Abstract. Remote rural areas are often rich in natural and landscape assets, which are in turn used as the main focus of tourism development strategies aiming at reverting their decline. However, mono-functional strategies hardly manage to achieve this goal, as in order to restore those structural conditions that are essential to liveability and local development it is necessary to engage in a more comprehensive approach. Acknowledging this challenge, the paper reflects on the possibility to include tourism within multi-level development strategies aimed at tackling marginalisation, drawing on the case of the Italian National Strategy for Inner Areas. More in detail, the authors analyse how the latter enables the integration of tourism-related actions into more comprehensive, place-based development strategies that act upon the peculiarities of the territories they focus on through a mix of top-down and bottom-up logics.

Key words: tourism, remote areas, EU cohesion policy, Italy, place-based approach.

Tourism is often the main focus of strategies aiming at enhancing the development of remote rural areas, for which natural and landscape resources constitute in most cases the main asset. However, various analyses have demonstrated that the adoption of this approach in isolation may not be sufficient to tackle marginalisation effectively (Nguyen and Funck, 2019; Bohlin et al., 2020). The negative trends that characterise remote rural areas are often rooted in decades of endogenous and exogenous erosions of those structural conditions that are essential to liveability and local development, and their inversion requires more complex, integrated actions.

Aiming at providing evidence of how tourism can be integrated within multi-level development strategies tackling marginalisation, the article discusses the case of the Italian National Strategy for Inner Areas (SNAI). Running in parallel to the 2014–2020 EU cohesion policy programming period, the latter has been used to combine European and national resources to trigger development in the country’s remote rural regions, and it has been relaunched for the programming period 2021–2027. More in detail, the authors analyse, both quantitatively and qualitatively, how tourism has been integrated within 72 SNAI project areas’ strategies that have been launched during the programming period 2014–2020, to then discuss the challenges and opportunities that emerge from this experience.

After this brief introduction, section two sets the context for the contribution, discussing the causes of rural marginalisation, and how tourism has often been presented as a panacea for inverting negative development trends, although with controversial results. Then, after a brief reference to the methodology adopted in the study, the nature of the SNAI and its functioning are introduced to the reader. Section five constitutes the core of the analysis, exploring how and to what extent tourism has been integrated within the SNAI’s comprehensive, multi-fund local development strategies. The concluding section completes the contribution, discussing the outcomes of the analysis and bringing forward future research avenues.

With industrialisation and the increasing attractiveness of urban areas, many European rural areas have undergone intense processes of marginalisation (Camarero and Oliva, 2016; Küpper et al., 2018; Vitale Brovarone et al., 2022). Especially those rural areas that are not close to (or part of) functional urban areas, have been progressively emptied, as urban poles attracted their population. The ageing index has increased, leading to a process of natural decline in population size and composition. Together with depopulation, a number of social, economic and cultural interrelated factors come into play. For instance, de-anthropisation of natural and open spaces, the weakening of social ties, and the loss of cultural values and identity are key aspects of the impoverishment of rural areas.

These processes reflect – and are paralleled by – a thorough permeation of the urban society into the rural, also as a consequence of the increasing globalisation. Second homes and accommodation facilities proliferated with very loose planning control (Gallent and Tewdwr-Jones, 2018), especially in deep rural areas and mountains, for the exploitation of rural assets for tourism and leisure. Moreover, the local values, identities and ambitions of rural dwellers have been increasingly influenced by urban models. Decade after decade, rural areas gradually lost their value as places of production, while their attractiveness as places for consumption, for tourism and leisure, prevailed (Gallent and Gkartzios, 2019). All these processes induced a progressive rarefaction of the rural civitas, that is, the set of elements such as social ties, services, institutions, and functions offering residents the conditions for civilised life (Dematteis, 2009). The dependence of rural dwellers on urban nodes is both a cause and a consequence of this decline: services and amenities have progressively decreased, as the number of potential users needed to ensure their provision diminished, generating severe impacts on accessibility and social justice (Oliva and Camarero, 2019).

The mentioned challenges are widely acknowledged; nevertheless, they are still mostly overlooked by the policy arena, where urban issues have been dominating planning theory and practice (Cotella, 2019). In spite of the emergence of the city-regionalism paradigm, a city-centric approach has continued to prevail, reinforcing existing centralities and hierarchies and further marginalising rural areas (Urso, 2021). Local actors often remain distant from the decision-making arenas responsible for developing wide-ranging, long-term development policies and rural development remains grounded on decision-making centres that have limited knowledge and understanding of the needs of rural areas (Harrison and Heley, 2015; Cotella and Vitale Brovarone, 2020a, 2020b). To add further complexity to the picture, the COVID-19 emergency challenged rural areas in many ways, to a large extent exacerbating existing criticalities, such as their higher exposure to severe illness due to high old-age index, the digital divide, limited access to health services, the lack of local services and opportunities, etc.

However, as every crisis, COVID-19 has also brought opportunities, to rethink rural areas and urban-rural relations (Cotella and Vitale Brovarone, 2020b, 2021; Luca, Tondelli and Åberg, 2020; OECD, 2020). Beyond simplistic claims for a return to the rural, the pandemic has unveiled once more the complex interrelations linking several factors at play, hence calling for comprehensive action on the roots of rural marginalisation. On the contrary, most strategies continue to pivot on the notion of the “rural idyll”, a widespread social representation in developed economies, especially among young people (Halfacree, 1995; Rye, 2006), and continue to regard leisure and tourism as the main leverage of the development of the rural.

Many strategies aimed at the development of rural areas focus on tourism as leverage for counteracting marginalisation through the enhancement of their natural and cultural resources. Although rural tourism is not a new phenomenon, its development has accelerated in recent years, by virtue of a renewed interest for remote and uncrowded places (further emphasized by the consequences of COVID-19), nature, unspoiled landscapes, and cultural traditions (Greffe, 1994). Moreover, literature on rural tourism has been substantially growing, especially since 2010 and in the disciplines of tourism and rural studies, and often mentions rural tourism as a means to revitalise and regenerate marginalised rural areas (Rosalina et al., 2021; Singhania et al., 2022). Especially in declining territories facing “post-productive” challenges, tourism is considered as a key factor for development, with significant economic impacts, also in terms of supply chain (Kauppila et al., 2009; Brouder, 2012; Rogerson and van der Merwe, 2016). Moreover, areas with a strong tourist vocation and subject to significant flows often feature a more positive net population change than non-touristic ones, as well as a younger population and a better gender balance (Möller and Amcoff, 2018).[1]

Despite the role it can play as development driver, tourism is not, however, always representing a quick win (see also Assumma et al., 2022). While in some areas investments in tourism have been successful, in others they had a limited impact (Nguyen and Funck, 2019; Bohlin et al., 2020) or even generated negative externalities. The complexity of the rural environment is often overlooked by mono-dimensional strategies focusing only on tourism (Brouder, 2012), with the transition of rural areas from places of production to places of consumption that is overshadowed by the mentioned discourse on the rural idyll, which identifies the rural as a utopia of harmony, tranquillity and safety (Rofe, 2013). Warnings against the challenges of rural tourism and nature-based tourism development in marginal areas date back to the mid-1990s, their main concerns relating to the actual capacity of rural territorial systems to generate endogenous development rather than falling into overdependence on external markets exploiting their natural and cultural assets (Bramwell, 1994; Hall and Boyd, 2004). The effect of this so-called “staple trap” can be summarised as being (i) primarily based on natural resources, (ii) dependent on government mediation, and (iii) highly susceptible to external market fluctuations (Schmallegger and Carson, 2010) and, overall, warns against the negative impacts of sectoral development initiatives based only on tourism.

In order to develop rural tourism in ways where the supply of tourist facilities and experiences is appropriate to the needs of the host community, the environment and local suppliers, rural tourism should not develop as a hapless outcome of inexorable, external forces, and prominence should be given to the role of local communities and local businesses in shaping rural tourism (Bramwell, 1994). In the remainder of the paper, the way in which this issues are framed within the local development strategies launched within the SNAI framework will be presented.

The analysis adopts a mixed methodology, which relies on both quantitative and qualitative sources. The document analysis is based on official documents and datasets of the SNAI, made publicly available by the Italian Agency for Territorial Cohesion.[2] Qualitative insights on the implementation of the strategy have been gained through participant observation (Kawulich, 2005) in three working tables of the SNAI process in one of the project areas (Valle Arroscia) and seven semi-structured interviews collected during the ESPON URRUC project[3] (Bacci et al., 2022; ESPON, 2019; Cotella and Vitale Brovarone, 2020a). The interviews concerned both general questions on the development of the SNAI, and questions more specifically related to accessibility, mobility, and their integration with the other axes, including tourism. Relevant stakeholders were interviewed, including in particular: the regional contact person responsible for the coordination of SNAI, mayors of the municipalities involved in the local strategy, officers involved in the development of the mobility axis of SNAI at the national level, and contact persons of local associations. In participant observations, the researchers joined the meetings as observers and intervened only when asked to give their opinion (on rare occasion). Participant observation enabled them to engage with a wider and more varied set of stakeholders (5–20 participants, depending on the meeting) and observe their interactions, detecting information and dynamics that would hardly have emerged from the analysis of official documents or interviews.

The analysis focused on the general purposes of the strategy, its structure, and the process for implementation (Barca et al., 2014; Cotella and Vitale Brovarone, 2020c), when possible relating it to the disciplinary debate briefly presented in the previous paragraph. The overall orientation of the strategy was explored through the analysis of the official general and guideline documents, interviews and participant observation. Subsequently, the analysis focused on 72 local strategies, and in particular on the absolute and relative importance of tourism, in terms of financial allocation and strategic orientation. These aspects were extracted from the following sources: annual reports of SNAI, summaries of the financial allocation of framework program agreements, final documents of area strategies, and existing literature. Qualitative insights from interviews and participant observation helped to triangulate and interpret the results.[4]

Launched in 2012 by the then Minister of Territorial Cohesion Fabrizio Barca, the SNAI is aimed at promoting the development of the so-called ‘inner areas’, i.e., those territories that are located at a significant distance from the centres providing essential services (Barca et al., 2014). Typically characterised by small centres with a low settlement density, these areas are affected by the phenomena of ageing, depopulation, and impoverishment, and at the same time they are the depositaries of considerable environmental and cultural resources. The general objective of the SNAI is to reverse the decline of these areas, intervening on the phenomena behind their socio-economic and structural fragility.

Importantly, the SNAI overcomes the traditional north-south dichotomy that has characterised the Italian regional development policies since the country’s unification (Felice and Lepore, 2017; Tulumello et al., 2020), recognising that also the northernmost and central regions of the country feature the presence of remote territories that are lagging behind in social and economic terms due to their territorial marginality. In so doing, it also goes beyond the EU cohesion policy approach that pivots the distribution of resources at NUTS2 regions, adopting a more granular scale to read territorial unbalances (Cotella, 2020; Cotella and Vitale Brovarone, 2020a, 2020c; Cotella and Dąbrowski, 2021). By recognising access to services throughout the territory as an essential precondition for development, the strategy recognises the potential value of Italy’s polycentric settlement structure also in relation to remote rural and mountain areas (Urso, 2016). More in detail, it sets three interrelated objectives for inner areas: (i) to preserve and secure territories, (ii) to promote the natural and cultural diversity of places, and (iii) to enhance the potential of underused resources. To achieve these objectives, it operates on the one hand on essential services of citizenship (health, education, and mobility), and, on the other, on local development processes (Barca et al., 2014).

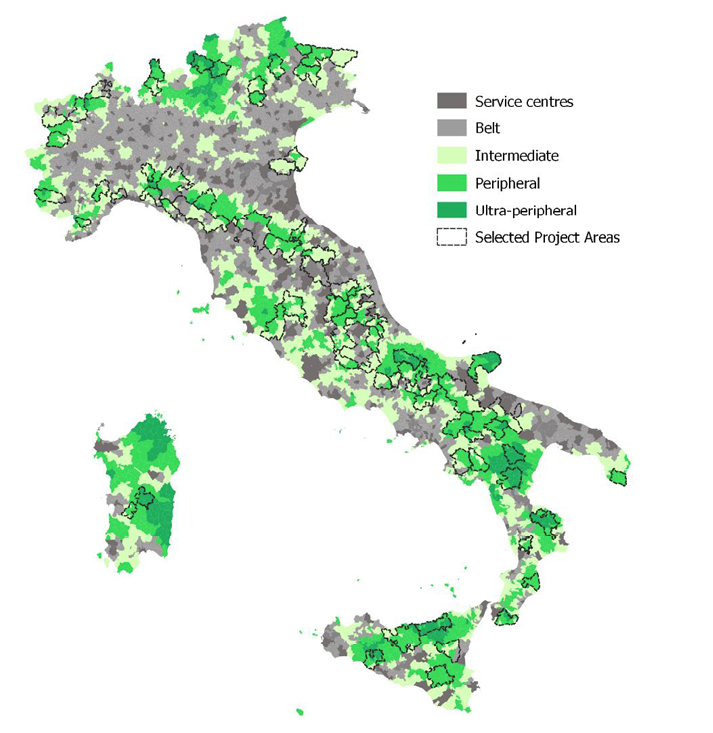

The selection of areas is based on a method defined by a central Technical Committee, drawing on a definition of ‘inner areas’ as territories that have limited or inadequate access to essential services.[5] Then, in line with the EU cohesion policy’s principle of concentration, a limited set of identified inner areas is selected as ‘project areas’, through a process of negotiation between the CTAI and each region. In total, 72 areas were selected (2 to 5 areas per region), comprising more than a thousand municipalities and home to more than 2 million people (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. The 72 areas targeted by the SNAI over the total of inner areas

Source: own work based on data provided by CTAI (the SNAI technical committee).

The SNAI method involves a number of key actors (different levels and sectors of public administration, associations, companies, service providers, etc.) in defining local development strategies for each area, which identify the guiding principles for territorial development and then translate those into objectives and concrete actions. Once a strategy is approved, a framework agreement is signed between the national bodies involved in the CTAI and respective regions, provinces and local authorities. The agreement contains specific interventions to be implemented, the implementing subjects, the financial resources and their respective sources, the time schedules, the expected results and result indicators, and the sanctions for non-compliance.

In the selected areas, the SNAI acts as a coordination platform between domestic (mainly national and regional) and European resources.[6] Its governance puts local actors (public administrations, the third sector, and private actors) at the heart of the process. More precisely, local authorities are asked to organise themselves into formal supra-local entities (e.g. Unions of Municipalities) aimed at the associated management of services. At the same time, the SNAI recognises the need for coordination and supervision by regional and national actors. The SNAI is, therefore, a multi-level, multi-actor and multi-fund process which, by combining top-down and bottom-up logics, recognises that the national level is the most suitable for the provision of the prerequisites for development (health, education, and mobility) and the local level as the best one for defining development potential. Examples of interventions aimed at the endowment of development prerequisites concern the reorganisation of the school offer with the creation of new schools in barycentric positions, the replacement and relocation of inefficient services spread throughout the territory, the reorganisation of the health offer to improve access to diagnostic and emergency services, and the adaptation and improvement of transport services also through flexible and innovative solutions (Barca et al., 2014). At the same time, local development projects are defined at the local level and financed mainly with European funds programmed at the regional level. They may concern various spheres and sectors (e.g. digital accessibility, economic development, social cohesion, energy efficiency and environmental protection, etc.) Among them, tourism plays a relevant role, as it will be further discussed below.

The SNAI explicitly recognises tourism as one of the main factors potentially underpinning territorial development, through the enhancement of local, often unexpressed potential. In particular, tourism is one of the five categories into which local development projects proposed by local actors in each area should fall,[7] namely: (i) active territorial/environmental sustainability protection, (ii) valorisation of natural/cultural capital and tourism, (iii) valorisation of agriculture and food systems, (iv) activation of renewable energy supply chains, and (v) know-how and crafts.

Through this selection, the SNAI framework acknowledges the extraordinary value of Italian inner areas’ biodiversity, and natural and cultural resources, as well as the dual nature of this diversity, both natural and man-made, with diverse linguistic, cultural, and traditional specificities, which are increasingly considered as key assets, opposed to the standardisation effect of globalisation. At the same time, it underlines the importance of combining market orientation, job creation and maintenance of heritage keeping a view to sustainability. To this end, natural tourism is suggested as a way to support place-based local development, creating alternative and integrative sources of income, and a greater awareness of territories that have much to offer but have long remained off the tourist map. A second keystone is the local cultural identity, which needs to be enhanced, and sometimes recovered.

Specific guidelines were provided by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism (MIBACT, 2016), aimed at the integration of tourism into SNAI local development strategies. These guidelines highlight a number of important elements that should be considered, such as the importance of the ‘industrial component’ of tourism, which needs specific skills, the natural hazards to which inner areas are exposed, that are also determined or worsened by deanthropisation, and external factors of economic instability, such as changing conditions of territorial competitiveness and changing consumer preferences.[8] The document also suggests to frame initiatives aimed at bolstering territorial development through tourism in a logical model combining different elements, such as: natural resources and architectural and cultural heritage; transport, infrastructures and accessibility; existing and potential offer; skills and competences of local operators; socio-economic conditions; governance and management; and the presence of production chains that contribute or have contributed to determining local identity.

According to MIBACT, “[t]he result must be the creation of an articulated product where, for example, not only a touristic route is designed, but the set of actions necessary for it to become a tourism product is proposed: intermodal services, reception, food and wine, luggage transport, and so on” (MIBACT, 2016, p. 4). At the same time, the guidelines also warn that tourism is not the panacea to tackle underdevelopment and marginalisation, and urge that the sector should not be seen as the only possible development alternative, since in many areas, despite being a relevant option, it often lacks the critical mass to serve as the cornerstone of local development. Therefore, a rigorous assessment must be made to decide whether or not an area has real potential for tourism development that justifies new investments. Aspects of governance and management are also recognised, urging local areas to seriously consider aspects such as the coordination of initiatives, animation and information dissemination, local promotion, and linkage with wide area (regional and national) planning and promotion.

Finally, the guidelines emphasize the importance of paying attention to the fact that activities and services related to the enjoyment of tourism can intercept and coincide with the needs expressed by the resident population (e.g. broadband availability or sustainable mobility infrastructure). The presence of demand from the resident population can in fact ensure greater financial sustainability for the proposed initiatives, but also open possible forms of partnership and support from sectors not directly related to the tourism supply chain.

When closely examining the SNAI’s 72 project areas, a number of common elements and peculiarities emerge in relation to how they encompass tourism as a leverage for development. First of all, it is possible to highlight a great differentiation between the areas in terms of tourist attractiveness, ranging from areas where tourism is already mature to areas with good tourism potential but rather modest flows (SNAI, 2018). More in detail, only six areas (all located in northern Italy, especially in the Alps) are classified as major tourist attractors, with more than 500,000 annual presences. Fifteen areas (mostly located in the centre-north, with two exceptions in the South, in Apulia) feature flows of more than 100,000 presences, while all other areas are characterised by lower values, with about a third having less than 20,000 presences per year. Overall, areas located in mountainous marginal and socio-economically fragile contexts display a more limited potential for tourism development than others. They also often suffer from poor visibility and connectivity, being excluded from territorial tourism supply systems and are not characterised by a defined tourism identity (Conti, 2018).

Regardless of the level of tourist attractiveness, a common trait of all the 72 area strategies is the attempt to organise a heterogeneous and articulated tourist offer, combining many of the segments classifiable under the common label of ‘sustainable tourism’ (or slow tourism). More specifically, one may witness the emergence of a differential offer aimed at conveying the authenticity of the area and the historical traditions in a simple way, with direct involvement of visitors in arts and craft activities (visits to artisan workshops that process agri-food goods, wood and leather, production of textiles, etc.) (SNAI 2018).[9]

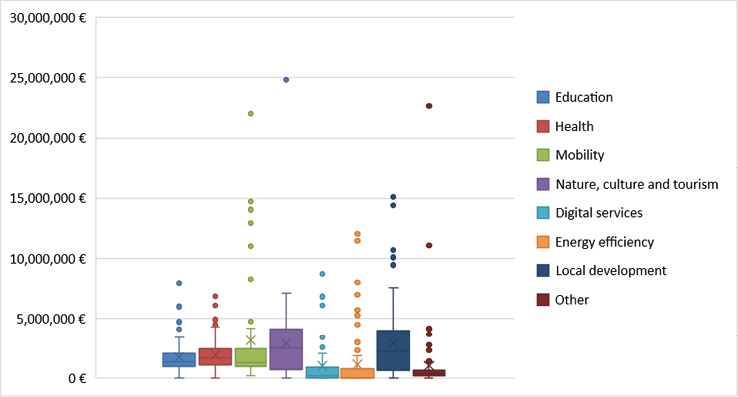

Tourism-related issues are also very relevant in terms of the budget: on average, they weigh 18% of the total budget for the area strategies, with values up to 56% (Fig. 2). Although all of the areas decided to invest in tourism, different approaches and intensities have emerged, also in relation to the existing levels of tourism development. For instance, some areas (especially in the centre-north of Italy), where tourism is already a key asset in the local economy, decided to further invest a high share of the total budgets of their respective strategies in this sector, while others decided to maximise investment in other sectors, considering the tourism sector as either already sufficiently covered by other funding programmes or dependent on other sectoral interventions to increase its potential (Cuccu and Silvestri, 2019; Bernabei, 2021). More in detail, as discussed by a number of interviewees, many remote rural areas have only limited tourism potential mostly related to the fruition of their natural resources and, in order to better exploit this potential, it would be more important to intervene in terms of accessibility of these areas as a whole and their digital interconnectedness (see also Vitale Brovarone and Cotella, 2020).

Fig. 2. Total budget of SNAI area strategies per category

Source: own work based on SNAI summaries of the financial allocation of framework program agreements.

Actions aimed at improving the touristic offer are listed in the “nature, culture and tourism” category, which in itself has a higher budget than education or health (11% and 12% respectively), and only slightly lower than transport and mobility (20%). The “nature, culture and tourism” category is directly related to tourism development, having as its main theme the enhancement of natural and cultural heritage and, as a result indicator, the objective to “Increase the number of tourist presences and visitors to the area’s cultural and natural heritage” (SNAI, 2018, p. 68).

However, as several local and national stakeholders have also highlighted, it must be noticed that the relevance of tourism in the SNAI is not only limited to this category. Actions that are inserted in other categories are also aimed at improving and increasing tourism. For instance, in the mobility category one of the main target groups are tourists, and a significant number of areas decided to invest in “slow mobility” (cycle and hiking routes) or in improving public transport on non-working days, to offer a better service to tourists (Vitale Brovarone, 2022). Other sectors with which the most frequent connections and interdependencies emerge are education and agriculture, with the aim of enriching the linguistic and digital skills of tourism workers and increasing the consumption of typical and traditional local food products (Bernabei, 2021).

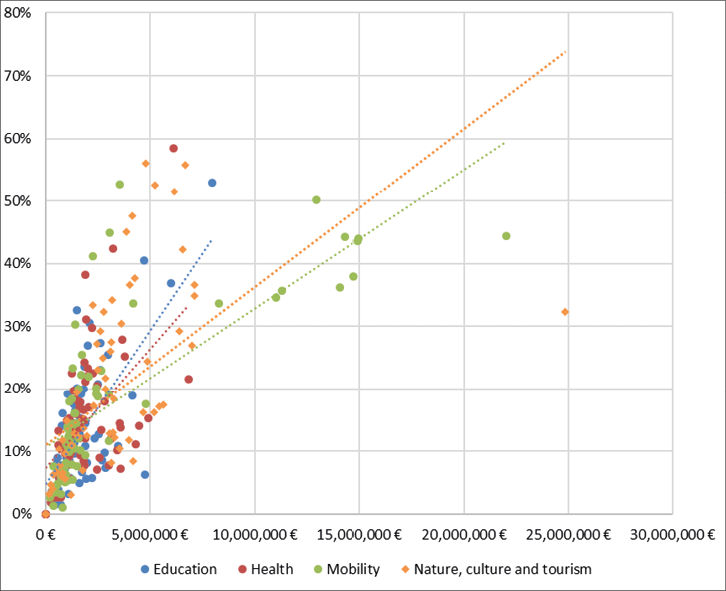

When exploring how tourism is dealt with in the 72 strategies, and how many resources it can use (Fig. 3 and 4), a number of interesting considerations may be formulated. For example, the “nature, culture and tourism” category shows a relatively high mid-spread (IQR) and a positive skew (Fig. 3). The mean and median values are very close (EUR 2.9 million and EUR 2.5 million, respectively), with more coherent values than the other categories (only one outlier, at EUR 25 million). These data confirms not only the absolute relevance of tourism in the SNAI, but also its significant and constant presence in all the areas, as a strategic leverage for local development.

Fig. 3. Distribution of financial allocation in the 72 areas, by category

Source: own work based on SNAI summaries of the financial allocation of framework program agreements.

The relevance of tourism is also clear in terms of distribution, as shown in the scatter chart presented in Fig. 4. In particular, beside the highest value of EUR 24.8 million, the concentration of values in the upper part of the chart shows that tourism plays a key role not only in absolute terms but especially in terms of percentage on the total budget of strategies. For instance, while for the “nature, culture and tourism” category there are many values above 30% and below EUR 10 million, for the mobility category, which on average has similar percentages to tourism, the highest percentages correspond to very high absolute values, related to infrastructural investments (mostly in southern areas, Vitale Brovarone, 2022).

Fig. 4. Absolute amounts and percentages of resources allocated to three essential services (health, education, and mobility) and tourism in the 72 areas, with linear trend lines

Source: own work based on SNAI summaries of the financial allocation of framework program agreements.

Overall, the 72 SNAI area strategies clearly show how rural spaces are no longer associated purely with agricultural commodity production but are seen as locations for the stimulation of new socio-economic activities, often incorporating tourism, leisure, speciality food production and consumption, etc. Instead of looking at tourism at a sector upon which to develop mono-dimensional development strategies, the peculiar multi-level and multi-fund nature of the SNAI architecture has allowed the various actors’ coalitions responsible for the local development strategies to think of tourism as explicitly linked to the economic, social, cultural, natural, and human structures of the localities in which it occurs. In so doing, the adopted strategies promote a highly integrated and sustainable approach to tourism, which aims at consolidating powerful network connections between social, cultural, economic, and environmental resources (Saxena et al., 2007). In addition, the multi-level governance that characterises the SNAI enables local rural actors to receive support and engage in a dialogue effectively with regional and national authorities, which is often very difficult due to limited opportunities and capacities for discussion. As argued by a representative of one project area during an interview, the SNAI process “[…] has mostly served a purpose so far: not only to encourage more constructive dialogue among local actors, but to gain access to a constructive dialogue with those in higher authority. There is no doubt that this will be a turning point for our area in the dialogue with the region and other institutions.” (authors’ own translation).

The paper analysed the extent to which tourism has been included in the Italian National Strategy for Inner Areas as one of the cornerstones of local development strategies aimed at reverting the marginalisation trends that very often concern remote rural areas. Overall, the SNAI represents an innovative approach to the governance of regional development in Europe (Cotella et al., 2021), as it complements the traditional EU approach pivoted on NUTS2 regions with a higher attention to intraregional disparities. In doing so, it aims at promoting the development of selected remote rural areas of the country through a multi-level, multi-fund and multi-actor approach that enables the development of local development strategies integrating multiple elements, among which tourism certainly plays a relevant role.

The case of Italy’s inner areas represents an interesting example of how areas that are not traditionally considered tourist destinations attempt to enhance their natural and cultural resources in order to untap their unexpressed potential. While areas featuring mature tourism used this occasion to renew their offers (focusing on new segments or on the de-seasonalisation of flows), for those aiming at entering the tourism market the SNAI offered the opportunity to better define the boundaries and goals, and to improve the quality of the offer (Bernabei, 2021). At the time of writing this paper, it is too early to attempt an analysis of the impact of the 72 strategies, as most of them have only reached the implementation phase last year and most interventions still have to be delivered on the ground. In the medium-long term, the main expected results are the improvement of the standards of the local heritage offer conditions and their placement on the tourism market as more competitive, recognisable, and attractive destinations.[10]

Importantly, when considering the area strategies and annual reports on the SNAI implementation, a number of criticalities emerge, which the Italian inner areas have encountered when planning their tourism development. First of all, the vision of tourism is often traditional and local actors find it hard to identify management and governance models suited to the characteristics of the local heritage. With regard to this, a number of interviews has have indicated how often the local coalitions proposed the creation of territorial brands for territories that, however, were not autonomous tourist destinations and lacked the strength, size, and critical mass to compete on a globalised market (see also Vanhove, 2010). In these cases, it would have been more profitable to focus on the integration in the closest regional tourist destinations, aiming at grafting into existing tourist organisations and gaining visibility within them. The same effort of interaction should be made with regard to other sectors (such as health, education, mobility, agriculture, etc.), favouring permanent effects of the consolidation of tourism development useful to rural development and connected to local and regional resources and communities (Bramwell, 1994; Saxena et al., 2007).

Overall, the analysis presented in this paper has shown that shifting from a mostly rural economy to a more tourism-oriented one is not an easy process, as it involves multiple aspects and sectors, and requires skills and capabilities that cannot be taken for granted (Salvatore et al., 2018; Mantegazzi et al., 2021; Rosalina et al., 2021). Until recently, tourism emerged as a relevant sector in the Italian peripheral areas through a hierarchical core-periphery model, which generated tourism enclaves serving as extended leisure resorts for urban hubs and metropolitan areas. It is only through the implementation of place-based, integrated development policies that focus on the emergence of new cultural trends that these areas could reconsider their positioning in the tourism offer. To this end, private and public actors should cooperate at all territorial levels and build partnerships aimed at resolving the conflicts between the desire for development and the protection of fragile environments and economies (Jamal and Getz, 1995; Roxas et al., 2020). In fact, the development of the SNAI’s local development strategies is indeed the result of a collaborative effort between the local administration, local actors, and stakeholders, with technical assistance, and with the support of the regional level and of the SNAI’s committee. The differential ability of the areas to adopt the advised place-based development approach contributes to explain why some places succeeded more than others in drawing their development options and will, in turn, influence the successful implementation of the strategies. Be that as it may, however, the innovative and inclusive approach that characterises the SNAI process had contributed to opening new spaces of possibility and paving the way for a bottom-up, place-based valorisation of local development potentials (Mantegazzi et al., 2021). This is particularly relevant when considering that the SNAI experience has been recently relaunched within the framework of the EU 2021–2027 programming period, in so doing enabling reflection and capitalisation on the experience matured so far and to incrementally solve the mentioned drawbacks.

ASSUMMA, V., BOTTERO, M., CASSATELLA, C. and COTELLA, G. (2022), ‘Spatial planning and sustainable tourism in UNESCO wine regions: the case of the Langhe-Roero and Monferrato (Italy)’, European Spatial Research and Policy, 29 (2), pp. 93–113. https://doi.org/10.18778/1231-1952.29.2.06

BACCI, E., COTELLA, G. and VITALE BROVARONE, E. (2022), ‘Improving Accessibility to Reverse Marginalisation Processes in Valle Arroscia, Italy’, Rural Accessibility in European Regions, Routledge.

BARCA, F., CASAVOLA, P. and LUCATELLI, S. (eds) (2014), ‘A strategy for Inner Areas in Italy: Definition, objectives, tools and governance’, Materiali UVAL Series [Preprint], 31), http://old2018.agenziacoesione.gov.it/opencms/export/sites/dps/it/documentazione/servizi/materiali_uval/Documenti/MUVAL_31_Aree_interne_ENG.pdf [accessed on: 03.06.2022].

BERNABEI, G. (2021), ‘I distretti turistici come opportunità di sviluppo per le aree interne’, Centro Ricerche Documentazione e Studi Ferrara, https://www.cdscultura.com/2021/07/i-distretti-turistici-come-opportunita-di-sviluppo-per-le-aree-interne/ [accessed on: 03.06.2022].

BOHLIN, M., BRANDT, D. and ELBE, J. (2020), ‘Spatial Concentration of Tourism – a Case of Urban Supremacy’, Tourism Planning & Development, pp. 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2020.1855239.

BRAMWELL, B. (1994), ‘Rural tourism and sustainable rural tourism’, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 2 (1–2), pp. 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669589409510679.

BROUDER, P. (2012), ‘Tourism Development Against the Odds: The Tenacity of Tourism in Rural Areas’, Tourism Planning & Development, 9 (4), pp. 333–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2012.726259

CAMARERO, L. and OLIVA, J. (2016), ‘Understanding Rural Change: Mobilities, Diversities, and Hybridizations’, Sociální studia/Social Studies, 13 (2), pp. 93–112. https://doi.org/10.5817/SOC2016-2-93.

CONTI, E. (2018), L’impatto del turismo sulle aree interne: potenzialità di sviluppo e indicazioni di policy, IRPET – Istituto Regionale della Programmazione Economica della Toscana.

COTELLA, G. (2019), ‘The Urban Dimension of EU Cohesion Policy’, [in:] E. MEDEIROS (ed.), Territorial Cohesion: The Urban Dimension, Cham: Springer International Publishing (The Urban Book Series), pp. 133–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-03386-6_7

COTELLA, G. (2020), ‘How Europe hits home? The impact of European Union policies on territorial governance and spatial planning’, Géocarrefour, 94(94/3). https://doi.org/10.4000/geocarrefour.15648

COTELLA, G., RIVOLIN, U. J., PEDE, E. and PIOLETTI, M. (2021), ‘Multi-level regional development governance: A European typology’, European Spatial Research and Policy, 28 (1), pp. 201–221. https://doi.org/10.18778/1231-1952.28.1.11

COTELLA, G. and DĄBROWSKI, M. (2021), ‘EU Cohesion Policy as a driver of Europeanisation: a comparative analysis’, [in:] RAUHUT, D., SIELKER, F. and HUMER, A. (eds.) EU Cohesion Policy and Spatial Governance, Edward Elgar, pp. 48–65. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781839103582.00013

COTELLA, G. and VITALE BROVARONE, E. (2020a), ‘La Strategia Nazionale per le Aree Interne: una svolta place-based per le politiche regionali in Italia’, Archivio di Studi Urbani e Regionali, 129, pp. 22–46. https://doi.org/10.3280/ASUR2020-129002

COTELLA, G. and VITALE BROVARONE, E. (2020b), ‘Questioning urbanisation models in the face of Covid-19’, TeMA - Journal of Land Use, Mobility and Environment, Special issue Covid-19 vs City-20, pp. 105–118. https://doi.org/10.6092/1970-9870/6913

COTELLA, G. and VITALE BROVARONE, E. (2020c), ‘The Italian National Strategy for Inner Areas: A Place-Based Approach to Regional Development’, [in:] J. BAŃSKI (ed.), Dilemmas of Regional and Local Development, Routledge, pp. 50–71.

COTELLA, G. and VITALE BROVARONE, E. (2021), ‘Rethinking urbanisation after COVID-19: what role for the EU cohesion policy?’, Town Planning Review, 92 (3), pp. 411–418. https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.2020.54

CUCCU, O. and SILVESTRI, F. (2019) ‘La Strategia Nazionale per le Aree Interne (SNAI) e la valorizzazione del patrimonio turistico per lo sviluppo locale’, Annali del turismo, VIII.

DEMATTEIS, G. (2009), ‘Polycentric urban regions in the Alpine space’, Urban Research & Practice, 2 (1), pp. 18–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/17535060902727017.

ESPON (2019), ESPON URRUC – Urban-Rural Connectivity in Non-Metropolitan Regions. Targeted Analysis. Annex 6 – Case study report. Province of Imperia- Valle Arroscia, Italy. ESPON EGTC. https://www.espon.eu/URRUC [accessed on: 03.06.2022].

FELICE, E. and LEPORE, A. (2017), ‘State intervention and economic growth in Southern Italy: the rise and fall of the «Cassa per il Mezzogiorno» (1950–1986)’, Business History, 59 (3), pp. 319–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2016.1174214

GALLENT, N. and GKARTZIOS, M. (2019), ‘Defining rurality and the scope of rural planning’, [in:] M. SCOTT, N. GALLENT, and M. GKARTZIOS (eds.), The Routledge Companion to Rural Planning. Routledge, pp. 17–27. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315102375-3

GALLENT, N. and TEWDWR-JONES, M. (2018), Rural Second Homes in Europe : Examining Housing Supply and Planning Control, Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315201979

GREFFE, X. (1994), ‘Is rural tourism a lever for economic and social development?’, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 2 (1–2), pp. 22–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669589409510681

HALFACREE, K. H. (1995), ‘Talking about rurality: Social representations of the rural as expressed by residents of six English parishes’, Journal of Rural Studies, 11 (1), pp. 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/0743-0167(94)00039-C

HALL, C. M. and BOYD, S. (2004), Nature-based Tourism in Peripheral Areas: Development or Disaster?, Aspects of Tourism, 21, Channel View Publications, p. 281.

HARRISON, J. and HELEY, J. (2015), ‘Governing beyond the metropolis: Placing the rural in city-region development’, Urban Studies, 52 (6), pp. 1113–1133. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098014532853

JAMAL, T. B. and GETZ, D. (1995), ‘Collaboration theory and community tourism planning’, Annals of Tourism Research, 22 (1), pp. 186–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(94)00067-3

KAUPPILA, P., SAARINEN, J. and LEINONEN, R. (2009), ‘Sustainable Tourism Planning and Regional Development in Peripheries: A Nordic View’, Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 9 (4), pp. 424–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250903175274

KAWULICH, B. B. (2005), ‘Participant observation as a data collection method’, Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung, 6 (2). https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-6.2.466

KÜPPER, P., KUNDOLF, S., METTENBERGER, T. and TUITJER, G. (2018), ‘Rural regeneration strategies for declining regions: trade-off between novelty and practicability’, European Planning Studies, 26 (2), pp. 229–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2017.1361583.

LEŚNIEWSKA-NAPIERAŁA, K., PIELESIAK, I. and COTELLA, G. (2022), ‘Foreword’, European Spatial Research and Policy, 29 (2), pp. 9–15. https://doi.org/10.18778/1231-1952.29.2.01

LUCA, C. de, TONDELLI, S. and ÅBERG, H. E. (2020), ‘The Covid-19 pandemic effects in rural areas’, TeMA - Journal of Land Use, Mobility and Environment, pp. 119–132. https://doi.org/10.6092/1970-9870/6844

MANTEGAZZI, D., PEZZI, M. G. and PUNZIANO, G. (2021), ‘Tourism Planning and Tourism Development in the Italian Inner Areas: Assessing Coherence in Policy-Making Strategies’, [in:] M. FERRANTE, O. FRITZ, and Ö. ÖNER (eds.), Regional Science Perspectives on Tourism and Hospitality, Cham: Springer International Publishing (Advances in Spatial Science), pp. 447–475. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-61274-0_22

MIBACT (2016), Ministero dei beni e delle attività culturali e del turismo: Linee Guida per la Strategia Nazionale per le Aree Interne, p. 21.

MÖLLER, P. and AMCOFF, J. (2018), ‘Tourism’s localised population effect in the rural areas of Sweden’, Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 18 (1), pp. 39–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2016.1259584

NGUYEN, V. H. and FUNCK, C. (2019), ‘Tourism’s Contribution to an Equal Income Distribution: Perspectives from Local Enterprises’, Tourism Planning & Development, 16 (6), pp. 637–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2018.1563564

OECD (2020), Policy Implications of Coronavirus Crisis for Rural Development

OLIVA, J. and CAMARERO, L. (2019), ‘Mobilities, accessibility and social justice’, [in:] The Routledge Companion to Rural Planning, Routledge.

ROFE, M. W. (2013), ‘Considering the Limits of Rural Place Making Opportunities: Rural Dystopias and Dark Tourism’, Landscape Research, 38 (2), pp. 262–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2012.694414

ROGERSON, C. M. and VAN DER MERWE, C. D. (2016), ‘Heritage tourism in the global South: Development impacts of the Cradle of Humankind World Heritage Site, South Africa’, Local Economy, 31 (1–2), pp. 234–248. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269094215614270

ROSALINA, P. D., DUPRE, K. and WANG, Y. (2021), ‘Rural tourism: A systematic literature review on definitions and challenges’, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 47, pp. 134–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.03.001

ROXAS, F. M. Y., RIVERA, J. P. R. and GUTIERREZ, E. L. M. (2020), ‘Mapping stakeholders’ roles in governing sustainable tourism destinations’, Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 45, pp. 387–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2020.09.005

RYE, J. F. (2006), ‘Rural youths’ images of the rural’, Journal of Rural Studies, 22 (4), pp. 409–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2006.01.005

SALVATORE, R., CHIODO, E. and FANTINI, A. (2018), ‘Tourism transition in peripheral rural areas: Theories, issues and strategies’, Annals of Tourism Research, 68, pp. 41–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2017.11.003

SAXENA, G. et al. (2007), ‘Conceptualizing Integrated Rural Tourism’, Tourism Geographies, 9 (4), pp. 347–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616680701647527

SCHMALLEGGER, D. and CARSON, D. (2010), ‘Is tourism just another staple? A new perspective on tourism in remote regions’, Current Issues in Tourism, 13 (3), pp. 201–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500903359152

SINGHANIA, O., SWAIN, S. K. and GEORGE, B. (2022), ‘Interdependence and complementarity between rural development and rural tourism: a bibliometric analysis’, Rural Society, pp. 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/10371656.2022.2062198.

SNAI (2018), Relazione annuale sulla Strategia Nazionale per le Aree Interne 2018. https://www.agenziacoesione.gov.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Relazione_CIPE_ARINT_311218.pdf [accessed on: 03.06.2022].

TULUMELLO, S., COTELLA, G. and OTHENGRAFEN, F. (2020), ‘Spatial planning and territorial governance in Southern Europe between economic crisis and austerity policies’, International Planning Studies, 25 (1), pp. 72–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563475.2019.1701422

URSO, G. (2016), ‘Polycentric Development Policies: A Reflection on the Italian “National Strategy for Inner Areas”’, Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 223, pp. 456–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.05.275

URSO, G. (2021), ‘Metropolisation and the challenge of rural-urban dichotomies’, Urban Geography, 42, pp. 37–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2020.1760536

VANHOVE, N. (2010), The Economics of Tourism Destinations. 2nd edition, London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780080969978

VITALE BROVARONE, E. (2022), ‘Accessibility and mobility in peripheral areas: a national place-based policy’, European Planning Studies, 30 (8), pp. 1444–1463. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2021.1894098

VITALE BROVARONE, E. and COTELLA, G. (2020), ‘Improving Rural Accessibility: A Multilayer Approach’, Sustainability, 12 (7), p. 2876. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072876

VITALE BROVARONE, E., COTELLA, G. and STARICCO, L. (eds.) (2022), Rural Accessibility in European Regions, New York: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003083740