Abstract. This article investigates the relationship between tourism-related economic activities and neighbourhood shops in the historical centre of Venice, in terms of both their spatial distribution and the conflictual uses of the city. In questioning how to inhabit and revitalise the city through commercial activities, the paper wishes to contribute to the discussion proposed in the special number, by presenting a specific yet paradigmatic context and by reflecting on urban regeneration and revitalisation bottom-up practices. The research first unfolds the landscapes of commerce in the city and identifies polarised geographies of tourism-related activities focusing on retail and catering businesses; secondly, it interrogates spatialised strategies that local actors are developing to reflect on their relation with urban planning and policy design processes.

Key words: Venice, commerce, neighbourhood shops, quality of urban spaces, urban regeneration.

Sustainable tourism planning practices inevitably deal with the need to balance multiple forces and needs (UNWTO, World Tourism Organization, 2018; Bertocchi et al., 2020; Fennell and Cooper, 2020). The protection and conservation of tangible and intangible assets (human, cultural, and natural) and the valorisation of (local) economies and socio-cultural capitals, imply a delicate activity of balancing human and non-human inhabitants of a territory with an alien population: tourists and tourism-related investments. Such a conflictual perspective, the ‘tragedy of tourism commons’ (Briassoulis, 2002; Holden, 2005) not only relates to the safeguarding of material and non-material resources but also regards the pursuit of economic growth and competitiveness of tourist destinations.

While the concept of ‘commons’ draws attention to the competition to access scarce resources, the relatively new concept of ‘overtourism’ (Ali, 2016; UNWTO, World Tourism Organization, 2018), has pointed attention to a raising wave of discontent that crosses cities overwhelmed and consumed by tourism. Overtourism certainly relates to the perception of locals being invaded by tourists as the raising anti-tourism movements and protests demonstrate (Goodwin, 2017; UNWTO, World Tourism Organization, 2018; Bertocchi and Visentin, 2019; Milano et al., 2019; Novy and Colomb, 2019; Séraphin et al., 2020). In this sense, there is an extensive conflict pervading those cities radically transformed by tourism that has produced a shared ‘tourismophobia’ (Milano, 2017).

Nevertheless, the conflictual narrative and binary oppositions between local inhabitants and tourists often express wider concerns related to city liveability: what is at stake is the right to the city of local inhabitants, and diverse city users, and their possibility to access urban resources and services, enjoy urban and tourism commons, and share the socio-economic benefits of tourist economy (Colomb and Novy, 2016; Bertocchi and Visentin, 2019; Novy and Colomb, 2019).

Following this assumption, policies that effectively address tourism can not only deal with it from a sectoral perspective, but they should move from an integrated vision that considers environmental, social and economic issues. Moreover, the role of local communities with sustainable planning practices becomes particularly relevant; their survival and their living standards should be the leading element of planning and design processes.

Furthermore, overtourism is strongly linked with the effective capacity of a place or a city to sustain a certain number of city users; in other words, there is a tourist carrying capacity that is an intrinsic characteristic of each territory and that determines a maximum level of tourism development (Canestrelli and Costa, 1991; Bertocchi and Visentin, 2019). For what regards ‘tourist-historic city’ (Ashworth and Tunbridge, 1990, p. 3) and local inhabitants, implications of overcoming the carrying capacity lay at the link between heritagisation, tourism, gentrification, and the displacement of pre-existing communities (Ashworth and Tunbridge, 1990; Novy and Colomb, 2019; López-Gay et al., 2021; Salerno, 2022). This link, intended as an outcome of a process of an extraction of an urban surplus part of an intentional political project, often results “in the production of the city-as-an-attraction, in which residents are progressively crowded-out by the tourism industry” (Salerno, 2022, p. 9).

In other words, focusing on the Venice case study, Salerno (ibidem) demonstrates that the political process of touristification in tourist cities is the result of long-term cultural, social, and territorial transformations for the benefit of private interests and it produces the expulsion of the local inhabitants from the historical city (gentrification). Displacement dynamics are particularly evident looking at the commercial and residential sectors (Colomb and Novy, 2016), both relevant indicators of changes happening in the demography, economy, and living standards of a city (Olm et al., 2012). The typology and the distribution of commercial activities are largely influenced by tourism flows, particularly in heritage cities; at the same time, those elements contribute to the complexity of urban life (Tamini, 2016; Limonta and Paris, 2019) that both tourists and local inhabitants experience.

The devastating effects of tourism regarding neighbourhood shops targeting tourists instead of stable inhabitants imply a loss of basic services and quality in the products (Russo, 2002; Salerno and Russo, 2022; Van Der Borg, 2022).

Following these considerations, and assuming that (i) there is a need for an integrated vision that (ii) includes bottom-up perspectives to effectively build a dialogue with local inhabitants, this contribution investigates the spatial distribution of tourism-related economic activities and bottom-up urban policies that address the survival of neighbourhood shops.

The aim is to explore the bottom-up strategies of survival and integrated urban policies that not only relate to commerce but a more complex perspective regarding urban life. The research focusses on a particularly fragile environment, i.e., the historical city of Venice, commonly assumed as a symbol of the devastating effects of tourism in heritage cities (Russo, 2002; Van Der Borg, 2017; Bertocchi and Visentin, 2019).

Within this exceptional “planetary kaleidoscope for all the dynamics that characterise the Anthropocene” (Iovino and Beggiora, 2021, p. 8), the extreme conflict between tourists and local inhabitants, the displacement dynamics happening in the commercial activities, caused by the overlapping of the alien population with other daily dynamics (Cocola-Gant, 2015; Van Der Borg, 2022) and the loss of stable inhabitants, impose policies that can regulate the distribution of the typology and the transformation of commercial activities to ensure both access for the stable population to basic services provided by neighbourhood shops and the survival of those neighbourhood shops within a tourist globalised economy.

To frame the relationship between tourism and commercial activities in Venice, the paper first explores Venice’s economy from a historical perspective and identifies three main phases leading to a process of commodification of the entire historical city and a monofunctional economy based on low-quality shops for tourists. The central section of the paper is divided into two main parts, the first exploring and presenting the contemporary distribution of activities, the second exploring two cases of bottom-up self-organisation within the city that exemplify sustainable strategies of survival for neighbourhood shops and local entrepreneurs. The discussion reviews the presented case studies in relation to urban planning and policy instruments and possible directions.

As they point to the need to foster local and regional supply chains, conclusions call for an integrated strategy and a coherent program of actions and policies that move from the opposition and the distinction between residents and visitors, “to consider instead how the population restructuring of central areas in contemporary cities could be the result of an assemblage of emerging forms of temporary dwelling, among which tourism is a powerful driver” (López-Gay et al., 2021, p. 2) and move from a regulatory perspective to the implementation of soft (Russo, 2002) and more pro-active trans-sectoral policies.

As briefly mentioned in the previous section, Venice is a paradigmatic case (Settis, 2014). Despite its unique and non-repeatable situation, it seems to concentrate and accelerate all the challenges that our (historical) cities are facing. Venice’s historical centre, as a limited but also iconic space, is an exceptional laboratory to discuss environmental conservation and protection, socio-economic development, and the safeguarding of existing local communities (Costa, 1993; Borelli and Busacca, 2020). Furthermore, the historical city has a distinctive relationship with its periphery and with the transformations of the urban form; this relationship has evolved towards a conservatory approach to the historical city and has resulted in both the expulsion of inhabitants and productive functions to the mainland, and a growth of a tourism monoculture (Salerno, 2018).

The transition towards a tourism-based economy in Venice has been largely addressed and criticised in terms of depopulation and the expulsion of inhabitants from the city (see, for example, Borelli and Busacca, 2020; Salerno, 2018, 2020, 2022; Salerno and Russo, 2022; Zanardi, 2020; Settis, 2014). The causes are a complex and interrelated system that is hardly separable without looking at a historical perspective and at the long (political) project that commodified the city and tied its future.

Such an intentional process of touristification or museumification (Salerno, 2018) has resulted in intense demographic changes and severe overtourism, or hyper-touristification (Costa and Martinotti, 2003; Van Der Borg, 2017). The severe overtourism and the friction between diverse users are exacerbated by the morphology of the city itself, which makes it impossible to move fluxes and infrastructures out of the city (Bertocchi et al., 2020).

While the debate is ongoing and the city experiments with unprecedented approaches to overtourism (Bertocchi and Camatti, 2022; Hughes, 2022b), this section focuses on the spatial effects of this phenomenon in the economic geography of the city. Numerous scholars have given specific attention to the distribution of commercial activities within the historical city of Venice and the transformation process that has resulted in what Salerno defined as “a Fordist standardization of low quality Disneyfied shops [that] smoothly coexists alongside expanding luxury commerce, both at the expense of local-oriented and neighbourhood shops” (Salerno, 2022, p. 6). This section marks three relevant steps that explain the evolution of commercial activities and point to the growing conflict between diverse types of activities.

Firstly, already in the 1980s, services directed to the resident population decreased (from 46.9% in 1971 to 37.7% in 1981) while bars and tourist shops spread (Andreozzi et al., 1983). Despite that the same research also stated that the growing competition with residential uses was not only related to tourism but also to other kinds of services and enterprises that occupied the limited space of the city. In other words, there was an overall growth of the service sector that subtracted space for residents (e.g., transformation of apartments into offices and studios). Such a shift was also related to a huge shift in the economy of the city: while it was first based on the production and circulation of material goods, in the 1980s it moved towards an economy based on cultural information (IRSEV, COSES, Comune di Venezia, Assessorato all’urbanistica, 1990).

Secondly, at the beginning of the 1990s, it became evident that there was an ongoing process of delocalisation of private offices and studios toward peripheral parts of the historical city. Moreover, while central districts started to be severely transformed by tourism (Dorsoduro, San Polo, Santa Croce), commercial zones within more residential districts (Giudecca, Cannaregio, Castello Est) appeared impoverished and incapable of innovating themselves (IRSEV, COSES, Comune di Venezia, Assessorato all’urbanistica, 1990; COSES, 1996). In the following decade, a city-funded study about the shopping habits of Venetian families also showed the impoverishment of small distribution and neighbourhood shops, compensated by supermarkets and higher mobility of consumers, who also moved to the mainland; yet, traditional shops kept their niche in the shopping habits of some Venetian families (Pedenzini and Scaramuzzi, 1997).

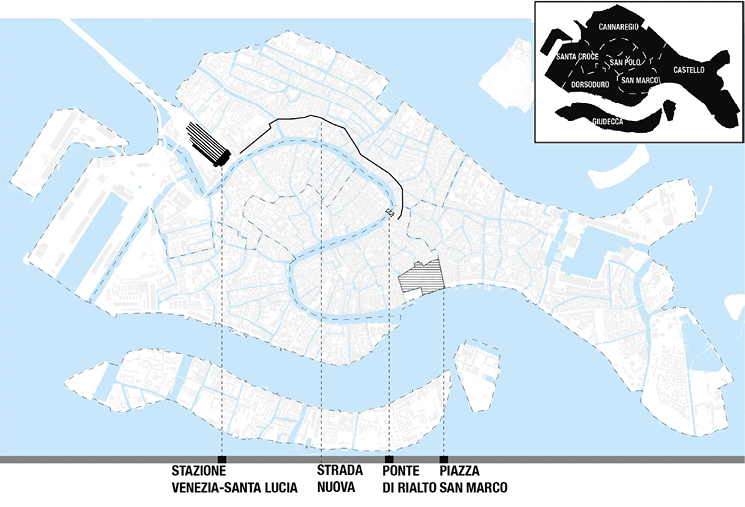

The third step that marks the evolution of the economic geography of the historical city emerged in the new century. According to Olm et al. (2012) and Zanini et al. (2008), the number and types of stores in Venice changed significantly between 1976 and 2007, and the number of stores catering to tourists increased dramatically: from 303 to 997, a total incremental variation of 694 units meaning by 229%. Oppositely, the number of grocery stores and other stores reduced significantly, moving from 720 units to 276, with a variation of –444 units (61.67%). Commercial activities (retail) were rapidly expanding throughout the city. Despite that the increment concentrated in specific pathways, such as Strada Nuova, leaving apart marginal areas, such as Castello (Fig. 1) and concerned specific categories of shops (Zanini et al., 2008).

A new set of categories is needed to describe Venetian tourists shops (Lando and Zanini, 2008; Zanini et al., 2008; Olm et al., 2012), even though, in some cases, it is hard to acutely distinguish between shops and services entirely dedicated to tourists or residents, both in Venice and elsewhere (Andreozzi et al., 1983; Azevedo and Melo, 2021).

On the one hand, there are “banal shops”, a category that includes mass-produced souvenirs, common paintings and sketches, and all the items sold by street vendors (excluding clothes); those products feature both low price and quality, and even though they are considered to be Venetian specialities, the products, in reality, have no relationship to local production or craftsmanship and have no artistic value. Confirming general tendencies in tourist shops, Zanini et al. (2008) have underlined that from 1976 to 2007 the number of banal shops increased by 265% throughout the city; in 2007, 538 units out of 694 (total incremental variation) were dedicated to “banal” articles.

On the other, though, “traditional tourist stores” include antique dealers, art galleries, and traditional, high-quality Venetian products such as masks, lace, and Murano glass. From 1976 to 2007 the number of traditional tourist shops increased by 156% (from 56 to 122 units) throughout the city. The growth mainly related to new traditional Venetian products rather than to traditional craftworks, antiques or art galleries (Zanini et al., 2008).

Based on the open data provided by the Municipality of Venice, and assuming the persistence of the trends noted by Zanini et al. (2008), a recent study about sustainable tourism in Venice (Bertocchi and Visentin, 2019), compared data from 2008 and 2019. The research, briefly focusing on commercial activities, highlighted a modest increase in the number of stores (from 2,605 to 2,705, meaning an increase by 4%); yet there have been visible transformations regarding the proliferation of restaurants, pizzerias and ice-cream shops, and of sunglasses and clothes stores, especially along the routes towards the central zone (Rialto, San Marco). Those activities address the needs of both tourists and commuters; in addition to that, there is a tendency to transform former inns and shops or small warehouses located on the ground floors into food service activities.

Fig. 1. The historical city of Venice, Sestieri and main touristic attractions and routes

Source: own work.

Existing literature has provided evidence regarding (i) the transition towards an economy based on tourism, (ii) the impoverishment of small distribution and neighbourhood shops, the increase of services directed to tourists parallel, and, oppositely the subtraction of spaces and services to the stable population, (iii) a general decrease in the quality of products sold to tourists, accompanied by a loss of stores dedicated to traditional Venetian products. To explore the unfolding of commercial activities in the historical city nowadays and mainly focusing on tourist shops, the following data uses the database provided by the Chamber of Commerce Venezia-Rovigo, Office for Communication and Statistics. The RAE (Registro attività economiche) dataset includes information regarding all the economic activities registered in the Municipality of Venice on 31 January 2021, both company headquarters and local business units.

The activities located in the main island of Venice (Cannareggio, Castello, Dorsoduro, Santa Croce, San Polo, Giudecca) have been selected for this research and spatialised by using georeferencing tools, with the support of the technical office of IUAV University. Geolocation activities have been possible by interrelating the address registered in the database and the street directory shapefile provided by the city of Venice, through ArcGis georeferencing tools.

The following analysis is based on the ATECO 2007 classification of economic activities, which is the Italian application of the European Classification of Economic Activities NACE. Within the dataset provided by the Chamber of Commerce, each activity can be described by multiple codes including diverse typologies of activity, e.g., a café selling books or a tobacco shop selling children’s toys or souvenirs. Any business can autonomously select the main business activity sector, a secondary one, etc. Within this research, only the main business activity sector has been analysed.

Moreover, considering studies about tourism and retail in Venice, this research uses two specific typologies of retail as proxies to describe shops’ targets (tourists or residents) and the quality of the products sold in Venice: artisanal goods or low-quality/banal shops. According to the ATECO classification, the first refers to the retail sale of handicrafts, and the second to the retail sale of trinkets and costume jewellery (including souvenirs and advertising items).

The database provided by the Chamber of Commerce Venezia-Rovigo is a complete source, as it includes all the economic activities registered in the city of Venice, their official activity sectors and their locations. However, according to the Chamber of Commerce Venezia-Rovigo, it does not allow a comparison of spatialised data over time; this should be conducted by further research, comparing the new dataset each year.

While the mapping of economic activities highlights specific configurations and concentrations, due to the timeframe of the analysis, it does not allow further elaborations on trends or spatial transformations towards specific business activity sectors, resulting in a limited interpretative tool of the ongoing dynamics. To better represent the complexity and the effective forces at work in the historical city, interviews with selected stakeholders (trade associations and business owners) have been conducted.

There were 10,232 business activities registered in Venice on 31 January 2021 (Fig. 2). This number refers to a wide range of activities including the third sector (Table 1). The wholesale and retail sector represent a more consistent category (31.07%), accommodation and food services represent more than 30% of the economic activities. More specifically, within the category of “Wholesale and retail trade; repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles,” retail is the most prevalent one (2,876 units). Transportation and storage and real estate activities follow with 6.62% and 6.50%, respectively.

Nevertheless, retail, food services and accommodations represent the most prevalent sectors of economic activity (Table 2): with a total number of 5,970 activities, they represent more than 58% of all the economic activities within the city.

| Class of activity | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 65 | 0.64 |

| Manufacturing | 566 | 5.53 |

| Electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply | 6 | 0.06 |

| Water supply; sewerage, waste management and remediation activities | 20 | 0.20 |

| Construction | 413 | 4.04 |

| Wholesale and retail trade; repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles | 3179 | 31.07 |

| Transportation and storage | 677 | 6.62 |

| Accommodation and food service activities | 3094 | 30.24 |

| Information and communication | 199 | 1.94 |

| Financial and insurance activities | 202 | 1.97 |

| Real estate activities | 665 | 6.50 |

| Professional, scientific and technical activities | 371 | 3.63 |

| Administrative and support service activities | 307 | 3.00 |

| Education | 44 | 0.43 |

| Human health and social work activities | 23 | 0.22 |

| Arts, entertainment and recreation | 183 | 1.79 |

| Other service activities | 218 | 2.13 |

| TOTAL | 10232 | 100.00 |

| Type of activity | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

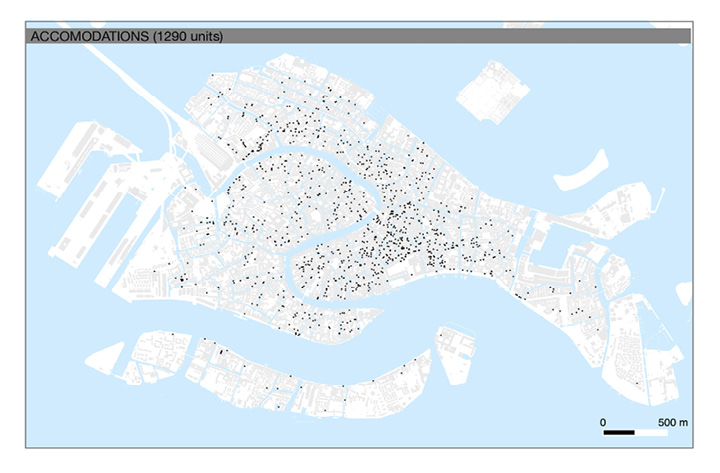

| Accommodations (hotels, B&B, other) | 1290 | 12.61 |

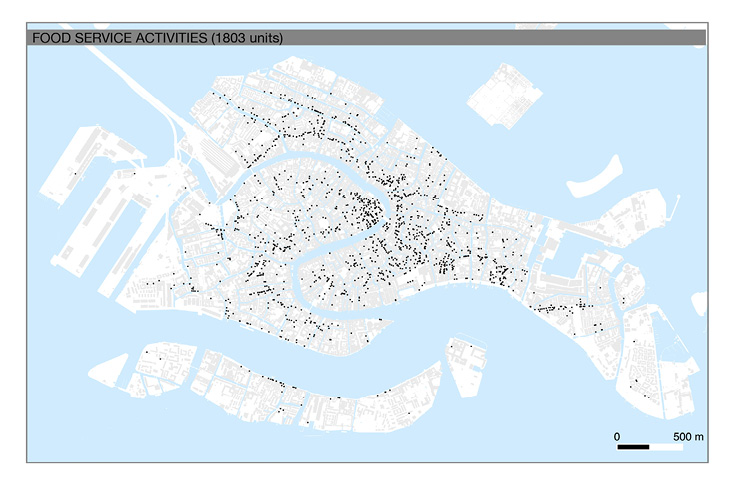

| Food service activities | 1804 | 17.63 |

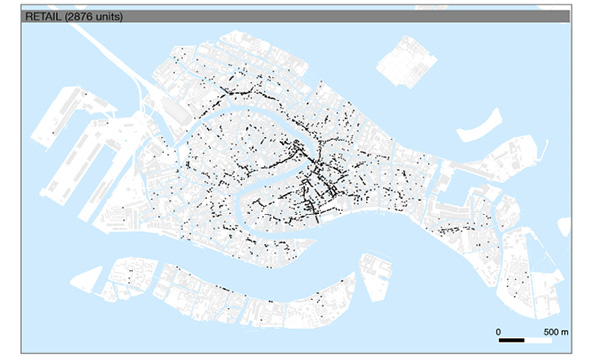

| Retail | 2876 | 28.11 |

| TOTAL | 5970 | 58.35 |

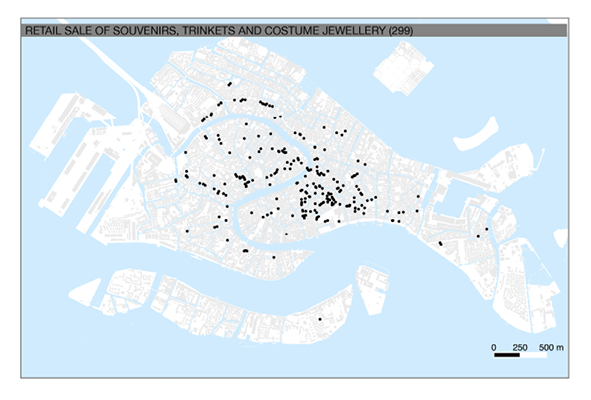

The prevalence of retail activities is evident; to delve deeper into this data, some specific categories were used as indicators of the quality of goods sold in Venice. Within retail (Table 3), shops selling trinkets and souvenirs – herein assumed as proxies of low-quality goods – represent 2.93% of the entire economic activity. Moreover, retail sale of souvenirs, trinkets and costume jewellery represents 10.40% of all retail activities; to compare: retail sale of food, beverages and tobacco in specialised and non-specialised stores (such as supermarkets) represent 13.94% of retail activities. Shops selling artisanal goods (retail sale of craftwork) represent 4.90% of all retail activities.

| Type of Activity | Number |

|---|---|

| Retail | 2876 |

| 1. Retail sale of craftwork | 141 |

| 2. Retail sale of souvenirs, trinkets and costume jewellery | 299 |

Retail, accommodations and food service activities constitute the economic backbone of the historical city of Venice. Furthermore, the amount of souvenir shops indicates a strong prevalence of retail shops targeting tourists; this data, compared to the number of shops selling craftwork, suggests the already mentioned tendency to sell lower quality goods.

The distribution of those activities around the city shows a tendency to concentrate within specific paths and areas. Hotels, B&B and other accommodations (that includes private apartments rented to tourists) are scattered around the city (Fig. 2). Foodservice activities, concentrate along certain routes and clusters, with growing intensity in the area around the Rialto Bridge and the Sestiere San Marco. In addition to that, food service activities also highlight axes that were not considered traditional touristic areas (e.g., the northern insulae of Cannaregio and the eastern part of Castello (via Garibaldi) (Fig. 3).

The retail sector shows a concentration along several axes, corresponding to what are the main touristic routes: as in the above-mentioned studies, Strada Nuova in Cannaregio, Sestiere San Marco and the area surrounding the Rialto Bridge, emerge as the commercial axes of the historical city. Other commercial districts are distributed along what were considered traditionally residential areas – Giudecca, Cannaregio, Castello Est (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2. Accommodations in the historical city of Venice

Source: own work, based on data by the Chamber of Commerce VE RO (January 2021

Fig. 3. Food Service Activities in the historical city of Venice

Source: own work, based on data by the Chamber of Commerce VE RO (January 2021).

Fig. 4. Retail in the historical city of Venice

Source: own work, based on data by the Chamber of Commerce VE RO (January 2021).

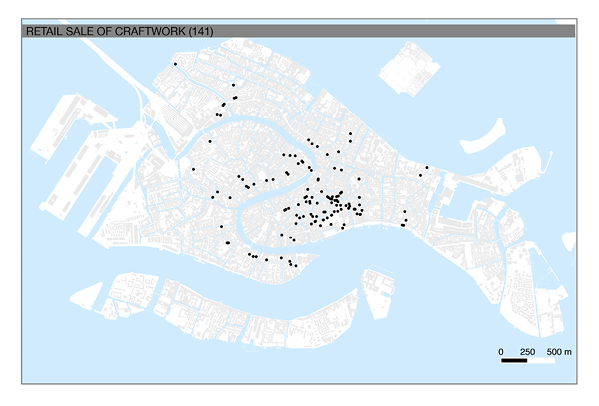

Comparing this geography with the distribution of shops selling souvenirs (Fig. 5) and craftwork (Fig 6), – the former are mainly distributed in the central area of the historical city, the latter concentrated in the areas of San Marco, San Polo and Dorsoduro) – the maps reinforce the hypothesis that some areas are still excluded from the main tourists’ routes and paths and the touristification of commercial activities, in particular the northern part of Cannareggio and some portions of Castello.

Fig. 5 Retail sale of souvenirs (299)

Source: own work based on data by the Chamber of Commerce VE RO (January 2021).

Fig. 6. Retail sale of craftwork (141)

Source: own work based on data by the Chamber of Commerce VE RO (January 2021).

Confirming the literature presented in section 2, the mapping operation highlights a prevalence of activities directed to tourists and the high number of low-quality retail shops selling souvenirs. Yet, due to the timeframe of the analysis, it does not allow any further elaboration on trends and spatial transformations towards specific activity sectors.

To complement the quantitative analysis interviews with selected stakeholders have been conducted. Interviews with representatives of trade associations and business owners draw the attention to:

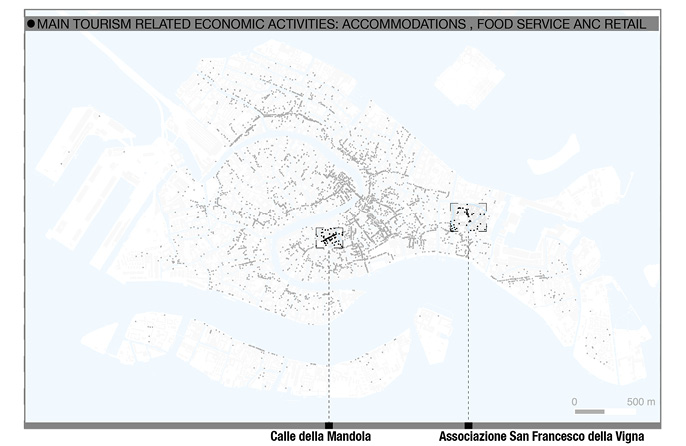

Leaving apart the actions and the policies of public and cultural institutions, this contribution will focus on the bottom-up networking initiatives to question the possible interactions between the forms of active citizenship and urban policies. The following paragraphs present two selected case studies, the enterprise network of San Francesco della Vigna and the experience of Calle della Mandola (Fig. 7); both cases emphasise the claim of business owners to reshape the interaction between local business owners and neighbourhood shops and the tourist system not just to resist overtourism but also to collectively benefit from the tourists flows.

Fig. 7. Selected case studies and main tourism-related economic activities

Source: own work, based on data from the Chamber of Commerce VE RO (January 2021).

The area of San Francesco Della Vigna is in the northeast of Castello and it has for a long time been considered far from the touristification processes as they invest more in the central zones.

An association of retail owners was born in 1998, to sustain local shops and preserve the local culture and traditions. Most of the shops in that area are still providing goods and services for local inhabitants: among the 15 shops that compose nowadays the association there are a hardware store, a sewing store, a grocery store, and a butcher’s. Most of them are rented spaces and only a few shop owners also own the space. The network of retail and other commercial activities (artisans and bars) spreads along the three salizada (streets, in Venetian) and it actively acts to build a shared image of the neighbourhood. This active work consists of a small-scale branding operation: a series of events (open street market), the illumination of the streets during Christmas celebrations, and shared packaging that all the shops distribute to clients (mainly consisting of branded bags), as well as organising temporary and mobile exhibitions . The actions aim to foster a coherent and recognisable image of the area.

The main aim of the organisation is a branding and marketing project, intended to help local shops stay on the market, be competitive, and innovate their communication strategies, with a shared project. The association does not explicitly react against overtourism; instead, the strategy it has proposed is based on building an interaction to contrast the perceived severe desertification of commercial spaces and the loss of spaces dedicated to social activities and relations.

Formally, the association is a network of enterprises, regulated within Italian law (l. 122/2010): the enterprises network agreement formalises alliances between entrepreneurs to enhance individual or collective innovation capabilities and competitiveness. The association is based on participant commitment to cooperate in the management of their enterprises and collaborate in the management of certain activities (Cardoni and Tiacci, 2013).

In San Francesco della Vigna, the agreement supports local commercial activities in preventing them from being closed and preventing the opening of new banal shops, bypassing both the role of official trade associations and the local government. According to the interviews, the former are perceived as incapable of listening to local instances and/or effectively negotiating with public authorities and balancing the needs of smaller entrepreneurs versus more powerful ones. Moreover, they are too sectorial, while, in this case, the need was to work on a (micro) territorial scale, cooperating despite the ATECO category. The latter – the local government and its public policies – are generally perceived as not trustworthy, incapable of protecting and providing effective responses to the vanishing both of residents and neighbourhood shops.

The network of enterprises provides an alternative by building relations between neighbourhood shops and relevant local institutions (such as the Venice Biennale), proposing local shops as their main suppliers and, thus, suggesting the possibility of constructing local supply chains as a tool for resistance.

Calle della Mandola is located in the Sestiere San Marco, within the main commercial district, densely populated by all kinds of city users. According to the interviewed (Venetian) retail owners, the commercial street and its surroundings are quickly converting to banal shops, losing high-quality retail and artisan outlets.

The retail network is centred around the owner of a high-quality bookshop, selling rare books, art pieces and other antique goods to local and international clients and collectors. Contrasting the opening of banal shops and in collaboration with other young entrepreneurs, he started colonizing the street: renting (four) new retail spaces and opening new shops (similar to the representative of the San Francesco della Vigna association). His action, described as an attempt to preserve the quality of the shops and of the retail offer to preserve the quality of the city, is strictly linked with the need of attracting high-quality customers. As in the case of San Francesco della Vigna, the activity is not intended to protect against overtourism, but it rather focusses on a more integrated system that includes both residents and tourists.

The process of transformation of the street and the attempt to protect Venetian business owners gained attention in October 2021 when an owner of a retail space (the ‘owner of the walls,’ as Venetians call landlords) decided to rent it to an Asian businessman who offered more than the bookseller. This raised awareness and promoted a public call for a protectionist policy towards Venetian retailers, accompanied by posters that spread around the neighbour.

Despite the mediatic debate and the political voices raised around this event, some elements and issues proposed by the long-term retailers of Calle della Mandola should be indicated:

Despite the challenges and threats of this approach, this proposal is directed towards an integrated urban and management model similar to the town centre retail districts (Morandi, 2011).

Within the historical city of Venice, the prevailing economic activities are retail, food service activities, and accommodation; in total, they represent more than half of the business activities in the area. More specifically, within retail, even though it is hard to acurately distinguish between stores targeting tourists, the amount of retail sale of souvenirs, trinkets, and costume jewellery – representing 10.40% of all retail – suggests a strong prevalence of stores catering to tourists, particularly if compared with the amount of retail sale of food, beverages and tobacco in specialised stores and non-specialised stores (including supermarkets), which represents about the 14% of retail. Also, the retail of craftwork is less than half of the retail sale of souvenirs.

In line with the literature, the analysis has shown the prevalence of shops targeting tourists instead of the local stable population, and the pervasiveness of banal shops selling low-quality goods with little relation to the local craftwork or artisanal activities. Indirectly, the data indicates that there has been a loss of basic services and quality in the products that amplifies the expulsion of local inhabitants. This is strongly evident with specific routes and paths, concentrating tourist-related activities along tourists’ paths and routes. Yet, the banalisation process of Venice’s urban life spreads all along the historic city.

In this sense, looking at the competition between local inhabitants and tourists to access scarce resources, the devastating effects of tourism regarding neighbourhood shops are already there. The current debate on overtourism, as much as urban policies proposing a fee to enter the historic city (Hughes, 2022b, 2022a), only seems to exacerbate the conflict and increase tourismophobia among certain groups of residents.

In their attempt to overcome such competition, the studied cases of San Francesco della Vigna and Calle della Mandola, even though located in diverse micro-contexts and acting with diverse premises, show a proactive milieu of entrepreneurs networking to survive in the historical city.

In San Francesco della Vigna the branding strategy aims to sustain neighbourhood shops by creating interactions and allowing their temporary appropriation of public space through events and shared visual identity. In this sense, the enterprise network aims at providing services to both residents and tourists and, by doing so, it contributes to the complexity of urban life in the neighbourhood. The formalised network represents a cooperative and flexible tool that businesses can use to provide shared services and undertake shared actions.

In Calle della Mandola, the call for neighbourhood retail districts refers to a specific season of (Italian) public policies to promote urban historical centres by enhancing neighbourhoods’ atmosphere and (physical) spaces, integrating measures that supported retail into urban planning tools and instruments (Morandi, 2011; Giorgio and Vigilante, 2018).

While the city of Venice has already implemented a retail district in the mainland (Mestre), within the historical city, ongoing policies refer to (i) the regional programme to support historical retail, (ii) regulations forbidding the transformation of specific retail categories or food-services activities, and (iii) municipal calls for the opening of artisanal and/or retail activities, by reusing empty spaces owned by the city. This last group of interventions suggests a more experimental approach towards public policies addressing retail; yet, by implementing targeted interventions, it might sustain a conservative approach aimed at preserving a sense of authenticity that does not solve issues related to overtourism in the retail sector.

To conclude, focusing on commercial activities, the competition between residents and tourists strongly relates to the types of activities and goods sold. In the historical city of Venice, the number of accommodation and food service activities, and – within retail – the activities selling souvenirs compared to food and beverage retail confirms a well-known trend: the transformation of neighbourhood shops and other services addressing resident needs to tourism-related activities (COSES, 2001; Zanini et al., 2008; Olm et al., 2012).

Such a process of transformation relates in Venice to the production of a city-as-an-attraction, which exacerbates conflicts among diverse populations using and inhabiting the city. The inclusion of bottom-up perspectives could, then, suggest alternative ways of action to start a dialogue between residents and public administrations. The presented case studies, although at different stages of implementation, are attempts to build a clear strategy and a coherent program to avoid the expulsion of neighbourhood shops addressing the needs of local inhabitants or their economies. They call for an integrated set of policies that involves multiple actors and not only uses soft instruments but combines physical, economic and communicative tools and interventions for neighbourhood shops and local economic activities to survive within the tourist industry.

In addition to that, the enterprise network of Fan Francesco della Vigna also suggests an additional path: the construction of local supply chains with major cultural institutions acting in the historical city represents a powerful tool that does not refer to any romantic view of localism but to share socio-economic benefits of the tourist economy.

Acknowledgments: This research was funded by IUAV University of Venice, within the research programme “Abitare Venezia/Abitare a Venezia.”

ALI, R. (2016), ‘Exploring the Coming Perils of Overtourism’, Skift [Preprint], 23-08-2016, https://skift.com/2016/08/23/exploring-the-coming-perils-of-overtourism/ [accessed on: 20.07.2022].

ANDREOZZI, D., JOGAN, I. and SBETTI, F. (1983), Patrimonio non residenziale 1971–1981, Venezia: IUAV Daest (DAEST- Osservatorio sul sistema abitativo del Centro Storico di Venezia).

ASHWORTH, G. J. and TUNBRIDGE, J. E. (1990), The Tourist-Historic City, London: Belhaven.

AZEVEDO, D. and MELO, A. (2021), ‘The impact of Covid-19 in restaurants – Take away and delivery, the consumer’s perspective’, [in:] SILVA, C., OLIVEIRA, M. and SILVA, S. (eds) Proceedings of 4th International Conference on Tourism Research. 4th International Conference on Tourism Research, Porto: Academic Publishing, pp. 61–68. https://doi.org/10.34190/IRT.21.051

BERTOCCHI, D. and CAMATTI, N. (2022), ‘Tourism in Venice: mapping overtourism and exploring solutions’, A Research Agenda for Urban Tourism, pp. 107–125. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781789907407.00013

BERTOCCHI, D., CAMATTI, N. and VAN DER BORG, J. (2020), ‘Turismo a Venezia: Mappare l’Overtourism ed Esplorare Soluzioni’, [in:] BORELLI, G. and BUSACCA, M. (eds.) Venezia: L’Istituzione Immaginaria della Società, Soveria Mannelli: Rubbettino, pp. 41–55.

BERTOCCHI, D. and VISENTIN, F. (2019), ‘«The Overwhelmed City»: Physical and Social Over-Capacities of Global Tourism in Venice’, Sustainability, 11, 6937. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11246937

BORELLI, G. and BUSACCA, M. (eds.) (2020), Venezia: L’Istituzione Immaginaria della Società, Soveria Mannelli: Rubbettino.

BRIASSOULIS, H. (2002), ‘Sustainable tourism and the question of the commons’, Annals of Tourism Research, 29 (4), pp. 1065–1085. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(02)00021-X

CANESTRELLI, E. and COSTA, P. (1991), ‘Tourist carrying capacity: A fuzzy approach’, Annals of Tourism Research, 18 (2), pp. 295–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(91)90010-9

CARDONI, A. and TIACCI, L. (2013), ‘The «Enterprises’ Network Agreement»: The Italian Way to Stimulate Reindustrialization for Entrepreneurial and Economic Development of SMEs’, [in:] CAMARINHA-MATOS, L. M. and SCHERER, R. J. (eds.), Collaborative Systems for Reindustrialization, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer (IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology), pp. 471–480. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-40543-3_50

COCOLA-GANT, A. (2015), ‘Tourism and commercial gentrification’, Proceedings of the RC21 International Conference on “The Ideal City: Between Myth and Reality, Representations, Policies, Contradictions and Challenges for Tomorrow’s Urban Life”, Urbino, Italy, 27–29 August 2015.

COLOMB, C. and NOVY, J. (eds.) (2016), Protest and Resistance in the Tourist City, London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315719306

COSES (1996), Alfabeto veneziano 1996: economia e societa nell’area metropolitana veneta, Bologna: il Mulino.

COSES (2001), ‘Programmazione commerciale per il centro storico di Venezia. Relazione tecnica. Doc.353.’

COSTA, N. and MARTINOTTI, G. (2003), ‘Sociological Theories of Tourism and Regulation Theory’, [in:] HOFFMAN, L. M., FEINSTEIN, S. S. and JUDD, D. R., Cities and Visitors. Regulating People, Markets and City Space, Malden: Blackwell, pp. 53–71.

COSTA, P. (1993), Venezia : economia e analisi urbana, Venezia economia e analisi urbana, Milano: ETAS libri.

FENNELL, D. A. and COOPER, C. (2020), Sustainable tourism: Principles, contexts and practices. Sustainable Tourism: Principles, Contexts and Practices, Channel View Publications, p. 504. https://doi.org/10.21832/FENNEL7666

GIORGIO, A. and VIGILANTE, M. (2018), I distretti urbani del commercio: nuove prospettive di governance della città. Cacucci (Quaderni CIRPAS).

GOODWIN, H. (2017), ‘The Challenge of Overtourism’, Responsible Tourism Partnership Working Paper 4. [Preprint]. http://www.millennium-destinations.com/uploads/4/1/9/7/41979675/rtpwp4overtourism012017.pdf [accessed on: 3.07.2022].

HOLDEN, A. (2005), ‘Tourism, CPRs and Environmental Ethics’, Annals of Tourism Research, 32 (3), pp. 805–807. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2004.11.002

HUGHES, R. A. (2022a), ‘Venice Postpones Visitor Entry Fee Again – Here’s When You’ll Have To Pay’, Forbes, 15 November. https://www.forbes.com/sites/rebeccahughes/2022/11/15/venice-postpones-visitor-entry-fee-again--heres-when-youll-have-to-pay/ [accessed on: 10.01.2023].

HUGHES, R. A. (2022b), ‘Venice Will Charge Tourists A $10 Entry Fee Starting This Summer’, Forbes, 21 April. https://www.forbes.com/sites/rebeccahughes/2022/04/21/venice-will-charge-tourists-a-10-entry-fee-from-this-summer/ [accessed on: 15.05.2022].

IOVINO, S. and BEGGIORA, S. (2021), ‘Introducing Lagoonscapes. The Venice Journal of Environmental Humanities’, Lagoonscapes, 1 (1), pp. 7–15.

IRSEV, COSES and COMUNE DI VENEZIA, ASSESSORATO ALL’URBANISTICA (1990), Terziari e domanda non residenziale a Venezia, Venezia.

LANDO, F. and ZANINI, F. (2008), L’impatto del turismo sul commercio al dettaglio. Il caso di Venezia, Venezia: Dipartimento di Scienze Economiche Università Ca’ Foscari di Venezia (Le Note di Lavoro).

LIMONTA, G. and PARIS, M. (2019), ‘Addensamenti di attività economiche nei contesti urbani consolidati: metodi d’indagine, geografie e dinamiche evolutive nel caso del centro storico di Parma’, [in:] AA, V., Atti della XXII Conferenza Nazionale SIU, L’urbanistica italiana di fronte all’Agenda 2030. Portare territori e comunità sulla strada della sostenibilità e resilienza. Matera-Bari, 5-6-7 giugno 2019. Roma-Milano: Planum Publisher, pp. 394–404.

LÓPEZ-GAY, A., COCOLA-GANT, A. and RUSSO, A. P. (2021), ‘Urban tourism and population change: Gentrification in the age of mobilities’, Population, Space and Place, 27 (1), p. e2380. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2380

MILANO, C. (2017), Overtourism y Turismofobia: Tendencias Globales y Contextos Locales. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.30241.10087

MILANO, C., CHEER, J. and NOVELLI, M. (2019), Overtourism: Excesses, Discontents and Measures in Travel and Tourism, Wallingford, MA, USA,: CABI.

MORANDI, C. (2011), ‘Retail and public policies supporting the attractiveness of Italian town centres: The case of the Milan central districts’, URBAN DESIGN International, 16 (3), pp. 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1057/udi.2010.27

NOVY, J. and COLOMB, C. (2019), ‘Urban Tourism as a Source of Contention and Social Mobilisations: A Critical Review’, Tourism Planning & Development, 16 (4), pp. 358–375. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2019.1577293

OLM, A. et al. (2012), The Merchants of Venice, p. 105. https://digitalcommons.wpi.edu/iqp-all/3241

PEDENZINI, C. and SCARAMUZZI, I. (1997), ‘Foto di famiglia in un interno commerciale’, [in:] BELLONI, M. C. and BIMBI, F., Microfisica della cittadinanza: città, genere, politiche dei tempi. Milano: Franco Angeli (GRIFF). http://coses.comune.venezia.it/fondaci/f_commercio8.html [accessed on: 11.05.2021].

RUSSO, A. P. (2002), ‘The «vicious circle» of tourism development in heritage cities’, Annals of Tourism Research, 29 (1), pp. 165–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(01)00029-9

SALERNO, G.-M. (2018), ‘Estrattivismo contro il comune. Venezia e l’economia turistica’, ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies, 17 (2), pp. 480–505.

SALERNO, G.-M. (2020), Per una Critica Dell’economia Turistica. Venezia tra Museificazione e Mercificazione, Macerata: Quodlibet.

SALERNO, G.-M. (2022), ‘Touristification and displacement. The long-standing production of Venice as a tourist attraction’, City, 0 (0), pp. 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2022.2055359

SALERNO, G.-M. and RUSSO, A. P. (2022), ‘Venice as a short-term city. Between global trends and local lock-ins’, Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30 (5), pp. 1040–1059. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1860068

SÉRAPHIN, H., GLADKIKH, T. and THANH, T.V. (2020), Overtourism: Causes, Implications and Solutions, 1st ed. 2020 edizione. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

SETTIS, S. (2014), Se Venezia muore, Torino: Einaudi.

TAMINI, L. (2016), ‘Commercio e città: temi e scenari evolutivi’, Urban Design Magazine, 4, pp. 19–26.

UNWTO, World Tourism Organization (2018), ‘«Overtourism»? Understanding and Managing Urban Tourism Growth beyond Perceptions. Executive Summary’. https://doi.org/10.18111/9789284419999

VAN DER BORG, J. (2017), ‘Sustainable Tourism in Venice: What Lessons for other Fragile Cities’, [in:] CAROLI, R. and SORIANI, S., Fragile and Resilient Cities on Water: Perspectives from Venice and Tokyo, Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 15–32.

VAN DER BORG, J. (2022), ‘Introduction to A Research Agenda for Urban Tourism’, A Research Agenda for Urban Tourism, pp. 1–15. https://www.elgaronline.com/view/edcoll/9781789907391/9781789907391.00006.xml [accessed on: 19.07.2022].

ZANARDI, C. (2020), La bonifica umana. Venezia dall’esodo al turismo, Milano: Unicopli (Lo scudo di Achille).

ZANINI, F., LANDO, F. and BELLIO, M. (2008), ‘Effects of Tourism on Venice: Commercial Changes Over 30 Years’, University Ca’ Foscari of Venice, Dept. of Economics Research Paper Series, 33. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=1292198