Abstract. This paper focuses on the issues of governance and participation of World Heritage sites. It inquiries how decision-making structures to locally managed World Heritage sites may encompass public participation. Through an in-depth qualitative approach, the paper analyses the World Heritage Arab-Norman Palermo and the Cathedral Churches of Cefalù and Monreale serial site (Italy). By examining the participatory dynamics that occurred during the creation and development of the selected World Heritage serial site, this paper reveals three coexisting forms of participation in WH-site decisions: inter-institutional agreement, social aggregation, and multi-actor collaboration. The main findings suggest that although formal decision-making arenas may be participative weakly, the unpacking of participatory practices in urban spaces uncovers a vibrant scene, as it emerges from the Cassaro Alto and Danisinni districts in the city of Palermo.

Key words: World Heritage, participatory governance, decision-making, Palermo.

The alignment of the World Heritage (WH) program (Labadi, 2007; Meskell, 2013) with the sustainable development agenda (UNESCO, 2015) is conferring increasing relevance to the issue of participation in the governance of WH sites (Li et al., 2020; Rosetti et al., 2022). As the policy acknowledges, this novel orientation implies the involvement of several stakeholders (Millar, 2006), adding complexity to decision-making processes concerning the management of WH sites. This paper aims to reveal some of the forms that such complexity could take. More specifically, it focuses on participatory practices occurring during the creation and development of the WH Arab-Norman Palermo and the Cathedral Churches of Cefalù and Monreale serial site (Italy). It is structured as follows: the first part deals with the theoretical background; the second highlights the research gap; the third discusses the adopted methodology; the fourth illustrates the most relevant findings emerging from the fieldwork; and, lastly, the fifth part concerns general reflections for fostering further investigations on the topic.

The paper leverages two academic streams concerning both the global mechanism ruling the WH program and the topic of participatory governance in political, social science, and heritage studies debates.

Considering the definition of regimes as “social institutions that influence the behavior of states within an issue area” (Levy et al., 1995), the first section reviews the principles and mechanisms found at the base of the international WH program, including the more recent alignment with the UN 2030 Agenda and the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (UNESCO, 2015). Generally speaking, the notion of a regime as a precursor of global governance (Stokke, 1997) attempted to re-position the debate on international politics from idealism to realism, querying the effects and constraints produced on state behaviours. From this perspective, since its foundation in 1972 by the UNESCO General Conference, the WH regime can be interpreted as a formal global arena to guide state parties in creating and preserving cultural and natural WH sites of Outstanding Universal Value (OUV), under agreed standards (Ferrucci, 2012; Schmitt, 2015; Bogandy et al., 2010). The WH regime exerts its influence on state parties through tools of persuasive and soft powers, such as listing and delisting mechanisms, and confers to every state the autonomy for undertaking any decision depending on national socio-political contexts, the nature of the site, and administrative traditions. This flexibility is reinforced by the principle of state sovereignty within the convention concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage (UNESCO, 1972). The latter confers a certain degree of autonomy to state parties, allowing them to adapt international regulations established by the WH regime to national socio-political contexts, depending on a site’s nature and administrative traditions. Furthermore, state parties are crucial mediators between multi-scalar relations that distinguish the WH regime (Wang, 2019; Bogandy et al., 2010, p. 753). They select heritage sites from the national Tentative List to compete for the WH nomination and can decentralise responsibilities concerning the protection and enhancement of WH sites to other entities acting at the territorial level of the WH site (Coombe and Weiss, 2015, pp. 43–49).

In a nutshell, the principle of state sovereignty can determine a two-fold effect: the heterogeneity of local governance structures responsible for managing a WH site and the dependency on the WH regime’s success in achieving protection and sustainable development objectives for WH sites from local strategies.

The second part of the theoretical section deepens the concept of participatory governance. Despite the vastness of meticulous literature emerging, the establishing of an exact definition of participatory governance is still challenging both in theory and in practice (Bevir, 2007; Fischer, 2006, 2010, 2012; Fung and Wright, 2001; Gustafson and Hertting, 2017; Heinelt, 2010). As highlighted in Bevir’s definition, the expression itself hybridises the two terms governance and participation.

While the term governance, in its generic connotation, signals a shift from centralised steering of society by the state to decentralisation of power among a plurality of actors (Peters and Pierre, 1998), the adjective participatory emphasises the need to encourage citizen engagement within decisional processes. As stated by Fisher (2010, p. 2): “Participatory governance is a variant or subset of governance theory that puts emphasis on democratic engagement, in particular through deliberative practices […] governance, as such, tends to refer to a new space for decision – making, but does not, in and of itself, indicate the kinds of politics that take place within them […]” (see also Fischer, 2006, 2012). According to the definition, participatory governance represents a valid response to the democratic deficit of representative political systems. This system expands the range of actions of citizens who, apart from voting for political representatives, can be directly involved in solving social problems, in the delivery of public services, and in more equitable forms of economic and social development (Fisher, 2010, p. 3). The author has also stressed how participatory governance is grounded on specific principles and methods, such as “fairer distribution of political power and resources”, and methods, from the “establishment of new partnerships to greater accountability” (Fischer, 2012, p. 2). It can follow diverse patterns, from top-down actions by policymakers to bottom-up processes implemented by civil society (Gustafson and Hertting, 2017).

In the field of heritage studies, participation is considered a crucial condition to ensure good and fair forms of governance both for tangible and intangible cultural heritage (Li et al., 2020). The Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society (CoE, 2005) in the European context has already affirmed the importance of interpreting cultural heritage as a common good, socially constructed, and considering the active participation of civil society decision-making levels a pillar for the process of heritage democratisation. Concerning the WH program, participatory governance deals with balanced participation of a wide variety of stakeholders and rights holders (UNESCO, 2019) and is indicated as a precondition for inclusive and sustainable management of a WH site in the long term. However, policy documents tend to idealise its effects, overlooking the issue of divergent interests among multiple actors and the risk of obtaining reverse outcomes such as the de-responsibiliation of the political class instead of a shared responsibilisation of civil society or new impetus for exclusion rather than inclusion (Fischer, 2012). In order to overcome this weakness, recent studies have suggested looking in greater detail at the local “pragmatics” of participatory practices (Beeksma and De Cesari, 2019), understanding how the who, why, and how take part in the process. Applying a similar approach to the study of a WH site could unveil how the participation of wider public evolves and interfaces with technical experts and political forces required by the WH Convention at several institutional levels: international, national, regional, and local.

When referring to the issue of governance within the framework of the WH Convention, attention is often turned towards the mechanism that regulates the WH regime at the global level. This interest has mostly led to research on power relations between the General Assembly of State Parties, the WH Committee, and Advisory bodies (Schmitt, 2015), and on the risk of political manipulation of the WH List (Meskell, 2013). Instead, few investigations focus on the governance structures created at the local level to manage a WH site and on how they can encompass forms of public participation (Ercole, 2017), often coming from the bottom and closely intertwined with strategies of territorial development (Pettenati, 2019). This paper aims to contribute to filling this gap, understanding how activities directly and indirectly tied to WH sites may reshape interactions among local institutions, civil society, and further players, generating mutable spaces for collaborations or further grounds of contestation within local socio-economic and political systems. For this purpose, the research refers to the conceptualisation of participatory governance as a “performative” process (Turnhout et al., 2010), which refers to the knowledge, interests, and needs of the involved actor, which emerge and evolve during the participation process itself.

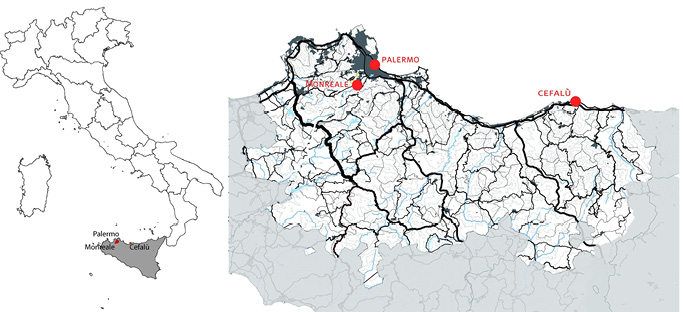

The paper discusses some findings related to the WH Arab-Norman Palermo and the Cathedral Churches of Cefalù and Monreale serial site located in the south of Italy (Sicily). A serial site entails two or more unconnected areas that might extend across regional, trans-regional, and transnational boundaries (Haspel, 2013).

A

B

Fig. 1. National and regional maps (A) indicating both location and extension of WH Arab-Norman Palermo and the Cathedral Churches of Cefalù and Monreale serial site; provincial map of Palermo (B) showing the distribution of the seven WH properties in the city

Source: https://arabonormannaunesco.it/la-nomina/protezione-e-gestione-del-sito-unesco.html, modified [accessed on: 20.07.2022]

Fig. 2. Overview of the monuments included in the serial World Heritage Arab-Norman Palermo, the Cathedral Churches of Cefalù, and Monreale serial site

Source: own work.

Normally, governance structures for WH serial sites present a higher level of organisationaling and operational complexity (Wang, 2019), which, by reflection, influences participatory processes. This mainly occurs due to a wider geographical extension, the encompassing of diverse legal frameworks, and the incorporation of heterogeneous ownerships and management systems related to multiple heritage properties. Out of a total of 55 WH sites in Italy, about 13 are serial sites of various extent and nature. The selected serial site gathers nine buildings, six of which are monumental catholic churches and cathedrals, considered sophisticated expressions of multicultural Western-Islamic-Byzantine syncretism (Andaloro et al., 2018). It extends between three different municipalities (Palermo, Cefalù, and Monreale) with a prevalent concentration of buildings in the city of Palermo (seven out of nine) (Fig. 1 and 2).

The investigation is grounded on a qualitative and constructivist approach (Creswell, 2009; Yin, 2003). It interprets reality as a changing social construction and has enabled the researchers to tackle participant perspectives through a wide repertoire of methods (such as interviews and field observations). Furthermore, it embraces a spatial conceptualisation of participatory processes (Cornwall, 2002, 2008; Lefebvre, 1991), by recognising the relevance of grasping interactions of individuals in the physical sites where they unfold and uncovering participation’s social space, intended as “the outcome of a sequence and set of operations” (Lefebvre, 1991, p. 73). The findings presented in this paper are part of a broader doctoral program, the research design of which has been articulated into three main steps from 2019 to 2021. The collected qualitative material has been extrapolated from multiple sources. Parts of this material already existed (such as official documents, minutes of meetings, etc.) while an additional part is being constructed through the interactions between the researcher and the investigated reality (Yin, 2003), by including a total of 34 semi-structured interviews, 6 informal meetings with both officials and local actors, and non-participant observations.

The empirical investigation concerning the in-depth analysis of a single case study (Yin, 2003) highlights three interesting perspectives to tackle the topic of participatory governance for WH sites:

The first perspective emerges from the analysis of the governance structure established for managing the WH Arab-Norman serial site. The structure appears articulated due to the fragmented ownership and scattered managerial responsibilities among a plethora of authorities and organisations. It mainly consists of a permanent Steering Committee (SC) that collects representatives from over ten different authorities (public administrations, regional boards, national government, etc.); an Operational Structure (OS) in charge of guaranteeing the implementation of the WH management plan activities; and the religious authorities who participate on the SC to supervise the religious functions. Such an arrangement is requested by WH Advisory bodies (ICOMOS) and follows the national guidelines provided by the Italian Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Other than formally responding to an international requirement, this structure comprises collaborative relations between national, regional, and local authorities who actively participated in preparing the WH nomination. In terms of participation, such relations were significantly extended from 2011 to 2013 during the development of the management plan of the WH serial site. At that time, some decision stages were opened to further local actors belonging to the third sector and civil society, spreading awareness regarding the significance of the WH status.

Namely, the Sicily World Heritage Foundation and the Regional Council of Cultural Heritage and Sicilian Identity, working as promoting entities of the candidacy, arranged 4 decisional arenas differentiated by subject (Andaloro et al., 2018, pp. 14–26). The first arena dealt with technical decisions such as the definition of the Buffer Zones system (Andaloro et al., 2018, pp. 56–80); the state of conservation and risk factors of the heritage properties; and the requalification and protection measures to be conducted. Advisors of the scientific-technical committee were the main participants.

The second arena aimed to define the objectives and activities of the 4 action strategies included in the WH management plan, i.e., knowledge, protection and conservation, social and cultural enhancement, and communication and promotion (Ernst and Young, 2006). Participants included institutional players, experts from the scientific-technical committee and several representatives of cultural and economic associations operating in the three municipalities.

The third and fourth arenas covered the WH site governance topic, gathering representatives of regional officials, local authorities (mainly the city councils of Palermo, Cefalú, and Monreale), religious bodies, and managers directly responsible for the protection and use of the WH serial site.

The second perspective was conceived prior to the acquisition of the WH status. It has arisen from a contrast between the Municipality of Palermo, part of the SC, and some residents and traders operating in the Cassaro Alto area. Cassaro Alto is one of the main urban axes that cross the city centre of Palermo and connect several monuments included in the World Heritage serial site. Here, the municipality intended to gain consensus from the local community to create a new pedestrian area that could improve the monument’s preservation from vehicular pollution, before the WH Committee ruled on the nomination outcome (Andaloro et al., 2018). However, some business people and residents objected to the decision. Although being generally in favour of the WH candidacy, they contested the permanent closure of the axis, being concerned with the negative impacts on their commercial activities and lifestyles. In this case, participatory mechanisms significantly evolved during the process: from conflict-ridden town meetings between public administrators and citizens to discussing alternative pedestrianisation solutions, to the spontaneous creation of a cultural association (called Cassaro Alto) that still collects almost all the business people of the areas today (historical bookstores, tobacco shops, bars, etc.) Initially, they considered the association a formal vehicle to gain greater credibility in front of the municipality in claiming their interests. More recently, the association has turned into a tool of cooperation between the business people themselves and a collaboration with local authorities to revitalise the cultural interest of the historical road, especially in light of the acquired WH status. The La Via Dei Librai cultural initiative arranged by the association along the pedestrian axis on the occasion of the UNESCO’s World book day reaches today its fifth edition, proving a stable alliance between the Cassaro Alto association, non-profit entities, and the municipality. The event is a form of active citizen participation that has grown over the years in terms of public attendance, organisational structure, and networks of public and private partners.

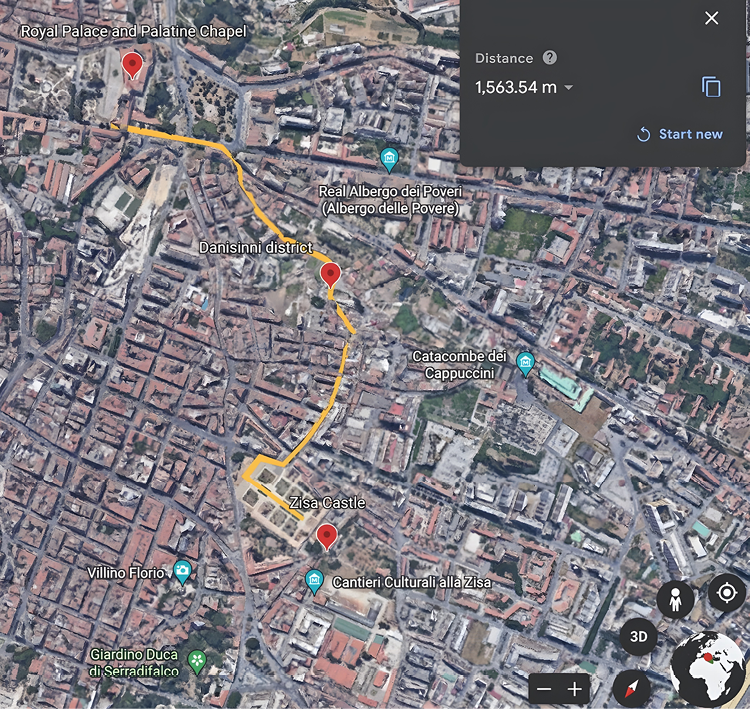

The third perspective follows the acquisition of the WH nomination. It is related to the sustainable tourism development that the SC aspires to achieve (Andaloro et al., 2018) by creating complementary routes to the WH itinerary. This is the case of the Danisinni historical neighbourhood, which connects two iconic monuments included within the WH serial site: the Royal Palace and the Zisa Castle (Fig. 3).

Despite its historical relevance since the Arab domination, the district still suffers from socio-economic marginalisation due to a long-lasting institutional void that has led to the dismantling of essential services, and to increasing isolation from its surroundings (Giubilaro and Lotta, 2018). The same void has triggered a significant form of grassroots activism nestled in the Danisinni community that groups third sector actors, a religious garrison, and some residents. Danisinni’s community had already committed to participatory projects in order to collect resources needed for the district regeneration. Being part of an international WH site, the community has increased its self-esteem, strengthening its position within forthcoming projects. Indeed, the interest of the municipality to boost tourism circulation within the district creates a fertile ground for the start of new collaborative initiatives, including the participation of further local (Academy of Fine Arts; Biondo Theater, etc.) and non-local players (Airbnb, Wonderful Italy, etc.) The two projects for tourist development (Rambla Papireto and Intransito) led to different results than expected, due to partial shifts of interest and the affirming of the Danisinni community’s willingness and needs. Indeed, the accomplishment of the WH route as the Municipality of Palermo expected following the two projects, was temporary shelved. The Danisinni community is attempting to affirm its development vision for the neighbourhood. Such conception of development is always based on slow tourism and leverages on the historical connection with the Arab-Norman WH serial site. However, it prioritises the creation of new job opportunities for residents. For this purpose, the Danisinni community focuses on the realisation of a mobile kitchen – labelled I Sapori di Danisinni – rather than on the materialisation of the WH route, in order to bring a new entrepreneurial mindset to the neighbourhood. Residents, especially women, may get involved in cooking traditional dishes for visitors, becoming key players of a social transformation in the district.

Fig. 3. Overview of the Danisinni district and its position between three WH properties: the Royal Palace, the Palatine Chapel, and the Zisa Castle

Source: own work and based on Google Earth images.

The presented investigation put forward some worthy reflections for the advancement of the debate on WH sites and participatory governance. The results stress how participation in WH site decisions may adopt heterogeneous forms, even within the same site, consequently resulting in the need to advance knowledge on this poorly explored issue. To further clarify, it suggests two main perspectives in the advancement of both debating and empirical studies.

The first consideration refers to the issue of participatory governance and practices (Beeksma and De Cesari, 2019). The maximum expression of participatory governance should imply a systematic opening of decision-making areas to influence a broader public. However, it is likewise reasonable to consider that participation may be performed at different levels and in different forms (Arnstein, 1969) through various and parallel stages of contestation, negotiation, and coordination among popular actors. The selected case study shows how decisions can be negotiated both in formal and institutionalised areas, and in informal arenas. Despite formal consultations of civil society for drafting the WH management plan, the unpacking of participatory practices uncover a vibrant scene where new civic associations could emerge directly from a contested process of the WH site creation. Specifically, the analysed WH Arab-Norman Palermo and the Cathedral Churches of Cefalù and Monreale serial site has highlighted three different forms of participation: a ruled inter-institutional collaboration concerning the SC and the OS, a spontaneous social aggregation that emerged for the Cassaro Alto association, and a network of multi-actor initiatives as seen for the tourist development of the Danisinni district. The three detected forms are not necessarily exhaustive. Nevertheless, they stress the importance in the field of heritage studies, and more specifically for WH sites, to grasp participatory dynamics starting from local practices, unveiling social actors, and correlated strategies that affect and reinforce WH sites’ significance in contemporary society (Dormaels, 2016).

Secondly, there is a need to deepen knowledge of the organisational and operating mechanisms of local governance structures in charge of managing WH sites (Ercole, 2017). In fact, the mere consideration of them as formal arrangements may result an anachronistic approach to contemporary scenarios. Indeed, the increasing recognition of WH sites as key assets for sustainable development makes the understanding of the relationships and interests of the ever-growing numbers of involved local authorities a key element in decoding territorial transformations directly or indirectly influenced by the creation of a WH site.

Acknowledgements. The authors would like to acknowledge the valuable support of the Interuniversity Department of Regional and Urban Studies and Planning of the University and Polytechnic school of Turin for the opportunity to develop this research as part of a PhD programme. A special thanks goes to the SPOT project coordinators, who engaged us in the research project.

ANDALORO, M., ANGELINI, A., CARTA, M., LINO, B., LONGO, R., RICCIO, F. and SCIMEMI, L. (2018), Palermo Arabo-Normanna e le Cattedrali di Cefalù e Monreale. Piano di Gestione per l’iscrizione nella World Heritage List del sito seriale, Palermo: Officine Grafiche.

ARNSTEIN, S. R. (1969), ‘A Ladder of Citizen Participation’, Journal of The American Institute of Planners, 35, pp. 37–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225

BEEKSMA, A. and DE CESARI, C. (2019), ‘Participatory heritage in a gentrifying neighbourhood: Amsterdam’s Van Eesteren Museum as affective space of negotiations’, International Journal of Heritage Studies, 25 (9), pp. 974–991. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2018.1509230

BEVIR, M. (2007), Encyclopedia of Governance, Vol. 1, SAGE Publications, Inc.

BOGDANDY, A., WOLFRUM, R., BERNSTORFF, J., DANN, P. and GOLDMANN, M. (eds.). (2010), The exercise of public authority by international institutions: advancing international institutional law, 210, Springer Science and Business Media.

CoE (2005), Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society.

COOMBE, R. J. and WEISS, L. M. (2015), ‘Neoliberalism, Heritage Regimes, and Cultural Rights’, SSRN Electronic Journal, pp. 43–69. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2644495

CORNWALL, A. (2002), ‘Making spaces, changing places: situating participation in development’, Institute of development studies. Working papers, 170.

CORNWALL, A. (2008), ‘Unpacking “Participation”: models, meanings and practices’, Community Development Journal, 43 (3), pp. 269–283. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsn010

CRESWELL, J. W. (2009), Research Design Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, Los Angeles: SAGE.

DORMAELS, M. (2016), ‘Participatory management of an urban world heritage site’, Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development, 6 (1), pp. 14–33. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCHMSD-11-2014-0038

ERCOLE, E. (2017), ‘Governance, Partecipazione e Inclusione nei piani di gestione dei siti della World Heritage List dell’UNESCO’, Annali del Turismo, VI, pp. 177–194.

ERNST and YOUNG (2006), Progetto di definizione di un modello per la realizzazione dei Piani di Gestione dei siti UNESCO. https://www.yumpu.com/it/document/read/15103945/modello-per-la-realizzazione-dei-piani-di-gestione-ufficio [accessed on: 07.05.2022].

FERRUCCI, S. (2012), UNESCO’s World Heritage regime and its international influence, Hamburg: Tredition.

FISCHER, F. (2006), ‘Participatory Governance as Deliberative Empowerment’, The American Review of Public Administration, 36 (1), pp. 19–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074005282582

FISHER, F. (2010), ‘Participatory Governance’, Jerusalem Papers in Regulation & Governance, 24, pp. 1–19.

FISCHER, F. (2012), ‘Participatory Governance: From Theory To Practice’, [in:] LEVI-FAUR, D. (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Governance, pp. 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199560530.001.0001

FUNG, A. (2006), ‘Varieties of Participation in Complex Governance’, Public Administration Review, 66 (s1), pp. 66–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2006.00667.x

FUNG, A. and WRIGHT, E. O. (2001), ‘Deepening Democracy: Innovations in Empowered Participatory Governance’, Politics & Society, 29 (1), pp. 5–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032329201029001002

GIUBILARO, C. and LOTTA, F. (2018), ‘Quartiere in transizione. Il caso di Danisinni (Palermo) tra marginalità socio-spaziale e rigenerazione di comunità’, Atti della XXI Conferenza Nazionale SIU, pp. 481–487, Florence, 6–8 June 2018.

GUSTAFSON, P. and HERTTING, N. (2017), ‘Understanding Participatory Governance: An Analysis of Participants’ Motives for Participation’, American Review of Public Administration, 47 (5), pp. 538–549. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074015626298

HASPEL, J. (2013), ‘Transnational Serial Nominations for the UNESCO World Heritage List’, ICOMOS–Hefte des Deutschen Nationalkomitees, 58, pp. 21–23.

HEINELT, H. (2010), Governing Modern Societies. Governing Modern Societies: Towards Participatory Governance, London: Routledge.

LABADI, S. (2007), ‘Representations of the nation and cultural diversity in discourses on World Heritage’, Journal of Social Archaeology, 7 (2), pp. 147–170. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469605307077466

LEFEBVRE, H. (1991), The production of space, Oxford: Blackwell.

LEVY, M. A., YOUNG, O. R. and ZÜRN, M. (1995), ‘The Study of International Regimes’, European Journal of International Relations, 1 (3), pp. 267–330. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354066195001003001

LI, J., KRISHNAMURTHY, S., PEREIRA RODERS, A. and van WESEMAL, P. (2020), ‘State-of-the-practice: Assessing community participation within Chinese cultural World Heritage properties’, Habitat International, 96, 102107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2019.102107

MESKELL, L. (2013), ‘UNESCO’s World Heritage Convention at 40’, Current Anthropology, 54 (4), pp. 483–494. https://doi.org/10.1086/671136

MILLAR, S. (2006), ‘Stakeholders and community participation’. [in:] LEASK, A. and FYALL, A., Managing World Heritage Sites (1st ed.), pp. 63–80, London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780080461755

PETERS, B. G. and PIERRE, J. (1998), ‘Governance Without Government? Rethinking Public Administration’, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 8 (2), pp. 223–243. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.jpart.a024379

PETTENATI, G. (2019), I paesaggi culturali Unesco in Italia, Milano: Franco Angeli.

ROSETTI, I., CABRAL, C. B., RODERS, A. P., JACOBS, M. and ALBUQUERQUE, R. (2022), ‘Heritage and Sustainability: Regulating Participation’, Sustainability, 14 (3), p. 1674. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14031674.

SCHMITT, T. (2015), ‘UNESCO as a Red Cross or as a notary of World Heritage? Structures, scale-related interactions and efficacy of UNESCO’s World Heritage regime’, MMG Working Papers Series, Max Planck Institute for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity, 40, pp. 1–43. ISBN: ISSN 2192-2357

STOKKE, O. S. (1997), ‘Regimes as Governance Systems’, [in:] YOUNG, O. R. (ed.), Global Governance Drawing Insights from Environmental Experience, pp. 27–65, Cambridge: The Mitt Press.

TURNHOUT, E., Van BOMMEL, S. and AARTS, N. (2010), ‘How Participation Creates Citizens: Participatory Governance as Performative Practice’, Ecology and Society, 15 (4), p. 26.

UNSECO (1972), Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. https://whc.unesco.org/en/conventiontext/ [accessed on: 08.07.2022].

UNESCO (2015), Policy for the integration of a sustainable development perspective into the processes of the World Heritage Convention. https://whc.unesco.org/document/187765 [accessed on: 08.05.2022].

UNESCO (2019), Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention. https://whc.unesco.org/en/guidelines/ [accessed on: 08.05.2022].

WANG, J. (2019), ‘Relational heritage sovereignty: authorization, territorialization and the making of the Silk Roads’, Territory, Politics, Governance, 7 (2), pp. 200–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2017.1323004

YIN, R. K. (2003), Case study research: Design and methods, Thousand Oaks: Sage Publication.