. According to UNESCO, wine regions are the result of the wine-making process as a relationship between man and environment (“continuing landscapes,” in UNESCO’s words); as a consequence, they have developed a tourism offer that, drawing on multiple forms of attractiveness (from food and wine to wellness, from sports activities to cultural events, among others) had progressively managed to attract non-seasonal tourism flows (Lourenco-Gomes et al., 2015; Bruwler and Rueger-Muck, 2019). However, wine regions are increasingly endangered by climate-change related issues and the required adaptation measures may prove to limit tourism’s potential economic benefits in order to prevent the deterioration of environmental and landscape values. The challenge for spatial governance and planning is here to combine planning and management instruments at various scales in order to balance these trade-offs, to the benefit of tourists, local communities, as well as the overall territorial quality of the area.

The “vineyard landscape of Piedmont: Langhe-Roero and Monferrato” is a famous wine region located in South Piedmont, between the provinces of Alessandria, Asti and Cuneo (Fig. 1). Asti is the closest large city, located a 52-minute car ride from Turin. This context has recently been included in the UNESCO World Heritage List (WHC, 2014) as a “living cultural landscape,” according to specific cultural criteria, and integrity and authenticity requirements. The importance of this context exceeds regional and national boundaries, due to its Outstanding Universal Value (OUV). It is famous for excellent wines such as Barolo and Barbaresco, as well as for a variety of truffles and hazelnuts of Alba. The UNESCO candidacy begun in the early 2000s, involving a variety of public and private partners, and has been concluded in 2014.

a

b

Fig. 1. Case study localisation: (a) the vineyard landscape of Langhe-Roero and Monferrato

Source: authors’ own elaboration on Assumma 2021 and Geoportale Piemonte data (a); authors’ own elaboration on Assumma, 2021 on Google Images (b).

More in detail, the vineyard landscape of Langhe-Roero and Monferrato encompasses six OUV core zones, included within 2 buffer zones that serve a protecting function:

The present local economic system that characterises the Langhe-Roero and Monferrato area has developed and consolidated in the last thirty-forty years and was further boosted by its inclusion in the UNESCO WHL list. Even if the area had been severely affected by depopulation after World War II, the role of local entrepreneurs would have been pivotal for the valorisation of local resources and know-how as a powerful engine of growth.[6] Wine culture has incrementally consolidated as the main socio-economic asset of the region: on the one hand, this has contributed to consolidate the sense of belonging and the territorial identity of the local communities; on the other, it triggered in the main actors and stakeholders innovative perspectives in terms of production, communication, and branding.[7] Through the years, emerging opportunities and investments for the valorisation of local culture and products have increased the national and international visibility and competitiveness of the area, thus creating new professional figures actively involved in the production process.[8]

Importantly in the framework of this contribution, the inclusion of Langhe-Roero and Monferrato in the UNESCO WHL list resulted in a conspicuous rise in tourists flows as well as in an increase in the number of cultural and enogastronomic events. This phenomenon mainly concerned the “fly by” flows of those people who live nearby the area and in the neighbouring regions. At the same time, it has been accompanied by growing episodes of religious tourism, made possible by the presence of architectures and religious assets enhanced by the restoration of historical itineraries and paths, as well as by more sustainable forms of tourism like cycle-tourism and family outdoor experiences aiming at a “slower” fruition of the area landscape value.

Whereas these increasing tourism fluxes undoubtedly constitute an important economic asset for the area, they also open up a set of challenges that need to be tackled carefully, in order to preserve the cultural, environmental and landscape quality of the area. The UNESCO site attracts every year an increasing number of tourists from all over the world, and this has raised the need for managing tourism flows starting from a more integrated and sustainable mobility. More in detail, these tourists are in most cases from abroad and with little capacity for independent mobility in the area. Hence the need to understand how to address innovation in tourist mobility, going beyond the private-car model. The limited availability of tourist-friendly transport in an area where inhabitants and tourists travel by their own means due to the scarcity of an adequate public transport system constitutes a serious challenge. The impact of private motorised means of transport on an area that is unique in the world and needs to be preserved and developed sustainably is indeed a challenge, that needs to be weighted vis-à-vis tourists’ mobility needs and the quality of their experience. At the same time, the attractiveness of the various places of the UNESCO area is differential, leading to an uneven concentration of tourists that favour selected locations – e.g. the municipalities of Barolo and Barbaresco, and the city of Alba. This generates infrastructure congestion problems, as well as a non-homogeneous distribution of the economic benefits of tourism, while also unevenly concentrating the negative impact of tourism pressure on the territory.

In order to face these and other challenges that the increasing tourism fluxes are bringing along with them, a number of planning and management instruments have been developed through time. As it will be further detailed in the section that follows, despite their apparent fragmentation, it has been possible to develop a number of synergies between them, and to consolidate them within a more or less coherent, multilevel governance framework aimed at the sustainable spatial planning of the area.

As mentioned above, the increasing tourism pressures that have characterised the Langhe-Roero and Monferrato area since the turn of the new millennium and, in particular, since its inclusion in the UNESCO World Heritage List, require to be tackled through an integrated, multi-level governance framework devoted to this task. However, despite the long tradition boasted by the country in relation to tourism and the fact that, with 94 million tourists per year (2018), Italy is the third most visited country in international tourism arrivals,[9] the country’s spatial governance and planning system does not include instruments or regulations specifically dedicated to the development, management, and regulation of tourism or of the impact of this activity over its cultural, environmental, and landscape heritage.[10] As a consequence, traditional spatial planning activities appear generally ill-equipped to deal with tourism challenges. The land-use regulation approach that has characterised the country through time has mostly focused – especially outside the main urban areas – on the provision of increasing land-use and development rights (Cotella and Berisha, 2021), and does not seem to be able to either promote tourism in those inner area that would benefit from increasing tourism dynamics as an engine for development or to strategically re-orient tourism activities in those areas that are endangered by overtourism.

Despite the lack of explicit attention to tourism, however, a number of instruments exists that, when coordinated and fine-tuned, may represent an asset in this concern. Firstly, each Italian region is required to produce a Regional Territorial Plan (RTP), an instrument that should present the main orientation for socio-economic and spatial development, as well as address environmental protection, infrastructural development, and other sectoral issues. The RTP is legally binding for sub-regional levels, which have to develop their plans coherently. At the same time, municipalities (alone or joined in unions) are obliged to prepare Municipal General Regulatory Plans (PRGC), i.e., instruments that define land-use prescriptions for the whole territory that they concern. The PRGCs are legally binding for public and private actors, they indicate the main communication routes, public areas, areas for public buildings, protection for the environment and landscape, etc., and prescribe, through implementation regulations, the physical and functional status of the individual zones of the territory.

Through the relation between regional and municipal planning, there exists a possibility to approach tourism challenges from a multi-level perspective, with the Regional Territorial Plan that may approach them from a territorial, wider scale standpoint, to then either suggest guidelines on how to tackle them or enforce specific prescriptions on the matter. Importantly, the country is also provided with a consolidated system of Landscape planning that, at the regional level, runs in parallel and establishes synergies with the spatial planning activity. These occurs through the Regional Landscape Plans (RLP) that, since their introduction in 2004, have constituted the essential step for the conservation, planning and management of the regional landscape. RLPs extend to the whole regional territory, with the provision of different degrees of protection in relation to the recognition of landscape values and the consequent assignment of landscape quality objectives, as well as recovery interventions in degraded areas. These objectives imply that the protection of landscape should not be restricted to mere conservation and preservation, but should extend to the regulation of all human interventions intended to affect landscape. More specifically, RLPs have two main purposes: (i) a cognitive purpose, focusing on the analysis of regional landscape features (natural, cultural, property) and transformation dynamics in order to identify the risk factors and vulnerabilities of the landscape, and to address other acts of programming, planning and land protection; (ii) a directive purpose with legally binding measures, requirements for adaptation measures and simple recommendations for sub-regional and sectoral plans.

In the following subsections the Piedmont Regional Landscape Plan is presented, with particular reference to the attention it dedicates to the Langhe-Roero and Monferrato area. Then, the UNESCO site Management Plan is introduced, followed by a discussion of the future opportunities for coordination and integration of the multi-level governance system aiming at the sustainable spatial planning of the area.

The candidacy of the UNESCO site started in the early 2000s, in parallel to the development of the Piedmont RLP. The UNESCO perimeter was defined following the identification of Landscape Ambits and Units by this Plan. The area was not designated as a protected landscape (which would have implied strong prescriptive regulation), but subject to a special set of rules, agreed with the local authorities, in order to assure the protection of the landscape values and to demonstrate this will to the UNESCO Committee. Interestingly, the municipalities accepted to conduct the revision of their PRGCs on a voluntary basis, in so doing playing a role in the phase of the WHS candidacy. After the nomination, the “Guidelines for the municipal planning and building codes” (Regione Piemonte, 2015) were developed as a focus area of the RLP, anticipating its effective enforcement (2017).

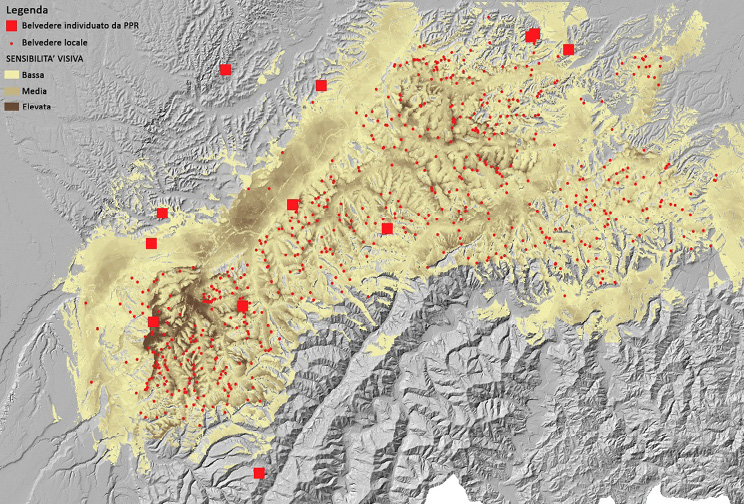

More specifically, the RLP devotes particular attention to the scenic features of the landscape, identifying and regulating viewpoints, panoramic routes, landmarks, skylines, etc. (Cassatella 2015). Guidelines for the management of landscape scenery are also provided, in order to guide local authorities in the process at the local scale.[11] In the UNESCO Site these guidelines were replicated, tested and further developed, thanks to a high local awareness and interest to enhance landscape attractiveness. One of the main tasks of the process is the viewshed analysis through GIS, which provides maps of areas visible from the many vantage points and panoramic routes, in so doing enabling a more accurate design and a thorough control in the phase of authorisation of spatial transformations.

The control of the landscape’s visual impact of interventions in the area is particularly challenging due to two factors: a high degree of intervisibility among centres and landmarks (a special feature of this hilly landscape, which contributes to its charm) and the administrative fragmentation of the territory characterised by very small municipalities, most often counting less than 500 inhabitants, with the consequence that each intervention authorised by a municipality is very likely to impact on others in terms of viewing opportunities. To overcome this issue, the local authorities agreed on creating one map of the cumulative intervisibility for the entire site, which was elaborated by the region, considering all the viewpoints identified and nominated locally by the municipalities, in a collaborative process (Fig. 2). The resulting map is to be used by each municipality in its reviews of visual impact assessment of interventions, enabling them to ensure intervisibility at a wider scale.

The attempt to enhance landscape scenery also resulted in direct interventions aimed at removing detrimental factors: a mitigation of the visibility of industrial buildings and the demolition of obsolete technical structures were conducted thanks to regional funding, and to the funding from private foundations. Landscape scenery here is intended both as an asset for the touristic attractiveness, and as a perceivable expression of local identity. The process experienced in the Langhe-Roero and Monferrato UNESCO Site shows that the enhancement of landscape scenery can be an opportunity for integrating top-down planning regulations and bottom-up initiatives, with landscape planning acting as a catalyst.

Fig 2. Map of cumulative visibility in the Langhe area. The squares indicate the viewpoints identified by the RLP, the dots those added by municipalities

Source: C. Cassatella and P. Guerreschi on data Piedmont Region, 2015.

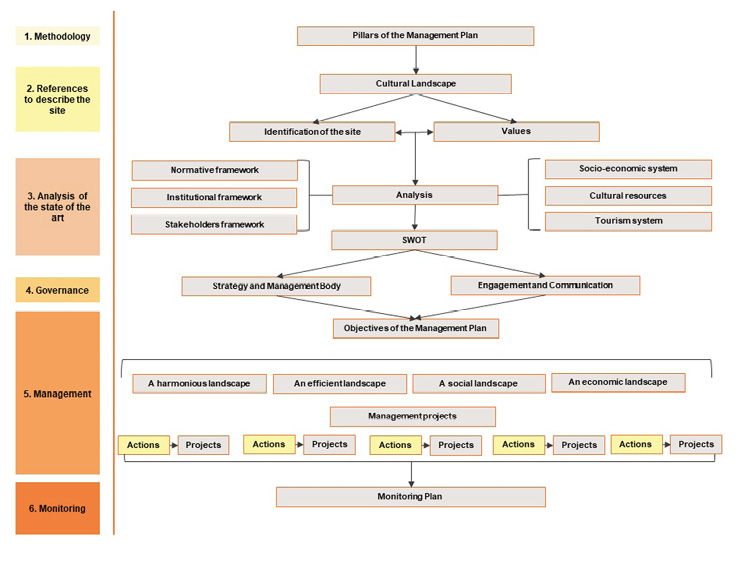

The UNESCO candidacy process of a site requires a Dossier and a Management Plan with the function of protecting and managing the State of Conservation (SOC) of the value over time. The complexity of wine regions management is a widely debated topic, since it must deal with cultural heritage protection, environmental compatibility, as well as spatial planning (Pettenati, 2019). As a consequence, the candidacy of the Langhe-Rero and Monferrato area required a strong cooperation between actors and stakeholders and the mobilisation of cognitive, legal, political, and financial resources all aimed at envisioning a winning strategy of valorisation and management (Fig. 3). The site candidacy led to the foundation of a management body, namely the Association for the heritage of the vineyard landscape of Langhe-Roero and Monferrato (2011), with the purpose of coordinating and implementing the Management Plan, as well as of strengthening governance, cultural promotion, awareness-raising, and the integrated planning action of the municipalities included in the UNESCO site. More specifically, the main objectives of the Association are: a) to reduce territorial fragmentation through designing large-scale cohesion projects; b) to favour the cooperation between public and private actors according to principles of transparency, accountability, and sharing; and c) to develop marketing strategies that balance tradition and innovation.

The Management Plan also provides a monitoring plan for which Regione Piemonte acts as the main responsible actor, since it must organise and prioritise the projects’ executive process, integrate both ICOMOS and UNESCO recommendations within sets of Key Performance Indicators (KPI) (environment, history and culture, and perception), and provide periodic reports to check the monitoring process. As the monitoring activity required the development and consolidation of comprehensive, geo-referenced knowledge, Regione Piemonte collaborates with several agencies and foundations (Sitad, Arpa Piemonte, Links Foundation, etc.) to populate information about the relevant components of the site according to a multidisciplinary approach. Thanks to these efforts, the KPI indicators were integrated in an online GIS tool called the Interactive Visualization Tool (InVito. Valle and Soldano, 2017), then also employed in an Impact Assessment activity by UNESCO.

Fig. 3. Structure of the UNESCO Management Plan of the case study

Source: authors’ own elaboration on Valle and Soldano, 2017.

The Management Plan of the Langhe-Roero and Monferrato area is considered innovative since it deals with both the management of tangible and intangible assets and with the development of all human activities in the area (see Table 1). More specifically, it identifies four strategic objectives to conserve and manage the OUV value: i) harmonious landscape (where to design), meaning that actors and stakeholders have to implement sets of actions for a more conscious spatial planning; ii) social landscape (where to live) refers to the need to preserve the local identity and the sense of belonging to the site, and also attracting new social capital; iii) economic landscape (where to work), which refers to the identification of sustainable solutions that can favour entrepreneurships to contrast economic pressures and with benefits to local development; and iv) efficient landscape (where to manage), for managing effectively resource availability and improving cooperation between institutions and local communities. As each strategy concerns the implementation of specific projects, there is a need for a coordinated governance model to accompany the management process and to integrate its action with that of the other planning instruments active in the area at various territorial levels.

| Objectives | Priority axes |

|---|---|

| 1) Harmonious landscape (where to design) | Processing and systematisation of guidelines for recovery and planning; Rehabilitation and recovery of city centres and their building heritage; Creating lookouts and observation points; Sharing opportunity, training and research institution. |

| 2) Social landscape (where to live): | Landscape protection increases the sense of belonging and identity in local communities, encouraging human capital into the site; |

| 3) Economic landscape (where to work): | Local productive heritage; Creation of museums and tourism centres; Improving and consolidating the local tourist offer; Promotion of cultural and tourist resources; Rationalisation of signage; Viewpoints valorisation; |

| 4) Efficient landscape (where to manage) | Coordination of territorial databases and artefacts and structures census; Strengthening of research and training centres; Research studies on winemaking heritage; Proposing “slow” tourism routes; Dissemination of information between partners at international scale; |

The introduced instruments, i.e., the RLP and the UNESCO Site Management Plan, together with the statutory spatial planning instruments, i.e., the RTP and the PRGCs of the involved municipalities, and with other sectoral and/or episodic interventions, i.e., the recent National Recovery and Resilience Plan, the EU Cohesion Policy Programming Period 2021–27, etc. constitute important elements of what could consolidate as an integrated multi-level territorial governance framework aimed at the sustainable spatial planning of the Langhe Roero and Monferrato area. In order for this to happens, however, a number of challenges still need to be faced:

This paper discussed the planning and management instruments that, within the Italian spatial governance and planning system, could contribute to virtuously steering and regulating the development of tourism in a way that both encourages local economic development while preserving environmental and cultural assets in a sustainable way. In particular, this was done in relation to a wine region that has recently entered the UNESCO World Heritage List and has, since then, experienced growing tourism fluxes and related challenges.

As highlighted in the text, despite the absence of any specific instruments in the Piedmont region devoted to tourism planning and management, both spatial and landscape planning have been used to support the design of a more sustainable development of tourism in the analysed area. The fact that in Italy spatial planning competences are jointly managed at the central and the regional levels, has indeed influenced the process, with the Piedmont region acting as the main player. More specifically, the Region has been responsible for drafting both the Regional Territorial Plan and the Regional Landscape Plan, and is currently in the process of producing a renewed version of the former that will consider the provisions of the latter to a full extent. At the same time, these spatial and landscape planning processes have also influenced the candidacy and management of the UNESCO site, with Regione Piemonte that has played a very important role in the coordination and management of all activities ongoing in the vineyard landscape. The strong leadership of the regional government has also manifested through constant attempts to engage with the local municipalities as well as other actors in the territory, belonging to both the private sector and the civil society. This is clear in the UNESCO site Management Plan (and in the structure of the Association), which highlights the importance of cooperation between decision makers, private stakeholders, local associations, and citizens, in order to enhance the visibility of the area at the international level, while at the same time preserving its intrinsic value. On their part, the municipalities belonging to the vineyard landscape had answered to the regions’ call with a proactive, flexible attitude, and were keen to territorialise the guidelines received from the region in the review of their municipal plans through specific rules of protection (such as camouflage actions for barns), despite the Italian bureaucratic apparatus is considered very rigid and centralised. At the same time, some limits still persist, as for instance the fact that the employment of these protection rules – as well as the measures of the UNESCO Management Plans – concern only the specific perimeter of the UNESCO site, partially overlaying the municipalities, and in so doing producing differences of regulations and investments between municipalities and within the same municipality (WHC, 2014).

Overall, the presented experience clearly shows how landscape values present a high potential to catalyse the actions of different actors and sectors to collaborate towards its exploitation and valorisation towards tourism-based economic development. In order for this process not to generate a negative impact on the assets that it aims to extract value from, however, there is a need to put in place an integrated, multi-level territorial governance framework that would steer and regulate such development towards a sustainable direction. Despite the absence of dedicated instruments, the integration and synergies established between the Regional Territorial Plan, the Regional Landscape Plan and the planning activities of the involved municipalities has produced promising results.[15] Despite the challenges that still need to be addressed, and which have been discussed in this paper, the case of Langhe-Roero and Monferrato is nowadays considered as a good practice for the entire Piedmontese territory, with “wine roads” that are being promoted in several areas of the region, paying attention to enhancing the linkages between the product and the local landscape and its experience.[16]

However, the success of these emulation experiences is by no mean granted, as the success of the UNESCO area can hardly be replicated in other areas, such as alpine valleys, which are characterised by valuable landscapes but lack convenient conditions for agricultural production or touristic accessibility. In this concern, a promising avenue for further research could be represented by the exploration of the actual potential for transferability of the identified success case and while the whole process is not possible to transfer as a whole, some elements of it may constitute useful ‘triggers’ of good territorial governance in similar contexts and situations (Cotella et al., 2015).

ADIE, B. A., FALK, M. and SAVIOLI, M. (2020), ‘Overtourism as a perceived threat to cultural heritage in Europe’, Current Issues in Tourism, 23 (14), 1737–1741. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1687661

AREZKI, M. R., CHERIF, R. and PIOTROWSKI, J. M. (2009), Tourism specialization and economic development: Evidence from the UNESCO World Heritage List, International Monetary Fund.

ASSUMMA, V. (2021), Assessing the Resilience of Socio-Ecological Systems to Shape Scenarios of Territorial Transformation, Ph.D. Thesis, Politecnico di Torino.

ASSUMMA, V. and VENTURA, C. (2014), ‘Role of Cultural Mapping within Local Development Processes: A Tool for the Integrated Enhancement of Rural Heritage’, Advanced Engineering Forum, 11, pp. 495–502, DOI:10.4028/www.scientific.net/AEF.11.495

ASSUMMA, V., BOTTERO, M. and MONACO, R. (2019), ‘Landscape Economic Attractiveness: An Integrated Methodology for Exploring the Rural Landscapes in Piedmont (Italy)’, Land 2019, 8 (7), p. 105. https://doi.org/10.3390/land8070105

BASSO, M. and FREGOLENT, L. (2021), ‘Fighting Against Monocultures: Wine-Growing and Tourism in the Veneto Region’, [in:] Social Movements and Public Policies in Southern European Cities, pp. 151–165. Cham: Springer.

BEETON, S. (2005), ‘The case study in tourism research: A multi-method case study approach’, Tourism research methods: Integrating theory with practice, 37, 48.

BERISHA, E., CAPRIOLI, C. and COTELLA, G. (2022), ‘Unpacking SDG target 11. a: What is it about and how to measure its progress?’, City and Environment Interactions, 14, 100080. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cacint.2022.100080

BERISHA, E., COTELLA, G., JANIN RIVOLIN, U. and SOLLY, A. (2021), ‘Spatial governance and planning systems in the public control of spatial development: a European typology’, European planning studies, 29 (1), pp. 181–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2020.1726295

BOHÁČ, A. and DRÁPELA, E. (2022), ‘Overtourism Hotspots: Both a Threat and Opportunity for Rural Tourism’, European Countryside, 14 (1), pp. 157–179. https://doi.org/10.2478/euco-2022-0009

BRUWER, J. and RUEGER-MUCK, E. (2019), ‘Wine tourism and hedonic experience: A motivation-based experiential view’, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 19 (4), pp. 488–502. https://doi.org/10.1177/1467358418781444

CASSATELLA, C. (2015), ‘Landscape scenic values. Protection and management from a spatial planning perspective’, [in:] GAMBINO, R. and PEANO, A. (eds.), Nature Policies and Landscape Policies: Towards an Alliance, Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 341–351. DOI:10.1007/978-3-319-05410-0.

CASSATELLA, C. and BONAVERO F. (eds.) (2020), Guide transfrontalier pour la conservation et la réhabilitation des paysages viticoles alpins/Guida transfrontaliera per la conservazione e il recupero dei paesaggi viticoli alpine, Politecnico di Torino, http://hdl.handle.net/11583/2830645

CASSATELLA, C., BONAVERO, F. and SEARDO, B. M. (2021), ‘Les paysages viticoles alpins: clés d’interprétation et attributions de valeurs | I paesaggi viticoli alpini: categorie interpretative e riconoscimenti di valore’, [in:] Guide transfrontalier pour la conservation et la réhabilitation des paysages viticoles alpins | Guida transfrontaliera per la conservazione e il recupero dei paesaggi viticoli alpine, Politecnico di Torino, pp. 8–11. http://hdl.handle.net/11583/2830645

CAUST, J. and VECCO, M. (2017), ‘Is UNESCO World Heritage recognition a blessing or burden? Evidence from developing Asian countries’, Journal of Cultural Heritage, 27, pp. 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2017.02.004

CEC – COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES (2019), The European Green Deal, European Commission 53, 24. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

COTELLA, G. and BERISHA, E. (2021), ‘Inter-Municipal Spatial Planning as a Tool to Prevent Small-Town Competition: The Case of the Emilia-Romagna Region’, [in:] BANSKY, J., (ed.), The Routledge Handbook of Small Towns, London: Routledge, pp. 313–329.

COTELLA, G., JANIN RIVOLIN, U. and SANTANGELO, M. (2015), ‘Transferring good territorial governance in Europe: opportunities and barriers’, [in:] SCHMIDT, P. and VAN WELL, L. (eds.), Territorial governance across Europe: Pathways, practices and prospects, London: Routledge, pp. 238–253. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315716220

COTELLA, G. and VITALE BROVARONE, E. (2021a), ‘Rethinking urbanisation after COVID-19. What role for the EU cohesion policy’, Town Planning Review, 92 (3), pp. 411–418. https://dx.doi.org/10.3828/tpr.2020.54

COTELLA, G. and VITALE BROVARONE, E. (2021b), ‘Questioning urbanisation models in the face of Covid-19’, TeMA-Journal of Land Use, Mobility and Environment, pp. 105–118. https://doi.org/10.6092/1970-9870/6913

COTELLA, G. and VITALE BROVARONE, E. (2022), ‘Can tourism tackle marginalisation effectively? The case of the Italian National Strategy for Inner Areas’, European Spatial Research and Policy, 29 (2), pp. 59–77. https://doi.org/10.18778/1231-1952.29.2.04

DE URIOSTE-STONE, S., MCLAUGHLIN, W. J., DAIGLE, J. J. and FEFER, J. P. (2018), ‘Applying case study methodology to tourism research’, [in:] Handbook of research methods for tourism and hospitality management, pp. 407–427, Edward Elgar Publishing.

DEL BALDO, M. and DEMARTINI, P. (2021), ‘Cultural heritage through the «youth eyes»: Towards participatory governance and management of UNESCO sites’, [in:] Cultural Initiatives for Sustainable Development, pp. 293–319, Cham: Springer.

DI GIOVINE, M. A. (2008), The heritage-scape: UNESCO, world heritage, and tourism, Lexington Books.

DODDS, R. and BUTLER, R. (2019), ‘The phenomena of overtourism: A review’, International Journal of Tourism Cities, 5 (4), pp. 519–528. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-06-2019-0090

EVANS, J., KARVONEN, A., LUQUE-AYALA, A., MARTIN, C., MCCORMICK, K., RAVEN, R. and PALGAN, Y. V. (2019), ‘Smart and sustainable cities? Pipedreams, practicalities and possibilities’, Local Environment, 24 (7), pp. 557–564. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2019.1624701

FONDAZIONE CRC (2014), ‘I quadri della Fondazione della Cassa di Risparmio di Cuneo. Langhe e Roero’, Tradizione e Innovazione, 22. https://www.fondazionecrc.it/index.php/analisi-e-ricerche/quaderni/23-q22/file

GOTTERO, E. and CASSATELLA, C. (2017), ‘Landscape indicators for rural development policies. Application of a core set in the case study of Piedmont Region’, Environmental Impact Assessment Review 65, pp. 75–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2017.04.002

GULLINO, P. and LARCHER, F. (2013), ‘Integrity in UNESCO World Heritage Sites. A comparative study for rural landscapes’, Journal of Cultural Heritage, 14 (5), pp. 389–395. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.culher.2012.10.005

IPCC (2019), Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, Ipcc - Sr15. https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/

JONES, G. V., and WEBB, L. B. (2010), ‘Climate change, viticulture, and wine: challenges and opportunities’, Journal of Wine Research, 21 (2–3), pp. 103–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571264.2010.530091

KRAJÍČKOVÁ, A. and NOVOTNÁ, M. (2020), ‘Unsustainable imbalances in tourism development? Case study of Mikulov region (Czech Republic)’, Sostenibilidad Turística: overtourism vs undertourism, pp. 567–579.

LEŚNIEWSKA-NAPIERAŁA, K., PIELESIAK, I. and COTELLA, G. (2022), Foreword, European Spatial Research and Policy, 29 (2) pp. 9–15. https://doi.org/10.18778/1231-1952.29.2.01

LIBURD, J. J. and BECKEN, S. (2017), Stewardship Values in Tourism, Innovation and UNESCO World Heritage Governance: The Great Barrier Reef and the Danish Wadden Sea.

LO PICCOLO, F., LEONE, D. and PIZZUTO, P. (2012), ‘The (controversial) role of the UNESCO WHL Management Plans in promoting sustainable tourism development’, Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 4 (3), pp. 249–276. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2012.711087

LOULANSKI, T. and LOULANSKI, V. (2011), ‘The sustainable integration of cultural heritage and tourism: A meta-study’, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19 (7), pp. 837–862. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2011.553286

LOURENÇO-GOMES, L., PINTO, L. M. and REBELO, J. (2015), ‘Wine and cultural heritage. The experience of the Alto Douro Wine Region’, Wine Economics and Policy, 4 (2), pp. 78–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wep.2015.09.001

MORIONDO, M., JONES, G. V., BOIS, B., DIBARI, C., FERRISE, R., TROMBI, G. and BINDI, M. (2013), ‘Projected shifts of wine regions in response to climate change’, Climatic Change, 119 (3), pp. 825–839. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-013-0739-y

MOZELL, M. R. and THACH, L. (2014), ‘The impact of climate change on the global wine industry: Challenges & solutions’, Wine Economics and Policy, 3 (2), pp. 81–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wep.2014.08.001

PANZER-KRAUSE, S. (2019), ‘Networking towards sustainable tourism: Innovations between green growth and degrowth strategies’, Regional Studies, 53 (7), pp. 927–938. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2018.1508873

PETTENATI, G. (2019), I paesaggi culturali UNESCO in Italia. Nuove Geografie. Strumenti di lavoro, FrancoAngeli, Milano.

REGIONE PIEMONTE (2015), Linee guida per l’adeguamento dei piani regolatori e dei regolamenti edilizi alle indicazioni di tutela per il sito UNESCO, approved with D.G.R. 26-2131, 21 Sep 2015. http://www.regione.piemonte.it/territorio/dwd/paesaggio/linee_guida_Unesco.pdf [accessed on: July 2022]

RETE RURALE NAZIONALE (2011), La Governance dello sviluppo locale nelle Langhe. https://www.reterurale.it/flex/cm/pages/ServeAttachment.php/L/IT/D/8%252F2%252Fd%252FD.f63599ce0e6b91dacdf5/P/BLOB%3AID%3D6090/E/pdf [accessed on: 17.07.2022].

RYE, J. F. (2006), ‘«Rural Youths» Images of the Rural’, Journal of Rural Studies, 22 (4), pp. 409–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2006.01.005.

SAARINEN, J. and GILL, A. M. (eds.) (2018), Resilient destinations and tourism: Governance strategies in the transition towards sustainability in tourism, Routledge.

SANTERAMO, F. G., SECCIA, A. and NARDONE, G. (2017), ‘The synergies of the Italian wine and tourism sectors’, Wine Economics and Policy, 6 (1), pp. 71–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wep.2016.11.004

SOLLY, A., BERISHA, E. and COTELLA, G. (2021), ‘Towards sustainable urbanization. Learning from what’s out there’, Land, 10 (4), p. 356. https://doi.org/10.3390/land10040356

TERKENLI, T. S. (2014), ‘Landscapes of Tourism’, [in:] Lew, A. A., Hall, C. M., and Williams, A. M. (eds.), The Wiley Blackwell Companion to Tourism, Oxford: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

TESFU, F., WELDEMARIAM, T. and ASERSIE, M. (2018), ‘Impact of human activities on biosphere reserve: A case study from Yayu Biosphere Reserve, Southwest Ethiopia’, International Journal of Biodiversity and Conservation, 10 (7), pp. 319–326. DOI: 10.5897/IJBC2016.1005

TIEN, N. H., DUNG, H. T., VU, N. T., DOAN, L. and DUC, M. (2019), ‘Risks of unsustainable tourism development in Vietnam’, International Journal of Research in Finance and Management, 2 (2), pp. 81–85.

TRIŠIĆ, I., PRIVITERA, D., ŠTETIĆ, S., PETROVIĆ, M. D., RADOVANOVIĆ, M. M., MAKSIN, M. and LUKIĆ, D. (2022), ‘Sustainable Tourism to the Part of Transboundary UNESCO Biosphere Reserve «Mura-Drava-Danube.» A Case of Serbia, Croatia and Hungary’, Sustainability, 14 (10), p. 6006. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14106006

TURRI, E. (2004), Il paesaggio e il silenzio, Marsilio, Venezia.

TYRVÄINEN, L. and MIETTINEN, A. (2000), ‘Property prices and urban forest amenities’, Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 39, pp. 205–223. https://doi.org/10.1006/jeem.1999.1097

UNESCO (2003), The Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. https://ich.unesco.org/doc/src/01852-EN.pdf [accessed on: 07.2022].

UNITED NATIONS (2015), Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. A/RES/70/1. United Nations. https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda [accessed on: 07.2022].

VALLE, M. and SOLDANO, S. (2017), Monitorare il sito Unesco dei paesaggi vitivinicoli di Langhe, Roero e Monferrato, http://www.regione.piemonte.it/fsc/dwd/2017/UNESCO_vitivinicoli_16_06_2017.pdf [accessed on: 07.2022].

VAN DER HEIDE, C. M. and HEIJMAN, W. J. M. (2013), The Economic Value of Landscapes, London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203076378

VITALE BROVARONE, E., COTELLA, G. and STARICCO, L. (2022), Rural Accessibility in European Regions, London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003083740

WORLD HERITAGE COMMITTEE (2014), ‘Vineyards Landscape of Piedmont: Langhe-Roero and Monferrato’, Candidacy Dossier, 1–2.

YIN, R. K. (1992), ‘The case study method as a tool for doing evaluation’, Current Sociology, 40 (1), pp. 121–137.